| Abu'l-Fath Khan Javanshir | |

|---|---|

| Died | c. 1839 |

| Allegiance | Qajar Iran |

| Battles / wars | Russo-Iranian War of 1804–1813 |

| Children | Abbasqoli Khan Mo'tamed od-Dowleh Javanshir Mohammad Ali Khan Mohammad Qoli Khan Mohammad Taqi Khan |

| Relations | Ibrahim Khalil Khan (father) Mehdi Qoli Khan Javanshir (brother) Agha Baji Javanshir (sister) |

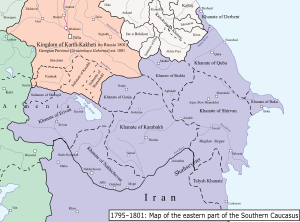

Abu'l-Fath Khan Javanshir (also spelled Abo'l-Fath; Persian: ابوالفتح بیگ جوانشیر; died c. 1839) was an Iranian commander who participated in the Russo-Iranian War of 1804–1813. He was the son of Ibrahim Khalil Khan, a member of the Javanshir tribe and governor of the Karabakh Khanate in the South Caucasus.

Being a concubine's son, he had little chance of being his father's legitimate heir. He consistently supported Iran, unlike his family, who shifted allegiances between Qajar Iran and the Russian Empire. He became a commander and advisor of the Iranian crown prince Abbas Mirza when the war erupted. Soon afterwards, he also received control over Kapan and Meghri. In 1810, Abbas Mirza appointed Abu'l-Fath Khan as the governor of the fortress of Dezmar, located on the southern bank of the Aras river. Iran and Russia made peace in 1813, signing the Treaty of Gulistan, which amongst other things, led to the Iranian surrender of Karabakh. Abu'l-Fath Khan seemingly continued to control Dezmar after the war had ended. In 1818, he was given the governorship over some de facto Russian land that Abbas Mirza had just seized. His life and activities are unknown from this point until his death, and it is unknown if he participated in the following Russo-Iranian War of 1826–1828. He had four sons, including Abbasqoli Khan Mo'tamed od-Dowleh Javanshir, who became the Minister of Justice of Iran in 1859.

Abu'l-Fath Khan also distinguished himself for his interest in, and talent for, poetry and literature, writing under the pen name Tuti ("parrot"). His poetry was appreciated by prominent figures of his time, including his close friend Abd al-Razzaq Beg Donboli, who made reference to his kindness and generosity.

Biography

Abu'l-Fath Khan was a member of the Javanshir tribe, a Turkic tribe which lived in the Karabakh region of the South Caucasus. He was one of the youngest sons of Ibrahim Khalil Khan, the khan (governor) of the Karabakh Khanate under Iranian suzerainty. Abu'l-Fath Khan's mother was an Armenian concubine, which lowered his chance of becoming the legitimate successor of his father. He might have attempted to use his Armenian heritage as an opportunity to solicit assistance from Karabakh's substantial Armenian community.

Abu'l-Fath Khan's family, especially Ibrahim Khalil Khan, would occasionally shift their allegiance between Qajar Iran and the Russian Empire. In contrast to his father and other family members, Abu'l-Fath Khan always supported Iran and is reported to have fought bravely in the army of Abbas Mirza, the crown prince of Iran during the reign of Fath-Ali Shah Qajar (r. 1797–1834). Abu'l-Fath Khan's first political experience likely occurred when, at his father's request, he accompanied the funeral procession of Agha Mohammad Khan—who had been killed outside the Shusha fortress—to Nakhchivan. There he gave Agha Mohammad Khan's body to the latter's nephew and successor, Fath-Ali Shah. Following this, Fath-Ali Shah gave Abu'l-Fath Khan an official reception in his residence in Mianeh. Ibrahim Khalil Khan quickly established friendly relations with Fath-Ali Shah Qajar, who married his daughter Agha Baji Javanshir and confirmed him as the khan of Karabakh. Abu'l-Fath Khan, who was around the same time sent as a hostage the shah, accompanied Agha Baji to the Iranian court. When the Russo-Iranian War of 1804–1813 erupted, Abu'l-Fath Khan was made a commander and advisor of Abbas Mirza.

Fath-Ali Shah lost trust in Ibrahim Khalil Khan because he declined to help Javad Khan against the Russian siege of Ganja in 1804. He therefore appointed Abu'l-Fath Khan as the new khan. Despite this, Ibrahim Khalil Khan continued to rule Karabakh. Abu'l-Fath Khan was also appointed the ruler of lands outside Karabakh, Kapan and Meghri, where he successfully established control.

In May 1805, Ibrahim Khalil Khan submitted to the Russians, signing the Treaty of Kurekchay, which granted them full authority over Karabakh's external affairs in exchange for a yearly payment. Soon finding himself in a difficult position, Ibrahim Khalil Khan rejoined the Iranians. Abu'l-Fath Khan and Farajollah Khan Shahsevan were subsequently dispatched to repel the Russians from Karabakh, but Ibrahim Khalil Khan was killed by a group Russian soldiers shortly afterwards. This was done under the instigation of his grandson Ja'far Qoli Agha and the commander of the Russian garrison.

Afterwards, Abu'l-Fath Khan and Ata Allah Khan Shahsevan helped in relocating some Karabakh tribes such as the Jabraillu to the periphery of Kapan. Abu'l-Fath Khan fought the Russian troops in multiple encounters throughout this operation, even losing to Ja'far Qoli Agha in one of them. Although Ja'far Qoli Agha had hoped to become the new khan for helping the Russians against his grandfather, they ultimately appointed Ibrahim Khalil Khan's 30-year-old son Mehdi Qoli Khan Javanshir, due to the support he enjoyed amongst the distinguished figures of Karabakh. Although Mehdi Qoli Khan held the title of khan of Karabakh, he was in reality a figurehead, the real authority being held by the Russians. In April/May 1810, the Russians conquered Meghri. Abu'l-Fath Khan subsequently relocated some of the nomads near Meghri to Iran, for which he was rewarded with rule over the fortress of Dezmar, located on the southern bank of the Aras river. Iran and Russia made peace in 1813, signing the Treaty of Gulistan, which among other things, led to the Iranian surrender of Karabakh.

Abu'l-Fath Khan seemingly continued to control Dezmar after the war had ended. In 1818, he was given the governorship over some de facto Russian land that Abbas Mirza had just seized. His life and activities are unknown from this point until his death, and it is unknown if he participated in the following Russo-Iranian War of 1826–1828. The precise date of Abu'l-Fath Khan's death is not mentioned in any of the contemporary or nearly contemporaneous sources. The Iranian historian Seyyed Ahmad Divan Beygi Shirazi is the only one who somewhat brings up this subject, mentioning that it happened soon after 1834. The Iranian intellectual Mohammad Ali Tarbiat, whose research was based on numerous unidentified sources, estimated that Abu'l-Fath Khan died in 1839, which the Iranian historian Seyyed Ali Al-i Davud considers to be with consistent with Divan Beygi Shirazi's assertion.

Cultural patronage

Apart from his military achievements, Abu'l-Fath Khan was renowned for his interest and talent for poetry and literature, which got him included in Abbas Mirza's small circle. He wrote poetry under the pen name Tuti ("parrot"), his verses being quoted by figures such as Abd al-Razzaq Beg Donboli, Mahmud Mirza Qajar and Reza-Qoli Khan Hedayat. Abd al-Razzaq Beg Donboli was a close friend of Abu'l-Fath Khan, and made reference to his kindness and generosity, which Davud states he was well known for.

Offspring

Abu'l-Fath Khan had four sons;

- Mohammad Taqi Khan, who died in 1851.

- Mohammad Ali Khan, a sarhang (colonel) in the army of Abbas Mirza's son Qahraman Mirza.

- Mohammad Qoli Khan, a major in the army of Qahraman Mirza.

- Abbasqoli Khan Mo'tamed od-Dowleh Javanshir, a statesman under Naser al-Din Shah Qajar, who was appointed the Minister of Justice in 1859.

Notes

- Keeping hostages was a strategy used by Iranian rulers. Its purpose was to guarantee the khans of the several provinces would follow orders.

References

- Bournoutian 2021, pp. 261–262.

- Bournoutian 1994, p. 95 (see note 274).

- ^ Davud 2021.

- Bournoutian 2016, p. xvii.

- Bournoutian 2021, p. 103 (see note 11).

- ^ Bournoutian 2021, p. 107 (see note 27).

- ^ Davud 2015.

- Bournoutian 2021, p. 263.

- Bournoutian 1994, p. 107 (see note 332).

- Tapper 1997, p. 123.

- Bournoutian 2021, p. 83 (see also note 116).

- Bournoutian 2021, pp. 135–136.

- Bournoutian 1994, pp. 4, 29, 104 (see note 15, 4, and 318).

- Bournoutian 2021, p. 184 (see also note 71).

- ^ Busse 1983, pp. 285–286.

- Daniel 2001, pp. 86–90.

Sources

- Bournoutian, George (1994). A History of Qarabagh: An Annotated Translation of Mirza Jamal Javanshir Qarabaghi's Tarikh-e Qarabagh. Mazda Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56859-011-0.

- Bournoutian, George (2016). The 1820 Russian Survey of the Khanate of Shirvan: A Primary Source on the Demography and Economy of an Iranian Province prior to its Annexation by Russia. Gibb Memorial Trust. ISBN 978-1-909724-80-8.

- Bournoutian, George (2021). From the Kur to the Aras: A Military History of Russia's Move into the South Caucasus and the First Russo-Iranian War, 1801–1813. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-44515-4.

- Busse, H. (1983). "Abu'l-Fatḥ Khan Javānšīr". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. I/3: Ablution, Islamic–Abū Manṣūr Heravı̄. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 285–286. ISBN 978-0-71009-092-8.

- Daniel, Elton L. (2001). "Golestān Treaty". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. XI/1: Giōni–Golšani. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 86–90. ISBN 978-0-933273-60-3.

- Davud, Seyyed Ali Al-i (2015). "Abū al-Fatḥ Khān Jawānshīr". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Davud, Seyyed Ali Al-i (2021). "Ibrāhīm Khalīl Khān Jawānshī". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_30552. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Tapper, Richard (1997). Frontier Nomads of Iran: A Political and Social History of the Shahsevan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58336-7.