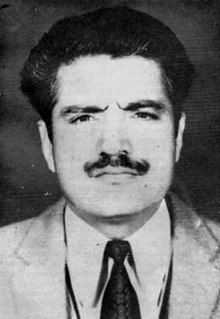

| Maqbool Bhat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Muhammad Maqbool Bhat (1938-02-18)18 February 1938 Trehgam Kupwara, Jammu and Kashmir, British India |

| Died | 11 February 1984(1984-02-11) (aged 45) Tihar Jail, Delhi, India |

| Cause of death | Hanging |

| Education | SJS Baramulla |

| Organization | NLF & JKLF |

| Known for | Kashmiri Separatism |

Maqbool Bhat (1938–1984), was a Kashmiri separatist leader, who went to Pakistan and founded the National Liberation Front (NLF), which was a precursor to the present day Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF). He is also termed as the "Father of the Nation of Kashmir" Baba-e-Qaum, by the locals. Bhat carried out multiple attacks in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir. He was arrested and sentenced to double death sentence. He was hanged on 11 February 1984 in Tihar Jail in Delhi.

Early life

Muhammad Maqbool Bhat was born on 18 February 1938 in the Trehgam village of the Kupwara district in the Kashmir Valley of the princely state of Kashmir and Jammu in British India (now Jammu and Kashmir, India) into a Kashmiri Muslim family. His father was called Ghulam Qadir Bhat. His mother died when Maqbool was 11 years old, and his father remarried.

After studying locally, Bhat went to study at the St. Joseph's School and College in Baramulla, where he graduated with Bachelor of Arts degree in History and Political Science around 1957.

Political career

The feudal system under the princely state and the politics of Sheikh Abdullah after independence shaped Bhat's political views. During the college days, he was involved with the student activities of the Plebiscite Front (founded by Mirza Afzal Beg when Sheikh Abdullah was in prison for canvassing for independence). In December 1957, Sheikh Abdullah was released, leading to agitations. He was rearrested in April 1958. The student activists of the Plebiscite Front were also targeted at this time, causing Maqbool Bhat to leave for Pakistan in August 1958.

Bhat joined the Peshawar University, studying for an MA Urdu Literature in Peshawar, Pakistan He worked for some time as a journalist for the local newspaper Anjaam. In 1961, Bhat contested in the 'Basic Democracy' elections introduced by President Ayub Khan's military regime, and won the Kashmiri diaspora seat from Peshawar. The elected government of K. H. Khurshid lasted till 1964, when Pakistan forced its resignation.

In April 1965, the Azad Kashmir Plebiscite Front was formed in Muzaffarabad at the initiative of Abdul Khaliq Ansari, its president, and Amanullah Khan, its general secretary. Maqbool Bhat was appointed as the publicity secretary, owing to his journalistic background. Journalist Arif Jamal states that, the participants drove to an unguarded location of the Kashmir Line of Control at Suchetgarh and, bringing back soil from the Indian-held Kashmir, took an oath that they would work exclusively for the liberation of Jammu and Kashmir.

Amanullah Khan and Maqbool Bhat also wanted to set up an armed wing for the Plebiscite Front, but the proposal did not get the majority support in the Plebiscite Front. Undeterred, they established an underground group called National Liberation Front (NLF), obtaining some support for it in August 1965. The group was fashioned after the Algerian Front de Libération Nationale. Major Amanullah, a former soldier in the Azad Kashmir forces, was in charge of the armed wing while Amanullah Khan and Mir Abdul Qayoom took charge of the political and financial wings. Maqbool Bhat was made responsible for the overall coordination. All the members swore in blood that they would be ready to sacrifice their lives for the objective of the NLF, viz., to create conditions in Jammu and Kashmir that enable its people to demand self-determination. The organisation was successful in recruiting members from Azad Kashmir, and obtained backing from the bureaucracy of the state.

Militancy

First reentry

For ten months, The NLF recruited and trained a cadre of militants in the use of explosives and small arms. On 10 June 1966, two groups of NLF crossed into Jammu and Kashmir. The first group consisting of Maqbool Bhat, a student from Gilgit called Tahir Aurangzeb, an immigrant from Jammu called Mir Ahmad, and a retired subedar called Kala Khan, went around the cities to find recruit and set up secret cells. The second group, under Major Amanullah, trained the recruit in sabotage activities in the forests of Kupwara. However, in September 1966, Bhat's group was compromised near Srinagar. The group kidnapped a CID police inspector called Amar Chand as a hostage and, when he tried to escape, shot and killed him. The police mounted a search and zeroed in on them, leading to an exchange of fire in the Kunial village near Handwara. A member of Bhat's group, Kala Khan, was killed. Bhat and Mir Ahmad were captured and tried for sabotage and murder, receiving death sentences from a Srinagar court in September 1968. Major Amanullah's wing waiting to receive the volunteers at the Line of Control retreated, but it was arrested by the Pakistan Army.

Maqbool Bhat's arrest brought the group's activities into the open, and sharply divided the Plebiscite Front. Nevertheless, they declared it an unconstitutional body and "banned" it. Meanwhile, Maqbool Bhat and Mir Ahmad escaped from the Indian prison in December 1968, along with another inmate Ghulam Yasin, tunneling their way out of the prison complex. They returned to Azad Kashmir in January 1969, creating a sensation in the militant circles. Their standing increased within the community, forcing the Plebiscite Front to abandon its opposition. However, the NLF's failed operations in Jammu and Kashmir put at risk all its sympathisers in the state, many of whom were arrested.

Their escape from an Indian prison was viewed with suspicion by Pakistan. Bhat and his colleagues were detained and brutally interrogated for several months. Long after their release, Bhat was still suspected of being a double agent. Pakistan extended little support to the other Indian youth that crossed over into Azad Kashmir for arms and training. Praveen Swami suggests that, as Pakistan was waging a covert war through its own network in Jammu and Kashmir, it did not want those official operations jeopardised by the amateur operators of the NLF.

Ganga hijacking

Hashim Qureshi, a Srinagar resident who went to Peshawar on family business in 1969, met Maqbool Bhat and got inducted into the NLF. He was given an ideological education and lessons in guerrilla tactics in Rawalpindi. In order to draw the world's attention to the Kashmiri independence movement, the group planned an airline hijacking fashioned after the Dawson's Field hijackings by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. Hashim Qureshi, along with his cousin Ashraf Qureshi, was ordered to execute one. A former Pakistani air force pilot Jamshed Manto trained him for the task. However, Qureshi was arrested by the Indian Border Security Force when he tried to reenter into Jammu & Kashmir, India via LoC with arms and equipment. He negotiated his way out by claiming to help find other conspirators that were allegedly in the Indian territory, sought an appointment in the Border Security Force to provide such help. Maqbool Bhat sent Qureshi replacement equipment for the hijacking, but it fell into the hands of a double agent, who then turned it over to the Indian authorities. Undeterred, the Qureshis made look-alike explosives out of wood and hijacked an Indian Airlines plane called Ganga on 30 January 1971.

The hijackers landed the plane at Lahore and demanded the release of 36 NLF prisoners lodged in Indian jails. However, they succumbed to pressure from the airport authorities and ended up releasing all the passengers and the crew. Years later, Ashraf Qureshi admitted that they were naive and didn't realise that "the passengers were more important than the actual plane." Pakistan's Prime Minister Zulfikar Bhutto showed up at the airport and paid a handsome tribute to the hijackers. Indian Government then refused to carry out the demands. The plane lay on the tarmac for eighty hours, during which the Pakistani security personnel thoroughly searched the air plane and removed papers and postal bags they found in it. Eventually, upon the advice of the authorities, Hashim Qureshi burnt the plane down.

For some time, the Qureshis were lauded as heroes. After India reacted by banning overflight of Pakistani planes over India, the Pakistani authorities claimed that the hijack was staged by India, and arrested the hijackers and all their collaborators. A one-man investigation committee headed by Justice Noorul Arifeen declared the hijacking to be an Indian conspiracy, citing Qureshi's appointment in the Border Security Force. In addition to the hijackers, Maqbool Bhat and 150 other NLF fighters were arrested. Seven people were eventually brought to trial (the rest being held without charges). The High Court acquitted them of treason charges. Hashim Qureshi alone was sentenced to seven years in prison. Ironically, Ashraf Qureshi was released even though he was an equal participant in the hijacking. This is said to have been a deal made by Zulikar Bhutto, by now the President of Pakistan, who declared that he would convict one hijacker but release the other.

Amanullah Khan was also imprisoned for 15 months in a Gilgit prison during 1970-72, accused of being an Indian agent. He was released after protests broke out in Gilgit. Thirteen of his colleagues were sentenced to 14 years in prison, but released after a year. According to Hashim Qureshi, 400 activists of the Plebiscite Front and NLF were arrested in Pakistan after the Ganga hijacking. Abdul Khaliq Ansari, who was arrested and tortured, testified in the High Court that the Ganga hijacking had emboldened the people to question the corrupt practices of the Azad Kashmir leaders and, in reaction, the government arrested them and forced them to confess to being Indian agents.

Second reentry

Further attempts by the NLF to infiltrate into Jammu & Kashmir, India also met with failure. The organisation did not have enough funds and infrastructure, or support from other sources, to make an impact inside India.

In May 1976, Maqbool Bhat reentered Jammu & Kashmir again. He was encouraged by the student protests against the 1974 Indira-Sheikh accord, by which Sheikh Abdullah surrendered his demand and joined Indian system. Bhat attempted to rob a bank in Kupwara. A bank employee was killed in the course of the robbery. Bhat was rearrested and received a second death sentence.

JKLF

Bhat's arrest effectively broke the back of the NLF in Azad Kashmir. Amanullah Khan moved to England, where he received the enthusiastic support of the British Mirpuri community. The UK chapter of the Plebiscite Front was converted into the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF) in May 1977 and formed an armed wing called the `National Liberation Army'. Amanullah Khan took charge as the General Secretary of JKLF the following February.

Several attempts were made by different Kashmiri groups for the release of Maqbool Bhat, including the hijacking of an Indian plane by Abdul Hameed Diwani in 1976 and an unsuccessful attempt to blow up the Delhi conference hall of Non Alignment Movement in 1981. In the first week of February 1984, the ‘National Liberation Army’ of JKLF kidnapped an Indian diplomat Ravindra Mhatre from the Indian consulate in Birmingham. They demanded the release of Maqbool Bhat and a sum of money from the Indian government but killed him just two days after abduction.

Death

Within a week of the diplomat's killing, Bhat's petition for clemency was rejected. He was executed in the Tihar Jail in New Delhi on 11 February 1984, amidst heavy security. Bhat was described as calm and composed, who did not "utter any word as he was being taken to the gallows". His body was buried within the Tihar Jail premises against his wishes. High-ranking officials in the government said that the hanging was meant to signal a harder line against political violence.

Sporadic incidents of protest against Bhat's execution were reported in the newspapers, which were described as "tremors of tension". In Trehgam, no shops opened for four consecutive days. In old Srinagar, streets were deserted even though there was no call for any bandh. The police had already arrested around 1,000 opposition members in the preceding days in order to preempt protests.

Abdul Ghani Lone, then a member of the legislative assembly, described the hanging as "judicial murder". Bhat's lawyers called it a "political and hasty decision". They believed it was a violation of Bhat's constitutional rights to hang him in haste.

Legacy

Five years after Bhat’s hanging, the Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF) launched a militant movement for the separation of the UT of Jammu & Kashmir from India. Since his death, the JKLF has been demanding that the mortal remains of the party's founder, which were buried inside the Tihar Jail, be handed over. Separatist leaders also call for shutdown each year, which is observed in the Valley to mark his anniversary of death. JKLF announced a ceasefire in 1994.

On 4 November 1989, JKLF militants allegedly shot dead judge Neelkanth Ganjoo, who had presided over the Amar Chand murder trial, and declared sentence of death on Maqbool Bhat.

See also

- Hurriyat and Problems before Plebiscite

- Syed Ali Shah Geelani

- Kashmir conflict

- 2014 Jammu and Kashmir Legislative Assembly election

Notes

- The Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front was founded in Birmingham, UK in 1977, where Maqbool Bhat was clearly not present. But it was an ideological successor to the National Liberation Front and, so, sometimes identified with it. The names are ambiguous. The NLF was also referred to as "Kashmir National Liberation Front" (Snedden, Kashmir: The Unwritten History 2013, p. 194) and the JKLF was often called "Kashmir Liberation Front". In any case, Maqbool Bhat is often regarded as a co-founder of the JKLF.

- The name also appears as "Amir Ahmad" in some places.

- Gh. Rasool Bhat states that Kala Khan received a life sentence in the trial. But other sources state that he was killed during the shoot out.

References

- "The long, deadly trek to Sunjuwan". The Hindu. 14 February 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- Handoo, Bilal (11 February 2018). "What fuelled Kashmir's Maqbool Butt". Free Press Kashmir.

- Mushtaq, Sheikh (11 February 2011). "Kashmir seeks return of hanged separatist leader's remains". Reuters. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019.

- Zafar Meraj, Inderjit Badhwar, Discontent brewing in Kashmir for two years again finds expression in violence, India Today, 30 April 1989.

- ^ Bhat, Social Background and Political Ideology (2015), Sec. 1.

- ^ Bhat, Social Background and Political Ideology (2015), Sec. 2.

- ^ Shams Rehman, Remembering Amanullah Khan, The Kashmir Walla, 7 May 2016.

- ^ Abdul Khaliq Ansari passes away, Greater Kashmir, 17 June 2013.

- Jamal, Shadow War 2009, pp. 87–88.

- Swami, India, Pakistan and the Secret Jihad 2007, pp. 104, 107.

- ^ Jamal, Shadow War 2009, pp. 88–89.

- Swami, India, Pakistan and the Secret Jihad 2007, pp. 104–105.

- Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict 2003, pp. 114–115.

- Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict 2003, p. 115.

- Swami, India, Pakistan and the Secret Jihad 2007, pp. 107–108.

- Jamal, Shadow War 2009, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Statement of Advocate Abdul Khaliq Ansari before ‘Azad Kashmir" High Court in 1971, Jammu Kashmir Democratic Liberation Party, 8 June 2015.

- ^ Swami, India, Pakistan and the Secret Jihad 2007, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Swami, India, Pakistan and the Secret Jihad 2007, pp. 112–113.

- Jamal, Shadow War 2009, p. 92-93.

- Jamal, Shadow War 2009, p. 94-95.

- Jamal, Shadow War 2009, p. 96-97.

- In Amanullah Khan's death Kashmiri separatism lost its champion, Catch News, 27 April 2016.

- Swami, India, Pakistan and the Secret Jihad 2007, p. 129.

- Swami, India, Pakistan and the Secret Jihad 2007, pp. 129–130.

- Faheem, Dead Men Do Tell Tales (2013), p. 19, col. 1.

- ^ Mark Fineman, Militant Leader is Executed in India, Philadelphia Inquirer, 12 February 1984. ProQuest 1819978361

- Faheem, Dead Men Do Tell Tales (2013), p. 19, col. 2.

- ^ Faheem, Dead Men Do Tell Tales (2013), p. 19, col. 1–2.

- "Shutdown on JKLF founder's death anniversary". Zee News. 11 February 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- "JKLF wants all cases against its cadres withdrawn". The Times Of India. 16 January 2013. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013.

- "Media on a Fai ride". Asian Age.

Bibliography

- Bhat, Gh. Rasool (February 2015), "Social Background and Political Ideology of Maqbool Bhat (18th February 1938 – 11th February 1984)", Research Directions, 2 (8), CiteSeerX 10.1.1.672.6784, ISSN 2321-5488

- Jamal, Arif (2009), Shadow War: The Untold Story of Jihad in Kashmir, Melville House, ISBN 978-1-933633-59-6

- Faheem, Farrukh (27 April 2013), "Kashmir: Dead Men Do Tell Tales", Economic and Political Weekly, 48 (17): 18–21, JSTOR 23527180

- Schofield, Victoria (2003) , Kashmir in Conflict, London and New York: I. B. Taurus & Co, ISBN 1860648983

- Snedden, Christopher (2013) , Kashmir: The Unwritten History, HarperCollins India, ISBN 978-9350298985

- Staniland, Paul (2014), Networks of Rebellion: Explaining Insurgent Cohesion and Collapse, Cornell University Press, pp. 68–, ISBN 978-0-8014-7102-5

- Swami, Praveen (2007), India, Pakistan and the Secret Jihad: The covert war in Kashmir, 1947-2004, Asian Security Studies, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-40459-4

Further reading

- "Pakistan Moves to Block March By Supporters of a Free Kashmir". The New York Times. 11 February 1992.

- "The Rediff Interview/Jammu and Kashmir Democratic Liberation Front Chief Hashim Qureshi". Rediff.com. 14 February 2001.

External links

| Kashmir separatist movement | |

|---|---|

| Political parties | |

| Militant organisations | |

| Separatists |

|

| History | |

| Nationalism | |

| Related | |

- 1938 births

- 1984 deaths

- Kashmiri people

- 20th-century Indian Muslims

- Kashmiri Muslims

- 20th-century criminals

- Kashmiri militants

- People convicted of murder by India

- People executed for murder

- Terrorism in Jammu and Kashmir

- People from Kupwara district

- Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front

- University of Peshawar alumni

- Indian expatriates in Pakistan

- Kashmiri independence activists

- 1966 murders in India

- Inmates of Tihar Jail

- People executed by India by hanging

- Indian people imprisoned on terrorism charges

- Executed Indian people

- People convicted on terrorism charges