Medical condition

| Coeliac disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Coeliac sprue, nontropical sprue, endemic sprue, gluten enteropathy |

| |

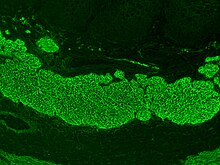

| Biopsy of small bowel showing coeliac disease manifested by blunting of villi, crypt hyperplasia, and lymphocyte infiltration of crypts | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology, internal medicine |

| Symptoms | None or non-specific, abdominal distention, diarrhoea, constipation, malabsorption, weight loss, dermatitis herpetiformis |

| Complications | Iron-deficiency anemia, osteoporosis, infertility, cancers, neurological problems, other autoimmune diseases |

| Usual onset | Any age |

| Duration | Lifelong |

| Causes | Reaction to gluten |

| Risk factors | Genetic predisposition, type 1 diabetes, autoimmune thyroid disease, Down and Turner syndrome |

| Diagnostic method | Family history, blood antibody tests, intestinal biopsies, genetic testing, response to gluten withdrawal |

| Differential diagnosis | Inflammatory bowel disease, intestinal parasites, irritable bowel syndrome, cystic fibrosis |

| Treatment | Gluten-free diet |

| Frequency | ~1 in 135 |

Coeliac disease (British English) or celiac disease (American English) is a long-term autoimmune disorder, primarily affecting the small intestine, where individuals develop intolerance to gluten, present in foods such as wheat, rye and barley. Classic symptoms include gastrointestinal problems such as chronic diarrhoea, abdominal distention, malabsorption, loss of appetite, and among children failure to grow normally.

Non-classic symptoms are more common, especially in people older than two years. There may be mild or absent gastrointestinal symptoms, a wide number of symptoms involving any part of the body, or no obvious symptoms. Coeliac disease was first described in childhood; however, it may develop at any age. It is associated with other autoimmune diseases, such as Type 1 diabetes mellitus and Hashimoto's thyroiditis, among others.

Coeliac disease is caused by a reaction to gluten, a group of various proteins found in wheat and in other grains such as barley and rye. Moderate quantities of oats, free of contamination with other gluten-containing grains, are usually tolerated. The occurrence of problems may depend on the variety of oat. It occurs more often in people who are genetically predisposed. Upon exposure to gluten, an abnormal immune response may lead to the production of several different autoantibodies that can affect a number of different organs. In the small bowel, this causes an inflammatory reaction and may produce shortening of the villi lining the small intestine (villous atrophy). This affects the absorption of nutrients, frequently leading to anaemia.

Diagnosis is typically made by a combination of blood antibody tests and intestinal biopsies, helped by specific genetic testing. Making the diagnosis is not always straightforward. About 10% of the time, the autoantibodies in the blood are negative, and many people have only minor intestinal changes with normal villi. People may have severe symptoms and they may be investigated for years before a diagnosis is achieved. As a result of screening, the diagnosis is increasingly being made in people who have no symptoms. Evidence regarding the effects of screening, however, is not sufficient to determine its usefulness. While the disease is caused by a permanent intolerance to gluten proteins, it is distinct from wheat allergy, which is much more rare.

The only known effective treatment is a strict lifelong gluten-free diet, which leads to recovery of the intestinal lining (mucous membrane), improves symptoms, and reduces the risk of developing complications in most people. If untreated, it may result in cancers such as intestinal lymphoma, and a slightly increased risk of early death. Rates vary between different regions of the world, from as few as 1 in 300 to as many as 1 in 40, with an average of between 1 in 100 and 1 in 170 people. It is estimated that 80% of cases remain undiagnosed, usually because of minimal or absent gastrointestinal complaints and lack of knowledge of symptoms and diagnostic criteria. Coeliac disease is slightly more common in women than in men.

Signs and symptoms

The classic symptoms of untreated coeliac disease include diarrhea, steatorrhoea, iron-deficiency anemia, and weight loss or failure to gain weight. Other common symptoms may be subtle or primarily occur in organs other than the bowel itself. It is also possible to have coeliac disease without any of the classic symptoms at all. This has been shown to comprise at least 43% of presentations in children. Further, many adults with subtle disease may only present with fatigue, anaemia or low bone mass. Many undiagnosed individuals who consider themselves asymptomatic are in fact not, but rather have become accustomed to living in a state of chronically compromised health. Indeed, after starting a gluten-free diet and subsequent improvement becomes evident, such individuals are often able to retrospectively recall and recognise prior symptoms of their untreated disease that they had mistakenly ignored.

Gastrointestinal

Diarrhoea that is characteristic of coeliac disease is chronic, sometimes pale, of large volume, and abnormally foul in odor. Abdominal pain, cramping, bloating with abdominal distension (thought to be the result of fermentative production of bowel gas), and mouth ulcers may be present. As the bowel becomes more damaged, a degree of lactose intolerance may develop. Frequently, the symptoms are ascribed to irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), only later to be recognised as coeliac disease. In populations of people with symptoms of IBS, a diagnosis of coeliac disease can be made in about 3.3% of cases, or four times more likely than in general. Screening them for coeliac disease is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), the British Society of Gastroenterology and the American College of Gastroenterology, but is of unclear benefit in North America.

Coeliac disease leads to an increased risk of both adenocarcinoma and lymphoma of the small bowel (enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL) or other non-Hodgkin lymphomas). This risk is also higher in first-degree relatives such as siblings, parents and children. Whether a gluten-free diet brings this risk back to baseline is not clear. Long-standing and untreated disease may lead to other complications, such as ulcerative jejunitis (ulcer formation of the small bowel) and stricturing (narrowing as a result of scarring with obstruction of the bowel).

Malabsorption-related

The changes in the bowel reduce its ability to absorb nutrients, minerals, and the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K.

- Malabsorption of carbohydrates and fats may cause weight loss (or failure to thrive or stunted growth in children) and fatigue or lack of energy.

- Anaemia may develop in several ways: iron malabsorption may cause iron deficiency anaemia, and folic acid and vitamin B12 malabsorption may give rise to megaloblastic anaemia.

- Calcium and vitamin D malabsorption (and compensatory secondary hyperparathyroidism) may cause osteopenia (decreased mineral content of the bone) or osteoporosis (bone weakening and risk of fragility fractures).

- Selenium malabsorption in coeliac disease, combined with low selenium content in many gluten-free foods, confers a risk of selenium deficiency.

- Copper and zinc deficiencies have also been associated with coeliac disease.

- A small proportion of people have abnormal coagulation because of vitamin K deficiency and are at a slight risk of abnormal bleeding.

Miscellaneous

Coeliac disease has been linked with many conditions. In many cases, it is unclear whether the gluten-induced bowel disease is a causative factor or whether these conditions share a common predisposition.

- IgA deficiency is present in 2.3% of people with coeliac disease, and is itself associated with a tenfold increased risk of coeliac disease. Other features of this condition are an increased risk of infections and autoimmune disease.

- Dermatitis herpetiformis, an itchy cutaneous condition that has been linked to a transglutaminase enzyme in the skin, features small-bowel changes identical to those in coeliac disease and may respond to gluten withdrawal even if no gastrointestinal symptoms are present.

- Growth failure and/or pubertal delay in later childhood can occur even without obvious bowel symptoms or severe malnutrition. Evaluation of growth failure often includes coeliac screening.

- Pregnancy complications can occur if coeliac disease is pre-existing or later acquired, with significant outcomes including miscarriage, intrauterine growth restriction, low birthweight and preterm birth.

- Hyposplenism (a small and underactive spleen) occurs in about a third of cases and may predispose to infection given the role of the spleen in protecting against harmful bacteria.

- Abnormal liver function tests (randomly detected on blood tests) may be seen.

- Depression, anxiety and other mental health disorders

Coeliac disease is associated with several other medical conditions, many of which are autoimmune disorders: diabetes mellitus type 1, hypothyroidism, primary biliary cholangitis, microscopic colitis, gluten ataxia, psoriasis, vitiligo, autoimmune hepatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, and more.

Causes

Coeliac disease is caused by an inflammatory reaction to gliadins and glutenins (gluten proteins) found in wheat and to similar proteins found in the crops of the tribe Triticeae (which includes other common grains such as barley and rye) and to the tribe Aveneae (oats). Wheat subspecies (such as spelt, durum, and Kamut) and wheat hybrids (such as triticale) also cause symptoms of coeliac disease.

A small number of people with coeliac disease react to oats. Oat toxicity in coeliac people depends on the oat cultivar consumed because the prolamin genes, protein amino acid sequences, and the immunoreactivities of toxic prolamins are different in different oat varieties. Also, oats are frequently cross-contaminated with other grains containing gluten. The term "pure oats" refers to oats uncontaminated with other gluten-containing cereals. The long-term effects of pure oat consumption are still unclear, and further studies identifying the cultivars used are needed before making final recommendations on their inclusion in a gluten-free diet. Coeliac people who choose to consume oats need a more rigorous lifelong follow-up, possibly including periodic intestinal biopsies.

Other grains

Other cereals such as corn, millet, sorghum, teff, rice, and wild rice are safe for people with coeliac disease to consume, as well as non-cereals such as amaranth, quinoa, and buckwheat. Noncereal carbohydrate-rich foods such as potatoes and bananas do not contain gluten and do not trigger symptoms.

Risk modifiers

There are various theories as to what determines whether a genetically susceptible individual will go on to develop coeliac disease. Major theories include surgery, pregnancy, infection and emotional stress.

The eating of gluten early in a baby's life does not appear to increase the risk of coeliac disease but later introduction after six months may increase it. There is uncertainty whether being breastfed reduces risk. Prolonging breastfeeding until the introduction of gluten-containing grains into the diet appears to be associated with a 50% reduced risk of developing coeliac disease in infancy; whether this persists into adulthood is not clear. These factors may just influence the timing of onset.

Mechanism

Coeliac disease appears to be multifactorial, both in that more than one genetic factor can cause the disease and in that more than one factor is necessary for the disease to manifest in a person.

Almost all people (95%) with coeliac disease have either the variant HLA-DQ2 allele or (less commonly) the HLA-DQ8 allele. However, about 20–30% of people without coeliac disease have also inherited either of these alleles. This suggests that additional factors are needed for coeliac disease to develop; that is, the predisposing HLA risk allele is necessary but not sufficient to develop coeliac disease. Furthermore, around 5% of those people who do develop coeliac disease do not have typical HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 alleles (see below).

Genetics

The vast majority of people with coeliac have one of two types (out of seven) of the HLA-DQ protein. HLA-DQ is part of the MHC class II antigen-presenting receptor (also called the human leukocyte antigen) system and distinguishes cells between self and non-self for the purposes of the immune system. The two subunits of the HLA-DQ protein are encoded by the HLA-DQA1 and HLA-DQB1 genes, located on the short arm of chromosome 6.

There are seven HLA-DQ variants (DQ2 and DQ4–DQ9). Over 95% of people with coeliac have the isoform of DQ2 or DQ8, which is inherited in families. The reason these genes produce an increase in the risk of coeliac disease is that the receptors formed by these genes bind to gliadin peptides more tightly than other forms of the antigen-presenting receptor. Therefore, these forms of the receptor are more likely to activate T lymphocytes and initiate the autoimmune process.

Most people with coeliac bear a two-gene HLA-DQ2 haplotype referred to as DQ2.5 haplotype. This haplotype is composed of two adjacent gene alleles, DQA1*0501 and DQB1*0201, which encode the two subunits, DQ α and DQ β. In most individuals, this DQ2.5 isoform is encoded by one of two chromosomes 6 inherited from parents (DQ2.5cis). Most coeliacs inherit only one copy of this DQ2.5 haplotype, while some inherit it from both parents; the latter are especially at risk for coeliac disease as well as being more susceptible to severe complications.

Some individuals inherit DQ2.5 from one parent and an additional portion of the haplotype (either DQB1*02 or DQA1*05) from the other parent, increasing risk. Less commonly, some individuals inherit the DQA1*05 allele from one parent and the DQB1*02 from the other parent (DQ2.5trans) (called a trans-haplotype association), and these individuals are at similar risk for coeliac disease as those with a single DQ2.5-bearing chromosome 6, but in this instance, the disease tends not to be familial. Among the 6% of European coeliacs that do not have DQ2.5 (cis or trans) or DQ8 (encoded by the haplotype DQA1*03:DQB1*0302), 4% have the DQ2.2 isoform, and the remaining 2% lack DQ2 or DQ8.

The frequency of these genes varies geographically. DQ2.5 has high frequency in peoples of North and Western Europe (Basque Country and Ireland with highest frequencies) and portions of Africa and is associated with disease in India, but it is not found along portions of the West Pacific rim. DQ8 has a wider global distribution than DQ2.5 and is particularly common in South and Central America; up to 90% of individuals in certain Amerindian populations carry DQ8 and thus may display the coeliac phenotype.

Other genetic factors have been repeatedly reported in coeliac disease; however, involvement in disease has variable geographic recognition. Only the HLA-DQ loci show a consistent involvement over the global population. Many of the loci detected have been found in association with other autoimmune diseases. One locus, the LPP or lipoma-preferred partner gene, is involved in the adhesion of extracellular matrix to the cell surface, and a minor variant (SNP=rs1464510) increases the risk of disease by approximately 30%. This gene strongly associates with coeliac disease (p < 10) in samples taken from a broad area of Europe and the US.

The prevalence of coeliac disease genotypes in the modern population is not completely understood. Given the characteristics of the disease and its apparent strong heritability, it would normally be expected that the genotypes would undergo negative selection and to be absent in societies where agriculture has been practised the longest (compare with a similar condition, lactose intolerance, which has been negatively selected so strongly that its prevalence went from ~100% in ancestral populations to less than 5% in some European countries). This expectation was first proposed by Simoons (1981). By now, however, it is apparent that this is not the case; on the contrary, there is evidence of positive selection in coeliac disease genotypes. It is suspected that some of them may have been beneficial by providing protection against bacterial infections.

Prolamins

The majority of the proteins in food responsible for the immune reaction in coeliac disease are the prolamins. These are storage proteins rich in proline (prol-) and glutamine (-amin) that dissolve in alcohols and are resistant to proteases and peptidases of the gut. Prolamins are found in cereal grains with different grains having different but related prolamins: wheat (gliadin), barley (hordein), rye (secalin) and oats (avenin). One region of α-gliadin stimulates membrane cells, enterocytes, of the intestine to allow larger molecules around the sealant between cells. Disruption of tight junctions allow peptides larger than three amino acids to enter the intestinal lining.

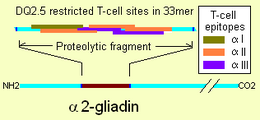

Membrane leaking permits peptides of gliadin that stimulate two levels of the immune response: the innate response, and the adaptive (T-helper cell-mediated) response. One protease-resistant peptide from α-gliadin contains a region that stimulates lymphocytes and results in the release of interleukin-15. This innate response to gliadin results in immune-system signalling that attracts inflammatory cells and increases the release of inflammatory chemicals. The strongest and most common adaptive response to gliadin is directed toward an α2-gliadin fragment of 33 amino acids in length.

The response to the 33mer occurs in most coeliacs who have a DQ2 isoform. This peptide, when altered by intestinal transglutaminase, has a high density of overlapping T-cell epitopes. This increases the likelihood that the DQ2 isoform will bind, and stay bound to, peptide when recognised by T-cells. Gliadin in wheat is the best-understood member of this family, but other prolamins exist, and hordein (from barley), secalin (from rye), and avenin (from oats) may contribute to coeliac disease. Avenin's toxicity in people with coeliac disease depends on the oat cultivar consumed, as prolamin genes, protein amino acid sequences, and the immunoreactivities of toxic prolamins vary among oat varieties.

Tissue transglutaminase

Anti-transglutaminase antibodies to the enzyme tissue transglutaminase (tTG) are found in the blood of the majority of people with classic symptoms and complete villous atrophy, but only in 70% of the cases with partial villous atrophy and 30% of the cases with minor mucosal lesions. Tissue transglutaminase modifies gluten peptides into a form that may stimulate the immune system more effectively. These peptides are modified by tTG in two ways, deamidation or transamidation.

Deamidation is the reaction by which a glutamate residue is formed by cleavage of the epsilon-amino group of a glutamine side chain. Transamidation, which occurs three times more often than deamidation, is the cross-linking of a glutamine residue from the gliadin peptide to a lysine residue of tTg in a reaction that is catalysed by the transglutaminase. Crosslinking may occur either within or outside the active site of the enzyme. The latter case yields a permanently covalently linked complex between the gliadin and the tTg. This results in the formation of new epitopes believed to trigger the primary immune response by which the autoantibodies against tTg develop.

Stored biopsies from people with suspected coeliac disease have revealed that autoantibody deposits in the subclinical coeliacs are detected prior to clinical disease. These deposits are also found in people who present with other autoimmune diseases, anaemia, or malabsorption phenomena at a much increased rate over the normal population. Endomysial components of antibodies (EMA) to tTG are believed to be directed toward cell-surface transglutaminase, and these antibodies are still used in confirming a coeliac disease diagnosis. However, a 2006 study showed that EMA-negative people with coeliac tend to be older males with more severe abdominal symptoms and a lower frequency of "atypical" symptoms, including autoimmune disease. In this study, the anti-tTG antibody deposits did not correlate with the severity of villous destruction. These findings, coupled with work showing that gliadin has an innate response component, suggest that gliadin may be more responsible for the primary manifestations of coeliac disease, whereas tTG is a bigger factor in secondary effects such as allergic responses and secondary autoimmune diseases. In a large percentage of people with coeliac, the anti-tTG antibodies also recognise a rotavirus protein called VP7. These antibodies stimulate monocyte proliferation, and rotavirus infection might explain some early steps in the cascade of immune cell proliferation.

Indeed, earlier studies of rotavirus damage in the gut showed this causes villous atrophy. This suggests that viral proteins may take part in the initial flattening and stimulate self-crossreactive anti-VP7 production. Antibodies to VP7 may also slow healing until the gliadin-mediated tTG presentation provides a second source of crossreactive antibodies.

Other intestinal disorders may have biopsy that look like coeliac disease including lesions caused by Candida.

Villous atrophy and malabsorption

The inflammatory process, mediated by T cells, leads to disruption of the structure and function of the small bowel's mucosal lining and causes malabsorption as it impairs the body's ability to absorb nutrients, minerals, and fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K from food. Lactose intolerance may be present due to the decreased bowel surface and reduced production of lactase but typically resolves once the condition is treated.

Alternative causes of this tissue damage have been proposed and involve the release of interleukin 15 and activation of the innate immune system by a shorter gluten peptide (p31–43/49). This would trigger killing of enterocytes by lymphocytes in the epithelium. The villous atrophy seen on biopsy may also be due to unrelated causes, such as tropical sprue, giardiasis and radiation enteritis. While positive serology and typical biopsy are highly suggestive of coeliac disease, lack of response to the diet may require these alternative diagnoses to be considered.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is often difficult and as of 2019, there continues to be a lack of awareness among physicians about the variability of presentations of coeliac disease and the diagnostic criteria, such that most cases are diagnosed with great delay. It can take up to 12 years to receive a diagnosis from the onset of symptoms and the majority of those affected in most countries never receive it.

Several tests can be used. The level of symptoms may determine the order of the tests, but all tests lose their usefulness if the person is already eating a gluten-free diet. Intestinal damage begins to heal within weeks of gluten being removed from the diet, and antibody levels decline over months. For those who have already started on a gluten-free diet, it may be necessary to perform a rechallenge with some gluten-containing food in one meal a day over six weeks before repeating the investigations.

Blood tests

Serological blood tests are the first-line investigation required to make a diagnosis of coeliac disease. Its sensitivity correlates with the degree of histological lesions. People who present with minor damage to the small intestine may have seronegative findings so many patients with coeliac disease often are missed. In patients with villous atrophy, anti-endomysial (EMA) antibodies of the immunoglobulin A (IgA) type can detect coeliac disease with a sensitivity and specificity of 90% and 99%, respectively. Serology for anti-transglutaminase antibodies (anti-tTG) was initially reported to have a higher sensitivity (99%) and specificity (>90%). However, it is now thought to have similar characteristics to anti-endomysial antibodies. Both anti-transglutaminase and anti-endomysial antibodies have high sensitivity to diagnose people with classic symptoms and complete villous atrophy, but they are only found in 30–89% of the cases with partial villous atrophy and in less than 50% of the people who have minor mucosal lesions (duodenal lymphocytosis) with normal villi.

Tissue transglutaminase (abbreviated as tTG or TG2) modifies gluten peptides into a form that may stimulate the immune system more effectively. These peptides are modified by tTG in two ways, deamidation or transamidation. Modern anti-tTG assays rely on a human recombinant protein as an antigen. tTG testing should be done first as it is an easier test to perform. An equivocal result on tTG testing should be followed by anti-endomysial antibodies.

Guidelines recommend that a total serum IgA level is checked in parallel, as people with coeliac with IgA deficiency may be unable to produce the antibodies on which these tests depend ("false negative"). In those people, IgG antibodies against transglutaminase (IgG-tTG) may be diagnostic.

If all these antibodies are negative, then anti-DGP antibodies (antibodies against deamidated gliadin peptides) should be determined. IgG class anti-DGP antibodies may be useful in people with IgA deficiency. In children younger than two years, anti-DGP antibodies perform better than anti-endomysial and anti-transglutaminase antibodies tests.

Because of the major implications of a diagnosis of coeliac disease, professional guidelines recommend that a positive blood test is still followed by an endoscopy/gastroscopy and biopsy. A negative serology test may still be followed by a recommendation for endoscopy and duodenal biopsy if clinical suspicion remains high.

Historically three other antibodies were measured: anti-reticulin (ARA), anti-gliadin (AGA) and anti-endomysial (EMA) antibodies. ARA testing, however, is not accurate enough for routine diagnostic use. Serology may be unreliable in young children, with anti-gliadin performing somewhat better than other tests in children under five. Serology tests are based on indirect immunofluorescence (reticulin, gliadin and endomysium) or ELISA (gliadin or tissue transglutaminase, tTG).

Other antibodies such as anti–Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies occur in some people with coeliac disease but also occur in other autoimmune disorders and about 5% of those who donate blood.

Antibody testing may be combined with HLA testing if the diagnosis is unclear. TGA and EMA testing are the most sensitive serum antibody tests, but as a negative HLA-DQ type excludes the diagnosis of coeliac disease, testing also for HLA-DQ2 or DQ8 maximises sensitivity and negative predictive values. In the United Kingdom, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) does not (as of 2015) recommend the use of HLA typing to rule out coeliac disease outside of a specialist setting, for example, in children who are not having a biopsy, or in patients who already have limited gluten ingestion and opt not to have a gluten challenge.

Endoscopy

An upper endoscopy with biopsy of the duodenum (beyond the duodenal bulb) or jejunum is performed to obtain multiple samples (four to eight) from the duodenum. Not all areas may be equally affected; if biopsies are taken from healthy bowel tissue, the result would be a false negative. Even in the same bioptic fragment, different degrees of damage may be present.

Most people with coeliac disease have a small intestine that appears to be normal on endoscopy before the biopsies are examined. However, five findings have been associated with high specificity for coeliac disease: scalloping of the small bowel folds (pictured), paucity in the folds, a mosaic pattern to the mucosa (described as a "cracked-mud" appearance), prominence of the submucosa blood vessels, and a nodular pattern to the mucosa.

European guidelines suggest that in children and adolescents with symptoms compatible with coeliac disease, the diagnosis can be made without the need for intestinal biopsy if anti-tTG antibodies titres are very high (10 times the upper limit of normal).

Until the 1970s, biopsies were obtained using metal capsules attached to a suction device. The capsule was swallowed and allowed to pass into the small intestine. After x-ray verification of its position, suction was applied to collect part of the intestinal wall inside the capsule. Often-utilised capsule systems were the Watson capsule and the Crosby–Kugler capsule. This method has now been largely replaced by fibre-optic endoscopy, which carries a higher sensitivity and a lower frequency of errors.

Capsule endoscopy (CE) allows identification of typical mucosal changes observed in coeliac disease but has a lower sensitivity compared to regular endoscopy and histology. CE is therefore not the primary diagnostic tool for coeliac disease. However, CE can be used for diagnosing T-cell lymphoma, ulcerative jejunoileitis, and adenocarcinoma in refractory or complicated coeliac disease.

Pathology

The classic pathology changes of coeliac disease in the small bowel are categorised by the "Marsh classification":

- Marsh stage 0: normal mucosa

- Marsh stage 1: increased number of intra-epithelial lymphocytes (IELs), usually exceeding 20 per 100 enterocytes

- Marsh stage 2: a proliferation of the crypts of Lieberkühn

- Marsh stage 3: partial or complete villous atrophy and crypt hyperplasia

- Marsh stage 4: hypoplasia of the small intestine architecture

Marsh's classification, introduced in 1992, was subsequently modified in 1999 to six stages, where the previous stage 3 was split in three substages. Further studies demonstrated that this system was not always reliable and that the changes observed in coeliac disease could be described in one of three stages:

- A representing lymphocytic infiltration with normal villous appearance;

- B1 describing partial villous atrophy; and

- B2 describing complete villous atrophy.

The changes classically improve or reverse after gluten is removed from the diet. However, most guidelines do not recommend a repeat biopsy unless there is no improvement in the symptoms on diet. In some cases, a deliberate gluten challenge, followed by a biopsy, may be conducted to confirm or refute the diagnosis. A normal biopsy and normal serology after challenge indicates the diagnosis may have been incorrect.

In untreated coeliac disease, villous atrophy is more common in children younger than three years, but in older children and adults, it is common to find minor intestinal lesions (duodenal lymphocytosis) with normal intestinal villi.

Other diagnostic tests

At the time of diagnosis, further investigations may be performed to identify complications, such as iron deficiency (by full blood count and iron studies), folic acid and vitamin B12 deficiency and hypocalcaemia (low calcium levels, often due to decreased vitamin D levels). Thyroid function tests may be requested during blood tests to identify hypothyroidism, which is more common in people with coeliac disease.

Osteopenia and osteoporosis, mildly and severely reduced bone mineral density, are often present in people with coeliac disease, and investigations to measure bone density may be performed at diagnosis, such as dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scanning, to identify the risk of fracture and need for bone protection medication.

Gluten withdrawal

Although blood antibody tests, biopsies, and genetic tests usually provide a clear diagnosis, occasionally the response to gluten withdrawal on a gluten-free diet is needed to support the diagnosis. Currently, gluten challenge is no longer required to confirm the diagnosis in patients with intestinal lesions compatible with coeliac disease and a positive response to a gluten-free diet. Nevertheless, in some cases, a gluten challenge with a subsequent biopsy may be useful to support the diagnosis, for example in people with a high suspicion for coeliac disease, without a biopsy confirmation, who have negative blood antibodies and are already on a gluten-free diet. Gluten challenge is discouraged before the age of 5 years and during pubertal growth. The alternative diagnosis of non-coeliac gluten sensitivity may be made where there is only symptomatic evidence of gluten sensitivity. Gastrointestinal and extraintestinal symptoms of people with non-coeliac gluten sensitivity can be similar to those of coeliac disease, and improve when gluten is removed from the diet, after coeliac disease and wheat allergy are reasonably excluded.

Up to 30% of people often continue having or redeveloping symptoms after starting a gluten-free diet. A careful interpretation of the symptomatic response is needed, as a lack of response in a person with coeliac disease may be due to continued ingestion of small amounts of gluten, either voluntary or inadvertent, or be due to other commonly associated conditions such as small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), lactose intolerance, fructose, sucrose, and sorbitol malabsorption, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, and microscopic colitis, among others. In untreated coeliac disease, these are often transient conditions derived from the intestinal damage. They normally revert or improve several months after starting a gluten-free diet, but may need temporary interventions such as supplementation with pancreatic enzymes, dietary restrictions of lactose, fructose, sucrose or sorbitol containing foods, or treatment with oral antibiotics in the case of associated bacterial overgrowth. In addition to gluten withdrawal, some people need to follow a low-FODMAPs diet or avoid consumption of commercial gluten-free products, which are usually rich in preservatives and additives (such as sulfites, glutamates, nitrates and benzoates) and might have a role in triggering functional gastrointestinal symptoms.

Screening

There is debate as to the benefits of screening. As of 2017, the United States Preventive Services Task Force found insufficient evidence to make a recommendation among those without symptoms. In the United Kingdom, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommend testing for coeliac disease in first-degree relatives of those with the disease already confirmed, in people with persistent fatigue, abdominal or gastrointestinal symptoms, faltering growth, unexplained weight loss or iron, vitamin B12 or folate deficiency, severe mouth ulcers, and with diagnoses of type 1 diabetes, autoimmune thyroid disease, and with newly diagnosed chronic fatigue syndrome and irritable bowel syndrome. Dermatitis herpetiformis is included in other recommendations. The NICE also recommend offering serological testing for coeliac disease in people with metabolic bone disease (reduced bone mineral density or osteomalacia), unexplained neurological disorders (such as peripheral neuropathy and ataxia), fertility problems or recurrent miscarriage, persistently raised liver enzymes with unknown cause, dental enamel defects and with diagnose of Down syndrome or Turner syndrome.

Some evidence has found that early detection may decrease the risk of developing health complications, such as osteoporosis, anaemia, and certain types of cancer, neurological disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and reproductive problems. They thus recommend screening in people with certain health problems.

Serology has been proposed as a screening measure, because the presence of antibodies would detect some previously undiagnosed cases of coeliac disease and prevent its complications in those people. However, serologic tests have high sensitivity only in people with total villous atrophy and have a very low ability to detect cases with partial villous atrophy or minor intestinal lesions. Testing for coeliac disease may be offered to those with commonly associated conditions.

Treatment

Diet

Main article: Gluten-free dietAt present, the only effective treatment is a lifelong gluten-free diet. No medication exists that prevents damage or prevents the body from attacking the gut when gluten is present. Strict adherence to the diet helps the intestines heal, leading to resolution of all symptoms in most cases and, depending on how soon the diet is begun, can also eliminate the heightened risk of osteoporosis and intestinal cancer and in some cases sterility. Compliance to a strict gluten-free diet is difficult for the patient, but evidence has accumulated that a strict gluten-free diet can result in resolution of diarrhea, weight gain and normalization of nutrient malabsorption, with normalization of biopsies in 6 months to 2 years on a gluten-free diet.

Dietitian input is generally requested to ensure the person is aware which foods contain gluten, which foods are safe, and how to have a balanced diet despite the limitations. In many countries, gluten-free products are available on prescription and may be reimbursed by health insurance plans. Gluten-free products are usually more expensive and harder to find than common gluten-containing foods. Since ready-made products often contain traces of gluten, some coeliacs may find it necessary to cook from scratch.

The term "gluten-free" is generally used to indicate a supposed harmless level of gluten rather than a complete absence. The exact level at which gluten is harmless is uncertain and controversial. A recent systematic review tentatively concluded that consumption of less than 10 mg of gluten per day is unlikely to cause histological abnormalities, although it noted that few reliable studies had been done. Regulation of the label "gluten-free" varies. In the European Union, the European Commission issued regulations in 2009 limiting the use of "gluten-free" labels for food products to those with less than 20 mg/kg of gluten, and "very low gluten" labels for those with less than 100 mg/kg. In the United States, the FDA issued regulations in 2013 limiting the use of "gluten-free" labels for food products to those with less than 20 ppm of gluten. The current international Codex Alimentarius standard allows for 20 ppm of gluten in so-called "gluten-free" foods.

Gluten-free diet improves healthcare-related quality of life, and strict adherence to the diet gives more benefit than incomplete adherence. Nevertheless, gluten-free diet does not completely normalise the quality of life.

Vaccination

Even though it is unclear if coeliac patients have a generally increased risk of infectious diseases, they should generally be encouraged to receive all common vaccines against vaccine preventable diseases (VPDs) as the general population. Moreover, some pathogens could be harmful to coeliac patients. According to the European Society for the Study of Celiac Disease (ESsCD), coeliac disease can be associated with hyposplenism or functional asplenia, which could result in impaired immunity to encapsulated bacteria, with an increased risk of such infections. For this reason, patients who are known to be hyposplenic should be offered at least the pneumococcal vaccine. However, the ESsCD states that it is not clear whether vaccination with the conjugated vaccine is preferable in this setting and whether additional vaccination against Haemophilus, meningococcus, and influenza should be considered if not previously given. However, Mårild et al. suggested considering additional vaccination against influenza because of an observed increased risk of hospital admission for this infection in celiac patients.

Refractory disease

Between 0.3% and 10% of affected people have refractory disease, which means that they have persistent villous atrophy on a gluten-free diet despite the lack of gluten exposure for more than 12 months. Nevertheless, inadvertent exposure to gluten is the main cause of persistent villous atrophy, and must be ruled out before a diagnosis of refractory disease is made. People with poor basic education and understanding of gluten-free diet often believe that they are strictly following the diet, but are making regular errors. Also, a lack of symptoms is not a reliable indicator of intestinal recuperation.

If alternative causes of villous atrophy have been eliminated, steroids or immunosuppressants (such as azathioprine) may be considered in this scenario.

Refractory coeliac disease should not be confused with the persistence of symptoms despite gluten withdrawal caused by transient conditions derived from the intestinal damage, which generally revert or improve several months after starting a gluten-free diet, such as small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, lactose intolerance, fructose, sucrose, and sorbitol malabsorption, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, and microscopic colitis among others.

Refractory celiac disease can be divided in type I and II. A recent studied compared patients with type I and II. Refractory celiac disease type I more frequently exhibits diarrhea, anemia, hypoalbuminemia, parenteral nutrition need, ulcerative jejuno-ileitis, and extended small intestinal atrophy. Among patients with refractory celiac disease type II is more common to develope lymphoma. Among these patients, atrophy extension was the only parameter correlated with hypoalbuminemia and mortality.

Epidemiology

Globally coeliac disease affects between 1 in 100 and 1 in 170 people. Rates, however, vary between different regions of the world from as few as 1 in 300 to as many as 1 in 40. In the United States it is thought to affect between 1 in 1750 (defined as clinical disease including dermatitis herpetiformis with limited digestive tract symptoms) to 1 in 105 (defined by presence of IgA TG in blood donors). Due to variable signs and symptoms it is believed that about 85% of people affected are undiagnosed. The percentage of people with clinically diagnosed disease (symptoms prompting diagnostic testing) is 0.05–0.27% in various studies. However, population studies from parts of Europe, India, South America, Australasia and the USA (using serology and biopsy) indicate that the percentage of people with the disease may be between 0.33 and 1.06% in children (but 5.66% in one study of children of the predisposed Sahrawi people) and 0.18–1.2% in adults. Among those in primary care populations who report gastrointestinal symptoms, the rate of coeliac disease is about 3%. In Australia, approximately 1 in 70 people have the disease. The rate amongst adult blood donors in Iran, Israel, Syria and Turkey is 0.60%, 0.64%, 1.61% and 1.15%, respectively.

People of African, Japanese and Chinese descent are rarely diagnosed; this reflects a much lower prevalence of the genetic risk factors, such as HLA-B8. People of Indian ancestry seem to have a similar risk to those of Western Caucasian ancestry. Population studies also indicate that a large proportion of coeliacs remain undiagnosed; this is due, in part, to many clinicians being unfamiliar with the condition and also due to the fact it can be asymptomatic. Coeliac disease is slightly more common in women than in men. A large multicentre study in the U.S. found a prevalence of 0.75% in not-at-risk groups, rising to 1.8% in symptomatic people, 2.6% in second-degree relatives (like grandparents, aunt or uncle, grandchildren, etc.) of a person with coeliac disease and 4.5% in first-degree relatives (siblings, parents or children). This profile is similar to the prevalence in Europe. Other populations at increased risk for coeliac disease, with prevalence rates ranging from 5% to 10%, include individuals with Down and Turner syndromes, type 1 diabetes, and autoimmune thyroid disease, including both hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid) and hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid).

Historically, coeliac disease was thought to be rare, with a prevalence of about 0.02%. The reason for the recent increases in the number of reported cases is unclear. It may be at least in part due to changes in diagnostic practice. There also appears to be an approximately 4.5 fold true increase that may be due to less exposure to bacteria and other pathogens in Western environments. In the United States, the median age at diagnosis is 38 years. Roughly 20 percent of individuals with coeliac disease are diagnosed after 60 years of age.

History

The term coeliac comes from Greek κοιλιακός (koiliakós) 'abdominal' and was introduced in the 19th century in a translation of what is generally regarded as an Ancient Greek description of the disease by Aretaeus of Cappadocia.

Humans first started to cultivate grains in the Neolithic period (beginning about 9500 BCE) in the Fertile Crescent in Western Asia, and, likely, coeliac disease did not occur before this time. Aretaeus of Cappadocia, living in the second century in the same area, recorded a malabsorptive syndrome with chronic diarrhoea, causing a debilitation of the whole body. His "Cœliac Affection" gained the attention of Western medicine when Francis Adams presented a translation of Aretaeus's work at the Sydenham Society in 1856. The patient described in Aretaeus' work had stomach pain and was atrophied, pale, feeble, and incapable of work. The diarrhoea manifested as loose stools that were white, malodorous, and flatulent, and the disease was intractable and liable to periodic return. The problem, Aretaeus believed, was a lack of heat in the stomach necessary to digest the food and a reduced ability to distribute the digestive products throughout the body, this incomplete digestion resulting in diarrhoea. He regarded this as an affliction of the old and more commonly affecting women, explicitly excluding children. The cause, according to Aretaeus, was sometimes either another chronic disease or even consuming "a copious draught of cold water."

The paediatrician Samuel Gee gave the first modern-day description of the condition in children in a lecture at Hospital for Sick Children, Great Ormond Street, London, in 1887. Gee acknowledged earlier descriptions and terms for the disease and adopted the same term as Aretaeus (coeliac disease). He perceptively stated: "If the patient can be cured at all, it must be by means of diet." Gee recognised that milk intolerance is a problem with coeliac children and that highly starched foods should be avoided. However, he forbade rice, sago, fruit, and vegetables, which all would have been safe to eat, and he recommended raw meat as well as thin slices of toasted bread. Gee highlighted particular success with a child "who was fed upon a quart of the best Dutch mussels daily." However, the child could not bear this diet for more than one season.

Christian Archibald Herter, an American physician, wrote a book in 1908 on children with coeliac disease, which he called "intestinal infantilism". He noted their growth was retarded and that fat was better tolerated than carbohydrate. The eponym Gee-Herter disease was sometimes used to acknowledge both contributions. Sidney V. Haas, an American paediatrician, reported positive effects of a diet of bananas in 1924. This diet remained in vogue until the actual cause of coeliac disease was determined.

While a role for carbohydrates had been suspected, the link with wheat was not made until the 1940s by the Dutch paediatrician Dr Willem Karel Dicke. It is likely that clinical improvement of his patients during the Dutch famine of 1944 (during which flour was scarce) may have contributed to his discovery. Dicke noticed that the shortage of bread led to a significant drop in the death rate among children affected by coeliac disease from greater than 35% to essentially zero. He also reported that once wheat was again available after the conflict, the mortality rate soared to previous levels. The link with the gluten component of wheat was made in 1952 by a team from Birmingham, England. Villous atrophy was described by British physician John W. Paulley in 1954 on samples taken at surgery. This paved the way for biopsy samples taken by endoscopy.

Throughout the 1960s, other features of coeliac disease were elucidated. Its hereditary character was recognised in 1965. In 1966, dermatitis herpetiformis was linked to gluten sensitivity.

Society and culture

See also: List of people diagnosed with coeliac diseaseMay has been designated as "Coeliac Awareness Month" by several coeliac organisations.

Christian churches and the Eucharist

Speaking generally, the various denominations of Christians celebrate a Eucharist in which a wafer or small piece of sacramental bread from wheat bread is blessed and then eaten. A typical wafer weighs about half a gram. Wheat flour contains around 10–13% gluten, so a single communion wafer may have more than 50 mg of gluten, an amount that harms many people with coeliac, especially if consumed every day (see Diet above).

Many Christian churches offer their communicants gluten-free alternatives, usually in the form of a rice-based cracker or gluten-free bread. These include the United Methodist, Christian Reformed, Episcopal, the Anglican Church (Church of England, UK) and Lutheran. Catholics may receive from the Chalice alone, or ask for gluten-reduced hosts; gluten-free ones however are not considered to still be wheat bread and hence invalid matter.

Roman Catholic position

Roman Catholic doctrine states that for a valid Eucharist, the bread to be used at Mass must be made from wheat. Low-gluten hosts meet all of the Catholic Church's requirements, but they are not entirely gluten free. Requests to use rice wafers have been denied.

The issue is more complex for priests. As a celebrant, a priest is, for the fullness of the sacrifice of the Mass, absolutely required to receive under both species. On 24 July 2003, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith stated, "Given the centrality of the celebration of the Eucharist in the life of a priest, one must proceed with great caution before admitting to Holy Orders those candidates unable to ingest gluten or alcohol without serious harm."

By January 2004, extremely low-gluten Church-approved hosts had become available in the United States, Italy and Australia. As of July 2017, the Vatican still outlawed the use of gluten-free bread for Holy Communion.

Passover

The Jewish festival of Pesach (Passover) may present problems with its obligation to eat Matzah, which is unleavened bread made in a strictly controlled manner from wheat, barley, spelt, oats, or rye.

In addition, many other grains that are normally used as substitutes for people with gluten sensitivity, including rice, are avoided altogether on Passover by Ashkenazi Jews. Many kosher-for-Passover products avoid grains altogether and are therefore gluten-free. Potato starch is the primary starch used to replace the grains.

Spelling

Coeliac disease is the preferred spelling in Commonwealth English, while celiac disease is typically used in North American English.

Research directions

The search for environmental factors that could be responsible for genetically susceptible people becoming intolerant to gluten has resulted in increasing research activity looking at gastrointestinal infections. Research published in April 2017 suggests that an often-symptomless infection by a common strain of reovirus can increase sensitivity to foods such as gluten.

Various treatment approaches are being studied, including some that would reduce the need for dieting. All are still under development, and are not expected to be available to the general public for a while.

Three main approaches have been proposed as new therapeutic modalities for coeliac disease: gluten detoxification, modulation of the intestinal permeability, and modulation of the immune response.

Using genetically engineered wheat species, or wheat species that have been selectively bred to be minimally immunogenic, may allow the consumption of wheat. This, however, could interfere with the effects that gliadin has on the quality of dough.

Alternatively, gluten exposure can be minimised by the ingestion of a combination of enzymes (prolyl endopeptidase and a barley glutamine-specific cysteine endopeptidase (EP-B2)) that degrade the putative 33-mer peptide in the duodenum. Latiglutenase (IMGX003) is a biotheraputic digestive enzyme therapy currently being trialled that aims to degrade gluten proteins and aid gluten digestion. It was shown to mitigate intestinal mucosal damage and reduce the severity and frequency of symptoms in phase 2 clinical trials and is scheduled for phase 3 clinical trials.

Alternative treatments under investigation include the inhibition of zonulin, an endogenous signalling protein linked to increased permeability of the bowel wall and hence increased presentation of gliadin to the immune system. One inhibitor of this pathway is larazotide acetate, which is currently scheduled for phase 3 clinical trials. Other modifiers of other well-understood steps in the pathogenesis of coeliac disease, such as the action of HLA-DQ2 or tissue transglutaminase and the MICA/NKG2D interaction that may be involved in the killing of enterocytes.

Attempts to modulate the immune response concerning coeliac disease are mostly still in phase I of clinical testing; one agent (CCX282-B) has been evaluated in a phase II clinical trial based on small-intestinal biopsies taken from people with coeliac disease before and after gluten exposure.

Although popularly used as an alternative treatment for people with autism, there is no good evidence that a gluten-free diet is of benefit in the treatment of autism. In the subset of autistic people who have gluten sensitivity, there is limited evidence that suggests that a gluten free diet may improve hyperactivity and mental confusion in those with autism.

References

- ^ Fasano A (April 2005). "Clinical presentation of celiac disease in the pediatric population". Gastroenterology (Review). 128 (4 Suppl 1): S68–73. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.015. PMID 15825129.

- "Symptoms & Causes of Celiac Disease | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. June 2016. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ Lebwohl B, Ludvigsson JF, Green PH (October 2015). "Celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity". BMJ (Review). 351: h4347. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4347. PMC 4596973. PMID 26438584.

Celiac disease occurs in about 1% of the population worldwide, although most people with the condition are undiagnosed. It can cause a wide variety of symptoms, both intestinal and extra-intestinal because it is a systemic autoimmune disease that is triggered by dietary gluten. Patients with coeliac disease are at increased risk of cancer, including a twofold to fourfold increased risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and a more than 30-fold increased risk of small intestinal adenocarcinoma, and they have a 1.4-fold increased risk of death.

- ^ Lundin KE, Wijmenga C (September 2015). "Coeliac disease and autoimmune disease-genetic overlap and screening". Nature Reviews. Gastroenterology & Hepatology (Review). 12 (9): 507–15. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2015.136. PMID 26303674. S2CID 24533103.

The abnormal immunological response elicited by gluten-derived proteins can lead to the production of several different autoantibodies, which affect different systems.

- ^ "Celiac disease". World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guidelines. July 2016. Archived from the original on 17 March 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ^ Ciccocioppo R, Kruzliak P, Cangemi GC, Pohanka M, Betti E, Lauret E, et al. (22 October 2015). "The Spectrum of Differences between Childhood and Adulthood Celiac Disease". Nutrients (Review). 7 (10): 8733–51. doi:10.3390/nu7105426. PMC 4632446. PMID 26506381.

Several additional studies in extensive series of coeliac patients have clearly shown that TG2A sensitivity varies depending on the severity of duodenal damage, and reaches almost 100% in the presence of complete villous atrophy (more common in children under three years), 70% for subtotal atrophy, and up to 30% when only an increase in IELs is present. (IELs: intraepithelial lymphocytes)

- ^ Lionetti E, Francavilla R, Pavone P, Pavone L, Francavilla T, Pulvirenti A, et al. (August 2010). "The neurology of coeliac disease in childhood: what is the evidence? A systematic review and meta-analysis". Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 52 (8): 700–7. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03647.x. PMID 20345955.

- ^ Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó IR, Mearin ML, Phillips A, Shamir R, et al. (January 2012). "European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease" (PDF). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr (Practice Guideline). 54 (1): 136–60. doi:10.1097/MPG.0b013e31821a23d0. PMID 22197856. S2CID 15029283. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

Since 1990, the understanding of the pathological processes of CD has increased enormously, leading to a change in the clinical paradigm of CD from a chronic, gluten-dependent enteropathy of childhood to a systemic disease with chronic immune features affecting different organ systems. (...) atypical symptoms may be considerably more common than classic symptoms

- ^ Tovoli F, Masi C, Guidetti E, Negrini G, Paterini P, Bolondi L (March 2015). "Clinical and diagnostic aspects of gluten related disorders". World Journal of Clinical Cases (Review). 3 (3): 275–84. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v3.i3.275. PMC 4360499. PMID 25789300.

- ^ Lindfors K, Ciacci C, Kurppa K, Lundin KE, Makharia GK, Mearin ML, et al. (January 2019). "Coeliac disease". Nature Reviews. Disease Primers. 5 (1): 3. doi:10.1038/s41572-018-0054-z. PMID 30631077. S2CID 5088821.

- ^ Vivas S, Vaquero L, Rodríguez-Martín L, Caminero A (November 2015). "Age-related differences in celiac disease: Specific characteristics of adult presentation". World Journal of Gastrointestinal Pharmacology and Therapeutics (Review). 6 (4): 207–12. doi:10.4292/wjgpt.v6.i4.207. PMC 4635160. PMID 26558154.

In addition, the presence of intraepithelial lymphocytosis and/or villous atrophy and crypt hyperplasia of small-bowel mucosa, and clinical remission after withdrawal of gluten from the diet, are also used for diagnosis antitransglutaminase antibody (tTGA) titers and the degree of histological lesions inversely correlate with age. Thus, as the age of diagnosis increases antibody titers decrease and histological damage is less marked. It is common to find adults without villous atrophy showing only an inflammatory pattern in duodenal mucosa biopsies: Lymphocytic enteritis (Marsh I) or added crypt hyperplasia (Marsh II)

- Ferri FF (2010). Ferri's differential diagnosis : a practical guide to the differential diagnosis of symptoms, signs, and clinical disorders (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Mosby. p. Chapter C. ISBN 978-0323076999.

- ^ See JA, Kaukinen K, Makharia GK, Gibson PR, Murray JA (October 2015). "Practical insights into gluten-free diets". Nature Reviews. Gastroenterology & Hepatology (Review). 12 (10): 580–91. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2015.156. PMID 26392070. S2CID 20270743.

A lack of symptoms and/or negative serological markers are not reliable indicators of mucosal response to the diet. Furthermore, up to 30% of patients continue to have gastrointestinal symptoms despite a strict GFD.122,124 If adherence is questioned, a structured interview by a qualified dietitian can help to identify both intentional and inadvertent sources of gluten.

- ^ Fasano A, Catassi C (December 2012). "Clinical practice. Celiac disease". The New England Journal of Medicine (Review). 367 (25): 2419–26. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1113994. PMID 23252527.

- Newnham ED (2017). "Coeliac disease in the 21st century: Paradigm shifts in the modern age". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 32: 82–85. doi:10.1111/jgh.13704. PMID 28244672. S2CID 46285202.

Presentation of CD with malabsorptive symptoms or malnutrition is now the exception rather than the rule.

- ^ Tonutti E, Bizzaro N (2014). "Diagnosis and classification of celiac disease and gluten sensitivity". Autoimmun Rev. 13 (4–5): 472–6. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.043. PMID 24440147.

- ^ Penagini F, Dilillo D, Meneghin F, Mameli C, Fabiano V, Zuccotti GV (November 2013). "Gluten-free diet in children: an approach to a nutritionally adequate and balanced diet". Nutrients (Review). 5 (11): 4553–65. doi:10.3390/nu5114553. PMC 3847748. PMID 24253052.

- ^ Di Sabatino A, Corazza GR (April 2009). "Coeliac disease". Lancet. 373 (9673): 1480–93. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60254-3. PMID 19394538. S2CID 8415780.

- Pinto-Sánchez MI, Causada-Calo N, Bercik P, Ford AC, Murray JA, Armstrong D, et al. (August 2017). "Safety of Adding Oats to a Gluten-Free Diet for Patients With Celiac Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Clinical and Observational Studies" (PDF). Gastroenterology. 153 (2): 395–409.e3. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.009. PMID 28431885.

- ^ Comino I, Moreno M, Sousa C (November 2015). "Role of oats in celiac disease". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 21 (41): 11825–31. doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i41.11825. PMC 4631980. PMID 26557006.

It is necessary to consider that oats include many varieties, containing various amino acid sequences and showing different immunoreactivities associated with toxic prolamins. As a result, several studies have shown that the immunogenicity of oats varies depending on the cultivar consumed. Thus, it is essential to thoroughly study the variety of oats used in a food ingredient before including it in a gluten-free diet.

- ^ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical guideline 86: Recognition and assessment of coeliac disease. London, 2015.

- ^ Matthias T, Pfeiffer S, Selmi C, Eric Gershwin M (April 2010). "Diagnostic challenges in celiac disease and the role of the tissue transglutaminase-neo-epitope". Clin Rev Allergy Immunol (Review). 38 (2–3): 298–301. doi:10.1007/s12016-009-8160-z. PMID 19629760. S2CID 33661098.

- ^ Lewis NR, Scott BB (July 2006). "Systematic review: the use of serology to exclude or diagnose coeliac disease (a comparison of the endomysial and tissue transglutaminase antibody tests)". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 24 (1): 47–54. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02967.x. PMID 16803602. S2CID 16823218.

- ^ Rostom A, Murray JA, Kagnoff MF (December 2006). "American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute technical review on the diagnosis and management of celiac disease". Gastroenterology (Review). 131 (6): 1981–2002. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.004. PMID 17087937.

- ^ Molina-Infante J, Santolaria S, Sanders DS, Fernández-Bañares F (May 2015). "Systematic review: noncoeliac gluten sensitivity". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics (Review). 41 (9): 807–20. doi:10.1111/apt.13155. PMID 25753138. S2CID 207050854.

Furthermore, seronegativity is more common in coeliac disease patients without villous atrophy (Marsh 1-2 lesions), but these 'minor' forms of coeliac disease may have similar clinical manifestations to those with villous atrophy and may show similar clinical–histological remission with reversal of haematological or biochemical disturbances on a gluten-free diet (GFD).

- ^ Cichewicz AB, Mearns ES, Taylor A, Boulanger T, Gerber M, Leffler DA, et al. (August 2019). "Diagnosis and Treatment Patterns in Celiac Disease". Digestive Diseases and Sciences (Review). 64 (8): 2095–2106. doi:10.1007/s10620-019-05528-3. PMID 30820708. S2CID 71143826.

- ^ Ludvigsson JF, Card T, Ciclitira PJ, Swift GL, Nasr I, Sanders DS, et al. (April 2015). "Support for patients with celiac disease: A literature review". United European Gastroenterology Journal (Review). 3 (2): 146–59. doi:10.1177/2050640614562599. PMC 4406900. PMID 25922674.

- ^ van Heel DA, West J (July 2006). "Recent advances in coeliac disease". Gut (Review). 55 (7): 1037–46. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.075119. PMC 1856316. PMID 16766754.

- ^ Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Barry MJ, Davidson KW, Doubeni CA, et al. (March 2017). "Screening for Celiac Disease: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". JAMA. 317 (12): 1252–1257. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.1462. PMID 28350936. S2CID 205086614.

- Burkhardt JG, Chapa-Rodriguez A, Bahna SL (July 2018). "Gluten sensitivities and the allergist: Threshing the grain from the husks". Allergy. 73 (7): 1359–1368. doi:10.1111/all.13354. PMID 29131356.

- Costantino A, Aversano GM, Lasagni G, Smania V, Doneda L, Vecchi M, et al. (2022). "Diagnostic management of patients reporting symptoms after wheat ingestion". Frontiers in Nutrition. 9. doi:10.3389/fnut.2022.1007007. PMC 9582535. PMID 36276818.

- ^ Lionetti E, Gatti S, Pulvirenti A, Catassi C (June 2015). "Celiac disease from a global perspective". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Gastroenterology (Review). 29 (3): 365–79. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2015.05.004. PMID 26060103.

- ^ Hischenhuber C, Crevel R, Jarry B, Mäki M, Moneret-Vautrin DA, Romano A, et al. (March 2006). "Review article: safe amounts of gluten for patients with wheat allergy or coeliac disease". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 23 (5): 559–75. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02768.x. PMID 16480395. S2CID 9970042.

- Schuppan D, Zimmer KP (December 2013). "The diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 110 (49): 835–46. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2013.0835. PMC 3884535. PMID 24355936.

- Vriezinga SL, Schweizer JJ, Koning F, Mearin ML (September 2015). "Coeliac disease and gluten-related disorders in childhood". Nature Reviews. Gastroenterology & Hepatology (Review). 12 (9): 527–36. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2015.98. PMID 26100369. S2CID 2023530.

- Ferguson R, Basu MK, Asquith P, Cooke WT (January 1976). "Jejunal mucosal abnormalities in patients with recurrent aphthous ulceration". British Medical Journal. 1 (6000): 11–13. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.6000.11. PMC 1638254. PMID 1247715.

- ^ Irvine AJ, Chey WD, Ford AC (January 2017). "Screening for Celiac Disease in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis" (PDF). The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 112 (1): 65–76. doi:10.1038/ajg.2016.466. PMID 27753436. S2CID 269053.

- ^ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical guideline 61: Irritable bowel syndrome. London, 2008.

- Caio G, Volta U, Sapone A, Leffler DA, De Giorgio R, Catassi C, et al. (July 2019). "Celiac disease: a comprehensive current review". BMC Medicine. 17 (1). Springer Nature: 142. doi:10.1186/s12916-019-1380-z. PMC 6647104. PMID 31331324.

- ^ Gujral N, Freeman HJ, Thomson AB (November 2012). "Celiac disease: prevalence, diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 18 (42): 6036–6059. doi:10.3748/wjg.v18.i42.6036. PMC 3496881. PMID 23155333.

- ^ "American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: Celiac Sprue". Gastroenterology. 120 (6): 1522–1525. May 2001. doi:10.1053/gast.2001.24055. PMID 11313323. S2CID 28235994.

- ^ Presutti RJ, Cangemi JR, Cassidy HD, Hill DA (2007). "Celiac disease". Am Fam Physician. 76 (12): 1795–802. PMID 18217518. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2009.

- ^ Pietzak MM (2014). "Dietary supplements in celiac disease". In Rampertab SD, Mullin GE (eds.). Celiac disease. Springer. pp. 137–59. ISBN 978-1-4614-8559-9.

- Cunningham-Rundles C (September 2001). "Physiology of IgA and IgA deficiency". J. Clin. Immunol. 21 (5): 303–9. doi:10.1023/A:1012241117984. PMID 11720003. S2CID 13285781.

- ^ Marks J, Shuster S, Watson AJ (1966). "Small-bowel changes in dermatitis herpetiformis". Lancet. 2 (7476): 1280–2. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(66)91692-8. PMID 4163419.

- Nicolas ME, Krause PK, Gibson LE, Murray JA (August 2003). "Dermatitis herpetiformis". Int. J. Dermatol. 42 (8): 588–600. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01804.x. PMID 12890100. S2CID 42280769.

- ^ Tersigni C, Castellani R, de Waure C, Fattorossi A, De Spirito M, Gasbarrini A, et al. (2014). "Celiac disease and reproductive disorders: meta-analysis of epidemiologic associations and potential pathogenic mechanisms". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (4): 582–93. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu007. hdl:10807/56796. PMID 24619876.

- Ferguson A, Hutton MM, Maxwell JD, Murray D (1970). "Adult coeliac disease in hyposplenic patients". Lancet. 1 (7639): 163–4. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(70)90405-8. PMID 4189238.

- Zingone F, Swift GL, Card TR, Sanders DS, Ludvigsson JF, Bai JC (April 2015). "Psychological morbidity of celiac disease: A review of the literature". United European Gastroenterology Journal. 3 (2): 136–145. doi:10.1177/2050640614560786. PMC 4406898. PMID 25922673.

- Kupfer SS, Jabri B (October 2012). "Pathophysiology of celiac disease". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clinics of North America (Review). 22 (4): 639–660. doi:10.1016/j.giec.2012.07.003. PMC 3872820. PMID 23083984.

Gluten comprises two different protein types, gliadins and glutenins, capable of triggering disease.

- ^ Biesiekierski JR (March 2017). "What is gluten?". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 32 (Suppl 1): 78–81. doi:10.1111/jgh.13703. PMID 28244676. S2CID 6493455.

Similar proteins to the gliadin found in wheat exist as secalin in rye, hordein in barley, and avenins in oats and are collectively referred to as "gluten." Derivatives of these grains such as triticale and malt and other ancient wheat varieties such as spelt and kamut also contain gluten. The gluten found in all of these grains has been identified as the component capable of triggering the immune-mediated disorder, coeliac disease.

- ^ Kupper C (April 2005). "Dietary guidelines and implementation for celiac disease". Gastroenterology. 128 (4 Suppl 1): S121 – S127. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.024. PMID 15825119.

- ^ Penagini F, Dilillo D, Meneghin F, Mameli C, Fabiano V, Zuccotti GV (18 November 2013). "Gluten-free diet in children: an approach to a nutritionally adequate and balanced diet". Nutrients. 5 (11): 4553–65. doi:10.3390/nu5114553. PMC 3847748. PMID 24253052.

- ^ de Souza MC, Deschênes ME, Laurencelle S, Godet P, Roy CC, Djilali-Saiah I (2016). "Pure Oats as Part of the Canadian Gluten-Free Diet in Celiac Disease: The Need to Revisit the Issue". Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol (Review). 2016: 1–8. doi:10.1155/2016/1576360. PMC 4904650. PMID 27446824.

- ^ Haboubi NY, Taylor S, Jones S (October 2006). "Coeliac disease and oats: a systematic review". Postgrad Med J (Review). 82 (972): 672–8. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2006.045443. PMC 2653911. PMID 17068278.

- Gallagher E (2009). Gluten-free Food Science and Technology. Published by John Wiley and Sons. p. 320. ISBN 978-1-4051-5915-9. Archived from the original on 17 June 2009.

- "The Gluten Connection". Health Canada. May 2009. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- Pinto-Sánchez MI, Verdu EF, Liu E, Bercik P, Green PH, Murray JA, et al. (January 2016). "Gluten Introduction to Infant Feeding and Risk of Celiac Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". The Journal of Pediatrics. 168: 132–43.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.09.032. PMID 26500108.

- Ierodiakonou D, Garcia-Larsen V, Logan A, Groome A, Cunha S, Chivinge J, et al. (September 2016). "Timing of Allergenic Food Introduction to the Infant Diet and Risk of Allergic or Autoimmune Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA. 316 (11): 1181–1192. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.12623. hdl:10044/1/40479. PMID 27654604. S2CID 25694792.

- Akobeng AK, Ramanan AV, Buchan I, Heller RF (January 2006). "Effect of breast feeding on risk of coeliac disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 91 (1): 39–43. doi:10.1136/adc.2005.082016. PMC 2083075. PMID 16287899.

- Lionetti E, Castellaneta S, Francavilla R, Pulvirenti A, Tonutti E, Amarri S, et al. (October 2014). "Introduction of gluten, HLA status, and the risk of celiac disease in children". The New England Journal of Medicine (comparative study). 371 (14): 1295–303. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1400697. hdl:2318/155238. PMID 25271602.

- Gnodi E, Meneveri R, Barisani D (2022). "Celiac disease: From genetics to epigenetics". World J Gastroenterol. 28 (4): 449–463. doi:10.3748/wjg.v28.i4.449. PMC 8790554. PMID 35125829.

- Longmore M (2014). Oxford handbook of Clinical Medicine. Oxford University Press. p. 280. ISBN 9780199609628.

- ^ Hadithi M, von Blomberg BM, Crusius JB, Bloemena E, Kostense PJ, Meijer JW, et al. (2007). "Accuracy of serologic tests and HLA-DQ typing for diagnosing celiac disease". Ann. Intern. Med. 147 (5): 294–302. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-147-5-200709040-00003. PMID 17785484. S2CID 24275278.

- Kim C, Quarsten H, Bergseng E, Khosla C, Sollid L (2004). "Structural basis for HLA-DQ2-mediated presentation of gluten epitopes in celiac disease". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 101 (12): 4175–9. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.4175K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0306885101. PMC 384714. PMID 15020763.

- Jores RD, Frau F, Cucca F, Grazia Clemente M, Orrù S, Rais M, et al. (2007). "HLA-DQB1*0201 homozygosis predisposes to severe intestinal damage in celiac disease". Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 42 (1): 48–53. doi:10.1080/00365520600789859. PMID 17190762. S2CID 7675714.

- Karell K, Louka AS, Moodie SJ, Ascher H, Clot F, Greco L, et al. (2003). "HLA types in celiac disease patients not carrying the DQA1*05-DQB1*02 (DQ2) heterodimer: results from the European Genetics Cluster on Celiac Disease". Hum. Immunol. 64 (4): 469–77. doi:10.1016/S0198-8859(03)00027-2. PMID 12651074.

- Michalski JP, McCombs CC, Arai T, Elston RC, Cao T, McCarthy CF, et al. (1996). "HLA-DR, DQ genotypes of celiac disease patients and healthy subjects from the West of Ireland". Tissue Antigens. 47 (2): 127–33. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0039.1996.tb02525.x. PMID 8851726.

- Kaur G, Sarkar N, Bhatnagar S, Kumar S, Rapthap CC, Bhan MK, et al. (2002). "Pediatric celiac disease in India is associated with multiple DR3-DQ2 haplotypes". Hum. Immunol. 63 (8): 677–82. doi:10.1016/S0198-8859(02)00413-5. PMID 12121676.

- Layrisse Z, Guedez Y, Domínguez E, Paz N, Montagnani S, Matos M, et al. (2001). "Extended HLA haplotypes in a Carib Amerindian population: the Yucpa of the Perija Range". Hum Immunol. 62 (9): 992–1000. doi:10.1016/S0198-8859(01)00297-X. PMID 11543901.

- ^ Dubois PC, Trynka G, Franke L, Hunt KA, Romanos J, Curtotti A, et al. (2010). "Multiple common variants for celiac disease influencing immune gene expression". Nature Genetics. 42 (4): 295–302. doi:10.1038/ng.543. PMC 2847618. PMID 20190752.

- Walcher DN, Kretchmer N (1981). Food, nutrition, and evolution: food as an environmental factor in the genesis of human variability. Papers presented at the International Congress of the International Organization for the Study of Human Development, Masson Pub. USA. pp. 179–199. ISBN 978-0-89352-158-5.

- Catassi C (2005). "Where Is Celiac Disease Coming From and Why?". Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition. 40 (3): 279–282. doi:10.1097/01.MPG.0000151650.03929.D5. PMID 15735480. S2CID 12843113.

- Zhernakova A, Elbers CC, Ferwerda B, Romanos J, Trynka G, Dubois PC, et al. (2010). "Evolutionary and functional analysis of celiac risk loci reveals SH2B3 as a protective factor against bacterial infection". American Journal of Human Genetics. 86 (6): 970–7. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.05.004. PMC 3032060. PMID 20560212.

- Green PH, Cellier C (2007). "Celiac disease". N. Engl. J. Med. 357 (17): 1731–43. doi:10.1056/NEJMra071600. PMID 17960014.

- Lammers KM, Lu R, Brownley J, Lu B, Gerard C, Thomas K, et al. (2008). "Gliadin induces an increase in intestinal permeability and zonulin release by binding to the chemokine receptor CXCR3". Gastroenterology. 135 (1): 194–204.e3. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.023. PMC 2653457. PMID 18485912.

- ^ Qiao SW, Bergseng E, Molberg Ø, Xia J, Fleckenstein B, Khosla C, et al. (August 2004). "Antigen presentation to celiac lesion-derived T cells of a 33-mer gliadin peptide naturally formed by gastrointestinal digestion". Journal of Immunology. 173 (3): 1757–1762. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.1757. PMID 15265905. S2CID 24910686.

- Shan L, Qiao SW, Arentz-Hansen H, Molberg Ø, Gray GM, Sollid LM, et al. (2005). "Identification and analysis of multivalent proteolytically resistant peptides from gluten: implications for celiac sprue". J. Proteome Res. 4 (5): 1732–41. doi:10.1021/pr050173t. PMC 1343496. PMID 16212427.

- ^ Skovbjerg H, Norén O, Anthonsen D, Moller J, Sjöström H (2002). "Gliadin is a good substrate of several transglutaminases: possible implication in the pathogenesis of coeliac disease". Scand J Gastroenterol. 37 (7): 812–7. doi:10.1080/713786534. PMID 12190095.

- Fleckenstein B, Molberg Ø, Qiao SW, Schmid DG, von der Mülbe F, Elgstøen K, et al. (2002). "Gliadin T cell epitope selection by tissue transglutaminase in celiac disease. Role of enzyme specificity and pH influence on the transamidation versus deamidation process". J Biol Chem. 277 (37): 34109–34116. doi:10.1074/jbc.M204521200. PMID 12093810. S2CID 7102008.

- Koning F, Schuppan D, Cerf-Bensussan N, Sollid LM (June 2005). "Pathomechanisms in celiac disease". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Gastroenterology. 19 (3): 373–387. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2005.02.003. ISSN 1521-6918. PMID 15925843.

- Mowat AM (2003). "Coeliac disease – a meeting point for genetics, immunology, and protein chemistry". Lancet. 361 (9365): 1290–1292. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12989-3. PMID 12699968. S2CID 10259661.

- Dewar D, Pereira SP, Ciclitira PJ (2004). "The pathogenesis of coeliac disease". Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 36 (1): 17–24. doi:10.1016/S1357-2725(03)00239-5. PMID 14592529.

- Kaukinen K, Peräaho M, Collin P, Partanen J, Woolley N, Kaartinen T, et al. (2005). "Small-bowel mucosal tranglutaminase 2-specific IgA deposits in coeliac disease without villous atrophy: A Prospective and radmonized clinical study". Scand J Gastroenterol. 40 (5): 564–572. doi:10.1080/00365520510023422. PMID 16036509. S2CID 27068601.

- Salmi TT, Collin P, Korponay-Szabó IR, Laurila K, Partanen J, Huhtala H, et al. (2006). "Endomysial antibody-negative coeliac disease: clinical characteristics and intestinal autoantibody deposits". Gut. 55 (12): 1746–53. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.071514. PMC 1856451. PMID 16571636.