This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Transformation in economics refers to a long-term change in dominant economic activity in terms of prevailing relative engagement or employment of able individuals.

Human economic systems undergo a number of deviations and departures from the "normal" state, trend or development. Among them are Disturbance (short-term disruption, temporary disorder), Perturbation (persistent or repeated divergence, predicament, decline or crisis), Deformation (damage, regime change, loss of self-sustainability, distortion), Transformation (long-term change, restructuring, conversion, new “normal”) and Renewal (rebirth, transmutation, corso-ricorso, renaissance, new beginning).

Transformation is a unidirectional and irreversible change in dominant human economic activity (economic sector). Such change is driven by slower or faster continuous improvement in sector productivity growth rate. Productivity growth itself is fueled by advances in technology, inflow of useful innovations, accumulated practical knowledge and experience, levels of education, viability of institutions, quality of decision making and organized human effort. Individual sector transformations are the outcomes of human socio-economic evolution.

Human economic activity has so far undergone at least two fundamental transformations, as the leading sector has changed:

Beyond industry there is no clear pattern now. Some may argue that service sectors (particularly finance) have eclipsed industry, but the evidence is inconclusive and industrial productivity growth remains the main driver of overall economic growth in most national economies.

This evolution naturally proceeds from securing necessary food, through producing useful things, to providing helpful services, both private and public. Accelerating productivity growth rates speed up the transformations, from millennia, through centuries, to decades of the recent era. It is this acceleration which makes transformation relevant economic category of today, more fundamental in its impact than any recession, crisis or depression. The evolution of four forms of capital (Indicated in Fig. 1) accompanies all economic transformations.

Transformation is quite different from accompanying cyclical recessions and crises, despite the similarity of manifested phenomena (unemployment, technology shifts, socio-political discontent, bankruptcies, etc.). However, the tools and interventions used to combat crisis are clearly ineffective for coping with non-cyclical transformations. The problem is whether we face a mere crisis or a fundamental transformation (globalization→relocalization).

Four key forms of capital

Fig. 1 refers to the four transformations through the parallel (and overlapping) evolution of four forms of capital: Natural→Built→Human→Social. These evolved forms of capital present a minimal complex of sustainability and self-sustainability of pre-human and human systems.

Natural capital (N). The nature-produced, renewed and reproduced “resources” of land, water, air, raw materials, biomass and organisms. Natural capital is subject to both renewable and non-renewable depletion, degradation, cultivation, recycling and reuse.

Built capital (B). The man-made physical assets of infrastructures, technologies, buildings and means of transportation. This is the manufactured “hardware” of nations. This national hardware must be continually maintained, renewed and modernized to assure its continued productivity, efficiency and effectiveness.

Human capital (H). The continued investment in people's skills, knowledge, education, health & nutrition, abilities, motivation and effort. This is the “software” and “brainware” of a nation; most important form of capital for developing nations.

Social capital (S). The enabling infrastructure of institutions, civic communities, cultural and national cohesion, collective and family values, trust, traditions, respect and the sense of belonging. This is the voluntary, spontaneous “social order” which cannot be engineered, but its self-production (autopoiesis) can be nurtured, supported and cultivated.

Parallelism of crises and transformations

The triggers that induce the catharsis of a crisis often coincide with and are undistinguishable from the triggers launching qualitative transformations of the economy, business and society at large. While crises are cyclical recessions or slowdowns within the same paradigm, transformation represents a paradigmatic change in the way of doing business: moving towards new standards and quality, in a unique and non-recursive way. Most developed and mature economies of the world (USA, Japan, Western Europe) are undergoing long-term transformation towards a “new normal” of doing business, state governance and ways of life. Cyclical crisis is a parallel, accompanying phenomenon, subject to different causes, special rules and separate dynamics.

Milan Zeleny cautions that confounding crisis and transformation as one phenomenon brings forth the confusion, inconsistency and guessing. While many changes in the market system are cyclical, there are also evolutionary changes which are unidirectional and qualitatively transformational. The transformations of the US economy from agricultural to industrial, or from industrial to services, were not crises, although there were cyclical crises along the way. Transformational “losses” cannot be recovered or regained by definition. Not understanding that is at the core of wasteful spending of rigidly hopeless governmental interventions. Barry Bosworth of the Brookings Institution confirms: “The assumption has always been that the U.S. economy will gain back what was lost in a recession. Academics are coming to the realization that this time is different and that those losses appear permanent and cannot be regained.” In transformations there are no “losses”, only changes and transitions to a new economic order.

Underlying pattern of recessions

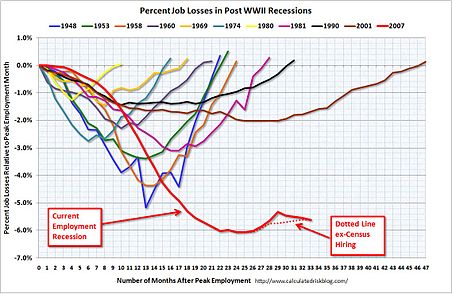

When comparing major US recessions since 1980, as in Fig. 2, it is clear that they have been getting deeper and longer in terms of the recovery of initial employment level. Only the first is classical V shape, there are several W, U and finally L shapes. There clearly is an underlying causal phenomenon which is getting stronger and more persistent over time. Such underlying causation is of interest, as it may signal the prelude and gathering of forces of another emerging transformation.

Looking back, even the Great Depression of the 1930s was not just a crisis, but a long-term transformation from the pre-war industrial economy to the post-war service economy in the U.S. However, in the early 1980s, the service sector had started slowing down its employment absorption and growth potential, ultimately leading to the jobless economy of 2011. No such comparisons with the 1930s are useful: one can compare recessions but not transformations. Industrial economy of 1930s and the post-service economy of 2000s are two different “animals” in two different contexts. It is still not clear what kind of transformation is emerging and eventually replaces the service and public sector economy.

The unrecognized confluence of crisis and transformation, and the inability to separate them, lies at the core of old tools (keynesianism, monetarism) not working properly. The tools for adapting successfully to paradigmatic transformation have not been developed. An example of a paradigmatic transformation would be the shift from geocentric to heliocentric view of our world. Within both views there can be any number of crises, cyclical failures of old and searches for new theories and practices. But there was only one transformation, from geocentric to heliocentric, and there was nothing cyclical about it. It was resisted with all the might of the mighty: remember Galilei and Bruno. While crises are cyclical corrections and adjustments, transformations are evolutionary shifts or even revolutions (industrial, computer) towards new and different levels of existence.

The most important indicator is the arena of employment, especially in the US, providing clues to transformational qualities of the current global crisis phenomena. Persistent rates of unemployment, combined with falling workforce participation rate indicate that also this crisis is intertwined with underlying transformation and so it displays atypical dynamics and unusual persistence, presenting new challenges to conventional economic thought, business practices and government interventional “toolbox”. Sector evolution and dynamics is the key to explaining these phenomena.

Sector dynamics

Economic sectors evolve (in terms of employment levels), albeit through fluctuations, in one general direction (along so called S-curve): they emerge, expand, plateau, contract and exit—just like any self-organizing system or living organism. We are naturally interested in the percentage of total workforce employed in a given sector. The dynamics of this percentage provides clues to where and when are the new jobs generated and old ones abandoned.

Sector's percentage share of employment evolves in dependency on sector's productivity growth rate. Agriculture has emerged and virtually disappeared as a source of net employment. Today, only ½ percent or so of total workforce is employed in US agriculture – the most productive sector of the economy. Manufacturing had emerged, peaked and contracted. Services have emerged and started contracting – all due to incessant, unavoidable and desirable productivity growth rates.

The U.S. absolute manufacturing output has more than tripled over the past 60 years. Because of the productivity growth rates, these goods were produced by ever decreasing number of people. While in 1980-2012 total economic output per hour worked increased 85 percent, in manufacturing output per hour skyrocketed by 189 percent. The number of employees in manufacturing was about a third of total workforce in 1953, about a fifth in 1980, and about a tenth (12 million) in 2012. This decline is now accelerating because of the high-tech automation and robotization.

A public sector of employment has been emerging: government, welfare and unemployment, based on tax-financed consumption rather than added value production, sheltered from market forces, producing public services. (Observe that the unemployed are temporary “employees” of the government, as long as they receive payments.) Creating employment in GWU sector is achievable at the expense of productive sectors, i.e. only at the risk of major debt accumulation, in a non-lasting way and with low added value. Sustaining employment growth in such a sector is severely limited by the growing debt financing.

The Four Basic Sectors

The Four Basic Sectors refers to the current stage of sector evolution, in the sequence of four undergone transformations, namely agriculture, industry, services and GWU (government, welfare and unemployment)

The US economy has become one of the most mature (with Japan and Western Europe) in terms of its sector evolution. It has entered the stage – perhaps as the first economy ever – of declining employment share in both the service and government sectors.

Productivity growth rates are now accelerating in the US services and its employment creation and absorption potential are declining rapidly. Accelerating productivity growth rates are dictated by global competition and human striving for better standards of living – they cannot be stopped at will. In the US there are only three subsectors where net jobs are still being created: education, health care, and government. The first two are subject to market forces and will undergo accelerating productivity growth rates and declining employment levels in the near future. The third one, GWU, is sheltered from competition, cannot expand its share substantially because it depends on taxation from other sectors; its employment growth is unsustainable.

Slowly, the US economy has shifted towards sectors with lower added value, leading to lower real incomes and increasing indebtness. This is a systemic condition which no amount of regulation and Keynesian/monetarist stimuli can effectively address. Even desirable piercing of speculative, employment and debt bubbles has ceased to be politically correct. Even 100% taxation of all incomes would not alleviate US debt.

So, the US is at the transforming cusp and hundreds of years of sector evolution comes to a halt. There are only four essential activities humans can do economically: 1. Produce food, 2. Manufacture goods, 3. Provide services (private and public), and 4. Do nothing. This is why the idea of “basic income”, independent of employment, is being considered e.g. in Switzerland.

US economy has exploited (from employment share viewpoint) all three productive sectors. There is no new sector lurking in the offing: qualitative transformation is taking place. Less developed economies still have time left, some still have to industrialize and some still have the services to expand. But the US economy is now the harbinger of the things to come, the role model for others to follow or reject, but hardly ignore. For the first time in history, this one economy has reached the end of the old model (or paradigm) and is groping to find the new ways of organizing its business, economy and society.

New transformation

In search of the better name, the Bloomberg Businessweek Editor argued as follows:

"You’d expect a better name to have emerged by now. It took remarkable ingenuity to unleash the forces that paralyzed markets, overturned governments, and ruined countless lives, not to mention causing an historic decline in global gross domestic product. For creativity to fail in the summing up is just one more insult. Of course, it’s hard to name what you can’t comprehend."

— Editor's Letter, Businessweek, September 12, 2013

Meanwhile, New Transformation has already well advanced.

In Fig. 3a, observe that the US economy has matured in terms of its sector evolution. It has entered the stage – as the first economy ever – of declining employment in the service and GWU sectors.

As Fig. 3a documents, the US economy has exhausted (from employment viewpoint) all three productive sectors and has reached for the 17% in GWU. In Fig. 3b we separate the last workforce bar from Fig. 3a, in order to see the impact of productivity growth today.

All four sectors are subject to accelerated productivity growth rates in the near future. The only expanding space of the workforce is the grey region “?” in Fig. 3b, essentially reflecting the decline in workforce participation rate. This grey area is also the space of the new transformation: that's where those who left unemployment registers are starting new ventures and enterprises, and participating in regional economies.

This new “transformation” is different from all preceding sector transformations: it does not usher in a new sector but completes the secular cycle of localization→globalization→re-localization. A new economic paradigm is emerging, with a new structure, behavior, institutions and values. A more precise label would be Economic Metamorphosis. Metamorphosis is the outcome of a series of transformations, not dissimilar to a caterpillar-to-butterfly change of form, through the construction→destruction→reconstruction autopoietic self-production cycle.

Even when the recession ends, the metamorphosis of economic form shall continue, accelerate and expand. Less and less we shall be able to tell the difference. Pressures for increased productivity growth rates, declining employment and workforce participation, as well as budget cuts shall grow unabated. Due to massive automation, sector GDP can grow even under the conditions of declining employment. More than that: increasing the minimum wage, historically rather neutral with respect to employment, will now be readily replacing low-level jobs with ever cheaper and more abundant automation - along with millions of jobs being lost due to the still uninformed and aimless political process. Obscuring the difference between cyclical crisis and the ongoing transformation (metamorphosis) is not without consequences: when true diagnosis is not attempted, and people do not know what is happening with their economy and why, all forms of contagious social unrest follow worldwide.

Okun's law

In economics, Okun's law (named after Arthur Melvin Okun), is an empirically observed relationship relating unemployment to losses in a country's production. This correlation "law" states that a 2% decline in output (GDP) will be accompanied by a 1% rise in unemployment. It has been dubbed as “Macroeconomic Mystery”. After holding for the past 40 years, it faltered during current “recovery”. Unemployment shot up faster than predicted, but then it fell more quickly than indicated by slow U.S. growth in 2009–2013. Output grew 2% but unemployment is 7.6% instead of 8.8% expected by this “law”.

The notion of transformation explains this artificial mystery. First, unemployment shot up faster because there are no major sectors absorbing and replacing the loss of jobs. Second, unemployment also falls faster because, due to the long duration of the crisis, the workforce participation rate keeps shrinking (In 2007, 66% were working or seeking job, in 2013 only 63.2%), as can be seen in Fig. 4. In other words, people leaving the workforce are not counted among the unemployed. For example, in summer 2013, on average only 148,000 new jobs per month were created, yet unemployment rate dropped steeply to 7.3%, at the cost of 312,000 people dropping out of the work force. The number of unemployed (i.e. actively seeking jobs) is different from the number of people without work – another sign of fundamental transformation and not just a “crisis”.

The correlation between growth and employment is very tenuous during ongoing transformation. Based on productivity growth rates, GDP could accelerate and yet jobs drop precipitously, due to automation, robotization, digitization and self-service of the transformation era. Also, correlations in economics are always dangerous because they do not prove or establish causal relationships.

Self-service, disintermediation and customization

The new transformational paradigm could be defined by the ongoing self-organization of the market economy itself: its rates of self-service, disintermediation and mass customization are increasing and becoming most effective on local and regional levels. Because there is no new productive sector to emerge, the economy seeks to reinstate its new balance through these new modes of doing business. Producers and providers are outsourcing their production and services to customers and to technology. Outsourcing to customers is a natural and necessary self-organizing process, including disintermediation, customer integration and mass customization, all driven by the global productivity at the cusp of transformation.

Due to its productivity growth rates, each sector must emerge, grow, persist, stagnate, decline and dissipate in terms of its employment generating capacity. The high-productivity growth sectors are emerging and dissipating first, the low-productivity growth sectors (like services) are completing their life cycles only now. Different productivity growth rates in different sectors are accompanied by virtually uniform growth rates in wages and salaries across all sectors, as required by free market forces.

As a consequence, the goods of high productivity growth sectors (food, manufactured goods) are getting cheaper and the products of low productivity growth sectors (health care, education, insurance) are getting more expensive. In many developing nations this may still be the other way around (due to the prevailing stage of sector evolution): food and manufactured goods more expensive, while services still relatively cheap, as captured in the Figure 5:

Rational economics agents tend towards substituting relatively cheaper and capital intensive manufactured goods for relatively more expensive and labor-intensive services. Consumers will use goods instead of services wherever economical and possible. By observing the emergence of automated teller machines instead of bank tellers, self-service gas stations instead of full-service stations, self-driving instead of chauffeurs, do-it-yourself pregnancy kits rather than hospital testing services, self-handled optical scanners rather than cashiers, and cloud computing instead of central mainframes, mature economies are entering the era of self-service, disintermediation and mass customization.

Modern production is primarily based on the processing of information, not on the hauling of goods, humans and machinery over large distances. One can more effectively “haul the information,” to produce goods and provide services locally. Information and knowledge travel effortlessly through electronic superhighways, through telecommunications and social networks over the internet.

Relocalization

See also: Localism (politics)Because there is no new productive sector to emerge, the market system seeks to reinstate its new balance through new modes of doing business. Deglobalization is taking place, supply chains are turning into demand chains, large economies are focusing on their internal markets, outsourcing is followed by “backsourcing”, returning activities back to the countries and locations of their origin. The original slogan of “Think globally, act locally,” is being re-interpreted as exploiting global information and knowledge in local action, under local conditions and contexts.

While globalization refers to a restructuring of the initially distributed and localized world economy into spatially reorganized processes of production and consumption across national economies and political states on a global scale, in deglobalization, people move towards relocalization: the global experience and knowledge becoming embodied in local communities. So, the corso-ricorso of socio-economic transformation is properly captured by a triad Localization → Globalization → Relocalization.

The trend of deglobalization is turning much more significant during these years. The growth of worldwide GDP is now exceeding the overall growth of trade for the first time; foreign investment (Cross Border Capital Flows) is only 60% of their pre-crisis levels and has plunged to some 40 percent. World capital flows include loans and deposits, foreign investments, bonds and equities – all down in their cross-border segment. This means that the rate of globalization has reversed its momentum. Globalizers are still worried about 2014 being the year of irreversible decline. Improvement in the internal growth of U.S.A., EU, and Japan does not carry into external trade – these economies are starting to function as zero-sum.

The income inequality and long-term unemployment lead to re-localized experiments with Guaranteed Minimum Income (to be traced to Thomas Paine) for all citizens. In Switzerland this guarantee would be $33,000 per year, regardless of working or not. Under the name Generation Basic Income it is now subject to Swiss referendum. Unemployment then frees people to pursue their own creative talents.

With this transformation, an entirely new vocabulary is emerging in economics: in addition to deglobalization and relocalization, we also encounter glocalization (adjustment of products to local culture) and local community restoration (regional self-government and direct democracy). With relocalization, an entire new cycle of societal corso-ricorso is brought forth. Local services, local production and local agriculture, based on distributed energy generation, additive manufacturing and vertical farming, are enhancing individual, community and regional autonomy through self-service, disintermediation and mass customization. Both requisite technologies and appropriate business models necessary for relocalization are already in place, forming a vital part of our daily business and life experience. New transformation is well on its way.

See also

- Economic transformation

- Transformation of culture

- Structural change

- Overconsumption

- Fourth Industrial Revolution

- Digital Revolution

- Sharing economy

- Peer production

- Technological unemployment

References

- Zeleny, Milan (November 2010). "Machine/organism dichotomy and free-market economics: Crisis or transformation?". Human Systems Management. 29 (4/2010). IOS Press: P191–204. doi:10.3233/HSM-2010-0725.

- Brendan Greeley (March 2014). "The GDP in 2017 Is Not Looking Good". Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on March 8, 2014.

- Zeleny, Milan (2005). Human Systems Management: Integrating Knowledge, Management & Systems. World Scientific. pp. 136. ISBN 9789810249137.

- Zeleny, Milan (2005). Human Systems Management: Integrating Knowledge, Management & Systems. World Scientific. pp. 79. ISBN 9789810249137.

- Ryan, Frank (April 2011). The Mystery of Metamorphosis: A Scientific Detective Story. Chelsea Green Publishing. ISBN 9781603583213.

- Phil Mullan (February 2013). "Shale: the 'IT bubble' of the 21st century?". Spiked Magazine.

- "Minimum Wage, Wage and Hour Division, Department of Labor".

- "Macroeconomic Mystery". Business Week: P24. 30 September – 6 October 2013.

- Susan Lund; Toos Daruvala; Richard Dobbs (March 2013). "Financial globalization: Retreat or reset?". McKinsey Global Institute.

- Ralph Atkins; Keith Fray (January 2014). "Rapid fall in capital flows poses growth risk". The Financial Times.

- "Thomas Paine". Social Security Administration.

- Marangos, John (January 2006). "Two arguments for Basic Income". History of Economic Ideas.

- Stephan Faris (January 2014). "The Swiss Join the Fight Against Inequality". Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on January 17, 2014.

Further reading

- "The Self-Service Society: A New Scenario of the Future", Planning Review, 7(1979) 3, pp. 3–7, 37–38.

- "Towards a Self-Service Society", Human Systems Management, 1(1980) 1, pp. 1–3.

- "Socio-Economic Foundations of a Self-Service Society", in: Progress in Cybernetics and Systems Research, vol. 10, Hemisphere Publishing, Washington, D.C., 1982, pp. 127–132.

- "Self-Service Trends in the Society", in: Applied Systems and Cybernetics, Vol. 3, edited by G. E. Lasker, Pergamon Press, Elmsford, N.Y., 1981, pp. 1405–1411.

- "Self-Service Aspects of Health Maintenance: Assessment of Current Trends", Human Systems Management, 2(1981) 4, pp. 259–267. (With M. Kochen)

- "The Grand Reversal: On the Corso and Ricorso of Human Way of Life", World Futures, 27(1989), pp. 131–151.

- "Structural Recession in the U.S.A.", Human Systems Management, 11(1992)1, pp. 1–4.

- "Work and Leisure", in: IEBM Handbook on Human Resources Management, Thomson, London, 1997, pp. 333–339. Also: "Bata-System of Management," pp. 359–362.

- "Industrial Districts of Italy: Local-Network Economies in a Global-Market Web", Human Systems Management, 18(1999)2, pp. 65–68.

- "Machine/Organism Dichotomy of Free-Market Economics: Crisis or Transformation?", Human Systems Management, 29(2010)4, pp. 191–204.

- "Genesis of the Worldwide Crisis", in: Atlas of Transformation, JRP Ringier, Zurich, 2010.

- "Crisis or Transformation: On the corso and ricorso of human systems", Human Systems Management, 31(2012)1, pp. 49–63.