| This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (July 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Sakutarō Hagiwara | |

|---|---|

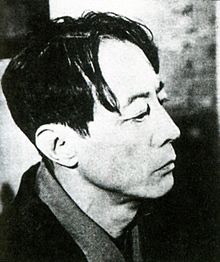

Sakutarō Hagiwara Sakutarō Hagiwara | |

| Born | (1886-11-01)1 November 1886 Maebashi, Gumma, Japan |

| Died | 11 May 1942(1942-05-11) (aged 55) Tokyo, Japan |

| Occupation |

|

| Genre | |

| Spouse |

|

| Children | 2 |

Sakutarō Hagiwara (萩原 朔太郎, Hagiwara Sakutarō, 1 November 1886 – 11 May 1942) was a Japanese writer of free verse, active in the Taishō and early Shōwa periods of Japan. He liberated Japanese free verse from the grip of traditional rules, and he is considered the "father of modern colloquial poetry in Japan". He published many volumes of essays, literary and cultural criticism, and aphorisms over his long career. His unique style of verse expressed his doubts about existence, and his fears, ennui, and anger through the use of dark images and unambiguous wording. He died from pneumonia aged 55.

Early life

Hagiwara Sakutarō was born in Maebashi, Gunma Prefecture as the son of a prosperous local physician. He was interested in poetry, especially in the tanka format, from an early age, and started to write poetry much against his parents' wishes, drawing on the works of Akiko Yosano for inspiration. From his early teens, he started to contribute poems to literary magazines and had his tanka verse published in the literary journals Bunkō, Shinsei and Myōjō.

His mother bought him his first mandolin in the summer of 1903. After spending a futile five semesters as a freshman at two national universities, he dropped out of school, living for a period in Okayama and Kumamoto. In 1911, when his father was still trying to get him to enter college again, he began studying the mandolin in Tokyo, with the thought of becoming a professional musician. He later established a mandolin orchestra in his hometown Maebashi. His bohemian lifestyle was criticized by his childhood colleagues, and some of his early poems include spiteful remarks about his native Maebashi.

Literary career

In 1913, Hagiwara published five of his verses in Zamboa ("Shaddock"), a magazine edited by Kitahara Hakushū, who became his mentor and friend. He also contributed verse to Maeda Yugure's Shiika ("Poetry") and Chijō Junrei ("Earth Pilgrimage"), another journal created by Hakushū. The following year, he joined Murō Saisei and the Christian minister Yamamura Bochō in creating the Ningyo Shisha ("Merman Poetry Group"), dedicated to the study of music, poetry, and religion. The three writers called their literary magazine, Takujō Funsui ("Tabletop Fountain"), and published the first edition in 1915.

In 1915, Hagiwara attempted suicide because of his continued ill-health and alcoholism. However, in 1916, Hagiwara co-founded with Murō Saisei the literary magazine Kanjō ("Sentiment"). The magazine was centered on the "new style" of modern Japanese poetry that Hagiwara was developing, in contrast to the highly intellectual and more traditionally structured poems in other contemporary literary magazines. In 1917, Hagiwara brought out his first free-verse collection, Tsuki ni Hoeru ("Howling at the Moon"), which had an introduction by Kitahara Hakushū. The work created a sensation in literary circles. Hagiwara rejected the symbolism and use of unusual words, with consequent vagueness of Hakushū and other contemporary poets in favor of precise wording which appealed rhythmically or musically to the ears. The work met with much critical acclaim, especially for its bleak style, conveying an attitude of pessimism and despair based on modern Western psychological concept of existential angst influenced by the philosophy of Nietzsche. There is a preface to Tsuki ni Hoeru ("Howling at the Moon") written by Hagiwara added in the New York Review Books' 2014 Cat Town (a collection of a number of his works).

Hagiwara's second anthology, Aoneko ("Blue Cat") was published in 1923 to even greater acclaim and Tsuki ni Hoeru. The poems in this anthology incorporated concepts from Buddhism with the nihilism of Arthur Schopenhauer. Hagiwara subsequently published a number of other volumes of cultural and literary criticism. He was also a scholar of classical verse and published Shi no Genri ("Principles of Poetry", 1928). His critical study Ren'ai meika shu ("A Collection of Best-Loved Love Poems", 1931), shows that he had a deep appreciation for classical Japanese poetry, and Kyōshu no shijin Yosa Buson ("Yosa Buson—Poet of Nostalgia", 1936) reveals his respect for the haiku poet Buson, who advocated a return to the 17th century rules of Bashō.

Hyōtō ("The Iceland") published in 1934 was Hagiwara's last major anthology of poetry. He abandoned the use of both free verse and colloquial Japanese, and returned to a more traditional structure with a realistic content. The poems are occasionally autobiographical, and exhibit a sense of despair and loneliness. The work received only mixed reviews. For most of his life, Hagiwara relied on his wealthy family for financial support. However, he taught at Meiji University from 1934 until his death in 1942.

Death

After more than six months of struggle with what appeared to be lung cancer but which doctors diagnosed as acute pneumonia, he died in May 1942—not quite six months short of his 56th birthday. His grave is at the temple of Jujun-ji, in his native Maebashi.

Personal life

Hagiwara married Ueda Ineko in 1919; they had two daughters, Yōko (1920–2005), also a writer, and Akirako (b. 1922). Ineko deserted her family for a younger man in June 1929 and ran off to Hokkaidō and Sakutarō formally divorced her in October.

He married again in 1938 to Otani Mitsuko, but after only eighteen months Sakutarō's mother—who had never registered the marriage in the family register (koseki)—drove her away.

See also

References

- "Hagiwara Sakutarō's Fitzgerald," in Prairie Schooner, Vol. 47, No. 2, Summer, 1973, pp. 174-77.

- Hagiwara, Sakutarō (2014). Cat Town. New York, NY: The New York Review of Books. pp. xxvii, 3. ISBN 9781590177754.

- ^ Sakutarō, Hagiwara (1999). Rats' Nests: The Poetry of Hagiwara Sakutarō. Translated by Epp, Robert. Unknown Publisher. pp. 275–282. ISBN 978-92-3-103586-9.

- Sakutarō, Hagiwara (2008). Face at the Bottom of the World and Other Poems. Translated by Wilson, Graeme. Clarendon, Vermont: Tuttle Publishing. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-4629-1267-4.

References and reading

- Hagiwara, Sakutaro. Rats' Nests: The Poetry of Hagiwara Sakutaro. (Trans. Robert Epp). UNESCO (1999). ISBN 92-3-103586-X

- Hagiwara, Sakutaro. Howling at the Moon and Blue (Trans. Hiroaki Sato). Green Integer (2001). ISBN 1-931243-01-8

- Hagiwara, Sakutaro. Principles of Poetry: Shi No Genri. Cornell University (1998). ISBN 1-885445-96-2

- Kurth, Frederick. Howling with Sakutaro: Cries of a Cosmic Waif. Zamazama Press (2004). ISBN 0-9746714-2-8

- Dorsey, James. "From an Ideological Literature to a Literary Ideology: 'Conversion in Wartime Japan'," in Converting Cultures: Religion, Ideology and Transformations of Modernity, ed. by Dennis Washburn and A. Kevin Reinhart (Leiden & Boston: Brill, 2007), pp. 465~483.

External links

- Works by or about Sakutarō Hagiwara at the Internet Archive

- Works by Sakutarō Hagiwara at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- A bibliography in foreign languages

- e-texts of works at Aozora Bunko