A canoe is a lightweight, narrow water vessel, typically pointed at both ends and open on top, propelled by one or more seated or kneeling paddlers facing the direction of travel and using paddles.

In British English, the term canoe can also refer to a kayak, whereas canoes are then called Canadian or open canoes to distinguish them from kayaks. However, for official competition purposes, the American distinction between a kayak and a canoe is almost always adopted. At the Olympics, both conventions are used: under the umbrella terms Canoe Slalom and Canoe Sprint, there are separate events for canoes and kayaks.

Culture

Canoes were developed in cultures all over the world, including some designed for use with sails or outriggers. Until the mid-19th century, the canoe was an important means of transport for exploration and trade, and in some places is still used as such, sometimes with the addition of an outboard motor.

Where the canoe played a key role in history, such as the Northern United States, Canada, and New Zealand, it remains an important theme in popular culture. For instance, the birch bark canoe of the largely birch-based culture of the First Nations of Quebec, Canada, and North America provided these hunting peoples with the mobility essential to this way of life.

Canoes are now widely used for competition — indeed, canoeing has been part of the Olympics since 1936— and pleasure, such as racing, whitewater, touring and camping, freestyle and general recreation.

The intended use of the canoe dictates its hull shape, length, and construction material. Although canoes were historically dugouts or made of bark on a wood frame, construction materials later evolved to canvas on a wood frame, then to aluminum. Most modern canoes are made of molded plastic or composites such as fiberglass, or those incorporating kevlar or graphite.

History

The word canoe came into English from the French word "casnouey" adopted from the Saint-Lawrence Iroquoians language in the 1535 Jacques Cartier Relations translated in 1600 by the English geographer Richard Hackluyt.

Dugouts

Many peoples have made dugout canoes throughout history, carving them out of a single piece of wood: either a whole trunk or a slab of trunk from particularly large trees. Dugout canoes go back to ancient times. The Dufuna canoe, discovered in Nigeria, dates back to 8500–8000 BC. The Pesse canoe, discovered in the Netherlands, dates back to 8200–7600 BC. Excavations in Denmark reveal the use of dugouts and paddles during the Ertebølle period, (c. 5300 – c. 3950 BC).

Canoes played a vital role in the colonisation of the pre-Columbian Caribbean, as they were the only means of reaching the Caribbean Islands from mainland South America. Around 3500 BC, ancient Amerindian groups colonised the first Caribbean Islands using single-hulled canoes. Only a few pre-Columbian Caribbean canoes have been found. Several families of trees could have been used to construct Caribbean canoes, including woods of the mahogany family (Meliaceae) such as the Cuban mahogany (Swietenia mahagoni), that can grow up to 30–35 m tall and the red cedar (Cedrela odorata), that can grow up to 60 m tall, as well as the ceiba genus (Malvacae), such as Ceiba pentandra, that can reach 60–70 m in height. It is likely that these canoes were built in a variety of sizes, ranging from fishing canoes holding just one or a few people to larger ones able to carry as many as a few dozen, and could have been used to reach the Caribbean Islands from the mainland. Reports by historical chroniclers claim to have witnessed a canoe "containing 40 to 50 Caribs when it came out to trade with a visiting English ship".

There is still much dispute regarding the use of sails in Caribbean canoes. Some archaeologists doubt that oceanic transportation would have been possible without the use of sails, as winds and currents would have carried the canoes off course. However, no evidence of a sail or a Caribbean canoe that could have made use of a sail has been found. Furthermore, no historical sources mention Caribbean canoes with sails. One possibility could be that canoes with sails were initially used in the Caribbean but later abandoned before European contact. This, however, seems unlikely, as long-distance trade continued in the Caribbean even after the prehistoric colonisation of the islands. Hence, it is likely that early Caribbean colonists made use of canoes without sails.

Native American groups of the north Pacific coast made dugout canoes in a number of styles for different purposes, from western red cedar (Thuja plicata) or yellow cedar (Chamaecyparis nootkatensis), depending on availability. Different styles were required for ocean-going vessels versus river boats, and for whale-hunting versus seal-hunting versus salmon-fishing. The Quinault of Washington State built shovel-nose canoes with double bows, for river travel that could slide over a logjam without needing to be portaged. The Kootenai of the Canadian province of British Columbia made sturgeon-nosed canoes from pine bark, designed to be stable in windy conditions on Kootenay Lake.

In recent years, First Nations in British Columbia and Washington State have been revitalizing the ocean-going canoe tradition. Beginning in the 1980s, the Heiltsuk and Haida were early leaders in this movement. The Paddle to Expo 86 in Vancouver by the Heiltsuk and the 1989 Paddle to Seattle by multiple Native American tribes on the occasion of Washington State's centennial year were early instances of this. In 1993 a large number of canoes paddled from up and down the coast to Bella Bella in its first canoe festival – Qatuwas. The revitalization continued, and Tribal Journeys began with trips to various communities held in most years.

Australian aboriginal people made canoes from hollowed out tree trunks, as well as from tree bark. The indigenous people of the Amazon commonly used Hymenaea (Fabaceae) trees.

Bark canoes

Australia

Some Australian aboriginal peoples made bark canoes. They could be made only from the bark of certain trees (usually red gum or box gum) and during summer. After cutting the outline of the required size and shape, a digging stick was used to cut through the bark to the hardwood, and the bark was then slowly prised out using numerous smaller sticks. The slab of bark was held in place by branches or handwoven rope, and after separation from the tree, lowered to the ground. Small fires would then be lit on the inside of the bark to cause the bark to dry out and curl upwards, after which the ends could be pulled together and stitched with hemp and plugged with mud. It was then allowed to mature, with frequent applications of grease and ochre. The remaining tree was later dubbed a canoe tree by Europeans.

Because of the porosity of the bark, these bark canoes did not last too long (about two years). They were mainly used for fishing or crossing rivers and lakes to avoid long journeys. They were usually propelled by punting with a long stick. Another type of bark canoe was made out of a type of stringybark gum known as Messmate stringybark (Eucalyptus obliqua), pleating the bark and tying it at each end, with a framework of cross-ties and ribs. This type was known as a pleated or tied bark canoe. Bark strips could also be sewn together to make larger canoes, known as sewn bark canoes.

Americas

Many indigenous peoples of the Americas built bark canoes. They were usually skinned with birch bark over a light wooden frame, but other types could be used if birch was scarce. At a typical length of 4.3 m (14 ft) and weight of 23 kg (50 lb), the canoes were light enough to be portaged, yet could carry a lot of cargo, even in shallow water. Although susceptible to damage from rocks, they are easily repaired. Their performance qualities were soon recognized by early European settler colonials, and canoes played a key role in the exploration of North America, with Samuel de Champlain canoeing as far as the Georgian Bay in 1615.

In 1603 a canoe was brought to Sir Robert Cecil's house in London and rowed on the Thames by Virginian Indians from Tsenacommacah. In 1643 David Pietersz. de Vries recorded a Mohawk canoe in Dutch possession at Rensselaerswyck capable of transporting 225 bushels of maize. René de Bréhant de Galinée, a French missionary who explored the Great Lakes in 1669, declared: "The convenience of these canoes is great in these waters, full of cataracts or waterfalls, and rapids through which it is impossible to take any boat. When you reach them you load canoe and baggage upon your shoulders and go overland until the navigation is good; and then you put your canoe back into the water, and embark again." American painter, author and traveler George Catlin wrote that the bark canoe was "the most beautiful and light model of all the water crafts that ever were invented".

The first explorer to cross the North American continent, Alexander Mackenzie, used canoes extensively, as did David Thompson and the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

In the North American fur trade, the Hudson's Bay Company's voyageurs used three types of canoe:

- The rabaska (French: canot du maître, from the surname of Louise Le Maître, an artisan in the Province of Quebec, though the term would literally mean "master canoe" otherwise) — also referred to as the "Montreal canoe — was designed for the long haul from the St. Lawrence River to western Lake Superior. Its dimensions were length, approximately 11 m (35 ft); beam, 1.2 to 1.8 m (4 to 6 ft); and height, about 76 cm (30 in). It could carry 60 packs weighing 41 kg (90 lb), and 910 kg (2,000 lb) of provisions. With a crew of eight or ten paddling or rowing, they could make three knots over calm waters. Four to six men could portage it, bottom up. Henry Schoolcraft declared it "altogether one of the most eligible modes of conveyance that can be employed upon the lakes". Archibald McDonald of the Hudson's Bay Company wrote: "I never heard of such a canoe being wrecked, or upset, or swamped ... they swam like ducks."

- The canot du nord (French: "canoe of the north"), a craft specially made and adapted for speedy travel, was the workhorse of the fur trade transportation system. About half the size of the rabaska, it could carry about 35 packs weighing 41 kg (90 lb) and was manned by four to eight men. It could in turn be carried by two men and was portaged in the upright position.

- The express canoe (French: "canot léger," light canoe) was about 4.6 m (15 ft) long and was used to carry people, reports, and news.

The birch bark canoe was used in a 6,500-kilometre (4,000 mi) supply route from Montreal to the Pacific Ocean and the Mackenzie River, and continued to be used up to the end of the 19th century.

The indigenous peoples of eastern Canada and the northeast United States made canoes using the bark of the paper birch, which was harvested in early spring by stripping off the bark in one piece, using wooden wedges. Next, the two ends (stem and stern) were sewn together and made watertight with the pitch of balsam fir. The ribs of the canoe, called verons in Canadian French, were made of white cedar, and the hull, ribs, and thwarts were fastened using watap, a binding usually made from the roots of various species of conifers, such as the white spruce, black spruce, or cedar, and caulked with pitch.

Skin canoes

Skin canoes are constructed using animal skins stretched over a framework. Examples include the kayak and umiak.

Modern canoes

In 19th-century North America, the birch-on-frame construction technique evolved into the wood-and-canvas canoes made by fastening an external waterproofed canvas shell to planks and ribs by boat builders such as Old Town Canoe, E. M. White Canoe, Peterborough Canoe Company and at the Chestnut Canoe Company in New Brunswick. Though similar to bark canoes in the use of ribs, and a waterproof covering, the construction method is different, being built by bending ribs over a solid mold. Once removed from the mold, the decks, thwarts and seats are installed, and canvas is stretched tightly over the hull. The canvas is then treated with a combination of varnishes and paints to render it more durable and watertight.

Although canoes were once primarily a means of transport, with industrialization they became popular as recreational or sporting watercraft. John MacGregor popularized canoeing through his books, founding the Royal Canoe Club in London in 1866 and the American Canoe Association in 1880. The Canadian Canoe Association was founded in 1900 and the British Canoe Union in 1936. In Sweden, naval officer Carl Smith was both an enthusiastic promoter of canoeing and a designer of canoes, some experimental, at the end of the 19th century.

Sprint canoe was a demonstration sport at the 1924 Paris Olympics and became an Olympic discipline at the 1936 Berlin Olympics. When the International Canoe Federation was formed in 1946, it became the umbrella organization of all national canoe organizations worldwide.

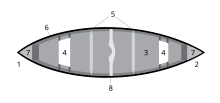

Hull design

Hull design must meet different, often conflicting, requirements for speed, carrying capacity, maneuverability, and stability The canoe's hull speed can be calculated using the principles of ship resistance and propulsion.

- Length: although this is often stated by manufacturers as the overall length of the boat, what counts in performance terms is the length of the waterline, and more specifically its value relative to the displacement (the amount of water displaced by the boat) of the canoe, which is equal to the total weight of the boat and its contents because a floating body displaces its own weight in water. When a canoe is paddled through water, effort is required to push all the displaced water out of the way. Canoes are displacement hulls: the longer the waterline relative to its displacement, the faster it can be paddled. Among general touring canoeists, 5.18 m (17 ft) is a popular length, providing a good compromise between capacity and cruising speed. Too large a canoe will simply mean extra work paddling at cruising speed.

- Width (beam): a wider boat provides more stability at the expense of speed. A canoe cuts through the water like a wedge, and a shorter boat needs a narrower beam to reduce the angle of the wedge cutting through the water. Canoe manufacturers typically provide three beam measurements: the gunwale (the measurement at the top of the hull), the waterline (the measurement at the point where the surface of the water meets the hull when it is empty), and the widest point. Another variation of the waterline beam measurement is called 4" waterline, where the displacement is taken into account. This measurement is done at the waterline level when the maximum load is applied to the canoe. Some canoe races use the 4" waterline beam measurement as the standard for their regulations. In races, the measurement is done by measuring the widest point at 4" (10 cm) from the bottom of the canoe.

- Freeboard: a higher-sided boat stays drier in rough water. The disadvantage of high sides is extra weight and extra windage. Increased windage adversely affects speed and steering control in crosswinds.

- Stability and immersed bottom shape: the hull can be optimized for initial stability (the boat feels steady when it sits flat on the water) or final stability (resistance to rolling and capsizing). A flatter-bottomed hull has higher initial stability, versus a rounder or V-shaped hull in cross-section has high final stability. The fastest flat water non-racing canoes have sharp V-bottoms to cut through the water, but they are difficult to turn and have a deeper draft, which makes them less suitable for shallows. Flat-bottomed canoes are most popular among recreational canoeists. At the cost of speed, they have a shallow draft and more cargo space, and they turn better. The reason a flat bottom canoe has lower final stability is that the hull must wrap a sharper angle between the bottom and the sides, compared to a more round-bottomed boat.

- Keel: an external keel makes a canoe track (hold its course) better and can stiffen a floppy bottom, but it can get stuck on rocks and decrease stability in rapids.

- Profile, the shape of the canoe's sides. Sides that flare out above the waterline deflect water but require the paddler to reach out over the side of the canoe more. Sides that do the reverse, so that the gunwale width is less than the maximum width, the canoe is said to have tumblehome. Tumblehome improves final stability.

- Rocker: viewed from the side of the canoe, rocker is the amount of curve in the hull in relation to the water, much like the curve of a banana. The full length of the hull is in the water, so it tracks well and has good speed. As rocker increases, so does the ease of turning but at the cost of tracking. Some Native American birch-bark canoes were characterized by extreme rocker.

- Hull symmetry: viewed from above, a symmetrical hull has its widest point at the center of the hull and both ends are identical. An asymmetrical hull typically has the widest section aft of centerline, creating a longer bow and improving speed.

Modern materials and construction

Plastic

Folding canoes usually consist of a PVC skin around an aluminum frame.

Inflatable canoes contain no rigid frame members and can be deflated, inflated, folded, and stored in bags and boxes. The more durable types consist of an abrasion-resistant nylon or rubber outer shell with separate PVC air chambers for the two side tubes and the floor.

Royalex — a composite material comprising an outer layer of vinyl and hard acrylonitrile butadiene styrene plastic (ABS) and an inner layer of ABS foam bonded by heat treatment — was another plastic alternative for canoes until 2014, when the raw composite material was discontinued by its only manufacturer. As a canoe material, Royalex is lighter, more resistant to UV damage, and more rigid, and has greater structural memory than non-composite plastics such as polyethylene. Canoes made of Royalex were, however, more expensive than canoes made from aluminum or from traditionally molded or roto-molded polyethylene hulls. Royalex is heavier and less suited for high-performance paddling than fiber-reinforced composites such as fiberglass, kevlar, or graphite.

Fiber reinforced composites

Modern canoes are generally constructed by layering a fiber material inside a "female" mold. Fiberglass is the most common material used in manufacturing canoes. Fiberglass is not expensive, can be molded to any shape, and is easy to repair. Kevlar is popular with paddlers looking for a light, durable boat that will not be taken in whitewater. Fiberglass and Kevlar are strong but lack rigidity. Carbon fiber is used in racing canoes to create a very light, rigid construction usually combined with Kevlar for durability. Boats are built by draping the cloth in a mold, then impregnating it with a liquid resin. Optionally, a vacuum process can be used to remove excess resin to reduce weight.

A gel coat on the outside gives a smoother appearance.

With stitch and glue, plywood panels are stitched together to form a hull shape, and the seams are reinforced with fiber reinforced composites and varnished.

A cedar strip canoe is essentially a composite canoe with a cedar core. Usually fiberglass is used to reinforce the canoe since it is clear and allows a view of the cedar.

Aluminum

Before the invention of fiberglass, aluminum was the standard choice for whitewater canoeing due to its value and strength by weight. This material was once more popular but is being replaced by modern lighter materials. "It is tough, durable, and will take being dragged over the bottom very well", as it has no gel or polymer outer coating which would make it subject to abrasion. The hull does not degrade from long term exposure to sunlight, and "extremes of hot and cold do not affect the material". It can dent, is difficult to repair, is noisy, can get stuck on underwater objects, and requires buoyancy chambers to assist in keeping the canoe afloat in a capsize.

Canoes in culture

In Canada, the canoe has been a theme in history and folklore, and is a symbol of Canadian identity. From 1935 to 1986 the Canadian silver dollar depicted a canoe with the Northern Lights in the background.

The Chasse-galerie is a French-Canadian tale of voyageurs who, after a night of heavy drinking on New Year's Eve at a remote timber camp want to visit their sweethearts some 100 leagues (about 400 km) away. Since they have to be back in time for work the next morning they make a pact with the devil. Their canoe will fly through the air, on condition that they not mention God's name or touch the cross of any church steeple as they fly by in the canoe. One version of this fable ends with the coup de grâce when, still high in the sky, the voyageurs complete the hazardous journey but the canoe overturns, so the devil can honour the pact to deliver the voyageurs and still claim their souls.

In John Steinbeck's novella The Pearl, set in Mexico, the main character's canoe is a means of making a living that has been passed down for generations and represents a link to cultural tradition.

The Māori, indigenous Polynesian people, arrived in New Zealand in several waves of canoe (called waka) voyages. Canoe traditions are important to the identity of Māori. Whakapapa (genealogical links) back to the crew of founding canoes served to establish the origins of tribes, and defined tribal boundaries and relationships.

Types of canoes

Modern canoe types are usually categorized by the intended use. Many modern canoe designs are hybrids (a combination of two or more designs, meant for multiple uses). The purpose of the canoe will also often determine the materials used. Most canoes are designed for either one person (solo) or two people (tandem), but some are designed for more than two people.

Sprint

Main articles: Sprint canoe and Canoe sprintSprint canoe is also known as flatwater racing. The paddler kneels on one knee and uses a single-blade paddle. Since canoes have no rudder, they must be steered by the athlete's paddle using a J-stroke. Canoes may be entirely open or be partly covered. The minimum length of the opening on a C1 is 280 cm (110 in). Boats are long and streamlined with a narrow beam, which makes them very unstable. A C4 can be up to 9 m (30 ft) long and weigh 30 kg (66 lb). International Canoe Federation (ICF) classifications include C1 (solo), C2 (crew of two), and C4 (crew of four). Race distances at the 2012 Olympic Games were 200 and 1000 meters.

Slalom and wildwater

Main articles: Canoe slalom and Wildwater canoeing

In ICF whitewater slalom, paddlers negotiate their way down 300 m (980 ft) of whitewater rapids through a series of up to 25 gates (pairs of hanging poles). The colour of the poles indicates the direction in which the paddlers must pass through; time penalties are assessed for striking poles or missing gates. Categories are C1 (solo) and C2 (tandem), the latter for two men, and C2M (mixed) for one woman and one man. C1 boats must have a minimum weight and width of 10 kg (22 lb) and 0.65 m (2 ft 2 in) and be not more than 3.5 m (11 ft) long. C2s must have a minimum weight and width of 15 kg (33 lb) and 0.75 m (2 ft 6 in), and be not more than 4.1 m (13 ft). Rudders are prohibited. Canoes are decked and propelled by single-bladed paddles, and the competitor must kneel.

In ICF wildwater canoeing, athletes paddle a course of class III to IV whitewater (using the International Scale of River Difficulty), passing over waves, holes and rocks of a natural riverbed in events lasting either 20–30 minutes ("Classic" races) or 2–3 minutes ("Sprint" races). Categories are C1 and C2 for both women and men. C1s must have a minimum weight and width of 12 kg (26 lb) and 0.7 m (2 ft 4 in), and a maximum length of 4.3 m (14 ft). C2s must have a minimum weight and width of 18 kg (40 lb) and 0.8 metres (2 ft 7 in), and a maximum length of 5 metres (16 ft). Rudders are prohibited. The canoes are decked boats which must be propelled by single bladed paddles, with the paddler kneeling inside.

Marathon

Main article: Canoe marathonMarathons are long-distance races which may include portages. Under ICF rules, minimum canoe weight is 10 and 14 kg (22 and 31 lb) for C1 and C2, respectively. Other rules can vary by race. For example, athletes in the Classique Internationale de Canots de la Mauricie race in C2s, with a maximum length of 5.6 m (18 ft 6 in), minimum width of 69 cm (27 in) at 8 cm (3 in) from the bottom of the centre of the craft, minimum height of 38 cm (15 in) at the bow and 25 cm (10 in) at the centre and stern. The Texas Water Safari, at 422 km (262 mi), includes an open class, the only rule being the vessel must be human-powered. Although novel setups have been tried, the fastest so far has been the six-man canoe.

Touring

See also: Canoe campingA "touring" or "tripping" canoe is a boat for traveling on lakes and rivers with capacity for camping gear. Tripping canoes, such as the Chestnut Prospector and Old Town Tripper derivates, are touring canoes for wilderness trips. They are typically made of heavier and tougher materials and designed with the ability to carry large amounts of gear while being maneuverable enough for rivers with some whitewater. Prospector is now a generic name for derivates of the Chestnut model, a popular type of wilderness tripping canoe. The Prospector is marked by a shallow arch hull with a relatively large amount of rocker, giving optimal balance for wilderness tripping over lakes and rivers with some rapids.

A touring canoe is sometimes covered with a greatly extended deck, forming a "cockpit" for the paddlers. A cockpit has the advantage that the gunwales can be made lower and narrower so the paddler can reach the water more easily.

Freestyle

A freestyle canoe is specialized for whitewater play and tricks. Most are identical to short, flat-bottomed kayak playboats except for their internal outfitting. The paddler kneels and uses a single-blade canoe paddle. Playboating is a discipline of whitewater canoeing where the paddler performs various technical moves in one place (a playspot), as opposed to downriver where the objective is to travel the length of a section of river (although whitewater canoeists will often stop and play en route). Specialized canoes known as playboats can be used.

Square-stern canoe

A square-stern canoe is an asymmetrical canoe with a squared-off stern for the mounting of an outboard motor, and is meant for lake travel or fishing. Since mounting a rudder on the square stern is very easy, such canoes often are adapted for sailing.

Canoe launches

A canoe launch is a place for launching canoes, similar to a boat launch which is often for launching larger watercraft. Canoe launches are frequently on river banks or beaches. Canoe launches may be designated on maps of places such as parks or nature reserves.

Photo gallery

-

Frances Anne Hopkins (1838–1919): Canoe Manned by Voyageurs Passing a Waterfall

Frances Anne Hopkins (1838–1919): Canoe Manned by Voyageurs Passing a Waterfall

-

Paul Kane (1810–1871): Spearing Salmon By Torchlight, oil painting

Paul Kane (1810–1871): Spearing Salmon By Torchlight, oil painting

-

Ojibwe women in canoe on Leech Lake, Bromley, 1896

Ojibwe women in canoe on Leech Lake, Bromley, 1896

-

Canoe in Kerala, India, 2008

Canoe in Kerala, India, 2008

-

Canoe in Vietnam in the Mekong Delta, 2009

-

Packed canoes at the beach

Packed canoes at the beach

-

Canoe at sea

Canoe at sea

-

Square back canoe with a small outboard motor

See also

- Umiak

- Outrigger

- Waka (canoe)

- Adirondack guideboat – resembles a canoe

- Canoe paddle strokes

- Canadian Canoe Museum

- Kennebec Boat and Canoe Company

- E.H. Gerrish Canoe Company

- Thompson Brothers Boat Manufacturing Company

- Carleton Canoe Company

References

- "Amerindian Museum of Mashteuiat". 2024. Retrieved 21 April 2024.

Our team is composed of members from the Pekuakamiulnuatsh First Nation

- "Bark Canoe Construction". Canadian Museum of History. Government of Canada. Retrieved 21 April 2024.

In Canada, the most popular bark for canoe construction has come from the paper birch

- Canoe Sprint at Paddle UK (formerly British Canoeing). Retrieved 6 August 2024.

- Frère Marie-Victorin (1935). "The birch bark canoe, an exceptional reign". florelaurentienne.com (in French). pp. 150 of 925. Retrieved 21 April 2024.

Betula papyrifera Marshall. — Bouleau à papier. — Bouleau blanc, Bouleau à canot. — (Canoë birch).

- "Dugout Canoe". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 15 November 2012. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- See Michel Bideaux (ed.), Jacques Cartier, Relations, Montréal, Presse de l'Université de Montréal, 1986, p. 181

- ^ Pojar and MacKinnon (1994). Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Vancouver, British Columbia: Lone Pine Publishing. ISBN 1-55105-040-4.

- Olympic Peninsula Intertribal Cultural Advisory Committee (2002). Native Peoples of the Olympic Peninsula. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3552-2.

- Gumnior, Maren; Thiemeyer, Heinrich (2003). "Holocene fluvial dynamics in the NE Nigerian Savanna". Quaternary International. 111: 54. doi:10.1016/s1040-6182(03)00014-4. S2CID 128422267.

- "Oudste bootje ter wereld kon werkelijk varen". Leeuwarder Courant (in Dutch). ANP. 12 April 2001. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- "Dugouts and paddles". Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- Boomert, Arie (2019). The first settlers: Lithic through Archaic times in the coastal zone and on the offshore islands of northeast South America, in: C. Hofman and A. Antczak (eds.), Early settlers of the Insular Caribbean : dearchaizing the Archaic. Hofman, Corinne L., 1959–, Antczak, Andrzej T. Leiden. p. 128. ISBN 978-90-8890-780-7. OCLC 1096240376.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Napolitano, Matthew F.; DiNapoli, Robert J.; Stone, Jessica H.; Levin, Maureece J.; Jew, Nicholas P.; Lane, Brian G.; O’Connor, John T.; Fitzpatrick, Scott M. (2019). "Reevaluating human colonization of the Caribbean using chronometric hygiene and Bayesian modeling". Science Advances. 5 (12): eaar7806. Bibcode:2019SciA....5R7806N. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aar7806. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 6957329. PMID 31976370.

- Fitzpatrick, Scott M. (2013). "Seafaring Capabilities in the Pre-Columbian Caribbean". Journal of Maritime Archaeology. 8 (1): 101–138. Bibcode:2013JMarA...8..101F. doi:10.1007/s11457-013-9110-8. ISSN 1557-2285. S2CID 161904559.

- Fitzpatrick, Scott M. (2013). "Seafaring Capabilities in the Pre-Columbian Caribbean". Journal of Maritime Archaeology. 8 (1): 101–138. Bibcode:2013JMarA...8..101F. doi:10.1007/s11457-013-9110-8. ISSN 1557-2285. S2CID 161904559.

- McKusick, Marshall Bassford (1970). Aboriginal canoes in the West Indies. p. 7. OCLC 79431894.

- Callaghan, Richard T. (2001). "Ceramic Age Seafaring and Interaction Potential in the Antilles: A Computer Simulation". Current Anthropology. 42 (2): 308–313. doi:10.1086/320012. ISSN 0011-3204. S2CID 55762164.

- Keegan, William; Hofman, Corinne (2017). The Caribbean before Columbus. Hofman, Corinne L., 1959–. New York, NY. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-19-060524-7. OCLC 949669477.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Nisbet, Jack (1994). Sources of the River. Seattle, Washington: Sasquatch Books. ISBN 1-57061-522-5.

- Neel, David The Great Canoes: Reviving a Northwest Coast Tradition. Douglas & McIntyre. 1995. ISBN 1-55054-185-4

- ^ "Carved wooden canoe, National Museum of Australia". Nma.gov.au. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ^ "Aboriginal canoe trees around found along the Murray River". Discover Murray River. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- "Did you know?: Canoe trees". SA Memory. 26 November 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Couper Black, E. (December 1947). "Canoes and Canoe Trees of Australia". The Australian Journal of Anthropology. 3 (12). Australian Anthropological Society: 351–361. doi:10.1111/j.1835-9310.1947.tb00139.x.

This paper was read before Section F of the Biennial Meeting of the Australian and New Zealand Association for the Advancement of Science, held at Adelaide in August, 1946.

- "Bark canoes". Canadian Museum of Civilization. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- "Our Canoeing Heritage". The Canadian Canoe Museum. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- Alden T. Vaughan, Transatlantic Encounters: American Indians in Britain, 1500-1776 (Cambridge, 2006), p. 43.

- Hodge, Frederick Webb (1917). Proceedings of the Nineteenth International Congress of Americanists: Held at Washington, December 27–31, 1915. International Congress of Americanists. p. 280.

- Jameson, John (May 2009). Narratives of New Netherland: 1609–1664. Applewood Books. p. 226. ISBN 978-1-4290-1896-8.

- Kellogg, Louise Phelps (1917). Early Narratives of the Northwest. 1634–1699. New York. pp. 172–173.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Catlin, George (1989). Letters and Notes on the Manners. Customs, and Conditions of the North American Indians (reprint ed.). New York. p. 415.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "The Canoe". The Hudson's Bay Company. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- "Rabaska". Definitions. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- "Hudson's Bay Company". HBC Heritage. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ^ "Portage Trails in Minnesota, 1630s–1870s". United States Department of the Interior National Park Service. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- "Canoeing". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- Margry, Pierre (1876–1886). Decouvertes et etablissements des francais dans I'ouest et dans le sud de I'Amerique Septentrionale (1614–1754). 6 vols. Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Tom Vennum, Charles Weber, Earl Nyholm (Director) (1999). Earl's Canoe: A Traditional Ojibwe Craft. Smithsonian Center for Folklife Programs and Cultural Studies. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- "A Venerable Chestnut". Canada Science and Technology Museum. Archived from the original on 2 October 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- "The Wood and Canvas Canoe". Wooden Canoe Heritage Association. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- Jonas, Hedberg (2024). "Riddare av paddeln: kanotismens första decennier i Sverige". Digitalt Museum. Maritime Museum (Stockholm). Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- "Canoe / kayak sprint equipment and history". olympic.org. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- Canoeing : outdoor adventures. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. 2008. ISBN 978-0-7360-6715-7.

- ^ Davidson, James & John Rugge (1985). The Complete Wilderness Paddler. Vintage. pp. 38–39. ISBN 0-394-71153-X.

- "Canoe Design". Canoe.com. 21 January 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- Competition Rules Canoe and Kayak Specifications Sanctioned Race Sponsor Requirements (PDF). United States Canoe Association. 13 January 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- 38th Annual Run of the Charles (PDF). Charles River Watershed Association. 2020. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ "How to Choose a Canoe: A Primer on Modern Canoe Design". GORP. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ^ "The Hull Truth". Mad River Canoe. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- James Weir, Discover Canoeing: A Complete Introduction to Open Canoeing, p.17, Pesda Press, 2010, ISBN 1906095124

- ^ "Royalex (RX)". Archived from the original on 25 February 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- "Canoe Materials". Frontenac Outfittesr. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- "Buying The Right Canoe". Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- "The Canoe". McGill University. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- "The Pearl: Themes, Motifs, & Symbols". Spark Notes. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- "Story: Canoe traditions". The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- "Canoe sprint". International Canoe Federation. Archived from the original on 8 October 2010. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- "Canoe Sprint Overview". International Canoe Federation. Archived from the original on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- "About Canoe Slalom". International Canoe Federation. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- "Rules for Canoe Slalom" (PDF). International Canoe Federation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- "Wildwater Competition rules 2011" (PDF). International Canoe Federation. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- "La Classique Internationale de Canots de la Mauricie: Rules and Regulations". Archived from the original on 19 January 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- "Texas Water Safari: History". Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- Parks Canada Agency, Government of Canada (8 January 2018). "Canoe launch – Pukaskwa National Park". www.pc.gc.ca. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- Gonzalez, Michael (20 August 2019). "New kayak, canoe launch on Little Calumet River adds to recreation opportunities". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- "Friends of Shiawassee say canoe launch is now open". The Argus-Press. 30 August 2019. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- "Paddle – Royal Botanical Gardens". Royal Botanical Gardens. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- Schlote, Warren (19 June 2019). "Wiikwemkoong outdoor education class builds, launches 30 ft. canoe". Manitoulin Expositor. Archived from the original on 3 September 2019. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

External links

Media related to Canoes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Canoes at Wikimedia Commons

| Canoeing and kayaking | |

|---|---|

| Main disciplines | |

| Olympics | |

| Other disciplines | |

| ICF championships |

|

| Recreation | |

| Modern boats | |

| Traditional boats | |

| Techniques | |

| Equipment | |

| Venues | |

| Competitions | |

| Festivals | |

| Governing bodies | |

| Other organisations | |

| Media | |

| Human-powered transport | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Water |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Amphibious | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Air | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Non-vehicular transport |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Related topics | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Water sports and activities | |

|---|---|

| Activities in water | |

| Activities on water | |

| Team sports | |

| Competitions | |