Michael at peak intensity while making landfall on the Florida Panhandle on October 10 Michael at peak intensity while making landfall on the Florida Panhandle on October 10 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | October 7, 2018 |

| Extratropical | October 11, 2018 |

| Dissipated | October 16, 2018 |

| Category 5 major hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 160 mph (260 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 919 mbar (hPa); 27.14 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 74 (31 direct, 43 indirect) |

| Damage | $25.5 billion (2018 USD) |

| Areas affected | Central America, Yucatán Peninsula, Cayman Islands, Cuba, Southeastern United States (especially the Florida Panhandle and Georgia), Eastern United States, Eastern Canada, Iberian Peninsula |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 2018 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Hurricane Michael was a powerful and destructive tropical cyclone that became the first Category 5 hurricane to make landfall in the contiguous United States since Andrew in 1992. It was the third-most intense Atlantic hurricane to make landfall in the contiguous United States in terms of pressure, behind the 1935 Labor Day hurricane and Hurricane Camille in 1969. Michael was the first Category 5 hurricane on record to impact the Florida Panhandle, the fourth-strongest landfalling hurricane in the contiguous United States in terms of wind speed, and the most intense hurricane on record to strike the United States in the month of October.

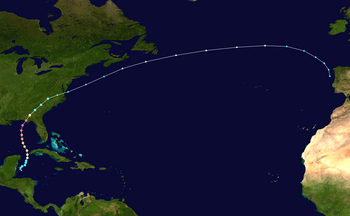

The thirteenth named storm, seventh hurricane, and second major hurricane of the 2018 Atlantic hurricane season, Michael originated from a broad low-pressure area that formed in the southwestern Caribbean Sea on October 1. The disturbance became a tropical depression on October 7, after nearly a week of slow development. By the next day, Michael had intensified into a hurricane near the Guanahacabibes Peninsula, as it moved northward. The hurricane rapidly intensified in the Gulf of Mexico, reaching major hurricane status on October 9. As it approached the Florida Panhandle, Michael reached Category 5 status with peak winds of 160 mph (260 km/h) just before making landfall near Mexico Beach, Florida, on October 10, becoming the first to do so in the region as a Category 5 hurricane, and as the strongest storm of the season. As it moved inland, the storm weakened and began to take a northeastward trajectory toward the Chesapeake Bay, downgrading to a tropical storm over Georgia, and transitioning into an extratropical cyclone over southern Virginia late on October 11. Michael subsequently strengthened into a powerful extratropical cyclone and eventually impacted the Iberian Peninsula before dissipating on October 16.

At least 74 deaths were attributed to the storm, including 59 in the United States and 15 in Central America. Michael caused an estimated $25.1 billion (2018 USD) in damages, including $100 million in economic losses in Central America, damage to U.S. fighter jets with a replacement cost of approximately $6 billion at Tyndall Air Force Base, and at least $6.23 billion in insurance claims in the U.S. Losses to agriculture alone exceeded $3.87 billion. As a tropical disturbance, the system caused extensive flooding in Central America in concert with a second disturbance over the eastern Pacific Ocean. In Cuba, the hurricane's winds left over 200,000 people without power as the storm passed to the island's west. Along the Florida panhandle, the cities of Mexico Beach and Panama City suffered the worst of Michael, incurring catastrophic damage from the extreme winds and storm surge. Numerous homes were flattened and trees felled over a wide swath of the panhandle. A maximum wind gust of 139 mph (224 km/h) was measured at Tyndall Air Force Base before the sensors failed. As Michael tracked across the Southeastern United States, strong winds caused extensive power outages across the region.

Meteorological history

Map key Saffir–Simpson scale Tropical depression (≤38 mph, ≤62 km/h)

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown Storm type

Tropical cyclone

Tropical cyclone  Subtropical cyclone

Subtropical cyclone  Extratropical cyclone, remnant low, tropical disturbance, or monsoon depression

Extratropical cyclone, remnant low, tropical disturbance, or monsoon depression A large area of disturbed weather spawned over the mid-to-western Caribbean Sea around October 1–2, 2018, and absorbed the remnants of Tropical Storm Kirk. The National Hurricane Center (NHC) anticipated on October 2 that strong upper-level winds would prevent any significant development of the system for at least a couple of days. On the same day, a tropical wave – an elongated trough of low air pressure – tracked into the area. This possibly led to an increase in thunderstorm activity which in turn gave rise to a surface low southwest of Jamaica on October 3. Although the low was initially predicted to travel northward, it instead tracked west-southwestward and moved ashore in northeastern Honduras on October 4. The low became incorporated into a broad cyclonic gyre which was located over Central America by October 5. A center which was located over the eastern Pacific moved across Central America on October 6 and integrated into the gyre. The gyre's center reformed over the northwestern Caribbean Sea on the same day.

Due to the imminent threat that the system posed to land, the NHC began issuing advisories on it as Potential Tropical Cyclone Fourteen around 21:00 UTC on October 6. Meanwhile, an upper-level trough located over the Gulf of Mexico was imparting vertical wind shear over the system. Despite this, the system's convection or thunderstorm activity, as well as its circulation, were improving in organization on both satellite imagery and in surface observations. The disturbance tracked generally northward within the southerly flow between a subtropical ridge which was located over the western Atlantic Ocean and a mid-latitude trough that was traveling eastward across the United States. A tropical depression spawned around 06:00 UTC on October 7, approximately 150 mi (240 km) south of Cozumel, Mexico. Around that time, Belizean radar showed that convection was forming just northeast of the depression's low-level center. The nascent depression was located in an environment of strong wind shear and warm 82–86 °F (28–30 °C) sea surface temperatures. Around 12:00 UTC, the depression intensified into a tropical storm, receiving the name Michael. During the next six hours, the center of the storm relocated to the northeast as a result of flaring convection in that region. The system proceeded to travel slightly east of north as it rounded the western periphery of a mid-level ridge that was located over the western Atlantic.

After becoming a tropical storm, Michael began a period of rapid intensification. Initially, the NHC had predicted Michael to reach a peak intensity of 70 mph (110 km/h) as wind shear was expected to persist for at least two days, however, Michael became significantly stronger by the time it made landfall, reaching Category 5 status on the Saffir-Simpson scale. Two factors may have helped to facilitate the cyclone's intensification; the first was diffluence or streamline divergence – the elongating of a fluid body normal to the flow – originating from an upper-level trough that was counteracting the wind shear. The second factor was that Michael's outflow entered another upper-level trough that was located east of the storm. A WC-130 aircraft from the United States Air Force Reserve 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron discovered that Michael had been quickly intensifying as it surveyed the tropical cyclone in the afternoon and evening of October 7, measuring peak stepped frequency microwave radiometer (SFMR) winds between 45 and 60 mph (72 and 97 km/h) during its mission. Although Michael had strengthened to 60 mph (97 km/h) by 00:00 UTC on October 8, most of the storm's convection remained displaced to its eastern side as a result of the wind shear. Microwave imagery, however, showed that the core of Michael had improved, with one banding feature curving around most of the storm.

The tropical storm continued to organize, with convection and outflow increasing in the western half of the system. Michael became a Category 1 hurricane around 12:00 UTC on October 8. An eye was beginning to appear in satellite imagery around the same time. Around 18:30 UTC on October 8, Michael reached its initial peak intensity as a Category 2 hurricane with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h) as it tracked just west of Cabo del San Antonio, Cuba. But overnight, Michael's eyewall began to degrade due to a cold water eddy, dry air incursion, and wind shear, signaling that the rapid intensification had ceased. Shortly after, the hurricane's banding features began to improve as the system was located over the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico. By 12:00 UTC on October 9, Michael had begun to rapidly intensify once more; its eye had become better defined and outflow improved as the westerly shear decreased. Meanwhile, the hurricane was tracking north-northwest due to a mid-level ridge. The tropical cyclone strengthened into a Category 3 major hurricane by 18:00 UTC as cold convection developed over the eastern and southeastern regions of the storm and wrapped around its eyewall. Cloud temperatures decreased to −103 °F (−75 °C) in the central dense overcast and were as low as −126 °F (−88 °C) in the eyewall.

Michael resumed a northward trek early on October 10 as it traveled between the ridge and a mid-latitude shortwave trough. Outflow generated by the trough may have hastened Michael's rapid intensification until landfall. The outer rainbands of Michael began to move ashore around 10:00 UTC, and the cyclone's eye continued to warm as it approached the Florida Panhandle, however, radar imagery showed a secondary eyewall was beginning to form. The hurricane's direction shifted to the northeast under the influence of the westerlies. Michael reached its peak intensity as a Category 5 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 160 mph (260 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 919 mbar (27.14 inHg) around 17:30 UTC on October 10, as it made landfall near Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida. Operationally, the NHC had reported Michael's landfall intensity as 155 mph (249 km/h) based on flight-level winds of 175 mph (282 km/h) and SFMR readings between 152 and 159 mph (245 and 256 km/h). However, some data from the SFMR instrument was missing and had to be reconstructed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Aircraft Operation Center. This data yielded a peak SFMR value of 175 mph (282 km/h) for the time that the reconnaissance aircraft surveyed the southern eyewall. Additionally, doppler weather radar from Eglin Air Force Base estimated peak winds of 178 mph (286 km/h) at 17:22 UTC, around the same location as the aircraft. The radar displayed that stronger winds existed northeast of the aircraft, outside its field of observation.

After moving ashore, Michael quickly became less intense; by 21:30 UTC on October 10, just four hours after landfall, Michael had weakened below Category 3 status before moving into southwestern Georgia. Around that time, the hurricane was continuing to track northeast under the influence of the westerlies. Doppler radar displayed that Michael had continued to degrade, with the storm weakening into a high-end Category 1 hurricane by 00:00 UTC. At that time, the peak winds were confined to a region of convection near Michael's low-level center. Six hours later, Michael fell to tropical storm intensity, with only a small zone of storm-force winds existing near its center. Most of the peak winds were displaced to the southeast, over the Atlantic Ocean. The storm entered South Carolina around 15:00 UTC on October 11. By that time, all of the gale-force winds associated with Michael were occurring over the Atlantic Ocean and along the shoreline.

As Michael entered North Carolina late on October 11, it began to transition into an extratropical cyclone. Cold, dry air entrained into the storm's circulation. Winds increased northwest of the storm's elongating center, over the states of North Carolina and Virginia. Michael became fully extratropical by 00:00 UTC on October 12 as it traveled east-northeastward, just north of Raleigh, North Carolina. Around that time, another low-level center with a lower pressure had formed farther north, near Chesapeake Bay, as baroclinic processes began to restrengthen the former hurricane. The extratropical cyclone emerged into the Atlantic around 06:00 UTC after passing near Norfolk, Virginia. Michael obtained hurricane-force winds on October 13 while in the Atlantic waters south of Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. It quickly traveled to the northeastern Atlantic by October 14. The cyclone turned sharply southeastward and later southward around the northeastern edge of the ridge, weakening slightly, as it approached the Iberian Peninsula. Michael's remnant low dissipated by 00:00 UTC on October 16, while it was located just west of northern Portugal. On the same day, Michael's extratropical remnant absorbed the remnants of Hurricane Leslie, which were situated to the east of Michael, following a brief Fujiwhara interaction; Michael's remnants subsequently dissipated shortly afterward.

Preparations

Cuba

In the province of Pinar del Río, 300 people were evacuated to the homes of neighbors or relatives. In the province of Artemisa, particularly in the areas of Playa de Majana and the towns of Cajio and Guanimar, which are prone to coastal flooding, evacuations were carried out, but the number of evacuees were unknown. A national response plan was carried out and alert as well as evacuation phases were being fulfilled as well. In western Cuba, a hurricane warning was issued 10 hours before the center passed over Cabo del San Antonio. Tropical storm warnings were also issued for western Cuba, but it was noted that there were a lack of watches issued by the NHC which was blamed on poor intensity forecasts which depicted Michael becoming a hurricane after passing over the island.

United States

Roughly 375,000 people across 22 Florida counties in the Florida Panhandle and north-central Florida were under orders or recommendations to evacuate. Mandatory evacuation orders were issued for parts of several Florida counties, including communities such as Panama City Beach and covering over 180,000 residents. A survey of 1,523 people in Alabama, Georgia, and Florida later found that 61 percent of survey respondents did not evacuate, and that 80 percent of respondents underestimated the hurricane or the potential scope of its effects. The Florida National Guard had 500 of its members activated, with another 5,000 members placed on standby. Non-mission essential personnel and aircraft were evacuated from Tyndall Air Force Base; aircraft were also moved out of Hurlburt Field and Eglin Air Force Base. Schools closed their campuses during the hurricane's passage, including Florida A&M University, Florida State University, and Tallahassee Community College. The Apalachicola National Forest and Congaree National Park closed for safety reasons. Energy companies paused offshore oil production equivalent to about 324,190 barrels per day, accounting for around a fifth of oil production in the Gulf of Mexico. Offshore natural gas extraction was also halted, accounting for about 284 million ft (8 million m) of natural gas per day. Staff on thirteen offshore platforms were evacuated.

Georgia Governor Nathan Deal declared a state of emergency for 92 counties in the southern and central portions of the state on October 9. Several colleges and universities in south Georgia were to close for a few days. Atlanta Motor Speedway opened their campgrounds free of charge to evacuees of Hurricane Michael.

375,000 people were asked to evacuate as the storm strengthened, with sustained winds of 150 mph (240 km/h) and storm surge up to 14 ft (4.3 m) expected. Emergency Preparedness organizations like Direct Relief provided emergency medical packs throughout ten health facilities that were in Michael's path.

Impact

| Country | Deaths |

|---|---|

| United States | 59 |

| Honduras | 8 |

| Nicaragua | 4 |

| El Salvador | 3 |

| Total | 74 |

Central America

The combined effects of the precursor low to Michael and a disturbance over the Pacific Ocean caused significant flooding across Central America. At least 15 fatalities occurred: eight in Honduras, 4 in Nicaragua, and 3 in El Salvador. In Honduras, torrential rain caused at least seven rivers to overtop their banks; nine communities became isolated. Heavy rains from Hurricane Michael forced hundreds of people from their homes in Honduras over the weekend as the intensifying storm continued its push towards the Gulf Coast. On October 7, the Permanent Commission of Contingencies said more than 260 homes were damaged in the southern part of the country. Some 6,000 people were impacted by flooding and landslides, according to the Associated Press. During a press conference earlier that day, Honduras president Juan Orlando Hernández said at least 18 people were rescued during the storm. The storm forced the closure of schools nationwide on October 8. More than 1,000 homes sustained damage, of which 9 were destroyed, affecting more than 15,000 people. Nationwide, 78 shelters housed displaced persons and relief agencies procured 36 tonnes of aid. Nearly 2,000 homes in Nicaragua suffered damage, and 1,115 people were evacuated. A total of 253 homes were damaged in El Salvador. Damage across the region exceeded $100 million. Images circulated over social media depicting families wading through thigh-high water, rivers rushing onto streets and roads to communities cut off by mudslides. Local media in Honduras recorded several deaths. Homes in Honduras that were built close to waterways or wedged precariously on hillslides were vulnerable to being washed away by rain, and as a result, a lot of them were.

Cuba

About 70% of the offshore Isla de la Juventud lost power. On the southern coast of the island, La Coloma was inundated by storm surge, sinking ships and flooding homes. High winds left more than 200,000 people without power in the province of Pinar del Río, accounting for 90% of the province. Officials sent 500 power workers to the area to restore electricity. Widespread damage was inflicted on tobacco crops, leading to the complete loss of 18,000 seedbeds of tobacco in the province; the hurricane struck Cuba coincident with the start of the sowing season for tobacco on October 10. More than 600 hectares (1,500 acres) of rice were also damaged by Michael's rainfall. At least 694 homes in Cuba were damaged by the hurricane, including 300 in Sandino.

United States

| Strongest U.S. landfalling tropical cyclones† | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name‡ | Season | Wind speed | ||

| mph | km/h | ||||

| 1 | "Labor Day" | 1935 | 185 | 295 | |

| 2 | Karen | 1962 | 175 | 280 | |

| Camille | 1969 | ||||

| Yutu | 2018 | ||||

| 5 | Andrew | 1992 | 165 | 270 | |

| 6 | "Okeechobee" | 1928 | 160 | 260 | |

| Michael | 2018 | ||||

| 8 | Maria | 2017 | 155 | 250 | |

| 9 | "Last Island" | 1856 | 150 | 240 | |

| "Indianola" | 1886 | ||||

| "Florida Keys" | 1919 | ||||

| "Freeport" | 1932 | ||||

| Charley | 2004 | ||||

| Laura | 2020 | ||||

| Ida | 2021 | ||||

| Ian | 2022 | ||||

| Source: Hurricane Research Division | |||||

| †Strength refers to maximum sustained wind speed upon striking land. | |||||

| ‡Systems prior to 1950 were not officially named. | |||||

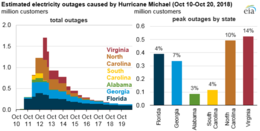

According to the Edison Electric Institute, at one point 1.2 million electricity customers were without power in several east coast and southern states. Estimated damage from Michael throughout the United States reached $25 billion.

Florida

The National Centers for Environmental Information estimated that Michael caused $18.4 billion in damage in Florida, primarily incurred by property and infrastructure. The most severe impacts occurred along the Florida coast between Panama City Beach and Cape San Blas, with catastrophic impacts in the areas around Mexico Beach and Tyndall Air Force Base. Impacts were evident on all types of buildings, though structures built before 2002 fared substantially worse. Mobile homes in the regions affected by Michael were older and smaller than in other parts of the state and experienced significant to catastrophic impacts in the hardest-hit areas. Damage to over 2.8 million acres (1.1 million hectares) of forested land caused an estimated $1.29 billion in damage to the timber industry; 12% of damaged forest area was classified as "catastrophic" by the Florida Forest Service. Around 28 percent of global longleaf pine ecosystems were affected by the hurricane in Florida; near the storm's center, tree mortality was as high as 87.8 percent. Damage to various agricultural sectors, chiefly cotton, cattle, and peanuts, amounted to $180 million. Only 5-10% of the cotton crop had been harvested at the time of Michael's landfall, resulting in total losses of cotton where Category 3–4 hurricane winds were felt. Losses to the cattle industry stemmed largely from damage to farm infrastructure; an estimated 1,507 cattle ranches and 106,438 head of cattle were within the hurricane-force wind envelope of Michael. Seven deaths were directly caused by the hurricane's forces, including five drownings due to storm surge and two deaths due to fallen trees; the drownings all involved elderly individuals. There were another 43 deaths indirectly caused by Michael, including those that occurred during the storm's aftermath and those from health complications exacerbated by the hurricane, resulting in 50 deaths total in Florida attributed to Michael.

Based on post-storm analyses conducted by the National Hurricane Center synthesizing data from several data sources, Michael made landfall as a Category 5 hurricane at Mexico Beach, near Tyndall Air Force Base at 12:30 pm. CDT (17:30 UTC) on October 10. Its maximum sustained winds were estimated to be 160 mph (260 km/h) upon moving ashore, making it the most intense hurricane landfall on record for the Florida Panhandle. Michael was the only tropical cyclone known to have struck the Florida Panhandle at stronger than Category 3 intensity, and the first Category 5 hurricane to make landfall anywhere along the U.S. coast since Hurricane Andrew in 1992. Three surface weather stations collected data from Michael's eyewall as it moved onshore; however, they either malfunctioned before the arrival of the storm's strongest winds or were positioned outside the radius of maximum wind, providing incomplete measurements and resulting in maximum values lower than expected from radar and aircraft reconnaissance data. The fastest 1-minute average wind measured by a surface-based anemometer was 86 mph (138 km/h) at a weather station within Tyndall Air Force Base; the same station recorded a peak wind gust of 139 mph (224 km/h). Another station on the base grounds, affixed to a tower, registered a 129 mph (208 km/h) gust before the tower toppled. Michael continued to produce hurricane-force wind gusts near its center as it moved across the Florida Panhandle into Georgia; its center traversed the Panhandle in four hours. A 102 mph (164 km/h) gust was documented in Marianna, Florida.

The combination of Michael's storm surge and the astronomical tide submerged normally dry areas under 9–14 ft (2.7–4.3 m) of water along the coast between Tyndall Air Force Base and Port St. Joe, Florida. Waves atop the elevated water levels caused additional damage and inundation. Maximum inundation depths were further enhanced by St. Joseph Peninsula, which kept the storm surge elevated by preventing surge water from receding into the open gulf. Storm surge inundation decreased farther west and east of the hurricane's point of landfall; along the Big Bend inundation heights were 6–9 ft (1.8–2.7 m), and towards Tampa Bay they diminished to 2–4 ft (0.61–1.22 m). Between Pensacola and Panama City, maximum storm surge inundation was also 2–4 ft (0.61–1.22 m). The highest rainfall total from Michael in Florida occurred at Lynn Haven, where 11.62 in (295 mm) of rain was measured. Higher rainfall totals were concentrated in eastern Washington County and western Jackson County; locations in the path of Michael's eyewall received 6–10 in (150–250 mm) of rain while those in the hurricane's outer rainbands generally recorded 1–3 in (25–76 mm) of rain. The impacts of inland flooding were lessened by Michael's quick path through the Florida Panhandle, occurring in localized areas. Power outages affected nearly 400,000 electricity customers in Florida at their greatest extent, representing about 4% of the state. Five counties experienced a complete loss of electrical power.

Bay County

Catastrophic and widespread damage occurred in Bay County, where Michael made landfall; 45,000 structures were damaged and 1,500 were destroyed throughout the county. Two hospitals—Bay Medical Sacred Heart and Gulf Coast Regional Medical Center—suffered significant damage. Approximately 19.5 mi (31.4 km) of the 41.2 mi (66.3 km) Bay County coastline, which includes Panama City Beach and Mexico Beach, sustained critical beach erosion. Sensor data and high water marks surveyed by the United States Geological Survey indicated that water inundation at Mexico Beach reached a depth of 14 ft (4.3 m) above ground level, classifying Michael's surge at Mexico Beach as a 1-in-280 year event. Mexico Beach was the community most heavily impacted by Hurricane Michael and experienced both the hurricane's maximum winds and surge; Federal Emergency Management Agency Administrator Brock Long described the city as "probably ground zero." Of the 1,692 buildings in the city, 1,584 were damaged, and 809 among those were destroyed. Waves augmented by the elevated waters damaged the second-stories of buildings and carried boats inland. Along the immediate coast, the combination of surge and extreme winds whittled buildings down to piles of debris and left their concrete slab foundations exposed. Those that remained intact were crumpled and contorted or were eventually razed by unattended fires that began during the storm. Beach houses were severed from their pilings and the city's public pier succumbed to the intense surf. Some staircases remained standing without their associated houses. Debris from various razed structures accumulated on US 98, whose pavement was partially washed out by Michael. The road remained closed for nearly a year before repairs completed. Boats were broken in half and 33-short-ton (30 t) rail cars were toppled. It was estimated that as many as 285 residents of the small town may have stayed despite mandatory evacuations. Three drownings occurred in or near Mexico Beach.

Significant structural damage was wrought to Tyndall Air Force Base. Due to the base's location on the left side of Michael's eye, damage there was primarily due to the force of the winds rather than storm surge. Every building was damaged and many were considered a complete loss by the base administration; the base's marina was also destroyed. Of the damaged buildings, 484 were considered destroyed or beyond repair; $648 million was later allocated in repairs for the remaining structures. Vehicles were tossed through parking lots and destroyed, and an McDonnell Douglas F-15 Eagle and General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon used for display were flipped and damaged. Most hangars, including those that housed Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptors, were fully unroofed and battered by the strong winds. The 17 Raptors that remained at the base remained relatively unscathed and were brought to airworthy condition within a few days. The base's power, water, and sewage systems were downed, rendering the base uninhabitable. The flight line and drone runway was crippled. The damage toll inflicted to installations at the base reached $3 billion. Large forests in the area were almost entirely flattened to the ground, while trees that remained standing on and around the base were completely stripped and denuded. Three-fourths of the longleaf pine trees on the base were sheared in half, equating to $14 million in harvestable timber losses. Parts of the gymnasium of a nearby elementary school were also unroofed.

An estimated ten to twenty thousand people were displaced by the storm in Panama City, of which one thousand remained at three area shelters. The Panama City area was buffeted by gusts as high as 164 mph (264 km/h), inflicting roof damage and tearing the aluminum siding off of most homes and businesses; at least 90% of all structures and 69% of homes were damaged. Further damage was caused by trees falling upon roofs. A gas leak at an unroofed motel endangered guests who had sought shelter inside. Nine people were rescued by a helicopter after their house's roof collapsed. Cars, truck trailers, recreational vehicles, and trains were tossed around by the wind. A high school's gymnasium had its roof peeled back and some of its interior walls blown apart. Broken glass and snapped utility poles littered the city streets and parking lots. Downed studio transmitter link towers and power outages resulted in the loss of nearly all television and radio stations in the Panama City region. One collapsed tower tore a hole into the roof of the adjoining studio building. Severe roof and siding damage was prevalent in Panama City Beach, where gusts reached 87 mph (140 km/h). At least 98% of structures in Callaway were damaged and 300 properties were tagged as beyond repair by city officials. Nearby, 85% of residential properties and 90% of businesses were damaged in Lynn Haven. The roof of a church was torn away in neighboring Southport. Storm surge inundation exceeded 5.3 ft (1.6 m) along the coast in the Panama City area. Local marinas and boats docked in port were almost entirely destroyed. One person drowned on the eastern side of the Panama City near East Bay.

Forgotten Coast and Apalachee Bay

In addition to the Mexico Beach area, coastal communities in Franklin and Gulf counties—collectively known as the "Forgotten Coast" due to a lack of infrastructure development in recent decades—were among those hardest-hit by Michael. A Florida Department of Environmental Protection survey identified 2,725 structures that sustained major flood damage in Bay, Gulf, Franklin, and Wakulla counties. Over 2,000 structures sustained damage in Gulf County, with over 1,200 suffering major damage and 985 being destroyed. In Franklin County, 80 structures were destroyed. Michael's storm surge created two inlets along St. Joseph Peninsula, cutting off vehicle access to a 9 mi (14 km) stretch of the T.H. Stone Memorial St. Joseph Peninsula State Park and isolating 8 cabins and 119 campsites. The onrush of water flattened the 30 ft (9.1 m) dunes that once filled the park and left the boardwalk dilapidated. The main access road to Cape San Blas was shredded into asphalt sheets. Stretches of US 98 were washed out along the coast. A thousand homes were destroyed by coastal flooding in Port St. Joe and every building sustained damage. Forty homes were later demolished as their structural integrity declined. Many stores along the city's main street were flooded halfway up their first floors. Storefronts were covered in sand piled up by the hurricane and homes and condos were displaced from their foundations. The Port St. Joe marina was severely damaged, contributing to the 400 vessels lost in Gulf and Bay counties. Boats from the marina were forced inland onto a parking lot 300 yd (270 m) from the docks. The failure of 15 pumping stations hamstrung the city's ability to eliminate wastewater. Power lines and crumpled amalgamations of cars lay strewn across roads. Power poles and campers were knocked over in the adjacent community of Highland View.

While Michael's storm surge flooded downtown Apalachicola, the city's buildings weathered the storm with generally minor damage. However, the city was isolated due to the disheveled state of US 98, with parts of the road blocked by felled oak and pine trees and other parts submerged under the advancing seawater. The anemometer at Apalachicola Regional Airport registered gusts of 90 mph (140 km/h) before being blown away. Sections of St. George Island were deeply inundated, and the island may have been entirely underwater during the storm. Although located farther from the storm than St. George Island, homes in Carrabelle sustained more severe damage due to their older and less-elevated construction, resulting in significant flood damage. The road connecting Carrabelle and St. George Island was washed out every few hundred feet. Along the coast of Franklin County from Alligator Point to Bald Point, the roofs of several homes were blown away; beach erosion also occurred throughout the extent. Four homes and an inn on Dog Island were destroyed. As Michael's waves repeatedly battered Dog Island, some of the 15 ships wrecked by the 1899 Carrabelle hurricane became exposed. Owing to the concave geometry of Apalachicola Bay, the 10 ft (3.0 m) storm surge produced by Michael along the coast Wakulla County was particularly damaging. There, the hurricane was considered most damaging in recent memory. Entire communities were swamped by the surge. In St. Marks, the depth of inundation reached 4–5 ft (1.2–1.5 m), with the floodwaters pressing farther inland than in prior storms. Most of the county's electricity customers lost power during Michael's passage. Fallen trees rendered roads impassable.

Aerial views of the Forgotten Coast before and after Hurricane Michael-

Mexico Beach

Mexico Beach

-

Tyndall Beach

Tyndall Beach

-

St. George Island

St. George Island

-

Cape San Blas

Cape San Blas

Elsewhere in Florida

Strong winds from Michael penetrated inland, causing widespread damage to infrastructure and agricultural and forestry interests. Four hundred buildings were destroyed in Jackson County and major damage was inflicted upon another six hundred. Numerous trees and power lines were downed county-wide. Some businesses in Marianna were unroofed, leading to further collapse of exterior walls. The stone façades of buildings in the courthouse square were reduced to rubble. The headquarters of Jackson County's road department collapsed and shopping centers and restaurants suffered heavy damage. One person died in Quincy and another in Alford to felled trees. Strong winds in the heavily forested regions in and around Tallahassee resulted in the widespread downing of trees, forcing the closure of over 125 roads in the city as well as an 80 mi (130 km) segment of I-10 between Tallahassee and Lake Seminole. Florida State Hospital in Chattahoochee—Florida's oldest largest psychiatric hospital—was cut off from the outside world due to power disruptions, forcing aid to be dropped by helicopter. Though localized, acute flooding resulted from Michael's rain swath. Record flooding occurred along Econfina Creek, overtopping a SR 20 bridge. Near Bennett, the creek rose from below action stage to flood stage in under six hours after 5–9 in (130–230 mm) of rain fell within its watershed. Moderate flooding along the Chipola River near Altha damaged homes downstream and inflicted significant damage to fish camps.

Sustained winds in coastal Okaloosa County, located west of Michael's landfall, met low-end tropical storm thresholds, punctuated by higher 60 mph (97 km/h) gusts. Gusts in the tropical storm range extended west to Pensacola and farther inland along the westernmost stretches of the Florida Panhandle, downing trees and power lines. However, the overall impacts of Michael west of Bay County were comparatively muted. On the evening of October 10, 308 customers were without power in Escambia County. Isolated power outages also afflicted Okaloosa County. Gusts in the Pensacola area topped out at 44 mph (71 km/h) and reached 60 mph (97 km/h) in Destin. The Navarre Causeway and the Garcon Point Bridge briefly closed as winds exceeded 39 mph (63 km/h). Storm surge inundation of 2–2.5 ft (0.61–0.76 m) in the Pensacola area occurred ahead of the hurricane due to strong easterly winds, producing minor flooding. Significant beach erosion and road damage was caused by 10–15 ft (3.0–4.6 m) waves along SR 399 between Pensacola Beach and Navarre. Several piers on Choctawhatchee Bay were damaged or destroyed. Neighborhoods along the Santa Rosa Sound were in Pensacola Beach were flooded as the rough surf flowed over barriers.

The outer fringes of Michael affected parts of the peninsular region of Florida well before its ultimate landfall. The combined wind flow from Michael's large circulation and an area of high pressure to the north generated squalls with 35–40 mph (56–64 km/h) gusts over central Florida on October 8; at the time, Michael was located near the western end of Cuba. One boat sank in Lake Monroe due to rough waters generated by the squalls, killing one person and hospitalizing another. Minor saltwater flooding occurred along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of South Florida due to high tides enhanced by storm surge.

Storm surge was responsible for most of the $100,000 damage toll along the coasts of west-central and southwestern Florida. Storm surge topped out at 4.52 ft (1.38 m) at Cedar Key. Similar surge heights occurred in Citrus County, forcing several road closures and washing away a car parked on a road ramp at Fort Island Gulf Beach. Tropical storm-force winds were also felt in isolated areas in the region. A National Ocean Service station in Cedar Key recorded a 53 mph (85 km/h) sustained wind, the highest reported in the region. Cedar Key experienced the worst effects from Michael along the west and southwestern coasts of the Florida peninsula. Two homes and two businesses experienced stormwater inundation, in addition to another four homes in nearby Yankeetown; each building sustained minor damage amounting to roughly $10,000 per building. Michael's outer rainbands spawned at least four waterspouts; one briefly moved ashore Sarasota County 3 mi (4.8 km) northwest of Siesta Key and was classified as an EF0 tornado. Another EF0 tornado was spotted by law enforcement near Camp Blanding.

Georgia

Michael crossed into Georgia in Donalsonville as a weakening, but still strong Category 2 hurricane, where significant damage to structures and trees occurred. Gusts in Donalsonville peaked at 115 mph (185 km/h). Tropical storm force wind gusts were observed as far north as Athens and Atlanta. More than 400,000 electrical customers in Georgia were left without power. At least 127 roads throughout the state were blocked by fallen trees or debris. In Albany, where wind gusts reached 74 mph (119 km/h), 24,270 electrical customers lost power. Numerous trees fell on homes and roads, blocking about 100 intersections. Winds also ripped siding off of homes and shattered windows at the convention center. Three tornadoes were spawned by Michael in Georgia, including a high-end EF1 tornado in Crawford County that knocked down several trees onto homes and destroyed. An 11-year-old girl in Seminole County died after debris fell on her home.

Agriculture across the state suffered tremendous losses. As of October 18, estimated damage in the agriculture industry alone reached $2.38–2.89 billion. Forestry experienced the greatest losses at $1 billion, with about 1 million acres of trees destroyed. Described as a "generational loss", pecan farms in many areas were wiped out. The Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics at the University of Georgia estimated that the pecan crop suffered $100 million in direct losses, with another $260 million in direct losses associated with damage to pecan trees. Farmers were still recovering from damage incurred by Hurricane Irma during the preceding year. The entire crop in Seminole County was lost and 85 percent was lost in Decatur. Initially expected to be a record harvest, a large portion of the cotton crop—worth an estimated $300–800 million—was wiped out. $480 million worth of vegetables were destroyed. In the poultry industry, more than 2 million chickens died due to the storm, and the loss were about $25 million. The insurance claims throughout the state were about $700 million.

Elsewhere

Four EF0 tornadoes were spawned in South Carolina, all of which caused minor tree damage. Moisture streaming northward ahead of Michael led to heavy rainfall across North Carolina on October 11, with most occurring in the basins of the New and Watauga river basins. Most of the rain fell in three to six hours, triggering flash floods. Rainfall totals were generally 4–8 in (100–200 mm) with some localized maxima in excess of 10 in (250 mm). As the cyclone itself passed through North Carolina, it produced wind gusts of 40–60 mph (64–97 km/h) across the central region of the state, blowing down trees onto roads and electric lines; 490,000 Duke Energy customers were left without power late on October 11, and 342,000 remained without power in the state 24 hours later. A tree fell on a car in Statesville, killing the driver. Two others died in Marion when they crashed into a tree that had fallen across a road. Fallen trees damaged homes and hotels in the Research Triangle. The total cost of damage in central North Carolina reached $7.15 million. Winds were stronger along the coast, with a peak gust of 74 mph (119 km/h) measured in Kitty Hawk. The northern Outer Banks experienced minor shingle damage and isolated tree damage as a result of these winds, with Manteo, Kill Devil Hills, and Kitty Hawk experiencing the heaviest impacts from both these winds and storm surge along the Outer Banks.

In Virginia, seven tornadoes touched down: four were rated EF0 and three were rated EF1. The three EF1 tornadoes struck Burkeville, Mannboro, and Toana, blowing roofs off buildings and knocking down trees, some onto homes. A house in Mannboro was shifted slightly off its foundation and had most of its roof uplifted. Flash Flood Emergencies were issued for both Roanoke and Danville on October 11. In the southernmost regions of the state, over 10 in (250 mm) of rain fell. In Danville itself, the 6 in (150 mm) was the most rain to ever fall in a single day. Four people including a firefighter were washed away by floodwaters, and another firefighter was killed in a vehicle collision on Interstate 295. A sixth fatality was discovered when the body of a woman was found on October 13. At least 1,200 roads were closed, and hundreds of trees were downed. Up to 600,000 people were left without power at the height of the storm.

In Maryland, the remnants of Michael dropped 7 in (180 mm) of rain over a period of a few hours in Wicomico County on October 11. Flooding from the Rockawalkin Creek damaged a portion of MD 349, forcing the road to be closed. Homes were flooded in the Canal Woods neighborhood in Salisbury. Three hundred people were forced to evacuate from three apartments in the neighborhood. Michael's remnants also generated strong winds across Maryland, with sustained winds topping out at 38 mph (61 km/h) with gusts reaching 62 mph (100 km/h).

Further north, wind gusts reached as high as 62 mph (100 km/h) at Lewes Beach, Delaware and 54 mph (87 km/h) at Atlantic City Airport in New Jersey. Heavy rainfall was also present in this region, with 3.83 in (97 mm) of rain in Georgetown, Delaware, 3.03 in (77 mm) in Millville, New Jersey, 2.58 in (66 mm) in Atlantic City and 2.29 in (58 mm) in Islip, New York.

Aftermath

On October 9—a day before Hurricane Michael made landfall—President Donald Trump signed an emergency declaration for Florida, which authorized the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to coordinate disaster efforts, with Thomas McCool serving as Federal Coordinating Officer in the state. The declaration also authorized funding for 75% of the cost of emergency protective measures and the removal of storm debris in 14 Florida counties. The federal government also provided for 75% of the cost of emergency protective measures in an additional 21 counties. On October 11, President Trump declared a major disaster in five counties: Bay, Franklin, Gulf, Taylor, and Wakulla. Residents in the county were able to receive grants for house repairs, temporary shelter, loans for uninsured property losses, and business loans. In addition to FEMA, several private and non-profit organizations, including the DSA, PSL, and SRA, established the Hurricane Michael Relief Network which provided direct relief to residents that were affected by the disaster.

Due to the storm damage in Georgia, President Trump also signed an emergency declaration for Georgia, where FEMA activity was coordinated by Manny J. Torro. The declaration authorized funding for 75% of the cost of emergency protective measures and the removal of storm debris in 31 Georgia counties, and 75% of the cost of emergency protective measures in an additional 77 counties.

Florida Governor Ron DeSantis has since requested, with the storm's elevation to Category 5, the federal relief share be increased from 75% to 90%. As of April 2019, either value awaits passage of a specific relief package being delayed in the United States House of Representatives.

Records

| Most intense landfalling Atlantic hurricanes Intensity is measured solely by central pressure | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Landfall pressure |

| 1 | "Labor Day" | 1935 | 892 mbar (hPa) |

| 2 | Camille | 1969 | 900 mbar (hPa) |

| Gilbert | 1988 | ||

| 4 | Dean | 2007 | 905 mbar (hPa) |

| 5 | "Cuba" | 1924 | 910 mbar (hPa) |

| Dorian | 2019 | ||

| 7 | Janet | 1955 | 914 mbar (hPa) |

| Irma | 2017 | ||

| 9 | "Cuba" | 1932 | 918 mbar (hPa) |

| 10 | Michael | 2018 | 919 mbar (hPa) |

| Sources: HURDAT, AOML/HRD, NHC | |||

With maximum sustained winds of 160 mph (260 km/h) and a central pressure of 919 mbar (27.14 inHg) at landfall, Michael was the most intense landfalling mainland U.S. hurricane since Camille in 1969, which had a central pressure of 900 mbar (26.58 inHg) at landfall. Hurricane Michael was the first landfalling Category 5 Atlantic hurricane in the U.S. since Andrew in 1992, which had 165 mph (266 km/h) winds. Michael is tied with the 1928 Okeechobee hurricane for the sixth-strongest tropical cyclone by wind speed to impact the United States (including its overseas territories), and was the fourth strongest to impact the U.S. mainland. Additionally, Michael was the second-most intense hurricane by pressure to make landfall in Florida, behind the 1935 Labor Day hurricane, and the third strongest by wind, behind the 1935 Labor Day hurricane and Andrew.

Michael was the second-most intense hurricane to have made landfall during the month of October in the North Atlantic basin (including the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea), behind the 1924 Cuba hurricane. Michael was the first recorded Category 4 or 5 hurricane to strike the Florida Panhandle since reliable records began in 1851.

Retirement

See also: List of retired Atlantic hurricane namesDue to the extreme damage and loss of life the storm caused along its track, particularly in the Florida Panhandle and southwest Georgia, the World Meteorological Organization retired the name Michael from its rotating name lists in March 2019, and it will never again be used for another Atlantic tropical cyclone. It was replaced with Milton for the 2024 season.

See also

- Tropical cyclones in 2018

- List of Category 5 Atlantic hurricanes

- List of Cuba hurricanes

- List of Florida hurricanes (2000–present)

- Hurricane Opal (1995) – another fast-moving major hurricane which affected Mexico and Central America in its early stages, before striking the Florida Panhandle

- Hurricane Idalia (2023) – a hurricane that had a similar trajectory

- Hurricane Helene (2024) – another hurricane that had a similar path and intensity

- Hurricane Milton (2024) – another October Gulf of Mexico Category 5 hurricane that also struck Florida

Notes

- The position of Michael's Category 5 peak is not depicted in this graphic as it is an asynoptic point (i.e. not at the 6-hour intervals of all other points) occurring at 17:30 UTC October 10.

- A major hurricane is one that ranks at Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson scale.

- Storms with quotations are officially unnamed. Tropical storms and hurricanes were not named before the year 1950.

References

- ^ Beven, John; Berg, Robbie; Hagen, Andrew (May 17, 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Michael (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 29, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ "Assessing the U.S. Climate in 2018". National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI). February 6, 2019. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- ^ Global Catastrophe Recap October 2018 (PDF). AON (Report). AON. November 7, 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 16, 2018. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- "While Trump Calls Climate Change a Hoax, Hurricane Michael Damaged US Fighter Jets Worth $6 Billion". Democracy Now!. October 26, 2018. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- "Hurricane Michael insured losses near $5.53 billion". The News-Herald. The News Service of Florida. February 7, 2019. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

- ^ Liz Fabian (October 23, 2018). "Georgia nears $700 million in Hurricane Michael insured losses as victims begin recovery". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on October 25, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ^ "Breaking down Michael's estimated $3 billion hit to Georgia agriculture". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. October 18, 2018. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

- "Hurricane Michael tally at $5 billion in property damage, $1.5 billion in crop loss". Watchdog.org. January 8, 2019. Retrieved January 9, 2019.

- Stewart, Stacy (October 2, 2018). Atlantic Tropical Weather Outlook [200 AM EDT Tue Oct 2 2018] (Report). NHC Graphical Outlook Archive. National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on March 5, 2019. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- Avila, Lixion (October 3, 2018). Atlantic Tropical Weather Outlook [800 PM EDT Tue Oct 2 2018] (Report). NHC Graphical Outlook Archive. National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ Beven, Jack (October 6, 2018). Potential Tropical Cyclone Fourteen Discussion Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on March 5, 2019. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- Avila, Lixion (October 7, 2018). Potential Tropical Cyclone Fourteen Discussion Number 2 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on July 8, 2020. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- Berg, Robbie (October 7, 2018). Tropical Depression Fourteen Discussion Number 3 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on March 5, 2019. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- Brown, Daniel (October 7, 2018). Tropical Storm Michael Discussion Number 5 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on July 8, 2020. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ^ Stewart, Stacy (October 8, 2018). Tropical Storm Michael Discussion Number 6 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on March 5, 2019. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- Berg, Robbie (October 8, 2018). Tropical Storm Michael Discussion Number 7 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on January 14, 2019. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ^ Daniel, Brown (October 8, 2018). Hurricane Michael Discussion Number 8 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on March 5, 2019. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ^ Beven, Jack (October 9, 2018). Hurricane Michael Discussion Number 11 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- Brown, Daniel (October 9, 2018). Hurricane Michael Discussion Number 12 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on July 8, 2020. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- "Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on June 20, 2020. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- Brown, Daniel (October 9, 2018). Hurricane Michael Discussion Number 13 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on March 5, 2019. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- Stewart, Stacy (October 10, 2018). Hurricane Michael Discussion Number 14 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on March 5, 2019. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- Beven, Jack (October 10, 2018). Hurricane Michael Tropical Cyclone Update (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- Brown, Daniel (October 10, 2018). Hurricane Michael Discussion Number 16 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ Brown, Daniel (October 10, 2018). Hurricane Michael Discussion Number 17 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on July 8, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ Stewart, Stacy (October 11, 2018). Hurricane Michael Discussion Number 18 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- Beven, Jack (October 11, 2018). Tropical Storm Michael Discussion Number 19 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on July 10, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ Brown, Daniel (October 11, 2018). Tropical Storm Michael Discussion Number 21 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on October 12, 2018. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- Berg, Robbie (October 12, 2018). Tropical Storm Michael Discussion Number 22 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- Chaitin, Daniel (October 16, 2018). "When Michael met Leslie: Ex-hurricanes dance, merge over Spain". Washington Examiner. Archived from the original on June 3, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- Cappucci, Matthew (October 16, 2018). "Zombie storm Leslie slammed Portugal, France and Spain with unusual strength". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- Europe Weather Analysis on 2018-10-15 (Map). Free University of Berlin. October 15, 2018. Archived from the original on January 24, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2018.

- Europe Weather Analysis on 2018-10-16 (Map). Free University of Berlin. October 16, 2018. Archived from the original on January 24, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2018.

- "Americas: Weather Events Information Bulletin N° 1". reliefweb. OCHA. October 10, 2018. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- Reeves, Jay; Farrington, Brendan (October 10, 2018). "Hurricane Michael makes landfall as a Category 4 storm". PBS. Associated Press. Retrieved November 23, 2022.

- ^ Farrington, Brendan; Lush, Tamara (October 9, 2018). "Major Hurricane Michael bearing down on Florida Panhandle". Associated Press News. Retrieved November 23, 2022.

- Haddad, Ken (October 10, 2018). "List of mandatory evacuation zones in Florida ahead of Hurricane Michael". Detroit, Michigan: ClickOnDetroit.com. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- Senkbeil, Jason; Myers, Laura; Jasko, Susan; Reed, Jacob; Mueller, Rebecca (July 30, 2020). "Communication and Hazard Perception Lessons from Category Five Hurricane Michael". Atmosphere. 11 (8). MDPI: 804. Bibcode:2020Atmos..11..804S. doi:10.3390/atmos11080804.

- MacFarlane, Drew (October 9, 2018). "Florida Gov. Scott: Michael Could Bring 'Total Devastation'; Mandatory Evacuations Ordered Along Panhandle". The Weather Channel. Retrieved November 23, 2022.

- "Congaree National Park closing until further notice due to incoming storms". Cola Daily. October 9, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2024.

- "National Forests in Florida - News and Events". United States Forest Service. October 11, 2018. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- McWilliams, Gary; Hampton, Liz (October 8, 2018). "Gulf of Mexico offshore platforms evacuated ahead of hurricane". Reuters. Retrieved November 23, 2022.

- Strigus, Eric (October 9, 2018). "South Georgia college campuses closing in preparation of Hurricane Michael". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- Mines, Adam (October 9, 2018). "Atlanta Motor Speedway opening camping facilities for Hurricane Michael evacuees". Macon, GA: WGXA. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

- "Hurricane Michael - LIVE: Tropical cyclone on path for Florida hits Category 4 with 130mph winds". The Independent. October 10, 2018. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- "Hurricane Michael". Direct Relief. October 10, 2018. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- "Hurricane Michael death toll continues to rise". WJHG-TV. January 11, 2019. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ^ "Tres muertos y más de 1900 viviendas afectadas por lluvias". Confidencial (in Spanish). October 6, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ^ "Sube a ocho el número de muertos por las lluvias en Honduras". El Nuevo Diario (in Spanish). October 10, 2018. Archived from the original on October 13, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- "Al menos 9 muertos y miles de afectados por un temporal en Centroamérica". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). October 7, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- Pam Wright (October 8, 2018). "Hurricane Michael Brings Flooding Rains to Central America, Forcing Evacuations in Honduras". weather.com. The Weather Company. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- Morales, Benjamín (October 8, 2018). "Michael se aleja de Cuba tras dejar daños en el occidente". El Nuevo Día (in Spanish). Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- Vela, Hatzel; Torres, Andrea (October 9, 2018). "Hurricane Michael causes some destruction in western Cuba". Local10.com. Pinar del Rio, Cuba: WPLG, Inc. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- ^ "Huracán Michael deja daños significativos en Cuba" (in Spanish). Conexión Capital. October 10, 2018. Archived from the original on October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- "Hurricane Michael brings floods, surges, destruction to western Cuba". Havana, Cuba: Radio Havana Cuba. October 9, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- "Empieza la recuperación de zonas dañadas por el paso del huracán Michael en Cuba" (in Spanish). Cibercuba. Agencia EFE. October 11, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- Landsea, Chris; Anderson, Craig; Bredemeyer, William; et al. (January 2022). Continental United States Hurricanes (Detailed Description). Re-Analysis Project (Report). Miami, Florida: Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved January 4, 2025.

- "Hurricane Michael leaves 1.2 million in the dark from Florida to Virginia". Washington Examiner. October 12, 2018. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- ^ "Catastrophic Hurricane Michael Strikes Florida Panhandle October 10, 2018". Hurricane Michael 2018. Tallahassee, Florida: National Weather Service Tallahassee, Florida. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- Hurricane Michael: Field Assessment Team 1 (FAT-1) Early Access Reconnaissance Report (EARR) (PDF) (Report). Tallahassee, Florida: Structural Extreme Event Reconnaissance Network. October 25, 2018. Retrieved March 13, 2020 – via National Weather Service Tallahassee, Florida.

- "Hurricane Michael Storm Damage Assessment" (PDF). Florida Department of Highway Safety and Motor Vehicles. October 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Initial Value Estimate of Altered, Damaged or Destroyed Timber in Florida (PDF) (Report). Tallahassee, Florida: Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. October 19, 2018. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- Zampieri, Nicole E.; Pau, Stephanie; Okamoto, Daniel K. (December 2020). "The impact of Hurricane Michael on longleaf pine habitats in Florida". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 8483. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.8483Z. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-65436-9. PMC 7242371. PMID 32439960.

- ^ Hinson, Stuart, ed. (October 2018). "Storm Data: October 2018" (PDF). Storm Data. 60 (10). Asheville, North Carolina: National Centers for Environmental Information. ISSN 0039-1972. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 12, 2020. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- Alvarez, Sergio (October 30, 2018). "Hurricane Michael's Damage to Florida Agriculture" (PDF). Tallahassee, Florida: Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Livingston, Ian (April 19, 2019). "Hurricane Center reclassifies Michael to Category 5, the first such storm to make landfall since 1992". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. Retrieved March 11, 2020. (subscription required)

- ^ Hurricane Michael in Florida (PDF) (Mtigiation Assessment Team Report). Washington, D.C.: Federal Emergency Management Agency. February 2020. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- "Hurricane Michael caused 1.7 million electricity outages in the Southeast United States". Today in Energy. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Energy Information Administration. October 22, 2018. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- ^ "Hurricane Michael Post-Storm Beach Conditions and Coastal Impact Report" (PDF). Tallahassee, Florida: Florida Department of Environmental Protection. April 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- Achenbach, Joel; Begos, Kevin; Samenow, Jason (November 16, 2018). "Hurricane Michael is looking even more violent on closer scrutiny". NWFDailyNews.com. Gannett Co., Inc. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ "Hurricane Michael Event Recap Report" (PDF). Aon. March 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 1, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- Brackett, Ron (October 12, 2018). "Hurricane Michael Update: Bodies Found on Florida's Mexico Beach; Toll Had Already Reached 13". weather.com. Atlanta, Georgia: The Weather Company. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ "Mexico Beach, FL is unrecognizable after Hurricane Michael". Cleveland, Ohio: WKYC-TV. Associated Press. October 11, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ Sampson, Zachary T. (October 11, 2018). "Ground zero: See the damage Hurricane Michael inflicted on Mexico Beach". Tampa Bay Times. Tampa, Florida. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Sullivan, Patricia; Wax-Thibodeaux, Emily; Gowen, Annie (October 12, 2018). "'It's all gone': Tiny Florida beach town nearly swept away by Hurricane Michael". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. Retrieved March 14, 2020. (subscription required)

- Sampson, Zachary T. (October 12, 2018). "'We're broken here.' Mexico Beach reels in the aftermath of Hurricane Michael". Tampa Bay Times. Tampa, Florida. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Breaux, Collin (October 1, 2019). "U.S. 98 open again in Mexico Beach following Hurricane Michael damage repairs". Panama City News Herald. Panama City, Florida: Gannett Co., Inc. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ O'Donoghue, Gary (October 13, 2018). "Hurricane Michael flattens beach town like 'mother of all bombs'". BBC News. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Vanden Brook, Tom (October 11, 2018). "Michael blasted Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida – a key to homeland security". USA Today. Gannett Satellite Information Network, LLC. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ Achenbach, Joel; Begos, Kevin; Lamothe, Dan (October 23, 2018). "Hurricane Michael: Tyndall Air Force Base was in the eye of the storm, and almost every structure was damaged". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ Martinez, Luis (October 12, 2018). "'Complete devastation' at Tyndall AFB after direct hit from Michael". ABC News. ABC News Internet Ventures. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Reeves, Magen M. (October 10, 2019). "Tyndall one year after Hurricane Michael". Tyndall Air Force Base. Tyndall Air Force Base, Florida: United States Air Force. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ "Tyndall Air Force Base Sustains 'Catastrophic' Damage". US News. U.S. News & World Report L.P. Associated Press. October 12, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Everstine, Brian W. (November 2, 2018). "For Many, Rebuilding Tyndall is Personal". Air Force Magazine. Air Force Association. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Mizokami, Kyle (November 6, 2018). "Hurricane-Battered F-22s Are Now Flying Out of Michael's Aftermath". Popular Mechanics. Hearst Magazine Media, Inc. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Lasin, Julius (October 12, 2018). "Tyndall AFB: Florida air force base suffers major Hurricane Michael damage, see the video". Pensacola News Journal. Pensacola, Florida: PNJ.com. USA Today Network. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Hurricane Michael Preliminary Virtual Assessment Team (P-VAT) Report (PDF) (Report). Structural Extreme Event Reconnaissance Network. October 15, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2020 – via National Weather Service Tallahassee, Floriday.

- Chapman, Dan (June 7, 2019). "Hurricane Michael allows Service, Air Force to increase longleaf pine restoration". Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original on December 31, 2019. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Reeves, Magen M. (January 16, 2020). "Deforestation on Tyndall AFB leads to ecosystem restoration". Tyndall Air Force Base, Florida: United States Air Force. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Thrush, Glenn (October 29, 2018). "A Florida City, Hit Hard by Hurricane Michael, Seeks More Housing Aid". The New York Times. New York, New York. Retrieved March 14, 2020. (subscription required)

- Neale, Rick (May 23, 2019). "Mexico Beach, Florida's Panhandle still reeling 7 months after Hurricane Michael struck". Florida Today. FloridaToday.com. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ Crowder, Valerie (October 11, 2019). "Hurricane Michael A Year Later: Panama City Code Enforcement Starting Crackdown On Property Neglect". Miami, Florida: WLRN. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ Braun, Michael (October 10, 2018). "In a harrowing two hours, Hurricane Michael devastates Panama City". Florida Today. FloridaToday.com. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- "At least six dead as storm blows through Carolinas – as it happened". The Guardian. February 12, 2019. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Fausset, Richard; Blinder, Alan; Mazzei, Patricia (October 10, 2018). "Hurricane Michael Leaves Trail of Destruction as It Slams Florida's Panhandle". The New York Times. New York, New York. Retrieved March 14, 2020. (subscription required)

- Detman, Gary (October 11, 2018). "Hurricane Michael peels roof from high school gym in Panama City". West Palm Beach, Florida: CBS 12. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Hughes, Trevor; Neale, Rick; Robinson, Kevin (October 11, 2018). "Hurricane Michael cripples Panama City with heartbreaking devastation". Pensacola News Journal. Pensacola, Florida: PNJ.com. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Venta, Lance (October 10, 2018). "Hurricane Michael Takes Panama City Off The Air". RadioInsight. RadioInsight.com. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Venta, Lance (October 13, 2018). "Powell Broadcasting To Cease Panama City Operations". RadioInsight. RadioInsight.com. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Ortiz, Erik; Abdelkader, Rima; Gostanian, Ali; Helsel, Phil (October 11, 2018). "Panama City bears brunt of Hurricane Michael's destructive force". NBC News. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ Etters, Karl (January 18, 2019). "BREACHED BEACH: Battered St. Joseph Peninsula State Park reopening after Hurricane Michael". Tallahassee Democrat. Tallahassee, Florida: Tallahassee.com. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Solomon, Josh (October 15, 2018). "In Cape San Blas, a wary walk to find out what Michael left behind". Tampa Bay Times. Tampa, Florida. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ Dove, Patrick (October 13, 2018). "Residents of Port St. Joe among those hardest hit by Hurricane Michael". TCPalm. Port St. Lucie, Florida. Treasure Coast News. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ Adams, Alicia (October 20, 2018). "HURRICANE MICHAEL: Port St. Joe struggles for normalcy". Northwest Florida Daily News. Fort Walton Beach, Florida: Gannett Co., Inc. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ Schweers, Tallahassee (February 24, 2019). "THE TOURISM TEST: 'It'll be rough' but Port St. Joe sees path forward after Hurricane Michael". Tallahassee Democrat. Tallahassee, Florida: Tallahassee.com. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- "In hardest-hit towns, Hurricane Michael leaves nothing unscathed". CBS This Morning. CBS News. October 11, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Mazzei, Patricia (October 12, 2018). "For a Struggling Oyster Town, Hurricane Michael May Be One Misery Too Many". The New York Times. New York, New York. Retrieved March 14, 2020. (subscription required)

- Allen, Greg (October 13, 2018). "Michael Recovery: Apalachicola, Fla., Begins To Rebuild". NPR. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Begos, Kevin; Berman, Mark; Lazo, Luz; Achenbach, Joel (October 10, 2018). "'We're kind of getting crushed': Record-breaking Hurricane Michael slams Florida". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. Retrieved March 14, 2020. (subscription required)

- "Hurricane Michael Damage Assessment: Carrabelle and St. George Island". Woodbury, New Jersey: Vanguard. October 23, 2018. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- "Hurricane Michael aftermath in Franklin County". Tallahassee, Florida: WTXL-TV. September 30, 2019. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Adlerstein, David (October 25, 2018). "Apalachicola destruction: 'We're going to see a huge drop in the tax rolls'". Northwest Florida Daily News. Fort Walton Beach, Florida: Gannett Co., Inc. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Etters, Karl (October 20, 2018). "Hurricane Michael unearthed 19th century shipwrecks in Florida". USA Today. Tallahassee Democrat. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Burlew, Jeff (October 11, 2018). "Michael hit Wakulla County harder than any other hurricane in memory". Tallahassee Democrat. Tallahassee, Florida: Tallahassee.com. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ Burlew, Jeff (January 27, 2019). "Hurricane Michael: 'Like a bomb went off' in Jackson County, Marianna". Tallahassee Democrat. Tallahassee, Florida: Tallahassee.com. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- "Hurricane Michael leaves Florida's main psych hospital cut off. Helicopters drop aid". Miami Herald. Miami, Florida: Miami Herald Media Company. Miami Herald, Times Tallahassee Bureau. October 11, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Victoria, Wendy (October 19, 2018). "Western counties escape the brunt of Michael". NWFDailyNews.com. Fort Walton Beach, Florida: Gannett Co., Inc. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- McLaughlin, Tom (October 10, 2018). "OKALOOSA UPDATE: County may be spared hurricane-force winds". Northwest Florida Daily News. Pensacola, Florida: Gannett Co., Inc. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- "Hurricane Michael spares Pensacola area from its wrath". Pensacola News Journal. Pensacola, Florida: PNJ.com. October 10, 2018. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- Pippin, Cory (October 10, 2018). "Santa Rosa Sound rises during Hurricane Michael, floods entire neighborhoods". WEAR-TV. Pensacola, Florida: Sinclair Broadcast Group. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- ^ Northam, Mitchell; Godwin, Becca J. G.; Habersham, Raisa (October 11, 2018). "Hurricane Michael in Georgia: Damage by the numbers". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ^ "Hurricane Michael Hits Georgia". National Weather Service. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- Jessica Fieux (October 18, 2018). Post Tropical Cyclone Report Hurricane Michael (Report). Archived from the original on October 21, 2018. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

- Brasch, Ben; Edwards, Johnny; Boone, Christian (October 11, 2018). "Hurricane Michael: Damage in Georgia is 'phenomenal'". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- "Hurricane Michael's Impact on Georgia's Agricultural Economy" (PDF). University of Georgia Extension. November 1, 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 23, 2022. Retrieved November 23, 2022 – via Georgia Department of Agriculture.

- "Hurricane Michael South Carolina Tornadoes". National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service. Retrieved September 12, 2021.

- Henderson, Bruce (October 12, 2018). "More than 400,000 in Carolinas still without power after Tropical Storm Michael". The Charlotte Observer. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- "1st death reported in NC from Michael". CBS 17 News. October 11, 2018. Archived from the original on October 12, 2018. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ Wright, Pam (October 13, 2018). "Michael Death Toll Climbs to 18; Search Continues for Missing". weather.com. The Weather Company. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- "Winds from Tropical Storm Michael cause heavy damage across North Carolina". ABC11. Durham, North Carolina: ABC, Inc. Associated Press. October 11, 2018.

- "Hurricane Michael Virginia Tornadoes". National Centers for Environmental Information. National Weather Service. Retrieved September 12, 2021.

- Thompson, Kara (October 10, 2019). "One year later: Meteorologist Kara Thompson looks back on Hurricane Michael in Virginia". WFXR. Archived from the original on November 24, 2023. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

- "Hurricane Michael: The strongest storm of 2018's season brought flooding to southwest Virginia". WFXR. June 1, 2021. Retrieved October 4, 2024.

- "Michael breaks all-time rain record in Danville". WSLS. October 13, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2024.

- Hedgpeth, Dana. "Five people are dead, 1,200 roads closed and half-a-million people are without power after Michael ravages Virginia". The Washington Post. No. October 12, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- "Death toll from TS Michael up to 6 in Virginia". WHSV-TV3. October 13, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- Tyszko, Erin (October 15, 2018). "Nanticoke Road Closure in Wicomico County". Salisbury, MD: WBOC-TV. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- "Major Flooding in Canal Woods After Tropical Storm Michael". Salisbury, MD: WBOC-TV. October 12, 2018. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- Desai, Kamleshkumar; Harding, Hayley; Vaughn, Carol; Gamard, Sarah (October 12, 2018). "Tropical Storm Michael: 'This is a mess' Salisbury residents leave homes from flooding; wind, rain cuts through Delmarva". Delmarva Now. Salisbury, Maryland. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- Hurricane Michael Recap: Historic Category 5 Florida Panhandle Landfall and Inland Wind Damage Swath, The Weather Channel, September 21, 2023

- "President Donald J. Trump Signs Emergency Declaration for Florida". FEMA. October 9, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- "President Donald J. Trump Approves Major Disaster Declaration for Florida". FEMA. October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- Arria, Michael (December 14, 2018). "Left-Wing Disaster Relief Efforts Spread Goodwill for Socialism". Truthout. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- "President Donald J. Trump Signs Emergency Declaration for Georgia". FEMA. October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- Katie Landeck (April 23, 2019). "DeSantis asks Trump to increase Hurricane Michael cleanup money". Panama City News Herald. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- Alana Austin (April 10, 2019). "FL lawmaker reflects on six months since Hurricane Michael's destruction". Gray DC. Gray Television, Inc. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- Landsea, Christopher; Dorst, Neal (June 1, 2014). "Subject: Tropical Cyclone Names: B1) How are tropical cyclones named?". Tropical Cyclone Frequently Asked Question. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Hurricane Research Division. Archived from the original on December 10, 2018.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved January 4, 2025.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Landsea, Chris (April 2022). "The revised Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT2) - Chris Landsea – April 2022" (PDF). Hurricane Research Division – NOAA/AOML. Miami: Hurricane Research Division – via Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory.

- Landsea, Chris; Anderson, Craig; Bredemeyer, William; Carrasco, Cristina; Charles, Noel; Chenoweth, Michael; Clark, Gil; Delgado, Sandy; Dunion, Jason; Ellis, Ryan; Fernandez-Partagas, Jose; Feuer, Steve; Gamanche, John; Glenn, David; Hagen, Andrew; Hufstetler, Lyle; Mock, Cary; Neumann, Charlie; Perez Suarez, Ramon; Prieto, Ricardo; Sanchez-Sesma, Jorge; Santiago, Adrian; Sims, Jamese; Thomas, Donna; Lenworth, Woolcock; Zimmer, Mark (May 2015). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Metadata). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 4, 2025.

- Franklin, James (January 31, 2008). Hurricane Dean (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 4, 2025.

- Reeves, Jay; Farrington, Brendan (October 10, 2018). "Hurricane Michael devastates Mexico Beach, Florida, in historic Category 4 landfall". Sun-Sentinel. Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- Klotzbach, Philip (October 10, 2018). "Table of 10 Strongest Continental US Landfalling #Hurricanes on Record as Ranked by Maximum Sustained Wind. Michael Ranks Fourth with Sustained Winds of 135 knots (155 mph) at Landfall" (Tweet). Retrieved October 10, 2018 – via Twitter.

- Klotzbach, Philip (October 11, 2018). "Michael Made History as One of the Top Four Strongest Hurricanes to Strike the United States". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- Uhlhorn, Eric; Lorsolo, Sylvie (October 10, 2018). "Why Hurricane Michael's Landfall Is Historic". Air-Worldwide. Archived from the original on October 16, 2018. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- Klotzbach, Philip (October 10, 2018). "Hurricane Michael has Made Landfall with Max Sustained Winds of 155 mph - the First Category 5 Hurricane to Make Landfall in the Florida Panhandle on Record" (Tweet). Retrieved October 10, 2018 – via Twitter.