| Part of a series on | ||||

| Numeral systems | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Place-value notation

|

||||

Sign-value notation

|

||||

| List of numeral systems | ||||

Hexadecimal (also known as base-16 or simply hex) is a positional numeral system that represents numbers using a radix (base) of sixteen. Unlike the decimal system representing numbers using ten symbols, hexadecimal uses sixteen distinct symbols, most often the symbols "0"–"9" to represent values 0 to 9 and "A"–"F" to represent values from ten to fifteen.

Software developers and system designers widely use hexadecimal numbers because they provide a convenient representation of binary-coded values. Each hexadecimal digit represents four bits (binary digits), also known as a nibble (or nybble). For example, a 6-bit byte can have values ranging from 000000 to 111111 (0 to 63 decimal) in binary form, which can be written as 00 to 3F in hexadecimal.

In mathematics, a subscript is typically used to specify the base. For example, the decimal value 711 would be expressed in hexadecimal as 2C716. In programming, several notations denote hexadecimal numbers, usually involving a prefix. The prefix 0x is used in C, which would denote this value as 0x2C7.

Hexadecimal is used in the transfer encoding Base 16, in which each byte of the plain text is broken into two 4-bit values and represented by two hexadecimal digits.

Representation

Written representation

In most current use cases, the letters A–F or a–f represent the values 10–15, while the numerals 0–9 are used to represent their decimal values.

There is no universal convention to use lowercase or uppercase, so each is prevalent or preferred in particular environments by community standards or convention; even mixed case is used. Some seven-segment displays use mixed-case 'A b C d E F' to distinguish the digits A–F from one another and from 0–9.

There is some standardization of using spaces (rather than commas or another punctuation mark) to separate hex values in a long list. For instance, in the following hex dump, each 8-bit byte is a 2-digit hex number, with spaces between them, while the 32-bit offset at the start is an 8-digit hex number.

00000000 57 69 6b 69 70 65 64 69 61 2c 20 74 68 65 20 66 00000010 72 65 65 20 65 6e 63 79 63 6c 6f 70 65 64 69 61 00000020 20 74 68 61 74 20 61 6e 79 6f 6e 65 20 63 61 6e 00000030 20 65 64 69 74 0a

Distinguishing from decimal

In contexts where the base is not clear, hexadecimal numbers can be ambiguous and confused with numbers expressed in other bases. There are several conventions for expressing values unambiguously. A numerical subscript (itself written in decimal) can give the base explicitly: 15910 is decimal 159; 15916 is hexadecimal 159, which equals 34510. Some authors prefer a text subscript, such as 159decimal and 159hex, or 159d and 159h.

Donald Knuth introduced the use of a particular typeface to represent a particular radix in his book The TeXbook. Hexadecimal representations are written there in a typewriter typeface: 5A3, C1F27ED

In linear text systems, such as those used in most computer programming environments, a variety of methods have arisen:

- Although best known from the C programming language (and the many languages influenced by C), the prefix

0xto indicate a hex constant may have had origins in the IBM Stretch systems. It is derived from the0prefix already in use for octal constants. Byte values can be expressed in hexadecimal with the prefix\xfollowed by two hex digits:'\x1B'represents the Esc control character;"\x1B[0m\x1B[25;1H"is a string containing 11 characters with two embedded Esc characters. To output an integer as hexadecimal with the printf function family, the format conversion code%Xor%xis used. - In XML and XHTML, characters can be expressed as hexadecimal numeric character references using the notation

ode;, for instanceTrepresents the character U+0054 (the uppercase letter "T"). If there is noxthe number is decimal (thusTis the same character). - In Intel-derived assembly languages and Modula-2, hexadecimal is denoted with a suffixed H or h:

FFhor05A3H. Some implementations require a leading zero when the first hexadecimal digit character is not a decimal digit, so one would write0FFhinstead ofFFh. Some other implementations (such as NASM) allow C-style numbers (0x42). - Other assembly languages (6502, Motorola), Pascal, Delphi, some versions of BASIC (Commodore), GameMaker Language, Godot and Forth use

$as a prefix:$5A3,$C1F27ED. - Some assembly languages (Microchip) use the notation

H'ABCD'(for ABCD16). Similarly, Fortran 95 uses Z'ABCD'. - Ada and VHDL enclose hexadecimal numerals in based "numeric quotes":

16#5A3#,16#C1F27ED#. For bit vector constants VHDL uses the notationx"5A3",x"C1F27ED". - Verilog represents hexadecimal constants in the form

8'hFF, where 8 is the number of bits in the value and FF is the hexadecimal constant. - The Icon and Smalltalk languages use the prefix

16r:16r5A3 - PostScript and the Bourne shell and its derivatives denote hex with prefix

16#:16#5A3,16#C1F27ED. - Common Lisp uses the prefixes

#xand#16r. Setting the variables *read-base* and *print-base* to 16 can also be used to switch the reader and printer of a Common Lisp system to Hexadecimal number representation for reading and printing numbers. Thus Hexadecimal numbers can be represented without the #x or #16r prefix code, when the input or output base has been changed to 16. - MSX BASIC, QuickBASIC, FreeBASIC and Visual Basic prefix hexadecimal numbers with

&H:&H5A3 - BBC BASIC and Locomotive BASIC use

&for hex. - TI-89 and 92 series uses a

0hprefix:0h5A3,0hC1F27ED - ALGOL 68 uses the prefix

16rto denote hexadecimal numbers:16r5a3,16rC1F27ED. Binary, quaternary (base-4), and octal numbers can be specified similarly. - The most common format for hexadecimal on IBM mainframes (zSeries) and midrange computers (IBM i) running the traditional OS's (zOS, zVSE, zVM, TPF, IBM i) is

X'5A3'orX'C1F27ED', and is used in Assembler, PL/I, COBOL, JCL, scripts, commands and other places. This format was common on other (and now obsolete) IBM systems as well. Occasionally quotation marks were used instead of apostrophes.

Syntax that is always Hex

Sometimes the numbers are known to be Hex.

- In URIs (including URLs), character codes are written as hexadecimal pairs prefixed with

%:http://www.example.com/name%20with%20spaceswhere%20is the code for the space (blank) character, ASCII code point 20 in hex, 32 in decimal. - In the Unicode standard, a character value is represented with

U+followed by the hex value, e.g.U+00A1is the inverted exclamation point (¡). - Color references in HTML, CSS and X Window can be expressed with six hexadecimal digits (two each for the red, green and blue components, in that order) prefixed with

#: magenta, for example, is represented as#FF00FF. CSS also allows 3-hexdigit abbreviations with one hexdigit per component:#FA3abbreviates#FFAA33(a golden orange: ). - In MIME (e-mail extensions) quoted-printable encoding, character codes are written as hexadecimal pairs prefixed with

=:Espa=F1ais "España" (F1hex is the code for ñ in the ISO/IEC 8859-1 character set).) - PostScript binary data (such as image pixels) can be expressed as unprefixed consecutive hexadecimal pairs:

AA213FD51B3801043FBC... - Any IPv6 address can be written as eight groups of four hexadecimal digits (sometimes called hextets), where each group is separated by a colon (

:). This, for example, is a valid IPv6 address:2001:0db8:85a3:0000:0000:8a2e:0370:7334or abbreviated by removing leading zeros as2001:db8:85a3::8a2e:370:7334(IPv4 addresses are usually written in decimal). - Globally unique identifiers are written as thirty-two hexadecimal digits, often in unequal hyphen-separated groupings, for example

3F2504E0-4F89-41D3-9A0C-0305E82C3301.

Other symbols for 10–15 and mostly different symbol sets

The use of the letters A through F to represent the digits above 9 was not universal in the early history of computers.

- During the 1950s, some installations, such as Bendix-14, favored using the digits 0 through 5 with an overline to denote the values 10–15 as 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5.

- The SWAC (1950) and Bendix G-15 (1956) computers used the lowercase letters u, v, w, x, y and z for the values 10 to 15.

- The ORDVAC and ILLIAC I (1952) computers (and some derived designs, e.g. BRLESC) used the uppercase letters K, S, N, J, F and L for the values 10 to 15.

- The Librascope LGP-30 (1956) used the letters F, G, J, K, Q and W for the values 10 to 15.

- On the PERM (1956) computer, hexadecimal numbers were written as letters O for zero, A to N and P for 1 to 15. Many machine instructions had mnemonic hex-codes (A=add, M=multiply, L=load, F=fixed-point etc.); programs were written without instruction names.

- The Honeywell Datamatic D-1000 (1957) used the lowercase letters b, c, d, e, f, and g whereas the Elbit 100 (1967) used the uppercase letters B, C, D, E, F and G for the values 10 to 15.

- The Monrobot XI (1960) used the letters S, T, U, V, W and X for the values 10 to 15.

- The NEC parametron computer NEAC 1103 (1960) used the letters D, G, H, J, K (and possibly V) for values 10–15.

- The Pacific Data Systems 1020 (1964) used the letters L, C, A, S, M and D for the values 10 to 15.

- New numeric symbols and names were introduced in the Bibi-binary notation by Boby Lapointe in 1968.

- Bruce Alan Martin of Brookhaven National Laboratory considered the choice of A–F "ridiculous". In a 1968 letter to the editor of the CACM, he proposed an entirely new set of symbols based on the bit locations.

- In 1972, Ronald O. Whitaker of Rowco Engineering Co. proposed a triangular font that allows "direct binary reading" to "permit both input and output from computers without respect to encoding matrices."

- Some seven-segment display decoder chips (i.e., 74LS47) show unexpected output due to logic designed only to produce 0–9 correctly.

Verbal and digital representations

Since there were no traditional numerals to represent the quantities from ten to fifteen, alphabetic letters were re-employed as a substitute. Most European languages lack non-decimal-based words for some of the numerals eleven to fifteen. Some people read hexadecimal numbers digit by digit, like a phone number, or using the NATO phonetic alphabet, the Joint Army/Navy Phonetic Alphabet, or a similar ad-hoc system. In the wake of the adoption of hexadecimal among IBM System/360 programmers, Magnuson (1968) suggested a pronunciation guide that gave short names to the letters of hexadecimal – for instance, "A" was pronounced "ann", B "bet", C "chris", etc. Another naming-system was published online by Rogers (2007) that tries to make the verbal representation distinguishable in any case, even when the actual number does not contain numbers A–F. Examples are listed in the tables below. Yet another naming system was elaborated by Babb (2015), based on a joke in Silicon Valley.

Others have proposed using the verbal Morse Code conventions to express four-bit hexadecimal digits, with "dit" and "dah" representing zero and one, respectively, so that "0000" is voiced as "dit-dit-dit-dit" (....), dah-dit-dit-dah (-..-) voices the digit with a value of nine, and "dah-dah-dah-dah" (----) voices the hexadecimal digit for decimal 15.

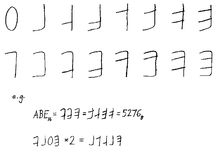

Systems of counting on digits have been devised for both binary and hexadecimal. Arthur C. Clarke suggested using each finger as an on/off bit, allowing finger counting from zero to 102310 on ten fingers. Another system for counting up to FF16 (25510) is illustrated on the right.

| Number | Pronunciation |

|---|---|

| A | ann |

| B | bet |

| C | chris |

| D | dot |

| E | ernest |

| F | frost |

| 1A | annteen |

| A0 | annty |

| 5B | fifty-bet |

| A01C | annty christeen |

| 1AD0 | annteen dotty |

| 3A7D | thirty-ann seventy-dot |

| Number | Pronunciation |

|---|---|

| A | ten |

| B | eleven |

| C | twelve |

| D | draze |

| E | eptwin |

| F | fim |

| 10 | tex |

| 11 | oneteek |

| 1F | fimteek |

| 50 | fiftek |

| C0 | twelftek |

| 100 | hundrek |

| 1000 | thousek |

| 3E | thirtek-eptwin |

| E1 | eptek-one |

| C4A | twelve-hundrek-fourtek-ten |

| 1743 | one-thousek-seven- -hundrek-fourtek-three |

Signs

The hexadecimal system can express negative numbers the same way as in decimal: −2A to represent −4210, −B01D9 to represent −72136910 and so on.

Hexadecimal can also be used to express the exact bit patterns used in the processor, so a sequence of hexadecimal digits may represent a signed or even a floating-point value. This way, the negative number −4210 can be written as FFFF FFD6 in a 32-bit CPU register (in two's complement), as C228 0000 in a 32-bit FPU register or C045 0000 0000 0000 in a 64-bit FPU register (in the IEEE floating-point standard).

Hexadecimal exponential notation

Just as decimal numbers can be represented in exponential notation, so too can hexadecimal numbers. P notation uses the letter P (or p, for "power"), whereas E (or e) serves a similar purpose in decimal E notation. The number after the P is decimal and represents the binary exponent. Increasing the exponent by 1 multiplies by 2, not 16: 20p0 = 10p1 = 8p2 = 4p3 = 2p4 = 1p5. Usually, the number is normalized so that the hexadecimal digits start with 1. (zero is usually 0 with no P).

Example: 1.3DEp42 represents 1.3DE16 × 2.

P notation is required by the IEEE 754-2008 binary floating-point standard and can be used for floating-point literals in the C99 edition of the C programming language. Using the %a or %A conversion specifiers, this notation can be produced by implementations of the printf family of functions following the C99 specification and Single Unix Specification (IEEE Std 1003.1) POSIX standard.

Conversion

Binary conversion

Most computers manipulate binary data, but it is difficult for humans to work with a large number of digits for even a relatively small binary number. Although most humans are familiar with the base 10 system, it is much easier to map binary to hexadecimal than to decimal because each hexadecimal digit maps to a whole number of bits (410). This example converts 11112 to base ten. Since each position in a binary numeral can contain either a 1 or a 0, its value may be easily determined by its position from the right:

- 00012 = 110

- 00102 = 210

- 01002 = 410

- 10002 = 810

Therefore:

| 11112 | = 810 + 410 + 210 + 110 |

| = 1510 |

With little practice, mapping 11112 to F16 in one step becomes easy (see table in written representation). The advantage of using hexadecimal rather than decimal increases rapidly with the size of the number. When the number becomes large, conversion to decimal is very tedious. However, when mapping to hexadecimal, it is trivial to regard the binary string as 4-digit groups and map each to a single hexadecimal digit.

This example shows the conversion of a binary number to decimal, mapping each digit to the decimal value, and adding the results.

| (1001011100)2 | = 51210 + 6410 + 1610 + 810 + 410 |

| = 60410 |

Compare this to the conversion to hexadecimal, where each group of four digits can be considered independently and converted directly:

| (1001011100)2 | = | 0010 | 0101 | 11002 | ||

| = | 2 | 5 | C16 | |||

| = | 25C16 | |||||

The conversion from hexadecimal to binary is equally direct.

Other simple conversions

Although quaternary (base 4) is little used, it can easily be converted to and from hexadecimal or binary. Each hexadecimal digit corresponds to a pair of quaternary digits, and each quaternary digit corresponds to a pair of binary digits. In the above example 2 5 C16 = 02 11 304.

The octal (base 8) system can also be converted with relative ease, although not quite as trivially as with bases 2 and 4. Each octal digit corresponds to three binary digits, rather than four. Therefore, we can convert between octal and hexadecimal via an intermediate conversion to binary followed by regrouping the binary digits in groups of either three or four.

Division-remainder in source base

As with all bases there is a simple algorithm for converting a representation of a number to hexadecimal by doing integer division and remainder operations in the source base. In theory, this is possible from any base, but for most humans, only decimal and for most computers, only binary (which can be converted by far more efficient methods) can be easily handled with this method.

Let d be the number to represent in hexadecimal, and the series hihi−1...h2h1 be the hexadecimal digits representing the number.

- i ← 1

- hi ← d mod 16

- d ← (d − hi) / 16

- If d = 0 (return series hi) else increment i and go to step 2

"16" may be replaced with any other base that may be desired.

The following is a JavaScript implementation of the above algorithm for converting any number to a hexadecimal in String representation. Its purpose is to illustrate the above algorithm. To work with data seriously, however, it is much more advisable to work with bitwise operators.

function toHex(d) {

var r = d % 16;

if (d - r == 0) {

return toChar(r);

}

return toHex((d - r) / 16) + toChar(r);

}

function toChar(n) {

const alpha = "0123456789ABCDEF";

return alpha.charAt(n);

}

Conversion through addition and multiplication

It is also possible to make the conversion by assigning each place in the source base the hexadecimal representation of its place value — before carrying out multiplication and addition to get the final representation. For example, to convert the number B3AD to decimal, one can split the hexadecimal number into its digits: B (1110), 3 (310), A (1010) and D (1310), and then get the final result by multiplying each decimal representation by 16 (p being the corresponding hex digit position, counting from right to left, beginning with 0). In this case, we have that:

B3AD = (11 × 16) + (3 × 16) + (10 × 16) + (13 × 16)

which is 45997 in base 10.

Tools for conversion

Many computer systems provide a calculator utility capable of performing conversions between the various radices frequently including hexadecimal.

In Microsoft Windows, the Calculator utility can be set to Programmer mode, which allows conversions between radix 16 (hexadecimal), 10 (decimal), 8 (octal), and 2 (binary), the bases most commonly used by programmers. In Programmer Mode, the on-screen numeric keypad includes the hexadecimal digits A through F, which are active when "Hex" is selected. In hex mode, however, the Windows Calculator supports only integers.

Elementary arithmetic

Elementary operations such as division can be carried out indirectly through conversion to an alternate numeral system, such as the commonly used decimal system or the binary system where each hex digit corresponds to four binary digits.

Alternatively, one can also perform elementary operations directly within the hex system itself — by relying on its addition/multiplication tables and its corresponding standard algorithms such as long division and the traditional subtraction algorithm.

Real numbers

Rational numbers

As with other numeral systems, the hexadecimal system can be used to represent rational numbers, although repeating expansions are common since sixteen (1016) has only a single prime factor: two.

For any base, 0.1 (or "1/10") is always equivalent to one divided by the representation of that base value in its own number system. Thus, whether dividing one by two for binary or dividing one by sixteen for hexadecimal, both of these fractions are written as 0.1. Because the radix 16 is a perfect square (4), fractions expressed in hexadecimal have an odd period much more often than decimal ones, and there are no cyclic numbers (other than trivial single digits). Recurring digits are exhibited when the denominator in lowest terms has a prime factor not found in the radix; thus, when using hexadecimal notation, all fractions with denominators that are not a power of two result in an infinite string of recurring digits (such as thirds and fifths). This makes hexadecimal (and binary) less convenient than decimal for representing rational numbers since a larger proportion lies outside its range of finite representation.

All rational numbers finitely representable in hexadecimal are also finitely representable in decimal, duodecimal and sexagesimal: that is, any hexadecimal number with a finite number of digits also has a finite number of digits when expressed in those other bases. Conversely, only a fraction of those finitely representable in the latter bases are finitely representable in hexadecimal. For example, decimal 0.1 corresponds to the infinite recurring representation 0.19 in hexadecimal. However, hexadecimal is more efficient than duodecimal and sexagesimal for representing fractions with powers of two in the denominator. For example, 0.062510 (one-sixteenth) is equivalent to 0.116, 0.0912, and 0;3,4560.

| n | Decimal Prime factors of: base, b = 10: 2, 5; b − 1 = 9: 3; b + 1 = 11: 11 |

Hexadecimal Prime factors of: base, b = 1610 = 10: 2; b − 1 = 1510 = F: 3, 5; b + 1 = 1710 = 11: 11 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reciprocal | Prime factors | Positional representation (decimal) |

Positional representation (hexadecimal) |

Prime factors | Reciprocal | |

| 2 | 1/2 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 2 | 1/2 |

| 3 | 1/3 | 3 | 0.3333... = 0.3 | 0.5555... = 0.5 | 3 | 1/3 |

| 4 | 1/4 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.4 | 2 | 1/4 |

| 5 | 1/5 | 5 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 5 | 1/5 |

| 6 | 1/6 | 2, 3 | 0.16 | 0.2A | 2, 3 | 1/6 |

| 7 | 1/7 | 7 | 0.142857 | 0.249 | 7 | 1/7 |

| 8 | 1/8 | 2 | 0.125 | 0.2 | 2 | 1/8 |

| 9 | 1/9 | 3 | 0.1 | 0.1C7 | 3 | 1/9 |

| 10 | 1/10 | 2, 5 | 0.1 | 0.19 | 2, 5 | 1/A |

| 11 | 1/11 | 11 | 0.09 | 0.1745D | B | 1/B |

| 12 | 1/12 | 2, 3 | 0.083 | 0.15 | 2, 3 | 1/C |

| 13 | 1/13 | 13 | 0.076923 | 0.13B | D | 1/D |

| 14 | 1/14 | 2, 7 | 0.0714285 | 0.1249 | 2, 7 | 1/E |

| 15 | 1/15 | 3, 5 | 0.06 | 0.1 | 3, 5 | 1/F |

| 16 | 1/16 | 2 | 0.0625 | 0.1 | 2 | 1/10 |

| 17 | 1/17 | 17 | 0.0588235294117647 | 0.0F | 11 | 1/11 |

| 18 | 1/18 | 2, 3 | 0.05 | 0.0E38 | 2, 3 | 1/12 |

| 19 | 1/19 | 19 | 0.052631578947368421 | 0.0D79435E5 | 13 | 1/13 |

| 20 | 1/20 | 2, 5 | 0.05 | 0.0C | 2, 5 | 1/14 |

| 21 | 1/21 | 3, 7 | 0.047619 | 0.0C3 | 3, 7 | 1/15 |

| 22 | 1/22 | 2, 11 | 0.045 | 0.0BA2E8 | 2, B | 1/16 |

| 23 | 1/23 | 23 | 0.0434782608695652173913 | 0.0B21642C859 | 17 | 1/17 |

| 24 | 1/24 | 2, 3 | 0.0416 | 0.0A | 2, 3 | 1/18 |

| 25 | 1/25 | 5 | 0.04 | 0.0A3D7 | 5 | 1/19 |

| 26 | 1/26 | 2, 13 | 0.0384615 | 0.09D8 | 2, D | 1/1A |

| 27 | 1/27 | 3 | 0.037 | 0.097B425ED | 3 | 1/1B |

| 28 | 1/28 | 2, 7 | 0.03571428 | 0.0924 | 2, 7 | 1/1C |

| 29 | 1/29 | 29 | 0.0344827586206896551724137931 | 0.08D3DCB | 1D | 1/1D |

| 30 | 1/30 | 2, 3, 5 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 2, 3, 5 | 1/1E |

| 31 | 1/31 | 31 | 0.032258064516129 | 0.08421 | 1F | 1/1F |

| 32 | 1/32 | 2 | 0.03125 | 0.08 | 2 | 1/20 |

| 33 | 1/33 | 3, 11 | 0.03 | 0.07C1F | 3, B | 1/21 |

| 34 | 1/34 | 2, 17 | 0.02941176470588235 | 0.078 | 2, 11 | 1/22 |

| 35 | 1/35 | 5, 7 | 0.0285714 | 0.075 | 5, 7 | 1/23 |

| 36 | 1/36 | 2, 3 | 0.027 | 0.071C | 2, 3 | 1/24 |

| 37 | 1/37 | 37 | 0.027 | 0.06EB3E453 | 25 | 1/25 |

Irrational numbers

The table below gives the expansions of some common irrational numbers in decimal and hexadecimal.

| Number | Positional representation | |

|---|---|---|

| Decimal | Hexadecimal | |

| √2 (the length of the diagonal of a unit square) | 1.414213562373095048... | 1.6A09E667F3BCD... |

| √3 (the length of the diagonal of a unit cube) | 1.732050807568877293... | 1.BB67AE8584CAA... |

| √5 (the length of the diagonal of a 1×2 rectangle) | 2.236067977499789696... | 2.3C6EF372FE95... |

| φ (phi, the golden ratio = (1+√5)/2) | 1.618033988749894848... | 1.9E3779B97F4A... |

| π (pi, the ratio of circumference to diameter of a circle) | 3.141592653589793238462643 383279502884197169399375105... |

3.243F6A8885A308D313198A2E0 3707344A4093822299F31D008... |

| e (the base of the natural logarithm) | 2.718281828459045235... | 2.B7E151628AED2A6B... |

| τ (the Thue–Morse constant) | 0.412454033640107597... | 0.6996 9669 9669 6996... |

| γ (the limiting difference between the harmonic series and the natural logarithm) | 0.577215664901532860... | 0.93C467E37DB0C7A4D1B... |

Powers

Powers of two have very simple expansions in hexadecimal. The first sixteen powers of two are shown below.

| 2 | Value | Value (Decimal) |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 2 | 4 | 4 |

| 2 | 8 | 8 |

| 2 | 10hex | 16dec |

| 2 | 20hex | 32dec |

| 2 | 40hex | 64dec |

| 2 | 80hex | 128dec |

| 2 | 100hex | 256dec |

| 2 | 200hex | 512dec |

| 2 (2) | 400hex | 1024dec |

| 2 (2) | 800hex | 2048dec |

| 2 (2) | 1000hex | 4096dec |

| 2 (2) | 2000hex | 8192dec |

| 2 (2) | 4000hex | 16,384dec |

| 2 (2) | 8000hex | 32,768dec |

| 2 (2) | 10000hex | 65,536dec |

Cultural history

The traditional Chinese units of measurement were base-16. For example, one jīn (斤) in the old system equals sixteen taels. The suanpan (Chinese abacus) can be used to perform hexadecimal calculations such as additions and subtractions.

As with the duodecimal system, there have been occasional attempts to promote hexadecimal as the preferred numeral system. These attempts often propose specific pronunciation and symbols for the individual numerals. Some proposals unify standard measures so that they are multiples of 16. An early such proposal was put forward by John W. Nystrom in Project of a New System of Arithmetic, Weight, Measure and Coins: Proposed to be called the Tonal System, with Sixteen to the Base, published in 1862. Nystrom among other things suggested hexadecimal time, which subdivides a day by 16, so that there are 16 "hours" (or "10 tims", pronounced tontim) in a day.

The word hexadecimal is first recorded in 1952. It is macaronic in the sense that it combines Greek ἕξ (hex) "six" with Latinate -decimal. The all-Latin alternative sexadecimal (compare the word sexagesimal for base 60) is older, and sees at least occasional use from the late 19th century. It is still in use in the 1950s in Bendix documentation. Schwartzman (1994) argues that use of sexadecimal may have been avoided because of its suggestive abbreviation to sex. Many western languages since the 1960s have adopted terms equivalent in formation to hexadecimal (e.g. French hexadécimal, Italian esadecimale, Romanian hexazecimal, Serbian хексадецимални, etc.) but others have introduced terms which substitute native words for "sixteen" (e.g. Greek δεκαεξαδικός, Icelandic sextándakerfi, Russian шестнадцатеричной etc.)

Terminology and notation did not become settled until the end of the 1960s. In 1969, Donald Knuth argued that the etymologically correct term would be senidenary, or possibly sedenary, a Latinate term intended to convey "grouped by 16" modelled on binary, ternary, quaternary, etc. According to Knuth's argument, the correct terms for decimal and octal arithmetic would be denary and octonary, respectively. Alfred B. Taylor used senidenary in his mid-1800s work on alternative number bases, although he rejected base 16 because of its "incommodious number of digits".

The now-current notation using the letters A to F establishes itself as the de facto standard beginning in 1966, in the wake of the publication of the Fortran IV manual for IBM System/360, which (unlike earlier variants of Fortran) recognizes a standard for entering hexadecimal constants. As noted above, alternative notations were used by NEC (1960) and The Pacific Data Systems 1020 (1964). The standard adopted by IBM seems to have become widely adopted by 1968, when Bruce Alan Martin in his letter to the editor of the CACM complains that

With the ridiculous choice of letters A, B, C, D, E, F as hexadecimal number symbols adding to already troublesome problems of distinguishing octal (or hex) numbers from decimal numbers (or variable names), the time is overripe for reconsideration of our number symbols. This should have been done before poor choices gelled into a de facto standard!

Martin's argument was that use of numerals 0 to 9 in nondecimal numbers "imply to us a base-ten place-value scheme": "Why not use entirely new symbols (and names) for the seven or fifteen nonzero digits needed in octal or hex. Even use of the letters A through P would be an improvement, but entirely new symbols could reflect the binary nature of the system". He also argued that "re-using alphabetic letters for numerical digits represents a gigantic backward step from the invention of distinct, non-alphabetic glyphs for numerals sixteen centuries ago" (as Brahmi numerals, and later in a Hindu–Arabic numeral system), and that the recent ASCII standards (ASA X3.4-1963 and USAS X3.4-1968) "should have preserved six code table positions following the ten decimal digits -- rather than needlessly filling these with punctuation characters" (":;<=>?") that might have been placed elsewhere among the 128 available positions.

Base16 (transfer encoding)

Base16 (as a proper name without a space) can also refer to a binary to text encoding belonging to the same family as Base32, Base58, and Base64.

In this case, data is broken into 4-bit sequences, and each value (between 0 and 15 inclusively) is encoded using one of 16 symbols from the ASCII character set. Although any 16 symbols from the ASCII character set can be used, in practice, the ASCII digits "0"–"9" and the letters "A"–"F" (or the lowercase "a"–"f") are always chosen in order to align with standard written notation for hexadecimal numbers.

There are several advantages of Base16 encoding:

- Most programming languages already have facilities to parse ASCII-encoded hexadecimal

- Being exactly half a byte, 4-bits is easier to process than the 5 or 6 bits of Base32 and Base64 respectively

- The symbols 0–9 and A–F are universal in hexadecimal notation, so it is easily understood at a glance without needing to rely on a symbol lookup table.

- Many CPU architectures have dedicated instructions that allow access to a half-byte (otherwise known as a "nibble"), making it more efficient in hardware than Base32 and Base64

The main disadvantages of Base16 encoding are:

- Space efficiency is only 50%, since each 4-bit value from the original data will be encoded as an 8-bit byte. In contrast, Base32 and Base64 encodings have a space efficiency of 63% and 75% respectively.

- Possible added complexity of having to accept both uppercase and lowercase letters

Support for Base16 encoding is ubiquitous in modern computing. It is the basis for the W3C standard for URL percent encoding, where a character is replaced with a percent sign "%" and its Base16-encoded form. Most modern programming languages directly include support for formatting and parsing Base16-encoded numbers.

See also

- Base32, Base64 (content encoding schemes)

- Hexadecimal time

- IBM hexadecimal floating-point

- Hex editor

- Hex dump

- Bailey–Borwein–Plouffe formula (BBP)

- Hexspeak

- P notation

References

- "The hexadecimal system". Ionos Digital Guide. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-26.

- Knuth, Donald Ervin (1986). The TeXbook. Duane Bibby. Reading, Mass. ISBN 0-201-13447-0. OCLC 12973034. Archived from the original on 2022-01-16. Retrieved 2022-03-15.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - The string

"\x1B[0m\x1B[25;1H"specifies the character sequence Esc [ 0 m Esc [ 2 5; 1 H. These are the escape sequences used on an ANSI terminal that reset the character set and color, and then move the cursor to line 25. - "The Unicode Standard, Version 7" (PDF). Unicode. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2018-10-28.

- "Modula-2 – Vocabulary and representation". Modula −2. Archived from the original on 2015-12-13. Retrieved 2015-11-01.

- "An Introduction to VHDL Data Types". FPGA Tutorial. 2020-05-10. Archived from the original on 2020-08-23. Retrieved 2020-08-21.

- "*read-base* variable in Common Lisp". CLHS. Archived from the original on 2016-02-03. Retrieved 2015-01-10.

- "*print-base* variable in Common Lisp". CLHS. Archived from the original on 2014-12-26. Retrieved 2015-01-10.

- MSX is Coming — Part 2: Inside MSX Archived 2010-11-24 at the Wayback Machine Compute!, issue 56, January 1985, p. 52

- BBC BASIC programs are not fully portable to Microsoft BASIC (without modification) since the latter takes

&to prefix octal values. (Microsoft BASIC primarily uses&Oto prefix octal, and it uses&Hto prefix hexadecimal, but the ampersand alone yields a default interpretation as an octal prefix. - "Hexadecimal web colors explained". Archived from the original on 2006-04-22. Retrieved 2006-01-11.

- "ISO-8859-1 (ISO Latin 1) Character Encoding". www.ic.unicamp.br. Archived from the original on 2019-06-29. Retrieved 2019-06-26.

- ^ Savard, John J. G. (2018) . "Computer Arithmetic". quadibloc. The Early Days of Hexadecimal. Archived from the original on 2018-07-16. Retrieved 2018-07-16.

- "2.1.3 Sexadecimal notation". G15D Programmer's Reference Manual (PDF). Los Angeles, CA, US: Bendix Computer, Division of Bendix Aviation Corporation. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-06-01. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

This base is used because a group of four bits can represent any one of sixteen different numbers (zero to fifteen). By assigning a symbol to each of these combinations, we arrive at a notation called sexadecimal (usually "hex" in conversation because nobody wants to abbreviate "sex"). The symbols in the sexadecimal language are the ten decimal digits and on the G-15 typewriter, the letters "u", "v", "w", "x", "y", and "z". These are arbitrary markings; other computers may use different alphabet characters for these last six digits.

- Gill, S.; Neagher, R. E.; Muller, D. E.; Nash, J. P.; Robertson, J. E.; Shapin, T.; Whesler, D. J. (1956-09-01). Nash, J. P. (ed.). "ILLIAC Programming – A Guide to the Preparation of Problems For Solution by the University of Illinois Digital Computer" (PDF). bitsavers.org (Fourth printing. Revised and corrected ed.). Urbana, Illinois, US: Digital Computer Laboratory, Graduate College, University of Illinois. pp. 3–2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-05-31. Retrieved 2014-12-18.

- Royal Precision Electronic Computer LGP – 30 Programming Manual. Port Chester, New York: Royal McBee Corporation. April 1957. Archived from the original on 2017-05-31. Retrieved 2017-05-31. (NB. This somewhat odd sequence was from the next six sequential numeric keyboard codes in the LGP-30's 6-bit character code.)

- Manthey, Steffen; Leibrandt, Klaus (2002-07-02). "Die PERM und ALGOL" (PDF) (in German). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-10-03. Retrieved 2018-05-19.

- NEC Parametron Digital Computer Type NEAC-1103 (PDF). Tokyo, Japan: Nippon Electric Company Ltd. 1960. Cat. No. 3405-C. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-05-31. Retrieved 2017-05-31.

- ^ Martin, Bruce Alan (October 1968). "Letters to the editor: On binary notation". Communications of the ACM. 11 (10). Associated Universities Inc.: 658. doi:10.1145/364096.364107. S2CID 28248410.

- ^ Whitaker, Ronald O. (January 1972). Written at Indianapolis, Indiana, US. "More on man/machine" (PDF). Letters. Datamation. Vol. 18, no. 1. Barrington, Illinois, US: Technical Publishing Company. p. 103. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-12-05. Retrieved 2022-12-24. (1 page)

- ^ Whitaker, Ronald O. (1976-08-10) . "Combined display and range selector for use with digital instruments employing the binary numbering system" (PDF). Indianapolis, Indiana, US. US Patent 3974444A. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2022-12-24. (7 pages)

- "SN5446A, '47A, '48, SN54LS47, 'LS48, 'LS49, SN7446A, '47A, '48, SN74LS47, 'LS48, 'LS49 BCD-to-Seven-Segment Decoders/Drivers". Dallas, Texas, US: Texas Instruments Incorporated. March 1988 . SDLS111. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-10-20. Retrieved 2021-09-15. (29 pages)

- ^ Magnuson, Robert A. (January 1968). "A hexadecimal pronunciation guide". Datamation. Vol. 14, no. 1. p. 45.

- ^ Rogers, S.R. (2007). "Hexadecimal number words". Intuitor. Archived from the original on 2019-09-17. Retrieved 2019-08-26.

- Babb, Tim (2015). "How to pronounce hexadecimal". Bzarg. Archived from the original on 2020-11-11. Retrieved 2021-01-01.

- Clarke, Arthur; Pohl, Frederik (2008). The Last Theorem. Ballantine. p. 91. ISBN 978-0007289981.

- "ISO/IEC 9899:1999 – Programming languages – C". ISO. Iso.org. 2011-12-08. Archived from the original on 2016-10-10. Retrieved 2014-04-08.

- "Rationale for International Standard – Programming Languages – C" (PDF). Open Standards. 5.10. April 2003. pp. 52, 153–154, 159. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-06-06. Retrieved 2010-10-17.

- The IEEE and The Open Group (2013) . "dprintf, fprintf, printf, snprintf, sprintf – print formatted output". The Open Group Base Specifications (Issue 7, IEEE Std 1003.1, 2013 ed.). Archived from the original on 2016-06-21. Retrieved 2016-06-21.

- ^ Mano, M. Morris; Ciletti, Michael D. (2013). Digital Design – With an Introduction to the Verilog HDL (Fifth ed.). Pearson Education. pp. 6, 8–10. ISBN 978-0-13-277420-8.

- "算盤 Hexadecimal Addition & Subtraction on a Chinese Abacus". totton.idirect.com. Archived from the original on 2019-07-06. Retrieved 2019-06-26.

- "Base 4^2 Hexadecimal Symbol Proposal". Hauptmech. Archived from the original on 2021-10-20. Retrieved 2008-09-04.

- "Intuitor Hex Headquarters". Intuitor. Archived from the original on 2010-09-04. Retrieved 2018-10-28.

- Niemietz, Ricardo Cancho (2003-10-21). "A proposal for addition of the six Hexadecimal digits (A-F) to Unicode" (PDF). ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2. Retrieved 2024-06-25.

- Nystrom, John William (1862). Project of a New System of Arithmetic, Weight, Measure and Coins: Proposed to be called the Tonal System, with Sixteen to the Base. Philadelphia: Lippincott.

- Nystrom (1862), p. 33: "In expressing time, angle of a circle, or points on the compass, the unit tim should be noted as integer, and parts thereof as tonal fractions, as 5·86 tims is five times and metonby ."

- C. E. Fröberg, Hexadecimal Conversion Tables, Lund (1952).

- The Century Dictionary of 1895 has sexadecimal in the more general sense of "relating to sixteen". An early explicit use of sexadecimal in the sense of "using base 16" is found also in 1895, in the Journal of the American Geographical Society of New York, vols. 27–28, p. 197.

- Schwartzman, Steven (1994). The Words of Mathematics: An etymological dictionary of mathematical terms used in English. The Mathematical Association of America. p. 105. ISBN 0-88385-511-9. s.v. hexadecimal

- Knuth, Donald. (1969). The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 2. ISBN 0-201-03802-1. (Chapter 17.)

- Alfred B. Taylor, Report on Weights and Measures, Pharmaceutical Association, 8th Annual Session, Boston, 15 September 1859. See pages and 33 and 41.

- Alfred B. Taylor, "Octonary numeration and its application to a system of weights and measures", Proc Amer. Phil. Soc. Vol XXIV Archived 2016-06-24 at the Wayback Machine, Philadelphia, 1887; pages 296–366. See pages 317 and 322.

- IBM System/360 FORTRAN IV Language Archived 2021-05-19 at the Wayback Machine (1966), p. 13.