In mathematics and statistics, the arithmetic mean ( /ˌærɪθˈmɛtɪk/ arr-ith-MET-ik), arithmetic average, or just the mean or average (when the context is clear) is the sum of a collection of numbers divided by the count of numbers in the collection. The collection is often a set of results from an experiment, an observational study, or a survey. The term "arithmetic mean" is preferred in some mathematics and statistics contexts because it helps distinguish it from other types of means, such as geometric and harmonic.

In addition to mathematics and statistics, the arithmetic mean is frequently used in economics, anthropology, history, and almost every academic field to some extent. For example, per capita income is the arithmetic average income of a nation's population.

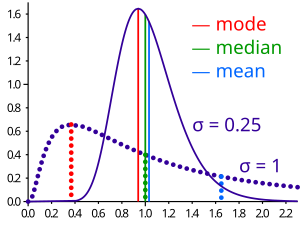

While the arithmetic mean is often used to report central tendencies, it is not a robust statistic: it is greatly influenced by outliers (values much larger or smaller than most others). For skewed distributions, such as the distribution of income for which a few people's incomes are substantially higher than most people's, the arithmetic mean may not coincide with one's notion of "middle". In that case, robust statistics, such as the median, may provide a better description of central tendency.

Definition

The arithmetic mean of a set of observed data is equal to the sum of the numerical values of each observation, divided by the total number of observations. Symbolically, for a data set consisting of the values , the arithmetic mean is defined by the formula:

(For an explanation of the summation operator, see summation.)

In simpler terms, the formula for the arithmetic mean is:

For example, if the monthly salaries of employees are , then the arithmetic mean is:

If the data set is a statistical population (i.e., consists of every possible observation and not just a subset of them), then the mean of that population is called the population mean and denoted by the Greek letter . If the data set is a statistical sample (a subset of the population), it is called the sample mean (which for a data set is denoted as ).

The arithmetic mean can be similarly defined for vectors in multiple dimensions, not only scalar values; this is often referred to as a centroid. More generally, because the arithmetic mean is a convex combination (meaning its coefficients sum to ), it can be defined on a convex space, not only a vector space.

History

The statistician Churchill Eisenhart, senior researcher fellow at the U. S. National Bureau of Standards, traced the history of the arithmetic mean in detail. In the modern age it started to be used as a way of combining various observations that should be identical, but were not such as estimates of the direction of magnetic north. In 1635 the mathematician Henry Gellibrand described as “meane” the midpoint of a lowest and highest number, not quite the arithmetic mean. In 1668, a person known as “DB” was quoted in the Transactions of the Royal Society describing “taking the mean” of five values:

In this Table, he notes the greatest difference to be 14 minutes; and so taking the mean for the true Variation, he concludes it then and there to be just 1. deg. 27. min.

— D.B. p. 726

Motivating properties

The arithmetic mean has several properties that make it interesting, especially as a measure of central tendency. These include:

- If numbers have mean , then . Since is the distance from a given number to the mean, one way to interpret this property is by saying that the numbers to the left of the mean are balanced by the numbers to the right. The mean is the only number for which the residuals (deviations from the estimate) sum to zero. This can also be interpreted as saying that the mean is translationally invariant in the sense that for any real number , .

- If it is required to use a single number as a "typical" value for a set of known numbers , then the arithmetic mean of the numbers does this best since it minimizes the sum of squared deviations from the typical value: the sum of . The sample mean is also the best single predictor because it has the lowest root mean squared error. If the arithmetic mean of a population of numbers is desired, then the estimate of it that is unbiased is the arithmetic mean of a sample drawn from the population.

- The arithmetic mean is independent of scale of the units of measurement, in the sense that So, for example, calculating a mean of liters and then converting to gallons is the same as converting to gallons first and then calculating the mean. This is also called first order homogeneity.

Additional properties

- The arithmetic mean of a sample is always between the largest and smallest values in that sample.

- The arithmetic mean of any amount of equal-sized number groups together is the arithmetic mean of the arithmetic means of each group.

Contrast with median

Main article: MedianThe arithmetic mean may be contrasted with the median. The median is defined such that no more than half the values are larger, and no more than half are smaller than it. If elements in the data increase arithmetically when placed in some order, then the median and arithmetic average are equal. For example, consider the data sample . The mean is , as is the median. However, when we consider a sample that cannot be arranged to increase arithmetically, such as , the median and arithmetic average can differ significantly. In this case, the arithmetic average is , while the median is . The average value can vary considerably from most values in the sample and can be larger or smaller than most.

There are applications of this phenomenon in many fields. For example, since the 1980s, the median income in the United States has increased more slowly than the arithmetic average of income.

Generalizations

Weighted average

Main article: Weighted averageA weighted average, or weighted mean, is an average in which some data points count more heavily than others in that they are given more weight in the calculation. For example, the arithmetic mean of and is , or equivalently . In contrast, a weighted mean in which the first number receives, for example, twice as much weight as the second (perhaps because it is assumed to appear twice as often in the general population from which these numbers were sampled) would be calculated as . Here the weights, which necessarily sum to one, are and , the former being twice the latter. The arithmetic mean (sometimes called the "unweighted average" or "equally weighted average") can be interpreted as a special case of a weighted average in which all weights are equal to the same number ( in the above example and in a situation with numbers being averaged).

Continuous probability distributions

If a numerical property, and any sample of data from it, can take on any value from a continuous range instead of, for example, just integers, then the probability of a number falling into some range of possible values can be described by integrating a continuous probability distribution across this range, even when the naive probability for a sample number taking one certain value from infinitely many is zero. In this context, the analog of a weighted average, in which there are infinitely many possibilities for the precise value of the variable in each range, is called the mean of the probability distribution. The most widely encountered probability distribution is called the normal distribution; it has the property that all measures of its central tendency, including not just the mean but also the median mentioned above and the mode (the three Ms), are equal. This equality does not hold for other probability distributions, as illustrated for the log-normal distribution here.

Angles

Main article: Mean of circular quantitiesParticular care is needed when using cyclic data, such as phases or angles. Taking the arithmetic mean of 1° and 359° yields a result of 180°. This is incorrect for two reasons:

- Firstly, angle measurements are only defined up to an additive constant of 360° ( or , if measuring in radians). Thus, these could easily be called 1° and -1°, or 361° and 719°, since each one of them produces a different average.

- Secondly, in this situation, 0° (or 360°) is geometrically a better average value: there is lower dispersion about it (the points are both 1° from it and 179° from 180°, the putative average).

In general application, such an oversight will lead to the average value artificially moving towards the middle of the numerical range. A solution to this problem is to use the optimization formulation (that is, define the mean as the central point: the point about which one has the lowest dispersion) and redefine the difference as a modular distance (i.e., the distance on the circle: so the modular distance between 1° and 359° is 2°, not 358°).

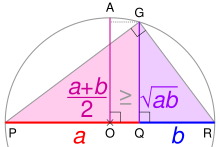

PR is the diameter of a circle centered on O; its radius AO is the arithmetic mean of a and b. Using the geometric mean theorem, triangle PGR's altitude GQ is the geometric mean. For any ratio a:b, AO ≥ GQ.

Symbols and encoding

The arithmetic mean is often denoted by a bar (vinculum or macron), as in .

Some software (text processors, web browsers) may not display the "x̄" symbol correctly. For example, the HTML symbol "x̄" combines two codes — the base letter "x" plus a code for the line above ( ̄ or ¯).

In some document formats (such as PDF), the symbol may be replaced by a "¢" (cent) symbol when copied to a text processor such as Microsoft Word.

See also

- Fréchet mean

- Generalized mean

- Inequality of arithmetic and geometric means

- Sample mean and covariance

- Standard deviation

- Standard error of the mean

- Summary statistics

Notes

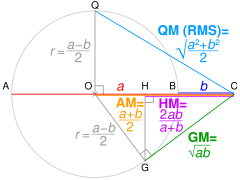

- If AC = a and BC = b. OC = AM of a and b, and radius r = QO = OG.

Using Pythagoras' theorem, QC² = QO² + OC² ∴ QC = √QO² + OC² = QM.

Using Pythagoras' theorem, OC² = OG² + GC² ∴ GC = √OC² − OG² = GM.

Using similar triangles, HC/GC = GC/OC ∴ HC = GC²/OC = HM.

References

- Jacobs, Harold R. (1994). Mathematics: A Human Endeavor (Third ed.). W. H. Freeman. p. 547. ISBN 0-7167-2426-X.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Arithmetic Mean". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- Eisenhart, Churchill (24 August 1971). "The Development of the Concept of the Best Mean of a Set of Measurements from Antiquity to the Present Day" (PDF). Presidential Address, 131st Annual Meeting of the American Statistical Association, Colorado State University. pp. 68–69.

- ^ Medhi, Jyotiprasad (1992). Statistical Methods: An Introductory Text. New Age International. pp. 53–58. ISBN 9788122404197.

- Krugman, Paul (4 June 2014) . "The Rich, the Right, and the Facts: Deconstructing the Income Distribution Debate". The American Prospect.

- "Mean | mathematics". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- Thinkmap Visual Thesaurus (30 June 2010). "The Three M's of Statistics: Mode, Median, Mean June 30, 2010". www.visualthesaurus.com. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- "Notes on Unicode for Stat Symbols". www.personal.psu.edu. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

Further reading

- Huff, Darrell (1993). How to Lie with Statistics. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-31072-6.

External links

- Calculations and comparisons between arithmetic mean and geometric mean of two numbers

- Calculate the arithmetic mean of a series of numbers on fxSolver

, the arithmetic mean is defined by the formula:

, the arithmetic mean is defined by the formula:

employees are

employees are  , then the arithmetic mean is:

, then the arithmetic mean is:

. If the data set is a

. If the data set is a  is denoted as

is denoted as  ).

).

), it can be defined on a

), it can be defined on a  have mean

have mean  , then

, then  . Since

. Since  is the distance from a given number to the mean, one way to interpret this property is by saying that the numbers to the left of the mean are balanced by the numbers to the right. The mean is the only number for which the

is the distance from a given number to the mean, one way to interpret this property is by saying that the numbers to the left of the mean are balanced by the numbers to the right. The mean is the only number for which the  ,

,  .

. . The sample mean is also the best single predictor because it has the lowest

. The sample mean is also the best single predictor because it has the lowest  So, for example, calculating a mean of liters and then converting to gallons is the same as converting to gallons first and then calculating the mean. This is also called

So, for example, calculating a mean of liters and then converting to gallons is the same as converting to gallons first and then calculating the mean. This is also called  . The mean is

. The mean is  , as is the median. However, when we consider a sample that cannot be arranged to increase arithmetically, such as

, as is the median. However, when we consider a sample that cannot be arranged to increase arithmetically, such as  , the median and arithmetic average can differ significantly. In this case, the arithmetic average is

, the median and arithmetic average can differ significantly. In this case, the arithmetic average is  , while the median is

, while the median is  . The average value can vary considerably from most values in the sample and can be larger or smaller than most.

. The average value can vary considerably from most values in the sample and can be larger or smaller than most.

and

and  is

is  , or equivalently

, or equivalently  . In contrast, a weighted mean in which the first number receives, for example, twice as much weight as the second (perhaps because it is assumed to appear twice as often in the general population from which these numbers were sampled) would be calculated as

. In contrast, a weighted mean in which the first number receives, for example, twice as much weight as the second (perhaps because it is assumed to appear twice as often in the general population from which these numbers were sampled) would be calculated as  . Here the weights, which necessarily sum to one, are

. Here the weights, which necessarily sum to one, are  and

and  , the former being twice the latter. The arithmetic mean (sometimes called the "unweighted average" or "equally weighted average") can be interpreted as a special case of a weighted average in which all weights are equal to the same number (

, the former being twice the latter. The arithmetic mean (sometimes called the "unweighted average" or "equally weighted average") can be interpreted as a special case of a weighted average in which all weights are equal to the same number ( in the above example and

in the above example and  in a situation with

in a situation with  numbers being averaged).

numbers being averaged).

or

or  , if measuring in

, if measuring in