In quantum field theory, and specifically quantum electrodynamics, vacuum polarization describes a process in which a background electromagnetic field produces virtual electron–positron pairs that change the distribution of charges and currents that generated the original electromagnetic field. It is also sometimes referred to as the self-energy of the gauge boson (photon).

After developments in radar equipment for World War II resulted in higher accuracy for measuring the energy levels of the hydrogen atom, Isidor Rabi made measurements of the Lamb shift and the anomalous magnetic dipole moment of the electron. These effects corresponded to the deviation from the value −2 for the spectroscopic electron g-factor that are predicted by the Dirac equation. Later, Hans Bethe theoretically calculated those shifts in the hydrogen energy levels due to vacuum polarization on his return train ride from the Shelter Island Conference to Cornell.

The effects of vacuum polarization have been routinely observed experimentally since then as very well-understood background effects. Vacuum polarization, referred to below as the one loop contribution, occurs with leptons (electron–positron pairs) or quarks. The former (leptons) was first observed in 1940s but also more recently observed in 1997 using the TRISTAN particle accelerator in Japan, the latter (quarks) was observed along with multiple quark–gluon loop contributions from the early 1970s to mid-1990s using the VEPP-2M particle accelerator at the Budker Institute of Nuclear Physics in Siberia, Russia and many other accelerator laboratories worldwide.

History

Vacuum polarization was first discussed in papers by Paul Dirac and Werner Heisenberg in 1934. Effects of vacuum polarization were calculated to first order in the coupling constant by Robert Serber and Edwin Albrecht Uehling in 1935.

Explanation

According to quantum field theory, the vacuum between interacting particles is not simply empty space. Rather, it contains short-lived virtual particle–antiparticle pairs (leptons or quarks and gluons). These short-lived pairs are called vacuum bubbles. It can be shown that they have no measurable impact on any process.

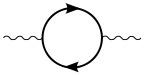

Virtual particle–antiparticle pairs can also occur as a photon propagates. In this case, the effect on other processes is measurable. The one-loop contribution of a fermion–antifermion pair to the vacuum polarization is represented by the following diagram:

These particle–antiparticle pairs carry various kinds of charges, such as color charge if they are subject to quantum chromodynamics such as quarks or gluons, or the more familiar electromagnetic charge if they are electrically charged leptons or quarks, the most familiar charged lepton being the electron and since it is the lightest in mass, the most numerous due to the energy–time uncertainty principle as mentioned above; e.g., virtual electron–positron pairs. Such charged pairs act as an electric dipole. In the presence of an electric field, e.g., the electromagnetic field around an electron, these particle–antiparticle pairs reposition themselves, thus partially counteracting the field (a partial screening effect, a dielectric effect). The field therefore will be weaker than would be expected if the vacuum were completely empty. This reorientation of the short-lived particle–antiparticle pairs is referred to as vacuum polarization.

Electric and magnetic fields

Extremely strong electric and magnetic fields cause an excitation of electron–positron pairs. Maxwell's equations are the classical limit of the quantum electrodynamics which cannot be described by any classical theory. A point charge must be modified at extremely small distances less than the reduced Compton wavelength (). To lowest order in the fine-structure constant, , the QED result for the electrostatic potential of a point charge is:

This can be understood as a screening of a point charge by a medium with a dielectric permittivity, which is why the term vacuum polarization is used. When observed from distances much greater than , the charge is renormalized to the finite value . See also the Uehling potential.

The effects of vacuum polarization become significant when the external field approaches the Schwinger limit, which is:

These effects break the linearity of Maxwell's equations and therefore break the superposition principle. The QED result for slowly varying fields can be written in non-linear relations for the vacuum. To lowest order , virtual pair production generates a vacuum polarization and magnetization given by:

As of 2019, this polarization and magnetization has not been directly measured.

Vacuum polarization tensor

The vacuum polarization is quantified by the vacuum polarization tensor Π(p) which describes the dielectric effect as a function of the four-momentum p carried by the photon. Thus the vacuum polarization depends on the momentum transfer, or in other words, the electric constant is scale dependent. In particular, for electromagnetism we can write the fine-structure constant as an effective momentum-transfer-dependent quantity; to first order in the corrections, we have where Π(p) = (p g − pp) Π(p) and the subscript 2 denotes the leading order-e correction. The tensor structure of Π(p) is fixed by the Ward identity.

Note

Vacuum polarization affecting spin interactions has also been reported based on experimental data and also treated theoretically in quantum chromodynamics, as for example in considering the hadron spin structure.

See also

- Polarization density

- Infraparticle

- Renormalization

- Virtual particles

- QED vacuum

- QCD vacuum

- Schwinger limit

- Schwinger effect

- Uehling potential

- Vacuum birefringence

- Nonoblique correction

Remarks

- They yield a phase factor to the vacuum to vacuum transition amplitude.

Notes

- Bethe 1947

- Levine 1997

- Brown & Worstell 1996, pp. 3237–3249

- Dirac 1934

- Heisenberg 1934

- Serber 1935

- Uehling 1935

- Gell-Mann & Low 1954

- Greiner & Reinhardt 1996, Chapter 8.

- Weinberg 2002, Chapters 10–11

- Berestetskii, Lifshitz & Pitaevskii 1980, Section 114.

References

- Berestetskii, V. B.; Lifshitz, E. M.; Pitaevskii, L. (1980). "Section 114". Quantum Electrodynamics. Course of Theoretical Physics. Vol. 4 (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0750633710.

- Bethe, H. A. (1947). "The Electromagnetic Shift of Energy Levels". Phys. Rev. 72 (4) (published August 1947): 339–341. Bibcode:1947PhRv...72..339B. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.72.339. ISSN 0031-899X. Zbl 0030.42406. Wikidata Q21709244.

- Brown, Douglas H.; Worstell, William A (1996). "The Lowest Order Hadronic Contribution to the Muon g − 2 Value with Systematic Error Correlations". Physical Review D. 54 (5) (published 1 September 1996): 3237–3249. arXiv:hep-ph/9607319. Bibcode:1996PhRvD..54.3237B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.54.3237. ISSN 1550-7998. PMID 10020994. S2CID 37689024. Wikidata Q27349045.

- Dirac, P. A. M. (1934). "Discussion of the infinite distribution of electrons in the theory of the positron". Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 30 (2) (published April 1934): 150–163. Bibcode:1934PCPS...30..150D. doi:10.1017/S030500410001656X. ISSN 0305-0041. JFM 60.0790.02. Zbl 0009.13704. Wikidata Q60895121.

- Gell-Mann, M.; Low, F. E. (1954). "Quantum Electrodynamics at Small Distances". Phys. Rev. 95 (5) (published September 1954): 1300–1312. Bibcode:1954PhRv...95.1300G. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.95.1300. ISSN 0031-899X. Zbl 0057.21401. Wikidata Q21709149.

- Greiner, W.; Reinhardt, J. (1996). Field Quantization. Springer Publishing. ISBN 978-3-540-59179-5.

- Heisenberg, W. (1934). "Bemerkungen zur Diracschen Theorie des Positrons". Zeitschrift für Physik (in German). 90 (3–4) (published March 1934): 209–231. Bibcode:1934ZPhy...90..209H. doi:10.1007/BF01333516. ISSN 0044-3328. S2CID 186232913. Wikidata Q56068099.

- Levine, I.; et al. (TOPAZ Collaboration) (1997). "Measurement of the Electromagnetic Coupling at Large Momentum Transfer". Physical Review Letters. 78 (3) (published January 1997): 424–427. Bibcode:1997PhRvL..78..424L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.78.424. ISSN 0031-9007. Wikidata Q21698757.

- Serber, R. (1935). "Linear Modifications in the Maxwell Field Equations". Phys. Rev. 48 (1) (published 1 July 1935): 49–54. Bibcode:1935PhRv...48...49S. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.48.49. ISSN 0031-899X. JFM 61.1250.03. Zbl 0012.13604. Wikidata Q60895120.

- Uehling, E. A. (1935). "Polarization Effects in the Positron Theory". Phys. Rev. 48 (1) (published 1 July 1935): 55–63. Bibcode:1935PhRv...48...55U. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.48.55. ISSN 0031-899X. Zbl 0012.13605. Wikidata Q60895119.

- Weinberg, S. (2002). Foundations. The Quantum Theory of Fields. Vol. I. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-55001-7.

Further reading

- For a derivation of the vacuum polarization in QED, see section 7.5 of M.E. Peskin and D.V. Schroeder, An Introduction to Quantum Field Theory, Addison-Wesley, 1995.

| Quantum electrodynamics | |

|---|---|

| Formalism | |

| Particles | |

| Concepts | |

| Processes | |

| See also: | |

(

( ). To lowest order in the

). To lowest order in the  , the QED result for the electrostatic potential of a point charge is:

, the QED result for the electrostatic potential of a point charge is:

. See also the

. See also the

where Π(p) = (p g − pp) Π(p) and the subscript 2 denotes the leading order-e correction. The tensor structure of Π(p) is fixed by the

where Π(p) = (p g − pp) Π(p) and the subscript 2 denotes the leading order-e correction. The tensor structure of Π(p) is fixed by the