Concealed carry, or carrying a concealed weapon (CCW), is the practice of carrying a weapon (such as a handgun) in public in a concealed manner, either on one's person or in close proximity. CCW is often practiced as a means of self-defense. Following the Supreme Court's NYSRPA v. Bruen (2022) decision, all states in the United States were required to allow for concealed carry of a handgun either permitlessly or with a permit, although the difficulty in obtaining a permit varies per jurisdiction.

There is conflicting evidence regarding the effect that concealed carry has on crime rates. A 2020 review by the RAND Corporation concluded there is supportive evidence that shall-issue concealed carry laws, which require states to issue permits to applicants once certain requirements are met, are associated with increased firearm homicides and total homicides. Earlier studies by RAND found that shall-issue concealed carry laws may increase violent crime overall, while there was inconclusive evidence for the effect of shall-issue laws on all individual types of violent crime. A 2004 literature review by the National Academy of Sciences concluded that there is no link between the existence of laws that allow concealed carry and crime rates.

History

Main article: History of concealed carry in the United States

The Second Amendment to the United States Constitution guarantees the right to "keep and bear arms". Concealed weapons bans were passed in Kentucky and Louisiana in 1813. (In those days open carry of weapons for self-defense was considered acceptable; concealed carry was denounced as the practice of criminals.) By 1859, Indiana, Tennessee, Virginia, Alabama, and Ohio had followed suit. By the end of the nineteenth century, similar laws were passed in places such as Texas, Florida, and Oklahoma, which protected some gun rights in their state constitutions. Before the mid-1900s, most U.S. states had passed concealed carry laws rather than banning weapons completely. Until the late 1990s, many Southern states were either "No-Issue" or "Restrictive May-Issue". Since then, these states have largely enacted "Shall-Issue" licensing laws, with more than half of the states legalizing "constitutional carry" (unrestricted concealed carry) and the remaining "May-issue" licensing laws being abolished in 2022 by the U.S. Supreme Court.

State laws

Permitting policies

Further information: Gun laws in the United States by state- Unrestricted jurisdiction: one in which a permit is not required to carry a concealed handgun. All states in this category allow any non-prohibited person to carry regardless of the state of residency.

- Permit requirement jurisdiction: one in which a permit is required to carry a concealed handgun.

Historically, some states were considered "may-issue" jurisdictions where an applicant was required to provide a proper cause or need to be issued a permit to carry a concealed weapon. However, on June 23, 2022, these laws were found unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen.

Regulations differ widely by state, with twenty-seven of the fifty states either currently maintaining a constitutional carry policy or implementing it in the near future.

The Federal Gun-Free School Zones Act limits where an unlicensed person may carry; carry of a weapon, openly or concealed, within 1,000 feet (300 m) of a school zone is prohibited, with exceptions granted in the federal law to holders of valid state-issued weapons permits (state laws may reassert the illegality of school zone carry by license holders), and under LEOSA to current and honorably retired law enforcement officers (regardless of permit, usually overriding state law).

When in contact with an officer, some states require individuals to inform that officer that they are carrying a handgun.

Not all weapons that fall under CCW laws are lethal. For example, in Florida, carrying pepper spray in more than a specified volume (2 oz.) of chemical requires a CCW permit, whereas everyone may legally carry a smaller, “self-defense chemical spray” device hidden on their person without a CCW permit. As of 2021 there have been 21.52 million concealed weapon permits issued in the United States.

| Jurisdiction | Unrestricted | Permit Required | Illegal | Non-Resident Permits Available |

Permit Recognition | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | Yes | 18 | ||||

| Alaska | Yes

21+ only |

21 | ||||

| American Samoa | No | N/A | ||||

| Arizona | Yes

21+ only |

21 | ||||

| Arkansas | Yes | 18 | ||||

| California | No | 21 | ||||

| Colorado | Partial (33 states)

Resident permits only 21+ only |

21 | ||||

| Connecticut | No | 21 | ||||

| Delaware | Partial (21 states) | 18 | ||||

| District of Columbia | Briefly from July 26, 2014 – July 29, 2014; see below for details | No | 21 | |||

| Florida | Yes

Resident permits only 21+ only; 18+ if military |

21 | ||||

| Georgia | Yes | 21 (18 with out of state carry permit) | ||||

| Guam | No | 21 | ||||

| Hawaii | No | 21 | ||||

| Idaho | For concealed carry by non-military permanent resident aliens | Yes | 18 | |||

| Illinois | Unloaded and enclosed in a case, firearm carrying box, shipping box, or other container | Only for residents of Arkansas, Idaho, Mississippi, Nevada, Texas and Virginia. | Vehicle carry only | 21 | ||

| Indiana | Yes

Includes foreign countries |

18 | ||||

| Iowa | Yes | 21 | ||||

| Kansas | For concealed carry between ages 18–20 | Yes | 18 with permit | |||

| Kentucky | Yes | 21 | ||||

| Louisiana | Partial (36 states)

21+ only |

21 | ||||

| Maine | For carrying in state/national parks, regular archery hunting during deer season, employees' vehicles on work premises and concealed carry between ages 18–20 | Partial (27 states)

Resident permits only 18+ Can carry permitless if 21+; 18+ if military |

18 with permit | |||

| Maryland | No | 21 | ||||

| Massachusetts | No | 21 | ||||

| Michigan | Yes

Resident permits only |

21 | ||||

| Minnesota | Partial (17 states) | 18 by court order | ||||

| Mississippi | For concealed carry without a belt/shoulder holster, sheath, purse, handbag, satchel, other similar bag or briefcase or fully enclosed. For carrying concealed at any polling place, meeting place of the state legislature or other governing body, school, college, professional athletic event, establishment licensed to serve alcoholic beverages, passenger terminal of an airport, federal buildings (under state law), permitted parade/demonstration or courthouse for those with an enhanced firearms permit. | Yes | 18 | |||

| Missouri | For open carry in localities where restricted | Yes | 18 | |||

| Montana | Partial (43 states)

Can carry permitless |

18 | ||||

| Nebraska | Partial (35 states + DC)

21+ only |

21 | ||||

| Nevada | Partial (24 states) | 21 | ||||

| New Hampshire | Partial (28 states)

Resident permits only Can carry permitless |

18* | ||||

| New Jersey | No | 21 | ||||

| New Mexico | Unloaded | Partial (23 states)

21+ only |

21 | |||

| New York | No | 21 | ||||

| New York City | Does not recognize any other jurisdictions' permits. Permits may be approved by the city's police commissioner on an individual basis. | 21 | ||||

| North Carolina | Yes | 21 (18 with out of state carry permit) | ||||

| North Dakota | For open-carry | Partial (39 states)

Can carry permitless |

18 | |||

| Northern Mariana Islands | No | N/A | ||||

| Ohio | Yes | 21 (18 with out of state carry permit) | ||||

| Oklahoma | Yes | 21 | ||||

| Oregon | No | 21 | ||||

| Pennsylvania | Partial (29 states)

Resident permits only 21+ only All permits recognized for vehicle carry |

21 | ||||

| Puerto Rico | From June 20, 2015, to October 31, 2016. | Has reciprocity law, but does not recognize any other state permits | 21 | |||

| Rhode Island | Vehicle carry only | 21 | ||||

| South Carolina | Partial (29 states)

Resident permits only |

21 | ||||

| South Dakota | Yes | 18 | ||||

| Tennessee | For carrying in buildings posted with "concealed firearms by permit only" signs, state/national parks, campgrounds, greenways, and nature trails | Yes | 18 by court order | |||

| Texas | Partial (43 states)

Can carry permitless |

18 by court order | ||||

| United States Virgin Islands | Has reciprocity law, but does not recognize any other state permits | 21 | ||||

| Utah | For carrying between ages 18–20 | Yes | 18 with permit | |||

| Vermont | N/A | 16 | ||||

| Virginia | Yes

21+ only |

21 | ||||

| Washington | Any person engaging in a lawful outdoor recreational activity such as hunting, fishing, camping, hiking, or horseback riding, so long as it is reasonable to assume that they are performing that activity or traveling to or from the activity. | Partial (9 states)

21+ only |

21 | |||

| West Virginia | For concealed carry between ages 18–20 | Partial (35 states)

Can carry permitless 21+ only; 18+ if military for both |

18 with permit | |||

| Wisconsin | Partial (44 states + DC, PR & VI)

21+ only |

21 | ||||

| Wyoming | Partial (35 states)

Can carry permitless |

21 (18 with out of state carry permit) | ||||

| U.S. Military installations | No | 21 | ||||

| Native American reservations | Varies | Varies | Varies |

* Jurisdiction gives no minimum age to conceal carry in law. The age is set at 18 by federal law.

Unrestricted jurisdictions

Main article: Constitutional carryAn unrestricted jurisdiction is one in which a permit is not required to carry a concealed handgun. This is sometimes called constitutional carry. Within the unrestricted category, there exist states that are fully unrestricted, where no permit is required for lawful open or concealed carry, and partially unrestricted, where certain forms of concealed carry may be legal without a permit, while other forms of carry may require a permit.

Some states have a limited form of permitless carry, restricted based on one or more of the following: a person's location, the loaded/unloaded state of the firearm, or the specific persons who may carry without a permit. As of February 18, 2021, these states are Illinois, New Mexico, and Washington. Some states that allow permitless concealed carry and still issue concealed carry permits may impose restrictions on concealed carry for certain places and/or at certain times (e.g., special events, large public gatherings, etc.). In some such situations, those holding a valid concealed carry permit may be exempt from such restrictions.

Permit requirement jurisdictions

A permit requirement jurisdiction is one in which a government-issued permit is required to carry a concealed handgun in public. Before the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen, these jurisdictions were further split between "shall-issue", which is the current national licensing standard where the granting of licenses is subject only to meeting determinate criteria laid out in the law, and "may-issue" where the granting of such licenses was at the discretion of local authorities. Since the abolishment of "may-issue" permitting the U.S. Supreme Court has stated it is still legal for U.S. jurisdictions subject to the Constitution to require a permit to carry a concealed handgun, and that background checks, training, and proper fees can be required without violating the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution which guarantees a right of the people to carry a concealed firearm outside of the home.

Concealed carry on U.S. military installations

While members of the Armed Services may receive extensive small arms training, United States Military installations have some of the most restrictive rules for the possession, transport, and carrying of personally-owned firearms in the country.

Overall authority for carrying a personally-owned firearm on a military installation rests with the installation commander, although the authority to permit individuals to carry firearms on an installation is usually delegated to the Provost Marshal. Military installations do not recognize state-issued concealed carry permits, and state firearms laws generally do not apply to military bases, regardless of the state in which the installation is located. Federal law (18 USC, Section 930) generally forbids the possession, transport, and carrying of firearms on military installations without approval from the installation commander. Federal law gives installation commanders wide discretion in establishing firearms policies for their respective installations. In practice, local discretion is often constrained by policies and directives from the headquarters of each military branch and major commands.

Installation policies can vary from no-issue for most bases to shall-issue in rare circumstances. Installations that do allow the carrying of firearms typically restrict carrying to designated areas and for specific purposes (i.e., hunting or officially sanctioned shooting competitions in approved locations on the installation). Installation commanders may require the applicant to complete extensive firearms safety training, undergo a mental health evaluation, and obtain a letter of recommendation from their unit commander (or employer) before such authorization is granted. Personnel that reside on a military installation are typically required to store their personally-owned firearms in the installation armory, although the installation commander or provost marshal may permit a service member to store their personal firearms in their on-base dwelling if they have a gun safe or similarly designed cabinet where the firearms can be secured.

Prior to 2011, military commanders could impose firearms restrictions to servicemembers residing off-base, such as mandatory registration of firearms with the base provost marshal, restricting or banning the carrying of firearms by servicemembers either on or off the installation regardless of whether the member had a state permit to carry, and requiring servicemembers to have a gun safe or similar container to secure firearms when not in use. A provision was included in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2011 that limited commanders' authority to impose restrictions on the possession and use of personally-owned firearms by service members who reside off-base.

Concealed carry on Native American reservations

Concealed carry policies on Native American reservations are covered by the tribal laws for each reservation, which vary widely from "No-Issue" to "Shall-Issue" and "Unrestricted" either in law or in practice. Some Native American tribes recognize concealed carry permits for the state(s) in which the reservation is located, while others do not. For reservations that do not recognize state-issued concealed carry permits, some completely ban concealed carry, while others offer a tribal permit for concealed carry issued by the tribal police or tribal council. Tribal concealed carry permits may be available to the general populace or limited to tribal members, depending on tribal policies. Tribal law typically pre-empts state law on the reservation. The only exception is while traversing the reservation on a state-owned highway (including interstate, U.S. routes, and in some instances county roads), in which case state law and the federal Firearm Owners' Protection Act (FOPA) apply.

Limitations on concealed carry

Prohibitions of the concealed carry of firearms and other weapons by local governments predate the establishment of the United States. In 1686, New Jersey law stated "no person or persons … shall presume privately to wear any pocket pistol … or other unusual or unlawful weapons within this Province." After the federal government was established, states and localities continued to restrict people from carrying hidden weapons. Tennessee law prohibited this as early as 1821. By 1837, Georgia passed into effect “An Act to guard and protect the citizens of this State, against the unwarrantable and too prevalent use of deadly weapons." Two years later, Alabama followed suit with “An Act to Suppress the Evil Practice of Carrying Weapons Secretly." Delaware prohibited the practice in 1852. Ohio did the same in 1859, a policy that remained in effect until 1974. Cities also regulated weapons within their boundaries. In 1881, Tombstone, Arizona, enacted Ordinance No. 9 "To Provide against Carrying of Deadly Weapons", a regulation that sparked the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral later that year.

Some permit requirement jurisdictions allow issuing authorities to impose limitations on CCW permits, such as the type and caliber of handguns that may be carried (Rhode Island, New Mexico), restrictions on places where the permit is valid (New York, Massachusetts, Illinois), restricting concealed carry to purposes or activities specified on the approved permit application (California, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York), limitations on magazine size (Connecticut, Massachusetts, New York), or limitations on the number of firearms that may be carried concealed by a permit-holder at any given time (some states). Permits issued by all but two states (New York and Hawaii) are valid statewide. New York State pistol licenses, which are generally issued by counties, are valid statewide with one exception. A permit not issued by New York City is invalid in that city unless validated by its police commissioner. Permits issued by Hawaii are valid only in the county of issuance.

Training requirements

Some states require concealed carry applicants to certify their proficiency with a firearm through some type of training or instruction. Certain training courses developed by the National Rifle Association that combine classroom and live-fire instruction typically meet most state training requirements. Some states recognize prior military or police service as meeting training requirements.

Classroom instruction would typically include firearm mechanics and terminology, cleaning and maintenance of a firearm, concealed carry legislation and limitations, liability issues, carry methods and safety, home defense, methods for managing and defusing confrontational situations, and practice of gun handling techniques without firing the weapon. Most required CCW training courses devote a considerable amount of time to liability issues.

Depending on the state, a practical component during which the attendee shoots the weapon for the purpose of demonstrating safety and proficiency, may be required. During range instruction, applicants would typically learn and demonstrate safe handling and operation of a firearm and accurate shooting from common self-defense distances. Some states require a certain proficiency to receive a passing grade, whereas other states (e.g., Florida) technically require only a single shot to be fired to demonstrate handgun handling proficiency.

CCW training courses are typically completed in a single day and are good for a set period, the exact duration varying by state. Some states require re-training, sometimes in a shorter, simpler format, for each renewal.

A few states, e.g., South Carolina, recognize the safety and use-of-force training given to military personnel as acceptable in lieu of formal civilian training certification. Such states will ask for a military ID (South Carolina) for active persons or DD214 for honorably discharged persons. These few states will commonly request a copy of the applicant's BTR (Basic Training Record) proving an up-to-date pistol qualification. Active and retired law enforcement officers are generally exempt from qualification requirements, due to a federal statute permitting qualified active and retired law enforcement officers to carry concealed weapons in the United States.

Virginia recognizes eight specific training options to prove competency in handgun handling, ranging from DD214 for honorably discharged military veterans, to certification from law enforcement training, to firearms training conducted by a state or NRA-certified firearms instructor including electronic, video, or online courses. While any one of the eight listed options will be considered adequate proof, individual circuit courts may recognize other training options. A small number of states, such as Alabama and Georgia, have no training requirements to obtain a permit—only a requirement that the applicant successfully pass the required background check before issuance.

Reciprocity

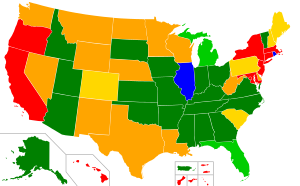

Level of permit reciprocity (recognition of out-of-state permits):

Full reciprocity Full reciprocity for resident permits only Full reciprocity for vehicle carry only Partial reciprocity Partial reciprocity for resident permits only No reciprocityMany jurisdictions recognize (honor) a permit or license issued by other jurisdictions. Recognition may be granted to all jurisdictions or some subset that meets a set of permit-issuing criteria, such as training comparable to the honoring jurisdiction or certain background checks. Several states have entered into formal agreements to mutually recognize permits. This arrangement is commonly called reciprocity or mutual recognition. A few states do not recognize permits issued by any other jurisdiction but offer non-resident permits for out-of-state individuals (who possess a valid concealed carry permit from their home state) who wish to carry while visiting such states. There are also states that neither recognize out-of-state concealed carry permits nor issue permits to non-residents, resulting in a complete ban on concealed carry by non-residents in such states. There are also states (Illinois and Rhode Island) that do not recognize out-of-state permits for carry-on-foot but do permit individuals with out-of-state concealed carry permits to carry while traveling in their vehicle (normally in accordance with the rules of the state of issuance).

Recognition and reciprocity of concealed carry privileges vary. Some states (e.g. Indiana, Virginia, Ohio) unilaterally recognize all permits. Others such as Michigan, limit such universal recognition to residents of the permit-issuing state. While 37 states have reciprocity agreements with at least one other state and several states honor all out-of-state concealed carry permits, some states have special requirements like training courses or safety exams, and therefore do not honor permits from states that do not have such requirements for issue. Some states make exceptions for persons under the minimum age (usually 21) if they are active or honorably discharged members of the military or a police force (the second of these two is subject additionally to federal law). States that do not have this exemption generally do not recognize any license from states that do. An example of this is the state of Washington's refusal to honor any Texas LTC as Texas has the military exception to age. Idaho, Mississippi, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Tennessee have standard and enhanced permits that have different requirements to obtain and also have unique reciprocity with different states; Utah and West Virginia have provisional permits for 18-20-year-olds with more limited recognition by other states.

Permits from Idaho (enhanced), Kansas, Michigan, North Dakota (class 1), and North Carolina have the highest number of recognition by other states (39 states). One can obtain multiple state permits in an effort to increase the number of states where that user can carry a legally concealed weapon. It is common practice to use a CCW Reciprocity Map to gain clarity on which states will honor the person's combination of resident and non-resident permits given the variety of standards and legal policies from state to state. There are also various mobile applications that guide users in researching state concealed carry permit reciprocity.

Although carry may be legal under State law in accordance with reciprocity agreements, the Federal Gun Free School Zones Act subjects an out-of-state permit holder to federal felony prosecution if they carry a firearm within 1000 feet of any K–12 school's property line; however, the enforcement of this statute is rare given several states' nullification statutes prohibiting state law enforcement officers from enforcing federal firearms laws. However, states may have their own similar statutes that such officers will enforce, and potentially expose the carrier to later prosecution under the Act.

Restricted premises

While generally a concealed carry permit allows the permit holder to carry a concealed weapon in public, a state may restrict carry of a firearm including a permitted concealed weapon while in or on certain properties, facilities or types of businesses that are otherwise open to the public. These areas vary by state (except for the first item below; federal offices are subject to superseding federal law) and can include:

- Federal government facilities, including post offices, IRS offices, federal court buildings, military/VA facilities and/or correctional facilities, Amtrak trains and facilities, and Corps of Engineers-controlled property (carry in these places is prohibited by federal law and preempts any existing state law). Carry on land controlled by the Bureau of Land Management (federal parks and wildlife preserves) is allowed by federal law as of the 2009 CARD Act, but is still subject to state law. However, carry into restrooms or any other buildings or structures located within federal parks is illegal in the United States, despite concealed carry being otherwise legal in federal parks with a permit recognized by the state in which the federal park is located. Similarly, concealed carry into caves located within federal parks is illegal.

- State and local government facilities, including courthouses, DMV/DoT offices, police stations, correctional facilities, and/or meeting places of government entities (exceptions may be made for certain persons working in these facilities such as judges, lawyers, and certain government officials both elected and appointed)

- Venues for political events, including rallies, parades, debates, and/or polling places

- Educational institutions including elementary/secondary schools and colleges. Some states have "drop-off exceptions" which only prohibit carry inside school buildings, or permit carry while inside a personal vehicle on school property. Campus carry laws vary by state.

- Public interscholastic and/or professional sporting events and/or venues (sometimes only during a time window surrounding such an event)

- Amusement parks, fairs, parades and/or carnivals

- Businesses that sell alcohol (sometimes only "by-the-drink" sellers like restaurants, sometimes only establishments defined as a "bar" or "nightclub", or establishments where the percentage of total sales from alcoholic beverages exceeds a specified threshold)

- Hospitals (even if hospitals themselves are not restricted, "teaching hospitals" partnered with a medical school are sometimes considered "educational institutions"; exceptions are sometimes made for medical professionals working in these facilities)

- Churches, mosques and other "Houses of worship", usually at the discretion of the church clergy (Ohio allows with specific permission of house of worship)

- Municipal mass transit vehicles or facilities

- Sterile areas of airports (sections of the airport located beyond security screening checkpoints, unless explicitly authorized)

- Non-government facilities with heightened security measures (Nuclear facilities, power plants, dams, oil and gas production facilities, banks, factories, unless explicitly authorized)

- Aboard aircraft or ships unless specifically authorized by the pilot in command or ship captain

- Private property where the lawful owner or lessee has posted a sign or verbally stated that firearms are not permitted. Some states have enacted laws prohibiting the carrying of firearms on private property, unless the property owner or lawful occupant has explicitly granted permission for the carrying of weapons on the premises.

- Any public place, while under the influence of alcohol or drugs (including certain prescription or over-the-counter medications, depending on jurisdiction)

"Opt-out" statutes ("gun-free zones")

Some states allow private businesses to post a specific sign prohibiting concealed carry within their premises. The exact language and format of such a sign varies by state. By posting the signs, businesses create areas where it is illegal to carry a concealed handgun—similar to regulations concerning schools, hospitals, and public gatherings.

Violation of such a sign, in some of these states, is grounds for revocation of the offender's concealed carry permit and criminal prosecution. Other states, such as Virginia, enforce only trespassing laws when a person violates a "Gun Free Zone" sign. In some jurisdictions, trespass by a person carrying a firearm may have more severe penalties than "simple" trespass, while in other jurisdictions, penalties are lower than for trespass.

Such states include Arizona, Arkansas, Connecticut, Illinois, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and Wisconsin.

There is considerable dispute over the effectiveness of such "gun-free zones". Opponents of such measures, such as OpenCarry.org, state that, much like other malum prohibitum laws banning gun-related practices, only law-abiding individuals will heed the signage and disarm. Individuals or groups intent on committing far more serious crimes, such as armed robbery or murder, will not be deterred by signage prohibiting weapons. Further, the reasoning follows that those wishing to commit mass murder might intentionally choose gun-free venues like shopping malls, schools, and churches (where weapons carry is generally prohibited by statute or signage) because the population inside is disarmed and thus less able to stop them.

In some states, business owners have been documented posting signs that appear to prohibit guns, but legally do not because the signs do not meet local or state laws defining the required appearance, placement, or wording of signage. Such signage can be posted out of ignorance of the law, or intent to pacify gun control advocates while not actually prohibiting the practice. The force of law behind a non-compliant sign varies based on state statutes and case law. Some states interpret their statutes' high level of specification of signage as evidence that the signage must meet the specification exactly, and any quantifiable deviation from the statute makes the sign non-binding. Other states have decided in case law that if efforts were made in good faith to conform to the statutes, the sign carries the force of law even if it fails to meet current specifications. Still, others have such lax descriptions of what is a valid sign that virtually any sign that can be interpreted as "no guns allowed" is binding on the license holder.

Note that virtually all jurisdictions allow some form of oral communication by the lawful owner or controller of the property that a person is not welcome and should leave. This notice can be given to anyone for any reason (except for statuses that are protected by the Federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 and other CRAs, such as race), including due to the carrying of firearms by that person, and refusal to heed such a request to leave may constitute trespassing.

Brandishing and printing

Printing refers to a circumstance where the shape or outline of a firearm is visible through a garment while the gun is still fully covered, and is generally not desired when carrying a concealed weapon. Brandishing can refer to different actions depending on jurisdiction. These actions can include printing through a garment, pulling back clothing to expose a gun, or unholstering a gun and exhibiting it in the hand. The intent to intimidate or threaten someone may or may not be required legally for it to be considered brandishing.

Brandishing is a crime in most jurisdictions, but the definition of brandishing varies widely.

Under California law, the following conditions have to be present to prove brandishing:

A person, in the presence of another person, drew or exhibited a ; That person did so in a rude, angry, or threatening manner That person, in any manner, unlawfully used the in a fight or quarrel The person was not acting in lawful self-defense.]

In Virginia law:

It shall be unlawful for any person to point, hold or brandish any firearm or any air or gas operated weapon or any object similar in appearance, whether capable of being fired or not, in such manner as to reasonably induce fear in the mind of another or hold a firearm or any air or gas operated weapon in a public place in such a manner as to reasonably induce fear in the mind of another of being shot or injured. However, this section shall not apply to any person engaged in excusable or justifiable self-defense.

— Code of Virginia 18.2-282

Federal law

Gun Control Act of 1968

The Gun Control Act passed by Congress in 1968 lists felons, illegal aliens, and other codified persons as prohibited from purchasing or possessing firearms. During the application process for concealed carry, states carry out thorough background checks to prevent these individuals from obtaining permits. Additionally, the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act created an FBI-maintained system in 1994 for instantly checking the backgrounds of potential firearms buyers in an effort to prevent these individuals from obtaining weapons.

Firearm Owners Protection Act

The Firearm Owners Protection Act (FOPA) of 1986 allows a gun owner to travel through states in which their firearm possession is illegal as long as it is legal in the states of origination and destination, the owner is in transit and does not remain in the state in which firearm possession is illegal, and the firearm is transported unloaded and in a locked container. The FOPA addresses the issue of transport of private firearms from origin to destination for purposes lawful in state of origin and destination; FOPA does not authorize concealed carry as a weapon of defense during transit. New York State Police arrested those carrying firearms in violation of state law, and then required them to use FOPA as an affirmative defense to the charges of illegal possession.

Law Enforcement Officers Safety Act

In 2004, the United States Congress enacted the Law Enforcement Officers Safety Act, 18 U.S. Code 926B and 926C. This federal law allows two classes of persons – the "qualified law enforcement officer" and the "qualified retired law enforcement officer" – to carry a concealed firearm in any jurisdiction in the United States, regardless of any state or local law to the contrary, with the exception of areas where all firearms are prohibited without permission, and certain Title II weapons.

Federal Gun Free School Zones Act

The Federal Gun Free School Zone Act limits where a person may legally carry a firearm. It does this by making it generally unlawful for an armed citizen to be within 1,000 feet (extending out from the property lines) of a place that the individual knows, or has reasonable cause to believe, is a K–12 school. Although a state-issued carry permit may exempt a person from this restriction in the state that physically issued their permit, it does not exempt them in other states which recognize their permit under reciprocity agreements made with the issuing state.

Federal property

Some federal statutes restrict the carrying of firearms on the premises of certain federal properties such as military installations or land controlled by the USACE.

National park carry

On May 22, 2009, President Barack Obama signed H.R. 627, the "Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure Act of 2009", into law. The bill contained a rider introduced by Senator Tom Coburn (R-OK) that prohibits the Secretary of the Interior from enacting or enforcing any regulations that restrict possession of firearms in National Parks or Wildlife Refuges, as long as the person complies with laws of the state in which the unit is found. This provision was supported by the National Rifle Association and opposed by the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence, the National Parks Conservation Association, and the Coalition of National Park Service Retirees, among other organizations. As of February 2010 concealed handguns are for the first time legal in all but 3 of the nation's 391 national parks and wildlife refuges so long as all applicable federal, state, and local regulations are adhered to. Hawaii is a notable exception. Concealed and open carry are both illegal in Hawaii for all except retired military or law enforcement personnel. Previously firearms were allowed into parks if cased and unloaded.

Full faith and credit (CCW permits)

Attempts were made in the 110th Congress, United States House of Representatives (H.R. 226) and the United States Senate (S. 388), to enact legislation to compel complete reciprocity for concealed carry licenses. Opponents of national reciprocity have pointed out that this legislation would effectively require states with more restrictive standards of permit issuance (e.g., training courses, safety exams, "good cause" requirements, etc.) to honor permits from states with more liberal issuance policies. Supporters have pointed out that the same situation already occurs with marriage certificates, adoption decrees, and other state documents under the "full faith and credit" clause of the U.S. Constitution. Some states have already adopted a "full faith and credit" policy treating out-of-state carry permits the same as out-of-state driver's license or marriage certificates without federal legislation mandating such a policy. In the 115th Congress, another universal reciprocity bill, the Concealed Carry Reciprocity Act of 2017, was introduced by Richard Hudson. The bill passed the House but did not get a vote in the Senate.

Legal issues

Court rulings

Prior to the 1897 Supreme Court case Robertson v. Baldwin, the federal courts had been silent on the issue of concealed carry. In the dicta from a maritime law case, the Supreme Court commented that state laws restricting concealed weapons do not infringe upon the right to bear arms protected by the federal Second Amendment. However, in the context of such rulings, open carry of firearms was generally unrestricted in the jurisdictions in question, which provided an alternative means of "bearing" arms.

In the majority decision in the 2008 Supreme Court case of District of Columbia v. Heller, Justice Antonin Scalia wrote;

Like most rights, the Second Amendment right is not unlimited. It is not a right to keep and carry any weapon whatsoever in any manner whatsoever and for whatever purpose: For example, concealed weapons prohibitions have been upheld under the Amendment or state analogues ... The majority of the 19th-century courts to consider the question held that prohibitions on carrying concealed weapons were lawful under the Second Amendment or state analogs.

Heller was a landmark case because, for the first time in United States history, a Supreme Court decision defined the right to bear arms as constitutionally guaranteed to private citizens rather than a right restricted to "well-regulated militia". The Justices asserted that sensible restrictions on the right to bear arms are constitutional, however, an outright ban on a specific type of firearm, in this case handguns, was in fact unconstitutional. The Heller decision is limited because it only applies to federal enclaves such as the District of Columbia. In 2010, the SCOTUS expanded Heller in McDonald v. Chicago incorporating the 2nd Amendment through the 14th Amendment as applying to local and state laws. Various Circuit Courts have upheld their local and state laws using intermediate scrutiny. The correct standard is a strict scrutiny review for all "fundamental" and "individual" rights. On June 28, 2010, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the handgun ban enacted by the city of Chicago, Illinois, in McDonald v. Chicago, effectively extending the Heller decision to states and local governments nationwide. Banning handguns in any jurisdiction has the effect of rendering invalid any licensed individual's right to carry concealed in that area except for federally exempted retired and current law enforcement officers and other government employees acting in the discharge of their official duties.

In 2022, the Supreme Court ruled in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen, that the Second Amendment does protect "an individual's right to carry a handgun for self-defense outside the home." The case struck down New York's strict law requiring people to show "proper cause" in order to get a concealed weapons permit, and could affect similar laws in other states such as California, Hawaii, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Rhode Island. Shortly after the Supreme Court ruling, the attorney generals of each of California, Hawaii (concealed-carry licenses only), Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Rhode Island (permits issued by municipalities only) issued guidance that their "proper cause" or similar requirements would no longer be enforced.

Legal liability

Even when self-defense is justified, there can be serious civil or criminal liabilities related to self-defense when a concealed carry permit holder brandishes or fires their weapon. For example, if innocent bystanders are hurt or killed, there could be both civil and criminal liabilities even if the use of deadly force was completely justified. Some states technically allow an assailant who is shot by a gun owner to bring a civil action. In some states, liability is present when a resident brandishes the weapon, threatens use, or exacerbates a volatile situation, or when the resident is carrying it while intoxicated. It is important to note that simply pointing a firearm at any person constitutes felony assault with a deadly weapon unless circumstances validate a demonstration of force. A majority of states that allow concealed carry, however, forbid suits being brought in such cases, either by barring lawsuits for damages resulting from a criminal act on the part of the plaintiff, or by granting the gun owner immunity from such a civil suit if it is found that they were justified in shooting.

Simultaneously, increased passage of "Castle Doctrine" laws allow persons who own firearms and/or carry them concealed to use them without first attempting to retreat. The "Castle Doctrine" typically applies to situations within the confines of one's own home. Nevertheless, many states have adopted escalation of force laws along with provisions for concealed carry. These include the necessity to first verbally warn a trespasser or lay hands on a trespasser before a shooting is justified (unless the trespasser is armed or assumed to be so). This escalation of force does not apply if the shooter reasonably believes a violent felony has been or is about to be committed on the property by the trespasser. Additionally, some states have a duty to retreat provision which requires a permit holder, especially in public places, to vacate themself from a potentially dangerous situation before resorting to deadly force. The duty to retreat does not restrictively apply in a person's home or business though escalation of force may be required. In 1895 the Supreme Court ruled in Beard v. United States that if an individual does not provoke an assault and is residing in a place they have a right to be, then they may use considerable force against someone they reasonably believe may do them serious harm without being charged with murder or manslaughter should that person be killed. Further, in Texas and California homicide is justifiable solely in defense of property. In other states, lethal force is authorized only when serious harm is presumed to be imminent.

Even given these relaxed restrictions on the use of force, using a handgun must still be a last resort in some jurisdictions; meaning the user must reasonably believe that nothing short of deadly force will protect the life or property at stake in a situation. Additionally, civil liabilities for errors that cause harm to others still exist, although civil immunity is provided in the Castle Doctrine laws of some states (e.g., Texas).

Penalties for carrying illegally

Main article: Criminal possession of a weaponCriminal possession of a weapon is the unlawful possession of a weapon by a citizen. Many societies both past and present have placed restrictions on what forms of weaponry private citizens (and to a lesser extent police) are allowed to purchase, own, and carry in public. Such crimes are public order crimes and are considered mala prohibita, in that the possession of a weapon in and of itself is not evil. Rather, the potential for use in acts of unlawful violence creates a possible need to control them. Some restrictions are strict liability, whereas others require some element of intent to use the weapon for an illegal purpose. Some regulations allow a citizen to obtain a permit or other authorization to possess the weapon under certain circumstances. Lawful uses of weapons by civilians commonly include hunting, sport, collection and self-preservation.

The penalties for carrying a firearm in an unlawful manner vary widely from state-to-state, and may range from a simple infraction punishable by a fine to a felony conviction and mandatory incarceration. An individual may also be charged and convicted of criminal charges other than unlawful possession of a firearm, such as assault, disorderly conduct, disturbing the peace, or trespassing. In the case of an individual with no prior criminal convictions, the state of Tennessee classifies the unlawful concealed carry of a loaded handgun as a Class C misdemeanor punishable by a maximum of 30 days imprisonment and/or a $500 fine. While in New York State, a similar crime committed by an individual with no criminal convictions is classified as a Class D felony, punishable by a mandatory minimum of 3.5 years imprisonment, to a maximum of 7 years. As New York State does not recognize any pistol permits issued in other states, the statute would apply to any individual who does not have a valid New York State issued concealed carry permit, even if such individual has a valid permit issued in another jurisdiction. In addition, the New York State statutory definition of a "loaded firearm" differs significantly from what may be commonly understood, as simply possessing any ammunition along with a weapon capable of firing such ammunition satisfies the legal definition of a loaded firearm in New York. The large variability of state carry laws has resulted in confusing circumstances where a person in Vermont (which requires no license of any kind to carry a concealed weapon by anyone who is not prohibited by law), could unwittingly travel into the adjacent state of New York, where such individual, despite acting entirely within the law of Vermont, would then face a mandatory 3.5-year prison sentence simply for accidentally crossing the state's border into New York. These circumstances are aggravated by the fact that many NYS police departments as well as the New York State Police do not recognize the protections granted federally under the Firearm Owners Protection Act, which was intended to prevent such prosecutions.

Effect on crime and deaths

Research has had mixed results, indicating variously that right-to-carry laws have no impact on violent crime, that they increase violent crime, and that they decrease violent crime.

A 2020 study by the RAND Corporation of over 200 combinations of gun policies and outcomes found "supportive evidence that shall-issue concealed carry laws are associated with increased firearm homicides and total homicides". They also found supportive evidence that child access prevention laws reduce firearm homicides and self-injuries among youth, and further evidence supporting the conclusion that stand-your-ground laws are associated with increased levels of firearm homicides. The researchers credit a much greater investment in gun safety research over the past few years with providing this and other more recent studies with stronger and more reliable evidence.

A 2004 review of the existing literature by the National Academy of Sciences found that the results of existing studies were sensitive to the specification and time period examined, and concluded that a causal link between right-to-carry laws and crime rates cannot be shown. Quinnipiac University economist Mark Gius summarized literature published between 1993 and 2005, and found that ten papers suggested that permissive CCW laws reduce crime, one paper suggested they increase crime, and nine papers showed no definitive results. A 2017 review of the existing literature concluded, "Given the most recent evidence, we conclude with considerable confidence that deregulation of gun carrying over the last four decades has undermined public safety—which is to say that restricting concealed carry is one gun regulation that appears to be effective." A 2016 study in the European Economic Review which examined the conflicting claims in the existing literature concluded that the evidence CCW either increases or decreases crime on average "seems weak"; the study's model found "some support to the law having a negative (but with a positive trend) effect on property crimes, and a small but positive (and increasing) effect on violent crimes". The Washington Post fact-checker concluded that it could not state that CCW laws reduced crime, as the evidence was murky and in dispute. In a 2017 article in the journal Science, Stanford University law professor John Donohue and Duke University economist Philip J. Cook write that "there is an emerging consensus that, on balance, the causal effect of deregulating concealed carry (by replacing a restrictive law with an RTC law) has been to increase violent crime". Donohue and Cook argue that the crack epidemic made it difficult to determine the causal effects of CCW laws and that this made earlier results inconclusive; recent research does not suffer the same challenges with causality. A 2018 RAND review of the literature concluded that concealed carry either has no impact on crime or that it may increase violent crime. The review said, "We found no qualifying studies showing that concealed-carry laws decreased ."

A 2020 study in PNAS found that right-to-carry laws were associated with higher firearm deaths. A 2019 panel study published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine by medical researchers including Michael Siegel of the Boston University School of Public Health and David Hemenway of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health found that “shall issue" concealed carry laws were associated with a 9% increase in homicides. A 2019 study in the American Journal of Public Health found that greater restrictions on concealed carry laws were associated with decreases in workplace homicide rates. Another 2019 study in the American Journal of Public Health found that states with right-to-carry laws were associated with a 29% higher rate of firearm workplace homicides. A 2019 study in the Journal of Empirical Legal Studies found that right-to-carry laws led to an increase in overall violent crime. A 2017 study in the American Journal of Public Health found that "shall-issue laws" (where concealed carry permits must be given if criteria are met) "are associated with significantly higher rates of total, firearm-related, and handgun-related homicide" than "may-issue laws" (where local law enforcement have discretion over who can get a concealed carry permit). A 2011 study found that aggravated assaults increase when concealed carry laws are adopted.

A 2019 study in Journal of American College of Surgeons found "no statistically significant association between the liberalization of state level firearm carry legislation over the last 30 years and the rates of homicides or other violent crime." This is also in line with a 1997 study researching county-level data from 1977 to 1992 concluding that allowing citizens to carry concealed weapons deters violent crimes and it appears to produce no increase in accidental deaths. A 2018 study in The Review of Economics and Statistics found that the impact of right-to-carry laws was mixed and changed over time. RTC laws increased some crimes over some periods while decreasing other crimes over other periods. The study suggested that conclusions drawn in other studies are highly dependent on the time periods that are studied, the types of models that are adopted and the assumptions that are made. A 2015 study that looked at issuance rates of concealed-carry permits and changes in violent crime by county-level in four shall-issue states found no increases or decreases in violent crime rates with changes in permit issuances. A 2019 study in the International Review of Law and Economics found that with one method, right-to-carry laws had no impact on violent crime, but with another method led to an increase in violent crime; neither method showed that right-to-carry laws led to a reduction in crime. A 2003 study found no significant changes in violent crime rates amongst 58 Florida counties with increases of concealed-carry permits. A 2004 study found no significant association between homicide rates and shall-issue concealed carry laws.

A 2013 study of eight years of Texas data found that concealed handgun licensees were much less likely to be convicted of crimes than were nonlicensees. The same study found that licensees' convictions were more likely to be for less common crimes, "such as sexual offenses, gun offenses, or offenses involving a death." A 2020 study in Applied Economics Letters examining concealed-carry permits per capita by state found a significant negative effect on violent crime rates. A 2016 study found a significant negative effect on violent crime rates with passage of shall-issue laws. A 2017 study in Applied Economics Letters found that property crime decreased in Chicago after the implementation of the shall issue concealed carry law. A 2014 Applied Economics Letters study found states with more permissive conceal carry laws had lower murder rates than states with restrictive laws. Another 2014 study found that RTC laws by state significantly reduce homicide rates.

In 1996 economists John R. Lott, Jr. and David B. Mustard analyzed crime data in all 3,054 counties in the United States from 1977 to 1992, finding counties that had shall-issue licensing laws overall saw murders decrease by 7.65 percent, rapes decrease by 5.2 percent, aggravated assaults decrease by 7 percent and robberies decrease by 2.2 percent. The study was widely disputed by numerous economists. The 2004 National Academy of Sciences panel reviewing the research on the subject concluded, with one dissenting panelist, that the Lott and Mustard study was unreliable. Georgetown University Professor Jens Ludwig, Daniel Nagin of Carnegie Mellon University and Dan A. Black of the University of Chicago in The Journal of Legal Studies, said of the Lott-Mustard study, "once Florida is removed from the sample, there is no longer any detectable impact of right-to-carry laws on the rates of murder and rape".

A 2022 study examining the Sullivan Act of 1911 found that the law had no impact on overall homicide rates, reduced overall suicide rates, and caused large and sustained decrease in gun-related suicide rates.

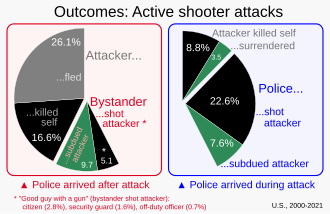

Firearms permit holders in active shooter incidents

In 2016 FBI analyzed 40 "active shooter incidents" in 2014 and 2015 where bystanders were put in peril in ongoing incidents that could be affected by police or citizen response. Six incidents were successfully ended when citizens intervened. In two stops citizens restrained the shooters, one unarmed, one with pepper spray. In two stops at schools, the shooters were confronted by teachers: one shooter disarmed, and one committed suicide. In two stops citizens with firearms permits exchanged gunfire with the shooter. In a failed stop attempt, a citizen with a firearms permit was killed by the shooter. In 2018 the FBI analyzed 50 active shooter incidents in 2016 and 2017. This report focused on policies to neutralize active shooters to save lives. In 10 incidents citizens confronted an active shooter. In eight incidents the citizens stopped the shooter. Four stops involved unarmed citizens who confronted and restrained or blocked the shooter or talked the shooter into surrendering. Four stops involved citizens with firearms permits: two exchanged gunfire with a shooter and two detained the shooter at gunpoint for arrest by responding police. Of the two failed stops, one involved a permit holder who exchanged gunfire with the shooter but the shooter fled and continued shooting and the other involved a permit holder who was wounded by the shooter. "Armed and unarmed citizens engaged the shooter in 10 incidents. They safely and successfully ended the shootings in eight of those incidents. Their selfless actions likely saved many lives."

See also

- American gun ownership

- Concealed carry

- Defensive gun use

- Gun control

- Gun politics in the United States

- Overview of gun laws by nation

- Self-defense

Notes

- Permit not required as of July 4, 2024.

References

- ^ Smart, Rosanna; Morral, Andrew; Smucker, Sierra; Cherney, Samantha; Schell, Terry; Peterson, Samuel; Ahluwalia, Sangeeta; Cefalu, Matthew; Xenakis, Lea; Ramchand, Rajeev; Gresenz, Carole (2020). The Science of Gun Policy: A Critical Synthesis of Research Evidence on the Effects of Gun Policies in the United States, Second Edition. doi:10.7249/rr2088-1. ISBN 9781977404312. S2CID 51928649.

- "Effects of Concealed-Carry Laws on Violent Crime". RAND Corporation.

- ^ 6 Right-to-Carry Laws | Firearms and Violence: A Critical Review | The National Academies Press. 2004. doi:10.17226/10881. ISBN 978-0-309-09124-4.

- Winkler, Adam (September 2011). Gunfight: The Battle Over the Right to Bear Arms in America. W. W. Norton. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-393-08229-6.

- Winkler, Adam (September 2011). Gunfight: The Battle Over the Right to Bear Arms in America. W. W. Norton. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-393-08229-6.

- Wilson, Harry L. (May 2012). "Concealed Weapons Laws". In Carter, Gregg Lee (ed.). Guns in American Society: An Encyclopedia of History, Politics, Culture, and the Law (Second ed.). Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-313-38671-8.

- "Do You Have A Duty To Inform When Carrying Concealed? We Look At All 50 States For The Answers". Concealed Nation. Retrieved 2017-07-04.

- "CCW Disclosure". Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- "2012 Florida Statutes, Title XLVI Crimes, Chapter 790 Weapons and Firearms, 790.01 Carrying concealed weapons". 2012.

790.01 Carrying concealed weapons. – (1) Except as provided in subsection (4), a person who carries a concealed weapon or electric weapon or device on or about his or her person commits a misdemeanor of the first degree, punishable as provided in s. 775.082 or s. 775.083. (2) A person who carries a concealed firearm on or about his or her person commits a felony of the third degree, punishable as provided in s. 775.082, s. 775.083, or s. 775.084. (3) This section does not apply to a person licensed to carry a concealed weapon or a concealed firearm pursuant to the provisions of s. 790.06. (4) It is not a violation of this section for a person to carry for purposes of lawful self-defense, in a concealed manner: (a) A self-defense chemical spray. (b) A nonlethal stun gun dart-firing stun gun or other nonlethal electric weapon or device that is designed solely for defensive purposes. (5) This section does not preclude any prosecution for the use of an electric weapon or device, a dart-firing stun gun, or a self-defense chemical spray during the commission of any criminal offense under s. 790.07, s. 790.10, s. 790.23, or s. 790.235, or for any other criminal offense.

- "2012 Florida Statutes, Title XLVI Crimes, Chapter 790 Weapons and Firearms, 790.001 Definitions". 2012.

(3)(a) "Concealed weapon" means any dirk, metallic knuckles, slungshot, billie, tear gas gun, chemical weapon or device, or other deadly weapon carried on or about a person in such a manner as to conceal the weapon from the ordinary sight of another person. (b) "Tear gas gun" or "chemical weapon or device" means any weapon of such nature, except a device known as a "self-defense chemical spray." "Self-defense chemical spray" means a device carried solely for purposes of lawful self-defense that is compact in size, designed to be carried on or about the person, and contains not more than two ounces of chemical.

- Lott, John R. (2021-10-11). "Concealed Carry Permit Holders Across the United States: 2021". SSRN. Rochester, NY. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3937627. SSRN 3937627.

- Kranz, Steven W. (2006). "A Survey of State Conceal And Carry Statutes: Can Small Changes Help Reduce the Controversy?". Hamline Law Review. 29 (638).

- ^ "Permits / Licenses That Each State Honors" (PDF). Handgunlaw.us. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- "Gun laws in Arkansas" (PDF). Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- "A.C.A. § 5-73-321. Recognition of other states' licenses". 2013.

- "CA attorney General Legal Alert" (PDF).

- Dejean, Ashley (October 3, 2017) – "Just Days After Las Vegas, Gun Laws in the Nation’s Capitol Are About to Get Weaker" Mother Jones. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- Matanane, Sabrina Salas (May 28, 2014) – "Governor Signs 12 Bills, Vetoes 2" Kuam News. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- "People v. Bruner – 1996 – Illinois Appellate Court, Fourth District Decisions". Justia. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- "Docket No. 106367 – People v. Diggins" (PDF). Illinois Courts. October 8, 2009. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- Higgins, Michael (November 28, 2000). "Owners Say Law Lets Them Tote Guns in Fanny Packs". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- Gregory, Ted (June 3, 2004). "Dupage Pays for Handgun Arrest". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- "Gun-Rights Advocates Win Victory in Chicago Court". The Crime Report. May 18, 2004. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- McCune, Greg (July 9, 2013). "Illinois Is Last State to Allow Concealed Carry of Guns", Reuters. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- Jones, Ashby (July 9, 2013). "Illinois Abolishes Ban on Carrying Concealed Weapons", Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- McDermott, Kevin, and Hampel, Paul (July 11, 2013). "Illinois Concealed Carry Now on the Books – But Not Yet in the Holster", St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- DeFiglio, Pam (July 9, 2013). "General Assembly Overrides Veto, Legalizing Concealed Carry in Illinois", Patch Media. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- "Illinois" (PDF). Handgunlaw.us. March 3, 2018. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- "§724.11A. Recognitions" (PDF). 2017.

- NRA-ILA. "NRA-ILA | Maryland Gun Laws". NRA-ILA. Retrieved 2017-10-07.

- "States with strict gun-permitting laws consider next steps". AP News. 23 June 2022. Retrieved 2022-06-23.

- Howe, Amy (23 June 2022). "In 6-3 ruling, court strikes down New York's concealed-carry law". SCOTUSblog. Retrieved 2022-06-23.

- "North Carolina shall-issue laws" (PDF). Jus.state.nc.us. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-26. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- "166.291: Issuance of concealed handgun license".

The sheriff of a county, upon a person's application for an Oregon concealed handgun license, upon receipt of the appropriate fees and after compliance with the procedures set out in this section, shall issue the person a concealed handgun license

- "V.I.C Title 23 Chpt. 5 § 460. Reciprocal recognition of out-of-state licenses". 1968.

- Concealed Handgun Permit Firearms Safety Class – Virginia Concealed Handgun Permit. vaguntraining.com. Retrieved on 2014-04-15.

- "Firearms FAQ | Washington State". www.atg.wa.gov. Retrieved September 16, 2021.

- "Acknowledging domestic terror threat, Pentagon says troops, recruiters can carry concealed guns". Military Times. 21 November 2016. Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- Robert J., Spitzer (19 June 2016). "Even in the Wild West, there were rules about carrying concealed weapons". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- Joe, Eaton; Chad D., Baus. "Ohio Gun Rights Timeline". Buckeye Firearms Association. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- "Article 400 | NYS Penal Law | Licensing Provisions Firearms". ypdcrime.com. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- New York State firearm law table, "Carry Permit" row

- ^ Virginia State Police, application for a concealed handgun permit page. Vsp.state.va.us. Retrieved on 2011-10-16.

- "Florida Statute 790". Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- "Concealed Carry (CCW) Laws by State on". Usacarry.com. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- State of Washington reciprocity Archived 2011-06-06 at the Wayback Machine. Atg.wa.gov. Retrieved on 2011-10-16.

- "Idaho Enhanced Concealed Carry Permit Recognition". ConcealedCarry.com. 23 March 2015. Retrieved 2016-03-10.

- "Concealed Carry Reciprocity and Recognition Map". ConcealedCarry.com. 23 March 2015. Retrieved 2016-03-10.

- "Concealed Carry Mobile Applications". ConcealedCarry.com. 31 October 2014. Retrieved 2016-03-10.

- "Ohio's Concealed Carry Laws and License Application" (PDF). p. 12. Retrieved 2014-05-30.

- "Chapter 624, Section 714, Subdivision 17". Minnesota Statutes. Minnesota Revisor of Statutes. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- "Nebraska Revised Statute 69-2441". Nebraska Statutes. Nebraska Legislature. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- Hetzner, Amy (2011–2012). "Where Angels Tread: Gun-Free School Zone Laws and an Individual Right to Bear Arms". Marquette Law Review. 95: 359–98.

- "Brandishing a Weapon, Gun or Firearm". Retrieved 2014-02-19.

- "Code of Virginia 18.2-282". Archived from the original on 2000-04-13. Retrieved 2014-02-19.

- "Title 36 CFR §327.13". Ecfr.gpoaccess.gov. Archived from the original on 2011-06-12. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- National Parks Gun Law Takes Effect in February Washington Post, May 22, 2009.

- Judge Blocks Rule Permitting Concealed Guns In U.S. Parks Washington Post, March 20, 2009.

- "Copy of Injunction" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-04-07. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- "Greenspace". The Los Angeles Times. May 20, 2009.

- Constitution for the United States of America, Article IV, Section 1: "Full faith and credit shall be given in each state to the public acts, records, and judicial proceedings of every other state. And the Congress may by general laws prescribe the manner in which such acts, records, and proceedings shall be proved, and the effect thereof."

- Tennessee reciprocity policy Archived 2016-04-12 at the Wayback Machine "Tennessee now recognizes a facially valid handgun permit, firearms permit, weapons permit, or a license issued by another state according to its terms..."

- "House Bill 38". congress.gov. 2017.

- "Robertson v. Baldwin:: 165 U.S. 275 (1897)". Justia U.S. Supreme Court Center.

- Carter, Gregg Lee (2002). Guns in American society: an encyclopedia of history, politics, culture, and the law. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO. p. 506. ISBN 978-1-57607-268-4.

Justice Brown spotlighted his belief that the guarantee of the right to keep and bear arms was not infringed by laws prohibiting the carrying of concealed weapons

- "District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570" (PDF). 2008. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- Leonard W. Levy, Encyclopedia of the American Constitution, Macmillan (1991), article "Strict Scrutiny" by Kenneth L. Karst. "The term 'strict scrutiny' appears to have been used first by Justice William O. Douglas in his opinion for the Supreme Court in Skinner v. Oklahoma (1942), in a context suggesting special judicial solicitude both for certain rights that were 'basic' and for certain persons who seemed the likely victims of legislative prejudice." After a right is identified as a fundamental or basic individual right protected by the Constitution, restrictions on that right are subject to strict scrutiny.

- Gunther, Gerald (1972). "The Supreme Court, 1971 Term, Foreword: In Search of Evolving Doctrine on a Changing Court: A Model for a Newer Equal Protection". Harvard Law Review. 86 (1): 1–48. doi:10.2307/1339852. JSTOR 1339852.

- Barnes, Robert (October 1, 2009). "Justices to Decide if State Gun Laws Violate Rights". The Washington Post.

- "Supreme Court Strikes Down New York Conceal Carry Gun Law". WABC-TV. June 23, 2022. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

California, Hawaii, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey and Rhode Island all have similar laws likely to be challenged as a result of the ruling.

- "California Attorney General Legal Alert OAG-2022-02" (PDF).

- "Hawaii Attorney General Op. No. 22-02" (PDF).

- "Maryland Attorney General Letter to Maryland Department of State Police Licensing Division" (PDF).

- "Joint Advisory Regarding the Massachusetts Firearms Licensing System After the Supreme Court's Decision in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen".

- "New Jersey Attorney General Law Enforcement Directive No. 2022-07" (PDF).

- "Attorney General Neronha issues guidance on concealed-carry permits following SCOTUS decision | Rhode Island Attorney General's Office".

- Swickard, Joe (June 4, 2010). "Charges in stray-bullet death: Carjacking victim faces manslaughter rap". Detroit Free Press. Archived from the original on 2010-06-09.

- "Wayne County judge lessens bond for man accused of killing bystander". The Detroit News. June 28, 2010. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017.

- "Castle Doctrine and Self-Defense". ct.gov.

- "Beard v. United States, 158 U.S. 550 (1897)". Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- Booher, Kary (June 8, 2010). "Case highlights concealed carry weapons issues". Springfield News-Leader. Archived from the original on 2010-06-10.

"Missouri is like 48 other states, except the state of Texas, that does not allow deadly force in defense of property," said Randy Gibson, a captain in the Greene County Sheriff's Department.

- CALCRIM No. 3476

- Cal. Penal Code §197 (West 2013.)

- "80(R) SB 378 - Enrolled version - Bill Text". capitol.texas.gov. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- "2010 Tennessee Code :: Title 39 – Criminal Offenses :: Chapter 17 – Offenses Against Public Health, Safety and Welfare :: Part 13 – Weapons :: 39-17-1307 – Unlawful carrying or possession of a weapon".

- "Article 265 Penal Law Firearms | Dangerous Weapons | NY Law".

- "Sentencing Guidelines for Possession of Weapon in NY". 21 January 2016.

- "New York" (PDF). handgunlaw.us. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- "State Laws and Published Ordinances – New York". atf.gov. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- "New York Gun Laws".

- Gius, Mark (2016-11-03). Guns and Crime: The Data Don't Lie. CRC Press. ISBN 9781315450872. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- Philip J. Cook; Harold A. Pollack (2017). "Reducing Access to Guns by Violent Offenders". RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences. 3 (5): 2. doi:10.7758/rsf.2017.3.5.01. JSTOR 10.7758/rsf.2017.3.5.01.

- Durlauf, Steven N.; Navarro, Salvador; Rivers, David A. (2016-01-01). "Model uncertainty and the effect of shall-issue right-to-carry laws on crime". European Economic Review. Model Uncertainty in Economics. 81 (Supplement C): 32–67. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.696.3159. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2015.07.020. S2CID 1575410.

- Kessler, Glenn (2012-12-17). "Do concealed weapon laws result in less crime?". Washington Post. Retrieved 2017-12-03.

- ^ Cook, Philip J.; Donohue, John J. (7 December 2017). "Saving lives by regulating guns: Evidence for policy". Science. 358 (6368): 1259–1261. Bibcode:2017Sci...358.1259C. doi:10.1126/science.aar3067. PMID 29217559. S2CID 206665567.

- "The Effects of Concealed-Carry Laws". rand.org. Retrieved 2019-12-25.

- Buchanan, Larry; Leatherby, Lauren (June 22, 2022). "Who Stops a 'Bad Guy With a Gun'?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 22, 2022.

Data source: Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training Center

- Anderson, D. Mark; Sabia, Joseph; Tekin, Erdal (2018). "Child Access Prevention Laws and Juvenile Firearm-Related Homicides". National Bureau of Economic Research Working Papers. Cambridge, MA. doi:10.3386/w25209. S2CID 158944952.

- Siegel, Michael; Pahn, Molly; Xuan, Ziming; Fleegler, Eric; Hemenway, David (March 28, 2019). "The Impact of State Firearm Laws on Homicide and Suicide Deaths in the USA, 1991–2016: a Panel Study". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 34 (10): 2021–2028. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-04922-x. PMC 6816623. PMID 30924089.

- Sabbath, Erika L.; Hawkins, Summer Sherburne; Baum, Christopher F. (February 2020). "State-Level Changes in Firearm Laws and Workplace Homicide Rates: United States, 2011 to 2017". American Journal of Public Health. 110 (2): 230–236. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2019.305405. PMC 6951380. PMID 31855477.

- Doucette, Mitchell L.; Crifasi, Cassandra K.; Frattaroli, Shannon (December 2019). "Right-to-Carry Laws and Firearm Workplace Homicides: A Longitudinal Analysis (1992–2017)". American Journal of Public Health. 109 (12): 1747–1753. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2019.305307. PMC 6836804. PMID 31622144.

- Donohue, John J.; Aneja, Abhay; Weber, Kyle D. (15 May 2019). "Right-to-Carry Laws and Violent Crime: A Comprehensive Assessment Using Panel Data and a State-Level Synthetic Control Analysis". Journal of Empirical Legal Studies. 16 (2): 198–247. doi:10.1111/jels.12219. S2CID 181734017.

- Siegel, Michael; Xuan, Ziming; Ross, Craig S.; Galea, Sandro; Kalesan, Bindu; Fleegler, Eric; Goss, Kristin A. (December 2017). "Easiness of Legal Access to Concealed Firearm Permits and Homicide Rates in the United States". American Journal of Public Health. 107 (12): 1923–1929. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.304057. PMC 5678379. PMID 29048964.

- Aneja, A.; Donohue, J. J.; Zhang, A. (29 October 2011). "The Impact of Right-to-Carry Laws and the NRC Report: Lessons for the Empirical Evaluation of Law and Policy". American Law and Economics Review. 13 (2): 565–631. doi:10.1093/aler/ahr009.

- Hamill, Mark E.; Hernandez, Matthew C.; Bailey, Kent R.; Zielinski, Martin D.; Matos, Miguel A.; Schiller, Henry J. (January 2019). "State Level Firearm Concealed-Carry Legislation and Rates of Homicide and Other Violent Crime". Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 228 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.08.694. PMID 30359832.

- Mustard, David B.; Lott, John R. (1998-04-17). "Crime, Deterrence, and Right-to-Carry Concealed Handguns". Journal of Legal Studies. SSRN 10129.

- Manski, Charles F.; Pepper, John V. (May 2018). "How Do Right-to-Carry Laws Affect Crime Rates? Coping with Ambiguity Using Bounded-Variation Assumptions" (PDF). The Review of Economics and Statistics. 100 (2): 232–244. doi:10.1162/rest_a_00689. S2CID 43138806.

- Phillips, Charles D.; Nwaiwu, Obioma; Lin, Szu-hsuan; Edwards, Rachel; Imanpour, Sara; Ohsfeldt, Robert (2015). "Concealed Handgun Licensing and Crime in Four States". Journal of Criminology. 2015: 1–8. doi:10.1155/2015/803742.

- "Increasing permits to conceal guns has zero effect on crime, data say". 2015-09-28.

- Gius, Mark (March 2019). "Using the synthetic control method to determine the effects of concealed carry laws on state-level murder rates". International Review of Law and Economics. 57: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.irle.2018.10.005. S2CID 158186157.

- Kovandzic, Tomislav V.; Marvell, Thomas B. (2003). "Right-To-Carry Concealed Handguns and Violent Crime: Crime Control Through Gun Decontrol?". Criminology & Public Policy. 2 (3): 363–396. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9133.2003.tb00002.x.

- Hepburn, Lisa; Miller, Matthew; Azrael, Deborah; Hemenway, David (2004). "The Effect of Nondiscretionary Concealed Weapon Carrying Laws on Homicide". The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 56 (3): 676–681. doi:10.1097/01.TA.0000068996.01096.39. PMID 15128143.

- Phillips, Charles D.; Nwaiwu, Obioma; McMaughan Moudouni, Darcy K.; Edwards, Rachel; Lin, Szu-hsuan (January 2013). "When Concealed Handgun Licensees Break Bad: Criminal Convictions of Concealed Handgun Licensees in Texas, 2001–2009". American Journal of Public Health. 103 (1): 86–91. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300807. PMC 3518334. PMID 23153139.

- Gius, Mark (2019). "The relationship between concealed carry permits and state-level crime rates". Applied Economics Letters. 27 (11): 937–939. doi:10.1080/13504851.2019.1646866. S2CID 199829764.

- Barati, Mehdi (August 2016). "New evidence on the impact of concealed carry weapon laws on crime". International Review of Law and Economics. 47: 76–83. doi:10.1016/j.irle.2016.05.011.

- Devaraj, Srikant; Patel, Pankaj C. (2018). "An examination of the effects of 2014 concealed weapons law in Illinois on property crimes in Chicago". Applied Economics Letters. 25 (16): 1125–1129. doi:10.1080/13504851.2017.1400645. S2CID 158932191.

- Gius, Mark (26 November 2013). "An examination of the effects of concealed weapons laws and assault weapons bans on state-level murder rates". Applied Economics Letters. 21 (4): 265–267. doi:10.1080/13504851.2013.854294. S2CID 154746184.

- Moody, Carlisle E.; Marvell, Thomas B.; Zimmerman, Paul R.; Alemante, Fasil (2014). "The Impact of Right-to-Carry Laws on Crime: An Exercise in Replication". Review of Economics & Finance. 4: 33–43.

- Jeffrey R. Snyder (October 22, 1997). "Cato Institute Policy Analysis No. 284: Fighting Back: Crime, Self-Defense, and the Right to Carry a Handgun" (PDF). Cato Institute.

- Philip J. Cook; Harold A. Pollack (2017). "Reducing Access to Guns by Violent Offenders". RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences. 3 (5): 9. doi:10.7758/rsf.2017.3.5.01. JSTOR 10.7758/rsf.2017.3.5.01.

- Black, Dan A.; Nagin, Daniel S (January 1998). "Do Right-to-Carry Laws Deter Violent Crime?".