| Roger Shepard | |

|---|---|

Shepard at the ASU SciAPP conference in March 2019 Shepard at the ASU SciAPP conference in March 2019 | |

| Born | Roger Newland Shepard (1929-01-30)January 30, 1929 Palo Alto, California, U.S. |

| Died | May 30, 2022 (aged 93) Tucson, Arizona, U.S. |

| Occupation | cognitive scientist |

| Notable work | Shepard elephant, Shepard tones |

Roger Newland Shepard (January 30, 1929 – May 30, 2022) was an American cognitive scientist and author of the "universal law of generalization" (1987). He was considered a father of research on spatial relations. He studied mental rotation, and was an inventor of non-metric multidimensional scaling, a method for representing certain kinds of statistical data in a graphical form that can be comprehended by humans. The optical illusion called Shepard tables and the auditory illusion called Shepard tones are named for him.

Biography

Shepard was born January 30, 1929, in Palo Alto, California. His father was a professor of materials science at Stanford. As a child and teenager, he enjoyed tinkering with old clockworks, building robots, and making models of regular polyhedra.

He attended Stanford as an undergraduate, eventually majoring in psychology and graduating in 1951.

Shepard obtained his Ph.D. in psychology at Yale University in 1955 under Carl Hovland, and completed post-doctoral training with George Armitage Miller at Harvard.

Subsequent to this, Shepard was at Bell Labs and then a professor at Harvard before joining the faculty at Stanford University. Shepard was Ray Lyman Wilbur Professor Emeritus of Social Science at Stanford University.

His students include Lynn Cooper, Leda Cosmides, Rob Fish, Jennifer Freyd, George Furnas, Carol L. Krumhansl, Daniel Levitin, Michael McBeath, and Geoffrey Miller.

In 1997, Shepard was one of the founders of the Kira Institute.

Research

Generalization and mental representation

Main article: Universal law of generalizationShepard began researching mechanisms of generalization while he was still a graduate student at Yale:

I was now convinced that the problem of generalization was the most fundamental problem confronting learning theory. Because we never encounter exactly the same total situation twice, no theory of learning can be complete without a law governing how what is learned in one situation generalizes to another.

Shepard and collaborators "mapped" large sets of stimuli using the rank order of likelihood that a person or organism would generalize the response to Stimulus A and give the same response to Stimulus B. To use an example from Shepard's 1987 paper proposing his "Universal law of generalization": will a bird "generalize" that it can eat a worm slightly different from a previous worm that it found was edible?

Shepard used geometric and spatial metaphors to map a psychological space where "distances" between different stimuli were larger or smaller depending on whether the stimuli were, respectively, less or more similar. These imaginary distances are interesting because they permit mathematical inferences: the "exponential decay" in response to stimuli based on the distance holds valid for a wide range of experiments with human beings and with other organisms.

Non-metric multidimensional scaling

In 1958, Shepard took a job at Bell Labs, whose computer facilities made it possible for him to expand earlier work on generalization. He reports, "This led to the development of the methods now known as non-metric multidimensional scaling – first by me (Shepard, 1962a, 1962b) and then, with improvements, by my Bell Labs mathematical colleague Joseph Kruskal (1964a, 1964b)."

According to the American Psychological Association, "nonmetric multidimensional scaling .. has provided the social sciences with a tool of enormous power for uncovering metric structures from ordinal data on similarities."

Awarding Shepard its Rumelhart Prize in 2006, the Cognitive Science Society called non-metric multidimensional scaling a "highly influential early contribution," explaining that:

This method provided a new means of recovering the internal structure of mental representations from qualitative measures of similarity. This was accomplished without making any assumptions about the absolute quantitative validity of the data, but solely based on the assumption of a reproducible ordering of the similarity judgements.

Mental rotation

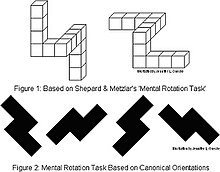

Inspired by a dream of three-dimensional objects rotating in space, Shepard began in 1968 to design experiments to measure mental rotation. (Mental rotation involves "imagining how a two- or three-dimensional object would look if rotated away from its original upright position.")

The early experiments, in collaboration with Jacqueline Metzler, used perspective drawings of very abstract objects: "ten solid cubes attached face-to-face to form a rigid armlike structure with exactly three right-angled 'elbows,'" to quote their 1971 paper, the first report of this research.

Shepard and Metzler were able to measure the speed with which subjects could imagine rotating these complicated objects. Later work by Shepard with Lynn A. Cooper illuminated the process of mental rotation further. Shepard and Cooper also collaborated on a 1982 book (revised 1986) summarizing past work on mental rotation and other transformations of mental images.

Reviewing that work in 1983, Michael Kubovy assessed its importance:

Up to that day in 1968 , mental transformations were no more accessible to psychological experimentation than were any other so-called private experiences. Shepard transformed a compelling and familiar experience into an experimentally tractable problem by injecting it into a problem-task that admits of a correct and incorrect answer.

Optical and auditory illusions

In 1990, Shepard published a collection of his drawings called Mind Sights: Original visual illusions, ambiguities, and other anomalies, with a commentary on the play of mind in perception and art. One of these illusions ("Turning the tables," p. 48) has been widely discussed and studied as the "Shepard tabletop illusion" or "Shepard tables." Others, such as the figure-ground confusing elephant he calls "L'egs-istential quandary" (p. 79) are also widely known.

Shepard is also noted for his invention of the musical illusion known as Shepard tones. He began his research on auditory illusions during his years at Bell Labs, where his colleague Max Mathews was experimenting with computerized music synthesis (Mind Sights, page 30.) Shepard tones give an illusion of constantly increasing pitch. Musicians and sound-effect designers use Shepard tones to create some special effects.

Recognition

The Review of General Psychology named Shepard as one of the most "eminent psychologists of the 20th century" (55th on a list of 99 names, published in 2002). Rankings for the list were based on journal citations, elementary textbook mentions, and nominations by members of the American Psychological Society.

Shepard was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1977 and to the American Philosophical Society in 1999. In 1995, he received the National Medal of Science. The citation read:

"For his theoretical and experimental work elucidating the human mind's perception of the physical world and why the human mind has evolved to represent objects as it does; and for giving purpose to the field of cognitive science and demonstrating the value of bringing the insights of many scientific disciplines to bear in scientific problem solving."

In 2006, he won the Rumelhart Prize.

See also

References

- "Remember Roger Newland Shepard Together On Obit". www.joinobit.com. Retrieved June 8, 2022.

- Seckel, Al (2004). Masters of Deception: Escher, Dalí & the Artists of Optical Illusion. Sterling Publishing Company. p. 285. ISBN 978-1-4027-0577-9.

Roger Shepard was born in Palo Alto, California. His father, a professor in materials science at Stanford, greatly encouraged and stimulated his son's interest in science…

- ^ Shepard, Roger (2004). "How a cognitive psychologist came to seek universal laws" (PDF). Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 11 (1): 1–23. doi:10.3758/BF03206455. PMID 15116981. S2CID 39226280. Retrieved February 5, 2019.

I was now convinced that the problem of generalization was the most fundamental problem confronting learning theory. Because we never encounter exactly the same total situation twice, no theory of learning can be complete without a law governing how what is learned in one situation generalizes to another."

- "University of California Hitchcock Lectures". UCSB. 1999. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

Shepard graduated from Stanford in 1951, and received his doctorate from Yale. He then held positions at Bell Labs and at Harvard University before going to Stanford, where he has been a member of the faculty for over 30 years.

- Shepard, Roger N. (1955). "STIMULUS AND RESPONSE GENERALIZATION DURING PAIRED-ASSOCIATES LEARNING". ProQuest. ProQuest 301995049. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- Pinker, Steven (2013). "George A. Miller (1920–2012)" (PDF). American Psychologist. 68 (6): 467–468. doi:10.1037/a0032874. PMID 24016117. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- ^ "2006 Recipient: Roger Shepard". Cognitive Science Society. 2006. Retrieved February 5, 2019.

Roger N. Shepard is a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and is the William James Fellow of the American Psychological Association. In 1977 he was elected to the National Academy of Sciences. In 1995 he received United States' highest scientific award, the National Medal of Science.

- "Roger Newland Shepard". Neurotree. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- History of Kira Institute

- Shepard, RN (September 11, 1987). "Toward a universal law of generalization for psychological science". Science. 237 (4820): 1317–1323. Bibcode:1987Sci...237.1317S. doi:10.1126/science.3629243. PMID 3629243.

A psychological space is established for any set of stimuli by determining metric distances between the stimuli such that the probability that a response learned to any stimulus will generalize to any other is an invariant monotonic function of the distance between them. To a good approximation, this probability of generalization (i) decays exponentially with this distance, and (ii) does so in accordance with one of two metrics, depending on the relation between the dimensions along which the stimuli vary.

- Jones, Matt; Zhang, Jun (December 22, 2016). "Duality Between Feature and Similarity Models, Based on the Reproducing-Kernel Hilbert Space" (PDF). University of Colorado. S2CID 34620390. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 13, 2021.

Shepard's (1957, 1987) influential model of similarity and generalization holds that stimuli are represented in a multidimensional Cartesian space, x = (x1, . . . , xm) and that similarity is an exponential function of distance in that space

- "What your cell phone camera tells you about your brain". ScienceDaily.com. September 19, 2018. Retrieved February 5, 2019.

A canonical law of cognitive science -- the Universal Law of Generalization, introduced in a 1987 article also published in Science -- tells us that your brain makes perceptual decisions based on how similar the new stimulus is to previous experience. Specifically, the law states that the probability you will extend a past experience to new stimulus depends on the similarity between the two experiences, with an exponential decay in probability as similarity decreases. This empirical pattern has proven correct in hundreds of experiments across species including humans, pigeons, and even honeybees.

- No Authorship Indicated (1977). "Roger N. Shepard: Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award". American Psychologist. 32 (1`): 62–67. doi:10.1037/h0078482.

Recognizes the receipt of the American Psychological Association's 1976 Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award by Roger N. Shepard. The award citation reads: 'For his pioneering work in cognitive structures, especially his invention of nonmetric multidimensional scaling, which has provided the social sciences with a tool of enormous power for uncovering metric structures from ordinal data on similarities. In addition, his novel studies in recognition memory and pitch perception, and his latest innovative work on mental rotations--operations that may well underlie our ability to read and to recognize objects--have all contributed materially to our understanding of cognitive processes. His style of research exhibits a beautiful combination of depth and simplicity.'

- Kaltner, Sandra; Jansen, Petra (2016). "Developmental Changes in Mental Rotation: A Dissociation Between Object-Based and Egocentric Transformations". Adv Cog Psych. 12 (2): 67–78. doi:10.5709/acp-0187-y. PMC 4974058. PMID 27512525.

Mental rotation (MR) is a specific visuo-spatial ability which involves the process of imagining how a two- or three-dimensional object would look if rotated away from its original upright position (Shepard & Metzler, 1971). In the classic paradigm of Cooper and Shepard (1973) two stimuli are presented simultaneously next to each other on a screen and the participant has to decide as fast and accurately as possible if the right stimulus, presented under a certain angle of rotation, is the same or a mirror-reversed image of the left stimulus, the so called comparison figure.

- Shepard, RN; Metzler, J (1971). "Mental rotation of three-dimensional objects". Science. 171 (3972): 701–703. Bibcode:1971Sci...171..701S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.610.4345. doi:10.1126/science.171.3972.701. PMID 5540314. S2CID 16357397.

Each object consisted of ten solid cubes attached face-to-face to form a rigid armlike structure with exactly three right-angled "elbows"

- Shepard, Shenna; Metzler, Douglas (1988). "Mental Rotation: Effects of Dimensionality of Objects and Type of Task" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Psychology. 14 (1): 3–11. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.14.1.3. PMID 2964504. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

The initial studies of mental rotation were of two types: (a) those by Roger Shepard and Jacqueline Metzler using perspective views of three-dimensional objects and measuring the time to determine whether two simultaneously presented objects, though differing in their orientations, were of the same three-dimensional shape (J. Metzler. 1973; J. Metzler & R. Shepard, 1974; R. Shepard & J. Metzler, 1971) and (b) those by Lynn Cooper and her associates (including R. Shepard) using two-dimensional shapes (alphanumeric characters or random polygons) and measuring the time to determine whether a single object, though differing in orientation from a previously learned object, had the same intrinsic shape as that previously learned object (Cooper, 1975, 1976; Cooper & Podgorny, 1976; Cooper & R. Shepard, 1973).

- Shepard, RN; Cooper, L (1982). Mental Images and their Transformations. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-69099-7.

- Kubovy, Michael (1983). "Mental Imagery Majestically Transforming Cognitive Psychology". Contemporary Psychology: A Journal of Reviews. 28 (9): 661–663. doi:10.1037/022300. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

Up to that day in 1968, mental transformations were no more accessible to psychological experimentation than were any other so-called private experiences. Shepard transformed a compelling and familiar experience into an experimentally tractable problem by injecting it into a problem-task that admits of a correct and incorrect answer (this problem is discussed in some depth by Pomerantz & Kubovy, 1981, pp. 426-427). I do not wish to claim that this methodological insight had no precursors, only that in this case its application had far-reaching consequences for the purview of cognitive psychology.

- Shepard, RN (1990). Mind Sights: Original visual illusions, ambiguities, and other anomalies, with a commentary on the play of mind in perception and art. W.H. Freeman and Company. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-7167-2134-5.

Visual illusions, ambiguous figures, and depictions of impossible objects are inherently fascinating. Their violations of our most ingrained and immediate interpretations of external reality grab us at a deep, unarticulated level.

- Gifford, Clive (November 17, 2014). "The best optical illusions to bend your eyes and blow your mind – in pictures". The Guardian. Retrieved February 5, 2019.

Famous impossible images include the Penrose staircase and this little beauty, courtesy of renowned cognitive scientist and author of Mind Sights, Roger Newland Shepard. With his usual love of a quick joke, Shepard entitled the illusion L'egs-istential Quandary. It is impossible to isolate the elephant's legs from the background.

- Stephin Merritt: Two Days, 'A Million Faces' (video). NPR. November 4, 2007. Retrieved October 9, 2015.

It turns out I was thinking about a Shepard tone, the illusion of ever-ascending pitches.

- Haubursin, Christopher (July 26, 2017). "The sound illusion that makes Dunkirk so intense". Vox. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

Named after cognitive scientist Roger Shepard, the sound consists of several tones separated by an octave layered on top of each other. As the lowest bass tone starts to fade in, the higher treble tone fades out. When the bass completely fades in and the treble completely fades out, the sequence loops back again. Because you can always hear at least two tones rising in pitch at the same time, your brain gets tricked into thinking that the sound is constantly ascending in pitch. It's a creepy, anxiety-inducing sound.

- King, Richard (February 4, 2009). "'The Dark Knight' sound effects". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

I used the concept of the Shepard tone to make the sound appear to continually rise in pitch. The basic idea is to slightly overlap a sound with a distinct pitch (a large A/C electric motor, in this case) in different octaves. When played on a keyboard, it gives the illusion of greater and greater speed; the pod appears unstoppable.

- Haggbloom, Steven J.; Warnick, Renee; Warnick, Jason E.; Jones, Vinessa K.; Yarbrough, Gary L.; Russell, Tenea M.; Borecky, Chris M.; McGahhey, Reagan; et al. (2002). "The 100 most eminent psychologists of the 20th century". Review of General Psychology. 6 (2): 139–152. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.6.2.139. S2CID 145668721.

- "Study ranks the top 20th century psychologists". APA Monitor. 2002. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

The rankings were based on the frequency of three variables: journal citation, introductory psychology textbook citation and survey response. Surveys were sent to 1,725 members of the American Psychological Society, asking them to list the top psychologists of the century.

- "Roger N Shepard". National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved February 5, 2019.

Election Year: 1977

- "American Philosophical Society Member History". American Philosophical Society. Retrieved February 5, 2019.

He is the recipient of the James McKeen Cattell Fund Award, the Howard Crosby Warren Medal from the Society of Experimental Psychologists, the Award in the Behavioral Sciences from the New York Academy of Sciences, the Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award of the American Psychological Association, the Gold Medal Award for Life Achievement in the Science of Psychology from the American Psychological Foundation, the Wilbur Lucius Cross medal of the Yale Graduate School Alumni Association, the Rumelhart Prize in Cognitive Science, and the National Medal of Science. He has also received honorary degrees from Harvard, Rutgers, and the University of Arizona.

- "The President's National Medal of Science: Recipient Details Roger N. Shepard". National Science Foundation. 2005. Retrieved February 5, 2019.

For his theoretical and experimental work elucidating the human mind's perception of the physical world and why the human mind has evolved to represent objects as it does; and for giving purpose to the field of cognitive science and demonstrating the value of bringing the insights of many scientific disciplines to bear in scientific problem solving.

External links

- Stanford University web page

- Research Biography of Roger Shepard

- University of California Hitchcock Lectures

- Biography at rr0.org (in French)

| Music psychology | |

|---|---|

| Areas | |

| Topics |

|

| Disorders | |

| Related fields |

|

| Researchers |

|

| Books and journals | |

| Evolutionary psychologists | |

|---|---|

| Evolutionary psychology | |

| Biologists / neuroscientists |

|

| Anthropologists | |

| Psychologists / cognitive scientists |

|

| Other social scientists | |

| Literary theorists / philosophers | |

| Research centers/ organizations | |

| Publications | |

- 1929 births

- 2022 deaths

- American cognitive scientists

- National Medal of Science laureates

- American music psychologists

- Stanford University Department of Psychology faculty

- Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences

- Scientists from California

- Rumelhart Prize laureates

- Fellows of the Cognitive Science Society

- Scientists at Bell Labs

- Members of the American Philosophical Society

- APA Distinguished Scientific Award for an Early Career Contribution to Psychology recipients