| Mission San Juan Capistrano | |

|---|---|

| La Misión de San Juan Capistrano | |

The church of Mission San Juan Capistrano and its integral campanario The church of Mission San Juan Capistrano and its integral campanario | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholic |

| Location | |

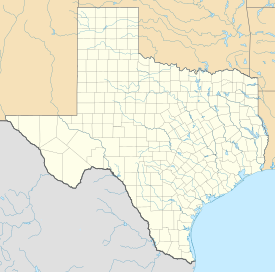

| Location | San Antonio, Texas |

| |

| Geographic coordinates | 29°19′58″N 98°27′19″W / 29.332687°N 98.455289°W / 29.332687; -98.455289 |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Spanish Colonial |

| Completed | Founded 1731 |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii) |

| Designated | 2015 (39th session) |

| Parent listing | San Antonio Missions |

| Reference no. | 1466-002 |

| State Party | |

| Region | Europe and North America |

| U.S. National Register of Historic Places | |

| Designated | February 23, 1972 |

| Reference no. | 72001352 |

Mission San Juan Capistrano (originally christened in 1716 as La Misión San José de los Nazonis and located in South Central Texas) was founded in 1731 by Spanish Catholics of the Franciscan Order, on the eastern banks of the San Antonio River in present-day San Antonio, Texas. The new settlement (part of a chain of Spanish missions) was named for a 15th-century theologian and warrior priest who resided in the Abruzzo region of Italy. The mission San Juan was named after Saint John of Capestrano.

Mission

The first primitive capilla (chapel) was built out of brush and mud. Eventually a campanile, or "bell tower" containing two bells was incorporated into the structure, which was replaced by a long granary with a flat roof and an attractive belfry around 1756. Around 1760, construction of a larger church building begun on the east side of the Mission compound, but was never completed due to the lack of sufficient labor. Mission San Juan did not prosper to the same extent as the other San Antonio missions because lands allotted to it were not sufficient to plant vast quantities of crops, or breed large numbers of horses and cattle; a dam was constructed in order to supply water to the Mission's acequia, or irrigation system. (the Mission reportedly owned 1,000 head of cattle, 3,500 sheep and goats, and 100 horses in 1762).

Some 265 neophytes resided in adobe huts at the Mission in 1756; by 1790 the native Coahuiltecan people were living in stone quarters, though their number had dropped to 58. The Mission often encountered systemic issues concerning corralling the native's nomadic tendencies, which consequently led to large amounts of the converted Indians to sporadically leave. San Juan Capistrano was administered by the College of Santa Cruz de Querétaro until March 1773, when it was placed under the care of the College of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de Zacatecas.

Secularization

The mission was secularized on July 14, 1794, after which time it was attended by the resident priest at Mission San Francisco de la Espada, until about 1813; it was then attended by the one remaining missionary at the nearby Mission San José y San Miguel de Aguayo until 1824. The native population of the Mission were either disbanded, temporarily moved to other missions, or Hispanicized. Mission San Juan was largely neglected until 1840, when religious services were once again conducted, this time by diocesan priests. A neighborhood around the Mission, partially inhabited by the descendants of the Missions population, steadily grew in part due to the construction of a railroad nearby in 1855. Members of the Claretian and Redemptorist Orders also held mass in the church until 1967, when the Franciscans returned to Mission San Juan.

Theft of three altar statues

Three Spanish Colonial-period statues that sat at the altar were stolen sometime on the night of Monday, July 31 or early the morning of Tuesday, August 1, 2000. The statues are between 3–4 feet tall and are constructed of carved wood that had been painted. They are considered priceless due to their religious and historical significance.

San Antonio Missions National Historical Park

As part of a public works project in 1934 some of the native quarters and the foundations of the unfinished church were unearthed. The church, priests' quarters, and other structures were reconstructed during the 1960s. Most of the original square remains within the courtyard walls, portraying an authentic depiction of the floor plan and layout. The grounds of Mission San Juan Capistrano has been maintained by the National Park Service as a part of the San Antonio Missions National Historical Park since the 1980s, and the Archdiocese of San Antonio maintains the church building, parish parking lot, rectory (priest's quarters), and the parish hall (Slattery Hall). The hall is located across Villamain Road from the mission but is still inside the park boundary.

2012 renovation

A $2.2 million renovation in 2012 stabilized the foundation of the mission's church. The shifting clay soil beneath the building had caused severe cracks and falling plaster. A pier-and-beam foundation was added that extends around the perimeter and as far as 29 feet deep into the ground. This allowed buttresses placed against walls in the mid-20th century to be removed. Eggshell white color lime plaster now covers the exterior in contrast to its longstanding dark, weathered look.

Gallery

-

Full view of the church in 1892.

Full view of the church in 1892.

-

Full view of the church before the 2012 renovations.

-

Full view of the church after the 2012 renovations.

Full view of the church after the 2012 renovations.

-

View of the grounds around the church in 2017.

View of the grounds around the church in 2017.

-

Tierra Sagrada "Sacred Earth" at the site of an unfinished church from 1780, where indigenous people who built the mission were buried.

-

Interior of the church before the 2012 renovations.

-

Mission San Juan de Capistrano by Hermann Lungkwitz

Mission San Juan de Capistrano by Hermann Lungkwitz

See also

- List of the oldest buildings in Texas

- Spanish missions in Texas

- Mission Nuestra Señora de la Purísima Concepción de Acuña - also called Mission Concepcion

- Mission San José y San Miguel de Aguayo - also called Mission San José

- Mission San Francisco de la Espada - also called Mission Espada

- Espada Acequia

References

- Torres, Luis (1992). San Antonio Missions National Historical Park. Western National Parks Association. p. 26.

- Thoms, Alston V. (1992). "Reassessing Cultural Extinction: Change and Survival at Mission San Juan Capistrano". Retrieved December 2, 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Fisher, Lewis F. (1998). The Spanish Missions of San Antonio. San Antonio, TX: Maverick. p. 21.

- Levy, Abe (February 25, 2013). "Mission San Juan shows off facelift". MySA. Hearst Newspapers, LLC. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

External links

| Spanish missions of the Catholic Church in the Americas | |

|---|---|

| North America | |

| South America | |

| Related topics | |

| Spanish Texas | |

|---|---|

| Early Texas Settlements | |

| Spanish missions in Texas | |

| Spanish forts of Texas | |

| Armed conflicts | |

| Empresarios | |

| Monarchs and Viceroys | |

| Governors | |

| Municipal government | |

- Spanish missions in Texas

- San Antonio Missions National Historical Park

- San Antonio Missions (World Heritage Site)

- Buildings and structures in San Antonio

- Roman Catholic churches completed in the 1730s

- History of San Antonio

- National Register of Historic Places in San Antonio

- Properties of religious function on the National Register of Historic Places in Texas

- Archaeological sites in Texas

- 1731 establishments in Texas

- Spanish Colonial architecture in Texas

- 18th-century Roman Catholic church buildings in the United States