Medical condition

| Schizoid personality disorder | |

|---|---|

| |

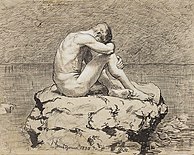

| People with schizoid personality disorder often prefer solitary activities. | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, clinical psychology |

| Symptoms | Pervasive emotional detachment, reduced affect, lack of close friends, apathy, anhedonia, unintentional insensitivity to social norms, sexual abstinence, preoccupation with fantasy, autistic thinking without loss of skill to recognize reality |

| Usual onset | Late childhood or adolescence |

| Duration | Lifelong |

| Types | Languid schizoid, remote schizoid, depersonalized schizoid, affectless schizoid (Millon's subtypes) |

| Causes | Family history; cold, indifferent, or intrusive parenting; traumatic brain injury; low birth weight; prenatal malnutrition |

| Risk factors | Family history |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms |

| Differential diagnosis | Other mental disorders with psychotic symptoms (schizophrenia, delusional disorder, and a bipolar or depressive disorder with psychotic features), personality change due to another medical condition, substance use disorders, autism spectrum disorder, other personality disorders and personality traits (such as introversion) |

| Treatment | Psychodynamic psychotherapy; cognitive behavioral therapy |

| Medication | Not general practice but may include low dose benzodiazepines, β-blockers, nefazodone, bupropion |

| Prognosis | Typically poor |

| Frequency | 0.8% |

| Personality disorders |

|---|

| Cluster A (odd) |

| Cluster B (dramatic) |

| Cluster C (anxious) |

| Not otherwise specified |

| Depressive |

| Others |

Schizoid personality disorder (/ˈskɪtsɔɪd, ˈskɪdzɔɪd, ˈskɪzɔɪd/, often abbreviated as SzPD or ScPD) is a personality disorder characterized by a lack of interest in social relationships, a tendency toward a solitary or sheltered lifestyle, secretiveness, emotional coldness, detachment, and apathy. Affected individuals may be unable to form intimate attachments to others and simultaneously possess a rich and elaborate but exclusively internal fantasy world. Other associated features include stilted speech, a lack of deriving enjoyment from most activities, feeling as though one is an "observer" rather than a participant in life, an inability to tolerate emotional expectations of others, apparent indifference when praised or criticized, all forms of asexuality, and idiosyncratic moral or political beliefs.

Symptoms typically start in late childhood or adolescence. The cause of SzPD is uncertain, but there is some evidence of links and shared genetic risk between SzPD, other cluster A personality disorders, and schizophrenia. Thus, SzPD is considered to be a "schizophrenia-like personality disorder". It is diagnosed by clinical observation, and it can be very difficult to distinguish SzPD from other mental disorders or conditions (such as autism spectrum disorder, with which it may sometimes overlap).

The effectiveness of psychotherapeutic and pharmacological treatments for the disorder has yet to be empirically and systematically investigated. This is largely because people with SzPD rarely seek treatment for their condition. Originally, low doses of atypical antipsychotics were used to treat some symptoms of SzPD, but their use is no longer recommended. The substituted amphetamine bupropion may be used to treat associated anhedonia. However, it is not general practice to treat SzPD with medications, other than for the short-term treatment of acute co-occurring disorders (e.g. depression). Talk therapies such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) may not be effective, because people with SzPD may have a hard time forming a good working relationship with a therapist.

SzPD is a poorly studied disorder, and there is little clinical data on SzPD because it is rarely encountered in clinical settings. Studies have generally reported a prevalence of less than 1%. It is more commonly diagnosed in males than in females. SzPD is linked to negative outcomes, including a significantly compromised quality of life, reduced overall functioning even after 15 years, and one of the lowest levels of "life success" of all personality disorders (measured as "status, wealth and successful relationships"). Bullying is particularly common towards schizoid individuals. Suicide may be a running mental theme for schizoid individuals, though they are not likely to attempt it. Some symptoms of SzPD (e.g. solitary lifestyle, emotional detachment, loneliness, and impaired communication), however, have been stated as general risk factors for serious suicidal behavior.

History

The term schizoid was coined in 1908 by Eugen Bleuler to describe a human tendency to direct attention toward one's inner life and away from the external world. Bleuler labeled the exaggeration of this tendency the "schizoid personality". He described these personalities as "comfortably dull and at the same time sensitive, people who in a narrow manner pursue vague purposes". In 1910, August Hoch introduced a very similar concept called the "shut-in" personality. Characteristics of it were reticence, reclusiveness, shyness and a preference for living in fantasy worlds, among others. In 1925, Russian psychiatrist Grunya Sukhareva described a "schizoid psychopathy" in a group of children, resembling today's SzPD and ASD. About a decade later Pyotr Gannushkin also included Schizoids and Dreamers in his detailed typology of personality types.

The descriptive tradition began in 1925 with the description of observable schizoid behaviors by Ernst Kretschmer. He organized those into three groups of characteristics:

- Unsociability, quietness, reservedness, seriousness and eccentricity.

- Timidity, shyness with feelings, sensitivity, nervousness, excitability, fondness of nature and books.

- Pliability, kindliness, honesty, indifference, silence and cold emotional attitudes.

These characteristics were the precursors of the DSM-III division of the schizoid character into three distinct personality disorders: schizotypal, avoidant and schizoid. Kretschmer himself, however, did not conceive of separating these behaviors to the point of radical isolation but considered them to be simultaneously present as varying potentials in schizoid individuals. For Kretschmer, the majority of schizoid people are not either oversensitive or cold, but they are oversensitive and cold "at the same time" in quite different relative proportions, with a tendency to move along these dimensions from one behavior to the other.

The second path, that of dynamic psychiatry, began in 1924 with observations by Eugen Bleuler, who observed that the schizoid person and schizoid pathology were not things to be set apart. Ronald Fairbairn's seminal work on the schizoid personality, from which most of what is known today about schizoid phenomena is derived, was presented in 1940. Here, Fairbairn delineated four central schizoid themes:

- The need to regulate interpersonal distance as a central focus of concern.

- The ability to mobilize self-preservative defenses and self-reliance.

- A pervasive tension between the anxiety-laden need for attachment and the defensive need for distance that manifests in observable behavior as indifference.

- An overvaluation of the inner world at the expense of the outer world.

Following Fairbairn's derivation of SzPD from a combination of derealization, depersonalization, splitting, the oral stage of making all subjects into partial objects, and intellectualization; the dynamic psychiatry tradition has continued to produce rich explorations on the schizoid character, most notably from writers Nannarello (1953), Laing (1965), Winnicott (1965), Guntrip (1969), Khan (1974), Akhtar (1987), Seinfeld (1991), Manfield (1992) and Klein (1995).

The DSM-I had the diagnosis of schizoid personality, which was defined by avoidance of close relationships, inability to express aggressive feelings, and autistic thinking (thinking which is preoccupied with one's inner experience). The DSM-II later updated the definition to include daydreaming, detachment from reality, and sensitivity. It was incorporated into the DSM-III as schizoid personality disorder to describe difficulties forming meaningful social relationships and a persistent pattern of disconnection and apathy. The diagnosis of SzPD made it to the DSM-IV and DSM-V.

Epidemiology

It remains unclear how prevalent the disorder is. It may be present in anywhere from 0.5% to 7% of the population and possibly 14% of the homeless population. Gender differences in this disorder are also unclear. Some research has suggested that this disorder may occur more frequently in men than women. SzPD is uncommon in clinical settings (about 2.2%) and occurs more commonly in males. It is rare compared with other personality disorders. Philip Manfield suggests that the "schizoid condition", which roughly includes the DSM schizoid, avoidant and schizotypal personality disorders, is represented by "as many as forty percent of all personality disorders." Manfield adds: "This huge discrepancy is probably largely because someone with a schizoid disorder is less likely to seek treatment than someone with other axis-II disorders." A 2008 study assessing personality and mood disorder prevalence among homeless people at New York City drop-in centers reported an SzPD rate of 65% among this sample. The study did not assess homeless people who did not show up at drop-in centers, and the rates of most other personality and mood disorders within the drop-in centers were lower than that of SzPD. The authors noted the limitations of the study, including the higher male-to-female ratio in the sample and the absence of subjects outside the support system or receiving other support (e.g., shelters) as well as the absence of subjects in geographical settings outside New York City, a large city often considered a magnet for disenfranchised people. A University of Colorado Colorado Springs study comparing personality disorders and Myers–Briggs Type Indicator types found that the disorder had a significant correlation with the Introverted (I) and Thinking (T) preferences.

Etiology

Environmental

Perfectionist and hypercritical parenting or cold, neglectful, and distant parenting contribute to the onset of SzPD. For a person with SzPD, their parents likely were intolerant of their emotional experiences. They may have been forced to repress and compartmentalize their emotions, possibly resulting in the onset of difficulties expressing and processing emotional experiences. These difficulties lead to the child feeling rejected and developing the belief that the only safe environment is one where they are alone and inexpressive. People with SzPD may also have internalized the belief that their emotions are dangerous to themselves and others due to the negative responses received from others. In their status of isolation and emotional bluntness they can be self-sufficient and safe. Childhood trauma can also contribute to feelings of emptiness in adulthood. Alcoholism in parents is associated with a heightened risk of developing SzPD.

Genetic

Sula Wolff, who did extensive research and clinical work with children and teenagers with schizoid symptoms, stated that "schizoid personality has a constitutional, probably genetic, basis." Research on heritability and this disorder is lacking. Twin studies with SzPD traits (e.g., low sociability and low warmth) suggest that these traits are inherited. Besides this indirect evidence, the direct heritability estimates of SzPD range from 50% to 59%. Earlier, less methodologically rigorous research had found the heritability rate to be 29%.

The pathophysiology of SzPD remains unclear. Genetic relationships with people who have schizophrenia spectrum disorders increase the risk of developing schizoid personality disorder. People with SzPD can have a history of schizotypy before developing the disorder. SzPD symptoms can be premorbid to schizophrenia.

Neurological

Prenatal malnutrition, premature birth, and low birth weight are all thought to play a role in the development of SzPD. SzPD is associated with reduced serotonergic and dopaminergic pathways in areas such as the frontal lobe, amygdala, and striatum. Traumatic brain injuries to the frontal lobe may also contribute to the onset of SzPD as that area of the brain controls areas such as emotion and socialization. Deficits in the right hemisphere of the brain may also be associated with SzPD. Lower levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol may be correlated with the presence of schizoid traits in women. Excess indices in the left hemisphere may also be related to SzPD.

Prognosis

Traits of schizoid personality disorder appear in childhood and adolescence. Children with this disorder usually have poor relationships with others, social anxiety, internal fantasies, strange behavior, and hyperactivity. These behaviors can result in teasing and bullying at the hands of others. It is common for people with SzPD to have had major depressive disorder in childhood. SzPD is associated with lower levels of achievement, a compromised quality of life, and a worse outcome of treatment. Treatment for this disorder is under-studied and poorly understood. There is no widely accepted and approved psychotherapy or medication for this disorder. It is one of the most poorly researched psychiatric disorders. Professionals may misunderstand the disorder and the client, potentially reinforcing a feeling of failure and negatively impacting their willingness to continue to commit to treatment. Clinicians tend to worry that they are incapable of properly treating the patient. It is rare for someone with this disorder to voluntarily seek treatment without a comorbid disorder or pressure from family or friends. In treatment, people with SzPD are usually disinterested and often minimize symptoms. Patients with SzPD may fear losing their independence through therapy. Many schizoid individuals will avoid making the efforts required to establish a proper relationship with the therapist. It can be difficult for them to open up or discuss their emotions in therapy. Although people with this disorder can still improve, it is unlikely they will ever experience significant joy through social interaction.

Signs and symptoms

Social isolation

SzPD is associated with a dismissive-avoidant attachment style. People with this disorder will rarely maintain close relationships and often exclusively choose to participate in solitary activities. People with schizoid personality disorder typically have no close friends or confidants, except for a close relative on occasions.

They usually prefer hobbies and activities that do not require interaction with others. People with SzPD may be averse to social situations due to difficulties deriving pleasure from physical or emotional sensations, rather than social anhedonia.

One potential motivation for avoiding social situations is that they feel that it intrudes on their freedom. Relationships can feel suffocating for people with SzPD, and they may think of them as opportunities for entrapment.

Patients with this disorder are often independent and turn to themselves as sources of validation. They tend to be the happiest when in relationships in which their partner places few emotional or intimate demands on them and does not expect phatic or social niceties. It is not necessarily people they want to avoid, but negative or positive emotional expectations, emotional intimacy, and self-disclosure.

Patients with SzPD can feel as if close emotional bonds are dangerous to themselves and others. They may have feelings of inadequacy or shame. Some people with SzPD may experience a deep desire to connect with others, yet will be terrified by the dangers inherent in doing so. Avoidance of social situations may be a method of avoiding being hurt or rejected.

Individuals with SzPD can form relationships with others based on intellectual, physical, familial, occupational, or recreational activities, as long as there is no need for emotional intimacy. Donald Winnicott explains this is because schizoid individuals "prefer to make relationships on their own terms and not in terms of the impulses of other people." Failing to attain that, they prefer isolation.

In general, friendship for schizoid individuals is usually limited to one other person, who is often also schizoid, forming what has been called a union of two eccentrics; "within it – the ecstatic cult of personality, outside it – everything is sharply rejected and despised". Their unique lifestyle can lead to social rejection and people with SzPD are at a higher risk of facing bullying or homelessness. This social rejection can reinforce their asocial behavior.

Sexuality

People with this disorder usually have little to no interest in sexual or romantic relationships. They rarely date or marry. Sex often causes individuals with SzPD to feel that their personal space is being violated, and they commonly feel that masturbation or sexual abstinence is preferable to the emotional closeness they must tolerate when having sex. Significantly broadening this picture are notable exceptions of SzPD individuals who engage in occasional or even frequent sexual activities with others. Individuals with SzPD have long been noted to have an increased rate of unconventional sexual tendencies, though if present, these are rarely acted upon. Schizoid people are often labeled asexual or present with "a lack of sexual identity". Kernberg states that this apparent lack of sexuality does not represent a lack of sexual definition but rather a combination of several strong fixations to cope with the same conflicts. People with SzPD are often able to pursue any fantasies with content on the Internet while remaining completely unengaged with the outside world.

Emotions

See also: Reduced affect displaySensory or emotional experiences typically provide little enjoyment for people with SzPD. They rarely display strong emotions or react to anything. People with SzPD can have difficulty expressing themselves and seem to be directionless or passive. Individuals with SzPD can also experience anhedonia. They can also have difficulty understanding others' emotions and social cues. It can be hard for people with SzPD to assess the impact of their actions in social situations. People with this condition are often indifferent towards criticism or praise and can appear distant, aloof, or uncaring to others. They may avoid others and expressing themselves as a method of keeping others distant and preventing themselves from being hurt. Remaining alone and expressionless can feel safe and comfortable for people with SzPD. Expressing themselves can make them feel shame or discomfort. People with SzPD may feel inadequate and can be sensitive, although they have difficulty expressing it. Alexithymia, or difficulties understanding one's own emotions, is common amongst people with SzPD. This leads to them isolating themselves to avoid the discomfort and stimulation that emotional experiences offer. According to Guntrip, Klein, and others, people with SzPD may possess a hidden sense of superiority and lack dependence on other people's opinions. This is very different from the grandiosity seen in narcissistic personality disorder, which is described as "burdened with envy" and with a desire to destroy or put down others. Additionally, schizoid individuals do not go out of their way to achieve social validation. Unlike narcissists, schizoid people will often keep their creations private to avoid unwelcome attention or the feeling that their ideas and thoughts are being appropriated by the public. When forced to rely on others, a person with SzPD may feel panic or terror.

Feelings of unreality

Patients with SzPD often feel unreal, empty, and separate from their own emotions. They tend to perceive themselves as fundamentally different from others and can believe that they are fundamentally unlikeable. Other people often seem strange and incomprehensible to a person with SzPD. Reality can feel unenjoyable and uninteresting to people with SzPD. They have difficulty finding motivation and lack ambition. Patients with SzPD often feel as if they are "going through the motions" or that "life passes them by." Many describe feeling as if they are observing life from a distance. Aaron Beck and his colleagues report that people with SzPD seem comfortable with their aloof lifestyle and consider themselves observers, rather than participants in the world around them. But they also mention that many of their schizoid patients recognize themselves as socially deviant (or even defective) when confronted with the different lives of ordinary people – especially when they read books or see movies focusing on relationships. Even when schizoid individuals may not long for closeness, they can become weary of being "on the outside, looking in". These feelings may lead to depression, depersonalization, or derealization. If they do, schizoid people often experience feeling "like a robot" or "going through life in a dream". People with SzPD may try to avoid all physical activity in order to become nobody and disconnect from reality. This can lead to the patient spending a large quantity of time sleeping and ignoring bodily functions such as hygiene.

Internal fantasy

See also: Maladaptive daydreamingAlthough this disorder does not affect the patient's capacity to understand reality, they may engage in excessive daydreaming and introspection. Their daydreams can grow to consume most of their lives. Real life can become secondary to their fantasy, and they can have complex lives and relationships which exist entirely inside of their internal fantasy. These daydreams may constitute a defense mechanism to protect the patient from the outside world and its difficulties. Common themes in their internal fantasies are omnipotence and grandiosity. The related schizotypal personality disorder and schizophrenia are reported to have ties to creative thinking, and it is speculated that the internal fantasy aspect of SzPD may also be reflective of this thinking. Alternatively, there has been an especially large contribution of people with schizoid symptoms to science and theoretical areas of knowledge, including mathematics, physics, economics, etc. At the same time, people with SzPD are helpless at many practical activities because of their symptoms.

Suicide and self-harm

Symptoms of SzPD such as isolation and the blunted affect put people with schizoid personality disorder at a higher risk of suicide and non-suicidal self-harm. This may be because their reduced capacities for emotion prevent them from properly dealing with strife. Their solitary nature may contribute by preventing them from finding relief in relationships. Demonstrative suicides or suicide blackmail, as seen in cluster B personality disorders such as borderline, histrionic, or antisocial, are extremely rare among schizoid individuals. As in other clinical mental health settings, among suicidal inpatients, individuals with SzPD are not as well represented as some other groups. A 2011 study on suicidal inpatients at a Moscow hospital found that schizoid individuals were the least common patients, while those with cluster B personality disorders were the most common.

Low weight

A study that looked at the body mass index (BMI) of a sample of both male adolescents diagnosed with SzPD and those diagnosed with Asperger syndrome found that the BMI of all patients was significantly below normal. Clinical records indicated abnormal eating behavior by some patients. Some patients would only eat when alone and refused to eat out. Restrictive diets and fears of disease were also found. It was suggested that the anhedonia of SzPD may also affect eating, leading schizoid individuals to not enjoy it. Alternatively, it was suggested that schizoid individuals may not feel hunger as strongly as others or not respond to it, a certain withdrawal "from themselves".

Substance abuse

Very little data exists for rates of substance use disorder among people with SzPD, but existing studies suggest they are less likely to have substance abuse problems than the general population. One study found that significantly fewer boys with SzPD had alcohol problems than a control group of non-schizoid people. Another study evaluating personality disorder profiles in substance abusers found that substance abusers who showed schizoid symptoms were more likely to abuse one substance rather than many, in contrast to other personality disorders such as borderline, antisocial, or histrionic, which were more likely to abuse many. American psychotherapist Sharon Ekleberry states that the impoverished social connections experienced by people with SzPD limit their exposure to the drug culture and that they have limited inclination to learn how to do illegal drugs. Describing them as "highly resistant to influence", she additionally states that even if they could access illegal drugs, they would be disinclined to use them in public or social settings, and because they would be more likely to use alcohol or cannabis alone than for social disinhibition, they would not be particularly vulnerable to negative consequences in early use. People with SzPD are at a lower risk of substance abuse issues than people with other personality disorders. They may form relationships with their substances as a substitute for human contact or to cope with emotional issues. People with SzPD may desire psychedelic drugs more than other kinds.

Secret schizoids

Many schizoid individuals display an engaging, interactive personality, contradicting the observable characteristic emphasized by the DSM-5 and ICD-10 definitions of the schizoid personality. Guntrip (using ideas of Klein, Fairbairn, and Winnicott) classifies these individuals as "secret schizoids", who behave with socially available, interested, engaged, and involved interaction yet remain emotionally withdrawn and sequestered within the safety of the internal world. Klein distinguishes between a "classic" SzPD and a "secret" SzPD, which occur "just as often" as each other. Klein cautions one should not misidentify the schizoid person as a result of the patient's defensive, compensatory interaction with the external world. He suggests one ask the person what their subjective experience is, to detect the presence of the schizoid refusal of emotional intimacy and preference for objective fact. A 2013 study looking at personality disorders and Internet use found that being online more hours per day predicted signs of SzPD. Additionally, SzPD correlated with lower phone call use and fewer Facebook friends.

Descriptions of the schizoid personality as "hidden" behind an outward appearance of emotional engagement have been recognized since 1940, with Fairbairn's description of "schizoid exhibitionism", in which the schizoid individual can express a great deal of feeling and make what appear to be impressive social contacts yet, in reality, gives nothing and loses nothing. Because they are "playing a part", their personality is not involved. According to Fairbairn, the person disowns the part they are playing, and the schizoid individual seeks to preserve their personality intact and immune from compromise. The schizoid person's false persona is based on what those around them define as normal or good behavior, as a form of compliance. Further references to the secret schizoid come from Masud Khan, Jeffrey Seinfeld, and Philip Manfield. These scholars described secret schizoids as people who enjoy public speaking engagements but experience great difficulty during the breaks when audience members would attempt to engage them emotionally. These references expose the problems in relying on outer observable behavior for assessing the presence of personality disorders in certain individuals.

Comorbid disorders

- Agoraphobia

- Avoidant personality disorder

- Antisocial personality disorder

- Borderline personality disorder

- Post-traumatic stress disorder

- Major depressive disorder

- Generalized anxiety disorder

- Panic disorder

- Paranoid personality disorder

- Social anxiety disorder

- Schizotypal personality disorder

- Obsessive–compulsive disorder

Autism spectrum disorder

Several studies have reported an overlap or comorbidity with autism spectrum disorder and Asperger syndrome. Asperger syndrome had traditionally been called "schizoid disorder of childhood", and Eugen Bleuler coined both the terms "autism" and "schizoid" to describe withdrawal to an internal fantasy, against which any influence from outside becomes an intolerable disturbance. In a 2012 study of a sample of 54 young adults with Asperger syndrome, it was found that 26% of them also met the criteria for SzPD, the highest comorbidity out of any personality disorder in the sample (the other comorbidities were 19% for obsessive–compulsive personality disorder, 13% for avoidant personality disorder and one female with schizotypal personality disorder). Additionally, twice as many men with Asperger syndrome met the criteria for SzPD than women. While 41% of the whole sample were unemployed with no occupation, this rose to 62% for the Asperger's and SzPD comorbid group. Tantam suggested that Asperger syndrome may confer an increased risk of developing SzPD. A 2019 study found that 54% of a group of males aged 11 to 25 with Asperger syndrome showed significant SzPD traits, with 6% meeting full diagnostic criteria for SzPD, compared to 0% of a control group.

In the 2012 study, it was noted that the DSM may complicate diagnosis by requiring the exclusion of a pervasive developmental disorder (PDD) before establishing a diagnosis of SzPD. The study found that social interaction impairments, stereotyped behaviors, and specific interests were more severe in the individuals with Asperger syndrome also fulfilling SzPD criteria, against the notion that social interaction skills are unimpaired in SzPD. The authors believe that a substantial subgroup of people with autism spectrum disorder or PDD have clear "schizoid traits" and correspond largely to the "loners" in Lorna Wing's classification The autism spectrum (Lancet 1997), described by Sula Wolff. The authors of the 2019 study hypothesized that it is extremely likely that historic cohorts of adults diagnosed with SzPD either also had childhood-onset autistic syndromes or were misdiagnosed. They stressed that further research to clarify overlap and distinctions between these two syndromes was strongly warranted, especially given that high-functioning autism spectrum disorders are now recognized in around 1% of the population.

Treatment

Medication

There are no effective medications for schizoid personality disorder. However, certain medications may reduce the symptoms of SzPD and treat co-occurring mental disorders. Since the symptoms of SzPD mirror the negative symptoms of schizophrenia, antipsychotics have been suggested as a potentially effective medication for SzPD. Originally, low doses of atypical antipsychotics like risperidone or olanzapine were used to alleviate social deficits and blunted affect. However, a 2012 review concluded that atypical antipsychotics were ineffective for treating personality disorders. Antidepressants, SSRIs, anxiolitics, bupropion, modafinil, benzodiazepines, and biofeedback may also be effective treatments.

Psychotherapy

Treatment for this disorder uses a combination of cognitive-behavioral therapy and psychodynamic psychotherapy. These techniques can be used to help patients identify their defense mechanisms and change them. Therapists attempt to establish healthy relationships with their clients, helping to combat their internalized belief that relationships are harmful and unhelpful. Relationships with a therapist can seem terrifying and intrusive to a person with SzPD. They may feel as if they need to alter or hide their feelings to meet the therapist's demands or expectations. To combat this, therapists try to gradually increase their patient's emotional expression. Expressing too much too early can lead to their ending therapy. Treatment must be person centered, with clients feeling understood and well regarded. This can allow them to connect with and understand their emotions. When people with SzPD do not have their feelings validated, this will confirm their belief that expressing themselves is dangerous. Therapists attempt to avoid intruding on their patients' lives or restricting their freedoms, so as to prevent them from feeling as if therapy is intolerable. Because of this, therapy is usually less structured than treatment programs for other disorders. Patients may benefit from long-term treatment lasting several years. Inpatient care may be effective for treating SzPD and other Cluster A disorders.

Controversy

The original concept of the schizoid character developed by Ernst Kretschmer in the 1920s comprised a mix of avoidant, schizotypal, and schizoid traits. It was not until 1980 and the work of Theodore Millon that led to splitting this concept into three personality disorders (now schizoid, schizotypal, and avoidant). This caused debate about whether this was accurate or if these traits were different expressions of a single personality disorder. It has also been argued due to the poor consistency and efficiency of diagnosis due to overlapping traits that SzPD should be removed altogether from the DSM. A 2012 article suggested that two different disorders may better represent SzPD: one affect-constricted disorder (belonging to schizotypal PD) and a seclusive disorder (belonging to avoidant PD). They called for the replacement of the SzPD category from future editions of the DSM with a dimensional model which would allow for the description of schizoid traits on an individual basis.

Some critics such as Nancy McWilliams of Rutgers University and Panagiotis Parpottas of European University Cyprus argue that the definition of SzPD is flawed due to cultural bias and that it does not constitute a mental disorder but simply an avoidant attachment style requiring a more distant emotional proximity. If that is true, then many of the more problematic reactions these individuals show in social situations may be partly accounted for by the judgments commonly imposed on people with this style.

Similarly, John Oldham, using a dimensional approach, thinks that most people with schizoid character features do not have a full-blown personality disorder. Impairment is mandatory for any behavior to be diagnosed as a personality disorder.

Diagnosis

Guntrip criteria

Ralph Klein, Clinical Director of the Masterson Institute, delineates the following nine characteristics of the schizoid personality as described by Harry Guntrip:

- Introversion

- Withdrawnness

- Narcissism

- Self-sufficiency

- A sense of superiority

- Loss of affect

- Loneliness

- Depersonalization

- Regression

The description of Guntrip's nine characteristics should clarify some differences between the traditional DSM portrait of SzPD and the traditional informed object relations view. All nine characteristics are consistent. Most, if not all, must be present to diagnose a schizoid disorder.

Millon's subtypes

Theodore Millon restricted the term "schizoid" to those personalities who lack the capacity to form social relationships. He characterizes their way of thinking as being vague and void of thoughts and as sometimes having a "defective perceptual scanning". Because they often do not perceive cues that trigger affective responses, they experience fewer emotional reactions.

For Millon, SzPD is distinguished from other personality disorders in that it is "the personality disorder that lacks a personality." He criticizes that this may be due to the current diagnostic criteria: They describe SzPD only by an absence of certain traits, which results in a "deficit syndrome" or "vacuum". Instead of delineating the presence of something, they mention solely what is lacking. Therefore, it is hard to describe and research such a concept.

He identified four subtypes of SzPD. Any schizoid individual may exhibit none or one of the following:

| Subtype | Features |

|---|---|

| Languid schizoid (including dependent and depressive features) | Marked inertia; deficient activation level; intrinsically phlegmatic, lethargic, weary, leaden, lackadaisical, exhausted, enfeebled. Unable to act with spontaneity or seeks simplest pleasures, may experience profound angst, yet lack the vitality to express it strongly. |

| Remote schizoid (including avoidant features) | Distant and removed; inaccessible, solitary, isolated, homeless, disconnected, secluded, aimlessly drifting; peripherally occupied. Seen among people who would have been otherwise capable of developing normal emotional life but having been subjected to intense hostility lost their innate capability to form bonds. Some residual anxiety is present. |

| Depersonalized schizoid (including schizotypal features) | Disengaged from others and self; self is disembodied or distant object; body and mind sundered, cleaved, dissociated, disjoined, eliminated. Often seen as simply staring into the empty space or being occupied with something substantial while actually being occupied with nothing at all. |

| Affectless schizoid (including compulsive features) | Passionless, unresponsive, unaffectionate, chilly, uncaring, unstirred, spiritless, lackluster, unexcitable, unperturbed, cold; all emotions diminished. Combines the preference for rigid schedule (obsessive–compulsive feature) with the coldness of the schizoid. |

Akhtar's profile

American psychoanalyst Salman Akhtar provided a comprehensive phenomenological profile of SzPD in which classic and contemporary descriptive views are synthesized with psychoanalytic observations. This profile is summarized in the table reproduced below that lists clinical features that involve six areas of psychosocial functioning and are organized by "overt" and "covert" manifestations.

"Overt" and "covert" are intended to denote seemingly contradictory aspects that may both simultaneously be present in an individual. These designations do not necessarily imply their conscious or unconscious existence. The covert characteristics are by definition difficult to discern and not immediately apparent. Additionally, the lack of data on the frequency of many of the features makes their relative diagnostic weight difficult to distinguish at this time. However, Akhtar states that his profile has several advantages over the DSM in terms of maintaining historical continuity of the use of the word schizoid, valuing depth and complexity over descriptive oversimplification and helping provide a more meaningful differential diagnosis of SzPD from other personality disorders.

| Area | Overt characteristics | Covert characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Self-concept |

|

|

| Interpersonal relations |

| |

| Social adaptation |

|

|

| Love and sexuality |

|

|

| Ethics, standards, and ideals |

|

|

| Cognitive style |

|

|

Differential diagnosis

| Psychological condition | Features |

|---|---|

| Other mental disorders with psychotic symptoms | Symptoms of SzPD can appear during the course of disorder with psychotic features such as delusional disorder. However, SzPD does not require the presence of any psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations or delusions. |

| Depression | People who have SzPD may also have clinical depression. However, this is not always the case. Unlike people with depression, persons with SzPD generally do not consider themselves inferior to others. They may recognize instead that they are "different". |

| Autism spectrum disorder | There may be substantial difficulty in distinguishing Asperger syndrome (AS), sometimes called "schizoid disorder of childhood", from SzPD. But while AS is an autism spectrum disorder, SzPD is classified as a "schizophrenia-like" personality disorder. There is some overlap, as some people with autism also qualify for a diagnosis of schizotypal or schizoid PD. However, one of the distinguishing features of schizoid PD is a restricted affect and an impaired capacity for emotional experience and expression. Persons with AS are "hypo-mentalizers", i.e., they fail to recognize social cues such as verbal hints, body language and gesticulation, but those with schizophrenia-like personality disorders tend to be "hyper-mentalizers", overinterpreting such cues in a generally suspicious way. Although they may have been socially isolated from childhood onward, most people with SzPD displayed well-adapted social behavior as children, along with apparently normal emotional function. SzPD also does not require impairments in nonverbal communication such as a lack of eye contact, unusual prosody or a pattern of restricted interests or repetitive behaviors. |

| Personality change due to another medical condition | Traits of SzPD can appear due to damage to the central nervous system. |

| Substance use disorders | Traits of SzPD can appear due to substance abuse. |

| Other personality disorders and personality traits | Schizoid and narcissistic personality disorders can seem similar in some respects (e.g. both show identity confusion, may lack warmth and spontaneity, avoid deep relationships with intimacy). Another commonality observed by Akhtar is preferring ideas over people and displaying "intellectual hypertrophy", with a corresponding lack of rootedness in bodily existence. There are, nonetheless, important differences. A schizoid person hides their need for dependency and is rather fatalistic, passive, cynical, overtly bland or vaguely mysterious. A narcissist is, in contrast, ambitious and competitive and exploits others for their dependency needs. There are also parallels between SzPD and obsessive–compulsive personality disorder (OCPD), such as detachment, restricted emotional expression and rigidity. However, in OCPD the capacity to develop intimate relationships is usually intact, but deep contacts may be avoided because of an unease with emotions and a devotion to work. While people affected with avoidant personality disorder (AvPD) avoid social interactions due to anxiety or feelings of incompetence, those with SzPD do so because they are genuinely indifferent to social relationships. A 1989 study, however, found that "schizoid and avoidant personalities were found to display equivalent levels of anxiety, depression, and psychotic tendencies as compared to psychiatric control patients." There also seems to be some shared genetic risk between SzPD and AvPD (see schizoid avoidant behavior). Several sources have confirmed the synonymy of SzPD and avoidant attachment style. However, the distinction should be made that individuals with SzPD characteristically do not seek social interactions merely due to lack of interest, while those with avoidant attachment style can in fact be interested in interacting with others but without establishing connections of much depth or length due to having little tolerance for any kind of intimacy. |

See also

- Alexithymia

- Asociality

- Cognitive disengagement syndrome

- Counterphobic attitude

- Dissociation (psychology)

- Hermit

- Hikikomori

- Recluse

- Schizothymia

- Schizotypy

- Social disorder

- Social isolation

- Schizoid avoidant behavior

- Schizotypal personality disorder

References

- ^ "F60 Specific personality disorders" (PDF). The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders – Diagnostic criteria for research. Geneva: World Health Organization. p. 149.

- American Psychiatric Association (1968). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (2nd ed.). Washington, D. C. p. 42. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890420355.dsm-ii (inactive 1 November 2024). ISBN 978-0-89042-035-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Esterberg ML, Goulding SM, Walker EF (December 2010). "Cluster A Personality Disorders: Schizotypal, Schizoid and Paranoid Personality Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence". Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 32 (4): 515–528. doi:10.1007/s10862-010-9183-8. PMC 2992453. PMID 21116455.

- ^ Sonny J (1997). "Chapter 3, Schizoid Personality Disorder". Personality Disorders: New Symptom-Focused Drug Therapy. Psychology Press. pp. 45–56. ISBN 978-0-7890-0134-4.

- ^ Emmelkamp P, Kamphuis J (19 December 2013). Personality Disorders. Taylor & Francis (published December 19, 2013). p. 54. ISBN 978-1-317-83477-9.

- ^ Hayward BA (February 2007). "Cluster A personality disorders: considering the 'odd-eccentric' in psychiatric nursing". International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 16 (1): 15–21. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0349.2006.00439.x. PMID 17229270.

- ^ Chadwick PK (May 2014). "Peer-professional first person account: before psychosis--schizoid personality from the inside". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 40 (3): 483–486. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbt182. PMC 3984520. PMID 24353095. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved 2022-09-26.

- ^ Triebwasser J, Chemerinski E, Roussos P, Siever LJ (December 2012). "Schizoid personality disorder". Journal of Personality Disorders. 26 (6): 919–926. doi:10.1521/pedi.2012.26.6.919. PMID 23281676. Archived from the original on June 19, 2022.

- Dierickx S, Dierckx E, Claes L, Rossi G (July 2022). "Measuring Behavioral Inhibition and Behavioral Activation in Older Adults: Construct Validity of the Dutch BIS/BAS Scales". Assessment. 29 (5): 1061–1074. doi:10.1177/10731911211000123. hdl:10067/1775430151162165141. PMID 33736472. S2CID 232302371.

- ^ "Schizoid Personality Disorder". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 2014. Archived from the original on September 14, 2022.

- Reber A, Allen R, Reber E (2009) . The Penguin Dictionary of Psychology (4th ed.). London; New York: Penguin Books. p. 706. ISBN 978-0-14-103024-1. OCLC 288985213.

- ^ Akhtar S (2000-01-01). Broken Structures: Severe Personality Disorders and Their Treatment. Jason Aronson, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-4616-2768-5.

- ^ Kendler KS, Czajkowski N, Tambs K, Torgersen S, Aggen SH, Neale MC, et al. (November 2006). "Dimensional representations of DSM-IV cluster A personality disorders in a population-based sample of Norwegian twins: a multivariate study". Psychological Medicine. 36 (11): 1583–1591. doi:10.1017/S0033291706008609. PMID 16893481. S2CID 21613637. Archived from the original on March 1, 2022.

- Arciniegas DB (2015). "Psychosis". CONTINUUM: Lifelong Learning in Neurology. 21 (3): 715–736. doi:10.1212/01.CON.0000466662.89908.e7. ISSN 1080-2371. PMC 4455840. PMID 26039850. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022.

- Kendler KS, Myers J, Torgersen S, Neale MC, Reichborn-Kjennerud T (May 2007). "The heritability of cluster A personality disorders assessed by both personal interview and questionnaire". Psychological Medicine. 37 (5): 655–665. doi:10.1017/S0033291706009755 (inactive 1 November 2024). PMID 17224098. S2CID 465473. Archived from the original on June 8, 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - Raine A, Allbutt J (February 1989). "Factors of schizoid personality". The British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 28 (1): 31–40. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8260.1989.tb00809.x. PMID 2924025.

- Collins LM, Blanchard JJ, Biondo KM (October 2005). "Behavioral signs of schizoidia and schizotypy in social anhedonics". Schizophrenia Research. 78 (2–3): 309–322. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2005.04.021. PMID 15950438. S2CID 36987880.

- Charney DS, Nestler EJ (2005-07-21). Neurobiology of Mental Illness. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-19-518980-3.

- ^ Lugnegård T, Hallerbäck MU, Gillberg C (May 2012). "Personality disorders and autism spectrum disorders: what are the connections?". Comprehensive Psychiatry. 53 (4): 333–340. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.05.014. PMID 21821235. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022.

- ^ Cook ML, Zhang Y, Constantino JN (February 2020). "On the Continuity Between Autistic and Schizoid Personality Disorder Trait Burden: A Prospective Study in Adolescence". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 208 (2): 94–100. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000001105. PMC 6982569. PMID 31856140.

- ^ Thylstrup B, Hesse M (2009-04-01). ""I am not complaining"--ambivalence construct in schizoid personality disorder". American Journal of Psychotherapy. 63 (2): 147–167. doi:10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2009.63.2.147. PMID 19711768. Archived from the original on March 14, 2022.

- ^ "Schizoid personality disorder – Diagnosis and treatment – Mayo Clinic". mayoclinic.org. August 17, 2017. Archived from the original on June 7, 2022. Retrieved 2022-09-30.

- "Schizoid Personality Disorder (pp. 652–655)". Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (2013). American Psychiatric Association. 2013. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8 – via Internet Archive.

- Skodol AE, Bender DS, Morey LC, Clark LA, Oldham JM, Alarcon RD, et al. (April 2011). "Personality disorder types proposed for DSM-5". Journal of Personality Disorders. 25 (2): 136–169. doi:10.1521/pedi.2011.25.2.136. PMID 21466247. Archived from the original on August 29, 2021.

- Ullrich S, Farrington DP, Coid JW (December 2007). "Dimensions of DSM-IV personality disorders and life-success". Journal of Personality Disorders. 21 (6): 657–663. doi:10.1521/pedi.2007.21.6.657. PMID 18072866. S2CID 30040457.

- ^ Millon T, Millon CM, Meagher S (2004). Personality Disorders in Modern Life. [electronic resource]. Library Genesis. Hoboken : John Wiley & Sons (published November 8, 2004). ISBN 978-0-471-66850-3.

- ^ Descriptions from DSM-III (1980) and DSM-5 (2013):"Schizoid PD, Associated features (p. 310)" and "Schizoid PD (p. 652–655)".

- ^ Masterson J, Klein R (17 June 2013). Disorders of the Self – The Masterson Approach. New York: Taylor & Francis (published June 17, 2013). pp. 25–27, pp. 54–55, pp. 95–143 (therapy). ISBN 978-0-87630-786-1. LCCN 95020920. OL 788549M. Alt URL

- ^ Levi-Belz Y, Gvion Y, Levi U, Apter A (April 2019). "Beyond the mental pain: A case-control study on the contribution of schizoid personality disorder symptoms to medically serious suicide attempts". Comprehensive Psychiatry. 90: 102–109. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2019.02.005. PMID 30852349.

- Attademo L, Bernardini F, Spatuzzi R (2021). "Suicidality in Individuals with Schizoid Personality Disorder or Traits: A Clinical Mini-Review of a Probably Underestimated Issue" (PDF). Psychiatria Danubina. 33 (3): 261–265. doi:10.24869/psyd.2021.261. PMID 34795159. S2CID 244385145. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 22, 2022.

- ^ Livesley WJ, West M (February 1986). "The DSM-III Distinction between schizoid and avoidant personality disorders". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 31 (1): 59–62. doi:10.1177/070674378603100112. PMID 3948107. S2CID 46283956.

- Both types shared a detachment from the world but Schizoids also showed eccentricity and paradoxicality of emotional life and behavior, emotional coldness and dryness, unpredictability combined with lack of intuition and ambivalence (e.g., simultaneous presence of both stubbornness and submissiveness). Characteristic of Dreamers were tenderness and fragility, receptiveness to beauty, weak-willedness and listlessness, luxuriant imagination, dereism and usually an inflated self-concept. (From: Gannushkin, P.B (1933). Manifestations of psychopathies: statics, dynamics, systematic aspects.)

- ^ Kretschmer E (1931). Physique and Character. London: Routledge (International Library of Psychology, 1999). ISBN 978-0-415-21060-7. OCLC 858861653.

- Eugen Bleuler – Textbook of Psychiatry, New York: Macmillan (1924)

- Fairnbairn R (1992) . Psychoanalytic Studies of Personality. Routledge. pp. 1–20. ISBN 0-415-05174-6.

- Donald Winnicott (1965): The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment: Studies in the Theory of Emotional Development. Karnac Books. ISBN 9780946439843.

- "Schizoid personality". Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (PDF) (1st ed.). Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Association. p. 35. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 14, 2022.

- "Schizoid personality". Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (PDF) (2nd ed.). Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Association. 1968. p. 42. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 25, 2022.

- ^ Fariba KA, Madhanagopal N, Gupta V (2022). "Schizoid Personality Disorder". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32644660. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved 2022-09-24.

- American Psychiatric Association, American Psychiatric Association. Work Group to Revise DSM-III (1987). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-III-R. Internet Archive. Washington, DC : American Psychiatric Association. ISBN 978-0-89042-018-8.

- McGraw JG (2012-01-01). "DSM-IV Personality Disorders". Personality Disorders and States of Aloneness. Value Inquiry Book Series. Vol. 246. Brill. pp. 351–359. doi:10.1163/9789401207706_016. ISBN 978-94-012-0770-6. Archived from the original on June 22, 2022.

- ^ Zimmerman M. "Schizoid Personality Disorder (ScPD) – Psychiatric Disorders". Archived from the original on August 3, 2022. Retrieved 2022-09-24 – via MDS Manual.

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, et al. (July 2004). "Prevalence, correlates, and disability of personality disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 65 (7): 948–958. doi:10.4088/jcp.v65n0711. PMID 15291684.

- ^ Ethesham H (April 9, 2009). A study of Hypnotherapy as a special treatment of dissociative, adjustment problems, Personality and Psychosomatic Disorders (PDF) (Ph.D. thesis). Saurashtra University. pp. 89–90, 133. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 10, 2017.

- Fonseca-Pedrero E, Paino M, Santarén-Rosell M, Lemos-Giráldez S (2013). "Cluster A maladaptive personality patterns in a non-clinical adolescent population". Psicothema. 25 (2): 171–178. doi:10.7334/psicothema2012.74. hdl:10651/18609. PMID 23628530.

- Jane JS, Oltmanns TF, South SC, Turkheimer E (February 2007). "Gender bias in diagnostic criteria for personality disorders: an item response theory analysis". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 116 (1): 166–175. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.166. PMC 4372614. PMID 17324027.

- ^ Coid J, Yang M, Tyrer P, Roberts A, Ullrich S (May 2006). "Prevalence and correlates of personality disorder in Great Britain". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 188 (5): 423–431. doi:10.1192/bjp.188.5.423. PMID 16648528.

- Manfield P (1992). Split self/split object: understanding and treating borderline, narcissistic, and schizoid disorders. Jason Aronson. pp. 204–207. ISBN 978-0-87668-460-3.

- ^ Vaillant GE, Drake RE (June 1985). "Maturity of ego defenses in relation to DSM-III axis II personality disorder". Archives of General Psychiatry. 42 (6): 597–601. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790290079009. PMID 4004502. Archived from the original on December 27, 2020.

- Connolly AJ, Cobb-Richardson P, Ball SA (December 2008). "Personality disorders in homeless drop-in center clients" (PDF). Journal of Personality Disorders. 22 (6): 573–588. doi:10.1521/pedi.2008.22.6.573. PMID 19072678. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-06-17.

- "An Empirical Investigation of Jung's Personality Types and Psychological Disorder Features" (PDF). Journal of Psychological Type/University of Colorado Colorado Springs. 2001. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-01-25. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- Jenkins RL, Glickman S (1946). "Common syndromes in child psychiatry: II. The schizoid child". American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 16 (2): 255–261. doi:10.1111/j.1939-0025.1946.tb05379.x. ISSN 1939-0025. Archived from the original on June 3, 2018.

- Bogaerts S, Vanheule S, Desmet M (April 2006). "Personality disorders and romantic adult attachment: a comparison of secure and insecure attached child molesters". International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 50 (2): 139–147. doi:10.1177/0306624X05278515. PMID 16510885. S2CID 21792134.

- Lenzenweger MF (November 2010). "A source, a cascade, a schizoid: a heuristic proposal from the Longitudinal Study of Personality Disorders". Development and Psychopathology. 22 (4): 867–881. doi:10.1017/S0954579410000519. PMID 20883587. S2CID 1163362.

- Nirestean A, Lukacs E, Cimpan D, Taran L (2012). "Schizoid personality disorder-the peculiarities of their interpersonal relationships and existential roles: Complex case". Personality and Mental Health. 6 (1): 69–74. doi:10.1002/pmh.1182 – via Wiley Online Library.

- Ward S (2018). "The Black Hole: Exploring the Schizoid Personality Disorder, Dysfunction, and Deprivation with their Roots in the Prenatal and Perinatal Period". Journal of Prenatal & Perinatal Psychology & Health. 33 (1). ProQuest 2183511090. Retrieved 2022-09-29 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Nirestean A, Lukacs E, Cimpan D, Taran L (2012). "Schizoid personality disorder-the peculiarities of their interpersonal relationships and existential roles: Complex case". Personality and Mental Health. 6 (1): 69–74. doi:10.1002/pmh.1182. Archived from the original on January 8, 2015.

- Simon AE, Keller P, Cattapan K (March 2021). "Commentary about social avoidance and its significance in adolescents and young adults". Psychiatry Research. 297: 113718. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113718. PMID 33465524. S2CID 231597645.

- ^ Wheeler Z (December 2013). Treatment of schizoid personality: An analytic psychotherapy handbook (PsyD thesis). Pepperdine University. Archived from the original on April 4, 2021.

- Yontef G (December 28, 2017). "Psychotherapy of Schizoid Process". Transactional Analysis Journal. 31 (1): 7–23. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.549.1050. doi:10.1177/036215370103100103. S2CID 15715220. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021 – via CiteSeerX.

- ^ Waska RT (2001-01-01). "Schizoid anxiety: a reappraisal of the manic defense and the depressive position". American Journal of Psychotherapy. 55 (1): 105–121. doi:10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2001.55.1.105. PMID 11291187.

- Bowins B (2010). "Personality disorders: a dimensional defense mechanism approach". American Journal of Psychotherapy. 64 (2): 153–169. doi:10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2010.64.2.153. PMID 20617788.

- Kavaler-Adler S (March 2004). "Anatomy of regret: a developmental view of the depressive position and a critical turn toward love and creativity in the transforming schizoid personality". American Journal of Psychoanalysis. 64 (1): 39–76. doi:10.1023/B:TAJP.0000017991.56175.ea. PMID 14993841. S2CID 41834652.

- Orcutt C (2012-03-31). Trauma in Personality Disorder: A Clinician'S Handbook the Masterson Approach. AuthorHouse. pp. 120–123. ISBN 978-1-4685-5814-2.

- ^ Martens WH (2010). "Schizoid personality disorder linked to unbearable and inescapable loneliness". The European Journal of Psychiatry. 24 (1): 38–45. doi:10.4321/S0213-61632010000100005. ISSN 0213-6163. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016 – via SciElo.

- Morgan PT, Desai RA, Potenza MN (October 2010). "Gender-related influences of parental alcoholism on the prevalence of psychiatric illnesses: analysis of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 34 (10): 1759–1767. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01263.x. PMC 2950877. PMID 20645936.

- Wolff S (1995). Loners: The Life Path of Unusual Children. Psychology Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-415-06665-5.

- Blaney PH, Krueger RF, Millon T (2014-08-22). Oxford Textbook of Psychopathology. Oxford University Press. p. 649. ISBN 978-0-19-981184-7.

- Reichborn-Kjennerud T (2010). "The genetic epidemiology of personality disorders". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 12 (1): 103–114. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2010.12.1/trkjennerud. PMC 3181941. PMID 20373672.

- Chang CJ, Chen WJ, Liu SK, Cheng JJ, Yang WC, Chang HJ, et al. (January 1, 2002). "Morbidity risk of psychiatric disorders among the first degree relatives of schizophrenia patients in Taiwan". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 28 (3): 379–392. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006947. PMID 12645671.

- Racioppi A, Sheinbaum T, Gross GM, Ballespí S, Kwapil TR, Barrantes-Vidal N (2018-11-08). "Prediction of prodromal symptoms and schizophrenia-spectrum personality disorder traits by positive and negative schizotypy: A 3-year prospective study". PLOS ONE. 13 (11): e0207150. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1307150R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0207150. PMC 6224105. PMID 30408119.

- Fogelson DL, Nuechterlein KH, Asarnow RF, Payne DL, Subotnik KL (June 2004). "Validity of the family history method for diagnosing schizophrenia, schizophrenia-related psychoses, and schizophrenia-spectrum personality disorders in first-degree relatives of schizophrenia probands". Schizophrenia Research. 68 (2–3): 309–317. doi:10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00081-1. PMID 15099612. S2CID 22761177.

- Ahmed AO, Green BA, Buckley PF, McFarland ME (March 2012). "Taxometric analyses of paranoid and schizoid personality disorders". Psychiatry Research. 196 (1): 123–132. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2011.10.010. PMID 22377573. S2CID 19969732.

- Kotlicka-Antczak M, Karbownik MS, Pawełczyk A, Żurner N, Pawełczyk T, Strzelecki D, et al. (April 2019). "A developmentally-stable pattern of premorbid schizoid-schizotypal features predicts psychotic transition from the clinical high-risk for psychosis state". Comprehensive Psychiatry. 90: 95–101. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2019.02.003. PMID 30831438. S2CID 73478881.

- Fogelson DL, Nuechterlein KH, Asarnow RA, Payne DL, Subotnik KL, Jacobson KC, et al. (March 2007). "Avoidant personality disorder is a separable schizophrenia-spectrum personality disorder even when controlling for the presence of paranoid and schizotypal personality disorders The UCLA family study". Schizophrenia Research. 91 (1–3): 192–199. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2006.12.023. PMC 1904485. PMID 17306508.

- Ford TC, Crewther DP (2014). "Factor Analysis Demonstrates a Common Schizoidal Phenotype within Autistic and Schizotypal Tendency: Implications for Neuroscientific Studies". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 5: 117. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00117. PMC 4145657. PMID 25221527.

- Via E, Orfila C, Pedreño C, Rovira A, Menchón JM, Cardoner N, et al. (December 2016). "Structural alterations of the pyramidal pathway in schizoid and schizotypal cluster A personality disorders". International Journal of Psychophysiology. 110: 163–170. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2016.08.006. PMID 27535345.

- Herrera Rodríguez A (2013). "Schizophrenia at adolescence: the relationship between schizophrenia self-reported symptoms and substance abuse, schizoid personality disorder symptoms and migration history". Archived from the original on September 25, 2022.

- Díaz-Castro L, Hoffman K, Cabello-Rangel H, Arredondo A, Herrera-Estrella MÁ (2021). "Family History of Psychiatric Disorders and Clinical Factors Associated With a Schizophrenia Diagnosis". Inquiry. 58: 469580211060797. doi:10.1177/00469580211060797. PMC 8673879. PMID 34845937.

- Boldrini T, Tanzilli A, Di Cicilia G, Gualco I, Lingiardi V, Salcuni S, et al. (2020). "Personality Traits and Disorders in Adolescents at Clinical High Risk for Psychosis: Toward a Clinically Meaningful Diagnosis". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 11: 562835. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.562835. PMC 7753018. PMID 33363479.

- Chen CK, Lin SK, Sham PC, Ball D, Loh EW, Hsiao CC, et al. (November 2003). "Pre-morbid characteristics and co-morbidity of methamphetamine users with and without psychosis". Psychological Medicine. 33 (8): 1407–1414. doi:10.1017/S0033291703008353. PMID 14672249. S2CID 44733368. Archived from the original on April 25, 2022.

- Green MF, Horan WP, Lee J, McCleery A, Reddy LF, Wynn JK (February 2018). "Social Disconnection in Schizophrenia and the General Community". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 44 (2): 242–249. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbx082. PMC 5814840. PMID 28637195.

- Bolinskey PK, Smith EA, Schuder KM, Cooper-Bolinskey D, Myers KR, Hudak DV, et al. (June 2017). "Schizophrenia spectrum personality disorders in psychometrically identified schizotypes at two-year follow-up". Psychiatry Research. 252: 289–295. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2017.03.014. PMID 28288440. S2CID 12367565.

- Lumey LH, Stein AD, Susser E (2011). "Prenatal famine and adult health". Annual Review of Public Health. 32: 237–262. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101230. PMC 3857581. PMID 21219171.

- de Rooij SR, Wouters H, Yonker JE, Painter RC, Roseboom TJ (September 2010). "Prenatal undernutrition and cognitive function in late adulthood". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (39): 16881–16886. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10716881D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1009459107. JSTOR 20779880. PMC 2947913. PMID 20837515.

- Abel KM, Wicks S, Susser ES, Dalman C, Pedersen MG, Mortensen PB, et al. (September 2010). "Birth weight, schizophrenia, and adult mental disorder: is risk confined to the smallest babies?". Archives of General Psychiatry. 67 (9): 923–930. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.100. PMID 20819986.

- ^ Li T (24 December 2021). An Overview of Schizoid Personality Disorder. 4th International Conference on Humanities Education and Social Sciences (ICHESS 2021). Atlantis Press. pp. 1657–1663. doi:10.2991/assehr.k.211220.280. ISBN 978-94-6239-495-7. Archived from the original on April 27, 2022.

- Mather AA, Cox BJ, Enns MW, Sareen J (November 2008). "Associations between body weight and personality disorders in a nationally representative sample". Psychosomatic Medicine. 70 (9): 1012–1019. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e318189a930. PMID 18842749. S2CID 26386820.

- Laakso A, Vilkman H, Kajander J, Bergman J, paranta M, Solin O, et al. (February 2000). "Prediction of detached personality in healthy subjects by low dopamine transporter binding". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 157 (2): 290–292. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.290. PMID 10671406.

- ^ Hemmati A, Rezaei F, Rahmani K, Shams-Alizadeh N, Davarinejad O, Shirzadi M, et al. (2022-01-01). "Differential profile of three overlap psychiatric diagnoses using temperament and character model: A systematic review and meta-analysis of avoidant personality disorder, schizoid personality disorder, and social anxiety disorder". Annals of Indian Psychiatry. 6 (1): 15. doi:10.4103/aip.aip_148_21. ISSN 2588-8358. S2CID 248531934. Archived from the original on September 26, 2022.

- Dolan M, Anderson IM, Deakin JF (April 2001). "Relationship between 5-HT function and impulsivity and aggression in male offenders with personality disorders". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 178 (4): 352–359. doi:10.1192/bjp.178.4.352. PMID 11282815.

- Zald DH, Treadway MT (May 2017). "Reward Processing, Neuroeconomics, and Psychopathology". Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 13: 471–495. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-044957. PMC 5958615. PMID 28301764.

- Hadfield J (2014-04-09). "Head injuries can make children loners". News. Retrieved 2022-10-02.

- Blanchard JJ, Aghevli M, Wilson A, Sargeant M (May 2010). "Developmental instability in social anhedonia: an examination of minor physical anomalies and clinical characteristics". Schizophrenia Research. 118 (1–3): 162–167. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2009.10.028. PMC 2856752. PMID 19944570.

- Wolff S (November 1991). "'Schizoid' personality in childhood and adult life. I: The vagaries of diagnostic labelling". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 159 (5): 615–620. doi:10.1192/bjp.159.5.615. PMID 1756336. S2CID 8524074.

- Hayakawa K, Watabe M, Horikawa H, Sato-Kasai M, Shimokawa N, Nakao T, et al. (January 2022). "Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Is a Possible Blood Biomarker of Schizoid Personality Traits among Females". Journal of Personalized Medicine. 12 (2): 131. doi:10.3390/jpm12020131. PMC 8875671. PMID 35207620.

- Pluzhnikov IV, Kaleda VG (2015-06-01). "Neuropsychological findings in personality disorders: A.R. Luria's Approach" (PDF). Psychology in Russia: State of the Art. 8 (2): 113–125. doi:10.11621/pir.2015.0210. ISSN 2074-6857.

- Dobbert DL (2007-01-30). Understanding Personality Disorders: An Introduction: An Introduction. ABC-CLIO. pp. 17–21. ISBN 978-0-313-06804-1.

- Tackett JL, Balsis S, Oltmanns TF, Krueger RF (2009). "A unifying perspective on personality pathology across the life span: developmental considerations for the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders". Development and Psychopathology. 21 (3): 687–713. doi:10.1017/S095457940900039X. PMC 2864523. PMID 19583880.

- Kagan D (2004-05-04). Positive reinforcement as an intervention for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and schizoid personality disorder (MA thesis). Rowan University. Archived from the original on September 25, 2022.

- Weiss EM, Schulter G, Freudenthaler HH, Hofer E, Pichler N, Papousek I (2012-05-31). "Potential markers of aggressive behavior: the fear of other persons' laughter and its overlaps with mental disorders". PLOS ONE. 7 (5): e38088. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...738088W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038088. PMC 3364988. PMID 22675438.

- Ramklint M, von Knorring AL, von Knorring L, Ekselius L (2003-01-01). "Child and adolescent psychiatric disorders predicting adult personality disorder: a follow-up study". Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 57 (1): 23–28. doi:10.1080/psc.57.1.23. PMID 12745785. S2CID 45425586.

- Sevilla-Llewellyn-Jones J, Cano-Domínguez P, de-Luis-Matilla A, Espina-Eizaguirre A, Moreno-Kustner B, Ochoa S (June 2019). "Subjective quality of life in recent onset of psychosis patients and its association with sociodemographic variables, psychotic symptoms and clinical personality traits". Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 13 (3): 525–531. doi:10.1111/eip.12515. PMID 29278295. S2CID 9806674.

- Mulder RT, Joyce PR, Frampton CM, Luty SE, Sullivan PF (January 2006). "Six months of treatment for depression: outcome and predictors of the course of illness". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 163 (1): 95–100. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.95. PMID 16390895.

- Keown P, Holloway F, Kuipers E (May 2002). "The prevalence of personality disorders, psychotic disorders and affective disorders amongst the patients seen by a community mental health team in London". Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 37 (5): 225–229. doi:10.1007/s00127-002-0533-z. PMID 12107714. S2CID 13401664. Archived from the original on March 11, 2022.

- Colli A, Tanzilli A, Dimaggio G, Lingiardi V (January 2014). "Patient personality and therapist response: an empirical investigation". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 171 (1): 102–108. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13020224. PMID 24077643. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022.

- Kelly BD, Casey P, Dunn G, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Dowrick C (April 2007). "The role of personality disorder in 'difficult to reach' patients with depression: findings from the ODIN study". European Psychiatry. 22 (3): 153–159. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2006.07.003. hdl:10197/5863. PMID 17127039. S2CID 7753444. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 14, 2017.

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR (February 2012). "An attachment perspective on psychopathology". World Psychiatry. 11 (1): 11–15. doi:10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.01.003. PMC 3266769. PMID 22294997.

- Westen D, Nakash O, Thomas C, Bradley R (December 2006). "Clinical assessment of attachment patterns and personality disorder in adolescents and adults". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 74 (6): 1065–1085. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1065. PMID 17154736.

- Sperry L (2016-05-12). Handbook of Diagnosis and Treatment of DSM-5 Personality Disorders: Assessment, Case Conceptualization, and Treatment, Third Edition (3rd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-01922-8.

- Căndel OS, Constantin T (June 30, 2017). "Antisocial and Schizoid Personality Disorder Scales: Conceptual bases and preliminary findings" (PDF). Romanian Journal of Applied Psychology. 19 (1). Romania: West University of Timisoara Publishing Hous. doi:10.24913/rjap.19.1.02. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 2, 2017.

- ^ Carvalho LD, Salvador AP, Gonçalves AP (2020). "Development and Preliminary Psychometric Evaluation of the Dimensional Clinical Personality Inventory – Schizoid Personality Disorder Scale". Avaliação Psicológica. 19 (3): 289–297. doi:10.15689/ap.2020.1903.16758.07. ISSN 1677-0471. S2CID 234916163. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 2, 2022.

- Brieger P, Sommer S, Blöink F, Marneros AA (2000-09-01). "The relationship between five-factor personality measurements and ICD-10 personality disorder dimensions: results from a sample of 229 subjects". Journal of Personality Disorders. 14 (3): 282–290. doi:10.1521/pedi.2000.14.3.282. PMID 11019751.

- Hazen EP, Goldstein MA, Goldstein MC (2010-12-22). "Personality Disorders". Mental Health Disorders in Adolescents. Rutgers University Press. pp. 192–202. doi:10.36019/9780813552347. ISBN 978-0-8135-5234-7. S2CID 241632462.

- Kwapil TR (November 1998). "Social anhedonia as a predictor of the development of schizophrenia-spectrum disorders" (PDF). Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 107 (4): 558–565. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.107.4.558. PMID 9830243.

- Ross SR, Lutz CJ, Bailley SE (August 2002). "Positive and negative symptoms of schizotypy and the Five-factor model: a domain and facet level analysis". Journal of Personality Assessment. 79 (1). Psychology Faculty Publications: 53–72. doi:10.1207/S15327752JPA7901_04. PMID 12227668. S2CID 6678948. Archived from the original on September 21, 2017.

- Cicero DC, Krieg A, Becker TM, Kerns JG (October 2016). "Evidence for the Discriminant Validity of the Revised Social Anhedonia Scale From Social Anxiety". Assessment. 23 (5): 544–556. doi:10.1177/1073191115590851. PMID 26092042. S2CID 3813109.

- ^ Materson J, Klein R (June 23, 2015). Disorders of the Self: New Therapeutic Horizons: The Masterson Approach. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-88374-1. Archived from the original on February 27, 2022. Retrieved 2022-09-29.

- Winarick DJ (2020-09-18). "Schizoid Personality Disorder". In Carducci BJ, Nave CS, Mio JS, Riggio RE (eds.). The Wiley Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences (1st ed.). Wiley. pp. 181–185. doi:10.1002/9781119547181.ch294. ISBN 978-1-119-05747-5.

- Carbone JT, Holzer KJ, Vaughn MG, DeLisi M (January 2020). "Homicidal Ideation and Forensic Psychopathology: Evidence From the 2016 Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS)". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 65 (1): 154–159. doi:10.1111/1556-4029.14156. PMID 31404481. S2CID 199550054.

- Manfield P (1992). Split self/split object: understanding and treating borderline, narcissistic, and schizoid disorders. Jason Aronson. pp. 204–207. ISBN 978-0-87668-460-3.

- Guntrip H (September 1952). "A study of Fairbairn's theory of schizoid reactions". The British Journal of Medical Psychology. 25 (2–3): 86–103. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8341.1952.tb00791.x. PMID 12987588.

- Shedler J, Westen D (August 2004). "Refining personality disorder diagnosis: integrating science and practice". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 161 (8): 1350–1365. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1350. PMID 15285958. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021.

- ^ McWilliams N (February 2006). "Some thoughts about schizoid dynamics". Psychoanalytic Review. 93 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1521/prev.2006.93.1.1. PMID 16637769.

- ^ Parpottas P (2012). "A critique on the use of standard psychopathological classifications in understanding human distress: The example of 'schizoid personality disorder'". Counselling Psychology Review. 27 (1). Cyprus: 44–52. doi:10.53841/bpscpr.2011.27.1.44. S2CID 203062083. Archived from the original on August 18, 2019. Retrieved 2022-09-26 – via ResearchGate.

- Akhtar S (1999). "The distinction between needs and wishes: implications for psychoanalytic theory and technique". Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association. 47 (1): 113–151. doi:10.1177/00030651990470010201. PMID 10367274. S2CID 13250602.

- Winnicott D (2006). The Family and Individual Development. Routledge. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-415-40277-4.

- Ernst Kretschmer (March 2013). "Chapter 10. Schizoid temperaments". Body structure and character. Studies on the constitution and theory of temperaments (in Russian). Ripol Classic. ISBN 978-5-458-35839-2.

- Rouff L (April 2000). "Schizoid Personality Traits Among the Homeless Mentally Ill: A uantitative and Qualitative Report". Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless. 9 (2): 127–141. doi:10.1023/A:1009470318513. hdl:2027.42/43983. ISSN 1573-658X. S2CID 39349719 – via SpringerLink.

- Fitzgerald CJ, Colarelli SM (2009-04-01). "Altruism and Reproductive Limitations". Evolutionary Psychology. 7 (2): 147470490900700. doi:10.1177/147470490900700207. ISSN 1474-7049. S2CID 146798018.

- Koch J, Berner W, Hill A, Briken P (November 2011). "Sociodemographic and diagnostic characteristics of homicidal and nonhomicidal sexual offenders". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 56 (6): 1626–1631. doi:10.1111/j.1556-4029.2011.01933.x. PMID 21981447. S2CID 26470567.

- Holtzman NS, Strube MJ (2013-12-01). "Above and beyond Short-Term Mating, Long-Term Mating is Uniquely Tied to Human Personality". Evolutionary Psychology. 11 (5): 1101–1129. doi:10.1177/147470491301100514. ISSN 1474-7049. PMC 10430001. PMID 24342881.

- ^ Nannarello JJ (September 1953). "Schizoid". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 118 (3): 237–249. doi:10.1097/00005053-195309000-00004. PMID 13118367.

- Hutsebaut J, Feenstra DJ, Kamphuis JH (April 2016). "Development and Preliminary Psychometric Evaluation of a Brief Self-Report Questionnaire for the Assessment of the DSM-5 level of Personality Functioning Scale: The LPFS Brief Form (LPFS-BF)". Personality Disorders. 7 (2): 192–197. doi:10.1037/per0000159. hdl:11245.1/3fc1adda-98da-455b-bebe-a8efc5c09f9f. PMID 26595344. Archived from the original on September 26, 2022.