Medical intervention

| Acupuncture | |

|---|---|

| |

| ICD-10-PCS | 8E0H30Z |

| ICD-9 | 99.91-99.92 |

| MeSH | D015670 |

| OPS-301 code | 8-975.2 |

| [edit on Wikidata] | |

| Acupuncture | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 針灸 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 针灸 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "needling moxibustion" | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Acupuncture is a form of alternative medicine and a component of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in which thin needles are inserted into the body. Acupuncture is a pseudoscience; the theories and practices of TCM are not based on scientific knowledge, and it has been characterized as quackery.

There is a range of acupuncture technological variants that originated in different philosophies, and techniques vary depending on the country in which it is performed. However, it can be divided into two main foundational philosophical applications and approaches; the first being the modern standardized form called eight principles TCM and the second being an older system that is based on the ancient Daoist wuxing, better known as the five elements or phases in the West. Acupuncture is most often used to attempt pain relief, though acupuncturists say that it can also be used for a wide range of other conditions. Acupuncture is typically used in combination with other forms of treatment.

The global acupuncture market was worth US$24.55 billion in 2017. The market was led by Europe with a 32.7% share, followed by Asia-Pacific with a 29.4% share and the Americas with a 25.3% share. It was estimated in 2021 that the industry would reach a market size of US$55 billion by 2023.

The conclusions of trials and systematic reviews of acupuncture generally provide no good evidence of benefit, which suggests that it is not an effective method of healthcare. Acupuncture is generally safe when done by appropriately trained practitioners using clean needle techniques and single-use needles. When properly delivered, it has a low rate of mostly minor adverse effects. When accidents and infections do occur, they are associated with neglect on the part of the practitioner, particularly in the application of sterile techniques. A review conducted in 2013 stated that reports of infection transmission increased significantly in the preceding decade. The most frequently reported adverse events were pneumothorax and infections. Since serious adverse events continue to be reported, it is recommended that acupuncturists be trained sufficiently to reduce the risk.

Scientific investigation has not found any histological or physiological evidence for traditional Chinese concepts such as qi, meridians, and acupuncture points, and many modern practitioners no longer support the existence of qi or meridians, which was a major part of early belief systems. Acupuncture is believed to have originated around 100 BC in China, around the time The Inner Classic of Huang Di (Huangdi Neijing) was published, though some experts suggest it could have been practiced earlier. Over time, conflicting claims and belief systems emerged about the effect of lunar, celestial and earthly cycles, yin and yang energies, and a body's "rhythm" on the effectiveness of treatment. Acupuncture fluctuated in popularity in China due to changes in the country's political leadership and the preferential use of rationalism or scientific medicine. Acupuncture spread first to Korea in the 6th century AD, then to Japan through medical missionaries, and then to Europe, beginning with France. In the 20th century, as it spread to the United States and Western countries, spiritual elements of acupuncture that conflicted with scientific knowledge were sometimes abandoned in favor of simply tapping needles into acupuncture points.

Clinical practice

Acupuncture is a form of alternative medicine. It is used most commonly for pain relief, though it is also used to treat a wide range of conditions. Acupuncture is generally only used in combination with other forms of treatment. For example, the American Society of Anesthesiologists states it may be considered in the treatment of nonspecific, noninflammatory low back pain only in conjunction with conventional therapy.

Acupuncture is the insertion of thin needles into the skin. According to the Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (Mayo Clinic), a typical session entails lying still while approximately five to twenty needles are inserted; for the majority of cases, the needles will be left in place for ten to twenty minutes. It can be associated with the application of heat, pressure, or laser light. Classically, acupuncture is individualized and based on philosophy and intuition, and not on scientific research. There is also a non-invasive therapy developed in early 20th-century Japan using an elaborate set of instruments other than needles for the treatment of children (shōnishin or shōnihari).

Clinical practice varies depending on the country. A comparison of the average number of patients treated per hour found significant differences between China (10) and the United States (1.2). Chinese herbs are often used. There is a diverse range of acupuncture approaches, involving different philosophies. Although various different techniques of acupuncture practice have emerged, the method used in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) seems to be the most widely adopted in the US. Traditional acupuncture involves needle insertion, moxibustion, and cupping therapy, and may be accompanied by other procedures such as feeling the pulse and other parts of the body and examining the tongue. Traditional acupuncture involves the belief that a "life force" (qi) circulates within the body in lines called meridians. The main methods practiced in the UK are TCM and Western medical acupuncture. The term Western medical acupuncture is used to indicate an adaptation of TCM-based acupuncture which focuses less on TCM. The Western medical acupuncture approach involves using acupuncture after a medical diagnosis. Limited research has compared the contrasting acupuncture systems used in various countries for determining different acupuncture points, and thus there is no defined standard for acupuncture points.

In traditional acupuncture, the acupuncturist decides which points to treat by observing and questioning the patient to make a diagnosis according to the tradition used. In TCM, the four diagnostic methods are: inspection, auscultation and olfaction, inquiring, and palpation. Inspection focuses on the face and particularly on the tongue, including analysis of the tongue size, shape, tension, color and coating, and the absence or presence of teeth marks around the edge. Auscultation and olfaction involve listening for particular sounds, such as wheezing, and observing body odor. Inquiring involves focusing on the "seven inquiries": chills and fever; perspiration; appetite, thirst and taste; defecation and urination; pain; sleep; and menses and leukorrhea. Palpation is focusing on feeling the body for tender A-shi points and feeling the pulse.

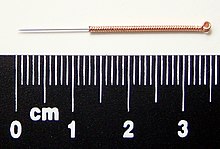

Needles

The most common mechanism of stimulation of acupuncture points employs penetration of the skin by thin metal needles, which are manipulated manually or the needle may be further stimulated by electrical stimulation (electroacupuncture). Acupuncture needles are typically made of stainless steel, making them flexible and preventing them from rusting or breaking. Needles are usually disposed of after each use to prevent contamination. Reusable needles when used should be sterilized between applications. In many areas, only sterile, single-use acupuncture needles are allowed, including the State of California, USA. Needles vary in length between 13 and 130 millimetres (0.51 and 5.12 in), with shorter needles used near the face and eyes, and longer needles in areas with thicker tissues; needle diameters vary from 0.16 mm (0.006 in) to 0.46 mm (0.018 in), with thicker needles used on more robust patients. Thinner needles may be flexible and require tubes for insertion. The tip of the needle should not be made too sharp to prevent breakage, although blunt needles cause more pain.

Apart from the usual filiform needle, other needle types include three-edged needles and the Nine Ancient Needles. Japanese acupuncturists use extremely thin needles that are used superficially, sometimes without penetrating the skin, and surrounded by a guide tube (a 17th-century invention adopted in China and the West). Korean acupuncture uses copper needles and has a greater focus on the hand.

Needling technique

Insertion

The skin is sterilized and needles are inserted, frequently with a plastic guide tube. Needles may be manipulated in various ways, including spinning, flicking, or moving up and down relative to the skin. Since most pain is felt in the superficial layers of the skin, a quick insertion of the needle is recommended. Often the needles are stimulated by hand in order to cause a dull, localized, aching sensation that is called de qi, as well as "needle grasp," a tugging feeling felt by the acupuncturist and generated by a mechanical interaction between the needle and skin. Acupuncture can be painful. The acupuncturist's skill level may influence the painfulness of the needle insertion; a sufficiently skilled practitioner may be able to insert the needles without causing any pain.

De-qi sensation

De-qi (Chinese: 得气; pinyin: dé qì; "arrival of qi") refers to a claimed sensation of numbness, distension, or electrical tingling at the needling site. If these sensations are not observed then inaccurate location of the acupoint, improper depth of needle insertion, inadequate manual manipulation, are blamed. If de-qi is not immediately observed upon needle insertion, various manual manipulation techniques are often applied to promote it (such as "plucking", "shaking" or "trembling").

Once de-qi is observed, techniques might be used which attempt to "influence" the de-qi; for example, by certain manipulation the de-qi can allegedly be conducted from the needling site towards more distant sites of the body. Other techniques aim at "tonifying" (Chinese: 补; pinyin: bǔ) or "sedating" (Chinese: 泄; pinyin: xiè) qi. The former techniques are used in deficiency patterns, the latter in excess patterns. De qi is more important in Chinese acupuncture, while Western and Japanese patients may not consider it a necessary part of the treatment.

Related practices

- Acupressure, a non-invasive form of bodywork, uses physical pressure applied to acupressure points by the hand or elbow, or with various devices.

- Acupuncture is often accompanied by moxibustion, the burning of cone-shaped preparations of moxa (made from dried mugwort) on or near the skin, often but not always near or on an acupuncture point. Traditionally, acupuncture was used to treat acute conditions while moxibustion was used for chronic diseases. Moxibustion could be direct (the cone was placed directly on the skin and allowed to burn the skin, producing a blister and eventually a scar), or indirect (either a cone of moxa was placed on a slice of garlic, ginger or other vegetable, or a cylinder of moxa was held above the skin, close enough to either warm or burn it).

- Cupping therapy is an ancient Chinese form of alternative medicine in which a local suction is created on the skin; practitioners believe this mobilizes blood flow in order to promote healing.

- Tui na is a TCM method of attempting to stimulate the flow of qi by various bare-handed techniques that do not involve needles.

- Electroacupuncture is a form of acupuncture in which acupuncture needles are attached to a device that generates continuous electric pulses (this has been described as "essentially transdermal electrical nerve stimulation masquerading as acupuncture").

- Fire needle acupuncture also known as fire needling is a technique which involves quickly inserting a flame-heated needle into areas on the body.

- Sonopuncture is a stimulation of the body similar to acupuncture using sound instead of needles. This may be done using purpose-built transducers to direct a narrow ultrasound beam to a depth of 6–8 centimetres at acupuncture meridian points on the body. Alternatively, tuning forks or other sound emitting devices are used.

- Acupuncture point injection is the injection of various substances (such as drugs, vitamins or herbal extracts) into acupoints. This technique combines traditional acupuncture with injection of what is often an effective dose of an approved pharmaceutical drug, and proponents claim that it may be more effective than either treatment alone, especially for the treatment of some kinds of chronic pain. However, a 2016 review found that most published trials of the technique were of poor value due to methodology issues and larger trials would be needed to draw useful conclusions.

- Auriculotherapy, commonly known as ear acupuncture, auricular acupuncture, or auriculoacupuncture, is considered to date back to ancient China. It involves inserting needles to stimulate points on the outer ear. The modern approach was developed in France during the early 1950s. There is no scientific evidence that it can cure disease; the evidence of effectiveness is negligible.

- Scalp acupuncture, developed in Japan, is based on reflexological considerations regarding the scalp.

- Koryo hand acupuncture, developed in Korea, centers around assumed reflex zones of the hand. Medical acupuncture attempts to integrate reflexological concepts, the trigger point model, and anatomical insights (such as dermatome distribution) into acupuncture practice, and emphasizes a more formulaic approach to acupuncture point location.

- Cosmetic acupuncture is the use of acupuncture in an attempt to reduce wrinkles on the face.

- Bee venom acupuncture is a treatment approach of injecting purified, diluted bee venom into acupoints.

- Veterinary acupuncture is the use of acupuncture on domesticated animals.

-

Acupressure being applied to a hand

Acupressure being applied to a hand

-

Sujichim, hand acupuncture

Sujichim, hand acupuncture

-

Japanese moxibustion

Japanese moxibustion

-

A woman receiving fire cupping in China

Efficacy

As of 2021, many thousands of papers had been published on the efficacy of acupuncture for the treatment of various adult health conditions, but there was no robust evidence it was beneficial for anything, except shoulder pain and fibromyalgia. For Science-Based Medicine, Steven Novella wrote that the overall pattern of evidence was reminiscent of that for homeopathy, compatible with the hypothesis that most, if not all, benefits were due to the placebo effect, and strongly suggestive that acupuncture had no beneficial therapeutic effects at all.

Research methodology and challenges

Sham acupuncture and research

It is difficult but not impossible to design rigorous research trials for acupuncture. Due to acupuncture's invasive nature, one of the major challenges in efficacy research is in the design of an appropriate placebo control group. For efficacy studies to determine whether acupuncture has specific effects, "sham" forms of acupuncture where the patient, practitioner, and analyst are blinded seem the most acceptable approach. Sham acupuncture uses non-penetrating needles or needling at non-acupuncture points, e.g. inserting needles on meridians not related to the specific condition being studied, or in places not associated with meridians. The under-performance of acupuncture in such trials may indicate that therapeutic effects are due entirely to non-specific effects, or that the sham treatments are not inert, or that systematic protocols yield less than optimal treatment.

A 2014 review in Nature Reviews Cancer found that "contrary to the claimed mechanism of redirecting the flow of qi through meridians, researchers usually find that it generally does not matter where the needles are inserted, how often (that is, no dose-response effect is observed), or even if needles are actually inserted. In other words, "sham" or "placebo" acupuncture generally produces the same effects as "real" acupuncture and, in some cases, does better." A 2013 meta-analysis found little evidence that the effectiveness of acupuncture on pain (compared to sham) was modified by the location of the needles, the number of needles used, the experience or technique of the practitioner, or by the circumstances of the sessions. The same analysis also suggested that the number of needles and sessions is important, as greater numbers improved the outcomes of acupuncture compared to non-acupuncture controls. There has been little systematic investigation of which components of an acupuncture session may be important for any therapeutic effect, including needle placement and depth, type and intensity of stimulation, and number of needles used. The research seems to suggest that needles do not need to stimulate the traditionally specified acupuncture points or penetrate the skin to attain an anticipated effect (e.g. psychosocial factors).

A response to "sham" acupuncture in osteoarthritis may be used in the elderly, but placebos have usually been regarded as deception and thus unethical. However, some physicians and ethicists have suggested circumstances for applicable uses for placebos such as it might present a theoretical advantage of an inexpensive treatment without adverse reactions or interactions with drugs or other medications. As the evidence for most types of alternative medicine such as acupuncture is far from strong, the use of alternative medicine in regular healthcare can present an ethical question.

Using the principles of evidence-based medicine to research acupuncture is controversial, and has produced different results. Some research suggests acupuncture can alleviate pain but the majority of research suggests that acupuncture's effects are mainly due to placebo. Evidence suggests that any benefits of acupuncture are short-lasting. There is insufficient evidence to support use of acupuncture compared to mainstream medical treatments. Acupuncture is not better than mainstream treatment in the long term.

The use of acupuncture has been criticized owing to there being little scientific evidence for explicit effects, or the mechanisms for its supposed effectiveness, for any condition that is discernible from placebo. Acupuncture has been called "theatrical placebo", and David Gorski argues that when acupuncture proponents advocate "harnessing of placebo effects" or work on developing "meaningful placebos", they essentially concede it is little more than that.

Publication bias

Publication bias is cited as a concern in the reviews of randomized controlled trials of acupuncture. A 1998 review of studies on acupuncture found that trials originating in China, Japan, Hong Kong, and Taiwan were uniformly favourable to acupuncture, as were ten out of eleven studies conducted in Russia. A 2011 assessment of the quality of randomized controlled trials on traditional Chinese medicine, including acupuncture, concluded that the methodological quality of most such trials (including randomization, experimental control, and blinding) was generally poor, particularly for trials published in Chinese journals (though the quality of acupuncture trials was better than the trials testing traditional Chinese medicine remedies). The study also found that trials published in non-Chinese journals tended to be of higher quality. Chinese authors use more Chinese studies, which have been demonstrated to be uniformly positive. A 2012 review of 88 systematic reviews of acupuncture published in Chinese journals found that less than half of these reviews reported testing for publication bias, and that the majority of these reviews were published in journals with impact factors of zero. A 2015 study comparing pre-registered records of acupuncture trials with their published results found that it was uncommon for such trials to be registered before the trial began. This study also found that selective reporting of results and changing outcome measures to obtain statistically significant results was common in this literature.

Scientist Steven Salzberg identifies acupuncture and Chinese medicine generally as a focus for "fake medical journals" such as the Journal of Acupuncture and Meridian Studies and Acupuncture in Medicine.

Safety

Adverse events

Acupuncture is generally safe when administered by an experienced, appropriately trained practitioner using clean-needle technique and sterile single-use needles. When improperly delivered it can cause adverse effects. Accidents and infections are associated with infractions of sterile technique or neglect on the part of the practitioner. To reduce the risk of serious adverse events after acupuncture, acupuncturists should be trained sufficiently. A 2009 overview of Cochrane reviews found acupuncture is not effective for a wide range of conditions. People with serious spinal disease, such as cancer or infection, are not good candidates for acupuncture. Contraindications to acupuncture (conditions that should not be treated with acupuncture) include coagulopathy disorders (e.g. hemophilia and advanced liver disease), warfarin use, severe psychiatric disorders (e.g. psychosis), and skin infections or skin trauma (e.g. burns). Further, electroacupuncture should be avoided at the spot of implanted electrical devices (such as pacemakers).

A 2011 systematic review of systematic reviews (internationally and without language restrictions) found that serious complications following acupuncture continue to be reported. Between 2000 and 2009, ninety-five cases of serious adverse events, including five deaths, were reported. Many such events are not inherent to acupuncture but are due to malpractice of acupuncturists. This might be why such complications have not been reported in surveys of adequately trained acupuncturists. Most such reports originate from Asia, which may reflect the large number of treatments performed there or a relatively higher number of poorly trained Asian acupuncturists. Many serious adverse events were reported from developed countries. These included Australia, Austria, Canada, Croatia, France, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK, and the US. The number of adverse effects reported from the UK appears particularly unusual, which may indicate less under-reporting in the UK than other countries. Reports included 38 cases of infections and 42 cases of organ trauma. The most frequent adverse events included pneumothorax, and bacterial and viral infections.

A 2013 review found (without restrictions regarding publication date, study type or language) 295 cases of infections; mycobacterium was the pathogen in at least 96%. Likely sources of infection include towels, hot packs or boiling tank water, and reusing reprocessed needles. Possible sources of infection include contaminated needles, reusing personal needles, a person's skin containing mycobacterium, and reusing needles at various sites in the same person. Although acupuncture is generally considered a safe procedure, a 2013 review stated that the reports of infection transmission increased significantly in the prior decade, including those of mycobacterium. Although it is recommended that practitioners of acupuncture use disposable needles, the reuse of sterilized needles is still permitted. It is also recommended that thorough control practices for preventing infection be implemented and adapted.

English-language

A 2013 systematic review of the English-language case reports found that serious adverse events associated with acupuncture are rare, but that acupuncture is not without risk. Between 2000 and 2011 the English-language literature from 25 countries and regions reported 294 adverse events. The majority of the reported adverse events were relatively minor, and the incidences were low. For example, a prospective survey of 34,000 acupuncture treatments found no serious adverse events and 43 minor ones, a rate of 1.3 per 1000 interventions. Another survey found there were 7.1% minor adverse events, of which 5 were serious, amid 97,733 acupuncture patients. The most common adverse effect observed was infection (e.g. mycobacterium), and the majority of infections were bacterial in nature, caused by skin contact at the needling site. Infection has also resulted from skin contact with unsterilized equipment or with dirty towels in an unhygienic clinical setting. Other adverse complications included five reported cases of spinal cord injuries (e.g. migrating broken needles or needling too deeply), four brain injuries, four peripheral nerve injuries, five heart injuries, seven other organ and tissue injuries, bilateral hand edema, epithelioid granuloma, pseudolymphoma, argyria, pustules, pancytopenia, and scarring due to hot-needle technique. Adverse reactions from acupuncture, which are unusual and uncommon in typical acupuncture practice, included syncope, galactorrhoea, bilateral nystagmus, pyoderma gangrenosum, hepatotoxicity, eruptive lichen planus, and spontaneous needle migration.

A 2013 systematic review found 31 cases of vascular injuries caused by acupuncture, three causing death. Two died from pericardial tamponade and one was from an aortoduodenal fistula. The same review found vascular injuries were rare, bleeding and pseudoaneurysm were most prevalent. A 2011 systematic review (without restriction in time or language), aiming to summarize all reported case of cardiac tamponade after acupuncture, found 26 cases resulting in 14 deaths, with little doubt about cause in most fatal instances. The same review concluded that cardiac tamponade was a serious, usually fatal, though theoretically avoidable complication following acupuncture, and urged training to minimize risk.

A 2012 review found that a number of adverse events were reported after acupuncture in the UK's National Health Service (NHS), 95% of which were not severe, though miscategorization and under-reporting may alter the total figures. From January 2009 to December 2011, 468 safety incidents were recognized within the NHS organizations. The adverse events recorded included retained needles (31%), dizziness (30%), loss of consciousness/unresponsive (19%), falls (4%), bruising or soreness at needle site (2%), pneumothorax (1%) and other adverse side effects (12%). Acupuncture practitioners should know, and be prepared to be responsible for, any substantial harm from treatments. Some acupuncture proponents argue that the long history of acupuncture suggests it is safe. However, there is an increasing literature on adverse events (e.g. spinal-cord injury).

Acupuncture seems to be safe in people getting anticoagulants, assuming needles are used at the correct location and depth, but studies are required to verify these findings.

Chinese, Korean, and Japanese-language

A 2010 systematic review of the Chinese-language literature found numerous acupuncture-related adverse events, including pneumothorax, fainting, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and infection as the most frequent, and cardiovascular injuries, subarachnoid hemorrhage, pneumothorax, and recurrent cerebral hemorrhage as the most serious, most of which were due to improper technique. Between 1980 and 2009, the Chinese-language literature reported 479 adverse events. Prospective surveys show that mild, transient acupuncture-associated adverse events ranged from 6.71% to 15%. In a study with 190,924 patients, the prevalence of serious adverse events was roughly 0.024%. Another study showed a rate of adverse events requiring specific treatment of 2.2%, 4,963 incidences among 229,230 patients. Infections, mainly hepatitis, after acupuncture are reported often in English-language research, though are rarely reported in Chinese-language research, making it plausible that acupuncture-associated infections have been underreported in China. Infections were mostly caused by poor sterilization of acupuncture needles. Other adverse events included spinal epidural hematoma (in the cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine), chylothorax, injuries of abdominal organs and tissues, injuries in the neck region, injuries to the eyes, including orbital hemorrhage, traumatic cataract, injury of the oculomotor nerve and retinal puncture, hemorrhage to the cheeks and the hypoglottis, peripheral motor-nerve injuries and subsequent motor dysfunction, local allergic reactions to metal needles, stroke, and cerebral hemorrhage after acupuncture.

A causal link between acupuncture and the adverse events cardiac arrest, pyknolepsy, shock, fever, cough, thirst, aphonia, leg numbness, and sexual dysfunction remains uncertain. The same review concluded that acupuncture can be considered inherently safe when practiced by properly trained practitioners, but the review also stated there is a need to find effective strategies to minimize the health risks. Between 1999 and 2010, the Korean-language literature contained reports of 1104 adverse events. Between the 1980s and 2002, the Japanese-language literature contained reports of 150 adverse events.

Children and pregnancy

Although acupuncture has been practiced for thousands of years in China, its use in pediatrics in the United States did not become common until the early 2000s. In 2007, the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) conducted by the National Center For Health Statistics (NCHS) estimated that approximately 150,000 children had received acupuncture treatment for a variety of conditions.

In 2008, a study determined that the use of acupuncture-needle treatment on children was "questionable" due to the possibility of adverse side-effects and the pain manifestation differences in children versus adults. The study also includes warnings against practicing acupuncture on infants, as well as on children who are over-fatigued, very weak, or have over-eaten.

When used on children, acupuncture is considered safe when administered by well-trained, licensed practitioners using sterile needles; however, a 2011 review found there was limited research to draw definite conclusions about the overall safety of pediatric acupuncture. The same review found 279 adverse events, 25 of them serious. The adverse events were mostly mild in nature (e.g., bruising or bleeding). The prevalence of mild adverse events ranged from 10.1% to 13.5%, an estimated 168 incidences among 1,422 patients. On rare occasions adverse events were serious (e.g. cardiac rupture or hemoptysis); many might have been a result of substandard practice. The incidence of serious adverse events was 5 per one million, which included children and adults.

When used during pregnancy, the majority of adverse events caused by acupuncture were mild and transient, with few serious adverse events. The most frequent mild adverse event was needling or unspecified pain, followed by bleeding. Although two deaths (one stillbirth and one neonatal death) were reported, there was a lack of acupuncture-associated maternal mortality. Limiting the evidence as certain, probable or possible in the causality evaluation, the estimated incidence of adverse events following acupuncture in pregnant women was 131 per 10,000.

Although acupuncture is not contraindicated in pregnant women, some specific acupuncture points are particularly sensitive to needle insertion; these spots, as well as the abdominal region, should be avoided during pregnancy.

Moxibustion and cupping

Four adverse events associated with moxibustion were bruising, burns and cellulitis, spinal epidural abscess, and large superficial basal cell carcinoma. Ten adverse events were associated with cupping. The minor ones were keloid scarring, burns, and bullae; the serious ones were acquired hemophilia A, stroke following cupping on the back and neck, factitious panniculitis, reversible cardiac hypertrophy, and iron deficiency anemia.

Risk of forgoing conventional medical care

As with other alternative medicines, unethical or naïve practitioners may induce patients to exhaust financial resources by pursuing ineffective treatment. Professional ethics codes set by accrediting organizations such as the National Certification Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine require practitioners to make "timely referrals to other health care professionals as may be appropriate." Stephen Barrett states that there is a "risk that an acupuncturist whose approach to diagnosis is not based on scientific concepts will fail to diagnose a dangerous condition".

Conceptual basis

| Acupuncture | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 针刺 | ||||||

| |||||||

Traditional

Main articles: Qi, Traditional Chinese medicine, Meridian (Chinese medicine), and List of acupuncture points

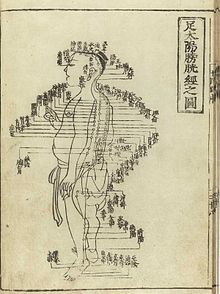

Acupuncture is a substantial part of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). Early acupuncture beliefs relied on concepts that are common in TCM, such as a life force energy called qi. Qi was believed to flow from the body's primary organs (zang-fu organs) to the "superficial" body tissues of the skin, muscles, tendons, bones, and joints, through channels called meridians. Acupuncture points where needles are inserted are mainly (but not always) found at locations along the meridians. Acupuncture points not found along a meridian are called extraordinary points and those with no designated site are called A-shi points.

In TCM, disease is generally perceived as a disharmony or imbalance in energies such as yin, yang, qi, xuĕ, zàng-fǔ, meridians, and of the interaction between the body and the environment. Therapy is based on which "pattern of disharmony" can be identified. For example, some diseases are believed to be caused by meridians being invaded with an excess of wind, cold, and damp. In order to determine which pattern is at hand, practitioners examine things like the color and shape of the tongue, the relative strength of pulse-points, the smell of the breath, the quality of breathing, or the sound of the voice. TCM and its concept of disease does not strongly differentiate between the cause and effect of symptoms.

Purported scientific basis

Many within the scientific community consider acupuncture to be quackery and pseudoscience, having no effect other than as "theatrical placebo". David Gorski has argued that of all forms of quackery, acupuncture has perhaps gained most acceptance among physicians and institutions. Academics Massimo Pigliucci and Maarten Boudry describe acupuncture as a "borderlands science" lying between science and pseudoscience.

Rationalizations of traditional medicine

It is a generally held belief within the acupuncture community that acupuncture points and meridians structures are special conduits for electrical signals, but no research has established any consistent anatomical structure or function for either acupuncture points or meridians. Human tests to determine whether electrical continuity was significantly different near meridians than other places in the body have been inconclusive. Scientific research has not supported the existence of qi, meridians, or yin and yang. A Nature editorial described TCM as "fraught with pseudoscience", with the majority of its treatments having no logical mechanism of action. Quackwatch states that "TCM theory and practice are not based upon the body of knowledge related to health, disease, and health care that has been widely accepted by the scientific community. TCM practitioners disagree among themselves about how to diagnose patients and which treatments should go with which diagnoses. Even if they could agree, the TCM theories are so nebulous that no amount of scientific study will enable TCM to offer rational care." Academic discussions of acupuncture still make reference to pseudoscientific concepts such as qi and meridians despite the lack of scientific evidence.

Release of endorphins or adenosine

Some modern practitioners support the use of acupuncture to treat pain, but have abandoned the use of qi, meridians, yin, yang and other mystical energies as an explanatory frameworks. The use of qi as an explanatory framework has been decreasing in China, even as it becomes more prominent during discussions of acupuncture in the US.

Many acupuncturists attribute pain relief to the release of endorphins when needles penetrate, but no longer support the idea that acupuncture can affect a disease. Some studies suggest acupuncture causes a series of events within the central nervous system, and that it is possible to inhibit acupuncture's analgesic effects with the opioid antagonist naloxone. Mechanical deformation of the skin by acupuncture needles appears to result in the release of adenosine. The anti-nociceptive effect of acupuncture may be mediated by the adenosine A1 receptor. A 2014 review in Nature Reviews Cancer analyzed mouse studies that suggested acupuncture relieves pain via the local release of adenosine, which then triggered nearby A1 receptors. The review found that in those studies, because acupuncture "caused more tissue damage and inflammation relative to the size of the animal in mice than in humans, such studies unnecessarily muddled a finding that local inflammation can result in the local release of adenosine with analgesic effect."

History

Origins

Acupuncture, along with moxibustion, is one of the oldest practices of traditional Chinese medicine. Most historians believe the practice began in China, though there are some conflicting narratives on when it originated. Academics David Ramey and Paul Buell said the exact date acupuncture was founded depends on the extent to which dating of ancient texts can be trusted and the interpretation of what constitutes acupuncture.

Acupressure therapy was prevalent in India. Once Buddhism spread to China, the acupressure therapy was also integrated into common medical practice in China and it came to be known as acupuncture. The major points of Indian acupressure and Chinese acupuncture are similar to each other.

According to an article in Rheumatology, the first documentation of an "organized system of diagnosis and treatment" for acupuncture was in Inner Classic of Huang Di (Huangdi Neijing) from about 100 BC. Gold and silver needles found in the tomb of Liu Sheng from around 100 BC are believed to be the earliest archaeological evidence of acupuncture, though it is unclear if that was their purpose. According to Plinio Prioreschi, the earliest known historical record of acupuncture is the Shiji ("Records of the Grand Historian"), written by a historian around 100 BC. It is believed that this text was documenting what was established practice at that time.

Alternative theories

The 5,000-year-old mummified body of Ötzi the Iceman was found with 15 groups of tattoos, many of which were located at points on the body where acupuncture needles are used for abdominal or lower back problems. Evidence from the body suggests Ötzi had these conditions. This has been cited as evidence that practices similar to acupuncture may have been practised elsewhere in Eurasia during the early Bronze Age; however, The Oxford Handbook of the History of Medicine calls this theory "speculative". It is considered unlikely that acupuncture was practised before 2000 BC.

Acupuncture may have been practised during the Neolithic era, near the end of the Stone Age, using sharpened stones called Bian shi. Many Chinese texts from later eras refer to sharp stones called "plen", which means "stone probe", that may have been used for acupuncture purposes. The ancient Chinese medical text, Huangdi Neijing, indicates that sharp stones were believed at-the-time to cure illnesses at or near the body's surface, perhaps because of the short depth a stone could penetrate. However, it is more likely that stones were used for other medical purposes, such as puncturing a growth to drain its pus. The Mawangdui texts, which are believed to be from the 2nd century BC, mention the use of pointed stones to open abscesses, and moxibustion, but not for acupuncture. It is also speculated that these stones may have been used for bloodletting, due to the ancient Chinese belief that illnesses were caused by demons within the body that could be killed or released. It is likely bloodletting was an antecedent to acupuncture.

According to historians Lu Gwei-djen and Joseph Needham, there is substantial evidence that acupuncture may have begun around 600 BC. Some hieroglyphs and pictographs from that era suggests acupuncture and moxibustion were practised. However, historians Lu and Needham said it was unlikely a needle could be made out of the materials available in China during this time period. It is possible that bronze was used for early acupuncture needles. Tin, copper, gold and silver are also possibilities, though they are considered less likely, or to have been used in fewer cases. If acupuncture was practised during the Shang dynasty (1766 to 1122 BC), organic materials like thorns, sharpened bones, or bamboo may have been used. Once methods for producing steel were discovered, it would replace all other materials, since it could be used to create a very fine, but sturdy needle. Lu and Needham noted that all the ancient materials that could have been used for acupuncture and which often produce archaeological evidence, such as sharpened bones, bamboo or stones, were also used for other purposes. An article in Rheumatology said that the absence of any mention of acupuncture in documents found in the tomb of Mawangdui from 198 BC suggest that acupuncture was not practised by that time.

Belief systems

Several different and sometimes conflicting belief systems emerged regarding acupuncture. This may have been the result of competing schools of thought. Some ancient texts referred to using acupuncture to cause bleeding, while others mixed the ideas of blood-letting and spiritual ch'i energy. Over time, the focus shifted from blood to the concept of puncturing specific points on the body, and eventually to balancing Yin and Yang energies as well. According to David Ramey, no single "method or theory" was ever predominantly adopted as the standard. At the time, scientific knowledge of medicine was not yet developed, especially because in China dissection of the deceased was forbidden, preventing the development of basic anatomical knowledge.

It is not certain when specific acupuncture points were introduced, but the autobiography of Bian Que from around 400–500 BC references inserting needles at designated areas. Bian Que believed there was a single acupuncture point at the top of one's skull that he called the point "of the hundred meetings." Texts dated to be from 156 to 186 BC document early beliefs in channels of life force energy called meridians that would later be an element in early acupuncture beliefs.

Ramey and Buell said the "practice and theoretical underpinnings" of modern acupuncture were introduced in The Yellow Emperor's Classic (Huangdi Neijing) around 100 BC. It introduced the concept of using acupuncture to manipulate the flow of life energy (qi) in a network of meridian (channels) in the body. The network concept was made up of acu-tracts, such as a line down the arms, where it said acupoints were located. Some of the sites acupuncturists use needles at today still have the same names as those given to them by the Yellow Emperor's Classic. Numerous additional documents were published over the centuries introducing new acupoints. By the 4th century AD, most of the acupuncture sites in use today had been named and identified.

Early development in China

Establishment and growth

In the first half of the 1st century AD, acupuncturists began promoting the belief that acupuncture's effectiveness was influenced by the time of day or night, the lunar cycle, and the season. The 'science of the yin-yang cycles' (運氣學 yùn qì xué) was a set of beliefs that curing diseases relied on the alignment of both heavenly (tian) and earthly (di) forces that were attuned to cycles like that of the sun and moon. There were several different belief systems that relied on a number of celestial and earthly bodies or elements that rotated and only became aligned at certain times. According to Needham and Lu, these "arbitrary predictions" were depicted by acupuncturists in complex charts and through a set of special terminology.

Acupuncture needles during this period were much thicker than most modern ones and often resulted in infection. Infection is caused by a lack of sterilization, but at that time it was believed to be caused by use of the wrong needle, or needling in the wrong place, or at the wrong time. Later, many needles were heated in boiling water, or in a flame. Sometimes needles were used while they were still hot, creating a cauterizing effect at the injection site. Nine needles were recommended in the Great Compendium of Acupuncture and Moxibustion from 1601, which may have been because of an ancient Chinese belief that nine was a magic number.

Other belief systems were based on the idea that the human body operated on a rhythm and acupuncture had to be applied at the right point in the rhythm to be effective. In some cases a lack of balance between Yin and Yang were believed to be the cause of disease.

In the 1st century AD, many of the first books about acupuncture were published and recognized acupuncturist experts began to emerge. The Zhen Jiu Jia Yi Jing, which was published in the mid-3rd century, became the oldest acupuncture book that is still in existence in the modern era. Other books like the Yu Gui Zhen Jing, written by the Director of Medical Services for China, were also influential during this period, but were not preserved. In the mid 7th century, Sun Simiao published acupuncture-related diagrams and charts that established standardized methods for finding acupuncture sites on people of different sizes and categorized acupuncture sites in a set of modules.

Acupuncture became more established in China as improvements in paper led to the publication of more acupuncture books. The Imperial Medical Service and the Imperial Medical College, which both supported acupuncture, became more established and created medical colleges in every province. The public was also exposed to stories about royal figures being cured of their diseases by prominent acupuncturists. By time the Great Compendium of Acupuncture and Moxibustion was published during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644 AD), most of the acupuncture practices used in the modern era had been established.

Decline

By the end of the Song dynasty (1279 AD), acupuncture had lost much of its status in China. It became rarer in the following centuries, and was associated with less prestigious professions like alchemy, shamanism, midwifery and moxibustion. Additionally, by the 18th century, scientific rationality was becoming more popular than traditional superstitious beliefs. By 1757 a book documenting the history of Chinese medicine called acupuncture a "lost art". Its decline was attributed in part to the popularity of prescriptions and medications, as well as its association with the lower classes.

In 1822, the Chinese Emperor signed a decree excluding the practice of acupuncture from the Imperial Medical Institute. He said it was unfit for practice by gentlemen-scholars. In China acupuncture was increasingly associated with lower-class, illiterate practitioners. It was restored for a time, but banned again in 1929 in favor of science-based medicine. Although acupuncture declined in China during this time period, it was also growing in popularity in other countries.

International expansion

Korea is believed to be the first country in Asia that acupuncture spread to outside of China. Within Korea there is a legend that acupuncture was developed by emperor Dangun, though it is more likely to have been brought into Korea from a Chinese colonial prefecture in 514 AD. Acupuncture use was commonplace in Korea by the 6th century. It spread to Vietnam in the 8th and 9th centuries. As Vietnam began trading with Japan and China around the 9th century, it was influenced by their acupuncture practices as well. China and Korea sent "medical missionaries" that spread traditional Chinese medicine to Japan, starting around 219 AD. In 553, several Korean and Chinese citizens were appointed to re-organize medical education in Japan and they incorporated acupuncture as part of that system. Japan later sent students back to China and established acupuncture as one of five divisions of the Chinese State Medical Administration System.

Acupuncture began to spread to Europe in the second half of the 17th century. Around this time the surgeon-general of the Dutch East India Company met Japanese and Chinese acupuncture practitioners and later encouraged Europeans to further investigate it. He published the first in-depth description of acupuncture for the European audience and created the term "acupuncture" in his 1683 work De Acupunctura. France was an early adopter among the West due to the influence of Jesuit missionaries, who brought the practice to French clinics in the 16th century. The French doctor Louis Berlioz (the father of the composer Hector Berlioz) is usually credited with being the first to experiment with the procedure in Europe in 1810, before publishing his findings in 1816.

By the 19th century, acupuncture had become commonplace in many areas of the world. Americans and Britons began showing interest in acupuncture in the early 19th century, although interest waned by mid-century. Western practitioners abandoned acupuncture's traditional beliefs in spiritual energy, pulse diagnosis, and the cycles of the moon, sun or the body's rhythm. Diagrams of the flow of spiritual energy, for example, conflicted with the West's own anatomical diagrams. It adopted a new set of ideas for acupuncture based on tapping needles into nerves. In Europe it was speculated that acupuncture may allow or prevent the flow of electricity in the body, as electrical pulses were found to make a frog's leg twitch after death.

The West eventually created a belief system based on Travell trigger points that were believed to inhibit pain. They were in the same locations as China's spiritually identified acupuncture points, but under a different nomenclature. The first elaborate Western treatise on acupuncture was published in 1683 by Willem ten Rhijne.

Modern era

In China, the popularity of acupuncture rebounded in 1949 when Mao Zedong took power and sought to unite China behind traditional cultural values. It was also during this time that many Eastern medical practices were consolidated under the name traditional Chinese medicine (TCM).

New practices were adopted in the 20th century, such as using a cluster of needles, electrified needles, or leaving needles inserted for up to a week. A lot of emphasis developed on using acupuncture on the ear. Acupuncture research organizations such as the International Society of Acupuncture were founded in the 1940s and 1950s and acupuncture services became available in modern hospitals. China, where acupuncture was believed to have originated, was increasingly influenced by Western medicine. Meanwhile, acupuncture grew in popularity in the US. The US Congress created the Office of Alternative Medicine in 1992 and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) declared support for acupuncture for some conditions in November 1997. In 1999, the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine was created within the NIH. Acupuncture became the most popular alternative medicine in the US.

Politicians from the Chinese Communist Party said acupuncture was superstitious and conflicted with the party's commitment to science. Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong later reversed this position, arguing that the practice was based on scientific principles. During the Cultural Revolution, disbelief in acupuncture anesthesia was subjected to ruthless political repression.

In 1971, New York Times reporter James Reston published an article on his acupuncture experiences in China, which led to more investigation of and support for acupuncture. The US President Richard Nixon visited China in 1972. During one part of the visit, the delegation was shown a patient undergoing major surgery while fully awake, ostensibly receiving acupuncture rather than anesthesia. Later it was found that the patients selected for the surgery had both a high pain tolerance and received heavy indoctrination before the operation; these demonstration cases were also frequently receiving morphine surreptitiously through an intravenous drip that observers were told contained only fluids and nutrients. One patient receiving open heart surgery while awake was ultimately found to have received a combination of three powerful sedatives as well as large injections of a local anesthetic into the wound. After the National Institute of Health expressed support for acupuncture for a limited number of conditions, adoption in the US grew further. In 1972 the first legal acupuncture center in the US was established in Washington DC and in 1973 the American Internal Revenue Service allowed acupuncture to be deducted as a medical expense.

In 2006, a BBC documentary Alternative Medicine filmed a patient undergoing open heart surgery allegedly under acupuncture-induced anesthesia. It was later revealed that the patient had been given a cocktail of anesthetics.

In 2010, UNESCO inscribed "acupuncture and moxibustion of traditional Chinese medicine" on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List following China's nomination.

Adoption

Acupuncture is most heavily practiced in China and is popular in the US, Australia, and Europe. In Switzerland, acupuncture has become the most frequently used alternative medicine since 2004. In the United Kingdom, a total of 4 million acupuncture treatments were administered in 2009. Acupuncture is used in most pain clinics and hospices in the UK. An estimated 1 in 10 adults in Australia used acupuncture in 2004. In Japan, it is estimated that 25 percent of the population will try acupuncture at some point, though in most cases it is not covered by public health insurance. Users of acupuncture in Japan are more likely to be elderly and to have a limited education. Approximately half of users surveyed indicated a likelihood to seek such remedies in the future, while 37% did not. Less than one percent of the US population reported having used acupuncture in the early 1990s. By the early 2010s, more than 14 million Americans reported having used acupuncture as part of their health care.

In the US, acupuncture is increasingly (as of 2014) used at academic medical centers, and is usually offered through CAM centers or anesthesia and pain management services. Examples include those at Harvard University, Stanford University, Johns Hopkins University, and UCLA. CDC clinical practice guidelines from 2022 list acupuncture among the types of complementary and alternative medicines physicians should consider in preference to opioid prescription for certain kinds of pain.

The use of acupuncture in Germany increased by 20% in 2007, after the German acupuncture trials supported its efficacy for certain uses. In 2011, there were more than one million users, and insurance companies have estimated that two-thirds of German users are women. As a result of the trials, German public health insurers began to cover acupuncture for chronic low back pain and osteoarthritis of the knee, but not tension headache or migraine. This decision was based in part on socio-political reasons. Some insurers in Germany chose to stop reimbursement of acupuncture because of the trials. For other conditions, insurers in Germany were not convinced that acupuncture had adequate benefits over usual care or sham treatments. Highlighting the results of the placebo group, researchers refused to accept a placebo therapy as efficient.

Regulation

Main article: Regulation of acupunctureThere are various government and trade association regulatory bodies for acupuncture in the United Kingdom, the United States, Saudi Arabia, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Canada, and in European countries and elsewhere. The World Health Organization recommends that an acupuncturist receive 200 hours of specialized training if they are a physician and 2,500 hours for non-physicians before being licensed or certified; many governments have adopted similar standards.

In Hong Kong, the practice of acupuncture is regulated by the Chinese Medicine Council, which was formed in 1999 by the Legislative Council. It includes a licensing exam, registration, and degree courses approved by the board. Canada has acupuncture licensing programs in the provinces of British Columbia, Ontario, Alberta and Quebec; standards set by the Chinese Medicine and Acupuncture Association of Canada are used in provinces without government regulation. Regulation in the US began in the 1970s in California, which was eventually followed by every state but Wyoming and Idaho. Licensing requirements vary greatly from state to state. The needles used in acupuncture are regulated in the US by the Food and Drug Administration. In some states acupuncture is regulated by a board of medical examiners, while in others by the board of licensing, health or education.

In Japan, acupuncturists are licensed by the Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare after passing an examination and graduating from a technical school or university. In Australia, the Chinese Medicine Board of Australia regulates acupuncture, among other Chinese medical traditions, and restricts the use of titles like 'acupuncturist' to registered practitioners only. The practice of Acupuncture in New Zealand in 1990 acupuncture was included into the Governmental Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC) Act. This inclusion granted qualified and professionally registered acupuncturists the ability to provide subsidised care and treatment to citizens, residents, and temporary visitors for work- or sports-related injuries that occurred within the country of New Zealand. The two bodies for the regulation of acupuncture and attainment of ACC treatment provider status in New Zealand are Acupuncture NZ, and The New Zealand Acupuncture Standards Authority. At least 28 countries in Europe have professional associations for acupuncturists. In France, the Académie Nationale de Médecine (National Academy of Medicine) has regulated acupuncture since 1955.

See also

- Auriculotherapy

- Baunscheidtism

- Colorpuncture

- Dry needling

- List of acupuncture points

- List of ineffective cancer treatments – Includes moxibustion

- Moxibustion

- Pharmacopuncture

- Pressure point

- Regulation of acupuncture

Notes

- The word "needle" can be written with either of the two characters 針 or 鍼 in traditional contexts.

- From the Latin acus (needle) and punctura (to puncture).

- ^ Attributed to multiple sources:

- ^ Singh & Ernst (2008) stated, "Scientists are still unable to find a shred of evidence to support the existence of meridians or Ch'i", "The traditional principles of acupuncture are deeply flawed, as there is no evidence at all to demonstrate the existence of Ch'i or meridians" and "As yin and yang, acupuncture points and meridians are not a reality, but merely the product of an ancient Chinese philosophy".

- A reference to the five movements and six qi (五運六氣 wǔ yùn liù qì).

- simplified Chinese: 针灸大成; traditional Chinese: 針灸大成; pinyin: Zhēn jiǔ dà chéng; Wade–Giles: Chen Chiu Ta Chʻeng.

- simplified Chinese: 针灸甲乙经; traditional Chinese: 針灸甲乙經; pinyin: Zhēn jiǔ jiǎ yǐ jīng.

- simplified Chinese: 玉匮针经; traditional Chinese: 玉匱鍼經; pinyin: Yù guì zhēn jīng; Wade–Giles: Yü Kuei Chen Ching.

References

- Pyne D, Shenker NG (August 2008). "Demystifying acupuncture". Rheumatology. 47 (8): 1132–36. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ken161. PMID 18460551.

- ^ Berman BM, Langevin HM, Witt CM, Dubner R (July 2010). "Acupuncture for chronic low back pain". The New England Journal of Medicine. 363 (5): 454–61. doi:10.1056/NEJMct0806114. PMID 20818865. S2CID 10129706.

- ^ Adams D, Cheng F, Jou H, Aung S, Yasui Y, Vohra S (December 2011). "The safety of pediatric acupuncture: a systematic review". Pediatrics. 128 (6): e1575–87. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-1091. PMID 22106073. S2CID 46502395.

- Baran GR, Kiana MF, Samuel SP (2014). "Science, Pseudoscience, and Not Science: How do They Differ?". Healthcare and Biomedical Technology in the 21st Century. Springer. pp. 19–57. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-8541-4_2. ISBN 978-1-4614-8540-7.

various pseudosciences maintain their popularity in our society: acupuncture, astrology, homeopathy, etc.

- Good R (2012). "Chapter 5: Why the Study of Pseudoscience Should Be Included in Nature of Science Studies". In Khine MS (ed.). Advances in Nature of Science Research: Concepts and Methodologies. Springer. p. 103. ISBN 978-94-007-2457-0. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

Believing in something like chiropractic or acupuncture really can help relieve pain to a small degree but many related claims of medical cures by these pseudosciences are bogus.

- ^ Barrett, S (30 December 2007). "Be Wary of Acupuncture, Qigong, and "Chinese Medicine"". Quackwatch. Archived from the original on 2 June 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ^ de las Peñas CF, Arendt-Nielsen L, Gerwin RD (2010). Tension-type and cervicogenic headache: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 251–54. ISBN 978-0763752835. Archived from the original on 4 February 2023. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ Ernst E (February 2006). "Acupuncture – a critical analysis". Journal of Internal Medicine. 259 (2): 125–37. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01584.x. PMID 16420542. S2CID 22052509.

- Ahn, Chang-Beohm; Jang, Kyung-Jun; Yoon, Hyun-Min; Kim, Cheol-Hong; Min, Young-Kwang; Song, Chun-Ho; Lee, Jang-Cheon (1 December 2009). "A Study of the Sa-Ahm Five Element Acupuncture Theory". Journal of Acupuncture and Meridian Studies. 2 (4): 309–320. doi:10.1016/S2005-2901(09)60074-1. ISSN 2005-2901. PMID 20633508.

- "Syndrome differentiation according to the eight principles". www.shen-nong.com. Shen-nong Limited. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ Ernst E, Lee MS, Choi TY (April 2011). "Acupuncture: does it alleviate pain and are there serious risks? A review of reviews" (PDF). Pain. 152 (4): 755–64. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.004. PMID 21440191. S2CID 20205666. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2017. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- ^ "Acupuncture for Pain". NCCIH. January 2008. Archived from the original on 11 October 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ^ Hutchinson AJ, Ball S, Andrews JC, Jones GG (October 2012). "The effectiveness of acupuncture in treating chronic non-specific low back pain: a systematic review of the literature". Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research. 7 (1): 36. doi:10.1186/1749-799X-7-36. PMC 3563482. PMID 23111099.

- "Acupuncture Market Share, Size Global Industry Revenue, Business Growth, Demand and Applications Market Research Report to 2023". MarketWatch. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ Allen J, Mak SS, Begashaw M, Larkin J, Miake-Lye I, Beroes-Severin J, Olson J, Shekelle PG (November 2022). "Use of Acupuncture for Adult Health Conditions, 2013 to 2021: A Systematic Review". JAMA Netw Open (Systematic review). 5 (11): e2243665. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.43665. PMC 9685495. PMID 36416820.

Despite the large literature on acupuncture, most reviews concluded that their confidence in the effect was limited.

- ^ Novella S (14 December 2022). "Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews of Acupuncture". Science-Based Medicine. Archived from the original on 15 December 2022. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ Xu S, Wang L, Cooper E, Zhang M, Manheimer E, Berman B, Shen X, Lao L (2013). "Adverse events of acupuncture: a systematic review of case reports". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013: 1–15. doi:10.1155/2013/581203. PMC 3616356. PMID 23573135.

- ^ "Acupuncture – for health professionals (PDQ)". National Cancer Institute. 23 September 2005. Archived from the original on 17 July 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ^ Gnatta JR, Kurebayashi LF, Paes da Silva MJ (February 2013). "Atypical mycobacterias associated to acupuncuture: an integrative review". Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem. 21 (1): 450–58. doi:10.1590/s0104-11692013000100022. PMID 23546331.

- Singh & Ernst 2008, p. 72

- Singh & Ernst 2008, p. 107

- Singh & Ernst 2008, p. 387

- ^ Ahn AC, Colbert AP, Anderson BJ, Martinsen OG, Hammerschlag R, Cina S, Wayne PM, Langevin HM (May 2008). "Electrical properties of acupuncture points and meridians: a systematic review" (PDF). Bioelectromagnetics. 29 (4): 245–56. doi:10.1002/bem.20403. PMID 18240287. S2CID 7001749. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ Mann, F (2000). Reinventing Acupuncture: A New Concept of Ancient Medicine. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0750648578.

- ^ Williams, WF (2013). "Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience: From Alien Abductions to Zone Therapy". Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience. Routledge. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-1135955229.

- ^ White A, Ernst E (May 2004). "A brief history of acupuncture". Rheumatology. 43 (5): 662–63. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keg005. PMID 15103027.

- ^ Prioreschi, P (2004). A history of Medicine, Volume 2. Horatius Press. pp. 147–48. ISBN 978-1888456011.

- ^ Lu GD, Needham J (2002). Celestial Lancets: A History and Rationale of Acupuncture and Moxa. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0700714582.

- ^ Bannan, Andrew (2013). "18:Acupuncture in Physiotherapy". In Porter, Stuart B (ed.). Tidy's Physiotherapy15: Tidy's Physiotherapy. Churchill Livingstone. Elsevier. p. 403. ISBN 978-0-7020-4344-4.

- ^ Jackson, M. (2011). The Oxford Handbook of the History of Medicine. Oxford Handbooks in History. OUP Oxford. p. 610. ISBN 978-0-19-954649-7.

- Benzon HT, Connis RT, De Leon-Casasola OA, Glass DD, Korevaar WC, Cynwyd B, Mekhail NA, Merrill DG, Nickinovich DG, Rathmell JP, Sang CN, Simon DL (April 2010). "Practice guidelines for chronic pain management: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Chronic Pain Management and the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine". Anesthesiology. 112 (4): 810–33. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181c43103. PMID 20124882.

- "What you can expect". Mayo Clinic Staff. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. January 2012. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- Schwartz, L (2000). "Evidence-Based Medicine And Traditional Chinese Medicine: Not Mutually Exclusive". Medical Acupuncture. 12 (1): 38–41. Archived from the original on 21 November 2001.

- Birch S (2011). Japanese Pediatric Acupuncture. Thieme. ISBN 978-3131500618.

- Wernicke T (2014). The Art of Non-Invasive Paediatric Acupuncture. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. ISBN 978-1848191600.

- ^ Young, J (2007). Complementary Medicine For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 126–28. ISBN 978-0470519684.

- Napadow V, Kaptchuk TJ (June 2004). "Patient characteristics for outpatient acupuncture in Beijing, China". Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 10 (3): 565–72. doi:10.1089/1075553041323849. PMID 15253864. S2CID 2094918.

- Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Eisenberg DM, Erro J, Hrbek A, Deyo RA (2005). "The practice of acupuncture: who are the providers and what do they do?". Annals of Family Medicine. 3 (2): 151–58. doi:10.1370/afm.248. PMC 1466855. PMID 15798042.

- ^ "Acupuncture". NHSChoices. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ Wheway J, Agbabiaka TB, Ernst E (January 2012). "Patient safety incidents from acupuncture treatments: a review of reports to the National Patient Safety Agency". The International Journal of Risk & Safety in Medicine. 24 (3): 163–69. doi:10.3233/JRS-2012-0569. PMID 22936058.

- White A, Cummings M, Filshie J (2008). "2". An Introduction to Western Medical Acupuncture. Churchill Livingstone. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-443-07177-5.

- Miller's Anesthesia. Elsevier. 2014. p. 1235. ISBN 978-0702052835.

- ^ Cheng, 1987, chapter 12.

- ^ Hicks A (2005). The Acupuncture Handbook: How Acupuncture Works and How It Can Help You (1 ed.). Piatkus Books. p. 41. ISBN 978-0749924720.

- Collinge WJ (1996). The American Holistic Health Association Complete guide to alternative medicine. New York: Warner Books. ISBN 978-0-446-67258-0.

- Department of Consumer Affairs, California Acupuncture Board. Title 16, Article 5. Standards of Practice, 1399.454. Single Use Needles. www.acupuncture.ca.gov/pubs_forms/laws_regs/art5.shtml 1-10-2020.

- ^ Aung & Chen, 2007, p. 116.

- Ellis A, Wiseman N, Boss K (1991). Fundamentals of Chinese Acupuncture. Paradigm Publications. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0912111339.

- ^ Aung & Chen, 2007, pp. 113–14.

- Loyeung BY, Cobbin DM (2013). "Investigating the effects of three needling parameters (manipulation, retention time, and insertion site) on needling sensation and pain profiles: a study of eight deep needling interventions". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013: 1–12. doi:10.1155/2013/136763. PMC 3789497. PMID 24159337.

- ^ Aung S, Chen W (2007). Clinical Introduction to Medical Acupuncture. Thieme. p. 116. ISBN 978-1588902214.

- Lee EJ, Frazier SK (October 2011). "The efficacy of acupressure for symptom management: a systematic review". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 42 (4): 589–603. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.01.007. PMC 3154967. PMID 21531533.

- Needham & Lu, 2002, pp. 170–73 Archived 28 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- "British Cupping Society". Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- Farlex (2012). "Tui na". Farlex. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ Colquhoun D, Novella SP (June 2013). "Acupuncture is theatrical placebo" (PDF). Anesthesia and Analgesia. 116 (6): 1360–63. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e31828f2d5e. PMID 23709076. S2CID 207135491. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- Yan Cl (1997). The Treatment of External Diseases with Acupuncture and Moxibustion. Blue Poppy Enterprises, Inc. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-936185-80-4.

- "Sonopuncture". Educational Opportunities in Integrative Medicine. The Hunter Press. 2008. p. 34. ISBN 978-0977655243.

- Bhagat (2004). Alternative Therapies. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers. pp. 164–65. ISBN 978-8180612206.

- "Sonopuncture". American Cancer Society's Guide to complementary and alternative cancer methods. American Cancer Society. 2000. p. 158. ISBN 978-0944235249.

- "Cancer Dictionary – Acupuncture point injection". National Cancer Institute. 2 February 2011. Archived from the original on 27 March 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- Sha T, Gao LL, Zhang CH, Zheng JG, Meng ZH (October 2016). "An update on acupuncture point injection". QJM. 109 (10): 639–41. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcw055. PMID 27083985.

- ^ Barrett, Stephen (2 February 2008). "Auriculotherapy: A Skeptical Look". Acupuncture Watch. Archived from the original on 28 May 2019. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- Braverman S (2004). "Medical Acupuncture Review: Safety, Efficacy, And Treatment Practices". Medical Acupuncture. 15 (3). Archived from the original on 27 March 2005.

- Isaacs N (13 December 2007). "Hold the Chemicals, Bring on the Needles". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 August 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- Lim SM, Lee SH (July 2015). "Effectiveness of bee venom acupuncture in alleviating post-stroke shoulder pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Integrative Medicine. 13 (4): 241–47. doi:10.1016/S2095-4964(15)60178-9. PMID 26165368.

- Habacher G, Pittler MH, Ernst E (2006). "Effectiveness of acupuncture in veterinary medicine: systematic review". Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 20 (3): 480–88. doi:10.1111/j.1939-1676.2006.tb02885.x. PMID 16734078.

- ^ White AR, Filshie J, Cummings TM (December 2001). "Clinical trials of acupuncture: consensus recommendations for optimal treatment, sham controls and blinding". Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 9 (4): 237–45. doi:10.1054/ctim.2001.0489. PMID 12184353. S2CID 4479335.

- Witt CM, Aickin M, Baca T, Cherkin D, Haan MN, Hammerschlag R, Hao JJ, Kaplan GA, Lao L, McKay T, Pierce B, Riley D, Ritenbaugh C, Thorpe K, Tunis S, Weissberg J, Berman BM (September 2012). "Effectiveness Guidance Document (EGD) for acupuncture research – a consensus document for conducting trials". BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 12 (1): 148. doi:10.1186/1472-6882-12-148. PMC 3495216. PMID 22953730.

- ^ Ernst E, Pittler MH, Wider B, Boddy K (2007). "Acupuncture: its evidence-base is changing". The American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 35 (1): 21–25. doi:10.1142/S0192415X07004588. PMID 17265547. S2CID 40080937.

- Johnson MI (June 2006). "The clinical effectiveness of acupuncture for pain relief – you can be certain of uncertainty". Acupuncture in Medicine. 24 (2): 71–79. doi:10.1136/aim.24.2.71. PMID 16783282. S2CID 23222288.

- Madsen 2009, p. a3115

- ^ Amezaga Urruela M, Suarez-Almazor ME (December 2012). "Acupuncture in the treatment of rheumatic diseases". Current Rheumatology Reports. 14 (6): 589–97. doi:10.1007/s11926-012-0295-x. PMC 3691014. PMID 23055010.

- ^ Langevin HM, Wayne PM, Macpherson H, Schnyer R, Milley RM, Napadow V, Lao L, Park J, Harris RE, Cohen M, Sherman KJ, Haramati A, Hammerschlag R (2011). "Paradoxes in acupuncture research: strategies for moving forward". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011: 1–11. doi:10.1155/2011/180805. PMC 2957136. PMID 20976074.

- Paterson C, Dieppe P (May 2005). "Characteristic and incidental (placebo) effects in complex interventions such as acupuncture". BMJ. 330 (7501): 1202–05. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7501.1202. PMC 558023. PMID 15905259.

- ^ Gorski DH (October 2014). "Integrative oncology: really the best of both worlds?". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 14 (10): 692–700. doi:10.1038/nrc3822. PMID 25230880. S2CID 33539406.

- ^ MacPherson H, Maschino AC, Lewith G, Foster NE, Witt CM, Witt C, Vickers AJ (2013). Eldabe S (ed.). "Characteristics of acupuncture treatment associated with outcome: an individual patient meta-analysis of 17,922 patients with chronic pain in randomised controlled trials". PLOS ONE. 8 (10): e77438. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...877438M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0077438. PMC 3795671. PMID 24146995.

- ^ Cherniack EP (April 2010). "Would the elderly be better off if they were given more placebos?". Geriatrics & Gerontology International. 10 (2): 131–37. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0594.2009.00580.x. PMID 20100289. S2CID 36539535.

- Posadzki P, Alotaibi A, Ernst E (December 2012). "Prevalence of use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) by physicians in the UK: a systematic review of surveys". Clinical Medicine. 12 (6): 505–12. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.12-6-505. PMC 5922587. PMID 23342401.

- Wang SM, Kain ZN, White PF (February 2008). "Acupuncture analgesia: II. Clinical considerations". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 106 (2): 611–21, table of contents. doi:10.1213/ane.0b013e318160644d. PMID 18227323. S2CID 24912939.

- Goldman L, Schafer AI (21 April 2015). Goldman-Cecil Medicine: Expert Consult – Online. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-323-32285-0.

- Lee A, Copas JB, Henmi M, Gin T, Chung RC (September 2006). "Publication bias affected the estimate of postoperative nausea in an acupoint stimulation systematic review". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 59 (9): 980–83. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.02.003. PMID 16895822.

- Tang JL, Zhan SY, Ernst E (July 1999). "Review of randomised controlled trials of traditional Chinese medicine". BMJ. 319 (7203): 160–61. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7203.160. PMC 28166. PMID 10406751.

- Vickers A, Goyal N, Harland R, Rees R (April 1998). "Do certain countries produce only positive results? A systematic review of controlled trials". Controlled Clinical Trials. 19 (2): 159–66. doi:10.1016/S0197-2456(97)00150-5. PMID 9551280. S2CID 18860471.

- ^ He J, Du L, Liu G, Fu J, He X, Yu J, Shang L (May 2011). "Quality assessment of reporting of randomization, allocation concealment, and blinding in traditional Chinese medicine RCTs: a review of 3159 RCTs identified from 260 systematic reviews". Trials. 12 (1): 122. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-12-122. PMC 3114769. PMID 21569452.

- Ernst E (February 2012). "Acupuncture: what does the most reliable evidence tell us? An update". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 43 (2): e11–13. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.11.001. PMID 22248792.

- Ma B, Qi GQ, Lin XT, Wang T, Chen ZM, Yang KH (September 2012). "Epidemiology, quality, and reporting characteristics of systematic reviews of acupuncture interventions published in Chinese journals". Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 18 (9): 813–17. doi:10.1089/acm.2011.0274. PMID 22924413.

- Su CX, Han M, Ren J, Li WY, Yue SJ, Hao YF, Liu JP (January 2015). "Empirical evidence for outcome reporting bias in randomized clinical trials of acupuncture: comparison of registered records and subsequent publications". Trials. 16 (1): 28. doi:10.1186/s13063-014-0545-5. PMC 4320495. PMID 25626862.

- Salzberg, Steven. "Fake Medical Journals Are Spreading, And They Are Filled With Bad Science". Forbes. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- Ernst E (April 2009). "Acupuncture: what does the most reliable evidence tell us?". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 37 (4): 709–14. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.04.009. PMID 18789644.

- ^ Bergqvist D (February 2013). "Vascular injuries caused by acupuncture. A systematic review". International Angiology. 32 (1): 1–8. PMID 23435388. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ Ernst E, Zhang J (June 2011). "Cardiac tamponade caused by acupuncture: a review of the literature". International Journal of Cardiology. 149 (3): 287–89. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.10.016. PMID 21093944.