| Sretensk | |

|---|---|

| Prisoner-of-war camp | |

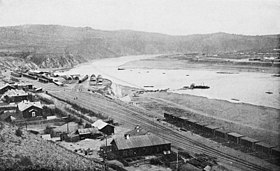

Sretensk in 1917 Sretensk in 1917 | |

| |

| Coordinates | 52°15′N 117°43′E / 52.250°N 117.717°E / 52.250; 117.717 |

| Location | Sretensk, Russia |

| Operated by | Russia |

| Operational | 1914–1921 |

| Inmates | Mainly Germans, Austro-Hungarians |

Sretensk was a Russian prisoner-of-war camp established in October 1914 with the intent of housing Central Powers' troops captured during the course of World War I. The camp was situated in the city of Sretensk and combined barracks and private residences to house the internees. The internal affairs of the camp were regulated by a committee of interned officers and the camp authorities. Between December 1915 and March 1916 the camp was affected by a typhus epidemic. Following the abdication of Nicholas II of Russia in February 1917, conditions in the camp worsened. A number of prisoners joined rival factions during the Russian Civil War while those who remained came under fire when the fighting spread to the camp. The last prisoners were evacuated from the camp in the middle of 1921.

Background

The 28 June 1914 assassination of Austro-Hungarian heir presumptive Archduke Franz Ferdinand precipitated Austria-Hungary's declaration of war against Serbia. The conflict quickly attracted the involvement of all major European countries, pitting the Central Powers against the Entente coalition and starting World War I. Russia fought on the side of the Entente, engaging the German Empire and Austria-Hungary on the Eastern Front. Russia took its first prisoners of war during the course of its invasion of East Prussia and the Battle of Galicia in August–September 1914.

Camp

The Sretensk prisoner-of-war camp was established in October 1914 with the intent of housing captured German and Austro-Hungarian troops. Sretensk was among the 10 camps established in the Zabaykalsky Oblast, the others being Chita, Nerchinsk, Troitskosavsk, Verkhneudinsk, Barguzin, Peschanka, Dauria, Antipicha and Berezovka. The camps were not camps in the strictest sense but rather housing projects within preexisting settlements dedicated to the internment of prisoners. As of 14 October 1914, Sretensk housed around 1,000 prisoners. By the end of 1915 the number had risen to 11,000. In contrast, the city's permanent population numbered only 7,000. The majority of the prisoners were held in the barracks of the 16th Siberian Infantry Regiment and the railway station barracks. A small number of high ranking officers settled in private houses due to the lack of available quarters. The camp was guarded by the 719th Ufa Infantry Druzhina as the town's former garrison had departed for the frontlines.

At first foreign officers were allowed to venture through the town freely visiting the local coffee shop and billiards club, but this was put to an end by an order dated 23 October 1914. Nevertheless, officers lived a relatively comfortable life, receiving at least 50 rubles per year depending on their rank, allowing them to acquire products from the local marketplace. They were assisted by batmen who acted as cooks and servants. The order also put into place an officers committee, tasked with maintaining order, regulating the health services, security, leisure, and religious life of the prisoners in conjunction with the camp authorities. Lutheran and Catholic Christians held services in a wooden church of their own construction, while Jews were permitted to practice in a separate room with the help of the town's rabbi. The committee organized football, tennis, volleyball, weightlifting, athletics competitions, with an orchestra and a theater supplementing them. The committee also regulated the postage service and the distribution of aid from the Red Cross and other humanitarian organizations. With the entry of the Ottoman Empire into the war, the camp began receiving prisoners captured during the Caucasus Campaign. In early 1915, Sretensk received a group of 43 Ottomans, among whom were some Armenians. The absence of Turkish speaking translators complicated their internment and led to the 1917 transfer of Ottoman prisoners to the Dauria camp.

The combination of extreme climatic conditions, contacts with civilians, the density of the population in the barracks and poor organization led to the first outbreak of typhus in December 1915. In February 1916, a quarantine was enforced and sick prisoners were transferred either to the hospital or separate barracks. The epidemic was subdued in March with the help of two Swedish Red Cross sisters of mercy who had arrived two months earlier. In order to further isolate the healthy from the sick, healthy prisoners formed groups which were employed in the local agricultural sector. Productivity improved rapidly once the work became paid. The spectrum of employment opportunities gradually expanded to include the telegraph–post service, railroad maintenance, leather work, logging, photo ateliers, mills, construction work, production of building materials and soap. The influx of cheap labor greatly benefited the local economy. Over time the camp was visited by delegations from the Danish and Swedish Red Cross as well as the American embassy. The commander of the Zabaykalsk gendarmerie believed the Swedish Red Cross mission to be motivated by intelligence gathering rather than humanitarian concerns. Reports issued by the delegation attested to the upholding of the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907.

Dissolution

Following the abdication of Czar Nicholas II of Russia in February 1917, conditions within the camp turned for the worse. Rations were reduced and the supply of clothing and medication limited to the point of distributing the clothes of dead internees to their comrades. The outbreak of the October Revolution of 1917 marked the beginning of the Russian Civil War, making the internees almost entirely dependent on the help of the Red Cross. On 3 March 1918, the Bolsheviks signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, ending Russia's participation in World War I. At the same time Adolf Osipovich a local Bolshevik agitator began his propaganda campaign in the camp. A number of Hungarian internees were persuaded by his appeals to world revolution and joined the Bolshevik International Battalions. German and Austrian prisoners on the other hand enlisted into units under the command of Grigory Semyonov and Roman von Ungern-Sternberg, who belonged to the rival white movement. However, the majority of the prisoners remained neutral, awaiting their release. In early 1920, a Bolshevik unit under Ivan Fadeev took cover in the camp's barracks leading to numerous casualties among the internees after it became the target of a Japanese artillery bombardment. In April 1921, the remaining prisoners were transferred to Primorie, the last prisoners left for their homelands from Vladivostok in the middle of the same year. A self made memorial dedicated to the prisoners that perished in the camp was erected in the Fillipicha valley outside the camp, an inscription in Hungarian reads, "To our comrades that perished so far from the motherland. Officers and soldiers of the allied Austrian–Hungarian–German–Turkish army. 1914–1915–1916."

Footnotes

- Albertini 1953, p. 36.

- Fischer 1967, p. 73.

- ^ Ilkovskiy 2014, pp. 196–206.

- Shalamov 2015, pp. 317–323.

References

- Albertini, Luigi (1953). Origins of the War of 1914. Vol. II. Oxford: Oxford University Press. OCLC 168712.

- Ilkovskiy, Konstantin (2014). Сретенск [Sretensk] (in Russian). Chita: Zabaykalsky University Press. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- Fischer, Fritz (1967). Germany’s Aims in the First World War. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-09798-6.

- Shalamov, Vladimir (2015). "Transbaikal Healthcare System During the First World War Part I". Vestnik IrGTU. 1 (96). Irkutsk University Press: 317–323. Retrieved 8 May 2017.