| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Yoshida Shōin" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Senior Fourth RankYoshida Shōin | |

|---|---|

| 吉田 松陰 | |

| |

| Born | Sugi Toranosuke (杉 寅之助) (1830-09-20)September 20, 1830 Hagi, Nagato Province, Japan |

| Died | November 21, 1859(1859-11-21) (aged 29) Edo, Japan |

| Cause of death | Decapitation |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Other names | Torajirō (寅次郎) |

| Occupation | scholar |

| Parent(s) | Sugi Yurinosuke (father) Kodama Taki (mother) |

| Relatives | Sugi Umetarō (brother) Kodama Yoshiko (sister) Odamura Hisa (sister) Sugi Tsuya (sister) Miwako Katori (sister) Sugi Toshisaburō (brother) Tamaki Bunnoshin (uncle) Yoshida Daisuke (adoptive father) |

| Academic background | |

| Academic advisors | Yusuke Yamada Sakuma Shōzan Asaka Gonsai Miyabe Teizō Yamaga Sosui |

| Academic work | |

| Era | Edo period |

| Institutions | Meirinkan Shōka Sonjuku |

| Notable students | Takasugi Shinsaku Kido Takayoshi Akane Taketo Itō Hirobumi Kusaka Genzui Inoue Kaoru Yamagata Aritomo |

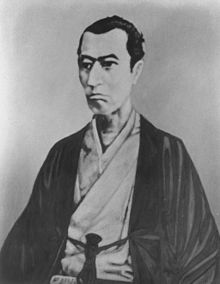

Yoshida Shōin (吉田松陰, born Sugi Toranosuke (杉 寅之助); September 20, 1830 – November 21, 1859), commonly named Torajirō (寅次郎), was one of Japan's most distinguished intellectuals in the late years of the Tokugawa shogunate. He devoted himself to nurturing many ishin shishi who in turn made major contributions to the Meiji Restoration.

Early life

Born Sugi Toranosuke in Hagi in the Chōshū region of Japan, he was the second son of Sugi Yurinosuke (1804–1865), a modest rank Samurai and his wife Kodama Taki (1807–1890). Yurinosuke had two younger brothers, Yoshida Daisuke and Tamaki Bunnoshin. Sugi Toranosuke's eldest brother was Sugi Umetarō (1828–1910), his four younger sisters were Sugi Yoshiko (later Kodama Yoshiko) (1832–1924), Sugi Hisa (later Odamura Hisa) (1839–1881), Sugi Tsuya (1841–1843), and Sugi Fumi (later Katori Miwako) (1843–1921), his youngest brother was Sugi Toshisaburō (1845–1876).

Sugi Toranosuke was later adopted at the age of four by Yoshida Daisuke and was renamed to Yoshida Shōin. The process of adopting younger sons from the Sugi house was established generations before Shoin's birth. To avoid financial insolvency, the Sugi house controlled two additional samurai lineages-the Tamaki and the Yoshida lineages. The oldest male became the Sugi heir and the younger Sugi sons were adopted by the Tamaki and Yoshida lines as their heirs-to ensure the Sugi succession was protected, this required the head of the house in the Yoshida line and most generations the Tamaki line to remain unmarried. Daisuke, already in ill health, died one year later at the age of 28, leaving Yoshida Shoin as the heir of the Yoshida lineage at five years of age. His house was also the instructor to the daimyō in military studies.

Due to Shōin's young age, four men were appointed to represent the Yoshida house as instructors. Shōin's younger uncle, Tamaki, set about accelerating Shōin's education to prepare the boy for his eventual duties to be trained as a Yamaga instructor. In 1839 at the age of 9, he was taught by a military art instructor at Meirinkan. At the age of 11, his talent was recognized for his excellent performance for his lecture to the daimyō Mōri Takachika. At the age of 13, he led the Chōshū forces to conducted a Western fleet extermination exercise.

In 1845, he received a lecture on the Naganuma Military Arts by Yusuke Yamada. In 1851, he went to Edo and studied the Western military science under Sakuma Shōzan and Asaka Gonsai. In 1851, he studied under Miyabe Teizō and Yamaga Sosui from the Higo Domain. This period of intense study suggests a formative experience that shaped Shōin into an educator and activist that helped spur the Meiji Restoration.

Rewards of Punishment

At the end of 1851, Yoshida left for a four-month trip across Northeastern Japan. He had been granted verbal permission from the Chōshū government but left before receiving his written permission in an act of defiance. This act of defiance was a serious offense known as dappan or "fleeing the han". He returned to Hagi in 1852. His punishment from the daimyō was costly but sweet for Shōin. He was stripped of his samurai status and his stipend of 57 koku with it. His father, Sugi Yurinosuke, was appointed as his guardian. Shōin was then granted 10 years of leisure in which he could study in any part of Japan that he chose.

On January 16, 1853, Yoshida Shōin was granted permission to return to Edo to continue his studies. His timing for his return to Edo turned out to coincide with Matthew Perry’s arrival in Japan.

Attempt to escape and imprisonment

Matthew Perry visited Japan in 1853 and 1854. Several months after Perry's arrival at Uraga, Sakuma Shōzan petitioned the Bakufu to allow promising candidates to go to the United States to study the ways of the West. The petition was denied but Sakuma and Shoin resolved that Shoin would stow away onboard Perry's ship to visit the west for study. Shortly before Perry left, Yoshida and a friend went to Shimoda where Perry's Black Ships were anchored, and tried to gain admittance. They first presented a letter asking to be let aboard one of his ships.

Then, in the dead of night Yoshida tried to secretly climb aboard the ship USS Powhatan. Perry's troops noticed them, and they were refused. Shortly thereafter, they were caged by Tokugawa bakufu troops. Even in a cage, they managed to smuggle a written message to Perry. Yoshida Shōin was sent to a jail in Edo, then to one in Hagi where he was sentenced to house arrest.

Yoshida had never introduced himself to Perry, who never learned his name.

While in jail, he ran a school. After his release, he took over his uncle's tiny private school, Shōka Sonjuku to teach the youth military arts and politics. Since he was forbidden from travelling, he had his students travel Japan as investigators.

By 1858, Ii Naosuke, the bakufu Tairō who signed treaties with the Western powers, began to round up sonnō jōi rebels in Kyōto, Edo, and eventually the provinces. Many of Yoshida Shoin's followers were caught up in the dragnet. That year, Yoshida Shōin put down the brush and took up the sword. When Ii Naosuke sent a servant to (unsuccessfully) ask the emperor to support one of his treaties with the foreigners, Yoshida Shōin led a revolt, calling on rōnin to aid him, but received very little support. Nonetheless, he and a small band of students attacked and attempted to kill Ii's servant in Kyoto. The revolt failed, and Yoshida Shoin was again imprisoned in Chōshū.

Death

In 1859, Chōshū was ordered to send its most dangerous insurgents to Edo's prisons. Once there, Yoshida Shōin confessed the assassination plot, and, from jail, continued to plot the rebellion. He did not expect to be executed until the Tokugawa executed three of his friends. In October 15, he asked for a piece of tissue paper to clear his nasal passage, then recited his final death poem: 'Parental love exceeds one's love for his parents. How will they take the tidings of today?'. Two days later in October 17, he was informed of his death sentence. When it was Yoshida's turn in November 21, he was brought to an open courtyard adjacent to the prison, and led to the scaffold. With perfect composure he kneeled atop a straw mat, beyond which was a rectangular hole dug in the rich, dark earth to absorb the blood. Upon his death by decapitation, his executioner Yamada Asaemon said that he died a noble death. He was 29 years old.

After his execution, he was first buried by Itō Hirobumi and his Chōshū comrades near the execution site. In 1863, he was later reburied by his supporters at Wakabayashi, Edo.

Posthumous influence

At least five of his students, Takasugi Shinsaku, Katsura Kogorō, Inoue Kaoru, Itō Hirobumi and Yamagata Aritomo later became widely known, and virtually all of the survivors of the Sonjuku group became officers in the Meiji Restoration. Takasugi led rifle companies against the shōgun's army when it failed to conquer Chōshū in 1864, rapidly leading to the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate. Itō Hirobumi became Japan's first prime minister.

Legacy

In 1882, Yoshida Shōin was enshrined at Shōin shrine in Wakabayashi, Setagaya-ku (世田谷区若林4丁目35-1), in Tokyo, and the current shrine's main building was built in 1927, as well as in his birthplace Hagi, Yamaguchi Prefecture (山口県萩市椿東1537).

In 1888 Yoshida was enshrined into the Yasukuni Shrine and was posthumously awarded Senior Fourth Rank by 1889.

Shoin University was named after him. There are two other universities whose names include Shoin in Japan, but they are unrelated to him.

Hana Moyu is a 2015 Japanese television drama NHK Taiga drama series that premiered on January 4, 2015, and ended on December 13, 2015. The series starred Mao Inoue who portrayed Sugi Fumi, a younger sister of Yoshida Shōin. The role of Yoshida Shōin was played by actor Yūsuke Iseya.

References

- ^ Huber, T. (1981). Revolutionary Origins of Modern Japan. Stanford, Ca: Stanford University Press

- "Yoshida Shōin: The Revolutionary and Teacher Who Helped Bring Down the Shogunate". nippon.com. 2015-02-04. Retrieved 2019-03-18.

- Shoin Jinja official website Retrieved December 2, 2015 (in Japanese)

- Shoin University website 建学の精神 Archived 2017-08-01 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved December 2, 2015 (in Japanese)

- Gregg, N. Taylor. "Hagi Where Japan's Revolution Began". Archived from the original on 2006-01-07. Retrieved 2005-04-04. National Geographic Magazine (June, 1984). Article Readers (1) Prof. Albert Craig; Harvard Yenching Institute, (2) Prof. History Dept., Kyoto University, (3) Prof. Thomas Huber, Duke University.

External links

- Works by or about Yoshida Shōin at the Internet Archive

- Robert Louis Stevenson on Yoshida Shōin (Yoshida Torajirō) – see .

- Yoshida Shoin – Daily quotes in English and Japanese

- yoshida-shoin.com – About Yoshida Shoin (Japanese)

- http://contentdm.lib.byu.edu/cdm/ref/collection/CivilizationUnknown/id/1277

- http://www.ndl.go.jp/portrait/e/datas/91.html

- 1830 births

- 1859 deaths

- People of Bakumatsu

- Meiji Restoration

- People executed by Japan by decapitation

- 19th-century executions by Japan

- Executed Japanese people

- Politicians from Yamaguchi Prefecture

- People from Chōshū Domain

- 19th-century Japanese philosophers

- 19th-century Japanese educators

- Deified Japanese men

- Japanese scholars of Yangming