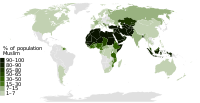

The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan is a majority Muslim country with 96% of the population following Sunni Islam while a small minority follow Shiite branches. There are also about 20,000 to 32,000 Druze living mostly in the north of Jordan, even though most Druze no longer consider themselves Muslim. Many Jordanian Muslims practice Sufism.

The 1952 Constitution grants freedom of religion while stipulating that the king and his successors must be Muslims and sons of Muslim parents. Religious minorities include Christians of various denominations (1%) and even fewer adherents of other faiths. Jordan is a religious and conservative country.

Islam in Social Life pre-1980s

Despite a strong identification with and loyalty to Islam, religious practices varied among segments of Jordan's population. This unevenness in practice did not necessarily correlate with a rural-urban division or differing levels of education. The religious observance of some Jordanians was marked by beliefs and practices that were sometimes antithetical to the teachings of Islam. Authorities attributed at least some of these elements to pre-Islamic beliefs and customs common to the area.

In daily life, neither rural dwellers nor urbanites were overly fatalistic. They did not directly hold God responsible for all occurrences; rather, they placed events in a religious context that imbued them with meaning. The expression in shari'a Allah often accompanied statements of intention, and the term bismillah (in the name of Allah) accompanied the performance of most important actions. Such pronouncements did not indicate a ceding of control over one's life or events. Jordanian Muslims generally believed that in matters that they could control, God expected them to work diligently.

Muslims have other ways of invoking God's presence in daily life. Despite Islam's unequivocal teaching that God is one and that no being resembles him in sanctity, some people accepted the notion that certain persons (saints) have baraka, a special quality of personal holiness and affinity to God. The intercession of these beings was believed to help in all manner of trouble, and shrines to such people could be found in some localities. Devotees often visited the shrine of their patron, especially seeking relief from illness or inability to have children.

Numerous spiritual creatures were believed to inhabit the world. Evil spirits known as jinn — fiery, intelligent beings that are capable of appearing in human and other forms — could cause all sorts of malicious mischief. For protection, villagers carried in their clothing bits of paper inscribed with Qur'anic verses (amulets), and they frequently pronounced the name of God. A copy of the Qur'an was said to keep a house safe from jinn. The "evil eye" also could be foiled by the same means. Although any literate Muslim was able to prepare amulets, some persons gained reputations as being particularly skilled in prescribing and preparing them. To underscore the difficulty in drawing a fine distinction between orthodox and popular Islam, one only needs note that some religious shaykhs were sought for their ability to prepare successful amulets. For example, in the 1980s in a village in northern Jordan, two elderly shaykhs (who also were brothers) were famous for their abilities in specific areas: one was skilled in warding off illness among children; the other was sought for his skills in curing infertility.

Their reverence for Islam notwithstanding, Muslims did not always practice strict adherence to the five pillars. Although most people tried to give the impression that they fulfilled their religious duties, many people did not fast during Ramadan. They generally avoided breaking the fast in public, however. In addition, most people did not contribute the required proportion of alms to support religious institutions, nor was a pilgrimage to Mecca common. Attendance at public prayers and prayer in general increased during the 1980s as part of a regional concern with strengthening Islamic values and beliefs.

Traditionally, social segregation of the sexes prevented women from participating in much of the formal religious life of the community. The 1980s brought several changes in women's religious practices. Younger women, particularly university students, were seen more often praying in the mosques and could be said to have carved a place for themselves in the public domain of Islam.

Although some women in the late 1980s resorted to unorthodox practices and beliefs, women generally were considered more religiously observant than men. They fasted more than men and prayed more regularly in the home. Education, particularly of women, diminished the folk-religious component of belief and practice and probably enhanced observance of the more orthodox aspects of Islam.

Islamic Revival 1980s onward

The 1980s witnessed a stronger and more visible adherence to Islamic customs and beliefs among significant segments of the population. The increased interest in incorporating Islam more fully into daily life was expressed in a variety of ways. Women wearing conservative Islamic dress and the headscarf were seen with greater frequency in the streets of urban as well as rural areas; men with beards also were more often seen. Attendance at Friday prayers rose, as did the number of people observing Ramadan.

Women in the 1980s, particularly university students, were actively involved in expressions of Islamic revival. Women wearing Islamic garb were a common sight at the country's universities. For example, the mosque at Yarmouk University had a large women's section. The section was usually full, and women there formed groups to study Islam. By and large, women and girls who adopted Islamic dress apparently did so of their own volition, although it was not unusual for men to insist that their sisters, wives, and daughters cover their hair in public.

The adoption of the Islamic form of dress did not signify a return to segregation of the sexes or female seclusion. Indeed, women who adopted Islamic clothing often were working women and students who interacted daily with men. They cited a lag in cultural attitudes as part of the reason for donning such dress. In other words, when dressed in Islamic garb they felt that they received more respect from and were taken more seriously by their fellow students and colleagues. Women also could move more readily in public if they were modestly attired. The increased religious observance also accounted for women's new style of dress. In the 1980s, Islamic dress did not indicate social status, particularly wealth, as it had in the past; Islamic dress was being worn by women of all classes, especially the lower and middle classes.

Several factors gave rise to increased adherence to Islamic practices. During the 1970s and 1980s, the Middle East region saw a rise of Islamism in response to the economic recession and to the failure of nationalist politics to solve regional problems. In this context, Islam was an idiom for expressing social discontent. In Jordan, opposition politics had long been forbidden, and since the 1950s the Muslim Brotherhood had been the only legal political party. These factors were exacerbated by King Hussein's public support for the shah of Iran in his confrontation with Ayatollah Khomeini and the forces of opposition, by continued relations with Egypt in the wake of the 1979 Treaty of Peace Between Egypt and Israel, and by the king's support for Iraq in the Iran–Iraq War.

Although Islamic opposition politics never became as widespread in Jordan as in Iran and Egypt, they were pervasive enough for the regime to act swiftly to bring them under its supervision. By the close of the 1970s and throughout the 1980s, government-controlled television regularly showed the king and his brother Hasan attending Friday prayers. The media granted more time to religious programs and broadcasts. Aware that the Islamic movement might become a vehicle for expressing opposition to the regime and its policies, and in a move to repair relations with Syria, in the mid-1980s the government began to promote a moderate form of Islam, denouncing fanatical and intolerant forms.

See also

- Islam by country

- Islamization of East Jerusalem under Jordanian rule

- Jordanian Interfaith Coexistence Research Center

- Nakithoun

- Religion in Jordan

References

- Pintak, Lawrence (2019). America & Islam: Soundbites, Suicide Bombs and the Road to Donald Trump. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 86. ISBN 9781788315593.

- Jonas, Margaret (2011). The Templar Spirit: The Esoteric Inspiration, Rituals and Beliefs of the Knights Templar. Temple Lodge Publishing. p. 83. ISBN 9781906999254.

often they are not regarded as being Muslim at all, nor do all the Druze consider themselves as Muslim

- ^ Metz, Helen Chapin, ed. (1991). Jordan: a country study. Washington: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 102, 109–112. OCLC 600477967.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - "Jordan's struggle with Islamism". 19 November 2007 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

| Demographics of Jordan | |

|---|---|

| Religions | |

| Ethnic groups | |

| Foreign nationals | |