| Part of a series on |

| Go |

|---|

|

| Game specifics |

|

| History and culture |

| Players and organizations |

| Computers and mathematics |

| This list is incomplete; you can help by adding missing items. (February 2011) |

Throughout history, a number of notable Go games have taken place.

Blood-vomiting game

Main article: Blood-vomiting gameThe blood-vomiting game (Japanese: 吐血の一局) was played during the Edo period of Japan, on June 27, 1835, between Honinbo Jowa (white) and Intetsu Akaboshi (black). It is noted for three brilliant moves played by Jowa, and for the premature death of the Go prodigy Intetsu Akaboshi, who died after coughing up blood onto the board after the game.

Ear-reddening game

Main article: Ear-reddening game

The ear-reddening game (Japanese: 耳赤の一局) was played during the Edo period of Japan, in 1846 between Honinbo Shusaku (black) and Inoue Gennan Inseki (white). The game contains the "ear reddening move" (move 127), so named when a doctor who had been watching the game took note of Gennan as his ears flushed red when Shusaku played the move, indicating he had become upset.

The Game of the Century

The game of the century refers to a famous game of go between Honinbo Shusai (white) and Go Seigen (black) that was played to celebrate the 60th birthday of Honinbo Shusai. The game began on October 16, 1933, and finished on January 29, 1934. Each player was given twenty-four hours of thinking time. Shusai was the doyen of the Go world, as he was the head of the famous Honinbo Go school, the most prestigious of the schools founded at the behest of Shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu at the start of the 17th century. Go Seigen was famed as a prodigy, first among a generation of young new brilliant players, and would go on to become one of the most celebrated players of the 20th century. This led newspapers to dub the match the game of the century.

The tradition at the time dictated whoever played White had the right to adjourn the game at any time, and there was no sealing of moves. This meant that Shusai, being the nominally stronger player and thus holding White, could adjourn the game whenever it was his turn to play and continue deliberating at his leisure during the adjournment. Shusai called adjournments some 13 times, all at the start of his turn to move, thus prolonging the match to a period of three months (16 October 1933 – 19 January 1934). For instance, on the eighth day of the match, Shusai played first and Go Seigen replied within two minutes. Shusai then thought for three and a half hours but only to adjourn the game. During these adjournments, Shusai would retreat home to study the game with his students.

At the start of the game, Go Seigen played what at the time was considered a shocking series of moves at the three-three, star and center points. Such unusual and innovative moves were considered by Shusai's supporters to be an insult to the Honinbo.

Shusai trailed throughout the game until, on the 13th day of the match, he made a brilliant move at W160, now celebrated, leading to his victory with a 2 point difference. It was rumored that it was not Shusai but one of his students, Maeda Nobuaki, who was the author of this ingenious move. Segoe Kensaku told a reporter this, in what he thought was an off-the-record interview. Maeda himself even hinted as much. When presented with the opportunities to debunk these rumors, Maeda neither denied nor confirmed them.

Atomic bomb game

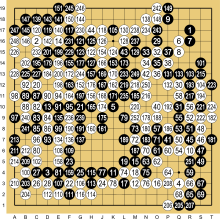

The atomic bomb Go game is a celebrated game of Go that was in progress when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, on August 6, 1945. The venue of the game was in the suburbs of Hiroshima, about 5 kilometers (3.1 mi) from ground zero.

The game was about to enter its third and final day of play when the bomb dropped at 8:15 am. The players—Utaro Hashimoto, who was the Honinbo title holder, and Kaoru Iwamoto, who was the challenger—had replayed the game to the adjourned position but had not yet started to play on. The explosion caused disruption to the game, damage to the building, and some injuries to those attending the match. Play was resumed after the lunch break, and the game was played to a conclusion that evening. Hashimoto, holding White, won by five points.

Game 1 of the match had been played from July 23 to 25 in the centre of Hiroshima. The move to further out of the city area was recommended by the police, after a drop of propaganda leaflets.

The match was continued after the war, ending in a 3–3 draw. A three-game playoff was held in 1946, won by Iwamoto in two straight games to claim the Honinbo title (becoming Honinbo Kunwa). Utaro went on to reclaim the title in 1950.

Atomic Bomb Go Game at play 106, when the bomb exploded on Hiroshima.

Lee's broken ladder game

This was a match between Lee Se-dol and Hong Chang-sik during the 2003 KAT cup. This game is notable for Lee's use of a broken ladder formation.

Normally playing out a broken ladder is a bad mistake, a pitfall associated with bad beginner play; the chasing stones are left appallingly weak. Between experts it should be decisive, leading to a lost game. Lee, playing black, defied the conventional wisdom, pushing development of the ladder to capture a large group of Hong's stones in the lower-right side of the board. Although Black could not capture the stones in the ladder, White ultimately resigned.

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Moves 67 to 74 (Black: Lee Se-dol; White: Hong Chang-sik) |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Moves 89 to 97 (Black wins when White resigns at move 211) |

AlphaGo vs Fan Hui

Main article: AlphaGo versus Fan HuiIn October 2015, the computer program AlphaGo became the first artificial intelligence program to defeat a professional Go player on a full size board and on equal terms (without handicap), when it won 5–0 against 2 dan European Champion Fan Hui. The news was announced on 27 January 2016 in order to allow publication of a scientific paper describing the algorithms used for AlphaGo. The victory gained very wide attention since this was a landmark not believed accessible to current technology, given the complexity and intuitive nature of the game, and its lack of suitability for conventional tree searches and position-evaluation based methods which had led to success in games such as chess. However it was generally believed that AlphaGo, while remarkable for a computer player, had made mistakes and would probably be unable to hold its own against a world-ranking player.

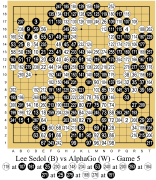

AlphaGo vs Lee Sedol

Main article: AlphaGo versus Lee SedolFive months after defeating Fan Hui, AlphaGo played a series of five games against 9 dan Lee Sedol, a South Korean professional widely considered one of the strongest and most creative players in the world. Prior to the match, in February 2016, Lee Sedol expressed confidence in winning, although acknowledging AlphaGo as a "strong player", and discussion on website GoGameGuru reported that at the time that "the majority of the world’s top players had thought to be practically impossible". The game conditions were: Chinese rules, komi (compensation points for playing second) of 7.5, 2 hours time and three 60-second byoyomi (limited time after their initial time is used). As with its previous games against Fan Hui, the tournament was on a full size board and on an equal basis. The computer won the first three games of five, Lee won the fourth, and the computer won the fifth and last game, leading to a final score of 4–1. Each of the five games played has been widely followed and analyzed. This marked the first time a computer had competed, much less won, at the highest level of the game, and each game gained worldwide coverage.

- Games 1 and 2: AlphaGo's first game victory was seen as a possible reflection on the stress facing Lee Sedol, and possible resulting mistakes he might have made. Lee Sedol had attempted to test its skill in the opening game. After AlphaGo's second victory, for which Lee played far more of a cautious "waiting" game, intended to give away few weaknesses, Lee was reported as saying "Yesterday I was surprised but today it's more than that, I am quite speechless. Today I feel like AlphaGo played a nearly perfect game.

- Game 3: After the second game, there were still strong doubts among players whether AlphaGo was truly a strong player in the sense that a human might be. The third game was described as removing that doubt; with analysts commenting that "AlphaGo won so convincingly as to remove all doubt about its strength from the minds of experienced players. In fact, it played so well that it was almost scary ... In forcing AlphaGo to withstand a very severe, one-sided attack, Lee revealed its hitherto undetected power. ... Lee wasn’t gaining enough profit from his attack. ... One of the greatest virtuosos of the middle game had just been upstaged in black and white clarity."

- Game 4: Lee played a type of extreme play, an amashi strategy, in response to AlphaGo's apparent preference for Souba Go (attempting to win by many small gains when the opportunity arises), taking territory at the perimeter rather than the center. By doing so his apparent aim was to force an "all or nothing" style of situation—a possible weakness for an opponent strong at negotiation types of play, and one which might make AlphaGo's capability of deciding slim advantages largely irrelevant. This strategy unfolded around 47, but by around 69 to 76 commentators had begun to feel Lee's play was a lost cause. However a play at White 78 was described as "a brilliant tesuji", and by Gu Li 9dan as "the hand of God" and completely unforeseen by him. The play led to Lee's first victory when AlphaGo made several bad moves in response and finally proved unable to recover during the endgame. An Younggil at GoGameGuru concluded that the game was "a masterpiece for Lee Sedol and will almost certainly become a famous game in the history of Go".

- Game 5: Exciting game which many thought would be the first countable game of the match. This game's colours were meant to be randomised, but Lee asked for black, the supposedly weaker colour in the match, for greater challenge. Despite mistakes at around move 50, AlphaGo managed to maintain a 2.5 point advantage nearing the endgame, and played a flawless endgame. Lee resigned at move 280.

Live video of the games and associated commentary was broadcast in Korean, Chinese, Japanese, and English. Chinese-language coverage of game 1 with commentary by 9-dan players Gu Li and Ke Jie was provided by Tencent and LeTV respectively, reaching about 60,000,000 viewers. Online English-language coverage presented by US 9-dan Michael Redmond and Chris Garlock, a vice-president of the American Go Association, reached an average 80,000 viewers with a peak of 100,000 viewers near the end of game 1.

References

- Seigen, Go (1999). Bridges, Patrick (ed.). Go on Go: The Analyzed Games of Go Seigen (PDF). Jim Z. Yu. p. 507. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2020.

- The Pieter Mioch Interviews - Go Seigen (part 2) at gobase.org

- The Pieter Mioch Interviews - Go Seigen (part 2) at gobase.org, p.80

- "Atomic Bomb Game at Sensei's Library". senseis.xmp.net. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- "Leaflets warning Japanese of Atomic Bomb, 1945". PBS. Retrieved 2016-03-20.

- "Atomic-bomb game at The Magic of Go". Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- "User account - Go4Go".

- "Lee Sedol - Hong Chang Sik - ladder game at Sensei's Library". senseis.xmp.net. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- "Première défaite d'un professionnel du go contre une intelligence artificielle". Le Monde (in French). 27 January 2016.

- Metz, Cade (2016-01-27). "In Major AI Breakthrough, Google System Secretly Beats Top Player at the Ancient Game of Go". WIRED. Retrieved 2016-02-01.

- Silver, David; Huang, Aja; Maddison, Chris J.; Guez, Arthur; Sifre, Laurent; Driessche, George van den; Schrittwieser, Julian; Antonoglou, Ioannis; Panneershelvam, Veda; Lanctot, Marc; Dieleman, Sander; Grewe, Dominik; Nham, John; Kalchbrenner, Nal; Sutskever, Ilya; Lillicrap, Timothy; Leach, Madeleine; Kavukcuoglu, Koray; Graepel, Thore; Hassabis, Demis (28 January 2016). "Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search". Nature. 529 (7587): 484–489. Bibcode:2016Natur.529..484S. doi:10.1038/nature16961. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 26819042. S2CID 515925.

- Elizabeth Gibney (27 January 2016), "Go players react to computer defeat", Nature, doi:10.1038/nature.2016.19255, S2CID 146868978

- "Google AI to play live Go match against world champion". BBC News. 5 February 2016.

- ^ "AlphaGo races ahead 2--0 against Lee Sedol". 10 March 2016. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- "AlphaGo - DeepMind".

- "Google AI wins second Go game against top player". BBC News. 10 March 2016.

- "AlphaGo shows its true strength in 3rd victory against Lee Sedol". 12 March 2016. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ^ "Lee Sedol defeats AlphaGo in masterful comeback - Game 4". 13 March 2016. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- "The Sadness and Beauty of Watching Google's AI Play Go". WIRED. 11 March 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- "Künstliche Intelligenz: "Alpha Go spielt wie eine Göttin" - Golem.de".

External links

- Further information on Lee Sedol's playing style as it relates to his games above, at Sensei's Library.