Various cells and batteries (top left to bottom right): two AA, one D, one handheld ham radio battery, two 9-volt (PP3), two AAA, one C, one camcorder battery, one cordless phone battery Various cells and batteries (top left to bottom right): two AA, one D, one handheld ham radio battery, two 9-volt (PP3), two AAA, one C, one camcorder battery, one cordless phone battery | |

| Type | Power supply |

|---|---|

| Working principle | Chemical reactions Electromotive force |

| Inventor | Alessandro Volta |

| Invention year | 1800; 225 years ago (1800) |

| Electronic symbol | |

The symbol for a battery in a circuit diagram. It originated as a schematic drawing of the earliest type of battery, the voltaic pile. | |

An electric battery is a source of electric power consisting of one or more electrochemical cells with external connections for powering electrical devices. When a battery is supplying power, its positive terminal is the cathode and its negative terminal is the anode. The terminal marked negative is the source of electrons. When a battery is connected to an external electric load, those negatively charged electrons flow through the circuit and reach to the positive terminal, thus cause a redox reaction by attracting positively charged ions, cations. Thus converts high-energy reactants to lower-energy products, and the free-energy difference is delivered to the external circuit as electrical energy. Historically the term "battery" specifically referred to a device composed of multiple cells; however, the usage has evolved to include devices composed of a single cell.

Primary (single-use or "disposable") batteries are used once and discarded, as the electrode materials are irreversibly changed during discharge; a common example is the alkaline battery used for flashlights and a multitude of portable electronic devices. Secondary (rechargeable) batteries can be discharged and recharged multiple times using an applied electric current; the original composition of the electrodes can be restored by reverse current. Examples include the lead–acid batteries used in vehicles and lithium-ion batteries used for portable electronics such as laptops and mobile phones.

Batteries come in many shapes and sizes, from miniature cells used to power hearing aids and wristwatches to, at the largest extreme, huge battery banks the size of rooms that provide standby or emergency power for telephone exchanges and computer data centers. Batteries have much lower specific energy (energy per unit mass) than common fuels such as gasoline. In automobiles, this is somewhat offset by the higher efficiency of electric motors in converting electrical energy to mechanical work, compared to combustion engines.

History

| This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . (February 2022) |

Invention

A voltaic pile, the first battery

A voltaic pile, the first battery Italian physicist Alessandro Volta demonstrating his pile to French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte

Italian physicist Alessandro Volta demonstrating his pile to French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte

Benjamin Franklin first used the term "battery" in 1749 when he was doing experiments with electricity using a set of linked Leyden jar capacitors. Franklin grouped a number of the jars into what he described as a "battery", using the military term for weapons functioning together. By multiplying the number of holding vessels, a stronger charge could be stored, and more power would be available on discharge.

Italian physicist Alessandro Volta built and described the first electrochemical battery, the voltaic pile, in 1800. This was a stack of copper and zinc plates, separated by brine-soaked paper disks, that could produce a steady current for a considerable length of time. Volta did not understand that the voltage was due to chemical reactions. He thought that his cells were an inexhaustible source of energy, and that the associated corrosion effects at the electrodes were a mere nuisance, rather than an unavoidable consequence of their operation, as Michael Faraday showed in 1834.

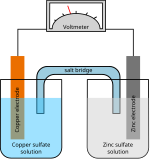

Although early batteries were of great value for experimental purposes, in practice their voltages fluctuated and they could not provide a large current for a sustained period. The Daniell cell, invented in 1836 by British chemist John Frederic Daniell, was the first practical source of electricity, becoming an industry standard and seeing widespread adoption as a power source for electrical telegraph networks. It consisted of a copper pot filled with a copper sulfate solution, in which was immersed an unglazed earthenware container filled with sulfuric acid and a zinc electrode.

These wet cells used liquid electrolytes, which were prone to leakage and spillage if not handled correctly. Many used glass jars to hold their components, which made them fragile and potentially dangerous. These characteristics made wet cells unsuitable for portable appliances. Near the end of the nineteenth century, the invention of dry cell batteries, which replaced the liquid electrolyte with a paste, made portable electrical devices practical.

Batteries in vacuum tube devices historically used a wet cell for the "A" battery (to provide power to the filament) and a dry cell for the "B" battery (to provide the plate voltage).

Ongoing developments

Between 2010 and 2018, annual battery demand grew by 30%, reaching a total of 180 GWh in 2018. Conservatively, the growth rate is expected to be maintained at an estimated 25%, culminating in demand reaching 2600 GWh in 2030. In addition, cost reductions are expected to further increase the demand to as much as 3562 GWh.

Important reasons for this high rate of growth of the electric battery industry include the electrification of transport, and large-scale deployment in electricity grids, supported by decarbonization initiatives.

Distributed electric batteries, such as those used in battery electric vehicles (vehicle-to-grid), and in home energy storage, with smart metering and that are connected to smart grids for demand response, are active participants in smart power supply grids. New methods of reuse, such as echelon use of partly-used batteries, add to the overall utility of electric batteries, reduce energy storage costs, and also reduce pollution/emission impacts due to longer lives. In echelon use of batteries, vehicle electric batteries that have their battery capacity reduced to less than 80%, usually after service of 5–8 years, are repurposed for use as backup supply or for renewable energy storage systems.

Grid scale energy storage envisages the large-scale use of batteries to collect and store energy from the grid or a power plant and then discharge that energy at a later time to provide electricity or other grid services when needed. Grid scale energy storage (either turnkey or distributed) are important components of smart power supply grids.

Chemistry and principles

Main articles: Electrochemical cell and Voltaic cell

Batteries convert chemical energy directly to electrical energy. In many cases, the electrical energy released is the difference in the cohesive or bond energies of the metals, oxides, or molecules undergoing the electrochemical reaction. For instance, energy can be stored in Zn or Li, which are high-energy metals because they are not stabilized by d-electron bonding, unlike transition metals. Batteries are designed so that the energetically favorable redox reaction can occur only when electrons move through the external part of the circuit.

A battery consists of some number of voltaic cells. Each cell consists of two half-cells connected in series by a conductive electrolyte containing metal cations. One half-cell includes electrolyte and the negative electrode, the electrode to which anions (negatively charged ions) migrate; the other half-cell includes electrolyte and the positive electrode, to which cations (positively charged ions) migrate. Cations are reduced (electrons are added) at the cathode, while metal atoms are oxidized (electrons are removed) at the anode. Some cells use different electrolytes for each half-cell; then a separator is used to prevent mixing of the electrolytes while allowing ions to flow between half-cells to complete the electrical circuit.

Each half-cell has an electromotive force (emf, measured in volts) relative to a standard. The net emf of the cell is the difference between the emfs of its half-cells. Thus, if the electrodes have emfs and , then the net emf is ; in other words, the net emf is the difference between the reduction potentials of the half-reactions.

The electrical driving force or across the terminals of a cell is known as the terminal voltage (difference) and is measured in volts. The terminal voltage of a cell that is neither charging nor discharging is called the open-circuit voltage and equals the emf of the cell. Because of internal resistance, the terminal voltage of a cell that is discharging is smaller in magnitude than the open-circuit voltage and the terminal voltage of a cell that is charging exceeds the open-circuit voltage. An ideal cell has negligible internal resistance, so it would maintain a constant terminal voltage of until exhausted, then dropping to zero. If such a cell maintained 1.5 volts and produced a charge of one coulomb then on complete discharge it would have performed 1.5 joules of work. In actual cells, the internal resistance increases under discharge and the open-circuit voltage also decreases under discharge. If the voltage and resistance are plotted against time, the resulting graphs typically are a curve; the shape of the curve varies according to the chemistry and internal arrangement employed.

The voltage developed across a cell's terminals depends on the energy release of the chemical reactions of its electrodes and electrolyte. Alkaline and zinc–carbon cells have different chemistries, but approximately the same emf of 1.5 volts; likewise NiCd and NiMH cells have different chemistries, but approximately the same emf of 1.2 volts. The high electrochemical potential changes in the reactions of lithium compounds give lithium cells emfs of 3 volts or more.

Almost any liquid or moist object that has enough ions to be electrically conductive can serve as the electrolyte for a cell. As a novelty or science demonstration, it is possible to insert two electrodes made of different metals into a lemon, potato, etc. and generate small amounts of electricity.

A voltaic pile can be made from two coins (such as a nickel and a penny) and a piece of paper towel dipped in salt water. Such a pile generates a very low voltage but, when many are stacked in series, they can replace normal batteries for a short time.

Types

See also: Battery nomenclature and List of battery typesPrimary and secondary batteries

Batteries are classified into primary and secondary forms:

- Primary batteries are designed to be used until exhausted of energy then discarded. Their chemical reactions are generally not reversible, so they cannot be recharged. When the supply of reactants in the battery is exhausted, the battery stops producing current and is useless.

- Secondary batteries can be recharged; that is, they can have their chemical reactions reversed by applying electric current to the cell. This regenerates the original chemical reactants, so they can be used, recharged, and used again multiple times.

Some types of primary batteries used, for example, for telegraph circuits, were restored to operation by replacing the electrodes. Secondary batteries are not indefinitely rechargeable due to dissipation of the active materials, loss of electrolyte and internal corrosion.

Primary batteries, or primary cells, can produce current immediately on assembly. These are most commonly used in portable devices that have low current drain, are used only intermittently, or are used well away from an alternative power source, such as in alarm and communication circuits where other electric power is only intermittently available. Disposable primary cells cannot be reliably recharged, since the chemical reactions are not easily reversible and active materials may not return to their original forms. Battery manufacturers recommend against attempting to recharge primary cells. In general, these have higher energy densities than rechargeable batteries, but disposable batteries do not fare well under high-drain applications with loads under 75 ohms (75 Ω). Common types of disposable batteries include zinc–carbon batteries and alkaline batteries.

Secondary batteries, also known as secondary cells, or rechargeable batteries, must be charged before first use; they are usually assembled with active materials in the discharged state. Rechargeable batteries are (re)charged by applying electric current, which reverses the chemical reactions that occur during discharge/use. Devices to supply the appropriate current are called chargers. The oldest form of rechargeable battery is the lead–acid battery, which are widely used in automotive and boating applications. This technology contains liquid electrolyte in an unsealed container, requiring that the battery be kept upright and the area be well ventilated to ensure safe dispersal of the hydrogen gas it produces during overcharging. The lead–acid battery is relatively heavy for the amount of electrical energy it can supply. Its low manufacturing cost and its high surge current levels make it common where its capacity (over approximately 10 Ah) is more important than weight and handling issues. A common application is the modern car battery, which can, in general, deliver a peak current of 450 amperes.

Composition

Many types of electrochemical cells have been produced, with varying chemical processes and designs, including galvanic cells, electrolytic cells, fuel cells, flow cells and voltaic piles.

A wet cell battery has a liquid electrolyte. Other names are flooded cell, since the liquid covers all internal parts or vented cell, since gases produced during operation can escape to the air. Wet cells were a precursor to dry cells and are commonly used as a learning tool for electrochemistry. They can be built with common laboratory supplies, such as beakers, for demonstrations of how electrochemical cells work. A particular type of wet cell known as a concentration cell is important in understanding corrosion. Wet cells may be primary cells (non-rechargeable) or secondary cells (rechargeable). Originally, all practical primary batteries such as the Daniell cell were built as open-top glass jar wet cells. Other primary wet cells are the Leclanche cell, Grove cell, Bunsen cell, Chromic acid cell, Clark cell, and Weston cell. The Leclanche cell chemistry was adapted to the first dry cells. Wet cells are still used in automobile batteries and in industry for standby power for switchgear, telecommunication or large uninterruptible power supplies, but in many places batteries with gel cells have been used instead. These applications commonly use lead–acid or nickel–cadmium cells. Molten salt batteries are primary or secondary batteries that use a molten salt as electrolyte. They operate at high temperatures and must be well insulated to retain heat.

A dry cell uses a paste electrolyte, with only enough moisture to allow current to flow. Unlike a wet cell, a dry cell can operate in any orientation without spilling, as it contains no free liquid, making it suitable for portable equipment. By comparison, the first wet cells were typically fragile glass containers with lead rods hanging from the open top and needed careful handling to avoid spillage. Lead–acid batteries did not achieve the safety and portability of the dry cell until the development of the gel battery. A common dry cell is the zinc–carbon battery, sometimes called the dry Leclanché cell, with a nominal voltage of 1.5 volts, the same as the alkaline battery (since both use the same zinc–manganese dioxide combination). A standard dry cell comprises a zinc anode, usually in the form of a cylindrical pot, with a carbon cathode in the form of a central rod. The electrolyte is ammonium chloride in the form of a paste next to the zinc anode. The remaining space between the electrolyte and carbon cathode is taken up by a second paste consisting of ammonium chloride and manganese dioxide, the latter acting as a depolariser. In some designs, the ammonium chloride is replaced by zinc chloride.

A reserve battery can be stored unassembled (unactivated and supplying no power) for a long period (perhaps years). When the battery is needed, then it is assembled (e.g., by adding electrolyte); once assembled, the battery is charged and ready to work. For example, a battery for an electronic artillery fuze might be activated by the impact of firing a gun. The acceleration breaks a capsule of electrolyte that activates the battery and powers the fuze's circuits. Reserve batteries are usually designed for a short service life (seconds or minutes) after long storage (years). A water-activated battery for oceanographic instruments or military applications becomes activated on immersion in water.

On 28 February 2017, the University of Texas at Austin issued a press release about a new type of solid-state battery, developed by a team led by lithium-ion battery inventor John Goodenough, "that could lead to safer, faster-charging, longer-lasting rechargeable batteries for handheld mobile devices, electric cars and stationary energy storage". The solid-state battery is also said to have "three times the energy density", increasing its useful life in electric vehicles, for example. It should also be more ecologically sound since the technology uses less expensive, earth-friendly materials such as sodium extracted from seawater. They also have much longer life.

Sony has developed a biological battery that generates electricity from sugar in a way that is similar to the processes observed in living organisms. The battery generates electricity through the use of enzymes that break down carbohydrates.

The sealed valve regulated lead–acid battery (VRLA battery) is popular in the automotive industry as a replacement for the lead–acid wet cell. The VRLA battery uses an immobilized sulfuric acid electrolyte, reducing the chance of leakage and extending shelf life. VRLA batteries immobilize the electrolyte. The two types are:

- Gel batteries (or "gel cell") use a semi-solid electrolyte.

- Absorbed Glass Mat (AGM) batteries absorb the electrolyte in a special fiberglass matting.

Other portable rechargeable batteries include several sealed "dry cell" types, that are useful in applications such as mobile phones and laptop computers. Cells of this type (in order of increasing power density and cost) include nickel–cadmium (NiCd), nickel–zinc (NiZn), nickel–metal hydride (NiMH), and lithium-ion (Li-ion) cells. Li-ion has by far the highest share of the dry cell rechargeable market. NiMH has replaced NiCd in most applications due to its higher capacity, but NiCd remains in use in power tools, two-way radios, and medical equipment.

In the 2000s, developments include batteries with embedded electronics such as USBCELL, which allows charging an AA battery through a USB connector, nanoball batteries that allow for a discharge rate about 100x greater than current batteries, and smart battery packs with state-of-charge monitors and battery protection circuits that prevent damage on over-discharge. Low self-discharge (LSD) allows secondary cells to be charged prior to shipping.

Lithium–sulfur batteries were used on the longest and highest solar-powered flight.

Consumer and industrial grades

Batteries of all types are manufactured in consumer and industrial grades. Costlier industrial-grade batteries may use chemistries that provide higher power-to-size ratio, have lower self-discharge and hence longer life when not in use, more resistance to leakage and, for example, ability to handle the high temperature and humidity associated with medical autoclave sterilization.

Combination and management

| This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . (February 2022) |

Standard-format batteries are inserted into battery holder in the device that uses them. When a device does not uses standard-format batteries, they are typically combined into a custom battery pack which holds multiple batteries in addition to features such as a battery management system and battery isolator which ensure that the batteries within are charged and discharged evenly.

Sizes

Main article: List of battery sizesPrimary batteries readily available to consumers range from tiny button cells used for electric watches, to the No. 6 cell used for signal circuits or other long duration applications. Secondary cells are made in very large sizes; very large batteries can power a submarine or stabilize an electrical grid and help level out peak loads.

As of 2017, the world's largest battery was built in South Australia by Tesla. It can store 129 MWh. A battery in Hebei Province, China, which can store 36 MWh of electricity was built in 2013 at a cost of $500 million. Another large battery, composed of Ni–Cd cells, was in Fairbanks, Alaska. It covered 2,000 square metres (22,000 sq ft)—bigger than a football pitch—and weighed 1,300 tonnes. It was manufactured by ABB to provide backup power in the event of a blackout. The battery can provide 40 MW of power for up to seven minutes. Sodium–sulfur batteries have been used to store wind power. A 4.4 MWh battery system that can deliver 11 MW for 25 minutes stabilizes the output of the Auwahi wind farm in Hawaii.

Comparison

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Electric battery" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (June 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Many important cell properties, such as voltage, energy density, flammability, available cell constructions, operating temperature range and shelf life, are dictated by battery chemistry.

| Chemistry | Anode (−) | Cathode (+) | Max. voltage, theoretical (V) | Nominal voltage, practical (V) | Specific energy (kJ/kg) | Elaboration | Shelf life at 25 °C, 80% capacity (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc–carbon | Zn | C | 1.6 | 1.2 | 130 | Inexpensive. | 18 |

| Zinc–chloride | Zn | C | 1.5 | Also known as "heavy-duty", inexpensive. | |||

| Alkaline (zinc–manganese dioxide) | Zn | MnO2 | 1.5 | 1.15 | 400–590 | Moderate energy density. Good for high- and low-drain uses. | 30 |

| Nickel oxyhydroxide (zinc–manganese dioxide/nickel oxyhydroxide) | 1.7 | Moderate energy density. Good for high drain uses. | |||||

| Lithium (lithium–copper oxide) Li–CuO | Li | CuO | 1.7 | No longer manufactured. Replaced by silver oxide (IEC-type "SR") batteries. | |||

| Lithium (lithium–iron disulfide) LiFeS2 | Li | FeS2 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1070 | Expensive. Used in 'plus' or 'extra' batteries. | 337 |

| Lithium (lithium–manganese dioxide) LiMnO2 | Li | MnO2 | 3.0 | 830–1010 | Expensive. Used only in high-drain devices or for long shelf-life due to very low rate of self-discharge. 'Lithium' alone usually refers to this type of chemistry. | ||

| Lithium (lithium–carbon fluoride) Li–(CF)n | Li | (CF)n | 3.6 | 3.0 | 120 | ||

| Lithium (lithium–chromium oxide) Li–CrO2 | Li | CrO2 | 3.8 | 3.0 | 108 | ||

| Lithium (lithium-silicon) | Li22Si5 | ||||||

| Mercury oxide | Zn | HgO | 1.34 | 1.2 | High-drain and constant voltage. Banned in most countries because of health concerns. | 36 | |

| Zinc–air | Zn | O2 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 1590 | Used mostly in hearing aids. | |

| Zamboni pile | Zn | Ag or Au | 0.8 | Very long life. Very low (nanoamp, nA) current | >2,000 | ||

| Silver oxide (silver–zinc) | Zn | Ag2O | 1.85 | 1.5 | 470 | Very expensive. Used only commercially in 'button' cells. | 30 |

| Magnesium | Mg | MnO2 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 40 |

| Chemistry | Cell voltage | Specific energy (kJ/kg) | Energy density (kJ/liter) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NiCd | 1.2 | 140 | Inexpensive. High-/low-drain, moderate energy density. Can withstand very high discharge rates with virtually no loss of capacity. Moderate rate of self-discharge. Environmental hazard due to Cadmium, use now virtually prohibited in Europe. | |

| Lead–acid | 2.1 | 140 | Moderately expensive. Moderate energy density. Moderate rate of self-discharge. Higher discharge rates result in considerable loss of capacity. Environmental hazard due to Lead. Common use: automobile batteries | |

| NiMH | 1.2 | 360 | Inexpensive. Performs better than alkaline batteries in higher drain devices. Traditional chemistry has high energy density, but also a high rate of self-discharge. Newer chemistry has low self-discharge rate, but also a ~25% lower energy density. Used in some cars. | |

| NiZn | 1.6 | 360 | Moderately inexpensive. High drain device suitable. Low self-discharge rate. Voltage closer to alkaline primary cells than other secondary cells. No toxic components. Newly introduced to the market (2009). Has not yet established a track record. Limited size availability. | |

| AgZn | 1.86 1.5 | 460 | Smaller volume than equivalent Li-ion. Extremely expensive due to silver. Very high energy density. Very high drain capable. For many years considered obsolete due to high silver prices. Cell suffers from oxidation if unused. Reactions are not fully understood. Terminal voltage very stable but suddenly drops to 1.5 volts at 70–80% charge (believed to be due to presence of both argentous and argentic oxide in positive plate; one is consumed first). Has been used in lieu of primary battery (moon buggy). Is being developed once again as a replacement for Li-ion. | |

| LiFePO4 | 3.3 3.0 | 360 | 790 | Lithium–Iron–Phosphate chemistry. |

| Lithium ion | 3.6 | 460 | Very expensive. Very high energy density. Not usually available in "common" battery sizes. Lithium polymer battery is common in laptop computers, digital cameras, camcorders, and cellphones. Very low rate of self-discharge. Terminal voltage varies from 4.2 to 3.0 volts during discharge. Volatile: Chance of explosion if short-circuited, allowed to overheat, or not manufactured with rigorous quality standards. |

Performance, capacity and discharge

A battery's characteristics may vary over load cycle, over charge cycle, and over lifetime due to many factors including internal chemistry, current drain, and temperature. At low temperatures, a battery cannot deliver as much power. As such, in cold climates, some car owners install battery warmers, which are small electric heating pads that keep the car battery warm.

A battery's capacity is the amount of electric charge it can deliver at a voltage that does not drop below the specified terminal voltage. The more electrode material contained in the cell the greater its capacity. A small cell has less capacity than a larger cell with the same chemistry, although they develop the same open-circuit voltage. Capacity is usually stated in ampere-hours (A·h) (mAh for small batteries). The rated capacity of a battery is usually expressed as the product of 20 hours multiplied by the current that a new battery can consistently supply for 20 hours at 20 °C (68 °F), while remaining above a specified terminal voltage per cell. For example, a battery rated at 100 A·h can deliver 5 A over a 20-hour period at room temperature. The fraction of the stored charge that a battery can deliver depends on multiple factors, including battery chemistry, the rate at which the charge is delivered (current), the required terminal voltage, the storage period, ambient temperature and other factors.

The higher the discharge rate, the lower the capacity. The relationship between current, discharge time and capacity for a lead acid battery is approximated (over a typical range of current values) by Peukert's law:

where

- is the capacity when discharged at a rate of 1 amp.

- is the current drawn from battery (A).

- is the amount of time (in hours) that a battery can sustain.

- is a constant around 1.3.

Charged batteries (rechargeable or disposable) lose charge by internal self-discharge over time although not discharged, due to the presence of generally irreversible side reactions that consume charge carriers without producing current. The rate of self-discharge depends upon battery chemistry and construction, typically from months to years for significant loss. When batteries are recharged, additional side reactions reduce capacity for subsequent discharges. After enough recharges, in essence all capacity is lost and the battery stops producing power. Internal energy losses and limitations on the rate that ions pass through the electrolyte cause battery efficiency to vary. Above a minimum threshold, discharging at a low rate delivers more of the battery's capacity than at a higher rate. Installing batteries with varying A·h ratings changes operating time, but not device operation unless load limits are exceeded. High-drain loads such as digital cameras can reduce total capacity of rechargeable or disposable batteries. For example, a battery rated at 2 A·h for a 10- or 20-hour discharge would not sustain a current of 1 A for a full two hours as its stated capacity suggests.

The C-rate is a measure of the rate at which a battery is being charged or discharged. It is defined as the current through the battery divided by the theoretical current draw under which the battery would deliver its nominal rated capacity in one hour. It has the units h. Because of internal resistance loss and the chemical processes inside the cells, a battery rarely delivers nameplate rated capacity in only one hour. Typically, maximum capacity is found at a low C-rate, and charging or discharging at a higher C-rate reduces the usable life and capacity of a battery. Manufacturers often publish datasheets with graphs showing capacity versus C-rate curves. C-rate is also used as a rating on batteries to indicate the maximum current that a battery can safely deliver in a circuit. Standards for rechargeable batteries generally rate the capacity and charge cycles over a 4-hour (0.25C), 8 hour (0.125C) or longer discharge time. Types intended for special purposes, such as in a computer uninterruptible power supply, may be rated by manufacturers for discharge periods much less than one hour (1C) but may suffer from limited cycle life.

In 2009 experimental lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO

4) battery technology provided the fastest charging and energy delivery, discharging all its energy into a load in 10 to 20 seconds. In 2024 a prototype battery for electric cars that could charge from 10% to 80% in five minutes was demonstrated, and a Chinese company claimed that car batteries it had introduced charged 10% to 80% in 10.5 minutes—the fastest batteries available—compared to Tesla's 15 minutes to half-charge.

Lifespan and endurance

Battery life (or lifetime) has two meanings for rechargeable batteries but only one for non-chargeables. It can be used to describe the length of time a device can run on a fully charged battery—this is also unambiguously termed "endurance". For a rechargeable battery it may also be used for the number of charge/discharge cycles possible before the cells fail to operate satisfactorily—this is also termed "lifespan". The term shelf life is used to describe how long a battery will retain its performance between manufacture and use. Available capacity of all batteries drops with decreasing temperature. In contrast to most of today's batteries, the Zamboni pile, invented in 1812, offers a very long service life without refurbishment or recharge, although it can supply very little current (nanoamps). The Oxford Electric Bell has been ringing almost continuously since 1840 on its original pair of batteries, thought to be Zamboni piles.

Disposable batteries typically lose 8–20% of their original charge per year when stored at room temperature (20–30 °C). This is known as the "self-discharge" rate, and is due to non-current-producing "side" chemical reactions that occur within the cell even when no load is applied. The rate of side reactions is reduced for batteries stored at lower temperatures, although some can be damaged by freezing and storing in a fridge will not meaningfully prolong shelf life and risks damaging condensation. Old rechargeable batteries self-discharge more rapidly than disposable alkaline batteries, especially nickel-based batteries; a freshly charged nickel cadmium (NiCd) battery loses 10% of its charge in the first 24 hours, and thereafter discharges at a rate of about 10% a month. However, newer low self-discharge nickel–metal hydride (NiMH) batteries and modern lithium designs display a lower self-discharge rate (but still higher than for primary batteries).

The active material on the battery plates changes chemical composition on each charge and discharge cycle; active material may be lost due to physical changes of volume, further limiting the number of times the battery can be recharged. Most nickel-based batteries are partially discharged when purchased, and must be charged before first use. Newer NiMH batteries are ready to be used when purchased, and have only 15% discharge in a year.

Some deterioration occurs on each charge–discharge cycle. Degradation usually occurs because electrolyte migrates away from the electrodes or because active material detaches from the electrodes. Low-capacity NiMH batteries (1,700–2,000 mA·h) can be charged some 1,000 times, whereas high-capacity NiMH batteries (above 2,500 mA·h) last about 500 cycles. NiCd batteries tend to be rated for 1,000 cycles before their internal resistance permanently increases beyond usable values. Fast charging increases component changes, shortening battery lifespan. If a charger cannot detect when the battery is fully charged then overcharging is likely, damaging it.

NiCd cells, if used in a particular repetitive manner, may show a decrease in capacity called "memory effect". The effect can be avoided with simple practices. NiMH cells, although similar in chemistry, suffer less from memory effect.

Automotive lead–acid rechargeable batteries must endure stress due to vibration, shock, and temperature range. Because of these stresses and sulfation of their lead plates, few automotive batteries last beyond six years of regular use. Automotive starting (SLI: Starting, Lighting, Ignition) batteries have many thin plates to maximize current. In general, the thicker the plates the longer the life. They are typically discharged only slightly before recharge. "Deep-cycle" lead–acid batteries such as those used in electric golf carts have much thicker plates to extend longevity. The main benefit of the lead–acid battery is its low cost; its main drawbacks are large size and weight for a given capacity and voltage. Lead–acid batteries should never be discharged to below 20% of their capacity, because internal resistance will cause heat and damage when they are recharged. Deep-cycle lead–acid systems often use a low-charge warning light or a low-charge power cut-off switch to prevent the type of damage that will shorten the battery's life.

Battery life can be extended by storing the batteries at a low temperature, as in a refrigerator or freezer, which slows the side reactions. Such storage can extend the life of alkaline batteries by about 5%; rechargeable batteries can hold their charge much longer, depending upon type. To reach their maximum voltage, batteries must be returned to room temperature; discharging an alkaline battery at 250 mA at 0 °C is only half as efficient as at 20 °C. Alkaline battery manufacturers such as Duracell do not recommend refrigerating batteries.

Hazards

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

A battery explosion is generally caused by misuse or malfunction, such as attempting to recharge a primary (non-rechargeable) battery, or a short circuit.

When a battery is recharged at an excessive rate, an explosive gas mixture of hydrogen and oxygen may be produced faster than it can escape from within the battery (e.g. through a built-in vent), leading to pressure build-up and eventual bursting of the battery case. In extreme cases, battery chemicals may spray violently from the casing and cause injury. An expert summary of the problem indicates that this type uses "liquid electrolytes to transport lithium ions between the anode and the cathode. If a battery cell is charged too quickly, it can cause a short circuit, leading to explosions and fires". Car batteries are most likely to explode when a short circuit generates very large currents. Such batteries produce hydrogen, which is very explosive, when they are overcharged (because of electrolysis of the water in the electrolyte). During normal use, the amount of overcharging is usually very small and generates little hydrogen, which dissipates quickly. However, when "jump starting" a car, the high current can cause the rapid release of large volumes of hydrogen, which can be ignited explosively by a nearby spark, e.g. when disconnecting a jumper cable.

Overcharging (attempting to charge a battery beyond its electrical capacity) can also lead to a battery explosion, in addition to leakage or irreversible damage. It may also cause damage to the charger or device in which the overcharged battery is later used.

Disposing of a battery via incineration may cause an explosion as steam builds up within the sealed case.

Many battery chemicals are corrosive, poisonous or both. If leakage occurs, either spontaneously or through accident, the chemicals released may be dangerous. For example, disposable batteries often use a zinc "can" both as a reactant and as the container to hold the other reagents. If this kind of battery is over-discharged, the reagents can emerge through the cardboard and plastic that form the remainder of the container. The active chemical leakage can then damage or disable the equipment that the batteries power. For this reason, many electronic device manufacturers recommend removing the batteries from devices that will not be used for extended periods of time.

Many types of batteries employ toxic materials such as lead, mercury, and cadmium as an electrode or electrolyte. When each battery reaches end of life it must be disposed of to prevent environmental damage. Batteries are one form of electronic waste (e-waste). E-waste recycling services recover toxic substances, which can then be used for new batteries. Of the nearly three billion batteries purchased annually in the United States, about 179,000 tons end up in landfills across the country.

Further information: Lithium battery § Health issues on ingestion, and Button cell § Accidental ingestionBatteries may be harmful or fatal if swallowed. Small button cells can be swallowed, in particular by young children. While in the digestive tract, the battery's electrical discharge may lead to tissue damage; such damage is occasionally serious and can lead to death. Ingested disk batteries do not usually cause problems unless they become lodged in the gastrointestinal tract. The most common place for disk batteries to become lodged is the esophagus, resulting in clinical sequelae. Batteries that successfully traverse the esophagus are unlikely to lodge elsewhere. The likelihood that a disk battery will lodge in the esophagus is a function of the patient's age and battery size. Older children do not have problems with batteries smaller than 21–23 mm. Liquefaction necrosis may occur because sodium hydroxide is generated by the current produced by the battery (usually at the anode). Perforation has occurred as rapidly as 6 hours after ingestion.

Some battery manufactures have added a bad taste to batteries to discourage swallowing.

Legislation and regulation

| This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . (February 2022) |

Legislation around electric batteries includes such topics as safe disposal and recycling.

In the United States, the Mercury-Containing and Rechargeable Battery Management Act of 1996 banned the sale of mercury-containing batteries, enacted uniform labeling requirements for rechargeable batteries and required that rechargeable batteries be easily removable. California and New York City prohibit the disposal of rechargeable batteries in solid waste. The rechargeable battery industry operates nationwide recycling programs in the United States and Canada, with dropoff points at local retailers.

The Battery Directive of the European Union has similar requirements, in addition to requiring increased recycling of batteries and promoting research on improved battery recycling methods. In accordance with this directive all batteries to be sold within the EU must be marked with the "collection symbol" (a crossed-out wheeled bin). This must cover at least 3% of the surface of prismatic batteries and 1.5% of the surface of cylindrical batteries. All packaging must be marked likewise.

In response to reported accidents and failures, occasionally ignition or explosion, recalls of devices using lithium-ion batteries have become more common in recent years.

On 9 December 2022, the European Parliament reached an agreement to force, from 2026, manufacturers to design all electrical appliances sold in the EU (and not used predominantly in wet conditions) so that consumers can easily remove and replace batteries themselves.

See also

References

- Crompton, T. R. (20 March 2000). Battery Reference Book (third ed.). Newnes. p. Glossary 3. ISBN 978-0-08-049995-6. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- Pauling, Linus (1988). "15: Oxidation-Reduction Reactions; Electrolysis". General Chemistry. New York: Dover Publications, Inc. p. 539. ISBN 978-0-486-65622-9.

- Pistoia, Gianfranco (25 January 2005). Batteries for Portable Devices. Elsevier. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-08-045556-3. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- "The history and development of batteries". 30 April 2015.

- ""Electrical battery" of Leyden jars - The Benjamin Franklin Tercentenary". www.benfranklin300.org.

- Bellis, Mary. Biography of Alessandro Volta, Inventor of the Battery. About.com. Retrieved 7 August 2008

- Stinner, Arthur. Alessandro Volta and Luigi Galvani Archived 10 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine (PDF). Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- Fascinating facts about the invention of the Electric Battery by Alessandro Volta in 1800. The Great Idea Finder. Retrieved 11 August 2008

- for instance, in the discovery of electromagnetism in 1820

- Battery History, Technology, Applications and Development. MPower Solutions Ltd. Retrieved 19 March 2007.

- Borvon, Gérard (10 September 2012). "History of the electrical units". Association S-EAU-S.

- "Columbia Dry Cell Battery". National Historic Chemical Landmarks. American Chemical Society. Archived from the original on 23 February 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ^ Brudermüller, Martin; Sobotka, Benedikt; Dominic, Waughray (September 2019). Insight Report — A Vision for a Sustainable Battery Value Chain in 2030 : Unlocking the Full Potential to Power Sustainable Development and Climate Change Mitigation (PDF) (Report). World Economic Forum & Global Battery Alliance. pp. 11, 29. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- Siano, Pierluigi (2014). "Demand response and smart grids-A survey". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 30. Elsevier: 461–478. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2013.10.022. ISSN 1364-0321.

- Pan, AQ; Li, XZ; Shang, J; Feng, JH; Tao, YB; Ye, JL; Yang, X; Li, C; Liao, QQ (2019). The applications of echelon use batteries from electric vehicles to distributed energy storage systems. 2019 International Conference on New Energy and Future Energy System (IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science). Vol. 354. IOP Publishing Ltd. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/354/1/012012. 012012.

- Leisch, Jennifer E.; Chernyakhovskiy, Ilya (September 2019). Grid-Scale Battery Storage : Frequently Asked Questions (PDF) (Report). National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) & greeningthegrid.org. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- Ashcroft, N.W.; Mermin (1976). Solid State Physics. N.D. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

- Dingrando 665.

- Saslow 338.

- Dingrando 666.

- ^ Knight 943.

- ^ Knight 976.

- Terminal Voltage. Tiscali Reference. Originally from Hutchinson Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 7 April 2007

- Dingrando 674.

- Dingrando 677.

- "The Lemon Battery". ushistory.org. Archived from the original on 9 May 2007. Retrieved 10 April 2007.

- ZOOM activities: phenom Potato Battery. Accessed 10 April 2007.

- Howstuffworks "Battery Experiments: Voltaic Pile". Accessed 10 April 2007.

- Dingrando 675.

- Fink, Ch. 11, Sec. "Batteries and Fuel Cells."

- Franklin Leonard Pope, Modern Practice of the Electric Telegraph 15th Edition, D. Van Nostrand Company, New York, 1899, pp. 7–11. Available on the Internet Archive

- ^ Duracell: Battery Care. Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- ^ Alkaline Manganese Dioxide Handbook and Application Manual (PDF). Energizer. Retrieved 25 August 2008.

- "Spotlight on Photovoltaics & Fuel Cells: A Web-based Study & Comparison" (PDF). pp. 1–2. Retrieved 14 March 2007.

- "Lithium-Ion Battery Inventor Introduces New Technology for Fast-Charging, Noncombustible Batteries". University of Texas at Austin. University of Texas. 28 February 2017. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- Hislop, Martin (1 March 2017). "Solid-state EV battery breakthrough from Li-ion battery inventor John Goodenough". North American Energy News. The American Energy News. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

But even John Goodenough's work doesn't change my forecast that EVs will take at least 50 years to reach 70 to 80 percent of the global vehicle market.

- Sony Develops A Bio Battery Powered By Sugar Archived 11 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 24 August 2007.

- Dynasty VRLA Batteries and Their Application Archived 6 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine. C&D Technologies, Inc. Retrieved 26 August 2008.

- Amos, J. (24 August 2008) "Solar plane makes record flight" BBC News

- Adams, Louis (November 2015). "Powering Tomorrow's Medicine: Critical Decisions for Batteries in Medical Applications". Medical Design Briefs.

- "Elon Musk wins $50m bet with giant battery for South Australia". Sky News. 24 November 2017. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- Dillow, Clay (21 December 2012). "China Builds the World's Largest Battery, a Building-Sized, 36-Megawatt-Hour Behemoth | Popular Science". Popsci.com. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- Conway, E. (2 September 2008) "World's biggest battery switched on in Alaska" Telegraph.co.uk

- Biello, D. (22 December 2008) "Storing the Breeze: New Battery Might Make Wind Power More Reliable" Scientific American

- "Auwahi Wind | Energy Solutions | Sempra U.S. Gas & Power, LLC". Semprausgp.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- "How a battery works". Curious. 25 February 2016. Archived from the original on 26 March 2022.

- "Lithium Iron Disulfide Handbook and Application Manual" (PDF). energizer.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 March 2006. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- Excludes the mass of the air oxidizer.

- ^ Battery Knowledge – AA Portable Power Corp. Retrieved 16 April 2007. Archived 23 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Battery Capacity". techlib.com.

- A Guide to Understanding Battery Specifications, MIT Electric Vehicle Team, December 2008

- Kang, B.; Ceder, G. (2009). "Battery materials for ultrafast charging and discharging". Nature. 458 (7235): 190–193. Bibcode:2009Natur.458..190K. doi:10.1038/nature07853. PMID 19279634. S2CID 20592628. 1:00–6:50 (audio) Archived 22 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Cambridge spin-out's sportscar prototype takes ultra-fast charging out of the lab and onto the road". University of Cambridge. 1 July 2024.

- da Silva, João (14 August 2024). "Zeekr: China EV firm claims world's fastest-charging battery". BBC News.

- "Battery cycling and endurance testing". University of Sheffield Centre for Research into Electrical Energy Storage and Applications. 5 October 2020.

- "Battery Lifespan". NREL - Transportation & Mobility Research. 30 March 2023.

- Self discharge of batteries. Corrosion Doctors. Retrieved 9 September 2007

- Tugend, Alina (10 November 2007). "In Battery Buying, Enough Decisions to Exhaust That Bunny". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- Energizer Rechargeable Batteries and Chargers: Frequently Asked Questions Archived 9 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Energizer. Retrieved 3 February 2009.

- "eneloop, environmentally friendly and energy saving batteries | Panasonic eneloop". www.panasonic-eneloop.eu. Archived from the original on 2 February 2010.

- ^ Rechargeable battery Tips. NIMH Technology Information. Retrieved 10 August 2007

- Battery Myths vs Battery Facts. Retrieved 10 August 2007

- Filip M. Gieszczykiewicz. "Sci.Electronics FAQ: More Battery Info". repairfaq.org.

- RechargheableBatteryInfo.com, ed. (28 October 2005), What does 'memory effect' mean?, archived from the original on 15 July 2007, retrieved 10 August 2007

- Rich, Vincent (1994). The International Lead Trade. Cambridge: Woodhead. 129.

- Deep Cycle Battery FAQ Archived 22 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Northern Arizona Wind & Sun. Retrieved 3 February 2009.

- Car and Deep Cycle Battery FAQ Archived 6 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Rainbow Power Company. Retrieved 3 February 2009.

- Deep cycle battery guide Archived 17 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Energy Matters. Retrieved 3 February 2009.

- Ask Yahoo: Does putting batteries in the freezer make them last longer? Archived 27 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 7 March 2007.

- Hislop, Martin (1 March 2017). "Solid-state EV battery breakthrough from Li-ion battery inventor John Goodenough". North American Energy News. The American Energy News. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- "battery hazards". YouTube. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- Batteries. EPA. Retrieved 11 September 2007

- Battery Recycling » Earth 911 Archived 12 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 9 September 2007.

- "San Francisco Supervisor Takes Aim at Toxic Battery Waste". Environmental News Network (11 July 2001).

- "Product Safety DataSheet. Energizer (p. 2). Retrieved 9 September 2007" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2007.

- "Swallowed a Button Battery? | Battery in the Nose or Ear?". Poison.org. 3 March 2010. Archived from the original on 16 August 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- Dire, Daniel J. (9 June 2016), Vearrier, David (ed.), "Disk Battery Ingestion: Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology", Medscape

- Bitter tasting battey discourages ingestion., 25 October 2021

- "Mercury-Containing and Rechargeable Battery Management Act" (PDF). EPA. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- "Battery Recycling in New York... it's the law!". call2recycle.org. 31 October 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- Bill No. 1125 - Rechargeable Battery Recycling Act of 2006, State of California (PDF), 2006, retrieved 2 June 2021

- "Rechargeable Battery Recycling Corporation". www.rbrc.org. Archived from the original on 12 August 2008. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- Disposal of spent batteries and accumulators. European Union. Retrieved 27 July 2009.

- "Guidelines on Portable Batteries Marking Requirements in the European Union 2008" (PDF). EPBA-EU. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2011.

- Schweber, Bill (4 August 2015). "Lithium Batteries: The Pros and Cons". GlobalSpec. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- Fowler, Suzanne (21 September 2016). "Samsung's Recall – The Problem with Lithium Ion Batteries". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- "Batteries: deal on new EU rules for design, production and waste treatment". News European Parliament (Press release). European Parliament. 9 December 2022. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- "Neue EU-Regeln: Jeder soll Handy-Akkus selbst tauschen können" [New EU rules: Everyone should be able to replace smartphone batteries themselves]. Wirtschaft. Der Spiegel (in German). 9 December 2022. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

Bibliography

- Dingrando, Laurel; et al. (2007). Chemistry: Matter and Change. New York: Glencoe/McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-877237-5. Ch. 21 (pp. 662–695) is on electrochemistry.

- Fink, Donald G.; H. Wayne Beaty (1978). Standard Handbook for Electrical Engineers, Eleventh Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-020974-9.

- Knight, Randall D. (2004). Physics for Scientists and Engineers: A Strategic Approach. San Francisco: Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-8053-8960-9. Chs. 28–31 (pp. 879–995) contain information on electric potential.

- Linden, David; Thomas B. Reddy (2001). Handbook of Batteries. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-135978-8.

- Saslow, Wayne M. (2002). Electricity, Magnetism, and Light. Toronto: Thomson Learning. ISBN 978-0-12-619455-5. Chs. 8–9 (pp. 336–418) have more information on batteries.

- Turner, James Morton. Charged: A History of Batteries and Lessons for a Clean Energy Future (University of Washington Press, 2022). online review

External links

Media related to Electric batteries at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Electric batteries at Wikimedia Commons- Non-rechargeable batteries (archived 22 October 2013)

- HowStuffWorks: How batteries work

- Other Battery Cell Types

- DoITPoMS Teaching and Learning Package- "Batteries"

| Battery sizes | |

|---|---|

| Single-cell | |

| Multiple-cell | |

and

and  , then the net emf is

, then the net emf is  ; in other words, the net emf is the difference between the

; in other words, the net emf is the difference between the  across the

across the  until exhausted, then dropping to zero. If such a cell maintained 1.5 volts and produced a charge of one

until exhausted, then dropping to zero. If such a cell maintained 1.5 volts and produced a charge of one

is the capacity when discharged at a rate of 1 amp.

is the capacity when discharged at a rate of 1 amp. is the current drawn from battery (

is the current drawn from battery ( is the amount of time (in hours) that a battery can sustain.

is the amount of time (in hours) that a battery can sustain. is a constant around 1.3.

is a constant around 1.3.