| Chicken turtle Temporal range: 5–0 Ma PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N ↓ Pliocene–recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chicken turtle on land | |

| Conservation status | |

Secure (NatureServe) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Testudinoidea |

| Family: | Emydidae |

| Subfamily: | Deirochelyinae |

| Genus: | Deirochelys |

| Species: | D. reticularia |

| Binomial name | |

| Deirochelys reticularia (Latreille, 1801) | |

| Subspecies | |

|

D. r. chrysea Schwartz, 1956 | |

| Synonyms | |

Species synonymy

| |

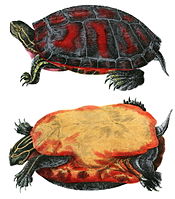

The chicken turtle (Deirochelys reticularia) is a turtle native to the southeastern United States. It is the only extant member of the genus Deirochelys and is a member of the freshwater marsh turtle family Emydidae. The chicken turtle's scientific name refers to its extremely long neck and distinctive net-like pattern on its upper shell. There are three regionally distinct subspecies (eastern, western and Florida), which are thought to have evolved when populations became separated during periods of glaciation. These subspecies can be distinguished by their appearance; the western chicken turtle displays dark markings along the seams of its plastron (lower shell), while the plastron of the Florida subspecies is a bright yellow or orange color. Fossil records show that the chicken turtle has been present in the region for up to five million years.

Chicken turtles inhabit shallow, still or slow-moving bodies of water with plenty of vegetation and a muddy substrate. They are not found in rivers or deeper lakes that may be home to predators such as alligators and large fish. The chicken turtle is predominantly carnivorous and feeds mostly on invertebrates such as crayfish, dragonflies and spiders, but is also known to eat tadpoles, carrion and occasionally plant material. It is an active hunter and its long neck allows it to catch fast-moving prey. Although feeding and mating take place in aquatic environments, the chicken turtle is very well adapted to living on land and may spend more than half the year out of the water. Like many reptiles, it spends much of the day basking in the sun to regulate its body temperature, but unlike most other aquatic turtles, it hibernates over the winter months except in the warmer, southernmost reaches of its range.

The chicken turtle is relatively small compared to other related turtles, with males measuring up to around 16.5 cm (6.5 in) and females around 26.0 cm (10.2 in). It is also one of the world's shortest-lived turtles, reaching a maximum age of 20–24 years. There are thought to be around 100,000 adult chicken turtles in the wild. Although the population as a whole is considered secure, its status in some areas is less certain and several states have listed it as threatened or introduced regulations to manage hunting or taking. The word "chicken" in the turtle's vernacular name is apparently a reference to the taste of its meat, which was once popular in turtle soup and commonly sold in southern markets.

Taxonomy and evolution

The species was first described in 1801 independently by two French zoologists: as Testudo reticularia by Pierre André Latreille, and as Testudo reticulata by François Marie Daudin. Both descriptions were based on drawings and a single specimen collected by Louis Augustin Guillaume Bosc in the vicinity of Charleston, South Carolina some years previously. Subsequent studies placed the chicken turtle into various related genera (Emys, Clemmys and Terrapene) before Louis Agassiz assigned it to the current genus in 1857. He distinguished D. reticularia from other North American members of the family Emydidae by the length of its neck, and from the Australian Chelodina by the articulation of the neck vertebrae. In his 1940 comparison of Latreille and Daudin's original descriptions, naturalist Francis Harper determined that Latreille's had been published first, hence the currently accepted specific name.

The chicken turtle is the only extant species in the genus Deirochelys. Its parent family is Emydidae, the freshwater marsh turtles, which are found on every continent except Australia and Antarctica. The name of the genus is derived from the Ancient Greek words for "neck" (deirḗ) and "tortoise" (khélūs), a reference to the species' particularly long neck. The species name reticularia comes from the Latin for "net-like" or "reticulated" (reticulatus), probably alluding to the turtle's patterned carapace (top shell).

Subspecies

There are three distinct subspecies of chicken turtle, as described by Albert Schwartz in 1956 from a study of 325 specimens:

- The eastern chicken turtle (D. r. reticularia) is the turtle originally described by Latreille in 1801. It is the largest of the chicken turtles, with males measuring up to 16.5 cm (6.5 in) and females up to 26.0 cm (10.2 in). It is distinguished from the other subspecies by the coloring of its carapace, which is olive to brown with a yellow rim. The plastron (lower shell) sometimes features a spot or indistinct splotch of color. Its outstretched neck is especially long, sometimes as long as the carapace itself.

- The Florida chicken turtle (D. r. chrysea) has the most distinctively patterned carapace of all the chicken turtles, featuring bold, broad yellow-orange reticulation. The shell is cuneiform (wedge-shaped), especially so in males and juvenile turtles, and measures up to 16.5 cm (6.5 in) for males and 25.0 cm (9.8 in) for females. The subspecies name chrysea is taken from the Latin for "golden one" due to the bright yellow or orange color of its plastron.

- The western chicken turtle (D. r. miaria) is the smallest of the three subspecies; males have a maximum carapace length of 16.1 cm (6.3 in) and females 21.0 cm (8.3 in). The stripes on its head and neck are lighter in color (cream or pale yellow) compared to other chicken turtles, and its plastron features a dark pattern along the seams. The subspecies epithet miaria derives from the Greek for "stained", referring to this patterning. Its carapace is oval in shape and flatter than that of the other subspecies.

Schwartz considered that D. r. reticularia is probably most reminiscent of the ancestors of Deirochelys, and that the other two subspecies most likely developed from it. The western chicken turtle is the most divergent of the three subspecies, suggesting a longer period of separation, possibly after populations were cut off from one another during a period of glaciation. Similarly, D. r. chrysea developed from a later population separation, a common phenomenon on the geographically diverse Florida peninsula. Studies of the chicken turtle's mitochondrial DNA support this theory of earlier divergence of the western subspecies from the two eastern ones. It is thought that the Mississippi River prevents intergradation (the presence of populations sharing characteristics of two subspecies) between D. r. miaria and D. r. reticularia since the chicken turtle does not generally inhabit rivers or moving water. Intergrades of the eastern and Florida chicken turtles are known, however, with several specimens having been collected in north-central Florida.

Fossil record

Ancestors of the chicken turtle and related turtles of the genus Chrysemys may have been present in North America for up to 40 million years. Writing in 1978, Dale Jackson considered D. reticularia to have "one of the most complete evolutionary records of any Recent turtle". Fossils have been found throughout its current range; examples dating from the Pliocene (roughly 5.33 to 2.58 million years ago) to the sub-Recent (prior to the start of the Holocene, or Recent, epoch around 11,700 years ago) have been discovered in Florida, in addition to fossils in Pleistocene deposits in South Carolina. A fossil found in Alachua County, Florida dating from the middle Pliocene was originally thought to belong to D. reticularia, but was later identified by Jackson as an extinct relative, D. carri. This species was somewhat larger than its modern relative and its shell roughly twice as thick. Other fossil fragments from the Hemingfordian (20.6 to 16.3 million years ago) are considered to belong to even earlier, more primitive members of the genus.

Description

The chicken turtle resembles the painted turtle (Chrysemys picta) and some species of cooter (genus Pseudemys) in appearance, but has an unusually long neck that is close to the length of its shell. It often also has black blotches on the underside of the bridge (the part of the shell connecting the carapace and plastron), which are not present in these other species. The carapace of the chicken turtle is elongated and pear-shaped, with the rear half noticeably wider than the front. It ranges from dark green to brown in color, and features a distinctive yellowish net-like pattern across its entire upper surface. The scutes of the upper shell have a ridged or wrinkled texture and are rough to the touch. Beneath its shell, the chicken turtle has particularly slender ribs, supposedly developed to accommodate its long, muscular neck. Although the chicken turtle shares morphological features with Blanding's turtle (Emydoidea blandingii), such as these elongated ribs and the shape of the skull, DNA analysis has shown they are not closely related.

Descriptions of the chicken turtle disagree on the base color of its skin but it is generally reported to be darker than the carapace, varying from olive to brown to black. One of the distinguishing features of D. reticularia is a broad yellow stripe on the forelegs. The skin of the neck and head also has light stripes, although narrower, while the tail and rear legs show vertical yellow markings. The head itself is elongated with a somewhat pointed snout but no other distinguishing features, and the digits of the feet are webbed and tipped with claws.

Compared to other turtles, the chicken turtle is small to medium in size. Adults vary in length from around 10–25 cm (4–10 in), with an average length of around 13 cm (5 in). The width of the carapace is roughly 65 percent of its length. Mature chicken turtles exhibit some degree of sexual dimorphism; the females are larger and heavier than males, although the males have longer, thicker tails. Unlike the painted turtle, there is no difference between the sexes in terms of the length of the foreclaws.

Chicken turtle hatchlings measure approximately 28–32 mm (1.1–1.3 in) and weigh around 8–9 g (0.28–0.32 oz). The shell is much rounder than the adults', and the shell and skin are considerably brighter in color, with a greater number of light stripes. The young of the western chicken turtle hatches with the distinctive dark markings on its plastron already present.

Distribution

Range

The chicken turtle is found throughout the southeastern United States; its range extends from the Atlantic coastal plain and states such as North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia and Florida westward through the Gulf plain towards the Mississippi River. It tends to remain in coastal areas and is largely absent from the Piedmont plateau and more mountainous regions in the north of these states. West of the river, its territory reaches as far north as Missouri and as far west as Oklahoma and central Texas. Across its range, the chicken turtle may inhabit many hundreds or possibly thousands of wetland sites, although populations in any particular location are generally small.

Eastern chicken turtle

The eastern chicken turtle is the most widespread of the three subspecies, with specimens known from eight states. The main bulk of its territory begins on the eastern banks of the Mississippi River in southeast Louisiana and extends eastward along the coastal plain of the Gulf of Mexico. Apart from the coastal region in the south of the state, it is not present in most of Mississippi, save for a small population in the drainage basin of the Tombigbee River. In Alabama, it is again commonly found throughout the coastal plain in the southern half of the state. It is also present further north in the Ridge and Valley region of the Appalachian mountain range, although less common.

Through Georgia, South Carolina and North Carolina, the eastern chicken turtle is again widely found throughout the coastal regions, although specimens have been recorded further inland in North Carolina. It is abundant in northern Florida, especially in the Panhandle region, where it is the only subspecies present. Its range begins to overlap with the Florida chicken turtle towards the north-central part of the state, with intergrades having been identified in Taylor, Levy, Gilchrist and Clay counties.

The eastern chicken turtle is also present in Virginia, although it is very rare there. A small colony was known to inhabit First Landing State Park in Virginia, but several studies have only managed to locate one adult female and it is thought this population may be extirpated. Around 40 mi (64 km) to the west, a small group of around 30 adults is present in Isle of Wight County. Neither of these locations is contiguous with the rest of the turtle's range; it is unclear whether these populations are relics of a native and formerly more widespread group, or whether they were introduced to the area.

Florida chicken turtle

As its name suggests, the Florida chicken turtle is native to Florida and is only found within the state. It is relatively widespread throughout the central and southern portions of the state, although it is absent from the Florida Keys.

Western chicken turtle

The western chicken turtle's range is generally restricted to locations west of the Mississippi River, although specimens have been found on the river's eastern banks in northwest Mississippi state. Its range extends from the coastal plain of the Gulf of Mexico in Texas and Louisiana, northward into the south and east of Oklahoma and through Arkansas towards Missouri. It may once have been common in the swampland of Missouri's Bootheel region, but is now only found in a few small groups in the extreme southeast of the state. Its territory is also decreasing in Arkansas; diffuse groups are now found only in the northern reaches of the Gulf coastal plain in the south of the state, as well as some regions of the Arkansas River Valley. The western chicken turtle is reasonably uncommon in Texas but its population there is secure. It inhabits the drainage basins of several rivers in the eastern half of the state, such as the Sabine and the Neches.

Habitat

Chicken turtles are semiaquatic, equally comfortable in wetland habitats and on land. All three subspecies have similar preferences; they like quiet, still or slow-moving bodies of water such as shallow ponds, oxbow lakes, drainage ditches, borrow pits, marshes, swales, cypress swamps, and Carolina bays. Generally, the chicken turtle prefers water with a maximum depth of around 70 cm (2.3 ft), but it is known to inhabit ponds up to 2 m (6.6 ft) deep. It rarely inhabits moving water such as streams or rivers, but may sometimes colonize quieter rivulets or pools in the riparian zone. Furthermore, it strongly favors fresh water, avoiding brackish water wherever possible.

The chicken turtle thrives in bodies of water with dense aquatic vegetation and a soft, muddy substrate. Often these are ephemeral or temporary wetlands that readily dry out during the summer or in periods of drought. Such habitats tend to be free both of fish, which would provide competition for food, and potential predators such as alligators. When drying occurs, chicken turtles will migrate to the land and burrow into the soil or hide under foliage to avoid dry weather. Although they are well adapted to living terrestrially, they rarely abandon their original habitat even during extended dry spells, and will relocate to the water once it returns.

Although the chicken turtle does not generally inhabit islands, isolated groups are also known in the Outer Banks chain of barrier islands off North Carolina. These maritime forest habitats are prone to drying out easily in the summer and can be affected by storms and sea spray, but research into one of these groups found no meaningful differences in longevity, growth rate or sex ratio between members of this population and their mainland counterparts.

Behavior

The chicken turtle is diurnal; its main periods of activity, such as feeding and mating, take place in the morning and late afternoon, either side of the warmest hours of the day. Like all reptiles, chicken turtles are cold-blooded and must regulate their body temperature. The main way they do this is through basking; they will spend many hours in the sun and can often be seen sitting on logs or tree stumps with their neck outstretched. However, they tend to spend less time basking than their herbivorous relatives. In order to be active, chicken turtles require an internal body temperature of around 25.5 °C (77.9 °F), therefore they are generally more active on warm, cloudy days than on hot, sunny ones. Like other turtles, the chicken turtle is extremely wary while basking and can be startled easily. Some have been known to bite and scratch in response to threats while others are more timid and retiring. Males may display particularly hostile behavior towards each other.

Unusually for an aquatic turtle, the chicken turtle is known to hibernate in winter throughout the northern part of its range. It leaves the water in late September to find a suitable site for the winter, usually either in mud and vegetation around the edges of the ponds and swamps which it inhabits. Alternatively, it may bury itself under fallen leaves in surrounding woodlands or in the mud at the bottom of a pond. Hibernating chicken turtles remain out of the water for up to six months before becoming active again in the spring. They are able to spend long periods on land without feeding due to their large stores of body fat. The first few days of activity following hibernation are generally dedicated to nesting and egg-laying by females, with males emerging slightly later around early April. In the southernmost part of its range where winters are milder, the chicken turtle remains active all year round apart from on especially cool days.

Chicken turtles are also frequently encountered on land during the summer months when the temporary wetlands they inhabit dry out. Males especially wander onto the land during this period and may travel great distances in search of alternative water, whereas gravid females remain in the wetland as long as possible since extra water is needed for egg production. Turtles unable to find a suitable aquatic habitat during particularly dry years may migrate to higher ground and burrow into the earth to undergo aestivation, a period of dormancy similar to hibernation. Survivorship rates among small juveniles are lower during this period, possibly because they lack the fat and water reserves required to withstand long periods without feeding. Individuals are known to return to the same terrestrial refugia from one year to the next. In total, a chicken turtle may spend up to 285 days per year on the land.

Life cycle

Mating and nesting

The mating season of the chicken turtle can be estimated by the times of year in which male testicular volume is greatest, indicating maximum sperm production. This period varies by location; in Florida, the testes are largest during the hottest months of summer, while in South Carolina and the slightly cooler climate of Missouri this occurs in the late spring and early summer months, roughly May through July. In Texas, courtship may take place in the early spring (February to April) or fall (September to November). The chicken turtle's mating ritual is initiated by the male, who swims at an angle towards the female turtle until he is facing her head-on. He then attracts the female's attention by making short, rapid swimming motions, gazing at her and vibrating his outstretched foreclaws against her face and neck. Only if the female is receptive does copulation occur. There is no evidence of forced insemination as sometimes seen in other related turtles. Chicken turtle mating takes place in shallow waters, and reproduction can be disrupted by prolonged periods of dry weather.

Like mating, the timing of the nesting season depends on latitude. For example, in Florida nesting takes place continuously between mid-September and early March, with the possibility of an interruption if the winter weather is particularly cold. Further north, nesting may begin earlier in the year (around the end of August) but is always paused during the coldest months before resuming in the spring. In South Carolina and Arkansas, nesting and egg-laying may recommence in February, while in Virginia, in the northernmost reaches of the chicken turtle's range, it may not start again until March. This pattern of nesting in winter and hatching in spring is highly unusual; the chicken turtle is one of the only native North American turtles to nest at this time of year. Several reasons have been suggested for why this behavior developed. One hypothesis is that it allows the hatchlings to emerge in the spring when there is a good supply of food available and less competition from hatchlings of other turtle species that appear later in the year. Furthermore, predators of turtle eggs may be less likely to hunt for them in the spring when there are generally fewer to be found. Atypically among North American turtles, the female chicken turtle can retain fertilized, calcified eggs in her oviducts for several months after copulation, especially over the winter; these eggs will be laid in the spring once the nesting season resumes.

The female nests on land, often in loose soil, but sometimes in heavier ground. She digs out a cylindrical cavity with a depth of around 10 cm (4 in) and a diameter at the opening of approximately 8 cm (3 in). Nests are usually built close to the water, although females are known to wander up to 280 m (306 yd) in search of suitable sites. Once the nest is ready, the female deposits a clutch of between one and nineteen eggs. The eggs are white with a leathery or parchment-like shell, and elliptical in shape, measuring approximately 28–41 mm (1.10–1.61 in) by 17–25 mm (0.67–0.98 in). Egg mass varies considerably; a review of eight studies found reported averages between 9.0 g (0.3 oz) and 11.0 g (0.4 oz). The mass appears to be positively correlated with female body size and eggs laid in fall are significantly heavier than those laid in spring. Several minutes after laying, the female will fill in her nest, sweeping the dirt over the eggs with her hind legs until they are covered. Chicken turtles commonly lay two clutches of eggs per year, although in the uninterrupted nesting season of Florida, females have been known to produce as many as four.

Growth and lifespan

The incubation period of chicken turtle eggs is again dependent on location and temperature. In the warmer climate of Florida, incubation takes 78–89 days in the wild, while in South Carolina it may last up to 152 days. Under laboratory conditions, which aimed to recreate the very cool soil temperatures (as low as 4 °C (39 °F)) experienced further north, incubation was extended up to 194 days. The egg's yolk contains a very high proportion of fats, on average 32.5% of dry matter, which help to nourish the hatchling during this long period in the nest. Inside the egg, the embryo goes through a period of little to no development (diapause) in the late gastrula stage. It must experience a period of cool temperatures, around 15–22 °C (59–72 °F), before development proceeds when the temperature increases to 24 °C (75 °F). The temperature during this time strongly influences the sex of the hatchling; in one study, 100% of eggs kept at 25 °C (77 °F) produced male turtles, whereas at 30 °C (86 °F), 89% were female.

When it is ready to emerge from the egg, the hatchling breaks through the shell using its egg tooth, a sharp, thornlike projection on its beak. Chicken turtles born in the fall commonly remain in the nest over winter before emerging in the spring, meaning that hatchlings from eggs laid in February or March may not leave the nest for over a year. Very young hatchlings are almost circular, although as they grow their shell becomes less rounded and more elongated. Young chicken turtles grow rapidly, approximately 25–44 mm (0.98–1.73 in) in the first year depending on conditions; in drought years growth may be slower. The rate of growth is highly variable between regions and populations. Growth continues until the turtle reaches sexual maturity, which occurs after approximately 2–3 years (or at a plastron length of 75–80 mm (2.95–3.15 in)) for males, and around 6–8 years (plastron length 141–155 mm (5.55–6.10 in)) for females. The turtle continues to grow after reaching maturity, although considerably more slowly. Females that reach a length of around 180 mm (7.09 in) appear to become much less reproductively active; they may only lay eggs every second or third nesting season, or they may cease to ovulate altogether.

The chicken turtle is one of the shortest-lived turtles in the world. Wild chicken turtles have been recaptured up to 15 years after their first capture, with some reaching an estimated maximum age of 20–24 years. A study by herpetologist Whit Gibbons suggested that less than 1% of chicken turtles live past the age of 15. In captivity, they may only live for as little as 13 years. This short lifespan means that the average female chicken turtle is active for fewer than ten breeding seasons. Determining the age of a turtle becomes increasingly difficult as the animal ages; in the first few years of its life the turtle's shell may show visible growth rings (annuli) that can be used to approximate its age. Annuli in the turtle's claws can sometimes be seen up to the age of around 14.

Ecology

Diet

Like many emydids, chicken turtles are almost completely carnivorous during the first year of their lives. However, they are unusual in preferring a carnivorous diet into adulthood. It has been suggested that this explains the smaller local populations of D. reticularia compared to other related turtles due to competition with fish for food, especially insects. In the wild they are known to prey on crayfish, invertebrates, tadpoles, vegetation and carrion, including dead fish and other animals. Carr described having seen a chicken turtle eating Nuphar (bonnet-lily) buds, while captive adults have been observed feeding on gopher frog tadpoles, lettuce, and canned fish.

In a 1997 study of chicken turtle fecal matter collected during the summer months in South Carolina, dragonfly nymphs were the most commonly observed food, along with snails, spiders and insects such as backswimmers and water bugs. Only six out of forty-three specimens had ingested plant material. Investigations into the digestive tract contents of chicken turtles in north-central Florida, where the eastern and Florida subspecies coexist, found similar results. Decapods (including crayfish and shrimp), dragonflies and beetles were the most frequently encountered foods; six out of twenty-five turtles had consumed trace amounts of plants or algae. Research in Oklahoma found evidence that adults of the western subspecies follow a more omnivorous diet than their relatives. While crayfish and bugs were still present in the majority of fecal samples, 92.6 percent of samples also contained material or seeds of various plants, including the common rush and broadleaf cattail.

The chicken turtle is an aquatic hunter. It waits in the water and strikes its long neck out quickly with its mouth open to catch live food, relying on sight to detect its prey. The length of the neck allows it to capture fast-moving prey such as fish and spiders, which would otherwise be able to escape. Like Blanding's turtle, the chicken turtle uses a sucking motion when feeding; any water taken in during the process is expelled before the food is swallowed whole. The Florida chicken turtle is known to feed passively, swimming along with its long neck extended and foraging in clumps of vegetation.

Predators

Information regarding predation of the chicken turtle is scarce, but it is presumed that common predators such as raccoons, skunks and snakes feed on eggs and juvenile turtles. Fire ants are also known to attack nests and kill hatchlings of D. reticularia and other turtles. Hibbitts and Hibbitts suggest humans and alligators to be the main predators of the western subspecies, while a study in Florida found evidence of red-shouldered hawks preying on various turtles including the Florida chicken turtle. Otters, herons and snapping turtles are also listed as possible predators.

The meat of the chicken turtle is considered palatable and was once widely sold at markets throughout the southern United States for use in turtle soup; it is thought that the vernacular name is a reference to the flavor of its meat. It is still sometimes eaten today in rural areas, although this is uncommon. Consumption by humans is no longer considered to be a significant threat to the chicken turtle population.

Parasites

Various parasites have been identified during examinations of chicken turtle specimens. In 1968, Fain described a new species of cheyletoid mite, Caminacarus deirochelys, found in the rectum of a chicken turtle collected in Englewood, Florida, thirty years earlier. The trematode Neopolystoma orbiculare has been reported from the bladder of D. reticularia, while Telorchis corti is known to parasitize chicken turtles and various other emydids. A 2016 study of two chicken turtle specimens captured in Alabama identified a previously unknown species of blood fluke, Spirorchis collinsi.

Conservation

The chicken turtle population as a whole is currently considered secure and is thought to consist of at least 100,000 adults. Local populations are often small but stable, however the species is designated by NatureServe as S1 (critically imperiled) in Virginia and Missouri and S2 (imperiled) in Arkansas, Louisiana, North Carolina and Oklahoma. The chicken turtle does not appear on the IUCN's Red List of Threatened Species, although the Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group's own provisional list considers it Near Threatened. At the state level, the chicken turtle is protected by various local laws. In Virginia, where only around 30 adults are thought to remain, it has been listed as "vulnerable" since 1987. It is also considered at risk by the Alabama Natural Heritage Program; local regulations state that only two turtles may be kept and these must be for personal use (e.g. as pets). Along with other native reptiles, removal of chicken turtles from their natural habitat is regulated in several states throughout its range including Texas, Georgia and North Carolina. The chicken turtle is subject to a ban on commercial taking in Arkansas, where it is "extremely rare". In Missouri, where until 1995 no sightings had been recorded for at least 33 years, it is listed as an endangered species, making hunting illegal.

Habitat loss appears to be the most significant threat to the stability of chicken turtle populations. Human activity is one cause of this; the turtle's preferred wetland habitats are often converted for agriculture, such as rice farming, or building developments. In Missouri and Arkansas in particular, the destruction of swampland and bottomland hardwood forests is a direct threat to the chicken turtle. Man-made obstacles such as fences and road barriers can also lead to populations becoming isolated. Since it prefers to live in small, shallow bodies of water that can easily dry out during the hotter months, the chicken turtle is also susceptible to the loss of upland habitats surrounding wetlands to which it migrates during periods of drought. Migration also leads to turtles, especially females in search of suitable nesting sites, walking onto roads where they are killed by traffic. Fire is a further threat; wildfires are becoming increasingly common and while controlled burns can help to protect wetland habitats by decreasing the risk of wildfire, chicken turtles that are overwintering on land or have been forced onto the land during drier months can be caught up in them.

Several locations inhabited by chicken turtles are already under protection, having been designated as wildlife reserves or conservation areas. However, further preservation of wetlands, especially temporary ones, would be beneficial in ensuring the continued stability of the population. In particular, the protections currently in place rarely include the surrounding areas of land that the chicken turtle inhabits for much of the year. Scientists in Oklahoma have developed quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay tests to enable the presence of four uncommon or vulnerable reptiles, including the chicken turtle, to be identified through environmental DNA.

References

Notes

- The number of eggs per clutch is given by different sources as 5–12, 5–15, 1–12 in South Carolina and 2–19 in Florida. The size of the clutch appears to increase with the turtle's plastron length.

- The Amphibians and Reptiles of Arkansas states that the previous sighting occurred in 1957. Buhlmann, Gibbons and Jackson give a later date of 1962.

Citations

- ^ Lovich & Gibbons 2021, p. 82.

- ^ "Deirochelys reticularia". explorer.natureserve.org. NatureServe. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ Ernst & Barbour 1972, p. 174.

- Buhlmann, Gibbons & Jackson 2008, p. 014.1.

- ^ Fritz, Uwe; Havaš, Peter (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World" (PDF). Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 179–180. doi:10.3897/vz.57.e30895. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- Jackson 1978, p. 38.

- ^ Sonnini, C. S.; Latreille, P. A. (1801). Histoire naturelle des reptiles, avec figures dessinées d'apres nature. Vol. 1. Paris: Imprimerie Crapelet. pp. 124–127.

- Daudin, F. M. (1801). Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière, des reptiles. Vol. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie de F. Dufart. pp. 144–147.

- Schwartz 1956, p. 461.

- ^ Buhlmann, Gibbons & Jackson 2008, p. 014.2.

- Agassiz 1857, p. 252.

- Agassiz 1857, p. 441.

- Harper, Francis (1940). "Some Works of Bartram, Daudin, Latreille, and Sonnini, and Their Bearing Upon North American Herpetological Nomenclature". Am. Midl. Nat. 23 (3). The University of Notre Dame: 710–711. doi:10.2307/2420453. JSTOR 2420453.

- Jackson 1978, p. 37.

- Franklin, Carl J. (2007). Turtles. St Paul, Minnesota: Voyageur Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-78582-775-7.

- "Taxonomy chapter for Turtle, eastern chicken (030064)". BOVA booklet. Virginia Fish and Wildlife Information Service. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- Schwartz 1956, p. 462.

- ^ Rhodin et al. 2021, p. 135.

- ^ Schwartz 1956, p. 468.

- ^ Guyer, Bailey & Mount 2015, p. 161.

- ^ Zug & Schwartz 1971, p. 107.2.

- ^ Rhodin et al. 2021, p. 136.

- Ernst & Barbour 1972, p. 330.

- Buhlmann, Tuberville & Gibbons 2008, p. 85.

- Ernst & Barbour 1972, p. 175.

- Ernst & Barbour 1972, p. 293.

- Schwartz 1956, p. 488.

- ^ Schwartz 1956, p. 498.

- ^ Ernst & Lovich 2009, p. 224.

- Guyer, Bailey & Mount 2015, p. 160.

- Jackson 1978, p. 47.

- ^ Ernst & Lovich 2009, p. 223.

- ^ Carr 1952, p. 316.

- Jackson 1978, p. 43.

- Jackson 1978, p. 45.

- ^ "Life History chapter for Turtle, eastern chicken (030064)". BOVA booklet. Virginia Fish and Wildlife Information Service. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ^ Lovich & Gibbons 2021, p. 83.

- ^ Buhlmann, Gibbons & Jackson 2008, p. 014.3.

- ^ Hibbitts & Hibbitts 2016, p. 160.

- ^ Schwartz 1956, p. 464.

- Stephens, Patrick R.; Wiens, John J. (2003). "Ecological diversification and phylogeny of emydid turtles". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 79 (4): 577–610. doi:10.1046/j.1095-8312.2003.00211.x.

- ^ Carr 1952, p. 318.

- ^ Ernst & Lovich 2009, p. 222.

- ^ Ernst & Barbour 1972, p. 177.

- ^ Ernst & Barbour 1972, p. 178.

- ^ Connell, Patia M. "Species Profile: Chicken Turtle (Deirochelys reticularia)". srelherp.uga.edu. Savannah River Ecology Laboratory, University of Georgia. Retrieved 2022-04-28.

- Zug & Schwartz 1971, p. 107.1.

- ^ "Status chapter for Turtle, eastern chicken (030064)". BOVA booklet. Virginia Fish and Wildlife Information Service. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ "Western Chicken Turtle". mdc.mo.gov. Missouri Department of Conservation. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ^ Trauth, Robison & Plummer 2004, p. 221.

- Gibbons 1969, p. 670.

- Dinkelacker, S. A. (2014). "Demographic and Reproductive Traits of Western Chicken Turtles, Deirochelys reticularia miaria in central Arkansas". Journal of Herpetology. 48 (4): 439–444. doi:10.1670/12-227.

- ^ Guyer, Bailey & Mount 2015, p. 162.

- Gibbons 1969, p. 676.

- Hanscom, Ryan J.; Dinkelacker, Stephen A.; McCall, Aaron J.; Parlin, Adam F. (2020). "Demographic traits of freshwater turtles in a maritime forest habitat". Herpetologica. 76 (1): 12–21. doi:10.1655/Herpetologica-D-19-00037. S2CID 212114331.

- ^ Ernst & Lovich 2009, p. 226.

- ^ Ernst & Barbour 1972, p. 176.

- ^ Buhlmann, Gibbons & Jackson 2008, p. 014.4.

- Gibbons 1969, p. 675.

- ^ Buhlmann, Kurt A.; Congdon, Justin D.; Gibbons, J. Whitfield; Greene, Judith L. (2009). "Ecology of chicken turtles (Deirochelys reticularia) in a seasonal wetland ecosystem: exploiting resource and refuge environment". Herpetologica. 65 (1): 39–53. doi:10.1655/08-028R1.1. JSTOR 27669742. S2CID 85392895.

- Ernst & Lovich 2009, p. 225.

- Gibbons 1969, p. 674.

- ^ Hibbitts & Hibbitts 2016, p. 162.

- Berry, James F.; Shine, Richard (1980). "Sexual Size Dimorphism and Sexual Selection in Turtles (Order Testudines)". Oecologia. 44 (2): 185–191. Bibcode:1980Oecol..44..185B. doi:10.1007/BF00572678. JSTOR 4216009. PMID 28310555. S2CID 2456783.

- ^ Ernst & Lovich 2009, p. 227.

- Buhlmann, Kurt A.; Lynch, Tracy K.; Gibbons, J. Whitfield; Greene, Judith L. (1995). "Prolonged egg retention in the turtle Deirochelys reticularia in South Carolina". Herpetologica. 51 (4): 457–462. JSTOR 3892771.

- ^ Carr 1952, p. 319.

- ^ Ernst & Lovich 2009, p. 229.

- Dinkelacker, Stephen A.; Hilzinger, Nathanael L. (2014). "Demographic and reproductive traits of Western Chicken Turtles, Deirochelys reticularia miaria, in Central Arkansas". Journal of Herpetology. 48 (4): 439–444. doi:10.1670/12-227. JSTOR 43287470. S2CID 86489790.

- ^ Congdon, Justin D.; Gibbons, J. Whitfield; Greene, Judith L. (1983). "Parental investment in the Chicken Turtle (Deirochelys reticularia)". Ecology. 64 (3): 419–425. Bibcode:1983Ecol...64..419C. doi:10.2307/1939959. JSTOR 1939959.

- Carr 1952, p. 317.

- Schwartz 1956, p. 472.

- Gibbons 1969, p. 372.

- Congdon, J.D. (2022). "Comparing Life Histories of the Shortest-Lived Turtle Known (Chicken Turtles, Dierochelys reticularia) with Long-Lived Blanding's Turtles (Emydoidea blandingii)". Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 21. doi:10.2744/CCB-1521.1.

- Gibbons 1969, p. 371.

- ^ Ernst & Lovich 2009, p. 231.

- ^ Demuth, Jeffrey P.; Buhlmann, Kurt A. (1997). "Diet of the Turtle Deirochelys reticularia on the Savannah River Site, South Carolina". Journal of Herpetology. 31 (3): 450–453. doi:10.2307/1565680. JSTOR 1565680.

- Hibbitts & Hibbitts 2016, p. 161.

- Redmer, Michael; Parris, Matthew J. (2005). "Family Ranidae". In Rannoo, Michael (ed.). Amphibian Declines. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 538. doi:10.1525/9780520929432. ISBN 0-520-23592-4.

- Jackson, Dale R. (1996). "Meat on the Move: Diet of a Predatory Turtle, Deirochelys reticularia (Testudines : Emydidae)" (PDF). Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 2 (1): 105–108.

- McKnight, Donald T.; Jones, Anne C.; Ligon, Day B. (2015). "The Omnivorous Diet of the Western Chicken Turtle (Deirochelys reticularia miaria)". Copeia. 103 (2): 322–328. doi:10.1643/CH-14-072. S2CID 86844313.

- ^ Guyer, Bailey & Mount 2015, p. 163.

- Buhlmann, Tuberville & Gibbons 2008, p. 87.

- ^ Buhlmann, Tuberville & Gibbons 2008, p. 88.

- Walsh, Timothy J.; Heinrich, George L. (2015). "Red-shouldered hawk (Buteo lineatus) predation of turtles in central Florida". Florida Field Naturalist. 43 (2): 79–85.

- ^ Buhlmann, Gibbons & Jackson 2008, p. 014.5.

- Fain, Alex (1968). "Notes sur les Acariens de la famille Cloacaridae, Camin et al., parasites du cloaque et des tissus profonds des tortues (Cheyletoidea: Trombidiformes)" (PDF). Bulletin de l'Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique. 44 (15): 1–33.

- Loftin, Horace (1960). "An annotated check-list of trematodes and cestodes and their vertebrate hosts from northwest Florida". Quarterly Journal of the Florida Academy of Sciences. 23 (4): 302–314. JSTOR 24314969.

- Wharton, G. W. (1940). "The genera Telorchis, Protenes, and Auridistomum (Trematoda: Reniferidae)". The Journal of Parasitology. 26 (6): 497–518. doi:10.2307/3272252. JSTOR 3272252.

- Roberts, Jackson R.; Orélis-Ribeiro, Raphael; Halanych, Kenneth M.; Arias, Cova R.; Bullard, Stephen A. (2016). "A new species of Spirorchis MacCallum, 1918 (Digenea: Schistosomatoidea) and Spirorchis cf. scripta from chicken turtle, Deirochelys reticularia (Emydidae), with an emendation and molecular phylogeny of Spirorchis". Folia Parasitologica. 63: 041. doi:10.14411/fp.2016.041. PMID 28003567.

- Newell Peacock, Leslie (2018-07-12). "Game and Fish ponders banning turtle harvest". arktimes.com. Arkansas Times. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- Trauth, Robison & Plummer 2004, p. 222.

- Ernst & Lovich 2009, p. 232.

- Siler, Cameron D.; Freitas, Elyse S.; Yuri, Tamaki; Souza, Lara; Watters, Jessa L. (2020). "Development and validation of four environmental DNA assays for species of conservation concern in the South-Central United States". Conservation Genetics Resources. 13: 35–40. doi:10.1007/s12686-020-01167-3. S2CID 224943576.

Bibliography

- Agassiz, Louis (1857). Contributions to the natural history of the United States of America. Vol. 1. Boston, Massachusetts: Little, Brown and Company. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.12644. Retrieved 2022-02-24.

- Buhlmann, Kurt A.; Gibbons, J. Whitfield; Jackson, Dale R. (2008). "Deirochelys reticularia (Latreille 1801) – Chicken Turtle" (PDF). Chelonian Research Monographs. 5. Lunenburg, Massachusetts: Chelonian Research Foundation: 014.1 – 014.6. doi:10.3854/crm.5.014.reticularia.v1.2008. ISSN 1088-7105. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- Buhlmann, Kurt; Tuberville, Tracey; Gibbons, Whit (2008). "Chicken Turtle". Turtles of the Southeast. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press. pp. 84–88. ISBN 978-0-8203-2902-4. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- Carr, Archie F. (1952). "Genus Deirochelys: The Chicken Turtles". Handbook of Turtles: The Turtles of the United States, Canada, and Baja California (paperback ed.). Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 316–319. doi:10.7591/9781501722479-007. ISBN 0-8014-8254-2. S2CID 239377136.

- Ernst, Carl H.; Barbour, Roger William (1972). "Deirochelys reticularia". Turtles of the United States. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. pp. 174–178. ISBN 0-8131-1272-9. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- Ernst, Carl H.; Lovich, Jeffrey E. (2009). "Chicken Turtles". Turtles of the United States and Canada. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 222–232. ISBN 978-0-8018-9121-2. Retrieved 2022-02-24.

- Gibbons, J. Whitfield (1969). "Ecology and Population Dynamics of the Chicken Turtle, Deirochelys reticularia". Copeia. 1969 (4). American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists: 669–676. doi:10.2307/1441791. JSTOR 1441791.

- Guyer, Craig; Bailey, Mark A.; Mount, Robert H. (2015). "Chicken Turtles". Turtles of Alabama. Gosse Nature Guides. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. pp. 160–163. ISBN 978-0-8173-5806-8.

- Hibbitts, Troy D.; Hibbitts, Terry L. (2016). "Chicken Turtle". Texas Turtles & Crocodilians: A Field Guide. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. pp. 159–162. doi:10.7560/307779-005. ISBN 978-1-4773-0777-9.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Jackson, Dale R. (1978). "Evolution and fossil record of the chicken turtle Deirochelys, with a re-evaluation of the genus". Tulane Studies in Zoology and Botany. 20. New Orleans, Louisiana: Tulane University: 35–56. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- Lovich, Jeffrey E.; Gibbons, Whit (2021). "Chicken Turtles". Turtles of the World. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 82–83. doi:10.1515/9780691229034. ISBN 978-1-4773-0777-9. S2CID 245884540.

- Rhodin, A. G. J.; Iverson, J. B.; Bour, R.; Fritz, U.; Georges, A.; Shaffer, H. B.; Van Dijk, P. P. (2021). "Turtles of the World: Annotated Checklist and Atlas of Taxonomy, Synonymy, Distribution, and Conservation Status (9th Ed.)" (PDF). Chelonian Research Monographs. 8. Lunenburg, Massachusetts: Chelonian Research Foundation: 1–472. doi:10.3854/crm.8.checklist.atlas.v9.2021. ISBN 9780991036837. ISSN 1088-7105. S2CID 244279960. Retrieved 2022-04-25.

- Schwartz, Albert (1956). "Geographic variation in the chicken turtle". Fieldiana: Zoology. 34 (41). Chicago, Illinois: Chicago Natural History Museum: 461–503. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- Trauth, Stanley E.; Robison, Henry W.; Plummer, Michael V. (2004). "Western Chicken Turtle—Deirochelys reticularia miaria Schwartz". The Amphibians and Reptiles of Arkansas. Fayetteville, Arkansas: The University of Arkansas Press. pp. 220–222. ISBN 1-55728-737-6. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- Zug, George R.; Schwartz, Albert (1971). "Deirochelys, D. reticularia" (PDF). Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles: 107.1 – 107.3. doi:10.15781/T2ST7F22C. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

| Emydidae family | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Genera |

|  | ||

| Chrysemys | ||||

| Clemmys | ||||

| Deirochelys | ||||

| Actinemys | ||||

| Emys | ||||

| Emydoidea | ||||

| Glyptemys | ||||

| Graptemys | ||||

| Malaclemys | ||||

| Pseudemys | ||||

| Terrapene | ||||

| Trachemys | ||||

| †Wilburemys | ||||

| Phylogenetic arrangement of turtles based on turtles of the world 2017 update: Annotated checklist and atlas of taxonomy, synonymy, distribution, and conservation status. Key: †=extinct. | ||||

| Taxon identifiers | |

|---|---|

| Deirochelys reticularia | |