| Revision as of 21:52, 20 May 2005 editHalibutt (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers34,067 edits rv. Zinvi, before you add even more POV, please drop in to the talk page and explain it.← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 18:18, 25 December 2024 edit undoHedviberit (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users4,557 edits →Ethnography | ||

| (567 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Historical region in present-day Lithuania and Belarus}} | |||

| {{NPOV}} | |||

| {{Redirect2|Vilna land|Vilnius Land|Vilnius Region in the interwar period|Wilno Voivodeship (1926–39)}} | |||

| {{cleanup}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] (green) created by the ] as compared with the ], attempted to create in 1918 on the core territory of the former ] {{circa|1921}}.]] | |||

| '''Vilnius Region'''{{Ref label|a|a|none}} is the territory in present-day ] and ] that was originally inhabited by ethnic ] and was a part of ], but came under ] and ] cultural influences over time. | |||

| The territory included ], the historical capital of the ]. Lithuania, after ] from the ], claimed the Vilnius Region based on this historical legacy. Poland argued for the right of ] of the local Polish-speaking population. As a result, throughout the ] the control over the area was disputed between ] and Lithuania. The ] recognized it as part of Lithuania in the ], but in 1920 it was seized by Poland and became part of the short-lived ] of ], and was subsequently incorporated into the ]. | |||

| '''Vilnius region''' refers to territory of ] which was under ] control in the ] period. Major cities of Vilnius region are ], ] and ]. The region was first controlled by Lithuania, then taken by troops of general ]. Because capital of Lithuania ] was located in the region, Lithuania moved its ] to ], which was declared a ]. Polish version however states that the invasion to Vilnius region wasn't an occupation, because in the city of Vilnius Poles made a majority. However, Lithuanians tends to deny this version because in parts of Vilnius region ] were making up a majority, while in other parts ] were a majority, and in some cities and towns - ]; so Poles were making up only about 60% population. Therefore Lithuanians say that Lithuania had more rights to the territory and to the establishment of multiethnic zone rather than Poles because territory was historically Lithuanian (both politically and ethnically) and Vilnius was a historical capital of Lithuania, and it never belonged to Poland. At first, Poles tried to set up a state ], which was arguably (again, Polish and Lithuanian vesions differ here) semi-independent in that multiethnic territory (it did not encompassed whole Vilnius region however, but just some parts of it). Then however the territory was fully attached to Poland, mostly as part of newly created ], other parts were in ] and ]. Lithuania didn't take away the claim on territory however. In Vilnius region, Lithuanians were discriminated, Lithuanian schools were being closed down. Percentage of Lithuanian population was decreasing, especially in Polish-dominated areas. Jews also faced discrimination, same as elsewhere in Poland: for example, the amount of Jews who could enter ] (named ] university then) was limited and they were sitting in specially designated places. Because, although Jews back then didn't have good rights anywhere in Eastern Europe, in Lithuania they had better rights, some Poles were afraid that if a referendum would be done Jews would vote against being part of Poland. However, referendum was done, and it was voted for being part of Poland. However, because it was done under Polish administration, its results can be disputed, and as well the electoral boundary, according to which elections to ] Vilnius parliament were organised, was not drawn to encompass Vilnius region, but instead it encompassed some territories which weren't part of Vilnius region nor claimed by Lithuania, but excluded non-Polish inhabitated areas, which were part of Vilnius region. Lithuania therefore didn't recognised these elections or the referendum and continued to claim Vilnius as its capital, seeking foreign countries support on this. In 1927 however the situation of war was removed in Lithuania. In ], when whole Europe was looking at events related to Nazi Germany, Poland used the time to give ] to Lithuania, which required to renew diplomatic relations between Lithuania and Poland, and this way de facto recognise Vilnius region as part of Poland. Otherwise the war would be between two countries. Understanding that Lithuania would most likely loose such war, it accepted ultimatum, which led to quiet protests in Lithuania. In 1939 Germany offered Lithuania to strike against Poland together, president of Lithuania ] at the time however didn't believed that ] would win the war, and he opposed nazism, so he decided against that, although with the help of Germany and Polish forces having to fight on two fronts Lithuania would have most likely been able to retake Vilnius region. By the time Lithuania was in German sphere of influence according to ], however later it was exchanged with Russia for Eastern Poland. In 1939 Soviets gave proposal to Lithuania to give 1/5th of Vilnius region, including city of Vilnius itself, to Lithuania in exchange for stationing Soviet troops in Lithuania. Lithuanians at first didn't want to accept this, but later Russians said that troops would enter Lithuania anyways, so Lithuania accepted the deal. 1/5th of Vilnius region was ceded, despite of the fact that Soviet Union always recognised whole Vilnius region as part of Lithuania previously. Eventually Lithuania was annexed by Russia, then some more territories were attached to newly formed ], during German occupation even more were added, however not whole Vilnius region, and Lithuania wasnt independent then. Today most of Vilnius region is part of ] (see ]), while the part ceded back to Lithuania remains part of Lithuania (see ]). | |||

| Direct military conflicts (] and ]) were followed up by fruitless negotiations in the ]. After the ] in 1939, as part of the Soviet fulfilment of the ], the entire region was occupied by the Soviet Union. About one-fifth of the region, including Vilnius, was ceded to Lithuania by the Soviet Union on 10 October 1939 in exchange for ] bases within the territory of Lithuania as part of the ]. The remaining part of the region was given to the ]. | |||

| Also see: | |||

| *] | |||

| The conflict over Vilnius Region was settled after ] when both Poland and Lithuania were in the ], as Poland was the Soviet satellite state of the ] and Lithuania was occupied by the Soviet Union as the ], and ]. From the late 1940s to 1990, the region was divided between the Lithuanian SSR and Byelorussian SSR, and since 1990 between modern-day independent Lithuania and Belarus. | |||

| ] | |||

| ==Territory and terminology== | |||

| {{unreferenced section|date=March 2017}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Initially, the Vilnius Region did not possess exact borders per se, but encompassed Vilnius and the surrounding areas. This territory was disputed between Lithuania and Poland after both countries had successfully reestablished their independence in 1918. Later, the western limit of the region became a '']'' administration line between Poland and Lithuania following Polish military action in autumn 1920. Lithuania refused to recognize this action or the border. The eastern limit was defined by the ]. The eastern line was never turned into an actual border between states and remained only a political vision. The total territory covered about {{convert|32250|km2|abbr=on}}. | |||

| Today the eastern limit of the region lies between the Lithuanian and Belarusian border. This border divides the Vilnius Region into two parts: western and eastern. The Western Vilnius Region, including Vilnius, is now part of Lithuania. It constitutes about one-third of the total Vilnius Region. Lithuania gained about {{convert|6880|km2|abbr=on}} on October 10, 1939, from the Soviet Union and {{convert|2650|km2|abbr=on}} (including ] and ]) on August 3, 1940, from the Byelorussian SSR. The Eastern Vilnius Region became part of Belarus. No parts of the region are in modern Poland. None of the countries have any further territorial claims. | |||

| The term ''Central Lithuania'' refers to the short-lived puppet state of the ], proclaimed by ] after ] in the annexed areas. After eighteen months of existing under Poland's military protection, it was annexed by Poland on 24 March 1922 thus finalizing Poland's claims over the territory. | |||

| ==Vilnius dispute== | |||

| ] ethnographic boundaries and territorial claims]] | |||

| ] and Lithuania, criticizing Lithuanian unwillingness to compromise over Vilnius region. Marshal Piłsudski offers the sausage labelled "agreement" to the dog (with the collar labelled Lithuania); the dog barking "Wilno, wilno, wilno" replies: "Even if you were to give me Wilno, I would bark for ] and ] because this is who I am."]] | |||

| ] in interwar Poland]] | |||

| ] soldiers parade in the ], 1919]] | |||

| In the ], Vilnius and its environs had become a nucleus of the early ethnic Lithuanian state, the ], also referred to in Lithuanian historiography as a part of the ],<ref>{{cite journal | last=Smetona | first=Antanas | author-link= Antanas Smetona | title= Lithuania Propria| journal= Darbai ir dienos | volume= 3 | pages=191–234 | language=lt | issue=12}}</ref><ref>{{in lang|lt}} Viduramžių Lietuva {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070419214013/http://viduramziu.lietuvos.net/socium/provincijos.htm |date=2007-04-19 }}. Retrieved on 2007.04.11</ref> that became ] and later ]. | |||

| After the ] in the late 18th century it was annexed by the ] which established the ] there. As a result of ], it was seized by Germany and given to the civilian administration of the ]. With the German defeat in World War I and the outbreak of hostilities between various factions of the ], the area was disputed by the newly established Lithuanian, Polish and ] states. | |||

| Poles based their claims on demographic grounds and pointed to the will of the inhabitants. Lithuanians used geographical and historical arguments and underlined the role Vilnius played as the capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.{{Sfn|Owsinski|Eberhardt|p=36|ps=; Lithuanians used historical and geographical arguments to defend their claims, Poles pointed to the overwhelmingly Polish ethnic character of the Land of Vilnius, and to the explicit will of its inhabitants.|2003}}{{Sfn|Balkelis|2013|p=244|ps=; Lithuanians based their claims to Vilnius on its role as the historical capital of the medieval Grand Duchy of Lithuania, whereas Poland staked its claim on the grounds that the city and surrounding area were predominantly ethnically Polish.}} According to Lithuanian national activists, Poles and Belarusians of the region were "] Lithuanians".{{Sfn|Borzecki|2008|p=35}}{{Ref label|b|b|none}} Their view is confirmed by both Polish{{Sfn|Turska|1930|pp=219-225}} and Lithuanian research.{{Sfn|Lipscomb|Committee for a Free Lithuania|1958|p=A4962}}{{Sfn|Budreckis|1967}}{{Sfn|Šapoka|2013|p=216}}{{Sfn|Zinkevičius|2014}} | |||

| The ] of September 1917, organized by Lithuanian activists under ], elected a ], and an ] proclaimed an independent Lithuanian state with its capital in Vilnius. The Lithuanian government, however, failed to recruit soldiers among the Vilnius area inhabitants and was unable to organize the defence of the region against the ]. During November and December 1918, local Polish self-defence formations were created in Vilnius and many surrounding localities. They were formally included into the Polish Army by the end of the year. The Lithuanian ] left Vilnius together with the German garrison at the start of January 1919, when the first Polish-Soviet military clashes occurred east of the city.{{Sfn|Borzecki|2008|pp=2-3, 10-11}} | |||

| After the outbreak of the ], during the summer offensive of the ], the region got under Soviet control as the part of planned ] (Litbel). Following ], ] signed the ] with Lithuania on 12 July 1920.{{Sfn|Čepėnas|1992}} According to it, all area disputed between Poland and Lithuania, at the time controlled by the Bolsheviks, was to be transferred to Lithuania. However, the actual control over the area remained in the Bolsheviks' hands. After the ] it became clear that the advancing ] would soon recapture the area. Seeing that they could not secure it, the Bolshevik authorities started to transfer the area to Lithuanian sovereignty. The advancing Polish Army managed to retake much of the disputed area before the Lithuanians arrived, while the most important part of it with the city of Vilnius was secured by Lithuania. | |||

| ] | |||

| Due to Polish-Lithuanian tensions, the ] withheld diplomatic recognition of Lithuania until 1922.{{Sfn|Salzmann|2013|p=93}} | |||

| Since the two states were not at war, diplomatic negotiations were begun. The negotiations and international mediation led to nowhere and until 1920 the disputed territory remained divided into a Lithuanian and a Polish part. | |||

| In the 1920s, ] twice attempted to organise plebiscites, although neither side was eager to participate. After a staged mutiny by ] Poles took control over the area, and organised ], which were boycotted by most Lithuanians, but also by many Jews and Belarusians{{Sfn|Kiaupa|2004}} because of strong Polish military control. | |||

| The Polish government never acknowledged the Russo-Lithuanian convention of July 12, 1920, that granted the latter state territory seized from Poland by the Red Army during the Polish–Soviet War, then promised to Lithuania as the Soviet forces were retreating under the Polish advance; particularly as the Soviets had previously renounced claims to that region in the ]. In turn, the Lithuanian authorities did not acknowledge the Polish–Lithuanian border of 1918–1920 as permanent nor did they ever acknowledge the sovereignty of the puppet Republic of Central Lithuania. | |||

| ] parade in the ], Vilnius, 1939]] | |||

| In 1922 the Republic of Central Lithuania voted to join Poland and the choice was later accepted by the League of Nations,{{Sfn|Krajewski|1996}} The area granted to Lithuania by the Bolsheviks in 1920 continued to be claimed by Lithuania, with the city of Vilnius being treated as that state's official capital and the ] in ], and the states officially remained at war. It was not until the Polish ultimatum of 1938, that the two states resolved diplomatic relations. | |||

| Some historians speculated, that the loss of Vilnius might have nonetheless safeguarded the very existence of the Lithuanian state in the interwar period. Despite an alliance with the Soviets (Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty) and the war with Poland, Lithuania was very close to being invaded by the Soviets in the summer of 1920 and having been forcibly converted into a socialist republic. They believe it was only the Polish victory against the Soviets in the Polish–Soviet War (and the fact that the Poles did not object to some form of Lithuanian independence) that derailed the Soviet plans and gave Lithuania an experience of interwar independence.{{Sfn|Senn|1962|pp=500-507|ps=; A Bolshevik victory over the Poles would have certainly meant a move by the Lithuanian communists, backed by the Red Army, to overthrow the Lithuanian nationalist government... Kaunas, in effect, paid for its independence with the loss of Vilna.}}{{Sfn|Senn|1992|p=163|ps=; If the Poles didn't stop the Soviet attack, Lithuania would fell to the Soviets... Polish victory costs the Lithuanians the city of Wilno, but saved Lithuania itself.}}{{Sfn|Rukša|1982|p=417|ps=; In summer 1920 Russia was working on a communist revolution in Lithuania... From this disaster, Lithuania was saved by the ].}}<ref>Jonas Rudokas, (Polish translation of a Lithuanian article) "Veidas", 25 08 2005: '' "defended both Poland and Lithuanian from Soviet domination"''</ref> | |||

| In 1939, the Soviets proposed to sign the ]. According to this treaty, about one-fifth of the Vilnius Region, including the city of Vilnius itself, was returned to Lithuania in exchange for stationing 20,000 Soviet troops in Lithuania. Lithuanians at first did not want to accept this, but later the Soviet Union said that troops would enter Lithuania, anyway, so Lithuania accepted the deal. 1/5 of the Vilnius region was ceded, even though the Soviet Union always recognised the whole Vilnius region as part of Lithuania previously. ] unitl June 1940, when the entire Lithuania was annexed by the Soviet Union. | |||

| The Soviet Union was awarded the Vilnius region during the ], and it subsequently became part of the ]. ] to Poland. | |||

| ==Ethnography== | |||

| {{main|Demographic history of the Vilnius region}} | |||

| ] (1876)]] | |||

| The area was originally inhabited by Lithuanian ]. It was subjected to East Slavic and Polish cultural influences and settlement, which led to its gradual Ruthenization and Polonization.{{Sfn|Barwiński|Leśniewska|2010|pp=95-98}}{{Sfn|Ochmański|1981|p=81}} According to ], Vilnius was culturally Polish by the 17th century.{{Sfn|Davies|2005|p=29}} {{ill|Jerzy Ochmański|pl}} writes that by the 18th and 19th centuries, the city's environs were predominantly Slavic, while the Vilnius region became more and more ethnically diverse Belarusian-Polish-Lithuanian territory. Belarusians migrated into the south-eastern Lithuanian areas that were destroyed by conflicts of the 17th and 18th century (particularly the counties of Vilnius, ], ] and northern ]). As a result, only a handful of localities maintained their Lithuanian ethnic character there.{{Sfn|Ochmański|1986|p=314|ps= : "As late as the sixteenth century, the Lithuanian population occupied the counties of Trakai and Vilnius, the northern part of the Ašmena county (Ašmiana in Belorussian) and most of Švenčionys county. After the wars of the second half of the seventeenth century and the early eighteenth century, the Belarussian population started to move into those devastated territories and only a few Lithuanian settlements were preserved, surrounded by gudai. Even Vilnius was almost completely surrounded by Slavs by the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries."}} | |||

| According to the ] (which studied the linguistic situation, but didn't include the category of ethnic affiliation){{Sfn|Karjaharm|2010|pp=32-33}}) the ] was occupied predominantly by Belarusian speakers (56,05%), while Polish speakers amounted to only 8,17% of the population.<ref name="Demoskop">{{in lang|ru}} .</ref> The Russians maintained that the local Polish population consisted mainly of nobles, while the region's peasantry could not be Polish.{{Sfn|Borzecki|2008|pp=2-3, 10-11}} The later German (1916) and Polish (1919) censuses showed that Vilnius and its environs had a Polish majority.{{Sfn|Borzecki|2008|pp=2-3, 10-11}}{{Sfn|Łossowski|1995|p=11, 104}} Vilnius at that point was divided nearly evenly between Poles and Jews, with Lithuanians constituting a mere fraction (about 2–2.6%) of the total population,{{Sfn|Łossowski|1995|p=11, 104}}{{Sfn|Brensztejn|1919|pp=8, 21}}{{Sfn|Romer|1920|p=31}}, but these figures were questioned by the Lithuanian side already after the censuses were performed, pointing to the fact, that even German censuses in 1915-1916 were actually carried out predominantly by the ] on site.{{citation needed|date=December 2024}} These censuses and their organisation were heavily criticized by contemporary Lithuanians of the region as biased.{{Sfn|Bieliauskas|2009}}{{Sfn|Klimas|1991|p=148}}{{Sfn|Merkys|2004|pp=408-409}} | |||

| At the end of the First World War, 50% of the Vilnius inhabitants were Polish and 43% were Jewish. According to E. Bojtar, who cites P. Gaučas, the surrounding villages were mainly inhabited by Belarusian speakers who considered themselves Poles.{{Sfn|Bojtar|2000|p=201}} There was also a large group who chose their self-declared national identification in accordance with the particular political situation.{{Sfn|Owsinski|Eberhardt|2003|pp=48, 59}} According to the ] conducted by the German authorities Lithuanians constituted 18.5% of the population. However, during this census the Vilnius region was expanded greatly and ended near ], and included the city of ]. Due to the addition of further Polish regions, the percentage of the Lithuanian population was diluted. The questioned by ] side post-war Polish censuses of 1921 and 1931, found 5% of Lithuanians living in the area, with several almost purely Lithuanian enclaves located to the south-west, south (] enclave), east (] enclave) of Vilnius and to the north of ]. The majority of the population was composed of Poles (roughly 60%) according to the latter three censuses. and the Lithuanian government claimed that the majority of local Poles were in fact ] Lithuanians.{{Sfn|Kiaupa|2004}} Today, the '']'' dialect is the native language for Poles in ] and in some territories of ]; its speakers consider themselves to be Poles and believe ''Po prostu'' language to be purely Polish.{{Sfn|Čekmonas|Grumadienė|2017}}{{Sfn|Garšva|Grumadienė|1993|p=132}}<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.istorija.lt/le/kalnius1998_summary.html |title=Archived copy |access-date=2009-10-22 |archive-date=2009-08-18 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090818053230/http://www.istorija.lt/le/kalnius1998_summary.html |url-status=dead }}</ref> The population, including those of "the locals" (Tutejshy) who live in the other part of Vilnius region that was occupied by the Soviet Union and passed on to Belarus, still has a strong presence of Polish identity. Despite the fact, that this language is the ] Belarusian vernacular<ref>{{cite web |last1=Radczenko |first1=Antoni |title=Jankowiak: Polacy na Wileńszczyźnie mówią gwarą białoruską |url=https://kresy24.pl/jankowiak-polacy-na-wilenszczyznie-mowia-gwara-bialoruska/ |website=Kresy24.pl |access-date=22 April 2020 |language=pl-PL |date=27 August 2015}}</ref> with ] relics from Lithuanian language,{{Sfn|Garšva|Grumadienė|1993|p=132}} its speakers consider themselves to be Poles and believe ''Po prostu'' dialect to be purely Polish.{{Sfn|Garšva|Grumadienė|1993|p=132}}<ref>{{cite web |last1=Kalnius |first1=Petras |title=Ethnic Processes in Southeastern Lithuania in the 2nd half of the 20th c. |url=http://www.istorija.lt/le/kalnius1998_summary.html |website=istorija.lt |access-date=22 April 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140502002154/http://www.istorija.lt/le/kalnius1998_summary.html |archive-date=2 May 2014 |date=17 August 2004}}</ref> The population, including those of "the locals" (]) who live in the other part of Vilnius region that was occupied by the Soviet Union and passed on to Belarus, still has a strong presence of Polish identity. | |||

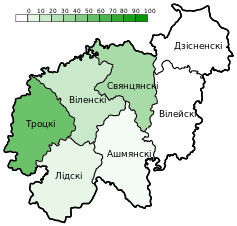

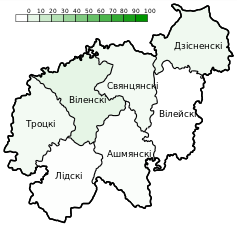

| <gallery mode="packed" caption="Census in 1897" perrow="4" heights="150px"> | |||

| Віленская губерня. Першая па колькасці нацыянальнасць. 1897.svg|Language spoken. Majorities. Green - ], yellow - ]. Note: relative majority in Vilnius uyezd. ]: (25,8 % with ] city; 41,85% if excluding Vilnius), ]: (20,93 % with ] city; 34,92% if excluding Vilnius)<ref>{{cite web|url=http://demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/rus_lan_97_uezd.php?reg=90|title=Первая всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г. Виленский уезд, весь.}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/rus_lan_97_uezd.php?reg=92|title=Первая всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г. Виленский уезд без города}}</ref> | |||

| Віленская губерня. Доля беларусаў. 1897.svg|] | |||

| Віленская губерня. Доля літоўцаў. 1897.svg|] | |||

| Віленская губерня. Доля яўрэяў. 1897.svg|], speaking Litvish dialect of ] | |||

| Віленская губерня. Доля палякаў. 1897.svg|] | |||

| Віленская губерня. Доля вялікарускаў (рускіх). 1897.svg|] | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| After the ], ] and migrations, Lithuanians became the undisputed ethnic majority in the Vilnius region in 1989 (50,5%).<ref>{{cite web |last1=Stravinskienė |first1=Vitalija |title=Migracijos procesai Vilniuje: kaip ir kodėl per sovietmetį keitėsi Vilniaus gyventojų sudėtis |url=https://www.15min.lt/media-pasakojimai/migracijos-procesai-vilniuje-kaip-ir-kodel-per-sovietmeti-keitesi-vilniaus-gyventoju-sudetis-1212 |website=] |access-date=20 June 2021 |language=lt}}</ref> The share of Lithuanians in the Vilnius city grew from 2% in the first half of the 20th century to 42.5% in 1970,{{Sfn|Szporluk|2000|p=47}} 57.8% in 2001 (while the total population of the city expanded several times).{{Sfn|Česnavičius|Stanaitis|2010|pp=33, 36}} and 67.1% in 2021. | |||

| The Poles are still concentrated in the area around Vilnius, and constituted 63.6% of the population in ] and 82.4% of the population in ] in 1989,{{Sfn|Owsinski|Eberhardt|2003|pp=48, 59}} By 2011 the number had shrunk to 52.07% of the population in ] and 77.75% in ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.osp.stat.gov.lt/documents/10180/217110/Gyv_gyvenamosiose_vietovese_atnaujintas_130125.xls/ |title=Gyventojai gyvenamosiose vietovėse |date=2013-01-25 |publisher=] |access-date=2017-02-25 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170202041346/https://osp.stat.gov.lt/documents/10180/217110/Gyv_gyvenamosiose_vietovese_atnaujintas_130125.xls |archive-date=2017-02-02 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| <gallery> | |||

| File:Lithuanian language in the 16th century.png|Lithuanian language in the 16th century | |||

| File:Eldership of Samogitia (Žemaitija) within Lithuania in the 17th century.png|Lithuania in the 17th century | |||

| File:Polska1912.jpg|Polish ethnographic map from 1912, showing the proportions of Polish population on the territory of the former ], according to pre-war censuses | |||

| File:Mapa rozsiedlenia ludności polskiej z uwzględnieniem spisów z 1916 roku.jpg|Polish ethnographic map from 1916, showing the proportions of Polish population, according to German censuses of 1916 | |||

| File:Litwa-polacy.png|Percentage of Poles by municipalities (2011 census) | |||

| File:Map of Lithuanian language.svg|Lithuanian language in the early 21st century | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{refbegin}} | |||

| '''a.''' {{Note label|a|a|none}} {{langx|lt|Vilniaus kraštas}} or ''Vilnija''; {{langx|pl|Wileńszczyzna}}; {{langx|be|Віленшчына}}. Also formerly known in English as ''Vilna Region'' or ''Wilno Region''. | |||

| '''b.''' {{Note label|b|b|none}} ''According to one of the leading Lithuanian national activists, ], "the issue of belonging to a certain nationality is not decided by everyone at will, it is not a matter that can be resolved according to the principles of political liberalism, even one cloaked in democratic slogans." Another leading activist, ], had already declared in September 1917: "Giving the right of self-determination to the inhabitants of Wilno, a population devoid of culture, would mean giving an opportunity to agitators to fool people. The thing is to unite former branches with the old trunk. Based on that, we draw the border far beyond Wilno, near Oszmiana. Lida County is also Lithuanian..."''{{Sfn|Borzecki|2008|p=322}} | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| ==Sources== | |||

| {{refbegin|40em}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Balkelis |first=Tomas |title=Shatterzone of Empires: Coexistence and Violence in the German, Habsburg, Russian, and Ottoman Borderlands |publisher=] |year=2013 |editor-last=Bartov |editor-first=Omer |pages=243–257 |chapter=Nation State, Ethnic Conflict, and Refugees in Lithuania: 1939–1940 |editor-last2=Weitz |editor-first2=Eric D.}} | |||

| * {{Cite magazine |last1=Barwiński |first1=Marek |last2=Leśniewska |first2=Katarzyna |date=2010 |title=Vilnius region as a historical region |magazine=Region and Regionalism |volume=10 |pages=}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Bieliauskas |first=Pranciškus |title=Vilniaus dienoraštis. 1915-1919 |year=2009 |location=Vilnius |language=lt}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Borzecki |first=Jerzy |title=The Soviet-Polish Peace of 1921 and the creation of interwar Europe |publisher=] |year=2008}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Bojtar |first=E. |title=Foreword to the past: a cultural history of the Baltic people. |publisher=] |year=2000}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Brensztejn |first=Michał Eustachy |title=Spisy ludności m. Wilna za okupacji niemieckiej od. 1 listopada 1915 r. |publisher=Biblioteka Delegacji Rad Polskich Litwy i Białej Rusi |year=1919 |location=Warsaw |language=pl}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal |last=Budreckis |first=Algirdas |date=1967 |title=Etnografinės Lietuvos Rytinės ir Pietinės Sienos |url=http://partizanai.org/karys-1967m-7-8/5742-etnografines-lietuvos-rytines-ir-pietines-sienos |journal=]}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Čepėnas |first=Pranas |title=Naujųjų laikų Lietuvos istorija |publisher=Dr. Griniaus fondas |year=1992 |isbn=5-89957-012-1 |volume=II |location=Chicago |language=lt |author-link=Pranas Čepėnas}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last1=Čekmonas |first1=Valerijus |title=Valerijus Čekmonas: kalbų kontaktai ir sociolingvistika |last2=Grumadienė |first2=Laima |publisher=Lietuvių kalbos institutas |year=2017 |isbn=9786094112010 |location=Vilnius |pages=108–114, 864–866, 965–967 |language=lt |chapter=Kalbų paplitimas Rytų Lietuvoje |trans-chapter=Distribution of languages in Eastern Lithuania}} | |||

| * {{Cite magazine |last1=Česnavičius |first1=Darius |last2=Stanaitis |first2=Saulius |date=2010 |title=Dynamics of national composition of Vilnius population in the 2nd half of the 20th century |magazine=Bulletin of Geography. Socio-economic Series. |issue=13 |pages=33–44}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Davies |first=Norman |title=God's Playground: The origins to 1795 |publisher=] |year=2005 |author-link=Norman Davies}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last1=Garšva |first1=Kazimieras |title=Lietuvos rytai: straipsnių rinkinys |last2=Grumadienė |first2=Laima |publisher=Valstybinis leidybos centras |year=1993 |isbn=9986-09-002-4 |location=Vilnius |language=lt |author-link=Kazimieras Garšva}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal |last1=Lipscomb |first1=Glenard P. |last2=Committee for a Free Lithuania |author2-link=Committee for a Free Lithuania |date=29 May 1958 |title=Extension of Remarks |url=https://archive.org/details/sim_congressional-record-proceedings-and-debates_may-27-june-19-1958_104_appendix/page/n107/mode/2up?q=Tutejszy |journal=] |volume=104 - Appendix}} | |||

| * {{Cite magazine |last=Karjaharm |first=Toomas |date=2010 |title=Terminology Pertaining to Ethnic Relations as Used in Late Imperial Russia |magazine=Acta Historica Tallinnensia |volume=15}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Klimas |first=Petras |title=Iš mano atsiminimų |publisher=Enciklopedijų Redakcija |year=1991 |location=Vilnius |language=lt |author-link=Petras Klimas}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Kiaupa |first=Zigmantas |title=The History of Lithuania |publisher=] |year=2004 |isbn=9955-584-87-4 |location=Vilnius |author-link=Zigmantas Kiaupa}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Krajewski |first=Zenon |title=Geneza i dzieje wewnętrzne Litwy Środkowej (1920-1922) |year=1996 |isbn=83-906321-0-1 |location=Lublin |language=pl |trans-title=The genesis and internal history of Central Lithuania (1920-1922)}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Łossowski |first=Piotr |title=Konflikt polsko-litewski 1918-1920 |publisher=Książka i Wiedza |year=1995 |isbn=83-05-12769-9 |location=Warsaw |language=pl |trans-title=The Polish-Lithuanian Conflict, 1918–1920 |author-link=Piotr Łossowski}} | |||

| * {{Cite magazine |last=Merkys |first=Vytautas |date=2004 |title=Tautinė Vilniaus vyskupijos gyventojų sudėtis 1867-1917 |magazine=Istorijos Akiračiai |language=lt}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Ochmański |first=Jerzy |title=Litewska granica etniczna na wschodzie: od epoki plemiennej do XVI wieku |publisher=] |year=1981 |language=pl |trans-title=Lithuanian ethnic border in the east: from the tribal era to the 16th century}} | |||

| * {{Cite magazine |last=Ochmański |first=Jerzy |date=1986 |title=The National Idea in Lithuania from the 16th to the First Half of the 19th Century: The Problem of Cultural-Linguistic Differentiation |magazine=] |volume=X |issue=3/4}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last1=Owsinski |first1=Jan |title=Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-Century Central-Eastern Europe |last2=Eberhardt |first2=Piotr |publisher=] |year=2003}} | |||

| * {{Cite magazine |last=Romer |first=Eugenjusz |date=1920 |title=Spis ludności na terenach administrowanych przez Zarząd Cywilny Ziem Wschodnich (Grudzień 1919) |trans-title=Census in the areas administered by the Civil Administration of the Eastern Territories (December 1919) |magazine=Prace Geograficzne |language=pl |issue=7}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Rukša |first=Antanas |title=Kovos dėl Lietuvos nepriklausomybės |year=1982 |volume=3 |location=Cleveland |language=lt}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Salzmann |first=Stephanie |title=Great Britain, Germany and the Soviet Union: Rapallo and After, 1922-1934 |publisher=] |year=2013}} | |||

| * {{Cite magazine |last=Senn |first=Alfred Erich |author-link=Alfred Erich Senn |date=1962 |title=The Formation of the Lithuanian Foreign Office, 1918-1921 |magazine=] |volume=21 |issue=3 |pages=500–507}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Senn |first=Alfred Erich |title=Lietuvos Valstybės Atkūrimas |publisher=Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidykla |year=1992}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Szporluk |first=Roman |title=Russia, Ukraine and the Breakup of the Soviet Union |publisher=] |year=2000}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Šapoka |first=Adolfas |url=https://archive.org/details/sapoka-rastai-t.-1-2013/page/216/mode/2up?q=Tutejszy |title=Raštai |publisher=Edukologija |year=2013 |volume=I - Vilniaus Istorija |location=Vilnius |language=Lithuanian}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Turska |first=Halina |url=https://kpbc.umk.pl/dlibra/publication/22328/edition/32190 |title=Wilno i Ziemia Wilenska |year=1930 |volume=I |language=Polish |chapter=Język polski na Wileńsczyzne|publisher=Polska Drukarnia Nakładowa "LUX" Ludwika Chomińskiego }} | |||

| * {{Cite news |last=Zinkevičius |first=Zigmas |author-link=Zigmas Zinkevičius |date=31 January 2014 |title=Lenkiškai kalbantys lietuviai |language=Lithuanian |trans-title=Polish-speaking Lithuanians |work=alkas.lt |url=https://alkas.lt/2014/01/31/z-zinkevicius-lenkiskai-kalbantys-lietuviai/}} | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| * | |||

| * {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110517121723/http://viduramziu.lietuvos.net/eo/etno19a-en.htm |date=2011-05-17 }} | |||

| * | |||

| {{coord|54|30|N|25|25|E|region:LT_type:adm1st|display=title}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 18:18, 25 December 2024

Historical region in present-day Lithuania and Belarus "Vilna land" and "Vilnius Land" redirect here. For Vilnius Region in the interwar period, see Wilno Voivodeship (1926–39).

Vilnius Region is the territory in present-day Lithuania and Belarus that was originally inhabited by ethnic Baltic tribes and was a part of Lithuania proper, but came under East Slavic and Polish cultural influences over time.

The territory included Vilnius, the historical capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Lithuania, after declaring independence from the Russian Empire, claimed the Vilnius Region based on this historical legacy. Poland argued for the right of self-determination of the local Polish-speaking population. As a result, throughout the interwar period the control over the area was disputed between Poland and Lithuania. The Soviet Union recognized it as part of Lithuania in the Soviet-Lithuanian Treaty of 1920, but in 1920 it was seized by Poland and became part of the short-lived puppet state of Central Lithuania, and was subsequently incorporated into the Second Polish Republic.

Direct military conflicts (Polish–Lithuanian War and Żeligowski's Mutiny) were followed up by fruitless negotiations in the League of Nations. After the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939, as part of the Soviet fulfilment of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, the entire region was occupied by the Soviet Union. About one-fifth of the region, including Vilnius, was ceded to Lithuania by the Soviet Union on 10 October 1939 in exchange for Soviet military bases within the territory of Lithuania as part of the Soviet–Lithuanian Mutual Assistance Treaty. The remaining part of the region was given to the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic.

The conflict over Vilnius Region was settled after World War II when both Poland and Lithuania were in the Eastern Bloc, as Poland was the Soviet satellite state of the Polish People's Republic and Lithuania was occupied by the Soviet Union as the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic, and Poles were repatriated to Poland. From the late 1940s to 1990, the region was divided between the Lithuanian SSR and Byelorussian SSR, and since 1990 between modern-day independent Lithuania and Belarus.

Territory and terminology

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (March 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Initially, the Vilnius Region did not possess exact borders per se, but encompassed Vilnius and the surrounding areas. This territory was disputed between Lithuania and Poland after both countries had successfully reestablished their independence in 1918. Later, the western limit of the region became a de facto administration line between Poland and Lithuania following Polish military action in autumn 1920. Lithuania refused to recognize this action or the border. The eastern limit was defined by the Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty. The eastern line was never turned into an actual border between states and remained only a political vision. The total territory covered about 32,250 km (12,450 sq mi).

Today the eastern limit of the region lies between the Lithuanian and Belarusian border. This border divides the Vilnius Region into two parts: western and eastern. The Western Vilnius Region, including Vilnius, is now part of Lithuania. It constitutes about one-third of the total Vilnius Region. Lithuania gained about 6,880 km (2,660 sq mi) on October 10, 1939, from the Soviet Union and 2,650 km (1,020 sq mi) (including Druskininkai and Švenčionys) on August 3, 1940, from the Byelorussian SSR. The Eastern Vilnius Region became part of Belarus. No parts of the region are in modern Poland. None of the countries have any further territorial claims.

The term Central Lithuania refers to the short-lived puppet state of the Republic of Central Lithuania, proclaimed by Lucjan Żeligowski after his staged mutiny in the annexed areas. After eighteen months of existing under Poland's military protection, it was annexed by Poland on 24 March 1922 thus finalizing Poland's claims over the territory.

Vilnius dispute

In the Middle Ages, Vilnius and its environs had become a nucleus of the early ethnic Lithuanian state, the Duchy of Lithuania, also referred to in Lithuanian historiography as a part of the Lithuania Propria, that became Kingdom of Lithuania and later Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

After the Partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the late 18th century it was annexed by the Russian Empire which established the Vilna Governorate there. As a result of World War I, it was seized by Germany and given to the civilian administration of the Ober-Ost. With the German defeat in World War I and the outbreak of hostilities between various factions of the Russian Civil War, the area was disputed by the newly established Lithuanian, Polish and Belarusian states.

Poles based their claims on demographic grounds and pointed to the will of the inhabitants. Lithuanians used geographical and historical arguments and underlined the role Vilnius played as the capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. According to Lithuanian national activists, Poles and Belarusians of the region were "Slavicized Lithuanians". Their view is confirmed by both Polish and Lithuanian research.

The Vilnius Conference of September 1917, organized by Lithuanian activists under German auspices, elected a council of Lithuania, and an Act of Independence of Lithuania proclaimed an independent Lithuanian state with its capital in Vilnius. The Lithuanian government, however, failed to recruit soldiers among the Vilnius area inhabitants and was unable to organize the defence of the region against the Bolsheviks. During November and December 1918, local Polish self-defence formations were created in Vilnius and many surrounding localities. They were formally included into the Polish Army by the end of the year. The Lithuanian Taryba left Vilnius together with the German garrison at the start of January 1919, when the first Polish-Soviet military clashes occurred east of the city.

After the outbreak of the Polish–Soviet War, during the summer offensive of the Red Army, the region got under Soviet control as the part of planned Lithuanian–Belorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (Litbel). Following Lithuanian–Soviet War, Bolshevik Russia signed the Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty with Lithuania on 12 July 1920. According to it, all area disputed between Poland and Lithuania, at the time controlled by the Bolsheviks, was to be transferred to Lithuania. However, the actual control over the area remained in the Bolsheviks' hands. After the Battle of Warsaw of 1920 it became clear that the advancing Polish Army would soon recapture the area. Seeing that they could not secure it, the Bolshevik authorities started to transfer the area to Lithuanian sovereignty. The advancing Polish Army managed to retake much of the disputed area before the Lithuanians arrived, while the most important part of it with the city of Vilnius was secured by Lithuania.

Due to Polish-Lithuanian tensions, the allied powers withheld diplomatic recognition of Lithuania until 1922. Since the two states were not at war, diplomatic negotiations were begun. The negotiations and international mediation led to nowhere and until 1920 the disputed territory remained divided into a Lithuanian and a Polish part.

In the 1920s, League of Nations twice attempted to organise plebiscites, although neither side was eager to participate. After a staged mutiny by Lucjan Żeligowski Poles took control over the area, and organised elections, which were boycotted by most Lithuanians, but also by many Jews and Belarusians because of strong Polish military control.

The Polish government never acknowledged the Russo-Lithuanian convention of July 12, 1920, that granted the latter state territory seized from Poland by the Red Army during the Polish–Soviet War, then promised to Lithuania as the Soviet forces were retreating under the Polish advance; particularly as the Soviets had previously renounced claims to that region in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. In turn, the Lithuanian authorities did not acknowledge the Polish–Lithuanian border of 1918–1920 as permanent nor did they ever acknowledge the sovereignty of the puppet Republic of Central Lithuania.

In 1922 the Republic of Central Lithuania voted to join Poland and the choice was later accepted by the League of Nations, The area granted to Lithuania by the Bolsheviks in 1920 continued to be claimed by Lithuania, with the city of Vilnius being treated as that state's official capital and the temporary capital in Kaunas, and the states officially remained at war. It was not until the Polish ultimatum of 1938, that the two states resolved diplomatic relations.

Some historians speculated, that the loss of Vilnius might have nonetheless safeguarded the very existence of the Lithuanian state in the interwar period. Despite an alliance with the Soviets (Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty) and the war with Poland, Lithuania was very close to being invaded by the Soviets in the summer of 1920 and having been forcibly converted into a socialist republic. They believe it was only the Polish victory against the Soviets in the Polish–Soviet War (and the fact that the Poles did not object to some form of Lithuanian independence) that derailed the Soviet plans and gave Lithuania an experience of interwar independence.

In 1939, the Soviets proposed to sign the Soviet–Lithuanian Mutual Assistance Treaty. According to this treaty, about one-fifth of the Vilnius Region, including the city of Vilnius itself, was returned to Lithuania in exchange for stationing 20,000 Soviet troops in Lithuania. Lithuanians at first did not want to accept this, but later the Soviet Union said that troops would enter Lithuania, anyway, so Lithuania accepted the deal. 1/5 of the Vilnius region was ceded, even though the Soviet Union always recognised the whole Vilnius region as part of Lithuania previously. Vilnius Region was under Lithuanian administration unitl June 1940, when the entire Lithuania was annexed by the Soviet Union.

The Soviet Union was awarded the Vilnius region during the Yalta Conference, and it subsequently became part of the Lithuanian SSR. About 150,000 of the Polish population was repatriated from Lithuanian SSR to Poland.

Ethnography

Main article: Demographic history of the Vilnius region

The area was originally inhabited by Lithuanian Balts. It was subjected to East Slavic and Polish cultural influences and settlement, which led to its gradual Ruthenization and Polonization. According to Norman Davies, Vilnius was culturally Polish by the 17th century. Jerzy Ochmański [pl] writes that by the 18th and 19th centuries, the city's environs were predominantly Slavic, while the Vilnius region became more and more ethnically diverse Belarusian-Polish-Lithuanian territory. Belarusians migrated into the south-eastern Lithuanian areas that were destroyed by conflicts of the 17th and 18th century (particularly the counties of Vilnius, Trakai, Švenčionys and northern Ašmena). As a result, only a handful of localities maintained their Lithuanian ethnic character there. According to the Russian census of 1897 (which studied the linguistic situation, but didn't include the category of ethnic affiliation)) the Vilna Governorate was occupied predominantly by Belarusian speakers (56,05%), while Polish speakers amounted to only 8,17% of the population. The Russians maintained that the local Polish population consisted mainly of nobles, while the region's peasantry could not be Polish. The later German (1916) and Polish (1919) censuses showed that Vilnius and its environs had a Polish majority. Vilnius at that point was divided nearly evenly between Poles and Jews, with Lithuanians constituting a mere fraction (about 2–2.6%) of the total population,, but these figures were questioned by the Lithuanian side already after the censuses were performed, pointing to the fact, that even German censuses in 1915-1916 were actually carried out predominantly by the Poles on site. These censuses and their organisation were heavily criticized by contemporary Lithuanians of the region as biased.

At the end of the First World War, 50% of the Vilnius inhabitants were Polish and 43% were Jewish. According to E. Bojtar, who cites P. Gaučas, the surrounding villages were mainly inhabited by Belarusian speakers who considered themselves Poles. There was also a large group who chose their self-declared national identification in accordance with the particular political situation. According to the 1916 census conducted by the German authorities Lithuanians constituted 18.5% of the population. However, during this census the Vilnius region was expanded greatly and ended near Brest-Litovsk, and included the city of Białystok. Due to the addition of further Polish regions, the percentage of the Lithuanian population was diluted. The questioned by Lithuanian side post-war Polish censuses of 1921 and 1931, found 5% of Lithuanians living in the area, with several almost purely Lithuanian enclaves located to the south-west, south (Dieveniškės enclave), east (Gervėčiai enclave) of Vilnius and to the north of Švenčionys. The majority of the population was composed of Poles (roughly 60%) according to the latter three censuses. and the Lithuanian government claimed that the majority of local Poles were in fact Polonised Lithuanians. Today, the Po prostu dialect is the native language for Poles in Šalčininkai District Municipality and in some territories of Vilnius District Municipality; its speakers consider themselves to be Poles and believe Po prostu language to be purely Polish. The population, including those of "the locals" (Tutejshy) who live in the other part of Vilnius region that was occupied by the Soviet Union and passed on to Belarus, still has a strong presence of Polish identity. Despite the fact, that this language is the uncodified Belarusian vernacular with substrate relics from Lithuanian language, its speakers consider themselves to be Poles and believe Po prostu dialect to be purely Polish. The population, including those of "the locals" (Tutejszy) who live in the other part of Vilnius region that was occupied by the Soviet Union and passed on to Belarus, still has a strong presence of Polish identity.

- Census in 1897

-

Language spoken. Majorities. Green - Belarusian-speaking population, yellow - Lithuanian-speaking population. Note: relative majority in Vilnius uyezd. Belarusian: (25,8 % with Vilnius city; 41,85% if excluding Vilnius), Lithuanian: (20,93 % with Vilnius city; 34,92% if excluding Vilnius)

Language spoken. Majorities. Green - Belarusian-speaking population, yellow - Lithuanian-speaking population. Note: relative majority in Vilnius uyezd. Belarusian: (25,8 % with Vilnius city; 41,85% if excluding Vilnius), Lithuanian: (20,93 % with Vilnius city; 34,92% if excluding Vilnius)

-

Belarusian-speaking population

Belarusian-speaking population

-

Lithuanian-speaking population

Lithuanian-speaking population

-

Lithuanian Jews, speaking Litvish dialect of Yiddish

Lithuanian Jews, speaking Litvish dialect of Yiddish

-

Polish-speaking population

Polish-speaking population

-

Russian-speaking population

Russian-speaking population

After the extermination of Jews, displacements and migrations, Lithuanians became the undisputed ethnic majority in the Vilnius region in 1989 (50,5%). The share of Lithuanians in the Vilnius city grew from 2% in the first half of the 20th century to 42.5% in 1970, 57.8% in 2001 (while the total population of the city expanded several times). and 67.1% in 2021. The Poles are still concentrated in the area around Vilnius, and constituted 63.6% of the population in Vilnius District Municipality and 82.4% of the population in Šalčininkai District Municipality in 1989, By 2011 the number had shrunk to 52.07% of the population in Vilnius District Municipality and 77.75% in Šalčininkai District Municipality.

-

Lithuanian language in the 16th century

Lithuanian language in the 16th century

-

Lithuania in the 17th century

Lithuania in the 17th century

-

Polish ethnographic map from 1912, showing the proportions of Polish population on the territory of the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, according to pre-war censuses

Polish ethnographic map from 1912, showing the proportions of Polish population on the territory of the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, according to pre-war censuses

-

Polish ethnographic map from 1916, showing the proportions of Polish population, according to German censuses of 1916

Polish ethnographic map from 1916, showing the proportions of Polish population, according to German censuses of 1916

-

Percentage of Poles by municipalities (2011 census)

Percentage of Poles by municipalities (2011 census)

-

Lithuanian language in the early 21st century

Lithuanian language in the early 21st century

See also

- Disputed territories of Baltic States

- Ethnographic Lithuania

- Union for the Liberation of Vilnius

- History of Vilnius

- Lithuanization

- Poles in Lithuania

- Polonization

- Polish National-Territorial Region

- Suwałki Region

- Liauda

Notes

a. Lithuanian: Vilniaus kraštas or Vilnija; Polish: Wileńszczyzna; Belarusian: Віленшчына. Also formerly known in English as Vilna Region or Wilno Region.

b. According to one of the leading Lithuanian national activists, Mykolas Biržiška, "the issue of belonging to a certain nationality is not decided by everyone at will, it is not a matter that can be resolved according to the principles of political liberalism, even one cloaked in democratic slogans." Another leading activist, Petras Klimas, had already declared in September 1917: "Giving the right of self-determination to the inhabitants of Wilno, a population devoid of culture, would mean giving an opportunity to agitators to fool people. The thing is to unite former branches with the old trunk. Based on that, we draw the border far beyond Wilno, near Oszmiana. Lida County is also Lithuanian..."

References

- Smetona, Antanas. "Lithuania Propria". Darbai ir dienos (in Lithuanian). 3 (12): 191–234.

- (in Lithuanian) Viduramžių Lietuva Viduramžių Lietuvos provincijos Archived 2007-04-19 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 2007.04.11

- Owsinski & Eberhardt 2003, p. 36; Lithuanians used historical and geographical arguments to defend their claims, Poles pointed to the overwhelmingly Polish ethnic character of the Land of Vilnius, and to the explicit will of its inhabitants.

- Balkelis 2013, p. 244; Lithuanians based their claims to Vilnius on its role as the historical capital of the medieval Grand Duchy of Lithuania, whereas Poland staked its claim on the grounds that the city and surrounding area were predominantly ethnically Polish.

- Borzecki 2008, p. 35.

- Turska 1930, pp. 219–225.

- Lipscomb & Committee for a Free Lithuania 1958, p. A4962.

- Budreckis 1967.

- Šapoka 2013, p. 216.

- Zinkevičius 2014.

- ^ Borzecki 2008, pp. 2–3, 10–11.

- Čepėnas 1992.

- Salzmann 2013, p. 93.

- ^ Kiaupa 2004.

- Krajewski 1996.

- Senn 1962, pp. 500–507; A Bolshevik victory over the Poles would have certainly meant a move by the Lithuanian communists, backed by the Red Army, to overthrow the Lithuanian nationalist government... Kaunas, in effect, paid for its independence with the loss of Vilna.

- Senn 1992, p. 163; If the Poles didn't stop the Soviet attack, Lithuania would fell to the Soviets... Polish victory costs the Lithuanians the city of Wilno, but saved Lithuania itself.

- Rukša 1982, p. 417; In summer 1920 Russia was working on a communist revolution in Lithuania... From this disaster, Lithuania was saved by the miracle at Vistula.

- Jonas Rudokas, Józef Piłsudski - wróg niepodległości Litwy czy jej wybawca? (Polish translation of a Lithuanian article) "Veidas", 25 08 2005: "defended both Poland and Lithuanian from Soviet domination"

- Barwiński & Leśniewska 2010, pp. 95–98.

- Ochmański 1981, p. 81.

- Davies 2005, p. 29.

- Ochmański 1986, p. 314: "As late as the sixteenth century, the Lithuanian population occupied the counties of Trakai and Vilnius, the northern part of the Ašmena county (Ašmiana in Belorussian) and most of Švenčionys county. After the wars of the second half of the seventeenth century and the early eighteenth century, the Belarussian population started to move into those devastated territories and only a few Lithuanian settlements were preserved, surrounded by gudai. Even Vilnius was almost completely surrounded by Slavs by the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries."

- Karjaharm 2010, pp. 32–33.

- (in Russian) Demoscope.

- ^ Łossowski 1995, p. 11, 104.

- Brensztejn 1919, pp. 8, 21.

- Romer 1920, p. 31.

- Bieliauskas 2009.

- Klimas 1991, p. 148.

- Merkys 2004, pp. 408–409.

- Bojtar 2000, p. 201.

- ^ Owsinski & Eberhardt 2003, pp. 48, 59.

- Čekmonas & Grumadienė 2017.

- ^ Garšva & Grumadienė 1993, p. 132.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-08-18. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Radczenko, Antoni (27 August 2015). "Jankowiak: Polacy na Wileńszczyźnie mówią gwarą białoruską". Kresy24.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- Kalnius, Petras (17 August 2004). "Ethnic Processes in Southeastern Lithuania in the 2nd half of the 20th c." istorija.lt. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "Первая всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г. Виленский уезд, весь".

- "Первая всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г. Виленский уезд без города".

- Stravinskienė, Vitalija. "Migracijos procesai Vilniuje: kaip ir kodėl per sovietmetį keitėsi Vilniaus gyventojų sudėtis". 15min.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- Szporluk 2000, p. 47.

- Česnavičius & Stanaitis 2010, pp. 33, 36.

- "Gyventojai gyvenamosiose vietovėse". Statistics Lithuania. 2013-01-25. Archived from the original on 2017-02-02. Retrieved 2017-02-25.

- Borzecki 2008, p. 322.

Sources

- Balkelis, Tomas (2013). "Nation State, Ethnic Conflict, and Refugees in Lithuania: 1939–1940". In Bartov, Omer; Weitz, Eric D. (eds.). Shatterzone of Empires: Coexistence and Violence in the German, Habsburg, Russian, and Ottoman Borderlands. Indiana University Press. pp. 243–257.

- Barwiński, Marek; Leśniewska, Katarzyna (2010). "Vilnius region as a historical region". Region and Regionalism. Vol. 10.

- Bieliauskas, Pranciškus (2009). Vilniaus dienoraštis. 1915-1919 (in Lithuanian). Vilnius.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Borzecki, Jerzy (2008). The Soviet-Polish Peace of 1921 and the creation of interwar Europe. Yale University Press.

- Bojtar, E. (2000). Foreword to the past: a cultural history of the Baltic people. Central European University Press.

- Brensztejn, Michał Eustachy (1919). Spisy ludności m. Wilna za okupacji niemieckiej od. 1 listopada 1915 r. (in Polish). Warsaw: Biblioteka Delegacji Rad Polskich Litwy i Białej Rusi.

- Budreckis, Algirdas (1967). "Etnografinės Lietuvos Rytinės ir Pietinės Sienos". Karys.

- Čepėnas, Pranas (1992). Naujųjų laikų Lietuvos istorija (in Lithuanian). Vol. II. Chicago: Dr. Griniaus fondas. ISBN 5-89957-012-1.

- Čekmonas, Valerijus; Grumadienė, Laima (2017). "Kalbų paplitimas Rytų Lietuvoje" [Distribution of languages in Eastern Lithuania]. Valerijus Čekmonas: kalbų kontaktai ir sociolingvistika (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Lietuvių kalbos institutas. pp. 108–114, 864–866, 965–967. ISBN 9786094112010.

- Česnavičius, Darius; Stanaitis, Saulius (2010). "Dynamics of national composition of Vilnius population in the 2nd half of the 20th century". Bulletin of Geography. Socio-economic Series. No. 13. pp. 33–44.

- Davies, Norman (2005). God's Playground: The origins to 1795. Oxford University Press.

- Garšva, Kazimieras; Grumadienė, Laima (1993). Lietuvos rytai: straipsnių rinkinys (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Valstybinis leidybos centras. ISBN 9986-09-002-4.

- Lipscomb, Glenard P.; Committee for a Free Lithuania (29 May 1958). "Extension of Remarks". Congressional Record. 104 - Appendix.

- Karjaharm, Toomas (2010). "Terminology Pertaining to Ethnic Relations as Used in Late Imperial Russia". Acta Historica Tallinnensia. Vol. 15.

- Klimas, Petras (1991). Iš mano atsiminimų (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Enciklopedijų Redakcija.

- Kiaupa, Zigmantas (2004). The History of Lithuania. Vilnius: Baltos lankos. ISBN 9955-584-87-4.

- Krajewski, Zenon (1996). Geneza i dzieje wewnętrzne Litwy Środkowej (1920-1922) [The genesis and internal history of Central Lithuania (1920-1922)] (in Polish). Lublin. ISBN 83-906321-0-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Łossowski, Piotr (1995). Konflikt polsko-litewski 1918-1920 [The Polish-Lithuanian Conflict, 1918–1920] (in Polish). Warsaw: Książka i Wiedza. ISBN 83-05-12769-9.

- Merkys, Vytautas (2004). "Tautinė Vilniaus vyskupijos gyventojų sudėtis 1867-1917". Istorijos Akiračiai (in Lithuanian).

- Ochmański, Jerzy (1981). Litewska granica etniczna na wschodzie: od epoki plemiennej do XVI wieku [Lithuanian ethnic border in the east: from the tribal era to the 16th century] (in Polish). Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań.

- Ochmański, Jerzy (1986). "The National Idea in Lithuania from the 16th to the First Half of the 19th Century: The Problem of Cultural-Linguistic Differentiation". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. Vol. X, no. 3/4.

- Owsinski, Jan; Eberhardt, Piotr (2003). Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-Century Central-Eastern Europe. M.E. Sharpe.

- Romer, Eugenjusz (1920). "Spis ludności na terenach administrowanych przez Zarząd Cywilny Ziem Wschodnich (Grudzień 1919)" [Census in the areas administered by the Civil Administration of the Eastern Territories (December 1919)]. Prace Geograficzne (in Polish). No. 7.

- Rukša, Antanas (1982). Kovos dėl Lietuvos nepriklausomybės (in Lithuanian). Vol. 3. Cleveland.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Salzmann, Stephanie (2013). Great Britain, Germany and the Soviet Union: Rapallo and After, 1922-1934. Boydell Press.

- Senn, Alfred Erich (1962). "The Formation of the Lithuanian Foreign Office, 1918-1921". Slavic Review. Vol. 21, no. 3. pp. 500–507.

- Senn, Alfred Erich (1992). Lietuvos Valstybės Atkūrimas. Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidykla.

- Szporluk, Roman (2000). Russia, Ukraine and the Breakup of the Soviet Union. Hoover Press.

- Šapoka, Adolfas (2013). Raštai (in Lithuanian). Vol. I - Vilniaus Istorija. Vilnius: Edukologija.

- Turska, Halina (1930). "Język polski na Wileńsczyzne". Wilno i Ziemia Wilenska (in Polish). Vol. I. Polska Drukarnia Nakładowa "LUX" Ludwika Chomińskiego.

- Zinkevičius, Zigmas (31 January 2014). "Lenkiškai kalbantys lietuviai" [Polish-speaking Lithuanians]. alkas.lt (in Lithuanian).

External links

- Repatriation and Resettlement of Ethnic Poles Maps of Ethnic Groups

- Lithuanian-Belarusian language boundary in the 4th decade of the 19th century Archived 2011-05-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Lithuanian-Belarusian language boundary at the beginning of the 20th century

54°30′N 25°25′E / 54.500°N 25.417°E / 54.500; 25.417

Categories: