| Revision as of 16:02, 27 February 2021 editSandyGeorgia (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, File movers, Mass message senders, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers, Template editors279,105 edits →top: merge← Previous edit | Revision as of 16:07, 27 February 2021 edit undoSandyGeorgia (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, File movers, Mass message senders, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers, Template editors279,105 edits →Society and culture: let’s get society and culture information about the “cycle” in hereNext edit → | ||

| Line 82: | Line 82: | ||

| == Society and culture == | == Society and culture == | ||

| {{Further|Menstruation|Culture and menstruation |

{{Further|Lunar effect|Menstruation|Culture and menstruation}} | ||

| Although the average length of the human menstrual cycle is similar to that of the ], in modern humans there is no relation between the two.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=F_NaW1ZcSSAC&pg=PA361|title=Vertebrate Endocrinology|date=2013|publisher=Academic Press|isbn=9780123964656|edition=5|page=361}}</ref> | |||

| Several ] exist for ] to avoid damage to clothing.<ref>{{cite web | title = Periods | url = https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/periods/ | work = U.K. National Health Service }}</ref> In some cultures, mainly in ], women are isolated during menstruation due to menstrual ]s. <ref>{{cite web|date=August 2011|title=Nepal: Emerging from menstrual quarantine|url=http://www.refworld.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/rwmain?page=publisher&publisher=IRIN&type=&coi=NPL&docid=4e3f7ae82&skip=0|work=United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)}}</ref> | Several ] exist for ] to avoid damage to clothing.<ref>{{cite web | title = Periods | url = https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/periods/ | work = U.K. National Health Service }}</ref> In some cultures, mainly in ], women are isolated during menstruation due to menstrual ]s. <ref>{{cite web|date=August 2011|title=Nepal: Emerging from menstrual quarantine|url=http://www.refworld.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/rwmain?page=publisher&publisher=IRIN&type=&coi=NPL&docid=4e3f7ae82&skip=0|work=United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)}}</ref> | ||

Revision as of 16:07, 27 February 2021

This article is about biological aspects of the ovulation cycle in humans. For health, societal and practical aspects, see menstruation. A type of ovulation cycle in humans where the endometrium is shed if pregnancy does not occur

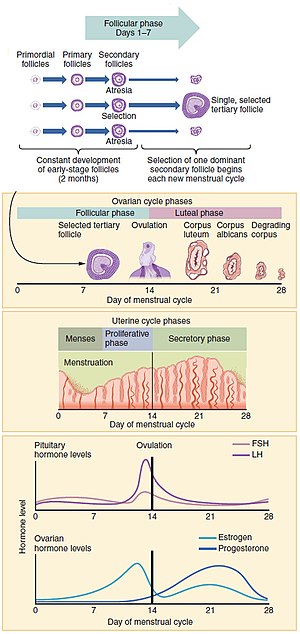

The menstrual cycle is a series of natural changes that occur in the human female reproductive system (specifically the uterus and ovaries) that makes pregnancy possible. Each cycle involves egg production and the preparation of the uterus to receive a fertilized egg. The ovarian cycle controls the production and release of eggs, and the uterine cycle governs the preparation and maintenance of the lining of the womb (uterus). These cycles occur concurrently and are coordinated over 25 to 30 days, with a median length of 28 days. The cycles are driven by naturally occurring hormones and the cyclical rise and fall of the hormone estrogen prompts the production and growth of oocytes (immature egg cells) and with the hormone progesterone, the thickening of the lining of the uterus to prepare for pregnancy.

Day one of the cycle starts on the first day of the period, and the egg is released from an ovary around day fourteen. The thickened lining of the uterus can provide nutrients to an embryo if it successfully implants. If not the lining is broken down and released. The cyclical shedding of the lining (endometrium) triggered by falling progesterone levels is called menstruation or a "period", which is a sign that pregnancy has not occurred. Each cycle can be divided into three phases based on events in the ovary (ovarian cycle) or in the uterus (uterine cycle). The ovarian cycle consists of the follicular phase, ovulation, and luteal phase whereas the uterine cycle is divided into the menstrual phase, proliferative phase, and secretory phase. The menstrual phase lasts for about the first five days of the cycle.

The cycles begin with the first period, known as menarche, between the ages of 12 and 16 years. The cycle stops after menopause which usually occurs between 45 and 55 years of age. Up to 20% of women experience problems sufficient to disrupt daily functioning as a result their menstrual cycle. These include acne, tender breasts, bloating, feeling tired, irritability and mood changes. In 20 to 30% of women, these interfere with normal life enough to cause premenstrual syndrome. In 3 to 8%, the problems are severe. The menstrual cycle can be disrupted by using hormonal birth control.

Cycles and phases

Further information: Menstruation

Measured from the first day of menstruation (menses) to the first day of menses in the next cycle, the length of a woman's menstrual cycle varies. The cycle is often less regular at the beginning and end of a woman's reproductive life. Beginning at puberty (as a child's body begins to mature into an adult body capable of sexual reproduction, the first period (called the menarche) occurs at the age of around 12–13 years. The cessation of menstrual cycles at the end of a woman's reproductive period is termed menopause, which commonly occurs between the ages of 45 and 55.

The menstrual cycle comprises the ovarian and uterine cycles. The ovarian cycle describes changes that occur in the follicles of the ovary, whereas the uterine cycle describes changes in the endometrial lining of the uterus. Both cycles can be divided into three phases. The ovarian cycle consists of alternating follicular and luteal phases, and the uterine cycle consists of menstruation, proliferative phase, and secretory phase.

Ovarian cycle

Between menarche and menopause the human ovaries regularly alternate between the luteal and follicular phases. Stimulated by gradually increasing amounts of estrogen in the follicular phase, discharges of blood (menses) flow stop, and the lining of the uterus thickens. Follicles in the ovary begin developing under the influence of a complex interplay of hormones, and after several days one or occasionally two become dominant, while non-dominant follicles shrink and die. Approximately mid-cycle, about 34–36 hours after the luteinizing hormone (LH) surges, the dominant follicle releases an oocyte, in an event called ovulation. After ovulation, the oocyte lives for 24 hours or less without fertilization while the remains of the dominant follicle in the ovary become a corpus luteum—a body with the primary function to produce large amounts of progesterone. Under the influence of progesterone, the uterine lining changes to prepare for potential implantation of an embryo to establish a pregnancy. The thickness of the endometrium continues to increase in response to mounting levels of estrogen released by the antral follicle into the blood circulation. Peak levels are reached at around day thirteen and coincides with ovulation. If implantation does not occur within approximately two weeks, the corpus luteum will involute, causing a sharp drop in levels of both progesterone and estrogen. The hormone drop causes the uterus to shed its lining in menstruation and the lowest levels of estrogen are reached around this time. The ovarian cycle lasts about 28 days, and most cycle lengths are between 25 to 30 days.

Follicular phase

Main article: Follicular phaseThe follicular phase is the first part of the ovarian cycle and is dominated by maturing follicles, and during this phase, the ovarian follicles mature and get ready to release an egg. The latter part of this phase overlaps with the proliferative phase of the uterine cycle. Through the influence of a rise in follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) during the first days of the cycle, a few ovarian follicles are stimulated. These follicles, which were present at birth and have been developing for the better part of a year in a process known as folliculogenesis, compete with each other for dominance. Under the influence of several hormones, all but one of these follicles will stop growing, while one dominant follicle in the ovary will continue to maturity. Luteinising hormone stimulates further development of the ovarian follicle. The follicle that reaches maturity is called a tertiary or antral follicle, and it contains the ovum.

Ovulation

Main article: Ovulation

Ovulation is the third phase within the larger uterine cycle and the second phase of the ovarian cycle in which a mature egg is released from the ovarian follicles into the oviduct. Ovulation only occurs in around 10% of cycles during the first two years, and by the ages of 40 to 50 the number ovarian follicles becomes depleted. Luteinising hormone initiates ovulation at around day 14 and stimulates the formation of the corpus luteum. In turn, and following further stimulation by luteinising hormone, the corpus luteum produces and releases estogens, progesterone, relaxin, (which relaxes the uterus by inhibiting contractions of the myometrium and inhibin, (which stops secretion of more luteinising hormone.

During the follicular phase, estradiol suppresses release of luteinizing hormone (LH) from the anterior pituitary gland. When the egg has nearly matured, levels of estradiol reach a threshold above which this effect is reversed and estrogen stimulates the production of a large amount of LH. This process, known as the LH surge, starts around day 12 of the average cycle and can last 48 hours.

These hormones are regulated by gonadotropin-releasing hormone(GnRH), and a surge ofGnRH has been shown to precede the LH surge, suggesting that estrogen's main effect is on the hypothalamus, which controls GnRH secretion. This can be enabled by the presence of two different estrogen receptors in the hypothalamus: estrogen receptor alpha, which is responsible for the negative feedback estradiol-LH loop, and estrogen receptor beta, which is responsible for the positive estradiol-LH relationship. However, in humans it has been shown that high levels of estradiol can provoke 32 increases in LH, even when GnRH levels and pulse frequencies are held constant,suggesting that estrogen acts directly on the pituitary to provoke the LH surge.

The release of LH matures the egg and weakens the wall of the follicle in the ovary, causing the fully developed follicle to release its secondary oocyte. If it is fertilized by a sperm, the secondary oocyte promptly matures into an ootid and then becomes a mature ovum. If it is not fertilized by a sperm, the secondary oocyte will degenerate. The mature ovum has a diameter of about 0.2 mm.

Which of the two ovaries—left or right—ovulates appears essentially random; no left and right co-ordinating process is known. Occasionally, both ovaries will release an egg; if both eggs are fertilized, the result is fraternal twins. After being released from the ovary, the egg is swept into the fallopian tube by the fimbria, which is a fringe of tissue at the end of each fallopian tube. After about a day, an unfertilized egg will disintegrate or dissolve in the fallopian tube.

Fertilization by a spermatozoon, when it occurs, usually takes place in the ampulla, the widest section of the fallopian tubes. A fertilized egg immediately begins the process of embryogenesis, or development. The developing embryo takes about three days to reach the uterus and another three days to implant into the endometrium. It has usually reached the blastocyst stage at the time of implantation.

Luteal phase

Main article: Luteal phaseThe luteal phase is the final phase of the ovarian cycle and it corresponds to the secretory phase of the uterine cycle. During the luteal phase, the pituitary hormones FSH and LH cause the remaining parts of the dominant follicle to transform into the corpus luteum, which produces progesterone. The increased progesterone in the adrenals starts to induce the production of estrogen. The hormones produced by the corpus luteum also suppress production of the FSH and LH that the corpus luteum needs to maintain itself. Consequently, the level of FSH and LH fall quickly over time, and the corpus luteum subsequently atrophies. Falling levels of progesterone trigger menstruation and the beginning of the next cycle. From the time of ovulation until progesterone withdrawal has caused menstruation to begin, the process typically takes about two weeks, with 14 days considered normal. For an individual woman, the follicular phase often varies in length from cycle to cycle; by contrast, the length of her luteal phase will be fairly consistent from cycle to cycle.

The loss of the corpus luteum is prevented by fertilization of the egg. The syncytiotrophoblast, which is the outer layer of the resulting embryo-containing structure (the blastocyst) and later also becomes the outer layer of the placenta, produces human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), which is very similar to LH and which preserves the corpus luteum. The corpus luteum can then continue to secrete progesterone to maintain the new pregnancy. Most pregnancy tests look for the presence of hCG.

The luteal phase (between ovulation and menstruation) of the menstrual cycle is about the same length in most individuals (average 14 days) whereas the follicular phase tends to show much more variability (log-normally distributed with 95% of individuals having follicular phases between 10.3 and 16.3 days). The follicular phase – during which follicles in the ovary mature from primary follicle to a fully mature antral follicle – also seems to get significantly shorter with age (geometric mean 14.2 days in women aged 18–24 vs. 10.4 days in women aged 40–44).

Uterine cycle

The uterine cycle has three phases: menses, proliferative, secretory.

Menses (menstruation)

Main article: MenstruationMenstruation (also called menstrual bleeding, menses, catamenia or a period) is the first and most evident phase of the uterine cycle and begins at puberty. Called the menarche, the first menses occurs at the age of around 12–13 years. The average age is generally later in the developing world and earlier in developed world and the median cycle length can vary from 28 to 36 days. In precocious puberty, it can occur as early as age eight years, and this can still be normal. Delayed puberty is the absence of secondary breast development by the age of 13 years.

The flow of menses normally serves as a sign that a woman has not become pregnant, but this cannot be taken as certainty, as several factors can cause bleeding during pregnancy. Menses occurs on average once a month from menarche to menopause, which corresponds with a woman's fertility. The average age of menopause in women is 52 years, and it typically occurs between 45 and 55 years of age.

Eumenorrhea denotes normal, regular menstruation that lasts for a few days (usually 3 to 5 days, but anywhere from 2 to 7 days is considered normal). The average blood loss during menstruation is 30 milliliters (mL), and more than 80 mL is considered abnormal. Women who experience menorrhagia (heavy menstrual bleeding) are more susceptible to iron deficiency than the average person. An enzyme called plasmin breaks up the blood clots in the menstrual fluid.

Proliferative phase

The proliferative phase is the second phase of the uterine cycle when estrogen causes the lining of the uterus to grow, or proliferate, during this time. As they mature, the ovarian follicles secrete increasing amounts of estradiol, an estrogen. The estrogens initiate the formation of a new layer of endometrium in the uterus, histologically identified as the proliferative endometrium. The estrogen also stimulates crypts in the cervix to produce cervical mucus, which causes vaginal discharge regardless of arousal, and can be tracked by women practicing fertility awareness.

Secretory phase

The secretory phase is the final phase of the uterine cycle and it corresponds to the luteal phase of the ovarian cycle. During the secretory phase, the corpus luteum produces progesterone, which plays a vital role in making the endometrium receptive to implantation of the blastocyst and supportive of the early pregnancy, by increasing blood flow and uterine secretions and reducing the contractility of the smooth muscle in the uterus; it also has the side effect of raising the woman's basal body temperature.

Menstrual health

Even when normal, the changes in hormone levels during the menstrual cycle can increase the incidence in women of disorders such as autoimmune diseases, which might be caused by estrogen enhancement of the immune system. Up to 20% of women experience problems sufficient to disrupt daily functioning as a result their menstrual cycle. These include acne, tender breasts, bloating, feeling tired, irritability and mood changes. In 20 to 30% of women, these interfere with normal life enough to cause premenstrual syndrome (PMS). In 3 to 8%, the problems are severe. These issues can significantly affect a woman's health and quality of life and timely interventions can improve the lives of a these women.

Painful cramping in the abdomen, back, or upper thighs can occur during the first few days of menstruation. Severe uterine pain during menstruation is known as dysmenorrhea, and it is most common among adolescents and younger women (affecting about 67.2% of adolescents). When menstruation begins, symptoms of PMS such as breast tenderness and irritability generally decrease. In some women, ovulation features a characteristic pain called mittelschmerz (a German term meaning middle pain).

Ovulation suppression and interventions

Breastfeeding women can experience complete suppression of follicular development, follicular development but no ovulation, or normal menstrual cycles can resume. Hormonal contraception affects the frequency, duration, severity, volume, and regularity of menstruation and menstrual symptoms.

Ovulation induction and controlled ovarian hyperstimulation are techniques used in assisted reproduction involving the use of fertility medications to treat anovulation and/or produce multiple ovarian follicles.

Evolution and other species

The evolution of the menstrual cycle has been driven by ovulation more than menstruation as the physiological and psychological changes that occur during the cycle increase fertility in the broadest sense. Most female mammals have an estrous cycle, yet only ten primate species, four bat species, the elephant shrew and the spiny mouse have a menstrual cycle. The lack of immediate relationship between these groups suggests that four distinct evolutionary events have caused menstruation to arise.

Society and culture

Further information: Lunar effect, Menstruation, and Culture and menstruationAlthough the average length of the human menstrual cycle is similar to that of the lunar cycle, in modern humans there is no relation between the two.

Several menstrual hygiene products exist for menstrual management to avoid damage to clothing. In some cultures, mainly in developing countries, women are isolated during menstruation due to menstrual taboos.

See also

- Menstruation (mammal) – applies to females of certain mammal species

- Ovulatory shift hypothesis

Bibliography

- Parker, Steve (2019). The concise human body book : an illustrated guide to it's structures, function and disorders. London: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0-241-39552-3. OCLC 1091644711.

- Sherwood, Lauralee (2016). Human physiology : from cells to systems. Boston, MA, USA: Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-285-86693-2. OCLC 905848832.

- Tortora, Gerard (2017). Tortora's principles of anatomy & physiology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-1-119-38292-8. OCLC 990424568.

References

- ^ Tortora 2017, p. 942.

- ^ Draper CF, Duisters K, Weger B, Chakrabarti A, Harms AC, Brennan L, Hankemeier T, Goulet L, Konz T, Martin FP, Moco S, van der Greef J (October 2018). "Menstrual cycle rhythmicity: metabolic patterns in healthy women". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 14568. Bibcode:2018NatSR...814568D. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-32647-0. PMC 6167362. PMID 30275458.

- ^ Tortora 2017, p. 944.

- Tortora 2017, p. 943.

- ^ Lacroix AE, Gondal H, Langaker MD (2020). "Physiology, Menarche". StatPearls . Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29261991.

- "Menopause: Overview". NIH. 12 January 2016.

- ^ Gudipally PR, Sharma GK (2020). Premenstrual Syndrome. StatPearls . PMID 32809533.

- ^ "Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) fact sheet". Office on Women's Health, USA. 23 December 2014. Archived from the original on 28 June 2015. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- ^ Biggs WS, Demuth RH (October 2011). "Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder". American Family Physician. 84 (8): 918–24. PMID 22010771.

- Klump KL, Keel PK, Racine SE, et al. (February 2013). "The interactive effects of estrogen and progesterone on changes in emotional eating across the menstrual cycle". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 122 (1): 131–7. doi:10.1037/a0029524. PMC 3570621. PMID 22889242.

- ^ Reed BF, Carr BR, Feingold KR, et al. (2018). "The Normal Menstrual Cycle and the Control of Ovulation". Endotext. PMID 25905282.

- ^ Papadimitriou A (December 2016). "The Evolution of the Age at Menarche from Prehistorical to Modern Times". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 29 (6): 527–530. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2015.12.002. PMID 26703478.

- Shadyab AH, Macera CA, Shaffer RA, Jain S, Gallo LC, Gass ML, Waring ME, Stefanick ML, LaCroix AZ (January 2017). "Ages at menarche and menopause and reproductive lifespan as predictors of exceptional longevity in women: the Women's Health Initiative". Menopause (New York, N.Y.). 24 (1): 35–44. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000710. PMC 5177476. PMID 27465713.

- Richards JS (2018). "The Ovarian Cycle". Vitamins and Hormones. 107: 1–25. doi:10.1016/bs.vh.2018.01.009. ISBN 9780128143599. PMID 29544627.

- ^ Sherwood 2016, p. 741.

- Sherwood 2016, p. 747.

- ^ Tortora 2017, pp. 942–46.

- Tortora 2017, p. 945.

- ^ Parker 2019, p. 283.

- Tortora 2017, p. 953.

- ^ Lentz GM, Lobo RA, Gershenson DM, Katz VL (2013). Comprehensive gynecology. St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby. ISBN 978-0-323-06986-1. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- Sherwood 2016, p. 745.

- Hu L, Gustofson RL, Feng H, Leung PK, Mores N, Krsmanovic LZ, Catt KJ (October 2008). "Converse regulatory functions of estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta subtypes expressed in hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons". Molecular Endocrinology. 22 (10): 2250–9. doi:10.1210/me.2008-0192. PMC 2582533. PMID 18701637.

- Duffy DM, Ko C, Jo M, Brannstrom M, Curry TE (April 2019). "Ovulation: Parallels With Inflammatory Processes". Endocrine Reviews. 40 (2): 369–416. doi:10.1210/er.2018-00075. PMC 6405411. PMID 30496379.

- ^ Losos JB, Raven PH, Johnson GB, Singer SR (2002). Biology. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 1207–09. ISBN 978-0-07-303120-0.

- Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, et al. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th edition. New York: Garland Science; 2002. Eggs. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26842/

- ^ Ecochard R, Gougeon A (April 2000). "Side of ovulation and cycle characteristics in normally fertile women". Human Reproduction. 15 (4): 752–5. doi:10.1093/humrep/15.4.752. PMID 10739814.

- "Multiple Pregnancy: Twins or More — Topic Overview". WebMD Medical Reference from Healthwise. 16 January 2019. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- Tortora 2017, p. 959.

- Salamonsen LA (December 2019). "Women in Reproductive Science: Understanding human endometrial function". Reproduction (Cambridge, England). 158 (6): F55 – F67. doi:10.1530/REP-18-0518. PMID 30521482.

- Alvergne A, Högqvist Tabor V (June 2018). "Is Female Health Cyclical? Evolutionary Perspectives on Menstruation". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 33 (6): 399–414. arXiv:1704.08590. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2018.03.006. PMID 29778270. S2CID 4581833.

- Ibitoye M, Choi C, Tai H, Lee G, Sommer M (2017). "Early menarche: A systematic review of its effect on sexual and reproductive health in low- and middle-income countries". PLOS ONE. 12 (6): e0178884. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1278884I. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0178884. PMC 5462398. PMID 28591132.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - "Menstruation and the menstrual cycle fact sheet". Office of Women's Health, USA. 23 December 2014. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ Sultan C, Gaspari L, Maimoun L, Kalfa N, Paris F (April 2018). "Disorders of puberty" (PDF). Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 48: 62–89. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2017.11.004. PMID 29422239.

- Breeze C (May 2016). "Early pregnancy bleeding". Australian Family Physician. 45 (5): 283–6. PMID 27166462.

- Towner MC, Nenko I, Walton SE (April 2016). "Why do women stop reproducing before menopause? A life-history approach to age at last birth". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 371 (1692): 20150147. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0147. PMC 4822427. PMID 27022074.

- ^ Goldenring JM (1 February 2019). "All About Menstruation". WebMD. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- Harvey LJ, Armah CN, Dainty JR, Foxall RJ, John Lewis D, Langford NJ, Fairweather-Tait SJ (October 2005). "Impact of menstrual blood loss and diet on iron deficiency among women in the UK". The British Journal of Nutrition. 94 (4): 557–64. doi:10.1079/BJN20051493. PMID 16197581.

- Tortora 2017, p. 600.

- Simmons RG, Jennings V (July 2020). "Fertility awareness-based methods of family planning". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 66: 68–82. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2019.12.003. PMID 32169418.

- Lombardi J (1998). Comparative Vertebrate Reproduction. Springer. p. 184. ISBN 9780792383369.

- Charkoudian N, Hart EC, Barnes JN, Joyner MJ (June 2017). "Autonomic control of body temperature and blood pressure: influences of female sex hormones" (PDF). Clinical Autonomic Research : Official Journal of the Clinical Autonomic Research Society. 27 (3): 149–155. doi:10.1007/s10286-017-0420-z. PMID 28488202. S2CID 3773043.

- Talsania M, Scofield RH (May 2017). "Menopause and Rheumatic Disease". Rheumatic Diseases Clinics of North America. 43 (2): 287–302. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2016.12.011. PMC 5385852. PMID 28390570.

- Matteson KA, Zaluski KM (September 2019). "Menstrual Health as a Part of Preventive Health Care". Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 46 (3): 441–453. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2019.04.004. PMID 31378287.

- Baker FC, Lee KA (September 2018). "Menstrual Cycle Effects on Sleep". Sleep Medicine Clinics. 13 (3): 283–294. doi:10.1016/j.jsmc.2018.04.002. PMID 30098748.

- Sharma P, Malhotra C, Taneja DK, Saha R (February 2008). "Problems related to menstruation amongst adolescent girls". Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 75 (2): 125–9. doi:10.1007/s12098-008-0018-5. PMID 18334791. S2CID 58327516.

- Carr SL, Gaffield ME, Dragoman MV, Phillips S (September 2016). "Safety of the progesterone-releasing vaginal ring (PVR) among lactating women: A systematic review". Contraception. 94 (3): 253–61. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2015.04.001. PMID 25869631.

- Tortora 2017, p. 948.

- Blumenfeld Z (2018). "The Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome". Vitamins and Hormones. 107: 423–451. doi:10.1016/bs.vh.2018.01.018. ISBN 9780128143599. PMID 29544639.

- Kiesner J, Eisenlohr-Moul T, Mendle J (July 2020). "Evolution, the Menstrual Cycle, and Theoretical Overreach". Perspectives on Psychological Science : A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science. 15 (4): 1113–1130. doi:10.1177/1745691620906440. PMC 7334061. PMID 32539582.

- Bellofiore N, Ellery SJ, Mamrot J, Walker DW, Temple-Smith P, Dickinson H (January 2017). "First evidence of a menstruating rodent: the spiny mouse (Acomys cahirinus)". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 216 (1): 40.e1–40.e11. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2016.07.041. PMID 27503621. S2CID 88779.

- Emera D, Romero R, Wagner G (January 2012). "The evolution of menstruation: a new model for genetic assimilation: explaining molecular origins of maternal responses to fetal invasiveness". BioEssays. 34 (1): 26–35. doi:10.1002/bies.201100099. PMC 3528014. PMID 22057551.

- Vertebrate Endocrinology (5 ed.). Academic Press. 2013. p. 361. ISBN 9780123964656.

- "Periods". U.K. National Health Service.

- "Nepal: Emerging from menstrual quarantine". United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). August 2011.

External links

![]() Media related to Menstrual cycle at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Menstrual cycle at Wikimedia Commons

| Menstrual cycle | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events and phases | |||||

| Life stages | |||||

| Tracking |

| ||||

| Suppression | |||||

| Disorders | |||||

| Related events | |||||

| Mental health | |||||

| Hygiene | |||||

| In culture and religion | |||||

| Reproductive health |

| ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual health |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Non-reproductive health |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Sociocultural factors |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Politics, research and advocacy |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Women's health by country |

| ||||||||||||||||