| Revision as of 12:10, 24 December 2021 editGKFX (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users13,131 editsm Remove Template:Columns: being deleted (via WP:JWB)← Previous edit | Revision as of 10:52, 23 July 2022 edit undoMiki Filigranski (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers10,356 edits new revision, for issues and else see discussion at talk pageTag: Disambiguation links addedNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Slavic goddess of rain, wife of Perun.}} | {{Short description|Slavic rainmaking rituals and goddess of rain, wife of Perun.}} | ||

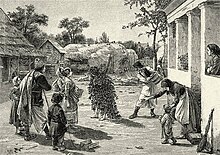

| ] (1892).]] | |||

| {{About||the town in Ethiopia|Dodola, Ethiopia}} | |||

| {{more citations needed|date=June 2008}} | |||

| ] | |||

| '''Perperuna''' (also spelled ''Peperuda'', ''Preperuda'', ''Preperuša'', ''Prporuša'', ''Papaluga'' etc.) and '''Dodola''' (also spelled ''Dodole'', ''Dudola'', ''Dudula'' etc.){{sfn|Jakobson|1955|p=616}} are Slavic ] pagan customs which were mainly preserved among ] and neighboring people until 20th century.{{sfn|Gimbutas|1967|p=743}} It is a ceremonial ritual of singing and dancing done by young boys and girls in times of ]s in honor of Slavic god ].{{sfn|Gimbutas|1967|p=743}} According to some interpretations, Perperuna/Dodola could have been a Slavic goddess of rain, and the wife of the supreme deity Perun (god of ] in the Slavic pantheon). | |||

| ] ]] | |||

| == Names == | |||

| '''Dodola''' (also spelled ''Doda'', ''Dudulya'' and ''Didilya''), also known under the names for butterfly: '''Paparuda, Peperuda, Perperuna''' or '''Preperuša''',<ref>Jakobson, Roman (1955). "While Reading Vasmer's Dictionary" In: ''WORD'', 11:4: p. 616. </ref> is a pagan tradition found in the ]. The central character of the ceremony is usually an orphan girl, less often, a boy. Wearing a skirt made of fresh green knitted vines and small branches, the girl born after the death of her father, the last girl child of the mother (if the mother subsequently gives birth to another child, great misfortunes are expected in the village), sings and dances through the streets of the village, stopping at every house, where the hosts sprinkle water on her. The ritual is associated with a particular tune to which a particular dance is performed, not only by the girl, but also by the villagers who follow her through the streets, shouting their encouragement. | |||

| {{quote box|align=left|quote=<poem><small>Περπερούνα περπατεί / Perperouna perambulates | |||

| Κή τόν θεό περικαλεί / And to God prays | |||

| Θέ μου, βρέξε μια βροχή / My God, send a rain | |||

| Μιἁ βροχή βασιλική / A right royal rain | |||

| Οσ ἀστἀχυα ς τἀ χωράΦια / That as many (as are there) ears of corn in the fields | |||

| Τόσα κούτσουρα ς τ ἁμπέλια / So many stems (may spring) on the vines</small> | |||

| </poem>|source=<br><small>Shatista near ], ], Greece, 1903<ref>{{cite book |last=Abbott |first=George Frederick |author-link=George Frederick Abbott |date=1903 |title=Macedonian Folklore |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=M7o8AAAAIAAJ |location=Cambridge |publisher=] |page=119}}</ref></small>}} The custom's Slavic prototype name is ''*Perperuna'' (with variations ''Preperuna'', ''Peperuna'', ''Preperuda/Peperuda'', ''Pepereda'', ''Preperuga/Peperuga'', ''Peperunga'', ''Pemperuga'' in ] and ]: ''Prporuša'', ''Parparuša'', ''Preporuša/Preporuča'', ''Preperuša'', ''Barburuša/Barbaruša'' in ]; ''Peperuda'', ''Papaluga'', ''Papaluda/Paparuda'', ''Babaruta'', ''Mamaruta'' in ]; ''Perperouna'', ''Perperinon'', ''Perperouga'', ''Parparouna'' in ]; ''Perperona/Perperone'', ''Rona'' in ]; ''Pirpirună'' among ]) and ''Dodola'' (including ] among previous countries, with variants ''Dodole'', ''Dudola'', ''Dudula'', ''Dudule'', ''Dudulica'', ''Doda'', ''Dodočka'', ''Dudulejka'', ''Didjulja'', ''Dordolec/Durdulec'' etc.).{{sfn|Gimbutas|1967|p=743}}{{sfn|Evans|1974|p=100}}{{sfn|Jakobson|1985|p=22–24|ps=:Mythological associations linked with the butterfly (cf. her Serbian name ''Vještica'') also explain the Bulgarian entomological names ''peperuda'', ''peperuga''}}{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=80, 93}}{{Sfn|Puchner|2009|p=346}} They can be found mainly among South Slavs, but also near nations and regions influenced by the Slavs; Albania, Greece, Hungary, Moldavia and Romania (including ] and ]).{{sfn|Gimbutas|1967|p=743}}{{sfn|Jakobson|1985|p=22, 24}}{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=93–94}}<ref>{{cite journal |last=Zaroff |first=Roman |date=1999 |title=Organized pagan cult in Kievan Rus': The invention of foreign elite or evolution of local tradition? |url=https://ojs.zrc-sazu.si/sms/article/view/1844 |journal=] |volume=2 |pages=57 |doi=10.3986/sms.v2i0.1844 |quote=As a consequence of the relatively early Christianisation of the Southern Slavs, there are no more direct accounts in relation to Perun from the Balkans. Nevertheless, as late as the first half of the 12th century, in Bulgaria and Macedonia, peasants performed a certain ceremony meant to induce rain. A central figure in the rite was a young girl called Perperuna, a name clearly related to Perun. At the same time, the association of Perperuna with rain shows conceptual similarities with the Indian god Parjanya. There was a strong Slavic penetration of Albania, Greece and Romania, between the 6th and 10th centuries. Not surprisingly the folklore of northern Greece also knows Perperuna, Albanians know Pirpirúnă, and also the Romanians have their Perperona.90 Also, in a certain Bulgarian folk riddle the word ''perušan'' is a substitute for the Bulgarian word ''гърмомеҽица'' (grmotevitsa) for thunder.91 Moreover, the name of Perun is also commonly found in Southern Slavic toponymy. There are places called: Perun, Perunac, Perunovac, Perunika, Perunićka Glava, Peruni Vrh, Perunja Ves, Peruna Dubrava, Perunuša, Perušice, Perudina and Perutovac.92}}</ref> All variants are considered to be taboo-alternations to "avoid profaning the holy name" of pagan god.{{sfn|Gimbutas|1967|p=743}}{{sfn|Evans|1974|p=116}} Perperuna is formed by reduplication of root "per-" (to beat).{{sfn|Gimbutas|1967|p=743}}{{sfn|Jakobson|1985|p=23}}<ref name="Katicic"/> Those with root "peper-", "papar-" and "pirpir-" were changed accordingly modern words for ] and ] plant,{{sfn|Gimbutas|1967|p=743}}{{Sfn|Puchner|2009|p=348}} possibly also ] and else.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Puchner |first=Walter |author-link=Walter Puchner |date=1983 |title=Бележки към ономатологията и етимологиятана българските и гръцките названия на обреда за дъжд додола/перперуна |trans-title=Notes on the Onomatology and the Etymology of Bulgarian and Greek Names for the Dodola / Perperuna Rite |url=https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=17959 |journal=Bulgarian Folklore |volume=IX |issue=1 |pages=59–65 |language=bg}}</ref>{{Sfn|Puchner|2009|p=347–349}} | |||

| == Origin == | |||

| According to some interpretations, Dodola is a Slavic goddess of rain,<ref Name="Radosavljevich">{{cite book |last=Radosavljevich |first=Paul Rankov |title=Who are the Slavs?: A Contribution to Race Psychology |publisher=The Gorham Press |year=1919 |location=Original from the University of Michigan |url=https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_NlU5AAAAMAAJ |page=}}</ref> and the wife of the supreme deity ] (god of ] in the Slavic pantheon). Slavs believed that when Dodola milks her heavenly cows, the ]s, it rains on earth. Each spring Dodola is said to fly over woods and fields, and spread vernal greenery, decorating the trees with blossoms.{{citation needed|date=January 2015}} | |||

| ] (2019).]] | |||

| The name and custom of Perperuna/Dodola is a (Balto-)Slavic heritage of Proto-Indo-European origin related to Slavic thunder-god ]. It has parallels in ritual prayers for bringing rain in times of drought dedicated to rain-thunder deity ] recorded in the '']'' and Baltic thunder-god ], ] alongside Perun of Proto-Indo-European weather-god ].{{sfn|Jakobson|1985|p=6–7, 21, 23}} The same ritual in an early medieval Russian manuscript is related to East Slavic deity ].{{sfn|Jakobson|1955|p=616}}{{sfn|Gimbutas|1967|p=743}}{{sfn|Jakobson|1985|p=23–24}} According to ], '']'' ("dožd prapruden") and ''Pskov Chronicle'' ("dožd praprudoju neiskazaemo silen") could have "East Slavic trace of Peperuda calling forth the rain", and West Slavic god ] reminds of ''Preperuga/Prepeluga'' variation and connection with Perun.{{sfn|Gimbutas|1967|p=743}}{{sfn|Jakobson|1985|p=24}} Serbo-Croatian archaic variant ''Prporuša'' and verb ''prporiti se'' ("to fight") also have parallels in Old Russian ("porъprjutъsja").{{sfn|Jakobson|1985|p=23}} The name ''Dodola'' is cognate with the Lithuanian ''Dundulis'', a word for "thunder" and another name of the Baltic thunder-god Perkūnas.{{sfn|Jakobson|1985|p=23}}{{Sfn|Puhvel|1987|p=235}} It is also distantly related to Greek ] and ].{{sfn|Evans|1974|p=127–128}}<ref>{{cite book |last=Dauksta |first=Dainis |date=2011 |chapter=From Post to Pillar – The Development and Persistence of an Arboreal Metaphor |title=New Perspectives on People and Forests |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XxB-HZlbTe0C |publisher=Springer |page=112 |isbn=9789400711501}}</ref> Bulgarian variant ''Didjulja'' is similar to alleged Polish goddess ], and Polish language also has verb ''dudnić'' ("to thunder").{{sfn|Jakobson|1985|p=22–23}} Besides the mostly considered mythological and etymological Slavic origin related to Perun,{{#tag:ref|<ref name="Katicic">{{cite book |last=Katičić |first=Radoslav |author-link=Radoslav Katičić |title=Naša stara vjera: Tragovima svetih pjesama naše pretkršćanske starine |trans-title=Our Old Faith: Tracing the Sacred Poems of Our Pre-Christian Antiquity |year=2017 |publisher=Ibis Grafika, ] |location=Zagreb |language=hr |isbn=978-953-6927-98-2 |page=105}}</ref>{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=94}}{{sfn|Gieysztor|2006|p=89, 104–106}}<ref name="Zecevic">{{cite book |last=Zečević |first=Slobodan |date=1974 |title=Elementi naše mitologije u narodnim obredima uz igru |language=sr |location=Zenica |publisher=Muzej grada Zenice |pages=125–128, 132–133}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author=Institut za književnost i umetnost (Hatidža Krnjević) |title=Rečnik književnih termina |trans-title=Dictionary of literary terms |year=1985 |publisher=Nolit |location=Beograd |language=sr |isbn=9788619006354 |page=130, 618}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Sikimić |first=Biljana |date=1996 |title=Etimologija i male folklorne forme |language=sr |location=Beograd |publisher=SANU |pages=85–86 |quote=О vezi Peruna i prporuša up. Ivanov i Toporov 1974: 113: можно думать об одновременной связи имени nеnеруна - nрnоруша как с обозначением nорошения дождя, его распыления (ср. с.-хорв. ирпошuмu (се), nрnошка и Т.Д.; чешск. pršeti, prch, prš), так и с именем Громовержца. Связъ с порошением дождя представляется тем более вероятной, что соответствующий глагол в ряде индоевропейских язЪП<ов выступает с архаическим удвоением". Za etimologiju sh. ргроrušа up. i Gavazzi 1985: 164.}}</ref>{{sfn|Belaj|2007|p=80, 112}}{{Sfn|Dragić|2007|p=80, 112}}{{Sfn|Lajoye|2015|p=114}}}} ] noted that ] thought Perperuna/Dodola were "originally identical with the Bavarian ''Wasservogel'' and the Austrian ''Pfingstkönig''" rituals,<ref name="Ralston"/> ] considering the geographical distribution considered the possibility it also has a Paleo-Balkan background,{{sfn|Belaj|2007|p=80}} and one fringe theory argues that the Slavic god Perun and Perperuna/Dodola customs are of ] origin.<ref>D. Decev, ''Die thrakischen Sprachreste'', Wien: R.M. Rohrer, 1957, pp. 144, 151</ref><ref name="Sorin">{{cite journal|author=]|title=Influenţe romane și preromane în limbile slave de sud|date=2003|url=http://egg.mnir.ro/pdf/Paliga_InflRomane.pdf|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131228002745/http://egg.mnir.ro/pdf/Paliga_InflRomane.pdf |archive-date=December 28, 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |first=Mihai |last=Dragnea |url=https://www.academia.edu/9334808 |title=The Thraco-Dacian Origin of the Paparuda/Dodola Rain-Making Ritual |journal=Brukenthalia Acta Musei |issue=4 |date=2014 |pages=18–27}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last=Ḱulavkova |first=Katica |date=2020 |title=A Poetic Ritual Invoking Rain and Well-Being: Richard Berengarten’s In a Time of Drought |url=https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/aeer/article/view/28956 |journal=Anthropology of East Europe Review |volume=37 |issue=1 |pages=19–20}}</ref> | |||

| The name ''Perperuna'' can be identified as the reduplicated feminine ] of the name of the male god ''Perun'' (''per-perun-a''), being his female consort, wife and goddess of rain ''Perperuna Dodola'', which parallels the Old Norse couple ] and the Lithuanian Perkūnas–Perkūnija.{{sfn|Jakobson|1985|p=22–23}}{{Sfn|Puhvel|1987|p=235}}{{Sfn|Jackson|2002|p=70}}<ref name="York">{{cite journal |last=York |first=Michael |author-link=Michael York (religious studies scholar) |date=1993 |title=Toward a Proto-Indo-European vocabulary of the sacred |url=https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00437956.1993.11435902 |journal=] |volume=44 |issue=2 |pages=240, 251 |doi=10.1080/00437956.1993.11435902}}</ref> Perun's battle against ] becuase of Perperuna/Dodola's kidnapping has paralles in ] saving of ] after ] carried her underground causing big drought on Earth.<ref name="York"/>{{sfn|Evans|1974|p=116–117}} Another explanation for the variations of the name ''Dodola'' is relation to the Slavic spring goddess (Dido-)],<ref name="Ralston">{{cite book |last=Shedden-Ralston |first=William Ralston |author-link=William Ralston Shedden-Ralston |date=1872 |title=The Songs of the Russian People: As Illustrative of Slavonic Mythology and Russian Social Life |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=429UAAAAcAAJ |location=London |publisher=Ellis & Green |page=227–229}}</ref> some scholars relate ''Dodole'' with pagan custom and songs of ''Lade'' (Ladarice) in ] (so-called "Ladarice Dodolske"),<ref name="Cubelic">{{cite book |last=Čubelić |first=Tvrtko |date=1990 |title=Povijest i historija usmene narodne književnosti: historijske i literaturno-teorijske osnove te genološki aspekti: analitičko-sintetički pogledi |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hb1iAAAAMAAJ |language=hr |location=Zagreb |publisher=Ante Pelivan i Danica Pelivan |page=75–76 |isbn=9788681703014}}</ref>{{Sfn|Dragić|2007|p=279, 283}}<ref name="Dragic2012">{{cite journal |last=Dragić |first=Marko |date=2012 |title=Lada i Ljeljo u folkloristici Hrvata i slavenskom kontekstu |trans-title=Lada and Ljeljo in the folklore of Croats and Slavic context |url=https://hrcak.srce.hr/136243 |language=hr |journal=Zbornik radova Filozofskog fakulteta u Splitu |volume=5 |pages=45, 53–55}}</ref> and in ]-] for the ''Preperuša'' custom was also used term ''Ladekarice''.{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=80–81}}{{sfn|Muraj|1987|p=160–161}} | |||

| ==Names== | |||

| The custom is known by the names ''Dodola'' (''dodole'', ''dudula'', ''dudulica'', ''dodolă'') and ''Perperuna'' (''peperuda'', ''peperuna'', ''peperona'', ''perperuna'', ''prporuša'', ''preporuša'', ''paparudă'', ''pirpirună''). Both names are used by the ], ], ] and northern ]. Albanians also use the name ''Rona'' and the masculine name ''Dordolec'' (''durdulec''). | |||

| == Ritual == | |||

| The name ''Perperuna'' is identified as the reduplicated feminine ] of the name of the god '']'' (''per-perun-a'').{{Sfn|Puhvel|1987|p=235}} ] suggested that it was a divinity from the local ] substratum.<ref name="Sorin">]: "Influenţe romane și preromane în limbile slave de sud" {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131228002745/http://egg.mnir.ro/pdf/Paliga_InflRomane.pdf |date=December 28, 2013 }}</ref> The name ''Dodola'' is possibly ] with the Lithuanian ''dundulis'', a word for thunder and another name of the Baltic thunder-god ].{{Sfn|Puhvel|1987|p=235}}<ref name="Sorin"/> | |||

| ] with her ecstatic dance: ''Perperuna's Dance'' by Marek Hapon (2015).]] | |||

| Perperuna and Dodola are considered very similar pagan customs with common origin,{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=75, 78, 93, 95}}<ref name="Revija">{{cite magazine |last=Vukelić |first=Deniver |date=2010 |title=Pretkršćanski prežici u hrvatskim narodnim tradicijam |trans-title=Pre-Christian belief traces in Croatian folk traditions |url=https://www.matica.hr/hr/360/PRETKR%C5%A0%C4%86ANSKI%20PRE%C5%BDICI%20U%20HRVATSKIM%20NARODNIM%20TRADICIJAMA%20/ |language=hr |magazine=] |issue=4 |publisher=] |access-date=20 July 2022}}</ref> with main difference being in the most common gender of the central character (possibly related to social hierarchy of the specific ethnic or regional group{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=85, 95}}), lyric verses, sometimes religious content, and presence or absence of a chorus.{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=84–85, 90}} They essentially belong to rituals related to ], but over time differentiated to a specific form connected with water and vegetation.{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=73, 75–76, 91}} They represent a group of rituals with a human collective going on a procession around houses and fields of a village, but with a central live character which differentiates them from other similar collective rituals in the same region and period ('']'', '']'', '']'', '']'', ''Ladarice'', those during '']'' and '']'' and so on).{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=74–75, 80}}{{Sfn|Dragić|2007|p=276}}{{Sfn|Puchner|2009|p=289, 345}} In the valley of ] in ] the Dodola were held on Thursday which was Perun's day.{{Sfn|Dragić|2007|p=291}} The core of the song always mentions a type of rain and list of regional crops.<ref>{{cite book |last=Puchner |first=Walter |author-link=Walter Puchner |date=2016 |title=Die Folklore Südosteuropas: Eine komparative Übersicht |url=https://books.google.com/books/about/Die_Folklore_S%C3%BCdosteuropas.html?id=hZpVDAAAQBAJ |language=de |publisher=Böhlau Verlag Wien |pages=65 |isbn=9783205203124}}</ref> The first written mentions and descriptions of the pagan custom are from 18th century by ] in ''Description of Moldavia'' (1714/1771, ''Papaluga''),{{Sfn|Puchner|2009|p=346}}<ref>{{cite book |last=Cantemir |first=Dimitrie |author-link=Dimitrie Cantemir |date=1771 |title=Descriptio antiqui et hodierni status Moldaviae |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2rZfAAAAcAAJ |location=Frankfurt, Leipzig |language=de |page=315–316 |quote=Im Sommer, wenn dem Getreide wegen der Dürre Gefabr bevorzustehen fcheinet, ziehen die Landleute einem kleinen Ragdchen, welches noch nicht über zehen Jahr alt ist, ein Hemde an, welches aus Blattern von Baumen und Srantern gemacht wird. Alle andere Ragdchen und stnaben vol gleiechem Alter folgen ihr, und siehen mit Tanzen und Singen durch die ganze Racharfchaft; wo sie aber hin komuien, da pflegen ihnen die alten Weiber kalt Wasser auf den Stopf zu gieffen. Das Lied, welches fie fingen, ist ohngefähr von folegendem Innbalte: "Papaluga! steige nech dem Himmel, öffne feine Thüren, fend von oben Regen ber, daß der Roggen, Weizen, Hirfe u. f. w. gut wachsen."}}</ref> then in a Greek law book from ] (1765, it invoked 62nd Cannon to stop the custom of ''Paparuda''),{{Sfn|Puchner|2009|p=346}}<ref>{{cite book |last=Puchner |first=Walter |author-link=Walter Puchner |date=2017 |chapter=2 - Byzantium High Culture without Theatre or Dramatic Literature? |title=Greek Theatre between Antiquity and Independence: A History of Reinvention from the Third Century BC to 1830 |chapter-url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/greek-theatre-between-antiquity-and-independence/byzantium/AD8A310DFF20316E196BA81890C36797 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |page=73 |isbn=9781107445024 |doi=10.1017/9781107445024.004 |quote=...in 1765, a Greek law book from Bucharest quotes the 62nd Canon of the Trullanum in order to forbid public dancing by girls in a custom well known throughout the Balkans as 'paparuda', 'perperuna' or 'dodole', a ritual processional rain dance.}}</ref> and by the Bulgarian ] ] who also noted to be related to Perun (1792, ''Peperud'').{{sfn|Belaj|2007|p=80}}<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/istoriiavokratt00spirgoog|title=История во кратце о болгарском народе славенском. Сочинися и исписа в лето 1792|last=Габровски|first=Спиридон Иеросхимонах|publisher=изд. Св. Синод на Българската Църква|year=1900|location=София|pages=}}</ref> | |||

| D. Decev compared the word "dodola" (also ''dudula'', ''dudulica'', etc.) with ] anthroponyms (]s) and toponyms (place names), such as ''Doidalsos'', ''Doidalses'', ''Dydalsos'', ''Dudis'', ''Doudoupes'', etc.<ref>D. Decev, ''Die thrakischen Sprachreste'', Wien: R.M. Rohrer, 1957, pp. 144, 151</ref> Paliga argued that based on this, the custom most likely originated from the Thracians.<ref name="Sorin"/> | |||

| South Slavs used to organise the Perperuna/Dodola ritual in times of spring and especially summer ]s, where they worshipped the god/goddess and prayed to him/her for rain (and fertility, later also asked for other field and house blessings). The central character of the ceremony of Perperuna was usually a young boy, while of Dodola usually a young girl, both aged between 10-15 years. Purity was important, and sometimes to be orphans. They would be naked, but were not anymore in latest forms of 19-20th century, wearing a skirt and dress densely made of fresh green knitted vines, leaves and flowers of '']'', '']'', '']'', '']'', ] and other deciduous shrubs and vines, small branches of '']'', ] and other. The green cover initially covered all body so that the central person figure was almost unrecognizable, but like the neccessity of direct skin contact with greenery it also greatly decreased and was very simple in modern period. They whirled and were followed by a small procession of children who walked and danced with them around the same village and fields, sometimes carrying oak or ] branches, singing the ritual prayer, stopping together at every house yard, where the hosts would sprinkle water on chosen boy/girl who would shake and thus sprinkle everyone and everything around it (example of "analogical magic"{{Sfn|Puchner|2009|p=346}}), hosts also gifted treats (bread, eggs, cheese, sausages etc., in a later period also money) to children who shared and consumed them among them and sometimes even hosts would drink wine in Perun's honor.<ref name="Ribaric">{{Cite book|last=Ribarić|first=Josip|title=O istarskim dijalektima: razmještaj južnoslavenskih dijalekata na poluotoku Istri s opisom vodičkog govora|publisher=Josip Turčinović|date=2002|location=Pazin|orig-year=1916|language=hr|isbn=953-6262-43-6|pages=84–85, 206}}</ref>{{sfn|Gimbutas|1967|p=743–744}}{{sfn|Evans|1974|p=100, 119}}{{sfn|Jakobson|1985|p=21, 23}}{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=74–77, 83–93}}{{sfn|Muraj|1987|p=158–163}}{{Sfn|Dragić|2007|p=290–293}} The chosen boy/girl was called by one of the name variants of the ritual itself, however in ] was also known as ''Prporuš'' and in ]-] as ''Prpac/Prpats'' and both regions his companions as ''Prporuše'',<ref name="Ralston"/>{{Sfn|Dragić|2007|p=291}}<ref name="Ribaric"/>{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=76, 80}} while at ] and ] in ] near Bulgarian border were called as ''dodolće'' and ''preperuđe'' with one song using both words "Duda preperuga".{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=76, 80}} | |||

| A much more likely explanation for the variations of the name Didilya is that this is a title for the spring goddess Lada/Lela that got turned into the "name" of a goddess. Ralston explains that dido, means “great” and is usually used in conjunction with the spring god Lado.<ref>Ralston. The Songs of the Russian People. p. 28</ref> | |||

| ], Bulgaria, 1950s.]] | |||

| == Ritual == | |||

| By the 20th century once common rituals almost vanished in the Balkans, although rare examples of practice can be traced until 1950-1980s and remained in folk memory. The main reason is the development of agriculture and consequently lack of practical need for existence of mystical connection and customs with nature and weather. Christian church also tried to diminish pagan beliefs and customs, resulting in "dual belief" (''dvoeverie'') in rural populations, a conscious preservation of pre-Christian beliefs and practices alongside Christianity. Into customs and songs were mixed elements from other rituals including Christianity, but they also influenced the creation of Christian songs and prayers invoking the rain which were used as a close Christian alternative (decline was reportedly faster among Catholics{{sfn|Muraj|1987|p=161}}).{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=77, 91–93}}{{sfn|Predojević|2019|p=581, 583, 589–591}} According to ] in 1937, it was an old custom that "Christians approved it, took it over and further refined it. In the old days, ''Prporuša'' were very much like a ] ritual, only later the leaders - ''Prpac'' - began to boast too much, and ''Prporuše'' seemed to be more interested in gifts than beautiful singing and prayer".<ref>{{cite book |last=Deželić Jr. |first=Velimir |date=1937 |title=Kolede: Obrađeni hrvatski godišnji običaji |trans-title=Kolede: Examined Croatian annual customs |url=https://archive.org/details/kolede_obradjeni_hrvatski_godisnji_obicaji-velimir_dezelic_sin/ |language=hr |publisher=Hrvatsko književno društvo svetog Jeronima |page=70 |quote=Ljeti, kad zategnu suše, pošle bi našim selima Prporuše moliti od Boga kišu. Posvuda su Hrvatskom išle Prporuše, a običaj je to prastar — iz pretkršćanskih vremena — ali lijep, pa ga kršćani odobrili, preuzeli i još dotjerali. U stara vremena Prporuše su bile veoma nalik nekom pobožnom obredu, tek poslije su predvodnici — Prpci— počeli suviše lakrdijati, a Prporušama ko da je više do darova, nego do lijepa pjevanja i molitve.}}</ref> Depending on region, instead of village boys and girls the pagan ritual by then was mostly done by migrating ] from other villages and for whom it became a professional performance motivated by gifts, sometimes followed by financially poor members from other ethnic groups.{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=77, 91–93}}{{sfn|Predojević|2019|p=581, 583, 589–591}}<ref name="Horvat">{{cite book |last=Horvat |first=Josip |date=1939 |title=Kultura Hrvata kroz 1000 godina |trans-title=Culture of Croats through 1000 years |url=https://archive.org/details/kultura_hrvata_kroz_1000_godina_ii.izdanje_1939-josip_horvat |language=hr |location=Zagreb |publisher=A. Velzek |pages=23–24}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Kovačević |first=Ivan |date=1985 |title=Semiologija rituala |trans-title=Semiology of ritual |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qPMXAAAAIAAJ |language=sr |location=Beograd |publisher=Prosveta |pages=79}}</ref>{{Sfn|Dragić|2007|p=278, 290}} Due to ], the association with Romani also caused repulsion, shame and ignorance among last generations of members of ethnic groups who originally performed it.{{sfn|Predojević|2019|p=583–584, 589}} Eventually it led to a dichotomy of identification with own traditional heritage, Christianity and stereotypes about Romani witchcraft.{{sfn|Predojević|2019|p=581–582, 584}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] with her ecstatic dance: ''Perperuna's Dance'' by ] ]] | |||

| ] ]] | |||

| The first written description of the custom was left by the Bulgarian ] ] in 1792.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/istoriiavokratt00spirgoog|title=История во кратце о болгарском народе славенском. Сочинися и исписа в лето 1792|last=Габровски|first=Спиридон Иеросхимонах|publisher=изд. Св. Синод на Българската Църква|year=1900|location=София|pages=}}</ref> He tells how in times of drought young boys and girls would dress one of their number in a net and a wreath of leaves in the likeness of ] or Peperud, whom Spiridon mistakenly believed to be an old Bulgarian ruler. They would then walk in procession around the houses, singing, dancing and pouring water over each other. Villagers would give them money, which they later used to buy food and drink to celebrate in ]’s honor. | |||

| ===Perperuna songs=== | |||

| South Slavs used to organise the Dodole (or Perperuna) ] in times of ], where they worshipped the goddess and prayed to her for rain. In the ritual, young women sing specific songs to Dodola, accompanying it by a dance, while covered in leaves and small branches. In Croatia Dodole is often performed by folklore groups. | |||

| ] reported in 1881 that the custom of ''Paparuga'' was already "very disbanded" in Romania.{{sfn|Nodilo|1981|p=51}} Stjepan Žiža in 1889/95 reported that the once common ritual almost vanished in Southwestern and Central-Eastern Istria, Croatia.{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=78}} ] recorded in 1896 that the custom of ''Prporuša'' also almost vanished from the North Adriatic island of ], although almost recently it was well known in all Western parts of Croatia, while in other parts as ''Dodola''.<ref name="Milcetic">{{cite journal |last=Milčetić |first=Ivan |date=1896 |title=Prporuša |journal=Zbornik za narodni život i običaje južnih Slavena |location=Belgrade |publisher=] |volume=1 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8TwSAAAAYAAJ |page=217–218 |quote=Čini mi se da je već nestalo prporuše i na otoku Krku, a bijaše još nedavno poznata svuda po zapadnim stranama hrvatskog naroda, dok je po drugim krajevima živjela dodola. Nego i za dodolu već malo gdje znadu. Tako mi piše iz Vir‐Pazara g. L. Jovović, koga sam pitao, da li još Crnogorci poznaju koledu...}}</ref> Croatian linguist Josip Ribarić recorded in 1916 that it was still alive in Southwestern Istria and ] (and related it to the 16th century migration from Dalmatia of speakers of ] dialect).<ref name="Ribaric"/> On island of Krk was also known as ''Barburuša/Barbaruša/Bambaruša'' (occurrence there is possibly related to the 15th century migration which included besides Croats also ]-] shepherds{{sfn|Zebec|2005|p=68–71, 248}}).{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=80}}{{sfn|Zebec|2005|p=71}} It was also widespread in ] (especially ] hinterland, coast and islands), ] (also known as ''Pepeluše'', ''Prepelice''{{sfn|Muraj|1987|p=161}}) and Western ] (Križevci).<ref name="Ralston"/><ref name="Revija"/><ref name="Horvat"/>{{sfn|Zebec|2005|p=71}}{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=78, 80–81}}{{Sfn|Dragić|2007|p=291–293}} It was held in Istria at least until 1950s,{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=82}} in Žumberak until 1960s,{{sfn|Muraj|1987|p=165}} while according to one account in ] on island ] the last were in late 20th century.{{Sfn|Dragić|2007|p=292}} In Serbia, Perperuna was only found in ], Southern and Eastern Serbia near Bulgarian border.{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=79}} According to ] the discrepancy in distribution between these two countries makes an idea that originally Perperuna was Croatian while Dodola was Serbian custom.{{sfn|Nodilo|1981|p=50a|ps=:Po tome, pa i po različitome imenu za stvar istu, mogao bi ko pomisliti, da su dodole, prvim postankom, čisto srpske, a prporuše hrvatske. U Bosni, zapadno od Vrbasa, zovu se čaroice. Kad bi ovo bilo hrvatski naziv za njih, onda bi prporuše bila riječ, koja k nama pregje od starih Slovenaca.}} Seemingly it was not present in Slovenia, Northern Croatia, almost all of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro (only sporadically in ]).{{sfn|Muraj|1987|p=159}} Luka Jovović from ], Montenegro reported in 1896 that in Montenegro existed some ''koleda'' custom for summer droughts, but was rare and since 1870s not practiced anymore.<ref name="Milcetic"/> | |||

| {|class="wikitable" | |||

| In folklore of ] on the holidays of ] called '']'' five most beautiful maidens are picked to portray Dodola goddesses in leaf-dresses and sing for the village till the end of the holiday. | |||

| ||Bulgaria<ref>{{cite book |last=Антонова |first=Илонка Цанова |date=2015 |title=Календарни празници и обичаи на българите |trans-title=Calendar holidays and customs of the Bulgarians |language=bg |location=Sofia |publisher=Издателство на Българската академия на науките "Проф. Марин Дринов" |pages=66–68 |isbn=978-954-322-764-8}}</ref>||Albania<ref>{{cite book|last=Pipa|first=Arshi|title=Albanian Folk Verse: Structure and Genre|publisher=O. Harrassowitz|year=1978|isbn=3878281196|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WCIHAQAAIAAJ|page=58}}</ref>||Croatia-Krk<br><small>(], 1896<ref name="Milcetic"/>)</small>||Croatia-Istria<br><small>(], 1916<ref name="Ribaric"/>)</small>||Croatia-Istria<br><small>(], 1896<ref name="Milcetic"/>/Štifanići near ], 1906/08<ref>{{cite book |last=Ribarić |first=Josip |editor=Tanja Perić-Polonijo |date=1992 |title=Narodne pjesme Ćićarije |language=hr |location=Pazin |publisher=Istarsko književno društvo "Juraj Dobrila" |page=11, 208}}</ref>)</small>||Croatia-Dalmatia<br><small>(], 1905{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=81}})</small>||Croatia-Dalmatia<br><small>(], 1867<ref name="Vuk">{{cite book |last=Karadžić |first=Vuk Stefanović |author-link=Vuk Stefanović Karadžić |date=1867 |title=Život i običaji naroda srpskoga |trans-title=Life and customs of Serbian nation |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fX0RAAAAYAAJ |language=sr |location=Vienna |publisher=A. Karacić |pages=61–66}}</ref>)</small>||Croatia-Žumberak<br><small>(Pavlanci, 1890{{sfn|Muraj|1987|p=164}})</small> | |||

| Serbian ritual chant sung by youngsters going through the village in the dry, summer months. | |||

| {| cellpadding=6 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{lang|sr|Naša dodo Boga moli,}} | |||

| | Our dodo prays to God, | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{lang|sr|Da orosi sitna kiša,}} | |||

| | To drizzle a little rain, | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{lang|sr|Oj, dodo, oj dodole!}} | |||

| | Oh, dodo, oh dodole! | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{lang|sr|Mi idemo preko sela,}} | |||

| | We're going across the village, | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{lang|sr|A kišica preko polja,}} | |||

| | And the rain across the field, | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{lang|sr|Oj, dodo, oj, dodole!}} | |||

| | Oh, dodo, oh, dodole! | |||

| |} | |||

| === Dodole in Macedonia === | |||

| The oldest record for Dodole rituals in Macedonia is the song "Oj Ljule" from ] region, recorded in 1861.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| |last = Miladinovci | |||

| |title = Зборник | |||

| |publisher = Kočo Racin | |||

| |year = 1962 | |||

| |location = Skopje | |||

| |url = http://www.gbiblsk.edu.mk/images/stories/eknigi/zbornik.pdf | |||

| |page = 462 | |||

| |url-status = dead | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20120216225647/http://www.gbiblsk.edu.mk/images/stories/eknigi/zbornik.pdf | |||

| |archive-date = 2012-02-16 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| {| cellpadding=6 style="width: 100%; max-width: 65em" | |||

| ! Macedonian | |||

| ! Transliteration | |||

| |- style="vertical-align:top; white-space:nowrap;" | |||

| | | | | ||

| <poem> | |||

| {{div col|colwidth=15em}} | |||

| <small>Letela e peperuda | |||

| Отлетала преперуга, ој љуле, ој!{{Ref label|status|note|}} | |||

| Daĭ, Bozhe, dŭzhd | |||

| Daĭ, Bozhe, dŭzhd | |||

| От орача на орача, | |||

| Ot orache na kopache | |||

| Da se rodi zhito, proso | |||

| От копача на копача, | |||

| Zhito, proso i pshenitsa | |||

| Da se ranyat siracheta | |||

| От режача на режача; | |||

| Siracheta, siromasi</small> | |||

| </poem> | |||

| Да заросит ситна роса | |||

| || | |||

| <poem> | |||

| Ситна роса берикетна | |||

| <small>Rona-rona, Peperona | |||

| Bjerë shi ndë arat tona! | |||

| И по поле и по море; | |||

| Të bëhetë thekëri | |||

| I gjatë gjer në çati | |||

| Да се родит с' берикет | |||

| Gruri gjer në perëndi | |||

| Ashtu edhe misëri!</small> | |||

| С' берикет винo-жито; | |||

| </poem> | |||

| || | |||

| Чеинците до гредите, | |||

| <poem> | |||

| <small>Prporuša hodila | |||

| Јачмените до стреите, | |||

| Službu boga molila | |||

| Dajte sira, dajte jaj | |||

| Леноите до пojacи, | |||

| Da nam bog da mladi daž | |||

| Od šenice višnji klas! | |||

| Уроите до колена; | |||

| A ti, bože vični | |||

| Smiluj se na nas!</small> | |||

| Да се ранет сиромаси. | |||

| </poem> | |||

| || | |||

| Дрвете не со осито, | |||

| <poem> | |||

| <small>Prporuše hodile | |||

| Да је ситна година; | |||

| Slavu Boga molile | |||

| I šenice bilice | |||

| Дрвете не со ошница, | |||

| Svake dobre sričice | |||

| Bog nan ga daj | |||

| Да је полна кошница; | |||

| Jedan tihi daž!</small> | |||

| </poem> | |||

| Дрвете не со јамаче, | |||

| || | |||

| <poem> | |||

| Да је тучна година. | |||

| <small>Preporuči hodili / Prporuše hodile | |||

| {{div col end}} | |||

| Iz Prepora grada / 's Prpora grada | |||

| {{refbegin}} | |||

| Kuda hodili / Da nam bog da dažda | |||

| {{note|status}}"ој љуле, ој!" is repeated in every verse | |||

| Tuda Boga molili / Crljenoga mažda | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| Da nam Bog da dažda / I šenice bilice | |||

| | | |||

| I crljenoga masta / Svake dobre sričice | |||

| {{div col|colwidth=15em}} | |||

| I šenice bilice / Šenica nan rodila | |||

| Otletala preperuga, oj ljule, oj!{{Ref label|status|note|}} | |||

| I svake dobre srećice / Dičica prohodila | |||

| Šenica narodila / Šenicu pojili | |||

| Ot oracha na oracha, | |||

| Dica nam prohodila / Dicu poženili | |||

| I šenicu pojili / Skupi, bože, oblake! | |||

| Ot kopacha na kopacha, | |||

| I dicu poženili / Struni bojžu rosicu | |||

| Skupi, Bože, oblake / Na tu svetu zemljicu! | |||

| Ot rezhacha na rezhacha; | |||

| Hiti božju kapljicu / Amen, amen, amen | |||

| Na ovu svetu zemljicu! | |||

| Da zarosit sitna rosa | |||

| Amen</small> | |||

| </poem> | |||

| Sitna rosa beriketna | |||

| || | |||

| <poem> | |||

| I po pole i po more; | |||

| <small>Prporuše hodile | |||

| Putom Boga molile | |||

| Da se rodit s' beriket | |||

| Da ni pane kišica | |||

| Da ni rodi šenica bilica | |||

| S' beriket vino-zhito; | |||

| I vinova lozica</small> | |||

| </poem> | |||

| Cheincite do gredite, | |||

| || | |||

| <poem> | |||

| Jachmenite do streite, | |||

| <small>Prporuše hodile | |||

| Terem Boga molile | |||

| Lenoite do pojasi, | |||

| Da nam dade kišicu | |||

| Da nam rodi godina | |||

| Uroite do kolena; | |||

| I šenica bjelica | |||

| I vinova lozica | |||

| Da se ranet siromasi. | |||

| I nevjesta đetića | |||

| Do prvoga božića | |||

| Drvete ne so osito, | |||

| Daruj nama, striko naša | |||

| Oku brašna, striko naša | |||

| Da je sita godina; | |||

| Bublu masla, striko naša | |||

| Runce vune, striko naša | |||

| Drvete ne so oshnica, | |||

| Jedan sirčić, striko naša | |||

| Šaku soli, striko naša | |||

| Da ja polna koshnica; | |||

| Dva, tri jajca, striko naša | |||

| Ostaj s Bogom, striko naša | |||

| Drvete ne so jamache, | |||

| Koja si nas darovala</small> | |||

| </poem> | |||

| Da je tuchna godina. | |||

| || | |||

| {{div col end}} | |||

| <poem> | |||

| {{refbegin}} | |||

| <small>Preperuša odila | |||

| {{note|status}}"oj ljule, oj!" is repeated in every verse | |||

| Za nas Boga molila | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| Daj nam Bože kišice | |||

| Na ovu našu ljetinu | |||

| Da pokvasi mladinu | |||

| Pucaj, pucaj ledeno | |||

| Škrapaj, škrapaj godino | |||

| Mi smo tebi veseli | |||

| Kano Isus Mariji | |||

| Kaj Marija Isusu | |||

| Kano mati djetetu</small> | |||

| </poem> | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| ===Dodola songs=== | |||

| The Dodola rituals in Macedonia were actively held until the 1960s.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| The oldest record for Dodole rituals in Macedonia is the song "Oj Ljule" from ] region, recorded in 1861.<ref name="Miladinovci">{{cite book|last = Miladinovci|title = Зборник|publisher = Kočo Racin|year = 1962|location = Skopje|url = http://www.gbiblsk.edu.mk/images/stories/eknigi/zbornik.pdf|page = 462|url-status = dead|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20120216225647/http://www.gbiblsk.edu.mk/images/stories/eknigi/zbornik.pdf |archive-date = 2012-02-16}}</ref> The Dodola rituals in Macedonia were actively held until the 1960s.<ref>{{cite book|last=Veličkovska|first=Rodna|title=Музичките дијалекти во македонското традиционално народно пеење : обредно пеење|trans-title=Musical dialects in the Macedonian traditional folk singing: ritual singing| publisher=Institute of folklore "Marko Cepenkov"|year=2009|location=Skopje|language=mk|page=45}}</ref> In Bulgaria the chorus was also "Oj Ljule".{{sfn|Nodilo|1981|p=50b}} The oldest record in Serbia was by ] (1841),{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=79}} where was widespread all over the country and held at least until 1950/70s.<ref name="Zecevic"/>{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=77–78, 86, 88}} In Croatia was found in Eastern Slavonia, Southern ] and Southeastern ].<ref name="Horvat"/>{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=77–78, 90}}{{sfn|Muraj|1987|p=159}}{{sfn|Dragić|2012|p=54}}<ref>{{cite book |last=Janković |first=Slavko |date=1956 |title=Kuhačeva zbirka narodnih popijevaka (analizirana): od br. 1801 do br. 2000 |url=https://repozitorij.dief.eu/a/?pr=i&id=69581 |quote=Naša doda moli Boga (], Slavonia, 1881, sken ID: IEF_RKP_N0096_0_155; IEF_RKP_N0096_0_156A) - Ide doda preko sela (], Srijem, 1885, sken ID: IEF_RKP_N0096_0_163; IEF_RKP_N0096_0_164A) - Filip i Jakob, Koleda na kišu (], Srijem, 1886, sken ID: IEF_RKP_N0096_0_165; IEF_RKP_N0096_0_166A)}}</ref> ] in his writing about the travel to Okić-grad near ], Croatia mentioned that saw two dodole.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.knjizevnost.hr/zagrebulje-1866-august-senoa/ |title=Zagrebulje I (1866.) |last=Šenoa |first=August |author-link=August Šenoa |date=1866 |website=Književnost.hr |publisher=informativka d.o.o. |access-date=23 July 2022 |quote=...već se miču niz Okić put naše šljive dvije u zeleno zavite dodole. S ovoga dodolskoga dualizma sjetih se odmah kakvi zecevi u tom grmu idu, i moja me nada ne prevari. Eto ti pred nas dva naša junaka, ne kao dodole, kao bradurina i trbušina, već kao pravi pravcati bogovi – kao Bako i Gambrinus... Naša dva boga, u zeleno zavita, podijeliše društvu svoj blagoslov, te bjehu sa živim usklikom primljeni. No i ova mitologička šala i mrcvarenje božanske poezije po našem generalkvartirmeštru pobudi bogove na osvetu; nad našim glavama zgrnuše se oblaci, i naskoro udari kiša.}}</ref> To them is related the custom of Lade/Ladarice from other parts of Croatia, having chorus "''Oj Lado, oj!''" and similar verses "''Molimo se višnjem Bogu/Da popuhne tihi vjetar, Da udari rodna kiša/Da porosi naša polja, I travicu mekušicu/Da nam stada Lado, Ugoje se naša stada''".<ref name="Cubelic"/>{{Sfn|Dragić|2007|p=279, 283}}<ref name="Dragic2012"/> | |||

| | last = Veličkovska | |||

| | first = Rodna | |||

| | title = Музичките дијалекти во македонското традиционално народно пеење : обредно пеење | |||

| |trans-title=Musical dialects in the Macedonian traditional folk singing : ritual singing | |||

| | publisher = Institute of folklore "Marko Cepenkov" | |||

| | year = 2009 | |||

| | location = Skopje | |||

| | language = mk | |||

| | page =45 }}</ref> | |||

| {|class="wikitable" | |||

| '''Bulgarian''' traditional ''Peperuda'' song with literal translation; | |||

| ||Macedonia<ref name="Miladinovci"/>||Serbia<ref name="Vuk"/>{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=88}}||Serbia<ref name="Vuk"/>||Serbia<ref name="Vuk"/>||Croatia-Slavonia<br><small>(]<ref name="Dragic2012"/>)</small>||Croatia-Slavonia<br><small>(Đakovo, 1957{{sfn|Čulinović-Konstantinović|1963|p=77, 90}})</small>||Croatia-Srijem<br><small>(], 1979<ref>{{cite journal |last=Černelić |first=Milana |date=1998 |title=Kroz godinu dana srijemskih običaja vukovarskog kraja |trans-title=Annual customs of Srijem in the Vukovar region |url=https://hrcak.srce.hr/80816 |language=hr |journal=Etnološka tribina |volume=28 |issue=21 |pages=135}}</ref>)</small> | |||

| {| cellpadding=6 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | | |||

| | Летела е пеперуда, | |||

| <poem> | |||

| | A butterfly flew, | |||

| <small>Otletala preperuga, oj ljule, oj! | |||

| |- | |||

| Ot oracha na oracha, oj ljule, oj! | |||

| | дай, Боже, дъжд, (2) | |||

| Ot kopacha na kopacha, oj ljule, oj! | |||

| | give, God, rain, (2) | |||

| Ot rezhacha na rezhacha; oj ljule, oj! | |||

| |- | |||

| Da zarosit sitna rosa, oj ljule, oj! | |||

| | от ораче на копаче, | |||

| Sitna rosa beriketna, oj ljule, oj! | |||

| | from plowman to digger, | |||

| I po pole i po more; oj ljule, oj! | |||

| |- | |||

| Da se rodit s' beriket, oj ljule, oj! | |||

| | да се роди жито, просо, | |||

| S' beriket vino-zhito; oj ljule, oj! | |||

| | to give birth to wheat, millet | |||

| Cheincite do gredite, oj ljule, oj! | |||

| |- | |||

| Jachmenite do streite, oj ljule, oj! | |||

| | жито, просо и пшеница, | |||

| Lenoite do pojasi, oj ljule, oj! | |||

| | wheat, millet and wheat | |||

| Uroite do kolena; oj ljule, oj! | |||

| |- | |||

| Da se ranet siromasi, oj ljule, oj! | |||

| | да се ранят сирачета, | |||

| Drvete ne so osito, oj ljule, oj! | |||

| | to feed orphans, | |||

| Da je sita godina; oj ljule, oj! | |||

| |- | |||

| Drvete ne so oshnica, oj ljule, oj! | |||

| | сирачета, сиромаси. | |||

| Da ja polna koshnica; oj ljule, oj! | |||

| | orphans, the poor. | |||

| Drvete ne so jamache, oj ljule, oj! | |||

| Da je tuchna godina, oj ljule, oj!</small> | |||

| </poem> | |||

| || | |||

| <poem> | |||

| <small>Mi idemo preko sela, | |||

| Oj dodo, oj dodo le! | |||

| A oblaci preko neba, | |||

| Oj dodo, oj dodo le! | |||

| A mi brže, oblak brže, | |||

| Oj dodo, oj dodo le! | |||

| Oblaci nas pretekoše, | |||

| Oj dodo, oj dodo le! | |||

| Žito, vino porosiše, | |||

| Oj dodo, oj dodo le!</small> | |||

| </poem> | |||

| || | |||

| <poem> | |||

| <small>Molimo se višnjem Bogu, | |||

| Oj dodo, oj dodo le! | |||

| Da udari rosna kiša, | |||

| Oj dodo, oj dodo le! | |||

| Da porosi naša polja, | |||

| Oj dodo, oj dodo le! | |||

| I šenicu ozimicu, | |||

| Oj dodo, oj dodo le! | |||

| I dva pera kukuruza, | |||

| Oj dodo, oj dodo le!</small> | |||

| </poem> | |||

| || | |||

| <poem> | |||

| <small>Naša doda Boga moli, | |||

| Oj dodo, oj dodo le! | |||

| Da udari rosna kiša, | |||

| Oj dodo, oj dodo le! | |||

| Da pokisnu svi orači, | |||

| Oj dodo, oj dodo le! | |||

| Svi orači i kopači, | |||

| Oj dodo, oj dodo le! | |||

| I po kući poslovači, | |||

| Oj dodo, oj dodo le!</small> | |||

| </poem> | |||

| || | |||

| <poem> | |||

| <small>Naša doda moli Boga | |||

| Oj dodole, moj božole! | |||

| Da porosi rosna kiša | |||

| Oj dodole, moj božole! | |||

| Da pokvasi naša polja | |||

| Oj dodole, moj božole! | |||

| Da urode, da prerode | |||

| Oj dodole, moj božole!</small> | |||

| </poem> | |||

| || | |||

| <poem> | |||

| <small>Naša dojda moli boga da kiša pada | |||

| Da pokisne suvo polje, oj, dojdole! | |||

| Da pokisnu svi orači | |||

| Svi orači i kopači, oj, dojdole! | |||

| I po kući poslovači | |||

| Oj, dojdole, oj, dojdole! | |||

| I dva pera kukuruza | |||

| I lanovi za darove, oj, dojdole! | |||

| Da urodi, da prerodi, da ne polegne | |||

| Oj, dojdole, oj, dojdole!</small> | |||

| </poem> | |||

| || | |||

| <poem> | |||

| <small>Naša doda moli Boga | |||

| Da nam Bog da rosne kiše | |||

| Rosne kiše malo više | |||

| Na orače i kopače | |||

| I na naše suve bašće | |||

| Oj dodo, oj dodole! | |||

| Da trava raste | |||

| Da paun pase | |||

| Da sunce sija | |||

| Da žito zrija | |||

| Oj dodo, oj dodole!</small> | |||

| </poem> | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

| {{commons category|Dodola}} | {{commons category|Dodola}} | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| == References == | == References == | ||

| Line 206: | Line 255: | ||

| === Bibliography === | === Bibliography === | ||

| *{{cite book |last=Belaj |first=Vitomir |author-link=Vitomir Belaj |date=2007 |orig-year=1998 |title=Hod kroz godinu: Mitska pozadina hrvatskih narodnih običaja i vjerovanja |trans-title=The walk within a year: the mythic background of the Croatian folk customs and beliefs |language=hr |location=Zagreb |publisher=Golden marketing-Tehnička knjiga |isbn=978-953-212-334-0}} | |||

| *{{cite journal |last=Čulinović-Konstantinović |first=Vesna |date=1963 |title=Dodole i prporuše: narodni običaji za prizivanje kiše |trans-title=Dodole and prporuše: folk customs for invoking the rain |url=https://hrcak.srce.hr/34409 |language=hr |journal=Narodna umjetnost |volume=2 |issue=1 |pages=73–95}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last1=Puhvel|first1=Jaan|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OMPagyYOe8gC|title=Comparative Mythology|date=1987|publisher=Johns Hopkins University Press|isbn=978-0-8018-3938-2|author-link=Jaan Puhvel}} | |||

| *{{cite journal |last=Dragić |first=Marko |date=2007 |title=Ladarice, kraljice i dodole u hrvatskoj tradicijskoj kulturi i slavenskom kontekstu |trans-title=Ladarice, Queens and Dodole in Croatian Traditionary Culture and Slavic Context |url=https://www.bib.irb.hr/299913 |language=hr |journal=Hercegovina, godišnjak za kulturno i povijesno naslijeđe |volume=21 |pages=275–296}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Gieysztor |first=Aleksander |author-link=Aleksander Gieysztor |date=2006 |orig-year=1982 |edition=II |title=Mitologia Slowian |publisher=Wydawn. Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego |location=Warszawa |language=pl |isbn=9788323502340}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Gimbutas |first=Marija |author-link=Marija Gimbutas |date=1967 |chapter=Ancient Slavic Religion: A Synopsis |title=To honor Roman Jakobson: essays on the occasion of his seventieth birthday, 11 October 1966 (Vol. I) |pages=738–759 |publisher=Mouton |doi=10.1515/9783111604763-064 |isbn=9783111229584}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Evans |first=David |date=1974 |chapter=Dodona, Dodola, and Daedala |title=Myth in Indo-European Antiquity |pages=99–130 |publisher=University of California Press |isbn=9780520023789}} | |||

| *{{cite journal|last=Jackson|first=Peter|date=2002|title=Light from Distant Asterisks. Towards a Description of the Indo-European Religious Heritage|journal=Numen|volume=49|issue=1|pages=61–102|issn=0029-5973|jstor=3270472|doi=10.1163/15685270252772777}} | |||

| *{{cite journal |last1=Jakobson |first1=Roman |author-link=Roman Jakobson |date=1955 |title=While Reading Vasmer's Dictionary |url=https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00437956.1955.11659581 |journal=] |volume=11 |issue=4 |pages=611–617 |doi=10.1080/00437956.1955.11659581}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Jakobson |first=Roman |author-link=Roman Jakobson |date=1985 |title=Selected Writings VII: Contributions to Comparative Mythology |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=db7iuvTX1bkC |publisher=] |isbn=9783110106176}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Lajoye |first=Patrice |author-link=Patrice Lajoye |date=2015 |title=Perun, dieu slave de l'orage: Archéologie, histoire, folklore |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=o5LdCgAAQBAJ |language=fr |publisher=Lingva |isbn=9791094441251}} | |||

| *{{cite journal |last=Muraj |first=Aleksandra |date=1987 |title=Iz istraživanja Žumberka (preperuše, preslice, tara) |trans-title=From Research on Žumberak (preperuše, spindles, tara) |url=https://hrcak.srce.hr/clanak/76272 |language=hr |journal=Narodna umjetnost |volume=24 |issue=1 |pages=157–175}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Nodilo |first=Natko |author-link=Natko Nodilo |date=1981 |orig-year=1884 |title=Stara Vjera Srba i Hrvata |trans-title=Old Faith of Serbs and Croats |url=https://archive.org/details/StaraVjeraSrbaIHrvata/ |language=hr |location=Split |publisher=Logos}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Predojević |first=Željko |date=2019 |chapter=O pučkim postupcima i vjerovanjima za prizivanje kiše iz južne Baranje u kontekstu dvovjerja |trans-chapter=On folk practices and beliefs for invoking rain from southern Baranja in the context of dual belif |chapter-url=https://www.bib.irb.hr/1100049 |title=XIV. međunarodni kroatistički znanstveni skup |editor=] |location=Pečuh |publisher=Znanstveni zavod Hrvata u Mađarskoj |language=hr |pages=581–593 |isbn=978-963-89731-5-3}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Puchner |first=Walter |author-link=Walter Puchner |date=2009 |title=Studien zur Volkskunde Südosteuropas und des mediterranen Raums |url=https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/34402 |location=Wien, Köln, Weimar |publisher=Böhlau Verlag |language=de |isbn=978-3-205-78369-5}} | |||

| *{{cite book|last1=Puhvel|first1=Jaan|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OMPagyYOe8gC|title=Comparative Mythology|date=1987|publisher=Johns Hopkins University Press|isbn=978-0-8018-3938-2|author-link=Jaan Puhvel}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Zebec |first=Tvrtko |date=2005 |title=Krčki tanci: plesno-etnološka studija |trans-title=Tanac dances on the island of Krk: dance ethnology study |url=https://www.academia.edu/35914079/ |location=Zagreb, Rijeka |publisher=Institut za etnologiju i folkloristiku, Adamić |language=hr |isbn=953-219-223-9}} | |||

| === Further reading === | === Further reading === | ||

| * |

*{{cite book |last=Beza |first=Marcu |author-link=Marcu Beza |date=1928 |chapter=The Paparude and Kalojan |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=m2jTDwAAQBAJ |title=Paganism in Roumanian Folklore |location=London |publisher=J.M.Dent & Sons LTD. |pages=27–36}} | ||

| *{{cite book |last=Schneeweis |first=Edmund |date=2019 |orig-year=1961 |title=Serbokroatische Volkskunde: Volksglaube und Volksbrauch |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bR6bDwAAQBAJ |publisher=Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG |pages=161–163 |language=de |isbn=9783111337647}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=MacDermott |first=Mercia |author-link=Mercia MacDermott |date=2003 |title=Explore Green Men |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vT1NAAAAYAAJ |publisher=Heart of Albion Press |pages=17–19 |isbn=9781872883663}} | |||

| *{{citation |title=Dodole |url=https://www.enciklopedija.hr/natuknica.aspx?ID=15709 |author=Croatian Encyclopaedia |author-link=Croatian Encyclopaedia |year=2021}} | |||

| ===External links=== | ===External links=== | ||

| *{{YouTube|id=X0BgBEtnK4s|title=Dodole ritual in Macedonia}} | *{{YouTube|id=X0BgBEtnK4s|title=Dodole ritual on TV in Macedonia}} | ||

| *{{YouTube|id=aeCQgFUsIKA|title=Reconstruction of Dodole ritual in Bulgaria}} at ] | |||

| *{{YouTube|id=n2Vhk_eiwkg|title="Dodole" song by Croatian ethno-folk rock band Kries}} | |||

| {{Slavic mythology}} | {{Slavic mythology}} | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Line 225: | Line 297: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

Revision as of 10:52, 23 July 2022

Slavic rainmaking rituals and goddess of rain, wife of Perun.

Perperuna (also spelled Peperuda, Preperuda, Preperuša, Prporuša, Papaluga etc.) and Dodola (also spelled Dodole, Dudola, Dudula etc.) are Slavic rainmaking pagan customs which were mainly preserved among South Slavs and neighboring people until 20th century. It is a ceremonial ritual of singing and dancing done by young boys and girls in times of droughts in honor of Slavic god Perun. According to some interpretations, Perperuna/Dodola could have been a Slavic goddess of rain, and the wife of the supreme deity Perun (god of thunder in the Slavic pantheon).

Names

Περπερούνα περπατεί / Perperouna perambulates

Κή τόν θεό περικαλεί / And to God prays

Θέ μου, βρέξε μια βροχή / My God, send a rain

Μιἁ βροχή βασιλική / A right royal rain

Οσ ἀστἀχυα ς τἀ χωράΦια / That as many (as are there) ears of corn in the fields

Τόσα κούτσουρα ς τ ἁμπέλια / So many stems (may spring) on the vines

Shatista near Siatista, Western Macedonia, Greece, 1903

The custom's Slavic prototype name is *Perperuna (with variations Preperuna, Peperuna, Preperuda/Peperuda, Pepereda, Preperuga/Peperuga, Peperunga, Pemperuga in Bulgaria and Macedonia: Prporuša, Parparuša, Preporuša/Preporuča, Preperuša, Barburuša/Barbaruša in Croatia; Peperuda, Papaluga, Papaluda/Paparuda, Babaruta, Mamaruta in Romania; Perperouna, Perperinon, Perperouga, Parparouna in Greece; Perperona/Perperone, Rona in Albania; Pirpirună among Aromanians) and Dodola (including Serbia among previous countries, with variants Dodole, Dudola, Dudula, Dudule, Dudulica, Doda, Dodočka, Dudulejka, Didjulja, Dordolec/Durdulec etc.). They can be found mainly among South Slavs, but also near nations and regions influenced by the Slavs; Albania, Greece, Hungary, Moldavia and Romania (including Bukovina and Bessarabia). All variants are considered to be taboo-alternations to "avoid profaning the holy name" of pagan god. Perperuna is formed by reduplication of root "per-" (to beat). Those with root "peper-", "papar-" and "pirpir-" were changed accordingly modern words for pepper-tree and poppy plant, possibly also perper and else.

Origin

The name and custom of Perperuna/Dodola is a (Balto-)Slavic heritage of Proto-Indo-European origin related to Slavic thunder-god Perun. It has parallels in ritual prayers for bringing rain in times of drought dedicated to rain-thunder deity Parjanya recorded in the Vedas and Baltic thunder-god Perkūnas, cognates alongside Perun of Proto-Indo-European weather-god Perkwunos. The same ritual in an early medieval Russian manuscript is related to East Slavic deity Pereplut. According to Roman Jakobson, Novgorod Chronicle ("dožd prapruden") and Pskov Chronicle ("dožd praprudoju neiskazaemo silen") could have "East Slavic trace of Peperuda calling forth the rain", and West Slavic god Pripegala reminds of Preperuga/Prepeluga variation and connection with Perun. Serbo-Croatian archaic variant Prporuša and verb prporiti se ("to fight") also have parallels in Old Russian ("porъprjutъsja"). The name Dodola is cognate with the Lithuanian Dundulis, a word for "thunder" and another name of the Baltic thunder-god Perkūnas. It is also distantly related to Greek Dodona and Daedala. Bulgarian variant Didjulja is similar to alleged Polish goddess Dzidzilela, and Polish language also has verb dudnić ("to thunder"). Besides the mostly considered mythological and etymological Slavic origin related to Perun, William Shedden-Ralston noted that Jacob Grimm thought Perperuna/Dodola were "originally identical with the Bavarian Wasservogel and the Austrian Pfingstkönig" rituals, Vitomir Belaj considering the geographical distribution considered the possibility it also has a Paleo-Balkan background, and one fringe theory argues that the Slavic god Perun and Perperuna/Dodola customs are of Thracian origin.

The name Perperuna can be identified as the reduplicated feminine derivative of the name of the male god Perun (per-perun-a), being his female consort, wife and goddess of rain Perperuna Dodola, which parallels the Old Norse couple Fjörgyn–Fjörgynn and the Lithuanian Perkūnas–Perkūnija. Perun's battle against Veles becuase of Perperuna/Dodola's kidnapping has paralles in Zeus saving of Persephone after Hades carried her underground causing big drought on Earth. Another explanation for the variations of the name Dodola is relation to the Slavic spring goddess (Dido-)Lada/Lado/Lela, some scholars relate Dodole with pagan custom and songs of Lade (Ladarice) in Hrvatsko Zagorje (so-called "Ladarice Dodolske"), and in Žumberak-Križevci for the Preperuša custom was also used term Ladekarice.

Ritual

Perperuna and Dodola are considered very similar pagan customs with common origin, with main difference being in the most common gender of the central character (possibly related to social hierarchy of the specific ethnic or regional group), lyric verses, sometimes religious content, and presence or absence of a chorus. They essentially belong to rituals related to fertility, but over time differentiated to a specific form connected with water and vegetation. They represent a group of rituals with a human collective going on a procession around houses and fields of a village, but with a central live character which differentiates them from other similar collective rituals in the same region and period (Krstonoše, Poklade, Kolade, German, Ladarice, those during Jurjevo and Ivandan and so on). In the valley of Skopje in North Macedonia the Dodola were held on Thursday which was Perun's day. The core of the song always mentions a type of rain and list of regional crops. The first written mentions and descriptions of the pagan custom are from 18th century by Dimitrie Cantemir in Description of Moldavia (1714/1771, Papaluga), then in a Greek law book from Bucharest (1765, it invoked 62nd Cannon to stop the custom of Paparuda), and by the Bulgarian hieromonk Spiridon Gabrovski who also noted to be related to Perun (1792, Peperud).

South Slavs used to organise the Perperuna/Dodola ritual in times of spring and especially summer droughts, where they worshipped the god/goddess and prayed to him/her for rain (and fertility, later also asked for other field and house blessings). The central character of the ceremony of Perperuna was usually a young boy, while of Dodola usually a young girl, both aged between 10-15 years. Purity was important, and sometimes to be orphans. They would be naked, but were not anymore in latest forms of 19-20th century, wearing a skirt and dress densely made of fresh green knitted vines, leaves and flowers of Sambucus nigra, Sambucus ebulus, Clematis flammula, Clematis vitalba, fern and other deciduous shrubs and vines, small branches of Tilia, Oak and other. The green cover initially covered all body so that the central person figure was almost unrecognizable, but like the neccessity of direct skin contact with greenery it also greatly decreased and was very simple in modern period. They whirled and were followed by a small procession of children who walked and danced with them around the same village and fields, sometimes carrying oak or beech branches, singing the ritual prayer, stopping together at every house yard, where the hosts would sprinkle water on chosen boy/girl who would shake and thus sprinkle everyone and everything around it (example of "analogical magic"), hosts also gifted treats (bread, eggs, cheese, sausages etc., in a later period also money) to children who shared and consumed them among them and sometimes even hosts would drink wine in Perun's honor. The chosen boy/girl was called by one of the name variants of the ritual itself, however in Istria was also known as Prporuš and in Dalmatia-Boka Kotorska as Prpac/Prpats and both regions his companions as Prporuše, while at Pirot and Nišava District in Southern Serbia near Bulgarian border were called as dodolće and preperuđe with one song using both words "Duda preperuga".

By the 20th century once common rituals almost vanished in the Balkans, although rare examples of practice can be traced until 1950-1980s and remained in folk memory. The main reason is the development of agriculture and consequently lack of practical need for existence of mystical connection and customs with nature and weather. Christian church also tried to diminish pagan beliefs and customs, resulting in "dual belief" (dvoeverie) in rural populations, a conscious preservation of pre-Christian beliefs and practices alongside Christianity. Into customs and songs were mixed elements from other rituals including Christianity, but they also influenced the creation of Christian songs and prayers invoking the rain which were used as a close Christian alternative (decline was reportedly faster among Catholics). According to Velimir Deželić Jr. in 1937, it was an old custom that "Christians approved it, took it over and further refined it. In the old days, Prporuša were very much like a pious ritual, only later the leaders - Prpac - began to boast too much, and Prporuše seemed to be more interested in gifts than beautiful singing and prayer". Depending on region, instead of village boys and girls the pagan ritual by then was mostly done by migrating Romani people from other villages and for whom it became a professional performance motivated by gifts, sometimes followed by financially poor members from other ethnic groups. Due to Anti-Romani sentiment, the association with Romani also caused repulsion, shame and ignorance among last generations of members of ethnic groups who originally performed it. Eventually it led to a dichotomy of identification with own traditional heritage, Christianity and stereotypes about Romani witchcraft.

Perperuna songs

Ioan Slavici reported in 1881 that the custom of Paparuga was already "very disbanded" in Romania. Stjepan Žiža in 1889/95 reported that the once common ritual almost vanished in Southwestern and Central-Eastern Istria, Croatia. Ivan Milčetić recorded in 1896 that the custom of Prporuša also almost vanished from the North Adriatic island of Krk, although almost recently it was well known in all Western parts of Croatia, while in other parts as Dodola. Croatian linguist Josip Ribarić recorded in 1916 that it was still alive in Southwestern Istria and Ćićarija (and related it to the 16th century migration from Dalmatia of speakers of Southwestern Istrian dialect). On island of Krk was also known as Barburuša/Barbaruša/Bambaruša (occurrence there is possibly related to the 15th century migration which included besides Croats also Vlach-Istro-Romanian shepherds). It was also widespread in Dalmatia (especially Zadar hinterland, coast and islands), Žumberak (also known as Pepeluše, Prepelice) and Western Slavonia (Križevci). It was held in Istria at least until 1950s, in Žumberak until 1960s, while according to one account in Jezera on island Murter the last were in late 20th century. In Serbia, Perperuna was only found in Kosovo, Southern and Eastern Serbia near Bulgarian border. According to Natko Nodilo the discrepancy in distribution between these two countries makes an idea that originally Perperuna was Croatian while Dodola was Serbian custom. Seemingly it was not present in Slovenia, Northern Croatia, almost all of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro (only sporadically in Boka Kotorska). Luka Jovović from Virpazar, Montenegro reported in 1896 that in Montenegro existed some koleda custom for summer droughts, but was rare and since 1870s not practiced anymore.

| Bulgaria | Albania | Croatia-Krk (Dubašnica, 1896) |

Croatia-Istria (Vodice, 1916) |

Croatia-Istria (Čepić, 1896/Štifanići near Baderna, 1906/08) |

Croatia-Dalmatia (Ražanac, 1905) |

Croatia-Dalmatia (Ravni Kotari, 1867) |

Croatia-Žumberak (Pavlanci, 1890) |

|

Letela e peperuda |

Rona-rona, Peperona |

Prporuša hodila |

Prporuše hodile |

Preporuči hodili / Prporuše hodile |

Prporuše hodile |

Prporuše hodile |

Preperuša odila |

Dodola songs

The oldest record for Dodole rituals in Macedonia is the song "Oj Ljule" from Struga region, recorded in 1861. The Dodola rituals in Macedonia were actively held until the 1960s. In Bulgaria the chorus was also "Oj Ljule". The oldest record in Serbia was by Vuk Karadžić (1841), where was widespread all over the country and held at least until 1950/70s. In Croatia was found in Eastern Slavonia, Southern Baranja and Southeastern Srijem. August Šenoa in his writing about the travel to Okić-grad near Samobor, Croatia mentioned that saw two dodole. To them is related the custom of Lade/Ladarice from other parts of Croatia, having chorus "Oj Lado, oj!" and similar verses "Molimo se višnjem Bogu/Da popuhne tihi vjetar, Da udari rodna kiša/Da porosi naša polja, I travicu mekušicu/Da nam stada Lado, Ugoje se naša stada".

| Macedonia | Serbia | Serbia | Serbia | Croatia-Slavonia (Đakovo) |

Croatia-Slavonia (Đakovo, 1957) |

Croatia-Srijem (Tovarnik, 1979) |

|

Otletala preperuga, oj ljule, oj! |

Mi idemo preko sela, |

Molimo se višnjem Bogu, |

Naša doda Boga moli, |

Naša doda moli Boga |

Naša dojda moli boga da kiša pada |

Naša doda moli Boga |

See also

References

- ^ Jakobson 1955, p. 616.

- ^ Gimbutas 1967, p. 743.

- Abbott, George Frederick (1903). Macedonian Folklore. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 119.

- Evans 1974, p. 100.

- Jakobson 1985, p. 22–24:Mythological associations linked with the butterfly (cf. her Serbian name Vještica) also explain the Bulgarian entomological names peperuda, peperuga

- Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 80, 93.

- ^ Puchner 2009, p. 346.

- Jakobson 1985, p. 22, 24.

- Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 93–94.

- Zaroff, Roman (1999). "Organized pagan cult in Kievan Rus': The invention of foreign elite or evolution of local tradition?". Studia mythologica Slavica. 2: 57. doi:10.3986/sms.v2i0.1844.

As a consequence of the relatively early Christianisation of the Southern Slavs, there are no more direct accounts in relation to Perun from the Balkans. Nevertheless, as late as the first half of the 12th century, in Bulgaria and Macedonia, peasants performed a certain ceremony meant to induce rain. A central figure in the rite was a young girl called Perperuna, a name clearly related to Perun. At the same time, the association of Perperuna with rain shows conceptual similarities with the Indian god Parjanya. There was a strong Slavic penetration of Albania, Greece and Romania, between the 6th and 10th centuries. Not surprisingly the folklore of northern Greece also knows Perperuna, Albanians know Pirpirúnă, and also the Romanians have their Perperona.90 Also, in a certain Bulgarian folk riddle the word perušan is a substitute for the Bulgarian word гърмомеҽица (grmotevitsa) for thunder.91 Moreover, the name of Perun is also commonly found in Southern Slavic toponymy. There are places called: Perun, Perunac, Perunovac, Perunika, Perunićka Glava, Peruni Vrh, Perunja Ves, Peruna Dubrava, Perunuša, Perušice, Perudina and Perutovac.92

- Evans 1974, p. 116.

- ^ Jakobson 1985, p. 23.

- ^ Katičić, Radoslav (2017). Naša stara vjera: Tragovima svetih pjesama naše pretkršćanske starine [Our Old Faith: Tracing the Sacred Poems of Our Pre-Christian Antiquity] (in Croatian). Zagreb: Ibis Grafika, Matica hrvatska. p. 105. ISBN 978-953-6927-98-2.

- Puchner 2009, p. 348.

- Puchner, Walter (1983). "Бележки към ономатологията и етимологиятана българските и гръцките названия на обреда за дъжд додола/перперуна" [Notes on the Onomatology and the Etymology of Bulgarian and Greek Names for the Dodola / Perperuna Rite]. Bulgarian Folklore (in Bulgarian). IX (1): 59–65.

- Puchner 2009, p. 347–349.

- Jakobson 1985, p. 6–7, 21, 23.

- Jakobson 1985, p. 23–24.

- Jakobson 1985, p. 24.

- ^ Puhvel 1987, p. 235.

- Evans 1974, p. 127–128.

- Dauksta, Dainis (2011). "From Post to Pillar – The Development and Persistence of an Arboreal Metaphor". New Perspectives on People and Forests. Springer. p. 112. ISBN 9789400711501.

- ^ Jakobson 1985, p. 22–23.

- Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 94.

- Gieysztor 2006, p. 89, 104–106.

- ^ Zečević, Slobodan (1974). Elementi naše mitologije u narodnim obredima uz igru (in Serbian). Zenica: Muzej grada Zenice. pp. 125–128, 132–133.

- Institut za književnost i umetnost (Hatidža Krnjević) (1985). Rečnik književnih termina [Dictionary of literary terms] (in Serbian). Beograd: Nolit. p. 130, 618. ISBN 9788619006354.

- Sikimić, Biljana (1996). Etimologija i male folklorne forme (in Serbian). Beograd: SANU. pp. 85–86.

О vezi Peruna i prporuša up. Ivanov i Toporov 1974: 113: можно думать об одновременной связи имени nеnеруна - nрnоруша как с обозначением nорошения дождя, его распыления (ср. с.-хорв. ирпошuмu (се), nрnошка и Т.Д.; чешск. pršeti, prch, prš), так и с именем Громовержца. Связъ с порошением дождя представляется тем более вероятной, что соответствующий глагол в ряде индоевропейских язЪП<ов выступает с архаическим удвоением". Za etimologiju sh. ргроrušа up. i Gavazzi 1985: 164.

- Belaj 2007, p. 80, 112.

- Dragić 2007, p. 80, 112.

- Lajoye 2015, p. 114.

- ^ Shedden-Ralston, William Ralston (1872). The Songs of the Russian People: As Illustrative of Slavonic Mythology and Russian Social Life. London: Ellis & Green. p. 227–229.

- ^ Belaj 2007, p. 80.

- D. Decev, Die thrakischen Sprachreste, Wien: R.M. Rohrer, 1957, pp. 144, 151

- Sorin Paliga (2003). "Influenţe romane și preromane în limbile slave de sud" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 28, 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Dragnea, Mihai (2014). "The Thraco-Dacian Origin of the Paparuda/Dodola Rain-Making Ritual". Brukenthalia Acta Musei (4): 18–27.

- Ḱulavkova, Katica (2020). "A Poetic Ritual Invoking Rain and Well-Being: Richard Berengarten's In a Time of Drought". Anthropology of East Europe Review. 37 (1): 19–20.

- Jackson 2002, p. 70.

- ^ York, Michael (1993). "Toward a Proto-Indo-European vocabulary of the sacred". Word. 44 (2): 240, 251. doi:10.1080/00437956.1993.11435902.

- Evans 1974, p. 116–117.

- ^ Čubelić, Tvrtko (1990). Povijest i historija usmene narodne književnosti: historijske i literaturno-teorijske osnove te genološki aspekti: analitičko-sintetički pogledi (in Croatian). Zagreb: Ante Pelivan i Danica Pelivan. p. 75–76. ISBN 9788681703014.

- ^ Dragić 2007, p. 279, 283.

- ^ Dragić, Marko (2012). "Lada i Ljeljo u folkloristici Hrvata i slavenskom kontekstu" [Lada and Ljeljo in the folklore of Croats and Slavic context]. Zbornik radova Filozofskog fakulteta u Splitu (in Croatian). 5: 45, 53–55.

- Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 80–81.

- Muraj 1987, p. 160–161.

- Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 75, 78, 93, 95.

- ^ Vukelić, Deniver (2010). "Pretkršćanski prežici u hrvatskim narodnim tradicijam" [Pre-Christian belief traces in Croatian folk traditions]. Hrvatska revija (in Croatian). No. 4. Matica hrvatska. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 85, 95.

- Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 84–85, 90.

- Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 73, 75–76, 91.

- Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 74–75, 80.

- Dragić 2007, p. 276.

- Puchner 2009, p. 289, 345.

- ^ Dragić 2007, p. 291.

- Puchner, Walter (2016). Die Folklore Südosteuropas: Eine komparative Übersicht (in German). Böhlau Verlag Wien. p. 65. ISBN 9783205203124.

- Cantemir, Dimitrie (1771). Descriptio antiqui et hodierni status Moldaviae (in German). Frankfurt, Leipzig. p. 315–316.

Im Sommer, wenn dem Getreide wegen der Dürre Gefabr bevorzustehen fcheinet, ziehen die Landleute einem kleinen Ragdchen, welches noch nicht über zehen Jahr alt ist, ein Hemde an, welches aus Blattern von Baumen und Srantern gemacht wird. Alle andere Ragdchen und stnaben vol gleiechem Alter folgen ihr, und siehen mit Tanzen und Singen durch die ganze Racharfchaft; wo sie aber hin komuien, da pflegen ihnen die alten Weiber kalt Wasser auf den Stopf zu gieffen. Das Lied, welches fie fingen, ist ohngefähr von folegendem Innbalte: "Papaluga! steige nech dem Himmel, öffne feine Thüren, fend von oben Regen ber, daß der Roggen, Weizen, Hirfe u. f. w. gut wachsen."

- Puchner, Walter (2017). "2 - Byzantium High Culture without Theatre or Dramatic Literature?". Greek Theatre between Antiquity and Independence: A History of Reinvention from the Third Century BC to 1830. Cambridge University Press. p. 73. doi:10.1017/9781107445024.004. ISBN 9781107445024.

...in 1765, a Greek law book from Bucharest quotes the 62nd Canon of the Trullanum in order to forbid public dancing by girls in a custom well known throughout the Balkans as 'paparuda', 'perperuna' or 'dodole', a ritual processional rain dance.

- Габровски, Спиридон Иеросхимонах (1900). История во кратце о болгарском народе славенском. Сочинися и исписа в лето 1792. София: изд. Св. Синод на Българската Църква. pp. 14.

- ^ Ribarić, Josip (2002) . O istarskim dijalektima: razmještaj južnoslavenskih dijalekata na poluotoku Istri s opisom vodičkog govora (in Croatian). Pazin: Josip Turčinović. pp. 84–85, 206. ISBN 953-6262-43-6.

- Gimbutas 1967, p. 743–744.

- Evans 1974, p. 100, 119.

- Jakobson 1985, p. 21, 23.

- Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 74–77, 83–93.

- Muraj 1987, p. 158–163.

- Dragić 2007, p. 290–293.

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 76, 80.

- ^ Muraj 1987, p. 161.

- ^ Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 77, 91–93.

- ^ Predojević 2019, p. 581, 583, 589–591.

- Deželić Jr., Velimir (1937). Kolede: Obrađeni hrvatski godišnji običaji [Kolede: Examined Croatian annual customs] (in Croatian). Hrvatsko književno društvo svetog Jeronima. p. 70.

Ljeti, kad zategnu suše, pošle bi našim selima Prporuše moliti od Boga kišu. Posvuda su Hrvatskom išle Prporuše, a običaj je to prastar — iz pretkršćanskih vremena — ali lijep, pa ga kršćani odobrili, preuzeli i još dotjerali. U stara vremena Prporuše su bile veoma nalik nekom pobožnom obredu, tek poslije su predvodnici — Prpci— počeli suviše lakrdijati, a Prporušama ko da je više do darova, nego do lijepa pjevanja i molitve.

- ^ Horvat, Josip (1939). Kultura Hrvata kroz 1000 godina [Culture of Croats through 1000 years] (in Croatian). Zagreb: A. Velzek. pp. 23–24.

- Kovačević, Ivan (1985). Semiologija rituala [Semiology of ritual] (in Serbian). Beograd: Prosveta. p. 79.

- Dragić 2007, p. 278, 290.

- Predojević 2019, p. 583–584, 589.

- Predojević 2019, p. 581–582, 584.

- Nodilo 1981, p. 51.

- Čulinović-Konstantinović 1963, p. 78.

- ^ Milčetić, Ivan (1896). "Prporuša". Zbornik za narodni život i običaje južnih Slavena. 1. Belgrade: JAZU: 217–218.