| Revision as of 19:37, 25 March 2023 view sourceTomaras12345 (talk | contribs)45 edits Removed poorly sourced statementTags: references removed Visual edit← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:54, 25 March 2023 view source Tomaras12345 (talk | contribs)45 edits Removed poor sources in Tomar and Katoch sectionTags: references removed Visual editNext edit → | ||

| Line 176: | Line 176: | ||

| After the ] conquest of the ] which led to the annexation of Western Punjab into their empire in the 11th century CE, two Punjab dynasties who ruled the territory in the East, the ] based in the region from ] to ] and the ] based in the regions of modern day ], ] and East Punjab, became heavily involved in conflicts with the Ghaznavids. | After the ] conquest of the ] which led to the annexation of Western Punjab into their empire in the 11th century CE, two Punjab dynasties who ruled the territory in the East, the ] based in the region from ] to ] and the ] based in the regions of modern day ], ] and East Punjab, became heavily involved in conflicts with the Ghaznavids. | ||

| According to the Dutch sanskritist ], in 1043 CE, the Raja of the Tomaras conquered the occupied cities of ], ] and other places held by Ghaznavid garrisons under ], before successfully besieging the once captured Nagarkot fort, located in the Kangra district of modern day ], Eastern Punjab. |

According to the Dutch sanskritist ], in 1043 CE, the Raja of the Tomaras conquered the occupied cities of ], ] and other places held by Ghaznavid garrisons under ], before successfully besieging the once captured Nagarkot fort, located in the Kangra district of modern day ], Eastern Punjab. <ref name="auto9">{{Cite book |last1=Hutchison |first1=John |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3btDw4S2FmYC |title=History of the Panjab Hill States |last2=Vogel |first2=Jean Philippe |date=1994 |publisher=Asian Educational Services |isbn=978-81-206-0942-6 |pages=120 |language=en |quote=He then marched against Hansi, Thanesar and other places held by Modud, grandson of Mahmud of Ghazni, and drove them out....}}</ref> He further states that ]'s, son Abd al-Rashid, captured the fort in c. 1052 CE but the Kangra rajas led an expedition which successfully recaptured the ] in 1060 CE, he then concludes that for the next 300 years it would remain in their control.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hutchison |first=John |url=https://books.google.co.uk/books?redir_esc=y&id=3btDw4S2FmYC&q=1043#v=snippet&q=Tomara&f=false |title=History of the Panjab Hill States |last2=Vogel |first2=Jean Philippe |date=1994 |publisher=Asian Educational Services |isbn=978-81-206-0942-6 |pages=123 |language=en |quote=The Kangra rajas were successful in recovering the fort, if captured by the Ghaznavids, is therefore highly probable and we may conclude that from AD 1060 onwards for nearly 300 years, it remained in their possession}}</ref>During the reign of ] (1059-1099) an army of ''ghazis'' consisting of 40,000 cavalry was sent to raid the ] of the ] under his son Mahmud,<ref name="Wink 1997 1342">{{cite book |last=Wink |first=André |title=Al-Hind the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: The Slave Kings and the Islamic Conquests 11th-13th centuries |publisher=Brill |year=1997 |volume=II |page=134}}</ref> c. 1070 CE which led to a battle near the city of ]. The outcome of the battle is uncertain and Jalandhar is not stated in Ghaznavid annals however according to the Diwan-i-salman it was described as eclipsing the battles of Rustam and Isfandiyar.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Hutchison |first1=John |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3btDw4S2FmYC&q=diwan+i+salman+jalandhar |title=History of the Panjab Hill States |last2=Vogel |first2=Jean Philippe |date=1994 |publisher=Asian Educational Services |isbn=978-81-206-0942-6 |pages=123 |language=en |quote=There is a wildness and want of coherance in this Ode, which renders its precise meaning doubtful... The latter place (Jalandhar) is well known but has not before been noticed in Muhammadan annals.... it seems not improbable that the reference given points to the fall of Jalandhar}}</ref> | ||

| During the reign of Ibrahim of Ghazna, the Tomar raja known popularly as ], as per his contemporary ]'s Parshwanath Charit, defeated the Turks at Himachal pradesh. According to ], the Bard chand states that the Kangra and its mountain chiefs owed allegience to Anangpal, implying that they were potentially subject to the Tomaras.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Hutchison |first1=John |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3btDw4S2FmYC&dq=anangpal+tomar+history+of+the+panjab+hill+states&pg=PA72 |title=History of the Panjab Hill States |last2=Vogel |first2=Jean Philippe |date=1994 |publisher=Asian Educational Services |isbn=978-81-206-0942-6 |pages=124 |language=en |quote=Kangra, however, must have been more or less subject do Delhi, for the Bard Chand includes "Kangra and other hill chiefs", among the princes owing allegience to Anang-pal}}</ref> | During the reign of Ibrahim of Ghazna, the Tomar raja known popularly as ], as per his contemporary ]'s Parshwanath Charit, defeated the Turks at Himachal pradesh. According to ], the Bard chand states that the Kangra and its mountain chiefs owed allegience to Anangpal, implying that they were potentially subject to the Tomaras.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Hutchison |first1=John |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3btDw4S2FmYC&dq=anangpal+tomar+history+of+the+panjab+hill+states&pg=PA72 |title=History of the Panjab Hill States |last2=Vogel |first2=Jean Philippe |date=1994 |publisher=Asian Educational Services |isbn=978-81-206-0942-6 |pages=124 |language=en |quote=Kangra, however, must have been more or less subject do Delhi, for the Bard Chand includes "Kangra and other hill chiefs", among the princes owing allegience to Anang-pal}}</ref> | ||

| Line 188: | Line 188: | ||

| The Tughlaq dynasty's reign formally started in 1320 in ] when Ghazi Malik assumed the throne under the title of ] after defeating ] at the ]. | The Tughlaq dynasty's reign formally started in 1320 in ] when Ghazi Malik assumed the throne under the title of ] after defeating ] at the ]. | ||

| The ancestry of the dynasty is debated among modern historians because the earlier sources provide different information regarding it. Tughlaq's court poet Badr-i Chach attempted to find a royal Sassanian genealogy for the dynasty from the line of ]. According to Bhandari and ], Tughlaq was born in Punjab to a Punjabi mother.<ref name="auto11"/> Another of Tughlaq's court poet Amir Khusrau in his ''Tughlaq Nama'' neglects any mention of Tughlaq's arrival in India from a foreign land, presuming he was born in India. His own court poet states that Tughluq described himself frankly as a man of no importance ("''awara mard''") in his early life and career, something that all of his audience knew.<ref>{{cite book |author=Saxena |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.98116/page/n501/mode/2up?q=awara+mard |title=A COMPREHENSIVE HISTORY OF INDIA VOL.5 |publisher=Indian History Congress |year=1970 |page=461}}</ref> Tughlaq Nama declares Tughlaq to have been a minor chief of humble origins.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Husain |first=Mahdi |url=http://worldcat.org/oclc/918427946 |title=Tughluq dynasty |date=1976 |publisher=Chand |pages=31 |oclc=918427946}}</ref><ref name="auto2">{{Cite book |last=Habib |first=Mohammad |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/265982257 |title=Hazrat Amir Khusrau of Delhi |date=2004 |publisher=Cosmo Publications |isbn=978-81-7755-901-9 |location=New Delhi |pages=67 |oclc=265982257}}</ref> Ferishta, based on inquiries at ], wrote that the knowledgeable historians and the books of India had neglected to mention any clear statement on the origin of the dynasty,<ref>{{cite journal |author=Wolseley Haig |date=July 1922 |title=Five Questions in the History of the Tughluq Dynasty of Dihli |journal=The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland |issue=3 |page=320 |jstor=25209907}}</ref> but wrote that there was a rural ] that Tughlaq's father was a Turkic slave of ] who married daughter of ] chieftain of Punjab.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Wolseley Haig |date=July 1922 |title=Five Questions on the History of the Tughluq Dynasty at Dilli |journal=The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland |publisher=] |page=320 |jstor=25209907 |number=3}}</ref> However there are no contemporary sources corroborate this statement.<ref>{{cite book |author=B. P. Saksena |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_9cmAQAAMAAJ |title=A Comprehensive History of India |publisher=The Indian History Congress / People's Publishing House |year=1992 |editor1=Mohammad Habib |volume=5: The Delhi Sultanat (A.D. 1206-1526) |page=461 |chapter=The Tughluqs: Sultan Ghiyasuddin Tughluq |oclc=31870180 |author-link=Banarsi Prasad Saksena |editor2=Khaliq Ahmad Nizami |orig-year=1970}}</ref> The historian Fouzia Ahmed points out that as per the ''Tughlaq Nama'', Tughlaq was not a Balbanid slave because he was not part of the old Turkic nobility, as his family was of humble origins which was newly emergent only during ] rule.<ref name="auto2"/> Instead, in the Tughlaq Nama Tughlaq expressed his loyalty to the ethnically heterogenous Alai regime as his benefactor through which he first entered military service but makes no mention of Balban because his father was never part of Balban's old Sultanate household.<ref>{{cite book |author=Fouzia Farooq Ahmed |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=remKDwAAQBAJ |title=Muslim Rule in Medieval India: Power and Religion in the Delhi Sultanate |date=27 September 2016 |isbn=9781786730824 |pages=151, 248}}</ref> The link with the region of Punjab was also exemplified in the support of the ] ] tribes to Ghazi Malik, who played the central role in his rise to the monarchy.<ref>{{cite book |author=Rānā Muḥammad Sarvar K̲h̲ān̲ |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IARuAAAAMAAJ&q=khokhars+vanguard |title=The Rajputs:History, Clans, Culture, and Nobility · Volume 1| year=2005 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author=I. D. Gaur, Surinder Singh |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QVA0JAzQJkYC&dq=tughluq+punjab&pg=PA19 |title=Popular Literature and Pre-modern Societies in South Asia | year=2008 |publisher=licensees of Pearson Education in South Asia |page=19| isbn=9788131713587 }}</ref> His own court poet, Amir Khusro, wrote a war ballad known as the ] in the ] for the Sultan describing the introduction to his rise to the throne against ].<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=s9VjAAAAMAAJ&q=sajan |title=Explorations: Volumes 10-11 |date=1984 |publisher=Department of English Language and Literature, Government College |page=19}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author=Tariq Rahman |url=https://punjab.global.ucsb.edu/sites/default/files/sitefiles/journals/volume14/no1/14.1_Rahman.pdf |title=Punjabi Language During British Rule |publisher=Quaid-i Azam University, Islamabad |page=1 |quote='Amir Khusro ba Zuban-e-Punjabi ba ibarat-e-marghub muqaddama jang ghazi ul mulk Tughlaq Shah o Nasir uddin Khusro Khan gufta ke aan ra ba Zuban-e-Hind '''var''' guvaend' (Amir Khusro in the language of the Punjab wrote an introduction of the battle between Tughlaq and Khusro which in the language of India is called a '''var''')}}</ref> Tughlaq's administration was dominated by Punjabis from Southern Punjab such as ], indicating their ties to the area and people.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Welch |first1=Anthony |last2=Crane |first2=Howard |date=1983 |title=The Tughluqs: Master Builders of the Delhi Sultanate |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1523075 |journal=Muqarnas |volume=1 |pages=123–125 |doi=10.2307/1523075 |issn=0732-2992 |jstor=1523075}}</ref>The city of Dipalpur in Punjab, according to ], was the favorite residence of the third successor of the dynasty, ], which may further support the view of their origins in the area.<ref>{{cite book |author=Sir Alexander Cunningham |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3DY8AoP7IiMC&q=firuz+shah+favorite+residence |title=Cunningham's Ancient Geography of India |date=1924 |page=224}}</ref> | The ancestry of the dynasty is debated among modern historians because the earlier sources provide different information regarding it. Tughlaq's court poet Badr-i Chach attempted to find a royal Sassanian genealogy for the dynasty from the line of ]. According to Bhandari and ], Tughlaq was born in Punjab to a Punjabi mother.<ref name="auto11"/> Another of Tughlaq's court poet Amir Khusrau in his ''Tughlaq Nama'' neglects any mention of Tughlaq's arrival in India from a foreign land, presuming he was born in India. His own court poet states that Tughluq described himself frankly as a man of no importance ("''awara mard''") in his early life and career, something that all of his audience knew.<ref>{{cite book |author=Saxena |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.98116/page/n501/mode/2up?q=awara+mard |title=A COMPREHENSIVE HISTORY OF INDIA VOL.5 |publisher=Indian History Congress |year=1970 |page=461}}</ref> Tughlaq Nama declares Tughlaq to have been a minor chief of humble origins.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Husain |first=Mahdi |url=http://worldcat.org/oclc/918427946 |title=Tughluq dynasty |date=1976 |publisher=Chand |pages=31 |oclc=918427946}}</ref><ref name="auto2">{{Cite book |last=Habib |first=Mohammad |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/265982257 |title=Hazrat Amir Khusrau of Delhi |date=2004 |publisher=Cosmo Publications |isbn=978-81-7755-901-9 |location=New Delhi |pages=67 |oclc=265982257}}</ref> Ferishta, based on inquiries at ], wrote that the knowledgeable historians and the books of India had neglected to mention any clear statement on the origin of the dynasty,<ref>{{cite journal |author=Wolseley Haig |date=July 1922 |title=Five Questions in the History of the Tughluq Dynasty of Dihli |journal=The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland |issue=3 |page=320 |jstor=25209907}}</ref> but wrote that there was a rural ] that Tughlaq's father was a Turkic slave of ] who married daughter of a ] chieftain of Punjab.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Wolseley Haig |date=July 1922 |title=Five Questions on the History of the Tughluq Dynasty at Dilli |journal=The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland |publisher=] |page=320 |jstor=25209907 |number=3}}</ref> However there are no contemporary sources corroborate this statement.<ref>{{cite book |author=B. P. Saksena |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_9cmAQAAMAAJ |title=A Comprehensive History of India |publisher=The Indian History Congress / People's Publishing House |year=1992 |editor1=Mohammad Habib |volume=5: The Delhi Sultanat (A.D. 1206-1526) |page=461 |chapter=The Tughluqs: Sultan Ghiyasuddin Tughluq |oclc=31870180 |author-link=Banarsi Prasad Saksena |editor2=Khaliq Ahmad Nizami |orig-year=1970}}</ref> The historian Fouzia Ahmed points out that as per the ''Tughlaq Nama'', Tughlaq was not a Balbanid slave because he was not part of the old Turkic nobility, as his family was of humble origins which was newly emergent only during ] rule.<ref name="auto2"/> Instead, in the Tughlaq Nama Tughlaq expressed his loyalty to the ethnically heterogenous Alai regime as his benefactor through which he first entered military service but makes no mention of Balban because his father was never part of Balban's old Sultanate household.<ref>{{cite book |author=Fouzia Farooq Ahmed |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=remKDwAAQBAJ |title=Muslim Rule in Medieval India: Power and Religion in the Delhi Sultanate |date=27 September 2016 |isbn=9781786730824 |pages=151, 248}}</ref> The link with the region of Punjab was also exemplified in the support of the ] ] tribes to Ghazi Malik, who played the central role in his rise to the monarchy.<ref>{{cite book |author=Rānā Muḥammad Sarvar K̲h̲ān̲ |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IARuAAAAMAAJ&q=khokhars+vanguard |title=The Rajputs:History, Clans, Culture, and Nobility · Volume 1| year=2005 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author=I. D. Gaur, Surinder Singh |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QVA0JAzQJkYC&dq=tughluq+punjab&pg=PA19 |title=Popular Literature and Pre-modern Societies in South Asia | year=2008 |publisher=licensees of Pearson Education in South Asia |page=19| isbn=9788131713587 }}</ref> His own court poet, Amir Khusro, wrote a war ballad known as the ] in the ] for the Sultan describing the introduction to his rise to the throne against ].<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=s9VjAAAAMAAJ&q=sajan |title=Explorations: Volumes 10-11 |date=1984 |publisher=Department of English Language and Literature, Government College |page=19}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author=Tariq Rahman |url=https://punjab.global.ucsb.edu/sites/default/files/sitefiles/journals/volume14/no1/14.1_Rahman.pdf |title=Punjabi Language During British Rule |publisher=Quaid-i Azam University, Islamabad |page=1 |quote='Amir Khusro ba Zuban-e-Punjabi ba ibarat-e-marghub muqaddama jang ghazi ul mulk Tughlaq Shah o Nasir uddin Khusro Khan gufta ke aan ra ba Zuban-e-Hind '''var''' guvaend' (Amir Khusro in the language of the Punjab wrote an introduction of the battle between Tughlaq and Khusro which in the language of India is called a '''var''')}}</ref> Tughlaq's administration was dominated by Punjabis from Southern Punjab such as ], indicating their ties to the area and people.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Welch |first1=Anthony |last2=Crane |first2=Howard |date=1983 |title=The Tughluqs: Master Builders of the Delhi Sultanate |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1523075 |journal=Muqarnas |volume=1 |pages=123–125 |doi=10.2307/1523075 |issn=0732-2992 |jstor=1523075}}</ref>The city of Dipalpur in Punjab, according to ], was the favorite residence of the third successor of the dynasty, ], which may further support the view of their origins in the area.<ref>{{cite book |author=Sir Alexander Cunningham |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3DY8AoP7IiMC&q=firuz+shah+favorite+residence |title=Cunningham's Ancient Geography of India |date=1924 |page=224}}</ref> | ||

| During Ghazi Maliks reign, in 1321 he sent his eldest son Jauna Khan, later known as Muhammad bin Tughlaq, to ] to plunder the Hindu kingdoms of Arangal and Tilang (now part of ]). His first attempt was a failure.<ref name="lowe296">William Lowe (Translator), {{Google books|RFNOAAAAYAAJ|Muntakhabu-t-tawārīkh|page=296}}, Volume 1, pages 296-301</ref> Four months later, Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq sent large army reinforcements for his son asking him to attempt plundering Arangal and Tilang again.<ref> Ziauddin Barni, The History of India by its own Historians - The Muhammadan Period, Volume 3, Trubner London, pages 233-234</ref> This time Jauna Khan succeeded and Arangal fell, it was renamed to Sultanpur, and all plundered wealth, state treasury and captives were transferred from the captured kingdom to the Delhi Sultanate.The Muslim aristocracy in Lukhnauti (Bengal) invited Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq to extend his coup and expand eastwards into Bengal by attacking ], which he did over 1324–1325 AD,<ref name="lowe296" /> after placing Delhi under control of his son Ulugh Khan, and then leading his army to Lukhnauti. Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq succeeded in this campaign. | During Ghazi Maliks reign, in 1321 he sent his eldest son Jauna Khan, later known as Muhammad bin Tughlaq, to ] to plunder the Hindu kingdoms of Arangal and Tilang (now part of ]). His first attempt was a failure.<ref name="lowe296">William Lowe (Translator), {{Google books|RFNOAAAAYAAJ|Muntakhabu-t-tawārīkh|page=296}}, Volume 1, pages 296-301</ref> Four months later, Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq sent large army reinforcements for his son asking him to attempt plundering Arangal and Tilang again.<ref> Ziauddin Barni, The History of India by its own Historians - The Muhammadan Period, Volume 3, Trubner London, pages 233-234</ref> This time Jauna Khan succeeded and Arangal fell, it was renamed to Sultanpur, and all plundered wealth, state treasury and captives were transferred from the captured kingdom to the Delhi Sultanate.The Muslim aristocracy in Lukhnauti (Bengal) invited Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq to extend his coup and expand eastwards into Bengal by attacking ], which he did over 1324–1325 AD,<ref name="lowe296" /> after placing Delhi under control of his son Ulugh Khan, and then leading his army to Lukhnauti. Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq succeeded in this campaign. | ||

Revision as of 19:54, 25 March 2023

Geographical Region in South Asia This article is about the geographical region. For the province of Pakistan, see Punjab, Pakistan. For the state of India, see Punjab, India. For other uses, see Punjab (disambiguation).Region

| Punjab ਪੰਜਾਬ • پنجاب | |

|---|---|

| Region | |

| Panjab region | |

| Nickname: Land of the five rivers | |

Location of Punjab in South Asia Location of Punjab in South Asia | |

| Coordinates: 31°N 74°E / 31°N 74°E / 31; 74 | |

| Countries | |

| Largest city | Lahore |

| Area | |

| • Total | 458,354.5 km (176,971.7 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Total | c. 190 million |

| Demonym | Punjabi |

| Demographics | |

| • Ethnic groups | Punjabis Minor: Saraikis, Hindkowans, Haryanvis, Pashtuns, Himachalis, Dogras, Muhajirs, Kashmiris, Biharis |

| • Languages | Punjabi and others |

| • Religions | Islam (60%) Hinduism (29%) Sikhism (10%) Christianity (1%) Others (<1%) |

| Time zones | UTC+05:30 (IST in India) |

| UTC+05:00 (PKT in Pakistan) | |

| Demographics based on British Punjab's colonial borders | |

| Part of a series on |

| Punjabis |

|---|

|

| History |

|

DiasporaAsia

Europe North America Oceania |

| Culture |

| Regions |

Punjab portal |

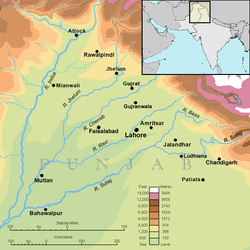

Punjab (/pʌnˈdʒɑːb, -ˈdʒæb, ˈpʌn-/; Template:Lang-pa; Template:Lang-pa; Punjabi: [pənˈdʒaːb] ; also romanised as Panjāb or Panj-Āb) is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, on the Indus Plain comprising areas of eastern Pakistan and northwestern India. Punjab's major cities are Lahore, Faisalabad, Rawalpindi, Gujranwala, Multan, Ludhiana, Amritsar, Sialkot, Chandigarh, Shimla, Jalandhar, Gurugram, and Bahawalpur.

Punjab grew out of the settlements along the five rivers, which served as an important route to the Near East as early as the ancient Indus Valley civilization, dating back to 3000 BCE, and had numerous migrations by the Indo-Aryan peoples. Agriculture has been the major economic feature of the Punjab and has therefore formed the foundation of Punjabi culture, with one's social status being determined by land ownership. The Punjab emerged as an important agricultural region, especially following the Green Revolution during the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, and has been described as the "breadbasket of both India and Pakistan."

The history of Punjab is one filled with conflict, however between the turmoil many native dynasties and empires were created. Following Alexander the Great's invasion and his conflicts with Porus in the 4th century BCE, Chandragupta allied with various Punjabi republics to defeat Dhana Nanda and form the Mauryan empire. After its decline during the 2nd century BCE, the Indo-Greeks, Kushan Empire and Indo-Scythians successively established kingdoms in Punjab however they were ultimately defeated by Eastern Punjab republics which were the Yaudheyas, Trigartas, Audumbaras, Arjunayanas and Kunindas. The devastating Hunnic invasions occurred in the 5th and 6th CE however were ultimately vanquished by the Vardhana dynasty of Thanesar, which proceeded to rule over Northern India. In the 8th century CE the Hindu Shahi empire was formed, accredited for the defeat of the Saffarid dynasty and Samanid Empire. In the same period, between the 8th and 12th century, the Tomara dynasty and Katoch dynasty controlled the eastern Punjab region and resisted many invasion attempts from the Ghaznavids. Islam became established in Western Punjab under the Ghaznavids. The Delhi Sultanate which succeeded it contained many Punjab originating dynasties such as the Tughlaq dynasty and the Sayyid dynasty. The Langah Sultanate ruled much of south Punjab in the 15th century, and is praised for its victory over the Lodi dynasty. After a period of anarchy due to the decline of the Mughals in the 18th century, the Khalsa Raaj in 1799 CE formed and began various conquests into Kashmir and Durrani Empire held territories.

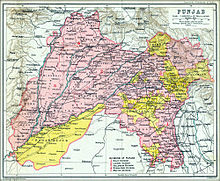

The boundaries of the region are ill-defined and focus on historical accounts and thus the geographical definition of the term "Punjab" has changed over time. In the 16th century Mughal Empire the Punjab region was divided into three, with the Lahore Subah in the west, the Delhi Subah in the east and the Multan Subah in the south. In British India, until the Partition of India in 1947, the Punjab Province encompassed the present-day Indian states and union territories of Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Chandigarh, and Delhi, and the Pakistani regions of Punjab, and Islamabad Capital Territory.

The predominant ethnolinguistic group of the Punjab region are the Punjabi people, who speak the Indo-Aryan Punjabi language. Punjabi Muslims are the majority in West Punjab (Pakistan), while Punjabi Sikhs are the majority in East Punjab (India). Other religious groups are Christianity, Jainism, Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, and Ravidassia.

Etymology

Although the name Punjab is of Persian origin, its two parts (Template:Lang-fa and Template:Lang-fa) are cognates of the Sanskrit words, Template:Lang-sa and Template:Lang-sa, of the same meaning. The word pañjāb thus means "The Land of Five Waters," referring to the rivers Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Sutlej, and Beas. All are tributaries of the Indus River, the Sutlej being the largest. References to a land of five rivers may be found in the Mahabharata, which calls one of the regions in ancient Bharat Panchanada (Template:Lang-sa). Persian place names are very common in Northwest India and Pakistan. The ancient Greeks referred to the region as Pentapotamía (Template:Lang-el), which has the same meaning as the Persian word.

History

Main article: History of the PunjabAncient period

The Punjab region is noted as the site of one of the earliest urban societies, the Indus Valley Civilization that flourished from about 3000 B.C. and declined rapidly 1,000 years later, following the Indo-Aryan migrations that overran the region in waves between 1500 and 500 B.C. Frequent intertribal wars stimulated the growth of larger groupings ruled by chieftains and kings, who ruled local kingdoms known as Mahajanapadas. The rise of kingdoms and dynasties in the Punjab is chronicled in the ancient Hindu epics, particularly the Mahabharata. The epic battles described in the Mahabharata are chronicled as being fought in what is now the state of Haryana and historic Punjab. The Gandharas, Kambojas, Trigartas, Andhra, Pauravas, Bahlikas (Bactrian settlers of the Punjab), Yaudheyas, and others sided with the Kauravas in the great battle fought at Kurukshetra. According to Dr Fauja Singh and Dr. L. M. Joshi: "There is no doubt that the Kambojas, Daradas, Kaikayas, Andhra, Pauravas, Yaudheyas, Malavas, Saindhavas, and Kurus had jointly contributed to the heroic tradition and composite culture of ancient Punjab."

Invasions of Alexander the Great (c. 4th century BCE )

The earliest known notable local king of this region was known as King Porus, who fought the famous Battle of the Hydaspes against Alexander the Great. His kingdom spanned between rivers Hydaspes (Jhelum) and Acesines (Chenab); Strabo had held the territory to contain almost 300 cities. He (alongside Abisares) had a hostile relationship with the Kingdom of Taxila which was ruled by his extended family. When the armies of Alexander crossed Indus in its eastward migration, probably in Udabhandapura, he was greeted by the-then ruler of Taxila, Omphis. Omphis had hoped to force both Porus and Abisares into submission leveraging the might of Alexander's forces and diplomatic missions were mounted, but while Abisares accepted the submission, Porus refused. This led Alexander to seek for a face-off with Porus. Thus began the Battle of the Hydaspes in 326 BC; the exact site remains unknown. The battle is thought to be resulted in a decisive Greek victory; however, A. B. Bosworth warns against an uncritical reading of Greek sources who were obviously exaggerative.

Alexander later founded two cities—Nicaea at the site of victory and Bucephalous at the battle-ground, in memory of his horse, who died soon after the battle. Later, tetradrachms would be minted depicting Alexander on horseback, armed with a sarissa and attacking a pair of Indians on an elephant. Porus refused to surrender and wandered about atop an elephant, until he was wounded and his force routed. When asked by Alexander how he wished to be treated, Porus replied "Treat me as a king would treat another king". Despite the apparently one-sided results, Alexander was impressed by Porus and chose to not depose him. Not only was his territory reinstated but also expanded with Alexander's forces annexing the territories of Glausaes, who ruled to the northeast of Porus' kingdom.

After Alexander's death in 323 BCE, Perdiccas became the regent of his empire, and after Perdiccas's murder in 321 BCE, Antipater became the new regent. According to Diodorus, Antipater recognized Porus's authority over the territories along the Indus River. However, Eudemus, who had served as Alexander's satrap in the Punjab region, treacherously killed Porus.

Eastern Punjab republics (c. 4th BCE - c. 4th CE)

The Eastern Punjab republics, part of the Punjab Janapadas, were a group of republics during the ancient period of Punjab, militaristic in nature, consisting of the Yaudheyas, Arjunayanas, Kunindas, Trigartas and the Audumbaras. Before the rise of the Mauryan empire and the eventual defeat of the Nanda Empire, Chandragupta sought support from these republics, most notably the Yaudheyas and the Trigartas, before pursuing Dhana Nanda. According to the Sanskrit and Jain texts Mudrarakshasa and Parishishtaparvan, Chandragupta made an alliance with the Trigarta chief Parvatek who's dominion spread into the Himachal hills and his capital at Jalandhar. The chief of the Mauryan military was always a Yaudheyan warrior according to the Bijaygadh Pillar inscription, which states that the Yaudheyas elected their own chief who also served as the general for the Mauryan army. The core of the Mauryan army and Chandraguptas initial military when battling the Nandas, was made of up men from the Punjab Janapadas according to Thomas William Rhys Davids.

After the eventual fall of the Mauryans, the Indo-Greek Kingdom took its place in the Western Punjab. The Eastern Punjab supposedly wouldn't become subdued till the rule of Menander I. The republics then begin to battle with his successors; the Trigartas producing their own coinage, the Yaudheyas and Arjunayanas winning "victory by the sword" and the Audumbaras under their ruler Dharagosha checking the indo Greek advance to the upper bari doab (ravi river) defining their control in the region.

Two centuries after defeating the Indo-Greek Kingdom, the republics would become controlled by the Kushan Empire under Kanishka. However in the early 3rd century CE after his death, a union formed between the republics to expel the Kushans, resulting in a Kushan defeat and them being pushed out of Eastern Punjab, as stated by the historian Anant Sadashiv Altekar. This can also be confirmed through their coinage inscription stating 'Yaudheyanam jayamantra daramanam' boasting their military victory.

A century later, according to the Allahabad pillar inscription, the republics would become tributaries of the Guptas however this would be done without a fight and according to Upinder Singh there is no specific mention of them providing troops, indicating loose ties.This period ultimately saw the disappearance of the republics.

Mauryan empire (c. 320–180 BCE)

Chandragupta Maurya, with the aid of Kautilya, had established his empire around 320 B.C. The early life of Chandragupta Maurya is not clear. Kautilya enrolled the young Chandragupta in the university at Taxila to educate him in the arts, sciences, logic, mathematics, warfare, and administration. Megasthenes' account, as it has survived in Greek texts that quote him, states that Alexander the Great and Chandragupta met, which if true would mean his rule started earlier than 321 BCE. As Alexander never crossed the Beas river, so his territory probably lied in Punjab region. He has also been variously identified with Shashigupta (who has same etymology as of Chandragupta) of Paropamisadae (western Punjab) on the account of same life events. With the help of the small Janapadas of Punjab, he had gone on to conquer much of the North West Indian subcontinent. He then defeated the Nanda rulers in Pataliputra to capture the throne. Chandragupta Maurya fought Alexander's successor in the east, Seleucus when the latter invaded. In a peace treaty, Seleucus ceded all territories west of the Indus and offered a marriage, including a portion of Bactria, while Chandragupta granted Seleucus 500 elephants. The chief of the Mauryan military was also always a Yaudheyan warrior according to the Bijaygadh Pillar inscription, which states that the Yaudheyas elected their own chief who also served as the general for the Mauryans. The Mauryan military was also made up vastly of men from the Punjab Janapadas.

Chandragupta's rule was very well organised. The Mauryans had an autocratic and centralised administration system, aided by a council of ministers, and also a well-established espionage system. Much of Chandragupta's success is attributed to Chanakya, the author of the Arthashastra. According to buddhist sources Chanakya was native of the Punjab who resided in Taxila. Much of the Mauryan rule had a strong bureaucracy that had regulated tax collection, trade and commerce, industrial activities, mining, statistics and data, maintenance of public places, and upkeep of temples.

Medieval period

Vardhana empire (c. 500–650 CE)

In the 6th century CE the Vardhana dynasty, based in the area of Thanesar (Ambala district of Eastern Punjab), rose to prominence during the second hunnic wars. Its first notable ruler, Adityavardhana, according to the Mandsaur fragmentary inscription conquered the region of Mandsaur between 497 and 500 CE, later also taking part in the Battle of Sondani with Yashodharman which saw the defeat of the Alchon hun ruler Mihirakula.

Adityavardhanas successor, Prabhakaravardhana, according to Bāṇabhaṭṭa, who was the court poet for Harsha, credits him with a strong stance against the Hunas, describing him as :"A lion to the Huna deer, a burning fever to the king of the Indus land (Sindh), a troubler of the sleep of Gujarat king, a billious plague to that scent-elephant, the lord of Gandhara, a destroyer of the skill of the Latas." Inferring various conquests during his reign.

His death in 605 CE led to his eldest son Rajyavardhana, who was battling the Huns in Ghandara with his brother Harsha at the time of his death, succeeding him. The Maukhari king, Grahavarman, was married to Rajyavardhanas sister, but some years later he had been killed by the king of Malwa, leading to her being captured. In retaliation, Rajyavardhana marched against the King and defeated him. However Shashanka of Gauda (Eastern Bengal), in secret alliance with the Malwa king, entered Magadha as a friend of Rajyavardhana. but treacherously murdered him in c. 606 CE.

The Harshacharita states that Prabhakara's younger son Harsha-Vardhana then vowed to destroy the Gauda (Eastern Bengal) king and their allies. He formed an alliance with Bhaskar Varman, the king of Kamarupa, and forced Shashanka to retreat. Subsequently, Harsha was formally crowned as an emperor after he united the small republics from Punjab to central India. Their representatives crowned him king at an assembly in April 606 CE giving him the title of Maharaja. Harsha established an empire that brought all of northern India under his control.

The rough territorial extent of the Vardhana empire according to Alexander Cunningham paraphrasing Xuanzang was between the areas of Kashmir, Nepal and the Narmada River.

Hindu Shahi Empire (c. 820–1030 CE)

In the 9th century, the Hindu Shahi dynasty, with their origins disputed between the region of Oddiyana and with roots as Punjabi Brahmins, replaced the Taank kingdom, ruling Western Punjab along with eastern Afghanistan. The tribe of the Gakhars/Khokhars, formed a large part of the Hindu Shahi army according to the Persian historian Firishta. The most notable rulers of the empire were Lalliya, Bhimadeva and Jayapala who were accredited for military victories.

Lalliya had reclaimed the territory at and around Kabul between 879 and 901 CE after it had been lost under his predecessor to the Saffarid dynasty. He was described as a fearsome Shahi. Two of his ministers reconstructed by Rahman as Toramana and Asata are said to of have taken advantage of Amr al-Layth's preoccupation with rebellions in Khorasan, by successfully raiding Ghazna around 900 CE.

After a defeat in Eastern Afghanistan suffered on the Shahi ally Lawik, Bhimadeva mounted a combined attack around 963 CE. Abu Ishaq Ibrahim was expelled from Ghazna and Shahi-Lawik strongholds were restored in Kabul and adjacent areas. This victory appears to have been commemorated in the Hund Slab Inscription (HSI).

Tomar and Katoch dynasties (c. 900–1150 CE)

After the Ghaznavids conquest of the Hindu Shahis which led to the annexation of Western Punjab into their empire in the 11th century CE, two Punjab dynasties who ruled the territory in the East, the Katoch dynasty based in the region from Himachal Pradesh to Jalandhar and the Tomara dynasty based in the regions of modern day Haryana, Delhi and East Punjab, became heavily involved in conflicts with the Ghaznavids.

According to the Dutch sanskritist J. Ph. Vogel, in 1043 CE, the Raja of the Tomaras conquered the occupied cities of Hansi, Thanesar and other places held by Ghaznavid garrisons under Mawdud of Ghazni, before successfully besieging the once captured Nagarkot fort, located in the Kangra district of modern day Himachal Pradesh, Eastern Punjab. He further states that Mahmud of Ghazni's, son Abd al-Rashid, captured the fort in c. 1052 CE but the Kangra rajas led an expedition which successfully recaptured the Kangra fort in 1060 CE, he then concludes that for the next 300 years it would remain in their control.During the reign of Ibrahim of Ghazna (1059-1099) an army of ghazis consisting of 40,000 cavalry was sent to raid the Doab of the Punjab region under his son Mahmud, c. 1070 CE which led to a battle near the city of Jalandhar. The outcome of the battle is uncertain and Jalandhar is not stated in Ghaznavid annals however according to the Diwan-i-salman it was described as eclipsing the battles of Rustam and Isfandiyar.

During the reign of Ibrahim of Ghazna, the Tomar raja known popularly as Anangpal Tomar, as per his contemporary Vibudh Shridhar's Parshwanath Charit, defeated the Turks at Himachal pradesh. According to J. Ph. Vogel, the Bard chand states that the Kangra and its mountain chiefs owed allegience to Anangpal, implying that they were potentially subject to the Tomaras.

Turkic rule (c. 1030–1320 CE)

The Turkic Ghaznavids in the tenth century overthrew the Hindu Shahis and consequently ruled for 157 years in Western Punjab, gradually declining as a power until the Ghurid conquest of Lahore by Muhammad of Ghor in 1186, deposing the last Ghaznavid ruler Khusrau Malik. Following the death of Muhammad of Ghor in 1206 by Punjabi assassins near the Jhelum river, the Ghurid state fragmented and was replaced in northern India by the Delhi Sultanate.

Tughlaq dynasty (c. 1320–1410 CE)

The Tughlaq dynasty's reign formally started in 1320 in Delhi when Ghazi Malik assumed the throne under the title of Ghiyath al-Din Tughluq after defeating Khusrau Khan at the Battle of Lahrawat.

The ancestry of the dynasty is debated among modern historians because the earlier sources provide different information regarding it. Tughlaq's court poet Badr-i Chach attempted to find a royal Sassanian genealogy for the dynasty from the line of Bahram Gur. According to Bhandari and Firishta, Tughlaq was born in Punjab to a Punjabi mother. Another of Tughlaq's court poet Amir Khusrau in his Tughlaq Nama neglects any mention of Tughlaq's arrival in India from a foreign land, presuming he was born in India. His own court poet states that Tughluq described himself frankly as a man of no importance ("awara mard") in his early life and career, something that all of his audience knew. Tughlaq Nama declares Tughlaq to have been a minor chief of humble origins. Ferishta, based on inquiries at Lahore, wrote that the knowledgeable historians and the books of India had neglected to mention any clear statement on the origin of the dynasty, but wrote that there was a rural founding myth that Tughlaq's father was a Turkic slave of Balban who married daughter of a Punjabi Jatt chieftain of Punjab. However there are no contemporary sources corroborate this statement. The historian Fouzia Ahmed points out that as per the Tughlaq Nama, Tughlaq was not a Balbanid slave because he was not part of the old Turkic nobility, as his family was of humble origins which was newly emergent only during Alai rule. Instead, in the Tughlaq Nama Tughlaq expressed his loyalty to the ethnically heterogenous Alai regime as his benefactor through which he first entered military service but makes no mention of Balban because his father was never part of Balban's old Sultanate household. The link with the region of Punjab was also exemplified in the support of the Punjabi Khokhar tribes to Ghazi Malik, who played the central role in his rise to the monarchy. His own court poet, Amir Khusro, wrote a war ballad known as the Vaar in the Punjabi language for the Sultan describing the introduction to his rise to the throne against Khusrau Shah. Tughlaq's administration was dominated by Punjabis from Southern Punjab such as Ayn al-Mulk Multani, indicating their ties to the area and people.The city of Dipalpur in Punjab, according to Alexander Cunningham, was the favorite residence of the third successor of the dynasty, Sultan Firuz Shah, which may further support the view of their origins in the area.

During Ghazi Maliks reign, in 1321 he sent his eldest son Jauna Khan, later known as Muhammad bin Tughlaq, to Deogir to plunder the Hindu kingdoms of Arangal and Tilang (now part of Telangana). His first attempt was a failure. Four months later, Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq sent large army reinforcements for his son asking him to attempt plundering Arangal and Tilang again. This time Jauna Khan succeeded and Arangal fell, it was renamed to Sultanpur, and all plundered wealth, state treasury and captives were transferred from the captured kingdom to the Delhi Sultanate.The Muslim aristocracy in Lukhnauti (Bengal) invited Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq to extend his coup and expand eastwards into Bengal by attacking Shamsuddin Firoz Shah, which he did over 1324–1325 AD, after placing Delhi under control of his son Ulugh Khan, and then leading his army to Lukhnauti. Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq succeeded in this campaign.

After his fathers death in 1325 CE, Muhammed Bin Tughlaq assumed power and his rule saw the empire expand to most of the Indian subcontinent, its peak in terms of geographical reach. He attacked and plundered Malwa, Gujarat, Lakhnauti, Chittagong, Mithila and many other regions in India His distant campaigns were expensive, although each raid and attack on non-Muslim kingdoms brought new looted wealth and ransom payments from captured people. The extended empire was difficult to retain, and rebellions all over Indian subcontinent became routine.Muhammad bin Tughlaq died in March 1351 while trying to chase and punish people for rebellion and their refusal to pay taxes in Sindh and Gujarat.

The Tughlaq empire after Muhammed Bin Tughluqs death was in a state of disarray with many regions assuming independance, it was at this point that Firuz Shah Tughlaq, Ghazi Maliks nephew, took reign. His father's name was Rajab (the younger brother of Ghazi Malik) who had the title Sipahsalar. His mother Naila was a Punjabi Bhatti princess (daughter of Rana Mal) from Dipalpur and Abohar according the historian William Crooke. The southern states had drifted away from the Sultanate and there were rebellions in Gujarat and Sindh", while "Bengal asserted its independence." He led expeditions against Bengal in 1353 and 1358. He captured Cuttack, desecrated the Jagannath Temple, Puri, and forced Raja Gajpati of Jajnagar in Orissa to pay tribute. He also laid siege to the Kangra Fort and forced Nagarkot to pay tribute. During his time Tatar Khan of Greater Khorasan attacked Punjab however he was defeated and his face slashed by the sword given by Feroz Shah Tughlaq to Raja Kailas Pal who ruled the Nagarkot region in Punjab.

Sayyid dynasty (c. 1410–1450 CE)

See also: Sayyid dynastyKhizr Khan established the Sayyid dynasty, the fourth dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate after the fall of the Tughlaqs. A contemporary writer Yahya Sirhindi mentions in his Takhrikh-i-Mubarak Shahi that Khizr Khan was a descendant of prophet Muhammad. However, Yahya Sirhindi based his conclusions on unsubstantial evidence, the first being a casual recognition by the famous saint Sayyid Jalaluddin Bukhari of Uch Sharif of his Sayyid heritage, and secondly the noble character of the Sultan which distinguished him as a Prophet's descendant.

According to Richard M. Eaton and oriental scholar Simon Digby Khizr Khan was a Punjabi chieftain belonging to the Khokhar clan. This view is echoed by Francesca Orsini and Samira Sheikh in their work. Jaswant Lal Mehta describes Khizr Khan as a leading Indian noble who belonged to a family of Multan. According to the Dayal Das Bikaner Khyat, Malik Sulaiman, the father of Khizr Khan, while working as the Nawab of Multan, led an expedition for the recapture of Nagaur from the Rathore Rajputs and installed Firoz Khan the son of Jalal Khan Khokhar as the ruler of Nagaur. Khizr Khan's native town was Fathpur in Punjab (present-day Pakistan) which also served as the capital of the sultanate before the capture of Delhi in 1414.

Following Timur's 1398 Sack of Delhi, he appointed Khizr Khan as deputy of Multan (Punjab). He held Lahore, Dipalpur, Multan and Upper Sindh. Khizr Khan captured Delhi on 28 May 1414 thereby establishing the Sayyid dynasty. Khizr Khan did not take up the title of Sultan, but continued the fiction of his allegiance to Timur as Rayat-i-Ala(vassal) of the Timurids - initially that of Timur, and later his son Shah Rukh. After the accession of Khizr Khan, the Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and Sindh were reunited under the Delhi Sultanate, where he spent his time subduing rebellions. Punjab was the powerbase of Khizr Khan and his successors as the bulk of the Delhi army during their reigns came from Multan and Dipalpur.

Khizr Khan was succeeded by his son Mubarak Shah after his death on 20 May 1421. Mubarak Shah referred to himself as Muizz-ud-Din Mubarak Shah on his coins, removing the Timurid name with the name of the Caliph, and declared himself a Shah. He defeated the advancing Hoshang Shah Ghori, ruler of Malwa Sultanate and forced him to pay heavy tribute early in his reign. Mubarak Shah also put down the rebellion of Jasrath Khokhar and managed to fend off multiple invasions by the Timurids of Kabul.

The last ruler of the Sayyids, Ala-ud-Din, voluntarily abdicated the throne of the Delhi Sultanate in favour of Bahlul Khan Lodi on 19 April 1451, and left for Badaun, where he died in 1478.

Langah sultanate (c. 1450–1540 CE)

In 1445, Sultan Qutbudin, chief of Langah, a Jat Zamindar tribe established the Langah Sultanate in Multan after the fall of the Sayyid dynasty. Husseyn Langah I (reigned 1456–1502) was the second ruler of Langah Sultanate. He undertook military campaigns in Punjab and captured Chiniot and Shorkot from the Lodis. Shah Husayn successfully repulsed attempted invasion by the Lodis led by Tatar Khan and Barbak Shah, as well as his daughter Zeerak Rumman.

Modern period

Mughal empire (c. 1526–1761 CE)

The Mughals came to power in the early sixteenth century and gradually expanded to control all of the Punjab from their capital at Lahore. During the Mughal era, Saadullah Khan, born into a family of Punjabi agriculturalists belonging to the Thaheem tribe from Chiniot remained Grand vizier (or Prime Minister) of the Mughal Empire in the period 1645–1656. Other prominent Muslims from Punjab who rose to nobility during the Mughal Era include Wazir Khan, Adina Beg Arain, and Shahbaz Khan Kamboh. The Mughal Empire ruled the region until it was severely weakened in the eighteenth century. As Mughal power weakened, Afghan rulers took control of the region. Contested by Marathas and Afghans, the region was the center of the growing influence of the Misls, who expanded and established the Khalsa Raj as the Mughals and Afghans weakened, ultimately ruling the Punjab,Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and territories north into the Himalayas.

Sikh Empire (c. 1799–1849 CE)

See also: Sikh EmpireIn the 19th century, Maharaja Ranjit Singh established the Sikh Empire based in the Punjab. The empire existed from 1799, when Ranjit Singh captured Lahore, to 1849, when it was defeated and conquered in the Second Anglo-Sikh War. It was forged on the foundations of the Khalsa from a collection of autonomous Sikh misls. At its peak in the 19th century, the Empire extended from the Khyber Pass in the west to western Tibet in the east, and from Mithankot in the south to Kashmir in the north. It was divided into four provinces: Lahore, in Punjab, which became the Sikh capital; Multan, also in Punjab; Peshawar; and Kashmir from 1799 to 1849. Religiously diverse, with an estimated population of 3.5 million in 1831 (making it the 19th most populous country at the time), it was the last major region of the Indian subcontinent to be annexed by the British Empire.

British Punjab (c. 1849–1947 CE)

The Sikh Empire ruled the Punjab until the British annexed it in 1849 following the First and Second Anglo-Sikh Wars. Most of the Punjabi homeland formed a province of British India, though a number of small princely states retained local rulers who recognized British authority. The Punjab with its rich farmlands became one of the most important colonial assets. Lahore was a noted center of learning and culture, and Rawalpindi became an important military installation. Most Punjabis supported the British during World War I, providing men and resources to the war effort even though the Punjab remained a source of anti colonial activities. Disturbances in the region increased as the war continued. At the end of the war, high casualty rates, heavy taxation, inflation, and a widespread influenza epidemic disrupted Punjabi society. In 1919 a British officer ordered his troops to fire on a crowd of demonstrators, mostly Sikhs in Amritsar. The Jallianwala massacre fueled the indian independence movement. Nationalists declared the independence of India from Lahore in 1930 but were quickly suppressed. When the Second World War broke out, nationalism in British India had already divided into religious movements. Many Sikhs and other minorities supported the Hindus, who promised a secular multicultural and multireligious society, and Muslim leaders in Lahore passed a resolution to work for a Muslim Pakistan, making the Punjab region a center of growing conflict between Indian and Pakistani nationalists. At the end of the war, the British granted separate independence to India and Pakistan, setting off massive communal violence as Muslims fled to Pakistan and Hindu and Sikh Punjabis fled east to India.

The British Raj had major political, cultural, philosophical, and literary consequences in the Punjab, including the establishment of a new system of education. During the independence movement, many Punjabis played a significant role, including Madan Lal Dhingra, Sukhdev Thapar, Ajit Singh Sandhu, Bhagat Singh, Udham Singh, Kartar Singh Sarabha, Bhai Parmanand, Choudhry Rahmat Ali, and Lala Lajpat Rai. At the time of partition in 1947, the province was split into East and West Punjab. East Punjab (48%) became part of India, while West Punjab (52%) became part of Pakistan. The Punjab bore the brunt of the civil unrest following partition, with casualties estimated to be in the millions.

Another major consequence of partition was the sudden shift towards religious homogeneity occurred in all districts across Punjab owing to the new international border that cut through the province. This rapid demographic shift was primarily due to wide scale migration but also caused by large-scale religious cleansing riots which were witnessed across the region at the time. According to historical demographer Tim Dyson, in the eastern regions of Punjab that ultimately became Indian Punjab following independence, districts that were 66% Hindu in 1941 became 80% Hindu in 1951; those that were 20% Sikh became 50% Sikh in 1951. Conversely, in the western regions of Punjab that ultimately became Pakistani Punjab, all districts became almost exclusively Muslim by 1951.

Geography

The geographical definition of the term "Punjab" has changed over time. In the 16th century Mughal Empire it referred to a relatively smaller area between the Indus and the Sutlej rivers.

Sikh empire

The Sikh Empire spanned a total of over 200,000 sq mi (520,000 km) at its zenith.

The Punjab was a region straddling India and the Afghan Durrani Empire. The following modern-day political divisions made up the historical Punjab region during the Sikh Empire:

- Punjab region, to Mithankot in the south

- Punjab, Pakistan, excluding Bahawalpur State

- Punjab, India, south to areas just across the Sutlej river

- Himachal Pradesh, India, south to areas just across the Sutlej river

- Jammu Division, Jammu and Kashmir, India and Pakistan (1808–1846)

- Kashmir, from 5 July 1819 to 15 March 1846, India/Pakistan/China

- Kashmir Valley, India from 1819 to 1846

- Gilgit, Gilgit–Baltistan, Pakistan, from 1842 to 1846

- Ladakh, India 1834–1846

- Khyber Pass, Pakistan/Afghanistan

- Peshawar, Pakistan (taken in 1818, retaken in 1834)

- Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas, Pakistan (documented from Hazara (taken in 1818, again in 1836 to Bannu)

- Parts of Western Tibet, China (briefly in 1841, to Taklakot),

After Ranjit Singh's death in 1839, the empire was severely weakened by internal divisions and political mismanagement. This opportunity was used by the East India Company to launch the First and Second Anglo-Sikh Wars. The country was finally annexed and dissolved at the end of the Second Anglo-Sikh War in 1849 into separate princely states and the province of Punjab. Eventually, a Lieutenant Governorship was formed in Lahore as a direct representative of the Crown.

Punjab (British India)

See also: Punjab Province (British India)In British India, until the Partition of India in 1947, the Punjab Province was geographically a triangular tract of country of which the Indus River and its tributary the Sutlej formed the two sides up to their confluence, the base of the triangle in the north being the Lower Himalayan Range between those two rivers. Moreover, the province as constituted under British rule also included a large tract outside these boundaries. Along the northern border, Himalayan ranges divided it from Kashmir and Tibet. On the west it was separated from the North-West Frontier Province by the Indus, until it reached the border of Dera Ghazi Khan District, which was divided from Baluchistan by the Sulaiman Range. To the south lay Sindh and Rajputana, while on the east the rivers Jumna and Tons separated it from the United Provinces. In total Punjab had an area of approximately 357 000 km square about the same size as modern day Germany, being one of the largest provinces of the British Raj.

It encompassed the present day Indian states of Punjab, Haryana, Chandigarh, Delhi, and some parts of Himachal Pradesh which were merged with Punjab by the British for administrative purposes (but excluding the former princely states which were later combined into the Patiala and East Punjab States Union) and the Pakistani regions of the Punjab, Islamabad Capital Territory and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

In 1901 the frontier districts beyond the Indus were separated from Punjab and made into a new province: the North-West Frontier Province. Subsequently, Punjab was divided into four natural geographical divisions by colonial officials on the decadal census data:

- Indo-Gangetic Plain West geographical division (including Hisar district, Loharu State, Rohtak district, Dujana State, Gurgaon district, Pataudi State, Delhi, Karnal district, Jalandhar district, Kapurthala State, Ludhiana district, Malerkotla State, Firozpur district, Faridkot State, Patiala State, Jind State, Nabha State, Lahore District, Amritsar district, Gujranwala District, and Sheikhupura district);

- Himalayan geographical division (including Nahan State, Simla District, Simla Hill States, Kangra district, Mandi State, Suket State, and Chamba State);

- Sub-Himalayan geographical division (including Ambala district, Kalsia State, Hoshiarpur district, Gurdaspur district, Sialkot District, Gujrat District, Jhelum District, Rawalpindi District, and Attock District;

- North-West Dry Area geographical division (including Montgomery District, Shahpur District, Mianwali District, Lyallpur District, Jhang District, Multan District, Bahawalpur State, Muzaffargarh District, and Dera Ghazi Khan District).

Partition of British Punjab

The struggle for Indian independence witnessed competing and conflicting interests in the Punjab. The landed elites of the Muslim, Hindu and Sikh communities had loyally collaborated with the British since annexation, supported the Unionist Party and were hostile to the Congress party–led independence movement. Amongst the peasantry and urban middle classes, the Hindus were the most active National Congress supporters, the Sikhs flocked to the Akali movement whilst the Muslims eventually supported the Muslim League.

Since the partition of the sub-continent had been decided, special meetings of the Western and Eastern Section of the Legislative Assembly were held on 23 June 1947 to decide whether or not the Province of the Punjab be partitioned. After voting on both sides, partition was decided and the existing Punjab Legislative Assembly was also divided into West Punjab Legislative Assembly and the East Punjab Legislative Assembly. This last Assembly before independence, held its last sitting on 4 July 1947.

Major cities

Main article: List of cities in the Punjab region by populationHistorically, Lahore has been the capital of the Punjab region and continues to be the most populous city in the region, with a population of 11 million for the city proper. Faisalabad is the 2nd most populous city and largest industrial hub in this region. Other major cities are Rawalpindi, Gujranwala, Multan, Ludhiana, Amritsar, Jalandhar, and Chandigarh are the other cities in Punjab with a city-proper population of over a million.

Climate

The climate has significant impact on the economy of Punjab, particularly for agriculture in the region. Climate is not uniform over the whole region, as the sections adjacent to the Himalayas generally receive heavier rainfall than those at a distance.

There are three main seasons and two transitional periods. During the hot season from mid-April to the end of June, the temperature may reach 49 °C (120 °F). The monsoon season, from July to September, is a period of heavy rainfall, providing water for crops in addition to the supply from canals and irrigation systems. The transitional period after the monsoon is cool and mild, leading to the winter season, when the temperature in January falls to 5 °C (41 °F) at night and 12 °C (54 °F) by day. During the transitional period from winter to the hot season, sudden hailstorms and heavy showers may occur, causing damage to crops.

Western Punjab

| Climate data for Islamabad (1991-2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 25.0 (77.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

37.0 (98.6) |

44.0 (111.2) |

45.6 (114.1) |

48.6 (119.5) |

45.0 (113.0) |

42.0 (107.6) |

38.1 (100.6) |

38.0 (100.4) |

32.2 (90.0) |

28.3 (82.9) |

48.6 (119.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 17.7 (63.9) |

20.0 (68.0) |

24.8 (76.6) |

30.6 (87.1) |

36.1 (97.0) |

38.3 (100.9) |

35.4 (95.7) |

33.9 (93.0) |

33.4 (92.1) |

30.9 (87.6) |

25.4 (77.7) |

20.4 (68.7) |

28.9 (84.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.7 (51.3) |

13.4 (56.1) |

18.1 (64.6) |

23.6 (74.5) |

28.7 (83.7) |

31.4 (88.5) |

30.1 (86.2) |

29.1 (84.4) |

27.6 (81.7) |

23.3 (73.9) |

17.3 (63.1) |

12.5 (54.5) |

22.2 (71.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.2 (36.0) |

6.8 (44.2) |

11.4 (52.5) |

16.6 (61.9) |

21.5 (70.7) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.9 (76.8) |

24.2 (75.6) |

21.7 (71.1) |

15.6 (60.1) |

9.1 (48.4) |

3.4 (38.1) |

15.2 (59.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10 (14) |

−8 (18) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

1.6 (34.9) |

5.5 (41.9) |

13 (55) |

15.2 (59.4) |

14.5 (58.1) |

13.3 (55.9) |

5.7 (42.3) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 55.2 (2.17) |

99.5 (3.92) |

180.5 (7.11) |

120.8 (4.76) |

39.9 (1.57) |

78.4 (3.09) |

310.6 (12.23) |

317.0 (12.48) |

135.4 (5.33) |

34.4 (1.35) |

17.7 (0.70) |

25.9 (1.02) |

1,415.3 (55.73) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 4.7 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 5.2 | 6.0 | 12.3 | 11.9 | 6.4 | 2.9 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 79.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 195.7 | 187.1 | 202.3 | 252.4 | 319.0 | 300.1 | 264.4 | 250.7 | 262.2 | 275.5 | 247.9 | 195 | 2,952.3 |

| Source 1: NOAA (sun, 1961-1990) | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: PMD (extremes) | |||||||||||||

Central Punjab

| Climate data for Lahore (1991-2020, extremes 1931-2018) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 27.8 (82.0) |

33.3 (91.9) |

37.8 (100.0) |

46.1 (115.0) |

48.3 (118.9) |

47.2 (117.0) |

46.1 (115.0) |

42.8 (109.0) |

41.7 (107.1) |

40.6 (105.1) |

35.0 (95.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

48.3 (118.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 18.4 (65.1) |

22.2 (72.0) |

27.5 (81.5) |

34.2 (93.6) |

38.9 (102.0) |

38.9 (102.0) |

35.6 (96.1) |

34.7 (94.5) |

34.4 (93.9) |

32.4 (90.3) |

27.1 (80.8) |

21.4 (70.5) |

30.5 (86.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 13.1 (55.6) |

16.5 (61.7) |

21.6 (70.9) |

27.7 (81.9) |

32.3 (90.1) |

33.2 (91.8) |

31.3 (88.3) |

30.8 (87.4) |

29.9 (85.8) |

26.3 (79.3) |

20.4 (68.7) |

15.1 (59.2) |

24.9 (76.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 7.6 (45.7) |

10.8 (51.4) |

15.7 (60.3) |

21.1 (70.0) |

25.6 (78.1) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.1 (80.8) |

26.9 (80.4) |

25.3 (77.5) |

20.1 (68.2) |

13.7 (56.7) |

8.8 (47.8) |

19.2 (66.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −2.2 (28.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

2.8 (37.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

14.0 (57.2) |

17.8 (64.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

19.0 (66.2) |

16.7 (62.1) |

8.3 (46.9) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 21.9 (0.86) |

39.5 (1.56) |

43.5 (1.71) |

25.5 (1.00) |

26.7 (1.05) |

84.8 (3.34) |

195.6 (7.70) |

184.1 (7.25) |

88.6 (3.49) |

13.3 (0.52) |

6.9 (0.27) |

16.8 (0.66) |

747.2 (29.41) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 2.5 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 5.0 | 9.1 | 8.7 | 4.9 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 47.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 218.8 | 215.0 | 245.8 | 256.1 | 308.3 | 269.0 | 227.5 | 234.9 | 265.6 | 290.0 | 229.6 | 222.9 | 2,983.5 |

| Source 1: NOAA (sun, 1961-1990) | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: PMD | |||||||||||||

Eastern Punjab

| Climate data for Chandigarh (1991-2020, extremes 1954–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 27.7 (81.9) |

32.8 (91.0) |

37.8 (100.0) |

43.3 (109.9) |

46.0 (114.8) |

45.3 (113.5) |

42.0 (107.6) |

39.0 (102.2) |

37.5 (99.5) |

37.0 (98.6) |

34.0 (93.2) |

28.5 (83.3) |

46.0 (114.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 18.2 (64.8) |

22.6 (72.7) |

28.0 (82.4) |

34.6 (94.3) |

38.6 (101.5) |

37.7 (99.9) |

34.1 (93.4) |

33.2 (91.8) |

32.9 (91.2) |

32.0 (89.6) |

27.0 (80.6) |

22.1 (71.8) |

29.9 (85.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 7.2 (45.0) |

10.4 (50.7) |

14.7 (58.5) |

20.3 (68.5) |

24.7 (76.5) |

26.7 (80.1) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.2 (79.2) |

24.4 (75.9) |

18.4 (65.1) |

12.3 (54.1) |

8.0 (46.4) |

18.2 (64.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.0 (32.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

4.2 (39.6) |

7.8 (46.0) |

13.4 (56.1) |

14.8 (58.6) |

14.2 (57.6) |

17.2 (63.0) |

14.3 (57.7) |

9.4 (48.9) |

3.7 (38.7) |

0.0 (32.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 37.8 (1.49) |

37.3 (1.47) |

27.4 (1.08) |

17.5 (0.69) |

26.8 (1.06) |

146.7 (5.78) |

275.6 (10.85) |

273.0 (10.75) |

154.6 (6.09) |

14.2 (0.56) |

5.2 (0.20) |

22.3 (0.88) |

1,038.4 (40.88) |

| Average rainy days | 2.3 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 6.5 | 9.8 | 11.1 | 6.0 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 47.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 17:30 IST) | 47 | 42 | 34 | 23 | 23 | 39 | 62 | 70 | 59 | 40 | 40 | 46 | 44 |

| Source: India Meteorological Department

| |||||||||||||

Demographics

Main article: PunjabisLanguages

See also: Punjab, Pakistan § Languages; and Punjabi dialects and languages

The major language is Punjabi, which is written in India with the Gurmukhi script, and in Pakistan using the Shahmukhi script. The Punjabi language has official status and is widely used in education and administration in Indian Punjab, whereas in Pakistani Punjab these roles are instead fulfilled by the Urdu language.

Several languages closely related to Punjabi are spoken in the periphery of the region. Dogri, Kangri, and other western Pahari dialects are spoken in the north-central and northeastern peripheries of the region, while Bagri is spoken in south-central and southeastern sections. Meanwhile, Saraiki is generally spoken across a wide belt covering the southwest, while in the northwest there are large pockets containing speakers of Hindko and Pothwari.

| Language | Percentage |

|---|---|

| 1911 | |

| Punjabi | 75.93% |

| Western Hindi | 15.82% |

| Western Pahari | 4.11% |

| Rajasthani | 3.0% |

| Balochi | 0.29% |

| Pashto | 0.28% |

| English | 0.15% |

| Other | 0.42% |

Religions

Main article: Religion in the PunjabBackground

The Punjabi people first practiced Hinduism, the oldest recorded religion in the Punjab region. The historical Vedic religion constituted the religious ideas and practices in the Punjab during the Vedic period (1500–500 BCE), centered primarily in the worship of Indra. The bulk of the Rigveda was composed in the Punjab region between circa 1500 and 1200 BC, while later Vedic scriptures were composed more eastwards, between the Yamuna and Ganges rivers. An ancient Indian law book called the Manusmriti, developed by Brahmin Hindu priests, shaped Punjabi religious life from 200 BC onward.

Later, the spread of Buddhisim and Jainism in the Indian subcontinent saw the growth of Buddhism and Jainism in the Punjab. Islam was introduced via southern Punjab in the 8th century, becoming the majority by the 16th century, via local conversion. There was a small Jain community left in Punjab by the 16th century, while the Buddhist community had largely disappeared by the turn of the 10th century. The region became predominantly Muslim due to missionary Sufi saints whose dargahs dot the landscape of the Punjab region.

The rise of Sikhism in the 1700s saw some Punjabis, both Hindu and Muslim, accepting the new Sikh faith. A number of Punjabis during the colonial period of India became Christians, with all of these religions characterizing the religious diversity now found in the Punjab region.

Colonial era

Main article: Religion in the Punjab § SubregionsA number of Punjabis during the colonial period of India became Christians, with all of these religions characterizing the religious diversity now found in the Punjab region. Additionally during the colonial era, the practice of religious syncretism among Punjabi Muslims and Punjabi Hindus was noted and documented by officials in census reports:

"In other parts of the Province, too, traces of Hindu festivals are noticeable among the Muhammadans. In the western Punjab, Baisakhi, the new year's day of the Hindus, is celebrated as an agricultural festival, by all Muhammadans, by racing bullocks yoked to the well gear, with the beat of tom-toms, and large crowds gather to witness the show, The race is called Baisakhi and is a favourite pastime in the well-irrigated tracts. Then the processions of Tazias, in Muharram, with the accompaniment of tom-toms, fencing parties and bands playing on flutes and other musical instruments (which is disapproved by the orthodox Muhammadans) and the establishment of Sabils (shelters where water and sharbat are served out) are clearly influenced by similar practices at Hindu festivals, while the illuminations on occasions like the Chiraghan fair of Shalamar (Lahore) are no doubt practices answering to the holiday-making instinct of the converted Hindus."

— Excerpts from the Census of India (Punjab Province), 1911 AD

"Besides actual conversion, Islam has had a considerable influence on the Hindu religion. The sects of reformers based on a revolt from the orthodoxy of Varnashrama Dharma were obviously the outcome of the knowledge that a different religion could produce equally pious and right thinking men. Laxity in social restrictions also appeared simultaneously in various degrees and certain customs were assimilated to those of the Muhammadans. On the other hand the miraculous powers of Muhammadan saints were enough to attract the saint worshiping Hindus, to allegiance, if not to a total change of faith... The Shamsis are believers in Shah Shamas Tabrez of Multan, and follow the Imam, for the time being, of the Ismailia sect of Shias... they belong mostly to the Sunar caste and their connection with the sect is kept a secret, like Freemasonry. They pass as ordinary Hindus, but their devotion to the Imam is very strong."

| Religious group |

Population % 1881 |

Population % 1891 |

Population % 1901 |

Population % 1911 |

Population % 1921 |

Population % 1931 |

Population % 1941 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islam | 47.6% | 47.8% | 49.6% | 51.1% | 51.1% | 52.4% | 53.2% |

| Hinduism | 43.8% | 43.6% | 41.3% | 35.8% | 35.1% | 31.7% | 30.1% |

| Sikhism | 8.2% | 8.2% | 8.6% | 12.1% | 12.4% | 14.3% | 14.9% |

| Christianity | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.8% | 1.3% | 1.5% | 1.5% |

| Other religions / No religion | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.3% |

Territory comprises the contemporary subdivisions of Punjab, Pakistan and Islamabad Capital Territory. |

Territory comprises the contemporary subdivisions of Punjab, India, Chandigarh, Haryana, and Himachal Pradesh. |

|

| Religion | Percentage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1941 | |

| Hinduism |

43.79% | 42.62% | 41.37% | 36.04% | 33.54% |

| Islam |

37.36% | 37.81% | 38.0% | 39.72% | 40.41% |

| Sikhism |

18.35% | 18.73% | 19.10% | 21.88% | 23.11% |

| Christianity |

0.18% | 0.51% | 1.23% | 1.54% | 1.60% |

| Jainism |

0.32% | 0.33% | 0.29% | 0.27% | 0.28% |

The Indo−Gangetic Plain West geographical division included Hisar district, Loharu State, Rohtak district, Dujana State, Gurgaon district, Pataudi State, Delhi, Karnal district, Jalandhar district, Kapurthala State, Ludhiana district, Malerkotla State, Firozpur district, Faridkot State, Patiala State, Jind State, Nabha State, Lahore District, Amritsar district, Gujranwala District, and Sheikhupura District.

| Religion | Percentage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1941 | |

| Hinduism |

94.60% | 94.53% | 94.50% | 94.25% | 94.35% |

| Islam |

4.53% | 4.30% | 4.45% | 4.52% | 4.27% |

| Sikhism |

0.23% | 0.46% | 0.44% | 0.49% | 0.60% |

| Christianity |

0.20% | 0.26% | 0.26% | 0.14% | 0.10% |

| Jainism |

0.03% | 0.02% | 0.02% | 0.02% | 0.03% |

The Himalayan geographical division included Sirmoor State, Simla District, Simla Hill States, Bilaspur State, Kangra district, Mandi State, Suket State, and Chamba State.

| Religion | Percentage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1941 | |

| Islam |

60.62% | 61.19% | 61.44% | 61.99% | 62.29% |

| Hinduism |

33.09% | 27.36% | 26.66% | 22.85% | 21.98% |

| Sikhism |

5.68% | 9.74% | 9.77% | 11.65% | 11.89% |

| Christianity |

0.48% | 1.59% | 2.01% | 2.05% | 1.74% |

| Jainism |

0.12% | 0.12% | 0.12% | 0.11% | 0.12% |

The Sub−Himalayan geographical division included Ambala district, Kalsia State, Hoshiarpur district, Gurdaspur district, Sialkot District, Gujrat District, Jhelum District, Rawalpindi District, and Attock District.

| Religion | Percentage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1941 | |

| Islam |

79.01% | 80.00% | 78.95% | 78.22% | 77.85% |

| Hinduism |

17.84% | 13.58% | 14.23% | 12.80% | 13.21% |

| Sikhism |

2.91% | 5.62% | 5.64% | 6.73% | 6.74% |

| Christianity |

0.23% | 0.79% | 1.17% | 1.18% | 1.17% |

| Jainism |

0.01% | 0.01% | 0.01% | 0.01% | 0.01% |

The North−West Dry Area geographical division included Montgomery District, Shahpur District, Mianwali District, Lyallpur District, Jhang District, Multan District, Bahawalpur State, Muzaffargarh District, Dera Ghazi Khan District, and the Biloch Trans–Frontier Tract.

Post-partition

In the present-day, the vast majority of Pakistani Punjabis are Sunni Muslim by faith, but also include significant minority faiths, such as Shia Muslims, Ahmadi Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs and Christians.

Sikhism, founded by Guru Nanak is the main religion practised in the post-1966 Indian Punjab state. About 57.7% of the population of Punjab state is Sikh, 38.5% is Hindu, with the remaining population including Muslims, Christians, and Jains. Punjab state contains the holy Sikh cities of Amritsar, Anandpur Sahib, Tarn Taran Sahib, Fatehgarh Sahib and Chamkaur Sahib.

The Punjab was home to several Sufi saints, and Sufism is well established in the region. Also, Kirpal Singh revered the Sikh Gurus as saints.

| Religious group |

Punjab Region |

Punjab (Pakistan) |

Punjab (India) |

Haryana | Delhi | Himachal Pradesh |

Islamabad | Chandigarh | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Population |

Percentage | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Islam |

114,130,322 | 60.13% | 107,541,602 | 97.77% | 535,489 | 1.93% | 1,781,342 | 7.03% | 2,158,684 | 12.86% | 149,881 | 2.18% | 1,911,877 | 95.43% | 51,447 | 4.87% |

| Hinduism |

54,159,083 | 28.54% | 211,641 | 0.19% | 10,678,138 | 38.49% | 22,171,128 | 87.46% | 13,712,100 | 81.68% | 6,532,765 | 95.17% | 737 | 0.04% | 852,574 | 80.78% |

| Sikhism |

18,037,312 | 9.5% | — | — | 16,004,754 | 57.69% | 1,243,752 | 4.91% | 570,581 | 3.4% | 79,896 | 1.16% | — | — | 138,329 | 13.11% |

| Christianity |

2,715,952 | 1.43% | 2,063,063 | 1.88% | 348,230 | 1.26% | 50,353 | 0.2% | 146,093 | 0.87% | 12,646 | 0.18% | 86,847 | 4.34% | 8,720 | 0.83% |

| Jainism |

267,649 | 0.14% | — | — | 45,040 | 0.16% | 52,613 | 0.21% | 166,231 | 0.99% | 1,805 | 0.03% | — | — | 1,960 | 0.19% |

| Ahmadiyya |

160,759 | 0.08% | 158,021 | 0.14% | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2,738 | 0.14% | — | — |

| Buddhism |

139,019 | 0.07% | — | — | 33,237 | 0.12% | 7,514 | 0.03% | 18,449 | 0.11% | 78,659 | 1.15% | — | — | 1,160 | 0.11% |

| Others | 185,720 | 0.1% | 15,328 | 0.01% | 98,450 | 0.35% | 44,760 | 0.18% | 15,803 | 0.09% | 8,950 | 0.13% | 1,169 | 0.06% | 1,260 | 0.12% |

| Total population | 189,795,816 | 100% | 109,989,655 | 100% | 27,743,338 | 100% | 25,351,462 | 100% | 16,787,941 | 100% | 6,864,602 | 100% | 2,003,368 | 100% | 1,055,450 | 100% |

Castes and tribes

The Punjab region is diverse. As seen in historic census data taken in the colonial era, many castes, subcastes & tribes all formed parts of the various ethnic groups in Punjab Province, contemporarily known as Punjabis, Saraikis, Haryanvis, Hindkowans, Dogras, Paharis, and more.

| Caste or Tribe | 1881 | 1891 | 1901 | 1911 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Jat | 4,167,000 | 20.03% | 4,430,000 | 19.33% | 4,942,000 | 20.28% | 4,957,000 | 20.83% |

| Rajput | 1,662,000 | 7.99% | 1,759,000 | 7.68% | 1,798,000 | 7.38% | 1,635,000 | 6.87% |