| Revision as of 06:36, 17 January 2006 editCtalmageblack (talk | contribs)5 edits →Biology← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 11:51, 19 October 2024 edit undoGünniX (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users311,179 editsm unbalanced bracketsTag: AWB | ||

| (296 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Chemical process of joining two molecular entities by bonds of any kind}} | |||

| ], or common table sugar, is composed of glucose and fructose.]] | |||

| {{Redirect|Dimer (chemistry)|other uses|Dimer (disambiguation)}} | |||

| ==Chemistry== | |||

| {{refimprove|date=April 2009}} | |||

| In ], a '''dimer''' refers to a ] composed of two similar subunits or monomers linked together. It is a special case of a ]. It can refer to halide chemistry, involving halogen bonding. Its more common usage refers to dimers as certain types of ]: ], for example, is a dimer of a ] molecule and a ] molecule. | |||

| In ], '''dimerization''' is the process of joining two identical or similar ] by ]. The resulting bonds can be either strong or weak. Many symmetrical ] are described as '''dimers''', even when the ] is unknown or highly unstable.<ref>{{cite web |title=Dimerization |url=https://goldbook.iupac.org/terms/view/D01744}}</ref> | |||

| A '''physical dimer''' is a term that designates the case where intermolecular interaction brings two identical molecules closer together than other molecules. There are no ]s between the physical dimer molecules. ] is such a case where ]s provide the interaction. | |||

| The term ''homodimer'' is used when the two subunits are identical (e.g. A–A) and ''heterodimer'' when they are not (e.g. A–B). The reverse of dimerization is often called ]. When two oppositely-charged ]s associate into dimers, they are referred to as ''Bjerrum pairs'',<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Adar|first1=Ram M.|last2=Markovich|first2=Tomer|last3=Andelman|first3=David|date=2017-05-17|title=Bjerrum pairs in ionic solutions: A Poisson-Boltzmann approach|journal=The Journal of Chemical Physics|volume=146|issue=19|pages=194904|doi=10.1063/1.4982885|pmid=28527430|issn=0021-9606|arxiv=1702.04853|bibcode=2017JChPh.146s4904A|s2cid=12227786}}</ref> after Danish chemist ]. | |||

| ==Biology== | |||

| == Noncovalent dimers == | |||

| In ], particularly molecular and cellular biology, dimers are most often observed in signaling. They are crucial to understanding chemical reactions in biochemistry as well. In this case, a dimer is a ] complex made up of two subunits that are not necessarily covalently linked. In fact, they may initially be ] proteins. These monomers will dimerize, or join together, usually upon the binding of a signal to the receptor of each monomer. These signals can be a growth factor, a phosphate group from ] (usually through a kinase protein), or a ]. | |||

| ]s are often found in the vapour phase.]] | |||

| ] ]s form dimers by hydrogen bonding of the acidic hydrogen and the carbonyl oxygen. For example, ] forms a dimer in the gas phase, where the monomer units are held together by ]s.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Karle |first1=J. |last2=Brockway |first2=L. O. |date=1944 |title=An Electron Diffraction Investigation of the Monomers and Dimers of Formic, Acetic and Trifluoroacetic Acids and the Dimer of Deuterium Acetate 1 |url=https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/ja01232a022 |journal=Journal of the American Chemical Society |language=en |volume=66 |issue=4 |pages=574–584 |doi=10.1021/ja01232a022 |issn=0002-7863}}</ref> Many OH-containing molecules form dimers, e.g. the ]. | |||

| ] and ]es are ] structures with a short lifetime. For example, ] do not form stable dimers, but they do form the ] Ar<sub>2</sub>*, Kr<sub>2</sub>* and Xe<sub>2</sub>* under high pressure and electrical stimulation.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Birks |first=J B |date=1975-08-01 |title=Excimers |url=https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/0034-4885/38/8/001 |journal=Reports on Progress in Physics |volume=38 |issue=8 |pages=903–974 |doi=10.1088/0034-4885/38/8/001 |s2cid=240065177 |issn=0034-4885}}</ref> | |||

| An example of this dimerizing activity involves the RAS-independent receptor tyrosine ] that activates Phospholipase C-gamma. When a growth factor binds to two monomeric Epithelial Growth Factor (EGF) receptor (or Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF) receptor), the receptors will dimerize and phosphorylate each other at the SH2 binding domains on the cytoplasmic portion of the receptor. The Phospholipase C-gamma isoform has SH2 domains that bind to the newly phosphorylated SH2 binding domain of the dimerized growth factor receptors. Upon binding, the Phospholipase C-gamma will be activated, and will be close to the membrane phospholipid that it is designed to cleave. | |||

| == Covalent dimers == | |||

| In a '''homodimer''' the two subunits are identical, and in a '''heterodimer''' they differ (though they are often still very similar in structure). | |||

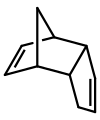

| ] gives dicyclopentadiene, although this might not be readily apparent on initial inspection. This dimerization is reversible]] | |||

| ] dimers are often formed by the reaction of two identical compounds e.g.: {{chem2|2A -> A\sA}}. In this example, ] "A" is said to dimerize to give the dimer "{{chem2|A\sA}}". | |||

| ⚫ | == See also == | ||

| ] is an asymmetrical dimer of two ] molecules that have reacted in a ] to give the product. Upon heating, it "cracks" (undergoes a retro-Diels-Alder reaction) to give identical monomers: | |||

| ⚫ | * |

||

| :<chem>C10H12 -> 2 C5H6</chem> | |||

| ⚫ | * |

||

| Many nonmetallic elements occur as dimers: ], ], ], and the ]s ], ], ] and ]. Some metals form a proportion of dimers in their vapour phase: ] ({{chem2|Li2}}), ] ({{chem2|Na2}}), ] ({{chem2|K2}}), ] ({{chem2|Rb2}}) and ] ({{chem2|Cs2}}). Such elemental dimers are ] ]s. | |||

| ==Polymer chemistry== | |||

| In the context of ]s, "dimer" also refers to the ] 2, regardless of the stoichiometry or ]s. | |||

| One case where this is applicable is with ]s. For example, ] is a dimer of ], even though the formation reaction produces ]: | |||

| : <chem>2 C6H12O6 -> C12H22O11 + H2O</chem> | |||

| Here, the resulting dimer has a stoichiometry different from the initial pair of monomers. | |||

| Disaccharides need not be composed of the same ]s to be considered dimers. An example is ], a dimer of ] and glucose, which follows the same reaction equation as presented above. | |||

| Amino acids can also form dimers, which are called ]s. An example is ], consisting of two ] molecules joined by a ]. Other examples include ] and ]. | |||

| == Inorganic and organometallic dimers == | |||

| Many molecules and ions are described as dimers, even when the monomer is elusive. | |||

| === Boranes === | |||

| ] | |||

| ] (B<sub>2</sub>H<sub>6</sub>) is an dimer of ], which is elusive and rarely observed. Almost all compounds of the type R2BH exist as dimers.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Shriver |first=Duward |title=Inorganic Chemistry |publisher=W.H. Freeman and Company |year=2014 |isbn=9781429299060 |edition=6th |pages=306–307 |language=English}}</ref> | |||

| ===Organoaluminium compounds=== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] can exist as either monomers or dimers, depending on the ] of the groups attached. For example, ] exists as a dimer, but trimesitylaluminium adopts a monomeric structure.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last=Shriver |first=Duward |title=Inorganic Chemistry |publisher=W.H. Freeman and Company |year=2014 |isbn=9781429299060 |edition=6th |pages=377–378 |language=English}}</ref> | |||

| ===Organochromium compounds=== | |||

| Cyclopentadienylchromium tricarbonyl dimer exists in measureable equilibrium quantities with the monometallic radical {{chem2|(C5H5)Cr(CO)3}}.<ref>{{cite journal | doi = 10.1021/ja00810a019 | issue = 5| pages = 749–754| title = Unusual structural and magnetic resonance properties of dicyclopentadienylhexacarbonyldichromium| journal = Journal of the American Chemical Society| volume = 96| year = 1974| last1 = Adams| first1 = Richard D.| last2 = Collins| first2 = Douglas E.| last3 = Cotton| first3 = F. Albert}}</ref> | |||

| == Biochemical dimers == | |||

| === Pyrimidine dimers === | |||

| ] (also known as thymine dimers) are formed by a ] from pyrimidine ]s when exposed to ultraviolet light.<ref name=":0"/> This cross-linking causes ], which can be ], causing ]s.<ref name=":0" /> When ]s are present, they can block ]s, decreasing DNA functionality until it is repaired.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| === Protein dimers === | |||

| ] | |||

| ]s arise from the interaction between two ]s which can interact further to form larger and more complex ]s.<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal |last1=Marianayagam |first1=Neelan J. |last2=Sunde |first2=Margaret |last3=Matthews |first3=Jacqueline M. |date=2004 |title=The power of two: protein dimerization in biology |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2004.09.006 |journal=Trends in Biochemical Sciences |volume=29 |issue=11 |pages=618–625 |doi=10.1016/j.tibs.2004.09.006 |pmid=15501681 |issn=0968-0004}}</ref> For example, ] is formed by the dimerization of ] and ] and this dimer can then ] further to make ]s.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Cooper |first=Geoffrey M. |date=2000 |title=Microtubules |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9932/ |journal=The Cell: A Molecular Approach. 2nd Edition |language=en}}</ref> For symmetric proteins, the larger protein complex can be broken down into smaller identical ]s, which then dimerize to decrease the genetic code required to make the functional protein.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

| === G protein-coupled receptors === | |||

| As the largest and most diverse family of ] within the human genome, ]s (GPCR) have been studied extensively, with recent studies supporting their ability to form dimers.<ref>{{Citation |last1=Faron-Górecka |first1=Agata |title=Chapter 10 - Understanding GPCR dimerization |date=2019-01-01 |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0091679X18301080 |journal=Methods in Cell Biology |volume=149 |pages=155–178 |editor-last=Shukla |editor-first=Arun K. |series=G Protein-Coupled Receptors, Part B |publisher=Academic Press |language=en |doi=10.1016/bs.mcb.2018.08.005 |access-date=2022-10-27 |last2=Szlachta |first2=Marta |last3=Kolasa |first3=Magdalena |last4=Solich |first4=Joanna |last5=Górecki |first5=Andrzej |last6=Kuśmider |first6=Maciej |last7=Żurawek |first7=Dariusz |last8=Dziedzicka-Wasylewska |first8=Marta|pmid=30616817 |isbn=9780128151075 |s2cid=58577416 }}</ref> GPCR dimers include both homodimers and heterodimers formed from related members of the GPCR family.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Rios |first1=C. D. |last2=Jordan |first2=B. A. |last3=Gomes |first3=I. |last4=Devi |first4=L. A. |date=2001-11-01 |title=G-protein-coupled receptor dimerization: modulation of receptor function |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0163725801001607 |journal=Pharmacology & Therapeutics |language=en |volume=92 |issue=2 |pages=71–87 |doi=10.1016/S0163-7258(01)00160-7 |pmid=11916530 |issn=0163-7258}}</ref> While not all, some GPCRs require dimerization to function, such as ]-receptor, emphasizing the importance of dimers in biological systems.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Lohse |first=Martin J |date=2010-02-01 |title=Dimerization in GPCR mobility and signaling |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1471489209001672 |journal=Current Opinion in Pharmacology |series=GPCR |language=en |volume=10 |issue=1 |pages=53–58 |doi=10.1016/j.coph.2009.10.007 |pmid=19910252 |issn=1471-4892}}</ref>] | |||

| === Receptor tyrosine kinase === | |||

| Much like for G protein-coupled receptors, dimerization is essential for ]s (RTK) to perform their function in ], affecting many different cellular processes.<ref name=":2">{{Cite journal |last=Hubbard |first=Stevan R |date=1999-04-01 |title=Structural analysis of receptor tyrosine kinases |journal=Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology |language=en |volume=71 |issue=3 |pages=343–358 |doi=10.1016/S0079-6107(98)00047-9 |pmid=10354703 |issn=0079-6107|doi-access=free }}</ref> RTKs typically exist as monomers, but undergo a ] upon ] binding, allowing them to dimerize with nearby RTKs.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Lemmon |first1=Mark A. |last2=Schlessinger |first2=Joseph |date=2010-06-25 |title=Cell Signaling by Receptor Tyrosine Kinases |journal=Cell |language=English |volume=141 |issue=7 |pages=1117–1134 |doi=10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.011 |issn=0092-8674 |pmc=2914105 |pmid=20602996}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Lemmon |first1=Mark A. |last2=Schlessinger |first2=Joseph |last3=Ferguson |first3=Kathryn M. |date=2014-04-01 |title=The EGFR Family: Not So Prototypical Receptor Tyrosine Kinases |journal=Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology |language=en |volume=6 |issue=4 |pages=a020768 |doi=10.1101/cshperspect.a020768 |issn=1943-0264 |pmid=24691965|pmc=3970421 |doi-access=free }}</ref> The dimerization activates the ]ic ] ] that are responsible for further ].<ref name=":2" /> | |||

| ⚫ | == See also == | ||

| {{Commons|Dimers}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| ⚫ | *] | ||

| *] | |||

| ⚫ | *] | ||

| == References == | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| * {{cite web | url=http://goldbook.iupac.org/D01744.html | title=IUPAC "Gold Book" definition | doi=10.1351/goldbook.D01744 | s2cid=242984652 | access-date=2024-07-11| doi-access=free }} | |||

| ] | |||

| <references/> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| {{biochem-stub}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{cellbio-stub}} | |||

Latest revision as of 11:51, 19 October 2024

Chemical process of joining two molecular entities by bonds of any kind "Dimer (chemistry)" redirects here. For other uses, see Dimer (disambiguation).| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Dimerization" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In chemistry, dimerization is the process of joining two identical or similar molecular entities by bonds. The resulting bonds can be either strong or weak. Many symmetrical chemical species are described as dimers, even when the monomer is unknown or highly unstable.

The term homodimer is used when the two subunits are identical (e.g. A–A) and heterodimer when they are not (e.g. A–B). The reverse of dimerization is often called dissociation. When two oppositely-charged ions associate into dimers, they are referred to as Bjerrum pairs, after Danish chemist Niels Bjerrum.

Noncovalent dimers

Anhydrous carboxylic acids form dimers by hydrogen bonding of the acidic hydrogen and the carbonyl oxygen. For example, acetic acid forms a dimer in the gas phase, where the monomer units are held together by hydrogen bonds. Many OH-containing molecules form dimers, e.g. the water dimer.

Excimers and exciplexes are excited structures with a short lifetime. For example, noble gases do not form stable dimers, but they do form the excimers Ar2*, Kr2* and Xe2* under high pressure and electrical stimulation.

Covalent dimers

Molecular dimers are often formed by the reaction of two identical compounds e.g.: 2A → A−A. In this example, monomer "A" is said to dimerize to give the dimer "A−A".

Dicyclopentadiene is an asymmetrical dimer of two cyclopentadiene molecules that have reacted in a Diels-Alder reaction to give the product. Upon heating, it "cracks" (undergoes a retro-Diels-Alder reaction) to give identical monomers:

Many nonmetallic elements occur as dimers: hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, and the halogens fluorine, chlorine, bromine and iodine. Some metals form a proportion of dimers in their vapour phase: dilithium (Li2), disodium (Na2), dipotassium (K2), dirubidium (Rb2) and dicaesium (Cs2). Such elemental dimers are homonuclear diatomic molecules.

Polymer chemistry

In the context of polymers, "dimer" also refers to the degree of polymerization 2, regardless of the stoichiometry or condensation reactions.

One case where this is applicable is with disaccharides. For example, cellobiose is a dimer of glucose, even though the formation reaction produces water:

Here, the resulting dimer has a stoichiometry different from the initial pair of monomers.

Disaccharides need not be composed of the same monosaccharides to be considered dimers. An example is sucrose, a dimer of fructose and glucose, which follows the same reaction equation as presented above.

Amino acids can also form dimers, which are called dipeptides. An example is glycylglycine, consisting of two glycine molecules joined by a peptide bond. Other examples include aspartame and carnosine.

Inorganic and organometallic dimers

Many molecules and ions are described as dimers, even when the monomer is elusive.

Boranes

Diborane (B2H6) is an dimer of borane, which is elusive and rarely observed. Almost all compounds of the type R2BH exist as dimers.

Organoaluminium compounds

Trialkylaluminium compounds can exist as either monomers or dimers, depending on the steric bulk of the groups attached. For example, trimethylaluminium exists as a dimer, but trimesitylaluminium adopts a monomeric structure.

Organochromium compounds

Cyclopentadienylchromium tricarbonyl dimer exists in measureable equilibrium quantities with the monometallic radical (C5H5)Cr(CO)3.

Biochemical dimers

Pyrimidine dimers

Pyrimidine dimers (also known as thymine dimers) are formed by a photochemical reaction from pyrimidine DNA bases when exposed to ultraviolet light. This cross-linking causes DNA mutations, which can be carcinogenic, causing skin cancers. When pyrimidine dimers are present, they can block polymerases, decreasing DNA functionality until it is repaired.

Protein dimers

Protein dimers arise from the interaction between two proteins which can interact further to form larger and more complex oligomers. For example, tubulin is formed by the dimerization of α-tubulin and β-tubulin and this dimer can then polymerize further to make microtubules. For symmetric proteins, the larger protein complex can be broken down into smaller identical protein subunits, which then dimerize to decrease the genetic code required to make the functional protein.

G protein-coupled receptors

As the largest and most diverse family of receptors within the human genome, G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) have been studied extensively, with recent studies supporting their ability to form dimers. GPCR dimers include both homodimers and heterodimers formed from related members of the GPCR family. While not all, some GPCRs require dimerization to function, such as GABAB-receptor, emphasizing the importance of dimers in biological systems.

Receptor tyrosine kinase

Much like for G protein-coupled receptors, dimerization is essential for receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK) to perform their function in signal transduction, affecting many different cellular processes. RTKs typically exist as monomers, but undergo a conformational change upon ligand binding, allowing them to dimerize with nearby RTKs. The dimerization activates the cytoplasmic kinase domains that are responsible for further signal transduction.

See also

References

- "IUPAC "Gold Book" definition". doi:10.1351/goldbook.D01744. S2CID 242984652. Retrieved 2024-07-11.

- "Dimerization".

- Adar, Ram M.; Markovich, Tomer; Andelman, David (2017-05-17). "Bjerrum pairs in ionic solutions: A Poisson-Boltzmann approach". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 146 (19): 194904. arXiv:1702.04853. Bibcode:2017JChPh.146s4904A. doi:10.1063/1.4982885. ISSN 0021-9606. PMID 28527430. S2CID 12227786.

- Karle, J.; Brockway, L. O. (1944). "An Electron Diffraction Investigation of the Monomers and Dimers of Formic, Acetic and Trifluoroacetic Acids and the Dimer of Deuterium Acetate 1". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 66 (4): 574–584. doi:10.1021/ja01232a022. ISSN 0002-7863.

- Birks, J B (1975-08-01). "Excimers". Reports on Progress in Physics. 38 (8): 903–974. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/38/8/001. ISSN 0034-4885. S2CID 240065177.

- Shriver, Duward (2014). Inorganic Chemistry (6th ed.). W.H. Freeman and Company. pp. 306–307. ISBN 9781429299060.

- ^ Shriver, Duward (2014). Inorganic Chemistry (6th ed.). W.H. Freeman and Company. pp. 377–378. ISBN 9781429299060.

- Adams, Richard D.; Collins, Douglas E.; Cotton, F. Albert (1974). "Unusual structural and magnetic resonance properties of dicyclopentadienylhexacarbonyldichromium". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 96 (5): 749–754. doi:10.1021/ja00810a019.

- ^ Marianayagam, Neelan J.; Sunde, Margaret; Matthews, Jacqueline M. (2004). "The power of two: protein dimerization in biology". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 29 (11): 618–625. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2004.09.006. ISSN 0968-0004. PMID 15501681.

- Cooper, Geoffrey M. (2000). "Microtubules". The Cell: A Molecular Approach. 2nd Edition.

- Faron-Górecka, Agata; Szlachta, Marta; Kolasa, Magdalena; Solich, Joanna; Górecki, Andrzej; Kuśmider, Maciej; Żurawek, Dariusz; Dziedzicka-Wasylewska, Marta (2019-01-01), Shukla, Arun K. (ed.), "Chapter 10 - Understanding GPCR dimerization", Methods in Cell Biology, G Protein-Coupled Receptors, Part B, 149, Academic Press: 155–178, doi:10.1016/bs.mcb.2018.08.005, ISBN 9780128151075, PMID 30616817, S2CID 58577416, retrieved 2022-10-27

- Rios, C. D.; Jordan, B. A.; Gomes, I.; Devi, L. A. (2001-11-01). "G-protein-coupled receptor dimerization: modulation of receptor function". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 92 (2): 71–87. doi:10.1016/S0163-7258(01)00160-7. ISSN 0163-7258. PMID 11916530.

- Lohse, Martin J (2010-02-01). "Dimerization in GPCR mobility and signaling". Current Opinion in Pharmacology. GPCR. 10 (1): 53–58. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2009.10.007. ISSN 1471-4892. PMID 19910252.

- ^ Hubbard, Stevan R (1999-04-01). "Structural analysis of receptor tyrosine kinases". Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 71 (3): 343–358. doi:10.1016/S0079-6107(98)00047-9. ISSN 0079-6107. PMID 10354703.

- Lemmon, Mark A.; Schlessinger, Joseph (2010-06-25). "Cell Signaling by Receptor Tyrosine Kinases". Cell. 141 (7): 1117–1134. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.011. ISSN 0092-8674. PMC 2914105. PMID 20602996.

- Lemmon, Mark A.; Schlessinger, Joseph; Ferguson, Kathryn M. (2014-04-01). "The EGFR Family: Not So Prototypical Receptor Tyrosine Kinases". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 6 (4): a020768. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a020768. ISSN 1943-0264. PMC 3970421. PMID 24691965.