| Revision as of 19:26, 18 November 2013 view sourcePsychic warrior x (talk | contribs)3 editsmNo edit summaryTag: section blanking← Previous edit | Revision as of 14:29, 7 November 2024 view source Monkbot (talk | contribs)Bots3,695,952 editsm Task 20: replace {lang-??} templates with {langx|??} ‹See Tfd› (Replaced 1);Tag: AWBNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Varna in Hinduism, one of four castes}} | |||

| {{About|the social caste|the moth family|Brahmaeidae|similarly spelled words|Brahman (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{distinguish|text=] (a metaphysical concept in Hinduism), ] (a Hindu god), ] (a layer of text in the Vedas), or ]}} | |||

| {{Infobox caste | |||

| {{Other uses}} | |||

| | caste_name = Brahmin (Brahmana) | |||

| {{pp|small=yes}} | |||

| | list_style = text-align:left; | |||

| {{EngvarB|date=April 2024}} | |||

| |{{flagicon|India}} ] | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=April 2024}} | |||

| | {{flagicon|Nepal}} ] | |||

| ], ''The Land of Temples (India)'', 1882]]{{Hinduism}} | |||

| | {{flagicon|Arab League}} ] | |||

| '''Brahmin''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|b|r|ɑː|m|ɪ|n}}; {{langx|sa|ब्राह्मण|brāhmaṇa}}) is a ] (]) within ] society. The other three varnas are the ], ], and ].<ref name="Wren2004">{{cite book | author = Benjamin Lee Wren | date = 2004 | title = Teaching World Civilization with Joy and Enthusiasm | publisher = University Press of America | pages = 77– | isbn = 978-0-7618-2747-4 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=XdvfevJAsgMC&pg=PA77|quote=At the top were the Brahmins(priests), then the Kshatriyas(warriors), then the vaishya(the merchant class which only in India had a place of honor in Asia), next were the sudras(farmers), and finally the pariah(untouchables), or those who did the dirty defiling work}}</ref><ref name="Valpey2019">{{cite book | author = Kenneth R. Valpey | date = 2 November 2019 | title = Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics | publisher = Springer Nature | pages = 169– | isbn = 978-3-03-028408-4 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=EJO7DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA169|quote=The four varnas are the brahmins (brahmanas—priests, teachers); kshatriyas (ksatriyas—administrators, rulers); vaishyas (vaisyas—farmers, bankers, business people); and shudras(laborers, artisans)}}</ref><ref name="BullietCrossleyHeadrick2018">{{cite book | author1 = Richard Bulliet | author2 = Pamela Crossley | author3 = Daniel Headrick | author4 = Steven Hirsch | author5 = Lyman Johnson | date = 11 October 2018 | title = The Earth and Its Peoples: A Global History, Volume I | publisher = Cengage Learning | pages = 172– | isbn = 978-0-357-15937-8 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=lJRUEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA172|quote=Varna are the four major social divisions: the Brahmin priest class, the Kshatriya warrior/ administrator class, the Vaishya merchant/farmer class, and the Shudra laborer class.}}</ref><ref name="Iriye1979">{{cite book | author = Akira Iriye | date = 1979 | title = The World of Asia | publisher = Forum Press | isbn = 978-0-88273-500-9 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=tM-CAAAAIAAJ|quote=The four varna groupings in descending order of their importance came to be Brahmin (priests), Kshatriya (warriors and administrators), Vaishya (cultivators and merchants), and Sudra (peasants and menial laborers)|page=106}}</ref><ref name="ludo14"/> The traditional occupation of Brahmins is that of priesthood (], ], or ]) at Hindu temples or at socio-religious ceremonies, and the performing of ] rituals, such as solemnising a wedding with hymns and prayers.<ref name=lochtefeld125>James Lochtefeld (2002), Brahmin, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A–M, Rosen Publishing, {{ISBN|978-0-8239-3179-8}}, page 125</ref><ref name=ghurye15/> | |||

| | {{flagicon|Australia}} ] | |||

| | {{flagicon|Bangladesh}} ] | |||

| Traditionally, Brahmins are accorded the highest ritual status of the four social classes,<ref name=doniger141/> and they also served as spiritual teachers (] or ]). In practice, Indian texts suggest that some Brahmins historically also became ]s, ]s, ]s, and had also held other occupations in the Indian subcontinent.<ref name=ghurye15>GS Ghurye (1969), Caste and Race in India, Popular Prakashan, {{ISBN|978-81-7154-205-5}}, pages 15–18</ref><ref name=doniger141>{{cite book | last=Doniger | first=Wendy | title=Merriam-Webster's encyclopedia of world religions | publisher=Merriam-Webster | location=Springfield, MA, US | year=1999 | isbn=978-0-87779-044-0 | pages= | url=https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780877790440/page/141 }}</ref><ref name="David Shulman 1989 page 111">David Shulman (1989), The King and the Clown, Princeton University Press, {{ISBN|978-0-691-00834-9}}, page 111</ref> | |||

| | {{flagicon|Bhutan}} ] | |||

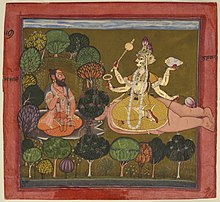

| ] worshipping Shakti]] | |||

| | {{flagicon|Burma}} ] | |||

| | {{flagicon|Canada}} ] | |||

| ==Origin and history == | |||

| | {{flagicon|Fiji}} ] | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | {{flagicon|France}} ] | |||

| | total_width = 300 | |||

| | {{flagicon|Germany}} ] | |||

| | perrow = 2 | |||

| | {{flagicon|Guyana}} ] | |||

| | image1 = Mikhail-Tikhanov-Brahmin-1817.jpg | |||

| | {{flagicon|Indonesia}} ] | |||

| | caption1 = A Brahmin soldier | |||

| | {{flagicon|Kenya}} ] | |||

| | image2 = Four Ascetic Brahmans MET 16459.jpg | |||

| | {{flagicon|Malaysia}} ] | |||

| | caption2 = Four ascetic Brahmins from Gandhara, 2nd century | |||

| | {{flagicon|Mauritius}} ] | |||

| | image3 = Candi Prambanan - 102 Brahmins, Visnu Temple (12042036684).jpg | |||

| | {{flagicon|New Zealand}} ] | |||

| | caption3 = A Brahmin family, 9th century. ], Indonesia. | |||

| | {{flagicon|Pakistan}} ] | |||

| | image4 = A Brahmin standing praying in the corner of the streets 1863.jpg | |||

| | {{flagicon|Singapore}} ] | |||

| | caption4 = A Brahmin standing praying in the corner of the streets. India, 1863. | |||

| | {{flagicon|South Africa}} ] | |||

| | image5 = Officers 1st Brahmins, 1922.jpg | |||

| | {{flagicon|Sri Lanka}} ] | |||

| | caption5 = Brahmin Officers from ] Infantry Regiment | |||

| | {{flagicon|Suriname}} ] | |||

| | image6 = Maharaja Lakshmeshwar Singh statue - Kolkata.JPG | |||

| | {{flagicon|Thailand}} ] | |||

| | caption6 = Maharaja Lakhmeshwar Singh statue | |||

| | {{flagicon|Trinidad and Tobago}} ] | |||

| | image7 = Chanakya artistic depiction.jpg | |||

| | {{flagicon|United Kingdom}} ] | |||

| | caption7 = Ancient Indian economist and military strategist ] | |||

| | {{Flagicon|United States}} ] | |||

| | image8 = Aryabhata-5 (1).jpg | |||

| | religions = ] ] | |||

| | caption8 = Ancient Indian mathematician and astronomer ] | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Hinduism}} | |||

| {{Buddhism}} | |||

| {{Jainism}} | |||

| '''Brahmin''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|b|r|ɑː|m|ɪ|n}}; also called '''Brahmana'''; from the ] ''{{IAST|brāhmaṇa}}'' {{lang|sa|ब्राह्मण}}) are traditional ] of ], ] and ]. | |||

| It seems likely that ] and Middle country was the place of origin of majority of migrating Brahmins throughout the medieval centuries.<ref>{{Cite book |first=André|last=Wink|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uPXvDwAAQBAJ |title=The Making of the Indo-Islamic World C.700–1800 CE|page=42|date=2020|publisher=E.J. Brill |isbn=978-1-108-41774-7 }}</ref> Coming from ] is a frequent claim among Brahmins in areas distant from Madhyadesha or Ganges heartland.<ref>{{Cite book |first=Romila|last=Thapar|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jFY8wFz-Pj8C |title=Somanatha|date=2008|publisher=Penguin Books|isbn=978-93-5118-021-0 }}</ref> | |||

| ], Brahmin, and Brahma have different meanings. Brahman refers to the Supreme Self. Brahmin (or Brahmana) refers to an individual belonging to the Hindu priest, artists, teachers, technicians class (] or pillar of the society) and also to an individual belonging to the Brahmin ]/] into which an individual is born; while the word ] refers to the creative aspect of the universal consciousness or ]. Because the ] / ] is knowledgeable about ] (the ]), and is responsible for religious ]s in ]s and homes and is a person authorized after rigorous training in ]s (sacred texts of knowledge) and ] ]s to provide advice and impart knowledge of ] to members of the society and assist in attainment of ], the liberation from life cycle; the priest / Acharya class is called "Brahmin ]." The English word ''brahmin'' is an anglicized form of the Sanskrit word ''{{IAST|Brāhman}}a''. | |||

| ===Generic meaning of the term "Brahmin"=== | |||

| According to ancient ]n ]s and ]s, the ] ] comprises four pillars or classes called ] or ]s. In the ancient Indian texts such as '']s, ]s, ]s, ]s'', etc., these four "]" or classes or pillars of the society are: the ]s / ] (Brahmins), the rulers and military (]s), the ]s and ]s(]s), and the Assistants (]s). | |||

| ] | |||

| The term Brahmin appears extensively in ancient and medieval ]s and commentary texts of ] and ].<ref name="lopez2004busc1">{{cite book|author=Donald Lopez |title=Buddhist Scriptures |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6Pd-2IIzip4C |year=2004|publisher=Penguin Books |isbn=978-0-14-190937-0 |pages=xi–xv}}</ref> Modern scholars state that such usage of the term Brahmin in ancient texts does not imply a caste, but simply "masters" (experts), guardian, recluse, preacher or guide of any tradition.<ref name="Jaini2001p123"/><ref name="Jayatilleke2013">{{cite book|author=K N Jayatilleke|title=Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6pBTAQAAQBAJ |year=2013|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-134-54287-1|pages=141–154, 219, 241 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author=Kailash Chand Jain |title=Lord Mahāvīra and His Times |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8-TxcO9dfrcC |year=1991 |publisher=Motilal Banarsidass |isbn=978-81-208-0805-8 |page=31 |access-date=10 October 2016 |archive-date=11 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230111053959/https://books.google.com/books?id=8-TxcO9dfrcC |url-status=live }}</ref> An alternate synonym for Brahmin in the Buddhist and other non-Hindu tradition is ''Mahano''.<ref name="Jaini2001p123">{{cite book|author=Padmanabh S. Jaini |title=Collected Papers on Buddhist Studies |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZlyDot9RyGcC&pg=PA123 |year=2001|publisher=Motilal Banarsidass |isbn=978-81-208-1776-0 |page=123 }}</ref> | |||

| Brahmin ]s / ] were engaged in attaining the highest spiritual ] (]) of ] (]) and adhered to different branches (]s) of ]s. Brahmin ] is responsible for ] ]s in ]s and ]s of ]s and is a person authorized after rigorous training in ]s and ] ]s, and as a liaison between ]s and the ]. In general, as family ]s and businesses are ], ] used to be inherited among Brahmin ] families, as it requires years of practice of ]s from childhood after proper introduction to student life through a ] ] called ] at the age of about five. | |||

| Strabo cites Megasthenes, highlighting two Indian philosophical schools ] and ]: | |||

| Individuals from the Brahmin ]s/]s have taken on many professions such as ]s, ]s and ]s to ]s and business people, according to 12th century poet ], in ].<ref>http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/490128/Rajatarangini</ref> According to ], a ] and ] poet, in ] history, Brahmin ] ] is an ] (] ] representation) of Lord ], who takes up arms against kings to deliver ]. Sage ] is portrayed as a powerful ] who defeated the ] ]s twenty one times, was an expert in ] arts and the use of weapons, and trained others to fight without weapons.<ref name="Saraswati 2003 519 Volume 1">{{cite book | |||

| {{blockquote|Megasthenes makes a different division of the philosophers, saying that they are of two kinds, one of which he calls the ], and the other the ]...|source=] XV. 1. 58-60<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0239&query=head%3D%23119 |title=Strabo XV.1 |publisher=Perseus.tufts.edu |access-date=2010-09-01 |archive-date=2007-12-27 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071227232800/http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0239&query=head%3D%23119 |url-status=live }}</ref>}} | |||

| | first = Swami Sahajanand | |||

| | last = Saraswati | |||

| | authorlink = Swami Sahajanand Saraswati | |||

| | title = Swami Sahajanand Saraswati Rachnawali in Six volumes (in Volume 1) | |||

| | publisher = Prakashan Sansthan | |||

| | location = Delhi | |||

| | year = 2003 | |||

| | isbn = 81-7714-097-3 | |||

| | pages = 519 (Volume 1) | |||

| }}</ref><ref name="Crooke 1999 1809 at page 64">{{Cite book | |||

| | first = William | |||

| | last = Crooke | |||

| | authorlink = William Crooke | |||

| | title = The Tribes and Castes of the North-Western Provinces and Oudh | |||

| | publisher=] | |||

| | location = 6A, Shahpur Jat, New Delhi-110049, India | |||

| | year =1999 | |||

| | pages =1809 (at page 64) | |||

| | isbn = 81-206-1210-8 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| Patrick Olivelle states that both Buddhist and Brahmanical literature repeatedly define "Brahmin" not in terms of family of birth, but in terms of personal qualities.<ref name=olivelleaab60/> These virtues and characteristics mirror the values cherished in Hinduism during the ] stage of life, or the life of renunciation for spiritual pursuits. Brahmins, states Olivelle, were the social class from which most ascetics came.<ref name=olivelleaab60>Patrick Olivelle (2011), Ascetics and Brahmins: Studies in Ideologies and Institutions, Anthem, {{ISBN|978-0-85728-432-7}}, page 60</ref> The term Brahmin in Indian texts has also signified someone who is good and virtuous, not just someone of priestly class.<ref name=olivelleaab60/> | |||

| ], son of a Brahmin sage ] and a fisher woman ], in his ], describes several warriors belonging to Brahmin ]/], such as ], ], ] etc., who were professors in the schools of martial arts and the art of war. | |||

| === Purusha sukta === | |||

| ==History== | |||

| The earliest inferred reference to "Brahmin" as a possible social class is in the ], occurs once, and the hymn is called ].<ref>], , ], pages 570–571</ref> According to a hymn in ], Rigveda 10.90.11-2, Brahmins are described as having emerged from the mouth of ], being that part of the body from which words emerge.<ref>{{cite book |title=Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300 |first=Romila |last=Thapar |author-link=Romila Thapar |publisher=University of California Press |year=2004 |isbn=9780520242258 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-5irrXX0apQC&pg=PA125 |page=125}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|History of Hinduism}} | |||

| The Purusha Sukta varna verse is now generally considered to have been inserted at a later date into the Vedic text, possibly as a ].<ref name="Jamison 2014 57–58"/> Stephanie Jamison and Joel Brereton, a professor of Sanskrit and Religious studies, state, "there is no evidence in the Rigveda for an elaborate, much-subdivided and overarching caste system", and "the varna system seems to be embryonic in the Rigveda and, both then and later, a social ideal rather than a social reality".<ref name="Jamison 2014 57–58">{{cite book | last=Jamison| first=Stephanie | title=The Rigveda: the earliest religious poetry of India | publisher=Oxford University Press | year=2014 | isbn=978-0-19-937018-4 |pages=57–58|display-authors=etal}}</ref> | |||

| Tatrapi janma shata kotishu manavatvam : After attaining shata koti janma one comes to manava janma. | |||

| According to Vijay Nath, in the ] (250 CE), there are references to Brahmins who were born into the families of ]. He posits that this is an indication that some Brahmins are immigrants and some are also mixed.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Nath |first=Vijay |date=2001 |title=From 'Brahmanism' to 'Hinduism': Negotiating the Myth of the Great Tradition |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/3518337 |journal=Social Scientist |volume=29 |issue=3/4 |pages=25 |doi=10.2307/3518337 |jstor=3518337 |issn=0970-0293}}</ref> | |||

| Tatrapi janma shata kotishu brahmanatvam : After attaining shata koti manava janma one comes to Brahmana janma. | |||

| === Gupta era === | |||

| Tatrapi janma shata kotishu vaishnavatvam : After attaining shata koti Brahmana janma ones comes to vaishnava janma | |||

| ] around fire]] | |||

| ] | |||

| According to ], "Brahmin as a varna hardly had any presence in historical records before the ] era" (3rd century to 6th century CE), when Buddhism dominated the land. "No Brahmin, no sacrifice, no ritualistic act of any kind ever, even once, is referred to" in any Indian texts between third century BCE and the late first century CE. He also states that "The absence of literary and material evidence, however, does not mean that Brahmanical culture did not exist at that time, but only that it had no elite patronage and was largely confined to rural folk, and therefore went unrecorded in history".<ref name=eraly283>Abraham Eraly (2011), ''The First Spring: The Golden Age of India,'' Penguin, {{ISBN|978-0-670-08478-4}}, page 283</ref> Their role as priests and repository of sacred knowledge, as well as their importance in the practice of Vedic Shrauta rituals, grew during the Gupta Empire era and thereafter.<ref name=eraly283/> | |||

| According to ], a ] hymn, Brahmins were born from ]'s (]'s) face. | |||

| However, the knowledge about actual history of Brahmins or other varnas of Hinduism in and after the first millennium is fragmentary and preliminary, with little that is from verifiable records or archaeological evidence, and much that is constructed from ahistorical Sanskrit works and fiction. ] writes: | |||

| Most ]s (sects) of modern Brahmins claim to take inspiration from the Vedas. According to orthodox Hindu tradition, the Vedas are ''{{IAST|apauruṣeya}}'' and ''anādi'' (beginning-less), and are revealed truths of eternal validity. The Vedas are considered '']'' ("that which is heard") and are the paramount source on which Brahmin tradition claims to be based. Śruti texts include the four Vedas (the ], the ], the ] and the ]), and their respective ], ] and ]. | |||

| {{blockquote|Current research in the area is fragmentary. The state of our knowledge of this fundamental subject is preliminary, at best. Most Sanskrit works are a-historic or, at least, not especially interested in presenting a chronological account of India's history. When we actually encounter history, such as in ''Rajatarangini'' or in the ''Gopalavamsavali'' of Nepal, the texts do not deal with brahmins in great detail.<ref>Michael Witzel (1993) {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181001041949/https://www.jstor.org/stable/603031 |date=1 October 2018 }}, ''Journal of the American Oriental Society,'' Vol. 113, No. 2, pages 264–268</ref>}} | |||

| ==Gauda and Dravida Brahmins== | |||

| Apart from clerical positions, Brahmins have also historically been ministers (known as ''Sachivas'' or ''Amatyas'') in dynasties. | |||

| According to ]'s '']'' (12th cent. CE) and ] (5th–13th cent. CE) of Skandapurana, Brahmins are broadly classified into two groups based on geography.<ref name="JGL_2002">{{cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/illustratedencyc0000loch |url-access=registration |title=The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: N-Z |author=James G. Lochtefeld |publisher=Rosen |year=2002 |isbn=9780823931804 |page= }}</ref> The northern ] group comprises five Brahmin communities, as mentioned in the text, residing north of the ].<ref name="JGL_2002"/><ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lXyWE6KbG8oC&pg=PA168 |title=Caste in Life: Experiencing Inequalities |editor=D. Shyam Babu and ] |publisher=Pearson Education India |year=2011 |isbn=9788131754399 |page=168}}</ref> Historically, the Vindhya mountain range formed the southern boundary of the '']'', the territory of the ancient ], and Gauda has territorial, ethnographic and linguistic connotations.{{sfnp|Narasimhacharya|1999|p=8}} Linguistically, the term "Gauda" refers to the Sanskrit-derived languages of northern India.{{sfnp|Narasimhacharya|1999|p=8}} The Pancha Gauda Brahmins are:<ref name="JGL_2002"/> | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| Subcastes of ] are: | |||

| * Sanadhya<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bahadur |first=K. P. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yQHpEQ8HkRMC&dq=titles+of+sanadhya+brahmins&pg=PA28 |title=Selection From Ramachndrika Of Keshv |date=1976 |publisher=Motilal Banarsidass Publ. |isbn=978-81-208-2789-9 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ===Clerical positions=== | |||

| * Paliwal<ref>{{Cite news |date=26 August 2018 |title=This community does not believe in the tradition |url=https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/jaipur/this-community-does-not-believe-in-the-tradition/articleshow/65546929.cms |access-date=26 March 2024 |work=The Times of India |issn=0971-8257}}</ref> | |||

| #] (''Priest'') - Purohita (performer for domestic ceremonies) and Rtvij (performer of seasonal ceremonies) | |||

| #] or ] (''Spiritual teacher'') | |||

| #] | |||

| #Tapasvin - Mendicant | |||

| Subcastes of Kanyakubja Brahmins are: | |||

| ===Requirements for being Brahmin=== | |||

| *Jujhatiya Brahmin<ref name="Sherring 1977">{{Cite book |last=Sherring|first=Matthew Atmore |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iTXXAAAAMAAJ |title=Hindu Tribes and Castes Volume 1 | |||

| According to a Buddhist scripture, at the time of the Buddha in eastern India there were five requirements for being Brahmin:<ref>{{cite book|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=VMf-isGALqQC&pg=PA163&lpg=PA163&dq=varna+jati+mantra+sila+panditya&source=bl&ots=knkIlYXXv8&sig=u6PBh2zAShwNwBrSnsdZFfA8ciA&hl=en&sa=X&ei=4eoMUrf-DIyMigKR3IC4Aw&ved=0CDcQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=varna%20jati%20mantra%20sila%20panditya&f=false|title=Foundations of Indian Culture|author=Govind Chandra Pande|accessdate=2013-08-15}}</ref> | |||

| |date=1977 |publisher=Thacker, spink and company|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| *]<ref name="Sherring 1977"/> | |||

| *Bengali ]<ref name="Sherring 1977"/> | |||

| *]<ref>{{Cite book |first=André |last=Wink|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bCVyhH5VDjAC |title=Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: The slave kings and the Islamic conquest, 11th–13th centuries|date=1990 |publisher=E.J. Brill|isbn=978-90-04-09249-5 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WFfVAAAAMAAJ |title=Bhāratīya sāhitya, Volume 19|date=1974 |publisher=Agra University. K.M. Institute of Hindi Studies and Linguistics.}}</ref> ( Though they are generally not accepted as Brahmins) | |||

| *] – Nepali Bahuns<ref name="Sherring 1977"/><ref>{{Cite book |last=Chaturvedi |first=Shyam lal (Rai bahadur) |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=91ACAAAAMAAJ |title=In Fraternity with Nepal, An Account of the Activities Under the Auspices of the Wider Life Movement for the Furtherance and Consolidation of the Indo-Nepalese Cultural Fellowship |page=65|date=1945|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| The Pancha ] Brahmins reside to the south of the Vindhya mountain range.<ref name="JGL_2002"/> The term "Dravida" too has territorial, linguistic and ethnological connotations, referring to southern India, the Dravidian people, and to the Dravidian languages of southern India.{{sfnp|Narasimhacharya|1999|p=8}} The Pancha Dravida Brahmins are: | |||

| #Varna (ubhato sujato hoti) or Brahmin status on both sides of the family | |||

| * Karnataka (]) | |||

| #Jati (avikkitto anupakutto jativadena) | |||

| * Tailanga (]) | |||

| #Mantra (ajjhayako hoti mantradharo) | |||

| * Dravida (Brahmins of ] and ]) | |||

| #Sila or virtue | |||

| * Maharashtraka (]s) | |||

| #Panditya or learned | |||

| * Gurjara (])<ref>{{cite book|title=Abu in Bombay State: A Scientific Study of the Problem|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BM8BAAAAMAAJ&q=pancha+dravida+gurjara+rajasthan|quote=It is interesting to note here that the Brahmin groups of Marwar and Mewar belong to the Gurjara group of the Pancha Dravida division|first=A V|last=Pandya|publisher=Charutar Vidya Mandal|year=1952|page=29}}</ref> | |||

| ==Role in the society == | |||

| ==Practices== | |||

| ===Vedic duties=== | |||

| Brahmins, basically adhere to the principles of the ], related to the texts of the ] and ] which are some the foundations of ], and practice ]. Vedic ''{{IAST|Brāhmaṇas}}'' have six occupational duties, of which three are compulsory — studying the Vedas, performing Vedic rituals and practicing dharma. By teaching the insights of the Vedic literature which deals with all aspects of life including spirituality, philosophy, yoga, religion, rituals, temples, arts and culture, music, dance, grammar, pronunciation, metre, astrology, astronomy, logic, law, medicine, surgery, technology, martial arts, military strategy, etc. By spreading its philosophy, and by accepting back from the community, the Brahmins receive the necessities of life.{{citation needed|date=August 2013}} | |||

| The ] and ] texts of Hinduism describe the expectations, duties and role of Brahmins. | |||

| According to Kulkarni, the Grhya-sutras state that ], Adhyayana (studying the vedas and teaching), dana pratigraha (accepting and giving gifts) are the "peculiar duties and privileges of brahmins".<ref>{{cite journal |author=Kulkarni, A.R. |year=1964 |title=Social and Economic Position of Brahmins in Maharashtra in the Age of Shivaji |journal=Proceedings of the Indian History Congress |volume=26 |pages=66–67 |jstor=44140322}}</ref> John Bussanich states that the ethical precepts set for Brahmins, in ancient Indian texts, are similar to Greek virtue-ethics, that "Manu's dharmic Brahmin can be compared to Aristotle's man of practical wisdom",<ref>John Bussanich (2014), Ancient Ethics (Editors: Jörg Hardy and George Rudebusch), Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, {{ISBN|978-3-89971-629-0}}, pages 38, 33–52, Quote: "Affinities with Greek virtue ethics are also noteworthy. Manu's dharmic Brahmin can be compared to Aristotle's man of practical wisdom, who exercises moral authority because he feels the proper emotions and judges difficult situations correctly, when moral rules and maxims are unavailable".</ref> and that "the virtuous Brahmin is not unlike the Platonic-Aristotelian philosopher" with the difference that the latter was not sacerdotal.<ref>John Bussanich (2014), Ancient Ethics (Editors: Jörg Hardy and George Rudebusch), Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, {{ISBN|978-3-89971-629-0}}, pages 44–45</ref> | |||

| Male members of ''all'' Brahmin sects wear the ] (]:जनेऊ or sacred thread) that is a symbol of initiation to the Gayatri recital. This ritual is often referred to as ]. This marks the learning of the Gayatri hymn. Brahmin sects also generally identify themselves as belonging to a particular ], a classification based on patrilineal descent, which is specific for each family and indicates their origin.{{citation needed|date=August 2013}} | |||

| The Brahmins were expected to perform all six Vedic duties as opposed to other ] who performed three. | |||

| ==Brahmin communities== | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| {{unreferenced section|date=August 2013}} | |||

| |+ Vedic duties of twice-born Varnas<ref name="ludo14">{{cite book|author=Ludo Rocher|editor=Donald R. Davis Jr.|title=Studies in Hindu Law and Dharmaśāstra|chapter=9.Caste and occupation in classical India: The normative texts|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dziNBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA205|year=2014|publisher=Anthem Press|pages=205–206|isbn=9781783083152}}</ref> | |||

| The Brahmin ] may be broadly divided into two regional groups: ] Brahmins from the Northern part of India (considered to be the region north of the ] mountains) and Pancha-Dravida Brahmins from the region south of the Vindhya mountains as per the ] of Kalhana. | |||

| |- | |||

| ! !!''Adhyayan''<br />(Study Vedas)!!''Yajana''<br />(performing sacrifice for<br /> one's own benefit)!!Dana<br />(Giving Gifts)!!Adhyapana<br />(Teaching Vedas)!!Yaajana<br />(Acting as Priest<br />for sacrifice)!!''Pratigraha'' (accepting gifts) | |||

| |- | |||

| | Brahmin|| ✓ || ✓ || ✓ || ✓ ||✓ ||✓ | |||

| |- | |||

| | Kshatriya|| ✓ || ✓ || ✓ || No||No||No | |||

| |- | |||

| | Vaishya|| ✓ || ✓ || ✓ || No||No||No | |||

| |- | |||

| |- | |||

| |} | |||

| ===Actual occupations=== | |||

| *Saraswat, Kanyakubja, Gaud, Utkala and Mithila form the Pancha Guada | |||

| ], a proponent of Advaita Vedanta, was born into a Brahmin family. His disciple, Adi Shankara, is credited with unifying and establishing the main currents of thought in Hinduism.<ref>Johannes de Kruijf and Ajaya Sahoo (2014), Indian Transnationalism Online: New Perspectives on Diaspora, {{ISBN|978-1-4724-1913-2}}, page 105, Quote: "In other words, according to Adi Shankara's argument, the philosophy of Advaita Vedanta stood over and above all other forms of Hinduism and encapsulated them. This then united Hinduism; (...) Another of Adi Shankara's important undertakings which contributed to the unification of Hinduism was his founding of a number of monastic centers."</ref><ref>''Shankara'', Student's Encyclopædia Britannica – India (2000), Volume 4, Encyclopædia Britannica (UK) Publishing, {{ISBN|978-0-85229-760-5}}, page 379, Quote: "Shankaracharya, philosopher and theologian, most renowned exponent of the Advaita Vedanta school of philosophy, from whose doctrines the main currents of modern Indian thought are derived."<br />David Crystal (2004), The Penguin Encyclopedia, Penguin Books, page 1353, Quote: " is the most famous exponent of Advaita Vedanta school of Hindu philosophy and the source of the main currents of modern Hindu thought."</ref><ref>Christophe Jaffrelot (1998), The Hindu Nationalist Movement in India, Columbia University Press, {{ISBN|978-0-231-10335-0}}, page 2, Quote: "The main current of Hinduism – if not the only one – which became formalized in a way that approximates to an ecclesiastical structure was that of Shankara".</ref>]] | |||

| *Karnataka, Telangaa, Dravida, Maharashtra and Gurjarat form the Pancha Dravida | |||

| Historical records, state scholars, suggest that Brahmin varna was not limited to a particular status or priest and the teaching profession.<ref name="ghurye15"/><ref name="David Shulman 1989 page 111"/><ref name=baileymabbett114/> ], a Brahmin born in 375 BCE, was an ancient Indian polymath who was active as a teacher, author, strategist, philosopher, economist, jurist, and royal advisor, who assisted the first Mauryan emperor ] in his rise to power and is widely credited for having played an important role in the establishment of the ].<ref>{{cite book |first=Thomas R. |last=Trautmann |author-link=Thomas Trautmann |title=Kauṭilya and the Arthaśāstra: a statistical investigation of the authorship and evolution of the text |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=v3iDAAAAMAAJ |year=1971 |publisher=Brill |pages=11–13}}</ref> Historical records from mid 1st millennium CE and later, suggest Brahmins were agriculturalists and warriors in medieval India, quite often instead of as exception.<ref name="ghurye15"/><ref name="David Shulman 1989 page 111"/> Donkin and other scholars state that ] records frequently mention Brahmin merchants who "carried on trade in horses, elephants and pearls" and transported goods throughout medieval India before the 14th-century.<ref>RA Donkin (1998), Beyond Price: Pearls and Pearl-fishing, American Philosophical Society, {{ISBN|978-0-87169-224-5}}, page 166</ref><ref>SC Malik (1986), Determinants of Social Status in India, Indian Institute of Advanced Study, {{ISBN|978-81-208-0073-1}}, page 121</ref> | |||

| ==Pancha-Gauda== | |||

| ], a ], in ], ]]] | |||

| ] and the first historical proponent of ], also believed to be the founder of ].]] | |||

| {{main|Pancha-Gauda}} | |||

| The ] depicts Brahmins as the most prestigious and elite non-Buddhist figures.<ref name="baileymabbett114"/> They mention them parading their learning. The Pali Canon and other ] such as the ''Jataka Tales'' also record the livelihood of Brahmins to have included being farmers, handicraft workers and artisans such as carpentry and architecture.<ref name=baileymabbett114/><ref>Stella Kramrisch (1994), Exploring India's Sacred Art, Editor: Stella Miller, Motilal Banarsidass, {{ISBN|978-81-208-1208-6}}, pages 60–64</ref> Buddhist sources extensively attest, state Greg Bailey and Ian Mabbett, that Brahmins were "supporting themselves not by religious practice, but employment in all manner of secular occupations", in the classical period of India.<ref name=baileymabbett114>Greg Bailey and Ian Mabbett (2006), The Sociology of Early Buddhism, Cambridge University Press, {{ISBN|978-0-521-02521-8}}, pages 113–115 with footnotes</ref> Some of the Brahmin occupations mentioned in the Buddhist texts such as '']'' and '']'' are very lowly.<ref name=baileymabbett114/> The '']'' too mention Brahmin farmers.<ref name="baileymabbett114"/><ref>{{cite journal | last=RITSCHL | first=Eva | title=Brahmanische Bauern. Zur Theorie und Praxis der brahmanischen Ständeordnung im alten Indien | journal=Altorientalische Forschungen | publisher=Walter de Gruyter GmbH | volume=7 | issue=JG | year=1980 | doi=10.1524/aofo.1980.7.jg.177 | pages=177–187 | s2cid=201725661 |language=de|issn=0232-8461 }}</ref> | |||

| The Brahmins from ], ], ], ] and ], who with passage of time spread to North East, East and West, were called Pancha Gauda. | |||

| This group is originally from ] (]). | |||

| Pancha Gauda Brahmins are divided into five main categories: | |||

| According to Haidar and Sardar, unlike the Mughal Empire in Northern India, Brahmins figured prominently in the administration of ]. Under ] Telugu ] Brahmins served in many different roles such as accountants, ministers, in the revenue administration, and in the judicial service.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Haidar|first1=Navina Najat|last2=Sardar|first2=Marika|title=Sultans of Deccan Indian 1500–1700|date=2015|publisher=Museum Of Metropolitan Art |location=New Haven, CT, US|isbn=978-0-300-21110-8|pages=11–12|edition=1|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oi4nBwAAQBAJ |access-date=20 April 2016}}</ref> The Deccan sultanates also heavily recruited ] at different levels of their administration.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Gordon|first1=Stewart|title=Cambridge History of India: The Marathas 1600–1818|date=1993|publisher=Cambridge University press|location=Cambridge, UK|isbn=978-0-521-26883-7|page=16|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iHK-BhVXOU4C&q=deshastha&pg=PR9}}</ref> During the days of ] in the 17th and 18th century, the occupation of ] ranged from being state administrators, being warriors to being de facto rulers as ].<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SYOSHaZnBy8C&pg=PA129 |title=The Satara Raj, 1818–1848: A Study in History, Administration, and Culture – Sumitra Kulkarni |access-date=23 March 2013|isbn=978-81-7099-581-4 |year=1995 |last1=Kulkarni |first1=Sumitra |publisher=Mittal Publications }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/285248/India/46988/Rise-of-the-peshwas |title=India : Rise of the peshwas - Britannica Online Encyclopedia |publisher=Britannica.com |date=8 November 2011 |access-date=23 March 2013 |archive-date=26 April 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130426031917/http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/285248/India/46988/Rise-of-the-peshwas |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ===Sarasvat Brahmins=== | |||

| After the collapse of Maratha empire, Brahmins in Maharashtra region were quick to take advantage of opportunities opened up by the new British rulers. They were the first community to take up Western education and therefore dominated lower level of British administration in the 19th century.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Hanlon|first1=Rosilind|title=Caste, Conflict and Ideology: Mahatma Jotirao Phule and low caste protest in nineteenth-century Western India|date=1985|publisher=Cambridge University Press.|location=Cambridge, UK|isbn=0-521-52308-7|pages=122–123|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5kMrsTj1NeYC&q=phule+vedas&pg=PR9|access-date=11 August 2016}}</ref> Similarly, the Tamil Brahmins were also quick to take up English education during British colonial rule and dominate government service and law.<ref name="Seal1971">{{cite book|author=Anil Seal|title=The Emergence of Indian Nationalism: Competition and Collaboration in the Later Nineteenth Century|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xV84AAAAIAAJ&pg=PR13|date=2 September 1971|publisher=CUP Archive|isbn=978-0-521-09652-2|page=98}}</ref> | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| Eric Bellman states that during the Islamic Mughal Empire era Brahmins served as advisers to the Mughals, later to the British Raj.<ref name=bellmanwsj/> The ] also recruited ]s (soldiers) from the Brahmin communities of ] and ] (in the present day Uttar Pradesh)<ref name="Pandey2002">{{cite book|author=Gyanendra Pandey|title=The Ascendancy of the Congress in Uttar Pradesh: Class, Community and Nation in Northern India, 1920–1940|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Nxmed64K7d8C&pg=PP10|year=2002|publisher=Anthem Press|isbn=978-1-84331-057-0|page=6}}</ref> for the ].<ref name="Omissi2016">{{cite book|author=David Omissi|title=The Sepoy and the Raj: The Indian Army, 1860-1940|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=suG-DAAAQBAJ&pg=PP1|date=27 July 2016|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-1-349-14768-7|page=4}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Groseclose|first1=Barbara|title=British sculpture and the Company Raj : church monuments and public statuary in Madras, Calcutta, and Bombay to 1858|date=1994|publisher=University of Delaware Press|location=Newark, Del.|isbn=0-87413-406-4|page=67|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dR6F_ZdieAUC&pg=PA67 |access-date=20 April 2016}}</ref> Many Brahmins, in other parts of South Asia lived like other varna, engaged in all sorts of professions. Among Nepalese Hindus, for example, Niels Gutschow and Axel Michaels report the actual observed professions of Brahmins from 18th- to early 20th-century included being temple priests, ministers, merchants, farmers, potters, masons, carpenters, coppersmiths, stone workers, barbers, and gardeners, among others.<ref>Niels Gutschow and Axel Michaels (2008), Bel-Frucht und Lendentuch: Mädchen und Jungen in Bhaktapur Nepal, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, pages 23 (table), for context and details see 16–36</ref> | |||

| ===Kanyakubja Brahmins=== | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ]/] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| Other 20th-century surveys, such as in the state of ], recorded that the primary occupation of almost all Brahmin families surveyed was neither priestly nor Vedas-related, but like other varnas, ranged from crop farming (80 per cent of Brahmins), dairy, service, labour such as cooking, and other occupations.<ref name=noormohammad45/><ref>Ramesh Bairy (2010), Being Brahmin, Being Modern, Routledge, {{ISBN|978-0-415-58576-7}}, pages 86–89</ref> The survey reported that the Brahmin families involved in agriculture as their primary occupation in modern times plough the land themselves, many supplementing their income by selling their labour services to other farmers.<ref name=noormohammad45>Noor Mohammad (1992), New Dimensions in Agricultural Geography, Volume 3, Concept Publishers, {{ISBN|81-7022-403-9}}, pages 45, 42–48</ref><ref>G Shah (2004), Caste and Democratic Politics in India, Anthem, {{ISBN|978-1-84331-085-3}}, page 40</ref> | |||

| ===Gauda Brahmins=== | |||

| ==Bhakti movement and Social Reform movements== | |||

| ===Mithila Brahmins=== | |||

| ], a Brahmin, who founded ]]] | |||

| The ] are a group of Brahmins typically originating from and living in and around ], which is part of North Bihar. They are a community of highly cohesive, traditional Brahmins who strive to follow rites and rituals according to ancient Hindu canons.{{Citation needed|date=March 2012}} They have a reputation for orthodoxy and interest in learning.{{Citation needed|date=March 2012}} A large number of Maithil Brahmins migrated a few centuries ago to adjoining areas of South-east Bihar and Jharkhand, as well as to adjoining Terai regions of Nepal. Most of the Maithil Brahmins are Śāktas (worshippers of Śakti) . However, it is also not uncommon to find Vaishnavites among the Maithil Brahmins. Some surnames of Brahmins in Bihar include Shukla, Sharma, Mishra, Kissoon, Bhardwaj, Bhagwan, Choudhary, Jha, Bhatt, Kanojia, Kaileyas, Bhaglani, Pingal, and Lakhlani, amongst others. ] is their mother tongue, though many use ] (a south-eastern dialect of Maithili) as their mother tongue. | |||

| Many of the prominent thinkers and earliest champions of the ] were Brahmins, a movement that encouraged a direct relationship of an individual with a personal god.<ref>Sheldon Pollock (2009), The Language of the Gods in the World of Men, University of California Press, {{ISBN|978-0520260030}}, pages 423–431</ref><ref name=bhakti2/> Among the many Brahmins who nurtured the Bhakti movement were ], ], ] and ] of Vaishnavism,<ref name=bhakti2>{{cite book|author=Oliver Leaman|title=Eastern Philosophy: Key Readings|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vK-GAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA251|year=2002|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-134-68919-4|page=251}};<br />{{cite book|author=S. M. Srinivasa Chari|title=Vaiṣṇavism: Its Philosophy, Theology, and Religious Discipline|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=evmiLInyxBMC |year=1994|publisher=Motilal Banarsidass |isbn=978-81-208-1098-3|pages=32–33}}</ref> ], another devotional poet ].<ref name=ronald>Ronald McGregor (1984), Hindi literature from its beginnings to the nineteenth century, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, {{ISBN|978-3-447-02413-6}}, pages 42–44</ref><ref name=william>William Pinch (1996), '''', University of California Press, {{ISBN|978-0-520-20061-6}}, pages 53–89</ref> Born in a Brahmin family,<ref name=ronald/><ref name=lorenzen>], Who Invented Hinduism: Essays on Religion in History, {{ISBN|978-81-902272-6-1}}, pages 104–106</ref> Ramananda welcomed everyone to spiritual pursuits without discriminating anyone by gender, class, caste or religion (such as Muslims).<ref name=lorenzen/><ref name=larsonvair>Gerald James Larson (1995), India's Agony Over Religion, State University of New York Press, {{ISBN|978-0-7914-2412-4}}, page 116</ref><ref name=julia>Julia Leslie (1996), Myth and Mythmaking: Continuous Evolution in Indian Tradition, Routledge, {{ISBN|978-0-7007-0303-6}}, pages 117–119</ref> He composed his spiritual message in poems, using widely spoken vernacular language rather than Sanskrit, to make it widely accessible. The Hindu tradition recognises him as the founder of the Hindu ],<ref name=schomer>Schomer and McLeod (1987), The Sants: Studies in a Devotional Tradition of India, Motilal Banarsidass, {{ISBN|978-81-208-0277-3}}, pages 4–6</ref> the largest ] renunciant community in Asia in modern times.<ref name=selva>Selva Raj and William Harman (2007), Dealing with Deities: The Ritual Vow in South Asia, State University of New York Press, {{ISBN|978-0-7914-6708-4}}, pages 165–166</ref><ref name=lochtefeld553>James G Lochtefeld (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: N-Z, Rosen Publishing, {{ISBN|978-0-8239-3180-4}}, pages 553–554</ref> | |||

| ===Utkala Brahmins=== | |||

| The Sanskrit text Brāhmaṇotpatti-Mārtaṇḍa by Pt. Harikrishna Śāstri mentions that a king named Utkala invited Brahmins from the Gangetic Valley to perform a ] in Jagannath-Puri in ]. When the yajna ended, these Brahmins laid the foundation of Lord Jagannath there and settled around Odisha, ] and ]. The ]s are of three classes 1) Shrautiya (vaidika), 2) Sevayata and 3) Halua Brahmins. | |||

| Other medieval era Brahmins who led spiritual movements without social or gender discrimination included ] (9th-century female poet), ] (12th-century Lingayatism), ] (13th-century Bhakti poet), ] (16th-century Vaishnava poet), ] (14th-century Vaishnava saint) were among others.<ref>John Stratton Hawley (2015), A Storm of Songs: India and the Idea of the Bhakti Movement, Harvard University Press, {{ISBN|978-0-674-18746-7}}, pages 304–310</ref><ref>Rachel McDermott (2001), Singing to the Goddess: Poems to Kālī and Umā from Bengal, Oxford University Press, {{ISBN|978-0-19-513434-6}}, pages 8–9</ref><ref name="autogenerated2"> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070926224314/http://www.orissa.gov.in/e-magazine/Orissareview/may2005/engpdf/mahima_dharma_bhima_bhoi_biswanathbaba.pdf |date=26 September 2007 }}, An Orissa movement by Brahmin Mukunda Das (2005)</ref> | |||

| ==Pancha-Dravida== | |||

| Brahmins who live in south of Vidhya mountains are called Pancha-Dravida Brahmins and they are divided into following groups. Drava means Water in ]. Peninsular area in India surrounded by water is "Dravida". | |||

| * Karnataka | |||

| * Telugu | |||

| * Dravida (Tamil Nadu & Kerala) | |||

| * Maharashtra | |||

| * Gujarat | |||

| Many 18th and 19th century Brahmins are credited with religious movements that criticised ]. For example, the Brahmins ] led ] and ] led the ].<ref>Noel Salmond (2004), Hindu iconoclasts: Rammohun Roy, Dayananda Sarasvati and nineteenth-century polemics against idolatry, Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press, {{ISBN|0-88920-419-5}}, pages 65–68</ref><ref>Dorothy Figueira (2002), Aryans, Jews, Brahmins: Theorizing Authority through Myths of Identity, State University of New York Press, {{ISBN|978-0-7914-5531-9}}, pages 90–117</ref> | |||

| ===Andhra Pradesh=== | |||

| {{unreferenced section|date=November 2013}} | |||

| Brahmins of Andhra Pradesh known as ] are broadly classified into five groups: ], ],], ], and ]. | |||

| ==Outside the Indian subcontinent== | |||

| ]s are further divided into the following subcategories: Nandavarika Niyogi, Prathama Shakha Niyogi, Aaru Vela Niyogulu, Karanaalu, Sistukaranalu, Karana kamma vyaparlu, Karanakammulu. | |||

| {{further|Hinduism in Southeast Asia}} | |||

| ], Indonesia, Brahmins are called ''Pedandas''.<ref>Martin Ramstedt (2003), Hinduism in Modern Indonesia, Routledge, {{ISBN|978-0-7007-1533-6}}, page 256</ref> The role of Brahmin priests, called ''Sulinggih'',<ref>Martin Ramstedt (2003), Hinduism in Modern Indonesia, Routledge, {{ISBN|978-0-7007-1533-6}}, page 80</ref> has been open to both genders since medieval times. A Hindu Brahmin priestess is shown above.]] | |||

| ===Maharashtra=== | |||

| Some Brahmins formed an influential group in Burmese Buddhist kingdoms in 18th- and 19th-century. The court Brahmins were locally called ''Punna''.<ref name="leider"/> During the ], Buddhist kings relied on their court Brahmins to consecrate them to kingship in elaborate ceremonies, and to help resolve political questions.<ref name="leider">{{cite journal |last=Leider |first=Jacques P. |year= 2005|title=Specialists for Ritual, Magic and Devotion: The Court Brahmins of the Konbaung Kings |journal=The Journal of Burma Studies |volume=10 |pages=159–180 |doi=10.1353/jbs.2005.0004|s2cid=162305789 }}</ref> This role of Hindu Brahmins in a Buddhist kingdom, states Leider, may have been because Hindu texts provide guidelines for such social rituals and political ceremonies, while Buddhist texts do not.<ref name="leider"/> | |||

| {{See also|Chitpavan Konkanastha Brahmin|Deshastha Brahmin|Karhade Brahmin}} | |||

| The Brahmins were also consulted in the transmission, development and maintenance of law and justice system outside India.<ref name="leider"/> Hindu ], particularly Manusmriti written by the Prajapati Manu, states Anthony Reid,<ref name=reidseasia/> were "greatly honored in Burma (Myanmar), Siam (Thailand), Cambodia and Java-Bali (Indonesia) as the defining documents of law and order, which kings were obliged to uphold. They were copied, translated and incorporated into local law code, with strict adherence to the original text in Burma and Siam, and a stronger tendency to adapt to local needs in Java (Indonesia)".<ref name=reidseasia>Anthony Reid (1988), Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450–1680: The lands below the winds, Yale University Press, {{ISBN|978-0-300-04750-9}}, pages 137–138</ref><ref>Victor Lieberman (2014), Burmese Administrative Cycles, Princeton University Press, {{ISBN|978-0-691-61281-2}}, pages 66–68; Also see discussion of 13th century Wagaru Dhamma-sattha / 11th century Manu Dhammathat manuscripts discussion</ref><ref>On Laws of Manu in 14th century Thailand's ] named after ], see David Wyatt (2003), Thailand: A Short History, Yale University Press, {{ISBN|978-0-300-08475-7}}, page 61;<br />Robert Lingat (1973), The Classical Law of India, University of California Press, {{ISBN|978-0-520-01898-3}}, pages 269–272</ref> | |||

| During the days of ], these Marathi/Konkani Brahmins primarily served as prime ministers or ]s,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.websters-online-dictionary.org/definitions/Peshwa |title=Dictionary - Definition of Peshwa |publisher=Websters-online-dictionary.org |date= |accessdate=2013-03-23}}</ref> apart from taking up military jobs and converged into the sovereign or the ]. One of the notable Peshwa families is the Bhat family, who happen to be ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/453390/peshwa |title=peshwa (Maratha chief minister) - Britannica Online Encyclopedia |publisher=Britannica.com |date= |accessdate=2013-03-23}}</ref> They took up military jobs<ref name="hindujagruti.org">{{cite web|url=http://www.hindujagruti.org/articles/30.html |title=Shrimant Bajirao Peshwa : Great warrior and protector of Hindu Dharma - Valiant Hindu Kings | Hindu Janajagruti Samiti |publisher=Hindujagruti.org |date= |accessdate=2013-03-23}}</ref> and ended up being the de facto head<ref>{{cite book|url=http://books.google.co.in/books?id=SYOSHaZnBy8C&pg=PA129&dq=peshwa+de+facto+head&hl=en&sa=X&ei=e3_yUMXhH4bZrQeSyoHYDQ&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=peshwa%20de%20facto%20head&f=false |title=The Satara Raj, 1818-1848: A Study in History, Administration, and Culture - Sumitra Kulkarni - Google Books |publisher=Books.google.co.in |date= |accessdate=2013-03-23}}</ref> of the ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/285248/India/46988/Rise-of-the-peshwas |title=India : Rise of the peshwas - Britannica Online Encyclopedia |publisher=Britannica.com |date=2011-11-08 |accessdate=2013-03-23}}</ref> | |||

| Originally the ] held a low rank in the social hierarchy amongst Marathi Brahmins, however in modern times they enjoy the same social ranking with ] and ] Brahmins, inter-marriages between these three communities is now very common. | |||

| The mythical origins of ] are credited to a Brahmin prince named Kaundinya, who arrived by sea, married a Naga princess living in the flooded lands.<ref name=trevorranges48/><ref>Jonathan Lee and Kathleen Nadeau (2010), Encyclopedia of Asian American Folklore and Folklife, Volume 1, ABC, {{ISBN|978-0-313-35066-5}}, page 1223</ref> Kaudinya founded Kambuja-desa, or Kambuja (transliterated to Kampuchea or Cambodia). Kaundinya introduced Hinduism, particularly Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva and Harihara (half Vishnu, half Shiva), and these ideas grew in southeast Asia in the 1st millennium CE.<ref name=trevorranges48>Trevor Ranges (2010), Cambodia, National Geographic, {{ISBN|978-1-4262-0520-0}}, page 48</ref> | |||

| The ''] Balamon'' (Hindu Brahmin Chams) form a majority of the Cham population in ].<ref name="Sơn p.105">Champa and the archaeology of Mỹ Sơn (Vietnam) By Andrew Hardy, Mauro Cucarzi, Patrizia Zolese p.105</ref> | |||

| Brahmins have been part of the Royal tradition of ], particularly for the consecration and to mark annual land fertility rituals of Buddhist kings. A small Brahmanical temple ], established in 1784 by King ] of Thailand, has been managed by ethnically Thai Brahmins ever since.<ref name=wales54/> The temple hosts ''Phra Phikhanesuan'' (Ganesha), ''Phra Narai'' (Narayana, Vishnu), ''Phra Itsuan'' (Shiva), ], ], ] (''Sakka'') and other Hindu deities.<ref name=wales54>HG Quadritch Wales (1992), , Curzon Press, {{ISBN|978-0-7007-0269-5}}, pages 54–63</ref> The tradition asserts that the Thai Brahmins have roots in Hindu holy city of Varanasi and southern state of Tamil Nadu, go by the title ''Pandita'', and the various annual rites and state ceremonies they conduct has been a blend of Buddhist and Hindu rituals. The ] of the ] is almost entirely conducted by the royal Brahmins.<ref name=wales54/><ref>Boreth Ly (2011), Early Interactions Between South and Southeast Asia (Editors: Pierre-Yves Manguin, A. Mani, Geoff Wade), Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, {{ISBN|978-981-4311-16-8}}, pages 461–475</ref> | |||

| ==Modern demographics== | |||

| ] | |||

| According to 2007 reports, Brahmins in India are about five per cent of its total population.<ref name="bellmanwsj">{{cite news |last1=Bellman |first1=Eric |title=Reversal of Fortune Isolates India's Brahmins |url=https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB119889387595256961 |access-date=21 June 2022 |newspaper=] |date=30 December 2007 |archive-date=10 June 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220610055905/https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB119889387595256961 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="outlookbgraph">{{cite magazine|url=http://www.outlookindia.com/article/brahmins-in-india/234783 |title=Brahmins In India |magazine=Outlook India |date=4 June 2007 |access-date=21 June 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140531222946/https://www.outlookindia.com/article/brahmins-in-india/234783 |archive-date=31 May 2014}}</ref> | |||

| The Himalayan states of ] (20%) and ] (14%) have the highest percentage of Brahmin population relative to respective state's total Hindus.<ref name="outlookbgraph" /> | |||

| According to the Center for the Study of Developing Societies, in 2004 about 65% of Brahmin households in India earned less than $100 a month compared to 89% of ], 91% of ] and 86% of Muslims.<ref name="bellmanwsj" /> | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| {{Div col}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| * ] and ] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| {{div col end}} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{Reflist|30em}} | |||

| ==Sources== | |||

| {{refbegin}} | |||

| <!-- --> | |||

| * {{cite book | last =Narasimhacharya | first =Ramanujapuram | year =1999 | title =The Buddha-Dhamma, Or, the Life and Teachings of the Buddha | publisher =Asian Educational Services}} | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| * ], Kashi Ki Panditya Parampara, Sharda Sansthan, ], 1985. | |||

| * ], Rulers, Townsmen, and Bazaars: North Indian Society in the Age of British Expansion, 1770–1870, ], 1983. | |||

| * Anand A. Yang, Bazaar India: Markets, Society, and the Colonial State in Bihar, ], 1999. | |||

| * ], Social Change in Modern India, ], ], 1995. | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{Commons category|Brahmins}} | |||

| * | |||

| {{Wikiquote}} | |||

| * | |||

| * , An appeal and record of colonial era conflict in Bengal | |||

| * | |||

| * , Friedrich Ruckert (translated from German by Charles Brooks) | |||

| {{Brahmin communities}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

Revision as of 14:29, 7 November 2024

Varna in Hinduism, one of four castes Not to be confused with Brahman (a metaphysical concept in Hinduism), Brahma (a Hindu god), Brahmana (a layer of text in the Vedas), or Brahmi script. For other uses, see Brahmin (disambiguation).

Brahmin (/ˈbrɑːmɪn/; Sanskrit: ब्राह्मण, romanized: brāhmaṇa) is a varna (caste) within Hindu society. The other three varnas are the Kshatriya, Vaishya, and Shudra. The traditional occupation of Brahmins is that of priesthood (purohit, pandit, or pujari) at Hindu temples or at socio-religious ceremonies, and the performing of rite of passage rituals, such as solemnising a wedding with hymns and prayers.

Traditionally, Brahmins are accorded the highest ritual status of the four social classes, and they also served as spiritual teachers (guru or acharya). In practice, Indian texts suggest that some Brahmins historically also became agriculturalists, warriors, traders, and had also held other occupations in the Indian subcontinent.

Origin and history

A Brahmin soldier

A Brahmin soldier Four ascetic Brahmins from Gandhara, 2nd century

Four ascetic Brahmins from Gandhara, 2nd century A Brahmin family, 9th century. Prambanan, Indonesia.

A Brahmin family, 9th century. Prambanan, Indonesia. A Brahmin standing praying in the corner of the streets. India, 1863.

A Brahmin standing praying in the corner of the streets. India, 1863. Brahmin Officers from 1st Brahmans Infantry Regiment

Brahmin Officers from 1st Brahmans Infantry Regiment Maharaja Lakhmeshwar Singh statue

Maharaja Lakhmeshwar Singh statue Ancient Indian economist and military strategist ChanakyaFile:Aryabhata-5 (1).jpgAncient Indian mathematician and astronomer Aryabhatta

Ancient Indian economist and military strategist ChanakyaFile:Aryabhata-5 (1).jpgAncient Indian mathematician and astronomer Aryabhatta

It seems likely that Kannauj and Middle country was the place of origin of majority of migrating Brahmins throughout the medieval centuries. Coming from Kannauj is a frequent claim among Brahmins in areas distant from Madhyadesha or Ganges heartland.

Generic meaning of the term "Brahmin"

The term Brahmin appears extensively in ancient and medieval Sutras and commentary texts of Buddhism and Jainism. Modern scholars state that such usage of the term Brahmin in ancient texts does not imply a caste, but simply "masters" (experts), guardian, recluse, preacher or guide of any tradition. An alternate synonym for Brahmin in the Buddhist and other non-Hindu tradition is Mahano.

Strabo cites Megasthenes, highlighting two Indian philosophical schools Sramana and Brahmana:

Megasthenes makes a different division of the philosophers, saying that they are of two kinds, one of which he calls the Brachmanes, and the other the Sarmanes...

— Strabo XV. 1. 58-60

Patrick Olivelle states that both Buddhist and Brahmanical literature repeatedly define "Brahmin" not in terms of family of birth, but in terms of personal qualities. These virtues and characteristics mirror the values cherished in Hinduism during the Sannyasa stage of life, or the life of renunciation for spiritual pursuits. Brahmins, states Olivelle, were the social class from which most ascetics came. The term Brahmin in Indian texts has also signified someone who is good and virtuous, not just someone of priestly class.

Purusha sukta

The earliest inferred reference to "Brahmin" as a possible social class is in the Rigveda, occurs once, and the hymn is called Purusha Sukta. According to a hymn in Mandala 10, Rigveda 10.90.11-2, Brahmins are described as having emerged from the mouth of Purusha, being that part of the body from which words emerge.

The Purusha Sukta varna verse is now generally considered to have been inserted at a later date into the Vedic text, possibly as a charter myth. Stephanie Jamison and Joel Brereton, a professor of Sanskrit and Religious studies, state, "there is no evidence in the Rigveda for an elaborate, much-subdivided and overarching caste system", and "the varna system seems to be embryonic in the Rigveda and, both then and later, a social ideal rather than a social reality".

According to Vijay Nath, in the Markandeya Purana (250 CE), there are references to Brahmins who were born into the families of Raksasas. He posits that this is an indication that some Brahmins are immigrants and some are also mixed.

Gupta era

According to Abraham Eraly, "Brahmin as a varna hardly had any presence in historical records before the Gupta Empire era" (3rd century to 6th century CE), when Buddhism dominated the land. "No Brahmin, no sacrifice, no ritualistic act of any kind ever, even once, is referred to" in any Indian texts between third century BCE and the late first century CE. He also states that "The absence of literary and material evidence, however, does not mean that Brahmanical culture did not exist at that time, but only that it had no elite patronage and was largely confined to rural folk, and therefore went unrecorded in history". Their role as priests and repository of sacred knowledge, as well as their importance in the practice of Vedic Shrauta rituals, grew during the Gupta Empire era and thereafter.

However, the knowledge about actual history of Brahmins or other varnas of Hinduism in and after the first millennium is fragmentary and preliminary, with little that is from verifiable records or archaeological evidence, and much that is constructed from ahistorical Sanskrit works and fiction. Michael Witzel writes:

Current research in the area is fragmentary. The state of our knowledge of this fundamental subject is preliminary, at best. Most Sanskrit works are a-historic or, at least, not especially interested in presenting a chronological account of India's history. When we actually encounter history, such as in Rajatarangini or in the Gopalavamsavali of Nepal, the texts do not deal with brahmins in great detail.

Gauda and Dravida Brahmins

According to Kalhana's Rajatarangini (12th cent. CE) and Sahyadrikhanda (5th–13th cent. CE) of Skandapurana, Brahmins are broadly classified into two groups based on geography. The northern Pancha Gauda group comprises five Brahmin communities, as mentioned in the text, residing north of the Vindhya mountain range. Historically, the Vindhya mountain range formed the southern boundary of the Āryāvarta, the territory of the ancient Indo-Aryan peoples, and Gauda has territorial, ethnographic and linguistic connotations. Linguistically, the term "Gauda" refers to the Sanskrit-derived languages of northern India. The Pancha Gauda Brahmins are:

Subcastes of Gaur Brahmins are:

- Sanadhya

- Paliwal

Subcastes of Kanyakubja Brahmins are:

- Jujhatiya Brahmin

- Saryupareen Brahmin

- Bengali Kulin Brahmin

- Anavil Brahmins ( Though they are generally not accepted as Brahmins)

- Khas Brahmins – Nepali Bahuns

The Pancha Dravida Brahmins reside to the south of the Vindhya mountain range. The term "Dravida" too has territorial, linguistic and ethnological connotations, referring to southern India, the Dravidian people, and to the Dravidian languages of southern India. The Pancha Dravida Brahmins are:

- Karnataka (Karnataka Brahmins)

- Tailanga (Telugu Brahmins)

- Dravida (Brahmins of Tamil Nadu and Kerala)

- Maharashtraka (Maharashtrian Brahmins)

- Gurjara (Gujarati)

Role in the society

Vedic duties

The Dharmasutra and Dharmashastra texts of Hinduism describe the expectations, duties and role of Brahmins.

According to Kulkarni, the Grhya-sutras state that Yajna, Adhyayana (studying the vedas and teaching), dana pratigraha (accepting and giving gifts) are the "peculiar duties and privileges of brahmins". John Bussanich states that the ethical precepts set for Brahmins, in ancient Indian texts, are similar to Greek virtue-ethics, that "Manu's dharmic Brahmin can be compared to Aristotle's man of practical wisdom", and that "the virtuous Brahmin is not unlike the Platonic-Aristotelian philosopher" with the difference that the latter was not sacerdotal.

The Brahmins were expected to perform all six Vedic duties as opposed to other twice-borns who performed three.

| Adhyayan (Study Vedas) |

Yajana (performing sacrifice for one's own benefit) |

Dana (Giving Gifts) |

Adhyapana (Teaching Vedas) |

Yaajana (Acting as Priest for sacrifice) |

Pratigraha (accepting gifts) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brahmin | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Kshatriya | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | No | No | No |

| Vaishya | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | No | No | No |

Actual occupations

Historical records, state scholars, suggest that Brahmin varna was not limited to a particular status or priest and the teaching profession. Chanakya, a Brahmin born in 375 BCE, was an ancient Indian polymath who was active as a teacher, author, strategist, philosopher, economist, jurist, and royal advisor, who assisted the first Mauryan emperor Chandragupta Maurya in his rise to power and is widely credited for having played an important role in the establishment of the Maurya Empire. Historical records from mid 1st millennium CE and later, suggest Brahmins were agriculturalists and warriors in medieval India, quite often instead of as exception. Donkin and other scholars state that Hoysala Empire records frequently mention Brahmin merchants who "carried on trade in horses, elephants and pearls" and transported goods throughout medieval India before the 14th-century.

The Pāli Canon depicts Brahmins as the most prestigious and elite non-Buddhist figures. They mention them parading their learning. The Pali Canon and other Buddhist texts such as the Jataka Tales also record the livelihood of Brahmins to have included being farmers, handicraft workers and artisans such as carpentry and architecture. Buddhist sources extensively attest, state Greg Bailey and Ian Mabbett, that Brahmins were "supporting themselves not by religious practice, but employment in all manner of secular occupations", in the classical period of India. Some of the Brahmin occupations mentioned in the Buddhist texts such as Jatakas and Sutta Nipata are very lowly. The Dharmasutras too mention Brahmin farmers.

According to Haidar and Sardar, unlike the Mughal Empire in Northern India, Brahmins figured prominently in the administration of Deccan sultanates. Under Golconda Sultanate Telugu Niyogi Brahmins served in many different roles such as accountants, ministers, in the revenue administration, and in the judicial service. The Deccan sultanates also heavily recruited Marathi Brahmins at different levels of their administration. During the days of Maratha Empire in the 17th and 18th century, the occupation of Marathi Brahmins ranged from being state administrators, being warriors to being de facto rulers as Peshwa. After the collapse of Maratha empire, Brahmins in Maharashtra region were quick to take advantage of opportunities opened up by the new British rulers. They were the first community to take up Western education and therefore dominated lower level of British administration in the 19th century. Similarly, the Tamil Brahmins were also quick to take up English education during British colonial rule and dominate government service and law.

Eric Bellman states that during the Islamic Mughal Empire era Brahmins served as advisers to the Mughals, later to the British Raj. The East India Company also recruited sepoys (soldiers) from the Brahmin communities of Bihar and Awadh (in the present day Uttar Pradesh) for the Bengal army. Many Brahmins, in other parts of South Asia lived like other varna, engaged in all sorts of professions. Among Nepalese Hindus, for example, Niels Gutschow and Axel Michaels report the actual observed professions of Brahmins from 18th- to early 20th-century included being temple priests, ministers, merchants, farmers, potters, masons, carpenters, coppersmiths, stone workers, barbers, and gardeners, among others.

Other 20th-century surveys, such as in the state of Uttar Pradesh, recorded that the primary occupation of almost all Brahmin families surveyed was neither priestly nor Vedas-related, but like other varnas, ranged from crop farming (80 per cent of Brahmins), dairy, service, labour such as cooking, and other occupations. The survey reported that the Brahmin families involved in agriculture as their primary occupation in modern times plough the land themselves, many supplementing their income by selling their labour services to other farmers.

Bhakti movement and Social Reform movements

Many of the prominent thinkers and earliest champions of the Bhakti movement were Brahmins, a movement that encouraged a direct relationship of an individual with a personal god. Among the many Brahmins who nurtured the Bhakti movement were Ramanuja, Nimbarka, Vallabha and Madhvacharya of Vaishnavism, Ramananda, another devotional poet sant. Born in a Brahmin family, Ramananda welcomed everyone to spiritual pursuits without discriminating anyone by gender, class, caste or religion (such as Muslims). He composed his spiritual message in poems, using widely spoken vernacular language rather than Sanskrit, to make it widely accessible. The Hindu tradition recognises him as the founder of the Hindu Ramanandi Sampradaya, the largest monastic renunciant community in Asia in modern times.

Other medieval era Brahmins who led spiritual movements without social or gender discrimination included Andal (9th-century female poet), Basava (12th-century Lingayatism), Dnyaneshwar (13th-century Bhakti poet), Vallabha Acharya (16th-century Vaishnava poet), Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (14th-century Vaishnava saint) were among others.

Many 18th and 19th century Brahmins are credited with religious movements that criticised idolatry. For example, the Brahmins Raja Ram Mohan Roy led Brahmo Samaj and Dayananda Saraswati led the Arya Samaj.

Outside the Indian subcontinent

Further information: Hinduism in Southeast Asia

Some Brahmins formed an influential group in Burmese Buddhist kingdoms in 18th- and 19th-century. The court Brahmins were locally called Punna. During the Konbaung dynasty, Buddhist kings relied on their court Brahmins to consecrate them to kingship in elaborate ceremonies, and to help resolve political questions. This role of Hindu Brahmins in a Buddhist kingdom, states Leider, may have been because Hindu texts provide guidelines for such social rituals and political ceremonies, while Buddhist texts do not.

The Brahmins were also consulted in the transmission, development and maintenance of law and justice system outside India. Hindu Dharmasastras, particularly Manusmriti written by the Prajapati Manu, states Anthony Reid, were "greatly honored in Burma (Myanmar), Siam (Thailand), Cambodia and Java-Bali (Indonesia) as the defining documents of law and order, which kings were obliged to uphold. They were copied, translated and incorporated into local law code, with strict adherence to the original text in Burma and Siam, and a stronger tendency to adapt to local needs in Java (Indonesia)".

The mythical origins of Cambodia are credited to a Brahmin prince named Kaundinya, who arrived by sea, married a Naga princess living in the flooded lands. Kaudinya founded Kambuja-desa, or Kambuja (transliterated to Kampuchea or Cambodia). Kaundinya introduced Hinduism, particularly Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva and Harihara (half Vishnu, half Shiva), and these ideas grew in southeast Asia in the 1st millennium CE.

The Chams Balamon (Hindu Brahmin Chams) form a majority of the Cham population in Vietnam.

Brahmins have been part of the Royal tradition of Thailand, particularly for the consecration and to mark annual land fertility rituals of Buddhist kings. A small Brahmanical temple Devasathan, established in 1784 by King Rama I of Thailand, has been managed by ethnically Thai Brahmins ever since. The temple hosts Phra Phikhanesuan (Ganesha), Phra Narai (Narayana, Vishnu), Phra Itsuan (Shiva), Uma, Brahma, Indra (Sakka) and other Hindu deities. The tradition asserts that the Thai Brahmins have roots in Hindu holy city of Varanasi and southern state of Tamil Nadu, go by the title Pandita, and the various annual rites and state ceremonies they conduct has been a blend of Buddhist and Hindu rituals. The coronation ceremony of the Thai king is almost entirely conducted by the royal Brahmins.

Modern demographics

16–20% 12–16% 9–12% 4–8% 1–4% 0–1%

According to 2007 reports, Brahmins in India are about five per cent of its total population.

The Himalayan states of Uttarakhand (20%) and Himachal Pradesh (14%) have the highest percentage of Brahmin population relative to respective state's total Hindus.

According to the Center for the Study of Developing Societies, in 2004 about 65% of Brahmin households in India earned less than $100 a month compared to 89% of Scheduled Tribes, 91% of Scheduled Castes and 86% of Muslims.

See also

- Viswa Brahman Diwas

- Vedic priesthood

- Brahmavarta

- List of Brahmins

- List of Brahmin dynasties and states

- 1st Brahman Regiment and 3rd Brahman Regiment

- Brahmin Tamil

- Historical Vedic religion

References

- Benjamin Lee Wren (2004). Teaching World Civilization with Joy and Enthusiasm. University Press of America. pp. 77–. ISBN 978-0-7618-2747-4.

At the top were the Brahmins(priests), then the Kshatriyas(warriors), then the vaishya(the merchant class which only in India had a place of honor in Asia), next were the sudras(farmers), and finally the pariah(untouchables), or those who did the dirty defiling work

- Kenneth R. Valpey (2 November 2019). Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics. Springer Nature. pp. 169–. ISBN 978-3-03-028408-4.

The four varnas are the brahmins (brahmanas—priests, teachers); kshatriyas (ksatriyas—administrators, rulers); vaishyas (vaisyas—farmers, bankers, business people); and shudras(laborers, artisans)

- Richard Bulliet; Pamela Crossley; Daniel Headrick; Steven Hirsch; Lyman Johnson (11 October 2018). The Earth and Its Peoples: A Global History, Volume I. Cengage Learning. pp. 172–. ISBN 978-0-357-15937-8.

Varna are the four major social divisions: the Brahmin priest class, the Kshatriya warrior/ administrator class, the Vaishya merchant/farmer class, and the Shudra laborer class.

- Akira Iriye (1979). The World of Asia. Forum Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-88273-500-9.

The four varna groupings in descending order of their importance came to be Brahmin (priests), Kshatriya (warriors and administrators), Vaishya (cultivators and merchants), and Sudra (peasants and menial laborers)

- ^ Ludo Rocher (2014). "9.Caste and occupation in classical India: The normative texts". In Donald R. Davis Jr. (ed.). Studies in Hindu Law and Dharmaśāstra. Anthem Press. pp. 205–206. ISBN 9781783083152.

- James Lochtefeld (2002), Brahmin, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A–M, Rosen Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8, page 125

- ^ GS Ghurye (1969), Caste and Race in India, Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-81-7154-205-5, pages 15–18

- ^ Doniger, Wendy (1999). Merriam-Webster's encyclopedia of world religions. Springfield, MA, US: Merriam-Webster. pp. 141–142, 186. ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0.

- ^ David Shulman (1989), The King and the Clown, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-00834-9, page 111

- Wink, André (2020). The Making of the Indo-Islamic World C.700–1800 CE. E.J. Brill. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-108-41774-7.

- Thapar, Romila (2008). Somanatha. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-93-5118-021-0.

- Donald Lopez (2004). Buddhist Scriptures. Penguin Books. pp. xi–xv. ISBN 978-0-14-190937-0.

- ^ Padmanabh S. Jaini (2001). Collected Papers on Buddhist Studies. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 123. ISBN 978-81-208-1776-0.

- K N Jayatilleke (2013). Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge. Routledge. pp. 141–154, 219, 241. ISBN 978-1-134-54287-1.

- Kailash Chand Jain (1991). Lord Mahāvīra and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 31. ISBN 978-81-208-0805-8. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- "Strabo XV.1". Perseus.tufts.edu. Archived from the original on 27 December 2007. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ^ Patrick Olivelle (2011), Ascetics and Brahmins: Studies in Ideologies and Institutions, Anthem, ISBN 978-0-85728-432-7, page 60

- Max Müller, A History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature, Oxford University Press, pages 570–571

- Thapar, Romila (2004). Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. University of California Press. p. 125. ISBN 9780520242258.

- ^ Jamison, Stephanie; et al. (2014). The Rigveda: the earliest religious poetry of India. Oxford University Press. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-0-19-937018-4.

- Nath, Vijay (2001). "From 'Brahmanism' to 'Hinduism': Negotiating the Myth of the Great Tradition". Social Scientist. 29 (3/4): 25. doi:10.2307/3518337. ISSN 0970-0293. JSTOR 3518337.

- ^ Abraham Eraly (2011), The First Spring: The Golden Age of India, Penguin, ISBN 978-0-670-08478-4, page 283

- Michael Witzel (1993) Toward a History of the Brahmins Archived 1 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 113, No. 2, pages 264–268

- ^ James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: N-Z. Rosen. p. 491. ISBN 9780823931804.

- D. Shyam Babu and Ravindra S. Khare, ed. (2011). Caste in Life: Experiencing Inequalities. Pearson Education India. p. 168. ISBN 9788131754399.

- ^ Narasimhacharya (1999), p. 8.

- Bahadur, K. P. (1976). Selection From Ramachndrika Of Keshv. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-2789-9.

- "This community does not believe in the tradition". The Times of India. 26 August 2018. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ Sherring, Matthew Atmore (1977). Hindu Tribes and Castes Volume 1. Thacker, spink and company.

- Wink, André (1990). Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: The slave kings and the Islamic conquest, 11th–13th centuries. E.J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09249-5.

- Bhāratīya sāhitya, Volume 19. Agra University. K.M. Institute of Hindi Studies and Linguistics. 1974.

- Chaturvedi, Shyam lal (Rai bahadur) (1945). In Fraternity with Nepal, An Account of the Activities Under the Auspices of the Wider Life Movement for the Furtherance and Consolidation of the Indo-Nepalese Cultural Fellowship. p. 65.

- Pandya, A V (1952). Abu in Bombay State: A Scientific Study of the Problem. Charutar Vidya Mandal. p. 29.

It is interesting to note here that the Brahmin groups of Marwar and Mewar belong to the Gurjara group of the Pancha Dravida division