| Revision as of 17:53, 8 May 2005 editSimonP (talk | contribs)Administrators113,127 editsm {{History of Europe}}← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 12:00, 12 November 2024 edit undo2a0a:ef40:3d3:3901:a122:910b:ad40:41c3 (talk) Added link to the Thaïs Bone.Tag: Visual edit | ||

| (841 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|none}} <!-- "none" is preferred when the title is sufficiently descriptive; see ] --> | |||

| == Paleolithic == | |||

| {{Infobox | |||

| |name = Prehistoric Europe | |||

| |bodystyle = off the books | |||

| |titlestyle = background:#bee5fe; | |||

| |abovestyle = background:#fcfebe; border:1px solid #5599FF; | |||

| |headerstyle = background:#ddf; | |||

| |labelstyle = background:#ddf; | |||

| |datastyle = | |||

| |title = '''Prehistoric Europe''' | |||

| |above = | |||

| |imagestyle = | |||

| |captionstyle = | |||

| |image = | |||

| |caption = | |||

| |map_type = Europe 2 | |||

| |relief = yes | |||

| |header1 = '''Early Prehistory''' | |||

| |label1 = | |||

| |data1 = | |||

| |header2 = | |||

| |label2 = ] | |||

| |data2 = ]<ref>{{cite web |url=http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/june-2013/article/oldest-human-fossil-in-western-europe-found-in-spain |title=Oldest Human Fossil in Western Europe Found in Spain |newspaper=Popular-archaeology |access-date= December 28, 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Carbonell |first1=Eudald |display-authors=etal |title=The first hominin of Europe |journal=Nature |date=27 March 2008 |volume=452 |issue=7186 |pages=465–469 |doi=10.1038/nature06815|pmid=18368116 |bibcode=2008Natur.452..465C |hdl=2027.42/62855 |s2cid=4401629 |url=https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/2027.42/62855/1/nature06815.pdf }}</ref><br>] | |||

| |header3 = | |||

| |label3 =] | |||

| |data3 = ] | |||

| |header4 = | |||

| |label4 =] | |||

| |data4 = ], ] population of all regions | |||

| |header5 = | |||

| |label5 = ] | |||

| |data5 = Hunter-gatherers | |||

| |header6 = | |||

| |label6 = ] | |||

| |data6 = Agriculture,<br> herding, pottery | |||

| |header7 = '''Late Prehistory''' | |||

| |label7 = | |||

| |data7 = | |||

| |header8 = | |||

| |label8 = ] | |||

| |data8 = ], ], ] | |||

| |header9 = | |||

| |label9 = ] | |||

| |data9 = ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| |header10 = | |||

| |label10 = ] | |||

| |data10 = ], ], ], <br>], ], ] | |||

| |belowstyle = background:#fcfebe; | |||

| |below = {{portal-inline|Europe|size=tiny}} | |||

| }} | |||

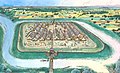

| ], ], around 3150 BC]] | |||

| '''Upper ]:''' | |||

| Europe was populated by species of '']'' since c. 900,000 years ago ('']''), associated with the '']'' technology and later to the ] one (since c. 300,000 BP). | |||

| '''Prehistoric Europe''' refers to ] before the start of written records,<ref>{{cite web |url=https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/prehistory |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160925201126/https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/prehistory |url-status=dead |archive-date=September 25, 2016 |title=Prehistory – definition of prehistory in English |publisher=oxford dictionaries |access-date= December 28, 2016}}</ref> beginning in the ]. As history progresses, considerable regional unevenness in cultural development emerges and grows. The region of the eastern Mediterranean is, due to its geographic proximity, greatly influenced and inspired by the classical Middle Eastern civilizations, and adopts and develops the earliest systems of communal organization and writing.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ancientscripts.com/lineara.html |title=Ancient Scripts: Linear A |newspaper=Ancientscripts.com |access-date= December 29, 2016}}</ref> The ] of Herodotus (from around 440 BC) is the oldest known European text that seeks to systematically record traditions, public affairs and notable events.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.history.com/topics/ancient-history/herodotus |title=Herodotus – Ancient History |publisher=History com |access-date= December 29, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| '''Middle Paleolithic:''' | |||

| Eventually these European ''Homo erectus'' evolved into another species: '']'' (since c. 200,000 BP), associated with the ] technologies. It must be noted that our ancestors '']'' also participated in this tool-making technique for a long time and they may have first settled Europe while this Mid-Paleolithic technique was still in use, though the issue is still unclear. | |||

| ==Overview== | |||

| '''Upper Paleolithic:''' | |||

| {{See also|History of Europe}} | |||

| Widely dispersed, isolated finds of individual fossils of bone fragments (Atapuerca, Mauer mandible), stone artifacts or ] suggest that during the ], spanning from 3 million until 300,000 years ago, palaeo-human presence was rare and typically separated by thousands of years. The ]ic region of the ] in Spain represents the currently earliest known and reliably dated location of residence for more than a single generation and a group of individuals.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/989%20Archeological%20Site%20of%20Atapuerca |title=Archaeological Site of Atapuerca |publisher= UNESCO World Heritage Centre |access-date= December 28, 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite news| url=https://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9E05E2D9113BF933A1575AC0A9619C8B63&scp=1&sq=dmanisi%201.8%20million&st=cse | work=The New York Times | title=Fossils Reveal Clues on Human Ancestor | date=20 September 2007}}</ref> | |||

| '']'' emerged in ] between 600,000 and 350,000 years ago as the earliest body of European people that left behind a substantial tradition, a set of evaluable historic data through a rich fossil record in Europe's limestone caves and a patchwork of occupation sites over large areas. These include ] cultural ].<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1006/jasc.2002.0834 |title=The Sima de los Huesos Hominids Date to Beyond U/Th Equilibrium (>350kyr) and Perhaps to 400–500kyr: New Radiometric Dates |year=2003 |last1=Bischoff |first1=James L. |last2=Shamp |first2=Donald D. |last3=Aramburu |first3=Arantza |last4=Arsuaga |first4=Juan Luis |last5=Carbonell |first5=Eudald |last6=Bermudez de Castro |first6=J.M. |journal=Journal of Archaeological Science |volume=30 |issue=3 |pages=275–80|bibcode=2003JArSc..30..275B }}</ref><ref name=Neanderthal>{{cite encyclopedia|url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Neanderthal |title=Neanderthal Anthropology|quote=...Neanderthals inhabited Eurasia from the Atlantic regions… |encyclopedia= Encyclopædia Britannica |date=January 29, 2015 |access-date=September 26, 2016}}</ref> ] arrived in Mediterranean Europe during the ] between 45,000 and 43,000 years ago, and both species occupied a common habitat for several thousand years. Research has so far produced no universally accepted conclusive explanation as to what caused the Neanderthal's extinction between 40,000 and 28,000 years ago.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/13/science/14neanderthal.html?ex=1315800000&en=ca90a9bfe57071f2&ei=5089&_r=0 |title=Neanderthals' Last Stand Is Traced |newspaper= The New York Times |date=September 13, 2006 |access-date=September 26, 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite news| url=https://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/03/science/fossil-teeth-put-humans-in-europe-earlier-than-thought.html?scp=1&sq=kents%20cavern&st=cse | work=The New York Times | title=Fossil Teeth Put Humans in Europe Earlier Than Thought | date=2 November 2011}}</ref> | |||

| '''· Ancient Upper Paleolithic:''' | |||

| What is totally clear is that the bearers of most or all Upper Paleolithic technologies were ''H. sapiens''. Some locally developed transitional cultures (] in Central Europe and ] in the Southwest) use clearly Upper Paleolithic technologies at very early dates and there are doubts abour who were their carriers: ''H. sapiens'' or Neanderthal man. | |||

| Homo sapiens later populated the entire continent during the ], and advanced north, following the retreating ice sheets of the ] that spanned between 26,500 and 19,000 years ago. A 2015 publication on ancient European DNA collected from Spain to Russia concluded that the original hunter-gatherer population had assimilated a wave of "farmers" who had arrived from the ] during the ] about 8,000 years ago.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/16/science/dna-deciphers-roots-of-modern-europeans.html?_r=1 |title=DNA Deciphers Roots of Modern Europeans |newspaper=The New York Times |date= June 10, 2015 |access-date= December 28, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| Nevertheless, the definitive advance of these technologies is made by the ] culture. The origins of this culture can be located in Bulgaria (proto-Aurignacian) and Hungary (first full Aurignacian). It's thought that peoples originating from the Near East were the carriers of the basics that gave birth to this culture. In any case by 35,000 BCE, the Aurignacian culture and its technology had extended through most of Europe. The last Neanderthals seem to have been forced to retreat during this process to the southern half of the ]. | |||

| The Mesolithic era site ] in modern-day ], the earliest documented ] community of Europe with permanent buildings, as well as monumental art, precedes by many centuries sites previously considered to be the oldest known. The community's year-round access to a food surplus prior to the introduction of agriculture was the basis for the sedentary lifestyle.<ref>{{cite journal |url=https://www.academia.edu/1558753 |title=Lepenski Vir – Schela Cladovei culture's chronology and its interpretation |journal=Brukenthal. Acta Musei |access-date= December 29, 2016|last1=Rusu |first1=Aurelian I. |date=January 2011 }}</ref> However, the earliest record for the adoption of elements of farming can be found in ], a community with close cultural ties.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.duncancaldwell.com/Site/Prehistory_Shows.html |title=Archaeological Exhibitions |publisher=Duncancaldwell |access-date= December 29, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| The first but scarce works of art appear during this phase. | |||

| Belovode and ], also in Serbia, is currently the oldest reliably dated copper smelting site in Europe (around 7,000 years ago). It is attributed to the ], which on the contrary provides no links to the initiation of or a transition to the ] or ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ucl.ac.uk/archaeology/calendar/articles/20100924 |title=Serbian site may have hosted first copper makers |publisher=UCL Institute of Archaeology |access-date= December 29, 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://cof.quantumfuturegroup.org/events/5439 |title=Early metallurgy: copper smelting, Belovode, Serbia: Vinča culture |newspaper=quantumfuturegroup.org |access-date= December 29, 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.penn.museum/documents/publications/expedition/PDFs/21-1/Jovanovic.pdf |title=The oldest Copper Metallurgy in the Balkans |publisher=Penn Museum |access-date= December 29, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| '''· Middle Upper Paleolithic:''' | |||

| Around 22,000 BCE two new technologies/cultures appear in the southwestern region of Europe: ] and ]. They might be linked with the transitional cultures mentioned before, because their techniques have some similarities and are both very different from Aurignacian ones but this issue is thus far very obscure. | |||

| The process of smelting bronze is an imported technology with debated origins and history of geographic cultural profusion. It was established in Europe about 3200 BC in the Aegean and production was centered around Cyprus, the primary source of copper for the Mediterranean for many centuries.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.historyworld.net/wrldhis/plaintexthistories.asp?historyid=ab16 |title=HISTORY OF METALLURGY |publisher=HistoryWorld.net |access-date= December 29, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| Though both cultures seem to appear in the SW, the Gravetian soon disappears there, with the notable exception of the Mediterranean coasts of Iberia. Nevertheless, it finds its way to other regions of Europe (Italy, Central and Eastern Europe), reaching even the Caucasus and the Zagros mountains. | |||

| The introduction of metallurgy, which initiated unprecedented technological progress, has also been linked with the establishment of social stratification, the distinction between rich and poor, and use of precious metals as the means to fundamentally control the dynamics of culture and society.<ref>{{cite journal |url=https://www.academia.edu/3231693 |title=The Development of Social Stratification in Bronze Age Europe (and Comments and Reply) |journal=Current Anthropology |volume=22 |issue=1 |pages=1–23 |publisher=Academia.edu |access-date= December 29, 2016|last1=Gilman |first1=Antonio |last2=Cazzella |first2=Alberto |last3=Cowgill |first3=George L. |last4=Crumley |first4=Carole L. |last5=Earle |first5=Timothy |last6=Gallay |first6=Alain |last7=Harding |first7=A. F. |last8=Harrison |first8=R. J. |last9=Hicks |first9=Ronald |last10=Kohl |first10=Philip L. |last11=Lewthwaite |first11=James |last12=Schwartz |first12=Charles A. |last13=Shennan |first13=Stephen J. |last14=Sherratt |first14=Andrew |last15=Tosi |first15=Maurizio |last16=Wells |first16=Peter S. |doi=10.1086/202600 |year=1981 |s2cid=145631324 }}</ref> | |||

| The Solutrean culture, extended from northern Spain to SE France, includes not only a beautiful stone technology but also the first significant development of cave painting, the use of the needle and possibly that of the bow and arrow. | |||

| The ] culture also originates in the East through the absorption of the technological principles obtained from the ] about 1200 BC, finally arriving in Northern Europe by 500 BC.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://study.com/academy/lesson/the-hittites-civilization-history-definition.html |title=The Hittites: Civilization, History & Definition |format= Video & Lesson Transcript |newspaper=Study.com |access-date= December 29, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| The more widespread Gravetian culture is no less advanced, at least in artistic terms: sculpture (mainly ''venuses'') is the most outstanding form of creative expression of these peoples. | |||

| During the Iron Age, Central, Western and most of Eastern Europe gradually entered the actual historical period. Greek maritime colonization and Roman terrestrial conquest form the basis for the diffusion of literacy in large areas to this day. This tradition continued in an altered form and context for the most remote regions (] and ], 13th century) via the universal body of Christian texts, including the incorporation of ] and Russia into the Orthodox cultural sphere. ] and ] languages continued to be the primary and best way to communicate and express ideas in ] and the sciences all over Europe until the early modern period.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Slomp |first1=Hans |title=Europe, A Political Profile: An American companion to European politics |page=50 |date=2011 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |isbn=978-0313391811 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=V1uzkNq8xfIC&q=Latin+and+ancient+Greek+influence+europe&pg=PA50}}</ref> | |||

| '''· Late Upper Paleolithic:''' | |||

| Around 17,000 BCE, Europe witnesses the appearance of a new culture, known as ], possibly rooted in the old Aurignacian one. This culture soon supersedes the Solutrean area and also the Gravetian of Central Europe. However, in Mediterranean Iberia, Italy and Eastern Europe, ] cultures continue evolving locally. | |||

| ==Stone Age== | |||

| With the Magdalenian culture, Paleolithic development in Europe reaches its peak and this is reflected in the amazing art, owing to the previous traditions: basically paintings in the West and sculpture in Central Europe. | |||

| ===Paleolithic (Old Stone Age)=== | |||

| {{Further|Paleolithic Europe}} | |||

| ====Oldest fossils, artifacts and sites==== | |||

| (Links to Paleolithic santuaries: | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center; margin: auto; width:96%" | |||

| · | |||

| |- | |||

| · ) | |||

| ! scope="row" style="width: 16%; font-size:100%; background:#fcfebe; color:#000000;"|Name !! scope="row" style="width: 16%; font-size:100%; background:#fcfebe; color:#000000;"|Abstract !! scope="row" style="width: 16%; font-size:100%; background:#fcfebe; color:#000000;"| Age !! scope="row" style="width: 16%; font-size:100%; background:#fcfebe; color:#000000;"|Location !! scope="row" style="width: 16%; font-size:100%; background:#fcfebe; color:#000000;"|Information !! scope="row" style="width: 16%; font-size:100%; background:#fcfebe; color:#000000;"|Coordinates | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || '']'' || 1.77 Mio || ] || "early Homo adult with small brains but large body mass" ||{{coord|41|19|N|44|12|E|display=inline|type:landmark}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ]<ref>{{cite web |url=https://anthropology.net/2009/12/16/lithic-assemblage-dated-to-1-57-million-years-found-at-lezignan-la-cebe-southern-france/ |title=Lithic Assemblage Dated to 1.57 Million Years Found at Lézignan-la-Cébe, Southern France |newspaper=Anthropology.net |date= 2009-12-17|access-date= December 30, 2016}}</ref> || ] ] || 1.57 Mio ||Lézignan-la-Cébe || a 30 pebble culture, lithic tools, argon dated || {{coord|43|29|N|3|26|E|display=inline|type:landmark}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ] cave || 1.5 Mio || ] || Human molar tooth (considered to be the earliest human—]/]—traces discovered in Europe outside Caucasian region), lower palaeolithic assemblages that belong to a ] non-] industry, and incised bones that may be the earliest example of human ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://vdcci.bg/kiosk/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=54:kozarnika-cave&catid=14:nature&Itemid=127&lang=en |title="Kozarnika" cave |publisher=VDCCI BG |access-date=September 5, 2016 |archive-date=September 15, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160915170614/http://vdcci.bg/kiosk/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=54:kozarnika-cave&catid=14:nature&Itemid=127&lang=en |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/3512470.stm |title=Early human marks are "symbols" |work=BBC News |date=March 16, 2004 |access-date=September 5, 2016}}</ref> ||{{coord|43|39|N|22|42|E|display=inline|type:landmark}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ]<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/homs/a_orce.html |title=Creationist Arguments: Orce Man |newspaper=Talkorigins |access-date= December 31, 2016}}</ref> || tooth and tools || 1.4 Mio || Venta Micena ||most finds are stone tools ||{{coord|37|43|N|2|28|W|display=inline|type:landmark}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ]<ref>{{cite journal |title=Early Pleistocene human mandible from Sima del Elefante (TE) cave site in Sierra de Atapuerca (Spain): a comparative morphological study |journal=Journal of Human Evolution |pmid=21531443 | doi=10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.03.005 |volume=61 |issue=1 |pages=12–25 | last1 = Bermúdez | last2 = de Castro | first2 = JM | last3 = Martinón-Torres | first3 = M | last4 = Gómez-Robles | first4 = A | last5 = Prado-Simón | first5 = L | last6 = Martín-Francés | first6 = L | last7 = Lapresa | first7 = M | last8 = Olejniczak | first8 = A | last9 = Carbonell | first9 = E|year=2011 }}</ref> || '']''||1.3 Mio || ] || ||{{coord|42|22|N|3|30|W|display=inline|type:landmark}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || '']'' ||600,000 || Mauer|| earliest '']'' ||{{coord|49|20|N|8|47|E|display=inline|type:landmark}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || '']'' || 500,000|| ]|| ||{{coord|50|51|N|0|42|W|display=inline|type:landmark}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || '']'' || 450,000 ||]|| ''proposed subspecies'' ||{{coord|42|48|N|2|45|E|display=inline|type:landmark}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] ||'']'' ||400,000 || ]|| ''north-western habitat maximum'' ||{{coord|51|26|N|0|17|E|display=inline|type:landmark}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ]<ref>{{cite journal |url=http://archive.archaeology.org/9705/newsbriefs/spears.html |title=World's Oldest Spears |journal=Archaeology |volume=50 |issue=3 |date=May–June 1997 |author=Arlette P. Kouwenhoven |access-date= December 30, 2016 }}</ref> || wooden javelins || 380,000 ||Schoningen 1995|| ''active hunt'' ||{{coord|42|48|N|2|45|E|display=inline|type:landmark}} | |||

| |} | |||

| ====Lower and Middle Paleolithic human presence==== | |||

| ] | |||

| Around 10,500 BCE, the ] Glacial age ends. Slowly, through the following millennia, temperatures and sea levels rise, changing the environment of prehistoric people. Nevertheless, Magdalenian culture persists until circa 8000 BCE, when it quickly evolves into two ''microlithist'' cultures: ], in Spain and southern France, and ], in northern France and Central Europe. Though there are some differences, both cultures share several traits: the creation of very small stone tools called ]s and the scarcity of figurative art, which seems to have vanished almost completely, being replaced by abstract decoration of tools. | |||

| The climatic record of the Paleolithic is characterised by the ] pattern of cyclic warmer and colder periods, including eight major cycles and numerous shorter episodes. The northern maximum of human occupation fluctuated in response to the changing conditions, and successful settlement required constant adaption capabilities and problem solving. Most of Scandinavia, the ] and Russia remained off limits for occupation during the Paleolithic and Mesolithic.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/history-of-Europe/Paleolithic-settlement |title=Paleolithic settlement |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica |access-date= December 31, 2016}}</ref> Populations were low in density and small in number throughout the Palaeolithic.<ref>{{Cite book |last=French |first=Jennifer |title=Palaeolithic Europe: A Demographic and Social Prehistory |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=2021 |url=https://www.cambridge.org/gb/universitypress/subjects/archaeology/prehistory/palaeolithic-europe-demographic-and-social-prehistory?format=PB |isbn=9781108710060 |location=UK |pages=1–18}}</ref> | |||

| Associated evidence, such as stone tools, artifacts and settlement localities, is more numerous than fossilised remains of the hominin occupants themselves. The simplest pebble tools with a few flakes struck off to create an edge were found in ], Georgia, and in Spain at sites in the ] basin and near ]. The ] tool discoveries, called ''Mode 1-type assemblages'' are gradually replaced by a more complex tradition that included a range of hand axes and flake tools, the ], ''Mode 2-type assemblages''. Both types of tool sets are attributed to '']'', the earliest and for a very long time the only human in Europe and more likely to be found in the southern part of the continent. However, the Acheulean fossil record also links to the emergence of '']'', particularly its specific ] tools and handaxes. The presence of ''Homo heidelbergensis'' is documented since 600,000 BC in numerous sites in Germany, Great Britain and northern France.<ref>{{Cite journal |title=Early Evidence of Acheulean Settlement in Northwestern Europe – La Noira Site, a 700,000 Year-Old Occupation in the Center of France |journal=PLOS ONE |volume=8 |issue=11 |pages=e75529 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0075529 |pmid=24278105 |year=2013 |last1=Moncel |first1=Marie-Hélène |last2=Despriée |first2=Jackie |last3=Voinchet |first3=Pierre |last4=Tissoux |first4=Hélène |last5=Moreno |first5=Davinia |last6=Bahain |first6=Jean-Jacques |last7=Courcimault |first7=Gilles |last8=Falguères |first8=Christophe |bibcode=2013PLoSO...875529M |pmc=3835824|doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| In the late phase of this epi-Paleolithic period, the Sauveterrean culture evolves into the so-called ] and influences strongly its southern neighbour, clearly replacing it in Mediterranean Spain and Portugal. | |||

| Although ] generally agree that ''Homo erectus'' and ''Homo heidelbergensis'' immigrated to Europe, debates remain about migration routes and the chronology.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://anthro.palomar.edu/homo/homo_2.htm |title=Early Human Evolution: Homo ergaster and erectus |publisher=palomar edu |access-date= December 31, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| The recession of the glaciers allows human colonization in Northern Europe for the first time. The ] culture, derived from the Sauveterre-Tardenois culture but with a strong personality, colonizes Denmark and the nearby regions, including parts of Britain. | |||

| The fact that '']'' is found only in a contiguous range in ] and the general acceptance of the ] hypothesis both suggest that the species has evolved locally. Again, consensus prevails on the matter, but widely debated are origin and evolution patterns.<ref>{{cite news |first=Clive |last=Cookson|url=http://www.ft.com/cms/s/2/c8260378-fc36-11e3-98b8-00144feab7de.html |title= Palaeontology: How Neanderthals evolved | newspaper= Financial Times |date=June 27, 2014 |access-date=October 28, 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Callaway|first1=Ewen|title='Pit of bones' catches Neanderthal evolution in the act|journal=Nature News|date=19 June 2014|doi=10.1038/nature.2014.15430|s2cid=88427585}}</ref><ref>{{cite magazine |url=http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/oldest-ancient-human-dna-details-dawn-of-neandertals/ |title= Oldest Ancient-Human DNA Details Dawn of Neandertals | magazine= Scientific American |date=March 14, 2016 |access-date=September 26, 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/species/homo-heidelbergensis |title= ''Homo heidelbergensis'' |quote= Comparison of Neanderthal and modern human DNA suggests that the two lineages diverged from a common ancestor, most likely ''Homo heidelbergensis'' | publisher= Smithsonian Institution |date= 2010-02-14|access-date=September 26, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| == Neolithic == | |||

| The Neanderthal fossil record ranges from Western Europe to the ] in Central Asia and the ] in the North to the ] in the South. Unlike its predecessors, they were biologically and culturally adapted to survival in cold environments and successfully extended their range to the glacial environments of Central Europe and the Russian plains. The great number and, in some cases, exceptional state of preservation of Neanderthal fossils and cultural ] enables researchers to provide a detailed and accurate data on behaviour and culture.<ref name="smithsonian">{{Cite news|url = http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/the-skeletons-of-shanidar-cave-7028477/?no-ist=&page=1|title = The Skeletons of Shanidar Cave|last = Edwards|first = Owen|date = March 2010|work = Smithsonian|access-date = 17 October 2014}}</ref><ref name=Neanderthal/> Neanderthals are associated with the ] (''Mode 3''), stone tools that first appeared approximately 160,000 years ago.<ref>{{cite book |editor1-last=Shaw |editor1-first=Ian |editor2-last=Jameson |editor2-first=Robert |title=A Dictionary of Archaeology |date=1999 |publisher= Blackwell |isbn=978-0-631-17423-3 |page=408 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8HKDtlPuM2oC&q=mousterian+40%2C000&pg=PA408|access-date=1 August 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/species/homo-neanderthalensis |title=Homo neanderthalensis |quote=...The Mousterian stone tool industry of Neanderthals is characterized by… |publisher= Smithsonian Institution |date=September 22, 2016 |access-date=September 26, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| ===Upper Paleolithic=== | |||

| European ] comes from the ], via ], the ] waterway and also through the ] in what regards to the East. There has been a long discussion between ''migrationists'' (who claim that the Asian peasants almost totally displaced the European native hunter-gatherers) and diffusionists (who claim that the process was slow enough to have occurred mostly through cultural transmission). Modern genetic studies seem to show that the truth is somewhere in the middle and that both processes took place, although the question is still open. | |||

| {{main|European early modern humans|Paleolithic Europe}} | |||

| ''Homo sapiens'' arrived in Europe around 46,000 and 43,000 years ago via the ] and entered the continent through the ], as the fossils at the sites of ] and ] suggest.<ref name=Wilford>{{cite news |first=John Noble |last=Wilford |title=Fossil Teeth Put Humans in Europe Earlier Than Thought |newspaper=New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/03/science/fossil-teeth-put-humans-in-europe-earlier-than-thought.html |date=2 Nov 2011 |access-date=2012-04-19 }}</ref> With an approximate age of 46,000 years,<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Fewlass |first1=Helen |last2=Talamo |first2=Sahra |last3=Wacker |first3=Lukas |last4=Kromer |first4=Bernd |last5=Tuna |first5=Thibaut |last6=Fagault |first6=Yoann |last7=Bard |first7=Edouard |last8=McPherron |first8=Shannon P. |last9=Aldeias |first9=Vera |last10=Maria |first10=Raquel |last11=Martisius |first11=Naomi L. |last12=Paskulin |first12=Lindsay |last13=Rezek |first13=Zeljko |last14=Sinet-Mathiot |first14=Virginie |last15=Sirakova |first15=Svoboda |last16=Smith |first16=Geoffrey M. |last17=Spasov |first17=Rosen |last18=Welker |first18=Frido |last19=Sirakov |first19=Nikolay |last20=Tsanova |first20=Tsenka |last21=Hublin |first21=Jean-Jacques |title=A 14C chronology for the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic transition at Bacho Kiro Cave, Bulgaria |journal=Nature Ecology & Evolution |date=11 May 2020 |volume=4 |issue=6 |pages=794–801 |doi=10.1038/s41559-020-1136-3 |pmid = 32393865 |hdl=11585/770560 |s2cid=218593433 |hdl-access=free }}</ref> the '']'' fossils found in Bacho Kiro cave consist of a pair of fragmented ] including at least one ]<ref>{{cite book|title=After Eden: The evolution of human domination |last=Sale |first=Kirkpatrick |publisher=Duke University Press |year=2006 |page= |url=https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780822339380 |url-access=registration |access-date=11 November 2011|isbn=0822339382 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Kuhn |first1=Steven L. |last2=Stiner |first2=Mary C. |last3=Reese |first3=David S. |last4=Güleç |first4=Erksin |title=Ornaments of the earliest Upper Paleolithic: New insights from the Levant |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences |date=19 June 2001 |volume=98 |issue=13 |pages=7641–7646 |doi=10.1073/pnas.121590798 |pmid=11390976 |pmc=34721 |bibcode=2001PNAS...98.7641K |doi-access=free }}</ref> This site yielded the oldest known ornaments in Europe, ] to over 43,000 years ago.<ref>{{cite book|title=European Prehistory: A Survey|last=Milisauskas|first=Sarunas|publisher=Springer|year=1974|isbn=978-1-4419-6633-9|access-date=June 8, 2012|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gcGSn0eVs2oC&q=bulgaria&pg=PA234|quote=One of the earliest dates for an Aurignacian assemblage is greater than 43,000 BP from Bacho Kiro cave in Bulgaria ...}}</ref> | |||

| The fossils' genetic structure indicates a recent Neanderthal ancestry and the discovery of a fragment of a skull in Israel in 2008 support the notion that humans interbred with Neanderthals in the Levant.{{citation needed|date=April 2020}} | |||

| '''· First Neolithic Culture in Thessalia:''' | |||

| Apparently related with the Anatolian culture of ], the Greek region of ] is the first place of Europe known to have developed agriculture, cattle-herding and pottery. These early stages are know as ] culture. | |||

| After the slow processes of the previous hundreds of thousands of years, a turbulent period of Neanderthal–''Homo sapiens'' coexistence demonstrated that cultural evolution had replaced biological evolution as the primary force of adaptation and change in human societies.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www2.fiu.edu/~grenierg/chapter5.htm |title=Chapter 5: Hunting & Gathering Societies |publisher=Florida International University |access-date= December 31, 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.u.arizona.edu/~mstiner/pdf/Kuhn_Stiner1998b.pdf |title=Creativity in human evolution and prehistory |publisher=Arizona University |access-date= December 31, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| '''· Ancient Neolithic:''' | |||

| The Thessalian neolithic culture soon evolves in the more coherent culture of ] (c. 6000 BCE), which is the origin of the main branches of Neolithic expansion in Europe. Practically all the BalkansPeninsula is colonized in the 6th millennium from there. That expansion, reaching the easternmost Tardenoisian outposts of the upper ] gives birth to the ] culture, a significant modification of the Balkan Neolithic that will be in the origin of one of the most important branches of European neolithic: the '''Danubian''' group of cultures. | |||

| Generally small and widely dispersed fossil sites suggest that Neanderthals lived in less numerous and more socially isolated groups than ''Homo sapiens''. Tools and ] are remarkably sophisticated from the outset, but they have a slow rate of variability, and general technological inertia is noticeable during the entire fossil period. Artifacts are of utilitarian nature, and symbolic behavioral traits are undocumented before the arrival of modern humans. The ] culture, introduced by modern humans, is characterized by cut ] or ] points, fine flint ] and bladelets struck from prepared ], rather than using crude ]. The oldest examples and subsequent widespread tradition of prehistoric art originate from the ].<ref name="MellarsArcheology">{{cite journal | last1 = Mellars | first1 = P. | year = 2006 | title = Archeology and the Dispersal of Modern Humans in Europe: Deconstructing the Aurignacian | journal = Evolutionary Anthropology | volume = 15 | issue = 5| pages = 167–182 | doi=10.1002/evan.20103| s2cid = 85316570 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://eol.org/pages/4454114/details |title=Homo neanderthalensis Brief Summary |publisher=EOL |access-date=September 26, 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | title =Symbolic or utilitarian? Juggling interpretations of Neanderthal behavior: new inferences from the study of engraved stone surfaces | pmid=25020018 | doi=10.4436/JASS.92007 | volume=92 | issue=92 | journal=J Anthropol Sci | pages=233–55 | last1 = Peresani | first1 = M | last2 = Dallatorre | first2 = S | last3 = Astuti | first3 = P | last4 = Dal Colle | first4 = M | last5 = Ziggiotti | first5 = S | last6 = Peretto | first6 = C| year=2014| doi-broken-date=1 November 2024 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=European Prehistory: A Survey|last=Milisauskas|first=Sarunas|publisher=Springer|year=2011|page=74|isbn=978-1-4419-6633-9|access-date=8 June 2012|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gcGSn0eVs2oC&pg=PA234 |quote=One of the earliest dates for an Aurignacian assemblage is greater than 43,000 BC from Bacho Kiro cave in Bulgaria ...}}</ref> | |||

| In parallel, the coasts of the ] and southern ] witness the expansion of another Neolithic current of less clear origins. Settling initially in ], the bearers of the ] culture may have come from Thessalia (some of the pre-Sesklo settlements show related traits) or even from Lebanon (Byblos). They are sailors, fishermen and sheep and goat herders, and the archaeological findings show that they mixed with natives in most places. | |||

| After more than 100,000 years of uniformity, around 45,000 years ago, the Neanderthal fossil record changed abruptly. The Mousterian had quickly become more versatile and was named the ] culture, which signifies the diffusion of Aurignacian elements into Neanderthal culture. Although debated, the fact proved that Neanderthals had, to some extent, adopted the culture of modern ''Homo sapiens''.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://archaeology.about.com/od/upperpaleolithic/qt/Chatelperronian-Guide.htm |title=Chatelperronian Transition to Upper Paleolithic |publisher=About.com |access-date= December 31, 2016}}</ref> However, the Neanderthal fossil record completely vanished after 40,000 years BC. Whether Neanderthals were also successful in diffusing their genetic heritage into Europe's future population or they simply went extinct and, if so, what caused the extinction cannot conclusively be answered. | |||

| Other early neolithic cultures can be found in ] and Southern ], where the epi-Gravettian locals assimilated cultural influxes from beyond the Caucasus (culture of ] and related) and in ] (Spain), where the rare Neolithic of ] appears without known origins very early (c. 5800 BCE). | |||

| ] cave painting, ], 15,000 BC]] | |||

| ] | |||

| Around 32,000 years ago, the ] appeared in the ] (southern ]).<ref name=orig>{{cite journal | title = The Oldest Anatomically Modern Humans from Far Southeast Europe: Direct Dating, Culture and Behavior | first1 = Sandrine | last1= Prat | first2= Stéphane C. | last2= Péan | first3= Laurent | last3= Crépin | first4 =Dorothée G. |last4= Drucker | first5 =Simon J. | last5= Puaud | first6 =Hélène | last6=Valladas | first7= Martina |last7 =Lázničková-Galetová | first8 =Johannes | last8 =van der Plicht | first9= Alexander | last9= Yanevich | journal = PLOS ONE |date = 17 June 2011 | volume = 6 | issue = 6 | pages = e20834 | publisher = plosone | doi = 10.1371/journal.pone.0020834 | pmid = 21698105 | pmc = 3117838 | bibcode = 2011PLoSO...620834P | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref name=bbc>{{cite news | url = https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-13846262 | title = Early human fossils unearthed in Ukraine | first = Jennifer | last = Carpenter |date = 20 June 2011 | publisher = BBC | access-date = 21 June 2011}}</ref> By 24,000 BC, the ] and Gravettian cultures were present in Southwestern Europe. Gravettian technology and culture have been theorised to have come with migrations of people from the Middle East, Anatolia and the Balkans, and might be linked with the transitional cultures mentioned earlier since their techniques have some similarities and are both very different from Aurignacian ones, but this issue is very obscure. The Gravettian also appeared in the ] and ] Mountains but soon disappeared from southwestern Europe, with the notable exception of the Mediterranean coasts of Iberia. | |||

| '''· Middle Neolithic:''' | |||

| This phase, starting in 5000 BCE is marked by the consolidation of the Neolithic expansion towards western and northern Europe, but also by the irruption of a new culture that, probably through violence, occupies most of the Balkans, substituting or rather subjugating the first Neolithic settlers. | |||

| The Solutrean culture, extended from northern Spain to southeastern France, includes not only a ] but also the first significant development of cave painting and the use of the needle and possibly that of the bow and arrow. The more widespread Gravettian culture is no less advanced, at least in artistic terms: sculpture (mainly ''venuses'') is the most outstanding form of creative expression of such peoples. | |||

| This is the culture of ] (Thessalia) and the related ones of ]-] (Serbia and Macedonia) and ] III-] (Bulgaria and nearby areas), this last one more hybrid than the other two. | |||

| Around 19,000 BC, Europe witnesses the appearance of a new culture, known as ], possibly rooted in the old Aurignacian one, which soon superseded the Solutrean area and also the Gravettian of Central Europe. However, in Mediterranean Iberia, Italy, the Balkans and Anatolia, ] cultures continued to evolve locally. | |||

| Meanwhile, the tiny proto-Linear Pottery culture has given birth to two very dynamic branches: the Western and Eastern ]s. The latter is basically an extension of the Balkan neolithic, but the more original western branch expands quickly, assimilating what today is Germany, the Czech Republic, Poland and even large parts of western Ukraine, Moldavia, the lowlands of Romania, and regions of France, Belgium and the Netherlands. This was all achieved in less than one thousand years. With expansion comes diversification and a number of local Danubian cultures start forming at the end of the 5th millennium. | |||

| With the Magdalenian culture, the Paleolithic development in Europe reaches its peak and this is reflected in art, owing to previous traditions of paintings and sculpture. | |||

| In the Mediterranean, the Cardium Pottery fishermen show no less dynamism and colonize/assimilate all of Italy and the the Mediterranean regions of France and Spain. | |||

| Around 12,500 BC, the ] Glacial Age ended. Slowly, through the following millennia, temperatures and sea levels rose, changing the environment of prehistoric people. Ireland and Great Britain became islands, and Scandinavia became separated from the main part of the European Peninsula. (They had all once been connected by a now-submerged region of the continental shelf known as ].) Nevertheless, the Magdalenian culture persisted until 10,000 BC, when it quickly evolved into two ''microlith'' cultures: ], in Spain and southern France, and ], in northern France and Central Europe. Despite some differences, both cultures shared several traits: the creation of very small stone tools called ]s and the scarcity of figurative art, which seems to have vanished almost completely, which was replaced by abstract decoration of tools.<ref>{{Cite web | url=http://www.beloit.edu/~museum/logan/paleoexhibit/masdazil.htm#thumbnails | title=Mas d'Azil|website = Logan Museum|publisher = Beloit College| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20010430150334/http://www.beloit.edu/~museum/logan/paleoexhibit/masdazil.htm |archive-date = 30 April 2001}}</ref> | |||

| Even in the Atlantic, some groups among the native hunter-gatherers start slowly incorporating the new technologies. Among those, the most noticeable regions seem to be the southwest of Iberia, influenced by the Mediterranean but specially by the Andalusian neolithic, which soon developes the first ] burials (]s) and the area around Denmark (culture of ]), influenced by the Danubian complex. | |||

| In the late phase of the epi-Paleolithic period, the Sauveterrean culture evolved into the so-called ] and strongly influenced its southern neighbour, clearly replacing it in Mediterranean Spain and Portugal. The recession of the glaciers allowed human colonisation in Northern Europe for the first time. The ] culture, derived from the Sauveterre-Tardenois culture but with a strong personality, colonised Denmark and the nearby regions, including parts of Britain. | |||

| '''· Late Neolithic:''' | |||

| This period occupies the first half of the 4th century BCE and is rather quiet. The tendencies of the previous period consolidate, so we have a fully formed Neolithic Europe with five main cultural regions: | |||

| <gallery> | |||

| ] | |||

| File:Floete Schwanenknochen Geissenkloesterle Blaubeuren.jpg|], ], ] cave, 43,000 BC | |||

| File:Adorant, Geisenklösterle, Blaubeuren-Weiler, Alb-Donau-Kreis, Aurignacian culture, 35,000 to 45,000 years old, ivory - Landesmuseum Württemberg - Stuttgart, Germany - DSC02709.jpg|], Aurignacian, 42,000 to 40,000 BC | |||

| File:Loewenmensch1.jpg|], Aurignacian, c. 41,000 to 35,000 BC | |||

| File:Chauvet´s cave horses.jpg|] cave paintings, ], c. 30,000 BC | |||

| File:Vestonicka venuse edit.jpg|], ], c. 29,000 BC | |||

| File:Venus-de-Laussel-vue-generale-noir.jpg|], Gravettian, c. 23,000 BC | |||

| File:Venus of Brassempouy.jpg|], c. 23,000 BC | |||

| File:F07 0054.Ma.JPG|Antler carving, Magdalenian, 15,000 BC | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ===Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age)=== | |||

| · Danubian cultures: from northern France to Western Ukraine. Now split into several local cultures, the most relevant ones being: the Romanian branch (culture of ]) that expands into Bulgaria, the ] that is preeminent in the west, and the culture of ] of Austria and western Hungary, which will have a major role in the upcoming periods. | |||

| {{main|Mesolithic Europe}} | |||

| {{further|Balkan Mesolithic|British Mesolithic|Irish Mesolithic|Azilian|Fosna–Hensbacka culture|Kunda culture}} | |||

| ], France, ] culture, c. 10,000 BC.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www3.astronomicalheritage.net/index.php/show-entity?identity=83&idsubentity=1|title=The Thaïs Bone, France|website=UNESCO Portal to the Heritage of Astronomy|quote=The engraving on the Thaïs bone is a non-decorative notational system of considerable complexity. The cumulative nature of the markings together with their numerical arrangement and various other characteristics strongly suggest that the notational sequence on the main face represents a non-arithmetical record of day-by-day lunar and solar observations undertaken over a time period of as much as 3½ years. The markings appear to record the changing appearance of the moon, and in particular its crescent phases and times of invisibility, and the shape of the overall pattern suggests that the sequence was kept in step with the seasons by observations of the solstices. The latter implies that people in the Azilian period were not only aware of the changing appearance of the moon but also of the changing position of the sun, and capable of synchronizing the two. The markings on the Thaïs bone represent the most complex and elaborate time-factored sequence currently known within the corpus of Palaeolithic mobile art. The artefact demonstrates the existence, within Upper Palaeolithic (Azilian) cultures c. 12,000 years ago, of a system of time reckoning based upon observations of the phase cycle of the moon, with the inclusion of a seasonal time factor provided by observations of the solar solstices.}}</ref>|174x174px]] | |||

| A transition period in the development of human technology between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic, the ] began around 15,000 years ago. In Western Europe, the Early Mesolithic, or ], began about 14,000 years ago, in the ] of northern Spain and southern France. In other parts of Europe, the Mesolithic began by 11,500 years ago (the beginning ]) and ended with the ] of farming, which, depending on the region, occurred 8,500 to 5,500 years ago. | |||

| · Mediterranean cultures: from the Adriatic to eastern Spain, including Italy and large portions of France and Switzerland. These are also diversified into several groups. | |||

| In areas with limited glacial impact, the term "Epipaleolithic" is sometimes preferred for the period. Regions that experienced greater environmental effects as the Last Glacial Period ended had a much more apparent Mesolithic era that lasted millennia. In Northern Europe, societies were able to live well on rich food supplies from the marshlands, which had been created by the warmer climate. Such conditions produced distinctive human behaviours that are preserved in the material record, such as the Maglemosian and Azilian cultures. Such conditions delayed the coming of the Neolithic to as late as 5,500 years ago in Northern Europe. | |||

| · The area of Dimini-Vinca: Thessalia, Macedonia and Serbia, but extending its influence also to parts of the mid-Danubian basin (Tisza, ])and southern Italy. | |||

| As what ] termed the "Neolithic Package" (including agriculture, herding, polished stone axes, timber longhouses and pottery) spread into Europe, the Mesolithic way of life was marginalised and eventually disappeared.<ref>Childe 1925</ref> Controversy over the means of that dispersal is discussed below in the ''Neolithic'' section. A "]" can be distinguished between 7,200 and 5,850 years ago and ranged from Southern to Northern Europe. | |||

| · Eastern Europe: basically central and eastern Ukraine and parts of southern Russia and Byelorussia (culture of Dniepr-Don). Apparently this people were the ones who first domesticated horses (though some Paleolithic evidence could disprove it). | |||

| <gallery> | |||

| · Atlantic Europe: a mosaic of local cultures, some of them still pre-Neolithic, from Portugal to southern Sweden. Since around 3800 BCE the western regions of France incorporate also the Megalithic style of burial. | |||

| File:Laténium-dame-Monruz.jpg|], Switzerland, c. 9000 BC | |||

| File:Shigir idol.jpg|], Russia, c. 10,000 BC | |||

| File:064 Pintures de la cova dels Moros, exposició al Museu de Gavà.JPG|], Spain | |||

| File:Magura - drawings.jpg|] drawings, Bulgaria, c. 8,000- 6,000 BC | |||

| File:Boomstamkano van Pesse, Drents Museum, 1955-VIII-2.jpg|], Netherlands, c. 8000 BC | |||

| File:Huittisten hirvenpää.jpg|], Finland, c. 6500 BC | |||

| File:Lepenski Vir, muzej 13.jpg|] sculpture, Serbia, c. 7000 BC | |||

| File:Animal figurine carved from amber, Denmark.jpg|] animal figurine, ], c. 12,000 BC | |||

| File:Star Carr pendant 1.png|], Britain, c. 9000 BC | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ==Neolithic (New Stone Age)== | |||

| There are also a few independent areas: Andalusia, southern Greece and the western coasts of the Black Sea (culture of ]). | |||

| {{Main|Neolithic Europe}} | |||

| {{further|Old Europe (archaeology)}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The European ] is assumed to have arrived from the Near East via ], the ] and the ]. There has been a long discussion between ''migrationists'', who claim that the Near Eastern farmers almost totally displaced the European native hunter-gatherers, and ''diffusionists'', who claim that the process was slow enough to have occurred mostly through ]. A relationship has been suggested between the spread of agriculture and the diffusion of ], with several models of migrations trying to establish a relationship, like the ], which sets the origin of Indo-European agricultural terminology in Anatolia.<ref>The supposed autochthony of Hittites, the Indo-Hittite hypothesis and the migration of agricultural "Indo-European" societies were intrinsically linked by Colin Renfrew 2001</ref> | |||

| == Chalcolithic == | |||

| ===Early Neolithic=== | |||

| Also known as '''Copper Age''', European ] is a time of changes and confusion. The most relevant fact is the infiltration and invasion of large parts of the territory by people originating from Central Asia, considered by mainstream scholars to be the original ], although there are again several theories in dispute. Other phenomena are the expansion of Megalithism and the appearance of the first significant economic stratification and, related to this, the first known monarchies in the Balkan region. | |||

| Apparently related with the Anatolian culture of ], the Greek region of ] was the first place in Europe known to have acquired agriculture, cattle-herding and pottery. The early stages are known as ] culture. The Thessalian Neolithic culture soon evolved into the more coherent ] (6000 BC), which was the origin of the main branches of Neolithic expansion in Europe. The ] on the territory of modern day Bulgaria, was another early ] (Karanovo I-III ca. 62nd to 55th centuries BC) which was part of the ] and it is considered the largest and most important of the Azmak River Valley agrarian settlements.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|title=Native Peoples of the World: An Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures and Contemporary Issues|last=Danver|first=Steven L.|date=2015|publisher=Routledge|isbn=9780765682222|location=Oxon|pages=271}}</ref> The Karanovo I is considered a continuation of Near Eastern settlement type.<ref>{{Cite book|last1=Whittle|first1=Alasdair|title=Living Well Together? Settlement and Materiality in the Neolithic of South-East and Central Europe|last2=Hofmann|first2=Daniela|last3=Bailey|first3=Douglass W.|publisher=Oxbow Books|year=2008|isbn=978-1-78297-481-9|language=en}}</ref> The ] is dating to the period between ''c.'' 6200 and 4500 ].<ref name="Istorijski atlas">Istorijski atlas, Intersistem Kartografija, Beograd, 2010, page 11.</ref>{{sfn|Chapman|2000|p=237}} It originates in the spread of the ] of peoples and technological innovations including farming and ceramics from ]. The Starčevo culture marks its spread to the inland Balkan peninsula as the ] culture did along the Adriatic coastline. It forms part of the wider ]. Practically all of the ] was colonized in the 6th millennium from there. The expansion, reaching the easternmost Tardenoisian outposts of the upper ], gave birth to the ] culture, a significant modification of the Balkan Neolithic that was the origin of one of the most important branches of European Neolithic: the ] group of cultures. In parallel, the coasts of the ] and of southern Italy witnessed the expansion of another Neolithic current with less clear origins. Settling initially in ], the bearers of the ] culture may have come from Thessaly (some of the pre-Sesklo settlements show related traits) or even from Lebanon (Byblos). They were sailors, fishermen and sheep and goat herders, and the archaeological findings show that they mixed with natives in most places. Other early Neolithic cultures can be found in ] and Southern Russia, where the epi-Gravettian locals assimilated cultural influxes from beyond the Caucasus (e.g. the ] and related cultures) and in ] (Spain), where the rare Neolithic of ] appeared without known origins very early (c. 7800 BC). | |||

| ===Middle Neolithic=== | |||

| The economy of the Chalcolithic, even in the regions where copper is not used yet, is no longer that of peasant communities and tribes: now some materials are produced in specific locations and distributed to wide regions. ] of metal and stone is particularly developed in some areas, along with the processing of those materials into valuable goods. | |||

| {{Main|Middle Neolithic}} | |||

| This phase, starting 7000 years ago was marked by the consolidation of the Neolithic expansion towards western and northern Europe but also by the rise of new cultures in the Balkans, notably the ] (Thessaly) and related ] (Serbia and Romania) and ] cultures (Bulgaria and nearby areas). Meanwhile, the Proto-Linear Pottery culture gave birth to two very dynamic branches: the Western and Eastern ]s. The western branch expanded quickly, assimilating Germany, the Czech Republic, Poland and even large parts of western Ukraine, historical ], the lowlands of Romania, and regions of France, Belgium and the Netherlands, all in less than 1000 years. With this expansion came diversification and a number of local Danubian cultures started forming at the end of the 5th millennium. In the Mediterranean, the Cardium pottery fishermen showed no less dynamism and colonised or assimilated all of Italy and the Mediterranean regions of France and Spain. Even in the Atlantic, some groups among the native hunter-gatherers started the slow incorporation of the new technologies. Among them, the most noticeable regions seem to be southwestern Iberia, which was influenced by the Mediterranean but especially by the Andalusian Neolithic, which soon developed the first ] burials (]s), and the area around Denmark (] culture), influenced by the Danubian complex. | |||

| ===Late Neolithic=== | |||

| '''· Ancient Chalcolithic:''' | |||

| This period occupied the first half of the 6th millennium BC. The tendencies of the previous period consolidated and so there was a fully-formed Neolithic Europe, with five main cultural regions: | |||

| From c. 3500 to 3000 BCE. copper starts to be used in the Balkans, and Eastern and Central Europe. However, the key factor could be the use of horses, which would increase mobility. | |||

| # ]: from northern France to western Ukraine. Now split into several local cultures, the most relevant being the (]), the ] that was pre-eminent in the west, and the ] of Austria and western Hungary, which would have a major role in later periods. | |||

| ## The area of Dimini-Vinca: Thessaly, Macedonia and Serbia but extending its influence to parts of the mid-Danubian basin (Tisza, ]) and southern Italy. | |||

| # Mediterranean cultures: from the Adriatic to eastern Spain, including Italy and large portions of France and Switzerland. They were also diversified into several groups. | |||

| # Eastern Europe: basically central and eastern ] and parts of southern Russia and ] (Dniepr-Don culture). This area has the earliest evidence for domesticated horses. | |||

| # Atlantic Europe: a mosaic of local cultures, some of them still pre-Neolithic, from Portugal to southern Sweden. In around 5800 BC, western France began to incorporate the Megalithic style of burial. | |||

| <gallery> | |||

| From c. 3500 onwards, Eastern Europe is apparently infiltrated by people originating from beyond the Volga (]), creating a plural complex known as ], that substitutes the previous Dniepr-Don culture, pushing the natives to migrate in a NW direction to the Baltic and Denmark, where they mix with natives (] A and C). Soon this migration is followed by that of the (apparently) Indo-European invaders, who settle in eastern Germany and Poland (culture of ]). Near the end of the period, another branch will leave many traces in the lower Danube area (culture of ]), in what seems to be another invasion. | |||

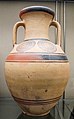

| File:Ancient Greece Neolithic Pottery - 28421665976.jpg|], Greece, c. 6000-5300 BC | |||

| File:NeolithicVessel B&W 1.jpg|], Bulgaria, 6th mill. BC | |||

| File:Ovcharovo tell, miniature culture scene, Bulgaria, 6th millennium BC.jpg|], Bulgaria, 5th mill. BC | |||

| File:Cultura di vinca, idolo, serbia 4500-3500 ac ca. 01.jpg|] figurine, Serbia, c. 5000 BC | |||

| File:LBK house 1.jpg|], ], 5000 BC | |||

| File:Goseck Circle 1.jpg|], Germany, 4900 BC | |||

| File:Dimini 3.jpg|], walled acropolis, Greece, c. 4800 BC | |||

| File:Gavrinis 2.jpg|] megalithic tomb, ], 4000 BC | |||

| File:Er Grah, Locmariaquer Megaliths.jpg|], ], 4500 BC | |||

| File:Monte d'Accoddi, reconstruction 1.jpg|], Sardinia, c. 3500-3000 BC.<ref>{{cite journal|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272651018|journal=Documenta Praehistorica|volume=38|title=Monte d'Accoddi and the end of the Neolithic in Sardinia (Italy)|last=Grazia Melis|first=Maria|date=2011|doi=10.4312/dp.38.16|pages=207–219}}</ref> | |||

| File:Dolmen de Menga. Interior 2.jpg|], ], c. 3700 BC | |||

| File:Irelands history.jpg|], ], 3200 BC | |||

| File:Durankulak-Golemija ostrov-Hamangia IV vessels.jpg|], ] | |||

| File:Tisza1.jpg|], ], 5300 BC<ref>{{cite web|url=https://isaw.nyu.edu/exhibitions/ritual-and-memory/objects/altar-szeged|title=Ritual and Memory: Neolithic Era and Copper Age|website=Institute for the Study of the Ancient World|date=2022}}</ref> | |||

| File:R20S09-90 (52319225595).jpg|], Sardinia, 4500 BC | |||

| File:Okoliste. Neolithic settlement 5200 BC. Bosnia and Herzegovina (cropped).jpg|], Bosnia and Herzegovina, c. 5000 BC | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ==Chalcolithic (Copper Age)== | |||

| Meanwhile the Danubian culture of ] absorbs its northern neighbours of the Czech Replublic and Poland for some centuries, only to recede in the second half of the period. In Bulgaria and Vallachia, the culture of ] evolves into a monarchy with a clearly royal cemetery near the coast of the Black Sea. This model seems to have been copied later in the Tiszan region with the culture of ]. Labor specialization, economic stratification and possibly the risk of invasion may have been the reasons behind this development. The influx of early ] (Troy I) is clear in both the expansion of metallurgy and social organization. | |||

| {{Main|Chalcolithic Europe}} | |||

| {{further|Old Europe (archaeology)}} | |||

| ] elite burial, Bulgaria, 4500 BC|203x203px]] | |||

| Also known as "Copper Age", the European ] was a time of significant changes, the first of which was the invention of ]. This is first attested in the ] in the 6th millennium BC. The Balkans became a major centre for copper extraction and metallurgical production in the 5th millennium BC. Copper artefacts were traded across the region, eventually reaching eastwards across the steppes of eastern Europe as far as the ]. The 5th millennium BC also saw the appearance of economic stratification and the rise of ruling elites in the Balkan region, most notably in the ] (c. 4500 BC) in Bulgaria, which developed the first known gold metallurgy in the world. | |||

| The economy of the Chalcolithic was no longer that of peasant communities and tribes, since some materials began to be produced in specific locations and distributed to wide regions. ] of metal and stone was particularly developed in some areas, along with the processing of those materials into valuable goods.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://journals.uair.arizona.edu/index.php/radiocarbon/article/view/3936 | title= The Copper Age in northern Italy | publisher=University of Arizona Libraries | access-date=December 29, 2017}}</ref> | |||

| In the western Danubian region (the Rhine and Seine basins) the culture of ] displaces its predecessor, Rössen. Meanwhile in the Mediterranean basin, several cultures (most notably ] in SE France and ] in northern Italy) converge into a functional union, of which the most significant characteristic is the distribution network of honey-coloured ]. Despite this unity, the signs of conflicts are clear, as many skeletons show violent injuries. This is the time and area where ], the famous man found in the Alps, lived. | |||

| '''Early Chalcolithic, 5500-4000 BC''' | |||

| Another significant development of this period is that the Megalithic phenomenon starts spreading to most places of the Atlantic region, bringing agriculture with it to some underdeveloped regions there. | |||

| From 5500 BC onwards, Eastern Europe was apparently infiltrated by people originating from beyond the Volga, creating a plural complex known as ], which substituted the previous ] culture in Ukraine, pushing the natives to migrate northwest to the Baltic and to Denmark, where they mixed with the natives (] A and C). The emergence of the Sredny Stog culture may be correlated with the expansion of Indo-European languages, according to the ]. Near the end of the period, around 4000 BC, another westward migration of supposed Indo-European speakers left many traces in the lower Danube area (culture of ] I) in what seems to have been an invasion.<ref>{{cite thesis |url=https://www.academia.edu/4831344 |title=Re-Examining Late Chalcolithic Cultural Collapse in South-East Europe |publisher=University of Arkansas |type=MA Thesis |access-date= January 1, 2017|last1=Smith |first1=Harvey B.}}</ref> | |||

| '''· Middle Chalcolithic:''' | |||

| ] ("The Saltworks"), a prehistoric town located in present-day ], is believed by archaeologists to be the oldest town in ] - a fortified stone settlement - citadelle, inner and outer city with pottery production site and the site of a ] production facility approximately six millennia ago;<ref name=Maugh>{{cite news |title=Bulgarians find oldest European town, a salt production center |first=Thomas H. |last=Maugh II |url=https://www.latimes.com/science/la-xpm-2012-nov-01-la-sci-sn-oldest-european-town-20121101-story.html |newspaper=] |date=1 November 2012 |accessdate=1 November 2012}}</ref> it flourished ca 4700–4200 BC.<ref></ref><ref name=Squires>{{cite news |title=Archaeologists find Europe's most prehistoric town |first=Nick |last=Squires |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/bulgaria/9646541/Bulgaria-archaeologists-find-Europes-most-prehistoric-town-Provadia-Solnitsata.html |newspaper=] |date=31 October 2012 |accessdate=1 November 2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://naim.bg/contentFiles/ARH_2012_1_res1.pdf |title=Salt, early complex society, urbanization: Provadia-Solnitsata (5500-4200 BC) (Abstract) |first=Vassil |last=Nikolov |publisher=] |accessdate=1 November 2012}}</ref> | |||

| This period extends along the first half of the ]E. | |||

| Meanwhile, the Danubian ] absorbed its northern neighbours in the Czech Republic and Poland for some centuries, only to recede in the second half of the period. The hierarchical model of the Varna culture seems to have been replicated later in the Tiszan region with the ]. Labour specialisation, economic stratification and possibly the risk of invasion may have been the reasons behind this development. | |||

| Most significant is the reorganization of the Danubians in the powerful ], that extends more or less to what would be the Austro-Hungarian empire in recent times. The rest of the Balkans is profoundly restructured after the invasions of the previous period but, with the exception of the culture of ] in a mountainous region, none of them show any ''eastern'' (or presumably Indo-European) traits. The new culture of ], in Bulgaria, shows the first traits of pseudo-bronze (an alloy of copper with ]). So does the first significant Aegean group: the Cycladic culture after 2800 BCE. | |||

| In the western Danubian region (the Rhine and Seine basins), the ] displaced its predecessor, the ]. Meanwhile, in the Mediterranean basin, several cultures (most notably the ] in southeastern France and the ] in northern Italy) converged into a functional union of which the most significant characteristic was the distribution network of honey-coloured ]. Despite the unity, the signs of conflicts are clear, as many skeletons show violent injuries. This was the time and area of ], the famous man found in the Alps. | |||

| In the North, for some time the supposedly Indo-European groups seem to recede temporarily, suffering a strong cultural ''danubization''. | |||

| ;Middle Chalcolithic, 4000-3000 BC | |||

| In the East, the peoples of beyond the Volga (]), surely eastern Indo-Europeans, ancestors of ], ] and ], take over southern Russia and the Ukraine. | |||

| ] figurine, Romania, 4000 BC|207x207px]] | |||

| This period extends through the first half of the 4th millennium BC. During this period the ] culture in Ukraine experienced a massive expansion, building the largest settlements in the world at the time, described as the first cities in the world by some scholars. The earliest known evidence for wheeled vehicles, in the form of wheeled models, also comes from Cucuteni-Trypillia sites, dated to c. 3900 BC. | |||

| In the West the only sign of unity comes from the Megalithic super-culture, which extends now from southern Sweden to southern Spain, including large parts of southern Germany as well. But the Mediterranean and Danubian groupings of the previous period appear fragmented into many smaller pieces, some of them apparently backward in technological matters. | |||

| In the Danubian region the powerful ] emerged circa 3500 BC, extending more or less across the region of ]. The rest of the Balkans was profoundly restructured after the invasions of the previous period, with the ] in the central Balkans showing pronounced eastern (or presumably Indo-European) traits. The new ] in Bulgaria (3300 BC), shows the first evidence of pseudo-bronze (or ]al bronze), as does the Baden culture and the ] (in the Aegean) after 2800 BC.<ref name="cultural" /> | |||

| From c. 2800 BCE, the Danubian culture of ] pushes directly or indirectly southwards, destroying most of the rich Megalithic culture of western France. | |||

| In Eastern Europe, the ] took over southern Russia and Ukraine. In ], the only sign of unity came from the Megalithic ], which extended from southern Sweden to southern Spain, including large parts of southern Germany as well. However, the Mediterranean and Danubian groupings of the previous period appear to have fragmented into many smaller pieces, some of them apparently backward in technological matters. From 2800 BC, the Danubian ] pushed directly or indirectly southwards and destroyed most of the rich Megalithic culture of western France. After 2600 BC, several phenomena prefigured the changes of the upcoming period:<ref>{{cite web |url=http://alterling.ucoz.de/index/ethnicity_of_the_neolithic_and_eneolithic_cultures_of_eastern_europe/0-37 |title=Alternative Linguiatics – Ethnicity of the Neolithic and Chalcolithic cultures of Eastern Europe |publisher=Alterling ucoz de |access-date= January 1, 2017}}</ref> | |||

| After c. 2600 several phenomena will prefigure the changes of the upcoming period: | |||

| Large towns with stone walls appeared in two different areas of the Iberian Peninsula: one in the Portuguese region of ] (culture of ]), strongly embedded in the Atlantic Megalithic culture; the other near ] (southeastern Spain), centred around the large town of ], of Mediterranean character, probably affected by eastern cultural influxes ('']''). Despite the many differences, both civilisations seem to have had friendly contact and to productive exchanges. In the area of ] (], France), a new unexpected culture of ] appears: the ] culture soon takes control of western and even northern France and Belgium. In Poland and nearby regions, the putative Indo-Europeans reorganised and reconsolidated with the culture of the Globular Amphoras. Nevertheless, the influence of many centuries in direct contact with the still-powerful Danubian peoples had greatly modified their culture.<ref name = cultural>{{cite book |last1=Haarmann |first1=Harald |title=Early civilization and literacy in Europe : an inquiry into cultural continuity in the Mediterranean world |date=1996 |publisher=Mouton de Gruyter |location=Berlin |isbn= 978-3110146516 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vXFW36L1hu4C&q=Chalcolithic+Europe&pg=PA49}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |jstor=280864 |title=Neolithic, Chalcolithic, and Early Bronze in West Mediterranean Europe |journal=American Antiquity |volume=51 |issue=4 |pages=763 |doi=10.2307/280864 |year=2017 |last1=Wells |first1=Peter S. |last2=Geddes |first2=David S. |s2cid=163672997 }}</ref> | |||

| <gallery> | |||

| · In the area of ] (], France), a new unexpected culture of ] appears: it is the culture of ], that soon takes control of western and even northern France and Belgium. | |||

| File:Grave offerings.jpg|], Bulgaria, 4500 BC | |||

| File:Neolithic Pottery (28650540752).jpg|] pottery, Ukraine | |||

| File:Maidanetske 3D model.jpg|], Ukraine, c. 3800 BC | |||

| File:Bodrogkeresztur gold.jpg|], Hungary, 4000-3600 BC | |||

| File:Malta - Qrendi - Hagar Qim and Mnajdra Archaeological Park - Hagar Qim 08 ies.jpg|] temple, ], 3600-3200 BC | |||

| File:The Sleeping Lady, 2009.jpg|] figurine, Malta, 3300–3000 BC | |||

| File:Ancient Greece Neolithic Gold Ornaments (28421389976).jpg|], Greece, c. 4000 BC | |||

| File:Baden wagon 1.jpg|], Hungary, 3300 BC | |||

| File:Skarpsallingkarret DO-9665 original.jpg|], Denmark, 3200 BC | |||

| File:Wheel 1a.jpg|], ], 3150 BC | |||

| File:Los Millares recreacion cuadro.jpg|], Spain, c. 3100 BC | |||

| File:Керносовский идол.png|] stone stele, Ukraine, c. 2600 BC | |||

| File:Campaniforme M.A.N. 04.JPG|] burial, Spain, c. 2500 BC | |||

| File:Stonehenge - panoramio - dtobias (1).jpg|], ], 2500 BC | |||

| File:Silbury 1.jpg|], Britain, c. 2400 BC | |||

| File:Blessington 1c.jpg|], Ireland, c. 2400 BC | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ==Bronze Age== | |||

| · In Poland and nearby regions, the (seemingly) Indo-Europeans reorganize and consolidate again with the culture of the Globular Amphoras. Nevertheless, the influence of many centuries in direct contact with the still-powerful Danubian peoples has greatly modified their culture. | |||

| {{Main|Bronze Age Europe}} | |||

| ] marble figurine, 2700 BC|219x219px]] | |||

| Use of Bronze begins in the ] around 3200 BC. From 2500 BC the new ], whose origins were obscure but were also Indo-Europeans, displaced the Yamna peoples in the regions north and east of the Black Sea, confining them to their original area east of the Volga. Around 2400 BC, the ] replaced their predecessors and expanded to Danubian and Nordic areas of western Germany. One related branch invaded Denmark and southern Sweden (]), and the mid-Danubian basin, though showing more continuity, had clear traits of new Indo-European elites (]). Simultaneously, in the West, the Artenac peoples reached Belgium. With the partial exception of Vučedol, the Danubian cultures, which had been so buoyant just a few centuries ago, were wiped off the map of Europe. The rest of the period was the story of a mysterious phenomenon: the ], which seemed to be of a mercantile character and to have preferred being buried according to a very specific, almost invariable, ritual. Nevertheless, out of their original area of western Central Europe, they appeared only within local cultures and so they never invaded and assimilated but went to live among those peoples and kept their way of life, which is why they are believed to be merchants. | |||

| The rest of Europe remained mostly unchanged and apparently peaceful. In 2300 BC, the first Beaker Pottery appeared in Bohemia and expanded in many directions but particularly westward, along the Rhone and the seas, reaching the culture of Vila Nova (Portugal) and Catalonia (Spain) as their limits. Simultaneously but unrelatedly, in 2200 BC in the Aegean region, the ] culture decayed and was substituted by the new palatine phase of the ] culture of ]. | |||

| '''· Late Chalcolithic:''' | |||

| This period extends from c. 2500 BCE to c. 1800 or 1700 BCE (depending on the region). The dates are general for the whole of Europe, and the Aegean area is already fully in the Bronze Age. | |||

| The second phase of Beaker Pottery, from 2100 BC onwards, is marked by the displacement of the centre of the phenomenon to Portugal, within the culture of Vila Nova. The new centre's influence reached to all of southern and western France but was absent in southern and western Iberia, with the notable exception of Los Millares. After 1900 BC, the centre of the Beaker Pottery returned to Bohemia, and in Iberia, a decentralisation of the phenomenon occurred, with centres in Portugal but also in Los Millares and ]. | |||

| C. 2500 BCE the new ] (proto-Cymmerians), whose origins are obscure but who are also Indo-Europeans, displaces the peoples of the Jamnaja Kultura in the regions north and east of the Black Sea, confining them to their original area east of the Volga. Some of these infiltrate Poland and may have played a significant but unclear role in the transformation of the culture of the ] into the new culture of ]. | |||

| ], ], 1800 BC|188x188px]] | |||

| Whatever happened, the fact is that c. 2400 BCE this people of the Corded Ware replace their predecessors and expand to Danubian and Nordic areas of western Germany. One related branch invades Denmark and southern Sweden (]), while the mid-Danubian basin, though showing more continuity, shows also clear traits of new Indo-European elites (culture of ]). | |||

| Though the use of ] started much earlier in the Aegean area (c. 3.200 BC), c. 2300 BC can be considered typical for the start of the Bronze Age in Europe in general. | |||

| Simultaneously, in the west, the peoples of Artenac reach Belgium. With the partial exception of Vucedol, the Danubian cultures, so buoyant just a few centuries ago, are wiped off the map of Europe. | |||

| * c. 2300 BC, the Central European cultures of ], ], ] and pre-] started working bronze, a technique that reached them through the Balkans and Danube. | |||

| The rest of the period is the story of a mysterious phenomenon: the ]. This group seems to be of mercantile character and to like being buried according to a very specific, almost invariable, ritual. Nevertheless, out of their original area of western Central Europe, they appear only inside local cultures, so they never invaded and assimilated but rather went to live among those peoples, keeping their way of life. This is why they are believed to be merchants. | |||

| * c. 1800 BC, the culture of ], in Southwestern Spain, was substituted by that of ], fully of the Bronze Age, which may well have been a centralised state. | |||

| * c. 1700 BC is considered a reasonable date to place the start of ], after centuries of infiltration of Indo-European Greeks of an unknown origin. | |||

| * c. 1600 BC, most of these Central European cultures were unified in the powerful ]. Simultaneously but unrelatedly, the culture of ] started Phase B, which was characterised by a detectable Aegean influence ('']'' burials). About then, it is believed that ] fell under the rule of the ]. | |||

| * Around 1300 BC, the Indo-European cultures of Central Europe, such as ], ] and certainly ], changed the cultural phase conforming to the expansionist ] culture, starting a quick expansion that brought them to occupy most of the Balkans, Asia Minor, where they destroyed the ] (conquering the secret of ] ]), northeastern Italy, parts of France, Belgium, the Netherlands, northeastern Spain and southwestern England. | |||

| Derivations of the sudden expansion were the ], who attacked Egypt unsuccessfully for some time, including the ] (]?) and the ], most likely Hellenised members of the group that ended invading Greek itself and destroying the might of ] and later ]. | |||

| The rest of the continent remains mostly unchanged and in apparent peace. | |||

| Simultaneously, around then, the culture of ], which lasted 1300 years in its urban form, vanishes into a less spectacular one but finally with bronze. The centre of gravity of the Atlantic cultures (the ] complex) was now displaced towards Great Britain. Also about then, the ], the possible precursor of the ], appeared in central Italy, possibly with an Aegean origin. | |||

| From c. 2300 BCE the first Beaker Pottery appears in Bohemia and expands in many directions but particularly westward, along the Rhone and the sea shores, reaching the culture of Vila Nova (Portugal) and Catalonia (Spain) as their limits. | |||

| <gallery> | |||

| Simultaneously but unrelatedly, c. 2200 BCE in the Aegean region, the ] culture decays, being substituted by the new palatine phase of the ] culture of ]. | |||

| File:Knossos1.jpg|] palace at ], Crete, c. 1700 BC | |||

| File:Mycenae 3a.jpg|] diadem, Greece, c. 1600 BC | |||

| File:Treasury of Atreus Mycenae.jpg|], Greece, c. 1300 BC | |||

| File:Bush Barrow.jpg|], ], 1900 BC | |||

| File:Solvognen-00100.jpg|], ], 1500 BC | |||

| File:Diadem1.jpg|] gold diadem, Spain, 1600 BC | |||

| File:Nuraghe Santu Antine 02.jpg|], Sardinia, c. 1600 BC | |||

| File:Navicella nuragica.jpg|] ship model, Sardinia, 1000 BC | |||

| File:Valchitran-treasure.jpg|], Bulgaria, c. 1300 BC | |||

| File:В музее - заповеднике Аркаим.jpg|] chariot, Russia, c. 2000 BC | |||

| File:Ricostruzione grafica della Terramara di Montale (Modena), disegno di Riccardo Merlo.jpg|], Italy, 1650–1150 BC | |||

| File:Età del bronzo finale, due spade, 1300-800 ac ca..JPG|], ], 1000 BC | |||

| File:Neues Museum, Berlin 2017 099.jpg|], Germany, c. 1000 BC | |||