| Revision as of 22:35, 7 April 2010 editEvlekis (talk | contribs)30,289 edits →South Slavic peoples← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 15:15, 24 November 2024 edit undo156.197.13.163 (talk)No edit summaryTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Subgroup of Slavic peoples who speak the South Slavic languages}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=September 2020}} | |||

| {{refimprove|date=June 2022}} | |||

| {{Infobox ethnic group | |||

| | group = South Slavs | |||

| | native_name = <br />Јужни Славени/Južni Slaveni (])<br />Южни славяни (])<br />Južni Slaveni (])<br />Јужни Словени (])<br />Južni Sloveni/Јужни Словени (])<br />{{lang|sr-Cyrl|i=unset|Јужни Словени}}/{{lang|sr-Latn|i=unset|Južni Sloveni}} (])<br />Južni Slovani (]) | |||

| | image = ] | |||

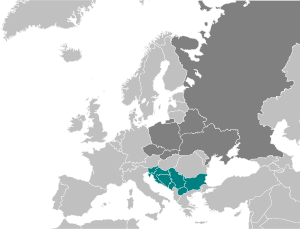

| | caption = {{leftlegend|#008080|Countries where a ] is the national language|outline=grey}}{{leftlegend|#808080|Countries where ] and ] are the national language|outline=grey}} | |||

| | pop = {{circa}} 30 million | |||

| | regions = ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | langs = ]:<br/>]<br/>]<br/>]:<br/>]<br>{{small|(], ], ], ])}}<br/>] | |||

| | rels = ] ]:<br/>(], ], ] and ]){{Citation needed|date=June 2022}}<br/><br/>] ]:<br/>(], ], ], ] and ]){{Citation needed|date=June 2022}}<br/><br/>] ]:<br/> (], ], ], ] and ]){{Citation needed|date=June 2022}} | |||

| | related = Other ] | |||

| }} | |||

| '''South Slavs''' are ] who speak ] and inhabit a contiguous region of ] comprising the eastern ] and the ]. Geographically separated from the ] and ] by ], ], ], and the ], the South Slavs today include ], ], ], ], ], ] and ]. | |||

| In the 20th century, the country of ] (from ], literally meaning "South Slavia" or "South Slavdom") united a majority of the South Slavic peoples and lands—with the exception of Bulgarians and Bulgaria—into a single state. The ] concept of ''Yugoslavia'' emerged in late 17th-century Croatia, at the time part of the ], and gained prominence through the 19th-century ]. The ], renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929, was proclaimed on 1 December 1918, following the unification of the ] with the kingdoms of ] and ]. With the ] in the early 1990s, several independent sovereign states were formed. | |||

| The '''South Slavs''' are a southern branch of the ] that live mainly in the ]. Geographically, the South Slavs are native to the southern ], the eastern ] and the ] and they speak ]. Numbering close to 35 million, the South Slavs include ], ], ], ], ], ] and ]. | |||

| The term "]" was and sometimes is still used as a synonym for "South Slavs", but it usually excludes Bulgarians since Bulgaria never formed part of the former Yugoslavia. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| {{see|Slavic peoples|Early Slavs}} | |||

| ==Terminology== | |||

| ===Early accounts=== | |||

| The South Slavs are known in Serbian, Macedonian, and Montenegrin as ''Južni Sloveni'' ({{cyrl|Јужни Словени}}); in Bulgarian as ''Yuzhni Slavyani'' ({{cyrl|Южни славяни}}); in Croatian and Bosnian as ''Južni Slaveni''; and in Slovene as ''Južni Slovani''. The Slavic root '']'' means 'south'. The ] itself was used by 6th-century writers to describe the southern group of Early Slavs (the '']''); West Slavs were called '']'' and East Slavs '']''.{{sfn|Kmietowicz|1976}} The South Slavs are also called ''Balkan Slavs''.<ref>{{harvnb|Kmietowicz|1976}}, {{harvnb|Vlasto|1970}}</ref> | |||

| Little is known about the Slavs before the 5th century AD. Their history prior to this can only be tentatively hypothesized via archeological and linguistic studies. Much of what we know about their history after the 500s is from the works of ] historians. | |||

| Another name popular in the early modern period was ''Illyrians'', using the name of a pre-Slavic Balkan people, a name first adopted by Dalmatian intellectuals in the late 15th century to refer to South Slavic lands and population.{{sfn|URI|2000|p=104}} It was then used by the ] and ], and notably adopted by the 19th-century Croatian ].{{sfn|Hupchick|2004|p=199}} Eventually, the idea of ] appeared, aimed at uniting all South Slav-populated territories into a common state. From this idea emerged ]—which, however, did not include ].{{Citation needed|date=June 2022}} | |||

| In his work ''De Bellis'', ] portrays the Slavs as unusually tall and strong, with a tan complexion and reddish-blonde hair, living a rugged and primitive life. They lived in huts, often distant from one another and often changed their place of abode. They were not ruled by a single leader, but for a long time lived in a "democracy" (i.e. anarchy). They probably believed in many Gods, but Procopius suggests they believed ] god. He has often been identified as ], the creator of lightning. The Slavs went into battle on foot, charging straight at their enemy, armed with spears and small shields, but they did not wear armour. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| This information is supplanted by Pseudo-Marice's work ''Strategikon'', describing the Slavs as a numerous but disorganised and leaderless people, resistant to hardship and not allowing themselves to be enslaved or conquered. They made their homes in forests, by rivers and wetlands.<ref>Fouracre, Paul. ''The Cambridge Medieval History'', Volume I.</ref> ] states that the Slavs "have their homelands on the ], not far from the northern bank." Subsequent information about early Slavic states and the Slavs' interaction with the Greeks comes from '']'' by Emperor ] Porphyrogenitus, the compilations of ''Miracles of St. Demetrius'', ''History'' by ] and the '']''. | |||

| {{main|Slavic migrations to Southeastern Europe}} | |||

| === |

===Early South Slavs=== | ||

| {{main|Early Slavs|Sclaveni|Antes (people)}} | |||

| {{see|Slavic settlement of the Eastern Alps}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The Proto-Slavic ] is the postulated area of Slavic settlement in ] and ] during the first millennium AD, with its precise location debated by archaeologists, ethnographers and historians.<ref>{{harvnb|Kobyliński|2005|pp=525–526}}, {{harvnb|Barford|2001|p=37}}</ref> None of the proposed homelands reaches the ] in the east, over the ] in the southwest or the ] in the south, or past ] in the west.<ref>{{harvnb|Kobyliński|2005|p=526}}, {{harvnb|Barford|2001|p=332}}</ref> Traditionally, scholars place it in the marshes of Ukraine, or alternatively between the ] and the ];{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=25}} however, according to F. Curta, the homeland of the southern Slavs mentioned by 6th-century writers was just north of the ].{{sfn|Curta|2006|p=56}} Little is known about the Slavs before the 5th century, when they began to spread out in all directions.{{Citation needed|date=June 2022}} | |||

| Scholars tend to place the Slavic '']'' in the ] of ]. From the 5th century, they supposedly spread outward in all directions. The Balkans was one of the regions which lay in the path of the expanding Slavs. | |||

| ] ({{floruit | 6th century CE}}), ] ({{circa | 500}} - {{circa | 565}}) and other ] authors provide the probable earliest references to southern Slavs in the second half of the 6th century.{{sfn|Curta|2001|pp=71–73}} Procopius described the ] and ] as two barbarian peoples with the same institutions and customs since ancient times, not ruled by a single ] but living under democracy,<ref>{{harvnb|James|2014|p=95}}, {{harvnb|Kobyliński|1995|p=524}}</ref> while Pseudo-Maurice called them a numerous people, undisciplined, unorganized and leaderless, who did not allow enslavement and conquest, and resistant to hardship, bearing all weathers.{{sfn|Kobyliński|1995|pp=524–525}} They were portrayed by Procopius as unusually tall and strong, of dark skin and "reddish" hair (neither ] nor ]), leading a primitive life and living in scattered huts, often changing their residence.{{sfn|Kobyliński|1995|p=524}} Procopius said they were ], believing in the god of lightning (]), the ruler of all, to whom they sacrificed cattle.{{sfn|Kobyliński|1995|p=524}} They went into battle on foot, charging straight at their enemy, armed with spears and small shields, but they did not wear armour.{{sfn|Kobyliński|1995|p=524}} | |||

| Regarding the Slavs mentioned by 6th century Byzantine chroniclers, Florin Curta states that their 'homeland' was north of the Danube and not in the Belarusian-Ukrainian borderlands.<ref>Curta, Florin and Stephenson, Paul. ''Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500-1250''. Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0521815398, p. 56. "The Slavic "homeland," at least for the sixth-century authors who wrote about the Slavs, was north of the Lower Danube, not in the Belarusian-Ukrainian borderlands."</ref> He clarifies that their itinerant form of agriculture (they lacked the knowledge of crop rotation) "may have encouraged mobility on a micro regional scale". Material culture from the Danube suggests that there was an evolution of Slavic society between the early 600s and the 700s. As the Byzantines re-asserted the Danubian defences in the mid 500s, the Slavs' yield of pillaged goods dropped. As a reaction to this economic isolation, and external threats (e.g. from Avars and Byzantines), political and military mobilisation occurred. Archeological sites from the late 600s show that the earlier settlements which were merely a non-specific collection of hamlets began to evolve into larger communities with differentiated areas (e.g. designated areas for public feasts as well as an 'industrial' area for craftsmanship). As community elites rose to prominence, they came to "embody a collective interest and responsibility" for the group. "If that group identity can be called ethnicity, and if that ethnicity can be called Slavic, then it certainly formed in the shadow of Justinian's forts, not in the Pripet marshes."<ref>Curta, Florin and Stephenson, Paul. ''Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500-1250''. Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0521815398, p. 61.</ref> | |||

| While archaeological evidence for a large-scale migration is lacking, most present-day historians claim that Slavs invaded and settled the Balkans in the 6th and 7th centuries.{{sfn|Fine|1991|pp=26–41}} According to this dominant narrative, up until the late 560s their main activity southward across the Danube was raiding, though with limited Slavic settlement mainly through Byzantine colonies of '']''.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=29}} The ] and ] frontier was overwhelmed by large-scale Slavic settlement in the late 6th and early 7th century.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=33}} What is today ] was an important geo-strategical Byzantine province, through which the '']'' crossed.{{sfn|Živković|2002|p=187}} This area was frequently intruded upon by ] in the 5th and 6th centuries.{{sfn|Živković|2002|p=187}} From the Danube, the Slavs commenced raiding the Byzantine Empire on an annual basis from the 520s, spreading destruction, taking loot and herds of cattle, seizing prisoners and capturing fortresses. Often, the Byzantine Empire was stretched, defending its rich Asian provinces from Arabs, Persians and others. This meant that even numerically small, disorganised early Slavic raids were capable of causing much disruption, but could not capture the larger, fortified cities.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=29}} The first Slavic raid south of the Danube was recorded by Procopius, who mentions an attack of the Antes, "who dwell close to the Sclaveni", probably in 518.<ref>{{harvnb|James|2014|p=95}}, {{harvnb|Curta|2001|p=75}}</ref> Sclaveni are first mentioned in the context of the military policy on the Danube frontier of Byzantine Emperor ] (r. 527–565).{{sfn|Curta|2001|p=76}} Throughout the 6th century, Slavs raided and plundered deep into the Balkans, from Dalmatia to Greece and Thrace, and were also at times recruited as Byzantine mercenaries, fighting the ].{{sfn|Curta|2001|pp=78–86}} Justinian seems to have used the strategy of ']', and the Sclaveni and Antes are mentioned as fighting each other.{{sfn|James|2014|p=97}} The Antes are last mentioned as anti-Byzantine belligerents in 545, and the Sclaveni continued to raid the Balkans.<ref name=Byzantinoslavica-2003-78>{{cite book|title= Byzantinoslavica |volume= 61–62 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=twwrAQAAIAAJ |year=2003 |publisher= Academia |pages= 78–79}}</ref> In 558 the ] arrived at the Black Sea steppe, and defeated the Antes between the Dnieper and Dniester.{{sfn|Kobyliński|1995|p=536}} The Avars subsequently allied themselves with the Sclaveni,{{sfn|Kobyliński|1995|p=537–539}} although there was an episode in which the Sclavene ] ({{fl. | 577–579}}), the first Slavic chieftain recorded by name, dismissed Avar suzerainty and retorted that "Others do not conquer our land, we conquer theirs so it shall always be for us", and had the Avar envoys slain.{{sfn|Curta|2001|pp=47, 91}} By the 580s, as the Slav communities on the Danube became larger and more organized, and as the Avars exerted their influence, raids became larger and resulted in permanent settlement. Most scholars consider the period of 581–584 as the beginning of large-scale Slavic settlement in the Balkans.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=31}} F. Curta points out that evidence of substantial Slavic presence does not appear before the 7th century and remains qualitatively different from the "Slavic culture" found north of the ].{{sfn|Curta|2001|p=308}} In the mid-6th century, the Byzantines re-asserted their control of the Danube frontier, thereby reducing the economic value of Slavic raiding. This growing economic isolation, combined with external threats from the Avars and Byzantines, led to political and military mobilisation. Meanwhile, the itinerant form of agriculture (lacking ]) may have encouraged micro-regional mobility. Seventh-century archaeological sites show earlier hamlet-collections evolving into larger communities with differentiated zones for public feasts, craftmanship, etc.{{sfn|Curta|2007|p=61}} It has been suggested that the Sclaveni were the ancestors of the Serbo-Croatian group while the Antes were those of the ] ], with much mixture in the contact zones.{{sfn|Hupchick|2004}}{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=26}} The diminished pre-Slavic inhabitants, also including Romanized native peoples,{{Cref2|a}} fled from the barbarian invasions and sought refuge inside fortified cities and islands, whilst others fled to remote mountains and forests and adopted a ] lifestyle.{{sfn|Fine|1991|pp= 37}} The Romance-speakers within the fortified ] managed to retain their culture and language for a long time.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=35}} Meanwhile, the numerous Slavs mixed with and assimilated the descendants of the indigenous population.{{sfn|Fine|1991|pp= 38, 41}} | |||

| The Byzantines broadly grouped the numerous Slav tribes into two groups: the Sclavenoi and ].<ref name="Hupchick, Dennis P. 2004">Hupchick, Dennis P. ''The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism.'' Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. ISBN 1403964173</ref> Apparently, the ''Sclavenes'' group were based along the middle Danube, whereas the ''Antes'' were at the lower Danube, in ]. Some, such as Bulgarian scholar Zlatarsky, suggest that the ''Sclavenes'' group settled the western Balkans, whilst offshoots of the ''Antes'' settled the eastern regions (roughly speaking).<ref name="Hupchick, Dennis P. 2004"/> From the Danube, they commenced raiding the Byzantine Empire from the 520s, on an annual basis. They spread about destruction, taking loot and herds of cattle, seizing prisoners and taking fortresses. Often, the Byzantine Empire was stretched defending its rich Asian provinces from Arabs, Persians and Turks. This meant that even numerically small, disorganised early Slavic raids were capable of causing much disruption, but could not capture the larger, fortified cities on the Aegean coast. By the 580s, as the Slav communities on the Danube became larger and more organised, and as the Avars exerted their influence, raids became larger and resulted in permanent settlement. In 586 AD, as many as 100,000 Slav warriors raided Thessaloniki. By 581, many Slavic tribes had settled the land around Thessaloniki, though never taking the city itself, creating a ''Macedonian Sclavinia''.<ref>Cambridge Medieval Encyclopedia, Volume II.</ref> As John of Ephesus tells us in 581: "the accursed people of the Slavs set out and plundered all of Greece, the regions surrounding Thessalonica, and Thrace, taking many towns and castles, laying waste, burning, pillaging, and seizing the whole country." However, John exaggerated the intensity of the Slavic incursions since he was influenced by his confinement in Constantinople from 571 up until 579.<ref>Curta, Florin. ''The Making of the Slavs''. Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 48. "Beginning in 571, John spent eight years in prison. Most of Book VI, if not the entire third part of the ''History'', was written during this period of confinement...John was no doubt influenced by the pessimistic atmosphere at Constantinople in the 580s to overstate the intensity of Slavic ravaging."</ref> Moreover, he perceived the Slavs as God's instrument for punishing the persecutors of the ].<ref>Curta, Florin. ''The Making of the Slavs''. Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 48. "On the other hand, God was on their side, for in John's eyes, they were God's instrument for punishing the persecutors of the Monophysites. This may also explain why John insists that, beginning with 581 (just ten years after Justin II started persecuting the Monophysites), the Slavs began occupying Roman territory..."</ref> By 586, they managed to raid the western Peloponnese, Attica, Epirus, leaving only the east part of Peloponnese, which was mountainous and inaccessible. The final attempt to restore the northern border was from 591-605, when the end of conflicts with Persia allowed Emperor Maurice to transfer units to the north. However he was deposed after a military revolt in 602, and the Danubian frontier collapsed one and a half decades later (''Main article: ]''). | |||

| Subsequent information about Slavs' interaction with the Greeks and early Slavic states comes from the 10th-century text {{lang|la|]}} (DAI) written by Byzantine Emperor ], from the 7th-century compilations of the '']'' (MSD) and from the ''History'' by ] ({{circa | 630}}). DAI mentions the beginnings of the Croatian, Serbian and Bulgarian states from the early 7th to the mid-10th century. MSD and Theophylact Simocatta mention the Slavic tribes in Thessaly and Macedonia at the beginning of the 7th century. The 9th-century '']'' (RFA) also mention Slavic tribes in contact with the ].{{Citation needed|date=June 2022}} | |||

| ] on the Serbo-Romanian border.]] | |||

| ===Middle Ages=== | |||

| The ] arrived in Europe in 558. Although their identity would not last, the Avars greatly impacted the events of the Balkans. They settled the Carpathian plain, west of the main Slavic settlements. They crushed the ] and pushed the ] into Italy, essentially opening up the western Balkans. They asserted their authority over many Slavs, who were divided into numerous petty tribes. Many Slavs were relocated to the Avar base in the Carpathian basin and were galvanized into an effective infantry force. Other Slavic tribes continued to raid independently, sometime coordinating attacks as allies of the Avars. Others still split into Imperial lands as they fled from the Avars. Despite being paid stipends, the Avars continued to raid the entire Balkans. The Avars and their Slavic allies tended to focus on the western Balkans, whilst independent Slavic tribes predominated in the east. Following the unsuccessful siege of Constantinople in 626, the Avars reputation diminished, and the confederacy was troubled by civil wars between the Avars and their Bulgar and Slav clients. Their rule contracted to the region of the Carpathian basin. Archeological evidence show that there was intermixing of Slavic, Avar and even Gepid cultures, suggesting that the later ''Avars'' were an amalgamation of different peoples. This contributed to the rise of a Slavic ''noble class''. The Khanate collapsed after ongoing defeats at the hands of Franks, Bulgars and Slavs (c. 810), and the Avars ceased to exist. What remained of the Avars furthermore absorbed by the Slavs and Bulgars. | |||

| {{see also|Saqaliba}} | |||

| By 700 AD, Slavs had settled in most of Central and Southeast Europe, from Austria even down to the Peloponnese of Greece, and from the Adriatic to the Black Sea, with the exception of the coastal areas and certain mountainous regions of the Greek peninsula.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=36}} The ], who arrived in Europe in the late 550s and had a great impact in the Balkans, had from their base in the Carpathian plain, west of main Slavic settlements, asserted control over Slavic tribes with whom they besieged Roman cities. Their influence in the Balkans however diminished by the early 7th century and they were finally defeated and disappeared as a power at the turn of the 9th century by ] and the ].{{sfn|Fine|1991|pp=29–43}} The first South Slavic polity and regional power was ], a state formed in 681 as a union between the much numerous ] ] and the ] of ]. The scattered Slavs in Greece, the ''Sklavinia'', were Hellenized.{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=41}} Romance-speakers lived within the fortified ].{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=35}} Traditional historiography, based on DAI, holds that the migration of ] and ] to the Balkans was part of a second Slavic wave, placed during Heraclius' reign.{{sfn|Curta|2001|p=66}} | |||

| ] and ] are two tribes mentioned amongst the many Slavic tribes already in the Balkans. We know little about their origins. According to ''De Administrando Imperio'', Emperor Heraclius invited them as ''foederati'' to defeat the Avars. They migrated from their homeland in southern Poland between 615 and 640 AD. However, apart from this (often disputed) document, we have no evidence of their migration specifically. Some suggest that they arrived to the Balkans with the rest of the Slavic migrations, only to rise to prominence as some sort of a leading ''clan'' amongst neighbouring Slavic tribes.<ref name="Fine, John Van Antwerp 1983">Fine, John Van Antwerp. ''The Early Medieval Balkans''. University of Michigan Press, 1983. ISBN 0472081497</ref> | |||

| Inhabiting the territory between the Franks in the north and Byzantium in the south, the Slavs were exposed to competing influences.{{sfn|Portal|1969|p=90}} In 863 to Christianized ] were sent two Byzantine brothers monks ], Slavs from Thessaloniki on missionary work. They created the ] and the first Slavic written language, ], which they used to translate Biblical works. At the time, the West and South Slavs still spoke a similar language. The script used, ], was capable of representing all Slavic sounds, however, it was gradually replaced in Bulgaria in the 9th century, in Russia by the 11th century{{sfn|Portal|1969|pp=90–92}} Glagolitic survived into the 16th century in Croatia, used by Benedictines and Franciscans, but lost importance during the ] when Latin replaced it on the Dalmatian coast.{{sfn|Portal|1969|p=92}} Cyril and Methodius' disciples found refuge in already ], where the ] became the ecclesiastical language.{{sfn|Portal|1969|p=92}} ] was developed during the 9th century AD at the ] in ].<ref>{{cite book | first=Francis | last=Dvornik |title=The Slavs: Their Early History and Civilization | url=https://archive.org/details/slavstheirearlyh00dvor | url-access=limited | quote = The Psalter and the Book of Prophets were adapted or "modernized" with special regard to their use in Bulgarian churches, and it was in this school that glagolitic writing was replaced by the so-called Cyrillic writing, which was more akin to the Greek uncial, simplified matters considerably and is still used by the Orthodox Slavs. | year=1956 |place=Boston | publisher=American Academy of Arts and Sciences |page=}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/southeasterneuro0000curt |url-access=registration |quote=Cyrillic preslav. |title=Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250|series=Cambridge Medieval Textbooks|author= Florin Curta|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=2006|isbn=978-0521815390|pages= –222}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|chapter-url= https://books.google.com/books?id=J-H9BTVHKRMC&q=+preslav+eastern&pg=PR3-IA34|chapter= The Orthodox Church in the Byzantine Empire|title= Oxford History of the Christian Church|author= J. M. Hussey, Andrew Louth|publisher= Oxford University Press|year= 2010|isbn= 978-0191614880|pages= 100|access-date= 20 October 2020|archive-date= 6 October 2023|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20231006145150/https://books.google.com/books?id=J-H9BTVHKRMC&q=+preslav+eastern&pg=PR3-IA34#v=snippet&q=preslav%20eastern&f=false|url-status= live}}</ref> The earliest Slavic literary works were composed in ], ] and Dalmatia. The religious works were almost exclusively translations, from Latin (Croatia, Slovenia) and especially Greek (Bulgaria, Serbia).{{sfn|Portal|1969|p=92}} In the 10th and 11th centuries the ] led to the creation of various regional forms like ] and ].{{sfn|Portal|1969|p=92}} Economic, religious and political centres of ] and ] contributed to the important ] in the ].{{sfn|Portal|1969|p=93}} The ] sect, derived from Manichaeism, was deemed heretical, but managed to spread from ] to Bosnia (where it gained a foothold),{{sfn|Portal|1969|pp=93–95}} and France (]).{{Citation needed|date=June 2022}} | |||

| ] came under Germanic rule in the 10th century and came permanently under Western (Roman) Christian sphere of influence.{{sfn|Portal|1969|p=96}} What is today Croatia came under Eastern Roman (Byzantine) rule after the Barbarian age, and while most of the territory was Slavicized, a handful of fortified towns, with mixed population, remained under Byzantine authority and continued to use Latin.{{sfn|Portal|1969|p=96}} Dalmatia, now applied to the narrow strip with Byzantine towns, came under the Patriarchate of Constantinople, while the Croatian state remained pagan until Christianization during the reign of ], after which religious allegiance was to Rome.{{sfn|Portal|1969|p=96}} Croats threw off Frankish rule in the 9th century and took over the Byzantine Dalmatian towns, after which Hungarian conquest led to Hungarian suzerainty, although retaining an army and institutions.{{sfn|Portal|1969|p=96–97}} Croatia lost much of Dalmatia to the Republic of Venice which held it until the 18th century.{{sfn|Portal|1969|p=97}} Hungary governed Croatia through a duke, and the coastal towns through a '']''.{{sfn|Portal|1969|p=97}} A feudal class emerged in the Croatian hinterland in the late 13th century, among whom were the ], ] and most notably the ].{{sfn|Portal|1969|p=97–98}} Dalmatian fortified towns meanwhile maintained autonomy, with a Roman patrician class and Slavic lower class, first under Hungary and then Venice after centuries of struggle.{{sfn|Portal|1969|p=98}} | |||

| By 700 AD, Slavs inhabited most of the Balkans, from Austria to the Peloponnese, and from the Adriatic to the Black seas, with the exception of the coastal areas of the Greek peninsula. However, archaeological traces of Slavic penetration into the Balkans is scant, especially in the period prior to the 700s. This has led scholars to cast doubt on the accuracy of the historical sources, which all describe often large scale settlements by the Slavs throughout the Balkans, including southern Greece.<ref>Curta, Florin. ''The Making of the Slavs''. Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp. 307-308. "Furthermore, the archaeological evidence discussed in this chapter does not match any long-distance migratory pattern. Assemblages in the Lower Danube area, both east and south of the Carpathian mountains, antedate those of the alleged Slavic ''Urheimat'' in the Zhitomir Polesie, on which Irina Rusanova based her theory of the Prague-Korchak-Zhitomir type."</ref> | |||

| ] described two kinds of South Slavic people, the first of swarthy complexion and dark hair, living near the Adriatic coast, and the other as light, living in the hinterland.{{citation needed|date=March 2018}} | |||

| ===Interaction with the Balkan population=== | |||

| Prior to the advent of Roman rule, a number of native or autochthonous populations had lived in the Balkans since ancient times. There were, of course, the Hellenes south of the ]. To the north, there were ] in the western portion (]), ] in Thrace (modern Bulgaria and eastern Macedonia), and ] in ] (northern Bulgaria and northeastern Serbia) and ] (modern Romania). They were mainly tribalistic and generally lacked awareness of any greater ethno-political affiliations. Over the classical ages, they were at times invaded, conquered and influenced by ], ] and ]. Roman influence, however, was limited to the cities, which were concentrated along the Dalmatian coast, in Greece, and a few scattered cities inside the Balkan interior particularly along the river Danube (], ], ]). Roman citizens from throughout the empire settled in these cities and in the adjacent countryside. The vast hinterland was still populated by indigenous peoples who likely retained their own tribalistic character.<ref name="Fine, John Van Antwerp 1983"/> | |||

| ===Early modern period=== | |||

| Following the fall of Rome and numerous barbarian raids, the population in the Balkans dropped, as did commerce and general standards of living. Many people were killed, or taken prisoner by invaders. This demographic decline was particularly attributed to a drop in the number of indigenous peasants living in the rural countryside. They were the most vulnerable to raids and were also hardest hit by the financial crises that plagued the falling empire. However, the Balkans were not desolate. Only certain areas tended to be affected by the raids (lands around major land routes). People sought refuge inside fortified cities, whilst others fled to remote mountains and forests, joining their non-Romanized kin and adopting a transhumant pastoral lifestyle. The larger cities were able to persevere, even flourish, through the hard times. Archaeological evidence suggests that the culture in the cities changed whereby Roman-styled forums and large public buildings were abandoned and cities were modified (i.e. built on top of hills or cliff-tops and fortified by walls). The centerpiece of such cities was the church. This transformation from a Roman culture to a ''Byzantine'' one was paralleled by a rise of a new ruling class: the old land-owning aristocracy gave way to rule by military elites and the clergy.<ref name="Curta 2006">Curta, Florin and Stephenson, Paul. ''Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500-1250''. Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 0521815398</ref> | |||

| {{unreferenced section|date=June 2022}} | |||

| Through Islamization, communities of Slavic Muslims emerged, which survive until today in Bosnia, south Serbia, North Macedonia, and Bulgaria.{{Citation needed|date=June 2022}} | |||

| While ] has its origins in the 17th-century Slavic Catholic clergymen in the Republic of Venice and Republic of Ragusa, it crystallized only in the mid-19th century amidst rise of nationalism in the Ottoman and Habsburg empires.{{Citation needed|date=June 2022}} | |||

| In addition to the autochthons, there were remnants of previous invaders such as "]" and various ] when the Slavs arrived. ] (such as the ]) are recorded to have still lived in the ] region of the Danube.<ref name="Fine, John Van Antwerp 1983"/> | |||

| == Population == | |||

| As the Slavs spread south into the Balkans, they interacted with the numerous peoples and cultures. Since their lifestyle revolved around agriculture, they preferentially settled rural lands along the major highway networks which they moved along. Whilst they could not take the larger fortified towns, they looted the countryside and captured many prisoners. In his ''Strategikon'', Pseudo-Maurice noted that it was commonplace for Slavs to accept newly acquired prisoners into their ranks. Despite Byzantine accounts of "pillaging" and "looting", it is possible that many indigenous peoples voluntarily assimilated with the Slavs. The Slavs lacked an organised, centrally ruled organisation which actually hastened the process of willful Slavicisation. The strongest evidence for such a co-existence is from archaeological remains along the Danube and Dacia known as the ''Ipoteşti-Cândeşti culture''. Here, the villages dating back to the 6th century represent a continuity with the earlier Slavic '']''; modified by admixture with Daco-Getic, Daco-Roman and/or Byzantine elements within the same village. Such interactions awarded the pre-Slavic populace protection within the ranks of a dominant, new tribe. In return, they contributed to the genetic and cultural development the South Slavs. This phenomenon ultimately led to an exchange of various loan-words. For example, the Slavic name for "Greeks", ''Grci'', is derived from the Latin ''Graecus'' presumably encountered through the local Romanised populace. Conversely, the Vlachs borrowed many Slavic words, especially pertaining to agricultural terms. Whether any of the original Thracian or Illyrian culture and language remained by the time Slavs arrived is a matter of debate. It is a difficult issue to analyse because of the overriding Greek and Roman influence in the region. | |||

| {{Main|Slavs#Population}} | |||

| ==Languages== | |||

| Over time, more and more of the Latin-speaking natives (generally referred to as Vlachs) were assimilated (such that, in the western Balkans, ''Vlach'' came be a socio-occupational term rather than ethnic term.<ref>Cirkovic, Sima. ''The Serbs''. Blackwell Publishing, 2004. ISBN 0631204717</ref> The Romance speakers within the fortified Dalmatian cities managed to retain their culture and language for a longer time, Dalmatian was spoken until the high Middle Ages. However, they too were eventually assimilated into the body of Slavs. In contrast, the Romano-Dacians in Wallachia managed to maintain their Latin-based language, despite much Slavic influence. After centuries of peaceful co-existence, the groups fused to form the Romanians. | |||

| {{refimprove section|date=June 2022}} | |||

| {{main|South Slavic languages}} | |||

| The ], one of three branches of the ] family (the other being ] and ]), form a ]. It comprises, from west to east, the official languages of ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]. The South Slavic languages are geographically divided from the rest of the Slavic languages by areas where Germanic (Austria), Hungarian and Romanian languages prevail. | |||

| ===Relationship with Byzantium=== | |||

| ] | |||

| South Slavic ]s are: | |||

| Byzantine literary accounts (i.e. Procopius, John of Ephesus, etc.) mention the Slavs raiding areas of Greece during the 580s. According to later sources such as ''The Miracles of Saint Demetrius'', the Drugubites, Sagudates, Belegezites, Baiunetes, and Berzetes laid siege to Thessaloniki in 614-616.<ref>Fine, John Van Antwerp. ''The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century''. Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1991, p. 41. "Between 614 and 616, at the same time that the Avars were leading their major offensive against Dalmatia, The Miracles of Saint Demetrius describes the attacks by five Slavic tribes by sea in small boats along the coasts of Thessaly, western Anatolia, and various Greek islands. They then decided to capture Thessaloniki in a combined land and sea attack. Under the walls of the city they camped with whole families. They were led by a chief (the Greek title used is exarch) named Chatzon."</ref> However, this particular event was in actuality of local significance.<ref>Curta, Florin. ''The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region c. 500-700''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 108. "I suggest therefore that in describing a local event – the attack of the Drugubites, Sagudates, Belegezites, Baiunetes, and Berzetes on Thessalonica – of relatively minor significance, the author of Book II framed it against a broader historical and administrative background, in order to make it appear as of greater importance. When all the other provinces and cities were falling, Thessalonica alone, under the protection of St Demetrius, was capable of resistance."</ref> In 626, a combined Gepid, Avar, Slav, and Bulgar army besieged Constantinople. The siege was broken, which had repercussions upon the power and prestige of the Avar khanate. Slavic sieges on Thessaloniki continued and in 677, a coalition of Rynchites, Sagudates, Draguvites and Strumanoi attacked. This time, the Belgezites did not participate and in fact supplied the besieged citizens of Thessaloniki with grain. | |||

| {{col-start}} | |||

| {{col-3}} | |||

| While en route to the Holy Land in 732, Willibald "reached the city of ], in the land of Slavinia". This particular passage from the ''Vita Willibaldi'' is interpreted as an indication of a Slavic presence in the hinterland of the Peloponnese. However, the text's value as an eyewitness account is significantly diminished by its use of ''Slavinia'', a term that betrays a pre-existing Constantinopolitan (rather than Peloponnesian) source.<ref>Curta, Florin. "Barbarians in Dark-Age Greece: Slavs or Avars?" ''Civitas Divino-Humana. In honorem annorum LX Georgii Bakalov''. Edited by Tsevetelin Stepanov and Veselina Vachkova, pp. 513-550. Sofia: Centăr za izsledvaniia na bălgarite Tangra TanNakRa IK, 2004. "The sojourn in Monemvasia does not seem to have been long, but the fact that Hugeburc reports the place as being 'in the land of Slavinia' is often interpreted as an indication of a Slavic presence in the hinterland. The Latin word Slawinia is a clear, though by no means unique, calque of the Greek form Sklavinia, which Theophanes used for polities attacked by Constans II in 656 and by Justinian II in 688. As such, the word betrays a Constantinopolitan, not Peloponnesian, source for Willibald's account. Whatever or whoever must have been in the hinterland of Monemvasia, it is significant that Hugebruc (or Willibald) employed the official terminology in use in Constantinople. As a consequence, the mention of Slavinia betrays a distant perspective, not an eyewitness account." </ref> In reference to the plague of 744-747, Constantine Porphyrogenitus wrote during the 10th century that "the entire country was Slavonized".<ref>Davis, Jack L. and Alcock, Susan E. ''Sandy Pylos: An Archaeological History from Nestor to Navarino''. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1998, p. 215. "The tenth century emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus noted that 'the whole country was Slavonized and became barbarous when'the deadly plague ravaged the universe, when Constantine, the one named after dung , held the scepter of the Romans.'"</ref> According to the ''The Life of Methodius'', the inhabitants of Thessaloniki are said to "speak pure Slavonic". It is important to note that many chroniclers in the past tended to exaggerate actual events for special effect.<ref>Vacalopoulos, Apostolos E. (translated by Ian Moles). ''Origins of the Greek Nation: The Byzantine Period, 1204-1461''. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1970, p. 2. "Fortunately, historians of today know only too well how the impressionable and unsophisticated chroniclers of the past, for all their sensitivity and perception, were prone to embroider the facts of history for special effect."</ref> | |||

| '''West:'''<br> | |||

| ] (])<br> | |||

| ], a prominent linguist and Indo-Europeanist, complements late medieval historical accounts by listing 429 Slavic toponyms from the Peloponnese.<ref>{{cite book |title=The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the 6 to the Late 12 Century |author=John Van Antwerp Fine |publisher=University of Michigan Press |year=1983 |isbn=9780472081493 |quote=First, there are toponyms; The German linguist Vasmer has listed some 429 from the Peloponnesus alone. Certain of his specific examples might be challenged, but the fact remains that many clearly Slavic names do exist there.|page=62}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://kroraina.com/knigi/en/mv/index.html |author=Max Vasmer |location=Berlin |publisher=Verlag der Akademie der Wissenschaften |title=Die Slaven in Griechenland |year=1941}}</ref> However, toponyms may not serve as reliable indicators of Slavic settlements since they can be attributed either to other groups or to tenants situated on monastic or lay estates.<ref>Vacalopoulos, Apostolos E. (translated by Ian Moles). ''Origins of the Greek Nation: The Byzantine Period, 1204-1461''. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1970, p. 6. "Since most Slav toponyms allude to some aspect of nature, they obviously derive from a peasant and shepherd culture. It is not always clear whether they were brought into Greece by Slavs who settled down permanently, by tenants situated on monastic and lay estates, or by the Vlachs, Arvanito-Vlachs, and Albanians, who became thoroughly intermixed with the Slavs, particularly in the western districts. The matter is further complicated by the fact that the toponyms represent the residual deposits of successive layers of history, which, in the case of Greek Macedonia at least, have been proved to belong to virtually every chronological period down to the twentieth century."</ref> | |||

| {{small|(], ], ], ])}}<br> | |||

| ] | |||

| Though medieval chroniclers attest to Slavic ''hordes'' occupying Byzantine territories, the archaeological evidence provides a contrasting viewpoint. According to Florin Curta, current archaeological data (i.e. burial assemblages, brooches, settlements, etc.) does not support the idea of a "Slavic tide" covering the Balkans (including Greece) before the 600s.<ref>Curta, Florin. ''The Making of the Slavs''. Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 308. "Nor does the idea of a "Slavic tide" covering the Balkans in the early 600s fit the archaeological data. South of the Danube river, no archaeological assemblage comparable to those found north of that river produced any clear evidence for a date earlier than ''c.'' 700."</ref> In fact, very little archaeological evidence found in the Balkans matches the settlement patterns found north of the Danube.<ref>Curta, Florin. ''The Making of the Slavs''. Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 308. "Though both Greece and Albania produced clear evidence of seventh-century burial assemblages, they have nothing in common with the "Slavic culture" north of the Danube river."</ref> The reasons for this are currently not clear despite attempts made by archaeologists such as ] to universally classify "Slavic" material culture that includes bow fibulae.<ref>Curta, Florin. "Female Dress and "Slavic" Bow Fibulae in Greece", ''Hesperia'', Vol. 74, Issue 1 (January-March 2005), pp. 101-146. "Werner produced the first classification of bow fibulae in Eastern Europe and attached the label "Slavic" to this class of artifacts. He divided his corpus into two classes (I and II), further subdivided on the basis of presumably different terminal lobes, shaped in the form of either a human face ("mask") or an animal head. Werner relied exclusively on visual, mostly intuitive, means for the grouping of his large corpus of brooches. The distribution of bow fibulae in Eastern Europe convinced him that the only factor responsible for the spread of this dress accessory in areas as far apart as Ukraine and Greece was the migration of the Slavs." </ref> Contrary to Werner, bow fibulae were not "index fossils" left behind by Slavic migrants or objects used to depict the formation of a distinct ethnic group. Instead, these female dress accessories possessed emblematic styles depicting the social status of local elites.<ref>Curta, Florin. "Female Dress and "Slavic" Bow Fibulae in Greece", ''Hesperia'', Vol. 74, Issue 1 (January-March 2005), pp. 101-146. "Not all "Slavic" bow fibulae of Werner's class I B should be dated to the same time within the seventh century, as Werner once thought. Some specimens may have been in fashion in the early 500s. The dissemination of bow fibulae into Greece is likely to indicate long-distance contacts between communities and to signal the rise of individuals having the ability both to entertain such contacts and to employ craftspeople sufficiently experienced to replicate ornamental patterns and brooch forms. Instead of treating "Slavic" bow fibulae as index fossils for the migration of the Slavs, we should therefore regard this emblematic style of brooch as an indication of contacts established by such individuals. Fibulae were primarily female dress accessories, and it is likely that high-status female burials mirrored the construction of the social identity of their husbands. The kind of identity symbolized is a matter dependent on the interpretation of "Slavic" bow fibulae. Wearing a fibula with scroll work decoration and cabochons may have given the wearer a social locus associated with images of power. Wearing a local reproduction of such a fibula was, no doubt, a very different statement, though still related to status. Beyond emulation, therefore, "Slavic" bow fibulae, especially cruder specimens without complicated scroll work ornaments, may have conveyed a message pertaining to group identity. Adherence to a brooch style helped to integrate isolated individuals—whether within the same region or widely scattered—into a group whose social boundaries crisscrossed those of local communities. "Slavic" bow fibulae were neither prototypical expressions of a preformed ethnic identity nor passports for immigrants from the Lower Danube region. During the early 600s, however, at the time of the general collapse of the Byzantine administration in the Balkans, access to and manipulation of such artifacts may have been strategies for creating a new sense of identity for local elites." </ref> Some authors point to the rapid adoption of aboriginal Balkan cultures by early Slav-speaking groups in specific areas such as Dalmatia. There, investigations of burial graves and cemetery types indicate an uninterrupted continuity of Late Antique traditions reflecting a contiguous demographic spread that chronologically matches with the arrival of Slavic-speaking groups.<ref>Ante Milošević. ''O kontinuitetu kasnoantičkih proizvoda u materijalnoj kulturi ranoga srednjeg vijeka na prostoru Dalmacije, Starohrvatska spomenička baština. Rađanje prvog hrvatskog kulturnog pejzaža''. Exegi monumentum, Znanstvena izdanja 3, Zagreb, 1996, UDK 930.85(497.5), ISBN 953-6100-25-8. p. 39. "Judging by the results of previous investigations, it seems more likely that the Slavs arriving to Dalmatia have immediately made contact with autochthonous population, and under their influence abandoned incineration giving precedence to inhumation. Beside the change of burial practice, Late Antique influences are also manifested in the funeral architecture (in Early Middle Ages, especially in Middle Dalmatia, dominant type of burial grave is one plated with stone) and the basic type of cemetery type, which is doubtless a continuation of Late Antique tradition, patterning more frequently in Dalmatia only after the second half of the fifth or the beginning of the sixth century unquestionably under Germanic influence."</ref> | |||

| {{col-3}} | |||

| '''East:'''<br> | |||

| Relations, if existent, between the Slavs and Greeks were probably peaceful apart from the (supposed) initial settlement and intermittent uprisings. Being agriculturalists, the Slavs probably traded with the Greeks inside towns.<ref name="Fine, John Van Antwerp 1983"/> Furthermore, some Greek villages continued to exist in the interior, probably governing themselves, possibly paying tribute to the Slavs. Some villages were probably mixed, and undoubtedly some degree of bi-directional assimilation already began to occur before re-Hellenization was completed by the emperors.<ref>Hupchick, Dennis. ''The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism''. Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. ISBN 1403964173</ref> | |||

| ]<br> | |||

| ]<br> | |||

| When the Byzantines were not fighting in their eastern territories, they were able to slowly regain imperial control. This was achieved through its ], referring to an administrative province on which an army corps was centered, under the control of a ''Strategos'' (governor). It aimed to assimilate the Slavs into the Byzantine socio-economic sphere. The first Balkan theme created was that in Thrace, in 680 AD. By 695, a second theme, "Hellas", was established. Its location was probably in eastern central Greece. Subduing the Slavs in these themes was simply a matter of accommodating the needs of the Slavic elites and providing them with incentives for their inclusion into the imperial administration. | |||

| {{col-3}} | |||

| {{col-end}} | |||

| However, Slavs elsewhere were far more difficult to subdue. It was not until 100 years later that a third theme would be established. In 782-84, the eunuch general Staurakios campaigned from Thessaloniki, south to Thessaly and into the Peloponnese. He captured many Slavs, moving them elsewhere especially ] (these Slavs were dubbed ''Slavesians''.<ref name="Curta 2006"/> Although he may have made some defeated Slav tribes pay homage, it is unlikely he subdued all of them. The theme of Macedonia was created sometime between 790 and 802. This theme was centered on Adrianople (i.e. east of the actual geographic entity). In 805, the theme of Peloponnesus was created. However, some local Slavic tribes ''Milings'' and ''Ezerites'' continued to revolt apparently angered by loss of lands and the threat of losing their independence.<ref name="Curta 2006"/> They were to remain independent until ] times. From the 800s, new themes continued to arise, although many were small and were carved out of original, larger themes. New themes in the 9th century included those of Thessaloniki and Dyrrachium. From these themes, Byzantine laws and culture flowed into the interior. | |||

| ], ], ], ])]] | |||

| The Serbo-Croatian varieties have strong structural unity and are regarded by most linguists as constituting one language.<ref>{{cite book|editor1-last=Comrie |editor1-first=Bernard |editor1-link=Bernard Comrie |editor2-last=Corbett |editor2-first=Greville G. |year=2002 |orig-year=1st. Pub. 1993 |title=The Slavonic Languages |location=London & New York |publisher=Routledge |oclc=49550401 |name-list-style=amp}}</ref> Today, ] has led to the codification of several distinct standards: Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian and Montenegrin. These Serbo-Croatian standards are all based on the ] dialect group. Other dialect groups, which have lower intelligibility with Shtokavian, are ] in ] and ] in ]. The dominance of Shtokavian across Serbo-Croatian speaking lands is due to historical westward migration during the Ottoman period. Slovene is South Slavic but has many features shared with West Slavic languages. The ] and ] are especially close, and there is no sharp delineation between them. In southeastern Serbia, dialects enter a transitional zone with Bulgarian and Macedonian, with features of both groups, and are commonly called ]. The Eastern South Slavic languages are Bulgarian and Macedonian. Bulgarian has retained more archaic Slavic features in relation to the other languages. Bulgarian has two main ] splits. Macedonian was codified in Communist Yugoslavia in 1945. The northern and eastern ] are regarded as transitional to Serbian and Bulgarian, respectively. Furthermore, in Greece there is a notable Slavic-speaking population ] and ]. Slavic dialects in western Greek Macedonia (], ]) are usually classified as ], those in eastern Greek Macedonia (], ]) and Western Thrace as ] and the central ones (], ]) as either Macedonian or transitional between Macedonian and Bulgarian.<ref name=Trudgill>Trudgill P., 2000, "Greece and European Turkey: From Religious to Linguistic Identity". In: Stephen Barbour and Cathie Carmichael (eds.), Language and Nationalism in Europe, Oxford : Oxford University Press, p.259.</ref><ref>Boeschoten, Riki van (1993): Minority Languages in Northern Greece. Study Visit to Florina, Aridea, (Report to the European Commission, Brussels), p. 13 "The Western dialect is used in Florina and Kastoria and is closest to the language used north of the border, the Eastern dialect is used in the areas of Serres and Drama and is closest to Bulgarian, the Central dialect is used in the area between Edessa and Salonica and forms an intermediate dialect"</ref> Balkan Slavic languages are part of a "]" with ]s shared with other non-Slavic languages in the Balkans.{{Citation needed|date=June 2022}} | |||

| ], the first alphabet used to transcribe the ] language.]] | |||

| Apart from military expeditions against Slavs, the re-Hellenization process involved (often forcible) transfer of peoples. Many Slavs were moved to other parts of the empire, such as Anatolia and made to serve in the military. In return, Greek-speakers were brought to the Balkans, to increase the number of defenders at the Emperor's disposal and dilute the concentration of Slavs. Even non-Greeks were transferred to the Balkans, such as Armenians.<ref name="Curta 2006"/> As more of the peripheral territories of the Byzantine Empire were lost, their Greek-speakers made their own way back to Greece, e.g. from ] and Asia Minor. | |||

| Eventually, the Byzantines recovered the imperial border north all the way to today's region of Macedonia (which would serve as the northern border of the Byzantine world until 1018), although independent Slavic villages remained. As the Slavs supposedly occupied the entire Balkan interior, Constantinople was effectively cut off from the Dalmatian cities under its (nominal) control. Thus Dalmatia came to have closer ties with Italy, because of ability to maintain contact by sea (however, this too, was troubled by Slavic pirates). Additionally, Constantinople was cut off from Rome. This contributed to the growing cultural and political separation between the two centres of European Christendom. | |||

| Control of the Slavic tribes was nominal, as they retained their own culture and language. However, the Slavic tribes of Macedonia never formed their own empire or "state", and the area often switched between Greek, Bulgarian, Serbian and temporarily even Norman control. The Byzantines were unable to completely Hellenize Macedonia because their progress north was blocked by the Bulgarian Empire, and later by the Serbian Kingdom, which were both Slavic states. However, Byzantine culture nonetheless flowed further north, seen to this day as Bulgaria, Macedonia, and Serbia are part of the Orthodox world. Even in Dalmatia, where Byzantine influence was supplanted by Venice and Rome, the influence of Byzantine culture persists. | |||

| ===Formations of early Slavic states=== | |||

| By the end of 7th century, the Slavs occupied most parts of the Balkans. Despite having taken much land from the Byzantines, and successfully revolted against Avar dominance, they remained split into many different tribes. Other invaders of the Roman Empire, such as the ] in the west, for example, formed a somewhat unified Kingdom incorporating various 'Frankish' and other Germanic tribes. However, as noted earlier, the Slavs tended to dislike centralized rule, and there was no one king or warrior who could forge a unified kingdom or supra-tribal union (which otherwise would have spanned half of Europe). | |||

| ]'s ] arrived in ] in 680. Either by subjugation or alliance, they gained the service of Slavic tribes living in the area (as the Avars had done earlier). They moved the ''Severi'' and the "Seven Slavic clans" to defend strategic areas of their early Khanate. The Byzantines were aware of this new threat, but could not stop the formation of the ] by 681. As the Bulgars expanded their influence, many Slavic tribes in Thrace, Moesia, Macedonia and Dacia also joined the 'Bulgar League', which was becoming progressively Slavonicized. Others are noted to have been loyal to the Byzantines. As they spread northwest, they subjugated the ''Abordrites'' and ''Timochans'', who rebelled and appealed to the Franks for help. | |||

| ] | |||

| In the western Balkans, the tribal configurations of the 600s eventually formed a basis for early statelets, no doubt influenced by Feudalism from the west. During the 700s, the Franks extended into the northwestern Balkans. In 745, they incorporated the ] of ], the area serving as a march. The Slavs in northern ] (north of the Drava) were included in the ], given by the Franks to an exiled Prince from Nitra, whereas those south of the Drava were part of 'Savia', a territory we know little about. The Franks and Bulgars fought for control over it initially, later becoming an area of conflict between ] and ]. | |||

| The ] were Frankish vassals until they successfully rebelled during the 850s, forming the ] in northern Dalmatia. In the southern half of the Dalmatian coast, four small Slavic duchies arose (i.e. ], ], ] and ]). Inland to these was the land of ]. Today there is much debate about 'historical rights' to certain areas. However, these early states were composed of ethnically very similar people split into different tribal territories. At times, one would grow powerful enough to exert influence over its neighbours. Centuries later, some tribal or regional designations evolved to identify a people with a common national awareness (i.e. a nation-state), somewhat distinct from its neighbours. As the tribes and early states were never unified, they experienced different histories and cultural influences which has coloured their identity today. One cannot deny their uniqueness, but should not overlook their common origins either. | |||

| ==Genetics== | ==Genetics== | ||

| {{See also|Slavs#Genetics}} | |||

| Although referred to as 'Slavs' and speaking a ], modern South Slavic peoples' genetic roots actually stem from a wide variety of ] backgrounds, attesting the complexity of the ethno-genetic processes in ]. A recent genetic study<ref></ref> researched several Slavic populations with the aim of localizing the ] homeland. A significant finding of this study is that two genetically distinct groups of Slavic populations exist. The first group encompassed most Slavic populations except most Southern Slavs. According to the authors, most Slavs share a high frequency of ]. Its origin is purported to trace to the middle ] basin of ] and spread via migrating males during the ] 15 ].<ref>Ibid, p. 408.</ref> The second group comprises most southern Slavic populations: ], most of the ], ], ] and ], who have a significantly lower frequency of R1a (~15%). According to the authors, this phenomenon is explained by "...contribution to the ]s of peoples who settled in the ] region before the Slavic expansion to the genetic heritage of Southern Slavs..."<ref>Ibid, p. 410.</ref> On the other hand the ] I2a1 of ] is typical of western South Slavs, especially Dalmatian ]s and ] (45-50%), with high frequency in all South Slavs (>20%).<ref>Pericic et al.</ref> The highest frequency and diversity of Subclade I2a1 among populations of the Western Balkans lends support to the hypothesis that the ] region of modern-day Croatia served as a refuge for populations bearing Haplogroup I2 during the ]. The subclade divergence appears to have arisen in the last one thousand to five thousand years.<ref>Y-DNA Haplogroup I and its Subclades - 2008.</ref> The Y haplogroup ] and especially the E-V13 clade is common on the ] and some parts of Italy. High frequencies of it (>20%) have been found amongst ], ], ], and ].<ref>{{Harvcoltxt|Cruciani et al.|2004}}</ref><ref>{{Harvcoltxt|Rosser et al.|2000}}</ref><ref>{{Harvcoltxt|King et al.|2008}}</ref> Phylogenetic analysis strongly suggest that these lineages have spread through Europe, from the Balkans in a "rapid demographic expansion".<ref>{{Harvcoltxt|Cruciani et al.|2007}}</ref> E-V13 is in any case generally described in ] as one of the components, which shows the contribution made by the populations who dispersed the Neolithic technology from the Middle East trough Europe.<ref>{{Harvcoltxt|Semino et al.|2000}}</ref><ref>{{Harvcoltxt|King and Underhill|2002}}</ref><ref>{{Harvcoltxt|Underhill|2002}}</ref> Also the ] gene pools of the Slavonic ethnic groups proved to preserve features suggesting a common ancestor for these and South European populations (especially those of the ]).<ref>Differentiation and Genetic Position of Slavs among Eurasian Ethnic Groups as Inferred from Variation in Mitochondrial DNA - B. A. Malyarchuk, Russian Journal of Genetics. Volume 37, Number 12, December, 2001.</ref> Finally the testing results suggest a common ancestry of all Balkan populations, with a lack of correlation between genetic differentiation and language or ethnicity, stressing that no major migration barriers have existed in the making of the complex ] human puzzle.<ref></ref><ref></ref> The genetic homogeneity among ] populations suggests either a ] of all southeastern European populations or strong ] between them, which eliminated any initial differences. Taking into account that the region has had a relatively high population density since the ] period and that this region represents a crossroads of routes connecting the cultural centers of ] with different European areas.<ref></ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| [[File:A genetic atlas of human admixture history - East Europe II and Mediterranean.png|thumb|Autosomal analysis presenting the historical contribution of different donor groups in some European populations. Polish sample was selected to represent the Slavic influence, and it is suggesting a strong and early impact in Greece (30-37%), Romania (48-57%), Bulgaria (55-59%), and Hungary (54-84%).<ref>{{cite web |work=A genetic atlas of human admixture history |title=Companion website for "A genetic atlas of human admixture history", Hellenthal et al, Science (2014) |url=http://admixturemap.paintmychromosomes.com/ |access-date=10 December 2020 |archive-date=2 September 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190902195508/http://admixturemap.paintmychromosomes.com/ |url-status=live }}<br> | |||

| {{cite journal |last1=Hellenthal |first1=Garrett |last2=Busby |first2=George B.J. |last3=Band |first3=Gavin |last4=Wilson |first4=James F. |last5=Capelli |first5=Cristian |last6=Falush |first6=Daniel |last7=Myers |first7=Simon |title=A Genetic Atlas of Human Admixture History |journal=] |date=14 February 2014 |volume=343 |issue=6172 |pages=747–751 |doi=10.1126/science.1243518 |pmid=24531965 |issn=0036-8075|pmc=4209567 |bibcode=2014Sci...343..747H }}<br> {{cite journal |title=Supplementary Material for "A genetic atlas of human admixture history" |journal = Science|volume = 343|issue = 6172|pages=747–751 |quote=S7.6 "East Europe": The difference between the 'East Europe I' and 'East Europe II' analyses is that the latter analysis included the Polish as a potential donor population. The Polish were included in this analysis to reflect a Slavic language speaking source group." "We speculate that the second event seen in our six Eastern Europe populations between northern European and southern European ancestral sources may correspond to the expansion of Slavic language speaking groups (commonly referred to as the Slavic expansion) across this region at a similar time, perhaps related to displacement caused by the Eurasian steppe invaders (38; 58). Under this scenario, the northerly source in the second event might represent DNA from Slavic-speaking migrants (sampled Slavic-speaking groups are excluded from being donors in the EastEurope I analysis). To test consistency with this, we repainted these populations adding the Polish as a single Slavic-speaking donor group (“East Europe II” analysis; see Note S7.6) and, in doing so, they largely replaced the original North European component (Figure S21), although we note that two nearby populations, Belarus and Lithuania, are equally often inferred as sources in our original analysis (Table S12). Outside these six populations, an admixture event at the same time (910CE, 95% CI:720-1140CE) is seen in the southerly neighboring Greeks, between sources represented by multiple neighboring Mediterranean peoples (63%) and the Polish (37%), suggesting a strong and early impact of the Slavic expansions in Greece, a subject of recent debate (37). These shared signals we find across East European groups could explain a recent observation of an excess of IBD sharing among similar groups, including Greece, that was dated to a wide range between 1,000 and 2,000 years ago (37)|pmc = 4209567|year = 2014|last1 = Hellenthal|first1 = G.|last2 = Busby|first2 = G. B.|last3 = Band|first3 = G.|last4 = Wilson|first4 = J. F.|last5 = Capelli|first5 = C.|last6 = Falush|first6 = D.|last7 = Myers|first7 = S.|pmid = 24531965|doi = 10.1126/science.1243518| bibcode=2014Sci...343..747H }}</ref>]] | |||

| According to the 2013 ] ] survey "of recent genealogical ancestry over the past 3,000 years at a continental scale", the speakers of Serbo-Croatian language share a very high number of common ancestors dated to the ] approximately 1,500 years ago with Poland and Romania-Bulgaria cluster among others in Eastern Europe. It is concluded to be caused by the ] and Slavic expansion, which was a "relatively small population that expanded over a large geographic area", particularly "the expansion of the Slavic populations into regions of low population density beginning in the sixth century" and that it is "highly coincident with the modern distribution of Slavic languages".<ref name="Ralph2013">{{cite journal |author=P. Ralph |title=The Geography of Recent Genetic Ancestry across Europe |journal=] |volume=11 |issue=5 |year=2013 |doi=10.1371/journal.pbio.1001555 |pages=e105090 |pmid=23667324 |pmc=3646727 |display-authors=etal |doi-access=free }}</ref> According to Kushniarevich et al. 2015, the Hellenthal et al. 2014 IBD analysis also found "multi-directional admixture events among East Europeans (both Slavic and non-Slavic), dated to around 1,000–1,600 YBP" which coincides with "the proposed time-frame for the Slavic expansion".<ref name="Kushniarevich2015">{{cite journal |author=A. Kushniarevich |year=2015 |title=Genetic Heritage of the Balto-Slavic Speaking Populations: A Synthesis of Autosomal, Mitochondrial and Y-Chromosomal Data |journal=] |volume=10 |issue=9 |pages=e0135820 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0135820 |pmid=26332464|pmc=4558026|bibcode=2015PLoSO..1035820K |display-authors=etal|doi-access=free }}</ref> The Slavic influence is "dated to 500-900 CE or a bit later with over 40-50% among Bulgarians, Romanians, and Hungarians".<ref name="Ralph2013"/> The 2015 IBD analysis found that the South Slavs have lower proximity to Greeks than with East and West Slavs and that there's an "even patterns of IBD sharing among East-West Slavs–'inter-Slavic' populations (], ] and ])–and South Slavs, i.e. across an area of assumed historic movements of people including Slavs". The slight peak of shared IBD segments between South and East-West Slavs suggests a shared "Slavonic-time ancestry".<ref name="Kushniarevich2015"/> The 2014 IBD analysis comparison of Western Balkan and Middle Eastern populations also found negligible gene flow between 16th and 19th century during the ] of the Balkans.<ref name="Kovacevic2014">{{cite journal|author=L. Kovačević|title=Standing at the Gateway to Europe - The Genetic Structure of Western Balkan Populations Based on Autosomal and Haploid Markers|journal=]|volume=9|issue=8|year=2014|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0105090|pages=e105090|pmid=25148043|pmc=4141785|bibcode=2014PLoSO...9j5090K|display-authors=etal|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| ==South Slavic peoples== | |||

| South Slavs are divided along linguistic lines into two groups — eastern and western. Please note that some of the subdivisions of the South Slavic ethnicities remain debatable, particularly for smaller groups and national minorities in former Yugoslavia. | |||

| According to a 2014 ] analysis of Western Balkan, the South Slavs show a genetic uniformity. Bosnians and Croatians were closer to East European populations and largely overlapped with Hungarians from Central Europe.<ref name="Kovacevic2014"/> In the 2015 analysis, Bosnians and Croatians formed a western South Slavic cluster together with Slovenians, in opposition to an eastern cluster formed by Macedonians and Bulgarians, with Serbians in between the two. The western cluster has an inclination toward Hungarians, Czechs, and Slovaks, while the eastern ones lean toward Romanians and, to some extent, to Greeks.<ref name="Kushniarevich2015"/> The modeled ancestral genetic component of Balto-Slavs among South Slavs was between 55 and 70%.<ref name="Kushniarevich2015"/> In the 2018 analysis of Slovenian population, the Slovenian population clustered with Croatians, Hungarians and was close to Czech.<ref name="Delser2018">{{cite journal |author=P. M. Delser |title=Genetic Landscape of Slovenians: Past Admixture and Natural Selection Pattern|journal=Frontiers in Genetics |volume=9 |pages=551 |year=2018 |doi=10.3389/fgene.2018.00551 |pmid=30510563 |pmc=6252347 |display-authors=etal|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| List of the South Slavic peoples and ethnic groups, including population figures:<ref>Mile Nedeljković. ''Leksikon naroda Sveta''. Beograd, 2001.</ref> | |||

| The 2006 Y-DNA study results "suggest that the Slavic expansion started from the territory of present-day Ukraine, thus supporting the hypothesis that places the earliest known homeland of Slavs in the basin of the middle ]".<ref name="Rębała ''et al.'' 2007">{{cite journal | pmid = 17364156 | year = 2007 | last1 = Rebała | first1 = K | last2 = Mikulich | first2 = AI | last3 = Tsybovsky | first3 = IS | last4 = Siváková | first4 = D | last5 = Dzupinková | first5 = Z | last6 = Szczerkowska-Dobosz | first6 = A | last7 = Szczerkowska | first7 = Z | title = Y-STR variation among Slavs: Evidence for the Slavic homeland in the middle Dnieper basin | volume = 52 | issue = 5 | pages = 406–14 | doi = 10.1007/s10038-007-0125-6 | journal = Journal of Human Genetics | doi-access = free }}</ref> According to genetic studies until 2020, the distribution, variance and frequency of the ] ] and ] and their subclades R-M558, R-M458 and I-CTS10228 among South Slavs are in correlation with the spreading of Slavic languages during the medieval Slavic expansion from Eastern Europe, most probably from the territory of present-day ] and ].<ref>{{cite journal|author=A. Zupan|title=The paternal perspective of the Slovenian population and its relationship with other populations|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/251567977|journal=]|volume=40|issue=6|date=2013|doi=10.3109/03014460.2013.813584|pmid=23879710|display-authors=etal|pages=515–526 |s2cid=34621779|quote=However, a study by Battaglia et al. (2009) showed a variance peak for I2a1 in the Ukraine and, based on the observed pattern of variation, it could be suggested that at least part of the I2a1 haplogroup could have arrived in the Balkans and Slovenia with the Slavic migrations from a homeland in present-day Ukraine... The calculated age of this specific haplogroup together with the variation peak detected in the suggested Slavic homeland could represent a signal of Slavic migration arising from medieval Slavic expansions. However, the strong genetic barrier around the area of Bosnia and Herzegovina, associated with the high frequency of the I2a1b-M423 haplogroup, could also be a consequence of a Paleolithic genetic signal of a Balkan refuge area, followed by mixing with a medieval Slavic signal from modern-day Ukraine.}}</ref><ref>{{Citation |last1=Underhill |first1=Peter A. |year=2015 |title=The phylogenetic and geographic structure of Y-chromosome haplogroup R1a |journal=European Journal of Human Genetics |volume=23 |issue=1 |pages=124–131 |doi=10.1038/ejhg.2014.50 |pmid=24667786 |pmc=4266736 |quote=R1a-M458 exceeds 20% in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland, and Western Belarus. The lineage averages 11–15% across Russia and Ukraine and occurs at 7% or less elsewhere (Figure 2d). Unlike hg R1a-M458, the R1a-M558 clade is also common in the Volga-Uralic populations. R1a-M558 occurs at 10–33% in parts of Russia, exceeds 26% in Poland and Western Belarus, and varies between 10 and 23% in the Ukraine, whereas it drops 10-fold lower in Western Europe. In general, both R1a-M458 and R1a-M558 occur at low but informative frequencies in Balkan populations with known Slavonic heritage.}}</ref><ref name="Utevska">{{cite thesis |type=PhD |author=O.M. Utevska |date=2017 |title=Генофонд українців за різними системами генетичних маркерів: походження і місце на європейському генетичному просторі |trans-title=The gene pool of Ukrainians revealed by different systems of genetic markers: the origin and statement in Europe |publisher=National Research Center for Radiation Medicine of ] |url=http://nrcrm.gov.ua/science/councils/dissertation/ |language=uk |pages=219–226, 302 |access-date=10 December 2020 |archive-date=17 July 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200717170217/http://nrcrm.gov.ua/science/councils/dissertation/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Neparaczki">{{cite journal |last1=Neparáczki |first1=Endre |last2=Maróti |first2=Zoltán |display-authors=1 |date=2019 |title=Y-chromosome haplogroups from Hun, Avar and conquering Hungarian period nomadic people of the Carpathian Basin |journal=] |publisher=] |volume=9 |issue=16569 |page=16569 |doi=10.1038/s41598-019-53105-5 |pmc=6851379 |pmid=31719606 |bibcode=2019NatSR...916569N |quote=Hg I2a1a2b-L621 was present in 5 Conqueror samples, and a 6th sample form Magyarhomorog (MH/9) most likely also belongs here, as MH/9 is a likely kin of MH/16 (see below). This Hg of European origin is most prominent in the Balkans and Eastern Europe, especially among Slavic speaking groups.}}</ref><ref name="HorolmaTibor2019">{{cite book|first1=Horolma|last1=Pamjav|first2=Tibor|last2=Fehér|first3=Endre|last3=Németh|first4=László|last4=Koppány Csáji|title=Genetika és őstörténet|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xq2xDwAAQBAJ|year=2019|publisher=Napkút Kiadó|language=hu|isbn=978-963-263-855-3|pages=58|quote=Az I2-CTS10228 (köznevén „dinári-kárpáti") alcsoport legkorábbi közös őse 2200 évvel ezelőttre tehető, így esetében nem arról van szó, hogy a mezolit népesség Kelet-Európában ilyen mértékben fennmaradt volna, hanem arról, hogy egy, a mezolit csoportoktól származó szűk család az európai vaskorban sikeresen integrálódott egy olyan társadalomba, amely hamarosan erőteljes demográfiai expanzióba kezdett. Ez is mutatja, hogy nem feltétlenül népek, mintsem családok sikerével, nemzetségek elterjedésével is számolnunk kell, és ezt a jelenlegi etnikai identitással összefüggésbe hozni lehetetlen. A csoport elterjedése alapján valószínűsíthető, hogy a szláv népek migrációjában vett részt, így válva az R1a-t követően a második legdominánsabb csoporttá a mai Kelet-Európában. Nyugat-Európából viszont teljes mértékben hiányzik, kivéve a kora középkorban szláv nyelvet beszélő keletnémet területeket.|access-date=12 December 2020|archive-date=27 September 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230927203723/https://books.google.com/books?id=xq2xDwAAQBAJ|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="Fóthi">{{Citation |last1=Fóthi |first1=E. |last2=Gonzalez |first2=A. |last3=Fehér |first3=T. |display-authors=etal |title=Genetic analysis of male Hungarian Conquerors: European and Asian paternal lineages of the conquering Hungarian tribes |journal=Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences |volume=12 |issue=1 |date=2020 |page=31 |doi=10.1007/s12520-019-00996-0|doi-access=free|bibcode=2020ArAnS..12...31F |quote=Based on SNP analysis, the CTS10228 group is 2200 ± 300 years old. The group’s demographic expansion may have begun in Southeast Poland around that time, as carriers of the oldest subgroup are found there today. The group cannot solely be tied to the Slavs, because the proto-Slavic period was later, around 300–500 CE... The SNP-based age of the Eastern European CTS10228 branch is 2200 ± 300 years old. The carriers of the most ancient subgroup live in Southeast Poland, and it is likely that the rapid demographic expansion which brought the marker to other regions in Europe began there. The largest demographic explosion occurred in the Balkans, where the subgroup is dominant in 50.5% of Croatians, 30.1% of Serbs, 31.4% of Montenegrins, and in about 20% of Albanians and Greeks. As a result, this subgroup is often called Dinaric. It is interesting that while it is dominant among modern Balkan peoples, this subgroup has not been present yet during the Roman period, as it is almost absent in Italy as well (see Online Resource 5; ESM_5).}}</ref><ref name="Kassian2020">{{citation |last1=Kushniarevich |first1=Alena |last2=Kassian |first2=Alexei |editor=Marc L. Greenberg |date=2020 |title=Encyclopedia of Slavic Languages and Linguistics Online |chapter=Genetics and Slavic languages |publisher=Brill |doi=10.1163/2589-6229_ESLO_COM_032367 |access-date=10 December 2020 |chapter-url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341945550 |quote=The geographic distributions of the major eastern European NRY haplogroups (R1a-Z282, I2a-P37) overlap with the area occupied by the present-day Slavs to a great extent, and it might be tempting to consider both haplogroups as Slavic-specic patrilineal lineages}}</ref> | |||

| Eastern group:(15,000,000 estimated all together) | |||

| *] = 8,000,000 (12,000,000 estimated all together) | |||

| **] (]) = 250,000 | |||

| **] = 140,000 | |||

| **] (]) = 15,000 | |||

| *] = 2,000,000 (3,000,000 estimated all together) | |||

| **] = 40,000 | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| Western group:(25,570,000 estimated all together) | |||

| * ] | |||

| *] = 8,000,000 (13,000,000 estimated all together) | |||

| * ] | |||

| *] = 4,650,000 (7,500,000 estimated all together) | |||

| * ] | |||

| **] = 50,000 | |||

| * ] | |||

| **] = 10,000 | |||

| * ] | |||

| **] = 5,000 | |||

| **] = 5,000 | |||

| **] = 80,000 | |||

| **] = 2,000 | |||

| *] = 2,000,000 | |||

| *] = 64,000 | |||

| *] = 1,800,000 (2,500,000 estimated all together) | |||

| **] = 1,500 (5,000 estimated all together) | |||

| *] = 300,000 (1,000,000 estimated all together) | |||

| ==Annotations== | |||

| Ethnic designations among both eastern and western groups include: | |||

| {{Cnote2 Begin|liststyle=upper-alpha}} | |||

| *] | |||