| Revision as of 09:29, 6 March 2024 editSafetyDance151 (talk | contribs)6 editsm Removed obvious vandalism: spurious references to, and photo of, Australian Rules footballer Tom Cole in the introduction to this articleTag: Reverted← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 08:37, 4 December 2024 edit undoCitation bot (talk | contribs)Bots5,408,023 edits Altered issn. Added date. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Spinixster | Category:Traditional children's songs | #UCB_Category 184/198 | ||

| (12 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{about|the English nursery rhyme|the film|Old King Cole (film)|other uses|King Cole (disambiguation)}} | {{about|the English nursery rhyme|the film|Old King Cole (film)|other uses|King Cole (disambiguation)}} | ||

| {{short description|British nursery rhyme}} | {{short description|British nursery rhyme}} | ||

| {{More citations needed|date=July 2016}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2016}} | {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2016}} | ||

| {{Infobox song | |||

| ⚫ | "'''Old King Cole'''" is a British ] first attested in |

||

| | name = Old King Cole | |||

| | cover = Old King Cole 2 - WW Denslow - Project Gutenberg etext 18546.jpg | |||

| | caption = Illustration by ] | |||

| | type = nursery | |||

| | published = 1709 | |||

| | writer = Traditional | |||

| }} | |||

| ⚫ | "'''Old King Cole'''" is a British ] first attested in 1709. Though there is much speculation about the identity of King Cole, it is unlikely that he can be identified reliably as any historical figure. It has a ] number of 1164. The poem describes a merry king who called for his pipe, bowl, and musicians, with the details varying among versions. | ||

| The "bowl" is a drinking vessel, while it is unclear whether the "pipe" is a ] or a ].{{citation needed|date=July 2020|reason=Need solid sources for this. OED proves nothing.}} | The "bowl" is a drinking vessel, while it is unclear whether the "pipe" is a ] or a ].{{citation needed|date=July 2020|reason=Need solid sources for this. OED proves nothing.}} | ||

| Line 20: | Line 28: | ||

| With King Cole and his fiddlers three.<ref name=Opie/></poem></blockquote> | With King Cole and his fiddlers three.<ref name=Opie/></poem></blockquote> | ||

| The song is first attested in ]'s ''Useful Transactions in Philosophy'' in |

The song is first attested in ]'s ''Useful Transactions in Philosophy'' for January and February 1709.<ref>{{cite journal|first=William|last=King|author-link=William King (poet)|title=The Art of Writing Unintelligibly|journal=Useful Transactions in Philosophy|publication-place=London|publisher=Bernard Lintott|date=January–February 1709|url=https://archive.org/details/s1id11857700/page/n63|pages=52–53}}</ref><ref name="Opie">I. Opie and P. Opie, ''The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes'' (Oxford University Press, 1997), pp. 156–8.</ref> King's version has the following lyrics: | ||

| King's version has the following lyrics: | |||

| <blockquote><poem> | <blockquote><poem> | ||

| Good King Cole, | :Good King Cole, | ||

| And he call'd for his Bowle, | And he call'd for his Bowle, | ||

| And he call'd for |

And he call'd for Fidlers three; | ||

| And there was Fiddle |

And there was Fiddle Fiddle, | ||

| And twice Fiddle |

And twice Fiddle Fiddle, | ||

| For 'twas my Lady's Birth-day, | For 'twas my Lady's Birth-day, | ||

| Therefore we keep Holy-day | Therefore we keep Holy-day, | ||

| And come to be merry.<ref name="Opie"/></poem></blockquote> | And come to be merry.<ref name="Opie"/></poem></blockquote> | ||

| Line 43: | Line 49: | ||

| It is often noted that the name of the legendary Welsh king ] can be translated 'Old Cole' or 'Old King Cole'.<ref>Alistair Moffat, ''The Borders: A History of the Borders from Earliest Times'', {{ISBN|1841584665}} (unpaginated)</ref><ref>Anthony Richard Birley, ''The People of Roman Britain'', {{ISBN|0520041194}}, p. 160</ref> This sometimes leads to speculation that he, or some other Coel in ], is the model for Old King Cole of the nursery rhyme.<ref>Albert Jack, ''Pop Goes the Weasel: The Secret Meanings of Nursery Rhymes'', {{ISBN|0399535551}}, ''s.v.'' 'Old King Cole'</ref> However, there is no documentation of a connection between the fourth-century figures and the eighteenth-century nursery rhyme. There is also a dubious connection of Old King Cole to Cornwall and King Arthur found at ] that there was a Cornish King or Lord Coel.{{citation needed|date=July 2018}} | It is often noted that the name of the legendary Welsh king ] can be translated 'Old Cole' or 'Old King Cole'.<ref>Alistair Moffat, ''The Borders: A History of the Borders from Earliest Times'', {{ISBN|1841584665}} (unpaginated)</ref><ref>Anthony Richard Birley, ''The People of Roman Britain'', {{ISBN|0520041194}}, p. 160</ref> This sometimes leads to speculation that he, or some other Coel in ], is the model for Old King Cole of the nursery rhyme.<ref>Albert Jack, ''Pop Goes the Weasel: The Secret Meanings of Nursery Rhymes'', {{ISBN|0399535551}}, ''s.v.'' 'Old King Cole'</ref> However, there is no documentation of a connection between the fourth-century figures and the eighteenth-century nursery rhyme. There is also a dubious connection of Old King Cole to Cornwall and King Arthur found at ] that there was a Cornish King or Lord Coel.{{citation needed|date=July 2018}} | ||

| Further speculation connects Old King Cole and thus Coel Hen to ], but in fact Colchester was not named after Coel Hen.<ref> |

Further speculation connects Old King Cole and thus Coel Hen to ], but in fact Colchester was not named after Coel Hen.<ref>See Opie and Opie, and discussion at {{sectionlink|Colchester|Name}}</ref> Connecting with the musical theme of the nursery rhyme, according to a much later source, Coel Hen supposedly had a daughter who was skilled in music, according to ], writing in the 12th century.<ref name=Opie/> | ||

| <!-- NB the following passage is lifted verbatim from the article ]. The refs are either offline or don't devolve, thus we can't read them right now and so they can't be used in THIS article, and have been commented out.--> | <!-- NB the following passage is lifted verbatim from the article ]. The refs are either offline or don't devolve, thus we can't read them right now and so they can't be used in THIS article, and have been commented out.--> | ||

| A legend that King Coel of Colchester was the father of the Empress ], and therefore the grandfather of ], appeared in ]'s '']'' and ]'s '']''.<!--SEE ABOVE<ref>Henry of Huntingdon, ], ch. 37.</ref><ref>Greenway, pp. 60–61.</ref><ref name=GeoffreyCoel>Geoffrey of Monmouth, ], ch. 6.</ref>--> The passages are clearly related, even using some of the same words, but it is not clear which version was first. Henry appears to have written the relevant part of the ''Historia Anglorum'' before he knew about Geoffrey's work, leading ] and other scholars to conclude that Geoffrey borrowed the passage from Henry, rather than the other way around.<!--SEE ABOVE<ref name="Greenwayciv">Greenway, p. civ.</ref><ref>Harbus 2002, p. 76.</ref>--> The source of the claim is unknown, but may have predated both Henry and Geoffrey. ] proposes it came from a lost hagiography of Helena;<!--SEE ABOVE<ref name="Greenwayciv"/>--> Antonia Harbus suggests it came instead from oral tradition.<!--SEE ABOVE<ref>Harbus 2002, p. 77.</ref>-->{{citation needed|date=October 2020}} | A legend that King Coel of Colchester was the father of the Empress ], and therefore the grandfather of ], appeared in ]'s '']'' and ]'s '']''.<!--SEE ABOVE<ref>Henry of Huntingdon, ], ch. 37.</ref><ref>Greenway, pp. 60–61.</ref><ref name=GeoffreyCoel>Geoffrey of Monmouth, ], ch. 6.</ref>--> The passages are clearly related, even using some of the same words, but it is not clear which version was first. Henry appears to have written the relevant part of the ''Historia Anglorum'' before he knew about Geoffrey's work, leading ] and other scholars to conclude that Geoffrey borrowed the passage from Henry, rather than the other way around.<!--SEE ABOVE<ref name="Greenwayciv">Greenway, p. civ.</ref><ref>Harbus 2002, p. 76.</ref>--> The source of the claim is unknown, but may have predated both Henry and Geoffrey. ] proposes it came from a lost hagiography of Helena;<!--SEE ABOVE<ref name="Greenwayciv"/>--> Antonia Harbus suggests it came instead from oral tradition.<!--SEE ABOVE<ref>Harbus 2002, p. 77.</ref>-->{{citation needed|date=October 2020}} | ||

| ===Cole |

==="Old Cole" theory=== | ||

| In the 19th century ], an expert on popular music, suggested |

In the 19th century ], an expert on popular music, suggested that "Old King Cole" was probably derived from "Old Cole", a nickname that was used many times in ], though its meaning is now unclear.<ref>{{cite book | first=William | last=Chappell | author-link=William Chappell (writer) | chapter=Old King Cole | title=The Ballad Literature and Popular Music of the Olden Time | date=1859 | volume=2 | publication-place=London | publisher=Chappell and Co. | chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/bib_fict_4117314_2/page/632 | pages=633–635 }}</ref> | ||

| "Old Cole" probably originated from ]'s ''Pleasant History of Thomas of Reading'' (c. 1598),<ref name=Opie/> about Thomas Cole, a fictional ] during the reign of ] from ], who was known as Old Cole throughout the book.<ref>{{cite journal | first=W. Carew | last=Hazlitt | title=Notes on Popular Antiquities | journal=The Antiquary | date=May 1886 | number=77 | volume=13 | publication-place=London | publisher=Elliot Stock | url=https://archive.org/details/antiquary12unkngoog/page/n246 | page=218 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | last=Powys | first=Llewelyn | title=Thomas Deloney | journal=The Virginia Quarterly Review | publisher=University of Virginia | volume=9 | issue=4 | year=1933 | issn=0042-675X | jstor=26433739 | pages=591–594 | url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/26433739 }}</ref> In the story, Cole became extremely weathly, but was killed by an innkeeper at ]<ref>{{cite book | first1=John | last1=Ayto | first2=Ian | last2=Crofton | section=Thomas of Reading | title=Brewers Britain and Ireland | publisher=Weidenfeld & Nicolson | year=2005 | section-url=https://archive.org/details/brewersbritainir0000unse/page/914 | page=914 }}</ref> who disposed of Cole's body in the ] river – the story concludes with the lines "And some say, that the river whereinto Cole was cast, did ever since carry the name of Cole, being called The river of Cole, and the Towne of Colebrooke".<ref>{{cite book | first=Thomas | last=Deloney | author-link=Thomas Deloney | chapter=Chapter 11 | title=Thomas of Reading: or, The Sixe Worthie Yeomen of the West | publisher=Robert Bird | publication-place=London | edition=6 | year=1632 | url=https://archive.org/details/thomasofreadingo00delo/page/n62/mode/2up?q=%22thomas+cole%22 | chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/thomasofreadingo00delo/page/n101 }}</ref> | |||

| == "Old King Coal" == | == "Old King Coal" == | ||

| In political cartoons and similar material, especially in Great Britain, sometimes Old King "Coal" (note the spelling difference) has been used to symbolize the ]. One such instance is the folk song "Old King Coal" (different than "Old King Cole |

In political cartoons and similar material, especially in Great Britain, sometimes Old King "Coal" (note the spelling difference) has been used to symbolize the ]. One such instance is the folk song "Old King Coal" (different than "Old King Cole", Roud 1164), which was written by English folk musician ] in 1994. It presents Old King Coal as "a kind of modernization of ]", with the chorus being:<blockquote><poem> | ||

| There's fire in the heart of Old King Coal | There's fire in the heart of Old King Coal | ||

| There's the strength of centuries in his soul | There's the strength of centuries in his soul | ||

| There's a power that grows where his black blood flows | There's a power that grows where his black blood flows | ||

| So here's to Old King Coal |

So here's to Old King Coal<ref>{{Cite web |last=Spiegel |first=Max |title=Lyr Req: Old King Coal (from Dave Webber) |url=https://mudcat.org/thread.cfm?threadid=6560 |access-date=2023-08-11 |website=mudcat.org}}</ref></poem></blockquote> | ||

| ==Modern usage== | ==Modern usage== | ||

| ⚫ | "Old King Cole" is often referenced in popular culture. | ||

| {{reduce trivia|section|date=March 2017}} | |||

| ⚫ | King Cole is often referenced in popular culture. | ||

| ===In art=== | ===In art=== | ||

| Line 67: | Line 74: | ||

| ====As a marching cadence==== | ====As a marching cadence==== | ||

| The United States military has used versions<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TtyEUFhzxJs | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090309074452/http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TtyEUFhzxJs&feature=channel_page| archive-date=2009-03-09 | url-status=dead|title=U.S Army – Old King Cole |publisher=YouTube |date=10 February 2008 |access-date=15 July 2016}}</ref> of the ] in the form of ]s |

The United States military has used versions<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TtyEUFhzxJs | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090309074452/http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TtyEUFhzxJs&feature=channel_page| archive-date=2009-03-09 | url-status=dead|title=U.S Army – Old King Cole |publisher=YouTube |date=10 February 2008 |access-date=15 July 2016}}</ref> of the ] in the form of ]s since at least the 1920s. | ||

| ==== In music ==== | ==== In music ==== | ||

| "Old King Cole" was the subject of a 1923 one-act ballet by ]. | |||

| In 1960, a variation of the song was released on ] |

In 1960, a variation of the song was released on ] live album '']''. | ||

| The first four lines of |

The first four lines of "Old King Cole" are quoted in the song "]" by ] (from their third album, '']'', released in 1971). | ||

| The melody is also used in the song |

The melody is also used in the song "]" by ] on their eponymous debut album '']'' (1973), with the lyrics adapted to: | ||

| "Great King Rat was a dirty old man, | "Great King Rat was a dirty old man, | ||

| And a dirty old man was he, | And a dirty old man was he, | ||

| Line 84: | Line 91: | ||

| The jazz musician Nathaniel Coles took the name ]. | The jazz musician Nathaniel Coles took the name ]. | ||

| In the 2012 album Once Upon a Time (In Space) |

In the 2012 album '']'', "Old King Cole" is used as inspiration for both the lyrics and melody of the second track of the same name. | ||

| "Old Queen Cole" was the name of a song by |

"Old Queen Cole" was the name of a song by ] that appears on their album '']''; the title and lyrics suggest a reference to the nursery rhyme. | ||

| === In fiction === | === In fiction === | ||

| Line 92: | Line 99: | ||

| In his 1897 collection '']'', ] included a story explaining the background to the nursery rhyme. In this version, Cole is a donkey-riding ] who is selected at random to succeed the King of Whatland when the latter dies without heir. | In his 1897 collection '']'', ] included a story explaining the background to the nursery rhyme. In this version, Cole is a donkey-riding ] who is selected at random to succeed the King of Whatland when the latter dies without heir. | ||

| In ] '']'', the titular character tells her charges a story about how King Cole remembered that he was a merry old soul. | In ] '']'', the titular character tells her charges a story about how King Cole remembered that he was a merry old soul. | ||

| ] made reference to the rhyme in '']'' (619.27f): | ] made reference to the rhyme in '']'' (619.27f): | ||

| Line 98: | Line 105: | ||

| Joyce is also punning on the canonical hours ''{{lang|la|tierce}}'' (3), ''{{lang|la|sext}}'' (6), and ''{{lang|la|nones}}'' (9), in "Terce ... sixt ... none", and on ] and his ], in "fiddlers ... makmerriers ... Cole". | Joyce is also punning on the canonical hours ''{{lang|la|tierce}}'' (3), ''{{lang|la|sext}}'' (6), and ''{{lang|la|nones}}'' (9), in "Terce ... sixt ... none", and on ] and his ], in "fiddlers ... makmerriers ... Cole". | ||

| The Old King Cole theme appeared twice in |

The Old King Cole theme appeared twice in two cartoons released in 1933; ] made a '']'' cartoon, '']'', where the character holds a huge party where various ] characters are invited. ] produced an ] cartoon the same year, '']'', which references the nursery rhyme. | ||

| Old King Cole makes an appearance in the 1938 '']'' short film '']''. | Old King Cole makes an appearance in the 1938 '']'' short film '']''. | ||

| ]' 1948 short film ] features Larry, Moe and Shemp as musicians in King Cole's court who must stop an evil wizard from stealing the king's daughter. | ]' 1948 short film '']'' features Larry, Moe and Shemp as musicians in King Cole's court who must stop an evil wizard from stealing the king's daughter. | ||

| In the '']'' |

In the '']'' comic book series, King Cole is depicted as the long-time mayor of Fabletown. | ||

| In the fifteenth season of ] tabletop role-playing game show ] |

In the fifteenth season of ] tabletop role-playing game show '']'', Old King Cole is a character who was once the king of the kingdom of Jubilee. | ||

| ===In humour and satire=== | ===In humour and satire=== | ||

| Line 138: | Line 145: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

Latest revision as of 08:37, 4 December 2024

This article is about the English nursery rhyme. For the film, see Old King Cole (film). For other uses, see King Cole (disambiguation). British nursery rhyme

| "Old King Cole" | |

|---|---|

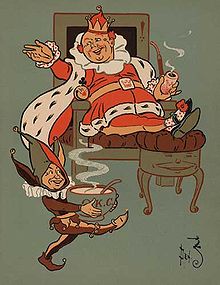

Illustration by William Wallace Denslow Illustration by William Wallace Denslow | |

| Nursery rhyme | |

| Published | 1709 |

| Songwriter(s) | Traditional |

"Old King Cole" is a British nursery rhyme first attested in 1709. Though there is much speculation about the identity of King Cole, it is unlikely that he can be identified reliably as any historical figure. It has a Roud Folk Song Index number of 1164. The poem describes a merry king who called for his pipe, bowl, and musicians, with the details varying among versions.

The "bowl" is a drinking vessel, while it is unclear whether the "pipe" is a musical instrument or a tobacco pipe.

Lyrics

The most common modern version of the rhyme is:

Old King Cole was a merry old soul,

And a merry old soul was he;

He called for his pipe, and he called for his bowl,

And he called for his fiddlers three.

Every fiddler he had a fiddle,

And a very fine fiddle had he;

Oh, there's none so rare, as can compare,

With King Cole and his fiddlers three.

The song is first attested in William King's Useful Transactions in Philosophy for January and February 1709. King's version has the following lyrics:

Good King Cole,

And he call'd for his Bowle,

And he call'd for Fidlers three;

And there was Fiddle Fiddle,

And twice Fiddle Fiddle,

For 'twas my Lady's Birth-day,

Therefore we keep Holy-day,

And come to be merry.

Identity of King Cole

There is much speculation about the identity of King Cole, but it is unlikely that he can be identified reliably given the centuries between the attestation of the rhyme and the putative identities; none of the extant theories is well supported.

William King mentions two possibilities: the "Prince that Built Colchester" and a 12th-century cloth merchant from Reading named Cole-brook. Sir Walter Scott thought that "Auld King Coul" was Cumhall, the father of the giant Fyn M'Coule (Finn McCool). Other modern sources suggest (without much justification) that he was Richard Cole (1568–1614) of Bucks in the parish of Woolfardisworthy on the north coast of Devon, whose monument and effigy survive in All Hallows Church, Woolfardisworthy.

Coel Hen theory

It is often noted that the name of the legendary Welsh king Coel Hen can be translated 'Old Cole' or 'Old King Cole'. This sometimes leads to speculation that he, or some other Coel in Roman Britain, is the model for Old King Cole of the nursery rhyme. However, there is no documentation of a connection between the fourth-century figures and the eighteenth-century nursery rhyme. There is also a dubious connection of Old King Cole to Cornwall and King Arthur found at Tintagel Castle that there was a Cornish King or Lord Coel.

Further speculation connects Old King Cole and thus Coel Hen to Colchester, but in fact Colchester was not named after Coel Hen. Connecting with the musical theme of the nursery rhyme, according to a much later source, Coel Hen supposedly had a daughter who was skilled in music, according to Geoffrey of Monmouth, writing in the 12th century.

A legend that King Coel of Colchester was the father of the Empress Saint Helena, and therefore the grandfather of Constantine the Great, appeared in Henry of Huntingdon's Historia Anglorum and Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae. The passages are clearly related, even using some of the same words, but it is not clear which version was first. Henry appears to have written the relevant part of the Historia Anglorum before he knew about Geoffrey's work, leading J. S. P. Tatlock and other scholars to conclude that Geoffrey borrowed the passage from Henry, rather than the other way around. The source of the claim is unknown, but may have predated both Henry and Geoffrey. Diana Greenway proposes it came from a lost hagiography of Helena; Antonia Harbus suggests it came instead from oral tradition.

"Old Cole" theory

In the 19th century William Chappell, an expert on popular music, suggested that "Old King Cole" was probably derived from "Old Cole", a nickname that was used many times in Elizabethan theatre, though its meaning is now unclear.

"Old Cole" probably originated from Thomas Deloney's Pleasant History of Thomas of Reading (c. 1598), about Thomas Cole, a fictional cloth merchant during the reign of Henry I from Reading, who was known as Old Cole throughout the book. In the story, Cole became extremely weathly, but was killed by an innkeeper at Colnbrook who disposed of Cole's body in the Colne Brook river – the story concludes with the lines "And some say, that the river whereinto Cole was cast, did ever since carry the name of Cole, being called The river of Cole, and the Towne of Colebrooke".

"Old King Coal"

In political cartoons and similar material, especially in Great Britain, sometimes Old King "Coal" (note the spelling difference) has been used to symbolize the coal industry. One such instance is the folk song "Old King Coal" (different than "Old King Cole", Roud 1164), which was written by English folk musician John Kirkpatrick in 1994. It presents Old King Coal as "a kind of modernization of John Barleycorn", with the chorus being:

There's fire in the heart of Old King Coal

There's the strength of centuries in his soul

There's a power that grows where his black blood flows

So here's to Old King Coal

Modern usage

"Old King Cole" is often referenced in popular culture.

In art

The Maxfield Parrish mural Old King Cole (1894) for the Mask and Wig Club was sold by Christie's for $662,500 in 1996. Parrish executed a second Old King Cole (1906) for The Knickerbocker Hotel, which was moved to the St. Regis New York in 1948, and is the centerpiece of its King Cole Bar.

As a marching cadence

The United States military has used versions of the traditional rhyme in the form of marching cadences since at least the 1920s.

In music

"Old King Cole" was the subject of a 1923 one-act ballet by Ralph Vaughan Williams.

In 1960, a variation of the song was released on Harry Belafonte's live album Belafonte Returns to Carnegie Hall.

The first four lines of "Old King Cole" are quoted in the song "The Musical Box" by Genesis (from their third album, Nursery Cryme, released in 1971).

The melody is also used in the song "Great King Rat" by Queen on their eponymous debut album Queen (1973), with the lyrics adapted to: "Great King Rat was a dirty old man, And a dirty old man was he, Now what did I tell you? Would you like to see?"

The jazz musician Nathaniel Coles took the name Nat King Cole.

In the 2012 album Once Upon a Time (In Space), "Old King Cole" is used as inspiration for both the lyrics and melody of the second track of the same name.

"Old Queen Cole" was the name of a song by Ween that appears on their album GodWeenSatan: The Oneness; the title and lyrics suggest a reference to the nursery rhyme.

In fiction

In his 1897 collection Mother Goose in Prose, L. Frank Baum included a story explaining the background to the nursery rhyme. In this version, Cole is a donkey-riding commoner who is selected at random to succeed the King of Whatland when the latter dies without heir.

In P. L. Travers' Mary Poppins Opens the Door, the titular character tells her charges a story about how King Cole remembered that he was a merry old soul.

James Joyce made reference to the rhyme in Finnegans Wake (619.27f):

With pipe on bowl. Terce for a fiddler, sixt for makmerriers, none for a Cole.

Joyce is also punning on the canonical hours tierce (3), sext (6), and nones (9), in "Terce ... sixt ... none", and on Fionn MacCool and his Fianna, in "fiddlers ... makmerriers ... Cole".

The Old King Cole theme appeared twice in two cartoons released in 1933; Walt Disney made a Silly Symphony cartoon, Old King Cole, where the character holds a huge party where various nursery rhyme characters are invited. Walter Lantz produced an Oswald cartoon the same year, The Merry Old Soul, which references the nursery rhyme.

Old King Cole makes an appearance in the 1938 Merrie Melodies short film Have You Got Any Castles.

The Three Stooges' 1948 short film Fiddlers Three features Larry, Moe and Shemp as musicians in King Cole's court who must stop an evil wizard from stealing the king's daughter.

In the Fables comic book series, King Cole is depicted as the long-time mayor of Fabletown.

In the fifteenth season of Dropout's tabletop role-playing game show Dimension 20, Old King Cole is a character who was once the king of the kingdom of Jubilee.

In humour and satire

G. K. Chesterton wrote a poem ("Old King Cole: A Parody") which presented the nursery rhyme successively in the styles of several poets: Alfred Lord Tennyson, W. B. Yeats, Robert Browning, Walt Whitman, and Algernon Charles Swinburne. Much later, Mad ran a feature similarly postulating classical writers' treatments of fairy tales. The magazine had Edgar Allan Poe tackle "Old King Cole", resulting in a cadence similar to that of "The Bells":

Old King Cole was a merry old soul

Old King Cole, Cole, Cole, Cole, Cole, Cole, Cole.

Notes

- ^ I. Opie and P. Opie, The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes (Oxford University Press, 1997), pp. 156–8.

- King, William (January–February 1709). "The Art of Writing Unintelligibly". Useful Transactions in Philosophy. London: Bernard Lintott: 52–53.

- North Devon and Exmoor Seascape Character Assessment, November 2015

- Alistair Moffat, The Borders: A History of the Borders from Earliest Times, ISBN 1841584665 (unpaginated)

- Anthony Richard Birley, The People of Roman Britain, ISBN 0520041194, p. 160

- Albert Jack, Pop Goes the Weasel: The Secret Meanings of Nursery Rhymes, ISBN 0399535551, s.v. 'Old King Cole'

- See Opie and Opie, and discussion at Colchester § Name

- Chappell, William (1859). "Old King Cole". The Ballad Literature and Popular Music of the Olden Time. Vol. 2. London: Chappell and Co. pp. 633–635.

- Hazlitt, W. Carew (May 1886). "Notes on Popular Antiquities". The Antiquary. 13 (77). London: Elliot Stock: 218.

- Powys, Llewelyn (1933). "Thomas Deloney". The Virginia Quarterly Review. 9 (4). University of Virginia: 591–594. ISSN 0042-675X. JSTOR 26433739.

- Ayto, John; Crofton, Ian (2005). "Thomas of Reading". Brewers Britain and Ireland. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 914.

- Deloney, Thomas (1632). "Chapter 11". Thomas of Reading: or, The Sixe Worthie Yeomen of the West (6 ed.). London: Robert Bird.

- Spiegel, Max. "Lyr Req: Old King Coal (from Dave Webber)". mudcat.org. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- "Important American Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture" christies.com (May 23, 1996); retrieved July 15, 2020

- "U.S Army – Old King Cole". YouTube. 10 February 2008. Archived from the original on 9 March 2009. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

References

- Geoffrey of Monmouth (c. 1136). History of the Kings of Britain.

- Henry of Huntingdon (c. 1129), Historia Anglorum.

- Kightley, C (1986), Folk Heroes of Britain. Thames & Hudson.

- Morris, John. The Age of Arthur: A History of the British Isles from 350 to 650. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1973. ISBN 978-0-684-13313-3.

- Opie, I & P (1951), The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes. Oxford University Press.

- Skene, WF (1868), The Four Ancient Books of Wales. Edmonston & Douglas.

- Legendary British kings

- Fictional kings

- Northern Brythonic monarchs

- English folklore

- 4th-century monarchs in Europe

- 3rd-century monarchs in Europe

- English folk songs

- English children's songs

- Traditional children's songs

- 1709 works

- 1709 in England

- English nursery rhymes

- Cumulative songs

- Songs about kings

- Songs about fictional male characters