| Revision as of 12:49, 27 March 2024 edit2a02:1810:363d:6700:c4a:380e:8c1:1a58 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 00:43, 8 December 2024 edit undoSausage Link of High Rule (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,680 edits Fixed the link | ||

| (28 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Category of positions in the philosophy of mind}} | {{Short description|Category of positions in the philosophy of mind}} | ||

| {{Refimprove|article|date=January 2018}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| '''Property dualism''' describes a category of positions in the ] which hold that, although the world is composed of just one kind of ]—]—there exist two distinct kinds of properties: ] and ]. In other words, it is the view that at least some non-physical, mental properties (such as thoughts, imagination and memories) exist in, or naturally ] upon, certain physical substances (namely ]). | '''Property dualism''' describes a category of positions in the ] which hold that, although the world is composed of just one kind of ]—]—there exist two distinct kinds of properties: ] and ]. In other words, it is the view that at least some non-physical, mental properties (such as thoughts, imagination and memories) exist in, or naturally ] upon, certain physical substances (namely ]). | ||

| ], on the other hand, is the view that there exist in the universe two fundamentally different kinds of substance: physical (]) and non-physical (] or ]), and subsequently also two kinds of properties which inhere in those respective substances. |

], on the other hand, is the view that there exist in the universe two fundamentally different kinds of substance: physical (]) and non-physical (] or ]), and subsequently also two kinds of properties which inhere in those respective substances. Both substance and property dualism are opposed to ]. Notable proponents of property dualism include ], ] and ].<ref>{{cite journal|author=Bratcher, Daniel|year=1999|title=David Chalmers' Arguments for Property Dualism|journal=Philosophy Today|url=https://www.pdcnet.org/philtoday/content/philtoday_1999_0043_0003_0292_0301?file_type=pdf|volume=43|issue=3|pages=292–301|doi=10.5840/philtoday199943319}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|author=Slagle, Jim|year=2015|title=Knowledge, Thought, and the Case for Dualism|journal=International Journal of Philosophical Studies |url=https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09672559.2015.1099972|volume=23|issue=5|pages=776–779|doi=10.1080/09672559.2015.1099972}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|author=Owen, Matthew|date=2018|title=Dusting Off Dualism?|url=https://blog.apaonline.org/2018/12/03/dusting-off-dualism/|website=American Philosophical Association|language=en-GB|archive-date=|archive-url=}}</ref> It became prominent in the final decades of the twentieth century and is now the leading alternative to physicalism.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Weir |first=Ralph Stefan |title=The mind-body problem and metaphysics: an argument from consciousness to mental substance |date=2024 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-032-45768-0 |series=Routledge studies in contemporary philosophy |location=New York (N.Y.) |pages=2–3}}</ref> | ||

| ] is viewed as a form of property dualism. | |||

| ==Non-reductive physicalism== | |||

| {{Main|Physicalism#Non-reductive_physicalism|l1=Non-reductive physicalism}} | |||

| ==Definition== | |||

| Non-reductive physicalism is the predominant contemporary form of property dualism according to which mental properties are mapped to ] properties, but are not ] to them. Non-reductive physicalism asserts that mind is not ontologically reducible to matter, in that an ontological distinction lies in the differences between the properties of mind and matter. It asserts that while mental states are physical in that they are caused by physical states, they are not ontologically reducible to physical states. No mental state is the same one thing as some physical state, nor is any mental state composed merely from physical states and phenomena. | |||

| Property dualism posits the existence of one material substance with essentially two different kinds of property: physical properties and mental properties.<ref name="Vintiadis 2019">{{Cite web|author=Vintiadis, Elly|date=2019|title=Property Dualism|url=https://press.rebus.community/intro-to-phil-of-mind/chapter/property-dualism/#footnote-67-1|website=Rebus Community|language=en-GB|archive-date=September 25, 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240925184911/https://press.rebus.community/intro-to-phil-of-mind/chapter/property-dualism/|url-status=live}}</ref> It argues that there are different kinds of properties that pertain to the only type of substance, the material substance: there are physical properties such as having colour or shape and there are mental properties like having certain beliefs or perceptions.<ref name="Vintiadis 2019"/> | |||

| ==Emergent materialism== | |||

| {{main|Emergent materialism}} | |||

| ] is the idea that increasingly complex structures in the world give rise to the "emergence" of novel properties that are something over and above (i.e. cannot be reduced to) their more basic constituents (see '']''). The concept of ] dates back to the late 19th century. ] notably argued for an emergentist conception of science in his 1843 work '']''. | |||

| Applied to the mind/body relation, ] is another way of describing the non-reductive physicalist conception of the mind that asserts that when matter is organized in the appropriate way (i.e., organized in the way that living human bodies are organized), ] emerge. | |||

| ===Anomalous monism=== | |||

| {{main|Anomalous monism}} | |||

| Many contemporary non-reductive physicalists subscribe to a position called ] (or something very similar to it). Unlike epiphenomenalism, which renders mental properties causally redundant, anomalous monists believe that mental properties make a causal difference to the world. The position was originally put forward by ] in his 1970 paper ''Mental Events'', which stakes an identity claim between mental and physical tokens based on the notion of supervenience. | |||

| === Biological naturalism=== | |||

| {{main|Biological naturalism}} | |||

| ] is a higher level function of the ]'s physical capabilities.]] | |||

| Another argument for non-reductive physicalism has been expressed by ], who is the advocate of a distinctive form of physicalism he calls biological naturalism. His view is that although mental states are not ] reducible to physical states, they are causally reducible (see ]). He believes the mental will ultimately be explained through neuroscience. This worldview does not necessarily fall under ''property dualism'', and therefore does not necessarily make him a "property dualist". He has acknowledged that "to many people" his views and those of property dualists look a lot alike. But he thinks the comparison is misleading.<ref>Searle, John (1983) "Why I Am Not a Property Dualist", {{cite web |url=http://ist-socrates.berkeley.edu/~jsearle/132/PropertydualismFNL.doc |title=Archived copy |access-date=2007-03-08 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20061210160023/http://ist-socrates.berkeley.edu/~jsearle/132/PropertydualismFNL.doc |archive-date=2006-12-10 }}.</ref> | |||

| == Epiphenomenalism == | == Epiphenomenalism == | ||

| {{ |

{{Main|Epiphenomenalism}} | ||

| Epiphenomenalism is a doctrine about mental-physical causal relations which holds that one or more mental states and their properties are the by-products (or ]) of the states of a closed physical system, and are not causally reducible to physical states (do not have any influence on physical states). According to this view, mental properties are as such real constituents of the world, but they are causally impotent; while physical causes give rise to mental properties like ]s, ], ]s, etc., such mental phenomena themselves cause nothing further - they are causal dead ends.<ref>{{Harnvb|Churchland|1984|page=11}}</ref> | Epiphenomenalism is a doctrine about mental-physical causal relations which holds that one or more mental states and their properties are the by-products (or ]) of the states of a closed physical system, and are not causally reducible to physical states (do not have any influence on physical states). According to this view, mental properties are as such real constituents of the world, but they are causally impotent; while physical causes give rise to mental properties like ]s, ], ]s, etc., such mental phenomena themselves cause nothing further - they are causal dead ends.<ref>{{Harnvb|Churchland|1984|page=11}}</ref> | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| The position is credited to English biologist ] (Huxley 1874), who analogised mental properties to the whistle on a steam locomotive. The position found a level of favor amongst some scientific ] over the next few decades, which then dove in response to the ] in the 1960s. | The position is credited to English biologist ] (Huxley 1874), who analogised mental properties to the whistle on a steam locomotive. The position found a level of favor amongst some scientific ] over the next few decades, which then dove in response to the ] in the 1960s. | ||

| ===Epiphenomenal qualia=== | === Epiphenomenal qualia === | ||

| {{ |

{{Main|Knowledge argument}} | ||

| In the paper "Epiphenomenal Qualia" and later "What Mary Didn't Know" ] made the so-called knowledge argument against physicalism. The ] was originally proposed by Jackson as follows: | In the paper "Epiphenomenal Qualia" and later "What Mary Didn't Know" ] made the so-called knowledge argument against physicalism. The ] was originally proposed by Jackson as follows: | ||

| Line 45: | Line 27: | ||

| Jackson continued: | Jackson continued: | ||

| {{quote|It seems just obvious that she will learn something about the world and our visual experience of it. But then it is inescapable that her previous knowledge was incomplete. But she had all the physical information. Ergo, there is more to have than that, and |

{{quote|It seems just obvious that she will learn something about the world and our visual experience of it. But then it is inescapable that her previous knowledge was incomplete. But she had all the physical information. Ergo, there is more to have than that, and Physicalism is false.<ref name="p130"/>}} | ||

| ⚫ | == Other proponents == | ||

| ==Panpsychist property dualism== | |||

| ⚫ | === Saul Kripke === | ||

| {{Main|Panpsychism}} | |||

| ⚫ | ] has a well-known argument for some kind of property dualism.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Jacquette, Dale|year=1987|title=Kripke and the Mind-Body Problem|journal=Dialectica |volume=41|issue=4|pages=293–300|jstor=42970584}}</ref> Using the concept of ]s, he states that if dualism is ], then it is the case. | ||

| Panpsychism is the view that all matter has a mental aspect, or, alternatively, all objects have a unified center of experience or point of view. Superficially, it seems to be a form of property dualism, since | |||

| it regards everything as having both mental and physical properties. However, some panpsychists say that mechanical behaviour is derived from the primitive mentality of atoms and molecules — as are sophisticated mentality and organic behaviour, the difference being attributed to the presence or absence of ] structure in a compound object. So long as the ''reduction'' of non-mental properties to mental ones is in place, panpsychism is not strictly a form of property dualism; otherwise it is.{{cn|date=February 2019}} | |||

| ] has expressed sympathy for panpsychism (or a modified variant, panprotopsychism) as a possible resolution to the ], though he regards the ] as an important obstacle for the theory.<ref name="Chalmers-caipin">{{cite encyclopedia|last1=Chalmers|first1=David J.|editor1-last=Stich|editor1-first=Stephen P.|editor2-last=Warfield|editor2-first=Ted A.|encyclopedia=The Blackwell Guide to Philosophy of Mind|title=Consciousness and its Place in Nature|date=2003|publisher=Blackwell Publishing Ltd.|location=Malden, MA|isbn=978-0631217756|edition=1st|url=http://consc.net/papers/nature.pdf|access-date=21 January 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171003182905/http://www.consc.net/papers/nature.pdf|archive-date=3 October 2017}}</ref> Other philosophers who have taken interest in the view include ],<ref name="sep-panpsych">{{cite encyclopedia|last=Goff|first=Philip|author2=Seager|author2-first=William|author3=Allen-Hermanson|author3-first=Sean|editor-last=Zalta|editor-first=Edward N.|editor-link=Edward N. Zalta|encyclopedia=Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy|title=Panpsychism|year=2017|url=https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/panpsychism/|access-date=15 September 2018}}</ref> ],<ref name="sep-panpsych"/><ref name="strawson">{{cite journal |last1=Strawson |first1=Galen |title=Realistic monism: Why physicalism entails panpsychism |journal=Journal of Consciousness Studies |date=2006 |volume=13 |issue=10/11 |pages=3–31 |url=http://www.newdualism.org/papers/G.Strawson/strawson_on_panpsychism.pdf |access-date=15 September 2018}}</ref> ],<ref name="sep-panpsych"/> ],<ref name="seager2006">{{cite journal |last1=Seager |first1=William |author-link1=William Seager (philosopher) |title=The Intrinsic Nature Argument for Panpsychism |journal=Journal of Consciousness Studies |date=2006 |volume=13 |issue=10–11 |pages=129–145 |url=https://www.utsc.utoronto.ca/~seager/intnat.pdf |access-date=7 February 2019}}</ref> and ].<ref name="pn-goff">{{cite web |last1=Goff |first1=Philip |title=The Case for Panpsychism |url=https://philosophynow.org/issues/121/The_Case_For_Panpsychism |website=Philosophy Now |access-date=3 October 2018 |date=2017}}</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | ==Other proponents== | ||

| ⚫ | ===Saul Kripke=== | ||

| ⚫ | Kripke has a well-known argument for some kind of property dualism. Using the concept of ]s, he states that if dualism is ], then it is the case. | ||

| {{Quotation|Let 'Descartes' be a name, or rigid designator, of a certain person, and let 'B' be a rigid designator of his body. Then if Descartes were indeed ] to B, the supposed identity, being an identity between two rigid designators, would be ].}}{{Citation needed|date=August 2022}} | {{Quotation|Let 'Descartes' be a name, or rigid designator, of a certain person, and let 'B' be a rigid designator of his body. Then if Descartes were indeed ] to B, the supposed identity, being an identity between two rigid designators, would be ].}}{{Citation needed|date=August 2022}} | ||

| ==Subjective idealism== | |||

| ], proposed in the eighteenth century by ], is an ontic doctrine that directly opposes ] or ]. It does not admit ontic property dualism, but does admit epistemic property dualism. It is rarely advocated by philosophers nowadays. | |||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

| ⚫ | * "]" | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * "]" | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| ==Notes== | == Notes == | ||

| {{ |

{{Reflist}} | ||

| ==References== | == References == | ||

| * {{cite book|year=1984|title=Matter and Consciousness|last=Churchland|first=Paul}} | * {{cite book|year=1984|title=Matter and Consciousness|last=Churchland|first=Paul}} | ||

| * Davidson, D. (1970) "Mental Events", in Actions and Events, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980 | * Davidson, D. (1970) "Mental Events", in Actions and Events, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980 | ||

| Line 89: | Line 61: | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | |||

| {{ |

{{Mind–body dualism}} | ||

| {{Philosophy of mind}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Property Dualism}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Property Dualism}} | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

Latest revision as of 00:43, 8 December 2024

Category of positions in the philosophy of mind

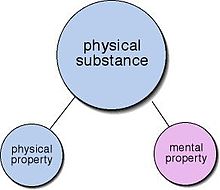

Property dualism describes a category of positions in the philosophy of mind which hold that, although the world is composed of just one kind of substance—the physical kind—there exist two distinct kinds of properties: physical properties and mental properties. In other words, it is the view that at least some non-physical, mental properties (such as thoughts, imagination and memories) exist in, or naturally supervene upon, certain physical substances (namely brains).

Substance dualism, on the other hand, is the view that there exist in the universe two fundamentally different kinds of substance: physical (matter) and non-physical (mind or consciousness), and subsequently also two kinds of properties which inhere in those respective substances. Both substance and property dualism are opposed to reductive physicalism. Notable proponents of property dualism include David Chalmers, Christof Koch and Richard Fumerton. It became prominent in the final decades of the twentieth century and is now the leading alternative to physicalism.

Epiphenomenalism is viewed as a form of property dualism.

Definition

Property dualism posits the existence of one material substance with essentially two different kinds of property: physical properties and mental properties. It argues that there are different kinds of properties that pertain to the only type of substance, the material substance: there are physical properties such as having colour or shape and there are mental properties like having certain beliefs or perceptions.

Epiphenomenalism

Main article: EpiphenomenalismEpiphenomenalism is a doctrine about mental-physical causal relations which holds that one or more mental states and their properties are the by-products (or epiphenomena) of the states of a closed physical system, and are not causally reducible to physical states (do not have any influence on physical states). According to this view, mental properties are as such real constituents of the world, but they are causally impotent; while physical causes give rise to mental properties like sensations, volition, ideas, etc., such mental phenomena themselves cause nothing further - they are causal dead ends.

The position is credited to English biologist Thomas Huxley (Huxley 1874), who analogised mental properties to the whistle on a steam locomotive. The position found a level of favor amongst some scientific behaviorists over the next few decades, which then dove in response to the cognitive revolution in the 1960s.

Epiphenomenal qualia

Main article: Knowledge argumentIn the paper "Epiphenomenal Qualia" and later "What Mary Didn't Know" Frank Jackson made the so-called knowledge argument against physicalism. The thought experiment was originally proposed by Jackson as follows:

Mary is a brilliant scientist who is, for whatever reason, forced to investigate the world from a black and white room via a black and white television monitor. She specializes in the neurophysiology of vision and acquires, let us suppose, all the physical information there is to obtain about what goes on when we see ripe tomatoes, or the sky, and use terms like 'red', 'blue', and so on. She discovers, for example, just which wavelength combinations from the sky stimulate the retina, and exactly how this produces via the central nervous system the contraction of the vocal cords and expulsion of air from the lungs that results in the uttering of the sentence 'The sky is blue'. What will happen when Mary is released from her black and white room or is given a color television monitor? Will she learn anything or not?

Jackson continued:

It seems just obvious that she will learn something about the world and our visual experience of it. But then it is inescapable that her previous knowledge was incomplete. But she had all the physical information. Ergo, there is more to have than that, and Physicalism is false.

Other proponents

Saul Kripke

Saul Kripke has a well-known argument for some kind of property dualism. Using the concept of rigid designators, he states that if dualism is logically possible, then it is the case.

Let 'Descartes' be a name, or rigid designator, of a certain person, and let 'B' be a rigid designator of his body. Then if Descartes were indeed identical to B, the supposed identity, being an identity between two rigid designators, would be necessary.

See also

- "What Is It Like to Be a Bat?"

- Chinese room

- Explanatory gap

- Functionalism (philosophy of mind)

- Physicalism

- Qualia

Notes

- Bratcher, Daniel (1999). "David Chalmers' Arguments for Property Dualism". Philosophy Today. 43 (3): 292–301. doi:10.5840/philtoday199943319.

- Slagle, Jim (2015). "Knowledge, Thought, and the Case for Dualism". International Journal of Philosophical Studies. 23 (5): 776–779. doi:10.1080/09672559.2015.1099972.

- Owen, Matthew (2018). "Dusting Off Dualism?". American Philosophical Association.

- Weir, Ralph Stefan (2024). The mind-body problem and metaphysics: an argument from consciousness to mental substance. Routledge studies in contemporary philosophy. New York (N.Y.): Routledge. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-1-032-45768-0.

- ^ Vintiadis, Elly (2019). "Property Dualism". Rebus Community. Archived from the original on September 25, 2024.

- Churchland 1984, p. 11

- ^ Jackson 1982, p. 130 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFJackson1982 (help)

- Jacquette, Dale (1987). "Kripke and the Mind-Body Problem". Dialectica. 41 (4): 293–300. JSTOR 42970584.

References

- Churchland, Paul (1984). Matter and Consciousness.

- Davidson, D. (1970) "Mental Events", in Actions and Events, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980

- Huxley, Thomas. (1874) "On the Hypothesis that Animals are Automata, and its History", The Fortnightly Review, n.s. 16, pp. 555–580. Reprinted in Method and Results: Essays by Thomas H. Huxley (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1898)

- Jackson, F. (1982) "Epiphenomenal Qualia", The Philosophical Quarterly 32: 127-136.

- Kim, Jaegwon. (1993) "Supervenience and Mind", Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- MacLaughlin, B. (1992) "The Rise and Fall of British Emergentism", in Beckerman, et al. (eds), Emergence or Reduction?, Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Mill, John Stuart (1843). "System of Logic". London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer. .

External links

- M. D. Robertson: Dualism vs. Materialism: A Response to Paul Churchland

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Dualism

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Epiphenomenalism

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Physicalism