| Revision as of 17:03, 22 September 2008 view sourceSunray (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers37,109 editsm Reverted edits by 204.82.246.119 (talk) to last version by Sardanaphalus← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 23:05, 8 December 2024 view source Skakkle (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users8,092 edits →topTags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit Android app edit App full source | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Political ideology based on individual rights and liberty}} | |||

| {{dablink|This article discusses the ] of liberalism. Local differences in its meaning are listed in ]. For other uses, see ].}} | |||

| {{other uses|Liberal (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Liberalism sidebar expanded}} | |||

| {{distinguish|Libertarianism}} | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef|small=yes}} | |||

| {{use dmy dates|date=July 2015}} | |||

| {{use British English|date=January 2014}} | |||

| {{liberalism sidebar}} | |||

| {{party politics}} | |||

| '''Liberalism''' is a ] and ] based on the ], ], ], ], the ] and ].<ref>"liberalism In general, the belief that it is the aim of politics to preserve individual rights and to maximize freedom of choice." ''Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics'', Iain McLean and Alistair McMillan, Third edition 2009, {{ISBN|978-0-19-920516-5}}.</ref><ref name="wpt">{{cite book |quote=political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for conservatism and for tradition in general, tolerance, and ... individualism. |first=John |last=Dunn |title=Western Political Theory in the Face of the Future |date=1993 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-521-43755-4}}</ref> Liberals espouse various and often mutually warring views depending on their understanding of these principles but generally support ], ], individual rights (including ] and ]), ], ], ], ] and ], ], ], ], and ].<ref name="Generally support">Generally support: | |||

| '''Liberalism''' is a broad array of related ideas and theories of ] that consider ] ] to be the most important political goal.<ref>A: "'Liberalism' is defined as a social ethic that advocates liberty, and equality in general." – ] ''Distributive Justice'', A Companion to Contemporary Political Philosophy, editors Goodin, Robert E. and Pettit, Philip. Blackwell Publishing, 1995, p.440. B: "Liberty is not a means to a higher political end. It is itself the highest political end." – ]</ref> Modern liberalism has its roots in the ]. Liberalism rejected many ] assumptions that dominated most earlier theories of government, such as the ], hereditary status, ], and ]. | |||

| *{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UkVIYjezrF0C&q=liberalism+secularism |first=Nader |last=Hashemi |title=Islam, Secularism, and Liberal Democracy: Toward a Democratic Theory for Muslim Societies |publisher=] |quote=Liberal democracy requires a form of secularism to sustain itself |year=2009 |isbn=978-0-19-971751-4 |via=]}} | |||

| *{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=htuTnexZAo8C&q=liberalism+freedom+of+religion&pg=PA1 |first=Kathleen G. |last=Donohue |title=Freedom from Want: American Liberalism and the Idea of the Consumer |series=New Studies in American Intellectual and Cultural History |publisher=] |quote=Three of them – freedom from fear, freedom of speech, and freedom of religion – have long been fundamental to liberalism. |isbn=978-0-8018-7426-0 |date=19 December 2003 |access-date=31 December 2007 |via=]}} | |||

| *{{cite news |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KBzHAAAAIAAJ&q=liberalism+freedom+of+religion |title=The Economist, Volume 341, Issues 7995–7997 |newspaper=] |quote=For all three share a belief in the liberal society as defined above: a society that provides constitutional government (rule by law, not by men) and freedom of religion, thought, expression and economic interaction; a society in which ... . |year=1996 |access-date=31 December 2007 |via=]}} | |||

| *{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ndAdGl8ScfcC&q=liberalism+freedom+of+religion&pg=PA525 |first=Sheldon S. |last=Wolin |title=Politics and Vision: Continuity and Innovation in Western Political Thought |publisher=] |quote=The most frequently cited rights included freedom of speech, press, assembly, religion, property, and procedural rights |isbn=978-0-691-11977-9 |year=2004 |access-date=31 December 2007 |via=]}} | |||

| *{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mQJgnEITPRIC&q=liberalism+freedom+of+religion&pg=PA366 |first1=Edwin Brown |last1=Firmage |first2=Bernard G. |last2=Weiss |first3=John Woodland |last3=Welch |title=Religion and Law: Biblical-Judaic and Islamic Perspectives |publisher=] |quote=There is no need to expound the foundations and principles of modern liberalism, which emphasises the values of freedom of conscience and freedom of religion |isbn=978-0-931464-39-3 |year=1990 |access-date=31 December 2007 |via=]}} | |||

| *{{cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/cyclopaediapoli00lalogoog |page= |first=John Joseph |last=Lalor |author-link=John Joseph Lalor |title=Cyclopædia of Political Science, Political Economy, and of the Political History of the United States |publisher=Nabu Press |quote=Democracy attaches itself to a form of government: liberalism, to liberty and guarantees of liberty. The two may agree; they are not contradictory, but they are neither identical, nor necessarily connected. In the moral order, liberalism is the liberty to think, recognised and practiced. This is primordial liberalism, as the liberty to think is itself the first and noblest of liberties. Man would not be free in any degree or in any sphere of action, if he were not a thinking being endowed with consciousness. The freedom of worship, the freedom of education, and the freedom of the press are derived the most directly from the freedom to think. |year=1883 |access-date=31 December 2007}} | |||

| *{{Cite web |title=Liberalism |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/liberalism |access-date=2021-06-16 |website=Encyclopedia Britannica |language=en}}] and ] | |||

| *{{Cite book |title=The Desk Encyclopedia of World History |publisher=] |year=2006 |isbn=978-0-7394-7809-7 |editor-last=Wright |editor-first=Edmund |location=New York |pages=374}} | |||

| </ref> Liberalism is frequently cited as the dominant ] of ].<ref name=":1">Wolfe, p. 23.</ref><ref name="Adams 2011">{{cite book|last=Adams|first=Ian|title=Political Ideology Today|url=https://archive.org/details/politicalideolog0000adam/mode/2up?view=theater|url-access = registration|chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/politicalideolog0000adam/page/10/mode/2up?view=theater|chapter-url-access = registration|edition=Second|series=Politics Today|year=2001|publisher=Manchester University Press|location=Manchester and New York|isbn=0-7190-6019-2|chapter=2: Liberalism and democracy}}</ref>{{rp|11}} | |||

| Liberalism became a distinct ] in the ], gaining popularity among ] philosophers and ]s. Liberalism sought to replace the ] of ], ], ], the ] and ] with ], rule of law, and equality under the law. Liberals also ended ] policies, ], and other ]s, instead promoting ] and marketization.<ref name="Gould, p. 3"/> Philosopher ] is often credited with founding liberalism as a distinct tradition based on the '']'', arguing that each man has a ] to ], and governments must not violate these ].<ref>{{cite book |quote=All mankind ... being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions |first=John |last=Locke |author-link=John Locke |title=Second Treatise of Government}}</ref> While the ] has emphasized expanding democracy, ] has emphasized rejecting ] and is linked to ].<ref name="Kirchner, p. 3">Kirchner, p. 3.</ref> | |||

| ], first formulated by ] and others, supports ]s and ] as the best route to peace and prosperity. Pioneers of liberal economic thought discovered how ] and ] leads to prosperity, provided that at least minimum standards of public information and justice exist, e.g., no-one should be allowed to coerce or steal. Private ] and individual ]s form the basis of economic liberalism. | |||

| Leaders in the British ] of 1688,<ref>{{cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/1688firstmodernr00stev |url-access=registration |title=1688: The First Modern Revolution |first=Steven |last=Pincus |year=2009 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-300-15605-8 |access-date=7 February 2013}}</ref> the ] of 1776, and the ] of 1789 used liberal philosophy to justify the armed overthrow of royal ]. The 19th century saw liberal governments established in ] and ], and it was well-established alongside ].<ref>{{cite book |first=Milan |last=Zafirovski |title=Liberal Modernity and Its Adversaries: Freedom, Liberalism and Anti-Liberalism in the 21st Century |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GNlT9Qho0tAC&pg=PA237 |year=2007 |publisher=] |page=237 |isbn=978-90-04-16052-1 |via=]}}</ref> In ], it was used to critique the political establishment, appealing to science and reason on behalf of the people.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Eddy |first1=Matthew Daniel |title=The Politics of Cognition: Liberalism and the Evolutionary Origins of Victorian Education |journal=British Journal for the History of Science |date=2017 |volume=50 |issue=4 |pages=677–699 |doi=10.1017/S0007087417000863 |pmid=29019300 |doi-access=free |issn=0007-0874 }}</ref> During the 19th and early 20th centuries, ] and the ] influenced periods of reform, such as the ] and ], and the rise of ], ], and ]. These changes, along with other factors, helped to create a sense of crisis within ], which continues to this day, leading to ]. Before 1920, the main ideological opponents of liberalism were ], ], and ];<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Lta_DwAAQBAJ |title=Liberalism and Its Critics |last=Koerner |first=Kirk F. |publisher=] |year=1985 |isbn=978-0-429-27957-7 |location=London |via=]}}</ref> liberalism then faced major ideological challenges from ] and ] as new opponents. During the 20th century, liberal ideas spread even further, especially in Western Europe, as liberal democracies found themselves as the winners in both ]<ref>{{cite book |last=Conway |first=Martin |editor-last=Gosewinkel |editor-first=Dieter |title=Anti-liberal Europe: A Neglected Story of Europeanization |chapter=The Limits of an Anti-liberal Europe |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ECIfAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA184 |year=2014 |publisher=] |page=184 |isbn=978-1-78238-426-7 |quote=Liberalism, liberal values and liberal institutions formed an integral part of that process of European consolidation. Fifteen years after the end of the Second World War, the liberal and democratic identity of Western Europe had been reinforced on almost all sides by the definition of the West as a place of freedom. Set against the oppression in the Communist East, by the slow development of a greater understanding of the moral horror of Nazism, and by the engagement of intellectuals and others with the new states (and social and political systems) emerging in the non-European world to the South. |via=]}}</ref> and the ].<ref>Stern, Sol (Winter, 2010) '']''</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Fukuyama |first=Francis |date=1989 |title=The End of History? |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/24027184 |journal=The National Interest |issue=16 |pages=3–18 |jstor=24027184 |issn=0884-9382}}</ref> | |||

| ] focuses on the rights of individuals pertaining to conscience and lifestyle, including such issues as sexual freedom, religious freedom, cognitive freedom, and protection from government intrusion into private life. | |||

| Liberals sought and established a constitutional order that prized important ], such as ] and ]; an ] and public ]; and the abolition of ] privileges.<ref name="Gould, p. 3" /> Later waves of modern liberal thought and struggle were strongly influenced by the need to expand civil rights.<ref name="Worell470">Worell, Judith. ''Encyclopedia of women and gender, Volume I''. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2001. {{ISBN|0-12-227246-3}}</ref> Liberals have advocated gender and racial equality in their drive to promote civil rights, and global ] in the 20th century achieved several objectives towards both goals. Other goals often accepted by liberals include ] and ]. In Europe and North America, the establishment of ] (often called simply ] in the United States) became a key component in expanding the ].<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180212050753/http://www.writing.upenn.edu/~afilreis/50s/schleslib.html |date=12 February 2018 }} by ] (1956) from: ''The Politics of Hope'' (Boston: Riverside Press, 1962). "Liberalism in the U.S. usage has little in common with the word as used in the politics of any other country, save possibly Britain."</ref> Today, ] continue to wield power and influence ]. The fundamental elements of ] have liberal roots. The early waves of liberalism popularised economic individualism while expanding constitutional government and ]ary authority.<ref name="Gould, p. 3">Gould, p. 3.</ref> | |||

| Different forms of liberalism may propose very different policies, but they are generally united by their support for a number of principles, including extensive ] and ], limitations on the power of governments, the ], the free exchange of ideas, private property, ]s, and a ] ].<ref> Compare for the latter aspect the of 1947 of the ] (''Respect for the language, faith, laws and customs of national minorities''), of 1997 (''We believe that close cooperation among democratic societies through global and regional organizations, within the framework of international law, of respect for human rights, the rights of national and ethnic minorities, and of a shared commitment to economic development worldwide, is the necessary foundation for world peace and for economic and environmental sustainability''), the (''Protecting the rights of minorities flows naturally from liberal policy, which seeks to ensure equal opportunities for everyone'') and, e.g., of ]</ref> All liberals{{ndash}} as well as some adherents of other political ideologies{{ndash}} support some variant of the form of government known as ], with open and fair elections, where all citizens have equal rights by law.<ref>Compare the of the ] (''These rights and conditions can be secured only by true democracy. True democracy is inseparable from political liberty and is based on the conscious, free and enlightened consent of the ], expressed through a free and secret ballot, with due respect for the liberties and opinions of minorities'')</ref> | |||

| ==Definitions== | |||

| There are many disagreements within liberalism, especially when economic freedom and social justice come into conflict. The movement called ] asserts that the only real freedom is freedom from ].<ref name="McGowan">McGowan, J. (2007). ''American Liberalism: An Interpretation for Our Time''. Chapel Hill, NC: North Carolina University Press.</ref> | |||

| ===Origins=== | |||

| {{libertarianism sidebar|origins}} | |||

| '']'', '']'', '']'', and '']'' all trace their ] to '']'', a ] from ] that means "]".<ref name="Gross, p. 5">Gross, p. 5.</ref> One of the first recorded instances of ''liberal'' occurred in 1375 when it was used to describe the ] in the context of an education desirable for a free-born man.<ref name="Gross, p. 5"/> The word's early connection with the classical education of a medieval university soon gave way to a proliferation of different denotations and connotations. ''Liberal'' could refer to "free in bestowing" as early as 1387, "made without stint" in 1433, "freely permitted" in 1530, and "free from restraint"—often as a pejorative remark—in the 16th and the 17th centuries.<ref name="Gross, p. 5"/> | |||

| In the 16th-century ], ''liberal'' could have positive or negative attributes in referring to someone's generosity or indiscretion.<ref name="Gross, p. 5"/> In '']'', ] wrote of "a liberal villaine" who "hath ... confest his vile encounters".<ref name="Gross, p. 5"/> With the rise of ], the word acquired decisively more positive undertones, defined as "free from narrow prejudice" in 1781 and "free from bigotry" in 1823.<ref name="Gross, p. 5"/> In 1815, the first use of ''liberalism'' appeared in English.<ref>Kirchner, pp. 2–3.</ref> In Spain, the '']'', the first group to use the liberal label in a political context,<ref>Palmer and Colton, p. 479.</ref> fought for decades to implement the ]. From 1820 to 1823, during the '']'', ] was compelled by the ''liberales'' to swear to uphold the 1812 Constitution. By the middle of the 19th century, ''liberal'' was used as a politicised term for parties and movements worldwide.<ref>Kirchner, Emil J. (1988). ''Liberal Parties in Western Europe''. Cambridge University Press. {{ISBN|978-0-521-32394-9}}. "Liberal parties were among the first political parties to form, and their long-serving and influential records, as participants in parliaments and governments, raise important questions ... ."</ref> | |||

| ==Etymology and historical usage== | |||

| The word "liberal" derives from the ] ''liber'' ("free, not slave"), and is associated with the word "liberty" and the concept of freedom. ]'s ''History of Rome from Its Foundation'' describes the struggles for freedom between the ] and ] classes. ] in his ''Meditations'' writes about ". . . the idea of a polity administered with regard to equal rights and equal freedom of speech, and the idea of a kingly government which respects most of all the freedom of the governed." Largely dormant during the ]s, the struggle for freedom began again in the ], in the conflict between the supporters of free city-states and supporters of the ] or the Holy Roman Emperor. ], in his ''Discourses on Livy'', laid down the principles of ]an government. ] in ] and the thinkers of the ] ] articulated the struggle for freedom in terms of the ]. | |||

| ] is the ] most commonly associated with liberalism.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Adams |first1=Sean |url=https://archive.org/details/colordesignworkb0000ston/page/86 |title=Color Design Workbook: A Real World Guide to Using Color in Graphic Design |last2=Morioka |first2=Noreen |last3=Stone |first3=Terry Lee |date=2006 |publisher=Rockport Publishers |isbn=1-59253-192-X |location=Gloucester, Mass. |pages= |oclc=60393965}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Kumar |first1=Rohit Vishal |last2=Joshi |first2=Radhika |date=October–December 2006 |title=Colour, Colour Everywhere: In Marketing Too |journal=SCMS Journal of Indian Management |volume=3 |issue=4 |pages=40–46 |issn=0973-3167 |ssrn=969272}}</ref><ref>Cassel-Picot, Muriel "The Liberal Democrats and the Green Cause: From Yellow to Green" in Leydier, Gilles and Martin, Alexia (2013) ''Environmental Issues in Political Discourse in Britain and Ireland''. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221206080446/https://books.google.ca/books?id=fFgxBwAAQBAJ&lpg=PP1&pg=PA105 |date=6 December 2022 }}. {{isbn|9781443852838}}</ref> The ] differs from other countries in that conservatism is associated with red and ] with blue.<ref>{{Cite book |title=Color Design Workbook: A Real World Guide to Using Color in Graphic Design |last1=Adams |first1=Sean |last2=Morioka |first2=Noreen |last3=Stone |first3=Terry Lee |date=2006 |publisher=] |isbn=159253192X |location=Gloucester, Mass. |pages= |oclc=60393965 |url=https://archive.org/details/colordesignworkb0000ston/page/86}}</ref> | |||

| The '']'' (''OED'') indicates that the word ''liberal'' has long been in the ] with the meanings of "befitting free men, noble, generous" as in '']''; also with the meaning "free from restraint in speech or action", as in ''liberal with the purse'', or ''liberal tongue'', usually as a term of reproach but, beginning 1776–88 imbued with a more favorable sense by ] and others to mean "free from prejudice, tolerant." | |||

| ===Modern usage and definitions=== | |||

| The first English language use to mean "tending in favor of freedom and ]," according to the ''OED,'' dates from about 1801 and comes from the ] ''libéral,'' "originally applied in English by its opponents (often in Fr. form and with suggestions of foreign lawlessness)." An early English language citation: "The extinction of every vestige of freedom, and of every liberal idea with which they are associated."<ref>Hel. M. WILLIAMS, Sk. Fr. Rep. I. xi. 113," (presumably ]) ''Sketches of the State of Manners and Opinions in the French Republic.'' 1801. Cited in the ''].''</ref> | |||

| In Europe and Latin America, ''liberalism'' means a moderate form of ] and includes both ] (] liberalism) and ] (] liberalism).<ref name="Nordsieck contents">{{cite web |url=http://www.parties-and-elections.eu/content.html |title=Content |date=2020 |website=Parties and Elections in Europe}}</ref> | |||

| In North America, ''liberalism'' almost exclusively refers to social liberalism. The dominant Canadian party is the ], and the ] is usually considered liberal in the United States.<ref>Puddington, p. 142. "After a dozen years of centre-left Liberal Party rule, the Conservative Party emerged from the 2006 parliamentary elections with a plurality and established a fragile minority government."</ref><ref>Grigsby, pp. 106–07. "Its liberalism is, for the most part, the later version of liberalism – modern liberalism."</ref><ref>Arnold, p. 3. "Modern liberalism occupies the left-of-center in the traditional political spectrum and is represented by the Democratic Party in the United States."</ref> In the United States, conservative liberals are usually called ''conservatives'' in a broad sense.<ref name="Friedman">{{cite book |editor-last=Cayla |editor-first=David |title=Populism and Neoliberalism |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pDAXEAAAQBAJ&dq=Neoliberalism+%22conservative+liberalism%22&pg=PA62 |date=2021 |page=62 |publisher=] |isbn=9781000366709 |via=]}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |editor-last=Slomp |editor-first=Hans |title=Europe, A Political Profile: An American Companion to European Politics, Volume 1 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LmfAPmwE6YYC&q=EU+left-wing+liberal+parties |date=2011 |pages=106–108 |publisher=] |isbn=9780313391811 |via=]}}</ref> | |||

| The ] established the first nation to craft a constitution based on the concept of liberal government, especially the idea that governments rule by the consent of the governed. The more moderate '']'' elements of the ] tried to establish a government based on liberal principles. ]s such as ], in '']'' (1776), enunciated the liberal principles of free trade. The editors of the ], drafted in ], may have been the first to use the word ''liberal'' in a political sense as a noun. They named themselves the ''Liberales,'' to express their opposition to the ] power of the Spanish ]. | |||

| ====Social liberalism==== | |||

| Beginning in the late 18th century, liberalism became a major ideology in virtually all developed countries. | |||

| {{see also|Social liberalism|Welfare state|Liberalism in the United States}} | |||

| Over time, the meaning of ''liberalism'' began to diverge in different parts of the world. Since the 1930s, ''liberalism'' is usually used without a qualifier in the United States, to refer to ], a variety of liberalism that endorses a ] economy and the expansion of ], with the common good considered as compatible with or superior to the freedom of the individual.<ref>De Ruggiero, Guido (1959). ''The History of European Liberalism''. pp. 155–157.</ref> | |||

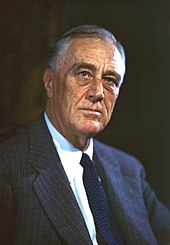

| According to the '']'': "In the United States, liberalism is associated with the welfare-state policies of the New Deal programme of the Democratic administration of Pres. ], whereas in Europe it is more commonly associated with a commitment to ] and '']'' economic policies."<ref>"Liberalism". ''Encyclopædia Britannica''.</ref> This variety of liberalism is also known as '']'' to distinguish it from ''classical liberalism'', which evolved into ]. In the United States, the two forms of liberalism comprise the two main poles of American politics, in the forms of '']'' and '']''.<ref>Pease, Donald E.; Wiegman, Robyn (eds.) (2002). ''The Futures of American Studies''. Duke University Press. p. 518.</ref> | |||

| === Trends === | |||

| Within the above framework, there are deep, often bitter, conflicts and controversies among liberals. Emerging from those controversies, out of ], are a number of different trends within liberalism. As in many debates, opposite sides use different words for the same beliefs, and sometimes use identical words for different beliefs. For the purposes of this article, we will use "]" for the support of (liberal) democracy (either in a republic or a ]), over ] or dictatorship; "]" for the support of individual liberty over laws limiting liberty for patriotic or religious reasons; "]" for the support of private property, over government regulation; and "]" for the support of equality under the law, and relief provided by the government from suffering caused by poverty or natural disaster. By "modern liberalism" we mean the mixture of these forms of liberalism found in most ] countries today, rather than any one of the pure forms listed above. | |||

| Some liberals, who call themselves ''classical liberals'', '']'', or '']'', endorse fundamental liberal ideals but diverge from modern liberal thought on the grounds that ] is more important than ].<ref>Pena, David S. (2001). ''Economic Barbarism and Managerialism''. p. 35.</ref> Consequently, the ideas of ] and ''laissez-faire'' economics previously associated with ] are key components of modern ] and ], and became the basis for the emerging school of modern ] thought.<ref>Rothbard, Murray (2006) . . '']''. ]. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150618045238/http://archive.lewrockwell.com/rothbard/rothbard121.html |date=18 June 2015 }}. Retrieved 18 June 2015 – via LewRockewell.com</ref>{{better source needed|date=December 2020}} In this American context, ''liberal'' is often used as a pejorative.<ref>{{cite news |date=6 January 2012 |title=The failure of American political speech |newspaper=] |url=https://www.economist.com/johnson/2012/01/06/the-failure-of-american-political-speech |access-date=1 September 2022 |issn=0013-0613}}</ref> | |||

| {{cquote|Liberalism wagers that a state . . . can be strong but constrained – strong because constrained . . . Rights to education and other requirements for human development and security aim to advance equal opportunity and personal dignity and to promote a creative and productive society. To guarantee those rights, liberals have supported a wider social and economic role for the state, counterbalanced by more robust guarantees of civil liberties and a wider social system of checks and balances anchored in an independent press and pluralistic society. – ], sociologist at ], '']'', March 2007}} | |||

| This political philosophy is exemplified by enactment of major social legislation and welfare programs. Two major examples in the United States are ]'s ] policies and later ]'s ], as well as other accomplishments such as the ] and the ] in 1935, as well as the ] and the ]. | |||

| Some principles liberals generally agree upon: | |||

| Modern liberalism, in the United States and other major Western countries, now includes issues such as ], ], the abolition of ], ] and other ], ] for all adult citizens, civil rights, ], and government protection of the ].<ref>{{cite journal|author=Jeffries, John W.|title=The "New" New Deal: FDR and American Liberalism, 1937–1945|journal=Political Science Quarterly|volume=105|number=3|date=1990|pages=397–418|doi=10.2307/2150824|jstor=2150824}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=2013-01-31 |title=Coretta's Big Dream: Coretta Scott King on Gay Rights |url=https://www.huffpost.com/entry/coretta-scott-king_b_2592049 |access-date=2023-06-21 |website=HuffPost |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/02/11/deep-partisan-divide-on-whether-greater-acceptance-of-transgender-people-is-good-for-society/ | title=Deep partisan divide on whether greater acceptance of transgender people is good for society }}</ref> National ], such as equal educational opportunities, access to health care, and transportation infrastructure are intended to meet the responsibility to promote the ] of all citizens as established by the ]. | |||

| :* ''']''' is the belief that individuals are the basis of law and society, and that society and its institutions exist to further the ends of individuals, without showing favor to those of higher social rank. '']'' is an example of a political document that asserted the rights of individuals even above the prerogatives of monarchs. Political liberalism stresses the ], under which citizens make the laws and agree to abide by those laws. It is based on the belief that individuals know best what is best for them. Political liberalism enfranchises all adult citizens regardless of sex, race, or economic status. Political liberalism emphasizes the ] and supports ]. | |||

| ====Classical liberalism==== | |||

| :* ''']''' focuses on the rights of individuals pertaining to conscience and lifestyle, including such issues as sexual freedom, religious freedom, cognitive freedom, and protection from government intrusion into private life. ] aptly expressed cultural liberalism in his essay "On Liberty," when he wrote, | |||

| {{see also|Classical liberalism|Conservative liberalism}} | |||

| :{{cquote|The sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self-protection. That the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or moral, is not a sufficient warrant.}} | |||

| Classical liberalism is a ] and a ] of liberalism that advocates ] and ] economics and ] under the ], with special emphasis on individual autonomy, ], ], ] and ].<ref>{{cite web |title=Classical liberalism |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/classical-liberalism |website=www.britannica.com |publisher=] |access-date=17 October 2023 |date=6 September 2023}}</ref> Classical liberalism, contrary to liberal branches like ], looks more negatively on ], ]ation and the state involvement in the lives of individuals, and it advocates ].<ref>{{cite book| first1 = M. O. | last1 = Dickerson | last2 = Flanagan | first2 = Thomas | last3 = O'Neill| first3 = Brenda | title = An Introduction to Government and Politics: A Conceptual Approach | date = 2009| p=129}}</ref> | |||

| ::Cultural liberalism generally opposes government regulation of ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ] and other ]. Most liberals oppose some or all government intervention in these areas. The ], in this respect, may be the most liberal country in the world today. | |||

| Until the ] and the rise of social liberalism, classical liberalism was called ]. Later, the term was applied as a ], to distinguish earlier 19th-century liberalism from social liberalism.{{sfn|Richardson|2001|p=52}} By modern standards, in ], the bare term ''liberalism'' often means social liberalism, but in ] and ], the bare term ''liberalism'' often means classical liberalism.<ref>{{cite news |last=Goldfarb |first=Michael |date=20 July 2010 |title=Liberal? Are we talking about the same thing? |language=en-GB |publisher=] |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-10658070 |access-date=6 August 2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last=Greenberg |first=David |date=12 September 2019 |title=The danger of confusing liberals and leftists |newspaper=] |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/09/12/stop-calling-bernie-sanders-alexandria-ocasio-cortez-liberals/ |access-date=6 August 2020}}</ref> | |||

| However, some trends within liberalism reveal stark differences of opinion: | |||

| Classical liberalism gained full flowering in the early 18th century, building on ideas dating at least as far back as the 16th century, within the Iberian, British, and Central European contexts, and it was foundational to the ] and "American Project" more broadly.<ref>{{cite book |last=Douma |first=Michael |title=What is Classical Liberal History? |date=2018 |publisher=Lexington Books |isbn=978-1-4985-3610-3}}</ref>{{sfn|Dickerson|Flanagan|O'Neill|2009|p=129}}<ref>{{cite web |last=Renshaw |first=Catherine |date=2014-03-18 |title=What is a 'classical liberal' approach to human rights? |url=http://theconversation.com/what-is-a-classical-liberal-approach-to-human-rights-24452 |access-date=2022-08-12 |website=The Conversation}}</ref> Notable liberal individuals whose ideas contributed to classical liberalism include ],<ref name="Steven M. Dworetz 1994">Steven M. Dworetz (1994). ''The Unvarnished Doctrine: Locke, Liberalism, and the American Revolution''.</ref> ], ], and ]. It drew on ], especially the economic ideas espoused by ] in Book One of '']'', and on a belief in ].<ref>{{cite book |last=Appleby |first=Joyce |author-link=Joyce Appleby |title=Liberalism and Republicanism in the Historical Imagination |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=83HlqTJjLcgC&pg=PA58 |publisher=] |date=1992 |page=58 |isbn=978-0674530133}}</ref> In contemporary times, ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ] are seen as the most prominent advocates of classical liberalism.<ref>{{cite book |last=Dilley |first=Stephen C. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XAIQOVWz2hEC |title=Darwinian Evolution and Classical Liberalism: Theories in Tension |date=2013-05-02 |publisher=Lexington Books |isbn=978-0-7391-8107-2 |pages=13–14}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last=Peters |first=Michael A. |date=2022-04-16 |title=Hayek as classical liberal public intellectual: Neoliberalism, the privatization of public discourse and the future of democracy |journal=Educational Philosophy and Theory |volume=54 |issue=5 |pages=443–449 |doi=10.1080/00131857.2019.1696303 |s2cid=213420239 |issn=0013-1857|doi-access=free}}</ref> However, other scholars have made reference to these contemporary thoughts as '']'', distinguishing them from 18th-century classical liberalism.<ref name="Mayne 1999 p. 124">Mayne, Alan James (1999). ''From Politics Past to Politics Future: An Integrated Analysis of Current and Emergent Paradigmss''. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 124–125. {{ISBN|0275961516}}.</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Ishiyama |first1=John T. |title=21st Century Political Science A Reference Handbook |last2=Breuning |first2=Marijke |collaboration=Ellen Grigsby |publisher=SAGE Publications, Inc. |year=2011 |isbn=978-1-4129 6901-7 |pages=596–603 |chapter=Neoclassical liberals}}</ref> | |||

| :* ''']''', also called '']'' or '']'', is an ideology which supports the individual rights of property and freedom of contract, without which, it argues, the exercise of other liberties is impossible. It advocates '']'' ], meaning the removal of legal barriers to trade and cessation of government-bestowed privilege such as subsidy and monopoly. Economic liberals want little or no government regulation of the ]. Some economic liberals would accept government restrictions of ] and ]s, others argue that ] and ]s are caused by state action. Economic liberalism holds that the value of goods and services should be set by the unfettered choices of individuals, that is, of market forces. Some would also allow market forces to act even in areas conventionally monopolized by governments, such as the provision of security and courts. Economic liberalism accepts the economic inequality that arises from unequal bargaining positions as being the natural result of competition, so long as no coercion is used. This form of liberalism is especially influenced by English liberalism of the mid 19th century. ] and ] are forms of economic liberalism. (See also ], ], ]) | |||

| In the context of American politics, "classical liberalism" may be described as "fiscally conservative" and "socially liberal".<ref>{{Cite book |title=The Desk Encyclopedia of World History |publisher=] |year=2006 |isbn=978-0-7394-7809-7 |editor-last=Wright |editor-first=Edmund |location=New York |pages=370}}</ref> Despite this, classical liberals tend to reject ]'s higher tolerance for ] and ] inclination for collective ] due to classical liberalism's central principle of ].<ref>{{cite web |last1=Goodman |first1=John C. |title=Classical Liberalism vs. Modern Liberalism and Modern Conservatism |url=https://www.goodmaninstitute.org/about/how-we-think/classical-liberalism-vs-modern-liberalism-and-modern-conservatism/ |website=Goodman Institute |access-date=2 January 2022}}</ref> Additionally, in the United States, classical liberalism is considered closely tied to, or synonymous with, ].<ref>{{Cite web |date=2023-04-06 |title=Libertarianism vs. Classical Liberalism: Is there a Difference? |url=https://reason.com/volokh/2023/04/06/libertarianism-vs-classical-liberalism-is-there-a-difference/ |access-date=2023-09-22 |website=Reason.com |language=en-US}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Klein |first=Daniel B. |date=2017-05-03 |title=Libertarianism and Classical Liberalism: A Short Introduction {{!}} Daniel B. Klein |url=https://fee.org/articles/libertarianism-and-classical-liberalism-a-short-introduction/ |access-date=2022-03-08 |website=fee.org |language=en}}</ref> | |||

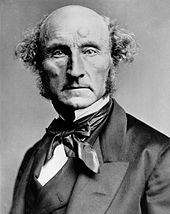

| :* ''']''', also known as '''new liberalism''' (not to be confused with 'neoliberalism') and '''reform liberalism''', arose in the late 19th century in many developed countries, influenced by the utilitarianism of ] and ]. Generally speaking, social liberals support free trade and a market-based economy in which the basic needs of all individuals are met. Furthermore, ] ideas are commonly advocated by social liberals, based on the idea that social practices ought to be continuously adapted in such a manner as to benefit the substantive freedom of all members of society. According to the tenets of this form of liberalism, as explained by writers such as ] and ], since individuals are the basis of society, all individuals should have access to basic necessities of fulfillment, such as education, economic opportunity, and protection from harmful macro-events beyond their control. To social liberals, these benefits are considered rights. ; this concept of ] is qualitatively different from the emphasis that economic liberals place on ]. Social liberals believe that in order for all people to have ] liberty, the provision of basic necessities to all citizens ought to be ensured by the political community through means such as taxation, towards ends such as ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| == Philosophy == | |||

| Social liberalism advocates some restrictions on matters that economic liberals view as fundamental rights. For example, social liberals may favor ], which classical liberals view as violating of the ]. Social liberals argue that power disparities cause contracts to favor the rich. To which economic liberals reply, "Then don't sign." Of course, if a group did indeed refuse to "sign", as in a ], the voluntary, mutual withholding of labor from an employer, economic liberals have employed--at least on a historical basis--totalitarian means, such as armed government soldiers to use force and coercion upon workers to "urge" them to "sign"; what is good for the goose is not good for the gander, apparently. (See, for example, the ], the ], etc.) | |||

| Liberalism—both as a political current and an intellectual tradition—is mostly a modern phenomenon that started in the 17th century, although some liberal philosophical ideas had precursors in ] and ].<ref name="BevirSAGE"/><ref name="FungCambridge"/> The ] ] praised "the idea of a polity administered with regard to equal rights and equal freedom of speech, and the idea of a kingly government which respects most of all the freedom of the governed".<ref>Antoninus, p. 3.</ref> Scholars have also recognised many principles familiar to contemporary liberals in the works of several ] and the ''Funeral Oration'' by ].<ref name="Young, pp. 25–6">{{Harvnb|Young|2002|pp=25–26}}.</ref> Liberal philosophy is the culmination of an extensive intellectual tradition that has examined and popularized some of the modern world's most important and controversial principles. Its immense scholarly output has been characterized as containing "richness and diversity", but that diversity often has meant that liberalism comes in different formulations and presents a challenge to anyone looking for a clear definition.<ref name="Young, p. 24">{{Harvnb|Young|2002|p=24}}.</ref> | |||

| === Major themes === | |||

| The struggle between ] and ] is almost as old as the idea of freedom itself. ], writing about ] (c. 639 – c. 559 BCE), the lawgiver of ancient Athens, wrote: | |||

| {{individualism sidebar|philosophies}} | |||

| {{cquote|The remission of debts was peculiar to Solon; it was his great means for confirming the citizens' liberty; for a mere law to give all men equal rights is but useless, if the poor must sacrifice those rights to their debts, and, in the very seats and sanctuaries of equality, the courts of justice, the offices of state, and the public discussions, be more than anywhere at the beck and bidding of the rich.}} | |||

| Although all liberal doctrines possess a common heritage, scholars frequently assume that those doctrines contain "separate and often contradictory streams of thought".<ref name="Young, p. 24"/> The objectives of ] have differed across various times, cultures and continents. The diversity of liberalism can be gleaned from the numerous qualifiers that liberal thinkers and movements have attached to the term "liberalism", including ], ], ], ], the ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]al, to name a few.<ref>{{Harvnb|Young|2002|p=25}}.</ref> Despite these variations, liberal thought does exhibit a few definite and fundamental conceptions. | |||

| Political philosopher ] identified the common strands in liberal thought as ], egalitarian, ] and ]. The individualist element avers the ethical primacy of the human being against the pressures of social ]; the egalitarian element assigns the same ] worth and status to all individuals; the meliorist element asserts that successive generations can improve their sociopolitical arrangements, and the universalist element affirms the moral unity of the human species and marginalises local ] differences.<ref name="Gray, p. xii">Gray, p. xii.</ref> The meliorist element has been the subject of much controversy, defended by thinkers such as ], who believed in human progress, while suffering criticism by thinkers such as ], who instead believed that human attempts to improve themselves through social ] would fail.<ref>Wolfe, pp. 33–36.</ref> | |||

| All forms of liberalism claim to protect freedom. They disagree only about the true meaning of freedom. Liberalism is so widespread in the modern world that most Western nations at least pay lip service to individual liberty as the basis for society. | |||

| The liberal philosophical tradition has searched for validation and justification through several intellectual projects. The moral and political suppositions of liberalism have been based on traditions such as natural rights and ], although sometimes liberals even request support from scientific and religious circles.<ref name="Gray, p. xii"/> Through all these strands and traditions, scholars have identified the following major common facets of liberal thought: | |||

| === Comparative influences === | |||

| Early ] thinkers contrasted liberalism with the authoritarianism of the ], ], ] and the ]. Later, as more radical philosophers articulated their thoughts in the course of the ] and throughout the nineteenth century, liberalism defined itself in contrast to ] and ], although modern European liberal parties have often formed coalitions with ] parties. In the 20th century liberalism defined itself in opposition to ] and ]. Some modern liberals have rejected the classical ], which emphasizes neutrality and free trade, in favor of multilateral ] and ]. | |||

| * believing in equality and ] | |||

| Liberalism favors the limitation of government power. Extreme ] liberalism, as advocated by ], ], ], and ], is a radical form of liberalism called ] (no state at all) or ] (a minimal state, or sometimes called "the ].")<ref>The website of the labels this form as "Market Anarchism".</ref> Most liberals claim that a ] is necessary to protect rights, yet the meaning of "government" can range from simply a rights protection organization to a ] ]. Recently, liberalism has again come into conflict with those who seek a society ordered by religious values: radical ] often rejects liberal thought in its entirety, and radical Christian sects in Western liberal-democratic states{{ndash}} especially the US{{ndash}} often find their moral opinions coming into conflict with liberal laws and ideals. | |||

| * supporting private property and individual rights | |||

| * supporting the idea of limited constitutional government | |||

| * recognising the importance of related values such as ], ], autonomy, ], and ]<ref>{{Harvnb|Young|2002|p=45}}.</ref> | |||

| === Classical and modern === | |||

| ==Development of thought== | |||

| {{see also|Age of Enlightenment}} | |||

| ===Origins of thought=== | |||

| ] | |||

| The focus on liberty as an essential right of people within the polity has been repeatedly asserted throughout history. These include the conflicts between the ] and ] in ] and the struggles of ] city states against the ]. The ] of ] and ] had forms of elections, the rule of law, and pursuit of free enterprise through much of the 1400s until domination by outside powers in the 16th century. The Dutch resistance against (Spanish) Catholic oppression during the ] is often{{ndash}} despite its refusal to give freedom to Catholics{{ndash}} considered a predecessor of liberal values. Other precursors to liberalism include certain aspects of the '']'' and medieval ].<ref>{{citation|first=Antony T.|last=Sullivan|title=Istanbul Conference Traces Islamic Roots of Western Law, Society|journal=]|date=January-February 1997|page=36|url=http://www.washington-report.org/backissues/0197/9701036.htm|accessdate=2008-02-29}}</ref><ref> {{citation|last=Weeramantry|first=Judge Christopher G.|title=Justice Without Frontiers: Furthering Human Rights|year=1997|publisher=]|isbn=9041102418|page=134}}</ref> | |||

| ==== John Locke and Thomas Hobbes ==== | |||

| The modern ideology of liberalism can be traced back to the ] which challenged the authority of the ] during the ], and the Whigs of the ] in Great Britain, whose assertion of their right to choose their king can be seen as a precursor to claims of ]. However, movements generally labeled as truly "liberal" date from ], particularly the ] party in ], the '']'' in ], and the movement towards ] in ]. These movements opposed ], ], and various kinds of religious ] and ]. They were also the first to formulate the concepts of individual rights under the rule of law, as well as the importance of self-government through elected representatives. | |||

| {{See also|John Locke|Thomas Hobbes}} | |||

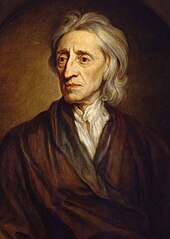

| ] philosophers are given credit for shaping liberal ideas. These ideas were first drawn together and systematized as a distinct ] by the English philosopher ], generally regarded as the father of modern liberalism.<ref name="Taverne, p. 18">Taverne, p. 18.</ref><ref name="Godwin et al., p. 12">Godwin et al., p. 12.</ref> ] attempted to determine the purpose and the justification of governing authority in post-civil war England. Employing the idea of a '']'' — a hypothetical war-like scenario prior to the state — he constructed the idea of a '']'' that individuals enter into to guarantee their security and, in so doing, form the State, concluding that only an ] would be fully able to sustain such security. Hobbes had developed the concept of the social contract, according to which individuals in the anarchic and brutal state of nature came together and voluntarily ceded some of their rights to an established state authority, which would create laws to regulate social interactions to mitigate or mediate conflicts and enforce justice. Whereas Hobbes advocated a strong monarchical commonwealth (the ]), Locke developed the then-radical notion that government acquires ], which has to be constantly present for the government to remain ].<ref>Copleston, Frederick. ''A History of Philosophy: Volume V''. New York: Doubleday, 1959. {{ISBN|0-385-47042-8}} pp. 39–41.</ref> While adopting Hobbes's idea of a state of nature and social contract, Locke nevertheless argued that when the monarch becomes a ], it violates the social contract, which protects life, liberty and property as a natural right. He concluded that the people have a right to overthrow a tyrant. By placing the security of life, liberty and property as the supreme value of law and authority, Locke formulated the basis of liberalism based on social contract theory. To these early enlightenment thinkers, securing the essential amenities of life—] and ]—required forming a "sovereign" authority with universal jurisdiction.<ref>{{Harvnb|Young|2002|pp=30–31}}</ref> | |||

| His influential '']'' (1690), the foundational text of liberal ideology, outlined his major ideas. Once humans moved out of their ] and formed ], Locke argued, "that which begins and actually constitutes any ] is nothing but the consent of any number of freemen capable of a majority to unite and incorporate into such a society. And this is that, and that only, which did or could give beginning to any lawful government in the world".<ref name="Locke Two Treatises 1947">{{cite book|last=Locke|first=John|author-link=John Locke|title=Two Treatises of Government|url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.503178/page/n5/mode/2up|year=1947|publisher=Hafner Publishing Company|location=New York}}</ref>{{rp|170}} The stringent insistence that lawful government did not have a ] basis was a sharp break with the dominant theories of governance, which advocated the divine right of kings<ref>Forster, p. 219.</ref> and echoed the earlier thought of ]. Dr John Zvesper described this new thinking: "In the liberal understanding, there are no citizens within the regime who can claim to rule by natural or supernatural right, without the consent of the governed".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Zvesper |first=Dr John |title=Nature and Liberty |date=4 March 1993 |publisher=] |isbn=9780415089234 |pages=93 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| The definitive break with the past was the conception that free individuals could form the foundation for a stable society. This idea is generally dated from the work of ] (1632-1704), whose '']'' established two fundamental liberal ideas: economic liberty, meaning the right to have and use property, and intellectual liberty, including freedom of conscience, which he expounded in '']'' (1689). However, he did not extend his views on religious freedom to ]s . Locke developed further the earlier idea of ], which he saw as "life, liberty and property". His "natural rights theory" was the distant forerunner of the modern conception of ]. However, to Locke, property was more important than the right to participate in government and public decision-making: he did not endorse ], because he feared that giving power to the people would erode the sanctity of private property. Nevertheless, the idea of natural rights played a key role in providing the ideological justification for the ] and the ]. | |||

| Locke had other intellectual opponents besides Hobbes. In the ''First Treatise'', Locke aimed his arguments first and foremost at one of the doyens of 17th-century English conservative philosophy: ]. Filmer's ''Patriarcha'' (1680) argued for the ] by appealing to ] teaching, claiming that the authority granted to ] by ] gave successors of Adam in the male line of descent a right of dominion over all other humans and creatures in the world.<ref>Copleston, Frederick. ''A History of Philosophy: Volume V''. New York: Doubleday, 1959. {{ISBN|0-385-47042-8}}, p. 33.</ref> However, Locke disagreed so thoroughly and obsessively with Filmer that the ''First Treatise'' is almost a sentence-by-sentence refutation of ''Patriarcha''. Reinforcing his respect for consensus, Locke argued that "conjugal society is made up by a voluntary compact between men and women".<ref name="Kerber 1976">{{cite journal|last=Kerber|first=Linda|author-link = Linda Kerber|year=1976|title=The Republican Mother: Women and the Enlightenment-An American Perspective|journal=American Quarterly|volume=28|issue=2|doi=10.2307/2712349|jstor=2712349|pages=187–205}}</ref> Locke maintained that the grant of dominion in ] was not to ], as Filmer believed, but to humans over animals.<ref name="Kerber 1976"/> Locke was not a ] by modern standards, but the first major liberal thinker in history accomplished an equally major task on the road to making the world more pluralistic: integrating women into ].<ref name="Kerber 1976"/> | |||

| ] | |||

| On the European continent, the doctrine of laws restraining even monarchs was expounded by ], whose '']'' argues that "Better is it to say, that the government most conformable to nature is that which best agrees with the humour and disposition of the people in whose favour it is established," rather than accept as natural the mere rule of force. Following in his footsteps, political economist ] and ] were ardent exponents of the "harmonies" of the market, and in all probability it was they who coined the term '']''. This evolved into the ], and to the ] of ]. | |||

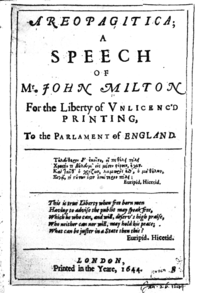

| ]'s '']'' (1644) argued for the importance of ].]] | |||

| The late French enlightenment saw two figures who would have tremendous influence on later liberal thought: ] who argued that the French should adopt ], and disestablish the ''Second Estate'', and Rousseau who argued for a natural freedom for mankind. Both argued, in different forms, for changes in political and social arrangements based around the idea that society can restrain a natural human liberty, but not obliterate its nature. For Voltaire the concept was more intellectual, for Rousseau, it was related to intrinsic natural rights, perhaps related to the ideas of ]. | |||

| Locke also originated the concept of the ].<ref name=AFP>Feldman, Noah (2005). ''Divided by God''. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, p. 29 ("It took ] to translate the demand for liberty of conscience into a systematic argument for distinguishing the realm of government from the realm of religion.")</ref> Based on the social contract principle, Locke argued that the government lacked authority in the realm of individual ], as this was something ] people could not cede to the government for it or others to control. For Locke, this created a natural right to the liberty of conscience, which he argued must remain protected from any government authority.<ref>Feldman, Noah (2005). ''Divided by God''. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, p. 29</ref> In his ''Letters Concerning Toleration'', he also formulated a general defence for ]. Three arguments are central: | |||

| # Earthly judges, the state in particular, and human beings generally, cannot dependably evaluate the truth claims of competing religious standpoints; | |||

| ]]] | |||

| # Even if they could, enforcing a single "]" would not have the desired effect because belief cannot be compelled by ]; | |||

| Rousseau also argued the importance of a concept that appears repeatedly in the history of liberal thought, namely, the social contract. He rooted this in the nature of the individual and asserted that each person knows their own interest best. His assertion that man is born free, but that education was sufficient to restrain him within society, rocked the monarchical society of his age. His assertion of an organic will of a nation argued for self-determination of peoples, again in contravention of established political practice. His ideas were a key element in the declaration of the ] in the French Revolution, and in the thinking of Americans such as ] and ]. In his view the unity of a state came from the concerted action of consent, or the "national will". This unity of action would allow states to exist without being chained to pre-existing social orders, such as aristocracy. | |||

| # Coercing ] would lead to more social disorder than allowing diversity.<ref>]. 1998. ''Historical Theology, An Introduction to the History of Christian Thought.'' Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. pp. 214–15.</ref> | |||

| Locke was also influenced by the liberal ideas of Presbyterian politician and poet ], who was a staunch advocate of freedom in all its forms.<ref>{{Citation | first = Heinrich | last = Bornkamm | language = de | contribution = Toleranz. In der Geschichte des Christentums | title = Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart | year = 1962}}, 3. Auflage, Band VI, col. 942</ref> Milton argued for ] as the only effective way of achieving broad ]. Rather than force a man's conscience, the government should recognise the persuasive force of the gospel.<ref>Hunter, William Bridges. ''A Milton Encyclopedia, Volume 8'' (East Brunswick, NJ: Associated University Presses, 1980). pp. 71, 72. {{ISBN|0-8387-1841-8}}.</ref> As assistant to ], Milton also drafted a constitution of the ] (''Agreement of the People''; 1647) that strongly stressed the equality of all humans as a consequence of democratic tendencies.<ref>{{Citation | first = W | last = Wertenbruch | contribution = Menschenrechte | title = Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart | language = de | place = Tübingen, DE | year = 1960}}, 3. Auflage, Band IV, col. 869</ref> In his '']'', Milton provided one of the first arguments for the importance of freedom of speech—"the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties". His central argument was that the individual could use reason to distinguish right from wrong. To exercise this right, everyone must have unlimited access to the ideas of his fellow men in "]", which will allow good arguments to prevail. | |||

| A main contributing group of thinkers whose work would become considered part of liberalism are those associated with the "]", including the writers ] and ], and the German ] philosopher ]. | |||

| In a natural state of affairs, liberals argued, humans were driven by the instincts of survival and ], and the only way to escape from such a dangerous existence was to form a common and supreme power capable of arbitrating between competing human desires.<ref name="Young 30">{{Harvnb|Young|2002|p=30}}.</ref> This power could be formed in the framework of a ] that allows individuals to make a voluntary social contract with the sovereign authority, transferring their natural rights to that authority in return for the protection of life, liberty and property.<ref name="Young 30"/> These early liberals often disagreed about the most appropriate form of government, but all believed that liberty was natural and its restriction needed strong justification.<ref name="Young 30" /> Liberals generally believed in limited government, although several liberal philosophers decried government outright, with ] writing, "government even in its best state is a necessary evil".<ref name="Young, p. 31">{{Harvnb|Young|2002|p=31}}.</ref> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ]'s contributions were many and varied, but most important was his assertion that fundamental rules of human behavior would overwhelm attempts to restrict or regulate them, in '']'', 1739-1740. One example of this is in his disparaging of ], and the accumulation of gold and silver. He argued that prices were related to the quantity of money, and that hoarding gold and issuing paper money would only lead to inflation. | |||

| ==== James Madison and Montesquieu ==== | |||

| Although Adam Smith is the most famous of the economic liberal thinkers, he was not without antecedents. The ] in France had proposed studying systematically political economy and the self organizing nature of markets. Benjamin Franklin wrote in favor of the freedom of American industry in 1750. In ] the period of liberty and parliamentary government from 1718 to 1772 produced a ] parliamentarian, ], who was one of the first to propose free trade and unregulated industry, in '']'', 1765. His impact has proven to be lasting particularly in the Nordic area, but it also had a powerful effect in later developments elsewhere. | |||

| As part of the project to limit the powers of government, liberal theorists such as ] and ] conceived the notion of ], a system designed to equally distribute governmental authority among the ], ] and ] branches.<ref name="Young, p. 31" /> Governments had to realise, liberals maintained, that legitimate government only exists with the ], so poor and improper governance gave the people the authority to overthrow the ruling order through all possible means, even through outright violence and ], if needed.<ref>{{Harvnb|Young|2002|p=32}}.</ref> Contemporary liberals, heavily influenced by social liberalism, have supported limited ] while advocating for ] and provisions to ensure equal rights. Modern liberals claim that formal or official guarantees of individual rights are irrelevant when individuals lack the material means to benefit from those rights and call for a ] in the administration of economic affairs.<ref>{{Harvnb|Young|2002|pp=32–33}}.</ref> Early liberals also laid the groundwork for the separation of church and state. As heirs of the Enlightenment, liberals believed that any given social and political order emanated ], not from ].<ref name="Gould, p. 4">Gould, p. 4.</ref> Many liberals were openly hostile to ] but most concentrated their opposition to the union of religious and political authority, arguing that faith could prosper independently without official sponsorship or administration by the state.<ref name="Gould, p. 4"/> | |||

| Beyond identifying a clear role for government in modern society, liberals have also argued over the meaning and nature of the most important principle in liberal philosophy: liberty. From the 17th century until the 19th century, liberals (from ] to ]) conceptualised liberty as the absence of interference from government and other individuals, claiming that all people should have the freedom to develop their unique abilities and capacities without being sabotaged by others.<ref name="Young, p. 33">{{Harvnb|Young|2002|p=33}}.</ref> Mill's '']'' (1859), one of the classic texts in liberal philosophy, proclaimed, "the only freedom which deserves the name, is that of pursuing our own good in our own way".<ref name="Young, p. 33"/> Support for ''laissez-faire'' ] is often associated with this principle, with ] arguing in '']'' (1944) that reliance on free markets would preclude totalitarian control by the state.<ref>Wolfe, p. 74.</ref> | |||

| The Scotsman ] (1723–1790) expounded the theory that individuals could structure both moral and economic life without direction from the state, and that nations would be strongest when their citizens were free to follow their own initiative. He advocated an end to feudal and mercantile regulations, to state-granted monopolies and patents, and he promulgated "]" government. In '']'', 1759, he developed a theory of motivation that tried to reconcile human self-interest and an unregulated social order. In '']'', 1776, he argued that the market, under certain conditions, would naturally regulate itself and would produce more than the heavily restricted markets that were the norm at the time. He assigned to government the role of taking on tasks which could not be entrusted to the profit motive, such as preventing individuals from using force or fraud to disrupt competition, trade, or production. His theory of taxation was that governments should levy taxes only in ways which did not harm the economy, and that "The subjects of every state ought to contribute towards the support of the government, as nearly as possible, in proportion to their respective abilities; that is, in proportion to the revenue which they respectively enjoy under the protection of the state." He agreed with Hume that capital, not gold, is the wealth of a nation. | |||

| ==== Coppet Group and Benjamin Constant ==== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] was strongly influenced by Hume's empiricism and rationalism. His most important contributions to liberal thinking are in the realm of ethics, particularly his assertion of the ]. Kant argued that received systems of reason and morals were subordinate to natural law, and that, therefore, attempts to stifle this basic law would meet with failure. His idealism would become increasingly influential, since it asserted that there were fundamental truths upon which systems of knowledge could be based. This meshed well with the ideas of the English Enlightenment about natural rights. | |||

| The development into maturity of modern classical in contrast to ancient liberalism took place before and soon after the French Revolution. One of the historic centres of this development was at ] near ], where the eponymous ] gathered under the aegis of the exiled writer and ], ], in the period between the establishment of ]'s First Empire (1804) and the ] of 1814–1815.<ref>{{cite journal |last1= Tenenbaum |first1= Susan |title= The Coppet Circle. Literary Criticism as Political Discourse |journal= History of Political Thought |date= 1980 |volume= 1 |issue= 2 |pages= 453–473}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1= Lefevere |first1= Andre |title= Translation, Rewriting, and the Manipulation of Literary Fame |date= 2016 |publisher= Taylor & Francis |page= 109}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1= Fairweather |first1= Maria |title= Madame de Stael |date= 2013 |publisher= Little, Brown Book Group}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1= Hofmann |first1= Etienne |last2= Rosset |first2= François |title= Le Groupe de Coppet. Une constellation d'intellectuels européens |date= 2005 |publisher= Presses polytechniques et universitaires romandes}}</ref> The unprecedented concentration of European thinkers who met there was to have a considerable influence on the development of nineteenth-century liberalism and, incidentally, ].<ref>{{cite book |last1= Jaume |first1= Lucien |title= Coppet, creuset de l'esprit libéral: Les idées politiques et constitutionnelles du Groupe de Madame de Staël |date= 2000 |publisher= Presses Universitaires d'Aix-Marseille |page= 10}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1= Delon |first1= Michel |editor1-last= Francillon |editor1-first= Roger |title= Histoire de la littérature en Suisse romande t.1 |date= 1996 |publisher= Payot |chapter= Le Groupe de Coppet}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=The Home of French Liberalism|publisher=The Coppet Institute|url=https://coppetinstitute.org|access-date=2020-02-20}}</ref> They included ], ], ], ], ], ], ], Sir ], ] and ].<ref>{{cite book|title=Making Way for Genius: The Aspiring Self in France from the Old Regime to the New|author=Kete, Kathleen|publisher= Yale University Press|date= 2012|isbn= 978-0-300-17482-3}}</ref> | |||

| ], a Franco-Swiss political activist and theorist]] | |||

| === Revolutionary ideology === | |||

| Among them was also one of the first thinkers to go by the name of "liberal", the ]-educated Swiss Protestant, ], who looked to the United Kingdom rather than to ] for a practical model of freedom in a large mercantile society. He distinguished between the "Liberty of the Ancients" and the "Liberty of the Moderns".<ref name="AncientModern">{{cite web |url=http://www.uark.edu/depts/comminfo/cambridge/ancients.html |title=Constant, Benjamin, 1988, 'The Liberty of the Ancients Compared with that of the Moderns' (1819), in The Political Writings of Benjamin Constant, ed. Biancamaria Fontana, Cambridge, pp. 309–28 |publisher=Uark.edu |access-date=2013-09-17 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://archive.today/20120805184450/http://www.uark.edu/depts/comminfo/cambridge/ancients.html |archive-date=5 August 2012 |df=dmy-all}}</ref> The Liberty of the Ancients was a participatory ] liberty,<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Bertholet |first=Auguste |date=2021 |title=Constant, Sismondi et la Pologne |url=https://www.slatkine.com/fr/editions-slatkine/75250-book-05077807-3600120175625.html |journal=Annales Benjamin Constant |volume=46 |pages=65–76}}</ref> which gave the citizens the right to influence politics directly through debates and votes in the public assembly.<ref name="AncientModern"/> In order to support this degree of participation, citizenship was a burdensome moral obligation requiring a considerable investment of time and energy. Generally, this required a sub-group of slaves to do much of the productive work, leaving citizens free to deliberate on public affairs. Ancient Liberty was also limited to relatively small and homogenous male societies, where they could congregate in one place to transact public affairs.<ref name="AncientModern"/> | |||

| These thinkers, however, worked within the political framework of monarchies and in societies in which the class system and an established church were the norm. Although the earlier ] had resulted in the republican ] between 1649 and 1660, the idea that ordinary human beings could structure their own affairs had been suppressed with ] and then remained theoretical until the ] and ] Revolutions. (The ] of 1688 is often cited as a precedent, but it replaced one monarch with another monarch. It had, however, weakened the power of the monarch and strengthened the ] which had refused to accept the ] succession.) The republican ideas of ] influenced these two late 18th century revolutions which became the examples which later ] liberals followed. Both used as their philosophical justification the ] or the rights given, in the words of ], by "Nature and Nature's God". They rejected both tradition and established power. | |||

| In contrast, the Liberty of the Moderns was based on the possession of ], the rule of law, and freedom from excessive state interference. Direct participation would be limited: a necessary consequence of the size of modern states and the inevitable result of creating a mercantile society where there were no slaves, but almost everybody had to earn a living through work. Instead, the voters would elect ] who would deliberate in Parliament on the people's behalf and would save citizens from daily political involvement.<ref name="AncientModern"/> The importance of Constant's writings on the liberty of the ancients and that of the "moderns" has informed the understanding of liberalism, as has his critique of the French Revolution.<ref>{{cite book|title=Benjamin Constant, Madame de Staël et le Groupe de Coppet: Actes du Deuxième Congrès de Lausanne à l'occasion du 150e anniversaire de la mort de Benjamin Constant Et Du Troisième Colloque de Coppet, 15–19 juilliet 1980|editor=Hofmann, Étienne|publisher=Oxford, The ] and Lausanne, Institut Benjamin Constant|date=1982|language=fr|isbn= 0-7294-0280-0}}</ref> The British philosopher and historian of ideas, Sir ], has pointed to the debt owed to Constant.<ref>{{cite book|author=Rosen, Frederick |title=Classical Utilitarianism from Hume to Mill |date=2005 |publisher=Routledge |page=251}} According to Berlin, the most eloquent of all defenders of freedom and privacy Benjamin Constant, who had not forgotten the Jacobin dictatorship.</ref> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ], ], and ] would be instrumental in persuading their fellow Americans to revolt in the name of ''life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness'', echoing Locke, but with one important change (opposed by Alexander Hamilton). Jefferson replaced Locke's word "property" by "the pursuit of happiness". The "American Experiment" would be in favor of democratic government and individual liberty. | |||

| ==== British liberalism ==== | |||

| ] was prominent among the next generation of political theorists in America, arguing that in a republic self-government depended on setting "interest against interest", thus providing protection for the rights of minorities, particularly economic minorities. The American ] instituted a system of checks and balances: federal government balanced against states' rights; executive, legislative, and judicial branches; and a ]. The goal was to insure liberty by preventing the concentration of power in the hands of any one man. Standing armies were held in suspicion, and the belief was that the ] would be enough for defense, along with a ] maintained by the government for the purpose of trade. | |||

| ] was based on core concepts such as ], ], '']'' government with minimal intervention and taxation and a ]. Classical liberals were committed to individualism, liberty and equal rights. Writers such as ] and ] opposed aristocratic privilege and property, which they saw as an impediment to developing a class of ] farmers.<ref name="Vincent, pp. 29–30">{{cite book|last=Vincent|first=Andrew|title=Modern Political Ideologies|url=https://archive.org/details/modernpoliticali0000vinc/mode/2up?view=theater|url-access = registration |year=1992|publisher=Blackwell|location=Oxford, UK, & Cambridge, US|isbn=0-631-16451-0|pages=29–30}}</ref> | |||

| ], an influential ] who established in ''Prolegomena to Ethics'' (1884) the first major foundations for what later became known as ] and in a few years, his ideas became the ] of the ] in ], precipitating the rise of ] and the modern ]]] | |||

| ] | |||

| Beginning in the late 19th century, a new conception of liberty entered the liberal intellectual arena. This new kind of liberty became known as ] to distinguish it from the prior ], and it was first developed by ] ]. Green rejected the idea that humans were driven solely by ], emphasising instead the complex circumstances involved in the evolution of our ].<ref name="Adams 1998">{{cite book|last=Adams|first=Ian|title=Ideology and Politics in Britain Today|series = Politics Today | url=https://archive.org/details/ideologypolitics0000adam/mode/2up?view=theater|url-access = registration| chapter-url = https://archive.org/details/ideologypolitics0000adam/page/52/mode/2up?view=theater | chapter-url-access = registration|year=1998|publisher=Manchester University Press|location=Manchester & New York|isbn=0-7190-5055-3|chapter=New Liberals to Liberal Democrats}}</ref>{{rp|54–55}} In a very profound step for the future of modern liberalism, he also tasked society and political institutions with the enhancement of individual freedom and identity and the development of moral character, will and reason and the state to create the conditions that allow for the above, allowing genuine ].<ref name="Adams 1998"/>{{rp|54–55}} Foreshadowing the new liberty as the freedom to act rather than to avoid suffering from the acts of others, Green wrote the following: {{blockquote|If it were ever reasonable to wish that the usage of words had been other than it has been ... one might be inclined to wish that the term 'freedom' had been confined to the ... power to do what one wills.<ref>Wempe, p. 123.</ref>|sign=|source=}} | |||

| The French Revolution overthrew monarch, ] social order, and an established ]. These revolutionaries were more vehement and less compromising than those in America. A key moment in the French Revolution was the declaration by the representatives of the ] that they were the "National Assembly" and had the right to speak for the French people. During the first few years the revolution was guided by liberal ideas, but the transition from revolt to stability was to prove more difficult than the similar American transition. In addition to native Enlightenment traditions, some leaders of the early phase of the revolution, such as ], had fought in the U.S. War of Independence against Britain, and brought home Anglo-American liberal ideas. Later, under the leadership of ], a ] faction greatly centralized power and dispensed with most aspects of ], resulting in the ]. Instead of an ultimately republican constitution, ] rose from Director, to Consul, to Emperor. On his death bed he confessed "They wanted another Washington", meaning a man who could militarily establish a new state, without desiring a dynasty. Nevertheless, the French Revolution would go farther than the American Revolution in establishing liberal ideals with such policies as universal male ], national citizenship, and a far reaching "]", paralleling the American ]. One of the side-effects of Napoleon's military campaigns was to carry these ideas throughout Europe. | |||

| Rather than previous liberal conceptions viewing society as populated by selfish individuals, Green viewed society as an organic whole in which all individuals have a ] to promote the ].<ref name="Adams 1998"/>{{rp|55}} His ideas spread rapidly and were developed by other thinkers such as ] and ]. In a few years, this ''New Liberalism'' had become the essential social and political programme of the Liberal Party in Britain,<ref name="Adams 1998"/>{{rp|58}} and it would encircle much of the world in the 20th century. In addition to examining negative and positive liberty, liberals have tried to understand the proper relationship between liberty and democracy. As they struggled to expand ], liberals increasingly understood that people left out of the ] were liable to the "]", a concept explained in Mill's ''On Liberty'' and '']'' (1835) by ].<ref name="Young, p. 36">{{Harvnb|Young|2002|p=36}}.</ref> As a response, liberals began demanding proper safeguards to thwart majorities in their attempts at suppressing the ].<ref name="Young, p. 36"/> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The examples of United States and France were followed in many other countries. The usurpation of the Spanish monarchy by Napoleon's forces in 1808 led to autonomist and independence movements across Latin America, which often turned to liberal ideas as alternatives to the monarchical-clerical corporatism of the colonial era. Movements such as that led by ] in the Andean countries aspired to constitutional government, individual rights, and free trade. The struggle between liberals and corporatist conservatives continued for the rest of the century in Latin America, with ] liberals like ] of Mexico attacking the traditional role of the ]. | |||