| Revision as of 11:44, 21 June 2013 editJytdog (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers187,951 editsm →Europe: ref fix← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 12:24, 10 December 2024 edit undoInternetArchiveBot (talk | contribs)Bots, Pending changes reviewers5,379,716 edits Rescuing 4 sources and tagging 0 as dead.) #IABot (v2.0.9.5) (Pancho507 - 22019 | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Food complying with organic farming standards}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| {{about|food that complies with the standards of organic farming|food advertised as "natural"|Natural food}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=September 2022}} | |||

| ] in Argentina]] | |||

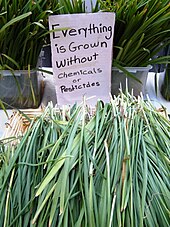

| '''Organic food''', '''ecological food''', or '''biological food''' are foods and ] produced by methods complying with the standards of ]. Standards vary worldwide, but organic farming features practices that cycle resources, promote ecological balance, and conserve ]. Organizations regulating organic products may restrict the use of certain ]s and ]s in the farming methods used to produce such products. Organic foods are typically not processed using ], industrial solvents, or synthetic ].<ref name="irr" /> | |||

| '''Organic foods''' are foods that are produced using methods of ] – that do not involve modern synthetic inputs such as synthetic ] and ]. Organic foods are also not processed using ], industrial solvents, or chemical ].<ref>{{Cite book|editors=Allen, Gary J. & Albala, Ken|title=The Business of Food: Encyclopedia of the Food and Drink Industries|publisher=ABC-CLIO|year=2007|isbn=978-0-313-33725-3|page=288|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=gNzmOUyiFRAC&pg=PA288}}</ref> The organic farming movement arose in the 1940s in response to the ] of ] known as the ].<ref name=Drinkwater>{{cite book|author=Drinkwater, Laurie E.|chapter=Ecological Knowledge: Foundation for Sustainable Organic Agriculture|editor=Francis, Charles|title=Organic farming: the ecological system|publisher=ASA-CSSA-SSSA|year=2009|isbn=978-0-89118-173-6|page=19|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=8HMfbQpNq60C&pg=PA19}}</ref> Organic food production is a heavily regulated industry, distinct from ]. Currently, the European Union, the United States, Canada, Japan and many other countries require producers to obtain ] in order to market food as organic within their borders. In the context of these regulations, organic food is food produced in a way that complies with organic standards set by national governments and international organizations. | |||

| In the 21st century, the ], the United States, Canada, Mexico, Japan, and many other countries require producers to obtain ] to market their food as ''organic''. Although the produce of ]s may actually be organic, selling food with an organic label is regulated by governmental ] authorities, such as the ] of the ] (USDA)<ref name="USDANOP">{{cite web | title=National Organic Program | publisher=Agricultural Marketing Service, US Department of Agriculture | date=12 December 2018 | url=https://www.ams.usda.gov/about-ams/programs-offices/national-organic-program | access-date=25 February 2019}}</ref> or the ] (EC).<ref name="EU Commission">{{cite web|url= http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/organic/organic-farming/what-is-organic-farming/organic-certification/index_en.htm|title=Organic certification|publisher=European Commission: Agriculture and Rural Development|date=2014|access-date=10 December 2014}}</ref> | |||

| Evidence on substantial differences between organic food and conventional food is insufficient to make claims that organic food is safer or healthier than conventional food.<ref name="Blair1">Blair, Robert. (2012). Organic Production and Food Quality: A Down to Earth Analysis. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, UK. ISBN 978-0-8138-1217-5</ref><ref name=MagkosSafety2006>Magkos F et al (2006) Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 46(1): 23–56 | pmid=16403682</ref><ref name=Bourn>{{cite journal |author=Bourn D, Prescott J |title=A comparison of the nutritional value, sensory qualities, and food safety of organically and conventionally produced foods |journal=Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr |volume=42 |issue=1 |pages=1–34 |year=2002 |month=January |pmid=11833635 |doi= 10.1080/10408690290825439|url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11833635}}</ref><ref name=Smith-Spangler2012>{{cite journal|last=Smith-Spangler|first=C|coauthors=Brandeau, ML; Hunter, GE; Bavinger, JC; Pearson, M; Eschbach, PJ; Sundaram, V; Liu, H; Schirmer, P; Stave, C; Olkin, I; Bravata, DM|title=Are organic foods safer or healthier than conventional alternatives?: a systematic review.|journal=Annals of Internal Medicine|date=September 4, 2012|volume=157|issue=5|pages=348–366|pmid=22944875 |url=http://annals.org/article.aspx?articleid=1355685}}</ref><ref name=Dangour2009>Dangour AD et al (2009) The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 92(1):203–210</ref><ref name=FSA/><ref name=Williams2002>{{cite journal|last=Williams|first=Christine M.|title=Nutritional quality of organic food: shades of grey or shades of green?|journal=Proceedings of the Nutrition Society|year=2002|month=February|volume=61|issue=1|pages=19–24|doi=10.1079/PNS2001126|url=http://journals.cambridge.org/production/action/cjoGetFulltext?fulltextid=803836|format=PDF}}</ref> With respect to taste, the evidence is also insufficient to make scientific claims that organic food tastes better.<ref name=Bourn/><ref name=Blair1/> | |||

| From an environmental perspective, ], ], and the use of ] in ] may negatively affect ]s, ],<ref name="10.1016/bs.agron.2015.12.003">{{cite journal |last1=Reeve |first1=J. R. |last2=Hoagland |first2=L. A. |last3=Villalba |first3=J. J. |last4=Carr |first4=P. M. |last5=Atucha |first5=A. |last6=Cambardella |first6=C. |last7=Davis |first7=D. R. |last8=Delate |first8=K. |title=Chapter Six – Organic Farming, Soil Health, and Food Quality: Considering Possible Links |journal=Advances in Agronomy |date=1 January 2016 |volume=137 |pages=319–367 |doi=10.1016/bs.agron.2015.12.003 |publisher=Academic Press |language=en}}</ref><ref name="10.1007/s13165-019-00275-1">{{cite journal |last1=Tully |first1=Katherine L. |last2=McAskill |first2=Cullen |title=Promoting soil health in organically managed systems: a review |journal=Organic Agriculture |date=1 September 2020 |volume=10 |issue=3 |pages=339–358 |doi=10.1007/s13165-019-00275-1 |bibcode=2020OrgAg..10..339T |s2cid=209429041 |language=en |issn=1879-4246}}</ref> ], ], and ] supplies. These environmental and health issues are intended to be minimized or avoided in organic farming.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Lowell|first=Vicki|title=Organic FAQs|url=https://ofrf.org/research/organic-faqs/|access-date=22 September 2020|website=Organic Farming Research Foundation|language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| ==Meaning and origin of the term== | |||

| {{Details|Organic farming|on the production of organic food}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Demand for organic foods is primarily driven by consumer concerns for personal health and the environment, such as the detrimental ].<ref name="Harvard">{{cite web | publisher=Harvard Health Publishing, Harvard Medical School | title=Should you go organic? | date=9 September 2015 | url=https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/should-you-go-organic | access-date=7 December 2022}}</ref> From the perspective of science and consumers, there is insufficient evidence in the ] and ] to support claims that organic food is either substantially ] or healthier to eat than conventional food.<ref name=Harvard/> | |||

| For the vast majority of its history, agriculture can be described as having been organic; only during the 20th century was a large supply of new chemicals introduced to the food supply.<ref></ref> The organic farming movement arose in the 1940s in response to the ] of ] known as the ].<ref name=Drinkwater /> | |||

| Organic agriculture has higher production costs and lower yields, higher labor costs, and higher consumer prices as compared to ] methods. | |||

| ==Meaning, history and origin of the term== | |||

| In 1939, ] coined the term ''organic farming'' in his book ''Look to the Land'' (1940), out of his conception of "the farm as organism," to describe a holistic, ecologically balanced approach to farming—in contrast to what he called ''chemical farming'', which relied on "imported fertility" and "cannot be self-sufficient nor an organic whole."<ref>{{cite journal|author=John, Paull|title=The Farm as Organism: The Foundational Idea of Organic Agriculture|journal = Elementals: Journal of Bio-Dynamics Tasmania|volume=80|year=2006|pages=14–18|url=http://orgprints.org/10138/01/10138.pdf|format=PDF}}</ref> This is different from the scientific use of the term "organic," to refer to ], especially those involved in the chemistry of life. This class of molecules includes everything likely to be considered edible, and include most pesticides and toxins too, therefore the term "organic" and, especially, the term "inorganic" (sometimes wrongly used as a contrast by the popular press) are both technically inaccurate and completely inappropriate when applied to farming, the production of food, and to foodstuffs themselves. | |||

| {{further|topic=the production of organic food|Organic farming}} | |||

| {{see also|History of organic farming}} | |||

| For the vast majority of its history, agriculture can be described as having been organic; only during the 20th century was a large supply of new products, generally deemed not organic, introduced into food production.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/teaching-the-food-system/curriculum/_pdf/History_of_Food-Background.pdf |title=History of food, p. 3 |website=Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304114214/http://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/teaching-the-food-system/curriculum/_pdf/History_of_Food-Background.pdf |archive-date=4 March 2016}}</ref>{{Failed verification|date=December 2022}} The organic farming movement arose in the 1940s in response to the industrialization of agriculture.<ref name=Drinkwater>{{cite book |author=Drinkwater, Laurie E. |chapter=Ecological Knowledge: Foundation for Sustainable Organic Agriculture |editor=Francis, Charles |title=Organic farming: the ecological system |publisher=ASA-CSSA-SSSA |year=2009 |isbn=978-0-89118-173-6 |page=19 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8HMfbQpNq60C&pg=PA19}}</ref> | |||

| Early consumers interested in organic food would look for non-chemically treated, non-use of unapproved pesticides, fresh or minimally processed food. They mostly had to buy directly from growers: "Know your farmer, know your food" was the motto.{{citation needed|date=March 2013}} Personal definitions of what constituted "organic" were developed through firsthand experience: by talking to farmers, seeing farm conditions, and farming activities. Small farms grew vegetables (and raised livestock) using ] practices, with or without certification, and the individual consumer monitored.{{citation needed|date=March 2013}}] Small specialty health food stores and co-operatives were instrumental to bringing organic food to a wider audience.{{citation needed|date=March 2013}} As demand for organic foods continued to increase, high volume sales through mass outlets such as supermarkets rapidly replaced the direct farmer connection.{{citation needed|date=March 2013}} Today there is no limit to organic farm sizes and many large corporate farms currently have an organic division. However, for supermarket consumers, food production is not easily observable, and product labeling, like "certified organic", is relied on. Government regulations and third-party inspectors are looked to for assurance.{{citation needed|date=March 2013}} | |||

| In 1939, ] coined the term ''organic farming'' in his book ''Look to the Land'' (1940), out of his conception of "the farm as organism", to describe a holistic, ecologically balanced approach to farming—in contrast to what he called ''chemical farming'', which relied on "imported fertility" and "cannot be self-sufficient nor an organic whole".<ref>{{cite journal |author=John, Paull |title=The Farm as Organism: The Foundational Idea of Organic Agriculture |journal = Elementals: Journal of Bio-Dynamics Tasmania |volume=80 |year=2006 |pages=14–18 |url=http://orgprints.org/10138/01/10138.pdf}}</ref> Early soil scientists also described the differences in soil composition when ] were used as "organic", because they contain ], whereas ] and ] nitrogen do not. Their respective use affects ] content of soil.<ref name=Betteshanger>Paull, John (2011) , ''Journal of Organic Systems'', 2011, 6(2):13–26.</ref><ref>{{cite web |last1=Howard |first1=Sir Albert |title=Farming and Gardening for Health or Disease (The Soil and Health) |url=http://journeytoforever.org/farm_library/howardSH/SHtoc.html |website=Journey to forever online library |publisher=Faber and Faber Limited |access-date=18 August 2014}}</ref> This is different from the scientific use of the term "organic" in chemistry, which refers to ], especially those involved in the chemistry of life. This class of molecules includes everything likely to be considered edible, as well as most pesticides and toxins too, therefore the term "organic" and, especially, the term "inorganic" (sometimes wrongly used as a contrast by the popular press) as they apply to organic chemistry is an equivocation fallacy when applied to farming, the production of food, and to foodstuffs themselves. Properly used in this agricultural science context, "organic" refers to the methods grown and processed, not necessarily the chemical composition of the food. | |||

| ===Legal definition=== | |||

| ] (run by the USDA) is in charge of the legal definition of ''organic'' in the United States and does ].]] | |||

| Ideas that organic food could be healthier and better for the environment originated in the early days of the ] as a result of publications like the 1943 book ]<ref>{{cite web |last1=Balfour |first1=Lady Eve |title=Towards a Sustainable Agriculture—The Living Soil |url=http://www.soilandhealth.org/01aglibrary/010116Balfourspeech.html |publisher=IFOAM |access-date=20 August 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150224214556/http://www.soilandhealth.org/01aglibrary/010116Balfourspeech.html |archive-date=24 February 2015 |url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Lady Balfour |url=http://www.ifoam.org/en/lady-eve-balfour |website=IFOAM |access-date=21 August 2014}}</ref> and ''Farming and Gardening for Health or Disease'' (1945).<ref>{{cite web |last1=Howard |first1=Sir Albert |title=Farming and Gardening for Health or Disease (The Soil and Health) |url=http://journeytoforever.org/farm_library/howardSH/SH10.html |website=Journey to forever online library |publisher=Faber and Faber Limited |access-date=18 August 2014}}</ref> | |||

| In the industrial era, organic gardening reached a modest level of popularity in the United States in the 1950s. In the 1960s, environmentalists and the counterculture championed organic food, but it was only in the 1970s that a national marketplace for organic foods developed.<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UjEtDwAAQBAJ&q=whole+foods&pg=PT302 |title=From Head Shops to Whole Foods: The Rise and Fall of Activist Entrepreneurs |last=Davis |first=Joshua Clark |date=8 August 2017 |publisher=Columbia University Press |isbn=9780231543088 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Early consumers interested in organic food would look for non-chemically treated, non-use of unapproved pesticides, fresh or minimally processed food. They mostly had to buy directly from growers. Later, "Know your farmer, know your food" became the motto of a new initiative instituted by the USDA in September 2009.<ref>{{cite web |last=Philpott |first=Tom |title=Quick thoughts on the USDA's 'Know Your Farmer' program |url=http://grist.org/article/2009-09-16-quick-thoughts-on-the-usdas-know-your-farmer-program |website=Grist * A Beacon in the Smog |publisher=Grist Magazine, Inc. |access-date=28 January 2014 |date=17 September 2009}}</ref> Personal definitions of what constituted "organic" were developed through firsthand experience: by talking to farmers, seeing farm conditions, and farming activities. Small farms grew vegetables (and raised livestock) using ] practices, with or without certification, and the individual consumer monitored.{{citation needed|date=March 2013}} Small specialty health food stores and co-operatives were instrumental to bringing organic food to a wider audience.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Albala |first=Ken |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8_caCAAAQBAJ&q=health+food+stores+and+co-operatives+organic+food+to+wide+audience&pg=PA767 |title=The SAGE Encyclopedia of Food Issues |date=27 March 2015 |publisher=SAGE Publications |isbn=978-1-5063-1730-4 |language=en}}</ref> As demand for organic foods continued to increase, high-volume sales through mass outlets such as supermarkets rapidly replaced the direct farmer connection.{{citation needed|date=March 2013}} Today, many large corporate farms have an organic division. However, for supermarket consumers, food production is not easily observable, and product labeling, like "certified organic", is relied upon. Government regulations and third-party inspectors are looked to for assurance.<ref>{{Cite web |last=US EPA |first=OECA |date=24 July 2015 |title=Organic Farming |url=https://www.epa.gov/agriculture/organic-farming |access-date=22 September 2020 |website=US EPA |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| In the 1970s, interest in organic food grew with the rise of the ] and was also spurred by food-related health scares like the concerns about ] that arose in the mid-1980s.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Pollan |first1=Michael |title=The Omnivore's Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals |url=https://archive.org/details/omnivoresdilemma00poll_0 |url-access=registration |date=2006 |publisher=The Penguin Press |location=New York|isbn=9781594200823 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Legal definition=== | |||

| {{Main|Organic certification}} | {{Main|Organic certification}} | ||

| {{See also|List of countries with organic agriculture regulation}} | {{See also|List of countries with organic agriculture regulation}} | ||

| ] | |||

| Organic food production is distinct from ]. In the EU, ] and organic food are more commonly known as ecological or biological, or in short 'eco' and 'bio'.<ref name="eu_organic_labelling">Labeling, article 30 and Annex IV of </ref> | |||

| Currently, the European Union, the United States, Canada, Japan, and many other countries require producers to obtain ] based on government-defined standards to market food as organic within their borders.<ref name="EU Commission" /> In the context of these regulations, foods marketed as organic are produced in a way that complies with organic standards set by national governments and international organic industry trade organizations. | |||

| ] (run by the USDA)<ref name=USDANOP/> is in charge of the legal definition of ''organic'' in the United States and does ].]] | |||

| Organic food production is a heavily regulated industry, distinct from ]. Currently, the European Union, the United States, Canada, Japan and many other countries require producers to obtain ] in order to market food as organic within their borders. In the context of these regulations, organic food is food produced in a way that complies with organic standards set by national governments and international organizations. | |||

| In the United States, organic production |

In the United States, organic production is managed in accordance with the ] (OFPA) and regulations in Title 7, Part 205 of the Code of Federal Regulations to respond to site-specific conditions by integrating cultural, biological, and mechanical practices that foster cycling of resources, promote ecological balance, and conserve biodiversity.<ref>{{Cite web |date=24 July 2015 |title=Organic Farming |url=https://www.epa.gov/agriculture/organic-farming |access-date=7 December 2022 |website=United States Environmental Protection Agency |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Organic Regulations {{!}} Agricultural Marketing Service |url=https://www.ams.usda.gov/rules-regulations/organic |access-date=7 December 2022 |website=United States Agricultural Marketing Service}}</ref> If livestock are involved, the livestock must be reared with regular access to pasture and without the routine use of antibiotics or ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/getfile?dDocName=STELPRDC5082653&acct=noprulemaking |title=Access to Pasture Rule for Organic Livestock |publisher=Ams.usda.gov |access-date=9 September 2012 |archive-date=31 August 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140831212003/http://www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/getfile?dDocName=STELPRDC5082653&acct=noprulemaking |url-status=dead }}</ref> | ||

| Processed organic food usually contains only organic ingredients. If non-organic ingredients are present, at least a certain percentage of the food's total plant and animal ingredients must be organic (95% in the United States,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/getfile?dDocName=STELDEV3004323&acct=nopgeninfo |title=Labeling: Preamble |date= | |

Processed organic food usually contains only organic ingredients. If non-organic ingredients are present, at least a certain percentage of the food's total plant and animal ingredients must be organic (95% in the United States,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/getfile?dDocName=STELDEV3004323&acct=nopgeninfo |title=Labeling: Preamble |access-date=9 September 2012 |archive-date=14 May 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130514000319/http://www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/getfile?dDocName=STELDEV3004323&acct=nopgeninfo |url-status=dead }}</ref> Canada, and Australia). Foods claiming to be organic must be free of artificial ], and are often processed with fewer artificial methods, materials and conditions, such as ], ], solvents such as ], and ] ingredients.<ref name="irr">{{Unbulleted list citebundle|{{Cite book |editor=Allen, Gary J. |editor2=Albala, Ken |title=The Business of Food: Encyclopedia of the Food and Drink Industries |publisher=ABC-CLIO |year=2007 |isbn=978-0-313-33725-3 |page=288 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gNzmOUyiFRAC&pg=PA288}}|{{Cite web|url=https://www.cornucopia.org/hexane-guides/nvo_hexane_report.pdf |website=] |date=November 2010 |title=Toxic Chemicals: Banned In Organics But Common in "Natural" Food Production |first1=Charlotte |last1= Vallaeys}}}}</ref> Pesticides are allowed as long as they are not synthetic.<ref>Staff, National Pesticide Information Center. .</ref> However, under US federal organic standards, if pests and weeds are not controllable through management practices, nor via organic pesticides and herbicides, "a substance included on the National List of synthetic substances allowed for use in organic crop production may be applied to prevent, suppress, or control pests, weeds, or diseases".<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?c=ecfr&SID=622a69a51febf44818ad4c8d3535378f&rgn=div8&view=text&node=7:3.1.1.9.32.3.354.7&idno=7 |title=eCFR — Code of Federal Regulations |website=www.ecfr.gov}}</ref> Several groups have called for organic standards to prohibit ] on the basis of the ]<ref name="Paull">Paull, J. & Lyons, K. (2008) , Journal of Organic Systems, 3(1) 3–22.</ref> in light of unknown risks of nanotechnology.<ref>National Research Council. . National Academies Press: Washington DC. 2012.</ref>{{rp|5–6}} The use of nanotechnology-based products in the production of organic food is prohibited in some jurisdictions (Canada, the UK, and Australia) and is unregulated in others.<ref name=ONGR>Staff, The Organic & Non-GMO Report, May 2010. .</ref><ref>Canada General Standards Board. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160705064829/http://www.pacscertifiedorganic.ca/docs/manuals/CGSB-32.310%20Organic%20Crop%20Production%20Standards,%20Aug%202011%20revision.pdf |date=5 July 2016 }}.</ref>{{rp|2, section 1.4.1(l)}} | ||

| To be '''certified organic''', products must be grown and manufactured in a manner that adheres to standards set by the country they are sold in: | To be '''certified organic''', products must be grown and manufactured in a manner that adheres to standards set by the country they are sold in: | ||

| * Australia: NASAA Organic Standard<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nasaa.com.au/steps1.html |title=Steps to Certification – Within Australia |publisher=NASAA |date= | |

* Australia: NASAA Organic Standard<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nasaa.com.au/steps1.html |title=Steps to Certification – Within Australia |publisher=NASAA |access-date=9 September 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110216094450/http://www.nasaa.com.au/steps1.html |archive-date=16 February 2011 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | ||

| * Canada:<ref>{{cite web|url=http:// |

* Canada: Organic Products Regulations<ref>{{cite web |url=http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/SOR-2009-176/ |title=Organic Products Regulations |publisher=Canada Gazette, Government of Canada |date=21 December 2006 |access-date=2 October 2012}}</ref> | ||

| * European Union: ] | * European Union: ] | ||

| ** Sweden: KRAV<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.krav.se/ |

** Sweden: KRAV<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.krav.se/krav-standards |title=KRAV |publisher=Krav.se |access-date=2 October 2012}}</ref> | ||

| ** United Kingdom: DEFRA<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.defra.gov.uk/ |title=Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs |publisher=DEFRA |date= |

** United Kingdom: DEFRA<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.defra.gov.uk/ |title=Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs |publisher=DEFRA |access-date=2 October 2012}}</ref> | ||

| ** Poland: Association of Polish Ecology<ref>{{cite web |url=http://translate.googleusercontent.com/translate_c?depth=1&hl=pl&ie=UTF8&prev=_t&rurl=translate.google.pl&sl=pl&tl=en&u=http://sigmaart.nazwa.pl/polskaekologia/index.php%3Foption%3Dcom_content%26view%3Darticle%26id%3D2%26Itemid%3D2&usg=ALkJrhh-D_PVhb0X1163ngnmPe8aPQggxA |website=(Google translated into English) |title=About Us |publisher=Stowarzyszenie "Polska Ekologia" |access-date=14 August 2013}}</ref> | |||

| * Norway: Debio Organic certification<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.debio.no/ |title=Debio Organic certification |publisher=Debio.no |date= |accessdate=2012-10-02}}</ref> | |||

| * |

** Norway: Debio Organic certification<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.debio.no/ |title=Debio Organic certification |publisher=Debio.no |access-date=2 October 2012}}</ref> | ||

| * India: National Program for Organic Production (NPOP)<ref>{{cite web |url=http://apeda.gov.in/apedawebsite/organic/index.htm|title= Agricultural & Processed Food Products Export Development Authority – NATIONAL PROGRAMME FOR ORGANIC PRODUCTION}}</ref> | |||

| * Japan: JAS Standards<ref>{{dead link|date=August 2012}}</ref> | |||

| * Indonesia: BIOCert, run by Agricultural Ministry of Indonesia.<ref>{{cite web |url = http://www.biocert.or.id/index.php?lang=2 |title = BIOCert |access-date = 3 November 2013}}</ref> | |||

| * United States: ] Standards | |||

| * Japan: JAS Standards<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.maff.go.jp/e/jas/specific/organic.html |title=Organic Foods: MAFF |website=www.maff.go.jp |access-date=20 April 2014 |archive-date=26 April 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160426184913/http://www.maff.go.jp/e/jas/specific/organic.html |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| * Mexico: Consejo Nacional de Producción Orgánica, department of ]<ref>{{cite web |title=Ley de Productos Orgánicos |url=http://www.cnpo.org.mx/doc_interes.html |website=www.cnpo.org.mx |publisher=Consejo Nacional de Producción Orgánica |access-date=9 December 2016}}</ref> | |||

| * New Zealand: there are three bodies; BioGro, AsureQuality, and OFNZ | |||

| * United States: ] (NOP) Standards | |||

| In the United States, there are four different levels or categories for organic labeling:<ref>"USDA organic: what qualifies as organic?" Massage Therapy Journal Spring 2011: 36+. Academic OneFile.</ref> | |||

| The ] carries out routine inspections of farms that produce USDA Organic labeled foods.<ref>Nestle, Marion. 2006. NY: North Point Press. ISBN 978-0-86547-738-4</ref> On April 20, 2010, the Department of Agriculture said that it would begin enforcing rules requiring the spot testing of organically grown foods for traces of pesticides, after an auditor exposed major gaps in federal oversight of the organic food industry.<ref>{{cite web|last=Neuman|first=William|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/20/business/20organic.html?_r=1 |title=U.S. Plans Spot Tests of Organic Products |publisher=The New York Times |date=March 19, 2010 |accessdate=2012-09-09}}</ref> | |||

| # "100% Organic": This means that all ingredients are produced organically. It also may have the USDA seal. | |||

| # "Organic": At least 95% or more of the ingredients are organic. | |||

| # "Made With Organic Ingredients": Contains at least 70% organic ingredients. | |||

| # "Less Than 70% Organic Ingredients": Three of the organic ingredients must be listed under the ingredient section of the label. | |||

| In the U.S., the food label "natural" or "all natural" does not mean that the food was produced and processed organically.<ref>{{URL|http://www.nutrition.org/asn-blog/2013/02/interpreting-food-labels-natural-versus-organic/ |Interpreting Food Labels: Natural versus Organic}}.</ref><ref>{{URL|https://sustainability.tufts.edu/wp-content/uploads/Decoding-Food-Labels.pdf|Decoding Food Labels}}</ref>'' | |||

| == Environmental sustainability == | |||

| {{expand section|date=October 2018}} | |||

| {{Further|Environmental impact of pesticides}} | |||

| From an environmental perspective, ], ] and the use of ] in conventional farming has caused, and is causing, enormous damage worldwide to local ]s, ],<ref name="10.1016/bs.agron.2015.12.003"/><ref name="10.1007/s13165-019-00275-1"/><ref>{{cite journal |last1=M. Tahat |first1=Monther |last2=M. Alananbeh |first2=Kholoud |last3=A. Othman |first3=Yahia |last4=I. Leskovar |first4=Daniel |title=Soil Health and Sustainable Agriculture |journal=Sustainability |date=January 2020 |volume=12 |issue=12 |pages=4859 |doi=10.3390/su12124859 |language=en|doi-access=free }}</ref> biodiversity, ] and ] supplies, and sometimes farmers' health and ].<ref>{{cite journal|title=Water pollution by agriculture|journal=Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci|volume=363|issue=1491|date=12 February 2008|doi=10.1098/rstb.2007.2176|pmid=17666391|pmc=2610176|pages=659–66|author=Brian Moss}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.unep.or.jp/ietc/publications/short_series/lakereservoirs-3/6.asp|title=Social, Cultural, Institutional and Economic Aspects of Eutrophication|publisher=]|access-date=14 October 2018}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|title=Impact of pesticides use in agriculture: their benefits and hazards|journal=Interdiscip Toxicol.|volume=2|issue=1|date=March 2009|doi=10.2478/v10102-009-0001-7|pmid=21217838|pmc=2984095|pages=1–12|author=Aktar |display-authors=etal}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|url=https://www.nature.com/news/pesticides-spark-broad-biodiversity-loss-1.13214|title=Pesticides spark broad biodiversity loss|journal=Nature|date=17 June 2013|author=Sharon Oosthoek|doi=10.1038/nature.2013.13214|s2cid=130350392|access-date=14 October 2018|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name="Seufert">{{cite journal | last1=Seufert | first1=Verena | last2=Ramankutty | first2=Navin | title=Many shades of gray — The context-dependent performance of organic agriculture | journal=Science Advances | volume=3 | issue=3 | year=2017 | issn=2375-2548 | pmid=28345054 | pmc=5362009 | doi=10.1126/sciadv.1602638 | page=e1602638| bibcode=2017SciA....3E2638S }}</ref> | |||

| Organic farming typically reduces some environmental impact relative to conventional farming, but the scale of reduction can be difficult to quantify and varies depending on farming methods. In some cases, reducing food waste and dietary changes might provide greater benefits.<ref name=Seufert/> A 2020 study at the Technical University of Munich found that the greenhouse gas emissions of organically farmed plant-based food were lower than conventionally-farmed plant-based food. The greenhouse gas costs of organically produced meat were approximately the same as non-organically produced meat.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Organic meats found to have approximately the same greenhouse impact as regular meats|url=https://phys.org/news/2020-12-meats-approximately-greenhouse-impact-regular.html|access-date=31 December 2020|website=phys.org|language=en}}</ref><ref name=":0" /> However, the same paper noted that a shift from conventional to organic practices would likely be beneficial for long-term efficiency and ecosystem services, and probably improve soil over time.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last1=Pieper|first1=Maximilian|last2=Michalke|first2=Amelie|last3=Gaugler|first3=Tobias|date=15 December 2020|title=Calculation of external climate costs for food highlights inadequate pricing of animal products|url= |journal=Nature Communications|language=en|volume=11|issue=1|pages=6117|doi=10.1038/s41467-020-19474-6|pmid=33323933|pmc=7738510|bibcode=2020NatCo..11.6117P|issn=2041-1723}}</ref> | |||

| A 2019 life-cycle assessment study found that converting the total agricultural sector (both crop and livestock production) for ] and ] to organic farming methods would result in a net increase in ] emissions as increased overseas land use for production and import of crops would be needed to make up for lower organic yields domestically.<ref name="Smith 2019">{{cite journal |last1=Smith |first1=Laurence G. |last2=Kirk |first2=Guy J. D. |last3=Jones |first3=Philip J. |last4=Williams |first4=Adrian G. |title=The greenhouse gas impacts of converting food production in England and Wales to organic methods |journal=Nature Communications |date=22 October 2019 |volume=10 |issue=1 |pages=4641 |doi=10.1038/s41467-019-12622-7 |pmid=31641128 |pmc=6805889 |bibcode=2019NatCo..10.4641S }}</ref> | |||

| ==Health and safety== | |||

| There is little scientific evidence of benefit or harm to human health from a diet high in organic food, and conducting any sort of rigorous experiment on the subject is very difficult. A 2012 meta-analysis noted that "there have been no long-term studies of health outcomes of populations consuming predominantly organic versus conventionally produced food controlling for socioeconomic factors; such studies would be expensive to conduct."<ref name=Smith-Spangler2012/> A 2009 meta-analysis noted that "most of the included articles did not study direct human health outcomes. In ten of the included studies (83%), a primary outcome was the change in antioxidant activity. Antioxidant status and activity are useful biomarkers but do not directly equate to a health outcome. Of the remaining two articles, one recorded proxy-reported measures of atopic manifestations as its primary health outcome, whereas the other article examined the fatty acid composition of breast milk and implied possible health benefits for infants from the consumption of different amounts of conjugated linoleic acids from breast milk."<ref name=Dangour2009 /> In addition, as discussed above, difficulties in accurately and meaningfully measuring chemical differences between organic and conventional food make it difficult to extrapolate health recommendations based solely on chemical analysis. | |||

| According to a newer review, studies found adverse effects of certain pesticides on children's cognitive development at current levels of exposure.<ref name="10.1186/s12940-017-0315-4"/> Many pesticides show neurotoxicity in laboratory animal models and some are considered to cause endocrine disruption.<ref name="10.1186/s12940-017-0315-4"/> | |||

| As of 2012, the scientific consensus is that while "consumers may choose to buy organic fruit, vegetables and meat because they believe them to be more nutritious than other food.... the balance of current scientific evidence does not support this view."<ref>{{cite web|title=The Food Standards Agency's Current Stance|url=http://extras.timesonline.co.uk/organicfood2.pdf|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100331234955/http://extras.timesonline.co.uk/organicfood2.pdf|archive-date=31 March 2010}}</ref> The evidence of beneficial health effects of organic food consumption is scarce, which has led researchers to call for more long-term studies.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Hurtado-Barroso |first1=Sara |last2=Tresserra-Rimbau |first2=Anna |last3=Vallverdú-Queralt |first3=Anna |last4=Lamuela-Raventós |first4=Rosa María |date=30 November 2017 |title=Organic food and the impact on human health |journal=Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition |volume=59 |issue=4 |pages=704–714 |doi=10.1080/10408398.2017.1394815 |issn=1549-7852 |pmid=29190113|s2cid=39034672 }}</ref> In addition, studies that suggest that organic foods may be healthier than conventional foods face significant methodological challenges, such as the correlation between organic food consumption and factors known to promote a healthy lifestyle.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Brantsæter |first1=Anne Lise |last2=Ydersbond |first2=Trond A. |last3=Hoppin |first3=Jane A. |last4=Haugen |first4=Margaretha |last5=Meltzer |first5=Helle Margrete |date=20 March 2017 |title=Organic Food in the Diet: Exposure and Health Implications|journal=Annual Review of Public Health |volume=38 |pages=295–313 |doi=10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044437 |issn=1545-2093 |pmid=27992727|doi-access=free |hdl=11250/2457888 |hdl-access=free }}</ref><ref name="10.1186/s12940-017-0315-4" /> When the ] reviewed the literature on organic foods in 2012, they found that "current evidence does not support any meaningful nutritional benefits or deficits from eating organic compared with conventionally grown foods, and there are no well-powered human studies that directly demonstrate health benefits or disease protection as a result of consuming an organic diet."<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Forman |first1=Joel |last2=Silverstein |first2=Janet |last3=Committee on Nutrition |last4=Council on Environmental Health |last5=American Academy of Pediatrics |date=November 2012 |title=Organic foods: health and environmental advantages and disadvantages |journal=Pediatrics |volume=130 |issue=5 |pages=e1406–1415 |doi=10.1542/peds.2012-2579 |issn=1098-4275 |pmid=23090335|doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| Prevalent use of antibiotics in livestock used in non-organic meat is a key driver of ].<ref name="10.1186/s12940-017-0315-4">{{cite journal |last1=Mie |first1=Axel |last2=Andersen |first2=Helle Raun |last3=Gunnarsson |first3=Stefan |last4=Kahl |first4=Johannes |last5=Kesse-Guyot |first5=Emmanuelle |last6=Rembiałkowska |first6=Ewa |last7=Quaglio |first7=Gianluca |last8=Grandjean |first8=Philippe |title=Human health implications of organic food and organic agriculture: a comprehensive review |journal=Environmental Health |date=27 October 2017 |volume=16 |issue=1 |pages=111 |doi=10.1186/s12940-017-0315-4 |pmid=29073935 |pmc=5658984 |issn=1476-069X |doi-access=free |bibcode=2017EnvHe..16..111M }}</ref> | |||

| ===Consumer safety=== | |||

| ====Pesticide exposure==== | |||

| Claims of improved safety of organic food have largely focused on ]s.<ref name=MagkosSafety2006 /> These concerns are driven by the facts that "(1) acute, massive exposure to pesticides can cause significant adverse health effects; | |||

| (2) food products have occasionally been contaminated with pesticides, which can result in acute toxicity; and (3) most, if not all, commercially purchased food contains trace amounts of agricultural pesticides."<ref name=MagkosSafety2006 /> However, as is frequently noted in the scientific literature: "What does not follow from this, however, is that chronic exposure to the trace amounts of pesticides found in food results in demonstrable toxicity. This possibility is practically impossible to study and quantify;" therefore firm conclusions about the relative safety of organic foods have been hampered by the difficulty in proper ] and relatively small number of studies directly comparing organic food to conventional food.<ref name=Blair1/><ref name=Bourn /><ref name=MagkosSafety2006 /><ref name=Canavari2009/><ref>{{cite journal|last=Rosen|first=Joseph D.|title=A Review of the Nutrition Claims Made by Proponents of Organic Food|journal=Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety|date=May 2010|volume=9|issue=3|pages=270–277|doi=10.1111/j.1541-4337.2010.00108.x |pmid=33467813|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| Additionally, the Carcinogenic Potency Project,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://cpdb.thomas-slone.org/|title=The Carcinogenic Potency Project (CPDB)}}</ref> which is a part of the US ]'s Distributed Structure-Searchable Toxicity (DSSTox) Database Network,<ref>National Center for Computational Toxicology (NCCT) </ref> has been systemically testing the ]icity of chemicals, both natural and synthetic, and building a publicly available database of the results<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130218135909/http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/html/cpdbfs.htm |date=18 February 2013 }}</ref> for the past ~30 years. Their work attempts to fill in the gaps in our scientific knowledge of the carcinogenicity of all chemicals, both natural and synthetic, as the scientists conducting the Project described in the journal, '']'', in 1992: <blockquote>Toxicological examination of synthetic chemicals, without similar examination of chemicals that occur naturally, has resulted in an imbalance in both the data on and the perception of chemical ]s. Three points that we have discussed indicate that comparisons should be made with natural as well as synthetic chemicals.<br /> | |||

| 1) The vast proportion of chemicals that humans are exposed to occur naturally. Nevertheless, the public tends to view chemicals as only synthetic and to think of synthetic chemicals as toxic despite the fact that every natural chemical is also toxic at some dose. The daily average exposure of Americans to burnt material in the diet is ~2000 mg, and exposure to natural pesticides (the chemicals that plants produce to defend themselves) is ~1500 mg. In comparison, the total daily exposure to all synthetic pesticide residues combined is ~0.09 mg. Thus, we estimate that 99.99% of the pesticides humans ingest are natural. Despite this enormously greater exposure to natural chemicals, 79% (378 out of 479) of the chemicals tested for carcinogenicity in both rats and mice are synthetic (that is, do not occur naturally). <br /> | |||

| 2) It has often been wrongly assumed that humans have evolved defenses against the natural chemicals in our diet but not against the synthetic chemicals. However, defenses that animals have evolved are mostly general rather than specific for particular chemicals; moreover, defenses are generally inducible and therefore protect well from low doses of both synthetic and natural chemicals.<br /> | |||

| 3) Because the toxicology of natural and synthetic chemicals is similar, one expects (and finds) a similar positivity rate for carcinogenicity among synthetic and natural chemicals. The positivity rate among chemicals tested in rats and mice is ~50%. Therefore, because humans are exposed to so many more natural than synthetic chemicals (by weight and by number), humans are exposed to an enormous background of rodent carcinogens, as defined by high-dose tests on rodents. We have shown that even though only a tiny proportion of natural pesticides in plant foods have been tested, the 29 that are rodent carcinogens among the 57 tested, occur in more than 50 common plant foods. It is probable that almost every fruit and vegetable in the supermarket contains natural pesticides that are rodent carcinogens.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Gold L.S.| year = 1992 | title = Rodent carcinogens: Setting priorities | url = http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/cpdb/pdfs/Science1992.pdf | journal = Science | volume = 258 | issue = 5080| pages = 261–265 | doi=10.1126/science.1411524| pmid = 1411524 |display-authors=etal| bibcode = 1992Sci...258..261S }}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| While studies have shown via chemical analysis, as discussed above, that organically grown fruits and vegetables have significantly lower pesticide residue levels, the significance of this finding on actual health risk reduction is debatable as both conventional foods and organic foods generally have pesticide levels (]s) well below government established guidelines for what is considered safe.<ref name=Blair1/><ref name=Smith-Spangler2012/><ref name=MagkosSafety2006 /> This view has been echoed by the ]<ref name=USDA>{{cite web|last=Gold |first=Mary |title=Should I Purchase Organic Foods? |url=http://www.nal.usda.gov/afsic/pubs/faq/BuyOrganicFoodsC.shtml |publisher=USDA |access-date=5 March 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110721070355/http://www.nal.usda.gov/afsic/pubs/faq/BuyOrganicFoodsC.shtml |archive-date=21 July 2011 }}</ref> and the UK ].<ref name=FSA>{{cite web|title=Organic food|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110605025656/http://www.food.gov.uk/foodindustry/farmingfood/organicfood/|publisher=UK Food Standards Agency|archive-date=5 June 2011|url=http://www.food.gov.uk/foodindustry/farmingfood/organicfood/}}</ref> | |||

| A study published by the ] in 1993 determined that for infants and children, the major source of exposure to pesticides is through diet.<ref>National Research Council. . National Academies Press; 1993. {{ISBN|0-309-04875-3}}. Retrieved 10 April 2006.</ref> A study published in 2006 by Lu et al. measured the levels of organophosphorus pesticide exposure in 23 school children before and after replacing their diet with organic food. In this study, it was found that levels of organophosphorus pesticide exposure dropped from negligible levels to undetectable levels when the children switched to an organic diet, the authors presented this reduction as a significant reduction in risk.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Lu|first1=C|last2=Toepel|first2=K|last3=Irish|first3=R|last4=Fenske|first4=RA|last5=Barr|first5=DB|last6=Bravo|first6=R|title=Organic diets significantly lower children's dietary exposure to organophosphorus pesticides|pmid=16451864|volume=114|issue=2|pmc=1367841|date=February 2006|journal=Environ. Health Perspect.|pages=260–3|doi=10.1289/ehp.8418}}</ref> The conclusions presented in Lu et al. were criticized in the literature as a case of bad scientific communication.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Krieger RI|display-authors=etal| year = 2006 | title = OP Pesticides, Organic Diets, and Children's Health | journal = Environ Health Perspect | volume = 114 | issue = 10| pages = A572; author reply A572–3 | pmc=1626419 | pmid=17035114 | doi=10.1289/ehp.114-a572a}}</ref><ref>Alex Avery (2006) Environ Health Perspect.114(4) A210–A211.</ref> | |||

| More specifically, claims related to pesticide residue of increased risk of ] or lower ] have not been supported by the evidence in the medical literature.<ref name=MagkosSafety2006 /> Likewise, the ] (ACS) has stated their official position that "whether organic foods carry a lower risk of cancer because they are less likely to be contaminated by compounds that might cause cancer is largely unknown."<ref name=ACS>{{cite web|title=Food additives, safety, and organic foods|url=http://www.cancer.org/Healthy/EatHealthyGetActive/ACSGuidelinesonNutritionPhysicalActivityforCancerPrevention/acs-guidelines-on-nutrition-and-physical-activity-for-cancer-prevention-food-additives|publisher=American Cancer Society|access-date=11 July 2012|archive-date=19 April 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140419073421/http://www.cancer.org/healthy/eathealthygetactive/acsguidelinesonnutritionphysicalactivityforcancerprevention/acs-guidelines-on-nutrition-and-physical-activity-for-cancer-prevention-food-additives|url-status=dead}}</ref> Reviews have noted that the risks from ] sources or natural ]s are likely to be much more significant than short term or chronic risks from pesticide residues.<ref name=Blair1/>{{page needed|date=May 2015}}<ref name=MagkosSafety2006 /> | |||

| ====Microbiological contamination==== | |||

| ] has a preference for using ] as fertilizer, compared to conventional farming in general.{{citation needed|date=May 2019}} This practice seems to imply an increased risk of microbiological contamination, such as ], from organic food consumption, but reviews have found little evidence that the actual incidence of outbreaks can be positively linked to organic food production.<ref name=Blair1/>{{page needed|date=May 2015}}<ref name=Bourn /><ref name=MagkosSafety2006 /> The ], however, was blamed on organically farmed fenugreek sprouts.<ref>{{cite news|title=Analysis: E.coli outbreak poses questions for organic farming|url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ecoli-beansprouts-idUSTRE7552N720110606|access-date=22 June 2012|newspaper=Reuters|date=6 June 2011}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|title=Tracing seeds, in particular fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum) seeds, in relation to the Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) O104:H4 2011 Outbreaks in Germany and France|journal=EFSA Supporting Publications|volume=8|issue=7|doi=10.2903/sp.efsa.2011.EN-176|year=2011}}</ref> | |||

| ==Public perception== | ==Public perception== | ||

| There is a widespread public belief that organic food is safer, more nutritious, and better tasting than conventional food,<ref>{{cite book|last1=White|first1=Kim Kennedy|last2=Duram|first2=Leslie A|title=America Goes Green: An Encyclopedia of Eco-friendly Culture in the United States|date=2013|publisher=ABC-CLIO|location=California|isbn=978-1-59884-657-7|page=180}}</ref> which has largely contributed to the development of an ]. Consumers purchase organic foods for different reasons, including concerns about the effects of conventional farming practices on the environment, human health, and animal welfare.<ref name="auto">{{Cite web|title = Deciphering Organic Foods: A Comprehensive Guide to Organic Food Production, Consumption, and Promotion|url = https://www.novapublishers.com/catalog/product_info.php?products_id=60312|website = novapublishers.com|access-date = 29 October 2016|archive-date = 29 October 2016|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20161029180024/https://www.novapublishers.com/catalog/product_info.php?products_id=60312|url-status = dead}}{{page needed|date=October 2016}}</ref><ref name="Harvard" /> | |||

| There is widespread public belief that organic food is safer, more nutritious, and tastes better than conventional food; these beliefs have fueled increased demand for organic food despite higher prices.<ref name=MagkosSafety2006/><ref name=Smith-Spangler2012 /><ref name=Dangour2009 /><ref name=Canavari2009>Canavari, M., Asioli, D., Bendini, A., Cantore, N., Gallina Toschi, T., Spiller, A., Obermowe, T., Buchecker, K. and Lohmann, M. (2009). </ref> | |||

| While there may be some differences in the ] and ] contents of organically and conventionally produced food, the variable nature of ], shipping, storage, and handling makes it difficult to generalize results.<ref name="2014meta" /><ref name="Blair1">Blair, Robert. (2012). Organic Production and Food Quality: A Down to Earth Analysis. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, UK. Pages 72, 223, 225. {{ISBN|978-0-8138-1217-5}}</ref><ref name="Smith-Spangler2012">{{cite journal|last=Smith-Spangler|first=C |author2=Brandeau, ML|author2-link= Margaret Brandeau |author3=Hunter, GE |author4=Bavinger, JC |author5=Pearson, M |author6=Eschbach, PJ |author7=Sundaram, V |author8=Liu, H |author9=Schirmer, P |author10=Stave, C |author11=Olkin, I |author12=Bravata, DM|title=Are organic foods safer or healthier than conventional alternatives?: a systematic review|journal=Annals of Internal Medicine|date=4 September 2012|volume=157|issue=5|pages=348–366|pmid=22944875 |doi=10.7326/0003-4819-157-5-201209040-00007|s2cid=21463708 }}</ref><ref name="FSA" /><ref name="baranski2017">{{cite journal|last1=Barański|first1=M|last2=Rempelos|first2=L|last3=Iversen|first3=PO|last4=Leifert|first4=C|title=Effects of organic food consumption on human health; the jury is still out!|journal=Food & Nutrition Research|date=2017|volume=61|issue=1|pages=1287333|doi=10.1080/16546628.2017.1287333|pmid=28326003|pmc=5345585}}</ref> Claims that "organic food tastes better" are generally not supported by tests,<ref name="Blair1" />{{page needed|date=February 2021}}<ref name="Bourn" />{{page needed|date=February 2021}} but consumers often perceive organic food produce like fruits and vegetables to taste better.<ref name="Harvard" /> | |||

| Psychological effects such as the ] which are related to the choice and consumption of organic food and which may be akin to religious experiences in some people are in addition important motivating factors in the purchase of organic food.<ref name="Blair1" /> An example of the halo effect was demonstrated by Schuldt and Schwarz.<ref name="Schuldt">Schuldt, J.P. and Schwarz, N. (2010). . Judgment and Decision Making 5: 144–150.</ref> Their results showed that university students inferred that organic cookies were lower in calories and could be eaten more often than conventional cookies. This effect was observed even when the nutrition label conveyed an identical calorie content. The effect was more pronounced among participants who were strong supporters of organic production and had strong feelings about environmental issues. The perception that organic food is low-calorie food or health food appears to be common.<ref name=Blair1/><ref name=" Schuldt "> Schuldt, J.P. and Schwarz, N. (2010). The “organic” path to obesity? Organic claims influence calorie judgments and exercise recommendations. Judgment and Decision Making 5: 144–150.</ref> | |||

| The appeal of organic food varies with ] and attitudinal characteristics. Several high quality surveys find that income, educational level, physical activity, dietary habits and number of children are associated with the level of organic food consumption.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Kramer |first=Michael S. |title=Believe It or Not: The History, Culture, and Science Behind Health Beliefs |date=28 December 2023 |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-3-031-46022-7 |location=Cham |pages=151–162 |chapter=Organic Foods: A Healthier Alternative? |doi=10.1007/978-3-031-46022-7_16 |chapter-url=https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-46022-7_16}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Brantsæter |first1=Anne Lise |last2=Ydersbond |first2=Trond A. |last3=Hoppin |first3=Jane A. |last4=Haugen |first4=Margaretha |last5=Meltzer |first5=Helle Margrete |date=2017 |title=Organic Food in the Diet: Exposure and Health Implications. |url=https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044437 |journal=Annual Review of Public Health |volume=38 |issue=1 |pages=295–313|doi=10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044437 |pmid=27992727 |hdl=11250/2457888 |hdl-access=free }}</ref> USA research has found that women, young adults, liberals, and college graduates were significantly more likely to buy organic food regularly when compared to men, older age groups, people of different political affiliations, and less educated individuals. Income level and race/ethnicity did not appear to affect interest in organic foods in this same study. Furthermore, individuals who are only moderately-religious were more likely to purchase organic foods than individuals who were less religious or highly-religious. Additionally, the pursuit of organic foods was positively associated with valuing vegetarian/] food options, "natural" food options, and USA-made food options.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Onyango|first1=Benjamin|last2=Hallman|first2=William|last3=Bellows|first3=Anne|date=January 2006|title=Purchasing Organic Food in U.S. Food Systems: A Study of Attitudes and Practice|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/23506342|journal=British Food Journal|publisher=Emerald Group Publishing Limited|volume=109|issue=5|pages=407–409|doi=10.1108/00070700710746803|via=ResearchGate}}</ref> Organic food may also be more appealing to people who follow other restricted diets. One study found that individuals who adhered to vegan, vegetarian, or ] diet patterns incorporated substantially more organic foods in their diets when compared to ].<ref>{{Cite journal|date=1 July 2021|title=Estimated dietary exposure to pesticide residues based on organic and conventional data in omnivores, pesco-vegetarians, vegetarians and vegans|journal=Food and Chemical Toxicology|language=en|volume=153|pages=112179|doi=10.1016/j.fct.2021.112179|issn=0278-6915|last1=Baudry|first1=Julia|last2=Rebouillat|first2=Pauline|last3=Allès|first3=Benjamin|last4=Cravedi|first4=Jean-Pierre|last5=Touvier|first5=Mathilde|last6=Hercberg|first6=Serge|last7=Lairon|first7=Denis|last8=Vidal|first8=Rodolphe|last9=Kesse-Guyot|first9=Emmanuelle|pmid=33845070|s2cid=233223540|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| ===Taste=== | |||

| A 2009 literature review concluded that in the scientific literature examined, “there is broad agreement ...(that) most studies that have compared the taste and ] quality of organic and conventional foods report no consistent or significant differences between organic and conventional produce. Therefore, claiming that all organic food tastes different from all conventional food would not be correct. However, among the well-designed studies with respect to fruits and vegetables that have found differences, the vast majority favour organic produce.”<ref name=Bourn/><ref name=Canavari2009/> There is evidence that some organic fruit is drier than conventionally grown fruit; a slightly drier fruit may also have a more intense flavor due to the higher concentration of flavoring substances.<ref name=Blair1/> | |||

| The most important reason for purchasing organic foods seems to be beliefs about the products' health-giving properties and higher nutritional value.<ref name="auto"/><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Yiridoe|first1=Emmanuel|last2=Bonti-Ankomah|first2=Samuel|last3=C. Martin|first3=Ralph|date=1 December 2005|title=Comparison of Consumer Perceptions and Preference Toward Organic Versus Conventionally Produced Foods: A Review and Update of the Literature|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/231897495|journal=Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems|volume=20|issue=4|pages=193–205|doi=10.1079/RAF2005113|s2cid=155004745|quote=Some studies reported health and food safety as the number one quality attribute considered by organic produce buyers}}</ref><ref name="Harvard" /> These beliefs are promoted by the organic food industry,<ref>Joanna Schroeder for Academics Review. </ref> and have fueled increased demand for organic food despite higher prices and difficulty in confirming these claimed benefits scientifically.<ref name="2014meta" /><ref name="Smith-Spangler2012" /><ref name=MagkosSafety2006>{{Cite journal | doi=10.1080/10408690490911846| pmid=16403682|title = Organic Food: Buying More Safety or Just Peace of Mind? A Critical Review of the Literature| journal=Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition| volume=46| issue=1| pages=23–56|year = 2006|last1 = Magkos|first1 = Faidon| last2=Arvaniti| first2=Fotini| last3=Zampelas| first3=Antonis| s2cid=18939644}}</ref><ref name="Dangour2009">Dangour AD et al. (2009) The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 92(1) 203–210</ref><ref name="Canavari2009">Canavari, M., Asioli, D., Bendini, A., Cantore, N., Gallina Toschi, T., Spiller, A., Obermowe, T., Buchecker, K. and Lohmann, M. (2009). </ref> Organic labels also stimulate the consumer to view the product as having more positive nutritional value.<ref>{{Cite web|title = Organic labels- A consumers satisfaction for health | |||

| A 2000 ] report noted an unpublished study in which ] apples "were found to be firmer and received higher taste scores than conventionally grown apples".<ref name=FAO>, Twenty Second FAO Regional Conference for Europe, 24–28 Jul-2000.</ref> | |||

| |url = http://www.watershedpedia.com/organic-labels-a-consumers-satisfaction-for-health/|website = watershedpedia.com|access-date = 11 November 2017}}</ref> | |||

| Psychological effects such as the ] are also important motivating factors in the purchase of organic food.<ref name="Blair1" /> | |||

| Some foods, such as bananas, are picked when unripe, then artificially induced to ripen using a chemical (such as ] or ]) while in transit, possibly producing a different taste.<ref>, by Joanna Blythman (The Observer, 13-Mar-2005) and , Honduran Agricultural Research Foundation (FHIA).</ref> The issue of ethylene use in organic food production is contentious; opponents claiming that its use only benefits large companies, and opens the door to weaker organic standards.<ref>, by Julie Deardorff (''Chicago Tribune'', 9-Dec-2005) and , by Joan Murphy (''The Produce News'', 22-Nov-2005).</ref> | |||

| In China the increasing demand for organic products of all kinds, and in particular milk, baby food and infant formula, has been "spurred by a series of food scares, the worst being the death of six children who had consumed baby formula laced with ]" in 2009 and the ], making the Chinese market for organic milk the largest in the world as of 2014.<ref name=Chen>{{cite news|last=Chen|first=Jue|title=Food safety in China opens doors for Australia's agri sector|url=http://www.chinaconnections.com.au/en/magazine/current-issue/1940-food-safety-in-china-opens-doors-for-australia%E2%80%99s-agri-sector|access-date=27 March 2014|newspaper=Australia China Connections|date=February 2014|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140327224148/http://www.chinaconnections.com.au/en/magazine/current-issue/1940-food-safety-in-china-opens-doors-for-australia%E2%80%99s-agri-sector|archive-date=27 March 2014}}</ref><ref name=stewart>{{cite web|last=Stewart|first=Emily|title=Chinese babies looking for more Aussie organic milk|url=http://www.abc.net.au/news/2013-12-04/chinese-babies-looking-for-more-aussie-organic-milk/5135522|website=abc.net.au|publisher=Australian Broadcasting Corporation|access-date=27 March 2014|date=4 December 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Organic exports to China on the rise|url=http://www.dynamicexport.com.au/export-market/articles-export-markets/Organic-exports-to-China-on-the-rise/|website=Dynamic Export|access-date=27 March 2014}}</ref> A Pew Research Center survey in 2012 indicated that 41% of Chinese consumers thought of food safety as a very big problem, up by three times from 12% in 2008.<ref name=Wikes>{{cite web|last=Wikes|first=Richard|title=What Chinese are worried about|url=http://www.pewglobal.org/|website=Pew Research Global Attitudes Project|publisher=Pew Research|access-date=27 March 2014}}</ref> | |||

| ==Differences in chemical composition of organically and conventionally grown food== | |||

| With respect to chemical differences in the composition of organically grown food compared with conventionally grown food, studies have examined differences in ], ], and ] residues. These studies generally suffer from ] variables, and are difficult to generalize due to differences in the tests that were done, and in the methods of testing, and also because the vagaries of agriculture affect the chemical composition of food; these variables include variations in weather (season to season as well as place to place); crop treatments (fertilizer, pesticide, etc.); soil composition; the cultivar used, and in the case of meat and dairy products, the parallel variables in animal production.<ref name=Smith-Spangler2012/> Treatment of the foodstuffs after initial gathering (whether milk is pasteurized or raw), the length of time between harvest and analysis, as well as conditions of transport and storage, also affect the chemical composition of a given item of food.<ref name=Smith-Spangler2012/> Additionally, there is evidence that organic produce is drier than conventionally grown produce; a higher content in any chemical category may be explained higher concentration rather than in absolute amounts.<ref name=Blair1/> | |||

| A 2020 study on marketing processed organic foods shows that, after much growth in the fresh organic foods sector, consumers have started to buy processed organic foods, which they sometime perceive to be just as healthy or even healthier than the non-organic version – depending on the marketing message.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Anghelcev |first1=George |last2=McGroarty |first2=Siobhan |last3=Sar |first3=Sela |last4=Moultrie |first4=Jas |last5=Huang |first5=Yan |title=Marketing Processed Organic Foods: The Impact of Promotional Message Framing (Vice Vs. Virtue Advertising) on Perceptions of Healthfulness |journal=Journal of Food Products Marketing |date=2020 |volume=26 |issue=6 |pages=401–424 |doi=10.1080/10454446.2020.1792022 |s2cid=221055629 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| ===Nutrients=== | |||

| A 2012 survey of the scientific literature did not find significant differences in the vitamin content of organic and conventional plant or animal products, and found that results varied from study to study.<ref name=Smith-Spangler2012/> Produce studies reported on ] (]) (31 studies), ] (a precursor for ]) (12 studies), and ] (a form of ]) (5 studies) content; milk studies reported on beta-carotene (4 studies) and alpha-tocopherol levels (4 studies). Few studies examined vitamin content in meats, but these found no difference in beta-carotene in beef, alpha-tocopherol in pork or beef, or vitamin A (retinol) in beef. The authors analyzed 11 other nutrients reported in studies of produce. Only 2 nutrients were significantly higher in organic than conventional produce: ] (median difference, 0.15 mg/kg ) and total ] (median difference, 31.6 mg/kg ). The result for phosphorus was statistically homogenous, but removal of 1 study reduced the summary effect size and rendered the effect size statistically insignificant. The finding for total phenols was heterogeneous statistically and became statistically insignificant when two studies not reporting sample size were removed. Too few studies of animal products reported on other nutrients for effect sizes to be calculated. The few studies of milk that the authors found were all (but for one) of ], and suggest that raw organic milk may contain significantly more beneficial ] (median difference, 0.5 g/100 g ) and ] than raw conventional milk (median difference, 0.26 g/100 g ). | |||

| ===Taste=== | |||

| Similarly, organic chicken contained higher levels of omega-3 fatty acids than conventional chicken (median difference, 1.99 g/100 g ). The authors found no difference in the protein or fat content of organic and conventional raw milk. Minor differences in ascorbic acid, protein concentration and several ] have been identified between organic and conventional foods.<ref name=Magkos2003>Magkos F et al (2003 International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition 54(5):357–71</ref><ref>J.N. Pretty JN Et al (2005) Food Policy 30: 1–19</ref> | |||

| There is no good evidence that organic food tastes better than its non-organic counterparts.<ref name=Bourn>{{cite journal |vauthors=Bourn D, Prescott J |title=A comparison of the nutritional value, sensory qualities, and food safety of organically and conventionally produced foods |journal=Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr |volume=42 |issue=1 |pages=1–34 |date=January 2002 |doi= 10.1080/10408690290825439|pmid=11833635|s2cid=13605409 }}</ref> There is evidence that some organic fruit is drier than conventionally grown fruit; a slightly drier fruit may also have a more intense flavor due to the higher concentration of flavoring substances.<ref name=Blair1/>{{page needed|date=May 2015}} | |||

| Some foods which are picked when unripe, such as bananas, are cooled to prevent ripening while they are shipped to market, and then are induced to ripen quickly by exposing them to ] or ], chemicals produced by plants to induce their own ripening; as flavor and texture changes during ripening, this process may affect those qualities of the treated fruit.<ref>Washington State University Extension Office. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181212052207/http://www.postharvest.tfrec.wsu.edu/pages/PC2000F |date=12 December 2018 }}</ref><ref>Fresh Air, National Public Radio. 30 August 2011 </ref> | |||

| A 2003 study found that the total phenolic content was significantly higher in organically grown marionberries, strawberries, and corn compared to their conventionally grown counterparts.<ref>Asami, Danny K. . ''Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry'' (American Chemical Society), 51 (5), 1237 -1241, 2003. 10.1021/jf020635c S0021-8561(02)00635-0. Retrieved 10-Apr-2006.</ref> | |||

| ==Chemical composition== | |||

| ===Anti-nutrients=== | |||

| ] | |||

| The amount of ] content in certain vegetables, especially green ] and ]s, has been found to be lower when grown organically as compared to conventionally.<ref name=MagkosSafety2006 /> When evaluating environmental toxins such as ], the USDA has noted that organically raised ] may have lower ] levels,<ref name=USDA /> while literature reviews found no significant evidence that levels of arsenic, ] or other heavy metals differed significantly between organic and conventional food products.<ref name=MagkosSafety2006 /><ref name=Blair1/> | |||

| With respect to chemical differences in the composition of organically grown food compared with conventionally grown food, studies have examined differences in ], ], and ] residues.<ref name=baranski2017/> These studies generally suffer from ] variables, and are difficult to generalize due to differences in the tests that were done, the methods of testing, and because the vagaries of agriculture affect the chemical composition of food;<ref name=baranski2017/> these variables include variations in weather (season to season as well as place to place); crop treatments (fertilizer, pesticide, etc.); soil composition; the cultivar used, and in the case of meat and dairy products, the parallel variables in animal production.<ref name=2014meta/><ref name=Smith-Spangler2012/> Treatment of the foodstuffs after initial gathering (whether milk is pasteurized or raw), the length of time between harvest and analysis, as well as conditions of transport and storage, also affect the chemical composition of a given item of food.<ref name=2014meta/><ref name=Smith-Spangler2012/> Additionally, there is evidence that organic produce is drier than conventionally grown produce; a higher content in any chemical category may be explained by higher concentration rather than in absolute amounts.<ref name=Blair1/>{{page needed|date=May 2015}} | |||

| === |

===Nutrients=== | ||

| Many people believe that organic foods have higher content of nutrients and thus are healthier than conventionally produced foods.<ref name="reuters">{{cite web|title=Organic Food No More Nutritious than Non-organic: Study|publisher=Reuters Health|author=Genevra Pittman|url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-organic-idUSBRE88303620120904|date=4 September 2012}}</ref> However, scientists have not been equally convinced that this is the case as the research conducted in the field has not shown consistent results.<ref name="Harvard"/> | |||

| The 2012 meta-analysis determined that detectable pesticide residues were found in 7% of organic produce samples and 38% of conventional produce samples. Organic produce had 30% lower risk for contamination with any detectable pesticide residue than conventional produce. This result was statistically heterogeneous, potentially because of the variable level of detection used among these studies. Only three studies reported the prevalence of contamination exceeding maximum allowed limits; all were from the European Union.<ref name=Smith-Spangler2012/> | |||

| A 2009 systematic review found that organically produced foodstuffs are not richer in vitamins and minerals than conventionally produced foodstuffs.<ref name="Smith-Spangler2012" /> This systematic review found a lower nitrogen and higher phosphorus content in organic produced compared to conventionally grown foodstuffs. Content of vitamin C, calcium, potassium, total soluble solids, copper, iron, nitrates, manganese, and sodium did not differ between the two categories.<ref name=reuters/> | |||

| ===Bacterial contamination=== | |||

| The 2012 meta-analysis determined that prevalence of E. coli contamination was not ] (7% in organic produce and 6% in conventional produce). Four of the five studies found higher risk for contamination among organic produce. When the authors removed the 1 study (of lettuce) that found higher contamination among conventional produce, organic produce had a 5% greater risk for contamination than conventional alternatives. While bacterial contamination is common among both organic and conventional animal products, differences in the prevalence of bacterial contamination between organic and conventional animal products were statistically insignificant.<ref name=Smith-Spangler2012/> | |||

| A 2012 survey of the scientific literature did not find significant differences in the vitamin content of organic and conventional plant or animal products, and found that results varied from study to study.<ref name=Smith-Spangler2012/> Produce studies reported on ] (]) (31 studies), ] (a precursor for ]) (12 studies), and ] (a form of ]) (5 studies) content; milk studies reported on beta-carotene (4 studies) and alpha-tocopherol levels (4 studies). Few studies examined vitamin content in meats, but these found no difference in beta-carotene in beef, alpha-tocopherol in pork or beef, or vitamin A (retinol) in beef. The authors analyzed 11 other nutrients reported in studies of produce. A 2011 literature review found that organic foods had a higher micronutrient content overall than conventionally produced foods.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Hunter|first1=Duncan|last2=Foster|first2=Meika|last3=McArthur|first3=Jennifer O.|last4=Ojha|first4=Rachel|last5=Petocz|first5=Peter|last6=Samman|first6=Samir|title=Evaluation of the Micronutrient Composition of Plant Foods Produced by Organic and Conventional Agricultural Methods|journal=Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition|date=July 2011|volume=51|issue=6|pages=571–582|doi=10.1080/10408391003721701|pmid=21929333|s2cid=10165731}}</ref> | |||

| ==Health and safety== | |||

| Similarly, organic chicken contained higher levels of ]s<ref name="cnn">{{cite web|url=https://edition.cnn.com/2016/02/18/health/organic-meat-milk-fatty-acids-omega-3s/index.html|title=Organic meats, milk contain more omega-3s, study finds|website=CNN|date=18 February 2016 |access-date=19 December 2020}}</ref> than conventional chicken. The authors found no difference in the protein or fat content of organic and conventional raw milk.<ref name=Magkos2003>{{cite journal|pmid=12907407|year=2003|last1=Magkos|first1=F|title=Organic food: Nutritious food or food for thought? A review of the evidence|journal=International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition|volume=54|issue=5|pages=357–71|last2=Arvaniti|first2=F|last3=Zampelas|first3=A|doi=10.1080/09637480120092071|s2cid=19352928}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|title=Farm costs and food miles: An assessment of the full cost of the UK weekly food basket|last1=Pretty|first1=J.N.|last2=Ball|first2=A.S.|last3=Lang|first3=T.|last4=Morison|first4=J.I.L.|volume=30|issue=1|pages=1–19|journal=Food Policy|year=2005|doi=10.1016/j.foodpol.2005.02.001}}</ref> | |||

| ===Health effects of organic food diet=== | |||

| With respect to scientific knowledge of health benefits from a diet of organic food, several factors limit our ability to say that there is any health benefit, or detriment, from such a diet. The 2012 meta-analysis noted that "there have been no long-term studies of health outcomes of populations consuming predominantly organic versus conventionally produced food controlling for socioeconomic factors; such studies would be expensive to conduct."<ref name=Smith-Spangler2012/> The 2009 meta-analysis noted that "Most of the included articles did not study direct human health outcomes. In ten of the included studies (83%), a primary outcome was the change in antioxidant activity. Antioxidant status and activity are useful biomarkers but do not directly equate to a health outcome. Of the remaining two articles, one recorded proxy-reported measures of atopic manifestations as its primary health outcome, whereas the other article examined the fatty acid composition of breast milk and implied possible health benefits for infants from the consumption of different amounts of conjugated linoleic acids from breast milk."<ref name=Dangour2009 /> In addition, as discussed above, difficulties in accurately and meaningfully measuring chemical differences between organic and conventional food make it difficult to extrapolate health recommendations based solely on chemical analysis. | |||