| Revision as of 02:07, 29 September 2005 view source69.195.160.205 (talk) →Early Life← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 15:51, 13 December 2024 view source Jlaramee (talk | contribs)367 editsm →Aedileship and election as pontifex maximus: "however" is needed to indicate contradiction | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Roman general and dictator (100–44 BC)}} | |||

| {{otheruses}} | |||

| {{Redirect2|Gaius Julius Caesar|Caesar|the name|Gaius Julius Caesar (name)|text=For other uses, see ], ], and ]}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{For|the German politician|Cajus Julius Caesar}} | |||

| <!--this article has always consistently used BC notation. Please keep it that way - it is the only worldwide standard notation understood by the general public. Please do not disrupt Misplaced Pages by changing it--> | |||

| {{pp|small=yes}} | |||

| '''Gaius Julius Caesar''' (]: <small>IMP·C·IVLIVS·CAESAR·DIVVS</small>]) (b. ], ca. ]; d. ], ]) was a ] military and political leader. He was instrumental in the transformation of the ] into the ]. His conquest of ] extended the Roman world all the way to the ], introducing Roman influence into what has become modern ], an accomplishment of which direct consequences are visible to this day. In ] Caesar launched the first Roman invasion of ]. | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=September 2024}}{{Use British English|date=November 2024}} | |||

| Caesar fought and won a ] which left him undisputed master of the Roman world, and began extensive reforms of Roman society and government. He was proclaimed ] for life, and heavily centralized the already faltering government of the weak Republic. Caesar's friend ] conspired with others to assassinate Caesar in hopes of saving the Republic. The dramatic ] on the ] was the catalyst for a second set of civil wars, which marked the end of the ] and the beginning of the ] under Caesar's grand-nephew and adopted son ], later known as ]. | |||

| {{Infobox person | |||

| Caesar's military campaigns are known in detail from his own written ], and many details of his life are recorded by later historians such as ], ], and ]. | |||

| | name = Julius Caesar | |||

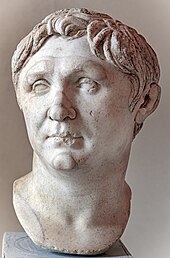

| | image = Retrato de Julio César (26724093101) (cropped).jpg | |||

| | image_upright = 1.1 | |||

| | alt = The Tusculum portrait, a marble sculpture of Julius Caesar | |||

| | caption = Caesar as portrayed by the ] | |||

| | birth_date = 12 July 100 BC<ref>{{harvnb|Badian|2009|p=|ps=. All ancient sources place his birth in 100 BC. Some historians have argued against this; the "consensus of opinion" places it in 100 BC. {{harvnb|Goldsworthy|2006|p=30}}.}}</ref> | |||

| | birth_place = ], Rome | |||

| | death_date = ] 44 BC (aged 55)<!-- 100 - 44 is, after adjusting for that 15 March is before July, 55 --> | |||

| | death_place = ], Rome | |||

| | death_cause = ] (]) | |||

| | resting_place = | |||

| | resting_place_coordinates = | |||

| | occupation = {{hlist|Politician|soldier|author}} | |||

| | years_active = | |||

| | office = {{Aligned table | |||

| | class=nowrap |fullwidth=on |leftright=on | |||

| | style=line-height:1.2em; |col2style=font-size:90%; | |||

| | ] | 64–44 BC | |||

| | ] | 59 BC | |||

| | ] (Gaul, Illyricum) | 58–49 BC | |||

| | ] | 49–44 BC | |||

| | Consul | 48, 46–44 BC | |||

| | ] | 44 BC<ref>All offices and years thereof from {{harvnb|Broughton|1952|p=574}}.</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| | organization = | |||

| | known_for = | |||

| | notable_works = {{ubl|{{lang|la|]}}|{{lang|la|]}}}} | |||

| | net_worth = <!-- Net worth should be supported with a citation from a reliable source --> | |||

| | opponents = | |||

| | spouse = {{Aligned table | |||

| | class=nowrap |fullwidth=on |leftright=on | |||

| | style=line-height:1.2em; |col2style=font-size:90%; | |||

| | ] (disputed) | | |||

| | ] | {{Abbr|m.|married}} 84 BC; {{Abbr|d.|died}} 69 BC | |||

| | ] | {{Abbr|m.|married}} 67 BC; {{Abbr|div.|divorced}} 61 BC | |||

| | ] | {{Abbr|m.|married}} 59 BC | |||

| }} | |||

| | partner = ] | |||

| | children = {{ubl|]|] (unacknowledged)|] (adoptive)}} | |||

| | parents = {{ubl|]|]}} | |||

| | relatives = | |||

| | awards = ] | |||

| | module = {{Infobox officeholder | embed = yes | |||

| | allegiance = ] | |||

| | branch = ] | |||

| | commands = ] | |||

| | battles = {{tree list}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{tree list/end}} | |||

| | serviceyears = 81–45 BC | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Gaius Julius Caesar'''{{efn|Pronounced {{IPAc-en|ˈ|s|iː|z|ər}} {{respell|SEE|zər}}, {{IPA|la-x-classic|ˈɡaːi.ʊs ˈjuːliʊs ˈkae̯sar|lang|small=no}}.}} (12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a ] general and statesman. A member of the ], Caesar led the Roman armies in the ] before defeating his political rival ] in ], and subsequently became ] from 49 BC until ] in 44 BC. He played a critical role in ] the ] and the rise of the ]. | |||

| ==Early Life== | |||

| In 60 BC, Caesar, ], and ] formed the ], an informal political alliance that dominated ] for several years. Their attempts to amass political power were opposed by many in the ], among them ] with the private support of ]. Caesar rose to become one of the most powerful politicians in the Roman Republic through a string of military victories in the ], completed by 51 BC, which greatly extended Roman territory. During this time he both ] and ]. These achievements and the support of his veteran army threatened to eclipse the standing of Pompey, who had realigned himself with the Senate after the ] in 53 BC. With the ] concluded, the Senate ordered Caesar to step down from his military command and return to Rome. In 49 BC, Caesar openly defied the Senate's authority by ] and marching towards Rome at the head of an army.<ref>{{cite book |last=Keppie |first=Lawrence |chapter=The approach of civil war |title=The Making of the Roman Army: From Republic to Empire |publisher=] |location=Norman, OK |date=1998 |page=102 |isbn=978-0-8061-3014-9}}</ref> This began ], which he won, leaving him in a position of near-unchallenged power and influence in 45 BC. | |||

| Caesar was born in Rome to a well-known ] family ('']'' ]), which supposedly traced its ancestry to ], the son of the ] prince ], who according to myth was the son of ]. According to legend, Caesar was born by ] and is its namesake, though this is unlikely because it was only performed on dead women, and his mother lived long after he was born. Caesar was raised in a modest apartment building (''insula'') in the Subura, a lower-class neighborhood of Rome. <!--did they mean Suburba? --> | |||

| After assuming control of government, Caesar began a programme of social and governmental reform, including the creation of the ]. He gave ] to many residents of far regions of the Roman Republic. He initiated land reforms to support his veterans and initiated an enormous building programme. In early 44 BC, he was proclaimed "dictator for life" ({{lang|la|]}}). Fearful of his power and domination of the state, a group of senators led by ] and ] assassinated Caesar on the ] (15 March) 44 BC. A new ] broke out and the ] was never fully restored. Caesar's great-nephew and adopted heir Octavian, later known as ], rose to sole power after defeating his opponents in the ]. Octavian set about solidifying his power, and the era of the ] began. | |||

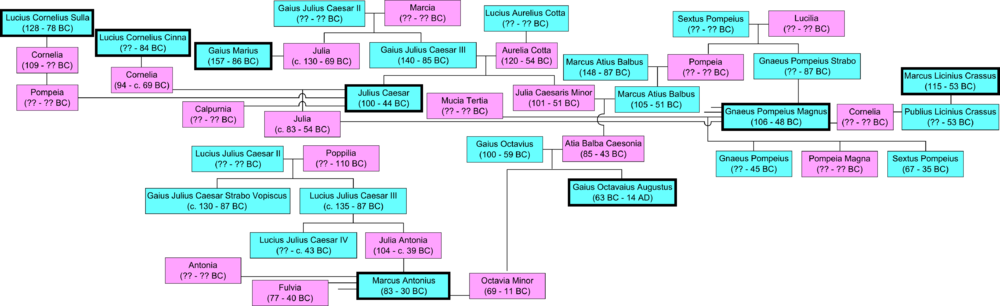

| The Julii Caesares, although of impeccable ] ] stock, were not rich by the standards of the Roman nobility. Thus, no member of his family had achieved any outstanding prominence in recent times, though in his father's generation there was a renaissance of their fortunes. His paternal aunt, ], married ], a talented general and reformer of the Roman army. Marius became one of the richest men in Rome at the time and while he gained political influence, the Caesar family gained the wealth. | |||

| Caesar was an accomplished author and historian as well as a statesman; much of his life is known from his own accounts of his military campaigns. Other contemporary sources include the letters and speeches of Cicero and the historical writings of ]. Later biographies of Caesar by ] and ] are also important sources. Caesar is considered by many historians to be one of the greatest military commanders in history.<ref>{{cite book |last=Tucker |first=Spencer |title=Battles That Changed History: An Encyclopedia of World Conflict|url=https://archive.org/details/battlesthatchang00tuck_956 |url-access=limited |publisher=ABC-CLIO |year=2010 |page= |isbn=978-1-59884-430-6}}</ref> His ] was subsequently adopted as a ] for "]"; the title "]" was used throughout the Roman Empire, giving rise to modern descendants such as ] and ]. He has ]. | |||

| Towards the end of Marius' life in ], internal politics reached a breaking point. Several disputes of the Marius faction against ] led to civil war and eventually opened the way to Sulla's dictatorship. Caesar was tied to the Marius party through family connections. Not only was he Marius' nephew, he was also married to ], the youngest daughter of ], Marius' greatest supporter and Sulla's enemy. To make matters worse, in the year ], just after Caesar turned 15, his father grew ill and soon died. Both Marius and his father had left Caesar much of their property and wealth in their wills. | |||

| ==Early life and career== | |||

| Thus, when Sulla emerged as the winner of this civil war and began his program of ]s, Caesar, not yet 20 years old, was in a bad position. Sulla ordered Caesar to ] Cornelia in ], but Caesar refused and prudently left Rome to hide. Sulla pardoned Caesar and his family and allowed him to return to Rome. In a prophetic moment, Sulla was said to comment on the dangers of letting Caesar live. According to Suetonius, the dictator in relenting on Caesar's proscription said, "He whose life you so much desire will one day be the overthrow of the part of nobles, whose cause you have sustained with me; for in this one Caesar, you will find many a Marius." | |||

| {{main|Early life and career of Julius Caesar}} | |||

| ], Caesar's uncle and the husband of Caesar's aunt ]. He was an enemy of Sulla and took the city with Lucius Cornelius Cinna in 87 BC.]] | |||

| Gaius Julius Caesar was born into a ] family, the {{lang|la|] ]}} on 12 July 100 BC.<ref>{{harvnb|Badian|2009|p=16|ps=, pursuant to Macr. ''Sat.'' 1.12.34, quoting a law by Mark Antony noting the date as the fourth day before the Ides of Quintilis. Only Dio gives 13 July. All sources give the year 100 BC.}}</ref> The family claimed to have immigrated to Rome from ] during the seventh century BC after the third ], ], took and destroyed their city. The family also claimed descent from Julus, the son of Aeneas and founder of Alba Longa. Given that Aeneas was a son of Venus, this made the clan divine. This genealogy had not yet taken its final form by the first century, but the clan's claimed descent from Venus was well established in public consciousness.{{sfn|Goldsworthy|2006|pp=32–33}} There is no evidence that Caesar himself was born by ]; such operations entailed the death of the mother, but ] lived for decades after his birth and no ancient sources record any difficulty with the birth.{{sfn|Goldsworthy|2006|p=35}} | |||

| Despite Sulla's pardon, Caesar did not remain in Rome and left for military service in ] and ]. While still in ], Caesar was involved in several military operations. In ], while still serving under ], he played a pivotal role in the siege of ]. During the course of the battle Caesar showed such personal bravery in saving the lives of ], that he was later awarded the ] (oak crown). The award was of the highest honor given to a non-commander, and when worn in public, even in the presence of the ], all were forced to stand and applaud his presence. | |||

| Despite their ancient pedigree, the Julii Caesares were not especially politically influential during the middle republic. The first person known to have had the ] ''Caesar'' was a praetor in 208 BC during the ]. The family's first consul was in 157 BC, though their political fortunes had recovered in the early first century, producing two consuls in 91 and 90 BC.<ref>{{harvnb|Badian|2009|p=14}}; {{harvnb|Goldsworthy|2006|pp=31–32|ps=. The consul of 157 BC was ]; the consuls of 91 and 90 were ] and ], respectively.}}</ref> Caesar's homonymous father was moderately successful politically. He married ], a member of the politically influential ], producing – along with Caesar – two daughters. Buoyed by his own marriage and ] marriage (the dictator's aunt) with the extremely influential ], he also served on the ] land commission in 103 BC and was elected praetor some time between 92 and 85 BC; he served as proconsular governor of Asia for two years, likely 91–90 BC.<ref>{{harvnb|Badian|2009|p=15}} dates the land commission to 103 per ''MRR'' 3.109; {{harvnb|Goldsworthy|2006|pp=33–34}}; {{harvnb|Broughton|1952|p=22}}, dating the proconsulship to 91 with praetorship in 92 BC and citing, among others, {{CIL|1|705}} and {{CIL|1|706}}.</ref> | |||

| Back in Rome in ], when Sulla died, Caesar began his political career in the ] at Rome as an ], known for his ] and ruthless prosecution of former governors notorious for extortion and corruption. The great orator ] even commented, "Does anyone have the ability to speak better than Caesar?" Aiming at ]al perfection, Caesar traveled to ] in ] for philosophical and oratorical studies with the famous teacher ]. | |||

| === Life under Sulla and military service === | |||

| On the way, Caesar was kidnapped by ] ] in the ]. When they demanded a ransom of twenty ], he laughed at them, saying they did not know whom they had captured. Instead, he ordered them to ask for fifty. They accepted, and Caesar sent his followers to various cities to collect the ransom money. In all he was held for thirty-eight days and would often laughingly threaten to have them all crucified. True to his word, as soon as he was ransomed and released, he organized a naval force, captured the pirates and their island stronghold and put them to death by ] as a warning to other pirates. However, since they had treated him well, he had their legs broken before they were crucified to lessen their suffering. | |||

| ] in 54 BC. Sulla took the city in 82 BC, purged his political enemies, and instituted ].]] | |||

| Caesar's father did not seek a consulship during the domination of ] and instead chose retirement.{{sfn|Badian|2009|p=16}} During Cinna's dominance, Caesar was named as '']'' (a priest of ]) which led to his marriage to Cinna's daughter, ]. The religious taboos of the priesthood would have forced Caesar to forgo a political career; the appointment – one of the highest non-political honours – indicates that there were few expectations of a major career for Caesar.<ref>{{harvnb|Badian|2009|p=16|ps=. Badian cites {{harvnb|Suet. ''Iul.''|loc=1.2}} arguing that Caesar was actually appointed; because a divorced man could not be ''flamen Dialis'', the assertion that Caesar married one Cossutia then divorced her to marry Cornelia and become ''flamen'' in {{harvnb|Plut. ''Caes.''|loc=5.3}} is incorrect.}}</ref> In early 84 BC, Caesar's father died suddenly.{{sfn|Goldsworthy|2006|p=34}} After ]'s victory in the ] (82 BC), Cinna's ''acta'' were annulled. Sulla consequently ordered Caesar to abdicate and divorce Cinna's daughter. Caesar refused, implicitly questioning the legitimacy of Sulla's annulment. Sulla may have put Caesar on the ], though scholars are mixed.<ref>{{harvnb|Badian|2009|pp=16–17}}, stating Caesar was placed on the lists. Cf, stating Caesar was only summoned for interrogation, {{cite book |last=Hinard |first=François |title=Les proscriptions de la Rome républicaine |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-3UaAAAAIAAJ |publisher=Ecole française de Rome |date=1985 |pages=64 |isbn=978-2-7283-0094-5 |oclc=1006100534 |language=fr}}</ref> Caesar then went into hiding before his relatives and contacts among the ] were able to intercede on his behalf.<ref>{{harvnb|Badian|2009|pp=16–17|ps=, also rejecting claims that Caesar hid by bribing his pursuers: "this is an example of how the pervades our accounts and makes it difficult to get at the facts... cannot be true, since confiscation of his fortune went with his proscription".}}</ref> They then reached a compromise where Caesar would resign his priesthood but keep his wife and chattels; Sulla's alleged remark he saw "in many Mariuses"<ref>{{harvnb|Plut. ''Caes.''|loc=1.4}}; {{harvnb|Suet. ''Iul.''|loc=1.3}}.</ref> is apocryphal.<ref>{{harvnb|Badian|2009|p=17|ps=, noting also that Sulla never killed any fellow patricians.}}</ref> | |||

| After returning to Rome in ], Caesar was elected to the ]. Unfortunately, Caesar returned to Rome in the middle of the ] under the ex-] ]. The ] sent ] after legion to handle the rebellion, but each time Spartacus was victorious. In ], Caesar was elected a ] by the ], his first step in political life. Finally, in the year ], ] rose to the challenge presented by Spartacus. Caesar was one of the few men to ] for Crassus in trying to establish his command. The Senate appointed Crassus to the cause, and Crassus personally levied six brand new legions, and recruited the young Caesar to serve as one of his tribunes for his work as an advocate. After a series of defeats, Crassus finally overcame Spartacus in ]. During their time together, Caesar and Crassus would form a friendship that would later advance both of their careers in the years to come. But Caesar's triumph soon turned to disaster. | |||

| ] – wearing the ] ({{langx|la|corona civica}}). Caesar won the civic crown for his bravery at the ] in 81 BC.]] | |||

| In ], Caesar became a widower after Cornelia's death trying to deliver a stillborn son. In the same year, he lost his aunt Julia, to whom he was very attached. These two deaths left Caesar very much alone to raise a still infant daughter, ]. It was untraditional for Roman women to have great public funerals, but Caesar broke tradition and gave them both fine funerals. During the funerals, Caesar delivered ] speeches from the ]. Julia's funeral was filled with political connotations, since Caesar insisted on parading Marius's ]. Although Caesar was very fond of both women (according to Suetonius), these speeches were interpreted by his political opponents as ] for his upcoming election for the office of ]. | |||

| Caesar then left Italy to serve in the staff of the governor of Asia, ]. While there, he travelled to Bithynia to collect naval reinforcements and stayed some time as a guest of the king, ], though later invective connected Caesar to a homosexual relation with the monarch.{{sfn|Badian|2009|pp=17–18}}<ref>{{harvnb|Suet. ''Iul.''|loc=2–3}}; {{harvnb|Plut. ''Caes.''|loc=2–3}}; {{harvnb|Dio|loc=43.20}}.</ref> He then served at the ] where he won the ] for saving the life of a fellow citizen in battle. The privileges of the crown – the Senate was supposed to stand on a holder's entrance and holders were permitted to wear the crown at public occasions – whetted Caesar's appetite for honours. After the capture of Mytilene, Caesar transferred to the staff of ] in Cilicia before learning of Sulla's death in 78 BC and returning home immediately.{{sfn|Badian|2009|p=17}} He was alleged to have wanted to join in on the consul ]' revolt that year<ref>{{harvnb|Badian|2009|p=18}}, citing {{harvnb|Suet. ''Iul.''|loc=3}}.</ref> but this is likely literary embellishment of Caesar's desire for tyranny from a young age.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=35}} | |||

| ==Caesar's ''Cursus Honorum''== | |||

| ], in ''Cassell's History of England (1902)'']] | |||

| Afterward, Caesar attacked some of the Sullan aristocracy in the courts but was unsuccessful in his attempted prosecution of ] in 77 BC, who had recently returned from a proconsulship in Macedonia. Going after a less well-connected senator, he was successful the next year in prosecuting ] (later consul in 63 BC) for profiteering from the proscriptions but was forestalled when a tribune interceded on Antonius' behalf.<ref>{{harvnb|Alexander|1990|p=71}} (Trial 140) noting also that Tac. ''Dial.'', 34.7 wrongly places the trial in 79 BC; {{harvnb|Alexander|1990|pp=71–72}} (Trial 141).</ref> After these oratorical attempts, Caesar left Rome for Rhodes seeking the tutelage of the rhetorician ].{{sfn|Badian|2009|p=18}} While travelling, he was intercepted and ransomed by pirates in a story that was later much embellished. According to Plutarch and Suetonius, he was freed after paying a ransom of fifty ]s and responded by returning with a fleet to capture and execute the pirates. The recorded sum for the ransom is literary embellishment and it is more likely that the pirates were sold into slavery per ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Pelling |first=C B R |title=Plutarch: Caesar |date=2011 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-814904-0 |location=Oxford |oclc=772240772 |pages=139–41}} {{harvnb|Vell. Pat.|loc=2.42.3}} reports that the governor wanted to enslave and sell the pirates but that Caesar returned quickly and had them executed. Pelling believes the second part of Vell. Pat.'s narrative – along with other sources ({{harvnb|Plut. ''Caes.''|loc=1.8–2.7}}; {{harvnb|Suet. ''Iul.''|loc=4}}) – are literary embellishment and that the pirates were enslaved and sold.</ref> His studies were interrupted by the outbreak of the ] over the winter of 75 and 74 BC; Caesar is alleged to have gone around collecting troops in the province at the locals' expense and leading them successfully against Mithridates' forces.<ref>{{harvnb|Badian|2009|p=19|ps=, calling the story in {{harvnb|Suet. ''Iul.''|loc=4.2}} that Caesar called up auxiliaries and with them drove Mithridates' prefect from the province of Asia, "a striking example of the Caesar myth... difficult to believe".}}</ref> | |||

| Caesar was elected ] by the ] in ], at the age of thirty, as stipulated in the Roman '']''. He drew the lots and was assigned a quaestorship in ], a ] roughly situated in modern ] and part of southern ]. As an administrative and financial officer, the trip was largely uneventful, but it was while in ] that he had the famous encounter with a statue of ]. At the temple of ] in ], it was said that he broke down and cried. When asked why he would have such a reaction, his simple response was: "Do you think I have not just cause to weep, when I consider that Alexander at my age had conquered so many nations, and I have all this time done nothing that is memorable." | |||

| === Entrance to politics === | |||

| Caesar was released early from his office as quaestor, and allowed to return to Rome early. Despite any personal grief over the loss of his wife, of who all accounts suggest he loved dearly, Caesar was set to remarry in ] for political gain. This time, however, he chose an odd alliance. The granddaughter of Sulla, and daughter of Quintus Pompey, ], was to be his next wife. Now as a member of the Senate, thanks to his election earlier as quaestor, Caesar supported laws which were designed to grant ] unlimited powers in dealing with Cilician pirates in the Mediterranean. Obviously building a relationship with Rome's great general would play into his hands later. | |||

| While absent from Rome, in 73 BC, Caesar was co-opted into the ] in place of his deceased relative ]. The promotion marked him as a well-accepted member of the aristocracy with great future prospects in his political career.{{sfn|Goldsworthy|2006|p=78}} Caesar decided to return shortly thereafter and on his return was elected one of the ] for 71 BC.<ref>{{harvnb|Badian|2009|p=19}}; {{harvnb|Broughton|1952|pp=114, 125}}; {{harvnb|Vell. Pat.|loc=2.43.1}} (pontificate); {{harvnb|Plut. ''Caes.''|loc=5.1}} and {{harvnb|Suet. ''Iul.''|loc=5}} (military tribunate).</ref> There is no evidence that Caesar served in war – even though ] on ] was on-going – during his term; he did, however, agitate for the removal of Sulla's disabilities on the plebeian tribunate and for those who supported Lepidus' revolt to be pardoned.<ref>{{harvnb|Badian|2009|p=19}}, citing {{harvnb|Suet. ''Iul.''|loc=5}}.</ref> These advocacies were common and uncontroversial.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=63}} The next year, 70 BC, ] and ] were consuls and brought legislation restoring the plebeian tribunate's rights; one of the tribunes, with Caesar supporting, then brought legislation pardoning the Lepidan exiles.<ref>{{harvnb|Badian|2009|pp=19–20|ps=, also noting senatorial support for the pardons}}; {{harvnb|Broughton|1952|pp=126, 128, 130 n. 4|ps=, argues the tribunician law recalling the Lepidan exiles must postdate the consular law in 70 which removed Sulla's suppression of tribunician legislative initiative.}}</ref> | |||

| For his quaestorship in 69 BC, Caesar was allotted to serve under ] in ]. His election also gave him a lifetime seat in the Senate. However, before he left, his aunt Julia, the widow of Marius died and, soon afterwards, his wife Cornelia died shortly after bearing his only legitimate child, ]. He gave eulogies for both at public funerals.<ref>{{harvnb|Badian|2009|p=20}}; {{harvnb|Broughton|1952|p=132}}. {{harvnb|Badian|2009|p=21}} cites {{harvnb|Suet. ''Iul.''|loc=6.1}} for the incipit of Caesar's eulogy.</ref> During Julia's funeral, Caesar displayed the images of his aunt's husband Marius, whose memory had been suppressed after Sulla's victory in the civil war. Some of the Sullan nobles – including ] – who had suffered under the Marian regime objected, but by this point depictions of husbands in aristocratic women's funerary processions was common.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=43}} Contra Plutarch,{{sfn|Plut. ''Caes.''|loc=5.2–3}} Caesar's action here was likely in keeping with a political trend for reconciliation and normalisation rather than a display of renewed factionalism.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=43–46}} Caesar quickly remarried, taking the hand of Sulla's granddaughter ].<ref>{{harvnb|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=46|ps=, noting also that Plutarch omits this detail likely because it "would indeed have been embarrassing for his Marian representation of Caesar" (internal citations and quotation marks omitted).}}</ref> | |||

| Between the support of the laws regarding Pompey's command, Caesar served as the ] of the ]. The maintenance of this road, which stretched from Rome to ] and beyond to the heel of Italy's boot, was an important and high profile position. While it was enormously expensive on a personal basis, it gave a great deal of prestige to a young Senator, and Crassus' support certainly made it an achievable task for Caesar. All the while, Caesar continued to pursue his ] career until his election as ] in ], along with a young rival and member of the ] faction by the name of Bibulus. | |||

| === Aedileship and election as ''pontifex maximus'' === | |||

| This ] position was the next step in the Roman ] and was a grand opportunity for the master of the public spectacle. The ''curule aediles'' were responsible for such public duties as the construction and care of temples, maintenance of public buildings, traffic, and other aspects of Rome's daily life; perhaps most important of all, the staging of public games on state holidays and management of the ]. Caesar indebted himself to the point of near financial ruin during this time, but enhanced his image irreversibly with the common people. Caesar ended his year as ''aedile'' in glory but in bankruptcy. His debts reached several hundred gold talents (millions of ]s in today's currency) and threatened to be an obstacle for his future career. His co-aedile Bibulus was so unspectacular in comparison that he later commented in frustration that the entire year's aedileship was credited to Caesar alone, instead of both. | |||

| For much of this period, Caesar was one of ]'s supporters. Caesar joined with Pompey in the late 70s to support restoration of tribunician rights; his support for the law recalling the Lepidan exiles may have been related to the same tribune's bill to grant lands to Pompey's veterans. Caesar also supported the '']'' in 67 BC granting Pompey an extraordinary command against piracy in the Mediterranean and also supported the '']'' in 66 BC to reassign the Third Mithridatic War from its then-commander ] to Pompey.{{sfn|Gruen|1995|p=79–80}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Four years after his aunt Julia's funeral, in 65 BC, Caesar served as ] and staged lavish ] that won him further attention and popular support.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Mouritsen |first=Henrik |title=Plebs and politics in the late Roman Republic |date=2001 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=0-511-04114-4 |oclc=56761502 |page=97}} See also {{harvnb|Broughton|1952|p=158}} and {{harvnb|Plut. ''Caes.''|loc=6.1–4}}.</ref> He also restored the trophies won by Marius, and taken down by Sulla, over ] and the ].{{sfn|Broughton|1952|p=158}} According to Plutarch's narrative, the trophies were restored overnight to the applause and tears of joy of the onlookers; however, any sudden and secret restoration of this sort would not have been possible – architects, restorers, and other workmen would have to have been hired and paid for – nor would it have been likely that the work could have been done in a single night.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=46–47}} It is more likely that Caesar was merely restoring his family's public monuments – consistent with standard aristocratic practice and the virtue of {{lang|la|]}} – and, over objections from Catulus, these actions were broadly supported by the Senate.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=48–49}} | |||

| His success as ''aedile'' was, however, an enormous help for his election as '']'' (high priest) in ], following the death of the previous holder ]. This office meant a new house — the ''Domus Publica'' (public house) — in the ''Forum'', the responsibility of all Roman religious affairs and the custody of the ]s under his roof. For Caesar, it also meant a relief of his debts. The election put Caesar in a position of considerable power, with opportunity for income. The Pontifex was elected to a lifetime term and while technically not a political office, still provided considerable advantages in dealing with the Senate and ]. | |||

| In 63 BC, Caesar stood for the praetorship and also for the post of {{lang|la|]}},<ref>{{harvnb|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=64, 64 n. 129|ps=, noting that it is not clear which election was first; it is more likely, however, that elections were late and therefore that the pontifical election occurred first. Dio's claim of elections in December is clearly erroneous. {{harvnb|Broughton|1952|p=172 n. 3}}.}}</ref> who was the head of the ] and the highest ranking state religious official. In the pontifical election before the ], Caesar faced two influential senators: ] and ]. Caesar came out victorious. Many scholars have expressed astonishment that Caesar's candidacy was taken seriously, but this was not without historical precedent.<ref>{{harvnb|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=64–65|ps=, noting the victory of curule aedile ] in 212 over senior consulars and plebeian tribune ] over consulars.}}</ref> Ancient sources allege that Caesar paid huge bribes or was shamelessly ingratiating;<ref>{{harvnb|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=66}}, citing {{harvnb|Suet. ''Iul.''|loc=13}}; {{harvnb|Plut. ''Caes.''|loc=7.1–4}}; {{harvnb|Dio|loc=37.37.1–3}}.</ref> that no charge was ever laid alleging this implies that bribery alone is insufficient to explain his victory.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=67–68}} If bribes or other monies were needed, they may have been underwritten by Pompey, whom Caesar at this time supported and who opposed Catulus' candidacy.{{sfn|Gruen|1995|pp=80–81}} | |||

| Caesar's debut as Pontifex was however marked by a scandal. Following the death of his wife Cornelia, he had married ], a granddaughter of Sulla, in ]. As the wife of the Pontifex and an important ''matrona'' (]: married woman), Pompeia was responsible for the organization of the ] festival in December. These rites were exclusive to women and considered very sacred. However, ] managed to get in the house disguised as a woman. This was absolute sacrilege and Pompeia received a letter of ]. Caesar himself admitted that she could be innocent in the plot, but, as he said: "Caesar's wife, like the rest of Caesar's family, must be above suspicion." | |||

| Many sources also assert that Caesar supported the land reform proposals brought that year by plebeian tribune ], however, there are no ancient sources so attesting.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=69 n. 148}} Caesar also engaged in a collateral manner in the trial of ] by one of the plebeian tribunes – ] – for the murder of Saturninus in accordance with a ] some forty years earlier.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=71}}<ref>{{Harvnb|Alexander|1990|p=110|ps= (Trials 220–21).}}</ref> The most famous event of the year was the ]. While some of Caesar's enemies, including Catulus, alleged that he participated in the conspiracy,<ref>{{harvnb|Gruen|1995|p=80|ps=, citing Sall. ''Cat.'', 49.1–2.}} See also {{harvnb|Suet. ''Iul.''|loc=17}}.</ref> the chance that he was a participant is extremely small.<ref>{{harvnb|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=72–77|ps=, placing it around 2.5 per cent.}} {{harvnb|Gruen|1995|p=429 n. 107}} calls the view that Caesar was one of the masterminds of the conspiracy "long... discredited and requires no further refutation".</ref> | |||

| ] was an especially difficult year, not only for Caesar, but for the ] itself. Caesar ran for, and won, the office of ] for the year ]. Before he could even take office, however, the ] erupted putting Caesar in direct conflict with the ] once again. The result was the conviction to death of five notable Roman men, ]'s allies, without a trial. The only other option open was banishment, as imprisonment before trial was unheard of; if banished the men would simply have gone to take command of Catiline's armies in ]. The Senate deliberated on the matter, with Caesar one of the few men to speak up against the death penalty. | |||

| === Praetorship === | |||

| Towards the end of his praetorship, Caesar was again in serious jeopardy of prosecution for his debts. Crassus came to the rescue again, paying off a quarter of his 20 million '']'' balance. Eventually, by ], Caesar was finally assigned to serve as the ] of ], the province he served in as a quaestor. With this appointment, his creditors backed off, allowing that this position could be quite profitable. Leaving Rome even before he was officially to take over, Caesar was not taking chances. | |||

| Caesar won his election to the praetorship in 63 BC easily and, as one of the praetor-elects, spoke out that December in the Senate against executing certain citizens who had been arrested in the city conspiring with Gauls in furtherance of the conspiracy.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=85–86, 90}} Caesar's proposal at the time is not entirely clear. The earlier sources assert that he advocated life imprisonment without trial; the later sources assert he instead wanted the conspirators imprisoned pending trial. Most accounts agree that Caesar supported confiscation of the conspirators' property.<ref>{{harvnb|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=92}}. Earlier sources being Cic. ''Cat.'', 4.8–10 and Sall. ''Cat.'', 51.42. Later sources include {{harvnb|Plut. ''Caes.''|loc=7.9}} and {{harvnb|App. ''BCiv.''|loc=2.6}}.</ref> Caesar likely advocated the former, which was a compromise position that would place the Senate within the bounds of the {{lang|la|lex Sempronia de capite civis}}, and was initially successful in swaying the body; a later intervention by ], however, swayed the Senate at the end for execution.{{sfn|Gruen|1995|pp=281–82}} | |||

| ], consul in 63 BC, depicted in an 1889 ] denouncing Catiline and exposing his conspiracy before the Senate. When conspirators within the city were later arrested, Cicero referred their fate to the Senate, triggering a debate in which Caesar as praetor-elect participated.]] | |||

| Arriving in Hispania, Caesar developed a remarkable reputation as a military commander. Between ] and ], he won considerable victories over the local ] and ] tribes. During one of his victories, his men hailed him as ] in the field, which was a vital consideration in being eligible for a ] back in Rome. Caesar was now faced with a terrible dilemma, though. He wanted to run for ] for ] and would have to be present within the city of Rome to do so, but he also wanted to receive the honor of a triumph. The Optimates surely would use this against him, forcing him to wait outside the city, as was the custom, until they confirmed his triumph. The delay would force Caesar to miss his chance to run for consul and he made a fateful decision. In the summer of ], Caesar entered Rome to run for the highest political office in the Roman Republic. | |||

| During his year as praetor, Caesar first attempted to deprive his enemy Catulus of the honour of completing the rebuilt ], accusing him of embezzling funds, and threatening to bring legislation to reassign it to Pompey. This proposal was quickly dropped amid near-universal opposition.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=102}} He then supported the attempt by plebeian tribune ] to transfer the command against Catiline from the consul of 63, Gaius Antonius Hybrida, to Pompey. After a violent meeting of the ] in the forum, where Metellus came into fisticuffs with his tribunician colleagues Cato and ],{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=102–04}} the Senate passed a decree against Metellus – Suetonius claims that both Nepos and Caesar were deposed from their magistracies; this would have been a constitutional impossibility<ref>{{harvnb|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=107|ps=, citing {{harnvb|Suet. ''Iul.''|loc=16}}.}} Dio reports a ]. {{harvnb|Broughton|1952|p=173|ps=, citing {{harvnb|Dio|loc=37.41}}.}}</ref> – which led Caesar to distance himself from the proposals: hopes for a provincial command and need to repair relations with the aristocracy took priority.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=109}} He also was engaged in the ] affair, where ] sneaked into Caesar's house sacrilegiously during a female religious observance; Caesar avoided any part of the affair by divorcing his wife immediately – claiming that his wife needed to be "above suspicion"{{sfn|Plut. ''Caes.''|loc=10.9}} – but there is no indication that Caesar supported Clodius in any way.<ref>{{harvnb|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=110|ps=, adding in notes that the affair is usually interpreted as an attempt to destroy Clodius' career and that Caesar may have been a secondary target due to expectations that he would reject political pressure for a divorce.}}</ref> | |||

| ==First Triumvirate== | |||

| ]}}.{{sfn|Drogula|2019|pp=97–98}}]] | |||

| In ], Caesar's decision to forego a chance at a triumph for his achievements in Hispania put him in a position to run for ]. Even though Caesar had overwhelming popularity within the citizen assemblies, he had to manipulate formidable alliances within the Senate itself in order to secure his election. Already maintaining a solid friendship with the fabulously wealthy ], he approached Crassus' rival ] with the concept of a coalition. Pompey had already been considerably frustrated by the inability to get land reform for his eastern veterans and Caesar brilliantly patched up any differences between the two powerful leaders. | |||

| After his praetorship, Caesar was appointed to govern ] ''pro consule''.<ref>{{harvnb|Broughton|1952|pp=173, 180}}. Most sources give a proconsular dignity. After the Sullan era, all magistrates were prorogued ''pro consule''. {{cite web |last1=Badian |first1=Ernst |last2=Lintott |first2=Andrew |title=pro consule, pro praetore |website=Oxford Classical Dictionary |publisher=Oxford University Press |url=https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.5337 |year=2016|doi=10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.5337 |isbn=978-0-19-938113-5 }}</ref> Deeply indebted from his campaigns for the praetorship and for the pontificate, Caesar required military victory beyond the normal provincial extortion to pay them off.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=109–10}} He campaigned against the ] and ] and seized the Callaeci capital in northwestern Spain, bringing Roman troops to the Atlantic and seizing enough plunder to pay his debts.{{sfn|Broughton|1952|p=180}} Claiming to have completed the peninsula's conquest, he made for home after having been hailed {{lang|la|]}}.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=110–11}} When he arrived home in the summer of 60 BC, he was then forced to choose between a triumph and election to the consulship: either he could remain outside the {{lang|la|]}} (Rome's sacred boundary) awaiting a triumph or cross the boundary, giving up his command and triumph, to make a declaration of consular candidacy.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=111}} Attempts to waive the requirement for the declaration to be made in person were filibustered in the Senate by Caesar's enemy Cato, even though the Senate seemed to support the exception.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=112–13}} Faced with the choice between a triumph and the consulship, Caesar chose the consulship.<ref>{{harvnb|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=114}}; {{harvnb|Plut. ''Caes.''|loc=13}}; {{harvnb|Suet. ''Iul.''|loc=18.2}}.</ref> | |||

| The alliance (known today as the ]) was formed in late ], and remarkably remained a secret for some time. Pompey and Crassus agreed to use their wealth and clout to secure Caesar's consulship, and in return Caesar would lobby for both Pompey's and Crassus's political agenda. Caesar and Crassus were already the best of friends from a decade back, and he solidified his alliance with Pompey by giving him his own daughter ] in marriage. The alliance combined Caesar's enormous popularity with the ]s and legal reputation with Crassus's fantastic wealth and influence within the ] ] and Pompey's equally spectacular wealth, military reputation, and ] influence. With their help, Caesar won the election easily enough, but the Optimates managed to get Caesar's former co-aedile ] elected as the junior consul. | |||

| == First consulship and the Gallic Wars == | |||

| Once in office in ], Caesar's first order of business was to pass a law that required the public release of all debates and procedures of the Senate. Next on the agenda was the appeasement of Pompey. Unused land in parts of Italy would be restored and offered to Pompey's veterans. Doing so would not only alleviate the problem of the unemployed mob in Rome but would satisfy Pompey and his legions. Still ] and the Optimate faction opposed the concept simply because it was Caesar's idea. Caesar rebuked the Senate and took it directly to the people. | |||

| {{main|Military campaigns of Julius Caesar|First Triumvirate}} | |||

| ] depicting Julius Caesar, dated to February–March 44 BC{{snd}}the goddess ] is shown on the reverse, holding ] and a scepter. Caption: CAESAR IMP. M. / L. AEMILIVS BVCA.]] | |||

| Caesar stood for the consulship of 59 BC along with two other candidates. His political position at the time was strong: he had supporters among the families which had supported Marius or Cinna; his connection with the Sullan aristocracy was good; his support of Pompey had won him support in turn. His support for reconciliation in continuing aftershocks of the civil war was popular in all parts of society.{{sfn|Gruen|2009|p=28}} With the support of Crassus, who supported Caesar's joint ticket with one ], Caesar won. Lucceius, however, did not and the voters returned ] instead, one of Caesar's long-standing personal and political enemies.{{sfn|Gruen|2009|pp=30–31}}<ref>{{harvnb|Gruen|2009|p=28}}; {{harvnb|Broughton|1952|pp=158, 173|ps=. Bibulus was Caesar's colleague both in the curule aedileship and the praetorship. They clashed politically in both magistracies.}} On credit for the aedilican games, see {{harvnb|Suet. ''Iul.''|loc=10}}, {{harvnb|Dio|loc=37.8.2}}, and {{harvnb|Plut. ''Caes.''|loc=5.5}}.</ref> | |||

| === First consulship === | |||

| While speaking before the citizen assemblies, Caesar asked his co-consul Bibulus his feelings on the bill, as it was important to have the support of both standing consuls. His reply was simply to say that the bill would not be passed even if everyone else wanted it. At this point the so-called first triumvirate was made publicly known with both Pompey and Crassus voicing public approval of the measure in turn. The law carried with overwhelming public support and Bibulus retired to his home in disgrace. Bibulus spent the remainder of his consular year trying to use religious ]s to declare Caesar's laws as ], in an attempt to bog down the political system. Instead, however, he simply gave Caesar complete autonomy to pass almost any proposal he wanted to. After Bibulus' withdrawal, the year of the consulship of Caesar and Bibulus was often referred to jokingly thereafter as the year of "Julius and Caesar". | |||

| {{further|First Triumvirate}} | |||

| After the elections, Caesar reconciled Pompey and Crassus, two political foes, in a three-way alliance misleadingly<ref>{{harvnb|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=119|ps=. "n alliance which in modern times has come, quite misleadingly, to be called the 'First Triumvirate'... the very phrase... invokes a misleading teleology. Furthermore, it is almost impossible to use without adopting some version of the view that it was a kind of conspiracy against the republic".}}</ref> termed the "First Triumvirate" in modern times.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Ridley |first=R |year=1999 |title=What's in the Name: the so-called First Triumvirate |journal=Arctos: Acta Philological Fennica |volume=33 |pages=133–44 |url=https://journal.fi/arctos/article/download/85987/44908 }} The first usage of the term was in 1681.</ref> Caesar was still at work in December of 60 BC attempting to find allies for his consulship and the alliance was finalised only some time around its start.{{sfn|Gruen|2009|p=31}} Pompey and Crassus joined in pursuit of two respective goals: the ratification of ] and the bailing out of tax farmers in Asia, many of whom were Crassus' clients. All three sought the extended patronage of land grants, with Pompey especially seeking the promised land grants for his veterans.<ref>{{harvnb|Gruen|2009|p=31}}; {{harvnb|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=121–22|ps=, noting that the Senate had approved distribution of lands to Pompey's veterans from the ] all the way back in 70 BC.}}</ref> | |||

| Already secure with Crassus, by marrying the daughter of his client ], Caesar next strengthened his alliance with Pompey. Pompey was married to Caesar's daughter Julia. In what seemed to be a mere political edge, the marriage blossomed into romance by all accounts. Caesar was given the ]ship of ] and ], granting him the opportunity to match political victories with military glory. This five-year term, unprecedented for an area that was relatively secure, was an obvious sign of Caesar's ambition for external conquests. Caesar's future campaigns would all be conducted at his own discretion. In an additional stroke of luck, the current governor of ] died, and this province was assigned to Caesar as well. | |||

| Caesar's first act was to ] the minutes of the Senate and the assemblies, signalling the Senate's accountability to the public. He then brought in the Senate a bill – crafted to avoid objections to previous land reform proposals and any indications of radicalism – to purchase property from willing sellers to distribute to Pompey's veterans and the urban poor. It would be administered by a board of twenty (with Caesar excluded), and financed by Pompey's plunder and territorial gains.{{sfn|Gruen|2009|p=32}} Referring it to the Senate in hope that it would take up the matter to show its beneficence for the people,{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=125–29}} there was little opposition and the obstructionism that occurred was largely unprincipled, firmly opposing it not on grounds of public interest but rather opposition to Caesar's political advancement.{{sfn|Gruen|2009|p=32}} Unable to overcome Cato's filibustering, he moved the bill before the people and, at a public meeting, Caesar's co-consul Bibulus threatened a permanent veto for the entire year. This clearly violated the people's well-established legislative sovereignty{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=130, 132}} and triggered a riot in which Bibulus' fasces were broken, symbolising popular rejection of his magistracy.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=138}} The bill was then voted through. Bibulus attempted to induce the Senate to nullify it on grounds it was passed by violence and contrary to the auspices but the Senate refused.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=139–40}} | |||

| As ] came to a close, Caesar had the support of the people, along with the two most powerful men in Rome (aside from himself), and the opportunity for infinite glory in Gaul. At the age of forty, while already holding the highest office in Rome and defeating his enemies at every turn, the true greatness of his career was yet to come. Marching quickly to the relative safety of his provinces, to invoke his five year ] and avoid prosecution, Caesar was about to alter the ] landscape of the ancient world. | |||

| Caesar also brought and passed a one-third write-down of tax farmers' arrears for Crassus and ratification of Pompey's eastern settlements. Both bills were passed with little or no debate in the Senate.{{sfn|Wiseman|1994|p=372}} Caesar then moved to extend his agrarian bill to Campania some time in May; this may be when Bibulus withdrew to his house.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=143 (Bibulus), 147 (dating to May)}} Pompey, shortly thereafter, also wed Caesar's daughter Julia to seal their alliance.{{sfn|Wiseman|1994|p=374}} An ally of Caesar's, plebeian tribune ] moved the '']'' assigning the provinces of ] and ] to Caesar for five years.{{sfn|Drogula|2019|p=137}}<ref>{{harvnb|Gruen|2009|p=33}}, noting that the {{lang|la|lex Vatinia}} was "no means unprecedented... or even controversial".</ref> Suetonius' claim that the Senate had assigned to Caesar the {{lang|la|silvae callesque}} ("woods and tracks") is likely an exaggeration: fear of Gallic invasion had grown in 60 BC and it is more likely that the consuls had been assigned to Italy, a defensive posture that Caesarian partisans dismissed as "mere 'forest tracks'".<ref>{{harvnb|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=175}}, citing {{Cite journal |last=Balsdon |first=J P V D |date=1939 |title=Consular provinces under the late Republic – II. Caesar's Gallic command |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/297143 |journal=Journal of Roman Studies |volume=29 |pages=167–83 |doi=10.2307/297143 |jstor=297143 |s2cid=163892529 |issn=0075-4358}} Moreover, Caesar's eventual provinces of Trans- and Cisalpine Gaul had been assigned to the consuls of 60 and therefore would have been unavailable. {{Cite journal |last=Rafferty |first=David |date=2017 |title=Cisalpine Gaul as a consular province in the late Republic |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/45019257 |journal=Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte |volume=66 |issue=2 |pages=147–172 |doi=10.25162/historia-2017-0008 |jstor=45019257 |s2cid=231088284 |issn=0018-2311}}</ref> The Senate was also persuaded to assign to Caesar ] as well, subject to annual renewal, most likely to control his ability to make war on the far side of the Alps.{{sfnm|Morstein-Marx|2021|1pp=176–77|Gruen|2009|2p=34}} | |||

| ==Gallic Wars== | |||

| Caesar took official command of his provinces of Illyricum, Cisalpine Gaul and Transalpine Gaul in ]. Beyond the province of Transalpine Gaul was a vast land comprising modern France, called Gallia Comata, where loose ]s of ]ic tribes maintained varying relationships with Rome. However, as soon as he took office, a Celtic tribe living in modern day ], the ], had planned a move from the ] region to the west of modern France. In order to make such a move, however, the Helvetii would have to march not only through Roman-controlled territory, but that of the Roman allied ] tribe as well. Other Gallic Celts and people within the province of ] feared that the Helvetii would not just move through as they proposed, but would plunder everything in their path as they went. Without question, Caesar opposed the idea and hastily recruited two more fresh legions in preparation. | |||

| Some time in the year, perhaps after the passing of the bill distributing the Campanian land<ref>{{harvnb|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=143}}: {{harvnb|Dio|loc=38.6.5}} and {{harvnb|Suet. ''Iul.''|loc=20.1}} say around late January; {{harvnb|Plut. ''Pomp.''|loc=48.5}} says in early May; {{harvnb|Vell. Pat.|loc=2.44.5}} says May.</ref> and after these political defeats, Bibulus withdrew to his house. There, he issued edicts in absentia, purporting unprecedentedly to cancel all days on which Caesar or his allies could hold votes for religious reasons.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=142–44}} Cato too attempted symbolic gestures against Caesar, which allowed him and his allies to "feign victimisation"; these tactics were successful in building revulsion to Caesar and his allies through the year.<ref>{{harvnb|Gruen|2009|p=34|ps=, also citing {{harvnb|Suet. ''Iul.''|loc=20.2}} – the "consulship of Julius and Caesar" – as part of Catonian propaganda.}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=150–51|ps=, noting that Bibulus' voluntary seclusion "presented the image of the city dominated by one man ... unchecked by a colleague".}}</ref> This opposition caused serious political difficulties to Caesar and his allies, belying the common depiction of triumviral political supremacy.{{sfn|Gruen|2009|p=34}} Later in the year, however, Caesar – with the support of his opponents – brought and passed the {{lang|la|]}} to crack down on provincial corruption.{{sfn|Drogula|2019|pp=138–39, noting Cato's support of Caesar's anti-corruption bill and the possibility that Cato gave input for some of its provisions}} When his consulship ended, Caesar's legislation was challenged by two of the new praetors but discussion in the Senate stalled and was regardless dropped. He stayed near the city until some time around mid-March.<ref>{{harvnb|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=182–83, 182 n. 260}}, citing {{harvnb|Suet. ''Iul.''|loc=23.1}}; pace {{harvnb|Ramsey|2009|p=38}}.</ref> | |||

| Several other local tribes joined the Helvetii in lesser numbers making the entire force among the largest and most powerful in all of Gaul. In total, according to Caesar, nearly 370,000 tribesmen were gathered, of which about 260,000 were women, children and other non-combatants. After setting off, and disregarding Caesar's objection, the two forces inevitably met. After several skirmishes, Caesar occupied the high ground with his six legions, and lured the enemy into a poorly matched battle. Near the Aeduan capital, Caesar crushed the Helvetii, slaughtering the enemy wholesale with little regard for combat status. According to Caesar himself, of the 370,000 enemy present, only 130,000 survived the battle. In the next few days following the battle while chasing down the fleeing enemy, it seems that at least another 20,000 were killed. Around the same time, in late ], the ] leader ], chieftain of the Germanic ], lead an invasion of Gaul and raided the border regions, but Caesar quelled the situation at that point by arranging an alliance with the Germans in early ]. He forced the Germans back east across the ], and used the "defense of Roman allies" as his cause to continue north in conquest. | |||

| === Campaigns in Gaul === | |||

| In the spring of ], Caesar was in Cisalpine Gaul attending to the administration of his governorship. Despite cries of great thanks from various Gallic tribes, discontent was growing. Word came to Caesar that a confederation of northern Gallic tribes under the ] was building to confront the Roman presence in Gaul. Caesar hurried back to his legions, raising two new legions of mainly Gallic "citizens" in the meantime, bringing his total to eight. | |||

| {{main|Gallic Wars}} | |||

| ] | |||

| During the Gallic Wars, Caesar wrote his ''Commentaries'' thereon, which were acknowledged even in his time as a Latin literary masterwork. Meant to document Caesar's campaigns in his own words and maintain support in Rome for his military operations and career, he produced some ten volumes covering operations in Gaul from 58 to 52 BC.{{sfn|Goldsworthy|2006|pp=186–87}} Each was likely produced in the year following the events described and was likely aimed at the general, or at least literate, population in Rome;{{sfn|Goldsworthy|2006|p=188–89}} the account is naturally partial to Caesar – his defeats are excused and victories highlighted – but it is almost the sole source for events in Gaul in this period.{{sfn|Goldsworthy|2006|pp=189–90}} | |||

| Gaul in 58 BC was in the midst of some instability. Tribes had raided into Transalpine Gaul and there was an on-going struggle between two tribes in central Gaul which collaterally involved Roman alliances and politics. The divisions within the Gauls – they were no unified bloc – would be exploited in the coming years.{{sfn|Goldsworthy|2006|p=204}} The first engagement was in April 58 BC when Caesar prevented the migrating ] from moving through Roman territory, allegedly because he feared they would unseat a Roman ally.{{sfn|Goldsworthy|2006|pp=205, 208–10}} Building a wall, he stopped their movement near Geneva and – after raising two legions – defeated them at the ] before forcing them to return to their original homes.{{sfn|Goldsworthy|2016|pp=212–15}} He was drawn further north responding to requests from Gallic tribes, including the ], for aid against ] – king of the ] and a declared friend of Rome by the Senate during Caesar's own consulship – and he defeated them at the ].{{sfn|Goldsworthy|2016|p=217}} Wintering in northeastern Gaul near the ] in the winter of 58–57, Caesar's forward military position triggered an uprising to remove his troops; able to eke out a victory at the ], Caesar spent much of 56 BC suppressing the Belgae and dispersing his troops to campaign across much of Gaul, including against the ] in what is now ].{{sfn|Goldsworthy|2016|p=220}} At this point, almost all of Gaul – except its central regions – fell under Roman subjugation.{{sfn|Boatwright|2004|p=242}} | |||

| As Caesar arrived, likely in July ], the rumors of Gallic opposition proved true. Caesar moved quickly, surprising Gallic tribes before they could join the opposition, and made fast allies of them. The Belgae, in reprisal against this, began to attack. With eight legions the Romans crushed the attack in a hard fought affair. The victory was two fold for Caesar. It not only was a victory in the field, but a political and propaganda win as well. By defending his "allies" from external aggression, he could now easily secure the necessary legalities to continue aggression against the Belgae. Though it would be another difficult campaign, this was exactly the sort of fortune that Caesar wanted. Caesar continued north, conquering all in his path, either through politics or by force. | |||

| ] throws down his arms at the feet of Julius Caesar, painting by ] in 1899. ], ], France.]] | |||

| As the campaign year of ] opened, Caesar found that Gaul still was not quite ready for Roman occupation. Caesar sent his generals to every corner of Gaul, quelling any Gallic resistance in their way. ], son of ], was sent to ] with twelve legionary ]s to subdue the tribes there. With the help of Gallic '']'', Crassus quickly brought Roman control to the westernmost portion of Gaul. ], the young future assassin of Caesar, was sent north to modern day ] to build a fleet amongst the ]. The Veneti controlled the waterways with a formidable fleet of their own and were augmented by ]. At first the Gallic vessels outmatched the Romans, and Brutus could do little to hamper Venetian operations. Roman ingenuity took over, however, and they began using hooks launched by archers to grapple the Venetian ships to their own. Before long, the Veneti were completely defeated, and like many tribes before them, sold into ]. | |||

| Seeking to buttress his military reputation, he engaged Germans attempting to cross the Rhine, which marked it as a Roman frontier;{{sfn|Boatwright|2004|p=242}} displaying Roman engineering prowess, he here built a ] in a feat of engineering meant to show Rome's ability to project power.{{sfn|Goldsworthy|2016|p=203}} Ostensibly seeking to interdict British aid to his Gallic enemies, he led expeditions into southern Britain in 55 and 54 BC, perhaps seeking further conquests or otherwise wanting to impress readers in Rome; Britain at the time was to the Romans an "island of mystery" and "a land of wonder".{{sfnm|Goldsworthy|2016|1pp=221–22|Boatwright|2004|2p=242}} He, however, withdrew from the island in the face of winter uprisings in Gaul led by the ] and ] starting in late 54 BC which ambushed and virtually annihilated a legion and five cohorts.{{sfn|Goldsworthy|2016|p=222}} Caesar was, however, able to lure the rebels into unfavourable terrain and routed them in battle.{{sfn|Goldsworthy|2016|p=223}} The next year, a greater challenge emerged with the uprising of most of central Gaul, led by ] of the ]. Caesar was initially defeated at ] before ]. After becoming himself besieged, Caesar won a major victory which forced Vercingetorix's surrender; Caesar then spent much of his time into 51 BC suppressing any remaining resistance.{{sfnm|Goldsworthy|2016|1pp=229–32, 233–38|Boatwright|2004|2p=242}} | |||

| In all, dozens of tribes were forced to surrender to Roman domination and hundreds of thousands of prisoners were sent back to Rome as slaves. With the defeat of the Gallic resistance, Caesar next began to focus his attention across the ]. Still, the conquest was not quite as complete as it seemed. First Caesar would have to deal with more Germanic incursions before he could cross to ]. And despite his confidence, the Gallic tribes were not nearly as subdued as he thought. For now, though, Caesar returned to Cisalpine Gaul to attend to political matters in Rome. | |||

| == |

=== Politics, Gaul, and Rome === | ||

| In the initial years from the end of Caesar's consulship in 59 BC, the three so-called triumvirs sought to maintain the goodwill of the extremely popular ],<ref>{{harvnb|Gruen|1995|p=98|ps=. "It should no longer be necessary to refute the older notion that Clodius acted as agent or tool of the triumvirate". Clodius was an independent agent not beholden to the triumvirs or any putative popular party. {{cite journal |last=Gruen |first=Erich S |title=P. Clodius: Instrument or Independent Agent? |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/1086053 |journal=Phoenix |volume=20 |issue=2 |pages=120–30 |date=1966 |issn=0031-8299 |jstor=1086053 |doi=10.2307/1086053}}}}</ref> who was ] in 58 BC and in that year successfully sent Cicero into exile. When Clodius took an anti-Pompeian stance later that year, he unsettled Pompey's eastern arrangements, started attacking the validity of Caesar's consular legislation, and by August 58 forced Pompey into seclusion. Caesar and Pompey responded by successfully backing the election of magistrates to recall Cicero from exile on the condition that Cicero would refrain from criticism or obstruction of the allies.{{sfn|Ramsey|2009|pp=37–38}}<ref>{{harvnb|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=194|ps=, noting Caesar's opposition – in early 58 BC – to Cicero's banishment. Caesar offered Cicero a position on his staff which would have conferred immunity from prosecution but Cicero refused. {{harvnb|Ramsey|2009|p=37}}.}}</ref>{{sfn|Ramsey|2009|p=39}} | |||

| By ], as Caesar was pushing Roman control throughout the entire Gallic province, the political situation in Rome was dangerously falling apart. In the midst of planning his next steps in Gaul, Britain and ], Caesar returned to Cisalpine Gaul and knew he had to reaffirm support within the Senate. Pompey was in northern ] attending to his duties with the grain commission, and Crassus went to ] to meet with Caesar. He instead, called them both to ] for a conference, and the three ]s were joined by up to 200 Senators. Though support in Rome was unravelling, this meeting showed the scope and size of the ‘triumvirate’ as being a much larger coalition than just three men. However, Caesar needed Crassus and Pompey to get along in order to hold the whole thing together. Caesar had to have his command extended in order to ensure safety from ] and ]. | |||

| Politics in Rome fell into violent street clashes between Clodius and two tribunes who were friends of Cicero. With Cicero now supporting Caesar and Pompey, Caesar sent news of Gaul to Rome and claimed total victory and pacification. The Senate at Cicero's motion voted him an unprecedented fifteen days of thanksgiving.<ref>{{harvnb|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=220|ps=, citing Gelzer, "this extraordinary honour... cut the ground from under the feet of those who maintained that since 58 Caesar had held his position illegally"; Morstein-Marx also rejects the claim of senatorial duress at {{harvnb|Plut. ''Caes.''|loc=21.7–9}}.}}</ref> Such reports were necessary for Caesar, especially in light of senatorial opponents, to prevent the Senate from reassigning his command in Transalpine Gaul, even if his position in Cisalpine Gaul and Illyricum was guaranteed by the ''lex Vatinia'' until 54 BC.{{sfnm|Morstein-Marx|2021|1pp=196, 220|Ramsey|2009|2pp=39–40}} His success was evidently recognised when the Senate voted state funds for some of Caesar's legions, which until this time Caesar had paid for personally.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=220–21}} | |||

| An agreement was reached in which Caesar would have his extension while granting Pompey and Crassus a balance of power opportunity. Pompey and Crassus were to be elected as joint consuls for ], with Pompey receiving ] as his province and Crassus to get ]. Pompey, jealous over Caesar’s growing army, wanted the security of a provincial command with legions, and Crassus wanted the opportunity for military glory and plunder to the east in ]. With the matter resolved, Crassus and Pompey returned to Rome to stand for the elections of ]. Despite bitter resistance from the Optimates, including a delay in the election, the two were eventually confirmed as consuls. Caesar took no chances however, and sent his ], Publius Crassus, back to Rome with 1,000 men to "keep order". The presence of these men, along with the popularity of Crassus and Pompey went a long way to stabilize the situation. Caesar quickly returned to Gaul to set into motion the first ] | |||

| The three allies' relations broke down in 57 BC: one of Pompey's allies challenged Caesar's land reform bill and the allies had a poor showing in the elections that year.{{sfn|Ramsey|2009|pp=39–40}} With a real threat to Caesar's command and {{lang|la|acta}} brewing in 56 BC under the aegis of the unfriendly consuls, Caesar needed his allies' political support.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=229}} Pompey and Crassus too wanted military commands. Their combined interests led to a renewal of the alliance; drawing in the support of ] and his younger brother Clodius for the consulship of 54 BC, they planned second consulships with following governorships in 55 BC for both Pompey and Crassus. Caesar, for his part, would receive a five-year extension of command.{{sfnm|Ramsey|2009|1pp=41–42|Morstein-Marx|2021|2p=232}} | |||

| Before Caesar could focus on Britain, a German invasion across the Rhine into ] territory forced his attention on ]. The invaders sent ambassadors to Caesar saying they only desired peace, but Caesar demanded their removal from Gaul and marched his legions against them. Before Caesar attacked, his ] was attacked by surprise and seventy-eight Romans were killed. A full-scale assault was then launched on the German camp and according to Caesar, 430,000 leaderless German men, women and children were assembled. The Romans butchered indiscriminately, sending the mass of people fleeing to the Rhine, where many more succumbed to the river. In the end, there is no account of how many were killed, but Caesar also claims to have not lost a single man. | |||

| Cicero was induced to oppose reassignment of Caesar's provinces and to defend a number of the allies' clients; his gloomy predictions of a triumviral set of consuls-designate for years on end proved an exaggeration when, only by desperate tactics, bribery, intimidation and violence were Pompey and Crassus elected consuls for 55 BC.{{sfnm|Ramsey|2009|1p=43|Morstein-Marx|2021|2pp=232–33}} During their consulship, Pompey and Crassus passed – with some tribunician support – the {{lang|la|lex Pompeia Licinia}} extending Caesar's command and the ] giving them respective commands in Spain and Syria,{{sfnm|Ramsey|2009|1p=44|Morstein-Marx|2021|2pp=232–33}} though Pompey never left for the province and remained politically active at Rome.{{sfn|Gruen|1995|p=451}} The opposition again unified against their heavy-handed political tactics – though not against Caesar's activities in Gaul<ref>{{harvnb|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=238}}, citing Cic. ''Sest.'', 51, "hardly anyone has lost popularity among the citizens for winning wars".</ref> – and defeated the allies in the elections of that year.{{sfn|Ramsey|2009|p=44}} | |||

| With the situation secure on the Gallic side of the river, Caesar decided it was time to settle the matter with the aggressive Germans once and for all, lest they invade again. It was decided, in order to impress the Germans and the Roman people that bridging the Rhine would have the most significant effect. By June of ], Caesar became the first Roman to cross the Rhine into Germanic territory. In so doing, a monstrous wooden bridge was built in only ten days, stretching over 300 feet across the great river. This alone assuredly, impressed the Germans and Gauls, who had little comparative capability in bridge building. Within a short time of his crossing, nearly all tribes within the region sent ]s along with messages of peace. | |||

| The ambush and destruction in Gaul of a legion and five cohorts in the winter of 55–54 BC produced substantial concern in Rome about Caesar's command and competence, evidenced by the highly defensive narrative in Caesar's ''Commentaries''.<ref>{{harvnb|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=241ff|ps=, citing {{harvnb|Caes. ''BGall.''|loc=5.26–52}}.}}</ref> The death of Caesar's daughter and Pompey's wife Julia in childbirth {{circa|late August 54}} did not create a rift between Caesar and Pompey.<ref>{{harvnb|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=272 n. 42|ps=: "Gruen.. and Raaflaub... have effectively disposed of the old idea, too heavily influenced by ", citing {{harnvb|Plut. ''Caes.''|loc=28.1}} and {{harvnb|Plut. ''Pomp.''|loc=53.6–54.2}}, "that Pompey had now turned against Caesar... since Julia's death in 54".}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Ramsey|2009|p=46|ps=: "Despite the fact that Pompey declined Caesar's later offer to form another marriage connection, their political alliance showed no signs of strain for the next several years".}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Gruen|1995|pp=451–52, 453|ps=: "Julia's death came in the late summer of 54 if it opened a breach between Pompey and Caesar, there is no sign of it in subsequent months... The evidence indicates no change in the relationship during 53"; "Julia's death provoked no change in the contract Caesar did not cut Pompey out of his will until the outbreak of civil war".}}</ref> At the start of 53 BC, Caesar sought and received reinforcements by recruitment and a private deal with Pompey before two years of largely unsuccessful campaigning against Gallic insurgents.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=243–44}} In the same year, Crassus's campaign ended in disaster at the ], culminating in his death at the hands of the ]. When in 52 BC Pompey started the year with a sole consulship to restore order to the city,<ref>{{cite journal |last=Ramsey |first=J T |date=2016 |title=How and why was Pompey made sole consul in 52 BC? |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/45019234 |journal=Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte |volume=65 |issue=3 |pages=298–324 |doi=10.25162/historia-2016-0017 |jstor=45019234 |s2cid=252459421 |issn=0018-2311}}</ref> Caesar was in Gaul suppressing insurgencies; after news of his victory at Alesia, with the support of Pompey he received twenty days of thanksgiving and, pursuant to the "Law of the Ten Tribunes", the right to stand for the consulship in absentia.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=247–48, 260, 265–66}}{{sfn|Wiseman|1994|p=412}} | |||

| Only one tribe resisted, fleeing their towns rather than submit to Caesar. The Romans made an example of them by burning their stores and their villages before receiving word that the ] were beginning to assemble in opposition. Caesar, rather than risk this glorious achievement in a pitched battle with a fierce foe, decided that discretion was the better part of valor. After spending only eighteen days in ], the Romans returned across the Rhine, burning their bridge in the process. With that short diversion, Caesar secured peace among the Germans, as the Suevi remained relatively peaceful for some time after, and secured a crucial alliance with the Ubii. His rear secured, Caesar looked for another glorious Roman ‘first’ and moved his body north to prepare for the invasion of Britain. | |||

| == Civil war == | |||

| Even after an unsuccessful first invasion, Caesar succeeded in invading a second time with the largest naval invasion in history until the ], nearly 2,000 years later. At year's end in ], Caesar had traveled to the farthest point in the known world and held most of Gaul firmly in his hands. But not all was going Caesar's way. In ], his only daughter, ], died in childbirth, leaving both Pompey and Caesar heartbroken. And to make matters worse, Crassus had been killed in ] during his ill-fated campaign in ]. Without Crassus or Julia, Pompey began to drift towards the Optimates faction, and relations with Caesar withered. Still away in Gaul, Caesar tried to secure Pompey's support by offering him one of his nieces in marriage, but Pompey refused. Instead, Pompey married ], the daughter of ], one of Caesar's greatest enemies. | |||

| {{main|Caesar's civil war}} | |||

| {{further|Alexandrine war|Early life of Cleopatra VII|Reign of Cleopatra VII}} | |||

| ] made during the reign of ] (27 BC{{snd}}14 AD), a copy of an original bust from 70 to 60 BC, ], Italy]] | |||

| From the period 52 to 49 BC, trust between Caesar and Pompey disintegrated.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=258|ps=. See also Appendix 4 in the same book, analysing the conflict between Caesar and Pompey in terms of a ].}} In 51 BC, the consul ] proposed recalling Caesar, arguing that his ''provincia'' (here meaning "task") in Gaul – due to his victory against Vercingetorix in 52 – was complete; it evidently was incomplete as Caesar was that year fighting the ]<ref>{{harvnb|Wiseman|1994|p=414|ps=, citing {{harvnb|Caes. ''BGall.''|loc=8.2–16}}.}}</ref> and regardless the proposal was vetoed.{{sfnm|Morstein-Marx|2021|1p=270|Drogula|2019|2p=223}} That year, it seemed that the conservatives around Cato in the Senate would seek to enlist Pompey to force Caesar to return from Gaul without honours or a second consulship.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=273}} Cato, Bibulus, and their allies, however, were successful in winning Pompey over to take a hard line against Caesar's continued command.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=272, 276, 295 (identities of Cato's allies)}} | |||

| As 50 BC progressed, fears of civil war grew; both Caesar and his opponents started building up troops in southern Gaul and northern Italy, respectively.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=291}} In the autumn, Cicero and others sought disarmament by both Caesar and Pompey, and on 1 December 50 BC this was formally proposed in the Senate.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=292–93}} It received overwhelming support – 370 to 22 – but was not passed when ] dissolved the meeting.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=297}} That year, when a rumour came to Rome that Caesar was marching into Italy, both consuls instructed Pompey to defend Italy, a charge he accepted as a last resort.<ref>{{harvnb|Wiseman|1994|pp=412–22|ps=, citing {{harvnb|App. ''BCiv.''|loc=2.30–31}} and {{harvnb|Dio|loc=40.64.1–66.5}}.}}</ref> At the start of 49 BC, Caesar's renewed offer that he and Pompey disarm was read to the Senate and was rejected by the hardliners.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=304}} A later compromise given privately to Pompey was also rejected at their insistence.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=306}} On 7 January, his supportive tribunes were driven from Rome; the Senate then declared Caesar an enemy and it issued its '']''.{{sfn|Morstein-Marx|2021|p=308}} | |||

| New discontent was brewing among the tribes of south-central Gaul. Among those tribes were the ]. Initially hesitant, a young chieftan, ], came to the forefront to rally the Gauls. Other neighboring tribes soon joined the growing revolt, especially in the absence of the legions who occupied the northern and eastern portions of Gaul. Caesar had to make haste from Cisalpine Gaul and joined his army in the late winter/early spring of ]. Caesar had no choice but to consolidate his forces against the formidable revolt. | |||

| There is scholarly disagreement as to the specific reasons why Caesar marched on Rome. A very popular theory is that Caesar was forced to choose – when denied the immunity of his proconsular tenure – between prosecution, conviction, and exile or civil war in defence of his position.{{sfnm|Boatwright|2004|1p=247|Meier|1995|2pp=1, 4|Mackay|2009|3pp=279–81|Wiseman|1994|4p=419}}{{sfn|Ehrhardt|1995|p=30. "Everyone knows that Caesar crossed the Rubicon because put on trial, found guilty and have his political career ended... Yet over thirty years ago, Shackleton Bailey, in less than two pages of his introduction to Cicero's ''Letters to Atticus'', destroyed the basis for this belief, and... no one has been able to rebuild it"}} Whether Caesar actually would have been prosecuted and convicted is debated. Some scholars believe the possibility of successful prosecution was extremely unlikely.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Morstein-Marx |first=Robert |date=2007 |title=Caesar's alleged fear of prosecution and his "ratio absentis" in the approach to the civil war |journal=Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte |volume=56 |issue=2 |pages=159–78 |doi=10.25162/historia-2007-0013 |jstor=25598386|s2cid=159090397 |issn=0018-2311}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Morstein-Marx|2021|pp=262–63}}, explaining: | |||