| Revision as of 14:43, 9 March 2010 edit66.16.66.62 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 10:10, 15 December 2024 edit undoDB1729 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers138,016 editsm correct nameNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|1865 children's novel by Lewis Carroll}} | |||

| {{redirect|Alice in Wonderland}} | |||

| {{Redirect|Alice in Wonderland}} | |||

| {{Refimprove|date=November 2008}} | |||

| {{Use British English|date=September 2013}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=December 2014}} | |||

| {{Infobox Book | |||

| {{Infobox book | |||

| | name = Alice's Adventures in Wonderland | |||

| | |

| name = Alice's Adventures in Wonderland | ||

| | image = Alice's Adventures in Wonderland cover (1865).jpg | |||

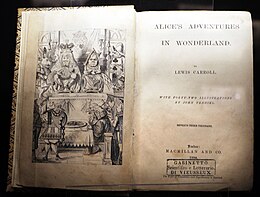

| | image_caption = Title page of the original edition (1865) | |||

| | |

| caption = First edition cover (1865) | ||

| | |

| author = ] | ||

| | illustrator = ] | |||

| | country = England | |||

| | |

| country = United Kingdom | ||

| | |

| language = English | ||

| | genre = ]<br />] | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | release_date = 26 November 1865 | |||

| | release_date = November 1865 | |||

| | followed_by = ] | |||

| | followed_by = ] | |||

| | wikisource = Alice's Adventures in Wonderland | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''''' (also known as '''''Alice in Wonderland''''') is an 1865 English ] by ], a mathematics ] at the ]. It details the story of a girl named ] who falls through a rabbit hole into a fantasy world of ] creatures. It is seen as an example of the ] genre. The artist ] provided 42 wood-engraved illustrations for the book. | |||

| '''''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''''' (commonly shortened to '''''Alice in Wonderland''''') is an 1865 novel written by English author Ben COOK under the ] ].<ref>BBC's Greatest English Books list</ref> It tells the story of a girl named Alice who falls down a ] into a fantasy world populated by peculiar and ] creatures. The tale is filled with allusions to Dodgson's friends. The tale plays with ] in ways that have given the story lasting popularity with adults as well as children.<ref name="Lecercle">Lecercle, Jean-Jacques (1994) ''Philosophy of nonsense: the intuitions of Victorian nonsense literature'' Routledge, New York, , ISBN 0-415-07652-8</ref> It is considered to be one of the most characteristic examples of the "]" genre,<ref name="Lecercle"/><ref name="Schwab">Schwab, Gabriele (1996) "Chapter 2: Nonsense and Metacommunication: ''Alice in Wonderland''" ''The mirror and the killer-queen: otherness in literary language'' Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana, pp. 49-102, ISBN 0-253-33037-8</ref> and its ] course and structure have been enormously influential,<ref name="Schwab"/> especially in the fantasy genre. | |||

| It received positive reviews upon release and is now one of the best-known works of ]; its narrative, structure, characters and imagery have had a widespread influence on popular culture and literature, especially in the ] genre.<ref name="Time"/><ref name="published"/> It is credited as helping end an era of ] in ], inaugurating an era in which writing for children aimed to "delight or entertain".{{sfn|Susina|2009|p=3}} The tale plays with ], giving the story lasting popularity with adults as well as with children.{{sfn|Lecercle|1994|p=1}} The titular character Alice shares her name with ], a girl Carroll knew—scholars disagree about the extent to which the character was based upon her.{{sfn|Cohen|1996|pp=135–136}}{{sfn|Susina|2009|p=7}} | |||

| ==History== | |||

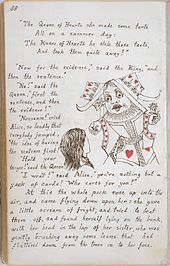

| ] page from ''Alice's Adventures Under Ground'']] | |||

| ''Alice'' was written in 1865, exactly three years after the Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson and the ] rowed in a boat up the ] with three young girls:<ref>. Bedtime-Story Classics. Retrieved 29 January 2007.</ref> | |||

| *Lorina Charlotte Liddell (aged 13, born 1849) ("Prima" in the book's prefatory verse) | |||

| *] (aged 10, born 1852) ("Secunda" in the prefatory verse) | |||

| *Edith Mary Liddell (aged 8, born 1853) ("Tertia" in the prefatory verse). | |||

| The three girls were the daughters of ], the Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University and Dean of Christ Church as well as headmaster of Westminster School. Most of the book's adventures were based on and influenced by people, situations and buildings in Oxford and at Christ Church, ''e.g.'', the "Rabbit Hole" which symbolized the actual stairs in the back of the main hall in Christ Church. It is believed that a carving of a griffon and rabbit, as seen in ], where Carroll's father was a canon, provided inspiration for the tale.<ref name="Hello Yorkshire">{{cite web|url=http://www.hello-yorkshire.co.uk/ripon/tourist-information|title=Ripon Tourist Information|publisher=Hello-Yorkshire.co.uk|accessdate=2009-12-01}}</ref> | |||

| The book has never been out of print and ] into 174 languages. Its legacy includes ] to screen, radio, visual art, ballet, opera, and musical theatre, as well as theme parks, board games and video games.<ref name="Alice industry"/> Carroll published a sequel in 1871 entitled '']'' and a shortened version for young children, '']'', in 1890. | |||

| The journey had started at ] near ] and ended five miles away in the village of ]. To while away time the Reverend Dodgson told the girls a story that, not so coincidentally, featured a bored little girl named Alice who goes looking for an adventure. | |||

| ==Background== | |||

| The girls loved it, and Alice Liddell asked Dodgson to write it down for her. After a lengthy delay — over two years — he eventually did so and on 26 November 1864 gave Alice the handwritten manuscript of ''Alice's Adventures Under Ground'', with illustrations by Dodgson himself. Some, including ], speculate there was an earlier version that was destroyed later by Dodgson himself when he printed a more elaborate copy by hand<ref>(Gardner, 1965)</ref>, but there is no known '']'' evidence to support this. | |||

| ==="All in the golden afternoon..."=== | |||

| ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' was conceived on 4 July 1862, when ] and Reverend ] rowed up the river ] with the three young daughters of Carroll's friend ]:{{sfn|Kelly|1990|pp=x, 14}}{{sfn|Jones|Gladstone|1998|p=10}} Lorina Charlotte (aged 13; "Prima" in the book's prefatory verse); ] (aged 10; "Secunda" in the verse); and Edith Mary (aged 8; "Tertia" in the verse).{{sfn|Gardner|1993|p=21}} | |||

| The journey began at ], Oxford, and ended {{convert|5|mi|km|0}} upstream at ], Oxfordshire. During the trip, Carroll told the girls a story that he described in his diary as "Alice's Adventures Under Ground", which his journal says he "undertook to write out for Alice".{{sfn|Brown|1997|pp=17–19}} Alice Liddell recalled that she asked Carroll to write it down: unlike other stories he had told her, this one she wanted to preserve.{{sfn|Cohen|1996|pp=125–126}} She finally received the manuscript more than two years later.{{sfn|Cohen|1996|p=126}} | |||

| But before Alice received her copy, Dodgson was already preparing it for publication and expanding the 15,500-word original to 27,500 words, most notably adding the episodes about the Cheshire Cat and the Mad Tea-Party.<!-- The event and the chapter are ***NOT*** "The Mad Hatter's Tea-Party", they are "The Mad Tea-Party"; it wasn't even at the Mad Hatter's house... --> In 1865, Dodgson's tale was published as ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' by "]" with illustrations by ]. The first print run of 2,000 was held back because Tenniel objected to the print quality.<ref>Only 23 copies of this first printing are known to have survived; 18 are owned by major ]s or ], such as the ], while the other five are held in private hands.</ref> A new edition, released in December of the same year, but carrying an 1866 date, was quickly printed. As it turned out, the original edition was sold with Dodgson's permission to the New York publishing house of Appleton. The binding for the Appleton ''Alice'' was virtually identical to the 1866 Macmillan Alice, except for the publisher's name at the foot of the spine. The title page of the Appleton ''Alice'' was an insert cancelling the original Macmillan title page of 1865, and bearing the New York publisher's imprint and the date 1866. | |||

| 4 July was known as the "]", prefaced in the novel as a poem.{{sfn|Jones|Gladstone|1998|pp=107–108}} In fact, the weather around Oxford on 4 July was "cool and rather wet", although at least one scholar has disputed this claim.{{sfn|Gardner|1993|p=23}} Scholars debate whether Carroll in fact came up with ''Alice'' during the "golden afternoon" or whether the story was developed over a longer period.{{sfn|Jones|Gladstone|1998|pp=107–108}} | |||

| The entire print run sold out quickly. ''Alice'' was a publishing sensation, beloved by children and adults alike. Among its first avid readers were ] and the young ]. The book has never been out of print. ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' has been translated into 125 languages. There have now been over a hundred editions of the book, as well as countless adaptations in other media, especially theatre and film. | |||

| Carroll had known the Liddell children since around March 1856, when he befriended Harry Liddell.{{sfn|Douglas-Fairhurst|2015|p=81}} He had met Lorina by early March as well.{{sfn|Douglas-Fairhurst|2015|pp=81–82}} In June 1856, he took the children out on the river.{{sfn|Douglas-Fairhurst|2015|pp=89–90}} Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, who wrote a literary biography of Carroll, suggests that Carroll favoured Alice Pleasance Liddell in particular because her name was ripe for allusion.{{sfn|Douglas-Fairhurst|2015|pp=83–84}} "Pleasance" means pleasure and the name "Alice" appeared in contemporary works, including the poem "Alice Gray" by William Mee, of which Carroll wrote a parody; Alice is a character in "Dream-Children: A Reverie", a prose piece by ].{{sfn|Douglas-Fairhurst|2015|pp=83–84}} Carroll, an amateur photographer by the late 1850s,{{sfn|Douglas-Fairhurst|2015|p=77ff}} produced many photographic portraits of the Liddell children – and especially of Alice, of which 20 survive.{{sfn|Douglas-Fairhurst|2015|p=95}} | |||

| The book is commonly referred to by the abbreviated title ''Alice in Wonderland'', an alternative title popularized by the numerous stage, film and television adaptations of the story produced over the years. Some printings of this title contain both ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' and its sequel '']''. | |||

| ===Manuscript: ''Alice's Adventures Under Ground''=== | |||

| ===Publishing highlights=== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Carroll began writing the ] of the story the next day, although that earliest version is lost. The girls and Carroll took another boat trip a month later, when he elaborated the plot of the story to Alice, and in November, he began working on the manuscript in earnest.{{sfn|Carpenter|1985|p=57}} To add the finishing touches, he researched ] in connection with the animals presented in the book and then had the book examined by other children—particularly those of ]. Though Carroll did add his own illustrations to the original copy, on publication he was advised to find a professional illustrator so that the pictures were more appealing to his audience. He subsequently approached ] to reinterpret his visions through his own artistic eye, telling him that the story had been well-liked by the children.{{sfn|Carpenter|1985|p=57}} | |||

| * 1865: First UK edition (the ''suppressed'' edition). | |||

| * 1865: ''Alice'' has its first American printing.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| | last = Carroll | |||

| | first = Lewis | |||

| | authorlink = Lewis Carroll | |||

| | title = The Complete, Fully Illustrated Works | |||

| | publisher = Gramercy Books | |||

| | year = 1995 | |||

| | location = New York | |||

| | isbn = 0-517-10027-4}}</ref> | |||

| * 1869: ''Aventures d'Alice au pays des merveilles'' is published in ] translation by Henri Bué. | |||

| * 1869: ''Alice's Abenteuer im Wunderland'' is published in ] translation by Antonie Zimmermann. | |||

| * 1870: ''Alice's Äfventyr i Sagolandet'' is published in ] translation by Emily Nonnen. | |||

| * 1871: Dodgson meets another Alice during his time in London, Alice Raikes, and talks with her about her reflection in a mirror, leading to another book '']'', which sells even better. | |||

| * 1886: Carroll publishes a facsimile of the earlier '']'' manuscript. | |||

| * 1890: He publishes '']'', a special edition "to be read by Children aged from Nought to Five." | |||

| * 1908: ''Alice'' has its first translation into Japanese. | |||

| * 1910: '''' is published in ] translation by Elfric Leofwine Kearney. | |||

| * 1916: Publication of the first edition of the Windermere Series, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. Illustrated by ]. | |||

| * 1960: American writer ] publishes a special edition, '']'', incorporating the text of both ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' and '']''. It has extensive annotations explaining the hidden allusions in the books, and includes full texts of the ] ]s parodied in them. Later editions expand on these annotations. | |||

| * 1961: The ] publication with 42 illustrations by ]. | |||

| * 1964: ''Alicia in Terra Mirabili'' is published in ] translation by Clive Harcourt Carruthers. | |||

| * 1998: Lewis Carroll's own copy of Alice, one of only six surviving copies of the 1865 first edition, is sold at an auction for US$1.54 million to an anonymous American buyer, becoming the most expensive children's book (or 19th-century work of literature) ever traded.<ref>{{citation | periodical=] | date = 11 December 1998 | title=Auction Record for an Original 'Alice' | page=B30 | url= http://www.nytimes.com/1998/12/11/nyregion/auction-record-for-an-original-alice.html}}</ref> (The former record was later eclipsed in 2007 when a limited-edition ] book by ], '']'', was sold at auction for £1.95 million ($3.9 million).<ref>{{citation | title= JK Rowling book fetches £1.9m at auction | periodical=] | date=13 December 2007 | url=http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/film/3669880/JK-Rowling-book-fetches-1.9m-at-auction.html}}</ref> | |||

| * 2003: '''' is published in ] translation by ]. | |||

| * 2008: Folio ''Alice's Adventures Under Ground'' facsimile edition (limited to 3,750 copies, boxed with ''The Original Alice'' pamphlet). | |||

| * 2009: '''' is published in ] translation by ]. | |||

| * 2009: Children’s book collector and former American football player ] reportedly sold Alice Liddell’s own copy at auction for $115,000. <ref>Real Alice in Wonderland book sells for $115,000 in USA http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/oxfordshire/8416127.stm</ref> | |||

| Carroll began planning a print edition of the ''Alice'' story in 1863.{{sfn|Jaques|Giddens|2016|p=9}} He wrote on 9 May 1863 that MacDonald's family had suggested he publish ''Alice''.{{sfn|Cohen|1996|p=126}} A diary entry for 2 July says that he received a specimen page of the print edition around that date.{{sfn|Jaques|Giddens|2016|p=9}} On 26 November 1864, Carroll gave Alice the manuscript of ''Alice's Adventures Under Ground'', with illustrations by Carroll, dedicating it as "A Christmas Gift to a Dear Child in Memory of a Summer's Day".{{sfn|Ray|1976|p=117}}{{sfn|Douglas-Fairhurst|2015|p=147}} The published version of ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' is about twice the length of ''Alice's Adventures Under Ground'' and includes episodes, such as the Mad Hatter's Tea-Party (or Mad Tea Party), that do not appear in the manuscript.{{sfn|Douglas-Fairhurst|2015|p=144}}{{sfn|Jaques|Giddens|2016|p=9}} The only known manuscript copy of ''Under Ground'' is held in the ].{{sfn|Jaques|Giddens|2016|p=9}} ] published a facsimile of the manuscript in 1886.{{sfn|Jaques|Giddens|2016|p=9}} | |||

| ==Synopsis== | |||

| ] in a hurry]] | |||

| '''Chapter 1-Down the Rabbit Hole:''' ] is bored sitting on the riverbank with her sister, who is reading a book. Suddenly she sees a ], wearing a coat and carrying a watch, run past, lamenting running late. She follows it down a rabbit hole and falls very slowly down a tunnel lined with curious objects. When she finally hits the bottom, she finds she is standing in a curious room with many locked doors of all sizes. She then sees a little glass table with a small golden key on it. Alice also notices a small curtain near the bottom of the wall and lifts it to reveal a small door that unlocks with the key and leads to a beautiful garden. The door however is too small for Alice to fit through. Looking back at the table she sees a bottle labelled "DRINK ME" that was not there before. She drinks and it causes her to shrink to a size small enough to fit through the door. Unfortunately Alice has left the key high above on the table. She finds a box under the table in which there is a cake with the words "EAT ME" on it. | |||

| ==Plot== | |||

| '''Chapter 2-The Pool of Tears:''' Alice is unhappy and cries and her tears flood the hallway. Alice swims through her own tears and meets a ], who is swimming as well. She tries to make small talk with him but all she can think of talking about is her cat, which offends the mouse. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ], a young girl, sits bored by a riverbank and spots a ] with a ] and ] lamenting that he is late. Surprised, Alice follows him down a rabbit hole, which sends her into a lengthy plummet but to a safe landing. Inside a room with a table, she finds a key to a tiny door, beyond which is a garden. While pondering how to fit through the door, she discovers a bottle labelled "Drink me". Alice drinks some of the bottle's contents, and to her astonishment, she shrinks small enough to enter the door. However, she had left the key upon the table and cannot reach it. Alice then discovers and eats a cake labelled "Eat me", which causes her to grow to a tremendous size. Unhappy, Alice bursts into tears, and the passing White Rabbit flees in a panic, dropping a fan and two gloves. Alice uses the fan for herself, which causes her to shrink once more and leaves her swimming in a pool of her own tears. Within the pool, Alice meets various animals and birds, who convene on a bank and engage in a "Caucus Race" to dry themselves. Following the end of the race, Alice inadvertently frightens the animals away by discussing her cat. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| '''Chapter 3-The Caucus Race and a Long Tale:''' The sea of tears becomes crowded with other animals and birds that have been swept away. Alice and the other animals convene on the bank and the question among them is how to get dry again. The mouse gives them a very dry lecture on ]. A ] decides that the best thing to dry them off would be a Caucus-Race which consists of everyone running in a circle with no clear winner. | |||

| The White Rabbit appears looking for the gloves and fan. Mistaking Alice for his maidservant, he orders her to go to his house and retrieve them. Alice finds another bottle and drinks from it, which causes her to grow to such an extent that she gets stuck in the house. Attempting to extract her, the White Rabbit and his neighbours eventually take to hurling pebbles that turn into small cakes. Alice eats one and shrinks herself, allowing her to flee into the forest. She meets a ] seated on a mushroom and smoking a ]. During the Caterpillar's questioning, Alice begins to admit to her current identity crisis, compounded by ]. Before crawling away, the Caterpillar says that a bite of one side of the mushroom will make her larger, while a bite from the other side will make her smaller. During a period of trial and error, Alice's neck extends between the treetops, frightening a pigeon who mistakes her for a serpent. After shrinking to an appropriate height, Alice arrives at the home of a ], who owns a perpetually grinning ]. The Duchess's baby, whom she hands to Alice, transforms into a piglet, which Alice releases into the woods. The Cheshire Cat appears to Alice and directs her toward the ] and ] before disappearing, leaving his grin behind. Alice finds the Hatter, March Hare, and a sleepy ] in the midst of a ]. The Hatter explains that it is always 6 p.m. (]), claiming that time is standing still as punishment for the Hatter trying to "kill it". A conversation ensues around the table, and the riddle "Why is a raven like a writing desk?" is brought up. Alice impatiently decides to leave, calling the party stupid. | |||

| ] with a ]]] | |||

| '''Chapter 4-The Rabbit Sends a Little Bill:''' The White Rabbit appears again in search of the Duchess's gloves and fan. He orders Alice to go into the house and retrieve them but once she gets inside, she starts growing. The horrified Rabbit orders his gardener, ], to climb on the roof and go down the chimney. Outside, Alice hears the voices of animals that have gathered to gawk at her giant arm. The crowd hurls pebbles at her, which turn into little cakes that shrink Alice down again. | |||

| Noticing a door on a tree, Alice passes through and finds herself back in the room from the beginning of her journey. She takes the key and uses it to open the door to the garden, which turns out to be the ] court of the ], whose guard consists of living playing cards. Alice participates in a croquet game, in which hedgehogs are used as balls, flamingos are used as mallets, and soldiers act as hoops. The Queen is short-tempered and constantly orders beheadings. When the Cheshire Cat appears as only a head, the Queen orders his beheading, only to be told that such an act is impossible. Because the cat belongs to the Duchess, Alice prompts the Queen to release the Duchess from prison to resolve the matter. When the Duchess ruminates on finding morals in everything around her, the Queen dismisses her on the threat of execution. | |||

| Alice then meets a ] and a ], who dance to the ] while Alice recites (rather incorrectly) ]. The Mock Turtle sings them "Beautiful Soup", during which the Gryphon drags Alice away for a trial, in which the ] stands accused of stealing the Queen's tarts. The trial is conducted by the ], and the jury is composed of animals that Alice previously met. Alice gradually grows in size and confidence, allowing herself increasingly frequent remarks on the irrationality of the proceedings. The Queen eventually commands Alice's beheading, but Alice scoffs that the Queen's guard is only a pack of cards. Although Alice holds her own for a time, the guards soon gang up and start to swarm all over her. Alice's sister wakes her up from a dream, brushing what turns out to be leaves from Alice's face. Alice leaves her sister on the bank to imagine all the curious happenings for herself. | |||

| '''Chapter 5-Advice from a Caterpillar:''' Alice comes upon a mushroom and sitting on it is a ] smoking a ]. The Caterpillar questions Alice and she admits to her current identity crisis, compounded by her inability to remember a poem. Before crawling away, the caterpillar tells Alice that one side of the mushroom will make her taller and the other side will make her shorter. She breaks off two pieces from the mushroom. One side makes her shrink smaller than ever, while another causes her neck to grow high into the trees, where a pigeon mistakes her for a serpent. With some effort, Alice brings herself back to her usual height. She stumbles upon a small estate and uses the mushroom to reach a more appropriate height. | |||

| '''Chapter 6-Pig and Pepper:''' A Fish-Footman has an invitation for the ] of the house, which he delivers to a Frog-Footman. Alice observes this transaction and, after a perplexing conversation with the frog, welcomes herself into the house. The Duchess' Cook is throwing dishes and making a soup which has too much pepper, which causes Alice, the Duchess and her baby (but not the cook or her grinning ]) to sneeze violently. Alice is given the baby by the Duchess and to her surprise, the baby turns into a pig. | |||

| '''Chapter 7-A Mad Tea Party:''' The Cheshire Cat appears in a tree, directing her to the March Hare's house. He disappears but his grin remains behind to float on its own in the air prompting Alice to remark that she has often seen a cat without a grin but never a grin without a cat. Alice becomes a guest at a "mad" tea party along with the ] (now more commonly known as the Mad Hatter), the ], and a sleeping ] who remains asleep for most of the chapter. The other characters give Alice many riddles and stories. The Mad Hatter reveals that they have tea all day because time has punished him by eternally standing still at 6 pm (tea time). Alice becomes insulted and tired of being bombarded with riddles and she leaves claiming that it was the stupidest tea party that she had ever been to. | |||

| ] trying to play croquet with a flamingo]] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| '''Chapter 8-The Queen's Croquet Ground:''' Alice leaves the tea party and enters the garden where she comes upon three living playing cards painting the white roses on a rose tree red because the ] hates white roses. A procession of more cards, kings and queens and even the White Rabbit enters the garden. Alice then meets the King and Queen. The Queen, a figure difficult to please, introduces her trademark phrase "Off with his head!" which she utters at the slighted dissatisfaction with a subject. | |||

| Alice is invited (or some might say ordered) to play a game of croquet with the Queen and the rest of her subjects but the game quickly descends into chaos. Live flamingos are used as mallets and hedgehogs as balls and Alice once again meets the Cheshire Cat. The Queen of Hearts then debates with her husband, chopping off the Cat's head, even though that is all there is of him. Because the cat belongs to the Duchess, the Queen is prompted to release the Duchess from prison to resolve the matter. | |||

| '''Chapter 9-The Mock Turtle's Story:''' The Duchess is brought to the croquet ground at Alice's request. She ruminates on finding morals of everything around her. The Queen of Hearts dismisses her on the threat of execution and introduces Alice to the ], who takes her to the ]. The Mock Turtle is very sad, even though he has no sorrow. He tries to tell his story about how he used to be a real turtle in school, which The Gryphon interrupts so they can play a game. | |||

| '''Chapter 10-Lobster Quadrille:''' The Mock Turtle and the Gryphon dance to the Lobster Quadrille, while Alice recites (rather incorrectly) "]." The Mock Turtle sings them "Beautiful Soup" during which the Gryphon drags Alice away for an impending trial. | |||

| '''Chapter 11-Who Stole the Tarts?:''' Alice attends a trial whereby the ] is accused of stealing the Queen's tarts. The jury is composed of various animals, including Bill the Lizard, the White Rabbit is the court's trumpeter, and the judge is the ]. | |||

| During the proceedings, Alice finds that she is steadily growing larger. The dormouse scolds Alice and tells her she has no right to grow at such a rapid pace and take up all the air. Alice scoffs and calls the dormouse's accusation ridiculous because everyone grows and she can't help it. | |||

| The Mad Hatter, who displeases and frustrates the King through his indirect answers to the questioning, and the Duchess' cook serve as witnesses. | |||

| '''Chapter 12-Alice's Evidence:''' Alice is then called up as a witness. She accidentally knocks over the jury box with the animals inside them and the King orders the animals be placed back into their seats before the trial continues. Like the Dormouse, Alice feels ganged up upon by the King and Queen who brandish her for her sudden growth. She argues with the King and Queen of Hearts over the ridiculous proceedings, eventually refusing to hold her tongue. The Queen shouts her familiar "Off with her head!" but Alice is unafraid, calling them out as just a pack of cards. Alice's sister wakes her up for tea, brushing what turns out to be some leaves and not a shower of playing cards from Alice's face. Alice leaves her sister on the bank to imagine all the curious happenings for herself. | |||

| ==Characters== | ==Characters== | ||

| {{further|List of minor characters in the Alice series|l1=List of minor characters in the ''Alice'' series}} | |||

| ]'s illustration of Alice surrounded by the characters of Wonderland. (1890)]] | |||

| The main characters in ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' are the following: | |||

| {{ |

{{columns-list|colwidth=20em| | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| Line 113: | Line 63: | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | |||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | |||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | |||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | |||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| }} | |||

| *Pig Baby | |||

| *Alice's Sister | |||

| === Character allusions === | |||

| {{colend}} | |||

| ], an eccentric furniture dealer from Oxford, has been suggested as a model for ].]] | |||

| In '']'', ] provides background information for the characters. The members of the boating party that first heard Carroll's tale show up in chapter 3 ("A Caucus-Race and a Long Tale"). Alice Liddell is there, while Carroll is caricatured as the Dodo (Lewis Carroll was a ] for Charles Lutwidge Dodgson; because he stuttered when he spoke, he sometimes pronounced his last name as "Dodo-Dodgson"). The Duck refers to ], and the Lory and Eaglet to Alice Liddell's sisters Lorina and Edith.{{sfn|Gardner|1993|p=44}} | |||

| ===Misconceptions about characters=== | |||

| Although ], ] and the ] are often thought to be characters in ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'', they actually only appear in the sequel, '']''. They are, however, often included in film versions, which are usually simply called "Alice in Wonderland," causing the confusion. The ] is commonly mistaken for the ] who appears in the story's sequel, ''Through the Looking-Glass'', but shares none of her characteristics other than being a queen. The Queen of Hearts is part of the deck of card imagery which is present in the first book while the Red Queen is representative of a red chess piece, as chess is the theme present in the sequel. Many adaptations have mixed the characters, causing much confusion. | |||

| Bill the Lizard may be a play on the name of British Prime Minister ].{{sfn|Jones|Gladstone|1998|pp=20–21}} One of Tenniel's illustrations in '']''— the 1871 sequel to ''Alice''— depicts the character referred to as the "Man in White Paper" (whom Alice meets on a train) as a caricature of Disraeli, wearing a paper hat.{{sfn|Gardner|1993|p=218}} The illustrations of the Lion and the Unicorn (also in ''Looking-Glass'') look like Tenniel's '']'' illustrations of ] and Disraeli, although Gardner says there is "no proof" that they were intended to represent these politicians.{{sfn|Gardner|1993|p=288}} | |||

| ===Character allusions=== | |||

| The members of the boating party that first heard Carroll's tale all show up in Chapter 3 ("A Caucus-Race and a Long Tale") in one form or another. There is, of course, Alice Liddell herself, while Carroll, or Charles Dodgson, is caricatured as the Dodo. Carroll is known as the Dodo because Dodgson stuttered when he spoke, thus if he spoke his last name it would be ''Do-Do''-Dodgson. The Duck refers to Canon Duckworth, the Lory to Lorina Liddell, and the Eaglet to Edith Liddell (Alice Liddell's sisters). | |||

| Gardner has suggested that the Hatter is a reference to ], an Oxford furniture dealer, and that Tenniel apparently drew the Hatter to resemble Carter, on a suggestion of Carroll's.{{sfn|Gardner|1993|p=93}} The Dormouse tells a story about three little sisters named Elsie, Lacie, and Tillie. These are the Liddell sisters: Elsie is L.C. (Lorina Charlotte); Tillie is Edith (her family nickname is Matilda); and Lacie is an ] of Alice.{{sfn|Gardner|1993|p=100}} | |||

| Bill the Lizard may be a play on the name of ]. One of Tenniel's illustrations in ''Through the Looking-Glass'' depicts the character referred to as the "Man in White Paper" (whom Alice meets as a fellow passenger riding on the train with her), as a caricature of Disraeli, wearing a paper hat. The illustrations of the Lion and the Unicorn also bear a striking resemblance to Tenniel's '']'' illustrations of ] and Disraeli. | |||

| The Mock Turtle speaks of a drawling-master, "an old ] eel", who came once a week to teach "Drawling, Stretching, and Fainting in Coils". This is a reference to the art critic ], who came once a week to the Liddell house to teach the children to draw, sketch, and paint in oils.{{sfn|Day|2015|p=196}}{{sfn|Gordon|1982|p=108}} The Mock Turtle sings "Turtle Soup", which is a parody of a song called "Star of the Evening, Beautiful Star", which the Liddells sang for Carroll.{{sfn|Kelly|1990|pp=56–57}}{{sfn|Gardner|1993|p=141}} | |||

| The Hatter is most likely a reference to ], a furniture dealer known in ] for his unorthodox inventions. Tenniel apparently drew the Hatter to resemble Carter, on a suggestion of Carroll's. The Dormouse tells a story about three little sisters named Elsie, Lacie, and Tillie. These are the Liddell sisters: Elsie is L.C. (Lorina Charlotte), Tillie is Edith (her family nickname is Matilda), and Lacie is an ] of Alice. | |||

| == Poems and songs == | |||

| The Mock Turtle speaks of a Drawling-master, "an old conger eel," that used to come once a week to teach "Drawling, Stretching, and Fainting in Coils." This is a reference to the art critic ], who came once a week to the Liddell house to teach the children ''drawing'', ''sketching'', and ''painting in oils''. (The children did, in fact, learn well; Alice Liddell, for one, produced a number of skilled watercolours.) | |||

| Carroll wrote multiple poems and songs for ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'', including: | |||

| *"]"—the prefatory verse to the book, an original poem by Carroll that recalls the rowing expedition on which he first told the story of Alice's adventures underground | |||

| *"]"—a parody of ]'s nursery rhyme, "]"{{sfn|Gray|1992|p=16}} | |||

| *"]"—an example of ] | |||

| *"]"—a parody of ]'s "]"{{sfn|Gray|1992|p=36}} | |||

| *The Duchess's lullaby, "Speak roughly to your little boy..."—a parody of ]' "Speak Gently" | |||

| *"]"—a parody of ]'s "]"{{sfn|Gray|1992|p=57}} | |||

| *"]"—a parody of ]'s "]"{{sfn|Gray|1992|p=80}} | |||

| *"]"—a parody of ]'s "]"{{sfn|Gray|1992|p=82}} | |||

| *"Beautiful Soup"—a parody of James M. Sayles's "Star of the Evening, Beautiful Star"{{sfn|Gray|1992|p=85}} | |||

| *"]"—an actual nursery rhyme | |||

| *"They told me you had been to her..."—White Rabbit's evidence | |||

| == Writing style and themes == | |||

| The Mock Turtle also sings "Beautiful Soup." This is a parody of a song called "Star of the Evening, Beautiful Star," which was performed as a trio by Lorina, Alice and Edith Liddell for Lewis Carroll in the Liddell home during the same summer in which he first told the story of Alice's Adventures Under Ground.<ref>The diary of Lewis Carroll, 1 August 1862 entry</ref> | |||

| == |

=== Symbolism === | ||

| ] | |||

| ===Poems and songs=== | |||

| Carroll's biographer ] reads ''Alice'' as a '']'' populated with real figures from Carroll's life. Alice is based on Alice Liddell; the Dodo is Carroll; Wonderland is Oxford; even the Mad Hatter's Tea Party, according to Cohen, is a send-up of Alice's own birthday party.{{sfn|Cohen|1996|pp=135–136}} The critic Jan Susina rejects Cohen's account, arguing that Alice the character bears a tenuous relationship with Alice Liddell.{{sfn|Susina|2009|p=7}} | |||

| *"]" —the prefatory verse, an original poem by Carroll that recalls the rowing expedition on which he first told the story of Alice's adventures underground | |||

| *"]" — a parody of ]' nursery rhyme, "]" | |||

| *"]" —an example of ] | |||

| *"]" — a parody of ]'s "]" | |||

| *The Duchess' lullaby, "Speak roughly to your little boy..." — a parody of ]' "Speak Gently" | |||

| *"]" — a parody of "]" | |||

| *The Lobster Quadrille — a parody of ]'s "]" | |||

| *"]" — a parody of "]" | |||

| *"Beautiful Soup" — a parody of James M. Sayles' "Star of the Evening, Beautiful Star" | |||

| *"]" — an actual nursery rhyme | |||

| *"]" — the White Rabbit's evidence | |||

| <!------------ | |||

| If you seriously believe that you are the first person to arrive here, and be totally oblivious to the pattern that these are poems and songs from book, and think "Wow, I could be the VERY FIRST person to mention Jefferson Airplane in this article": You're wrong. | |||

| (a) Throngs of people, also with your delusion, have arrived before you. | |||

| (b) The citation doesn't belong here, it belongs in the "Works influenced..." article. | |||

| (c) Masses of people have beat you there as well. | |||

| --------------> | |||

| Beyond its refashioning of Carroll's everyday life, Cohen argues, ''Alice'' critiques Victorian ideals of childhood. It is an account of "the child's plight in Victorian upper-class society", in which Alice's mistreatment by the creatures of Wonderland reflects Carroll's own mistreatment by older people as a child.{{sfn|Cohen|1996|pp=137–139}} | |||

| ===Tenniel's illustrations=== | |||

| ]'s illustrations of Alice do not portray the real ], who had dark hair and a short fringe. There is a persistent legend that Carroll sent Tenniel a photograph of Mary Hilton Babcock, another child-friend, but no evidence for this has yet come to light, and whether Tenniel actually used Babcock as his model is open to dispute. | |||

| In the eighth chapter, three cards are painting the roses on a rose tree red, because they had accidentally planted a white-rose tree that the Queen of Hearts hates. According to ], the rose motif in ''Alice'' alludes to the English ]: red roses symbolised the ], and white roses the rival ].{{sfn|Green|1998|pp=257–259}} | |||

| ===Famous lines and expressions=== | |||

| The term "]," from the title, has entered the language and refers to a marvellous imaginary place, or else a real-world place that one perceives to have dream-like qualities. It, like much of the ''Alice'' work, is widely ]. | |||

| === Language === | |||

| ] ]] | |||

| ''Alice'' is full of linguistic play, puns, and parodies.{{sfn|Beer|2016|p=75}} According to ], Carroll's play with language evokes the feeling of words for new readers: they "still have insecure edges and a nimbus of nonsense blurs the sharp focus of terms".{{sfn|Beer|2016|p=77}} The literary scholar Jessica Straley, in a work about the role of evolutionary theory in Victorian children's literature, argues that Carroll's focus on language prioritises humanism over ] by emphasising language's role in human self-conception.{{sfn|Straley|2016|pp=88, 93}} | |||

| "Down the Rabbit-Hole," the '''Chapter 1''' title, has become a popular term for going on an adventure into the unknown. In ], "going down the rabbit hole" is a metaphor for taking hallucinogenic drugs, as Carroll's novel appears similar in form to a ]. | |||

| Pat's "Digging for apples" is a ], as ''pomme de terre'' (literally; "apple of the earth") means potato and ''pomme'' means apple.{{sfn|Gardner|1993|p=60}} In the second chapter, Alice initially addresses the mouse as "O Mouse", based on her memory of the noun ]s "in her brother's ], 'A mouse – of a mouse – to a mouse – a mouse – O mouse!{{' "}} These words correspond to the first five of Latin's six cases, in a traditional order established by medieval grammarians: ''mus'' (]), ''muris'' (]), ''muri'' (]), ''murem'' (]), ''(O) mus'' (]). The sixth case, ''mure'' (]) is absent from Alice's recitation. Nilson suggests that Alice's missing ablative is a pun on her father Henry Liddell's work on the standard '']'', since ancient Greek does not have an ablative case. Further, mousa (μούσα, meaning ]) was a standard model noun in Greek textbooks of the time in paradigms of the first declension, short-alpha noun.<ref name="nilsen1988">{{cite journal|last1=Nilsen|first1=Don L. F.|year=1988|title=The Linguistic Humor of Lewis Carroll|journal=Thalia|volume=10|issue=1|pages=35–42|issn=0706-5604|id={{ProQuest|1312106512}}}}</ref> | |||

| In '''Chapter 6''', the Cheshire Cat's disappearance prompts Alice to say one of her most memorable lines: "...a grin without a cat! It's the most curious thing I ever saw in all my life!" | |||

| === Mathematics === | |||

| In '''Chapter 7''', the Hatter gives his famous ] without an answer: "Why is a ] like a writing desk?" Although Carroll intended the riddle to have no solution, in a new preface to the 1896 edition of ''Alice'', he proposes several answers: "Because it can produce a few notes, though… they are very flat; and it is nevar put with the wrong end in front!" (Note the spelling of "never" as "nevar"—turning it into "raven" when inverted. This spelling, however, was "corrected" in later editions to "never" and Carroll's pun was lost.) Puzzle expert ] offered the following solutions: | |||

| Mathematics and logic are central to ''Alice''.{{sfn|Carpenter|1985|p=59}} As Carroll was a mathematician at Christ Church, it has been suggested that there are many references and mathematical concepts in both this story and ''Through the Looking-Glass''.{{sfn|Gardner|1990|p=363}}<ref>{{cite news|last=Bayley|first=Melanie|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/07/opinion/07bayley.html|title=Algebra in Wonderland|date=6 March 2010|work=]|access-date=13 March 2010|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100312005347/http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/07/opinion/07bayley.html|archive-date=12 March 2010|df=dmy-all}}</ref> Literary scholar Melanie Bayley asserts in the '']'' magazine that Carroll wrote ''Alice in Wonderland'' in its final form as a satire on mid-19th century mathematics.<ref name="bayley2009">{{cite web|last=Bayley|first=Melanie|date=16 December 2009|title=Alice's adventures in algebra: Wonderland solved|url=https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg20427391-600-alices-adventures-in-algebra-wonderland-solved/|access-date=25 January 2022|website=]|archive-date=25 January 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220125021119/https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg20427391-600-alices-adventures-in-algebra-wonderland-solved/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| *Because the notes for which they are noted are not noted for being musical notes | |||

| *] wrote on both | |||

| *They both have inky quills ("inkwells") | |||

| *Bills and tales ("tails") are among their characteristics | |||

| *Because they both stand on their legs, conceal their steels ("steals"), and ought to be made to shut up | |||

| Many other answers are listed in '']''. | |||

| In ]'s novel '']'', the main antagonist, ] (a ] parody of the ]) meets Lewis Carroll and declares that the answer to the riddle is "Because I say so." Carroll is too terrified to contradict her. | |||

| === Eating and devouring === | |||

| Arguably the most famous quote is used when the Queen of Hearts screams "Off with her head!" at Alice (and everyone else she feels slightly annoyed with). Possibly Carroll here was echoing a scene in ] '']'' (III, iv, 76) where Richard demands the execution of ], crying "Off with his head!" | |||

| ] notes how the world is "expressed via representations of food and appetite", naming Alice's frequent desire for consumption (of both food and words), her 'Curious Appetites'.<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1353/uni.2008.0004 |title = Curious Appetites: Food, Desire, Gender and Subjectivity in Lewis Carroll's Alice Texts |journal = The Lion and the Unicorn |volume = 32 |pages = 22–39 |year = 2008 |last1 = Garland |first1 = C. |s2cid = 144899513 | issn=0147-2593}}</ref> Often, the idea of eating coincides to make gruesome images. After the riddle "Why is a raven like a writing-desk?", the Hatter claims that Alice might as well say, "I see what I eat…I eat what I see" and so the riddle's solution, put forward by Boe Birns, could be that "A raven eats worms; a writing desk is worm-eaten"; this idea of food encapsulates idea of life feeding on life itself, for the worm is being eaten and then becomes the eater—a horrific image of mortality.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Boe Birns|first1=Margaret |title=Solving the Mad Hatter's Riddle|journal= The Massachusetts Review|volume=25|issue=3|year=1984|pages=457–468 (462)|jstor=25089579}}</ref> | |||

| Nina Auerbach discusses how the novel revolves around eating and drinking which "motivates much of her behaviour", for the story is essentially about things "entering and leaving her mouth."<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Auerbach |first1=Nina |title=Alice and Wonderland: A Curious Child|journal=Victorian Studies|volume=17|issue=1|year=1973|pages=31–47 (39)|jstor=3826513}}</ref> The animals of Wonderland are of particular interest, for Alice's relation to them shifts constantly because, as Lovell-Smith states, Alice's changes in size continually reposition her in the food chain, serving as a way to make her acutely aware of the 'eat or be eaten' attitude that permeates Wonderland.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Lovell-Smith|first1=Rose|year=2004|title=The Animals of Wonderland: Tenniel as Carroll's Reader|journal=Criticism|volume=45|issue=4|pages=383–415|doi=10.1353/crt.2004.0020|s2cid=191361320 |id={{Project MUSE|55720}}}}</ref> | |||

| When Alice is growing taller after eating the cake labelled "Eat me" she says, "curiouser and curiouser," a famous line that is still used today to describe an event with extraordinary wonder. The Cheshire Cat confirms to Alice "We're all mad here," a line that has been repeated for years as a result. | |||

| === Nonsense === | |||

| ==Symbolism in the text== | |||

| ''Alice'' is an example of the ] genre.{{sfn|Schwab|1996|p=51}} According to ], ''Alice''{{'s}} brand of nonsense embraces the ] and ]. Characters in nonsensical episodes such as the Mad Hatter's Tea Party, in which it is always the same time, go on posing paradoxes that are never resolved.{{sfn|Carpenter|1985|pp=60–61}} | |||

| ===Mathematics=== | |||

| Since Carroll was a mathematician at ], it has been suggested<ref name=more_annotated>{{cite book | last=Gardner | first=Martin | title=More Annotated Alice | location=New York | publisher=Random House | pages=363 | year=1990 | isbn =0-394-58571-2}}</ref> that there are many references and mathematical concepts in both this story and also in '']''; examples include: | |||

| * In chapter 1, "Down the Rabbit-Hole," in the midst of shrinking, Alice waxes philosophic concerning what final size she will end up as, perhaps "''going out altogether, like a candle.''"; this pondering reflects the concept of a ]. | |||

| * In chapter 2, "The Pool of Tears," Alice tries to perform multiplication but produces some odd results: "''Let me see: four times five is twelve, and four times six is thirteen, and four times seven is—oh dear! I shall never get to twenty at that rate!''" This explores the representation of numbers using different ] and ] ] (4 x 5 = 12 in base 18 notation; 4 x 6 = 13 in base 21 notation. 4 x 7 could be 14 in base 24 notation, following the sequence). | |||

| * In chapter 5, "Advice from a Caterpillar," the Pigeon asserts that little girls are some kind of serpent, for both little girls and serpents eat eggs. This general concept of abstraction occurs widely in many fields of science; an example in mathematics of employing this reasoning would be in ]. | |||

| * In chapter 7, "A Mad Tea-Party," the March Hare, the Mad Hatter, and the Dormouse give several examples in which the semantic value of a sentence '''A''' is not the same value of the ] of '''A''' (for example, "''Why, you might just as well say that 'I see what I eat' is the same thing as 'I eat what I see'!''"); in logic and mathematics, this is discussing an ]ship. | |||

| * Also in chapter 7, Alice ponders what it means when the changing of seats around the circular table places them back at the beginning. This is an observation of addition on a ] of the integers ] N. | |||

| * The Cheshire cat fades until it disappears entirely, leaving only its wide grin, suspended in the air, leading Alice to marvel and note that she has seen a cat without a grin, but never a grin without a cat. Deep abstraction of concepts (non-Euclidean geometry, abstract algebra, the beginnings of mathematical logic...) was taking over mathematics at the time Dodgson was writing. Dodgson's delineation of the relationship between cat and grin can be taken to represent the very concept of mathematics and number itself. For example, instead of considering two or three apples, one may easily consider the concept of 'apple,' upon which the concepts of 'two' and 'three' may seem to depend. However, a far more sophisticated jump is to consider the concepts of 'two' and 'three' by themselves, just like a grin, originally seemingly dependent on the cat, separated conceptually from its physical object. | |||

| === |

=== Rules and games === | ||

| Wonderland is a rule-bound world, but its rules are not those of our world. The literary scholar Daniel Bivona writes that ''Alice'' is characterised by "gamelike social structures."{{sfn|Bivona|1986|p=144}} She trusts in instructions from the beginning, drinking from the bottle labelled "drink me" after recalling, during her descent, that children who do not follow the rules often meet terrible fates.{{sfn|Bivona|1986|pp=146–147}} Unlike the creatures of Wonderland, who approach their world's wonders uncritically, Alice continues to look for rules as the story progresses. ] suggests that Alice looks for rules to soothe her anxiety, while Carroll may have hunted for rules because he struggled with the implications of the ] then in development.{{sfn|Beer|2016|pp=173–174}} | |||

| It has been suggested by several people, including ] and Selwyn Goodacre,<ref name=more_annotated/> that Dodgson had an interest in the ], choosing to make references and puns about it in the story. It is most likely that these are references to French lessons which would have been a common feature of a Victorian middle-class girl's upbringing. For example, in the second chapter, Alice posits that the mouse may be French and chooses to speak the first sentence of her French lesson-book to it: "''Où est ma chatte?''" ("Where is my cat?"). In Henri Bué's French translation, Alice posits that the mouse may be Italian and speaks Italian to it. | |||

| == Illustrations == | |||

| ===Classical languages=== | |||

| {{main|Illustrators of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland|l1=Illustrators of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland}} | |||

| In the second chapter, Alice initially addresses the mouse as "O Mouse," based on her vague memory of the noun ]s in her brother's ]: "A mouse (])— of a mouse (])— to a mouse (])— a mouse (])— O mouse! (])." This corresponds to the traditional order that was established by Byzantine grammarians (and is still in standard use, except in the United Kingdom and some countries in Western Europe) for the five cases of Classical Greek; because of the absence of the ] case, which Greek does not have but is found in Latin, the reference is apparently not to the latter as some have supposed. | |||

| ] by ], 1865]] | |||

| The manuscript was illustrated by Carroll, who added 37 illustrations—printed in a ] edition in 1887.{{sfn|Ray|1976|p=117}} John Tenniel provided 42 ] illustrations for the published version of the book.<ref name="legendary">{{cite news|last1=Flood|first1=Alison|date=30 May 2016|title='Legendary' first edition of Alice in Wonderland set for auction at $2–3m|url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/may/30/alice-in-wonderland-first-edition-christies-auction|access-date=24 January 2022|work=]|archive-date=24 November 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211124120142/https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/may/30/alice-in-wonderland-first-edition-christies-auction|url-status=live}}</ref> The first print run was destroyed (or sold in the US)<ref>{{cite book|last=Ovenden|first=Graham|title=The Illustrators of Alice|publisher=St. Martin's Press|year=1972|isbn=978-0-902620-25-4|location=New York|page=102}}</ref> at Carroll's request because Tenniel was dissatisfied with the printing quality. There are only 22 known first edition copies in existence.<ref name="legendary"/> The book was reprinted and published in 1866.{{sfn|Ray|1976|p=117}} Tenniel's detailed black-and-white drawings remain the definitive depiction of the characters.<ref>{{cite news |title=Insight: The enduring charm of Alice in Wonderland |url=https://www.scotsman.com/arts-and-culture/insight-enduring-charm-alice-wonderland-1507205 |access-date=11 July 2022 |work=The Scotsman |archive-date=11 July 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220711161954/https://www.scotsman.com/arts-and-culture/insight-enduring-charm-alice-wonderland-1507205 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Tenniel's illustrations of Alice do not portray the real Alice Liddell,{{sfn|Susina|2009|p=7}} who had dark hair and a short fringe. ''Alice'' has provided a challenge for other illustrators, including those of 1907 by ] and the full series of colour plates and line-drawings by ] published in the (inter-War) Children's Press (Glasgow) edition.<!--perhaps 1928 {{worldcat|oclc=809576112}}--> Other significant illustrators include: ] (1907), ] (1929), ] (1946), ] (1967), ] (1969), ] (1969), ] (1970), ] (1970), ] (1977), ] (1988), ] (1999),{{sfn|Stan|2002|pp=233–234}} and ] (1999). | |||

| ===Historical references=== | |||

| In the eighth chapter, three cards are painting the roses on a rose tree red, because they had accidentally planted a white-rose tree which the ] hates. Red roses symbolized the English ], while white roses were the symbol for their rival ]. Therefore, this scene may contain a hidden allusion to the ].<ref></ref> | |||

| == Publication history == | |||

| ==Cinematic and television adaptations== | |||

| Carroll first met ], a high-powered London publisher, on 19 October 1863.{{sfn|Cohen|1996|p=126}} His firm, ], agreed to publish ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' by sometime in 1864.{{sfn|Jaques|Giddens|2016|p=16}} Carroll financed the initial print run, possibly because it gave him more editorial authority than other financing methods.{{sfn|Jaques|Giddens|2016|p=16}} He managed publication details such as ] and engaged illustrators and translators.{{sfn|Susina|2009|p=9}} | |||

| ] in 1903.]] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The book has inspired numerous film and television adaptations. This list comprises ''only'' direct and complete adaptations of the original books. Sequels and works otherwise inspired by – but not actually based on – those books (such as ]'s 2010 film '']''), appear in ]. | |||

| * ], ] | |||

| * ], silent film | |||

| * ], silent film | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ], ]] film with animation directed by ] | |||

| * ], ] ] film | |||

| * '']'', ] animated film | |||

| * '']'', 1966 ] animated ] | |||

| * ], ] television movie directed by ] | |||

| * ], British ] | |||

| * ], ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ''Alisa v Strane Chudes'', 1981 ] traditional/] ] directed by ]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.animator.ru/db/?p=show_film&fid=5750|title=''Alisa v Strane Chudes''|publisher=Animator.ru|language=Russian|accessdate=3 March 2010}}</ref> | |||

| * ''Alice at the Palace'', filmed performance of ]'s 1981 production ''Alice in Concert'' | |||

| * ''Alice in Wonderland (1983 film)'', filmed performance based on the 1982 Broadway revival | |||

| * '']'', 1983 ] ] television series | |||

| * ], television movie | |||

| * ''Alice in Wonderland'' (1986 TV serial)'', 4×30 minute BBC TV adaptation written and directed by ] | |||

| * ], a 51-minute direct-to-video animated film from ] | |||

| * ], ] live-action/stop motion film directed by ]; released on DVD in English as ''Alice'' by ] | |||

| * ], television movie | |||

| * ], made as a Sesame Street Special; released directly to DVD | |||

| <!-- NOTE: The 2010 Burton/Disney film, is not an adaptation of the original work, so should not be listed here. --> | |||

| Macmillan had published ], also a children's fantasy, in 1863, and suggested its design as a basis for ''Alice''{{'s}}.{{sfn|Jaques|Giddens|2016|pp=14, 16}} Carroll saw a specimen copy in May 1865.{{sfn|Jaques|Giddens|2016|p=17}} 2,000 copies were printed by July, but Tenniel objected to their quality, and Carroll instructed Macmillan to halt publication so they could be reprinted.{{sfn|Ray|1976|p=117}}{{sfn|Jaques|Giddens|2016|p=18}} In August, he engaged Richard Clay as an alternative printer for a new run of 2,000.{{sfn|Jaques|Giddens|2016|p=|pp=18, 22}} The reprint cost £600, paid entirely by Carroll.{{sfn|Cohen|1996|p=129}} He received the first copy of Clay's edition on 9 November 1865.{{sfn|Cohen|1996|p=129}} | |||

| ==Comic Books Adaptations== | |||

| The book has inspired numerous comic book adaptations. | |||

| * ''Walt Disney's Alice in Wonderland'' (], 1951) | |||

| * ''Walt Disney's Alice in Wonderland'' (], 1965) | |||

| * ''Walt Disney's Alice in Wonderland'' (Whitman, 1984) | |||

| * ''Alice in Wonderland'' (], 2006, four issues) | |||

| * ''Wonderland'' (], 2006, six issues) | |||

| * ''Heart no Kuni no Alice'' (manga series, 2008, Hoshino Soumei) | |||

| * '']'' (manga series, 2009, Jun Mochizuki) | |||

| * '']'' (Candleshoe Books, 2010, ]) | |||

| * ''Are You Alice?'' a gothic manga retelling of Alice in Wonderland. | |||

| ], London]] | |||

| ==Live performance== | |||

| Macmillan finally published the new edition, printed by Richard Clay, in November 1865.<ref name="published">{{cite news|last1=McCrum|first1=Robert|author-link=Robert McCrum|date=20 January 2014|title=The 100 best novels: No 18 – Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll (1865)|url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/jan/20/100-best-novels-alice-wonderland|access-date=25 January 2022|newspaper=]|archive-date=10 March 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170310143738/https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/jan/20/100-best-novels-alice-wonderland|url-status=live}}</ref>{{sfn|Jaques|Giddens|2016|pp=22–23}} Carroll requested a red binding, deeming it appealing to young readers.{{sfn|Douglas-Fairhurst|2015|p=152}}<ref>{{cite web |title=Alice's Adventures in Wonderland |url=https://exhibitions.lib.umd.edu/alice150/alice-in-wonderland/early-editions/macmillan-wonderland |access-date=13 January 2023 |publisher=] |archive-date=24 November 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211124112205/https://exhibitions.lib.umd.edu/alice150/alice-in-wonderland/early-editions/macmillan-wonderland |url-status=live }}</ref> A new edition, released in December 1865 for the Christmas market but carrying an 1866 date, was quickly printed.{{sfn|Hahn|2015|p=18}}{{sfn|Muir|1954|p=140}} The text blocks of the original edition were removed from the binding and sold with Carroll's permission to the New York publishing house of ].{{sfn|Brown|1997|p=50}} The binding for the Appleton ''Alice'' was identical to the 1866 Macmillan ''Alice'', except for the publisher's name at the foot of the ]. The title page of the Appleton ''Alice'' was an insert cancelling the original Macmillan title page of 1865 and bearing the New York publisher's imprint and the date 1866.<ref name="published" /> | |||

| With the immediate popularity of the book, it didn't take long for live performances to begin. One early example is '']'', a ] by H. Saville Clark (book) and ] (music), which played in 1886 at the ] in London. | |||

| The entire print run sold out quickly. ''Alice'' was a publishing sensation, beloved by children and adults alike.<ref name="published"/> ] was a fan;<ref>{{cite book|last=Belford|first=Barbara|title=Oscar Wilde: A Certain Genius|publisher=]|year=2000|isbn=0-7475-5027-1|page=]|oclc=44185308}}</ref> ] was also an avid reader of the book.{{sfn|Pudney|1976|p=79}} She reportedly enjoyed ''Alice'' enough that she asked for Carroll's next book, which turned out to be a mathematical treatise; Carroll denied this.{{sfn|Pudney|1976|p=80}} The book has never been out of print.<ref name="published"/> ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' has been translated into 174 languages.<ref name="appleton2015">{{cite web|last=Appleton|first=Andrea|date=23 July 2015|title=The Mad Challenge of Translating "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland"|url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/mad-challenge-translating-alices-adventures-wonderland-180956017/|access-date=2022-01-25|website=]|archive-date=25 January 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220125032754/https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/mad-challenge-translating-alices-adventures-wonderland-180956017/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| As the book and its sequel are Carroll's most widely recognized works, they have also inspired numerous live performances, including ], ]s, ]s, and traditional English ]s. These works range from adaptations which are fairly faithful to the original book to those which use the story as a basis for new works. A good example of the latter is ''The Eighth Square'', a murder mystery set in Wonderland, written by ] and music and lyrics by Ben J. Macpherson. This goth-toned rock musical premiered in 2006 at the New Theatre Royal in ], England. The TA Fantastika, a popular ] in ] performs "Aspects of Alice"; written and directed by Petr Kratochvíl. This adaptation is not faithful to the books, but rather explores Alice's journey into adulthood while incorporating allusions to the history of Czech Republic. | |||

| === Publication timeline === | |||

| Over the years, many notable people in the performing arts have been involved in ''Alice'' productions. Actress ] famously adapted both Alice books for the stage in 1932; this production has been revived in New York in 1947 and 1982. One of the most well-known American productions was ]'s 1980 staging of ''Alice in Concert'' at the ] in New York City. ] wrote the book, lyrics, and music. Based on both ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' and ''Through the Looking-Glass'', Papp and Swados had previously produced a version of it at the ]. ] played Alice, the White Queen, and Humpty Dumpty. The cast also included ], ], and ]. Performed on a bare stage with the actors in modern dress, the play is a loose adaptation, with song styles ranging the globe. This production can be found on DVD. | |||

| ] on ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' expired in the UK, entering the tale into the ]. Since the story was intimately tied to the illustrations by ], new illustrated versions were then received with some significant objection by English reviewers.<ref name="Jaques-Giddens-2016-p139"/> In 2010, artist ] received the CG Choice Award for his ] "Alice in Wonderland".]] | |||

| The following list is a timeline of major publication events related to ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'': <!-- prefer image for some edition worth listing --> | |||

| Similarly, the 1992 operatic production ''Alice'' used both ''Alice'' books as its inspiration. However, it also employs scenes with Charles Dodgson, a young Alice Liddell, and an adult Alice Liddell, to frame the story. Paul Schmidt wrote the play, with ] and ] writing the music. Although the original production in ], Germany, received only a small audience, Tom Waits released the songs as the album '']'' in 2002, to much acclaim. | |||

| *'''1869''': Published in German as ''Alice's Abenteuer im Wunderland'', translated by Antonie Zimmermann.{{sfn|Taylor|1985|p=56}} | |||

| In addition to professional performances, school productions abound. Both high schools and colleges have staged numerous versions of ''Alice''-inspired performances. The imaginative story and large number of characters are well-suited to such productions. | |||

| *'''1869''': Published in French as ''Aventures d'Alice au pays des merveilles'', translated by Henri Bué.{{sfn|Taylor|1985|p=59}} | |||

| *'''1870''': Published in Swedish as ''Alice's Äventyr i Sagolandet'', translated by Emily Nonnen.{{sfn|Taylor|1985|p=81}} | |||

| *'''1871''': Carroll meets another Alice, Alice Raikes, during his time in London. He talks with her about her reflection in a mirror, leading to the sequel, '']'', which sells even better. | |||

| *'''1872''': Published in Italian as ''Le Avventure di Alice nel Paese delle Meraviglie'', translated by Teodorico Pietrocòla Rossetti.{{sfn|Taylor|1985|p=64}} | |||

| *'''1886''': Carroll publishes a ] of the earlier ''Alice's Adventures Under Ground'' manuscript.{{sfn|St. John|1975|p=335}} | |||

| *'''1890''': Carroll publishes '']'', an abridged version, around Easter.{{sfn|Cohen|1996|p=440–441}} | |||

| *'''1905''': Mrs J. C. Gorham publishes '']'' in a series of such books published by ] Company, aimed at young readers. | |||

| *'''1906''': Published in Finnish as ''Liisan seikkailut ihmemaailmassa'', translated by ].{{sfn|Taylor|1985|p=56}} | |||

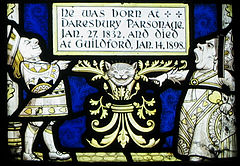

| *'''1907''': Copyright on ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' expires in the UK, entering the tale into the ],{{sfn|Weaver|1964|p=28}}<ref name="Jaques-Giddens-2016-p139">{{harvnb|Jaques|Giddens|2016|p=139}}: "The public perception of ''Alice'' was ... intimately tied to the illustrations created by Tenniel, and it is therefore perhaps no great surprise that when copyright to ''Wonderland'' expired in 1907, the appearance of a plethora of new illustrated versions was received with some significant objection by English reviewers."</ref> ], some nine years after Carroll's death in January 1898. | |||

| *'''1910''': Published in Esperanto as ''La Aventuroj de Alicio en Mirlando,'' translated by E. L. Kearney.{{sfn|Taylor|1985|p=56}} | |||

| *'''1915''': ]'s stage adaptation premieres.{{sfn|Marill|1993|p=56}}<ref>{{cite book|last=Shafer|first=Yvonne|title=American Women Playwrights, 1900–1950|year=1995|publisher=]|isbn=0-8204-2142-1|oclc=31754191|page=]}}</ref> | |||

| *'''1928''': The manuscript of ''Alice's Adventures Under Ground'' written and illustrated by Carroll, which he had given to Alice Liddell, was sold at ] in London on 3 April. It was sold to ] of Philadelphia for {{Currency|15400|POUND}}, a world record for the sale of a manuscript at the time; the buyer later presented it to the ] (where the manuscript remains) as an appreciation for Britain's part in two World Wars.<ref>{{cite book |last = Basbanes |first = Nicholas |author-link = Nicholas A. Basbanes |title = A Gentle Madness: Bibliophiles, Bibliomanes, and the Eternal Passion for Books |publisher = ] |year = 1999 |isbn = 978-0-8050-6176-5|title-link = A Gentle Madness: Bibliophiles, Bibliomanes, and the Eternal Passion for Books |pages=]}}</ref><ref>{{cite magazine|title=Rare Manuscripts|pages=101–105|magazine=]|date=15 April 1946|volume=20|issue=15|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-VQEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA101|access-date=24 January 2022|archive-date=24 January 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220124162800/https://books.google.com/books?id=-VQEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA101|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| *'''1960''': American writer ] publishes a special edition, '']''.{{sfn|Guiliano|1980|pp=12–13}} | |||

| *'''1988''': Lewis Carroll and ], illustrator of an edition from Julia MacRae Books, win the ].<ref>{{cite book|last=Watson|first=Victor|title=The Cambridge Guide to Children's Books in English|publisher=]|year=2001|isbn=0-521-55064-5|pages=]|oclc=45413558}}</ref> | |||

| *'''1998''': Carroll's own copy of Alice, one of only six surviving copies of the 1865 first edition, is sold at an auction for ]1.54 million to an anonymous American buyer, becoming the most expensive children's book (or 19th-century work of literature) ever sold to that point.<ref>{{cite news |periodical=] |date=11 December 1998 |title=Auction Record for an Original 'Alice' |page=B30 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1998/12/11/nyregion/auction-record-for-an-original-alice.html |access-date=14 February 2017 |archive-date=9 November 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161109221645/http://www.nytimes.com/1998/12/11/nyregion/auction-record-for-an-original-alice.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| *'''1999''': Lewis Carroll and ], illustrators of an edition from ], win the ] for integrated writing and illustration.{{sfn|Stan|2002|pp=233–234}} | |||

| *'''2008''': Folio publishes ''Alice's Adventures Under Ground'' ] (limited to 3,750 copies, boxed with ''The Original Alice'' pamphlet). | |||

| *'''2009''': Children's book collector and former American football player ] reportedly sold Alice Liddell's own copy at auction for US$115,000.<ref>{{cite news|date=17 December 2009|title=Real Alice in Wonderland book sold for $115,000|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/england/oxfordshire/8416127.stm|access-date=15 January 2022|work=]|archive-date=2 November 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211102095349/http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/england/oxfordshire/8416127.stm|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| == Reception == | |||

| A large-scale operatic adaptation of the story by the Korean composer ] to an English language libretto by ] received its world premiere at the ] on 30 June 2007. | |||

| ]. Exhibited at the ], it depicts a mother reading the book to her child (whose light blue dress and white pinafore was inspired by Alice).]] | |||

| ''Alice'' was published to critical praise.{{sfn|Cohen|1996|p=131}} One magazine declared it "exquisitely wild, fantastic, impossible".{{sfn|Turner|1989|pp=420–421}} In the late 19th century, ] wrote that ''Alice in Wonderland'' "was a book of that extremely rare kind which will belong to all the generations to come until the language becomes obsolete".{{sfn|Carpenter|1985|p=68}} | |||

| {{quote|No story in English literature has intrigued me more than Lewis Carroll's ''Alice in Wonderland''. It fascinated me the first time I read it as a schoolboy.|] in '']'', 1946.{{sfn|Nichols|2014|p=106}}}} | |||

| A new musical titled "Wonderland" made its premiere in Tampa, Florida in December of 2009 | |||

| ] argued in a 1932 book that ''Alice'' ended an era of ] in ], inaugurating a new era in which writing for children aimed to "delight or entertain".{{sfn|Susina|2009|p=3}} In 2014, ] named ''Alice'' "one of the best loved in the English canon" and called it "perhaps the greatest, possibly most influential, and certainly the most world-famous Victorian English fiction".<ref name="published"/> A 2020 review in '']'' states: "The book changed young people's literature. It helped to replace stiff Victorian didacticism with a looser, sillier, nonsense style that reverberated through the works of language-loving 20th-century authors as different as ], ] and ]."<ref name="Time">{{cite news|first=Judy|last=Berman|title=Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll|url=https://time.com/collection/100-best-fantasy-books/5897157/alices-adventures-in-wonderland/|access-date=8 May 2021|date=15 October 2020|magazine=Time|archive-date=14 May 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210514131729/https://time.com/collection/100-best-fantasy-books/5897157/alices-adventures-in-wonderland/|url-status=live}}</ref> The protagonist of the story, Alice, has been recognised as a ].<ref>{{cite book|title=Men in Wonderland: The Lost Girlhood of the Victorian Gentlemen|author=Robson, Catherine|year=2001|publisher=]|page=137}}</ref> In 2006, ''Alice in Wonderland'' was named among the icons of England in a public vote.<ref>{{cite news |title=Tea and Alice top 'English icons' |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/4592476.stm |access-date=18 September 2022 |work=BBC |archive-date=26 April 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090426152239/http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/4592476.stm |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The Philadelphia composer, ] has written an Alice ballet and dramaturgy for Actor, flute (doubling melodica), alto saxophone, harp, percussion, and string trio with seven dancers. It was commissioned by the San Diego chamber music organization, ], and the ]. <ref>http://www.artofelan.org/</ref> | |||

| == Adaptations and influence == | |||

| ==Criticism== | |||

| {{Main|Works based on Alice in Wonderland|l1=Works based on Alice in Wonderland|Films and television programmes based on Alice in Wonderland|l2=Films and television programmes based on Alice in Wonderland}} | |||

| The book was generally received in a positive light, but has also caught a large amount of derision for its strange and unpredictable tone.{{Citation needed|date=July 2009}} One of the best-known critics is fantasy writer ], who has stated that he dislikes the book: | |||

| {{Multiple image | |||

| {{quote|I didn't like the ''Alice'' books because I found them creepy and horribly unfunny in a nasty, plonking, Victorian way. Oh, here's Mr Christmas Pudding On Legs, hohohoho, here's a Caterpillar Smoking A Pipe, hohohoho. When I was a kid the books created in me about the same revulsion as you get when, aged seven, you're invited to kiss your great-grandmother.<ref>. Retrieved from Unseen University 29 January 2007.</ref>}} | |||

| | direction = vertical | |||

| | width = 210 | |||

| | image1 = Alice in Wonderland (1903 film).jpg | |||

| | image2 = Halloween Parade 2015 (22095223298).jpg | |||

| | caption1 = Screenshot of the British silent film '']'' (1903), the first screen adaptation of the book, which the ] called a "landmark fantasy"<ref>{{cite news |title=Alice in Wonderland 150th anniversary: 8 very different film versions |url=https://www.bfi.org.uk/lists/alice-wonderland-eight-very-different-film-versions |access-date=10 May 2023 |agency=British Film Institute |archive-date=31 December 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221231060557/https://www.bfi.org.uk/lists/alice-wonderland-eight-very-different-film-versions |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| | caption2 = ] costumes of Alice and the Queen of Hearts, 2015 | |||

| | align = | |||

| | total_width = | |||

| }} | |||

| Books for children in the ''Alice'' mould emerged as early as 1869 and continued to appear throughout the late 19th century.{{sfn|Carpenter|1985|pp=57–58}} Released in 1903, the British silent film '']'' was the first screen adaptation of the book.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Jaques |first1=Zoe |last2=Giddens |first2=Eugene |title=Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass: A Publishing History |date=2012 |publisher=Routledge |page=202}}</ref> | |||

| In 1931, the book was ] in ], China, because "animals should not use human language" and it "puts animals and human beings on the same level." | |||

| In ] in Haverhill, ], the story also was banned, because it had "expletives, references to masturbation and sexual fantasies, and derogatory characterizations of teachers and of religious ceremonies." <ref> The original reference (http://sshl.ucsd.edu/banned/books.html "Banned Books Week: 25 September–2 October) does not exist anymore (31. January 2010).</ref> | |||

| In 2015, ] wrote in the '']'', | |||

| ==Works influenced== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| {{quote|Since the first publication of ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' 150 years ago, Lewis Carroll's work has spawned a whole industry, from films and theme park rides to products such as a "cute and sassy" Alice costume ("petticoat and stockings not included"). The blank-faced little girl made famous by John Tenniel's original illustrations has become a cultural inkblot we can interpret in any way we like.<ref name="Alice industry">{{cite news|last1=Douglas-Fairhurst|first1=Robert|date=20 March 2015|title=Alice in Wonderland: the never-ending adventures|url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/mar/20/lewis-carroll-alice-in-wonderland-adventures-150-years|access-date=26 January 2022|work=]|ref={{sfnRef|Douglas-Fairhurst|2015b}}|archive-date=1 December 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211201015850/https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/mar/20/lewis-carroll-alice-in-wonderland-adventures-150-years|url-status=live}}</ref>}} | |||

| {{Main|Works based on Alice in Wonderland}} | |||

| Alice and the rest of Wonderland continue to inspire or influence many other works of art to this day, sometimes indirectly via the ], for example. The character of the plucky, yet proper, Alice has proven immensely popular and inspired similar heroines in literature and pop culture, many also named Alice in homage.<!--Instead of expanding this section, please add information to the works influenced article above.--> | |||