| Revision as of 10:32, 7 April 2005 editHoary (talk | contribs)Administrators77,848 edits →Restaurants: stylistic stuff← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 18:44, 16 December 2024 edit undoAnas1712 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users34,476 edits →Further reading | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Ethnic enclave of expatriate Chinese persons}} | |||

| :''Alternative meanings: ]'' | |||

| {{Redirect|Little China|the ideology|Little China (ideology)}} | |||

| {{other uses}} | |||

| {{pp-move}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=February 2024}} | |||

| {{Infobox Chinese | |||

| | pic = Chinatown - East Broadway.jpg | |||

| | piccap = ]'s Manhattan ] has the highest concentration of ] outside of ].<ref name="Manhattan Chinatown Largest Concentration Chinese Western Hemisphere" /><ref name="fact-sheet" /><ref name="NYC Twelve Chinatowns" /> | |||

| | c = {{linktext|唐人街}} | |||

| | p = Tángrénjiē | |||

| | w = Tʻang<sup>2</sup> jen<sup>2</sup> chieh<sup>1</sup> | |||

| | mi = {{IPAc-cmn|t|ang|2|.|r|en|2|.|j|ie|1}} | |||

| | bpmf = ㄊㄤˊ ㄖㄣˊ ㄐㄧㄝ | |||

| | l = "] people street" | |||

| | j = Tong4 jan4 gaai1 | |||

| | y = Tòhngyàhngāai | |||

| | ci = {{IPAc-yue|t|ong|4|-|j|an|4|-|g|aai|1}} | |||

| | wuu = Daon<sup>平</sup> nin<sup>平</sup> ka<sup>平</sup> | |||

| | poj = Tông-jîn-ke | |||

| | buc = Tòng-ìng-kĕ | |||

| | s2 = 中国城 | |||

| | t2 = {{linktext|中國城}} | |||

| | p2 = Zhōngguóchéng | |||

| | w2 = Chung<sup>1</sup>-kuo<sup>2</sup> chʻeng<sup>2</sup> | |||

| | mi2 = {{IPAc-cmn|zh|ong|1|.|g|uo|2|.|ch|eng|2}} | |||

| | bpmf2 = ㄓㄨㄥ ㄍㄨㄛˊ ㄔㄥˊ | |||

| | l2 = "China-town" | |||

| | j2 = Zung1 gwok3 sing4 | |||

| | y2 = Jūnggwoksìhng | |||

| | ci2 = {{IPAc-yue|z|ung|1|.|gw|ok|3|.|s|ing|4}} | |||

| | wuu2 = Tson<sup>平</sup> koh<sup>入</sup> zen<sup>平</sup> | |||

| | poj2 = Tiong-kok-siânn | |||

| | buc2 = Dŭng-guók-siàng | |||

| | s3 = 华埠 | |||

| | t3 = {{linktext|華埠}} | |||

| | p3 = Huábù | |||

| | w3 = Hua<sup>2</sup> pu<sup>4</sup> | |||

| | mi3 = {{IPAc-cmn|h|ua|2|.|b|u|4}} | |||

| | bpmf3 = ㄏㄨㄚˊ ㄅㄨˋ | |||

| | l3 = "] district" | |||

| | j3 = Waa4 fau6 | |||

| | y3 = Wàhfauh | |||

| | ci3 = {{IPAc-yue|w|aa|4|-|f|au|6}} | |||

| | wuu3 = Gho<sup>平</sup> bu<sup>去</sup> | |||

| | poj3 = Hôa-bú | |||

| | buc3 = Huà-pú | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Chinatown}} | |||

| '''Chinatown''' ({{zh|t=唐人街}}) is the catch-all name for an ] of ] located outside ], most often in an urban setting. Areas known as "Chinatown" exist throughout the world, including Europe, Asia, Africa, Oceania, and the Americas. | |||

| The development of most Chinatowns typically resulted from ] to an area without any or with few Chinese residents. ] in ], established in 1594, is recognized as the world's oldest Chinatown. Notable early examples outside Asia include ]'s ] in the United States and ]'s ] in Australia, which were founded in the early 1850s during the ] and ] gold rushes, respectively. A more modern example, in ], was caused by the displacement of Chinese workers in ] following the ] in 2001.<ref>{{cite AV media|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a2dbKSxna6k|title=Connecticut's Unexpected Chinatowns|via=]|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161031214821/http://www.citylab.com/amp/article/440190/|archive-date=2016-10-31}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.norwichbulletin.com/news/20160722/fortune-friction-and-decline-as-casino-chinatown-matures|title=Fortune, friction and decline as casino 'Chinatown' matures|author=Philip Marcelo |agency=The Associated Press|website=The Bulletin}}{{Dead link|date=December 2021 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> | |||

| ] is in ], ], where signs, storefronts, proprietors, and even lamp posts bring the culture of China to the United States.]] | |||

| ==Definition== | |||

| A '''Chinatown''' is an urban region containing a large population of ] people within a non-Chinese society. Chinatowns are most common in ] and ], but growing Chinatowns can be found in ] and ]. | |||

| ] defines "Chinatown" as "...{{nbsp}}a district of any non-Asian town, especially a city or ], in which the population is predominantly of Chinese origin".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/definition/american_english/Chinatown|title=Definition of Chinatown|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140228215015/http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/definition/american_english/Chinatown|archive-date=2014-02-28}}</ref> However, some Chinatowns may have little to do with China.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.kitv.com/news/hawaii/where-you-live/where-you-live-chinatown/24595340 |title=Where You Live Chinatown |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140301230646/https://www.kitv.com/news/hawaii/where-you-live/where-you-live-chinatown/24595340 |archive-date=2014-03-01 }}</ref> Some "Vietnamese" enclaves are in fact a city's "second Chinatown", and some Chinatowns are in fact ], meaning they could also be counted as a ] or ].<ref>{{cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/littlesaigonssta0000agui |url-access=registration |page= |title=Little Saigons: Staying Vietnamese in America|publisher=U of Minnesota Press |isbn=9780816654857|last1=Juan|first1=Karin Aguilar-San|year=2009}}</ref> One example includes ] in ], ]. It was initially referred to as a ] but was subsequently renamed due to the influx of non-Chinese ] who opened businesses there. Today the district acts as a unifying factor for the Chinese, Taiwanese, Korean, Japanese, Filipino, Indian, Vietnamese, Cambodian, Laotian, Nepalese and Thai communities of Cleveland.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.unmiserable.com/cleveland/archive/?p%3D713 |title=Archived copy |access-date=2016-02-21 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304101411/http://www.unmiserable.com/cleveland/archive/?p=713 |archive-date=2016-03-04 }}</ref> | |||

| Further ambiguities with the term can include Chinese ]s which by definition are "...{{nbsp}}] ethnic clusters of residential areas and business districts in large metropolitan areas<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.uhpress.hawaii.edu/p-5743-9780824836719.aspx|title=Ethnoburb: The New Ethnic Community in Urban America|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140303214959/http://www.uhpress.hawaii.edu/p-5743-9780824836719.aspx|archive-date=2014-03-03}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-06-26/asians-in-thriving-enclaves-keep-distance-from-whites.html|title=Asians in Thriving Enclaves Keep Distance From Whites|newspaper=Bloomberg.com |date=26 June 2013 |access-date=2 May 2018|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150122212519/http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-06-26/asians-in-thriving-enclaves-keep-distance-from-whites.html|archive-date=22 January 2015}}</ref> An article in '']'' blurs the line further by categorizing very different Chinatowns such as ], which exists in an urban setting as "traditional"; ], which exists in a "suburban" setting (and labeled as such); and ], which is in essence a "fabricated" Chinese-themed mall. This contrasts with narrower definitions, where the term only described Chinatown in a city setting.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/26/travel/chinatown-revisited.html|title=Chinatown Revisited|newspaper=The New York Times |date=24 January 2014 |url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170706171445/https://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/26/travel/chinatown-revisited.html?_r=0|archive-date=2017-07-06|last1=Tsui |first1=Bonnie }}</ref> | |||

| Chinatowns were formed in the ] in many areas of the ] and ] as a result of discriminatory land laws which forbade the sale of any land to Chinese or restricted the land sales to a limited geographical area and which promoted the segregation of people of different ethnicities. The location of a Chinatown in a particular city may change or disappear over time. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| Chinatowns were established in European port cities as Chinese traders settled down in the area. Chinatowns are also found in the ]n cities of ] and ]. | |||

| {{See also|Chinese emigration}} | |||

| ] populated predominantly by Chinese men and their native spouses have long existed throughout ]. ] to other parts of the world from China accelerated in the 1860s with the signing of the ] (1860), which opened China's borders to free movement. Early emigrants came primarily from the coastal ] of ] (Canton, Kwangtung) and ] (Fukien, Hokkien) in ] – where the people generally speak ], ], ], ] (Chiuchow) and ]. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, a significant amount of ] to North America originated from four counties called ], located west of the ] in ] province, making Toishanese a dominant ] of the ] spoken in ]. | |||

| As conditions in China have improved in recent decades, many Chinatowns have lost their initial mission, which was to provide a transitional place into a new culture. As net migration has slowed into them, the smaller Chinatowns have slowly decayed, often to the point of becoming purely historical and no longer serving as ]s.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://nhpr.org/post/chinatown-ghost-town |title=From Chinatown to Ghost Town |publisher=NHPR |date=2011-11-14 |access-date=2013-05-26 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131101042729/http://nhpr.org/post/chinatown-ghost-town |archive-date=2013-11-01 }}</ref> | |||

| In the past, overcrowded Chinatowns in urban areas were shunned by the general non-Chinese public as ethnic ]es, and therefore seen as places of vice and cultural insularism where "unassimilable foreigners" congregated. Nowadays, many old and new Chinatowns are considered viable centers of ] and ]; some of them also serve, in various degrees, as centers of ] (espoused in Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom) and "racial harmony" (especially in Malaysia and Singapore). | |||

| ===In Asia=== | |||

| Quite a number of Chinatowns have a Disneyland-esque atmosphere, while others are actual living and working communities; some are a synthesis of both. Chinatowns also range from rundown ghettoes to sites of recent development. In some Chinatowns, recent investments have revitalized run-down and blighted areas and turned them into centers of vibrant economic and social activity in recent years. In some cases this has led to ] and a reduction in the specifically Chinese character of the neighborhoods. | |||

| ], ], home to the world's oldest Chinatown]] | |||

| In the ], where the oldest surviving Chinatowns are located, the district where Chinese migrants ('']es'') were required to live is called a ], which were also often a marketplace for trade goods. Most of them were established in the late 16th century to house Chinese migrants as part of the early Spanish colonial policy of ethnic segregation. There were numerous pariáns throughout the Philippines in various locations, the names of which still survive into modern district names. This include the ] of ], ] (which was eventually moved several times, ending up in ]). The term was also carried into ] by Filipino migrants.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Dela Cerna |first1=Madrilena |title=Parian in Cebu |url=http://www.ncca.gov.ph/about-culture-and-arts/articles-on-c-n-a/article.php?igm=2&i=188 |website=National Commission for Culture and the Arts |publisher=Republic of the Philippines |access-date=12 October 2023 |archive-date=24 February 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140224131510/http://www.ncca.gov.ph/about-culture-and-arts/articles-on-c-n-a/article.php?igm=2&i=188 |url-status=bot: unknown }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=The Parian and the Spanish Colonial Economy |url=https://intramuros.gov.ph/2020/10/16/the-parian-and-the-spanish-colonial-economy/ |website=Intramuros Administration, Republic of the Philippines |access-date=12 October 2023 |archive-date=October 29, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231029214134/https://intramuros.gov.ph/2020/10/16/the-parian-and-the-spanish-colonial-economy/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="pacs.ph">{{cite journal |last1=Burton |first1=John William |title=The Word Parian: An Etymological and Historical Adventure |journal=The Ethnic Chinese as Filipinos (Part III) |date=2000 |volume=8 |pages=67–72 |url=https://www.pacs.ph/the-ethnic-chinese-as-filipinos-part-3-2000/ |access-date=October 12, 2023 |archive-date=October 29, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231029214132/https://www.pacs.ph/the-ethnic-chinese-as-filipinos-part-3-2000/ |url-status=live }}</ref> The central market place of ] (now part of ]) selling imported goods from the ] in the 18th and early 19th centuries was called "Parián de Manila" (or just "Parián").<ref>{{cite book |last1=Fish |first1=Shirley |title=The Manila-Acapulco galleons: the treasure ships of the Pacific ; with an annotated list of the transpacific galleons 1565 - 1815 |date=2011 |publisher=AuthorHouse |location=Central Milton Keynes |isbn=9781456775438 |page=438}}</ref> | |||

| Along the coastal areas of ], several Chinese settlements existed as early as the 16th century according to ] and ]' travel accounts. Melaka during the Portuguese colonial period, for instance, had a large Chinese population in Campo China. They settled down at port towns under the authority's approval for trading. After the European colonial powers seized and ruled the port towns in the 16th century, Chinese supported European traders and colonists, and created autonomous settlements. | |||

| Many Chinatowns have a long history, such as '']'', the nearly three centuries old Chinatown in ], ]. Other Chinatowns are much more recent developments: the Chinatown in ], ], ] formed in the 1990s. Most Chinatowns grew without any organized plans, while a few Chinatowns (such as the one in Las Vegas and a new one outside the city limits of ], ] to be completed by 2005 ) resulted from deliberate master plans (sometimes as part of redevelopment project). Indeed, many areas of the world are embracing the development and redevelopment (or regeneration) of Chinatowns, such as in ], the ], South Korea, and the ]. In ] and ], ] ideology and anti-Chinatown sentiments have made efforts at such redevelopment more challenging. | |||

| Several Asian Chinatowns, although not yet called by that name, have a long history. Those in ], ], and ], Japan,<ref>{{cite book|last=Takekoshi|first=Yosaburo|title=economic aspects of the history of the civilization of Japan, Vol. 2|year=2004|publisher=Routledge|location=London|page=124}}</ref> ] in Manila, ] and Bao Vinh in central Vietnam<ref>{{cite book|last=Li|first=Qingxin|title=Maritime Silk Road|year=2006|publisher=China International Press|page=157}}</ref> all existed in 1600. ], the Chinese quarter of ], dates to 1740.<ref>{{cite book|last=Abeyesekere |first=Susan |title=Jakarta: A History|year=1987|publisher=Oxford University Press. All rights reserved|page=6 }}</ref> | |||

| ]'' to Chinatown in ], ], which is located in ] around Gerrard Street, Lisle Street and Shaftesbury Avenue.]] | |||

| Chinese presence in India dates back to the 5th century CE, with the first recorded Chinese settler in ] named Young Atchew around 1780.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/world/archives/2004/07/31/2003181147|title=Calcutta's Chinatown facing extinction over new rule |newspaper=Taipei Times |date=31 July 2004|access-date=2 May 2018|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110513234646/http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/world/archives/2004/07/31/2003181147|archive-date=13 May 2011}}</ref> Chinatowns first appeared in the Indian cities of ], ], and ]. | |||

| ==Names== | |||

| In ], Chinatown is usually called in ] '''''Tángrénjiē''''' (唐人街): ''"] people ]"''. The literal translation of the word is an uncommon term for '']'', used here since the ], which make up a large proportion of immigrants, were only fully brought under imperial control under the Tang Dynasty). Indeed, some Chinatowns are just a street, such as the relatively short Fisgard Street in ], ], Canada or the sprawling 4-mile long new Chinatown of Bellaire Boulevard in ], United States. In Cantonese, it is '''''Tong yan gai''''' (''Tang people street'') and the modern '''''Tong yan fau''''' (唐人鎮), which literally means ''Tang people town'' or more accurately, ''Chinese town''. It is '''''Tong ngin gai''''' in Hakka, one of the widely spoken and diffused ] among ]. ''Tang'' and ''Tong'' refer to the ], an era in Chinese history. | |||

| The ] centered on ] in ], ], was founded at the same time as the city itself, in 1782.<ref>{{cite web|publisher=]|url=http://www.tour-bangkok-legacies.com/yaowarat-heritage-centre.html|title=The History of Chinatown Bangkok|access-date=2 October 2011|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110920194046/http://www.tour-bangkok-legacies.com/yaowarat-heritage-centre.html|archive-date=20 September 2011}}</ref> | |||

| A more modern Chinese name is '''''Huábù''''' (華埠: ''Chinese City'') which is used in the semi-official Chinese translations of some cities' documents and signs. ''Bù'', pronounced sometimes as ''fù'', usually means ''seaport''; but in this sense, it means ''city'' or ''town''. The literal word-to-word translation of ''Chinatown'' is '''''Zhōngguó Chéng''''' (中國城), which is occasionally used in Chinese writing. | |||

| ===Outside of Asia=== | |||

| In ] regions (such as ] and ], ]), Chinatown is often referred to as '''''le quartier Chinois''''' (''the Chinese Quarter''; plural: '''''les quartiers Chinois''''') and the Spanish-language term is usually '''''el barrio chino''''' (''the Chinese neighborhood''; plural: '''''los barrios chinos'''''), used in ] and ]. (However, ''barrio chino'' or its ] cognate ''barri xines'' do not always refer to a Chinese neighborhood: these are also common terms for a disreputable district with drugs and prostitution, and often no connection to the Chinese.) Other countries also have names for Chinatown in local languages; however, some local terms may not necessarily translate as ''Chinatown''. For example, Singapore's tourist-centric Chinatown is called in local Singaporean Mandarin ''Niúchēshǔi'' (牛车水), which literally means "Ox-cart water". Some languages have adopted the English language term, such as in Dutch, German, and Bahasa Malaysia. | |||

| ] is the longest continuous Chinese settlement in the ] and the oldest Chinatown in the ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://chinatownmelbourne.com.au/|title=Chinatown Melbourne|access-date=23 January 2014|archive-date=January 25, 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140125022815/http://chinatownmelbourne.com.au/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/ABOUTMELBOURNE/HISTORY/Pages/multiculturalhistory.aspxt|title=Melbourne's multicultural history|publisher=]|access-date=23 January 2014|archive-date=September 30, 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230930190838/https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/about-melbourne/melbourne-heritage/Pages/melbourne-heritage.aspx|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://matadornetwork.com/trips/worlds-8-most-colorful-chinatowns/|title=World's 8 most colourful Chinatowns|access-date=23 January 2014|archive-date=January 31, 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140131130906/http://matadornetwork.com/trips/worlds-8-most-colorful-chinatowns/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=The essential guide to Chinatown |url=https://www.melbournefoodandwine.com.au/read-watch/latest-news/news/the-essential-guide-to-chinatown-920 |website=Melbourne Food and Wine Festival |date=3 February 2021 |publisher=Food + Drink Victoria |access-date=11 February 2022 |archive-date=February 14, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220214234525/https://www.melbournefoodandwine.com.au/read-watch/latest-news/news/the-essential-guide-to-chinatown-920 |url-status=live }}</ref>]] Many Chinese immigrants arrived in Liverpool in the late 1850s in the employ of the ], a ] company established by ]. The ] ] created strong ] links between the cities of ], ], and Liverpool, mainly in the importation of silk, cotton, and ].<ref name="LCBA">{{cite web|title=History of Liverpool Chinatown |publisher=The Liverpool Chinatown Business Association |url=http://web.ukonline.co.uk/lcba/ba/history.html |access-date=31 January 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100124032329/http://web.ukonline.co.uk/lcba/ba/history.html |archive-date=24 January 2010 }}</ref> They settled near the docks in south Liverpool, this area was heavily bombed during World War II, causing the Chinese community moving to the current location ] on Nelson Street. | |||

| The ] is one of the largest in North America and the oldest north of Mexico. It served as a port of entry for early Chinese immigrants from the 1850s to the 1900s.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140106231830/https://diva.sfsu.edu/collections/sfbatv/bundles/191373 |date=2014-01-06 }}, KPIX-TV, 1963.</ref> The area was the one geographical region deeded by the city government and private property owners which allowed Chinese persons to inherit and inhabit dwellings within the city. Many Chinese found jobs working for large companies seeking a source of labor, most famously as part of the ]<ref name="Foster 2001">{{cite book|author=Lee Foster|title=Northern California History Weekends|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8VA0GAmdjK4C|access-date=26 December 2011|date=1 October 2001|publisher=Globe Pequot|isbn=978-0-7627-1076-8|page=13}}{{Dead link|date=January 2023 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> on the ]. Since it started in ], that city had a notable Chinatown for almost a century.<ref>Roenfeld, R. (2019) {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190306044231/https://northomahahistory.com/2019/03/05/a-history-of-omahas-chinatown-by-ryan-roenfeld/ |date=March 6, 2019 }}, NorthOmahaHistory.com. Retrieved March 5, 2019.</ref> Other cities in North America where Chinatowns were founded in the mid-nineteenth century include almost every major settlement along the West Coast from ] to ]. Other early immigrants worked as mine workers or independent prospectors hoping to strike it rich during the 1849 ]. | |||

| Several alternate English names for Chinatown include '''China Town''' (generally used in ] and ]), '''Chinese District''', '''Chinese Quarter''' and '''China Alley''' (an antiquated term used primarily in several ] towns in the ] for a Chinese community; these sites are now historical sites). | |||

| Economic opportunity drove the building of further Chinatowns in the United States. The initial Chinatowns were built in the ] in states such as ], ], ], ], ], ] and ]. As the ] was built, more Chinatowns started to appear in railroad towns such as ], ], ], ] and ]. Chinatowns then subsequently emerged in many ], including ], ], ], ] and ]. With the passage of the ], many ] such as ], ] and ] began to hire Chinese for work in place of slave labor.<ref name="Okihiro 2015">{{cite book|last=Okihiro|first=Gary Y.|title=American History Unbound: Asians and Pacific Islanders|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WaowDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA201|year=2015|publisher=University of California Press|location=Berkeley|isbn=978-0-520-27435-8|page=201|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180502225136/https://books.google.com/books?id=WaowDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA201|archive-date=2018-05-02}}</ref> | |||

| <!-- | |||

| == Origins of the term "Chinatown" - a social construction == | |||

| ''(To be written)'' | |||

| --> | |||

| The history of Chinatowns was not always peaceful, especially when ]s arose. Racial tensions flared when lower-paid Chinese workers replaced white miners in many mountain-area Chinatowns, such as in Wyoming with the ]. Many of these frontier Chinatowns became extinct as American racism surged and the ] was passed. | |||

| ==Settlement patterns== | |||

| With the overthrow of the ] by the ] in the late ], some Chinese fled to Japan and formed a Chinatown community in Nagasaki before the start of the 18th century, making it – along with the ] district of ] if the ] – one of the earliest Chinatowns to be established. | |||

| In Australia, the ], which began in 1851, attracted Chinese prospectors from the ] area. A community began to form in the eastern end of ], ] by the mid-1850s; the area is still the center of the ], making it the oldest continuously occupied Chinatown in a western city (since the San Francisco one was destroyed and rebuilt). Gradually expanding, it reached a peak in the early 20th century, with Chinese business, mainly furniture workshops, occupying a block wide swath of the city, overlapping into the adjacent ]' red light district. With restricted immigration it shrunk again, becoming a strip of Chinese restaurants by the late 1970s, when it was celebrated with decorative arches. However, with a recent huge influx of students from mainland China, it is now the center of a much larger area of noodle shops, travel agents, restaurants, and groceries. The ] also saw the development of a Chinatown in ], at first around ], near the docks, but it has moved twice, first in the 1890s to the east side of the Haymarket area, near the new markets, then in the 1920s concentrating on the west side.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/chinatown|title=Chinatown|website=Dictionary of Sydney|access-date=2019-10-26|archive-date=April 27, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190427115045/https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/chinatown|url-status=live}}</ref> Nowadays, ] is centered on Dixon Street. | |||

| In the early ], Chinese settlers established Chinatowns mainly in Southeast Asia (for example, the ] district of the former ], ]). Emigration from Mainland China to other parts of the world really took off in the ] with the enactment of ], which opened the border for free movement. The early immigrants came primarily from coastal province of ] and ] (Fukien) – where Cantonese, ] (Hokkien), ], and ] (Teochew, Chiu Chow) are largely spoken – in southeastern Mainland China. Initially, the Qing government of China did not care for the of these migrants leaving the country. As a dominant group, the Cantonese are linguistically and ethnically distinct from other groups in China; Cantonese remained the dominant language and heritage of many Chinatowns in Western countries until the 1970s. | |||

| Other Chinatowns in European capitals, including ] and ], were established at the turn of the 20th century. The first Chinatown in London was located in the ] area of the ]<ref>Sales, Rosemary; d'Angelo, Alessio; Liang, Xiujing; Montagna, Nicola. "London's Chinatown" in Donald, Stephanie; Kohman, Eleonore; Kevin, Catherine. (eds) (2009). {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240212165201/https://books.google.com/books?id=wVJkryx7cJAC&pg=PA45 |date=February 12, 2024 }}. ]. pp. 45–58.</ref> at the start of the 20th century. The Chinese population engaged in business which catered to the Chinese sailors who frequented the ]. The area acquired a bad reputation from exaggerated reports of ]s and ]. | |||

| ]ese and Cantonese settled in the first North American Chinatowns. The Cantonese mainly formed Chinatowns in North America and Latin America. As a port city, San Francisco's Chinatown formed in the 1850s and served as a gateway for incoming immigrants. The Hokkien and Teochew (both group speaking Minnan sub-group of Chinese dialects), along with Cantonese are the dominant group in Southeast Asian Chinatowns. The Hakka groups established Chinatowns in ], Latin America, and the ]. Northern Chinese settled in the Koreas in the 1940s. In Europe, early Chinese were seamen and longshoremen in European port cities. France received the largest settlement of the early Chinese immigrant laborers. | |||

| France received a large settlement of Chinese immigrant laborers, mostly from the city of ], in the ] province of China. Significant Chinatowns sprung up in ] and the ]. | |||

| By the late 1970s, the ] also played a significant part in the development and redevelopment of various Chinatowns in developed Western countries. As a result, many Chinatowns have become pan-Asian business districts and residential neighborhoods. By contrast, most Chinatowns in the past were solely inhabited by Chinese from southeastern ]. | |||

| {{Gallery |align=center | |||

| |File:Chinatown manhattan 2009.JPG|], the largest concentration of ] in the ]<ref name="Manhattan Chinatown Largest Concentration Chinese Western Hemisphere">{{cite web|url=https://www.introducingnewyork.com/chinatown|title=Chinatown New York|publisher=Civitatis New York|quote=As its name suggests, Chinatown is where the largest population of Chinese people live in the Western Hemisphere.|access-date=November 30, 2020|archive-date=April 4, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200404164227/https://www.introducingnewyork.com/chinatown|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="fact-sheet" /> and one of ],<ref name="NYC Twelve Chinatowns">{{cite web|url=https://ny.eater.com/2019/2/25/18236523/chinatowns-restaurants-elmhurst-homecrest-bensonhurst-east-village-little-neck-forest-hills-nyc|title=Believe It or Not, New York City Has Nine Chinatowns|author=Stefanie Tuder|publisher=EATER NY|date=February 25, 2019|access-date=November 30, 2020|archive-date=February 26, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190226081349/https://ny.eater.com/2019/2/25/18236523/chinatowns-restaurants-elmhurst-homecrest-bensonhurst-east-village-little-neck-forest-hills-nyc|url-status=live}}</ref> as well as one of twelve in the surrounding ]|File: Brooklyn_Chinatown.png|], the ] with the highest number of ] | |||

| |File:San Francisco Chinatown.jpg|], the oldest Chinatown in the US | |||

| |File:Boston Chinatown Paifang.jpg|], a Chinatown inspired and developed on the basis of modern ] concepts | |||

| |File:Friendship Gate Chinatown Philadelphia from west.jpg|], the recipient of significant ] from both ]<ref name="Chinese NYC to Philadelphia">{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/20/nyregion/philadelphia-new-york-migration-immigrants.html|title=Leaving New York to Find the American Dream in Philadelphia|author=Matt Katz|newspaper=The New York Times|date=July 20, 2018|access-date=November 10, 2019|archive-date=August 7, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180807001508/https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/20/nyregion/philadelphia-new-york-migration-immigrants.html|url-status=live}}</ref> and China<ref name="Philadelphia Foreign Born">{{cite news|url=https://www.philly.com/news/immigrants-philly-population-growth-foreign-born-20190510.html|title=Welcome to Philly: Percentage of foreign-born city residents has doubled since 1990|author=Jeff Gammage|newspaper=The Philadelphia Inquirer|date=May 10, 2019|access-date=November 10, 2019|quote=China is, far and away, the primary sending country, with 22,140 city residents who make up about 11 percent of the foreign-born population, according to a Pew Charitable Trusts analysis of Census data.|archive-date=May 10, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190510180258/https://www.philly.com/news/immigrants-philly-population-growth-foreign-born-20190510.html|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| |File:Chinese Arch - geograph.org.uk - 1021559.jpg|], the oldest Chinatown in Europe | |||

| }} | |||

| ===1970s to the present=== | |||

| ==Features== | |||

| By the late 1970s, refugees and exiles from the ] played a significant part in the redevelopment of Chinatowns in developed Western countries. As a result, many existing Chinatowns have become pan-Asian business districts and residential neighborhoods. By contrast, most Chinatowns in the past had been largely inhabited by Chinese from southeastern China. | |||

| These features are characteristic of most Chinatowns everywhere. In some cases, however, they may only apply to Chinatowns in Western countries, such as those in North America, Australia, and Western Europe. | |||

| In 2001, the events of ] resulted in a mass migration of about 14,000 Chinese workers from ] to ], due to the fall of the garment industry. Chinese workers transitioned to ] jobs fueled by the development of the ] casino. | |||

| ===Arches or ''Paifang''=== | |||

| Many tourist-destination metropolitan Chinatowns can be easily distinguished by large red arch-like structures known as '']'' with bronze lion statues on the opposite sides of the street. They usually have special inscriptions in Chinese. Historically, these gateways were donated to a particular city as a gift from the ] government and business organizations. Construction of these red arches was also financed by local financial contributions from the Chinatown community. The lengths of these arches vary from Chinatown to Chinatown; some span an entire intersection and some are smaller in height and width. The popular perception of Chinatown often includes these arches. | |||

| In 2012, ] formed as a result of availability of direct flights to China. The ] was formerly a small enclave, but has tripled in size as a result of direct flights to ]. It has an ethnic Chinese population rise from 5,000 in 2009 to roughly 15,000 in 2012, overtaking ]'s Chinatown as the largest Chinese enclave in Mexico. | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Wide image|Chinatown 1.jpg|600px|3=<div align=center>The busy intersection of ] and ] in the ], ], ], ]. The segment of Main Street between ] and Roosevelt Avenue, punctuated by the ] ] ] overpass, represents the cultural heart of Flushing Chinatown. Housing over 30,000 individuals born in China alone, the largest by this metric outside Asia, ] has become home to the largest and one of the fastest-growing Chinatowns in the world.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.businessinsider.com/i-ate-my-way-through-flushing-queens-and-now-i-get-why-its-the-bigger-and-better-chinatown-2015-5|title=This is what it's like in one of the biggest and fastest growing Chinatowns in the world|author=Melia Robinson|website=Business Insider|date=May 27, 2015|access-date=March 3, 2019|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170730033121/http://www.businessinsider.com/i-ate-my-way-through-flushing-queens-and-now-i-get-why-its-the-bigger-and-better-chinatown-2015-5|archive-date=July 30, 2017}}</ref> Flushing is undergoing rapid ] by Chinese transnational entities,<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/aug/13/flushing-queens-gentrification-luxury-developments|title='Not what it used to be': in New York, Flushing's Asian residents brace against gentrification|author=Sarah Ngu|newspaper=]|date=January 29, 2021|access-date=August 13, 2020|quote=The three developers have stressed in public hearings that they are not outsiders to Flushing, which is 69% Asian. 'They've been here, they live here, they work here, they've invested here,' said Ross Moskowitz, an attorney for the developers at a different public hearing in February...Tangram Tower, a luxury mixed-use development built by F&T. Last year, prices for two-bedroom apartments started at $1.15m...The influx of transnational capital and rise of luxury developments in Flushing has displaced longtime immigrant residents and small business owners, as well as disrupted its cultural and culinary landscape. These changes follow the familiar script of gentrification, but with a change of actors: it is Chinese-American developers and wealthy Chinese immigrants who are gentrifying this working-class neighborhood, which is majority Chinese.|archive-date=August 13, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200813091230/https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/aug/13/flushing-queens-gentrification-luxury-developments|url-status=live}}</ref> and the growth of the business activity at the core of ], dominated by the Flushing Chinatown, has continued despite the Covid-19 pandemic.<ref name=FlushingChinatownContinuesGrowth>{{cite web|url=https://www.curbed.com/2022/12/new-new-york-report-review-hochul-adams-doctoroff.html|title=Can the Hochul-Adams New New York Actually Happen?|author=Justin Davidson|publisher=Curbed - New York magazine|date=December 15, 2022|access-date=December 18, 2022|archive-date=December 18, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221218183018/https://www.curbed.com/2022/12/new-new-york-report-review-hochul-adams-doctoroff.html|url-status=live}}</ref> As of 2023, ] to ], and especially to the city's Flushing Chinatown, has accelerated.<ref name=NYCPrimaryChineseDestination>{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/24/us/politics/china-migrants-us-border.html|title=Growing Numbers of Chinese Migrants Are Crossing the Southern Border|author=Eileen Sullivan|newspaper=The New York Times|date=November 24, 2023|access-date=November 24, 2023|quote=Most who have come to the United States in the past year were middle-class adults who have headed to New York after being released from custody. New York has been a prime destination for migrants from other nations as well, particularly Venezuelans, who rely on the city’s resources, including its shelters. But few of the Chinese migrants are staying in the shelters. Instead, they are going where Chinese citizens have gone for generations: Flushing, Queens. Or to some, the Chinese Manhattan...“New York is a self-sufficient Chinese immigrants community,” said the Rev. Mike Chan, the executive director of the Chinese Christian Herald Crusade, a faith-based group in the neighborhood.|archive-date=November 25, 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231125055441/https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/24/us/politics/china-migrants-us-border.html?searchResultPosition=1|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| === Bilingual signs=== | |||

| </div>|dir=rtl}} | |||

| Many major metropolitan areas with Chinatowns have bilingual street signs in Chinese and the language of the adopted country. These signs are generally poorly translated by city planners. | |||

| The ], consisting of ], ], and nearby areas within the states of ], ], ], and ], is home to the largest Chinese-American population of any ] within the United States and the largest Chinese population outside of China, enumerating an estimated 893,697 in 2017,<ref name="NYC Chinese 1">{{cite web |url=https://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/ACS/17_1YR/S0201/330M400US408/popgroup~016|archive-url=https://archive.today/20200214002005/https://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/ACS/17_1YR/S0201/330M400US408/popgroup~016|url-status=dead|archive-date=February 14, 2020|title=Selected Population Profile in the United States 2017 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates New York-Newark, NY-NJ-CT-PA CSA Chinese alone|publisher=]|access-date=March 3, 2019}}</ref> and including at least 12 Chinatowns, including nine in New York City proper alone.<ref name="NYC Twelve Chinatowns" /> Steady ], both legal<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.dhs.gov/files/statistics/publications/LPR11.shtm|title=Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2011 Supplemental Table 2|date=13 April 2016|publisher=U.S. Department of Homeland Security|access-date=March 3, 2019|archive-date=August 8, 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120808080130/http://www.dhs.gov/files/statistics/publications/LPR11.shtm|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.dhs.gov/files/statistics/publications/LPR10.shtm|title=Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2010 Supplemental Table 2|publisher=U.S. Department of Homeland Security|access-date=10 April 2011|archive-date=July 12, 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120712200141/https://www.dhs.gov/files/statistics/publications/LPR10.shtm|url-status=live}}</ref> and illegal,<ref>{{cite news|url=http://articles.nydailynews.com/2011-05-09/news/29541916_1_illegal-chinese-immigrants-qm2-queen-mary|title=Malaysian man smuggled illegal Chinese immigrants into Brooklyn using Queen Mary 2: authorities|author=John Marzulli|newspaper=New York Daily News |date=9 May 2011|access-date=March 3, 2019|location=New York|archive-date=2015-05-05|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150505034445/http://www.nydailynews.com/news/world/malaysian-man-smuggled-illegal-chinese-immigrants-brooklyn-queen-mary-2-authorities-article-1.143516|url-status=dead}}</ref> has fueled Chinese-American population growth in the New York metropolitan area. New York's status as an alpha global city, its extensive mass transit system, and the New York metropolitan area's enormous economic marketplace are among the many reasons it remains a major international immigration hub. The ] contains the largest concentration of ethnic Chinese in the ],<ref name="fact-sheet">* {{cite web |url=http://www.explorechinatown.com/PDF/FactSheet.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://www.explorechinatown.com/PDF/FactSheet.pdf |archive-date=2022-10-09 |url-status=live |title=Chinatown New York City Fact Sheet |website=Explore Chinatown |access-date=March 2, 2019 }} | |||

| * {{cite web | |||

| |url=http://www.ny.com/articles/chinatown.html | |||

| |title=The History of New York's Chinatown | |||

| |author=Sarah Waxman | |||

| |publisher=Mediabridge Infosystems, Inc | |||

| |access-date=March 3, 2019 | |||

| |archive-date=May 25, 2017 | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170525014333/https://www.ny.com/articles/chinatown.html | |||

| |url-status=live | |||

| }} | |||

| * {{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NagJFMxtkAcC&q=Flushing+Chinatown+Little+Taiwan&pg=PA104 |title=Still the golden door: the Third ... – Google Books |author=David M. Reimers |access-date=April 11, 2016 |isbn=9780231076814 |year=1992 |publisher=Columbia University Press |archive-date=November 3, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231103153044/https://books.google.com/books?id=NagJFMxtkAcC&q=Flushing+Chinatown+Little+Taiwan&pg=PA104#v=snippet&q=Flushing%20Chinatown%20Little%20Taiwan&f=false |url-status=live }} | |||

| * {{cite web | |||

| |url=http://geographyplanning.buffalostate.edu/MSG%202002/13_McGlinn.pdf | |||

| |title=Beyond Chinatown: Dual immigration and the Chinese population of metropolitan New York City, 2000, Page 4 | |||

| |author=Lawrence A. McGlinn, Department of Geography SUNY-New Paltz | |||

| |publisher=Middle States Geographer | |||

| |year=2002 | |||

| |volume=35 | |||

| |pages=110–119 | |||

| |work=Journal of the Middle States Division of the Association of American Geographers | |||

| |access-date=March 3, 2019 | |||

| |url-status=dead | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121029075400/http://geographyplanning.buffalostate.edu/MSG%202002/13_McGlinn.pdf | |||

| |archive-date=October 29, 2012 | |||

| }} | |||

| * {{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NagJFMxtkAcC&q=Flushing+Chinatown+Little+Taiwan&pg=PA104 |title=Still the golden door: the Third ... – Google Books |author=David M. Reimers |access-date=April 11, 2016 |isbn=9780231076814 |year=1992 |publisher=Columbia University Press |archive-date=November 3, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231103153044/https://books.google.com/books?id=NagJFMxtkAcC&q=Flushing+Chinatown+Little+Taiwan&pg=PA104#v=snippet&q=Flushing%20Chinatown%20Little%20Taiwan&f=false |url-status=live }}</ref> and the ] in ] has become the world's largest Chinatown.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/behind-illicit-massage-parlors-lie-a-vast-crime-network-and-modern-indentured-servitude/ar-BBUhZgJ?li=BBnb7Kz&ocid=mailsignout|title=Behind Illicit Massage Parlors Lie a Vast Crime Network and Modern Indentured Servitude|first1=Nicholas |last1=Kulish|first2=Frances |last2=Robles|first3=Patricia |last3=Mazzei|newspaper=The New York Times|date=March 2, 2019|access-date=March 3, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190306043138/http://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/behind-illicit-massage-parlors-lie-a-vast-crime-network-and-modern-indentured-servitude/ar-BBUhZgJ?li=BBnb7Kz&ocid=mailsignout|archive-date=March 6, 2019|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| The ] has adversely affected tourism and business in Chinatown, San Francisco<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/travel/2020/11/30/san-francisco-chinatown-business-covid/|title=The country's oldest Chinatown is fighting for its life in San Francisco Covid-19 has decimated tourism in the neighborhood. Can its historic businesses survive?|author=Jada Chin|newspaper=The Washington Post|date=November 30, 2020|access-date=December 3, 2020|archive-date=December 2, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201202235502/https://www.washingtonpost.com/travel/2020/11/30/san-francisco-chinatown-business-covid/|url-status=live}}</ref> and ], Illinois<ref>{{cite news|url=https://herald-review.com/news/state-and-regional/chicagos-chinatown-takes-a-hit-as-coronavirus-fears-keep-customers-away-business-is-down-as/article_d7b72df2-d40c-5d30-afce-bb42baccae2e.html|title=Chicago's Chinatown takes a hit as coronavirus fears keep customers away. Business is down as much as 50% at some restaurants|author=Robert Channick|newspaper=Herald & Review|date=February 12, 2020|access-date=December 3, 2020|archive-date=April 27, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210427124131/https://herald-review.com/news/state-and-regional/chicagos-chinatown-takes-a-hit-as-coronavirus-fears-keep-customers-away-business-is-down-as/article_d7b72df2-d40c-5d30-afce-bb42baccae2e.html|url-status=live}}</ref> as well as others worldwide. | |||

| ===Antiquated features=== | |||

| Many early Chinatowns were characterized by the large number of Chinese-owned ] restaurants (''chop suey'' itself is a Chinese American concoction and therefore it is not considered authentic Chinese cuisine), laundry businesses, and ]s, until around the mid-20th century when most of these businesses began to disappear; though some remain, they are generally seen as anachronisms. In early years of Chinatowns, the opium dens were patronized as a relaxation and to escape the harsh and brutal realities of a non-Chinese society (it was the profiteering British who had introduced opium to China during the Qing Dynasty). These businesses no longer exist in many Chinatowns and they have been replaced by Chinese grocery stores, more authentic Chinese restaurants, and other establishments. | |||

| ==Chinese settlements== | |||

| ===Restaurants=== | |||

| ===History=== | |||

| Chinatowns worldwide are usually popular destinations for various ethnic Chinese and increasingly, other Asian cuisines such as Vietnamese, Thai, and ]n. Chinatown restaurants serve many Chinatowns both as a major economic component and social gathering places. Many adjacent tourist-centric businesses rely on restaurants to bring in the customers, both of Chinese descent and non-Chinese. In the Chinatowns in the western countries, restaurant work may be the only type of employment available for poorer immigrants, especially those who cannot converse fluently in the language of the adopted country. Most Chinatowns generally have a range of authentic and touristy restaurants. | |||

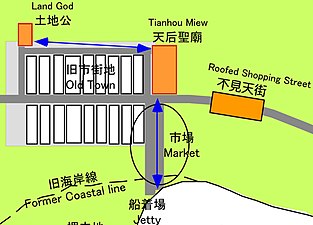

| *People of ] province used to move over the ] from the 14th century to look for more stable jobs, in most cases of trading and fishery, and settled down near the port/jetty under approval of the local authority such as ] (]), ] (]), ] (]), ] (]), ], ], ] (]), ] (the ]), etc. A large number of this kind of settlements was developed along the coastal areal of the ], and was called "Campon China" by Portuguese account<ref>1613 Description of Malaca and Meridional India and Cathay composed by Emanuel Godinho de Eradia.</ref> and "China Town" by English account.<ref>"We firſt paſſed the lower ground, from thence round the Horſe Stable Hill, to the Hermitage, and ſo by the China Town and brick-ſhades," Modern Hiſtory: Bing a Continuation of the Universal History, Book XIV, Chap. VI. Hiſtory of the Engliſh Eaſt India Company, 1759.</ref> | |||

| ===Settlement pattern=== | |||

| San Francisco's Chinatown retains many historic restaurants, including those established from the 1910s to the 1950s, although some that lasted for generations have shuttered in recent years and others have modernized their menus. Many Chinatown eateries from that era specialized in ] (or, depending on where they were located, Chinese Canadian cuisine, Chinese Cuban cuisine, etc.), especially chop suey and chow mein. They often used gaudy neon lighting to attract non-Chinese customers and often featured English-language signs with stereotypically "Chinese" writing, large red doors, Chinese paper lanterns, and ] placemats (perhaps the most enduring of these stereotypical features). Outside Chinatowns, such faux Chinese restaurants are also found in many areas without a significant Chinese-speaking population. | |||

| *The settlement was developed along a jetty and protected by ] temple, which was dedicated for the Goddess of Sea for safe sailing. Market place was open in front of ] temple, and ] were built along the street leading from west side of the ] temple. At the end of the street, ] (Land God) temple was placed. As the settlement prospered as commercial town, ] temple would be added for commercial success, especially by people from Hong Kong and Guangdong province. This core pattern was maintained even the settlement got expanded as a city, and forms historical urban center of the Southeast Asia.<ref>Hideo Izumida, Chinese Settlements and China-towns along Coastal Area of the South China Sea: Asian Urbanization Through Immigration and Colonization, 2006, {{ISBN|4-7615-2383-2}}(Japanese version), {{ISBN|978-89-5933-712-5}}(Korean version)</ref> | |||

| <gallery mode="packed" heights="150px"> | |||

| File:Hoian-settlement-pattern.jpg|Hoian Settlement Pattern, Vietnam, 1991 | |||

| File:Pengchau-settlement-pattern.jpg|Pengchau Settlement Pattern, Hong Kong, 1991 | |||

| File:Penang-Settlement-pattern.jpg|Chinese Settlement in Georgetown, Malaysia, 1991 | |||

| File:Kucing-settlement-pattern.jpg|Chinese Settlement in Kuching, Malaysia, 1991 | |||

| File:Kucing-Tinhua1991.jpg|Tin Hau (Goddess of Sea) Temple in Kuching, Malaysia, 1991 | |||

| File:Kucing-Todigong1991.jpg|] at Kuching, 1991 | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ==Characteristics== | |||

| Generally speaking, restaurants serving authentic Chinese food to primarily to immigrant customers have never conformed to these Chinatown stereotypes as much as those aimed at non-Chinese tourists (although some banquet-oriented restaurants do use some of the same features). Because of new ethnic Chinese immigration and the expanded palate of many contemporary cultures, the remaining Chinese American (etc.) restaurants are widely seen as anachronisms. In many Chinatowns, there are now many large, authentic Cantonese seafood restaurants (with egg or spring rolls only served during ] hours), restaurants specializing in other forms of Chinese food (Hakka, Szechuan, etc.), and small restaurants with delis. | |||

| The features described below are characteristic of many modern Chinatowns. | |||

| ===Demographics=== | |||

| Cantonese seafood restaurants (Cantonese: ''hoy seen jow ga'') typically use a large dining room layout, have ornate designs, and specialize in seafood such as expensive Chinese-style ]s, ]s, ]s, ]s, and ]s, all kept live in tanks until preparation. They also offer the delicacy of ]. Some seafood restaurants may also offer dim sum in the morning through the early afternoon hours. These restaurants are also used for weddings, banquets, and other special events. Owing to their higher prices, they tend to be more common in Chinatowns in developed countries and in affluent Chinese immigrant communities, notably in Australia, Canada, and the United States. There are generally fewer of them in the older Chinatowns; for example, they are practically non-existent in ]'s Chinatown, but more are found in its suburbs such as ]. Competition between these restaurants is often fierce. Hence, owners of seafood restaurants hire and even "steal" well-rounded chefs, many of whom are from ]. | |||

| The early Chinatowns such as those in ] and ] in the United States were naturally destinations for people of Chinese descent as ] were the result of opportunities such as the California Gold Rush and the Transcontinental Railroad drawing the population in, creating natural Chinese enclaves that were almost always 100% exclusively Han Chinese, which included both people born in China and in the enclave, in this case ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sf-planning.org/ftp/general_plan/Chinatown.htm#CHI_HOS_4_1 |title=Chinatown Area Plan (San Francisco Chinatown) |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140519123247/http://www.sf-planning.org/ftp/general_plan/Chinatown.htm |archive-date=2014-05-19 }}</ref> In some free countries such as the United States and Canada, housing laws that prevent ] also allows neighborhoods that may have been characterized as "All Chinese" to also allow non-Chinese to reside in these communities. For example, the Chinatown in ] has a sizeable non-Chinese population residing within the community.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.city-data.com/neighborhood/Chinatown-Philadelphia-PA.html|title=Chinatown Philadelphia PA|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140702164650/http://www.city-data.com/neighborhood/Chinatown-Philadelphia-PA.html|archive-date=2014-07-02}}</ref> | |||

| A recent study also suggests that the demographic change is also driven by ] of what were previously Chinatown neighborhoods. The influx of ] is speeding up the gentrification of such neighborhoods. The trend for emergence of these types of natural enclaves is on the decline (with the exceptions being the continued growth and emergence of newer Chinatowns in ] and ] in New York City), only to be replaced by newer "Disneyland-like" attractions, such as a new Chinatown that will be built in the ] region of ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ibtimes.com/china-city-america-new-disney-chinese-themed-development-plans-bring-6-billion-catskills-new-York|title=China City Of America: New Disney-Like Chinese-Themed Development Plans To Bring $6 Billion To Catskills In New York State|website=]|date=6 December 2013|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140307120550/http://www.ibtimes.com/china-city-america-new-disney-chinese-themed-development-plans-bring-6-billion-catskills-new-york|archive-date=2014-03-07}}</ref> This includes the endangerment of existing historical Chinatowns that will eventually stop serving the needs of Chinese immigrants. | |||

| Also, Chinese barbecue deli restaurants, called ''siu lop'' in Cantonese, are generally low-key and serve less expensive fare such as won ton noodles (or ''won ton mein''), chow fun, and rice porridge or ''jook'' in Cantonese Chinese. They also tend to have displays of whole pre-cooked roasted ducks and pigs hanging on their windows, a common feature in most Chinatowns worldwide. These delis also serve barbecue pork (''cha sui''), chicken feet and other Chinese-style items less welcome to the typical Western palate. Food is usually intended for take-out (British: takeaway). Some of these Chinatown restaurants sometimes have the reputation of being "]s". Nonetheless, with their low prices, they are still generally patronized by hungry Chinese and other ethnic customers on a budget. One of the more older and better-known of these is the multi-story Sam Wo Restaurant, on Washington Street and Grant Avenue in San Francisco's Chinatown. | |||

| Newer developments like those in ], and the ], which are not necessarily considered "Chinatowns" in the sense that they do not necessarily contain the Chinese architectures or Chinese language signs as signatures of an officially sanctioned area that was designated either in law or signage stating so, differentiate areas that are called "Chinatowns" versus locations that have "significant" populations of people of Chinese descent. For example, ] in the United States has 63,434 people (2010 U.S. Census) of Chinese descent, and yet "does not have a ]". Some "official" Chinatowns have Chinese populations much lower than that.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.census.gov/ |title=U.S. Census website |access-date=2020-04-04 |archive-date=December 27, 1996 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/19961227012639/https://www.census.gov/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Some small Chinese restaurants in Chinatowns may offer both Chinese American cuisine — for Western customers — and authentic Chinese cuisine for Chinese-speaking customers. According to an interview of Chinese cuisine culinary chef Martin Yan (host of the television program ''Martin Yan's Chinatown''), more and more non-Chinese are becoming acquainted with authentic cuisine. | |||

| ===Town-Scape=== | |||

| In integrating with the larger population, Chinese cuisine has evolved. To adapt to local tastes, the best Chinese Mexican-style Cantonese cuisine is said to be found in Mexicali's Chinatown (or La Chinesca in its local Spanish) or the Chinese Peruvian cuisine in the Barrio Chino of Lima. | |||

| {{Main|Chinese architecture}} | |||

| Many tourist-destination metropolitan Chinatowns can be distinguished by large red arch entrance structures known in Mandarin Chinese as '']'' (sometimes accompanied by ] statues on either side of the structure, to greet visitors). Other Chinese architectural styles such as the Chinese Garden of Friendship in ] and the ] at the gate to the ] Chinatown are present in some Chinatowns. ], the Chinatown in ], contains many buildings that were constructed in the Chinese architectural style. | |||

| Paifangs usually have special inscriptions in Chinese. Historically, these gateways were donated to a particular city as a gift from the ] and ], or local governments (such as Chinatown, San Francisco) and business organizations. The long-neglected Chinatown in ], ], received materials for its paifang from the People's Republic of China as part of the Chinatown's gradual renaissance. Construction of these red arches is often financed by local financial contributions from the Chinatown community. Some of these structures span an entire intersection, and some are smaller in height and width. Some paifang can be made of ], ] or ] and may incorporate an elaborate or simple design. | |||

| Vietnamese immigrants, both ethnic Chinese and non-Chinese, have opened restaurants in many Chinatowns, serving Vietnamese ] beef noodle soups and Franco-Vietnamese sandwiches. Some immigrants have also started restaurants serving Teochew Chinese cuisine. Some Chinatowns old and new may also contain several pan-Asian restaurants offering a variety of Asian noodles under one roof. | |||

| {{Gallery |align=center |title=Chinatown landmarks | |||

| ===Shops=== | |||

| |File:The Sydney Chinatown (16261772672).jpg|Entrance to ] | |||

| Most Chinatown businesses are actively engaged in the import-export and wholesale businesses; hence, a large number of Trading Companies are found in Chinatown. | |||

| |File:China Gate, Philadelphia.jpg|Paifang in ] | |||

| |File:Chinatown, DC gate.jpg|] in the ] of ] | |||

| |File:Nochi.jpg|Paifang in ], ] | |||

| |File:Paifang Boston Chinatown 1.jpg|] looking towards the paifang | |||

| |File:ChinatownGatePortland.jpg|Gate of Chinatown, ], ] | |||

| |File:Chinatown Arch Newcastle UK.jpg|Chinatown entry arch in ], England | |||

| |File:Chinese Garden of Friendship.jpg|Chinese Garden of Friendship, part of ] | |||

| |File:Chinatown Victoria gate lion hires.jpg|] at the Chinatown gate in ], Canada | |||

| |File:Chinatown Gate 1 Compressed.jpg|Harbin Gates in Chinatown of ], Canada | |||

| |File:Chinatown Vancouver.JPG|Millennium Gate on Pender Street in Chinatown of ], Canada | |||

| |File:ChineseCulturalCentre.JPG|The ] in the ], Canada ] | |||

| |File:Toong_on_Church_-_Black_Burn_Lane_-_Kolkata_2013-03-03_5248.JPG|Chinese Temple "Toong On Church" in ], India. | |||

| |File:Yokohama Chinatown temple.jpg|Chinese Temple in ], Japan. | |||

| |Filipino-Chinese Friendship Arch at Binondo.jpg|Filipino-Chinese Friendship Arch in ]}} | |||

| ==Benevolent and business associations== | |||

| Small ] and herb shops are common in most Chinatowns. | |||

| {{Main|Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| A major component of many Chinatowns is the family benevolent association, which provides some degree of aid to immigrants. These associations generally provide social support, religious services, death benefits (members' names in Chinese are generally enshrined on tablets and posted on walls), meals, and recreational activities for ethnic Chinese, especially for older Chinese migrants. Membership in these associations can be based on members sharing a common ] or belonging to a common clan, spoken ], specific village, region or country of origin, and so on. Many have their own facilities. | |||

| As with the aforementioned Chinatown Chinese restaurant trade, grocery stores and seafood markets serve an essential function in typical Chinatown economies, and these stores sell the much-needed ingredients to such restaurants. Chinatown grocers and markets are often characterized by sidewalk vegetable and fruit stalls – a quintessential image of Chinatowns – and also sell a variety of grocery items imported from East Asia (chiefly Mainland China, ], Japan, and South Korea) and Southeast Asia (principally Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia). For example, most Chinatown markets stock items such as sacks of Thai ], Mainland Chinese ] and ] ]s, bottles of ], rice ], Hong Kong ] beverages, Malaysian snack items, Taiwanese ]s, and Japanese ] and Chinese specialties such as black ]s (often used in rice porridge), '']'' and ]s. These markets may also sell fish (especially ]) and other seafood items, which are kept alive and well in aquariums, for Chinese and other Asian cuisine dishes. Until recently, these items generally could not be found outside of the Chinatown enclaves, although since the 1970s ]s have proliferated in the suburbs of North America and Australia, competing strongly with the old Chinatown markets. | |||

| Some examples include San Francisco's prominent ] (中華總會館 ''Zhōnghuá Zǒng Huìguǎn''), aka ] and Los Angeles' Southern California Teochew Association. The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association is among the largest umbrella groups of benevolent associations in the North America, which branches in several Chinatowns. Politically, the CCBA has traditionally been aligned with the ] and the ]. | |||

| In keeping with ] funeral traditions, Chinese specialty shops also sell a variety of funeral items which provide material comfort in the afterlife of the deceased. Shops typically sell specially-crafted replicas of small paper houses, paper radios, paper televisions, paper telephones, paper jewelry, and other material items. They also sell "hell money" currency notes. These items are intended to be burned in a furnace. | |||

| The London Chinatown Chinese Association is active in ]. ] has an institution in the ''Association des Résidents en France d'origine indochinoise'' and it servicing overseas Chinese immigrants in Paris who were born in the former ]. | |||

| Chinatowns also typically contain small businesses that sell imported ] and ]s of Chinese-language films and ]. VCD is a format that has not caught on in Western countries, but are sold in ethnic Chinese shops. These VCDs are mainly titles of Hong Kong and Mainland Chinese films, while there are also VCDs of Japanese ]. | |||

| Traditionally, Chinatown-based associations have also been aligned with ethnic Chinese business interests, such as restaurant, grocery, and laundry (antiquated) associations in Chinatowns in North America. In Chicago's Chinatown, the On Leong Merchants Association was active. | |||

| ===Benevolent associations=== | |||

| A major component of many old Chinatowns worldwide is the family benevolent association. These associations generally provide social support, religious services, death benefits (members' names in Chinese are generally enshrined on tablets and posted on walls), meals, and recreational activities for ethnic Chinese, especially for older Chinese migrants. Membership in these associations can be based on members sharing a common Chinese surname, spoken Chinese dialect, specific region or country of origin, and so on. Many of these associations have their own facilities. Some examples include San Francisco's prominent ] and Los Angeles's Southern California Teochew Association. The ] is among the largest umbrella groups of benevolent associations in the North America; ], France has a similar institution in the ''Association des Résidents en France d'origine indochinoise''. | |||

| ==Names== | |||

| ===Annual events in Chinatown=== | |||

| Most Chinatowns the world over present ] (or also known as ]) festivities with ubiquitous dragon and lion dances accompanied by the clashing of ]s and by ear-splittingly loud Chinese ]s, set off especially in front of ethnic Chinese storefronts, where the "dragon" attempts to reach for a ] or catch an ]. Storekeepers usually donate some money to the performers. In addition, some streets of Chinatowns are usually closed off for ]s, Chinese ]s and ]s demonstrations, ]s, and ]s – this is dependent on the promoters or organizers of the events. Other festivals may also be held in a ]/], local ], or ] grounds within Chinatown. These events are popular with the local ethnic community and also to non-Chinese gawkers. | |||

| ===English=== | |||

| Some Chinatowns hold an annual "]" ], such as "Miss Chinatown San Francisco," "Miss Chinatown Hawaii," or Miss Chinatown Houston" (just to name a few examples). | |||

| ] pointing towards "]"]] | |||

| Although the term "Chinatown" was first used in Asia, it is not derived from a Chinese language. Its earliest appearance seems to have been in connection with the ] of ], which by 1844 was already being called "China Town" or "Chinatown" by the British colonial government.<ref>{{cite journal|journal=Simmond's Colonial Magazine and Foreign Miscellany|date=Jan–Apr 1844|page=335|url=http://www.nla.gov.au/ferg/issn/14606011.html|title=Trade and Commerce in Singapore|access-date=2011-12-20|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111222220928/http://www.nla.gov.au/ferg/issn/14606011.html|archive-date=2011-12-22}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|newspaper=Sydney Morning Herald|date=1844-07-23|page= 2}}</ref> This may have been a word-for-word translation into English of the Malay name for that quarter, which in those days was probably "Kampong China" or possibly "Kota China" or "Kampong Tionghua/Chunghwa/Zhonghua". | |||

| The first appearance of a Chinatown outside Singapore may have been in 1852, in a book by the Rev. Hatfield, who applied the term to the Chinese part of the main settlement on the remote South Atlantic island of ].<ref>{{cite book|last=Hatfield|first=Edwin F.|title=St. Helena and the Cape of Good Hope|url=https://archive.org/details/sthelenacapeofgo01hatf|year=1852|page=}}</ref> The island was a regular way-station on the voyage to Europe and North America from Indian Ocean ports, including Singapore. | |||

| ===Dragon and lion dances=== | |||

| ]'s Chinatown perform ]s for good luck.]] | |||

| ] in ] pointing to "]"]] | |||

| ] and ]s are performed in Chinatown every Chinese New Year. They are also performed to celebrate a grand opening of a new Chinatown business, such as a restaurant or bank. In Chinatowns of Western countries, the performers of dragon and lion dances in Chinatown are not necessarily all ethnic Chinese. | |||

| One of the earliest American usages dates to 1855, when San Francisco newspaper '']'' described a "pitched battle on the streets of Chinatown".<ref>{{cite news|newspaper=Alta California|date=1855-12-12|page= 1}}</ref> Other ''Alta'' articles from the late 1850s make it clear that areas called "Chinatown" existed at that time in several other California cities, including Oroville and San Andres.<ref>{{cite news|newspaper=Alta California|date=1857-12-12|page= 1}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|newspaper=Alta California|date=1858-06-04|page= 2}}</ref> By 1869, "Chinatown had acquired its full modern meaning all over the U.S. and Canada. For instance, an Ohio newspaper wrote: "From San Diego to Sitka..., every town and hamlet has its 'Chinatown'."<ref>{{cite news|newspaper=Defiance Democrat|date=1869-06-12|page= 5}}</ref> | |||

| In British publications before the 1890s, "Chinatown" appeared mainly in connection with California. At first, Australian and New Zealand journalists also regarded Chinatowns as Californian phenomena. However, they began using the term to denote local Chinese communities as early as 1861 in Australia<ref>{{cite news|newspaper=Ballarat Star|date=1861-02-16|page= 2}}</ref> and 1873 in New Zealand.<ref>{{cite news|newspaper=Tuapeka Times|date=1873-02-06|page= 4}}</ref> In most other countries, the custom of calling local Chinese communities "Chinatowns" is not older than the twentieth century. | |||

| Ceremonial ]s are also usually placed in front of new Chinatown businesses by well-wishers, to assure future success. | |||

| Several alternate English names for Chinatown include '''China Town''' (generally used in ] and ]), '''The Chinese District''', '''Chinese Quarter''' and ''']''' (an antiquated term used primarily in several ] towns in the ] for a Chinese community; some of these are now historical sites). In the case of Lillooet, British Columbia, Canada, China Alley was a parallel commercial street adjacent to the town's Main Street, enjoying a view over the river valley adjacent and also over the main residential part of Chinatown, which was largely of ] construction. All traces of Chinatown and China Alley there have disappeared, despite a once large and prosperous community. | |||

| ===Politics=== | |||

| The ] of the ] has established many local offices in Chinatowns all over the world, in order to gain support from ] in its ongoing cold war with the ]. | |||

| ===In Chinese=== | |||

| ==Social problems in Chinatown== | |||

| ], with {{lang|zh|唐人街}} below the street name]] | |||

| ''Main Article: ]'' | |||

| In ], Chinatown is usually called {{lang|zh|唐人街}}, in ] ''Tong jan gai'', in ] ''Tángrénjiē'', in ] ''Tong ngin gai'', and in ] ''Hong ngin gai'', literally meaning "Tang people's street(s)". The ] was a zenith of the Chinese civilization, after which some Chinese call themselves. Some Chinatowns are indeed just one single street, such as the relatively short ] in ], ], Canada. | |||

| A more modern Chinese name is {{lang|zh|華埠}} (Cantonese: Waa Fau, Mandarin: Huábù) meaning "Chinese City", used in the semi-official Chinese translations of some cities' documents and signs. ''Bù'', pronounced sometimes in Mandarin as ''fù'', usually means ''seaport''; but in this sense, it means ''city'' or ''town''. ''Tong jan fau'' ({{lang|zh|唐人埠}} "Tang people's town") is also used in Cantonese nowadays. The literal word-for-word translation of ''Chinatown''—''Zhōngguó Chéng'' ({{lang|zh|中國城}}) is also used, but more frequently by visiting Chinese nationals rather than immigrants of Chinese descent who live in various Chinatowns. | |||

| Overcoming an earlier reputation of being dirty slums, Chinatowns currently enjoy the rewards of attracting tourists with Asian cuisine and culture. However the economic success brings with it Asian ] with rival gangs competing for new lucrative opportunities in ], ], ], ] and ]. This has led to high profile shoot-outs where innocent bystanders and police have been killed. Although some Chinatowns have experienced recent growth and success many others are facing the difficult challenges of decay and abandonment. Leading some to fear redevelopment initiatives will erase struggling Chinatowns completely. In ], along with these ongoing social problems, ] hit ]s' and ]s' core tourist businesses the hardest, as tourists and local residents became reluctant to risk infection by returning Chinese travelers. | |||

| Chinatowns in Southeast Asia have unique Chinese names used by the local Chinese, as there are large populations of people who are ], living within the various major cities of Southeast Asia. As the population of Overseas Chinese, is widely dispersed in various enclaves, across each major Southeast Asian city, specific Chinese names are used instead. | |||

| ==Chinatowns worldwide== | |||

| {{chinatown}} | |||

| Chinatowns are most common in ], ], ] and ], but are common across the globe. Immigration patterns determine the economic, political and social character of individual Chinatowns, as do their intranational locations (urban, suburban or rural). Most Chinatowns grow organically but some countries have taken to building and promoting Chinatowns within their bigger cities. | |||

| For example, in ], where 2.8 million ethnic Chinese constitute a majority 74% of the resident population,<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://www.singstat.gov.sg/-/media/files/publications/cop2010/census_2010_release1/cop2010sr1.pdf|title=Singapore Census of Population 2010, Statistical Release 1: Demographic Characteristics, Education, Language and Religion|last=Singapore|first=Department of Statistics|publisher=Ministry of Trade & Industry, Republic of Singapore|year=2011|isbn=9789810878085|location=Singapore|pages=19|access-date=2019-12-29|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200213154440/https://www.singstat.gov.sg/-/media/files/publications/cop2010/census_2010_release1/cop2010sr1.pdf|archive-date=2020-02-13|url-status=dead}}</ref> the Chinese name for ] is ''Niúchēshǔi'' ({{lang|zh|牛車水}}, ] ]: ''Gû-chia-chúi''), which literally means "ox-cart water" from the Malay 'Kreta Ayer' in reference to the water carts that used to ply the area. The Chinatown in ], ], (where 2 million ethnic Chinese comprise 30% of the population of ]<ref>Department of Statistics, Malaysia. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200206052225/https://www.mycensus.gov.my/banci/www/index.php |date=2020-02-06 }}, '']'', Malaysia, August 2014. Retrieved on 27 December 2019.</ref>) while officially known as ] (Malay: ''Jalan Petaling''), is referred to by Malaysian Chinese by its Cantonese name ''ci<sup>4</sup> cong<sup>2</sup> gaai<sup>1</sup>'' ({{lang|zh-hant|茨廠街}}, pinyin: ''Cíchǎng Jiē''), literally "tapioca factory street", after a ] starch factory that once stood in the area. In ], ], the area is called Mínlúnluò Qū {{lang|zh-hant|岷倫洛區}}, literally meaning the "Mín and Luò Rivers confluence district" but is actually a ] of the local term ''Binondo'' and an allusion to its proximity to the ]. | |||

| ''See also: ]'' | |||

| ===Other languages=== | |||

| ==Chinatown in film, television, and the arts== | |||

| In ], the term used for Chinatown districts is ''''']''''', the etymology of which is uncertain.<ref name="pacs.ph"/> In the rest of the ], the Spanish-language term is usually '''''barrio chino''''' (''Chinese neighborhood''; plural: ''barrios chinos''), used in Spain and ]. (However, ''barrio chino'' or its ] cognate ''barri xinès'' do not always refer to a Chinese neighborhood: these are also common terms for a disreputable district with drugs and prostitution, and often no connection to the Chinese.). | |||

| In Portuguese, Chinatown is often referred to as '''Bairro chinês''' (''the Chinese Neighbourhood''; plural: ''bairros chineses''). | |||

| *'']'' (1986), movie, San Francisco, ], ] | |||

| *'']'' (1990), movie, Victoria Chinatown, ], ] | |||

| *'']'' (1982), movie, Los Angeles Chinatown of 2019, ], ] | |||

| *'']'' (1974), movie, Los Angeles, ], ] | |||

| *'']'' (1993), movie, ] | |||

| *'']'', video game, San Francisco Chinatown | |||

| *'']'', musical, San Francisco | |||

| *'']'', movie, Manhattan | |||

| *'']'' (1994), movie, San Francisco, ] and ] | |||

| *'']'' (1978), TV series, "A Death in the Family" episode. ] Chinatown | |||

| *'']'' (1996), movie, ] (Australia) Chinatown, ] | |||

| *'']'' (1995), movie, San Francisco, with ], ] | |||

| *'']'' (1988), novel by Amy Tan; (1992), movie | |||

| *'']'' (2002), movie, Vancouver | |||

| *'']'' (1997), movie, ] (Australia) Chinatown, Jackie Chan | |||

| *'']'' (1939), movie, ] | |||

| *'']'' (1940), Boris Karloff | |||

| * '']'' (2000), independent movie, Los Angeles Chinatown | |||

| * '']'' (1980), educational series, "Liang & the Magic Paintbrush" episode. Manhattan Chinatown. | |||

| *'']'' (2000), movie, Vancouver Chinatown, Jet Li and ] | |||

| *'']'' (1998), movie, ] Chinatown, Jackie Chan and ] | |||

| *'']'' (1999), movie, set in ] Chinatown but filmed in ] Chinatown, ] and ] | |||

| *'']'' (1997), movie, San Francisco, ] and ] | |||

| *'']'' (1996), TV series, "Hell Money" episode. Filmed in ] Chinatown, set in San Francisco but appears less hilly! | |||

| * '']'' (1981), TV series, "East Winds" episode. | |||

| *'']'' (2000), TV documentary, ] | |||

| *'']'' (1997), movie, ], motorcycle chase scene supposedly set in ]'s ''Cholon'' district (]) but actually filmed in ]'s ''Yaowarat'' (]). | |||

| *'']'' (1985), movie, Manhattan Chinatown, ]. | |||

| *'']'' (2004), TV Series, one episode set in Manhattan Chinatown dealing with the issue of immigrant smuggling. | |||

| * '']'' (2002-2004), TV cooking show on Food Network Canada, shows multiple worldwide Chinatowns and their various Chinese cuisine | |||

| * '']'' (1996), movie, John Lovitz, Los Angeles Chinatown | |||

| * '']'' (1999), movie, ] and ], a scene filmed in Chinatown of Malacca, Malaysia | |||

| In ] regions (such as France and ]), Chinatown is often referred to as '''''le quartier chinois''''' (''the Chinese Neighbourhood''; plural: ''les quartiers chinois''). The most prominent Francophone Chinatowns are located in ] and ]. | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| * ] | |||

| *] | |||

| The Vietnamese term for Chinatown is ''Khu người Hoa'' (Chinese district) or ''phố Tàu'' (Chinese street). Vietnamese language is prevalent in Chinatowns of Paris, Los Angeles, Boston, Philadelphia, Toronto, and Montreal as ethnic Chinese from Vietnam have set up shop in them. | |||