| Revision as of 09:49, 8 December 2021 editCote d'Azur (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users137,910 edits →Society← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 18:17, 18 December 2024 edit undoRemoveRedSky (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Rollbackers1,397 edits Reverting edit(s) by 80.0.36.251 (talk) to rev. 1263575069 by Godofincompetence: Vandalism (RW 16.1)Tags: RW Undo | ||

| (725 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Roman |

{{Short description|Roman civilisation from the 8th century BC to the 5th century AD}} | ||

| {{About|the |

{{About|the history of Roman civilisation in antiquity|the history of the city of Rome|History of Rome|other uses|}} | ||

| {{EngvarB|date=October 2022}} | |||

| {{pp|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2022}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=December 2019}} | |||

| {{Infobox former country | {{Infobox former country | ||

| |native_name = ''Roma'' | | native_name = ''Roma'' | ||

| | |

| common_name = Ancient Rome | ||

| | capital = ] (and others during the late Empire, notably ] and ]) | |||

| |common_name = Ancient Rome | |||

| | common_languages = ] | |||

| |capital = ] (and others during the late Empire, notably ] and ]) | |||

| | |

| era = ] | ||

| | government_type = *Elective ] {{Small|(753–509 BC)}} | |||

| |era = ] | |||

| *] diarchic ] {{Small|(509 BC–476 AD, only ''de jure'' after 27 BC)}} | |||

| |government_type = ] (753–509 BC)<br />] (509–27 BC)<br />] (27 BC–476 AD) | |||

| *absolute monarchy {{Small|(27 BC–476 AD, ''de facto'')}} | |||

| |year_start = 753 BC | |||

| | footnote1 = {{Note|lifespan||While the deposition of Emperor ] in 476 is the most commonly cited end date for the Western Roman Empire, the last Western Roman emperor ], was assassinated in 480, when the title and notion of a separate Western Empire were abolished. Another suggested end date is the reorganization of the Italian peninsula and abolition of separate Western Roman administrative institutions under Emperor ] during the latter half of the 6th century.}} | |||

| |year_end = 476 AD | |||

| | status = {{Ubl|]<br/> {{Small|(753–509 BC)}}|]<br /> {{Small|(509–27 BC)}}|]<br /> {{Small|(27 BC–476 AD)}}}} | |||

| |event_start = ] | |||

| | year_start = 753 BC | |||

| |event1 = ] of ] | |||

| | |

| year_end = 476/480{{Ref|lifespan|1}} AD | ||

| | |

| event_start = ] | ||

| | event1 = ] of ] | |||

| |date_event2 = 27 BC | |||

| | date_event1 = 509 BC | |||

| |event_end = ] | |||

| | |

| event2 = Octavian proclaimed ] | ||

| | date_event2 = 27 BC | |||

| |symbol_type = {{lang|la|]}} | |||

| | |

| event_end = ] | ||

| | national_motto = {{Lang|la|]}} | |||

| |image_map_caption = Territories of the Roman civilization: | |||

| | image_map = Roman Republic Empire map.gif | |||

| | image_map_caption = Territories of the Roman civilisation: | |||

| {{Legend|#a64|]}} | {{Legend|#a64|]}} | ||

| {{Legend|#a6a|]}} | {{Legend|#a6a|]}} | ||

| Line 29: | Line 30: | ||

| {{Legend|#bc4|]}} | {{Legend|#bc4|]}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Roman government}} | |||

| In modern ], '''ancient Rome''' |

In modern ], '''ancient Rome''' is the ] civilisation from the founding of the Italian city of ] in the 8th century BC to the ] of the ] in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the ] (753–509 BC), the ] (509–27 BC), and the ] (27 BC–476 AD) until the fall of the western empire.<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |title=ancient Rome {{!}} Facts, Maps, & History |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/place/ancient-Rome |access-date=5 September 2017 |language=en}}</ref>{{Efn|The specific dates vary, depending on whether one follows Roman tradition, modern archaeology, or competing views of which particular events mark endpoints.}} | ||

| Ancient Rome began as an ] settlement, traditionally dated to 753 BC, |

Ancient Rome began as an ] settlement, traditionally dated to 753 BC, beside the ] in the ]. The settlement grew into the city and polity of Rome, and came to control its neighbours through a combination of treaties and military strength. It eventually controlled the Italian Peninsula, assimilating the ] culture of southern ] (]) and the ] culture, and then became the dominant power in the Mediterranean region and parts of Europe. At its height it controlled the ] coast, ], Southern Europe, and most of Western Europe, the ], ], and much of the Middle East, including ], ], and parts of ] and ]. That empire was among the ] in the ancient world, covering around {{Convert|5|e6km2|e6sqmi|abbr=off}} in AD 117,<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal |last=Taagepera |first=Rein |author-link=Rein Taagepera |year=1979 |title=Size and Duration of Empires: Growth-Decline Curves, 600 B.C. to 600 A.D. |journal=Social Science History |volume=3 |issue=3/4 |pages=125 |doi=10.2307/1170959 |jstor=1170959 |issn = 0145-5532 }}<br />{{Cite journal|last1=Turchin|first1=Peter|last2=Adams|first2=Jonathan M.|last3=Hall|first3=Thomas D|date=December 2006 |title=East-West Orientation of Historical Empires |journal=Journal of World-Systems Research |volume=12 |issue=2 |page=222 |issn=1076-156X |doi=10.5195/JWSR.2006.369|doi-access=free}}</ref> with an estimated 50 to 90 million inhabitants, roughly 20% of the world's population at the time.{{Efn|There are several different estimates for the population of the Roman Empire. | ||

| * Scheidel |

* {{Harvnb|Scheidel|Saller|Morris|2007|p=2}} estimates 60 million. | ||

| * {{Cite journal |last=Goldsmith |first=Raymond W. |date=September 1984 |title=An Estimate of the Size And Structure of the National Product of the Early Roman Empire |journal=Review of Income and Wealth |volume=30 |issue=3 |doi=10.1111/j.1475-4991.1984.tb00552.x |page=263 |ref=none}} estimates 55. | |||

| * Goldsmith (1984, p. 263) estimates 55. | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Beloch |first=Karl Julius |title=Bevölkerung der griechisch-römischen Welt |language=de |date=1886 |publisher=Duncker |page=507 |ref=none}} estimates 54. | |||

| * Beloch (1886, p. 507) estimates 54. | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Maddison |first=Angus |title=Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030 AD. Essays in Macro-Economic History |date=2007 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-1992-2721-1 |author-link=Angus Maddison |ref=none |pages=51, 120}} estimates 48. | |||

| * Maddison (2006, pp. 51, 120) estimates 48. | |||

| * estimates 65 (while mentioning several other estimates between 55 and 120). | * estimates 65 (while mentioning several other estimates between 55 and 120). | ||

| * {{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xvcAhdF-VlgC&pg=PA3|title=Marcus Aurelius: Warrior, Philosopher, Emperor |

* {{Cite book |last=McLynn |first=Frank |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xvcAhdF-VlgC&pg=PA3 |title=Marcus Aurelius: Warrior, Philosopher, Emperor |date=2011 |publisher=Random House |isbn=978-1-4464-4933-2 |page=3 |language=en |quote=he most likely estimate for the reign of Marcus Aurelius is somewhere between seventy and eighty million. |ref=none}} | ||

| * {{Cite book |last1=McEvedy |first1=Colin |last2=Jones |first2=Richard |title=Atlas of world population history |publisher=Penguin |location=New York |date=1978 |isbn=0-1405-1076-1 |ol=4292284M |oclc=4150954 |ref=none}} | |||

| * McEvedy and Jones (1978). | |||

| * an average of figures from different sources as listed at the US Census Bureau's {{ |

* an average of figures from different sources as listed at the US Census Bureau's {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131013110506/http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/worldhis.html |date=13 October 2013}} | ||

| * ] (1993). "Population Growth and Technological Change: One Million B.C. to 1990" in ''The Quarterly Journal of Economics'' 108(3): 681–716. | * ] (1993). "Population Growth and Technological Change: One Million B.C. to 1990" in ''The Quarterly Journal of Economics'' 108(3): 681–716.}} The Roman state evolved from an elective monarchy to a ] and then to an increasingly ] ] during the Empire. | ||

| </ref><ref name=":0">* {{cite journal|last=Taagepera|first=Rein|author-link=Rein Taagepera|year=1979|title=Size and Duration of Empires: Growth-Decline Curves, 600 B.C. to 600 A.D.|journal=Social Science History|volume=3|issue=3/4|pages=125|doi=10.2307/1170959|jstor=1170959}} | |||

| * {{cite journal|last1=Turchin|first1=Peter|last2=Adams|first2=Jonathan M.|last3=Hall|first3=Thomas D|date=December 2006|title=East-West Orientation of Historical Empires|journal=Journal of World-Systems Research|volume=12|issue=2|page=222|issn=1076-156X|doi=10.5195/JWSR.2006.369|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| Ancient Rome is often grouped into ] together with ], and their similar cultures and societies are known as the ]. Ancient Roman civilisation has contributed to modern language, religion, society, technology, law, politics, government, warfare, art, literature, architecture, and engineering. Rome professionalised and expanded its military and created a system of government called ''{{Lang|la|]}}'', the inspiration for modern republics such as the ] and ].<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bGxiE6jvzOcC |title=A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution |date=1989 |publisher=Harvard University Press |isbn=978-0-6741-7728-4 |editor-last=Furet |editor-first=François |page=793 |editor-last2=Ozouf |editor-first2=Mona}}; {{Cite book |last1=Luckham |first1=Robin |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RMDnAAAAIAAJ |title=Democratization in the South: The Jagged Wave |last2=White |first2=Gordon |date=1996 |publisher=Manchester University Press |isbn=978-0-7190-4942-2 |page=11}}; {{Cite book |last=Sellers |first=Mortimer N. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zN7lgzjettgC |title=American Republicanism: Roman Ideology in the United States Constitution |date=1994 |publisher=NYU Press |isbn=978-0-8147-8005-3 |page=90}}</ref> It achieved impressive ] and ] feats, such as the empire-wide construction of ] and ], as well as more grandiose monuments and facilities. | |||

| The Roman state evolved from an ] to a ] ] and then to an increasingly ] ] ] during the Empire. Through conquest, ], and ] ], at its height it controlled the ] coast, ], ], and most of ], the ], ] and much of the ], including ], ] and parts of ] and ]. It is often grouped into ] together with ], and their similar cultures and societies are known as the ]. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| Ancient Roman civilisation has contributed to modern language, religion, society, technology, law, politics, government, warfare, art, literature, architecture and engineering. Rome professionalised and expanded its military and created a system of government called '']'', the inspiration for modern ]s such as the United States and France.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bGxiE6jvzOcC|title=A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution|page=793|editor1-last=Furet|editor1-first=François|editor2-last=Ozouf|editor2-first=Mona|publisher=Harvard University Press|date=1989|isbn=978-0674177284}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RMDnAAAAIAAJ|title=Democratization in the South: The Jagged Wave|page=11|last1=Luckham|first1=Robin|last2=White|first2=Gordon|publisher=Manchester University Press|date=1996|isbn=978-0719049422}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zN7lgzjettgC|title=American Republicanism: Roman Ideology in the United States Constitution|page=90|last=Sellers|first=Mortimer N.|publisher=NYU Press|date=1994|isbn=978-0814780053}}</ref> It achieved impressive ] and ] feats, such as the empire-wide construction of ] and ], as well as more grandiose monuments and facilities. | |||

| ===Early Italy and the founding of Rome=== | |||

| The ] with ] gave Rome supremacy in the Mediterranean. The Roman Empire emerged with the ] of ] (from 27 BC); Rome's imperial domain now extended from the Atlantic to ] and from the mouth of the ] to North Africa. In 92 AD, Rome came up against the resurgent ] and became involved in history's longest-running conflict, the ], which would have lasting effects on both empires. Under ], Rome's empire reached its territorial peak, encompassing the entire ], the southern margins of the ], and the shores of the ] and ] Seas. Republican ] started to decline during the imperial period, with civil wars becoming a common prelude to the rise of a new emperor.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_TsTAAAAYAAJ|title=The Greatness and Decline of Rome, Volume 2|page=215|last=Ferrero|first=Guglielmo|translator1-last=Zimmern|translator1-first=Sir Alfred Eckhard|translator2-last=Chaytor|translator2-first=Henry John|publisher=G.P. Putnam's Sons|date=1909}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Ssm3UQYmsYIC|title=Shakespeare and Republicanism|page=68|last=Hadfield|first=Andrew Hadfield|publisher=Cambridge University Press|date=2005|isbn=978-0521816076}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=symGBDPyd5YC|title=The Philosophy of Law: An Encyclopedia, Volume 1|page=741|last=Gray|first=Christopher B|publisher=Taylor & Francis|date=1999|isbn=978-0815313441}}</ref> Splinter states, such as the ], would temporarily divide the Empire during the ] before some stability was restored in the ] phase of imperial rule. | |||

| {{Further|Founding of Rome}} | |||

| {{Multiple image | |||

| | align = right | |||

| | total_width = 420px | |||

| | image1 = Capitoline she-wolf Musei Capitolini MC1181.jpg | |||

| Plagued by internal instability and ] by various migrating peoples, the western part of the empire ] into independent ] in the 5th century.{{efn|This splintering is a landmark historians use to divide the ancient period of ] from the pre-medieval "]" of Europe.}} The ] remained a power through the Middle Ages until its ] in 1453 AD.{{efn|Although the citizens of the empire made no distinction, the empire is most commonly referred to as the "Byzantine Empire" by modern historians to differentiate between the state in antiquity and the state during the Middle Ages.<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia|url=http://www.worldhistory.org/Byzantine_Empire/|title=Byzantine Empire|last=Cartwright|first=Mark|date=19 September 2018|encyclopedia=World History Encyclopedia}}</ref>}} | |||

| | alt1 = Capitoline Wolf | |||

| | caption1 = The ], now illustrating the legend that a ] suckled ] after ]'s imprisonment in ] | |||

| | image2 = Rome in 753 BC.png | |||

| ==Founding myth== | |||

| | alt2 = Rome 753 BC | |||

| | caption2 = Modern reconstruction of the marshy conditions of early Rome, along with a conjectural placement of the ] and ] | |||

| According to the ] of Rome, the ] on 21 April 753 BC on the banks of the river ] in central Italy, by the twin brothers ], who descended from the ] prince ],<ref>{{cite book|last1=Adkins|first1=Lesley|last2=Adkins|first2=Roy|title=Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome|page=3|date=1998|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford|isbn=978-0-19-512332-6}}</ref> and who were grandsons of the Latin King ] of ]. King Numitor was deposed by his brother, ], while Numitor's daughter, ], gave birth to the twins.<ref>{{cite web|last1=Cavazzi|first1=F.|title=The Founding of Rome|url=http://www.roman-empire.net/founding/found-index.html|website=Illustrated History of the Roman Empire|access-date=8 March 2007}}</ref><ref name=livy8 >{{cite book|last1=Livius|first1=Titus (Livy)|translator-last1=Luce|translator-first1=T.J.|title=The Rise of Rome, Books 1–5|date=1998|publisher=Oxford World's Classics|location=Oxford|isbn=978-0-19-282296-3|pages=|url=https://archive.org/details/riseofromebookso00livy/page/8}}</ref> Since Rhea Silvia had been raped and impregnated by ], the Roman ], the twins were considered ]. | |||

| | footer = | |||

| ] in 753 BC by ], who were raised by a she-wolf]] | |||

| }} | |||

| The new king, Amulius, feared Romulus and Remus would take back the throne, so he ordered them to be drowned.<ref name=livy8 /> A ] (or a shepherd's wife in some accounts) saved and raised them, and when they were old enough, they returned the throne of Alba Longa to Numitor.<ref name="Caesarandchrist" >{{cite book|last1=Durant|first1=Will|last2=Durant|first2=Ariel|title=The Story of Civilization – Volume III: Caesar and Christ|date=1944|publisher=Simon and Schuster, Inc.|isbn=978-1567310238|pages=12–14|title-link=The Story of Civilization}}</ref><ref name=livy8 /> | |||

| Archaeological evidence of settlement around Rome starts to emerge {{Circa|1000 BC}}.{{Sfn|Boatwright|2012|p=519}} Large-scale organisation appears only {{Circa|800 BC}}, with the first graves in the ]'s necropolis, along with a ] on the bottom of the ] dating to the middle of the 8th century BC. Starting from {{Circa|650 BC}}, the Romans started to drain the valley between the ] and Palatine Hills, where today sits the ].{{Sfn|Boatwright|2012|p=29}} By the sixth century BC, the Romans were constructing the ] on the Capitoline and expanding to the ] located between the Capitoline and ]s.{{Sfn|Boatwright|2012|p=31}} | |||

| The twins then founded their own city, but Romulus killed Remus in a quarrel over the location of the ], though some sources state the quarrel was about who was going to rule or give his name to the city.<ref>Roggen, Hesse, Haastrup, Omnibus I, H. Aschehoug & Co 1996</ref> Romulus became the source of the city's name.<ref name=livy8 /> In order to attract people to the city, Rome became a sanctuary for the indigent, exiled, and unwanted. This caused a problem, in that Rome came to have a large male population but was bereft of women. Romulus visited neighboring towns and tribes and attempted to secure marriage rights, but as Rome was so full of undesirables he was refused. Legend says that the Latins invited the ]s to a festival and ], leading to the integration of the Latins with the Sabines.<ref>. Retrieved 8 March 2007.</ref> | |||

| The Romans themselves had a ], attributing their city to ], offspring of Mars and a princess of the mythical city of ].{{Sfn|Boatwright|2012|pp=31–32}} The sons, sentenced to death, were rescued by a wolf and returned to restore the Alban king and found a city. After a dispute, Romulus killed Remus and became the city's sole founder. The area of his initial settlement on the Palatine Hill was later known as ] ("Square Rome"). The story dates at least to the third century BC, and the later Roman antiquarian ] placed the city's foundation to 753 BC.{{Sfn|Boatwright|2012|p=32}} Another legend, recorded by Greek historian ], says that Prince Aeneas led a group of Trojans on a sea voyage to found a new Troy after the ]. They landed on the banks of the ] and a woman travelling with them, Roma, torched their ships to prevent them leaving again. They named the settlement after her.<ref>Mellor, Ronald and McGee Marni, ''The Ancient Roman World'' p. 15 (Cited 15 March 2009).</ref> The Roman poet ] recounted this legend in his classical epic poem the '']'', where the Trojan prince ] is destined to found a new Troy. | |||

| The Roman poet ] recounted this legend in his classical epic poem the '']'', where the Trojan prince ] is destined by the gods to found a new Troy. In the epic, the women also refuse to go back to the sea, but they were not left on the Tiber. After reaching Italy, Aeneas, who wanted to marry ], was forced to wage war with her former suitor, ]. According to the poem, the ] were descended from Aeneas, and thus Romulus, the founder of Rome, was his descendant. | |||

| <timeline> | <timeline> | ||

| ImageSize = width:800 height:85 | ImageSize = width:800 height:85 | ||

| PlotArea = width:720 height:55 left:65 bottom:20 | PlotArea = width:720 height:55 left:65 bottom:20 | ||

| AlignBars = justify | AlignBars = justify | ||

| Colors = | Colors = | ||

| id:time value:rgb(0.7,0.7,1) # | id:time value:rgb(0.7,0.7,1) # | ||

| id:period value:rgb(1,0.7,0.5) # | id:period value:rgb(1,0.7,0.5) # | ||

| id:age value:rgb(0.95,0.85,0.5) # | id:age value:rgb(0.95,0.85,0.5) # | ||

| id:era value:rgb(1,0.85,0.5) # | id:era value:rgb(1,0.85,0.5) # | ||

| id:eon value:rgb(1,0.85,0.7) # | id:eon value:rgb(1,0.85,0.7) # | ||

| id:filler value:gray(0.8) # background bar | id:filler value:gray(0.8) # background bar | ||

| id:black value:black | id:black value:black | ||

| Period = from:- |

Period = from:-800 till:1500 | ||

| TimeAxis = orientation:horizontal | TimeAxis = orientation:horizontal | ||

| ScaleMajor = unit:year increment:100 start:- |

ScaleMajor = unit:year increment:100 start:-750 | ||

| ScaleMinor = unit:year increment: |

ScaleMinor = unit:year increment:25 start:-800 | ||

| LineData = | |||

| layer:back at:1 color:black width:0.1 # 1 AD | |||

| PlotData = | PlotData = | ||

| align:center textcolor:black fontsize:8 mark:(line,black) width: |

align:center textcolor:black fontsize:8 mark:(line,black) width:15 shift:(0,-5) | ||

| bar:Roman color:era | |||

| bar: Roman color:era | |||

| from:285 till:476 text:] | |||

| bar: States color:era | |||

| from:-753 till:-508 text:] | from:-753 till:-508 text:] | ||

| from:-508 till:-27 text:] | from:-508 till:-27 text:] | ||

| from:-27 till: |

from:-27 till:285 text:] | ||

| bar:States color:era | |||

| from:285 till:476 text:] | |||

| bar:  color:era | bar:  color:era | ||

| from:285 till:1453 text:] | from:285 till:1453 text:] | ||

| </timeline> | </timeline> | ||

| ==Kingdom== | ===Kingdom=== | ||

| {{Main|Roman Kingdom}} | {{Main|Roman Kingdom}} | ||

| ] ] |

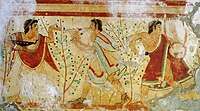

] ] of dancer and musicians from the ] in ]]] | ||

| Literary and archaeological evidence is clear on there having been kings in Rome, attested in fragmentary 6th century BC texts.<ref>{{Harvnb|Boatwright|2012|p=35|ps=. "{{Lang|la|Rex}}, the Latin word for king, appears in two fragmentary sixth-century texts, one an inscription from the shrine of ], and the other a potsherd found in the ]".}}</ref> Long after the abolition of the Roman monarchy, a vestigial ''rex sacrorum'' was retained to exercise the monarch's former priestly functions. The Romans believed that their monarchy was elective, with seven legendary kings who were largely unrelated by blood.{{Sfn|Boatwright|2012|p=36}} | |||

| The city of Rome grew from settlements around a ford on the river ], a crossroads of traffic and trade.<ref name="Caesarandchrist" /> According to ] evidence, the village of Rome was probably founded some time in the 8th century BC, though it may go back as far as the 10th century BC, by members of the ] of Italy, on the top of the ].<ref>{{cite book|last1=Matyszak|first1=Philip|title=Chronicle of the Roman Republic|date=2003|publisher=Thames & Hudson|location=London|isbn=978-0-500-05121-4|page=19}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Duiker|first1=William|last2=Spielvogel|first2=Jackson|title=World History|date=2001|publisher=Wadsworth|isbn=978-0-534-57168-9|page=|edition=Third|url=https://archive.org/details/worldhistoryto1500duik/page/129}}</ref> | |||

| Evidence of Roman expansion is clear in the sixth century BC; by its end, Rome controlled a territory of some {{Convert|780|km2|mi2|abbr=off}} with a population perhaps as high as 35,000.{{Sfn|Boatwright|2012|p=36}} A palace, the ], was constructed {{Circa|625 BC}};{{Sfn|Boatwright|2012|p=36}} the Romans attributed the creation of their first popular organisations and the ] to the regal period as well.{{Sfn|Boatwright|2012|p=37}} Rome also started to extend its control over its Latin neighbours. While later Roman stories like the '']'' asserted that all Latins descended from the character ],{{Sfn|Boatwright|2012|p=39}} a common culture is attested to archaeologically.{{Sfn|Boatwright|2012|p=40}} Attested to reciprocal rights of marriage and citizenship between Latin cities—the {{Lang|la|]}}—along with shared religious festivals, further indicate a shared culture. By the end of the 6th century, most of this area had become dominated by the Romans.{{Sfn|Boatwright|2012|p=42}} | |||

| The ], who had previously settled to the north in ], seem to have established political control in the region by the late 7th century BC, forming an aristocratic and monarchical elite. The Etruscans apparently lost power by the late 6th century BC, and at this point, the original Latin and Sabine tribes reinvented their government by creating a republic, with much greater restraints on the ability of rulers to exercise power.<ref>''Ancient Rome and the Roman Empire'' by Michael Kerrigan. ], London: 2001. {{ISBN|0-7894-8153-7}}. p. 12.</ref> | |||

| ===Republic=== | |||

| Roman tradition and archaeological evidence point to a complex within the ] as the seat of power for the king and the beginnings of the religious center there as well. ], the second ] succeeding ], began Rome's building projects with his royal palace, the ], and the complex of the ]. | |||

| ==Republic== | |||

| {{Main|Roman Republic}} | {{Main|Roman Republic}} | ||

| {{Multiple image | |||

| ] from the ] is traditionally identified as a portrait of ], ] ], 4th to late 3rd centuries BC]] | |||

| | align = right | |||

| According to tradition and later writers such as ], the ] was established around 509 BC,<ref>Langley, Andrew and Souza, de Philip, "The Roman Times", Candle Wick Press, Massachusetts</ref> when the last of the seven kings of Rome, ], was ] by ] and a system based on annually elected ] and various representative assemblies was established.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Matyszak|first1=Philip|title=Chronicle of the Roman Republic|date=2003|publisher=Thames & Hudson|location=London|isbn=978-0-500-05121-4|pages=43–44}}</ref> A ] set a series of ], and a ]. The most important magistrates were the two ], who together exercised executive authority such as '']'', or military command.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Adkins|first1=Lesley|last2=Adkins|first2=Roy|title=Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome|pages=41–42|date=1998|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford|isbn=978-0-19-512332-6}}</ref> The consuls had to work with the ], which was initially an advisory council of the ranking nobility, or ], but grew in size and power.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.wsu.edu/~dee/ROME/REPUBLIC.HTM |title=Rome: The Roman Republic |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110514025151/http://www.wsu.edu/~dee/ROME/REPUBLIC.HTM |archive-date=14 May 2011 |first=Richard |last=Hooker |publisher=Washington State University |date=6 June 1999}}</ref> | |||

| | total_width = 420px | |||

| | image1 = Capitoline Brutus Musei Capitolini MC1183 02.jpg | |||

| Other magistrates of the Republic include ]s, ]s, ]s, ]s and ].<ref name="Lacus"> by George Long, M.A. Appearing on pp. 723–724 of ''A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities'' by William Smith, D.C.L., LL.D. Published by John Murray, London, 1875. Website, 8 December 2006. Retrieved 24 March 2007.</ref> The magistracies were originally restricted to ], but were later opened to common people, or ].<ref>{{cite book|last1=Livius|first1=Titus (Livy)|translator-last1=Luce|translator-first1=T.J.|title=The Rise of Rome, Books 1–5|date=1998|publisher=Oxford World's Classics|location=Oxford|isbn=978-0-19-282296-3|chapter=Book II|chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/riseofromebookso00livy|url-access=registration|url=https://archive.org/details/riseofromebookso00livy}}</ref> Republican voting assemblies included the '']'' (centuriate assembly), which voted on matters of war and peace and elected men to the most important offices, and the '']'' (tribal assembly), which elected less important offices.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Adkins|first1=Lesley|last2=Adkins|first2=Roy|title=Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome|page=39|date=1998|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford|isbn=978-0-19-512332-6}}</ref> | |||

| | alt1 = Capitoline Brutus | |||

| ] (as defined by today's borders) in 400 BC.]] | |||

| | caption1 = The ], a bust traditionally identified as ], one of the founders of the Republic | |||

| In the 4th century BC, Rome had come under attack by the ], who now extended their power in the Italian peninsula beyond the ] and through Etruria. On 16 July 390 BC, a Gallic army under the leadership of tribal chieftain ], ] on the banks of the Allia River ten miles north of Rome. Brennus defeated the Romans, and the Gauls marched to Rome. Most Romans had fled the city, but some barricaded themselves upon the Capitoline Hill for a last stand. The Gauls looted and burned the city, then laid siege to the Capitoline Hill. The siege lasted seven months. The Gauls then agreed to give the Romans peace in exchange for 1000 pounds of gold.<ref>These are literally Roman ''librae'', from which the pound is derived.</ref> According to later legend, the Roman supervising the weighing noticed that the Gauls were using false scales. The Romans then took up arms and defeated the Gauls. Their victorious general ] remarked "With iron, not with gold, Rome buys her freedom."<ref> Plutarch, ''Parallel Lives'', ''Life of Camillus'', XXIX, 2.</ref> | |||

| | image2 = Italy 400bC en.svg | |||

| The Romans ] the other peoples on the Italian peninsula, including the ].<ref name="haywood">{{cite book|last1=Haywood|first1=Richard|title=The Ancient World|url=https://archive.org/details/ancientworld0000unse|url-access=registration|date=1971|publisher=David McKay Company, Inc.|location=United States|pages=–358}}</ref> The last threat to Roman ] in Italy came when ], a major ] colony, enlisted the aid of ] in 281 BC, but this effort failed as well.<ref> and by Jona Lendering. Livius.org. Retrieved 21 March 2007.</ref><ref name=haywood /> The Romans secured their conquests by founding ] in strategic areas, thereby establishing stable control over the region of Italy they had conquered.<ref name=haywood/> | |||

| | alt2 = Italy in 400 BC | |||

| | caption2 = Italy in 400 BC, just prior to the ] ] under ] | |||

| | footer = | |||

| ===Punic Wars=== | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Main|Punic Wars}} | |||

| {{See also|Roman conquest of the Iberian Peninsula}} | |||

| {{more citations needed section|date=September 2014}} | |||

| [[File:Domain changes during the Punic Wars.gif|300px|thumb|upright=2|Rome and Carthage possession changes during the Punic Wars | |||

| {{legend|#ffcb90|Carthaginian possessions}} | |||

| {{legend|#b4d5b1|Roman possessions}}]] | |||

| ] stronghold of ] in present north-central Spain by ] in 133 BC<ref>{{cite book |last1=Bennett |first1=Matthew |last2=Dawson |first2=Doyne |last3=Field |first3=Ron |last4=Hawthornwaite |first4=Philip |last5=Loades |first5=Mike |title=The History of Warfare: The Ultimate Visual Guide to the History of Warfare from the Ancient World to the American Civil War |date=2016 |page=61}}</ref>]] | |||

| By the end of the sixth century, Rome and many of its Italian neighbours entered a period of turbulence. Archaeological evidence implies some degree of large-scale warfare.{{Sfn|Boatwright|2012|p=43}} According to tradition and later writers such as ], the ] was established {{Circa|509 BC}}, {{Sfn|Cornell|1995|pages=215 et seq}} when the last of the seven kings of Rome, ], was ] and a system based on annually elected ] and various representative assemblies was established.{{Sfn|Matyszak|2003|pages=43–44}} A ] set a series of ], and a ]. The most important magistrates were the two ], who together exercised executive authority such as '']'', or military command.{{Sfn|Adkins|Adkins|1998|pp=41–42}} The consuls had to work with the ], which was initially an advisory council of the ranking nobility, or ], but grew in size and power.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Hooker |first=Richard |date=6 June 1999 |title=Rome: The Roman Republic |url=http://www.wsu.edu/~dee/ROME/REPUBLIC.HTM |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110514025151/http://www.wsu.edu/~dee/ROME/REPUBLIC.HTM |archive-date=14 May 2011 |publisher=Washington State University}}</ref> | |||

| In the 3rd century BC Rome faced a new and formidable opponent: ]. Carthage was a rich, flourishing ]n ] that intended to dominate the Mediterranean area. The two cities were allies in the times of Pyrrhus, who was a menace to both, but with Rome's hegemony in mainland Italy and the Carthaginian ], these cities became the two major powers in the Western Mediterranean and their contention over the Mediterranean led to conflict.{{sfn|Goldsworthy|2006|pp=25–26}}{{sfn|Miles|2011|pp=175–176}} | |||

| Other magistrates of the Republic include ]s, ]s, ]s, ]s and ].<ref name="Lacus"> by George Long, M.A. Appearing on pp. 723–724 of ''A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities'' by William Smith, D.C.L., LL.D. Published by John Murray, London, 1875. Website, 8 December 2006. Retrieved 24 March 2007.</ref> The magistracies were originally restricted to ], but were later opened to common people, or ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Livius |first=Titus (Livy) |url=https://archive.org/details/riseofromebookso00livy |title=The Rise of Rome, Books 1–5 |date=1998 |publisher=Oxford World's Classics |isbn=978-0-1928-2296-3 |translator-last=Luce |translator-first=T.J. |chapter=Book II |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/riseofromebookso00livy |url-access=registration}}</ref> Republican voting assemblies included the '']'' (centuriate assembly), which voted on matters of war and peace and elected men to the most important offices, and the '']'' (tribal assembly), which elected less important offices.{{Sfn|Adkins|Adkins|1998|p=39}} | |||

| The ] began in 264 BC, when the city of ] asked for Carthage's help in their conflicts with ]. After the Carthaginian intercession, Messana asked Rome to expel the Carthaginians. Rome entered this war because ] and Messana were too close to the newly conquered Greek cities of Southern Italy and Carthage was now able to make an offensive through Roman territory; along with this, Rome could extend its domain over ].<ref> Cassius Dio, ''Roman History'', XI, XLIII.</ref> | |||

| In the 4th century BC, Rome had come under attack by the ], who now extended their power in the Italian peninsula beyond the ] and through Etruria. On 16 July 390 BC, a Gallic army under the leadership of tribal chieftain ], defeated the Romans at the ] and marched to Rome. The Gauls looted and burned the city, then laid siege to the Capitoline Hill, where some Romans had barricaded themselves, for seven months. The Gauls then agreed to give the Romans peace in exchange for 1000 pounds of gold.<ref>These are literally Roman ''librae'', from which the pound is derived.</ref> According to later legend, the Roman supervising the weighing noticed that the Gauls were using false scales. The Romans then took up arms and defeated the Gauls. Their victorious general ] remarked "With iron, not with gold, Rome buys her freedom."<ref> Plutarch, ''Parallel Lives'', ''Life of Camillus'', XXIX, 2.</ref> | |||

| Although the Romans had experience in land battles, defeating this new enemy required naval battles. Carthage was a maritime power, and the Roman lack of ships and naval experience made the path to the victory a long and difficult one for the ]. Despite this, after more than 20 years of war, Rome defeated Carthage and a peace treaty was signed. Among the reasons for the ]<ref>New historical atlas and general history By Robert Henlopen Labberton. p. 35.</ref> was the subsequent war reparations Carthage acquiesced to at the end of the First Punic War.<ref>{{Cite EB1911|wstitle=Punic Wars|display=Punic Wars § The Interval between the First and Second Wars|volume=22|page=850|first=Maximilian Otto Bismarck|last=Caspari}}</ref> | |||

| The Romans ] the other peoples on the Italian peninsula, including the ].{{Sfn|Haywood|1971|pages=–358}} The last threat to Roman ] in Italy came when ], a major ] colony, enlisted the aid of ] in 281 BC, but this effort failed as well.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160414161122/http://www.livius.org/ps-pz/pyrrhus/pyrrhus02.html |date=14 April 2016 }} and {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303193524/http://www.livius.org/ps-pz/pyrrhus/pyrrhus03.html |date=3 March 2016 }} by Jona Lendering. Livius.org. Retrieved 21 March 2007.</ref>{{Sfn|Haywood|1971|pages=–358}} The Romans secured their conquests by founding ] in strategic areas, thereby establishing stable control over the region.{{Sfn|Haywood|1971|pages=–358}} | |||

| The Second Punic War is famous for its brilliant generals: on the Punic side ] and ]; on the Roman, ], ] and ]. Rome fought this war simultaneously with the ]. The war began with the audacious invasion of Hispania by Hannibal, son of ], a Carthaginian general who had led operations on Sicily towards the end of the First Punic War. Hannibal rapidly marched through ] to the Italian ], causing panic among Rome's Italian allies. The best way found to defeat Hannibal's purpose of causing the Italians to abandon Rome was to delay the Carthaginians with a ] war of attrition, a strategy propounded by Quintus Fabius Maximus, who would be nicknamed ''Cunctator'' ("delayer" in Latin), and whose strategy would be forever after known as ]. Due to this, Hannibal's goal was unachieved: he could not bring enough Italian cities to revolt against Rome and replenish his diminishing army, and he thus lacked the machines and manpower to besiege Rome. | |||

| ] of an unknown man, traditionally identified as ] from the ] (Inv. No. 5634), <br>dated to mid 1st century BC<ref>AncientRome.ru. "." Retrieved 25 August 2016.</ref> <br>Excavated from the ] at ] by ], 1750–65<ref>AncientRome.ru. "." Retrieved 27 November 2021.</ref>]] | |||

| Still, Hannibal's invasion lasted over 16 years, ravaging Italy. Finally, when the Romans perceived the depletion of Hannibal's supplies, they sent Scipio, who had defeated Hannibal's brother Hasdrubal in modern-day Spain, to invade the unprotected Carthaginian hinterland and force Hannibal to return to defend Carthage itself. The result was the ending of the Second Punic War by the famously decisive ] in October 202 BC, which gave to Scipio his ] ''Africanus''. At great cost, Rome had made significant gains: the conquest of Hispania by Scipio, and of Syracuse, the last Greek realm in Sicily, by Marcellus. | |||

| ====Punic Wars==== | |||

| More than a half century after these events, Carthage was humiliated and Rome was no more concerned about the African menace. The Republic's focus now was only to the ] kingdoms of Greece and ]. However, Carthage, after having paid the war indemnity, felt that its commitments and submission to Rome had ceased, a vision not shared by the ]. When in 151 BC ] invaded Carthage, Carthage asked for Roman intercession. Ambassadors were sent to Carthage, among them was ], who after seeing that Carthage could make a comeback and regain its importance, ended all his speeches, no matter what the subject was, by saying: "'']''" ("Furthermore, I think that Carthage must be destroyed"). | |||

| {{Main|Punic Wars}} | |||

| {{See also|Roman conquest of the Iberian Peninsula}} | |||

| ]: | |||

| {{Legend|#b4d5b1|Roman possessions and close allies}} | |||

| {{Legend|#ffcb90|] and close allies }}]] | |||

| ] stronghold of ] in Spain in 133 BC<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Bennett |first1=Matthew |title=The History of Warfare: The Ultimate Visual Guide to the History of Warfare from the Ancient World to the American Civil War |last2=Dawson |first2=Doyne |last3=Field |first3=Ron |last4=Hawthornwaite |first4=Philip |last5=Loades |first5=Mike |date=2016 |page=61}}</ref>]] | |||

| In the 3rd century BC Rome faced a new and formidable opponent: ], the other major power in the Western Mediterranean.<ref>{{Harvnb|Goldsworthy|2006|pp=25–26}}; {{Harvnb|Miles|2011|pp=175–176}}.</ref> The ] began in 264 BC, when the city of ] asked for Carthage's help in their conflicts with ]. After the Carthaginian intercession, Messana asked Rome to expel the Carthaginians. Rome entered this war because ] and Messana were too close to the newly conquered Greek cities of Southern Italy and Carthage was now able to make an offensive through Roman territory; along with this, Rome could extend its domain over ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Cassius Dio – Fragments of Book 11 |url=https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Cassius_Dio/11*.html |access-date=6 September 2022 |website=penelope.uchicago.edu}}</ref> | |||

| As Carthage fought with Numidia without Roman consent, the ] began when Rome declared war against Carthage in 149 BC. Carthage resisted well at the first strike, with the participation of all the inhabitants of the city. However, Carthage could not withstand the attack of ], who entirely destroyed the city and its walls, enslaved and sold all the citizens and gained control of that region, which became the province of ]. Thus ended the Punic War period. All these wars resulted in Rome's first overseas conquests (Sicily, Hispania and Africa) and the rise of Rome as a significant imperial power and began the end of democracy. | |||

| <ref name=haywood2 >{{cite book|last1=Haywood|first1=Richard|title=The Ancient World|url=https://archive.org/details/ancientworld0000unse|url-access=registration|date=1971|publisher=David McKay Company, Inc.|location=United States|pages=–393}}</ref><ref> by Richard Hooker. Washington State University. 6 June 1999. Retrieved 22 March 2007.</ref> | |||

| Carthage was a maritime power, and the Roman lack of ships and naval experience made the path to the victory a long and difficult one for the ]. Despite this, after more than 20 years of war, Rome defeated Carthage and a peace treaty was signed. Among the reasons for the ]<ref>{{Cite book |title=New historical atlas and general history |first=Robert Henlopen |last=Labberton |page=35}}</ref> was the subsequent war reparations Carthage acquiesced to at the end of the First Punic War.<ref>{{Cite EB1911|wstitle=Punic Wars|display=Punic Wars § The Interval between the First and Second Wars|volume=22|page=850|first=Maximilian Otto Bismarck|last=Caspari}}</ref> The war began with the audacious invasion of Hispania by ], who marched through ] to the Italian ], causing panic among Rome's Italian allies. The best way found to defeat Hannibal's purpose of causing the Italians to abandon Rome was to delay the Carthaginians with a ] war of attrition, a strategy propounded by ]. Hannibal's invasion lasted over 16 years, ravaging Italy, but ultimately Carthage was defeated in the decisive ] in October 202 BC. | |||

| == Late Republic == | |||

| After defeating the ]ian and ]s in the 2nd century BC, the ] became the dominant people of the ].<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/e/roman/texts/secondary/burlat/home.html|title=History of the Later Roman Empire|last=Bury|first=John Bagnell|publisher=MacMillan and Co.|year=1889|location=London, New York|author-link=J. B. Bury}}</ref><ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110501115720/http://www.wsu.edu/~dee/ROME/CONQHELL.HTM |date=1 May 2011 }} by Richard Hooker. Washington State University. 6 June 1999. Retrieved 22 March 2007.</ref> The conquest of the Hellenistic kingdoms brought the Roman and Greek cultures in closer contact and the Roman elite, once rural, became a luxurious and cosmopolitan one. At this time Rome was a consolidated empire—in the military view—and had no major enemies. | |||

| More than a half century after these events, Carthage was left humiliated and the Republic's focus was now directed towards the ] kingdoms of Greece and ]. However, Carthage, having paid the war indemnity, felt that its commitments and submission to Rome had ceased, a vision not shared by the ]. The ] began when Rome declared war against Carthage in 149 BC. Carthage resisted well at the first strike but could not withstand the attack of ], who entirely destroyed the city, enslaved all the citizens and gained control of that region, which became the province of ]. All these wars resulted in Rome's first overseas conquests (Sicily, Hispania and Africa) and the rise of Rome as a significant imperial power.<ref>{{Harvnb|Haywood|1971|pages=–393}}; {{Cite web |last=Hooker |first=Richard |date=6 June 1999 |title=Rome: The Punic Wars |url=http://www.wsu.edu/~dee/ROME/PUNICWAR.HTM |access-date=22 March 2007 |website=Washington State University}}</ref> | |||

| ], a Roman general and politician who dramatically reformed the ]]]Foreign dominance led to internal strife. Senators became rich at the ]' expense; soldiers, who were mostly small-scale farmers, were away from home longer and could not maintain their land; and the increased reliance on foreign ] and the growth of '']'' reduced the availability of paid work.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Duiker|first1=William|last2=Spielvogel|first2=Jackson|title=World History|date=2001|publisher=Wadsworth|isbn=978-0-534-57168-9|pages=|edition=Third|url=https://archive.org/details/worldhistoryto1500duik/page/136}}</ref><ref>. ]. Retrieved 24 March 2007.</ref> | |||

| === Late Republic === | |||

| Income from war booty, ] in the new provinces, and ] created new economic opportunities for the wealthy, forming a new class of ]s, called the ].<ref name="Liviuseques"> by Jona Lendering. Livius.org. Retrieved 24 March 2007.</ref> The '']'' forbade members of the Senate from engaging in commerce, so while the equestrians could theoretically join the Senate, they were severely restricted in political power.<ref name="Liviuseques" /><ref>{{cite book|last1=Adkins|first1=Lesley|last2=Adkins|first2=Roy|title=Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome|page=38|date=1998|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford|isbn=978-0-19-512332-6}}</ref> The Senate squabbled perpetually, repeatedly blocked important ]s and refused to give the equestrian class a larger say in the government. | |||

| After defeating the ]ian and ]s in the 2nd century BC, the ] became the dominant people of the ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bury |first=John Bagnell |url=https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/e/roman/texts/secondary/burlat/home.html |title=History of the Later Roman Empire |publisher=MacMillan and Co. |year=1889|author-link=J. B. Bury}}; {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110501115720/http://www.wsu.edu/~dee/ROME/CONQHELL.HTM |date=1 May 2011}} by Richard Hooker. Washington State University. 6 June 1999. Retrieved 22 March 2007.</ref> The conquest of the Hellenistic kingdoms brought the Roman and Greek cultures in closer contact and the Roman elite, once rural, became cosmopolitan. At this time Rome was a consolidated empire—in the military view—and had no major enemies. | |||

| {{Multiple image | |||

| Violent gangs of the urban unemployed, controlled by rival Senators, intimidated the electorate through violence. The situation came to a head in the late 2nd century BC under the ] brothers, a pair of ]s who attempted to pass land reform legislation that would redistribute the major patrician landholdings among the plebeians. Both brothers were killed and the Senate passed reforms reversing the Gracchi brother's actions.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kmZHKOHgvFQC|title=Twenty-six Centuries of Agrarian Reform: A Comparative Analysis|page=34|last=Tuma|first=Elias H.|publisher=University of California Press|date=1965}}</ref> This led to the growing divide of the plebeian groups (]) and equestrian classes (]). | |||

| | align = right | |||

| | total_width = 400 | |||

| | image1 = Marius and the Ambassadors of the Cimbri.jpg | |||

| | alt1 = Gaius Marius | |||

| ], a '']'', who started his political career with the help of the powerful ] family, soon become a leader of the Republic, holding the first of his seven consulships (an unprecedented number) in 107 BC by arguing that his former patron ] was not able to defeat and capture the Numidian king ]. Marius then started his military reform: in his recruitment to fight Jugurtha, he levied the very poor (an innovation), and many landless men entered the army; this was the seed of securing loyalty of the army to the General in command. | |||

| | caption1 = ], a general who dramatically reformed the ] and was repeatedly elected ] to handle invasions of the ] and ] | |||

| | image2 = Q. Pompeius Rufus, denarius, 54 BC, RRC 434-1 (Sulla only).jpg | |||

| ] was born into a poor family that used to be a ] family. He had a good education but became poor when his father died and left none of his will. Sulla joined the theater and found many friends there, prior to becoming a general in the ].<ref>{{Cite book|last=Plutarch|title=Life of Sulla}}</ref> | |||

| | alt2 = L. Cornelius Sulla | |||

| | caption2 = ], leader of the rival ], who ultimately marched on Rome twice, established himself as ], ] and ] of the ] and ] | |||

| | footer = | |||

| }} | |||

| Foreign dominance led to internal strife. Senators became rich at the ]' expense; soldiers, who were mostly small-scale farmers, were away from home longer and could not maintain their land; and the increased reliance on foreign ] and the growth of '']'' reduced the availability of paid work.<ref>{{Harvnb|Duiker|Spielvogel|2001|pages=}}; . ]. Retrieved 24 March 2007.</ref> Income from war booty, ] in the new provinces, and ] created new economic opportunities for the wealthy, forming a new class of merchants, called the ].<ref name="Liviuseques"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140807190312/http://www.livius.org/ei-er/eques/eques.html |date=7 August 2014}} by Jona Lendering. Livius.org. Retrieved 24 March 2007.</ref> The '']'' forbade members of the Senate from engaging in commerce, so while the equestrians could theoretically join the Senate, they were severely restricted in political power.<ref name="Liviuseques"/>{{Sfn|Adkins|Adkins|1998|p=38}} The Senate squabbled perpetually, repeatedly blocked important ]s and refused to give the equestrian class a larger say in the government. | |||

| Violent gangs of the urban unemployed, controlled by rival Senators, intimidated the electorate through violence. The situation came to a head in the late 2nd century BC under the ] brothers, a pair of ]s who attempted to pass land reform legislation that would redistribute the major patrician landholdings among the plebeians. Both brothers were killed and the Senate passed reforms reversing the Gracchi brother's actions.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Tuma |first=Elias H. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kmZHKOHgvFQC |title=Twenty-six Centuries of Agrarian Reform: A Comparative Analysis |date=1965 |publisher=University of California Press |page=34}}</ref> This led to the growing divide of the plebeian groups (]) and equestrian classes (]). | |||

| At this time, Marius began his quarrel with Sulla: Marius, who wanted to capture Jugurtha, asked ], son-in-law of Jugurtha, to hand him over. As Marius failed, Sulla, a ] of Marius at that time, in a dangerous enterprise, went himself to Bocchus and convinced Bocchus to hand Jugurtha over to him. This was very provocative to Marius, since many of his enemies were encouraging Sulla to oppose Marius. Despite this, Marius was elected for five consecutive consulships from 104 to 100 BC, as Rome needed a military leader to defeat the ] and the ], who were threatening Rome. | |||

| ] soon become a leader of the Republic, holding the first of his seven consulships (an unprecedented number) in 107 BC by arguing that his former patron ] was not able to defeat and capture the Numidian king ]. Marius then started his military reform: in his recruitment to fight Jugurtha, he levied the very poor (an innovation), and many landless men entered the army. Marius was elected for five consecutive consulships from 104 to 100 BC, as Rome needed a military leader to defeat the ] and the ], who were threatening Rome. After Marius's retirement, Rome had a brief peace, during which the Italian ''socii'' ("allies" in Latin) requested Roman citizenship and voting rights. The reformist ] supported their legal process but was assassinated, and the ''socii'' revolted against the Romans in the ]. At one point both consuls were killed; Marius was appointed to command the army together with ] and ].<ref name="WHdP-EBp760"/> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| After Marius's retirement, Rome had a brief peace, during which the Italian ''socii'' ("allies" in Latin) requested Roman citizenship and voting rights. The reformist ] supported their legal process but was assassinated, and the ''socii'' revolted against the Romans in the ]. At one point both consuls were killed; Marius was appointed to command the army together with ] and Sulla.<ref name="WHdP-EBp760"/> | |||

| By the end of the Social War, Marius and Sulla were the premier military men in Rome and their partisans were in conflict, both sides jostling for power. In 88 BC, Sulla was elected for his first consulship and his first assignment was to defeat ] of ], whose intentions were to conquer the Eastern part of the Roman territories. However, Marius's partisans managed his installation to the military command, defying Sulla and the ] |

By the end of the Social War, Marius and Sulla were the premier military men in Rome and their partisans were in conflict, both sides jostling for power. In 88 BC, Sulla was elected for his first consulship and his first assignment was to defeat ] of ], whose intentions were to conquer the Eastern part of the Roman territories. However, Marius's partisans managed his installation to the military command, defying Sulla and the ]. To consolidate his own power, Sulla conducted a surprising and illegal action: he marched to Rome with his legions, killing all those who showed support to Marius's cause. In the following year, 87 BC, Marius, who had fled at Sulla's march, returned to Rome while Sulla was campaigning in Greece. He seized power along with the consul ] and killed the other consul, ], achieving his seventh consulship. Marius and Cinna revenged their partisans by conducting a massacre.<ref name="WHdP-EBp760">{{Cite book |last=William Harrison De Puy |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nGxJAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA760 |title=The Encyclopædia britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, and general literature; the R.S. Peale reprint, with new maps and original American articles |publisher=Werner Co. |year=1893 |page=760}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Henry George Liddell |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8mQBAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA305 |title=A history of Rome, to the establishment of the empire |year=1855 |page=305}}</ref> | ||

| Marius died in 86 BC, due to age and poor health, just a few months after seizing power. Cinna exercised absolute power until his death in 84 BC. After returning from his Eastern campaigns, Sulla had a free path to reestablish his own power. In 83 BC he made his ] and began a time of terror: thousands of nobles, knights and senators were executed. Sulla |

Marius died in 86 BC, due to age and poor health, just a few months after seizing power. Cinna exercised absolute power until his death in 84 BC. After returning from his Eastern campaigns, Sulla had a free path to reestablish his own power. In 83 BC he made his ] and began a time of terror: thousands of nobles, knights and senators were executed. Sulla held two ] and one more consulship, which began the crisis and decline of Roman Republic.<ref name="WHdP-EBp760"/> | ||

| ===Caesar and the First Triumvirate=== | ====Caesar and the First Triumvirate==== | ||

| ], 55 BC: Caesar with 100 ships and two legions made an opposed landing, probably near ]. After pressing a little way inland against fierce opposition and losing ships in a storm, he retired back across the ] to Gaul from what was a reconnaissance in force, only to return the following year for a more serious ].]] | ], 55 BC: Caesar with 100 ships and two legions made an opposed landing, probably near ]. After pressing a little way inland against fierce opposition and losing ships in a storm, he retired back across the ] to Gaul from what was a reconnaissance in force, only to return the following year for a more serious ].]] | ||

| In the mid-1st century BC, Roman politics were restless. Political divisions in Rome |

In the mid-1st century BC, Roman politics were restless. Political divisions in Rome split into one of two groups, '']'' (who hoped for the support of the people) and '']'' (the "best", who wanted to maintain exclusive aristocratic control). Sulla overthrew all populist leaders and his constitutional reforms removed powers (such as those of the ]) that had supported populist approaches. Meanwhile, social and economic stresses continued to build; Rome had become a metropolis with a super-rich aristocracy, debt-ridden aspirants, and a large proletariat often of impoverished farmers. The latter groups supported the ]—a resounding failure since the consul ] quickly arrested and executed the main leaders. | ||

| ] reconciled the two most powerful men in Rome: ], who had financed much of his earlier career, and Crassus' rival, ] (anglicised as Pompey), to whom he married ]. He formed them into a new informal alliance including himself, the ] ("three men"). Caesar's daughter died in childbirth in 54 BC, and in 53 BC, Crassus invaded ] and was killed in the ]; the Triumvirate disintegrated. Caesar ], obtained immense wealth, respect in Rome and the loyalty of battle-hardened legions. He became a threat to Pompey and was loathed by many ''optimates''. Confident that Caesar could be stopped by legal means, Pompey's party tried to strip Caesar of his legions, a prelude to Caesar's trial, impoverishment, and exile. | |||

| To avoid this fate, Caesar ] River and invaded Rome in 49 BC. The ] was a brilliant victory for Caesar and in this and other campaigns, he destroyed all of the ''optimates'' leaders: ], ], and Pompey's son, ]. Pompey was murdered in Egypt in 48 BC. Caesar was now pre-eminent over Rome: in five years he held four consulships, two ordinary dictatorships, and two special dictatorships, one for perpetuity. He was murdered in 44 BC, on the ] by the '']''.<ref>. BBC. Retrieved 21 March 2007.</ref> | |||

| In 54 BC, Caesar's daughter, Pompey's wife, died in childbirth, unraveling one link in the alliance. In 53 BC, Crassus invaded ] and was killed in the ]. The Triumvirate disintegrated at Crassus' death. Crassus had acted as mediator between Caesar and Pompey, and, without him, the two generals manoeuvred against each other for power. Caesar ], obtaining immense wealth, respect in Rome and the loyalty of battle-hardened legions. He also became a clear menace to Pompey and was loathed by many ''optimates''. Confident that Caesar could be stopped by legal means, Pompey's party tried to strip Caesar of his legions, a prelude to Caesar's trial, impoverishment, and exile. | |||

| ====Octavian and the Second Triumvirate==== | |||

| To avoid this fate, Caesar ] River and invaded Rome in 49 BC. Pompey and his party fled from Italy, pursued by Caesar. The ] was a brilliant victory for Caesar and in this and other campaigns he destroyed all of the ''optimates''' leaders: ], ], and Pompey's son, ]. Pompey was murdered in Egypt in 48 BC. Caesar was now pre-eminent over Rome, attracting the bitter enmity of many aristocrats. He was granted many offices and honours. In just five years, he held four consulships, two ordinary dictatorships, and two special dictatorships: one for ten years and another for perpetuity. He was murdered in 44 BC, on the ] by the '']''.<ref>. BBC. Retrieved 21 March 2007.</ref> | |||

| Caesar's assassination caused political and social turmoil in Rome; the city was ruled by his friend and colleague, ]. Soon afterward, ], whom Caesar adopted through his will, arrived in Rome. Octavian (historians regard Octavius as Octavian due to the ]) tried to align himself with the Caesarian faction. In 43 BC, along with Antony and ], Caesar's best friend,<ref> Plutarch, Life of Caesar. Retrieved 1 October 2011</ref> he legally established the ]. Upon its formation, 130–300 senators were executed, and their property was confiscated, due to their supposed support for the '']''.<ref> by Garrett G. Fagan. ''De Imperatoribus Romanis''. 5 July 2004. Retrieved 21 March 2007.</ref> | |||

| In 42 BC, the Senate ] Caesar as '']''; Octavian thus became '']'',<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090525075317/http://www.usask.ca/antiquities/coins/augustus.html |date=25 May 2009}}; examples are a coin of 38 BC inscribed "Divi Iuli filius", and another of 31 BC bearing the inscription "Divi filius" ( {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090319090301/http://www2.unine.ch/webdav/site/antic/shared/documents/latin/Memoires/mlreid.pdf |date=19 March 2009}}).</ref> the son of the deified. In the same year, Octavian and Antony defeated both Caesar's assassins and the leaders of the ''Liberatores'', ] and ], in the ]. The Second Triumvirate was marked by the ]s of many senators and ''equites'': after a revolt led by Antony's brother ], more than 300 senators and ''equites'' involved were executed, although Lucius was spared.<ref> Suetonius, ''The Twelve Caesars'', ''Augustus'', XV.</ref> | |||

| ===Octavian and the Second Triumvirate=== | |||

| ]'', by ], painted 1672, National Maritime Museum, London]] | |||

| Caesar's assassination caused political and social turmoil in Rome; without the dictator's leadership, the city was ruled by his friend and colleague, ]. Soon afterward, ], whom Caesar adopted through his will, arrived in Rome. Octavian (historians regard Octavius as Octavian due to the ]) tried to align himself with the Caesarian faction. In 43 BC, along with Antony and ], Caesar's best friend,<ref> Plutarch, Life of Caesar. Retrieved 1 October 2011</ref> he legally established the ]. This alliance would last for five years. Upon its formation, 130–300 senators were executed, and their property was confiscated, due to their supposed support for the '']''.<ref> by Garrett G. Fagan. ''De Imperatoribus Romanis''. 5 July 2004. Retrieved 21 March 2007.</ref> | |||

| The Triumvirate divided the Empire among the triumvirs: Lepidus was given charge of ], Antony, the eastern provinces, and Octavian remained in ] and controlled ] and ]. The Second Triumvirate expired in 38 BC but was renewed for five more years. However, the relationship between Octavian and Antony had deteriorated, and Lepidus was forced to retire in 36 BC after betraying Octavian in ]. By the end of the Triumvirate, Antony was living in ], ruled by his lover, ]. Antony's affair with Cleopatra was seen as an act of treason, since she was queen of another country. Additionally, Antony adopted a lifestyle considered too extravagant and ] for a Roman statesman.<ref> Plutarch, ''Parallel Lives'', ''Life of Antony'', LXXI, 3–5.</ref> Following Antony's ], which ] the title of "]", and to Antony's and Cleopatra's children the regal titles to the newly conquered Eastern territories, ]. Octavian annihilated Egyptian forces in the ] in 31 BC. ]. Now Egypt was conquered by the Roman Empire. | |||

| In 42 BC, the Senate ] Caesar as '']''; Octavian thus became '']'',<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090525075317/http://www.usask.ca/antiquities/coins/augustus.html |date=25 May 2009 }}; examples are a coin of 38 BC inscribed "Divi Iuli filius", and another of 31 BC bearing the inscription "Divi filius" ( {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090319090301/http://www2.unine.ch/webdav/site/antic/shared/documents/latin/Memoires/mlreid.pdf |date=19 March 2009 }}).</ref> the son of the deified. In the same year, Octavian and Antony defeated both Caesar's assassins and the leaders of the ''Liberatores'', ] and ], in the ]. The Second Triumvirate was marked by the ]s of many senators and ''equites'': after a revolt led by Antony's brother ], more than 300 senators and ''equites'' involved were executed on the anniversary of the ], although Lucius was spared.<ref> Suetonius, ''The Twelve Caesars'', ''Augustus'', XV.</ref> The Triumvirate proscribed several important men, including ], whom Antony hated;<ref> Plutarch, ''Parallel Lives'', ''Life of Antony'', II, 1.</ref> ], the younger brother of the orator; and ], cousin and friend of the acclaimed general, for his support of Cicero. However, Lucius was pardoned, perhaps because his sister Julia had intervened for him.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110605231545/http://www.ancientlibrary.com/smith-bio/0547.html |date=5 June 2011 }}. Retrieved 9 September 2011</ref> | |||

| ===Empire – the Principate=== | |||

| The Triumvirate divided the Empire among the triumvirs: Lepidus was given charge of ], Antony, the eastern provinces, and Octavian remained in ] and controlled ] and ]. The Second Triumvirate expired in 38 BC but was renewed for five more years. However, the relationship between Octavian and Antony had deteriorated, and Lepidus was forced to retire in 36 BC after betraying Octavian in ]. By the end of the Triumvirate, Antony was living in ], an independent and rich kingdom ruled by his lover, ]. Antony's affair with Cleopatra was seen as an act of treason, since she was queen of another country. Additionally, Antony adopted a lifestyle considered too extravagant and ] for a Roman statesman.<ref> Plutarch, ''Parallel Lives'', ''Life of Antony'', LXXI, 3–5.</ref> Following Antony's ], which ] the title of "]", and to Antony's and Cleopatra's children the regal titles to the newly conquered Eastern territories, ]. Octavian annihilated Egyptian forces in the ] in 31 BC. ]. Now Egypt was conquered by the Roman Empire, and for the Romans, a new era had begun. | |||

| ==Empire – the Principate== | |||

| {{Main|Roman Empire}} | {{Main|Roman Empire}} | ||

| ], 1st century AD, depicting ], the first ]]] | |||

| In 27 BC and at the age of 36, Octavian was the sole Roman leader. In that year, he took the name '']''. That event is usually taken by historians as the beginning of Roman Empire—although Rome was an "imperial" state since 146 BC, when Carthage was razed by ] and Greece was conquered by ]. Officially, the government was republican, but Augustus assumed absolute powers.<ref> from ]. Retrieved 12 March 2007.</ref><ref name="autogenerated14">Langley, Andrew and Souza, de Philip: "The Roman Times" p.14, Candle Wick Press, 1996</ref> His ] brought about a two-century period colloquially referred to by Romans as the ]. | |||

| In 27 BC and at the age of 36, Octavian was the sole Roman leader. In that year, he took the name '']''. That event is usually taken by historians as the beginning of Roman Empire. Officially, the government was republican, but Augustus assumed absolute powers.<ref> from ]. Retrieved 12 March 2007; {{Cite book |last1=Langley |first1=Andrew |last2=Souza |first2=de Philip |title=The Roman Times |page=14 |publisher=Candle Wick Press |date=1996}}</ref> His ] brought about a two-century period colloquially referred to by Romans as the ]. | |||

| ===Julio-Claudian dynasty=== | |||

| The ] was established by ]. The emperors of this dynasty were Augustus, ], ], ] and ]. The dynasty is so called due to the '']'', family of Augustus, and the '']'', family of Tiberius. The Julio-Claudians started the destruction of republican values, but on the other hand, they boosted Rome's status as the central power in the Mediterranean region.<ref>. by the Department of Greek and ], The ]. October 2000. Retrieved 18 March 2007.</ref> While Caligula and Nero are usually remembered in popular culture as dysfunctional emperors, Augustus and Claudius are remembered as emperors who were successful in politics and the military. This dynasty instituted imperial tradition in Rome<ref>{{cite book|author=James Orr|title=The International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Tn4PAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA2598|year=1915|publisher=Howard-Severance Company|page=2598}}</ref> and frustrated any attempt to reestablish a Republic.<ref>{{cite book|author=Charles Phineas Sherman|title=Roman law in the modern world|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=F1iuAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA50|year=1917|publisher=The Boston book company|page=50}}</ref> | |||

| ==== |

====Julio-Claudian dynasty==== | ||

| The ] was established by ]. The emperors of this dynasty were Augustus, ], ], ] and ]. The Julio-Claudians started the destruction of republican values, but on the other hand, they boosted Rome's status as the central power in the Mediterranean region.<ref>. by the Department of Greek and ], The ]. October 2000. Retrieved 18 March 2007.</ref> While Caligula and Nero are usually remembered in popular culture as dysfunctional emperors, Augustus and Claudius are remembered as successful in politics and the military. This dynasty instituted imperial tradition in Rome<ref>{{Cite book |first=James |last=Orr |title=The International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia |publisher=Howard-Severance Company |year=1915 |page=}}</ref> and frustrated any attempt to reestablish a Republic.<ref>{{Cite book |first=Charles Phineas |last=Sherman |title=Roman law in the modern world |publisher=The Boston book company |year=1917 |page=}}</ref> | |||

| ], 1st century AD, depicting ], the first ]]] | |||

| Augustus gathered almost all the republican powers under his official title, '']'': he had the powers of consul, '']'', ], ] and ]—including tribunician sacrosanctity.<ref> Suetonius, ''The Twelve Caesars'', ''Augustus'', XXVII, 3.</ref> This was the base of an emperor's power. Augustus also styled himself as ''] Gaius Julius Caesar divi filius'', "Commander Gaius Julius Caesar, son of the deified one". With this title he not only boasted his familial link to deified Julius Caesar, but the use of ''Imperator'' signified a permanent link to the Roman tradition of victory. | |||

| Augustus ({{Reign|27 BC|AD 14}}) gathered almost all the republican powers under his official title, '']'', and diminished the political influence of the ] by boosting the ]. The senators lost their right to rule certain provinces, like Egypt, since the governor of that province was directly nominated by the emperor. The creation of the ] and his reforms in the military, creating a ] with a fixed size of 28 legions, ensured his total control over the army.<ref>Werner Eck, ''The Age of Augustus''</ref> Compared with the Second Triumvirate's epoch, Augustus' reign as ''princeps'' was very peaceful, which led the people and the nobles of Rome to support Augustus, increasing his strength in political affairs.<ref>{{Cite EB1911 |wstitle=Augustus |volume=2 |page=912 |first=Henry Francis |last=Pelham |author-link=Henry Francis Pelham}}</ref> His generals were responsible for the field command, gaining such commanders as ], ] and ] much respect from the populace and the legions. Augustus intended to extend the Roman Empire to the whole known world, and in his reign, Rome conquered ], ], ], ], ] and ].<ref> Suetonius, ''The Twelve Caesars'', ''Augustus'', XXI, 1.</ref> | |||

| Under Augustus' reign, Roman literature grew steadily in what is known as the ]. Poets like ], ], ] and ] developed a rich literature, and were close friends of Augustus. Along with ], he sponsored patriotic poems, such as Virgil's epic '']'' and historiographical works like those of ]. Augustus continued the changes to the calendar promoted by ], and the month of August is named after him.<ref> Suetonius, ''The Twelve Caesars'', ''Augustus'', XXI.</ref> Augustus brought a peaceful and thriving era to Rome, known as '']'' or ''Pax Romana''. Augustus died in 14 AD, but the empire's glory continued after his era. | |||

| ]s; areas under Roman control shown here were subject to change even during Augustus' reign, especially in ].]] | |||

| Under Augustus' reign, Roman literature grew steadily in what is known as the ]. Poets like ], ], ] and ] developed a rich literature, and were close friends of Augustus. Along with ], he sponsored patriotic poems, as Virgil's epic '']'' and also historiographical works, like those of ]. The works of this literary age lasted through Roman times, and are classics. Augustus also continued the changes to the calendar promoted by ], and the month of August is named after him.<ref> Suetonius, ''The Twelve Caesars'', ''Augustus'', XXI.</ref> Augustus brought a peaceful and thriving era to Rome, known as '']'' or ''Pax Romana''. Augustus died in 14 AD, but the empire's glory continued after his era. | |||

| The Julio-Claudians continued to rule Rome after Augustus' death and remained in power until the death of Nero in 68 AD.{{Sfn|Duiker|Spielvogel|2001|page=}} Influenced by his wife, ], Augustus appointed her son from another marriage, ], as his heir.<ref> Suetonius, ''The Twelve Caesars'', ''Augustus'', LXIII.</ref> The Senate agreed with the succession, and granted to Tiberius the same titles and honours once granted to Augustus: the title of ''princeps'' and '']'', and the ]. However, Tiberius was not an enthusiast for political affairs: after agreement with the Senate, he retired to ] in 26 AD,<ref> Cassius Dio, ''Roman History'', LVII, 12.</ref> and left control of the city of Rome in the hands of the ] ] (until 31 AD) and ] (from 31 to 37 AD). | |||

| Tiberius died (or was killed)<ref name="tarver1902">{{Cite book |last=John Charles Tarver |title=Tiberius, the tyrant |publisher=A. Constable |date=1902 |pages=}}</ref> in 37 AD. The male line of the Julio-Claudians was limited to Tiberius' nephew ], his grandson ] and his grand-nephew ]. As Gemellus was still a child, Caligula was chosen to rule the empire. He was a popular leader in the first half of his reign, but became a crude and insane tyrant in his years controlling government.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Johann Jakob Herzog |title=The Protestant Theological and Ecclesiastical Encyclopedia: Being a Condensed Translation of Herzog's Real Encyclopedia |last2=John Henry Augustus Bomberger |publisher=Lindsay & Blakiston |year=1858 |page=}}; {{Cite book |title=The Chautauquan |publisher=M. Bailey |year=1881 |page=}}</ref> The Praetorian Guard murdered Caligula four years after the death of Tiberius,<ref>{{Cite book |last=Compendium |title=A compendium of universal history. Ancient and modern, by the author of 'Two thousand questions on the Old and New Testaments' |year=1858 |page=}}</ref> and, with belated support from the senators, proclaimed his uncle ] as the new emperor.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Sir William Smith |title=Abaeus-Dysponteus |publisher=J. Murray |year=1890 |page=}}</ref> Claudius was not as authoritarian as Tiberius and Caligula. Claudius conquered ] and ]; his most important deed was the beginning of the ].<ref> Suetonius, ''The Twelve Caesars'', ''Claudius'', XVII.</ref> Claudius was poisoned by his wife, ] in 54 AD.<ref>Claudius By Barbara Levick. p. 77.</ref> His heir was ], son of Agrippina and her former husband, since Claudius' son ] had not reached manhood upon his father's death. | |||

| ====From Tiberius to Nero==== | |||

| ]s; areas under Roman control shown here were subject to change even during Augustus' reign, especially in ].]] | |||

| The Julio-Claudians continued to rule Rome after Augustus' death and remained in power until the death of Nero in 68 AD.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Duiker|first1=William|last2=Spielvogel|first2=Jackson|title=World History|date=2001|publisher=Wadsworth|isbn=978-0-534-57168-9|page=|edition=Third|url=https://archive.org/details/worldhistoryto1500duik/page/140}}</ref> Augustus' favorites to succeed him were already dead in his senescence: his nephew ] died in 23 BC, his friend and military commander ] in 12 BC and his grandson ] in 4 AD. Influenced by his wife, ], Augustus appointed her son from another marriage, ], as his heir.<ref> Suetonius, ''The Twelve Caesars'', ''Augustus'', LXIII.</ref> | |||

| Nero sent his general, ], to invade modern-day ], where he encountered stiff resistance. The ] there were independent, tough, resistant to tax collectors, and fought Paulinus as he battled his way across from east to west. It took him a long time to reach the north west coast, and in 60 AD he finally crossed the ] to the sacred island of Mona (]), the last stronghold of the ]s.<ref>{{Cite book |title=Brief History: Brief History of Great Britain |date=2009 |publisher=Infobase Publishing |page=34}}</ref> His soldiers ] and massacred the druids: men, women and children,<ref>{{Cite book |title=England Invaded |date=2014 |publisher=Amberley Publishing Limited |page=27}}</ref> destroyed the shrine and the ]s and threw many of the sacred standing stones into the sea. While Paulinus and his troops were massacring druids in Mona, the tribes of modern-day ] staged a revolt led by queen ] of the ].<ref>{{Cite book |title=In the Name of Rome: The Men Who Won the Roman Empire |date=2010 |publisher=Hachette UK |page=30}}</ref> The rebels sacked and burned ], ] and ] (modern-day ], London and ] respectively) before they were ].<ref>{{Cite web |date=27 September 2016 |title=Gaius Suetonius Paulinus |url=https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/daily/military-history/gaius-suetonius-paulinus/ |access-date=21 February 2023 |archive-date=13 July 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210713102217/https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/2016/09/27/gaius-suetonius-paulinus/ |url-status=dead }}</ref> Boadicea, like ] before her, committed suicide to avoid the disgrace of being paraded in triumph in Rome.<ref>{{Cite book |title=Making Europe: The Story of the West, Volume I to 1790 |date=2013 |page=162}}</ref> Nero is widely known as the first persecutor of ] and for the ], rumoured to have been started by the emperor himself.<ref> Suetonius, ''The Twelve Caesars'', ''Nero'', XVI.; Tacitus, ''Annales'', XXXVIII.</ref> A conspiracy against Nero in 65 AD under ] failed, but in 68 AD the armies under ] in Gaul and ] in modern-day Spain revolted. Deserted by the Praetorian Guards and condemned to death by the senate, Nero killed himself.<ref> by Herbert W. Benario. De Imperatoribus Romanis. 10 November 2006. Retrieved 18 March 2007.</ref> | |||