| Revision as of 16:50, 24 January 2006 view sourceLiamdaly620 (talk | contribs)1,598 edits Popups-assisted reversion to revision 36512130← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 02:50, 20 December 2024 view source Citation bot (talk | contribs)Bots5,405,238 edits Altered template type. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Whoop whoop pull up | #UCB_webform 51/662 | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Psychoactive drug from the cannabis plant}} | |||

| :''For the physiology and science of the plant, see ]. For cultivation and non-drug uses see ].'' | |||

| {{Redirect|Marijuana}} | |||

| {{Pp-move-indef}} | |||

| {{pp-semi-vandalism|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2021}} | |||

| {{Infobox botanical product | |||

| | pronounce = Cannabis: {{IPAc-en|ˈ|k|æ|n|ə|b|ᵻ|s}}<br />Marijuana: {{IPAc-en|ˌ|m|æ|r|ə|ˈ|w|ɑː|n|ə}} | |||

| | product = Cannabis | |||

| | image = Cannabis Drying out the crop (16558794823).jpg | |||

| | caption = Cannabis in the drying phase | |||

| | plant = '']'', '']'', '']''{{efn|Pure ] of ''C. ruderalis'' are rarely used for recreational purposes.<ref>{{Cite book|title = Marijuana Horticulture: The Indoor/Outdoor Medical Grower's Bible|last = Cervantes|first = Jorge|publisher = Van Patten Publishing|year = 2006|isbn = 9781878823236|pages = |edition = 5th|url-access = registration|url = https://archive.org/details/marijuanahorticu00jorg/page/12}}</ref>}} | |||

| | part = ] and ] | |||

| | origin = Central or South Asia | |||

| | active = ], ], ], ] | |||

| | producers = Afghanistan, Canada, China, Colombia, India, Jamaica, Lebanon, Mexico, Morocco, Netherlands, Pakistan, Paraguay, Spain, Thailand, Turkey, United Kingdom, United States | |||

| | legal_AU = S8 | |||

| | legal_BR = E | |||

| | legal_CA = Unscheduled | |||

| | legal_DE = legal under the ruling of ] | |||

| | legal_NZ = Class B (concentrate)<br />Class C (plant) | |||

| | legal_UK = Class B | |||

| | legal_US = ] | |||

| | legal_UN = Narcotic Schedule I | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Cannabis sidebar}} | |||

| '''Cannabis''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|k|æ|n|ə|b|ᵻ|s}}),<ref>{{cite web |title=cannabis noun – Definition, pictures, pronunciation and usage notes {{!}} Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary at OxfordLearnersDictionaries.com |url=https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/cannabis?q=cannabis |access-date=10 November 2022 |website=www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com}}</ref> commonly known as '''marijuana''' ({{IPAc-en|ˌ|m|æ|r|ə|ˈ|w|ɑː|n|ə}}),<ref>{{cite web |title=marijuana noun – Definition, pictures, pronunciation and usage notes {{!}} Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary at OxfordLearnersDictionaries.com |url=https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/marijuana |access-date=18 April 2019 |website=www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com}}</ref> '''weed''', and '''pot''', ], is a non-chemically uniform ] from the ] plant. Native to Central or South Asia, the cannabis plant has been used as a drug for both recreational and ] purposes and in various ]s for centuries. ] (THC) is the main psychoactive component of cannabis, which is one of the 483 known compounds in the plant, including at least 65 other ]s, such as ] (CBD). Cannabis can be used ], ], ], or ]. | |||

| ]'' plant]] | |||

| The '''cannabis''' plant can be dried or otherwise processed to yield products containing large concentrations of ]s that have ] and ] effects when consumed, usually by smoking or eating. ] has been used for medical and psychoactive effects for thousands of years. Throughout the ] there was a massive upswing in the use of cannabis as a psychoactive substance, mostly for ] but to some extent for ]. The possession, use, or sale of psychoactive cannabis products became ] in many parts of the world during the early ], and remains that way today. | |||

| ]'' plant.'']] | |||

| <!-- Effects --> | |||

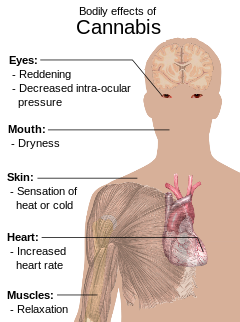

| Cannabis has ], which include ], ] and ], difficulty concentrating, ], impaired ] (balance and fine psychomotor control), relaxation, and an increase in ]. Onset of effects is felt within minutes when smoked, but may take up to 90 minutes when eaten (as orally consumed drugs must be digested and absorbed). The effects last for two to six hours, depending on the amount used. At high doses, mental effects can include ], delusions (including ]), ]s, ], ], and ]. There is a strong relation between cannabis use and the risk of psychosis, though the direction of ] is debated. Physical effects include increased heart rate, difficulty breathing, nausea, and behavioral problems in children whose mothers used cannabis during pregnancy; short-term side effects may also include ] and red eyes. ] may include addiction, decreased ] in those who started regular use as adolescents,<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Shrivastava |first1=Amresh |last2=Johnston |first2=Megan |last3=Tsuang |first3=Ming |date=2011 |title=Cannabis use and cognitive dysfunction |journal=Indian Journal of Psychiatry |volume=53 |issue=3 |pages=187–191 |doi=10.4103/0019-5545.86796 |issn=0019-5545 |pmc=3221171 |pmid=22135433 |doi-access=free }}</ref> chronic coughing, susceptibility to ], and ]. | |||

| <!-- Usage --> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| Cannabis is mostly used recreationally or as a medicinal drug, although it may also be used for spiritual purposes. In 2013, between 128 and 232 million people used cannabis (2.7% to 4.9% of the global population between the ages of 15 and 65). It is the most commonly used largely-illegal drug in the world, with the highest use among adults in ], the ], ], and ]. Since the 1970s, the potency of illicit cannabis has increased, with THC levels rising and CBD levels dropping. | |||

| Cannabis has been known as a medicinal and psychoactive compound from very early in history, and has been used continuously throughout the world, typically without ] until the mid-20th century, when, mainly under the leadership of the ], prohibition became increasingly global.<!-- repression in various Islamic centuries (11th, 13th, and others), early modern (ex-Ottoman) Greece, Egypt under Mehemet Ali (19th century), need sections--> | |||

| <!-- History and legality --> | |||

| ===Ancient history=== | |||

| Cannabis plants have been grown since at least the 3rd millennium BCE and there is evidence of it being smoked for its psychoactive effects around 500 BCE in the ], Central Asia. Since the 14th century, cannabis has been subject to legal restrictions. The possession, use, and cultivation of cannabis has been ] since the 20th century. In 2013, ] became the first country to ] recreational use of cannabis. Other countries to do so are Canada, ], ], ], ], ], and ]. In the U.S., the recreational use of cannabis is legalized in ], 3 territories, and the ], though the drug remains ]. In ], it is legalized only in the ]. | |||

| Cannabis was well known to the ]ns, as well as to the ]/]ns, whose ] (the '']'' - "those who walk on smoke/clouds") used to burn cannabis flowers in order to induce trances. The cult of ], which is believed to have originated in ], has also been linked to the effects of cannabis smoke. The most famous users of cannabis though were the ancient ]s. It was called 'ganjika' in ] ('ganja' in modern Indian languages). According to legend, ], the destructive aspect of the Hindu trinity, told his disciples to use the hemp plant in all ways possible. Cannabis is also thought by some to be the ancient drug ], mentioned in the ]s as a sacred intoxicating hallucinogen, although a number of advocates for different psychoactive substances such as ] make this claim as well. | |||

| ==Etymology== | |||

| === Recent history === | |||

| {{main|Etymology of cannabis}} | |||

| Under the name ''cannabis'' ] medical practitioners helped to introduce the herb's drug potential (usually as a ]) to modern English-speaking consciousness. It was famously used to treat ]'s menstrual pains, and was available from shops in the US. By the end of the 19th century its medicinal use began to fall as other drugs such as ] took over. | |||

| ''Cannabis'' is a ] word.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Gray |first1=Stephen |title=Cannabis and Spirituality: An Explorer's Guide to an Ancient Plant Spirit Ally |date=9 December 2016 |publisher=Simon and Schuster |isbn=978-1-62055-584-2 |page=69 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GmEoDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT69 |language=en |quote=Cannabis is called kaneh bosem in Hebrew, which is now recognized as the Scythian word that Herodotus wrote as kánnabis (or cannabis).}}</ref><ref name="r980">{{cite book | last1=Riegel | first1=A. | last2=Ellens | first2=J.H. | title=Seeking the Sacred with Psychoactive Substances: Chemical Paths to Spirituality and to God | publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing | series=Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality | year=2014 | isbn=979-8-216-14310-9 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=V6nOEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT80 | access-date=2024-06-03 | page=80}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Duncan |first1=Perry M. |title=Substance Use Disorders: A Biopsychosocial Perspective |date=17 September 2020 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-87777-0 |page=441 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=X7H2DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA441|language=en |quote=Cannabis is a Scythian word (Benet 1975).}}</ref> The ] learned of the use of cannabis by observing Scythian funerals, during which cannabis was consumed.<ref name="r980" /> In ], cannabis was known as ''qunubu'' ({{lang|akk|𐎯𐎫𐎠𐎭𐏂}}).<ref name="r980" /> The word was adopted in to the ] as ''qaneh bosem'' ({{lang|he|קָנֶה בֹּשׂם}}).<ref name="r980" /> | |||

| ==Uses== | |||

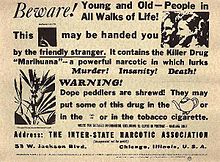

| The name ''marijuana'' (] ''marihuana'', ''mariguana'') is associated almost exclusively with the herb’s drug potential. The term marijuana is now well known in English as a name for drug material due largely to the efforts of US drug prohibitionists during the ] and ], who deliberately used a Mexican name for cannabis in order to turn the populace against the idea that it should be legal. (''see ]'') | |||

| ===Medical=== | |||

| Although cannabis has been used for its psychoactive effects since ancient times, it first became well known in the United States during the ] music scene of the late 1920s and 1930s. ] became one of its most prominent and life-long devotees. Cannabis use was also a prominent part of ] counterculture. | |||

| {{Main|Medical cannabis}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Medical cannabis, or medical marijuana, refers to the use of cannabis to treat disease or improve symptoms; however, there is no single agreed-upon definition (e.g., ] derived from cannabis and synthetic cannabinoids are also used).<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Murnion B |date=December 2015 |title=Medicinal cannabis |journal=Australian Prescriber |volume=38 |issue=6 |pages=212–15 |doi=10.18773/austprescr.2015.072 |pmc=4674028 |pmid=26843715 |issn=0312-8008}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=July 2015 |title=What is medical marijuana? |url=https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/marijuana-medicine |access-date=19 April 2016 |website=National Institute of Drug Abuse |quote=The term medical marijuana refers to using the whole unprocessed marijuana plant or its basic extracts to treat a disease or symptom.}}</ref><ref name="Backes2014">{{Cite book |last=Backes |first=Michael |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7z2FwBywoJ0C&pg=PT46 |title=Cannabis Pharmacy: The Practical Guide to Medical Marijuana |publisher=Hachette Books |date=2014 |isbn=978-1-60376-334-9 |page=46 |name-list-style=vanc}}</ref> The rigorous scientific study of cannabis as a medicine has been hampered by production restrictions and by the fact that it is classified as an illegal drug by many governments.<ref>{{Cite journal |date=September 2015 |title=Release the strains |journal=Nature Medicine |volume=21 |issue=9 |pages=963 |doi=10.1038/nm.3946 |pmid=26340110 |doi-access=free}}</ref> There is some evidence suggesting cannabis can be used to ] during ], to improve appetite in people with ], or to treat ] and ]. Evidence for its use for other medical applications is insufficient for drawing conclusions about safety or efficacy.<ref name="Borgelt2013">{{Cite journal |vauthors=Borgelt LM, Franson KL, Nussbaum AM, Wang GS |date=February 2013 |title=The pharmacologic and clinical effects of medical cannabis |journal=Pharmacotherapy |volume=33 |issue=2 |pages=195–209 |citeseerx=10.1.1.1017.1935 |doi=10.1002/phar.1187 |pmid=23386598 |s2cid=8503107}}</ref><ref name="JAMA2015">{{Cite journal |vauthors=Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, Di Nisio M, Duffy S, Hernandez AV, Keurentjes JC, Lang S, Misso K, Ryder S, Schmidlkofer S, Westwood M, Kleijnen J |date=23 June 2015 |title=Cannabinoids for Medical Use: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis |journal=JAMA |volume=313 |issue=24 |pages=2456–73 |doi=10.1001/jama.2015.6358 |pmid=26103030 |doi-access=free |hdl=10757/558499|hdl-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Jensen B, Chen J, Furnish T, Wallace M |date=October 2015 |title=Medical Marijuana and Chronic Pain: a Review of Basic Science and Clinical Evidence |journal=Current Pain and Headache Reports |volume=19 |issue=10 |pages=50 |doi=10.1007/s11916-015-0524-x |pmid=26325482 |s2cid=9110606}}</ref> There is evidence supporting the use of cannabis or its derivatives in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, neuropathic pain, and multiple sclerosis. Lower levels of evidence support its use for AIDS ], epilepsy, rheumatoid arthritis, and glaucoma.<ref name="NEJM2014" /> | |||

| Today in America, there are 11 states that provide some legal protection for patients who use marijuana with the consent or recommendation of a doctor. Most recently, Rhode Island became the 11th state to pass medical marijuana legislation. Tolerance for the drug appears to be growing in non-medical respects as well. For example, currently in the state of Oregon possession of less than one ] of marijuana for personal use by an adult is considered a violation, not a crime, and is punishable by a simple fine. Various individual cities through the United States (such as ]) have similar legislation. None of these protections, however, will protect a user from federal prosecution. | |||

| The medical use of cannabis is legal only in a limited number of territories, including Canada,<ref name=canada2018/> ], Australia, the ], New Zealand,<ref>{{Cite news |last=Ainge Roy |first=Eleanor |date=11 December 2018 |title=New Zealand passes laws to make medical marijuana widely available |work=The Guardian |url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/dec/11/new-zealand-passes-laws-to-make-medical-marijuana-widely-available |access-date=20 January 2019}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Schulz |first=Chris |date=30 June 2022 |title=You can get actual weed from the doctor now |url=https://thespinoff.co.nz/business/30-06-2022/you-can-get-actual-weed-from-the-doctor-now |website=The Spinoff}}</ref> Spain, and ]. This usage generally requires a prescription, and distribution is usually done within a framework defined by local laws.<ref name="NEJM2014" /> | |||

| On ], ], the city of ], ] passed in a 53%-46% vote to legalize the possession of up to an ounce of marijuana for adults over 21 {{ref|USAToday}}. | |||

| ===Recreational=== | |||

| On ], 2005, a broad coalition of ] in ], ], unveiled a pilot program to allow farmers to legally grow marijuana. As it stands currently, designated ] can sell cannabis, but must be supplied by underground ]s. {{ref|AP}} | |||

| According to DEA Chief Administrative Law Judge, Francis Young, "cannabis is one of the safest therapeutically active substances known to man".<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.safeaccessnow.org/cannabis_safety |title=Information on Cannabis Safety |website=Americans for Safe Access}}</ref> Being under the effects of cannabis is usually referred to as being "high".<ref name="Small2016">{{Cite book |last=Ernest Small |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oo2KDQAAQBAJ&pg=PT339 |title=Cannabis: A Complete Guide |publisher=CRC Press |date=2016 |isbn=978-1-315-35059-2}}</ref> Cannabis consumption has both psychoactive and physiological effects.<ref name="OnaiviSugiura2005">{{Cite book |last1=Onaivi |first1=Emmanuel S. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BxfLB4n3uoMC&pg=PA58 |title=Endocannabinoids: The Brain and Body's Marijuana and Beyond |last2=Sugiura |first2=Takayuki |last3=Di Marzo |first3=Vincenzo |publisher=Taylor & Francis |date=2005 |isbn=978-0-415-30008-7 |page=58 |name-list-style=vanc}}</ref> The "high" experience can vary widely, based (among other things) on the user's prior experience with cannabis, and the type of cannabis consumed.<ref name="curran2014">{{Cite encyclopedia |title=Desired and Undesired Effects of Cannabis on the Human Mind and Psychological Well-Being |encyclopedia=Handbook of Cannabis |publisher=Oxford University Press |date=2014 |editor-last=Pertwee |editor-first=Roger G. |last2=Morgan |first2=Celia J.A. |last1=Curran |first1=H. Valerie}}</ref>{{rp|p647}} When smoking cannabis, a ]nt effect can occur within minutes of smoking.<ref name="ashton2001">{{Cite journal |last=Ashton |first=C.Heather |date=2001 |title=Pharmacology and Effects of Cannabis: A Brief Review |journal=British Journal of Psychiatry |volume=178 |issue=2 |pages=101–06 |doi=10.1192/bjp.178.2.101 |pmid=11157422 |s2cid=15918781 |doi-access=free}}</ref>{{rp|p104}} Aside from a subjective change in perception and mood, the most common short-term physical and neurological effects include increased heart rate, increased appetite, impairment of short-term and working memory, and impairment of ].<ref name="Mathre1997">{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1AWGDhIOvk0C&pg=PA144 |title=Cannabis in Medical Practice: A Legal, Historical, and Pharmacological Overview of the Therapeutic Use of Marijuana |publisher=University of Virginia Medical Center |date=1997 |isbn=978-0-7864-8390-7 |editor-last=Mathre |editor-first=Mary Lynn |pages=144– |name-list-style=vanc}}</ref><ref name="memoryhindered">{{Cite book |title=Cannabinoids |vauthors=Riedel G, Davies SN |date=2005 |isbn=978-3-540-22565-2 |series=Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology |volume=168 |pages=445–77 |chapter=Cannabinoid function in learning, memory and plasticity |doi=10.1007/3-540-26573-2_15 |pmid=16596784 |issue=168}}</ref> | |||

| Additional desired effects from consuming cannabis include relaxation, a general ], increased awareness of sensation, increased ]<ref name="pmid18365950">{{Cite journal |vauthors=Osborne GB, Fogel C |date=2008 |title=Understanding the motivations for recreational marijuana use among adult Canadians |url=http://cannabislink.ca/info/MotivationsforCannabisUsebyCanadianAdults-2008.pdf |journal=Substance Use & Misuse |volume=43 |issue=3–4 |pages=539–72; discussion 573–79, 585–87 |doi=10.1080/10826080701884911 |pmid=18365950 |s2cid=31053594}}</ref> and ] and space. At higher doses, effects can include altered ], auditory or visual ]s, ]s and ] from selective impairment of ] ]es.{{Citation needed|date=June 2020}} In some cases, cannabis can lead to ] states such as ]<ref name="medscape1">{{Cite web |title=Medication-Associated Depersonalization Symptoms |url=http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/468728 |website=Medscape}}</ref><ref name="pmid15889607">{{Cite journal |vauthors=Shufman E, Lerner A, Witztum E |date=April 2005 |title= |url=http://www.ima.org.il/Ima/FormStorage/Type3/05-04-07.pdf |journal=Harefuah |language=he |volume=144 |issue=4 |pages=249–51, 303 |pmid=15889607 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050430224332/http://www.ima.org.il/Ima/FormStorage/Type3/05-04-07.pdf |archive-date=30 April 2005}}</ref> and ].<ref name="Johnson1990">{{Cite journal |vauthors=Johnson BA |date=February 1990 |title=Psychopharmacological effects of cannabis |journal=British Journal of Hospital Medicine |volume=43 |issue=2 |pages=114–16, 118–20, 122 |pmid=2178712}}</ref> | |||

| == Wild cannabis== | |||

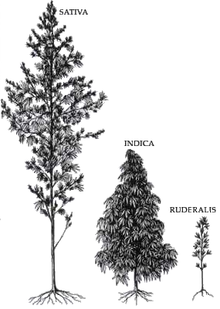

| Cannabis still grows wild in many places around the world. The most prominent variety being Cannabis Sativa which found growing wild in places such as ], ], ], parts of ], ], ], ], and ]. Wild Cannabis Indica is mainly confined to hash producing areas such as ], and Northern ]. The wild C. Sativa has a lot of genetic variation from place to place. For example the wild C. Sativa in warm places can reach heights up to 20 ft. tall, but in colder climates it can be as short as a 1 ft. in height. Almost every single flower bract bears a seed. The wild C. Sativa has long, thin and airy buds and mostly, a christmas tree shape structure. Wild C. Indica for the most part remains compact and bushy with thick buds, and is sometimes used by the locals for hashish production. Generally, there are far fewer seeds in wild C. Indica. | |||

| In many areas the wild population of cannabis is threatened due to government eradication and urbanziation. | |||

| ===Spiritual=== | |||

| ==New breeding and cultivation techniques== | |||

| {{Main|Entheogenic use of cannabis}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main_article|]}} | |||

| Advances in breeding and cultivation techniques have increased the diversity and potency of ] over the last 20 years, and these strains are now widely smoked all over the world. These advances- the ], breeding, ], ], ], ], ], etc— have been in part a response to prohibition enforcement efforts which have made outdoor cultivation more risky, and so efficient indoor cultivation more common. | |||

| Cannabis has held sacred status in several religions and has served as an ] – a ] used in religious, ], or ] contexts<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Souza |first1=Rafael Sampaio Octaviano de |last2=Albuquerque |first2=Ulysses Paulino de |last3=Monteiro |first3=Júlio Marcelino |last4=de Amorim |first4=Elba Lúcia Cavalcanti |name-list-style=vanc |date=2008 |title=Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology – Jurema-Preta (Mimosa tenuiflora Poir.): a review of its traditional use, phytochemistry and pharmacology |journal=Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology |volume=51 |issue=5 |pages=937–47 |doi=10.1590/S1516-89132008000500010 |doi-access=free}}</ref> – in the Indian subcontinent since the ]. The earliest known reports regarding the sacred status of cannabis in the Indian subcontinent come from the ], estimated to have been composed sometime around 1400 BCE.<ref name="courtwright2001">{{Cite book |last=Courtwright |first=David |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GHqV3elHYvMC&q=Forces+of+Habit |title=Forces of Habit: Drugs and the Making of the Modern World |publisher=Harvard University Press |date=2001 |isbn=978-0-674-00458-0 |name-list-style=vanc}}</ref> | |||

| The increases in potency - and ramifications thereof - have been exaggerated by opponents of cannabis use both in and out of government. In the United States, government advertisements encourage parents to disregard their own experience with cannabis when speaking to their children, on the premise that <!--don't change this, it is intentionally-->pot<!--like in the ads to which I refer--> today is significantly stronger - and thus more dangerous - than that which they themselves might have smoked in the past. In a general pattern of proposing reverses in ], the UK government is considering scheduling stronger cannabis (''skunk'', in local parlance) as a separate, more restricted substance. | |||

| The Hindu god ] is described as a cannabis user, known as the "Lord of ]".<ref name="Iversen2000s">{{Cite book |last=Iversen |first=Leslie L. |url=https://archive.org/details/scienceofmarijua00iver |title=The Science of Marijuana |publisher=Oxford University Press |date=2000 |isbn=978-0-19-515110-7 |url-access=registration |name-list-style=vanc}}</ref>{{rp|p19}} | |||

| In modern culture, the spiritual use of cannabis has been spread by the disciples of the ] who use cannabis as a ] and as an aid to meditation.<ref name=courtwright2001/> | |||

| ==Consumption== | |||

| == Immediate effects of human consumption == | |||

| {{Main|Cannabis consumption}} | |||

| The nature and intensity of the immediate effects of cannabis consumption vary according to the dose, the species or hybridization of the source plant, the method of consumption, the user's mental and physical characteristics (such as possible tolerance), and the environment of consumption. Effects of cannabis consumption may be loosely classified as cognitive and physical. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the '']'' species tends to produce more of the cognitive or perceptual effects, while '']'' tends to produce more of the physical effects. | |||

| === Cognitive, behavioral, or perceptual === | |||

| Cannabis has a broad spectrum of possible cognitive, behavioral, or perceptual effects, the occurrence of which vary from user to user. Some of these are the intended effect desired by users, some may be considered desirable depending on the situation, and others are generally considered undesirable. Users of cannabis report that these kinds of effects are more often produced by the '']'' species of cannabis. | |||

| === |

=== Modes of consumption === | ||

| ]{{Cookbook|Cannabis}} | |||

| Cannabis also has effects that are predominantly physical or sensory. It is widely believed that the '']'' species of '''Cannabis''' is more likely to produce effects like these. | |||

| Many different ways to consume cannabis involve heat to ] ] into THC;<ref name="Golub2012a">{{Cite book |last=Golub |first=Andrew |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KFMtFv2tmbYC&pg=PA82 |title=The Cultural/Subcultural Contexts of Marijuana Use at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century |publisher=Routledge |date=2012 |isbn=978-1-136-44627-6 |page=82 |name-list-style=vanc}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Why Does Cannabis Have to be Heated? |url=https://patriotcare.org/why-cannabis-heated/ |website=patriotcare.org}}</ref> common modes include: | |||

| * ], involves burning and inhaling cannabinoids ("smoke") from ], ]s (portable versions of ]s with a water chamber), paper-wrapped ], tobacco-leaf-wrapped ], or the like.<ref name="TasmanKay2011">{{Cite book |last1=Tasman |first1=Allan |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vVG7zz7eaxcC&pg=RA9-PT2217 |title=Psychiatry |last2=Kay |first2=Jerald |last3=Lieberman |first3=Jeffrey A. |last4=First |first4=Michael B. |last5=Maj |first5=Mario |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |date=2011 |isbn=978-1-119-96540-4 |page=9 |name-list-style=vanc}}</ref> | |||

| * ], heating various forms of cannabis to {{convert|165|–|190|°C|°F}},<ref name="Rosenthal2002b">{{Cite book |last=Rosenthal |first=Ed |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=obbSwmSB6okC&pg=PT15 |title=Ask Ed: Marijuana Gold: Trash to Stash |publisher=Perseus Books Group |date=2002 |isbn=978-1-936807-02-4 |page=15 |name-list-style=vanc}}</ref> causing the active ingredients to form ] without combustion of the plant material (the boiling point of ] is {{convert|157|°C|°F}} at atmospheric pressure).<ref>{{Cite web |title=Cannabis and Cannabis Extracts: Greater Than the Sum of Their Parts? |url=http://www.cannabis-med.org/data/pdf/2001-03-04-7.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170622203721/http://www.cannabis-med.org/data/pdf/2001-03-04-7.pdf |archive-date=22 June 2017 |access-date=7 April 2014 |publisher=Cannabis-med.org}}</ref> | |||

| * ], adding cannabis as an ingredient to a wide variety of foods, including butter and baked goods. In India it is commonly consumed as the beverage ]. | |||

| * ], prepared with attention to the ] quality of THC, which is only slightly water-soluble (2.8 mg per liter),<ref name="Physical Properties – Dronabinol">{{PubChem|16078|Dronabinol}}</ref> often involving cannabis in a ].<ref name="Ph.D.Rosenthal2008yt">{{Cite book |last1=Gieringer |first1=Dale |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OuAHxDKcpS8C&pg=PA182 |title=Marijuana medical handbook: practical guide to therapeutic uses of marijuana |last2=Rosenthal |first2=Ed |publisher=QUICK AMER Publishing Company |date=2008 |isbn=978-0-932551-86-3 |page=182 |name-list-style=vanc}}</ref> | |||

| * ], sometimes known as green dragon, is an ] ]. | |||

| * ], typically containing ], and other ] products, for which some 220 were approved in Canada in 2018.<ref name="canada2018">{{Cite web |date=11 July 2018 |title=Health products containing cannabis or for use with cannabis: Guidance for the Cannabis Act, the Food and Drugs Act, and related regulations |url=https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/drug-products/applications-submissions/guidance-documents/guidance-cannabis-act-food-and-drugs-act-related-regulations/document.html |access-date=19 October 2018 |publisher=Government of Canada}}</ref> | |||

| === Consumption by country === | |||

| ====List of effects==== | |||

| {{main|Annual cannabis use by country}} | |||

| * ] properties | |||

| {{Global estimates of illicit drug users}} | |||

| * Modulation of ] and ] | |||

| * Impairment of short-term memory | |||

| * Enhancement of many other drugs (including ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and many others) | |||

| * ] or visual ] at high doses in some users | |||

| * Exaggerated ] | |||

| * ], ] and ] | |||

| * Increased ] (sometimes referred to as "the munchies"), an effect of stimulation of the ] system, which affects ], ], and ]. | |||

| * Increased ] | |||

| * Increased awareness of ] | |||

| * Increased awareness of ]s and ]s | |||

| * Increased mental activity, like ] | |||

| * Induced sense of ] | |||

| * Initial ] followed by ] and lassitude ('burnt out') | |||

| * ] or ] states of mind | |||

| * Gain or loss of some ] | |||

| * Mild ], feelings of general well-being | |||

| * Relaxation or ] reduction | |||

| * ] (Increased heart rate) | |||

| * ] (sometimes referred to as ''cottonmouth'', ''pasties'', or ''the drys'' (NZ)) | |||

| * ] (sometimes referred to as ''blood-shot eyes,'' ''dry eyes'' or ''red eye''(UK)) | |||

| In 2013, between 128 and 232 million people used cannabis (2.7% to 4.9% of the global population between the ages of 15 and 65).<ref name="WDR2015">{{Cite book |title=World Drug Report 2015 |page=23 |chapter=Status and Trend Analysis of {{sic|nolink=y|Illict}} Drug Markets |access-date=26 June 2015 |chapter-url=http://www.unodc.org/documents/wdr2015/WDR15_Drug_use_health_consequences.pdf}}</ref> Cannabis is by far the most widely used illicit substance,<ref name="CaulkinsHawken2012">{{Cite book |last1=Caulkins |first1=Jonathan P. |url=https://archive.org/details/marijuanalegaliz0000unse/page/16 |title=Marijuana Legalization: What Everyone Needs to Know |last2=Hawken |first2=Angela |last3=Kilmer |first3=Beau |last4=Kleiman |first4=Mark A.R. |publisher=Oxford University Press |date=2012 |isbn=978-0199913732 |page= |name-list-style=vanc}}</ref> with the highest use among adults ({{as of|2018|lc=y}}) in ], the ], ], and ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=UNODC Statistics Online |url=https://data.unodc.org/ |access-date=9 September 2018 |website=data.unodc.org}}</ref> | |||

| ====List of therapeutic effects ==== | |||

| * Pain relief (especially ]s, ]s, and eye pain due to lowered ]). | |||

| * Increased ], food subjectively tastes better. | |||

| * Reduced ], (especially from chemotherapy), though may cause or exacerbate nausea for some. | |||

| * Dilation of ] (air sacs) in ], resulting in deeper respiration. | |||

| * Increase in productive coughs | |||

| * Dilation of ]s (]), resulting in: | |||

| ** Increased blood flow and heart rate | |||

| ** Reddening of the conjunctivae (red eye) | |||

| * Lower intra-] pressure (beneficial to ] patients). | |||

| * Lower ] while standing. Higher blood pressure while sitting (note that this can lead to instances of ]). | |||

| * Induces drowsiness (beneficial to sufferers of ] and ]). | |||

| * Relaxation | |||

| * Reduced ] | |||

| * Mild ] (e.g. per ] users, more "]-Vibrations") | |||

| ====United States==== | |||

| === Active ingredients, metabolism, and method of activity === | |||

| Between 1973 and 1978, eleven states decriminalized marijuana.<ref name="tandfonline.com">{{Cite journal |last=Joshua |first=Clark Davis |name-list-style=vanc |date=2015 |title=The business of getting high: head shops, countercultural capitalism, and the marijuana legalization movement |journal=The Sixties |volume=8 |pages=27–49 |doi=10.1080/17541328.2015.1058480 |s2cid=142795620 |hdl-access=free |hdl=11603/7422}}</ref> In 2001, ] reduced marijuana possession to a misdemeanor and since 2012, several other states have decriminalized and even legalized marijuana.<ref name="tandfonline.com" /> | |||

| Of the approximately 400 different chemicals found in ''Cannabis'', the main active ingredient is ] (delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, '''THC'''). THC can degrade to CBL & CBN (other ]), which can make one feel sleepy and disoriented. Different marijuana products have different ratios of these and other cannabinoids. Depending on the ratio, the quality of the "high" will vary. | |||

| In 2018, surveys indicated that almost half of the people in the United States had tried marijuana, 16% had used it in the past year, and 11% had used it in the past month.<ref name="6 facts about marijuana">{{Cite web |date=22 November 2018 |title=6 facts about marijuana |url=https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/11/22/facts-about-marijuana/ |access-date=24 September 2020}}</ref> In 2014, surveys said daily marijuana use amongst US college students had reached its highest level since records began in 1980, rising from 3.5% in 2007 to 5.9% in 2014 and had surpassed daily cigarette use.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Daily marijuana use among college students highest since 1980 |url=https://record.umich.edu/articles/daily-marijuana-use-among-college-students-highest-1980 |website=The University Record}}</ref> | |||

| THC has an effect on the modulation of the ] which may have an effect on malignant cells, but there is insufficient scientific study to determine whether this might promote or limit ]. Cannabinoid receptors are also present in the human ], but there is insufficient scientific study to conclusively determine the effects of cannabis on reproduction. Mild ] to cannabis may be possible in some members of the population. | |||

| In the US, men are over twice as likely to use marijuana as women, and 18{{ndash}}29-year-olds are six times more likely to use as over-65-year-olds.<ref name="gallup.com">{{Cite news |last=McCarthy |first=Justin |date=22 July 2015 |title=More Than Four in 10 Americans Say They Have Tried Marijuana |work=Gallup |url=https://news.gallup.com/poll/184298/four-americans-say-tried-marijuana.aspx}}</ref> In 2015, a record 44% of the US population has tried marijuana in their lifetime, an increase from 38% in 2013 and 33% in 1985.<ref name="gallup.com" /> | |||

| A study has shown that holding cannabis smoke in one's lungs for longer periods did not conclusively increase THC's effects{{ref|PBB}}. | |||

| Marijuana use in the United States is three times above the global average, but in line with other Western democracies. Forty-four percent of American 12th graders have tried the drug at least once, and the typical age of first-use is 16, similar to the typical age of first-use for alcohol but lower than the first-use age for other illicit drugs.<ref name="CaulkinsHawken2012" /> | |||

| === Lethal dose === | |||

| It is generally considered to be impossible to achieve a lethal overdose by smoking cannabis. According to the ], 12th edition, the ], the lethal dose for 50% of tested rats, is 42 ]s per ] of body weight. That is equivalent of a 75 kg (≈165 lb) man ingesting all of the ] in 21 one-gram cigarettes of maximum-potency (15% THC) cannabis buds, assuming no THC was lost through burning or exhalation. For oral consumption, the LD<sub>50</sub> for rats is 1270 mg/kg and 730 mg/kg for males and females, respectively, equivalent to the THC in about a pound of 15% THC cannabis. Only with ] administration — an unheard of method of use — may such a level be even theoretically possible. | |||

| A 2022 ] poll concluded Americans are smoking more marijuana than cigarettes for the first time.<ref name=":4">{{Cite news |title=For the first time, Americans are smoking more marijuana than cigarettes, poll finds |work=cbsnews.com |url=https://www.cbsnews.com/news/marijuana-more-popular-than-cigarettes-in-us-gallup-poll/}}</ref> | |||

| There has only ever been one recorded verdict of fatal overdose due to cannabis, however this finding was found on multiple professional reviews to be "not legitimate". | |||

| == Adverse effects == | |||

| In ], ] of the ] was found dead. The coroner's report stated "Death due to probable cannabis toxicity". It had been reported that Maisey smoked about six joints a day. Mr. Maisey's blood contained 130 ]s per ] (ng/ml) of the THC metabolite THC-COOH. | |||

| {{Further|Effects of cannabis}} | |||

| ===Short-term=== | |||

| The validity of the finding did not stand up well under review. As reported on ] in the '']'', the Federal Health Ministry of ] asked Dr. Rudolf Brenneisen, a professor at the department for clinical research at the ], to review the data of this case. Dr. Brenneisen said that the data of the toxicological analysis and collected by autopsy were "scanty and not conclusive" and that the conclusion "death by cannabis intoxication" was "not legitimate". Additionally, Dr. Franjo Grotenhermen of the nova-Institute in ] said: "A concentration of 130 ng/ml THC-COOH in blood is a moderate concentration, which may be observed some hours after the use of one or two joints. Heavy regular use of cannabis easily results in THC-COOH concentrations of above 500 ng/ml. Many people use much more cannabis than Mr. Maisey did, without any negative consequences." | |||

| ] | |||

| Acute negative effects may include anxiety and panic, impaired attention and memory, an increased risk of psychotic symptoms,{{efn|Psychotic episodes are well-documented and typically resolve within minutes or hours, while symptoms may last longer.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Sativex Oral Mucosal Spray Public Assessment Report. Decentralized Procedure. |url=http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/par/documents/websiteresources/con084961.pdf |access-date=7 May 2015 |publisher=United Kingdom Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency |page=93 |quote=There is clear evidence that recreational cannabis can produce a transient toxic psychosis in larger doses or in susceptible individuals, which is said to characteristically resolve within a week or so of absence (Johns 2001). Transient psychotic episodes as a component of acute intoxication are well-documented (Hall et al 1994)}}</ref> The use of a single joint can temporarily induce some psychiatric symptoms.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Hunt |first=Katie |date=17 March 2020 |title=Single cannabis joint linked with temporary psychiatric symptoms, review finds |work=CNN |url=https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/17/health/cannabis-psychiatric-symptoms-wellness/index.html |access-date=21 March 2020}}</ref>}} the inability to think clearly, and an increased risk of accidents.<ref name="W. Hall, N. Solowij 1611–16">{{Cite journal |vauthors=Hall W, Solowij N |date=November 1998 |title=Adverse effects of cannabis |journal=Lancet |volume=352 |issue=9140 |pages=1611–16 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05021-1 |pmid=9843121 |s2cid=16313727}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last1=Oltmanns |first1=Thomas |title=Abnormal Psychology |last2=Emery |first2=Robert |publisher=Pearson |date=2015 |isbn=978-0205970742 |location=New Jersey |page=294 |name-list-style=vanc}}</ref><ref name="D'Souza">{{Cite journal |vauthors=D'Souza DC, Sewell RA, Ranganathan M |date=October 2009 |title=Cannabis and psychosis/schizophrenia: human studies |journal=European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience |volume=259 |issue=7 |pages=413–31 |doi=10.1007/s00406-009-0024-2 |pmc=2864503 |pmid=19609589}}</ref> Cannabis impairs a person's driving ability, and ] was the illicit drug most frequently found in the blood of drivers who have been involved in vehicle crashes. Those with THC in their system are from three to seven times more likely to be the cause of the accident than those who had not used either cannabis or alcohol, although its role is not necessarily causal because THC stays in the bloodstream for days to weeks after intoxication.<ref name="NIH-2">{{Cite web |last=Abuse |first=National Institute on Drug |title=Does marijuana use affect driving? |url=https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/marijuana/does-marijuana-use-affect-driving |access-date=18 December 2019 |website=www.drugabuse.gov}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Li MC, Brady JE, DiMaggio CJ, Lusardi AR, Tzong KY, Li G |date=4 October 2011 |title=Marijuana use and motor vehicle crashes |journal=Epidemiologic Reviews |volume=34 |issue=1 |pages=65–72 |doi=10.1093/epirev/mxr017 |pmc=3276316 |pmid=21976636}}</ref>{{efn|A 2016 review also found a statistically significant increase in crash risk associated with marijuana use, but noted that this risk was "of low to medium magnitude."<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Rogeberg O, Elvik R |date=August 2016 |title=The effects of cannabis intoxication on motor vehicle collision revisited and revised |url=https://zenodo.org/record/897625 |journal=Addiction |volume=111 |issue=8 |pages=1348–59 |doi=10.1111/add.13347 |pmid=26878835}}</ref> The increase in risk of motor vehicle crash for cannabis use is between 2 and 3 times relative to baseline, whereas that for comparable doses of alcohol is between 6 and 15 times.<ref name="hall2015">{{Cite journal |vauthors=Hall W |date=January 2015 |title=What has research over the past two decades revealed about the adverse health effects of recreational cannabis use? |url=https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:346328/Hall_2014_20ycann_OA_post.pdf |journal=Addiction |volume=110 |issue=1 |pages=19–35 |doi=10.1111/add.12703 |pmid=25287883}}</ref>}} | |||

| == Long-term effects of human consumption == | |||

| ''Main article: ]'' | |||

| Some immediate undesired side effects include a decrease in short-term memory, dry mouth, impaired motor skills, reddening of the eyes,<ref name="HallPacula2003ew">{{Cite book |last1=Hall |first1=Wayne |url=https://archive.org/details/CannabisUseAndDependence |title=Cannabis Use and Dependence: Public Health and Public Policy |last2=Pacula |first2=Rosalie Liccardo |publisher=Cambridge University Press |date=2003 |isbn=978-0-521-80024-2 |page= |url-access=registration |name-list-style=vanc}}</ref> dizziness, feeling tired and vomiting.<ref name=JAMA2015/> Some users may experience an episode of acute ], which usually abates after six hours, but in rare instances, heavy users may find the symptoms continuing for many days.<ref name="Barceloux2012" /> | |||

| There is little conclusive scientific evidence about the long-term effects of human cannabis consumption. The findings of earlier studies purporting to demonstrate the effects of the drug are unreliable and generally regarded as ], as the studies were flawed, with strong bias and poor methodology. The most significant confounding factor is the use of other drugs, including alcohol and tobacco, by test subjects in conjunction with cannabis. When subjects using only cannabis were combined in the same sample with subjects using other drugs as well, researchers could not reach a conclusion as to whether their findings were caused by cannabis, other drugs or the interaction between them. | |||

| Legalization has increased the rates at which children are exposed to cannabis, particularly from edibles. While the toxicity and lethality of THC in children is not known, they are at risk for encephalopathy, hypotension, respiratory depression severe enough to require ventilation, somnolence and coma.<ref name=":13">{{Cite journal |last1=Wong |first1=Kei U. |last2=Baum |first2=Carl R. |date=November 2019 |title=Acute Cannabis Toxicity |journal=Pediatric Emergency Care |language=en-US |volume=35 |issue=11 |pages=799–804 |doi=10.1097/PEC.0000000000001970 |issn=0749-5161 |pmid=31688799 |s2cid=207897219}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Claudet |first1=Isabelle |last2=Le Breton |first2=Mathilde |last3=Bréhin |first3=Camille |last4=Franchitto |first4=Nicolas |date=April 2017 |title=A 10-year review of cannabis exposure in children under 3-years of age: do we need a more global approach? |journal=European Journal of Pediatrics |volume=176 |issue=4 |pages=553–56 |doi=10.1007/s00431-017-2872-5 |issn=1432-1076 |pmid=28210835 |s2cid=11639790}}</ref> | |||

| === Tolerance, withdrawal and dreams=== | |||

| Although use may become habitual, the extent of ] to cannabis is unknown (], 2004). Many animal and human studies conducted since the ] have revealed cannabis withdrawal symptoms in some people after abstinence from heavy use which is usually characterized by a period of anxiousness, ], more vivid and memorable dreams, (''] rebound''), irritability, and diminished appetite after cessation of use. Because cannabis is a ], unlike typical ] or ] drugs, these persistent effects are typically not as severe as those normally associated with physical dependence. | |||

| ===Fatality=== | |||

| THC molecules break down quickly after ingestion, although some components can be detected for a period of up to a month after use, and up to 6 weeks or more in heavy users. Although these components are not proven to have any ongoing physical or mental effects in themselves— THC undergoes ], working its way out of the body slowly over many days, thus reducing the potential to cause withdrawal symptoms. {{ref|Markel}} | |||

| There is no clear evidence for a link between cannabis use and deaths from cardiovascular disease, but a 2019 review noted that it may be an under-reported, contributory factor or direct cause in cases of sudden ], due to the strain it can place on the ]. Some deaths have also been attributed to ].<ref name="drummer">{{Cite journal |vauthors=Drummer OH, Gerostamoulos D, Woodford NW |date=May 2019 |title=Cannabis as a cause of death: A review |journal=Forensic Sci Int |volume=298 |pages=298–306 |doi=10.1016/j.forsciint.2019.03.007 |pmid=30925348 |s2cid=87511682}}</ref> There is an association between cannabis use and suicide, particularly in younger users.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Shamabadi A, Ahmadzade A, Pirahesh K, Hasanzadeh A, Asadigandomani H |title=Suicidality risk after using cannabis and cannabinoids: An umbrella review |journal=Dialogues Clin Neurosci |volume=25 |issue=1 |pages=50–63 |date=December 2023 |pmid=37427882 |pmc=10334849 |doi=10.1080/19585969.2023.2231466 |url=}}</ref> | |||

| A 16-month survey of Oregon and Alaska emergency departments found a report of the death of an adult who had been admitted for acute cannabis toxicity.<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Takakuwa KM, Schears RM |date=February 2021 |title=The emergency department care of the cannabis and synthetic cannabinoid patient: a narrative review |journal=Int J Emerg Med |type=Review |volume=14 |issue=1 |pages=10 |doi=10.1186/s12245-021-00330-3 |pmc=7874647 |pmid=33568074 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| === Long-term effects on the mind and brain === | |||

| <!-- this section needs to be synched with "Health issues and the effects of cannabis", which is more up to date --> | |||

| There is a growing body of medical evidence which may show correlations between cannabis use and ], ], or ]. Some believe that cannabis may trigger latent conditions or be part of a complex coordination of causes, referred to as the ] in ]. On the other hand, many people with pronounced psychological disorders, including schizophrenia, depression, bi-polar and obsessive-compulsive disorder, often ] their illness with cannabis in place of potent main-stream drugs like ], due to cannabis's relatively low side effects and calming physiological effects that alleviate symptoms. | |||

| ===Long-term=== | |||

| One concern with research alleging a link between cannabis use and psychotic illness has been that, while a correlation may be drawn, it is not possible to establish causality. Recent research has attempted to address this concern by studying large groups free of mental illness, to examine the proportion of individuals that already use cannabis who go on to develop mental illnesses{{ref|UKCIA1}}. | |||

| {{main|Long-term effects of cannabis}} | |||

| ] regarding 20 popular recreational drugs. Cannabis was ranked 11th in dependence, 17th in physical harm, and 10th in social harm.<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, Blakemore C |date=March 2007 |title=Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse |journal=Lancet |volume=369 |issue=9566 |pages=1047–53 |doi=10.1016/s0140-6736(07)60464-4 |pmid=17382831 |s2cid=5903121}}</ref>]] | |||

| Further evidence for causality was provided by a 2005 study{{ref|UKCIA2}} showing the existence of a genetic predisposition to cannabis related symptoms of psychosis, by showing correlation between presence of the ], adolescent cannabis use and symptoms of psychotic illness. The study demonstrates that early adolescent cannabis use is a greater predictor for symptoms of adult psychosis among carriers of the gene<!--{{ref|Times}}Times story got the maths wrong one-in-four NOT at risk of psychosis (15%*25%*population=3.75% of population, if heavy adolescent smokers). Need to check 25% COMT figure elsewhere. Newspapers usually get study results wrong-->. The study attempted to control for prior mental illness and other alternative explanations, thereby establishing causality. However, the small sample size<!-- 'small sample size' -- I assume this is what was meant by 'small numbers'. I have changed it in the interest of clarity. Please correct it if my assumption is false-->, symptom screening prior to likely age of symptom onset, and the cohort nature of the study, all call the result into question. This theory is still hotly disputed {{ref|Alternet}}, and further research is ongoing. | |||

| ====Psychological effects==== | |||

| Some claim that extended use of cannabis may help the user reach a higher level of mental consciousness and clarity, expanding the mind and helping individuals become more aware, insightful and intelligent. These claims seem contradictory to the common view of the long-term effects of marijuana use, but this contradiction may simply be indicative of differing interpretations of a common effect. | |||

| A 2015 meta-analysis found that, although a longer period of abstinence was associated with smaller magnitudes of impairment, both retrospective and ] memory were impaired in cannabis users. The authors concluded that some, but not all, of the deficits associated with cannabis use were reversible.<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Schoeler T, Kambeitz J, Behlke I, Murray R, Bhattacharyya S |date=January 2016 |title=The effects of cannabis on memory function in users with and without psychotic disorder: findings from a combined meta-analysis |url=https://epub.ub.uni-muenchen.de/43978/ |journal=Psychological Medicine |volume=46 |issue=1 |pages=177–88 |doi=10.1017/S0033291715001646 |pmid=26353818 |s2cid=23749219}}</ref> A 2012 meta-analysis found that deficits in most domains of cognition persisted beyond the acute period of intoxication, but was not evident in studies where subjects were abstinent for more than 25 days.<ref name="Schreiner 2012">{{Cite journal |vauthors=Schreiner AM, Dunn ME |date=October 2012 |title=Residual effects of cannabis use on neurocognitive performance after prolonged abstinence: a meta-analysis |journal=Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology |volume=20 |issue=5 |pages=420–29 |doi=10.1037/a0029117 |pmid=22731735 |s2cid=207618350 |quote=Therefore, results indicate evidence for small neurocognitive effects that persist after the period of acute intoxication...As hypothesized, the meta-analysis conducted on studies eval- uating users after at least 25 days of abstention found no residual effects on cognitive performance...These results fail to support the idea that heavy cannabis use may result in long-term, persistent effects on neuropsychological functioning.}}</ref> Few high quality studies have been performed on the long-term effects of cannabis on cognition, and the results were generally inconsistent.<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Gonzalez R, Carey C, Grant I |date=November 2002 |title=Nonacute (residual) neuropsychological effects of cannabis use: a qualitative analysis and systematic review |journal=Journal of Clinical Pharmacology |volume=42 |issue=S1 |pages=48S–57S |doi=10.1002/j.1552-4604.2002.tb06003.x |pmid=12412836 |s2cid=37826919}}</ref> Furthermore, ]s of significant findings were generally small.<ref name="Schreiner 2012" /> One review concluded that, although most cognitive faculties were unimpaired by cannabis use, residual deficits occurred in ]s.<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Crean RD, Crane NA, Mason BJ |date=March 2011 |title=An evidence based review of acute and long-term effects of cannabis use on executive cognitive functions |journal=Journal of Addiction Medicine |volume=5 |issue=1 |pages=1–8 |doi=10.1097/ADM.0b013e31820c23fa |pmc=3037578 |pmid=21321675 |quote=Cannabis appears to continue to exert impairing effects in executive functions even after 3 weeks of abstinence and beyond. While basic attentional and working memory abilities are largely restored, the most enduring and detectable deficits are seen in decision-making, concept formation and planning.}}</ref> Impairments in executive functioning are most consistently found in older populations, which may reflect heavier cannabis exposure, or developmental effects associated with adolescent cannabis use.<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Broyd SJ, van Hell HH, Beale C, Yücel M, Solowij N |date=April 2016 |title=Acute and Chronic Effects of Cannabinoids on Human Cognition-A Systematic Review |url=http://ro.uow.edu.au/sspapers/2164 |journal=Biological Psychiatry |volume=79 |issue=7 |pages=557–67 |doi=10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.12.002 |pmid=26858214 |s2cid=9858298}}</ref> One review found three prospective cohort studies that examined the relationship between self-reported cannabis use and ] (IQ). The study following the largest number of heavy cannabis users reported that IQ declined between ages 7–13 and age 38. Poorer school performance and increased incidence of leaving school early were both associated with cannabis use, although a causal relationship was not established.<ref name="Curran2016">{{Cite journal |vauthors=Curran HV, Freeman TP, Mokrysz C, Lewis DA, Morgan CJ, Parsons LH |date=May 2016 |title=Keep off the grass? Cannabis, cognition and addiction |url=http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1489385/1/Curran%2520et%2520al%2520NRN-2016%2520pdf.pdf |journal=Nature Reviews. Neuroscience |volume=17 |issue=5 |pages=293–306 |doi=10.1038/nrn.2016.28 |pmid=27052382 |s2cid=1685727 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170922191943/http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1489385/1/Curran%2520et%2520al%2520NRN-2016%2520pdf.pdf |archive-date=22 September 2017 |access-date=27 December 2018 |hdl-access=free |hdl=10871/24746}}</ref> Cannabis users demonstrated increased activity in task-related brain regions, consistent with reduced processing efficiency.<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Ganzer F, Bröning S, Kraft S, Sack PM, Thomasius R |date=June 2016 |title=Weighing the Evidence: A Systematic Review on Long-Term Neurocognitive Effects of Cannabis Use in Abstinent Adolescents and Adults |journal=Neuropsychology Review |volume=26 |issue=2 |pages=186–222 |doi=10.1007/s11065-016-9316-2 |pmid=27125202 |s2cid=4335379}}</ref> | |||

| A reduced ] is associated with heavy cannabis use, although the relationship is inconsistent and weaker than for tobacco and other substances.<ref name="Gold2017">{{Cite journal |vauthors=Goldenberg M, IsHak WW, Danovitch I |date=January 2017 |title=Quality of life and recreational cannabis use |journal=The American Journal on Addictions |volume=26 |issue=1 |pages=8–25 |doi=10.1111/ajad.12486 |pmid=28000973 |s2cid=40707053}}</ref> The direction of ], however, is unclear.<ref name=Gold2017/> | |||

| === Long-term physical effects of smoking === | |||

| The combustion of any organic material creates irritants and carcinogens, and cannabis is no different. The long-term effects of smoking any substance depends on frequency of use, duration of inhalation, and composition of the smoke. This leads many to assume that the effects of cannabis can be directly compared to other well-known smoking materials such as tobacco. However, direct, volume-for-volume comparisons of the two are probably ] because the chemical composition and methods of usage are not the same. Studies on the subject are inconclusive and have not isolated all the possible factors exacerbating or ameliorating the effects of cannabis user. Here are some of these factors: | |||

| The ] are not clear.<ref name=JAMA2015/> There are concerns surrounding ], risk of addiction, and the risk of ] in young people.<ref name=Borgelt2013/> | |||

| ====Possibly exacerbating factors:==== | |||

| *Studies have pointed out that cannabis produces more tar and burns at a higher temperature than ]. | |||

| *Many cannabis smokers inhale the smoke more deeply and hold it in their lungs for a longer period of time. | |||

| ==== |

====Neuroimaging==== | ||

| Although global abnormalities in ] and ] are not consistently associated with cannabis use,<ref name="Hamp2019">{{Cite journal |vauthors=Hampton WH, Hanik I, Olson IR |date=2019 |title= |journal=Drug and Alcohol Dependence |language=en |volume=197 |issue=4 |pages=288–298 |doi=10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.02.005 |pmc=6440853 |pmid=30875650 |quote=Given that central nervous system is an intricately balanced, complex network of billions of neurons and supporting cells, some might imagine that extrinsic substances could cause irreversible brain damage. Our review paints a less gloomy picture of the substances reviewed, however. Following prolonged abstinence, abusers of alcohol (Pfefferbaum et al., 2014) or opiates (Wang et al., 2011) have white matter microstructure that is not significantly different from nonusers. There was also no evidence that the white matter microstructural changes observed in longitudinal studies of cannabis, nicotine, or cocaine were completely irreparable. It is therefore possible that, at least to some degree, abstinence can reverse effects of substance abuse on white matter. The ability of white matter to “bounce back” very likely depends on the level and duration of abuse, as well as the substance being abused.}}</ref> reduced ] volume is consistently found.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Yücel |first1=M |last2=Lorenzetti |first2=V |last3=Suo |first3=C |last4=Zalesky |first4=A |last5=Fornito |first5=A |last6=Takagi |first6=M J |last7=Lubman |first7=D I |last8=Solowij |first8=N |date=January 2016 |title=Hippocampal harms, protection and recovery following regular cannabis use |journal=Translational Psychiatry |volume=6 |issue=1 |pages=e710– |doi=10.1038/tp.2015.201 |pmc=5068875 |pmid=26756903}}</ref> ] abnormalities are sometimes reported, although findings are inconsistent.<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Rocchetti M, Crescini A, Borgwardt S, Caverzasi E, Politi P, Atakan Z, Fusar-Poli P |date=November 2013 |title=Is cannabis neurotoxic for the healthy brain? A meta-analytical review of structural brain alterations in non-psychotic users |journal=Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences |volume=67 |issue=7 |pages=483–92 |doi=10.1111/pcn.12085 |pmid=24118193 |s2cid=8245635 |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name="Batalla2013">{{Cite journal |vauthors=Batalla A, Bhattacharyya S, Yücel M, Fusar-Poli P, Crippa JA, Nogué S, Torrens M, Pujol J, Farré M, Martin-Santos R |date=2013 |title=Structural and functional imaging studies in chronic cannabis users: a systematic review of adolescent and adult findings |journal=PLOS ONE |volume=8 |issue=2 |pages=e55821 |bibcode=2013PLoSO...855821B |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0055821 |pmc=3563634 |pmid=23390554 |quote=The most consistently reported brain alteration was reduced hippocampal volume which was shown to persist even after several months of abstinence in one study and also to be related to the amount of cannabis use Other frequently reported morphological brain alterations related to chronic cannabis use were reported in the amygdala the cerebellum and the frontal cortex...These findings may be interpreted as reflecting neuroadaptation, perhaps indicating the recruitment of additional regions as a compensatory mechanism to maintain normal cognitive performance in response to chronic cannabis exposure, particularly within the prefrontal cortex area. |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name="Weinstein2016">{{Cite journal |vauthors=Weinstein A, Livny A, Weizman A |date=2016 |title=Brain Imaging Studies on the Cognitive, Pharmacological and Neurobiological Effects of Cannabis in Humans: Evidence from Studies of Adult Users |journal=Current Pharmaceutical Design |volume=22 |issue=42 |pages=6366–79 |doi=10.2174/1381612822666160822151323 |pmid=27549374 |quote=1) The studies reviewed so far demonstrated that chronic cannabis use has been associated with a volume reduction of the hippocampus...3) The overall conclusion arising from these studies is that recent cannabis users may experience subtle neurophysiological deficits while performing on working memory tasks, and that they compensate for these deficits by "working harder" by using additional brain regions to meet the demands of the task.}}</ref> | |||

| * Generally, even a chronic cannabis user does not inhale a daily volume of smoke equal to a significant portion of that of a tobacco smoker. | |||

| * Cannabis smoke does not tend to penetrate to the smaller, peripheral passageways of the lungs, concentrating rather on the larger, central passageways. | |||

| * Industrialized cultivation and preparation of tobacco introduces a variety of ] and ] additives and ]s such as ], ], ]-226, and ]-210. This problem does not pertain to cannabis, the vast majority of which is grown in ]. | |||

| * There is evidence to suggest that cannabinoids present in cannabis may actually serve to protect against cancer. {{ref|NIH}} | |||

| Cannabis use is associated with increased recruitment of task-related areas, such as the ], which is thought to reflect compensatory activity due to reduced processing efficiency.<ref name="Weinstein2016" /><ref name="Batalla2013" /><ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Blest-Hopley G, Giampietro V, Bhattacharyya S |date=May 2018 |title=Residual effects of cannabis use in adolescent and adult brains – A meta-analysis of fMRI studies |url=https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/files/88441182/Residual_effects_of_cannabis_BLEST_HOPLEY_Publishedonline10March2018_GREEN_AAM_CC_BY_NC_ND_.pdf |journal=Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews |volume=88 |pages=26–41 |doi=10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.03.008 |pmid=29535069 |s2cid=4402954 |quote=This may reflect the multitude of cognitive tasks employed by the various studies included in these meta-analyses, all of which involved performing a task thereby requiring the participant to reorient their attention and attempt to solve the problem at hand and suggest that greater engagement of this region indicates less efficient cognitive performance in cannabis users in general, irrespective of their age.}}</ref> Cannabis use is also associated with downregulation of ] receptors. The magnitude of down regulation is associated with cumulative cannabis exposure, and is reversed after one month of abstinence.<ref name="Curran2016" /><ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Parsons LH, Hurd YL |date=October 2015 |title=Endocannabinoid signalling in reward and addiction |journal=Nature Reviews. Neuroscience |volume=16 |issue=10 |pages=579–94 |doi=10.1038/nrn4004 |pmc=4652927 |pmid=26373473}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Zehra A, Burns J, Liu CK, Manza P, Wiers CE, Volkow ND, Wang GJ |date=March 2018 |title=Cannabis Addiction and the Brain: a Review |journal=Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology |volume=13 |issue=4 |pages=438–52 |doi=10.1007/s11481-018-9782-9 |pmc=6223748 |pmid=29556883}}</ref> There is limited evidence that chronic cannabis use can reduce levels of ] metabolites in the human brain.<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Colizzi M, McGuire P, Pertwee RG, Bhattacharyya S |date=May 2016 |title=Effect of cannabis on glutamate signalling in the brain: A systematic review of human and animal evidence |url=https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/effect-of-cannabis-on-glutamate-signalling-in-the-brain-a-systematic-review-of-human-and-animal-evidence(9b3d72d2-d3ae-44a6-b9a5-4c13e9690b9d).html |journal=Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews |volume=64 |pages=359–81 |doi=10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.03.010 |pmid=26987641 |s2cid=24043856}}</ref> | |||

| Some studies have claimed a positive correlation between cannabis use and lung cancer, however, it is possible that this may be due to correlation between cannabis and tobacco use. More study would be needed to separate tobacco use and other factors in order to better understand the potential long-term physiological effects of cannabis use itself. Some recent reports suggest that when the data is properly analyzed, the correlation may in fact be negative.{{ref|Counterpunch}} | |||

| ===Cannabis dependence=== | |||

| == Medicinal use== | |||

| {{Main|Cannabis dependence}} | |||

| {{main_article|]}} | |||

| Medically, cannabis is most often used as an appetite stimulant and pain reliever for certain terminal illnesses such as ] and ]. It is also used to relieve ] and certain neurological illnesses such as ], ] and ]. The medical use of cannabis is politically controversial, but it is sometimes recommended informally by physicians. A synthetic version of the major active chemical in cannabis, THC, is readily available in the form of a pill as the prescription drug ]. THC has also been found to reduce arterial blockages.{{ref|Nature}} A sublingual spray derived from an extract of cannabis has also been approved for treatment of ] in Canada as the prescription drug ] - this drug may now be legally imported into the UK on prescription. Eleven states in the US allow marijuana consumption for medical purposes; however, ] ruled marijuana illegal for any purpose. | |||

| About 9% of those who experiment with marijuana eventually become dependent according to ] criteria.<ref name="NEJM2014" /> A 2013 review estimates daily use is associated with a 10–20% rate of dependence.<ref name="Borgelt2013" /> The highest risk of cannabis dependence is found in those with a history of poor academic achievement, ] in childhood and adolescence, rebelliousness, poor parental relationships, or a parental history of drug and alcohol problems.<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Hall W, Degenhardt L |date=October 2009 |title=Adverse health effects of non-medical cannabis use |journal=Lancet |volume=374 |issue=9698 |pages=1383–91 |doi=10.1016/s0140-6736(09)61037-0 |pmid=19837255 |s2cid=31616272}}</ref> Of daily users, about 50% experience withdrawal upon cessation of use (i.e. are dependent), characterized by sleep problems, irritability, dysphoria, and craving.<ref name="Curran2016" /> Cannabis withdrawal is less severe than withdrawal from alcohol.<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Subbaraman MS |date=2014 |title=Can cannabis be considered a substitute medication for alcohol? |journal=Alcohol and Alcoholism |volume=49 |issue=3 |pages=292–98 |doi=10.1093/alcalc/agt182 |pmc=3992908 |pmid=24402247}}</ref> | |||

| See section ''History'' for information on historic and other medical use. | |||

| According to ] criteria, 9% of those who are exposed to cannabis develop cannabis use disorder, compared to 20% for ], 23% for ] and 68% for ]. Cannabis use disorder in the DSM-V involves a combination of DSM-IV criteria for cannabis abuse and dependence, plus the addition of craving, without the criterion related to legal troubles.<ref name="Curran2016" /> | |||

| == Spiritual use == | |||

| {{main_article|]}} | |||

| Cannabis has a long history of ] use, especially in ], where it has been used by wandering spiritual ]s for centuries. The most famous ] group to use cannabis in a spiritual context is the ], though it is by no means the only group Ex. ]. Some historians and etymologists have claimed that cannabis was used by ancient Jews, early Christians and Muslims of the Sufi order. | |||

| ====Psychiatric==== | |||

| Many individuals also consider their use of cannabis to be spiritual regardless of organized religion, though it is banned in many parts of the world. | |||

| {{See also|Long-term effects of cannabis#Mental health}} | |||

| From a clinical perspective, two significant school of thought exists for psychiatric conditions associated with cannabis (or cannabinoids) use: transient, non-persistent psychotic reactions, and longer-lasting, persistent disorders that resemble schizophrenia. The former is formally known as acute cannabis-associated psychotic symptoms (CAPS).<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Schoeler |first1=Tabea |last2=Baldwin |first2=Jessie R. |last3=Martin |first3=Ellen |last4=Barkhuizen |first4=Wikus |last5=Pingault |first5=Jean-Baptiste |date=2024-06-03 |title=Assessing rates and predictors of cannabis-associated psychotic symptoms across observational, experimental and medical research |journal=Nature Mental Health |volume=2 |issue=7 |language=en |pages=865–876 |doi=10.1038/s44220-024-00261-x |issn=2731-6076|doi-access=free |pmid=39005547 |pmc=11236708 }}</ref> | |||

| == Preparations for human consumption == | |||

| ] | |||

| ] (A), a cannabis ] (B), a small amount of crushed cannabis (C), and a book of cigarette ] (D).]] | |||

| ] ].]] | |||

| ]s, 3/8oz of marijuana, baggies, grinder, rolling papers. In the middle are two British pound coins for size comparison.]] | |||

| Cannabis is prepared for human consumption in several forms: | |||

| At an epidemiological level, a ] exists between cannabis use and increased risk of ] and earlier onset of psychosis.<ref name="Leweke2016rev">{{Cite journal |vauthors=Leweke FM, Mueller JK, Lange B, Rohleder C |date=April 2016 |title=Therapeutic Potential of Cannabinoids in Psychosis |journal=Biological Psychiatry |volume=79 |issue=7 |pages=604–12 |doi=10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.11.018 |pmid=26852073 |s2cid=24160677 |quote=Epidemiological data indicate a strong relationship between cannabis use and psychosis and schizophrenia beyond transient intoxication with an increased risk of any psychotic outcome in individuals who had ever used cannabis}}</ref><ref name="Marconi2016">{{Cite journal |vauthors=Marconi A, Di Forti M, Lewis CM, Murray RM, Vassos E |date=September 2016 |title=Meta-analysis of the Association Between the Level of Cannabis Use and Risk of Psychosis |journal=Schizophrenia Bulletin |volume=42 |issue=5 |pages=1262–69 |doi=10.1093/schbul/sbw003 |pmc=4988731 |pmid=26884547}}</ref><ref name="Moore 2007">{{Cite journal |vauthors=Moore TH, Zammit S, ], Barnes TR, Jones PB, Burke M, Lewis G |date=July 2007 |title=Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review |url=http://orca.cf.ac.uk/619/1/Appendix%201%20%28search%20strategy%29%20Cannabis%20use%20and%20risk%20of%20developing%20psychotic%20or%20affective%20mental%20health%20outcomes%20a%20systematic%20review.pdf |journal=Lancet |volume=370 |issue=9584 |pages=319–28 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61162-3 |pmid=17662880 |s2cid=41595474}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Semple DM, McIntosh AM, Lawrie SM |date=March 2005 |title=Cannabis as a risk factor for psychosis: systematic review |journal=Journal of Psychopharmacology |volume=19 |issue=2 |pages=187–94 |doi=10.1177/0269881105049040 |pmid=15871146 |s2cid=44651274}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Large M, Sharma S, Compton MT, Slade T, Nielssen O |date=June 2011 |title=Cannabis use and earlier onset of psychosis: a systematic meta-analysis |journal=Archives of General Psychiatry |volume=68 |issue=6 |pages=555–61 |doi=10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.5 |pmid=21300939 |doi-access=free}}</ref> Although the epidemiological association is robust, evidence to prove a causal relationship is lacking.<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=McLaren JA, Silins E, Hutchinson D, Mattick RP, Hall W |date=January 2010 |title=Assessing evidence for a causal link between cannabis and psychosis: a review of cohort studies |journal=The International Journal on Drug Policy |volume=21 |issue=1 |pages=10–19 |doi=10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.09.001 |pmid=19783132 |quote=The contentious issue of whether cannabis use can cause serious psychotic disorders that would not otherwise have occurred cannot be answered based on the existing data}}</ref> | |||

| * ''Marijuana'' or ''buds'', the resin gland-rich flowering tops of female plants. | |||

| ** ''Sinsemilla'' or ''sensemillia'', flowering tops which are free of ]s as a result of being grown in a ]-free environment. Since no plant energy can go into seed formation, this version is higher in psychoactive components. | |||

| * '']'' or ''kif'', a powder containing the resin glands (glandular ]s, often incorrectly called "crystals" or "pollen"). It is produced by sifting marijuana and leaves. | |||

| * '']'', a concentrated resin made from pressing ''kif'' into blocks. | |||

| * ''Charas'', produced by hand-rubbing the resin from the resin gland-rich parts of the plant. Often thin dark rectangular pieces. | |||

| * '']'', prepared by the wet grinding of the leaves of the plant and used as a drink. | |||

| * ''Hash oil'', resulting from ] or ] of THC-rich parts of the plant. | |||

| * Minimally potent leaves and detritus, called ''shake, bush'' or ''leaf''. | |||

| Cannabis may also increase the risk of depression, but insufficient research has been performed to draw a conclusion.<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Lev-Ran S, Roerecke M, Le Foll B, George TP, McKenzie K, Rehm J |date=March 2014 |title=The association between cannabis use and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies |journal=Psychological Medicine |volume=44 |issue=4 |pages=797–810 |doi=10.1017/S0033291713001438 |pmid=23795762 |s2cid=36763290}}</ref><ref name="Moore 2007" /> Cannabis use is associated with increased risk of anxiety disorders, although causality has not been established.<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Kedzior KK, Laeber LT |date=May 2014 |title=A positive association between anxiety disorders and cannabis use or cannabis use disorders in the general population – a meta-analysis of 31 studies |journal=BMC Psychiatry |volume=14 |pages=136 |doi=10.1186/1471-244X-14-136 |pmc=4032500 |pmid=24884989 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| There are also three sub-species of Cannabis. These include ''Cannabis sativa'', ''Cannabis indica'', and ''Cannabis ruderalis'', the latter containing much less THC and generally not used as a psychoactive. They differ in their appearance and the highs they produce. There have also been claims to a fourth sub-species of cannabis, which has been nicknamed "Cannabis Rasta". It is not yet a formally accepted sub-species and similar to "Cannabis Sativa" with regards to psychoactivity. | |||

| A review in 2019 found that research was insufficient to determine the safety and efficacy of using cannabis to treat schizophrenia, psychosis, or other ]s.<ref name="black">{{Cite journal |last1=Black |first1=Nicola |last2=Stockings |first2=Emily |last3=Campbell |first3=Gabrielle |last4=Tran |first4=Lucy T. |last5=Zagic |first5=Dino |last6=Hall |first6=Wayne D. |last7=Farrell |first7=Michael |last8=Degenhardt |first8=Louisa |date=December 2019 |title=Cannabinoids for the treatment of mental disorders and symptoms of mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis |journal=The Lancet. Psychiatry |volume=6 |issue=12 |pages=995–1010 |doi=10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30401-8 |pmc=6949116 |pmid=31672337}}</ref><ref name="mayo">{{Cite journal |last1=VanDolah |first1=Harrison J. |last2=Bauer |first2=Brent A. |last3=Mauck |first3=Karen F. |date=September 2019 |title=Clinicians' Guide to Cannabidiol and Hemp Oils |journal=Mayo Clinic Proceedings |volume=94 |issue=9 |pages=1840–51 |doi=10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.01.003 |pmid=31447137 |doi-access=free}}</ref> Another found that cannabis during adolescence was associated with an increased risk of developing depression and suicidal behavior later in life, while finding no effect on anxiety.<ref name="Gobbi">{{Cite journal |last1=Gobbi |first1=Gabriella |author-link=Gabriella Gobbi |last2=Atkin |first2=Tobias |last3=Zytynski |first3=Tomasz |last4=Wang |first4=Shouao |last5=Askari |first5=Sorayya |last6=Boruff |first6=Jill |last7=Ware |first7=Mark |last8=Marmorstein |first8=Naomi |last9=Cipriani |first9=Andrea |last10=Dendukuri |first10=Nandini |last11=Mayo |first11=Nancy |date=13 February 2019 |title=Cannabis Use in Adolescence and Risk of Depression, Anxiety, and Suicidality in Young Adulthood |journal=JAMA Psychiatry |volume=76 |issue=4 |pages=426–34 |doi=10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4500 |pmc=6450286 |pmid=30758486}}</ref> | |||

| === Smoking === | |||

| The most common method of cannabis consumption is by smoking a ''hit'' through one of several classes of devices: | |||

| ====Physical==== | |||

| # By rolling it up, either manually or with a ], into a cigarette, often called a '']'' or ''joint'', with thin '']'', or into a cigar, often called a ], with wrapper either obtained by removing the tobacco from the inside of a standard cigar or purchased as a "blunt wrap". In such preparation, ] or other smokable material are sometimes combined (mulled) into a single roll. Users may also purchase flavored papers or blunt wraps which both mask the scent of the cannabis and provide for a tastier smoke. | |||