| Revision as of 15:31, 17 February 2008 view sourceMy.life.is.muzik... (talk | contribs)91 edits Adding information .← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 18:58, 21 December 2024 view source GreenC bot (talk | contribs)Bots2,547,810 edits Reformat 1 archive link. Wayback Medic 2.5 per WP:USURPURL and JUDI batch #20 | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Country in Southeast Europe}} | |||

| <!-- | |||

| {{Redirect|Kosova|other uses|Kosovo (disambiguation)|and|Kosova (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef}} | |||

| {{pp-move}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=December 2019}} | |||

| {{Infobox country | |||

| | conventional_long_name = Republic of Kosovo | |||

| | native_name = {{unbulleted list|item_style=font-size:85%;|{{native name|sq|Republika e Kosovës}}|{{lang|sr-Cyrl|Република Косово}} / {{native name|sr-Latn|Republika Kosovo}}}} | |||

| | common_name = Kosovo | |||

| | image_flag = Flag of Kosovo.svg | |||

| | image_coat = Coat of arms of Kosovo.svg | |||

| | symbol = Emblem of Kosovo | |||

| | symbol_type = Emblem | |||

| | image_map = Europe-Republic of Kosovo.svg | |||

| | map_caption = Location of Kosovo (green) | |||

| | national_motto = | |||

| | national_anthem = Himni i Republikës së Kosovës<br />"]"{{center|]}} | |||

| | official_languages = ]<br />]<ref name="bein12"/> | |||

| | languages2_type = Regional languages | |||

| | languages2 = {{hlist|]|]<ref>{{cite web|title=Municipal language compliance in Kosovo|url=https://www.osce.org/kosovo/120010?download=true|publisher=OSCE Minsk Group|quote=Turkish language is currently official in Prizren and Mamuşa/Mamushë/Mamuša municipalities. In 2007 and 2008, the municipalities of Gjilan/Gnjilane, southern Mitrovicë/Mitrovica, Prishtinë/Priština and Vushtrri/Vučitrn also recognized Turkish as a language in official use.|access-date=17 February 2021|archive-date=5 March 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210305035807/http://www.osce.org/kosovo/120010?download=true|url-status=live}}</ref>|]}} | |||

| | ethnic_groups_ref = <ref name="ReKos2024"/> | |||

| | ethnic_groups_year = 2024 | |||

| | ethnic_groups = {{unbulleted list|91.76% ]|2.31% ]|1.69% ]|1.22% ]|1.02% ]|2.0% others}} | |||

| | demonym = {{unbulleted list|Kosovar, Kosovan}} | |||

| | capital = {{nowrap|]}}<sup>a</sup> | |||

| | status = {{unbulletedlist|] of the ].<ref>{{cite news|newspaper=The Jerusalem Post|date=1 February 2021|title=Israel's ties with Kosovo: What new opportunities await?|url=https://www.jpost.com/opinion/israels-ties-with-kosovo-what-new-opportunities-await-657476|access-date=8 February 2021|archive-date=7 February 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210207154341/https://www.jpost.com/opinion/israels-ties-with-kosovo-what-new-opportunities-await-657476|url-status=live}}</ref>|Claimed by ] as the ]}} | |||

| | coordinates = {{Coord|42|40|N|21|10|E|type:city(1,900,000)}} | |||

| | largest_city = capital | |||

| | government_type = ] | |||

| | leader_title1 = ] | |||

| | leader_name1 = ] | |||

| | leader_title2 = ] | |||

| | leader_name2 = ] | |||

| | leader_title3 = ] | |||

| | leader_name3 = ] | |||

| | legislature = ] | |||

| | area_km2 = 10,887<ref>{{cite web |url = https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-18328859 |title = Kosovo profile |date = 28 Jun 2023 |website = BBC |access-date = 12 Sep 2023 |archive-date = 27 September 2023 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20230927133550/https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-18328859 |url-status = live }}</ref> | |||

| | area_rank = | |||

| | area_sq_mi = 4,212 | |||

| | percent_water = 1.0<ref>{{cite web|title=Water percentage in Kosovo (Facts about Kosovo; 2011 Agriculture Statistics)|url=http://ask.rks-gov.net/|publisher=Kosovo Agency of Statistics, KAS|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170829035712/http://ask.rks-gov.net/|archive-date=29 August 2017}}</ref> | |||

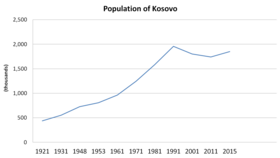

| | population_census = {{DecreaseNeutral}} 1,585,566<ref name="ReKos2024">*Total - pg.32; Ethnic - pg.44; Religion - pg.46*{{cite web |url=https://askapi.rks-gov.net/Custom/31bc24d2-45e4-4eb5-a567-405f4bdd197f.pdf |title=ReKos 2024 |publisher=] (ASK) |website=www.ask.rks-gov.net |language=Albanian |date=19 December 2024 |access-date=20 December 2024}}</ref> | |||

| | population_estimate_rank = | |||

| | population_estimate_year = | |||

| | population_census_year = 2024 | |||

| | population_density_km2 = 146 | |||

| | population_density_sq_mi = 378 | |||

| | GDP_PPP = {{increase}} $29.723 billion<ref name="IMFWEO.XK">{{cite web |url=https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2024/October/weo-report?c=967,&s=NGDPD,PPPGDP,NGDPDPC,PPPPC,&sy=2022&ey=2029&ssm=0&scsm=1&scc=0&ssd=1&ssc=0&sic=0&sort=country&ds=.&br=1 |title=World Economic Outlook Database, October 2024 Edition. (Kosovo) |publisher=] |website=www.imf.org |date=22 October 2024 |access-date=20 December 2024}}</ref> | |||

| | GDP_PPP_year = 2024 | |||

| | GDP_PPP_rank = 148th | |||

| | GDP_PPP_per_capita = {{increase}} $16,851<ref name="IMFWEO.XK" /> | |||

| | GDP_PPP_per_capita_rank = 100th | |||

| | GDP_nominal = {{increase}} $11.172 billion<ref name="IMFWEO.XK" /> | |||

| | GDP_nominal_year = 2024 | |||

| | GDP_nominal_rank = 155th | |||

| | GDP_nominal_per_capita = {{increase}} $6,333<ref name="IMFWEO.XK" /> | |||

| | GDP_nominal_per_capita_rank = 104th | |||

| | Gini_year = 2017 | |||

| | Gini_change = increase | |||

| | Gini = 29.0 | |||

| | Gini_ref = <ref>{{cite web |publisher=] |title=GINI index (World Bank estimate)–Kosovo |url=https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?locations=XK&name_desc=false |access-date=24 September 2020 |archive-date=24 January 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190124203818/https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?locations=XK&name_desc=false |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | HDI_year = 2021 | |||

| | HDI_change = increase | |||

| | HDI = 0.762 | |||

| | HDI_ref = <ref>{{Cite web|title=Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab|url=https://globaldatalab.org/shdi/shdi/XKO/?levels=1%2B4&interpolation=1&extrapolation=0&nearest_real=0&years=2019|website=hdi.globaldatalab.org|language=en|archive-date=29 November 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221129215423/https://globaldatalab.org/shdi/shdi/XKO/?levels=1%2B4&interpolation=1&extrapolation=0&nearest_real=0&years=2019|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | HDI_rank = | |||

| | currency = ] (])<sup>b</sup> | |||

| | currency_code = EUR | |||

| | time_zone = ] | |||

| | utc_offset = +1 | |||

| | time_zone_DST = ] | |||

| | utc_offset_DST = +2 | |||

| | drives_on = ] | |||

| | calling_code = ] | |||

| | iso3166code = XK | |||

| | cctld = ]<sup>c</sup> (proposed) | |||

| | established_event1 = ] | |||

| | established_date1 = 1455 | |||

| | established_event2 = ] | |||

| | established_date2 = 1877 | |||

| | established_event3 = ] | |||

| | established_date3 = 1913 | |||

| | established_event4 = ] | |||

| | established_date4 = 31 January 1946 | |||

| | established_event5 = ] | |||

| | established_date5 = 2 July 1990 | |||

| | established_event6 = ] | |||

| | established_date6 = 9 June 1999 | |||

| | established_event7 = ] | |||

| | established_date7 = 10 June 1999 | |||

| | established_event8 = ] | |||

| | established_date8 = 17 February 2008 | |||

| | established_event9 = ] | |||

| | established_date9 = 10 September 2012 | |||

| | established_event10 = ] | |||

| | established_date10 = 19 April 2013 | |||

| | footnote_a = ] is the capital of Kosovo and its ].<ref>{{cite act |date=9 April 2008 |article= 13 |legislature=] |title=Constitution of the Republic of Kosovo|page= |url=http://old.kuvendikosoves.org/common/docs/Constitution_of_the_Republic_of_Kosovo_with_amend.I-XXV_2017.pdf}}</ref><ref name="capital">{{cite web |publisher=Gazeta Zyrtare e Republikës së Kosovës |title=Ligji Nr. 06/L-012 për Kryeqytetin e Republikës së Kosovës, Prishtinën |url=https://gzk.rks-gov.net/ActDetail.aspx?ActID=16506 |access-date=24 September 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200924130927/https://gzk.rks-gov.net/ActDetail.aspx?ActID=16506 |archive-date=24 September 2020 |language=sq |date=6 June 2018}}</ref> A separate law recognises ] as the ''historic capital'' of Kosovo.<ref name="capital" /> | |||

| | footnote_b = The Euro is the official currency in Kosovo even though Kosovo is not a formal member of the ].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/euro/use-euro/euro-outside-euro-area_en |title=The euro outside the euro area |work=Economy and Finance |publisher=European Commission |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240128215012/https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/euro/use-euro/euro-outside-euro-area_en |archive-date=2024-01-28 |access-date=2024-01-28 }}</ref><ref>{{cite act |date=9 April 2008 |article= 11 |legislature=] |title=Constitution of the Republic of Kosovo|page= |url=http://old.kuvendikosoves.org/common/docs/Constitution_of_the_Republic_of_Kosovo_with_amend.I-XXV_2017.pdf}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=https://telegrafi.com/perfundon-periudha-transitore-nga-sot-euro-valuta-e-vetme-per-transaksione-ne-kosove/ |title=Përfundon periudha transitore: Nga sot, euro valuta e vetme për transaksione në Kosovë |language=Albanian |trans-title=The transitory period is over: from today euro is the only currency for transactions in Kosovo |work=] |location=Prishtina |publisher=] |date=2024-05-12 |access-date=2024-05-13 |archive-date=13 May 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240513142936/https://telegrafi.com/perfundon-periudha-transitore-nga-sot-euro-valuta-e-vetme-per-transaksione-ne-kosove/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| | footnote_c = XK is a "user assigned" ISO 3166 code not designated by the standard, but used by the ], Switzerland, the ] and other organisations. However, ] remains in use. | |||

| | today = | |||

| | date_format = ] | |||

| | linking_name = | |||

| | religion = {{unbulleted list|93.49% ]|2.31% ]|1.75% ]|0.5% ]|0.45% others|1.5% undeclared}} | |||

| | religion_year = 2024 | |||

| | religion_ref = <ref name="ReKos2024"/> | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Kosovo''',{{efn|{{IPAc-en|ˈ|k|ɒ|s|ə|v|əʊ}} {{respell|KOSS|ə|voh}}; {{langx|sq|Kosova}} {{IPA|sq|kɔˈsɔva|}}; {{lang-sr-Cyrl|Косово}} {{IPA|sr|kôsovo|}}}} officially the '''Republic of Kosovo''',{{efn|{{langx|sq|Republika e Kosovës|links=no}}; {{langx|sr|Република Косово|Republika Kosovo|links=no}}}} is a country in ] with ]. It is bordered by ] to the southwest, ] to the west, ] to the north and east, and ] to the southeast. It covers an area of {{Convert|10,887|km2|abbr=on}} and has a population of approximately 1.6 million. Kosovo has a varied terrain, with high plains along with rolling hills and ], some of which have an altitude over {{Convert|2500|m|abbr=on}}. Its climate is mainly ] with some ] and ] influences.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Kosovo Guidebook |url=https://eca.state.gov/files/bureau/kosovo-guidebook.pdf |website=eca.state.gov |access-date=20 September 2024}}</ref> Kosovo's capital and ] is ]; other major cities and ]s include ], ], ] and ].<ref>{{cite web |title=Population and housing census in Kosovo preliminary results - July 2024 |url=https://askapi.rks-gov.net/Custom/1d268e37-5934-4bd5-bbd1-34a9965cff92.pdf |access-date=21 July 2024}}</ref> | |||

| Please be very careful in editing the introduction of this article. The Arbitration Committee has placed this article on probation. While this occurred in 2006, it was never lifted; thus, THIS PAGE IS STILL UNDER PROBATION. If any editor makes disruptive edits, they may be banned by an administrator from this and related articles, or other reasonably related pages. See the talk page for more information. Thank you. | |||

| The ] tribe emerged in Kosovo and established the ] in the 4th century BCE. It was later annexed by the ] in the 1st century BCE. The territory remained in the ], facing Slavic migrations in the 6th and 7th centuries CE. Control shifted between the Byzantines and the ]. In the 13th century, Kosovo became integral to the ] and the establishment of the ] ] in the Balkans in the late 14th and 15th centuries led to the decline and ]; the ] of 1389, in which a Serbian-led coalition of various ethnicities fought against the Ottoman Empire, is considered one of the defining moments. | |||

| --> | |||

| {{current}} | |||

| Various dynasties, mainly the ], governed Kosovo for much of the period after the battle. The ] fully conquered Kosovo after the ], ruling for nearly five centuries until 1912. Kosovo was the center of the ] and experienced the ] and ]. After the ] (1912–1913), it was ceded to the ], and after World War II, it became an ] within ]. Tensions between Kosovo's Albanian and ] communities simmered during the 20th century and occasionally erupted into major violence, culminating in the ] of 1998 and 1999, which resulted in the Yugoslav army's withdrawal and the establishment of the ]. | |||

| {{otheruses}} | |||

| {{pp-semi|small=yes}} | |||

| Kosovo ] ] from ] on 17 February 2008<ref name="icj2020">{{cite web |publisher=] (ICJ) |title=Accordance with International Law of the Unilateral Declaration of Independence in Respect of Kosovo |url=https://www.icj-cij.org/files/case-related/141/141-20100722-ADV-01-00-EN.pdf |access-date=24 September 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200924140658/https://www.icj-cij.org/files/case-related/141/141-20100722-ADV-01-00-EN.pdf |archive-date=24 September 2020 |date=22 July 2010}}</ref> and has since gained diplomatic recognition as a ] by ] of the ]. Serbia does not officially recognise Kosovo as a sovereign state and continues to claim it as its constituent ], but it accepts the governing authority of the Kosovo institutions as part of the ].<ref name=foreignaffairs>{{cite magazine |first=Nikolas K. |last=Gvosdev |title=Kosovo and Serbia Make a Deal |url=https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/kosovo/2013-04-24/kosovo-and-serbia-make-deal |date=24 April 2013 |magazine=Foreign Affairs |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160305041508/https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/kosovo/2013-04-24/kosovo-and-serbia-make-deal |archive-date=5 March 2016}}</ref> | |||

| {{Infobox Country | |||

| |native_name = {{nowrap|{{lang|sq|''Republika e Kosovës''}}<br>{{lang|sr-Cyrl|Република Косово}} / {{lang|sr-Lat|''Republika Kosovo''}}}} | |||

| Kosovo is a developing country, with an ]. It has experienced solid ] over the last decade as measured by international financial institutions since the onset of the ]. Kosovo is a member of the ], ], ], ], and the ], and has applied for membership in the ], ], and ], and for observer status in the ]. In December 2022, Kosovo filed ] to become a member of the ].<ref name="dw10"/> | |||

| |conventional_long_name = Republic of Kosovo | |||

| |common_name = Kosovo | |||

| == Etymology == | |||

| |image_flag = Flag of Kosovo.svg | |||

| {{Main|Names of Kosovo}} | |||

| |image_coat = Coat of arms of Kosovo.svg | |||

| |image_map = The position of Kosovo within Serbia.PNG | |||

| The name ''Kosovo'' is of ] origin. {{lang|sr-Latn|Kosovo}} ({{lang-sr-Cyrl|Косово|links=no}}) is the ] neuter possessive adjective of {{lang|sr-Latn|kos}} ({{lang|sr-Cyrl|кос}}), ']',<ref>{{cite book |last1=Judah |first1=Tim |title=Kosovo: What Everyone Needs to Know |date=2008 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=9780195373455 |page=31 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UGwSDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA31 |access-date=15 August 2023 |archive-date=15 August 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230815174228/https://books.google.com/books?id=UGwSDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA31 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |editor1-last=Manić |editor1-first=Emilija |editor2-last=Nikitović |editor2-first=Vladimir |editor3-last=Djurović |editor3-first=Predrag |title=The Geography of Serbia: Nature, People, Economy |date=2021 |publisher=Springer |isbn=9783030747015 |page=47 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BPJQEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA47 |access-date=15 August 2023 |archive-date=15 August 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230815174228/https://books.google.com/books?id=BPJQEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA47 |url-status=live }}</ref> an ] for {{lang|sr-Latn|Kosovo Polje}}, 'Blackbird Field', the name of ] situated in the eastern half of today's Kosovo and the site of the 1389 ].<ref name="Everett-Heath2000">{{cite book |author=J. Everett-Heath |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uK2HDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA373 |title=Place Names of the World - Europe: Historical Context, Meanings and Changes |date=1 August 2000 |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan UK |isbn=978-0-230-28673-3 |pages=373– |access-date=13 August 2023 |archive-date=30 September 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230930143730/https://books.google.com/books?id=uK2HDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA373#v=onepage&q&f=false |url-status=live }}</ref> The name of the karst field was for the first time applied to a wider area when the ] was created in 1877. | |||

| |map_caption = |map_caption = Location of Kosovo (dark orange) and Serbia (light orange)<br/>on the ] | |||

| |national_motto = | |||

| The entire territory that corresponds to today's country is commonly referred to in English simply as ''Kosovo'' and in ] as {{lang|sq|Kosova}} (]) or {{lang|sq|Kosovë}} (indefinite form, {{IPA|sq|kɔˈsɔvə|pron}}). In Serbia, a formal distinction is made between the eastern and western areas of the country; the term {{lang|sr-Latn|Kosovo}} ({{lang|sr-Cyrl|Косово}}) is used for the eastern part of Kosovo centred on the historical ], while the western part of the territory of Kosovo is called '']'' ({{Langx|sq|Dukagjin|links=no}}). Thus, in Serbian the entire area of Kosovo is referred to as ''Kosovo and Metohija''.<ref name="constitution-serbia">{{cite web|url=http://www.parlament.gov.rs/content/eng/akta/ustav/ustav_ceo.asp|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101127021637/http://www.parlament.gov.rs/content/eng/akta/ustav/ustav_ceo.asp|archive-date=27 November 2010 |title=Constitution of the Republic of Serbia |publisher=Parlament.gov.rs |access-date=2 January 2011}}</ref> | |||

| |national_anthem = | |||

| |official_languages = ], ], ] | |||

| Dukagjini or Dukagjini plateau (Albanian: 'Rrafshi i Dukagjinit') is an alternative name for Western Kosovo, having been in use since the 15th-16th century as part of the ] of ] with its capital ], and is named after the medieval Albanian ].<ref name="Drançolli">{{cite web |last1=Drançolli |first1=Jahja |title=Illyrian-Albanian Continuity the Areal of Kosova |url=https://www.academia.edu/9304559 |website=academia.edu |access-date=11 February 2024 |archive-date=20 November 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231120230138/https://www.academia.edu/9304559 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| |ethnic_groups = 92% ]<br/>{{spaces|2}}5.3% ]<br/>{{spaces|2}}2.7% others <small></small> | |||

| |ethnic_groups_year = 2007 | |||

| === Modern usage === | |||

| |capital = {{nowrap|]}} | |||

| |latd= |latm= |latNS= |longd= |longm= |longEW= | |||

| Some Albanians also prefer to refer to Kosovo as ], the name of an ancient kingdom and later ], which covered the territory of modern-day Kosovo. The name is derived from the ancient tribe of the '']'', which is considered be related to the Proto-Albanian term ''dardā'', which means "pear" (Modern Albanian: {{Lang|sq|dardhë}}).<ref name="Everett-Heath2000" /><ref>Albanian Etymological Dictionary, V.Orel, Koninklijke Brill, Leiden Boston Köln 1998, p. 56</ref> The former Kosovo President ] had been an enthusiastic backer of a "Dardanian" identity, and the Kosovar presidential flag and seal refer to this national identity. However, the name "Kosova" remains more widely used among the Albanian population. The flag of Dardania remains in use as the official ] and is heavily featured in the institution of the presidency of the country. | |||

| |largest_city = capital | |||

| |government_type = Interim{{smallsup|1}} | |||

| The official conventional long name, as defined by the ], is ''Republic of Kosovo''.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Kosovo's Constitution of 2008 (with Amendments through 2016) |url=https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Kosovo_2016.pdf |via=constituteproject.org |access-date=2 November 2019 |archive-date=2 November 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191102154102/https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Kosovo_2016.pdf |url-status=live}}</ref> Additionally, as a result of an ] in talks mediated by the European Union, Kosovo has participated in some international forums and organisations under the title "Kosovo*" with a footnote stating, "This designation is without prejudice to positions on status, and is in line with UNSC 1244 and the ICJ Opinion on the Kosovo declaration of independence". This arrangement, which has been dubbed the "asterisk agreement", was agreed in an 11-point arrangement on 24 February 2012.<ref>{{cite news|title=Agreement on regional representation of Kosovo|url=http://www.b92.net/eng/insight/pressroom.php?yyyy=2012&mm=02&nav_id=78973|access-date=11 November 2014|publisher=B92|date=25 February 2012|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141111162752/http://www.b92.net/eng/insight/pressroom.php?yyyy=2012&mm=02&nav_id=78973|archive-date=11 November 2014}}</ref> | |||

| |leader_title1 = {{nowrap|Special Representative of}} {{nowrap|the Secretary-General}} | |||

| |leader_name1 = <br/>] | |||

| == History == | |||

| |leader_title2 = Transitional ] | |||

| {{For timeline|Timeline of Kosovo history}} | |||

| |leader_name2 = ] | |||

| {{Main|History of Kosovo}} | |||

| |leader_title3 = Transitional ] | |||

| |leader_name3 = ] | |||

| === Ancient history === | |||

| |sovereignty_type = ]{{smallsup|2}} | |||

| {{See also|Archaeology of Kosovo|Copper, Bronze and Iron Age sites in Kosovo}} | |||

| |sovereignty_note = from ] | |||

| {{Further|Illyrians|Dardania (Roman province)|l2=Dardania}} | |||

| |established_event1 = Declared | |||

| |established_date1 = ] ] | |||

| The strategic position including the abundant natural resources were favorable for the development of human settlements in Kosovo, as is highlighted by the hundreds of archaeological sites identified throughout its territory.<ref name=SchermerShukriu>{{cite book |last1=Schermer |first1=Shirley |last2=Shukriu |first2=Edi |last3=Deskaj |first3=Sylvia |editor1-last=Marquez-Grant |editor1-first=Nicholas |editor2-last=Fibiger |editor2-first=Linda |title=The Routledge Handbook of Archaeological Human Remains and Legislation: An International Guide to Laws and Practice in the Excavation and Treatment of Archaeological Human Remains |date=2011 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn=978-1136879562 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Lzi4N-74QmAC |page=235 |access-date=20 September 2020 |archive-date=4 February 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220204134209/https://books.google.com/books?id=Lzi4N-74QmAC |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| |area_rank = | |||

| |area_magnitude = 1 E10 | |||

| ] is one of the most significant archaeological artifacts of Kosovo and has been adopted as the symbol of ].]] | |||

| |area_km2 = 10,887 | |||

| |area_sq_mi = 4,203 | |||

| Since 2000, the increase in archaeological expeditions has revealed many, previously unknown sites. The earliest documented traces in Kosovo are associated to the ]; namely, indications that cave dwellings might have existed, such as Radivojce Cave near the source of the ], Grnčar Cave in ] and the Dema and Karamakaz Caves in the ]. | |||

| |percent_water = n/a | |||

| |population_estimate = 2.2 million | |||

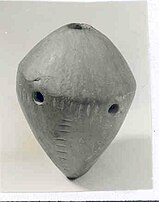

| The earliest archaeological evidence of organised settlement, which have been found in Kosovo, belong to the ] ] and ] cultures.<ref name="Berisha">{{cite web |last=Berisha |first=Milot |title=Archaeological Guide of Kosovo |url=https://www.mkrs-ks.org/repository/docs/drafti_i_guides_-anglisht_final.pdf |year=2012 |publisher=Ministry of Culture of Kosovo |pages=17–18 |access-date=20 September 2020 |archive-date=17 April 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190417092446/https://www.mkrs-ks.org/repository/docs/drafti_i_guides_-anglisht_final.pdf |url-status=live}}</ref> ] and ] are important sites of the ] with the rock art paintings at Mrrizi i Kobajës near ] being the first find of prehistoric art in Kosovo.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Shukriu |first1=Edi |author-link1=Edi Shukriu |title=Spirals of the prehistoric open rock painting from Kosova |journal=Proceedings of the XV World Congress of the International Union for Prehistoric and Protohistoric Sciences |date=2006 |volume=35 |url=https://www.academia.edu/1787676 |page=59 |access-date=20 September 2020 |archive-date=14 September 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210914015031/https://www.academia.edu/1787676 |url-status=live}}</ref> Amongst the finds of excavations in Neolithic Runik is a baked-clay ], which is the first musical instrument recorded in Kosovo.<ref name="Berisha"/> | |||

| |population_estimate_rank = | |||

| |population_estimate_year = 2005 | |||

| ] in the 3rd century BCE.]] | |||

| |population_census = | |||

| |population_census_year = | |||

| The first archaeological expedition in Kosovo was organised by the Austro-Hungarian army during the ] in the ] ] burial grounds of Nepërbishti within the ].<ref name=SchermerShukriu/> | |||

| |population_density_km2 = 220 | |||

| |population_density_sq_mi = 500 | |||

| The beginning of the ] coincides with the presence of ] burial grounds in western Kosovo, like the site of ].<ref name="SchermerShukriu"/> | |||

| |population_density_rank = | |||

| |currency = ] (€){{smallsup|3}} | |||

| The ] were the most important ] tribe in the region of Kosovo. A wide area which consists of Kosovo, parts of Northern Macedonia and eastern Serbia was named ] after them in classical antiquity, reaching to the ] contact zone in the east. In archaeological research, Illyrian names are predominant in western Dardania, while Thracian names are mostly found in eastern Dardania. | |||

| |currency_code = EUR | |||

| |time_zone = | |||

| Thracian names are absent in western Dardania, while some Illyrian names appear in the eastern parts. Thus, their identification as either an ] or ] tribe has been a subject of debate, the ethnolinguistic relationship between the two groups being largely uncertain and debated itself as well. The correspondence of Illyrian names, including those of the ruling elite, in Dardania with those of the southern Illyrians suggests a thracianization of parts of Dardania.<ref>{{cite book|last=Wilkes|first=John|title=The Illyrians|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4Nv6SPRKqs8C|year=1996|orig-year=1992|publisher=Wiley|isbn=978-0-631-19807-9|page=85|access-date=20 September 2020|archive-date=2 May 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200502085653/https://books.google.com/books?id=4Nv6SPRKqs8C|url-status=live}}</ref> The Dardani retained an individuality and continued to maintain social independence after Roman conquest, playing an important role in the formation of new groupings in the Roman era.<ref name="Papazoglou">{{Cite book|last=Papazoglu|first=Fanula|author-link=Fanula Papazoglu|title=The Central Balkan Tribes in pre-Roman Times: Triballi, Autariatae, Dardanians, Scordisci and Moesians|year=1978|location=Amsterdam|publisher=Hakkert|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Up4JAQAAIAAJ|page=131|isbn=9789025607937|access-date=27 September 2020|archive-date=11 April 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210411011011/https://books.google.com/books?id=Up4JAQAAIAAJ|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| |utc_offset = +1 | |||

| |time_zone_DST = | |||

| ==== Roman period ==== | |||

| |utc_offset_DST = | |||

| {{See also|Roman heritage in Kosovo}} | |||

| |cctld = ''none assigned'' | |||

| |footnote1 = ]<br/>] | |||

| During Roman rule, Kosovo was part of two provinces, with its western part being part of ], and the vast majority of its modern territory belonging to ]. Praevalitana and the rest of Illyria was conquered by the ] in 168 BC. On the other hand, Dardania maintained its independence until the year 28 BC, when the Romans, under ], annexed it into their Republic.<ref>{{cite book|last=Errington|first=Robert Malcolm|author-link=Robert Malcolm Errington|title=A History of Macedonia |location=Berkeley|publisher=University of California Press|year=1990|translator=Catherine Errington|isbn=978-0-520-06319-8|url=https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_PYgkqP_s1PQC |page=}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=M9OIvQEACAAJ |title=A History of Macedonia: 336-167 B.C. |last=Hammond |first=N.G.L. |date=1988 |publisher=Clarendon Press |isbn=0-19-814815-1 |page=253 }}</ref> Dardania eventually became a part of the ] province.<ref>{{cite book|title=Starinar|volume=45–47|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZYxpAAAAMAAJ|year=1995|publisher=Arheološki institut|page=33}}</ref> During the reign of ], Dardania became a full ] and the entirety of Kosovo's modern territory became a part of the ], and then during the second half of the 4th century, it became part of the ].<ref>{{cite book|last=Roisman|first=Joseph|chapter=Classical Macedonia to Perdiccas III|title=A Companion to Ancient Macedonia|pages=145–165|location=Oxford|publisher=Wiley-Blackwell|year=2010|isbn=978-1-4051-7936-2|chapter-url=https://archive.org/stream/AncientMacedonia/Ancient%20Macedonia#page/n401/mode/2up| editor-given1 = Joseph | editor-surname1 = Roisman| editor-given2 = Ian | editor-surname2 = Worthington}}</ref>{{rp|548 | |||

| |footnote2 = Independence is not recognized. | |||

| |footnote3 = The ] is used in ] and ]. | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| ] situated southeast of ]. The city, built by ], was an important political, cultural, and economic center of the Roman province of Dardania.]] | |||

| '''Kosovo''' <!--Please leave the following language order as Albanian followed by Serbian: this is alphabetical and as neutral as we can get; Albanian is also the primary language of the region-->({{lang-sq|Kosova}} or ''Kosovë'', {{lang-sr|Косово}}, ''Kosovo'') is a territory in ]. After ] failed to reach a consensus on an acceptable ], ] unilaterally ] from ] on ] ]. The independent '''Republic of Kosovo''' ({{lang-sq|Republika e Kosovës}}, {{lang-sr|Република Косово}}, ''Republika Kosovo'') is anticipated to receive ]. The Serbian government regards the territory as an integral part of Serbia, the '''Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija''' ({{lang-sr|Аутономна покрајина Косово и Метохија}}, ''Autonomna pokrajina Kosovo i Metohija'', also Космет, ''Kosmet''; {{lang-sq|Krahina Autonome e Kosovës dhe Metohisë}}). This is also the position of the remainder of the international community. | |||

| During Roman rule, a series of settlements developed in the area, mainly close to mines and to the major roads. The most important of the settlements was ],{{sfn|Teichner|2015|p=81}} which is located near modern-day ]. It was established in the 1st century AD, possibly developing from a concentrated ] ], and then was upgraded to the status of a ] ] at the beginning of the 2nd century during the rule of ].<ref name="Anschnitt1">{{cite journal |title=Römischer Erzbergbau im Umfeld der antiken Stadt Ulpiana bei Pristina (Kosovo) |journal=Der Anschnitt |year=2011 |last1=Gassmann |first1=Guntram |last2=Körlin |first2=Gabriele |last3=Klein |first3=Sabine |volume=63 |pages=157–167 |url=https://www.bergbaumuseum.de/fileadmin/files/zoo/uploads/publikationen/gassmann2011-kosovo.pdf |access-date=2023-08-18 |archive-date=14 February 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240214103414/https://www.bergbaumuseum.de/fileadmin/files/zoo/uploads/publikationen/gassmann2011-kosovo.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Hoxhaj1">{{cite journal |title=Die frühchristliche dardanische Stadt Ulpiana und ihr Verhältnis zu Rom |journal=Dardanica |year=1999 |last=Hoxhaj |first=Enver |volume=8 |pages=21–33}}</ref> Ulpiana became especially important during the rule of ], after the Emperor rebuilt the city after it had been destroyed by an earthquake and renamed it to ''Iustinianna Secunda''.<ref>{{Cite journal|url=https://www.academia.edu/1585643|title=Archaeological Guide of Kosovo|first=Milot|last=Berisha|access-date=5 December 2021|website=Academia.edu|archive-date=27 April 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230427143514/https://www.academia.edu/1585643|url-status=live}}</ref>{{sfn|Teichner|2015|p=83}} | |||

| In addition to its frontier with the remainder of the Serbian state, Kosovo borders ], ], and the ]. It has a population of just over two million people, predominantly ethnic ], with smaller populations of ], ], ], ], and other ethnic communities. ] is the capital and largest city. | |||

| Other important towns that developed in the area during Roman rule were ], located in modern-day ]; ], possibly near ]; and ], an important mining town in ]. Other archeological sites include ] in Western Kosovo, ] in ], ] in Vushtrri, ] in ], ] between ] and ], ] near ], as well as ] and ] near ]. The one thing all the settlements have in common is that they are located either near roads, such as Via ]-], or near the mines of ] and eastern Kosovo. Most of the settlements are archaeological sites that have been discovered recently and are being excavated. | |||

| ] ] ] of ] placed Kosovo under the authority of the ] (UNMIK), with security provided by the ]-led ] (KFOR). Although the Resolution legally affirmed Serbia's ] over Kosovo, in practice Serbian governance in the province has been virtually non-existent since then. UNMIK's role in Kosovo is in the process of being supplanted by ], a ] body. The provisional parliament of Kosovo approved a declaration of independence on ] ], just before 3 PM local time, which the Government of Serbia proactively annuled. | |||

| It is also known that the region was Christianised during Roman rule, though little is known regarding Christianity in the Balkans in the three first centuries AD.<ref>{{cite book|last=Harnack|first=Adolf|title=The Expansion of Christianity in the First Three Centuries|volume=1–2|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FltKAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA1|year=1998|publisher=Wipf and Stock Publishers|isbn=978-1-57910-002-5 |page=371}}</ref> The first clear mention of Christians in literature is the case of Bishop Dacus of Macedonia, from Dardania, who was present at the ] (325).{{sfn|Harnack|1998|p=80}} It is also known that Dardania had a ] in the 4th century, and its seat was placed in Ulpiana, which remained the ] center of Dardania until the establishment of ] in 535 AD.<ref name="CetinkayaExcavate">{{cite journal |last1=Çetinkaya |first1=Halûk |title=To Excavate or not? Case of Discovery of an Early Christian Baptistery and Church at Ulpiana, Kosovo |journal=Actual Problems of Theory and History of Art |url=https://actual-art.org/files/sb/06/Cetinkaya.pdf |volume=6 |editor-last=Zakharova |editor-first=Anna |editor2-last=Maltseva |editor2-first=Svetlana |editor3-last=Stanyukovich-Denisova |editor3-first=Ekaterina |location=Saint Petersburg |publisher=NP-Print Publ. |year=2016 |pages=111–118 |doi=10.18688/aa166-2-11 |access-date=2023-08-18 |archive-date=10 March 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240310094626/https://actual-art.org/files/sb/06/Cetinkaya.pdf |url-status=live | issn = 2312-2129 }}</ref><ref name="Hoxhaj1" /> The first known bishop of Ulpiana is Machedonius, who was a member of the council of ]. Other known bishops were Paulus (] of ] in 553 AD), and Gregentius, who was sent by ] to ] and ] to ease problems among different Christian groups there.<ref name="CetinkayaExcavate" /> | |||

| == Geography == | |||

| {{main|Geography of Kosovo}} | |||

| === Middle Ages === | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| In the next centuries, Kosovo was a frontier province of the ], and later of the ], and as a result it changed hands frequently. The region was exposed to an increasing number of raids from the 4th century CE onward, culminating with the ] of the 6th and 7th centuries. Toponymic evidence suggests that ] was probably spoken in Kosovo prior to the Slavic settlement of the region.<ref>{{Cite thesis |last=Curtis |first=Matthew Cowan |title=Slavic-Albanian Language Contact, Convergence, and Coexistence |url=http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=osu1338406907 |publisher=The Ohio State University |year=2012 |page=42 |access-date=15 December 2022 |archive-date=30 September 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230930143737/https://etd.ohiolink.edu/acprod/odb_etd/etd/r/1501/10?clear=10&p10_accession_num=osu1338406907 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Prendergast2017">{{cite thesis|last1=Prendergast|first1=Eric|year=2017|title=The Origin and Spread of Locative Determiner Omission in the Balkan Linguistic Area|page=80|url=https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7nk454x6|publisher=UC Berkeley|access-date=7 June 2022|archive-date=12 May 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220512011446/https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7nk454x6|url-status=live}}</ref> The overwhelming presence of towns and municipalities in Kosovo with Slavic in their toponymy suggests that the Slavic migrations either assimilated or drove out population groups already living in Kosovo.<ref>{{cite conference |first=Thomas |last=Kingsley |title=Albanian Onomastics Using Toponymic Correspondences to Understand the History of Albanian Settlement |conference=6th Annual Linguistics Conference at the University of Georgia |pages=110–151 |date=2019 |location=United States |url=https://esploro.libs.uga.edu/esploro/outputs/conferencePaper/Albanian-Onomastics-Using-Toponymic-Correspondences-to/9949423226902959?institution=01GALI_UGA |access-date=23 January 2023 |archive-date=27 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230127220138/https://esploro.libs.uga.edu/esploro/outputs/conferencePaper/Albanian-Onomastics-Using-Toponymic-Correspondences-to/9949423226902959?institution=01GALI_UGA |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Kosovo has an area of 10,887 ]<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.kosovo-mining.org/kosovoweb/en/home.html |title=Welcome to the Independent Commission for Mines and Minerals (ICMM), Kosovo |author=Independent Commission for Mines and Minerals}}</ref> (4,203 ]) and a population of nearly two million. The largest cities are ], the capital, with an estimated 600,000 inhabitants, ] in the south west with a population of 165,000, ] in the west with 154,000, and ] in the north with 110,000. Five other towns have populations in excess of 97,000. | |||

| There is one intriguing line of argument to suggest that the Slav presence in Kosovo and southernmost part of the Morava valley may have been quite weak in the first one or two centuries of Slav settlement. Only in the ninth century can the expansion of a strong Slav (or quasi-Slav) power into this region be observed. Under a series of ambitious rulers, the Bulgarians pushed westwards across modern Macedonia and eastern Serbia, until by the 850's they had taken over Kosovo and were pressing on the border of ].<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_FMZQQAACAAJ&q=kosovo+a+short+history |title=Kosovo: A Short History |isbn=9780330412247 |access-date=9 January 2021 |archive-date=11 January 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210111130647/https://books.google.no/books?id=_FMZQQAACAAJ&dq=kosovo+a+short+history&hl=no&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj5z4PbjI_uAhWIuIsKHamyB90Q6AEwAHoECAAQAg |url-status=live |last1=Malcolm |first1=Noel |year=2002}}</ref> | |||

| The climate in Kosovo is continental, with warm summers and cold and snowy winters. | |||

| The ] acquired Kosovo by the mid-9th century, but Byzantine control was ] by the late 10th century. In 1072, the leaders of the Bulgarian ] traveled from their center in ] to Prizren and held a meeting in which they invited ] of ] to send them assistance. Mihailo sent his son, ] with 300 of his soldiers. After they met, the Bulgarian magnates proclaimed him "Emperor of the Bulgarians".<ref>{{cite book |last1=McGeer |first1=Eric |title=Byzantium in the Time of Troubles: The Continuation of the Chronicle of John Skylitzes (1057–1079) |date=2019 |publisher=BRILL |isbn=978-9004419407 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CmjIDwAAQBAJ |page=149 |access-date=19 September 2020 |archive-date=26 April 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210426180211/https://books.google.com/books?id=CmjIDwAAQBAJ |url-status=live}}</ref> ] is the last Byzantine archbishop of ] to include Prizren in his jurisdiction until 1219.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Prinzing |first1=Günter |title=Demetrii Chomateni Ponemata diaphora: |date=2008 |publisher=Walter de Gruyter |isbn=978-3110204506 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vllZG5zOxmMC |chapter=Demetrios Chomatenos, Zu seinem Leben und Wirken |page=30 |access-date=19 September 2020 |archive-date=5 August 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210805223703/https://books.google.com/books?id=vllZG5zOxmMC |url-status=live}}</ref> ] had seized the area along the ] in 1185 to 1195 and the ecclesiastical split of Prizren from the Patriarchate in 1219 was the final act of establishing ] rule. ] concluded, from the correspondence of archbishop Demetrios of Ohrid from 1216 to 1236, that Dardania was increasingly populated by Albanians and the expansion started from ] and ] area, prior to the Slavic expansion.<ref name="Abulafia1999">{{cite book|last=Ducellier|first=Alain|title=The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 5, c.1198-c.1300|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bclfdU_2lesC&pg=PA781|access-date=21 November 2012|date=1999-10-21|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-36289-4|page=780|archive-date=3 January 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140103143439/http://books.google.com/books?id=bclfdU_2lesC&pg=PA781|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| There are two main plains in Kosovo. The ] basin is located in the western part of the Kosovo, and the Plain of Kosovo occupies the eastern part. | |||

| ], a ].]] | |||

| ], a ].]] | |||

| During the 13th and 14th centuries, Kosovo was a political, cultural and religious centre of the ].<ref name="Sharpe 2003 364"/> In the late 13th century, the seat of the ] was moved to ], and rulers centred themselves between ] and ],<ref>Denis P Hupchik. The Balkans. From Constantinople to Communism. p. 93 "Dusan.. established his new state primate's seat at Peć (Ipek), in Kosovo"</ref> during which time thousands of Christian monasteries and feudal-style forts and castles were erected,<ref>Bieber, p. 12</ref> with ] using ] as one of his temporary courts for a time. When the Serbian Empire fragmented into a conglomeration of principalities in 1371, Kosovo became the hereditary land of the ].<ref name="Sharpe 2003 364">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jLfX1q3kJzgC |title=Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-Century Central-Eastern Europe |page=364 |last=Sharpe |first=M. E. |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170803211910/https://books.google.rs/books?id=jLfX1q3kJzgC&printsec=frontcover |archive-date=3 August 2017 |isbn=9780765618337 |year=2003|publisher=M.E. Sharpe }}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=RFE/RL Research Report: Weekly Analyses from the RFE/RL Research Institute, Том 3 |publisher=Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty}}</ref> During the late 14th and early 15th centuries, parts of Kosovo, the easternmost area located near Pristina, were part of the ], which was later incorporated into an anti-Ottoman federation of all Albanian principalities, the ].<ref name="Sellers2010">{{cite book|last=Sellers|first=Mortimer|title=The Rule of Law in Comparative Perspective|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9Rx7_KyUp7cC&pg=PA207|access-date=2 February 2011|year=2010|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-90-481-3748-0|page=207|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110511193103/https://books.google.com/books?id=9Rx7_KyUp7cC&pg=PA207|archive-date=11 May 2011}}</ref> | |||

| Much of Kosovo's terrain is mountainous. The ]s are located in the south and south-east, bordering ]. This is one of the region's most popular tourist and skiing resorts, with ] and Prevalac as the main tourist centres. Kosovo's mountainous area, including the highest peak ], at 2656 m above sea level, is located in the south-west, bordering Montenegro and Albania. | |||

| ] is a combined ] consisting of four ] churches and ] in ], ], ] and ]. The constructions were founded by members of the ], a prominent dynasty of ].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/724 |title=Medieval Monuments in Kosovo |publisher=] |access-date=7 September 2016 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150513120313/https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/724/ |archive-date=13 May 2015}}</ref> | |||

| The ] mountain is located in the north, bordering. The central region of ], Carraleva and the eastern part of Kosovo, known as ], are mainly hilly areas. | |||

| ==== Ottoman rule ==== | |||

| There are several notable rivers and lakes in Kosovo. The main rivers are the ], running towards the ], with the ] among its ]), the ], the ] in the Golak area, and ] in the north. The main lakes are Gazivoda (380 million m³) in the north-western part, Radonic (113 million m³) in the south-west part, Batlava (40 million m³) and Badovac (26 million m³) in the north-east part. | |||

| {{Main|History of Ottoman Kosovo}} | |||

| {{See also|Battle of Kosovo|Vilayet of Kosovo}} | |||

| ] built by ], 1461]] | |||

| <!-- === ] of Kosovo === | |||

| * with ] - 111,7 km | |||

| * with ] - 158,7 km | |||

| * with ] - 78,6 km | |||

| * with ] - 351,6 km | |||

| What accounts with a total of 700,7 km of borders.<ref name="SYSFRY1983">Statistical Yearbook of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, 1983.</ref> --> | |||

| In 1389, as the ] expanded northwards through the Balkans, Ottoman forces under Sultan ] met with a Christian coalition led by ] under ] in the ]. Both sides suffered heavy losses and the battle was a stalemate and it was even reported as a Christian victory at first, but Serbian manpower was depleted and ''de facto'' Serbian rulers could not raise another equal force to the Ottoman army.<ref name="Jelavich1983">{{cite book|author=Barbara Jelavich|title=History of the Balkans|url=https://archive.org/details/historyofbalkans0000jela|url-access=registration|year=1983|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-27458-6|pages=–}}</ref><ref name="prospect-magazine.co.uk">{{cite web|url=http://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/magazine/thebattleofkosovo/#axzz3eyNaDTl6 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120531075927/http://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/magazine/thebattleofkosovo/ |archive-date=31 May 2012 |title= Essays: 'The battle of Kosovo' by Noel Malcolm, Prospect Magazine May 1998 issue 30 |publisher=Prospect-magazine.co.uk |access-date=20 July 2009 |url-status=dead}}</ref><ref name="Humphreys46a2">{{harvnb|Humphreys|2013|p=46|ps=: "Both armies – and this is a fact that is ignored by the hagiographic telling – contained soldiers of various origins; Bosnians, Albanians, Hungarians, Greeks, Bulgars, perhaps even Catalans (on the Ottoman side)."}}</ref><ref name="Somel 2010 p. 36">{{cite book |last=Somel |first=S.A. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UU8iCY0OZmcC&pg=PA36 |title=The A to Z of the Ottoman Empire |publisher=Scarecrow Press |year=2010 |isbn=978-1-4617-3176-4 |series=The A to Z Guide Series |page=36 |quote="The coalition consisted of Serbians, Bosnians, Croatians, Hungarians, Wallachians, Bulgarians, and Albanians." |access-date=10 May 2024 |archive-date=28 November 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231128152103/https://books.google.com/books?id=UU8iCY0OZmcC&pg=PA36 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| == History == | |||

| {{Unreferencedsection|date:January 2008|date=January 2008}} | |||

| {{main|History of Kosovo}} | |||

| {{see also|Demographic history of Kosovo}} | |||

| Different parts of Kosovo were ruled directly or indirectly by the Ottomans in this early period. The medieval town of ] was under Lazar's son, ] who became a loyal Ottoman vassal and instigated the downfall of ] who eventually joined the Hungarian anti-Ottoman coalition and was defeated in 1395–96. A small part of Vuk's land with the villages of Pristina and Vushtrri was given to his sons to hold as Ottoman vassals for a brief period.<ref>{{harvnb|Fine|1994|pp=409–415}}</ref> | |||

| By 1455–57, the Ottoman Empire assumed direct control of all of Kosovo and the region remained part of the empire until 1912. During this period, ] was introduced to the region. After the failed ] by the Ottoman forces in 1693 during the ], a number of Serbs that lived in Kosovo, Macedonia and south Serbia migrated northwards near the Danube and Sava rivers, and is one of the events known as the ] which also included some Christian Albanians.<ref name=":5">{{Cite book |last1=Warrander |first1=Gail |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GCRjKdrmqqEC |title=Kosovo |last2=Knaus |first2=Verena |date=2007 |publisher=Bradt Travel Guides |isbn=978-1-84162-199-9 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Citation |last=Casiday |first=Augustine |title=The Orthodox Christian World |url=https://rifdt.instifdt.bg.ac.rs/bitstream/handle/123456789/1932/Cvetkovic%20-%20Serbian%20Tradition.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y |pages=135 |year=2012 |publisher=Routledge |access-date=16 September 2023 |archive-date=21 January 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220121151335/https://rifdt.instifdt.bg.ac.rs/bitstream/handle/123456789/1932/Cvetkovic%20-%20Serbian%20Tradition.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y |url-status=live }}</ref> <ref name="Rama2019">{{cite book |author=Shinasi A. Rama |title=Nation Failure, Ethnic Elites, and Balance of Power: The International Administration of Kosova |publisher=Springer |year=2019 |page=64}}</ref> The Albanians and Serbs who stayed in Kosovo after the war faced waves of Ottoman and Tatar forces, who unleashed a savage retaliation on the local population.<ref name=":5" /> To compensate for the population loss, the Turks encouraged settlement of non-Slav Muslim Albanians in the wider region of Kosovo.<ref>• Cohen, Paul A. (2014). ''''. Columbia University Press. pp. 8–9. ] ]. from the original on 30 November 2021. | |||

| • J. Everett-Heath (1 August 2000). ''Place Names of the World - Europe: Historical Context, Meanings and Changes''. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 365. ] ]. Archived from on 30 September 2023. | |||

| ===Medieval Period=== | |||

| • Geniş, Şerife, and Kelly Lynne Maynard (2009). ." ''Middle Eastern Studies''. '''45'''. (4): 556–557. | |||

| • Lampe, John R.; Lampe, Professor John R. (2000). ''''. Cambridge University Press. p. 26. ] ]. from the original on 30 September 2023. <q>The first Ottoman encouragement of Albanian migration did follow the Serb exodus of 1690</q> | |||

| ====Medieval Serbian state==== | |||

| • Anscombe, Frederick F 2006 - <nowiki>http://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/577/1/Binder2.pdf</nowiki> 14 May 2011 at the ] </ref> By the end of the 18th century, Kosovo would reattain an Albanian majority - with Peja, Prizren, Prishtina becoming especially important towns for the local Muslim population.<ref>• Cohen, Paul A. (2014). ''History and Popular Memory: The Power of Story in Moments of Crisis''. Columbia University Press. pp. 8–9. ] ]. from the original on 30 November 2021. | |||

| Kosovo is first known as ]. The Slavic tribes, although nominally under Byzantine vassalage, essentially ruled themselves. With the need for a more effective defensive organization, early principalities were formed. The most powerful of these were those of ] (modern central Serbia) and ] (roughly what is now Montenegro), which grew to be powerful Balkan states in their own right, influencing other Serbian territories. By the 850s AD, Kosovo became part of the expanding ]. During this time Slavic literacy and Christianity spread throughout the region. Bulgarian rule lasted until 1018, when the Byzantine Empire dealt a death blow to Bulgarian ], ]. In fact, the Byzantines re-asserted their rule over most of the Balkans for the first time since the 6th century. | |||

| • Lampe, John R.; Lampe, Professor John R. (2000). ''Yugoslavia as History: Twice There Was a Country''. Cambridge University Press. p. 26. ] ]. from the original on 30 September 2023. <q>The first Ottoman encouragement of Albanian migration did follow the Serb exodus of 1690</q> | |||

| A popular uprising against Byzantine rule commenced in Dioclea by ]. One Vukan, a nephew of the Dioclean King Mihailo (Voislav's descendent), was made Zhupan of Raska by his uncle. He struggled to free Raska from the Byzantines, and pushed through Kosovo c. 1092, and into Macedonia. There were several offensives and counter-offensives, however Vukan eventually accepted Byzantine vassalage. The full Serbian liberation of Kosovo from the Byzantines would not be achieved until 1208 by ] of the ]. During this time Kosovo became the cultural, religious and political heart of the Serbian Kingdom. Numerous Christian monasteries were erected, such as the ]. The zenith of medieval Serbia’s state was reached in 1346, when ] was crowned Emperor of Serbs, Vlachs, Greeks and Albanians, having conquered virtually all of Greece. However, with his death, his multiethnic Christian Empire also died due to internal power struggles, opening the Balkan’s up for the Ottoman invasion. The empire was split amongst regional nobility - Kosovo became a domain of the ] initially. | |||

| ] | |||

| • Malcolm, Noel (10 July 2020). ''Noel Malcolm 2020 p . 135''. Oxford University Press. ] ]. from the original on 30 September 2023. | |||

| ===Ottoman rule=== | |||

| • Rebels, Believers, Survivors: Studies in the history of the Albanians - Malcolm 2020 p. 132-133/p | |||

| The ] invaded and met the Balkan coalition Army under ] on ] ], near ], at Gazi Mestan. The Serbian Army was assisted by various allies. The epic ] followed, in which Prince Lazar himself lost his life. Prince Lazar amassed 12,000-30,000 men on the battlefield and the Ottomans had 27,000-40,000. Under the pretext of surrender ] managed to murder ] ] and the new Sultan ] had, despite winning the battle, to retreat to consolidate his power. The Ottoman Sultan was buried with one of his sons at Gazi Mestan. Both ] and ] were canonized by the ] for their efforts in the battle. The local House of ] came to prominence as the local lords of Kosovo, under ], with the temporary fall of the ] in ]. Another great battle occurred between the Hungarian troops supported by the Albanian ruler Gjergj Kastrioti ] on one side, and Ottoman troops supported by the ]s in ]. Skanderbeg's troops that were going to help John Hunyadi were stopped by the Branković's troops, who was more or less a Turkish ]. Hungarian regent ] lost the battle after a two-day fight, but essentially stopped the Ottoman advance northwards. Kosovo then became vassalaged to the Ottoman Empire, until its direct incorporation after the final fall of Serbia in 1459. | |||

| In 1455, new castles rose to prominence in Priština and ], centres of the Ottoman vassalaged House of Branković. | |||

| • Rebels, Believers, Survivors: Studies in the history of the Albanians - Malcolm 2020 p. 143/p</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| {{seealso|Vilayet of Kosovo}} | |||

| {{seealso|History of Ottoman Serbia}} | |||

| The ] brought ] with them, particularly in towns, and later also created the ] as one of the Ottoman territorial entities. Kosovo was taken by the Austrian forces during the Great War of ]–] with help of 5,000 Albanians and their leader, a ] ] ]. In ], the ] ], who previously escaped a certain death, led 37,000 families from Kosovo to evade ] wrath, since Kosovo had just been retaken by the Ottomans. The people who followed him were mostly ], but they were likely followed by other ethnic groups. Due to the oppression from the Ottomans, other migrations of Orthodox people from the Kosovo area continued throughout the ]. It is also noted that some ] adopted ], while some even gradually fused with other groups, predominantly Albanians, adopting their culture and even language, essentially leaving a predominantly Islamic presence in Kosovo. | |||

| Although initially stout opponents of the advancing Turks, Albanian chiefs ultimately came to accept the Ottomans as sovereigns. The resulting alliance facilitated the mass conversion of Albanians to Islam. Given that the Ottoman Empire's subjects were divided along religious (rather than ethnic) lines, the spread of Islam greatly elevated the status of Albanian chiefs. Centuries earlier, Albanians of Kosovo were predominantly Christian and Albanians and Serbs for the most part co-existed peacefully. The Ottomans appeared to have a more deliberate approach to converting the Roman Catholic population who were mostly Albanians in comparison with the mostly Serbian adherents of Eastern Orthodoxy, as they viewed the former less favorably due to its allegiance to Rome, a competing regional power.<ref name="Cohen">{{cite book |last1=Cohen |first1=Paul A. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DcfbAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA8 |title=History and Popular Memory: The Power of Story in Moments of Crisis |date=2014 |publisher=Columbia University Press |isbn=978-0-23153-729-2 |pages=8–9 |access-date=19 September 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211130180358/https://books.google.com/books?id=DcfbAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA8 |archive-date=30 November 2021 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| In 1766, the Ottomans abolished the ] and the position of ] in Kosovo was greatly reduced. All previous privileges were lost, and the Christian population had to suffer the full weight of the Empire's extensive and losing wars.{{Fact|date=December 2007}} The main reason for the conversion of Orthodox Albanians into Muslim Albanians was for the greater benefit of less taxes.{{Fact|date=December 2007}} Remnants of Orthodox Albanians, in Kosovo, went to live in mountains or rural parts of Montenegro. Many Islamic Albanians gained important position in the Ottoman regimen, and served as fierce oppressors of any anti- Turkish revolts.<ref>The Balkans. From Constantinople to Communsims</ref> Nearly five centuries of Ottoman rule essentially led to a drastic change in ethnic composition. | |||

| === |

==== Rise of nationalism ==== | ||

| {{seealso|History of Modern Kosovo}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| In 1871, a massive Serbian meeting was held in Prizren at which the possible retaking and reintegration of Kosovo and the rest of "Old Serbia" was discussed, as the ] itself had already made plans for expansions towards Ottoman territory. | |||

| ] was the cultural and intellectual centre of Kosovo during the Ottoman period in the Middle Ages and is now the historic capital of Kosovo.]] | |||

| Albanian refugees from the territories conquered in the ]–] Serbo-Turkish war and the ]–] Russo-Turkish war are now known as ']' (which means 'refugee', from ] ]). Their descendants still have the same surname, ''Muhaxheri''. It is estimated that 200,000 to 400,000 Serbs were cleansed out of the ] between ] and ] by Turks and their Albanian allies, especially during the ] in ].{{Fact|date=February 2008}} | |||

| In the 19th century, there was an ] of ] throughout the Balkans. The underlying ethnic tensions became part of a broader struggle of Christian Serbs against Muslim Albanians.<ref name="prospect-magazine.co.uk"/> The ethnic ] movement was centred in Kosovo. In 1878 the ] ({{lang|sq|Lidhja e Prizrenit}}) was formed, a political organisation that sought to unify all the Albanians of the Ottoman Empire in a common struggle for autonomy and greater cultural rights,<ref>''Kosovo: What Everyone Needs to Know'' by Tim Judah, Publisher ], US, 2008 {{ISBN|0-19-537673-0|978-0-19-537673-9}} p. 36</ref> although they generally desired the continuation of the Ottoman Empire.<ref name="Cirkovic. p. 244">Cirkovic. p. 244.</ref> The League was dis-established in 1881 but enabled the awakening of a ] among Albanians,<ref>George Gawlrych, ''The Crescent and the Eagle,'' (Palgrave/Macmillan, London, 2006), {{ISBN|1-84511-287-3}}</ref> whose ambitions competed with those of the Serbs, the ] wishing to incorporate this land that had formerly been within its empire. | |||

| In 1878, a Peace Accord was drawn that left the cities of Priština and ] under civil Serbian control, and outside the jurisdiction of the Ottoman authorities, while the rest of Kosovo would be under Ottoman control. As a response, the Albanians formed the nationalistic and conservative ] in ] later the same year. Over three hundred Albanian leaders from Kosovo and western Macedonia gathered and discussed the urgent issues concerning protection of Albanian populated regions from division among neighbouring countries. The League was supported by the Ottoman Sultan because of its Pan-Islamic ideology and political aspirations of a ] under the Ottoman umbrella. The movement gradually became anti-Christian and spread great anxiety among Christian Albanians and especially among Christian Serbs. As a result, more and more Serbs left Kosovo northwards. Serbia complained to the World Powers that the promised territories were not being held because the Ottomans were hesitating to do that. The World Powers put pressure on the Ottomans and in 1881, the Ottoman Army began fighting the Albanian forces. The Prizren League created a Provisional Government with a President, Prime Minister (Ymer Prizreni) and Ministries of War (Sylejman Vokshi) and Foreign Ministry (Abdyl Frashëri). After three years of war, the Albanians were defeated. Many of the leaders were executed and imprisoned. The subsequent Treaty of San Stefano in 1878 restored most Albanian lands to Ottoman control, but the Serbian forces had to retreat from Kosovo along with some Serbs that were expelled as well. By the end of the 19th century the ] replaced the ] as the dominant people in Kosovo. | |||

| The modern Albanian-Serbian conflict has its roots in the ] from areas that became incorporated into the ].<ref>{{cite journal|last=Frantz|first=Eva Anne |title= Violence and its Impact on Loyalty and Identity Formation in Late Ottoman Kosovo: Muslims and Christians in a Period of Reform and Transformation |journal= Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs |volume=29 |issue=4 |year=2009 |pages=460–461 |doi=10.1080/13602000903411366|s2cid=143499467}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Müller|first=Dietmar|title=Orientalism and Nation: Jews and Muslims as Alterity in Southeastern Europe in the Age of Nation-States, 1878–1941|journal=East Central Europe|volume=36|issue=1|year=2009|page=70|doi=10.1163/187633009x411485}}</ref> During and after the ], between 30,000 and 70,000 Muslims, mostly Albanians, were expelled by the ] from the ] and fled to the ].<ref>Pllana, Emin (1985). "Les raisons de la manière de l'exode des refugies albanais du territoire du sandjak de Nish a Kosove (1878–1878) ". ''Studia Albanica''. '''1''': 189–190.</ref><ref>Rizaj, Skënder (1981). "Nënte Dokumente angleze mbi Lidhjen Shqiptare të Prizrenit (1878–1880) ". ''Gjurmine Albanologjike (Seria e Shkencave Historike)''. '''10''': 198.</ref><ref>Şimşir, Bilal N, (1968). ''Rumeli'den Türk göçleri. Emigrations turques des Balkans ''. Vol I. Belgeler-Documents. p. 737.</ref><ref name=Batakovic1992>{{cite book|last=Bataković|first=Dušan|title=The Kosovo Chronicles|year=1992|publisher=Plato|url=http://www.rastko.rs/kosovo/istorija/kosovo_chronicles/kc_part2b.html|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161226174611/http://www.rastko.rs/kosovo/istorija/kosovo_chronicles/kc_part2b.html|archive-date=26 December 2016}}</ref><ref name=Elsie2010>{{cite book|last=Elsie|first=Robert|title=Historical Dictionary of Kosovo|year=2010|publisher=Scarecrow Press|isbn=9780333666128|page=xxxii}}</ref><ref>Stefanović, Djordje (2005). "Seeing the Albanians through Serbian eyes: The Inventors of the Tradition of Intolerance and their Critics, 1804–1939." ''European History Quarterly''. '''35'''. (3): 470.</ref> According to Austrian data, by the 1890s Kosovo was 70% Muslim (nearly entirely of Albanian descent) and less than 30% non-Muslim (primarily Serbs).<ref name="Cohen" /> In May 1901, Albanians pillaged and partially burned the cities of ], ] and Pristina, and ] near Pristina and in Kolašin (now North Kosovo).<ref name=King-Mason-30>{{cite book|author1=Iain King|author2=Whit Mason|title=Peace at Any Price: How the World Failed Kosovo|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9m3Hp2OevdUC&pg=PA30|year=2006|publisher=Cornell University Press|isbn=978-0-8014-4539-2|page=30|access-date=7 October 2018|archive-date=9 January 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200109150705/https://books.google.com/books?id=9m3Hp2OevdUC&pg=PA30|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Skendi |first1=Stavro |title=The Albanian National Awakening |date=2015 |publisher=Cornell University Press |isbn=978-1-4008-4776-1 |page=201 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8QPWCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA201 |access-date=28 July 2021 |archive-date=28 July 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210728220204/https://books.google.com/books?id=8QPWCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA201 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In 1908, the Sultan brought a new democratic decree that was valid only for Turkish-speakers. As the vast majority of Kosovo spoke Albanian or Serbian, the Kosovar population was very unhappy. The Young Turk movement supported a centralist rule and opposed any sort of autonomy desired by Kosovars, and particularly the Albanians. In 1910, an ] uprising spread from Priština and lasted until the Ottoman Sultan's visit to Kosovo in June of 1911. The Aim of the League of Prizren was to unite the four Albanian Vilayets by merging the majority of Albanian inhabitants within the Ottoman Empire into one Albanian State. However, at that time Serbs have consisted about 25% of the whole Vilayet of Kosovo's overall population and were opposing the Albanian rule along with Turks and other Slavs in Kosovo, which disabled the Albanian movements to occupy Kosovo. | |||

| ] between the ] (''yellow'') and the ] (''green'') following the ] 1913.]] | |||

| {{seealso|Serbia in WWI}} | |||

| In the spring of 1912, Albanians under the lead of ] ] against the Ottoman Empire. The rebels were joined by a wave of Albanians in the ] ranks, who deserted the army, refusing to fight their own kin. The rebels defeated the Ottomans and the latter were forced to accept all fourteen demands of the rebels, which foresaw an effective autonomy for the Albanians living in the Empire.{{sfn|Malcolm|1998|p=246-248}} However, this autonomy never materialised, and the revolt created serious weaknesses in the Ottoman ranks, luring ], ], ], and ] into declaring war on the Ottoman Empire and starting the ]. | |||

| In ], during the ], most of Kosovo was taken by the ], while the region of ] (]: ''Dukagjini Valley'') was taken by the ]. An exodus of the local Albanian population occurred. This is best described by ], who was a reporter for the ''Pravda'' newspaper at the time. The Serbian authorities planned a recolonization of Kosovo.<ref> . Dukagjini Balkan Books, Peja (Kosovo, Serbia). ISBN 9951-05-016-6</ref> Numerous colonist Serb families moved-in to Kosovo, equalizing the demographic balance between Albanians and Serbs. Many Albanians fled into the mountains and numerous Albanian and Turkish houses were razed. The reconquest of Kosovo was noted as a vengeance for the 1389 ]. At the Conference of Ambassadors in London in 1912 presided over by Sir Edward Grey, the British Foreign Secretary, the Kingdoms of Serbia and Montenegro were acknowledged sovereignty over Kosovo. | |||

| After the Ottomans' defeat in the ], the ] was signed with Metohija ceded to the ] and eastern Kosovo ceded to the ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/boshtml/bos145.htm|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/19970501052336/http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/boshtml/bos145.htm|archive-date=1 May 1997 |title=Treaty of London, 1913 |publisher=Mtholyoke.edu |access-date=6 November 2011}}</ref> During the ], over 100,000 Albanians left Kosovo and about 50,000 were killed in the ] that accompanied the war.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Malcolm|first=Noel|date=1999|title=Kosovo – A Short History|journal=Verfassung in Recht und Übersee|volume=32|issue=3|pages=422–423|doi=10.5771/0506-7286-1999-3-422|issn=0506-7286|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Aggression Against Yugoslavia Correspondence |date=2000 |publisher=Faculty of Law, University of Belgrade |isbn=978-86-80763-91-0 |page=42 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=cEEmAQAAIAAJ&q=freundlich |access-date=29 April 2020 |language=en |archive-date=30 September 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230930144245/https://books.google.com/books?id=cEEmAQAAIAAJ&q=freundlich |url-status=live }}</ref> Soon, there were concerted ] in Kosovo during various periods between Serbia's 1912 takeover of the province and ], causing the population of Serbs in Kosovo to grow by about 58,000 in this period.{{sfn|Malcolm|1998|p=279}}<ref>{{cite journal|last=Pavlović|first=Aleksandar|title=Prostorni raspored Srba i Crnogoraca kolonizovanih na Kosovo i Metohiju u periodu između 1918. i 1941. godine|url=http://scindeks-clanci.nb.rs/data/pdf/0353-9008/2008/0353-90080824231P.pdf|journal=Baština|volume=24|year=2008|pages=235|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110826204541/http://scindeks-clanci.nb.rs/data/pdf/0353-9008/2008/0353-90080824231P.pdf|archive-date=26 August 2011}}</ref> | |||

| In the winter of ]–], during ], Kosovo saw a large exodus of Serbian army which became known as the ''Great Serbian Retreat''. Defeated and worn out in battles against Austro-Hungarians, they had no other choice than to retreat, as Kosovo was occupied by ] and ]. The Albanians joined and supported the ]. As opposed to Serbian schools, numerous Albanian schools were opened during the 'occupation' (the majority Albanian population considered it a liberation). Allied ships were awaiting for Serbian people and soldiers at the banks of the Adriatic sea and the path leading them there went across Kosovo and Albania. Tens of thousands of soldiers died of starvation, extreme weather and Albanian reprisals{{Fact|date=February 2008}} as they were approaching the ] in ] and ], amassing a total of 100,000 dead retreaters.{{Fact|date=February 2008}} Transported away from the front lines, Serbian army managed to heal many wounded and ill soldiers and get some rest. Refreshed and regrouped, it decided to return to the battlefield. In 1918, the Serbian Army pushed the ] out of Kosovo. During Serbian control of Kosovo, the Serbian Army committed atrocities against the population in revenge.{{Fact|date=December 2007}} Serbian Kosovo was unified with Montenegrin Metohija as Montenegro subsequently joined the Kingdom of Serbia. After the World War I ended, the Monarchy was then transformed into the ] (Serbo-Croatian: ''Kraljevina Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca'', Albanian: ''Mbretëria Serbe, Kroate, Sllovene'') on ] ], gathering territories gained in victory. | |||

| Serbian authorities promoted creating new Serb settlements in Kosovo as well as the assimilation of Albanians into Serbian society, causing a mass exodus of Albanians from Kosovo.<ref name = "Schabnel 2001 20">Schabnel, Albrecht; Thakur, Ramesh (eds). Kosovo and the Challenge of Humanitarian Intervention: Selective Indignation, ], and International Citizenship. New York: The United Nations University, 2001. p. 20.</ref> The figures of Albanians forcefully expelled from Kosovo range between 60,000 and 239,807, while Malcolm mentions 100,000–120,000. In combination with the politics of extermination and expulsion, there was also a process of assimilation through religious conversion of Albanian Muslims and Albanian Catholics into the Serbian Orthodox religion which took place as early as 1912. These politics seem to have been inspired by the nationalist ideologies of ] and ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=I. Mehmeti |first1=Leandrit |last2=Radeljic |first2=Branislav |title=Kosovo and Serbia: Contested Options and Shared Consequences |date=24 March 2017 |publisher=University of Pittsburgh Press |location=Pittsburgh |pages=63–64 |isbn=978-0822944690 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IWMqDwAAQBAJ |access-date=8 December 2021 |archive-date=7 March 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220307171432/https://books.google.com/books?id=IWMqDwAAQBAJ |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ====Kingdom of Yugoslavia and World War II==== | |||

| The 1918–1929 period of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians witnessed a rise of the Serbian population in the region and a decline in the non-Serbian. In the Kingdom, Kosovo was split into four counties—three being a part of the entity of Serbia: Zvečan, Kosovo and southern Metohija; and one of Montenegro: northern Metohija. However, the new administration system since ] ] split Kosovo among three Areas of the Kingdom: Kosovo, ] and ]. In 1921 the Albanian elite lodged an official protest of the government to the League of Nations, claiming that 12,000 Albanians had been killed and over 22,000 imprisoned since 1918 and seeking a ]. As a result, an armed ''Kachak'' resistance movement was formed whose main goal was to unite Albanian-populated areas of the Kingdom to Albania. | |||

| In |

In the winter of 1915–16, during ], Kosovo saw the retreat of the Serbian army as Kosovo was occupied by ] and ]. In 1918, the ] pushed the ] out of Kosovo. | ||

| ], circa 1941.]] | |||

| A new administration system since 26 April 1922 split Kosovo among three districts (]) of the Kingdom: Kosovo, Raška and Zeta. In 1929, the country was transformed into the ] and the territories of Kosovo were reorganised among the ], the ] and the ]. In order to change the ], between 1912 and 1941 a ] was undertaken by the Belgrade government. Kosovar Albanians' right to receive education in their own language ] alongside other non-Slavic or unrecognised Slavic nations of Yugoslavia, as the kingdom only recognised the Slavic Croat, Serb, and Slovene nations as constituent nations of Yugoslavia. Other Slavs had to identify as one of the three official Slavic nations and non-Slav nations deemed as minorities.<ref name = "Schabnel 2001 20"/> | |||

| The greatest part of Kosovo became a part of ]-controlled ], and smaller bits by the ] and ] ]-occupied ]. During the fascist occupation of Kosovo by Albanians, until ] ] alone, over 10,000 ] were killed and between 80,000 and 100,000 ] were expelled, while roughly the same number of Albanians from Albania were brought to settle in these Serbian lands.<ref>Krizman, Serge. "Massacre of the innocent Serbian population, committed in Yugoslavia by the Axis and its Satellite from April 1941 to August 1941". Map. ''Maps of Yugoslavia at War'', Washington, ]</ref> | |||

| Albanians and other ] were forced to emigrate, mainly with the land reform which struck Albanian landowners in 1919, but also with direct violent measures.<ref name="daskalovski">Daskalovski, Židas. Claims to Kosovo: Nationalism and ]. In: Florian Bieber & Zidas Daskalovski (eds.), ''Understanding the War in Kosovo''. L.: Frank Cass, 2003. {{ISBN|0-7146-5391-8}}. pp. 13–30.</ref>{{sfn|Malcolm|1998|p=}} In 1935 and 1938, two agreements between the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and Turkey were signed on the expatriation of 240,000 Albanians to Turkey, but the expatriation did not occur due to the outbreak of ].<ref>Ramet, Sabrina P. The Kingdom of God or the Kingdom of Ends: Kosovo in Serbian Perception. In Mary Buckley & Sally N. Cummings (eds.), ''Kosovo: Perceptions of War and Its Aftermath''. L. – N.Y.: Continuum Press, 2002. {{ISBN|0-8264-5670-7}}. pp. 30–46.</ref> | |||

| Mustafa Kruja, the ] of ], was in Kosovo in ] ], and at a meeting with the Albanian leaders of Kosovo, he said: "''We should endeavor to ensure that the Serb population of Kosovo be – the area be cleansed of them and all Serbs who had been living there for centuries should be termed colonialists and sent to concentration camps in Albania. The Serb settlers should be killed.''"<ref>Bogdanović, Dimitrije. "The Book on Kosovo". 1990. Belgrade: ''Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts'', 1985. page 2428.</ref><ref>Genfer, Der Kosovo-Konflikt, ]: Wieser, ]. page 158.</ref> | |||