| Revision as of 05:40, 7 February 2022 editGeraldo Perez (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers259,400 editsm Reverted 1 edit by 92.40.182.157 (talk): De jure means by lawTags: Twinkle Undo← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:00, 21 December 2024 edit undoGreenC bot (talk | contribs)Bots2,564,227 edits Reformat 1 archive link. Wayback Medic 2.5 per WP:USURPURL and JUDI batch #20 | ||

| (41 intermediate revisions by 33 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|none}} <!-- "none" is preferred when the title is sufficiently descriptive; see ] --> | |||

| {{short description|Languages of a geographic region}} | |||

| {{ |

{{More citations needed|date=September 2017}} | ||

| {{EngvarB|date=October 2013}} | {{EngvarB|date=October 2013}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date= |

{{Use dmy dates|date=September 2024}} | ||

| {{Languages of | {{Languages of | ||

| | country = Ireland | | country = Ireland | ||

| | main = ] ( |

| main = ] (98%)<ref>{{cite web|url=http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_386_en.pdf|title=SPECIAL EUROBAROMETER 386 Europeans and their Languages|publisher=Ec.europa.eu|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160106183351/http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_386_en.pdf|archive-date=6 January 2016}}</ref><br />Irish (RoI: 39.8% claim some ability to speak Irish)<ref name="CSO_Ir">{{Cite web |title=Irish Language and the Gaeltacht – CSO – Central Statistics Office |url=https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-cp10esil/p10esil/ilg/ |access-date=2023-01-29 |website=cso.ie}}</ref><br />] (0.3%)<br />] | ||

| | sign = ]<br>] | | sign = ]<br />] | ||

| | immigrant = ], |

| immigrant = ], French, German, ], Spanish, Russian, ] | ||

| | foreign = French (20%), German (7%), Spanish (3.7%) | | foreign = French (20%), German (7%), Spanish (3.7%) | ||

| | keyboard = Irish or British ] | | keyboard = Irish or British ] | ||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| There are a number of languages used in |

There are a number of languages used in Ireland. Since the late 18th century, ] has been the predominant first language, displacing Irish. A large minority claims some ability to use Irish,<ref name="CSO_Ir"/> and it is the first language for a small percentage of the population. | ||

| In the ], under the ], both languages have official status, with Irish being the national and first official language.<ref> |

In the ], under the ], both languages have official status, with Irish being the national and first official language.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Book (eISB) |first=electronic Irish Statute |title=electronic Irish Statute Book (eISB) |url=https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/cons/en/html |access-date=2024-10-16 |website=www.irishstatutebook.ie |at=Art. 8 |language=en}}</ref> | ||

| In ], English is the primary language for 95% of the population, and ''de facto'' official language, while Irish is recognised as an official language and ] is recognised as a minority language under the ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/3168/stages|title=Identity and Language (Northern Ireland) Act 2022}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-63923308|title=Language and identity laws could spell significant change|publisher=BBC News |date=11 December 2022}}</ref> | |||

| {{Culture of Ireland}} | {{Culture of Ireland}} | ||

| Line 28: | Line 30: | ||

| === English === | === English === | ||

| {{Main article|English language|Hiberno-English|Ulster English}} | {{Main article|English language|Hiberno-English|Ulster English}} | ||

| ] was first introduced by the Cambro-Norman settlers in the 12th century. It did not initially take hold as a widely spoken language, as the Norman |

] was first introduced by the Cambro-Norman settlers in the 12th century. It did not initially take hold as a widely spoken language, as the Norman elite spoke ]. In time, many Norman settlers intermarried and assimilated to the ]s and some even became "]". Following the ] and the 1610–15 ], particularly in the old Pale, Elizabethan English became the language of court, justice, administration, business, trade and of the ]. Monolingual Irish speakers were generally of the poorer and less educated classes with no land. Irish was accepted as a vernacular language, but then as now, fluency in English was an essential element for those who wanted social mobility and personal advancement. After the legislative Union of Great Britain and Ireland's succession of Irish Education Acts that sponsored the ] and provided free public primary education, Hiberno-English replaced the Irish language. Since the 1850s, ] was promoted by both the UK administration and the Roman ]. This greatly assisted the waves of immigrants forced to seek new lives in the US and throughout the Empire after the Famine. Since then the various local Hiberno-English dialects comprise the vernacular language throughout the island. | ||

| The 2002 census found that 103,000 British citizens were living in the Republic of Ireland, along with 11,300 from the US and 8,900 from Nigeria, all of whom would speak other dialects of English.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.threemonkeysonline.com/threemon_printable.php?id=59|title=It's in the blood. The Citizenship referendum in Ireland|date=1 June 2004|website=Threemonkeysonline.com|access-date=10 September 2017}}</ref> The 2006 census listed 165,000 people from the UK, and 22,000 from the US.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cso.ie/census/documents/Final+Principal+Demographic+Results+2006.pdf|date=25 March 2009|access-date=10 September 2017|url-status=bot: unknown|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090325005303/http://www.cso.ie/census/documents/Final%20Principal%20Demographic%20Results%202006.pdf|archive-date=25 March 2009 |

The 2002 census found that 103,000 British citizens were living in the Republic of Ireland, along with 11,300 from the US and 8,900 from Nigeria, all of whom would speak other dialects of English.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.threemonkeysonline.com/threemon_printable.php?id=59|title=It's in the blood. The Citizenship referendum in Ireland|date=1 June 2004|website=Threemonkeysonline.com|access-date=10 September 2017}}</ref> The 2006 census listed 165,000 people from the UK, and 22,000 from the US.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cso.ie/census/documents/Final+Principal+Demographic+Results+2006.pdf|date=25 March 2009|access-date=10 September 2017|url-status=bot: unknown|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090325005303/http://www.cso.ie/census/documents/Final%20Principal%20Demographic%20Results%202006.pdf|archive-date=25 March 2009}}</ref> The 2016 census reported a decline in UK nationals to the 2002 level: 103,113.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-cpnin/cpnin/uk/|title=UK – CSO – Central Statistics Office}}</ref> | ||

| === Irish === | === Irish === | ||

| {{Main article|Irish language|List of Irish-language media|Gaelic revival}} | {{Main article|Irish language|List of Irish-language media|Gaelic revival}} | ||

| The original ] was introduced by Celtic speakers. Primitive Irish gradually evolved into ], spoken between the 5th and the 10th centuries, and then into ]. Middle Irish was spoken in Ireland, ], and the ] through the 12th century, when it began to evolve into modern Irish in Ireland, ] in Scotland, and the ] in the Isle of Man. Today, Irish is |

The original ] was introduced by Celtic speakers. Primitive Irish gradually evolved into ], spoken between the 5th and the 10th centuries, and then into ]. Middle Irish was spoken in Ireland, ], and the ] through the 12th century, when it began to evolve into modern Irish in Ireland, ] in Scotland, and the ] in the Isle of Man. Today, Irish is recognized as the first official language of the ] and is officially recognized in the European Union. Communities that speak Irish as their first language, generally in sporadic regions on the island's west coast, are collectively called the ]. | ||

| In the 2016 census, 8,068 census forms were completed in Irish, and just under 74,000 |

In the 2016 Irish census, 8,068 census forms were completed in Irish, and just under 74,000 of the total (1.7%) said they spoke it daily. The total number of people who answered 'yes' to being able to speak Irish to some extent in April 2016 was 1,761,420, 39.8 percent of respondents.<ref name="CSO_Ir"/> | ||

| ]]] | ]]] | ||

| Although the use of Irish in educational and broadcasting contexts has |

Although the use of Irish in educational and broadcasting contexts has increased notably with the 600 plus Irish-language primary/secondary schools and creches {{Citation needed|date=July 2021}}, English is still overwhelmingly dominant in almost all social, economic, and cultural contexts. In the media, there is an Irish-language TV station ], ] a children's channel on satellite, 5 radio stations such as the national station ], ] in Dublin, as well as ] in Belfast and a youth radio station ]. There are also several newspapers, such as '']'', ''Meon Eile'', ''Seachtain'' (a weekly supplement in the ''Irish Independent''), and several magazines including ''Comhar'', ''Feasta'', and ''An Timire''. There are also occasional columns written in Irish in English-language newspapers, including '']'', '']'', '']'', '']'', '']'', the '']'', and the '']''. All of the 40 or so radio stations in the Republic have to have some weekly Irish-language programming to obtain their broadcasting license.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.bci.ie/documents/2001act.pdf|date=14 October 2009|access-date=10 September 2017|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091014221732/http://www.bci.ie/documents/2001act.pdf|archive-date=14 October 2009 |title=Broadcasting Act 2001}}</ref> Similarly, ] runs ''Nuacht'', a news show, in Irish and ''Léargas'', a documentary show, in Irish with English subtitles. The ] gave many new rights to Irish citizens concerning the Irish language, including the use of Irish in court proceedings.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.oireachtas.ie/documents/bills28/acts/2003/a3203.pdf |title=Official Languages Act 2003 |date=30 October 2003 |access-date=8 June 2011 |publisher=Oireachtas na hÉireann}}</ref> All ] debates are to be recorded in Irish also. In 2007, Irish became the 21st official language of the European Union. | ||

| === Ulster Scots === | === Ulster Scots === | ||

| {{Main article|Ulster Scots dialects}} | {{Main article|Ulster Scots dialects}} | ||

| Ulster Scots sometimes called ] is a dialect of ] spoken in some parts of ] and ]. It is promoted by the ], a cross-border body. Its status as an independent language as opposed to a dialect of Scots has been debated.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.scots-online.org/articles/contents/awaeoo.pdf|title=Aw Ae Oo—Scots in Scotland and Ulster |

Ulster Scots, sometimes called ], is a dialect of ] spoken in some parts of ] and ]. It is promoted and supported by the ], a cross-border body. Its status as an independent language as opposed to a dialect of Scots has been debated.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.scots-online.org/articles/contents/awaeoo.pdf|title=Aw Ae Oo—Scots in Scotland and Ulster|website=Scots-online.org|access-date=10 September 2017|archive-date=1 April 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170401082720/http://scots-online.org/articles/contents/awaeoo.pdf|url-status=dead}}</ref> | ||

| === Shelta === | === Shelta === | ||

| Line 58: | Line 60: | ||

| ===Immigrant languages=== | ===Immigrant languages=== | ||

| ] at ] to celebrate ]. There are over 15,000 |

] at ] to celebrate ]. There are over 15,000 Chinese-speakers in Ireland.]] | ||

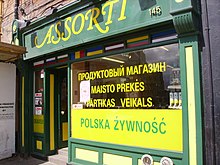

| ], with signage in |

], with signage in Russian, ], ] and ].]] | ||

| With increased immigration into Ireland, there has been a substantial increase in the number of people speaking languages. The table below gives figures from the 2016 census of population usually resident and present in the state who speak a language other than English, Irish or a sign language at home.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://statbank.cso.ie/px/pxeirestat/Statire/SelectVarVal/Define.asp?Maintable=EY025&Planguage=0|title=Population Usually Resident and Present in the State who Speak a Language other than English or Irish at Home 2011 to 2016 by Birthplace, Language Spoken, Age Group and CensusYear}}</ref> | With increased immigration into Ireland, there has been a substantial increase in the number of people speaking languages. The table below gives figures from the 2016 census of population usually resident and present in the state who speak a language other than English, Irish or a sign language at home.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://statbank.cso.ie/px/pxeirestat/Statire/SelectVarVal/Define.asp?Maintable=EY025&Planguage=0|title=Population Usually Resident and Present in the State who Speak a Language other than English or Irish at Home 2011 to 2016 by Birthplace, Language Spoken, Age Group and CensusYear}}</ref> | ||

| {{Columns-list | | {{Columns-list | | ||

| *''']''' | *''']''' | ||

| ** |

** Arabic 16,072 | ||

| ** ] 1,495 | ** ] 1,495 | ||

| *'''] (Mon–Khmer)''' | *'''] (Mon–Khmer)''' | ||

| Line 79: | Line 81: | ||

| *** ] 14,197 | *** ] 14,197 | ||

| ** ] | ** ] | ||

| *** |

*** German 28,331 | ||

| *** ] 5,156 | *** ] 5,156 | ||

| *** ] 2,228 | *** ] 2,228 | ||

| Line 89: | Line 91: | ||

| *** ] 2,169 | *** ] 2,169 | ||

| **] | **] | ||

| *** |

*** French 54,948 | ||

| *** |

*** Spanish 32,405 | ||

| *** ] 36,683 | *** ] 36,683 | ||

| *** ] 20,833 | *** ] 20,833 | ||

| *** |

*** Italian 14,505 | ||

| **] | **] | ||

| ***] 135,895 | ***] 135,895 | ||

| *** |

*** Russian 21,707 | ||

| *** ] 9,544 | *** ] 9,544 | ||

| *** ] 5,380 | *** ] 5,380 | ||

| *** ] |

*** ] 84,613 | ||

| *** ] 2,895 | *** ] 2,895 | ||

| *** ] 1,196 | *** ] 1,196 | ||

| Line 106: | Line 108: | ||

| *** ] 2,133 | *** ] 2,133 | ||

| *''']''' | *''']''' | ||

| ** |

** Japanese 1,752 | ||

| *''']''' | *''']''' | ||

| ** ] 8,639 | ** ] 8,639 | ||

| Line 113: | Line 115: | ||

| ** ] 991 | ** ] 991 | ||

| *''']''' | *''']''' | ||

| ** |

** Chinese 17,584 | ||

| *''']''' | *''']''' | ||

| **] 2,135 | **] 2,135 | ||

| Line 134: | Line 136: | ||

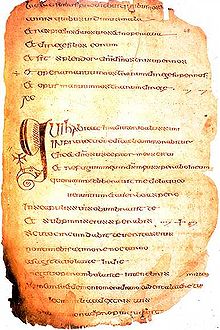

| === Latin === | === Latin === | ||

| ] was introduced by the early Christians by c. 500. It remained a church language, but also was the official written language before and after the Norman conquest in 1171. ] was used by the ] church for services until the ] reforms in 1962–65. Latin is still used in a small number of churches in Dublin,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.stkevinsdublin.ie|title=The Parish of St Kevin, Harrington Street |

] was introduced by the early Christians by c. 500. It remained a church language, but also was the official written language before and after the Norman conquest in 1171. ] was used by the ] church for services until the ] reforms in 1962–65. Latin is still used in a small number of churches in Dublin,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.stkevinsdublin.ie|title=The Parish of St Kevin, Harrington Street – Archdiocese of Dublin|website=Stkevinsdublin.ie|access-date=10 September 2017}}</ref> Cork, ] and ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.latinmassireland.com/mass-listings/|title=The Latin Mass Society of Ireland » Mass Listings|website=Latinmassireland.com|access-date=10 September 2017|archive-date=10 September 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170910221434/http://www.latinmassireland.com/mass-listings/|url-status=usurped}}</ref> | ||

| === Norman language === | === Norman language === | ||

| ] settlers (especially their élite) introduced the ] or ] during the ] of 1169. From Norman derived ], a few words of which continue to be used today for certain legal purposes in both jurisdictions on the island.{{ |

] settlers (especially their élite) introduced the ] or ] during the ] of 1169. From Norman derived ], a few words of which continue to be used today for certain legal purposes in both jurisdictions on the island.{{citation needed|date=September 2021}} | ||

| === Yola === | === Yola === | ||

| Line 143: | Line 145: | ||

| ] was a language which evolved from ], surviving in ] up to the 19th century. | ] was a language which evolved from ], surviving in ] up to the 19th century. | ||

| === |

=== Fingallian === | ||

| {{Main article| |

{{Main article|Fingallian}} | ||

| ] was similar to Yola but spoken in ] up until the mid-19th century. | ] was similar to Yola but spoken in ] up until the mid-19th century. | ||

| === Hiberno-Yiddish === | |||

| {{Main article|Yiddish}} | |||

| Hiberno-Yiddish was spoken by Irish Jews until recently,{{when|date=March 2024}} when most switched to English. It was based on Lithuanian Yiddish. | |||

| == Language education == | == Language education == | ||

| === Republic of Ireland === | === Republic of Ireland === | ||

| In primary schools, most pupils are taught to speak, read and write in |

In primary schools, most pupils are taught to speak, read and write in Irish and English. The vast majority of schools teach through English, although a growing number of '']'' teach through Irish. Most students at second level choose to study English as an ] and Irish and other Continental European languages as ]. Irish is not offered as an L1 language by the Department of Education. Prof. David Little (November 2003) said that there was an urgent need to introduce an L1 Irish Gaelic Curriculum. He quoted from a report by An Bord Curaclaim agus Scrúduithe (The Curriculum and Examinations Board) Report of the Board of Studies for Languages, Dublin 1987: "It must be stressed … that the needs of Irish as L1 at post-primary level have been totally ignored, as at present there is no recognition in terms of curriculum and syllabus of any linguistic differences between learners of Irish as L1 and L2.".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ncca.ie/uploadedfiles/Publications/Plecaipeis.pdf|title=TEANGACHA SA CHURACLAM IAR-BHUNOIDEACHAIS : plécháipéis : Samhain 2003|website=Ncca.ie|access-date=10 September 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171025040605/http://www.ncca.ie/uploadedfiles/Publications/Plecaipeis.pdf|archive-date=25 October 2017|url-status=dead}}</ref> The Continental European languages available for the ] and the ] include French, German, Italian and Spanish; Leaving Certificate students can also study Arabic, Japanese and Russian. Some schools also offer ], ] and ] at second level. | ||

| Students who did not immigrate to Ireland before the age of ten may receive an exemption from learning Irish. Pupils with learning difficulties can also seek exemption. A recent study has revealed that over half of those pupils who got exemption from studying Irish went on to study a Continental European language.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.independent.ie/national-news/irish-language-optouts-soar-1306997.html|title=Irish language opt-outs soar|website=Independent |

Students who did not immigrate to Ireland before the age of ten may receive an exemption from learning Irish. Pupils with learning difficulties can also seek exemption. A recent study has revealed that over half of those pupils who got exemption from studying Irish went on to study a Continental European language.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.independent.ie/national-news/irish-language-optouts-soar-1306997.html|title=Irish language opt-outs soar|website=Irish Independent|access-date=10 September 2017}}</ref> | ||

| The following is a list of foreign languages taken at Leaving Certificate level in 2007, followed by the number as a percentage of all students taking Mathematics for comparison (mathematics is a mandatory subject).<!-- Using maths, because I can't find total candidate number --><ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071119132545/http://examinations.ie/statistics/statistics_2007/LC_2007_breakdownResults_10_or_More.pdf |date=19 November 2007 }} Using mathematics as comparison, as its examination is near-universal at some level and had the largest number of candidates in 2007.</ref> | The following is a list of foreign languages taken at Leaving Certificate level in 2007, followed by the number as a percentage of all students taking Mathematics for comparison (mathematics is a mandatory subject).<!-- Using maths, because I can't find total candidate number --><ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071119132545/http://examinations.ie/statistics/statistics_2007/LC_2007_breakdownResults_10_or_More.pdf |date=19 November 2007 }} Using mathematics as comparison, as its examination is near-universal at some level and had the largest number of candidates in 2007.</ref> | ||

| {| class="wikitable sortable" | {| class="wikitable sortable" | ||

| Line 210: | Line 216: | ||

| | 0.184% | | 0.184% | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] | | ] | ||

| | 117 | | 117 | ||

| | 13 | | 13 | ||

| Line 260: | Line 266: | ||

| ===Northern Ireland=== | ===Northern Ireland=== | ||

| {{main|Languages of Northern Ireland |

{{main|Languages of Northern Ireland|Irish language in Northern Ireland|Ulster Irish}} | ||

| {{further|Languages of the United Kingdom#Northern Ireland}} | {{further|Languages of the United Kingdom#Northern Ireland}} | ||

| The predominant language in the education system in ] is English with |

The predominant language in the education system in ] is English, with Irish-medium schools teaching exclusively in the ]. The ] coordinates the promotion of Irish in English-medium schools. In the GCSE and A Level qualification, Irish is the 3rd most chosen modern language in Northern Ireland, and in the top ten in the UK. Intakes in GCSE Irish and A Level Irish are increasing, and the usage of the language is also increasing. | ||

| == References == | == References == | ||

| Line 273: | Line 279: | ||

| {{Ireland topics|expanded=Culture}} | {{Ireland topics|expanded=Culture}} | ||

| {{Languages of Europe}} | {{Languages of Europe}} | ||

| {{Minority languages of Europe}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

Latest revision as of 19:00, 21 December 2024

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Languages of Ireland" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (September 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Languages of Ireland | |

|---|---|

| Main | English (98%) Irish (RoI: 39.8% claim some ability to speak Irish) Ulster Scots (0.3%) Shelta |

| Immigrant | Polish, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish, Russian, Lithuanian |

| Foreign | French (20%), German (7%), Spanish (3.7%) |

| Signed | Irish Sign Language Northern Ireland Sign Language |

| Keyboard layout | Irish or British QWERTY |

| Source | ebs_243_en.pdf (europa.eu) |

There are a number of languages used in Ireland. Since the late 18th century, English has been the predominant first language, displacing Irish. A large minority claims some ability to use Irish, and it is the first language for a small percentage of the population.

In the Republic of Ireland, under the Constitution of Ireland, both languages have official status, with Irish being the national and first official language.

In Northern Ireland, English is the primary language for 95% of the population, and de facto official language, while Irish is recognised as an official language and Ulster Scots is recognised as a minority language under the Identity and Language (Northern Ireland) Act 2022.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Ireland |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Mythology and folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Art |

| LiteratureComics |

| Music and performing arts |

| Media |

| Sport |

| Monuments |

| Symbols |

Languages

Prehistoric languages

The earliest linguistic records in Ireland are of Primitive Irish, from about the 17th century BCE. Languages spoken in Iron Age Ireland before then are now irretrievable, although there are some claims of traces in Irish toponymy.

Modern languages

English

Main articles: English language, Hiberno-English, and Ulster EnglishMiddle English was first introduced by the Cambro-Norman settlers in the 12th century. It did not initially take hold as a widely spoken language, as the Norman elite spoke Anglo-Norman. In time, many Norman settlers intermarried and assimilated to the Irish cultures and some even became "more Irish than the Irish themselves". Following the Tudor conquest of Ireland and the 1610–15 Ulster Plantation, particularly in the old Pale, Elizabethan English became the language of court, justice, administration, business, trade and of the landed gentry. Monolingual Irish speakers were generally of the poorer and less educated classes with no land. Irish was accepted as a vernacular language, but then as now, fluency in English was an essential element for those who wanted social mobility and personal advancement. After the legislative Union of Great Britain and Ireland's succession of Irish Education Acts that sponsored the Irish national schools and provided free public primary education, Hiberno-English replaced the Irish language. Since the 1850s, English medium education was promoted by both the UK administration and the Roman Catholic Church. This greatly assisted the waves of immigrants forced to seek new lives in the US and throughout the Empire after the Famine. Since then the various local Hiberno-English dialects comprise the vernacular language throughout the island.

The 2002 census found that 103,000 British citizens were living in the Republic of Ireland, along with 11,300 from the US and 8,900 from Nigeria, all of whom would speak other dialects of English. The 2006 census listed 165,000 people from the UK, and 22,000 from the US. The 2016 census reported a decline in UK nationals to the 2002 level: 103,113.

Irish

Main articles: Irish language, List of Irish-language media, and Gaelic revivalThe original Primitive Irish was introduced by Celtic speakers. Primitive Irish gradually evolved into Old Irish, spoken between the 5th and the 10th centuries, and then into Middle Irish. Middle Irish was spoken in Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man through the 12th century, when it began to evolve into modern Irish in Ireland, Scottish Gaelic in Scotland, and the Manx language in the Isle of Man. Today, Irish is recognized as the first official language of the Republic of Ireland and is officially recognized in the European Union. Communities that speak Irish as their first language, generally in sporadic regions on the island's west coast, are collectively called the Gaeltacht.

In the 2016 Irish census, 8,068 census forms were completed in Irish, and just under 74,000 of the total (1.7%) said they spoke it daily. The total number of people who answered 'yes' to being able to speak Irish to some extent in April 2016 was 1,761,420, 39.8 percent of respondents.

Although the use of Irish in educational and broadcasting contexts has increased notably with the 600 plus Irish-language primary/secondary schools and creches , English is still overwhelmingly dominant in almost all social, economic, and cultural contexts. In the media, there is an Irish-language TV station TG4, Cúla 4 a children's channel on satellite, 5 radio stations such as the national station RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta, Raidió na Life in Dublin, as well as Raidió Fáilte in Belfast and a youth radio station Raidió Rí-Rá. There are also several newspapers, such as Tuairisc.ie, Meon Eile, Seachtain (a weekly supplement in the Irish Independent), and several magazines including Comhar, Feasta, and An Timire. There are also occasional columns written in Irish in English-language newspapers, including The Irish Times, The Irish News, The Irish Examiner, Metro Éireann, Irish Echo, the Evening Echo, and the Andersonstown News. All of the 40 or so radio stations in the Republic have to have some weekly Irish-language programming to obtain their broadcasting license. Similarly, RTÉ runs Nuacht, a news show, in Irish and Léargas, a documentary show, in Irish with English subtitles. The Official Languages Act 2003 gave many new rights to Irish citizens concerning the Irish language, including the use of Irish in court proceedings. All Dáil debates are to be recorded in Irish also. In 2007, Irish became the 21st official language of the European Union.

Ulster Scots

Main article: Ulster Scots dialectsUlster Scots, sometimes called Ullans, is a dialect of Scots spoken in some parts of County Donegal and Northern Ireland. It is promoted and supported by the Ulster Scots Agency, a cross-border body. Its status as an independent language as opposed to a dialect of Scots has been debated.

Shelta

Main articles: Shelta and Irish TravellersShelta is a cant, based upon both Irish and English, generally spoken by the Irish Traveller community. It is known as Gammon to Irish speakers and Shelta by the linguistic community. It is a mixture of English and Irish, with Irish being the lexifier language.

Shelta is a secret language, with a refusal by the Travellers to share with non-travellers, named "Buffers". When speaking Shelta in front of Buffers, Travellers will disguise the structure so as to make it seem like they aren't speaking Shelta at all. There is fear that if outsiders know the entirety of the language, it will be used to bring further discrimination to the Traveller community.

Sign languages

Main articles: Irish Sign Language and Northern Ireland Sign LanguageIrish Sign Language (ISL) is the sign language of most of Ireland. It has little relation to either spoken Irish or English, and is more closely related to French Sign Language (LSF).

Northern Ireland Sign Language is used in Northern Ireland, and is related to both ISL and BSL in various ways. ISL is also used in Northern Ireland.

Immigrant languages

With increased immigration into Ireland, there has been a substantial increase in the number of people speaking languages. The table below gives figures from the 2016 census of population usually resident and present in the state who speak a language other than English, Irish or a sign language at home.

- Afro-Asiatic

- Arabic 16,072

- Somali 1,495

- Austroasiatic (Mon–Khmer)

- Vietnamese 1,260

- Austronesian

- Dravidian

- Indo-European

- Baltic

- Lithuanian 35,362

- Latvian 14,197

- Germanic

- Indo-Iranian

- Romance

- French 54,948

- Spanish 32,405

- Romanian 36,683

- Portuguese 20,833

- Italian 14,505

- Slavic

- Other Indo-European

- Albanian 2,133

- Baltic

- Japonic

- Japanese 1,752

- Niger–Congo

- Sino-Tibetan

- Chinese 17,584

- Tai–Kadai

- Thai 2,135

- Turkic

- Turkish 2,047

- Uralic

- Other Northern European languages 1,090

- Other Southern European languages 857

- Other Eastern European languages 1,137

- Other Asian languages 4,465

- Other African languages 4,342

- Other languages 23,451

Extinct languages

None of these languages were spoken by a majority of the population, but are of historical interest, giving loan words to Irish and Hiberno-English.

Latin

Late Latin was introduced by the early Christians by c. 500. It remained a church language, but also was the official written language before and after the Norman conquest in 1171. Ecclesiastical Latin was used by the Roman Catholic church for services until the Vatican II reforms in 1962–65. Latin is still used in a small number of churches in Dublin, Cork, Limerick and Stamullen.

Norman language

Norman settlers (especially their élite) introduced the Norman or Anglo-Norman language during the Norman invasion of Ireland of 1169. From Norman derived "Law French", a few words of which continue to be used today for certain legal purposes in both jurisdictions on the island.

Yola

Main article: Forth and Bargy dialectYola was a language which evolved from Middle English, surviving in County Wexford up to the 19th century.

Fingallian

Main article: FingallianFingallian was similar to Yola but spoken in Fingal up until the mid-19th century.

Hiberno-Yiddish

Main article: YiddishHiberno-Yiddish was spoken by Irish Jews until recently, when most switched to English. It was based on Lithuanian Yiddish.

Language education

Republic of Ireland

In primary schools, most pupils are taught to speak, read and write in Irish and English. The vast majority of schools teach through English, although a growing number of gaelscoil teach through Irish. Most students at second level choose to study English as an L1 language and Irish and other Continental European languages as L2 languages. Irish is not offered as an L1 language by the Department of Education. Prof. David Little (November 2003) said that there was an urgent need to introduce an L1 Irish Gaelic Curriculum. He quoted from a report by An Bord Curaclaim agus Scrúduithe (The Curriculum and Examinations Board) Report of the Board of Studies for Languages, Dublin 1987: "It must be stressed … that the needs of Irish as L1 at post-primary level have been totally ignored, as at present there is no recognition in terms of curriculum and syllabus of any linguistic differences between learners of Irish as L1 and L2.". The Continental European languages available for the Junior Certificate and the Leaving Certificate include French, German, Italian and Spanish; Leaving Certificate students can also study Arabic, Japanese and Russian. Some schools also offer Ancient Greek, Hebrew Studies and Latin at second level.

Students who did not immigrate to Ireland before the age of ten may receive an exemption from learning Irish. Pupils with learning difficulties can also seek exemption. A recent study has revealed that over half of those pupils who got exemption from studying Irish went on to study a Continental European language. The following is a list of foreign languages taken at Leaving Certificate level in 2007, followed by the number as a percentage of all students taking Mathematics for comparison (mathematics is a mandatory subject).

| Language | Higher Level | Ordinary Level | Total candidates | % of Maths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 English | 31,078 | 17,277 | 48,355 | 98.79% |

| L2 Irish | 13,831 | 25,662 | 44,018 | 89.94% |

| L2 French | 13,770 | 14,035 | 27,805 | 56.695% |

| L2 German | 4,554 | 2,985 | 7,539 | 15.372% |

| L2 Spanish | 1,533 | 1,127 | 2,660 | 5.424% |

| L2 Italian | 140 | 84 | 224 | 0.457% |

| Latin | 111 | 111 | 0.226% | |

| L2 Japanese | 90 | 90 | 0.184% | |

| L2 Arabic | 117 | 13 | 130 | 0.265% |

| L2 Russian | 181 | 181 | 0.369% | |

| L2 Latvian | 32 | 32 | 0.065% | |

| L2 Lithuanian | 61 | 61 | 0.125% | |

| L2 Dutch | 16 | 16 | 0.033% | |

| L2 Portuguese | 27 | 27 | 0.055% | |

| L2 Polish | 53 | 53 | 0.108% | |

| L2 Romanian | 25 | 25 | 0.051% |

Northern Ireland

Main articles: Languages of Northern Ireland, Irish language in Northern Ireland, and Ulster Irish Further information: Languages of the United Kingdom § Northern IrelandThe predominant language in the education system in Northern Ireland is English, with Irish-medium schools teaching exclusively in the Irish language. The ULTACH Trust coordinates the promotion of Irish in English-medium schools. In the GCSE and A Level qualification, Irish is the 3rd most chosen modern language in Northern Ireland, and in the top ten in the UK. Intakes in GCSE Irish and A Level Irish are increasing, and the usage of the language is also increasing.

References

- "SPECIAL EUROBAROMETER 386 Europeans and their Languages" (PDF). Ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2016.

- ^ "Irish Language and the Gaeltacht – CSO – Central Statistics Office". cso.ie. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- Book (eISB), electronic Irish Statute. "electronic Irish Statute Book (eISB)". www.irishstatutebook.ie. Art. 8. Retrieved 16 October 2024.

- "Identity and Language (Northern Ireland) Act 2022".

- "Language and identity laws could spell significant change". BBC News. 11 December 2022.

- D. Ó Corrain, 'A future for Irish placenames', in: A. Ó Maolfabhail, The placenames of Ireland in the third millennium, Ordnance Survey for the Place names Commission, Dublin (1992), p. 44.

- "It's in the blood. The Citizenship referendum in Ireland". Threemonkeysonline.com. 1 June 2004. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- . 25 March 2009 https://web.archive.org/web/20090325005303/http://www.cso.ie/census/documents/Final%20Principal%20Demographic%20Results%202006.pdf. Archived from the original on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "UK – CSO – Central Statistics Office".

- "Broadcasting Act 2001" (PDF). 14 October 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- "Official Languages Act 2003" (PDF). Oireachtas na hÉireann. 30 October 2003. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- "Aw Ae Oo—Scots in Scotland and Ulster" (PDF). Scots-online.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 April 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- Velupillai, Viveka (2015). Pidgins, Creoles and Mixed Languages. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 381. ISBN 978-90-272-5271-5.

- Velupillai, Viveka (2015). Pidgins, Creoles and Mixed Languages. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 80. ISBN 978-90-272-5271-5.

- Velupillai, Viveka (2015). (2015). Pidgins, Creoles and Mixed Languages. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 80. ISBN 978-90-272-5271-5.

- Binchy, Alice (1994). Irish Travellers: Culture and Ethnicity. Belfast: W & G Baird Ltd. p. 134. ISBN 0-85389-493-0.

- "Population Usually Resident and Present in the State who Speak a Language other than English or Irish at Home 2011 to 2016 by Birthplace, Language Spoken, Age Group and CensusYear".

- "The Parish of St Kevin, Harrington Street – Archdiocese of Dublin". Stkevinsdublin.ie. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- "The Latin Mass Society of Ireland » Mass Listings". Latinmassireland.com. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- "TEANGACHA SA CHURACLAM IAR-BHUNOIDEACHAIS : plécháipéis : Samhain 2003" (PDF). Ncca.ie. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 October 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- "Irish language opt-outs soar". Irish Independent. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- Results of Exams in 2007 Archived 19 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine Using mathematics as comparison, as its examination is near-universal at some level and had the largest number of candidates in 2007.

External links

| Languages of Ireland | |

|---|---|

| Official languages | |

| Minority languages | |

| Sign languages | |

| Languages of Europe | |

|---|---|

| Sovereign states |

|

| States with limited recognition | |

| Dependencies and other entities | |

| Other entities | |

| Minority languages of Europe | |

|---|---|

| European Union | |

| Other European states | |

| States with limited recognition | |

| Dependencies and other territories | |