| Revision as of 07:53, 8 May 2003 editGCarty (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users17,068 editsmNo edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 04:39, 22 December 2024 edit undoSporkBot (talk | contribs)Bots1,245,087 editsm Remove template per TFD outcomeNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|1950 film by Akira Kurosawa}} | |||

| '''Rashomon''' (羅生門) is a Japanese ] motion picture and one of ]'s masterpieces, starring ]. Based on the story by ], it describes a crime through the widely differing accounts of half a dozen witnesses, including the perpetrator. | |||

| {{Other uses}} | |||

| {{Use American English|date=July 2020}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=July 2020}} | |||

| {{Infobox film | |||

| | name = Rashomon | |||

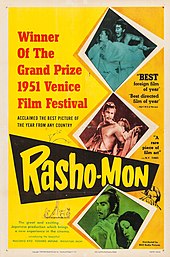

| | image = Rashomon poster.jpg | |||

| | caption = Theatrical release poster | |||

| | director = ] | |||

| | producer = Jingo Minoura | |||

| | screenplay = {{plainlist| | |||

| * Akira Kurosawa | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | based_on = {{Based on|"]"|]}}<!-- The film credits Ryūnosuke Akutagawa's "In a Grove" as the film's only source material --> | |||

| | starring = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | music = ] | |||

| | cinematography = ] | |||

| | editing = Shigeo Nishida | |||

| | studio = ] | |||

| | distributor = Daiei | |||

| | released = {{film date|1950|8|25|]|1950|8|26|Japan}} | |||

| | runtime = 88 minutes | |||

| | country = Japan | |||

| | language = Japanese | |||

| | budget = {{JPY|15–20 million}} | |||

| | gross = {{USD|1 million|long=no}}<!--{{efn|This figure represents the original box office gross of {{USD|800,000|long=no}} ({{JPY|300 million}}) and grosses from subsequent theatrical re-releases.}}--> | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Nihongo|'''''Rashomon'''''|羅生門|Rashōmon|lead=yes|}}{{efn|The Japanese title is ] from the ] gate built in ] during the ] and has no explicit English translation. However, Jan Walls claimed that it means "web life gate" or "net life gate", with "web life" referring to '']''.{{sfn|Davis|Anderson|Walls|2015|p=15}} Upon its initial American release, some Western sources erroneously cited the translation of the film's title as "''In the Forest''".{{sfn|''Chicago Tribune''|1952|p=169}}<ref name="Time"/>}} is a 1950 Japanese '']'' film directed by ] from a screenplay he co-wrote with ]. Starring ], ], ], and ], it follows various people who describe how a ] was murdered in a forest. The plot and characters are based upon ]'s short story "]", with the title and framing story taken from Akutagawa's "]". Every element is largely identical, from the murdered samurai speaking through a ] to the bandit in the forest, the monk, the assault of the wife, and the dishonest retelling of the events in which everyone shows their ideal self by lying.<!--<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.cinematoday.jp/news/N0105709 |title=Akira Kurosawa Rashomon|website=www.cinematoday.jp|date=December 19, 2018 |language=ja|access-date=2020-06-11}}</ref>--> | |||

| Because of the film's success, the word "Rashomon" has come to refer to (in English and in other languages) a situation wherein the truth of an event becomes difficult to verify due to the conflicting nature of different witnesses. | |||

| Production began in 1948 at Kurosawa's regular production firm ] but was canceled as it was viewed as a financial risk. Two years later, ] pitched ''Rashomon'' to ] upon the completion of Kurosawa's '']''. Daiei initially turned it down but eventually agreed to produce and distribute the film. ] lasted from July 7 to August 17, 1950, taking place primarily in ] on an estimated {{JPY|15–20 million}} budget. When creating the film's visual style, Kurosawa and cinematographer ] experimented with various methods such as pointing the camera at the sun, which was considered taboo. Post-production took only one week and was decelerated by two fires. | |||

| The film has been remade, officially and unofficially, many times; in the ] a ] remake, credited to Kurosawa and named ''The Outrage'', was made in ] with ], ] and ]. | |||

| ''Rashomon'' premiered at the ] on August 25, 1950, and was distributed throughout Japan the following day, to moderate commercial success, becoming Daiei's fourth highest-grossing film of 1950. Japanese critics praised the experimental direction and cinematography but criticized its adapting of Akutagawa's story and complexity. Upon winning the ] at the ], ''Rashomon'' became the first ] to attain significant international reception,<!--{{sfn|Dixon|Foster|2008|p=203}}{{sfn|Russell|2011|loc=Chapter 4: ''The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa''}}--> garnering critical acclaim and earning roughly {{USD|800,000|long=no}} abroad. It later won ] at the ],{{efn|The ] presented the category as an ] until 1956.}} and was nominated for ] at the ]. | |||

| '''See also''': ] | |||

| ''Rashomon'' is now considered one of the ] and among the most influential movies from the 20th century. It pioneered the ], a plot device that involves various characters providing subjective, alternative, and contradictory versions of the same incident. In 1999, critic ] asserted that "the film's title has become synonymous with its chief narrative conceit". | |||

| ==Plot== | |||

| In ] ], a woodcutter and a priest, taking shelter from a downpour under the ], recount a story of a recent assault and murder. Baffled at conflicting accounts of the same event, the woodcutter and the priest are joined by a commoner. The woodcutter claims he had found the body of a murdered samurai three days earlier, alongside the samurai's cap, his wife's hat, cut pieces of rope, and an amulet. The priest claims he had seen the samurai travel with his wife on the day of the murder. Both testify in court before a policeman presents the main suspect, a captured ] named Tajōmaru. | |||

| In Tajōmaru's version of events, he follows the couple after spotting them traveling in the woods. He tricks the samurai into leaving the trail by lying about finding a burial pit filled with ancient artifacts. He subdues the samurai and attempts to ] his wife, who tries to defend herself with a dagger. Tajōmaru then seduces the wife, who, ashamed of the dishonor of having been with two men, asks Tajōmaru to duel her husband so she may go with the man who wins. Tajōmaru agrees; the duel ends with Tajōmaru killing the samurai. He then finds the wife has fled. | |||

| The wife, having been found by the police, delivers a different testimony; in her version of events, Tajōmaru leaves immediately after assaulting her. She frees her husband from his bonds, but he stares at her with contempt and loathing. The wife tries to threaten him with her dagger but then faints from panic. She awakens to find her husband dead, with the dagger in his chest. In shock, she wanders through the forest until coming upon a pond and attempts to drown herself but fails. | |||

| The samurai's testimony is heard through a ]. In his version of events, Tajōmaru asks the wife to marry him after the assault. To the samurai's shame, she accepts, asking Tajōmaru to kill the samurai first. This disgusts Tajōmaru, who gives the samurai the choice to let her go or have her killed. The wife then breaks free and flees. Tajōmaru unsuccessfully gives chase. After being set free by an apologetic Tajōmaru, the samurai kills himself with the dagger. Later, he feels someone remove the dagger from his chest, but cannot tell who. | |||

| The woodcutter proclaims that all three stories are falsehoods and admits that he saw the samurai killed by a sword instead of a dagger. The commoner pressures the woodcutter to admit that he had seen the murder but lied to avoid getting in trouble. In the woodcutter's version of events, Tajōmaru begs the wife to marry him. She instead frees her husband, expecting him to kill Tajōmaru. The samurai refuses to fight, unwilling to risk his life for a ruined woman. Tajōmaru rescinds his promise to marry the wife; the wife rebukes them both for failing to keep their promises. The two men unwillingly enter into a duel; the samurai is disarmed and begs for his life, and Tajōmaru kills him. The wife flees, and Tajōmaru steals the samurai's sword and limps away. | |||

| The woodcutter, the priest, and the commoner are interrupted by the sound of a crying baby. They find a child abandoned in a basket along with a kimono and an amulet; the commoner steals the items, for which the woodcutter rebukes him. The commoner deduces that the woodcutter had lied not because he feared getting in trouble, but because he had stolen the wife's dagger to sell for food. | |||

| Meanwhile, the priest attempts to soothe the baby. The woodcutter attempts to take the child after the commoner's departure; the priest, having lost his faith in humanity after the events of the trial and the commoner's actions, recoils. The woodcutter explains that he intends to raise the child. Having seen the woodcutter's well-meaning intentions, the priest announces that his faith in men has been restored. As the woodcutter prepares to leave, the rain stops and the clouds part, revealing the sun. | |||

| ==Cast== | |||

| ] and ]]] | |||

| * ] as Tajōmaru, the bandit | |||

| * ] as Takehiro Kanazawa, the samurai | |||

| * ] as Masago, Kanazawa's wife | |||

| * ] as the woodcutter | |||

| * ] as the priest | |||

| * {{Ill|Kichijirō Ueda|ja|上田吉二郎}} as the commoner | |||

| * ] as the '']'' | |||

| * ] as the policeman | |||

| ==Production== | |||

| {{Expand Japanese|topic=cult|section=yes|date=August 2024}} | |||

| ===Development=== | |||

| According to ], ] began developing the film circa 1948, and both Kurosawa's regular production studio ] and its financing company, Toyoko Company, refused to produce the film, with the latter fearing it would be a precarious production. Following the completion of '']'', ] offered the script to Daiei who also initially rejected it.{{sfn|Richie|1965|p=70}}{{Sfn|Galbraith|2002|p=128}}<ref name=":0">{{cite book |last1=Ryfle |first1=Steve |url=https://archive.org/details/ishiro-honda-a-life-in-film-from-godzilla-to-kurosawa |title=Ishiro Honda: A Life in Film, from Godzilla to Kurosawa |last2=Godziszewski |first2=Ed |publisher=] |year=2017 |isbn=9780819570871 |pages=53}}</ref> | |||

| Regarding ''Rashomon'', Kurosawa said: <blockquote>I like silent pictures and I always have... I wanted to restore some of this beauty. I thought of it, I remember in this way: one of the techniques of modern art is simplification, and that I must therefore simplify this film."</blockquote> | |||

| <!--Accordingly, there are only three settings in the film: ] gate, the woods and the ]. The gate and the courtyard are very simply constructed and the ] is real. This is partly due to the low budget that Kurosawa was given from Daiei. | |||

| --> | |||

| As with most films produced in post-war Japan, reports on the budget of ''Rashomon'' are scarce and differ.<ref name="BBC">{{cite web|url=https://www.bfi.org.uk/features/rashomon-effect-akira-kurosawa |title=The Rashomon effect: a new look at Akira Kurosawa's cinematic milestone of post-truth |date=January 4, 2023 |last=Sharp |first=Jasper |work=] |access-date=August 5, 2024}}</ref> In 1952, ] said that the film's production cost was {{JPY|20 million}}, and suggested that advertising and other expenses brought the overall budget to {{JPY|35 million}}.{{sfn|Jitsugyo no Nihon Sha|1952|p=164}} The following year, the ] reported that the {{USD|85,000|long=no}} spent on Kurosawa's '']'' (1952) was over twice the budget of ''Rashomon''.{{sfn|National Board of Review|1953|p=290}} According to the ] in 1971, ''Rashomon'' had a budget of {{JPY|15 million}} or {{USD|42,000|long=no}}.{{sfn|Brandon|1971|p=127}} Reports on the budget in Western currency vary: ''The Guinness Book of Movie Facts and Feats'' cited it as {{USD|40,000|long=no}},{{sfn|Robertson|1991|p=33}} '']'' and ] noted a reputed {{USD|140,000|long=no}} figure,{{sfn|Falk|1951|p=4X}}{{sfn|Galbraith|2002|p=132}} and a handful of other sources have claimed that it cost as high as {{USD|250,000|long=no}}. Jasper Sharp disputed the latter number in an article for the ], since it would have been equal to {{JPY|90 million}} at the time of the film's production. He added that it "seems highly unlikely given that the 125 million yen, approximately $350,000, that Kurosawa subsequently spent on '']'' four years later made this film by far the most expensive domestic production up to this point".<ref name="BBC"/> | |||

| === Writing === | |||

| Kurosawa wrote the screenplay while staying at a '']'' in ] with his friend ], who was scripting '']'' (1951). The pair regularly commenced writing their respective films at 9:00 a.m. and would give feedback on each other's work after each completed roughly twenty pages. According to Honda, Kurosawa soon refused to read ''The Blue Pearl'' after a couple of days but "of course, he still made me read his".<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| ===Casting=== | |||

| Kurosawa had initially wanted the cast of eight to consist entirely of previous collaborators, specifically counseling ] and ]. He also suggested that ]—who had played the lead in '']'' (1946)—portray the wife, but she was not cast since her brother-in-law, filmmaker ], was against it; Hara would subsequently appear in Kurosawa's next film, '']'' (1951).<ref>{{Cite web |last=Ishii |first=Taeko |date=June 10, 2020 |title=The Truth About Hara Setsuko: Behind the Legend of the Golden Age Film Star |url=https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-topics/bg900161/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200615173144/https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-topics/bg900161/ |archive-date=June 15, 2020 |access-date=August 12, 2024 |website=Nippon.com |language=en}}</ref> Daiei executives then recommended ], believing she would make the film easier to market. Kurosawa agreed to cast her upon seeing her show enthusiasm for the project by shaving her eyebrows before going for a make-up test. | |||

| When Kurosawa shot ''Rashomon'', the actors and the staff lived together, a system Kurosawa found beneficial. He recalls: <blockquote>We were a very small group and it was as though I was directing ''Rashomon'' every minute of the day and night. At times like this, you can talk everything over and get very close indeed.<ref>Qtd. in Richie, ''Films''.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| ===Filming=== | |||

| Due to its small budget the film had only three sets: the gate; the forest scene; and the police courtyard. Filming began on 7 July 1950 and ended 17 August. After a week's work on post-production, it was released in Tokyo on 25 August.<ref>{{Cite web |date=March 24, 2024 |title=Rashomon |url=https://akirakurosawa.info/rashomon/ |access-date=March 24, 2024 |website=Akira Kurosawa Info}}</ref> | |||

| The ], ], contributed numerous ideas, technical skill and expertise in support for what would be an experimental and influential approach to cinematography. For example, in one sequence, there is a series of single close-ups of the bandit, then the wife and then the husband, which then repeats to emphasize the triangular relationship between them.<ref>''The World of Kazuo Miyagawa'' (original title: ''The Camera Also Acts: Movie Cameraman Miyagawa Kazuo'') director unknown. NHK, year unknown. Television/Criterion blu-ray</ref> | |||

| The use of contrasting shots is another example of the film techniques used in ''Rashomon''. According to ], the length of time of the shots of the wife and of the bandit is the same when the bandit is acting barbarically and the wife is hysterically crazy.<ref>Richie, ''Films''.</ref> | |||

| ''Rashomon'' had camera shots that were directly into the sun. Kurosawa wanted to use natural light, but it was too weak; they solved the problem by using a mirror to reflect the natural light. The result makes the strong sunlight look as though it has traveled through the branches, hitting the actors. The rain in the scenes at the gate had to be tinted with black ink because camera lenses could not capture the water pumped through the hoses.<ref name=kurosawa>{{cite web|title=Akira Kurosawa on Rashomon|url=http://www.criterion.com/current/posts/196-akira-kurosawa-on-rashomon|access-date=May 2, 2022|author=Akira Kurosawa |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101128061133/http://www.criterion.com/current/posts/196-akira-kurosawa-on-rashomon |archive-date=November 28, 2010 |url-status=dead |quote=when the camera was aimed upward at the cloudy sky over the gate, the sprinkle of the rain couldn’t be seen against it, so we made rainfall with black ink in it. }}</ref> | |||

| ===Lighting=== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] compliments Kurosawa's use of "dappled" light throughout the film, which gives the characters and settings further ambiguity.<ref>{{cite AV media|people=Robert Altman|date=|title=Rashomon|type=DVD|contribution=Introduction|publisher=]|quote=One typical example from the movie which shows the ambiguity of the characters is when the bandit and the wife talk to each other in the woods, the light falls on the person who is not talking and shows the amused expressions, this represents the ambiguity present.}}</ref> In his essay "Rashomon", ] suggests that the film (unusually) uses sunlight to symbolize evil and sin in the film, arguing that the wife gives in to the bandit's desires when she sees the sun.{{cn|date=December 2024}} | |||

| Professor Keiko I. McDonald opposes Sato's idea in her essay "The Dialectic of Light and Darkness in Kurosawa's ''Rashomon''." McDonald says the film conventionally uses light to symbolize "good" or "reason" and darkness to symbolize "bad" or "impulse". She interprets the scene mentioned by Sato differently, pointing out that the wife gives herself to the bandit when the sun slowly fades out. McDonald also reveals that Kurosawa was waiting for a big cloud to appear over Rashomon gate to shoot the final scene in which the woodcutter takes the abandoned baby home; Kurosawa wanted to show that there might be another dark rain any time soon, even though the sky is clear at this moment. McDonald regards it as unfortunate that the final scene appears optimistic because it was too sunny and clear to produce the effects of an overcast sky. | |||

| ===Post-production=== | |||

| ] writes in ''The Impact of Rashomon'' that Kurosawa often shot a scene with several cameras at the same time, so that he could "cut the film freely and splice together the pieces which have caught the action forcefully as if flying from one piece to another." Despite this, he also used short shots edited together that trick the audience into seeing one shot; ] says in his essay that "there are 407 separate shots in the body of the film ... This is more than twice the number in the usual film, and yet these shots never call attention to themselves."{{cn|date=November 2024}} | |||

| Due to setbacks and some lost audio, the crew took the urgent step of bringing Mifune back to the studio after filming to record another line. Recording engineer ] added it to the film along with the music, using a different microphone.<ref>], ''Waiting on the Weather: Making Movies with Akira Kurosawa'', Stone Bridge Press, Inc., 1 September 2006, p. 90, {{ISBN|1933330090}}.</ref> | |||

| The film was scored by ], who is among the most respected of Japanese composers.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|url=http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-3406802357.html |title=Hayasaka, Fumio – Dictionary definition of Hayasaka, Fumio | Encyclopedia.com: FREE online dictionary |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia.com |access-date=2011-10-21}}</ref> At the director's request, he scored a ] for the woman's story.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Kurosawa|first1=Akira |date=1982 |title=Something like an autobiography |last2=Bock |first2=Audie E. |publisher=Knopf |isbn=978-0-394-50938-9 |edition=1st |language=English |location=New York, N.Y}}</ref> | |||

| ==Allegorical and symbolic content== | |||

| {{See also|Rashomon effect}} | |||

| The film depicts the rape of a woman and the murder of her ] husband through the widely differing accounts of four ]es, including the bandit-rapist, the wife, the dead man (speaking through a medium), and lastly the woodcutter, the one witness who seems the most objective and least biased. The stories are ] and even the final version may be seen as motivated by factors of ego and saving face. The actors kept approaching Kurosawa wanting to know the truth, and he claimed the point of the film was to be an exploration of multiple realities rather than an exposition of a particular truth. Later film and television use of the "]" focuses on revealing "the truth" in a now conventional technique that presents the final version of a story as the truth, an approach that only matches Kurosawa's film on the surface. | |||

| Due to its emphasis on the subjectivity of truth and the uncertainty of factual accuracy, ''Rashomon'' has been read by some as an allegory of the defeat of Japan at the end of World War II. James F. Davidson's article, "Memory of Defeat in Japan: A Reappraisal of ''Rashomon''" in the December 1954 issue of the ''Antioch Review'', is an early analysis of the World War II defeat elements.<ref>The article has since appeared in some subsequent ''Rashomon'' anthologies, including ''Focus on Rashomon'' {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221101033706/https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0137529724|date=November 1, 2022}} in 1972 and ''Rashomon (Rutgers Film in Print)'' {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221101033711/https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0813511798|date=November 1, 2022}} in 1987. Davidson's article is referred to in other sources, in support of various ideas. These sources include: ''The Fifty-Year War: Rashomon, After Life, and Japanese Film Narratives of Remembering'' a 2003 article by Mike Sugimoto in ''Japan Studies Review'' Volume 7 {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20051128103956/http://www.fiu.edu/~asian/jsr/Table%20of%20Cont%202003.pdf|date=November 28, 2005}}, ''Japanese Cinema: Kurosawa's Ronin'' by G. Sham {{cite web |title=Kurosawa?s Ronin |url=http://lavender.fortunecity.com/attenborough/487/kurosawa.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060115183656/http://lavender.fortunecity.com/attenborough/487/kurosawa.html |archive-date=2006-01-15 |access-date=2005-11-16}}, ''Critical Reception of Rashomon in the West'' by Greg M. Smith, ''Asian Cinema'' 13.2 (Fall/Winter 2002) 115-28 {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050317064027/http://www2.gsu.edu/~jougms/Rashomon.htm|date=March 17, 2005}}, ''Rashomon vs. Optimistic Rationalism Concerning the Existence of "True Facts"'' {{dead link|date=April 2018|bot=InternetArchiveBot|fix-attempted=yes}}, ''Persistent Ambiguity and Moral Responsibility in Rashomon'' by Robert van Es and ''Judgment by Film: Socio-Legal Functions of Rashomon'' by Orit Kamir {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150915192915/http://sitemaker.umich.edu/Orit_Kamir/files/rashomon.pdf|date=2015-09-15}}.</ref> Another allegorical interpretation of the film is mentioned briefly in a 1995 article, "Japan: An Ambivalent Nation, an Ambivalent Cinema" by David M. Desser.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://acdis.illinois.edu/publications/207/publication-HiroshimaARetrospective.html|title=Hiroshima: A Retrospective |work=illinois.edu |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130820030628/https://acdis.illinois.edu/publications/207/publication-HiroshimaARetrospective.html |archive-date=August 20, 2013 |access-date=May 2, 2022}}</ref> Here, the film is seen as an allegory of the ] and Japanese defeat. It also briefly mentions James Goodwin's view on the influence of post-war events on the film. However, the film's source material, "In a Grove", was published in 1922, so any postwar allegory would have resulted from Kurosawa's additions rather than the story about the conflicting accounts. Historian and critic David Conrad has noted that the use of rape as a plot point came at a time when American ] authorities had recently stopped censoring Japanese media and belated accounts of rapes by occupation troops began to appear in Japanese newspapers. Moreover, Kurosawa and other filmmakers were not allowed to make '']'' during the early part of the occupation, so setting a film in the distant past was a way to reassert domestic control over cinema.<ref>{{cite book| last=Conrad|first=David A.|title=Akira Kurosawa and Modern Japan|year=2022|pages=81–84|publisher=McFarland & Co.|isbn=978-1-4766-8674-5}}</ref> | |||

| ==Release== | |||

| ===Box office=== | |||

| ] | |||

| The premiere of ''Rashomon'' took place at the ] on August 25, 1950, in Tokyo, and was distributed nationwide by Daiei the next day. It was an instant box office success, leading several theaters to continue to play it for two or three weeks rather than a Japanese film's regular one-week theatrical run. ] reported that the film was Daiei's third highest-grossing film released between September 1949 and August 1950, having earned over {{JPY|10 million}}.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uvpIAAAAMAAJ|title=Film Yearbook 1951 Edition |date=1951 |via=] |page=27, 52 |publisher=] |access-date=August 6, 2024 <!--|quote=(p27): 八月の「羅生門」(黒沢明演出、三船敏郎、森雅之、京マチ子主演)は質実ともに同月の興行界を席巻し、二週、三週のロングを行った系統館も相当あつた。(p52): 四九年九月から五〇年八月までに発賣された大映作品の全國配收ベスト・ 10 は左の通りである。 1 位「続蛇姫道中」 2 位「甲賀屋敷」 3 位「羅生門」 4 位「蛇姫道中」 5 位「千両肌」 6 位「遙かなり母の国」 7 位「痴人の愛」(以上いずれも一千万円以上) -->}}</ref> In general, the film was Daiei's fourth-highest-grossing film of 1950. ] claimed that it was also one of the top ten highest-earning films in Japan that year.<ref name="Richie">{{cite book |last=Richie |first=Donald |date=2001 |title=A Hundred Years of Japanese Film. A Concise History |location=Tokyo |publisher=Kodansha International |page=139 |isbn=9784770029959 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=s7-_Gon5-a0C&pg=PA139}}</ref> | |||

| The film later became Kurosawa's first major international hit.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Baltake |first1=Joe |title=Kurosawa deserved master status |url=https://www.newspapers.com/image/504336842/ |access-date=19 April 2022 |work=] |via=] |date=9 September 1998 |page=B6 |url-access=subscription}}</ref> It was released theatrically in the United States by ] on December 26, 1951, in both subtitled and dubbed versions.{{sfn|Galbraith IV|1994|p=309}}<!--] ordered two minutes to be cut from the film (source: https://archive.org/details/variety186-1952-04/page/n29/mode/2up?q=rashomon)--> In Europe, the film sold {{formatnum:{{#expr:246893+118400}}|}} tickets in France and Spain,<ref>{{cite web |title=«Расёмон» (Rashomon, 1950) |url=https://www.kinopoisk.ru/film/388/ |website=] |language=ru |access-date=19 April 2022}}</ref> and 8,292 tickets in other European countries between 1996 and 2020,<ref>{{cite web |title=Rashômon |url=https://lumiere.obs.coe.int/movie/14176 |website=] |access-date=19 April 2022}}</ref> for a combined total of at least {{formatnum:{{#expr:246893+118400+8292}}|}} tickets sold in Europe. By June 1952, the film had grossed {{USD|700,000|long=no}} overseas.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZoAzAQAAIAAJ |title=日本産業図說 |trans-title=Japanese Industrial Illustrated Guide |language=ja |publisher={{Ill|Iwasaki Publishing|ja|岩崎書店}} |page=438 |date=1956 <!--|quote=「羅生門」(大映・黒沢明監督)は,その後各国に輸出公開され, 1952 年 6 月までに 70 万ドルの外貨を得ている。-->}}</ref> Later that same year, ''Scene'' reported that the film had earned {{USD|800,000|long=no}} ({{JPY|300 million}}) overseas, which was {{USD|200,000|long=no}} more than what all of the previous Japanese movies released overseas had collectively grossed outside of Japan within the past four years.<ref>{{cite magazine|title=Volume 4 |magazine=Scene: The International East-West Magazine|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RGcSAAAAIAAJ|via=] |access-date=August 5, 2024 |date=1952 |language=ja <!--|quote=「羅生門」の海外進出で、既に弗を稼ぐこと八十万弗、(三億円)に達して、過去四年間の輸出フイルム總敷よりも二十万弗近くも上-->}}</ref> In 1954, '']'' stated that it grossed {{USD|500,000|long=no}} in 1951, and reached roughly {{USD|800,000|long=no}} shortly thereafter.<ref>{{cite book|title=1954 New Year Special |trans-title=1954年新年特別号 |language=ja |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZEZjIeKhaIEC |date=1954 |page=78 |number=80 |volume=895 |via=] <!--|quote=二十六年の「羅生門」の出たときが五十万ドル昨年が八十万下と飛躍している。-->}}</ref><!--See also: https://books.google.co.nz/books?id=swdaAAAAYAAJ&q=rashomon+box+office&dq=rashomon+box+office&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjirM_qjd-HAxUcja8BHa4gIMU4HhDoAXoECAoQAg--> According to the ], ''Rashomon'' exceeded {{USD|300,000|long=no}} in the United States alone.<ref>{{cite magazine|last=National Board of Review|author-link=National Board of Review|title=The Unexceptional Japanese Films|magazine=Films in Review|page=273|volume=6|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qEAUAAAAIAAJ|date=1955}}</ref> | |||

| In 2002, the film grossed $46,808 in the US,<ref>{{cite web |title=Rashomon |url=https://www.boxofficemojo.com/title/tt0042876/ |website=] |access-date=19 April 2022}}</ref> with an additional earned $96,568 during 2009 to 2010,<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.the-numbers.com/movie/Rashomon#tab=summary|title=Rashomon |work=The Numbers|access-date=August 2, 2020}}</ref> for a combined {{US$|{{#expr:46808+96568}}|long=no}} in the United States between 2002 and 2010. | |||

| ===Venice Film Festival screening=== | |||

| Japanese film companies had no interest in international festivals and were reluctant to submit the movie because paying for printing and creating subtitles was considered a waste of money. The film was subsequently screened at the 1951 ] at the behest of Italifilm president ], who had recommended it to the Italian film promotion agency Unitalia Film seeking a Japanese film to screen at the festival. In 1953, Stramigioli explained her reasoning behind submitting the film: | |||

| {{blockquote|text= | |||

| <!--{{lang|ja|『羅生門』に私は非常な驚異を感じました。賞を得られるかどうかはともかくとして、これは相当の話題を呼ぶということがまず第一条件でしょう。その意味で『羅生門』は非常に特色を持つ映画で、しかも日本的であったから、全く適切だと思いました。テーマの扱い方、描き方、その映画に流れている精神と人間性ということも充分優れていると思いました。}}--> | |||

| I was shocked by ''Rashomon''. Regardless of whether it would win an award, the first condition is that it would generate a great deal of buzz. In that sense, ''Rashomon'' is a very distinctive film, and because it is so Japanese, I thought it was entirely appropriate. I also thought that the way it handled the theme, the way it was portrayed, and the spirit and humanity that flowed through the film were all excellent.<ref>{{cite magazine|title=ストラミジョリさんは語る|trans-title=Stramigioli Speaks|date=July 1953|magazine=]|page=79}}</ref> | |||

| |multiline=yes | |||

| }} | |||

| However, Daiei and other Japanese corporations disagreed with the choice of Kurosawa's work because it was "not of the Japanese movie industry" and felt that a work of ] would have been more illustrative of excellence in Japanese cinema. Despite these reservations, the film was screened at the festival. | |||

| Before it was screened at the Venice festival, the film initially drew little attention and had low expectations at the festival, as ] was not yet taken seriously in the West at the time. But once it had been screened, ''Rashomon'' drew an overwhelmingly positive response from festival audiences, praising its originality and techniques while making many question the nature of ].<ref name="Emporia">{{cite news |date=20 September 1963 |title=A Religion of Film |url=https://www.newspapers.com/image/12877901/ |url-access=subscription |access-date=19 April 2022 |work=] |page=4 |via=] |quote=The historians of the new cinema, searching out its origins, go back to another festival, the one at Venice in 1951. That year the least promising item on the cinemenu was a Japanese picture called Rashomon. Japanese pictures, as all film experts knew, were just a bunch of chrysanthemums. So the judges sat down yawning. They got up dazed. Rashomon was a cinematic thunderbolt that violently ripped open the dark heart of man to prove that the truth was not in it. In technique the picture was traumatically original; in spirit it was big, strong, male. It was obviously the work of a genius, and that genius was Akira Kurosawa, the easliest herald of the new era in cinema.}}</ref> The film won both the Italian Critics Award and the ] award<!--Source: https://archive.org/details/focusonrashomon0000unse/page/57/mode/2up?q=film+critics-->—introducing Western audiences, including Western directors, more noticeably to both Kurosawa's films and techniques, such as shooting directly into the sun and using mirrors to reflect sunlight onto the actor's faces. | |||

| ===Home media=== | |||

| ] released ''Rashomon'' on ] in May 2008 and ] in February 2009.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.kadokawa-pictures.jp/official/rashomon/video.shtml |title=羅生門 - DVD & Blu-ray |trans-title=''Rashomon'' - DVD & Blu-ray |language=ja |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210614210444/https://www.kadokawa-pictures.jp/official/rashomon/video.shtml |archive-date=June 14, 2021 |work=] }}</ref> ] later issued a Blu-ray and DVD edition of the film based on the 2008 restoration, accompanied by a number of additional features.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Rashomon|url=https://www.criterion.com/films/307-rashomon|website=The Criterion Collection|language=en|access-date=2020-05-15}}</ref> | |||

| ==Reception== | |||

| ===Critical response=== | |||

| ====Japanese reviews==== | |||

| ''Rashomon'' was met with mixed reviews from Japanese critics upon its release.{{sfn|Galbraith|2002|p=132}}<ref>{{cite book|last=Tanaka|first=Jun'ichirō|author-link=:ja:田中純一郎|title=永田雅一|trans-title=Masaichi Nagata|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TLxIAAAAMAAJ|language=ja|page=125|publisher=Jiji Press|isbn=|via=]|date=1962<!--|quote= 「羅生門」は、たしかにお門ちがいの「商品」だったに相違ない。日本の映画批評家たちでさえ、評価はまちまちで、コンクールでは第五位にとどまり、映画館の支配人は、観客が戸迷って、入りが悪いとこぼした。-->}}</ref> When it received positive responses in the West, Japanese critics were baffled: some decided that it was only admired there because it was "exotic"; others thought that it succeeded because it was more "Western" than most Japanese films.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.tcm.com/thismonth/article.jsp?cid=136021&mainArticleId=160926 |title=Rashomon |publisher=Tcm.com |last=Tatara |first=Paul |date=1997-12-25 |access-date=2 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081225144943/http://www.tcm.com/thismonth/article.jsp?cid=136021&mainArticleId=160926 |archive-date=December 25, 2008}}</ref> | |||

| ] criticized "its insufficient plan for visualizing the style of the original stories". Tatsuhiko Shigeno of '']'' opposed Mifune's extensive dialogue as unfitting for the role of a bandit.<!--https://archive.org/details/focusonrashomon0000unse/page/92/mode/2up?q=critics--> ] later cited how he and his contemporaries were "impressed by the boldness and excellence of director Akira Kurosawa's experimental approach within this movie, but couldn't help but notice that there was some confusion in its expression" adding that "I found it difficult to resonate with the agnostic philosophy that the film contains wholeheartedly".<ref>{{cite book|last=Iwasaki|first=Akira|author-link=Akira Iwasaki|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ABfE3FFQzr4C|title=映画史|trans-title=Film History|language=ja|publisher=]|isbn=|year=1961|page=261<!--|quote=批評家も、知的な観客も、もちろん監督の黒沢明がこの映画のなかで試みた実験的な形式の大胆さと卓抜さには感心したが、その表現にすくなからぬ混乱があることに気づかずにはいなかったし、それ以上に、この映画の含んでいる不可知論的な哲学に心から共鳴できなかった。-->|via=]}}</ref> | |||

| In a collection of interpretations of ''Rashomon'', ] writes that "the confines of 'Japanese' thought could not contain the director, who thereby joined the world at large".<ref name="R80">(Richie, 80)</ref> Regarding the film's Japanese reception, Kurosawa remarked: | |||

| <blockquote>"Japanese are terribly critical of Japanese films, so it is not too surprising that a foreigner should have been responsible for my being sent to Venice. It was the same way with Japanese woodcuts; it was the foreigners who first appreciated them. We Japanese think too little of our own things. Actually, ''Rashomon'' wasn't all that good, I don't think. Yet when people have said to me that its reception was just a stroke of luck, a fluke, I have answered by saying that they only say these things because the film is, after all, Japanese, and then I wonder: Why do we all think so little of our own things? Why don’t we stand up for our films? What are we so afraid of?"{{sfn|Richie|1965|p=80}}</blockquote> | |||

| ====International reviews==== | |||

| ''Rashomon'' received mostly acclaim from Western critics.<ref>{{cite book|title=Akira Kurosawa: a guide to references and resources |url=https://archive.org/details/akirakurosawagui0000eren/ |date=1972 |pages=71–73 |isbn=978-0-8161-7994-7 |last1=Erens |first1=Patricia |publisher=G. K. Hall }}</ref><ref>{{cite magazine|url=https://archive.org/details/americancinemato35unse |title=May, 1954 |year=1954 |volume=35 |page=248 |magazine=] }}</ref> | |||

| ] gave the film a positive review in '']'', calling it "an exciting evening, because the direction, the photography and the performances will jar open your eyes." He praised Akutagawa's original plot, Kurosawa's impactful direction and screenplay, Mifune's "magnificent" villainous performance, and Miyagawa's "spellbinding" cinematography that achieves "visual dimensions that I've never seen in Hollywood photography" such as being "shot through a relentless rainstorm that heightens the mood of the somber drama."<ref>{{cite news |last1=Sullivan |first1=Ed |author1-link=Ed Sullivan |title=Behind the Scenes |url=https://www.newspapers.com/image/683939225/ |access-date=19 April 2022 |work=] |via=] |date=22 January 1952 |page=12 |url-access=subscription}}</ref> Meanwhile, '']'' was critical of the film, finding it "draggy" and noted that its score "borrows freely" from Maurice Ravel's ''Boléro''.<ref name="Time">{{cite magazine|url=https://time.com/vault/issue/1952-01-07/|title=''Rashomon''|magazine=]|pages=82, 84–85|number=1|date=January 7, 1952}}</ref><!-- | |||

| See also: https://www.newspapers.com/image/562757438/?match=1&terms=rashomon%201950%20rumors--> | |||

| === ''Boléro'' controversy === | |||

| The usage of a musical composition similar to Ravel's ''Boléro'' provoked wide controversy, especially in Western countries.<ref name=":3">{{Cite book |last=Nishimura |first=Yūichirō |author-link=:ja:西村雄一郎 |title=黒澤明と早坂文雄 風のように侍は |date=October 2005 |publisher=] |isbn=9784480873491 |page=659 |language=ja |trans-title=Akira Kurosawa and Fumio Hayasaka: Samurai Like the Wind}}</ref> Some accused Hayasaka of ],<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YggKAQAAMAAJ |title=音樂芸術 |date=1995 |publisher=Music Friends Company |volume=53 |pages=49 |language=ja |trans-title=Musical Arts}}</ref> including ''Boléro''<nowiki/>'s publisher, who sent him a letter of protest after the film's French release.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

| In late 1950, the film was vetoed from {{Ill|Motion Picture Producers Association of Japan|ja|日本映画製作者連盟}}'s selection list for the ] over concerns about facing copyright issues for the composition. | |||

| === Masaichi Nagata's response === | |||

| Daiei's president, ], was initially critical of the film.{{sfn|Richie|1965|p=70}}<ref name=":1">{{Cite book |title=People Who Talk About Akira Kurosawa |date=September 2004 |publisher=] |isbn=9784257037033 |pages=30 |language=ja |trans-title=黒澤明を語る人々}}</ref><ref name=":2">{{Cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/akirakurosawaint0000kuro |title=Akira Kurosawa: Interviews |date=2008 |publisher=] |isbn=9781578069972 |editor-last=Cardullo |editor-first=Bert |pages=176–177 |url-access=limited}}</ref> Assistant director ] said that Nagata broke the abrupt few minutes of silence following its preview screening at the company's headquarters in ] by saying "I don't really get it, but it's a noble photograph".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Tanaka |first=Tokuzō |author-link=Tokuzō Tanaka |title=映画が幸福だった頃 |date=May 1994 |publisher=JDC |isbn=9784890081516 |page=37 |language=ja |trans-title=When Moivies Were Happy}}</ref> According to Kurosawa, Nagata had called ''Rashomon'' "incomprehensible" and loathed it so much that he ended up demoting its producer.<ref name=":2" /> | |||

| Nagata later embraced ''Rashomon'' upon it receiving numerous awards and international success.{{sfn|Richie|1965|p=70}} He kept the original Golden Lion that the film received in his office, and had replicas handed to Kurosawa and others who worked on the film. His constant reference to its accomplishments as if he was responsible for the film himself was stated by many.<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":2" /> In 1992, Kurosawa remarked that Nagata had cited ''Rashomon''<nowiki/>'s cinematographic feats in an interview included for the film's first television broadcast without mentioning the names of its director or cinematographer. He reflected being disgusted by the company's president taking credit for the film's achievements: "Watching that television interview, I had the feeling that I was back in the world of ''Rashomon'' all over again. It was as if the pathetic self-delusions of the ego, those failings I had attempted to portray in the film, were being exhibited in real life. People do indeed have immense difficulty talking about themselves as they really are. I was reminded once again that the human animal suffers from the trait of instinctive self-aggrandizement."<ref name=":2" /> Some modern sources have erroneously credited Nagata as the film's producer. | |||

| ===Accolades=== | |||

| {| class="wikitable sortable plainrowheaders" | |||

| ! scope="col" |Award | |||

| ! scope="col" |Date of ceremony | |||

| ! scope="col" |Category | |||

| ! scope="col" |Recipient(s) | |||

| ! scope="col" |Result | |||

| ! class="unsortable" scope="col" |{{Tooltip|Ref.|Reference(s)}} | |||

| |- | |||

| ! rowspan="2" scope="row" style="text-align:center;"| ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ''Rashomon'' (]) | |||

| | {{won}} | |||

| |<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.oscars.org/oscars/ceremonies/1952|title=The 24th Academy Awards (1952) |work=] |date=October 5, 2014 |access-date=August 8, 2024 }}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] (art direction)<br>] (]){{efn|The Academy merely referred to Matsuyama by his last name and erroneously spelled Matsumoto's last name as "Motsumoto".<ref name="25th">{{cite web|url=https://www.oscars.org/oscars/ceremonies/1953|title=The 25th Academy Awards (1953) |work=] |date=October 4, 2014 |access-date=August 8, 2024 }}</ref>}} | |||

| | {{nominated}} | |||

| | <ref name="25th"/> | |||

| |- | |||

| ! rowspan="2" scope="row" style="text-align:center;"| ] | |||

| | rowspan="2" | March 22, 1951 | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ''Rashomon'' | |||

| | {{draw|4th Place}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ]<br>] | |||

| | {{won}} | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" style="text-align:center;"| ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ''Rashomon'' | |||

| | rowspan="2" {{nominated}} | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" style="text-align:center;"| ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | Akira Kurosawa | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" style="text-align:center;"| Foreign Language Press Film Critics Circle (via ]) | |||

| | {{circa}} April 1952 | |||

| | Best Foreign Film | |||

| | ''Rashomon''<br>(Robert Mochrie){{efn|Mochrie was the vice president of the film's American distributor, ], at the time and accepted the award on behalf of the Japanese crew.}} | |||

| | {{won}} | |||

| | <ref>{{cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/exhibitorfebapr147jaye/page/n736/mode/2up?q=rashomon |title=The Exhibitor (Feb-Apr 1952) General Edition |date=April 16, 1952 |page=n736 |access-date=August 11, 2024 }}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" style="text-align:center;"| '']'' | |||

| | rowspan="2" | 1950 | |||

| | Top 10 Japanese Movies | |||

| | ''Rashomon'' | |||

| | {{draw|5th Place}} | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" style="text-align:center;"| ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ]{{efn|Also received the award for her performance in ''{{Ill|Clothes of Deception|ja|偽れる盛装}}''.}} | |||

| | rowspan="3" {{won}} | |||

| | <ref>{{cite web |url=https://mainichi.jp/mfa/history/005.html |title=毎日映画コンクール 第5回(1950年)|trans-title=5th Mainichi Film Awards (1950) |language=ja |work=] |access-date=August 11, 2024}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| ! rowspan="2" scope="row" style="text-align:center;"| ] | |||

| | rowspan="2" | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ''Rashomon'' | |||

| | rowspan="3" | <ref>{{cite book |last=O'Neil |first=Thomas |url=https://archive.org/details/movieawardsultim0000onei/ |url-access=limited |title=Movie Awards: The Ultimate, Unofficial Guide to the Oscars, Golden Globes, Critics, Guild & Indie Honors |year=2003 |page=144 |publisher=] |isbn=9780399529221}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | Akira Kurosawa | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" style="text-align:center;"| ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | rowspan="3" | ''Rashomon'' | |||

| | {{runner-up}} | |||

| |- | |||

| ! rowspan="2" scope="row" style="text-align:center;"| ] | |||

| | rowspan="2" | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | rowspan="2" {{won}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |Italian Critics’ Prize | |||

| |- | |||

| |} | |||

| ==Legacy== | |||

| {{Expand section|date=August 2024}} | |||

| ===Associated films=== | |||

| The international success of ''Rashomon'' led Daiei to produce several subsequent ''jidaigeki'' films featuring Kyō as the lead.{{sfn|Richie|1965|p=80}} Among these were ]'s '']'' (1951), ]'s '']'' (1952) and '']'' (1953), ]'s '']'' (1953), and Keigo Kimura's '']'' (1954), all of which received screenings overseas.<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0utIAAAAMAAJ |title=昭和映画世相史 |year=1982 |page=165 |language=ja |trans-title=Showa Film Social History |quote=<!--... 羅生門」〈昭和二十五年封切〉のあと、この年は「美女と盗賊」=木村恵吾監督<九月二十三日封切〉、「大仏開眼」=衣笠貞之助監督<十一月十三日封切〉と、世界的?大作ばかり主演している京マチ子を、大映は、ガラリと方向転換させて軽喜劇もの「彼女の--> |author1=児玉数夫 }}</ref> In 1952, Daiei produced a Western-targeted ], titled ''{{Ill|Beauty and the Thief|ja|美女と盗賊}},''<ref>{{Cite magazine |date=October 4, 1952 |title=''Beauty and the Thief'' |url=https://archive.org/details/sim_motion-picture-herald-motion-picture-news_1952-10-04_189_1/page/n68/ |access-date=August 19, 2024 |magazine=] |page=39 |volume=189}}</ref> with the intent of obtaining a second Golden Lion.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.kadokawa-pictures.jp/official/41382/|title=美女と盗賊|trans-title=''Beauty and the Thief'' |language=ja|publisher=]|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210623080636/https://www.kadokawa-pictures.jp/official/41382/|url-status=dead |archive-date=June 23, 2021 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://db.eiren.org/contents/04110035001.html |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230127102814/http://db.eiren.org/contents/04110035001.html |archive-date=January 27, 2023 |publisher=Motion Picture Producers Association of Japan |title=美女と盗賊|trans-title=''Beauty and the Thief'' |language=ja }}</ref>{{efn|Daiei referred to the Golden Lion as the "Grand Prix", which is what the award was known as in Japan at the time.}} Based on another story by Akutagawa, composed by Hayasaka, and starring Kyō, Mori, Shimura, Katō, and Honma, the film has been described as an inferior imitator of ''Rashomon'' and has since faded into obscurity.<ref>{{Cite magazine |date=1958 |title=Issues 123-128 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9g4G0JXQz8YC |access-date=August 19, 2024 |magazine={{Ill|Eiga Geijutsu|ja|映画芸術}} |page=27 |language=ja |via=] |quote=<!--羅生門」とその亜流「美女と盗賊」をくらべてみるとよい。どちらも京マチ子がでている。「美「女」は通りいつぺんで今では忘られた映画だし、この作品を売るめたい。「夫婦善哉」「猫と庄造福子。猫をめぐって二人の女がはあても、京マチ子のストリップま-->}}</ref>{{sfn|Richie|1965|p=80}}<!-- See also: https://archive.org/details/imagesducinemaja0000tess/page/186/mode/ --> Mifune was also initially going to appear in ''Beauty and the Thief'' as suggested by a photograph of him taken by ] during production in 1951 when the film was allegedly titled "''Hokkaido''".<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/filmstarsphotogr0000unse/ |title=Film Stars: Photographs of Magnum Photos |date=1998 |isbn=978-2879391885 |pages=64 |language=fr |last1=Arnold |first1=Eve |last2=Photos |first2=Magnum |publisher=Terrail Photo }}</ref> | |||

| ===Cultural impact=== | |||

| ''Rashomon'' has been cited as "one of the most influential films of the 20th century".<ref>{{cite book |title=The Movie Book: Big Ideas Simply Explained |publisher=] |page=113}}</ref> In the early 1960s, film historians credited ''Rashomon'' as the start of the international ] movement, which gained popularity during the late 1950s to early 1960s.<ref name="Emporia" /> It has since been cited as an inspiration for numerous films from around the world, including '']'' (1954),<ref>{{Cite news |last=Venkataramanan |first=Geetha |date=April 7, 2016 |title=''Andha Naal'': Remembering veena S. Balachander |url=https://www.thehindu.com/features/cinema/andha-naal-remembering-veena-s-balachander/article8446799.ece |url-access=subscription |url-status=live |archive-url=https://archive.today/20170328074306/http://www.thehindu.com/features/cinema/andha-naal-remembering-veena-s-balachander/article8446799.ece |archive-date=March 28, 2017 |access-date=August 12, 2024 |work=] |language=en-IN}}</ref> '']'' (1957),<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780600573975/ |title=The Chronicle of the Movies: A Year-by-year History of Talking Pictures |year=1991 |pages=270 |publisher=W.H.Smith |isbn=978-0-600-57397-5 |url-access=limited}}</ref> '']'' (1961),<ref>{{Cite book |title=ベスト・オブ・キネマ旬報(上) 1950-1966 |year=1994 |isbn=9784873761008 |volume=1 |pages=1530 |publisher=キネマ旬報社 |language=ja |trans-title=Best of Kinema Junpo: 1950―1966 |quote=<!--「去年マリエンバートで」が黒沢の「羅生門」をモデルにして書かれた、とはっきり言ったことであった。実際、三人の登場人物の各々の視点がそのままカメラの視点として映画を語ってゆく「マリエンバート」の構成は「羅生門」そのままであると言える-->}}</ref> '']'' (1982),<ref>{{Cite web |date=September 24, 2023 |title=Influential Malayalam filmmaker K G George, who expertly bridged the gap between art house and mainstream cinema, dies at 77 |url=https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/thiruvananthapuram/malayalam-filmmaker-k-g-george-bridged-the-gap-between-art-house-and-mainstream-cinema-dies-at-77-8954238/ |access-date=August 12, 2024 |website=] |language=en}}</ref> ]'s '']'' (1992)<ref>{{Cite web |last=Sherlock |first=Ben |date=August 13, 2021 |title=10 Classic Movies Referenced In ''Reservoir Dogs'' |url=https://screenrant.com/ten-classic-movies-referenced-reservoir-dogs/ |access-date=August 12, 2024 |website=] |language=en}}</ref> and '']'' (1994),<ref name="BBC" /> '']'' (1995),<ref name="BBC" /> '']'' (1996),<ref name=":4">{{Cite web |last=Richlin |first=Harrison |date=2024-05-05 |title=Ryan Reynolds Says Kevin Feige Rejected His 'Rashomon'-Inspired Pitch for 'Deadpool & Wolverine' |url=https://www.indiewire.com/news/general-news/ryan-reynolds-pitched-deadpool-and-wolverine-rashomon-1235000140/ |access-date=2024-08-23 |website=IndieWire |language=en-US}}</ref> ] (2001),<ref name="BBC" /> ] (2002),<ref name="BBC" /> and '']'' (2023).<ref>{{Cite web |title=''Fast X'' director breaks down the first trailer |url=https://ew.com/movies/fast-x-director-louis-leterrier-breaks-down-first-trailer/ |access-date=August 23, 2024 |website=EW.com |language=en}}</ref><!--See also: <ref>{{cite news|url=http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/chennai/How-Kurosawa-inspired-Tamil-films/articleshow/22355755.cms|title=How Kurosawa inspired Tamil films|work=The Times of India|date=September 6, 2013 |access-date=13 March 2016}}</ref>--> | |||

| The television shows '']'' (1971–1979),<ref name=":4" /> '']'' (1993–2004), and ] (2024)<ref>{{Cite web |last=Davids |first=Brian |date=March 19, 2024 |title=''Star Wars: The Acolyte'' Creator Leslye Headland Talks the Unique Perspective of Her Upcoming Series |url=https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/tv/tv-features/star-wars-the-acolyte-trailer-timeline-1235855636/ |access-date=August 23, 2024 |website=] |language=en-US}}</ref> were also inspired by the film. Some have compared ] (2023) to the film,<ref name=":4" /> however, director ] claimed its similarities are merely coincidental.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Raup |first=Jordan |date=2023-11-21 |title=Hirokazu Kore-eda on Why Monster is Not Like Rashomon, Queer Storytelling, and Ryuichi Sakamoto |url=https://thefilmstage.com/hirokazu-kore-eda-on-why-monster-is-not-like-rashomon-queer-storytelling-and-ryuichi-sakamoto/ |access-date=August 23, 2024 |language=en-US}}</ref> ]' initial proposal for '']'' (2024) was for it to have a plot similar to ''Rashomon''.<ref name=":4" /> | |||

| In a 1998 issue of '']'', ] wrote: <blockquote>''Rashomon'' is probably familiar even to those who haven't seen it, since in movie jargon, the film's title has become synonymous with its chief narrative conceit: a story told multiple times from various points of view. There's much more than that to the film, of course. For example, the way Kurosawa uses his camera...takes this fascinating meditation on human nature closer to the style of silent film than almost anything made after the introduction of sound.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Johnston|first=Andrew|date=February 26, 1998|title=Rashomon|journal=Time Out New York}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| ==== Remakes and adaptations ==== | |||

| {{See also|Remakes of films by Akira Kurosawa}} | |||

| It spawned numerous ] and adaptations across film, television and theatre.<ref name="Taste">{{cite news |last1=Magnusson |first1=Thor |title=10 Great Movies That Used The Rashomon Effect |url=http://www.tasteofcinema.com/2018/10-great-movies-that-used-the-rashomon-effect/ |work=Taste of Cinema |date=25 April 2018}}</ref><ref name="GeekTV">{{cite web |last1=Harrisson |first1=Juliette |title=5 great Rashomon TV episodes |url=https://www.denofgeek.com/tv/5-great-rashomon-tv-episodes/ |website=Den Of Geek |date=3 October 2014}}</ref> Examples include: | |||

| * ] as a play, various versions of which have been performed since the 1950s, including on ] in 1959 as written by Michael and Fay Kanin.<ref name="IBDB">{{cite web |title=Rashomon |url=https://www.ibdb.com/broadway-production/rashomon-2068 |website=Internet Broadway Database |publisher=The Broadway League |access-date=26 September 2022}}</ref><ref name="Journal">{{cite news |title='Rashomon' Classic to Be on 'Cinema 9' |url=https://www.newspapers.com/image/342570368/ |access-date=19 April 2022 |work=] |via=] |date=30 May 1965 |page=15 |url-access=subscription}}</ref> | |||

| * On '']'', in 1960, season 2, episode 12, "Rashomon". Based on Kurosawa's film. Directed by ]. | |||

| * On '']'', in 1962, season 2, episode 9, "The Night the Roof Fell In". Rob and Laura's perspectives of their day is countered by a goldfish.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Boyd |first1=Greg |title=Review: The Dick Van Dyke Show, "The Night the Roof Fell In" |url=https://thiswastv.com/2013/07/23/review-the-dick-van-dyke-show-the-night-the-roof-fell-in/ |website=thiswastv.com |date=23 July 2013}}</ref> | |||

| * '']'', a 1964 American ] directed by Martin Ritt. Screenplay adapted by ] from the 1959 Broadway version he co-wrote with his wife, Fay Kanin (above).<ref name="IBDB"/><ref>{{cite web |last1=Maunula |first1=Vili |title=Film Club: The Outrage (Ritt, 1964) |url=https://akirakurosawa.info/2012/02/01/film-club-the-outrage-ritt-1964/ |website=akirakurosawa.info |date=1 February 2012}}</ref> | |||

| * On '']'', in 1972, season 2, episode 21, "A Night To Dismember". Oscar, Blanche and Felix all remember the New Year's Eve when the Madisons split up differently. | |||

| * On '']'', in 1973, season 3, episode 21, "Everybody Tells the Truth". Mike, Archie, and Edith recount competing tales of the evening's interactions with a refrigerator repairman. | |||

| * "Rashomama", a 1983 episode of ] | |||

| * On '']'', in 1987, season 1, episode 4, "Couples". Each of the 4 main characters remember differently their evening at a restaurant and a marital fight afterwards. | |||

| * '']'', where a 1990 episode called "]" was produced and aired with a similar plot line to ''Rashomon'', this time told from the view of Commander Riker, the assistant of a murdered respected scientist and the scientist's widow.<ref>{{cite web |last1=DeCandido |first1=Keith R.A. |title=Star Trek: The Next Generation Rewatch: "A Matter of Perspective" |url=https://www.tor.com/2011/12/30/star-trek-the-next-generation-a-matter-of-perspective/ |website=Tor.com |date=30 December 2011}}</ref><ref name="GeekTV"/> | |||

| * '']'', a 1996 ], in which events surrounding the rescue of a downed ] helicopter in the ] are recounted in flashbacks by three different crew members.<ref name="Taste"/> | |||

| * On '']'', in 1997, season 5, episode 9, "Perspectives on Christmas". The family each recall their day from different perspectives.<ref name="GeekTV"/> | |||

| * '']'', the 12th episode of the fifth season of '']'' features differing accounts from Mulder and Scully regarding a Vampire encounter.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.avclub.com/the-x-files-bad-blood-millennium-luminary-1798168550 |title=The X-Files: "Bad Blood" / Millennium : "Luminary" | |||

| |last=Handlen |first=Zack |date=June 11, 2011 |website=The A.V Club |access-date= November 5, 2024|quote= This is a Rashomon episode, in which much of the running time is given over to either Mulder or Scully explaining their version of events.}}</ref> | |||

| * '']'': in the tenth episode of the third season, "A Fire Fighting We Will Go". The gang each recalls the burning down of a firehouse from their perspective, each portraying themselves as the hero. | |||

| * '']'s'' second season's 17th episode, "The Ugly Truth", which aired in 2000, follows this format, challenging the crew of ''Moya'' as liars, as the interrogators are a species with ] who can't comprehend subjective viewpoints.<ref name="GeekTV"/> | |||

| * "Suspect", episode 13 of season 2 of '']'' from 2003, depicts the mystery of who attempted the murder of Lionel Luthor with contradictory flashbacks from multiple perspectives. | |||

| *'']'', a 2004 ] film written, directed and produced by ],depicts an incident in view of two prisoners, Virumaandi thevar and Kothala thevar. | |||

| * On '']'', in the 2006, Season 6, Episode 21 "Rashomama". Nick's car containing all the evidence for a murder is stolen and the team attempts to continue the investigation based on their conflicting memories of the crime scene.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Huntley |first1=Kristine |title=CSI -- 'Rashomama' |url=https://www.csifiles.com/reviews/csi/rashomama.shtml |website=csifiles.com |date=1 May 2006}}</ref> | |||

| * '']'', a 2008 film with multiple viewpoints focusing on an assassination attempt on the President of the United States | |||

| * ''The Rashomon Job'', an episode of the series '']'' (2008–2012) telling the story of a heist from five points of view (S03E11) | |||

| * '']'', a 2011 ] film by M.L. Pundhevanop Devakula, adapting Kurosawa's screenplay to ancient ].<ref>{{cite web |last1=Maunula |first1=Vili |title=Review: At the Gate of the Ghost (2011) |url=https://akirakurosawa.info/2013/05/12/review-at-the-gate-of-the-ghost-2011/ |website=akirakurosawa.info |date=12 May 2013}}</ref> | |||

| * '']'', a 2013 film partially inspired by some plot elements. | |||

| * '']'', a 2014 series portraying an extramarital relationship where the leads recount different versions of their liaison. | |||

| * '']'', a 2014 ] film directed ], where a journalist narrates the story of a murder in 7 different viewpoints by giving special reference to local ] and their culture. | |||

| * '']'', a 2015 ] film narrates the story of a double murder through multiple contradictory viewpoints. | |||

| * '']'', a 2017 ] film by ], also based on ]'s '']''. | |||

| * '']'', a 2017 film that tells the story of the ] in the style of ''Rashomon''. | |||

| * '']'', ]'s 2021 epic historical drama of a rape and duel told through multiple points of view.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Birzer |first1=Nathaniel |title=Ridley Scott's The Last Duel and Kurosawa's Rashomon |url=https://oll.libertyfund.org/reading_room/Birzer_Rashoman_Last_Duel |website=Online Library of Liberty |publisher=Liberty Fund |date=19 April 2022}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |last1=Zachary |first1=Brandon |title=The Last Duel Is Ridley Scott's Take On a Classic Japanese Film |url=https://www.cbr.com/the-last-duel-ridley-scott-rashomon/ |website=cbr.com |date=16 October 2021}}</ref> | |||

| ===Retrospective reassessment=== | |||

| In the years following its release, several publications have named ''Rashomon'' one of the ], and it is also cited in the book '']''.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Schneider |first=Steven Jay |title=] |publisher=] |year=2008 |isbn=978-0-7641-6151-3 |edition=5th Anniversary/3rd |pages=250}}</ref> {{Rotten Tomatoes prose|score=98|count=63|average=9.2|consensus=One of legendary director Akira Kurosawa's most acclaimed films, ''Rashomon'' features an innovative narrative structure, brilliant acting, and a thoughtful exploration of reality versus perception.|ref=yes |access-date=January 6, 2019 }} {{Metacritic film prose |score=98 |count=18 |access-date=August 6, 2024 |ref=yes}} | |||

| Film critic ] gave the film four stars out of four and included it in his '']'' list.<ref>{{cite web|title=Rashomon|url=https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-rashomon-1950|website=Roger Ebert.com}}</ref> | |||

| ====Top lists==== | |||

| The film appeared on many critics' top lists of the best films. | |||

| * 10th – Directors' Top Ten Poll in 1992, '']''<ref>{{cite web |title=Sight & Sound top 10 poll 1992 |url=http://old.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/polls/topten/history/1992.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120618100140/http://old.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/polls/topten/history/1992.html |archive-date=18 June 2012 |access-date=17 February 2015 |website=BFI}}</ref> | |||

| * 10th - 100 Greatest Films list in 2000 '']''<ref>{{cite news |last=Hoberman |first=J. |date=January 4, 2000 |title=100 Best Films of the 20th Century |url=http://www.filmsite.org/villvoice.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140331174817/http://www.filmsite.org/villvoice.html |archive-date=March 31, 2014 |access-date=December 14, 2014 |publisher=Village Voice Media, Inc. |location=New York}}</ref> | |||

| * 76th - "Top 100 Essential Films of All Time" by the ] in 2002.<ref name="Carr81">{{Cite book |last=Carr |first=Jay |url=https://archive.org/details/alistnationalsoc00jayc |title=The A List: The National Society of Film Critics' 100 Essential Films |publisher=Da Capo Press |year=2002 |isbn=978-0-306-81096-1 |page= |access-date=27 July 2012 |url-access=registration}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=100 Essential Films by The National Society of Film Critics |url=https://www.filmsite.org/alist.html |website=filmsite.org}}</ref> | |||

| * 9th – Directors' Top Ten Poll in 2002, ''Sight & Sound''<ref>{{cite web |title=Sight & Sound Top Ten Poll 2002 The Rest of Director's List |url=http://old.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/polls/topten/poll/directors-long.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170201155933/http://old.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/polls/topten/poll/directors-long.html |archive-date=February 1, 2017 |access-date=May 13, 2021 |website=old.bfi.org.uk}}</ref> | |||

| * 13th - Critics' poll in 2002, ''Sight & Sound''<ref>{{cite web |title=Sight & Sound 2002 Critics' Greatest Films poll |url=https://www.listal.com/list/sight-sound-2002-critics |website=listal.com}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=''Sight & Sound'' Greatest Films of All Time 2002 |url=http://old.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/polls/topten/poll/critics-long.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160813112813/http://old.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/polls/topten/poll/critics-long.html |archive-date=August 13, 2016 |access-date=May 2, 2021 |website=bfi.org}}</ref> | |||

| * 290th – The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time in 2008, '']''<ref>{{cite web |date=2006-12-05 |title=Empire Features |url=http://www.empireonline.com/500 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111020200830/http://www.empireonline.com/500/ |archive-date=October 20, 2011 |access-date=May 2, 2022 |publisher=Empireonline.com}}</ref> | |||

| * ''50 Klassiker, Film'' by Nicolaus Schröder in 2002<ref>Schröder, Nicolaus. (2002). ''50 Klassiker, Film''. Gerstenberg. {{ISBN|978-3-8067-2509-4}}.</ref> | |||

| * '']'' by Steven Jay Schneider in 2003<ref>{{cite web |date=2002-07-22 |title=1001 Series |url=http://1001beforeyoudie.com |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140110124836/http://1001beforeyoudie.com/ |archive-date=2014-01-10 |access-date=2011-10-21 |publisher=1001beforeyoudie.com}}</ref> | |||

| * 7th – '']'''s ''The Greatest Japanese Films of All Time'' in 2009.<ref>{{cite web |title=Greatest Japanese films by magazine Kinema Junpo (2009 version) |url=http://mubi.com/topics/greatest-japanese-films-by-magazine-kinema-junpo-2009-version |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://archive.today/20120711021342/http://mubi.com/topics/greatest-japanese-films-by-magazine-kinema-junpo-2009-version |archive-date=July 11, 2012 |access-date=2011-12-26}}</ref> | |||

| * 22nd – '']'''s "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema" in 2010.<ref>{{cite web |title=The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema – 22. Rashomon |url=http://www.empireonline.com/features/100-greatest-world-cinema-films/default.asp?film=22 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111124033346/https://www.empireonline.com/features/100-greatest-world-cinema-films/default.asp?film=22 |archive-date=November 24, 2011 |access-date=2 May 2022 |work=Empire}}</ref> | |||

| * 26th - Critics top ten poll, ], '']'' (2012) | |||

| * 18th - Director's top ten poll, ], '']'' (2012) | |||

| * ] included it among his top ten films.<ref>{{cite web |date=August 24, 2012 |title=Read ''Sight & Sound'' Top 10 Lists from Quentin Tarantino, Edgar Wright, Martin Scorsese, Guillermo del Toro, Woody Allen and More |url=http://collider.com/sight-sound-directors-list-quentin-tarantino/191040/?_r=true |work=Collider}}</ref> | |||

| *4th - ]'s list of "100 greatest foreign language films" in 2018.<ref>{{cite web |title=100 greatest foreign language films |url=https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20181029-the-100-greatest-foreign-language-films |access-date=27 October 2020 |website=bbc.com published 27 October 2018}}</ref> | |||

| === Preservation === | |||

| In 2008, the film was restored by the ], the National Film Center of the ], and Kadokawa Pictures, Inc., with funding provided by the Kadokawa Culture Promotion Foundation and ].<ref>{{Cite web|title=Rashomon Blu-ray - Toshirô Mifune|url=http://www.dvdbeaver.com/film5/blu-ray_reviews_68/rashomon_blu-ray.htm|website=www.dvdbeaver.com|access-date=2020-05-15}}</ref> | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| ===Bibliography=== | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Davis|first1=Blair|first2=Robert|last2=Anderson|first3=Jan|last3=Walls|title=Rashomon Effects: Kurosawa, Rashomon and Their Legacies|date=November 2015|publisher=]|isbn=978-1138827097}} | |||

| * {{cite news|url=https://www.newspapers.com/image/370538385/|title=January 20, 1952|newspaper=]|date=January 20, 1952|page=169<!--|quote=''Rasho-Mon'' which means "In the Forest"-->|via=]|url-access=subscription |ref={{sfnref|''Chicago Tribune''|1952}}}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last1=Dixon|first1=Wheeler Winston|author-link1=Wheeler Winston Dixon|last2=Foster|first2=Gwendolyn Audrey|author-link2=Gwendolyn Audrey Foster|title=A Short History of Film|publisher=Rutgers University Press|year=2008|isbn=9780813544755}} | |||

| * {{cite book|first=Catherine|last=Russell|title=Classical Japanese Cinema Revisited|publisher=]|year=2011|isbn=9781441107770}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Richie|first=Donald|author-link=Donald Richie|title=]|year=1965|publisher=University of California Press |isbn=9780520017818}} | |||

| * {{cite news|last=Falk |first=Ray |url=https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1951/10/21/94087851.pdf |title=Japan's ''Rashomon'' Rings the Bell |date=October 21, 1951 |work=] |page=4X |url-access=subscription <!--|quote='' Times]]'' goes on to state that Japanese production costs are one-fourth and salaries one-tenth of those for the American movie industry and thus with an annual output of 215 films Japan may have a potentially profitable export item. Jingo Minoura was able to keep the cost of production down to $140,000.--> |access-date=August 7, 2024}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=National Board of Review |author-link=National Board of Review |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=P0EUAAAAIAAJ|title=Films in Review|volume=4 |year=1953 |quote=The outlay for Kurosawa's latest film, ''Living'', was $85,000, which is more than twice the cost of ''Rashomon''. A top director like Kurosawa receives $35,00 a picture, but for such a price he must furnish his own scenario. |via=]|access-date=August 7, 2024}} | |||

| * {{cite magazine|last=Jitsugyo no Nihon Sha|author-link=Jitsugyo no Nihon Sha|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7lDOAAAAMAAJ|title=Issues 11-17|volume=55|magazine=Business Japan|via=]|access-date=July 26, 2024|date=1952 <!--|quote=「羅生門」は、平以上の二千數百萬の製作費と云われています。何の外に、本社關係の諸費用や積立金、株主などの費用、配給經費、撮影所などの一般經費などを加えますと、一本約三千五百萬圓かゝると、産業合理化審議會映画が発表しておます。 「羅生門」の外貨収入が七十萬ドルと聞きますが-->}} | |||

| * {{cite book |editor-last=Brandon |editor-first=James R. |editor-link=James Rodger Brandon |title=The Performing arts in Asia |publisher=] |url=https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000003091 |year=1971 |access-date=August 5, 2024}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Robertson|first=Patrick|title=The Guinness Book of Movie Facts and Feats|year=1991|url=https://archive.org/details/guinnessbookofmo0000robe|publisher=Abbeville Press|isbn=978-1-558-59236-0}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Galbraith |first=Stuart IV |author-link=Stuart Galbraith IV |year=2002 |title=The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune |url-access=registration |url=https://archive.org/details/emperorwolf00galb |publisher=Faber and Faber |isbn=978-0-571-19982-2}} | |||

| * Conrad, David A. (2022) ''Akira Kurosawa and Modern Japan''. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. | |||

| * Davidson, James F. (1987) "Memory of Defeat in Japan: A Reappraisal of Rashomon" in ] (ed.). New Brunswick: ], pp. 159–166. | |||

| * Erens, Patricia (1979) ''Akira Kurosawa: a guide to references and resources''. Boston: G.K.Hall. | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Galbraith IV |first=Stuart |title=Japanese Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Films |publisher=McFarland |date=1994 |isbn=0-89950-853-7 |author-link=Stuart Galbraith IV}} | |||

| * {{cite journal |last1=Heider |first1=Karl G. |title=The Rashomon Effect: When Ethnographers Disagree |journal=] |date=March 1988 |volume=90 |issue=1 |pages=73–81 |doi=10.1525/aa.1988.90.1.02a00050}} | |||

| * Kauffman, Stanley (1987) "The Impact of Rashomon" in ] (ed.) ''Rashomon''. New Brunswick: ], pp. 173–177. | |||

| * McDonald, Keiko I. (1987) "The Dialectic of Light and Darkness in Kurosawa's Rashomon" in ] (ed.) ''Rashomon''. New Brunswick: ], pp. 183–192. | |||

| * Naas, Michael B. (1997) "Rashomon and the Sharing of Voices Between East and West." in Sheppard, Darren, et al., (eds.) ''On Jean-Luc Nancy: The Sense of Philosophy.'' New York: Routledge, pp. 63–90. | |||

| * ] (1987) "Rashomon" in Richie, Donald (ed.) ''Rashomon''. New Brunswick: ], pp. 1–21. | |||

| * ] (1987) "Rashomon" in ] (ed.) ''Rashomon'' New Brunswick: ], pp. 167–172. | |||

| * Tyler, Parker. "Rashomon as Modern Art" (1987) in ] (ed.) ''Rashomon''. New Brunswick: ], pp. 149–158. | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| {{Commons category|Rashomon}} | |||

| {{Wikiquote|Rashomon (film)}} | |||

| * {{IMDb title}} | |||

| * {{TCMDb title}} | |||

| * {{Rotten Tomatoes}} | |||

| * {{Mojo title}} | |||

| * , an essay by ] at the ] | |||

| {{Akira Kurosawa}} | |||

| {{In a Grove}} | |||

| {{Japanese submissions for the Academy Award}} | |||

| {{Navboxes | |||

| |title = Awards for ''Rashomon'' | |||

| |list = | |||

| {{Academy Award Best Foreign Language Film}} | |||

| {{Academy Honorary Award}} | |||

| {{National Board of Review Award for Best Foreign Language Film}} | |||

| {{Golden Lion}} | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Portal bar|Japan|Film|1950s}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Rashomon (Film)}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Revision as of 04:39, 22 December 2024

1950 film by Akira Kurosawa For other uses, see Rashomon (disambiguation).

| Rashomon | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Akira Kurosawa |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | "In a Grove" by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa |

| Produced by | Jingo Minoura |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Kazuo Miyagawa |

| Edited by | Shigeo Nishida |

| Music by | Fumio Hayasaka |

| Production company | Daiei Film |

| Distributed by | Daiei |

| Release dates |

|

| Running time | 88 minutes |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

| Budget | ¥15–20 million |

| Box office | $1 million |

Rashomon (Japanese: 羅生門, Hepburn: Rashōmon) is a 1950 Japanese jidaigeki film directed by Akira Kurosawa from a screenplay he co-wrote with Shinobu Hashimoto. Starring Toshiro Mifune, Machiko Kyō, Masayuki Mori, and Takashi Shimura, it follows various people who describe how a samurai was murdered in a forest. The plot and characters are based upon Ryūnosuke Akutagawa's short story "In a Grove", with the title and framing story taken from Akutagawa's "Rashōmon". Every element is largely identical, from the murdered samurai speaking through a Shinto psychic to the bandit in the forest, the monk, the assault of the wife, and the dishonest retelling of the events in which everyone shows their ideal self by lying.

Production began in 1948 at Kurosawa's regular production firm Toho but was canceled as it was viewed as a financial risk. Two years later, Sōjirō Motoki pitched Rashomon to Daiei Film upon the completion of Kurosawa's Scandal. Daiei initially turned it down but eventually agreed to produce and distribute the film. Principal photography lasted from July 7 to August 17, 1950, taking place primarily in Kyoto on an estimated ¥15–20 million budget. When creating the film's visual style, Kurosawa and cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa experimented with various methods such as pointing the camera at the sun, which was considered taboo. Post-production took only one week and was decelerated by two fires.

Rashomon premiered at the Imperial Theatre on August 25, 1950, and was distributed throughout Japan the following day, to moderate commercial success, becoming Daiei's fourth highest-grossing film of 1950. Japanese critics praised the experimental direction and cinematography but criticized its adapting of Akutagawa's story and complexity. Upon winning the Golden Lion at the 12th Venice International Film Festival, Rashomon became the first Japanese film to attain significant international reception, garnering critical acclaim and earning roughly $800,000 abroad. It later won Best Foreign Language Film at the 24th Academy Awards, and was nominated for Best Film at the 6th British Academy Film Awards.

Rashomon is now considered one of the greatest films ever made and among the most influential movies from the 20th century. It pioneered the Rashomon effect, a plot device that involves various characters providing subjective, alternative, and contradictory versions of the same incident. In 1999, critic Andrew Johnston asserted that "the film's title has become synonymous with its chief narrative conceit".

Plot

In Heian-era Kyoto, a woodcutter and a priest, taking shelter from a downpour under the Rashōmon city gate, recount a story of a recent assault and murder. Baffled at conflicting accounts of the same event, the woodcutter and the priest are joined by a commoner. The woodcutter claims he had found the body of a murdered samurai three days earlier, alongside the samurai's cap, his wife's hat, cut pieces of rope, and an amulet. The priest claims he had seen the samurai travel with his wife on the day of the murder. Both testify in court before a policeman presents the main suspect, a captured bandit named Tajōmaru.

In Tajōmaru's version of events, he follows the couple after spotting them traveling in the woods. He tricks the samurai into leaving the trail by lying about finding a burial pit filled with ancient artifacts. He subdues the samurai and attempts to rape his wife, who tries to defend herself with a dagger. Tajōmaru then seduces the wife, who, ashamed of the dishonor of having been with two men, asks Tajōmaru to duel her husband so she may go with the man who wins. Tajōmaru agrees; the duel ends with Tajōmaru killing the samurai. He then finds the wife has fled.

The wife, having been found by the police, delivers a different testimony; in her version of events, Tajōmaru leaves immediately after assaulting her. She frees her husband from his bonds, but he stares at her with contempt and loathing. The wife tries to threaten him with her dagger but then faints from panic. She awakens to find her husband dead, with the dagger in his chest. In shock, she wanders through the forest until coming upon a pond and attempts to drown herself but fails.