| Revision as of 01:47, 26 December 2006 view sourceVoABot II (talk | contribs)Rollbackers274,019 editsm BOT - Reverted edits by 9-11 Veritate {information} to revision #96481174 by "VoABot II".← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 18:00, 23 December 2024 view source Steven2345 (talk | contribs)67 editsm →Arrest and trial: Fixed typo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{pp-semi-indef|small=yes}} | |||

| ] ] ]] | |||

| {{Short description|American domestic terrorist (1968–2001)}} | |||

| {{For|the United States Navy sailor|Timothy R. McVeigh}} | |||

| {{Redirect|Robert Kling|the footballer|Robert Kling (footballer)}} | |||

| {{Infobox mass murderer | |||

| '''Timothy James McVeigh''' (], ] – ], ]) was an ] ] ] of eleven federal offenses and ultimately ] as a result of his role in the ], ] ]. The bombing, which claimed 168 lives, is considered the deadliest incident of ] in U.S. history. | |||

| | name = Timothy McVeigh | |||

| | image = McVeighGXMugshot (cropped).png | |||

| | image_size = | |||

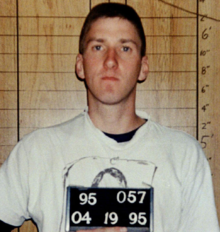

| | caption = ] of McVeigh taken after his arrest | |||

| | birth_name = Timothy James McVeigh | |||

| | birth_date = {{birth date|1968|4|23}} | |||

| | birth_place = ], U.S. | |||

| | death_date = {{death date and age|2001|6|11|1968|4|23}} | |||

| | death_place = ], ], U.S. | |||

| | death_cause = ] | |||

| | partners = ]<br />] | |||

| | date = April 19, 1995 | |||

| | time = 9:02 a.m. (]) | |||

| | targets = ] | |||

| | locations = ]<br />], Oklahoma | |||

| | fatalities = 167–169<ref>https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/oklahoma-city-bombing</ref><ref>{{Cite report |url=https://oklahoma.gov/content/dam/ok/en/health/health2/documents/okc-bombing.pdf |title=Oklahoma City Bombing Injuries |last1=Shariat |first1=Sheryll |last2=Mallonee |first2=Sue |date=December 1998 |publisher=Injury Prevention Service, Oklahoma State Department of Health |pages=2–3 |language=en |last3=Stidham |first3=Shelli Stephens |author-link= |access-date=21 October 2024}}</ref> | |||

| | injuries = 684<ref>{{Cite report |url=https://oklahoma.gov/content/dam/ok/en/health/health2/documents/okc-bombing.pdf |title=Oklahoma City Bombing Injuries |last1=Shariat |first1=Sheryll |last2=Mallonee |first2=Sue |date=December 1998 |publisher=Injury Prevention Service, Oklahoma State Department of Health |pages=2–3 |language=en |last3=Stidham |first3=Shelli Stephens |author-link= |access-date=21 October 2024}}</ref> | |||

| | weapon = Ammonium nitrate and nitromethane ] | |||

| | alias = Tim Tuttle<ref name=washingtonpost/><br />Daryl Bridges<ref name="trutv7"/><br />Robert Kling | |||

| | motive = ]<br />Retaliation for the ], ], other government raids, ] and ] from ] attacks in foreign countries<ref name="McVeigh word essay"/> | |||

| | conviction = ] (8 counts)<br>]<br>]<br>] | |||

| | penalty = ] (August 1997) | |||

| | occupation = Soldier, security guard | |||

| | module = {{Infobox military person|embed=yes | |||

| |allegiance = | |||

| {{flag|United States}} | |||

| |branch = {{army|USA}} | |||

| |serviceyears = 1988–1991 | |||

| |rank = ] | |||

| |battles = ] | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Timothy James McVeigh''' (April 23, 1968 – June 11, 2001) was an American ] who masterminded and perpetrated the ] on April 19, 1995.<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8Z5wEpDK9d0C&dq=timothy+mcveigh+was+the+mastermind+1995+oklahoma+bombing&pg=PA178 |title=Western Democracies and the New Extreme Right Challenge |publisher=] |year=2004 |isbn=978-0-415-55387-2 |editor-last=Eatwell |editor-first=Roger |edition= |series=Routledge Studies in Extremism and Democracy |location=London |pages=178 |language=en |editor-last2=Mudde |editor-first2=Cas}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last1=Flowers |first1=R. Barri |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gh6q_-Vzc0YC&dq=timothy+mcveigh+was+the+mastermind+1995+oklahoma+bombing&pg=PA106 |title=Murders in the United States: Crimes, Killers and Victims of the Twentieth Century |last2=Flowers |first2=H. Lorraine |publisher=] |year=2004 |isbn=0-7864-2075-8 |pages=106 |language=en}}</ref> The bombing killed 168 people, including 19 children, injured 684, and destroyed one-third of the ].<ref>https://memorialmuseum.com/experience/their-stories/those-who-were-killed/</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Mallonee |first1=S. |last2=Shariat |first2=S. |last3=Stennies |first3=G. |last4=Waxweiler |first4=R. |last5=Hogan |first5=D. |last6=Jordan |first6=F. |date=1996-08-07 |title=Physical Injuries and Fatalities Resulting From the Oklahoma City Bombing |url=http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=406032 |journal=JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association |language=en |volume=276 |issue=5 |pages=382–387 |doi=10.1001/jama.1996.03540050042021 |issn=0098-7484}}</ref><ref>{{Cite report |url=https://oklahoma.gov/content/dam/ok/en/health/health2/documents/okc-bombing.pdf |title=Oklahoma City Bombing Injuries |last1=Shariat |first1=Sheryll |last2=Mallonee |first2=Sue |date=December 1998 |publisher=Injury Prevention Service, Oklahoma State Department of Health |pages=2–3 |language=en |last3=Stidham |first3=Shelli Stephens |author-link= |access-date=21 October 2024}}</ref> It remains the deadliest act of ] in U.S. history.<ref name="ABC News">{{Cite news|last1=Levine|first1=Mike|last2=Margolin|first2=Josh|last3=Hosenball|first3=Alex|last4=Wagnon Courts|first4=Jenny|title=Nation's deadliest domestic terrorist inspiring new generation of hate-filled 'monsters,' FBI records show|url=https://abcnews.go.com/amp/US/nations-deadliest-domestic-terrorist-inspiring-generation-hate-filled/story?id=73431262|work=ABC News|date=6 October 2020|access-date=21 May 2022}}</ref> | |||

| == Biography == | |||

| McVeigh was raised in Western New York State, being born in ] (near ]) and received his high school diploma from ] in ]. His parents divorced when he was ten years old. McVeigh had been a registered member of the ] in New York and was a member of the ] while in the military.<ref>Profile of ], ], ], accessed ], ].</ref> | |||

| A ] veteran, McVeigh became radicalized by anti-government beliefs. He sought revenge against the ] for the 1993 ], as well as the 1992 ] incident. McVeigh expressed particular disapproval of federal agencies such as the ] (ATF) and the ] (FBI) for their handling of issues regarding ]. He hoped to inspire a revolution against the federal government, and he defended the bombing as a legitimate tactic against what he saw as a ] government.<ref name="mcveigh_dead"/> He was arrested shortly after the bombing and indicted on 160 state offenses and 11 federal offenses, including the use of a ]. He was found guilty on all counts in 1997 and sentenced to death.<ref name="cnn 3-29-01"/> | |||

| ===Religious beliefs=== | |||

| After his parents' divorce, McVeigh and his siblings lived with their father, a devout ] who often attended Daily Mass. Some degree of religious conviction may have remained with him throughout his life. In a recorded interview with '']''<ref>Patrick Cole, ], ], accessed ], ],</ref> he professed his belief in "a God". ] reported that McVeigh wrote a letter claiming to be an ]<ref>Julian Borger, ''] Online'', ], ], accessed ], ]</ref>. | |||

| McVeigh was executed by lethal injection on June 11, 2001, at the ]. His ], which took place just over six years after the offense, was carried out in a considerably shorter time than for most inmates awaiting execution.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Time on Death Row|url=https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/death-row/death-row-time-on-death-row|access-date=2021-08-13|website=Death Penalty Information Center|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210812121757/https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/death-row/death-row-time-on-death-row|archive-date=2021-08-12|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| === Military career === | |||

| ==Early life== | |||

| ] | |||

| McVeigh was born on April 23, 1968, in ], ], the only son and the second of three children of his ] parents, Noreen Mildred "Mickey" Hill (1945–2007) and William McVeigh. In 1866, McVeigh's great-great-grandfather Edward McVeigh emigrated from ] and settled in ].<ref>John O'Beirne Ranelagh (2012), ''A Short History of Ireland'', p. 341</ref><ref name=washingtonpost>{{cite news |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/longterm/oklahoma/bg/mcveigh.htm |title=An Ordinary Boy's Extraordinary Rage |first1=Dale |last1=Russakoff |last2=Kovaleski |first2=Serge F. |date=July 2, 1995 |page=A01 |access-date=April 12, 2010 |newspaper=] |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110131234415/http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/longterm/oklahoma/bg/mcveigh.htm |archive-date=2011-01-31 |url-status=live }}</ref> After McVeigh's parents divorced when he was ten years old, he was raised by his father in ].<ref name=washingtonpost/><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.wargs.com/other/mcveigh.html |title=Ancestry of Tim McVeigh |publisher=Wargs.com |access-date=June 4, 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101202020410/http://wargs.com/other/mcveigh.html |archive-date=2010-12-02 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| McVeigh claimed to have been a target of ] at school, and he took refuge in a fantasy world where he imagined retaliating against the bullies.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/talking_point/forum/1378651.stm |work=] |title=McVeigh author Dan Herbeck quizzed |date=June 11, 2001 |access-date=March 28, 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090425155356/http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/talking_point/forum/1378651.stm |archive-date=2009-04-25 |url-status=live }}</ref> At the end of his life, he stated his belief that the ] is the ultimate bully.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/1382540.stm |work=BBC News |title=Inside McVeigh's mind |date=June 11, 2001 |access-date=March 28, 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090701162129/http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/1382540.stm |archive-date=2009-07-01 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In May ], he enlisted in the ].<ref>Douglas O. Linder, , online posting, ], Law School faculty projects, ], accessed ], ]; cf. '''', transcript of program broadcast on ], ], ], 11:30 p.m. ET]. </ref> He was a decorated veteran of the United States Army, having served in the Gulf War, where he was awarded a ]. He had been a top scoring gunner with the 25 mm cannon of the lightly armored ] used by the ] to which he was assigned. He served at ], before ]. His superiors and friends thought of him as a model soldier. At Fort Riley, McVeigh completed the ] (PLDC), an Army school required for specialists and corporals to be promoted to sergeant. McVeigh had always wanted to join the ], the Army's Elite Special Forces. <br> After his return from the war, he entered the program for ] to become a Green Beret, but dropped out after the second day of an early phase due to a lack of physical fitness (blisters from new boots acquired on a five-mile march); after this failure, for reasons not fully established, McVeigh decided to leave the Army entirely and received his early discharge on ], ].<ref>See Hoffman, ; Hoffman finds many speculations published in the media about this episode in McVeigh's life as a soldier inaccurate and based on false information.</ref> | |||

| Most who knew McVeigh remember him as being very shy and withdrawn while a few described him as an outgoing and playful child who withdrew as an adolescent. He is said to have had only one girlfriend as an adolescent; he later told journalists that he did not have any idea how to impress girls.<ref name=bbcprofile>{{cite news |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/americas/1321244.stm |work=BBC News |title=Profile: Timothy McVeigh |date=May 11, 2001 |access-date=March 28, 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070217172343/http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/americas/1321244.stm |archive-date=2007-02-17 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| === Post-military activities and lifestyle === | |||

| After leaving the Army, beginning in 1992, his lifestyle grew increasingly transient. At first he worked briefly near his native Pendleton, as a security guard (Hoffman). A few months before the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995, he returned to ], outside Fort Riley. | |||

| While in high school McVeigh became interested in computers, and hacked into government computer systems on his ] under the handle The Wanderer, taken from the ]. In his ] he was named "most promising computer programmer" of ] (as well as "Most Talkative" by his classmates as a joke as he did not speak much)<ref>Lou Michel and Dan Herbeck, '']'' (2002), pp. 31–32</ref><ref name="archive.seattletimes.com">{{Cite web |title=Timothy Mcveigh - From A Loner To Fanatic {{!}} The Seattle Times |url=https://archive.seattletimes.com/archive/?date=19950505&slug=2119431 |access-date=2022-11-17 |website=archive.seattletimes.com}}</ref> but had relatively poor grades until his 1986 graduation.<ref name=washingtonpost/><ref name="jacobs"/> | |||

| McVeigh experimented with methamphetamines.<ref>. </ref> Many of his associations leading up to the years of the bombing were involved in heavy meth use and/or manufacture. Methamphetamine use is associated with paranoid ideations.<ref>"Most people using very high doses may become psychotic, because amphetamines can cause severe anxiety, paranoia, and a distorted sense of reality. Psychotic reactions include auditory and visual hallucinations (hearing and seeing things that are not there) and a feeling of having unlimited power (omnipotence). Although these effects can occur in any user, people with a mental health disorder, such as schizophrenia, are more vulnerable to them." </ref> | |||

| He was introduced to firearms by his grandfather. McVeigh told people of his wish to become a gun shop owner and sometimes took firearms to school to impress his classmates. He became intensely interested in ] as well as the ] after he graduated from high school and read magazines such as '']''. He briefly attended ] before dropping out.<ref name="a mind">{{cite book |last=Chase |first=Alston|title=A Mind for Murder: The Education of the Unabomber and the Origins of Modern Terrorism |year=2004 |publisher=W. W. Norton & Company |isbn=0393325563 |page=370}}</ref><ref>Smith, Brent L., Damhousse, Kelly R. and Roberts, Paxton, ''Pre-Incident Indicators of Terrorist Incidents: The Identification of Behavioral, Geographic and Temporal Patterns of Preparatory Conduct'', Document No.: 214217, May 2006, p. 234, found at {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080312233139/http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/214217.pdf |date=2008-03-12 }}, {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160306230106/https://www.scribd.com/doc/1227830/Criminal-Justice-Reference-214217 |date=2016-03-06 }} and {{Dead link|date=December 2022 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}. Retrieved July 22, 2009.</ref> After dropping out of college, McVeigh worked as an armored car guard and was noted by co-workers as being obsessed with guns. One co-worker recalled an instance when McVeigh came to work "looking like ]" as he was wearing ]s.<ref name="washingtonpost" /> | |||

| == Bombing == | |||

| ==Military career== | |||

| Working at a lakeside campground near his old Army post, McVeigh constructed an ] ] arranged in the back of a rented Ryder truck. The bomb consisted of about 5,000 pounds (2,300 kg) of ], an agricultural fertilizer, and ], an explosive motor-racing fuel. | |||

| In May 1988, at the age of 20, McVeigh enlisted in the United States Army and attended Basic Training and Advanced Individual Training at the ] at ], Georgia.<ref>Linder, Douglas O. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110223000407/http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/mcveigh/mcveighaccount.html |date=2011-02-23 }}, online posting, ], Law School faculty projects, 2006, accessed August 7, 2006 feb 17; cf. '' {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070313110452/http://edition.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0106/09/pitn.00.html |date=2007-03-13 }}'', transcript of program broadcast on ], June 9, 2001, 11:30 p.m. ET. <!----></ref> While in the military, McVeigh used much of his spare time to read about firearms, ], and explosives.<ref>Michel, Herbeck 2002 p. 61</ref> McVeigh was reprimanded by the military for purchasing a "]" T-shirt at a ] rally where they were objecting to black servicemen who wore "]" T-shirts around a military installation (primarily Army).<ref>Michel, Herbeck 2002 pp. 87–88</ref> His future co-conspirator ] was his platoon guide. He and Nichols quickly got along with their similar backgrounds as well as their views in gun collecting and survivalism.<ref name="archive.seattletimes.com" /> The two were later stationed together at ] in ], where they met and became friends with their future accomplice, ]. | |||

| McVeigh was a top-scoring gunner with the ] of the ]s used by the ] and was promoted to sergeant. After being promoted, McVeigh earned a reputation for assigning undesirable work to black servicemen and using derogatory language.<ref name="washingtonpost" /> He was stationed at Fort Riley before being deployed on ].<ref name="CNN 2001">{{cite web |title=Timothy McVeigh |url=https://www.cnn.com/2001/US/03/29/profile.mcveigh/ |website=CNN |access-date=September 16, 2024 |date=March 29, 2001}}</ref> | |||

| On ] ], McVeigh drove the truck to the front of the ] just as federal offices and its day care center opened for the day. Prosecutors said McVeigh strode away from the truck after he ignited a timed fuse from the front of the truck. At 9:02 a.m., a massive explosion collapsed the north half of the building. 168 people died and 850 more were injured in the explosion.<ref></ref> The 168th victim, rescue worker Rebecca Anderson,<ref> </ref> died after the initial blast, when it is believed, the back of her head was struck by a piece of debris that had fallen from the building.<ref>{{cite web | date =07/27/2004 | title =Rebecca Anderson Scholarship Information |Oklahoma Department of Career and Technology Education | url =http://www.okcareertech.org/health/HOSA/scholarship/rebecca_anderson_scholarship_inf.htm}}Retrieved on Nov. 16, 2006</ref>. Some of the victims were small children in a day care center located on the ground floor of the building. (Later, McVeigh did not express remorse for these "collateral damage" deaths, but he said he might have chosen a different target if he had known the day care center was there.<ref>See Michel and Herbeck; cf. Walsh: | |||

| :According to Michel and Herbeck, McVeigh claimed not to have known that a day-care center was located in the Murrah Building, and that if he had known it, in his own words, “it might have given me pause to switch targets. That's a large amount of collateral damage.” | |||

| In an interview before his execution, McVeigh said that he hit an Iraqi tank more than 500 yards away on his first day in the war and then the Iraqis surrendered. He also decapitated an Iraqi soldier with cannon fire from 1,100 yards away. He said he was later shocked to see ] while leaving ] after U.S. troops routed the Iraqi Army. McVeigh received several service awards, including the ]<ref>{{cite book |last1=Gill |first1=Paul|title=Lone-Actor Terrorists: A behavioural analysis|date=2015 |publisher=] |isbn=9781317660163|page=141}}</ref><ref name=washingtonpost/> ],<ref name="jacobs">{{cite web |url=http://www.tulsaworld.com/archives/the-radicalization-of-timothy-mcveigh/article_49b91161-74c7-538f-8183-e5f957f45aa1.html |title=The Radicalization Of Timothy McVeigh |last=Jacobs |first=Sally |date=June 10, 1995 |publisher=tulsaworld.com |access-date=November 18, 2014}}</ref> ],<ref name="willman">{{cite web |url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1995-04-28-mn-59919-story.html |title=Investigators Believe Bombing Was the Work of 4 or 5 People: Terrorism: Father, son are under scrutiny. FBI says 3 witnesses can place McVeigh near blast scene. Arizona town emerges as possible base for plotters. |last1=Willman |first1=David |last2=Ostrow |first2=Ronald J. |date=April 28, 1995 |work=] |page=4 |access-date=18 November 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141221131349/http://articles.latimes.com/1995-04-28/news/mn-59919_1_material-witness/4 |archive-date=2014-12-21 |url-status=live }}</ref> ],<ref name="willman"/> and the ].<ref name="jacobs"/> | |||

| :Michel and Herbeck quote McVeigh, with whom they spoke for some 75 hours, on his attitude to the victims: “To these people in Oklahoma who have lost a loved one, I'm sorry but it happens every day. You're not the first mother to lose a kid, or the first grandparent to lose a grandson or a granddaughter. It happens every day, somewhere in the world. I'm not going to go into that courtroom, curl into a fetal ball, and cry just because the victims want me to do that.” | |||

| McVeigh aspired to join the ] (SF). After returning from the ], he entered the selection program, but withdrew on the second day of the 21-day assessment and selection course for the Special Forces, telling other recruits that he had injured an ankle. However, in a letter to his superiors, McVeigh wrote that he was not "physically ready".<ref>{{cite news |last1=Jackson |first1=David |last2=Dorning |first2=Michael |title=MCVEIGH: LONER AND SOLDIER |url=https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1995-05-07-9505070305-story.html |access-date=19 October 2022 |work=] |date=7 May 1995|url-access=registration}}</ref> McVeigh decided to leave the Army and was ] in 1991.<ref>{{cite news|last1=KIFNER|first1=JOHN|title=McVEIGH'S MIND: A special report.;Oklahoma Bombing Suspect: Unraveling of a Frayed Life|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1995/12/31/us/mcveigh-s-mind-special-report-oklahoma-bombing-suspect-unraveling-frayed-life.html|newspaper=New York Times|date=31 December 1995 |access-date=9 January 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161218104536/http://www.nytimes.com/1995/12/31/us/mcveigh-s-mind-special-report-oklahoma-bombing-suspect-unraveling-frayed-life.html|archive-date=2016-12-18|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| :McVeigh's lack of remorse for the deaths of 19 children, as well as secretaries, clerks, administrators and others employed by the federal government, and the dozens of people who were merely visiting the building, should serve as a warning about the character of elements promoted by the ultra-right in the US. They are brutal, cowardly and ruthless.</ref>) | |||

| == Post-military life == | |||

| According to the Oklahoma City Memorial Institute for the Prevention of Terrorism (MIPT), over 300 buildings were damaged and more than 12,000 volunteers and rescue workers were involved in rescue, recovery, and support operations. | |||

| McVeigh wrote letters to local newspapers complaining about taxes. In 1992, he wrote: | |||

| {{Blockquote|Taxes are a joke. Regardless of what a political candidate "promises," they will increase. More taxes are always the answer to government mismanagement. They mess up. We suffer. Taxes are reaching cataclysmic levels, with no slowdown in sight. Is a Civil War Imminent? Do we have to shed blood to reform the current system? I hope it doesn't come to that. But it might.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.cnn.com/US/OKC/faces/Suspects/McVeigh/1st-letter6-15/index.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080119111020/http://www.cnn.com/US/OKC/faces/Suspects/McVeigh/1st-letter6-15/index.html|archive-date=2008-01-19|title=McVeigh 1st letter|publisher=CNN}}</ref> }} | |||

| McVeigh also wrote to Representative ] (]–New York),<ref name="goldstein">{{cite web|url=http://articles.philly.com/1995-05-03/news/25671989_1_union-sun-journal-handwritten-letter-stun-guns|title=Mcveigh Wrote To Congressman About 'Self-defense'|last=Goldstein|first=Steve|date=May 3, 1995|publisher=philly.com|access-date=November 18, 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304092453/http://articles.philly.com/1995-05-03/news/25671989_1_union-sun-journal-handwritten-letter-stun-guns|archive-date=2016-03-04|url-status=dead}}</ref> complaining about the arrest of a woman for carrying ]: {{Blockquote|It is a lie if we tell ourselves that the police can protect us everywhere at all times. Firearms restrictions are bad enough, but now a woman can't even carry Mace in her purse?<ref name="goldstein"/>}} | |||

| ==Arrest, trial, conviction and sentencing== | |||

| McVeigh later moved with Nichols to Nichols’ brother James’ farm around ].<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.mlive.com/news/flint/2015/04/oklahoma_city_bombing_memories.html | title=Oklahoma City bombing memories fade in rural Michigan town at center of plot | author=Dominic Adams | date=19 April 2015 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190410163157/https://www.mlive.com/news/flint/2015/04/oklahoma_city_bombing_memories.html | archive-date=10 April 2019 | url-status=live | access-date=17 November 2022 }}</ref> While visiting friends, McVeigh reportedly complained that the Army had implanted a ] into his buttocks so that the government could keep track of him.<ref name=washingtonpost/> McVeigh worked long hours in a ] and felt that he did not have a home. He sought romance, but his advances were rejected by a co-worker and he felt nervous around women. He believed that he brought too much pain to his loved ones.<ref>Michel, Herbeck 2002 p. 102</ref> He grew angry and ] at his difficulties in finding a girlfriend. He took up ].<ref>Michel, Herbeck 2002 p. 114</ref> Unable to pay gambling debts, he took a cash advance and then defaulted on his repayments. He began looking for a state with low taxes so that he could live without heavy government regulation or high taxes. He became enraged when the government told him that he had been overpaid $1,058 while in the Army and he had to pay back the money. He wrote an angry letter to the government, saying: {{quote|Go ahead, take everything I own; take my dignity. Feel good as you grow fat and rich at my expense; sucking my tax dollars and property.<ref>Michel, Herbeck 2002 pp. 117-118</ref>}} | |||

| ] | |||

| McVeigh introduced his sister to anti-government literature, but his father had little interest in these views. He moved out of his father's house and into an apartment that had no telephone. This made it impossible for his employer to contact him for overtime assignments. He quit the ] (NRA), believing that it was too weak on gun rights.<ref>Michel, Herbeck (2002) p.111</ref> | |||

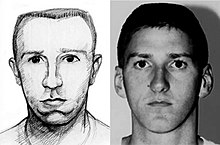

| Through its serial number, the FBI identified the rear axle found in the wreckage as coming from a ] Rental Junction City agency truck. Workers at the agency assisted an FBI artist in creating a sketch of the renter who had used the alias "Kling". The sketch was shown in the area and on the same day was identified by manager Lea McGown of the Dreamland Hotel as Timothy McVeigh. | |||

| === 1993 Waco siege and gun shows === | |||

| Shortly after the bombing, while driving on ] in ], near ], McVeigh was stopped by ], an Oklahoma Highway Patrol trooper from ].<ref>See Second Lieutenant Charles J. Hanger, Oklahoma Highway Patrol," ''National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund'', copyright 2004-2006, accessed ], ].</ref> Officer Hanger had passed McVeigh's yellow ] ] and noticed it had no license plate. McVeigh was arrested for driving without a license plate and carrying and transporting a loaded firearm. Three days later, while still in jail, McVeigh was identified as the subject of the nationwide manhunt. | |||

| In 1993, McVeigh drove to ], during the ] to show his support. At the scene, he distributed pro-] literature and bumper stickers bearing slogans such as, "When guns are outlawed, I will become an outlaw." He told a student reporter: | |||

| {{quote|The government is afraid of the guns people have because they have to have control of the people at all times. Once you take away the guns, you can do anything to the people. You give them an inch and they take a mile. I believe we are slowly turning into a socialist government. The government is continually growing bigger and more powerful, and the people need to prepare to defend themselves against government control.<ref>{{cite web|title=The Guns of Spring |url=http://www2.citypaper.com/eat/story.asp?id=17888 |work=Baltimore City Paper |publisher=Times-Shamrock |author=Brian Morton |date=April 15, 2009 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141129155757/http://www2.citypaper.com/eat/story.asp?id=17888 |archive-date=November 29, 2014 }}</ref><ref>; ''The Smirking Chimp''; 2009</ref> }} | |||

| On ] ] McVeigh was indicted on 11 counts, including conspiracy to use a weapon of mass destruction, use of a weapon of mass destruction, destruction by explosives, and eight counts of first-degree murder.<ref> | |||

| *Count 1 was "conspiracy to detonate a weapon of mass destruction" in violation of 18 USC § 2332a, culminating in the deaths of 168 people and destruction of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. ?? | |||

| *Count 2 was "use of a weapon of mass destruction" in violation of 18 USC § 2332a (2)(a) & (b). | |||

| *Count 3 was "destruction by explosives resulting in death", in violation of 18 USC § 844(f)(2)(a) & (b). | |||

| *Counts 4 through 11 were first degree murder in violation of 18 USC § 1111, 1114, & 2 and 28 CFR § 64.2(h), each count in connection to one of the 8 law enforcement officers who were killed during the attack.</ref> On October 20, 1995, the government filed notice that it would seek the death penalty. | |||

| For the five months following the Waco siege, McVeigh worked at ]s and handed out free cards printed with the name and address of ], an FBI sniper, "in the hope that somebody in the ] would assassinate the sharpshooter." Horiuchi's actions while an FBI agent have drawn controversy, specifically his shooting and killing of ]'s wife while she held an infant child. McVeigh wrote ] to Horiuchi, suggesting that "what goes around, comes around". McVeigh later considered putting aside his plan to target the Murrah Building to target Horiuchi or a member of his family instead.<ref>{{cite book|last=Martinez|first=J. Michael |title=Terrorist Attacks on American Soil: From the Civil War Era to the Present|year=2012|publisher=Rowman & Littlefield Publishers|isbn=978-1442203242|page=289}}</ref> | |||

| On ] ] the Court granted a ], and ordered the case transferred from ] to the US District Court in ], Colorado presided over by U.S. District Judge ]. | |||

| McVeigh became a fixture on the gun show circuit, traveling to forty states and visiting about eighty gun shows. He found that the further west he went, the more anti-government sentiment he encountered, at least until he got to what he called "The People's Socialist Republic of California."<ref>Michel, Herbeck (2002) p. 121</ref> McVeigh sold survival items and copies of '']''. One author said: {{quote|In the gun show culture, McVeigh found a home. Though he remained skeptical of some of the most extreme ideas being bandied around, he liked talking to people there about the United Nations, the federal government, and possible threats to American liberty.<ref>Handlin, Sam (2001) {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071014123027/http://www.courttv.com/news/mcveigh_special/profile_ctv.html |date=2007-10-14 }} Court TV Online.</ref>}} | |||

| McVeigh instructed his lawyers to use a "necessity" defense and to argue that his bombing of the Murrah Federal Building was a justifiable response to what McVeigh believed were the crimes of the U.S. government at ], Texas, during the 51-day siege of the ] complex that resulted in the death of 76 Branch Davidian members.<ref>Douglas O. Linder, , online posting, ], Law School faculty projects, ], accessed ], ]. </ref> As part of his defense, McVeigh's lawyers showed the ] video '']'' to the jury at his trial.<ref>'''', transcript of program broadcast on ], ], ], 11:30 p.m. ET. . For a description of the video by its director, Linda Thompson, see '''', hosted by wfmu.org, a New Jersey FM radio station via serendipity.li, accessed ], ].</ref> | |||

| == Arizona with Fortier == | |||

| On ] ], McVeigh was found guilty on all 11 counts of the indictment. <ref>Mark Eddy, George Lane, Howard Pankratz, and Steven Wilmsen, ''Denver Post Online'' ], ], accessed ], ]:<blockquote> Although 168 people, including 19 children, were killed in the April 19, 1995 explosion, but murder charges were only brought against McVeigh for the eight federal agents who were on duty when the 5,000 pound fuel oil and fertilizer bomb ripped away the face of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building.<br><br> | |||

| McVeigh had a road atlas with hand-drawn designations of the most likely places for nuclear attacks and considered buying property in ], which he determined to be in a "nuclear-free zone." He lived with ] in ], and the two became so close that he served as ] at Fortier's wedding. McVeigh experimented with ] and ] after first researching their effects in an encyclopedia.<ref>{{cite news| url=https://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9802E3DA1438F937A25752C1A961958260 | work=The New York Times | title=Jury Hears of McVeigh Remarks About Nichols and Bomb Making | first=Jo | last=Thomas | date=November 14, 1997 | access-date=March 28, 2010}}</ref> He was never as interested in drugs as Fortier was, and one of the reasons they parted ways was that McVeigh grew tired of Fortier's drug habits.<ref name="trutv6">{{cite web|url=http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/serial_killers/notorious/mcveigh/transit_6.html|title=Tim In Transit|last=Ottley|first=Ted|work=Timothy McVeigh & Terry Nichols: Oklahoma Bombing|publisher=TruTv|access-date=April 12, 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090601195011/http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/serial_killers/notorious/mcveigh/transit_6.html|archive-date=June 1, 2009|url-status=dead|df=mdy-all}}</ref> | |||

| Along with the eight counts of murder McVeigh was charged with conspiracy to use a weapon of mass destruction, using a weapon of mass destruction and destruction of a federal building.<br><br> | |||

| Oklahoma City District Attorney Bob Macy said he would file state charges in the other 160 murders after McVeigh's co-defendant, Terry Nichols, is tried later this year.</blockquote></ref> | |||

| == With Nichols, Waco siege, and radicalization == | |||

| On ], the same jury recommended that McVeigh receive the death penalty.<ref>See '']'', '''', ], ], ], accessed ], ].</ref> The U.S. Department of Justice brought federal charges against McVeigh for causing the deaths of the eight federal officers leading to a possible death penalty for McVeigh; it could not bring charges against McVeigh for the remaining 160 murders in federal court because those deaths fell under the jurisdiction of the state of Oklahoma. After McVeigh's conviction and sentencing (and after the Terry Nichols trial), the state of Oklahoma did not file the state charges in the other 160 murders against McVeigh, since he had already been sentenced to death in the federal trial.<ref>'''', transcript of program broadcast on ], ], ], 11:30 p.m. ET].</ref> | |||

| In April 1993, McVeigh headed for a farm in Michigan where former roommate ] lived. In between watching coverage of the Waco siege on TV, Nichols and his brother began teaching McVeigh how to make explosives by combining household chemicals in plastic jugs. The destruction of the Waco compound enraged McVeigh and convinced him that it was time to take action. He was particularly angered by the government's use of ] on women and children; he had been exposed to the gas as part of his military training and was familiar with its effects. The disappearance of certain evidence,<ref name="missingdoor">{{Cite news | url = http://www.austinchronicle.com/news/2000-08-18/78306/ | title = Prying Open the Case of the Missing Door | last = Bryce | first = Robert | work = ] | date = August 18, 2000 | access-date = 2014-02-13 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140225022024/http://www.austinchronicle.com/news/2000-08-18/78306/ | archive-date = 2014-02-25 | url-status=live }}</ref> such as the bullet-riddled steel-reinforced front door to the complex, led him to suspect a cover-up. | |||

| McVeigh's anti-government rhetoric became more radical. He began to sell ] (ATF) hats riddled with bullet holes, and a flare gun that he said could shoot down an "ATF helicopter".<ref name="cnn 3-29-01">{{cite news|url=http://archives.cnn.com/2001/US/03/29/profile.mcveigh/ |title=Timothy McVeigh: Convicted Oklahoma City Bomber |date=March 29, 2001 |publisher=CNN |access-date=April 12, 2010 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100301192549/http://archives.cnn.com/2001/US/03/29/profile.mcveigh/ |archive-date=March 1, 2010 }}</ref><ref>Editors (2000) {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070914045615/http://www.vpc.org/studies/tupfive.htm |date=2007-09-14 }} Violence Policy Center.</ref> He produced videos detailing the government's actions at Waco and handed out pamphlets with titles such as "U.S. Government Initiates Open Warfare Against American People" and "Waco Shootout Evokes Memory of ]." He began changing his answering machine greeting every couple of weeks to various quotes by ], such as "Give me liberty or give me death."<ref>Michel, Herbeck 2002 pp. 136–14-</ref> He began experimenting with making ]s and other small explosive devices. The government imposed ] which McVeigh believed threatened his livelihood.<ref name="trutv6"/> | |||

| ] | |||

| McVeigh dissociated himself from his boyhood friend Steve Hodge by sending him a 23-page farewell letter. He proclaimed his devotion to the ], explaining in detail what each sentence meant to him. McVeigh declared that: | |||

| ==Death== | |||

| {{quote|Those who betray or subvert the Constitution are guilty of sedition and/or treason, are domestic enemies and should and will be punished accordingly. | |||

| It also stands to reason that anyone who sympathizes with the enemy or gives aid or comfort to said enemy is likewise guilty. I have sworn to uphold and defend the Constitution against all enemies, foreign and domestic and I will. And I will because not only did I swear to, but I believe in what it stands for in every bit of my heart, soul and being. | |||

| I know in my heart that I am right in my struggle, Steve. I have come to peace with myself, my God and my cause. Blood will flow in the streets, Steve. Good vs. Evil. Free Men vs. Socialist Wannabe Slaves. Pray it is not your blood, my friend.<ref name="farewell letter">{{cite book |last=Balleck |first=Barry J. |title=Allegiance to Liberty: The Changing Face of Patriots, Militias, and Political Violence in America |publisher=Praeger |date=2015 |page=18 |isbn=978-1440830969 |url= https://books.google.com/books?id=E_k7BQAAQBAJ&pg=PA176}}</ref>}} | |||

| McVeigh felt the need to personally reconnoiter sites of rumored conspiracies. He visited ] in order to defy government restrictions on photography and went to ], to determine the veracity of rumors about ] operations. These turned out to be false; the Russian vehicles on the site were being configured for use in U.N.-sponsored humanitarian aid efforts. Around this time, McVeigh and Nichols began making bulk purchases of ], an agricultural ], for resale to ], since rumors were circulating that the government was preparing to ban it.<ref>Michel, Herbeck (2002) pp. 156–158</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| == Plan against federal building or individuals == | |||

| McVeigh's death sentence was delayed pending an appeal. One of his appeals was taken to the ], which denied ] on ], ]. He was ultimately executed by lethal injection at 7:14 a.m. on ], ], at the U.S. Federal Penitentiary in ]. He had dropped all of his existing appeals, while presenting no reason for doing so. He was 33 years old. | |||

| McVeigh told Fortier of his plans to blow up a federal building, but Fortier declined to participate. Fortier also told his wife about the plans.<ref>Michel, Herbeck (2002) pp. 161–162</ref> McVeigh composed two letters to the ], the first titled "Constitutional Defenders" and the second "ATF Read." He denounced government officials as "fascist tyrants" and "storm troopers," and warned: {{quote|ATF, all you tyrannical mother fuckers will swing in the wind one day for your treasonous actions against the Constitution of the United States. Remember the ].<ref>Martinez, J. Michael (2012) Lanham,, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. {{isbn|978-1442203242}} p.291</ref><ref name="trutv7">{{cite web|url=http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/serial_killers/notorious/mcveigh/turner_7.html |title=Imitating Turner |last=Ottley |first=Ted |work=Timothy McVeigh & Terry Nichols: Oklahoma Bombing |publisher=TruTv |access-date=April 10, 2010 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120119012918/http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/serial_killers/notorious/mcveigh/turner_7.html |archive-date=January 19, 2012 }}</ref>}} | |||

| McVeigh also wrote a letter to recruit a customer named Steve Colbern: | |||

| McVeigh invited California conductor/composer David Woodard to perform a 'prequiem' (a Mass for those who are about to die) on the eve of his execution, and he had also requested a Catholic chaplain. '']'' was performed under Woodard's baton by a local brass choir at St. Margaret Mary Church, located near the Terre Haute penitentiary, at 7:00 p.m. on ], to an audience that included the entirety of the next morning's witnesses. McVeigh chose ]'s poem "]" as his final statement. His ] consisted of two pints of ]'s mint chocolate chip ice cream. McVeigh's execution was the first of a convicted criminal by the U.S. federal government since the execution of ] in Iowa on ], ]. | |||

| {{quote|A man with nothing left to lose is a very dangerous man and his energy/anger can be focused toward a common/righteous goal. What I'm asking you to do, then, is sit back and be honest with yourself. Do you have kids/wife? Would you back out at the last minute to care for the family? Are you interested in keeping your firearms for their current/future monetary value, or would you drag that '06 through rock, swamp and cactus... to get off the needed shot? In short, I'm not looking for talkers, I'm looking for fighters... And if you are a fed, think twice. Think twice about the Constitution you are supposedly enforcing (isn't "enforcing freedom" an oxymoron?) and think twice about catching us with our guard down – you will lose just like ] did{{spaced ndash}}and your family will lose.<ref>Michel, Herbeck (2002) pp. 184–185</ref>}} | |||

| McVeigh began announcing that he had progressed from the "propaganda" phase to the "action" phase. He wrote to his Michigan friend Gwenda Strider, "I have certain other 'militant' talents that are in short supply and greatly demanded."<ref>Michel, Herbeck (2002) p. 195</ref> | |||

| His body was disposed of by cremation in the retort at Mattox Ryan Funeral home in Terre Haute under the direction of funeral director Kevin Nickles. The cremated remains were then given to his lawyer for disposition. McVeigh's remains were scattered in an undisclosed location. | |||

| McVeigh later said he considered "a campaign of individual assassination," with "eligible" targets including Attorney General ], Judge ] of ], who handled the ] trial; and ], a member of the FBI hostage-rescue team, who shot and killed Vicki Weaver in a standoff at a remote cabin at ], in 1992.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.digital-exp.com/doco/TimothyMcVeigh.html|title=Timothy McVeigh's Letter to Fox News|publisher=Digital-Exp.com|access-date=April 12, 2010|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://archive.today/20010823144750/http://www.digital-exp.com/doco/TimothyMcVeigh.html|archive-date=August 23, 2001}}</ref> He said he wanted Reno to accept "full responsibility in deed, not just words."<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.kuna.net.kw/ArticleDetails.aspx?id=1160520&language=en|title=McVeigh Considered Assassinating Reno, Other Officials|date=April 27, 2001|publisher=Kuwait News Agency|access-date=April 12, 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210512100425/https://www.kuna.net.kw/ArticleDetails.aspx?id=1160520&language=en|archive-date=2021-05-12|url-status=live}}</ref> Such an assassination seemed too difficult,<ref>{{cite news| url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/northamerica/usa/1317593/McVeigh-wanted-to-kill-US-attorney-general.html | archive-url=https://archive.today/20130505054631/http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/northamerica/usa/1317593/McVeigh-wanted-to-kill-US-attorney-general.html | url-status=live| archive-date=May 5, 2013 | work=The Daily Telegraph | location=London | title=McVeigh 'wanted to kill US attorney general' | date=April 28, 2001 | access-date=June 6, 2022}}</ref> and he decided that since federal agents had become soldiers, he should strike at them at their command centers.<ref>{{cite news | url=https://www.nytimes.com/2001/04/27/us/mcveigh-says-he-considered-killing-reno.html | archive-url=https://archive.today/20120714023654/http://www.nytimes.com/2001/04/27/us/mcveigh-says-he-considered-killing-reno.html | url-status=live | archive-date=July 14, 2012 | work=The New York Times | title=McVeigh Says He Considered Killing Reno | first=Susan | last=Saulny | date=April 27, 2001 | access-date=June 6, 2022}}</ref> According to McVeigh's authorized biography, he decided that he could make the loudest statement by bombing a federal building. After the bombing, he was ambivalent about his act and the deaths he caused; as he said in letters to his hometown newspaper, he sometimes wished that he had carried out a series of assassinations against police and government officials instead.<ref name=Oklahoman>{{cite web |url=https://www.oklahoman.com/story/news/2001/06/09/ready-for-execution-mcveigh-says-hes-sorry-for-deaths/62143432007/ |title=Ready for execution, McVeigh says he's sorry for deaths |publisher=The Oklahoman |date=June 9, 2001 |access-date=June 6, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120502095039/http://newsok.com/article/700006 |archive-date=2012-05-02 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ==Motivations for the bombing== | |||

| ==Oklahoma City bombing== | |||

| McVeigh claimed that the bombing was revenge for "what the U.S. government did at ] and ]."<ref>See newswire release, ], ], ], reposted on rickross.com, accessed ], ].</ref> He visited Waco during the standoff, where he spoke to a news reporter about his anger over what was happening there.<ref>Profile of ], ], ], accessed ], ].</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Oklahoma City bombing}} | |||

| ] two days after the ]]] | |||

| Working at a lakeside campground near McVeigh's old Army post, he and Nichols constructed an ] ] mounted in the back of a rented Ryder truck. The bomb consisted of about {{convert|5,000|lb|kg}} of ammonium nitrate and ]. | |||

| On April 19, 1995, McVeigh drove the truck to the front of the ] just as its offices opened for the day. Before arriving, he stopped to light a two-minute fuse. At 09:02, a large explosion destroyed the north half of the building. It killed 168 people, including 19 children in the day care center on the second floor, and injured 684 others.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ok.gov/health2/documents/OKC_Bombing.pdf|title=Oklahoma City Bombing Injuries|publisher=]|date=December 1998|access-date=2014-08-09|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140518063448/http://www.ok.gov/health2/documents/OKC_Bombing.pdf|archive-date=2014-05-18|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| McVeigh was considered by many an anti-government ], with a long background in the ] movement. He frequently quoted and alluded approvingly to the controversial novel '']'', which describes acts of ] similar to the crimes that he was convicted of perpetrating (Michel and Herbeck). Photocopies of pages sixty-one and sixty-two of ''The Turner Diaries'' were found in an envelope inside McVeigh's car. These pages depicted a fictitious mortar attack upon the U.S. Capitol in Washington.<ref>See Michel and Herbeck; cf. Walsh.</ref> | |||

| McVeigh said that he had not known that there was a daycare center on the second floor, and that he might have chosen a different target if he had known about it.<ref>See Michel and Herbeck; cf. Walsh:</ref><ref name="vidal">{{cite book |author-link=Gore Vidal |last=Vidal |first=Gore |title=Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace |pages=1, 81 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oF0ZTJEHubcC |isbn=978-1902636382 |year=2002|publisher=Clairview }}</ref> Nichols said that he and McVeigh did know about the daycare center in the building, and that they did not care.<ref name="Global Terrorism Database"> {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080629211532/http://209.232.239.37/gtd1/ViewIncident.aspx?id=6621 |date=2008-06-29}}</ref><ref name="washingtonpost.com">{{cite news |author1-last=Romano |author1-first=Lois |author2-first=Tom |author2-last=Kenworthy |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/longterm/oklahoma/stories/ok042597.htm |title=Prosecutor Paints McVeigh As 'Twisted' U.S. Terrorist |newspaper=The Washington Post |date=April 25, 1997 |page=A01 |access-date=2017-09-16 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170917164253/http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/longterm/oklahoma/stories/ok042597.htm |archive-date=2017-09-17 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In a book based on interviews before his execution, '']'', McVeigh stated he decapitated an Iraqi soldier with cannon fire on his first day in the war, and celebrated. But he said he later was shocked to be ordered to execute surrendering prisoners, and to see ] leaving ] after U.S. troops routed the Iraqi army. In interviews following the Oklahoma City bombing, McVeigh said he began harboring anti-government feelings during the Gulf War. Some question the veracity of this claim in light of McVeigh's attempts to become a Green Beret after returning from Iraq. | |||

| McVeigh's biographers, Lou Michel and Dan Herbeck, spoke with McVeigh in interviews totaling 75 hours. He said about the victims: | |||

| In 1998, an imprisoned McVeigh penned an essay that criticized US foreign policy towards Iraq as being hypocritical. | |||

| {{quote|To these people in Oklahoma who have lost a loved one, I'm sorry but it happens every day. You're not the first mother to lose a kid, or the first grandparent to lose a grandson or a granddaughter. It happens every day, somewhere in the world. I'm not going to go into that courtroom, curl into a fetal ball and cry just because the victims want me to do that.}} | |||

| :The administration has said that Iraq has no right to stockpile chemical or biological weapons (“weapons of mass destruction”) — mainly because they have used them in the past. | |||

| During an interview in 2000 with ] for television news magazine '']'', Bradley asked McVeigh for his reaction to the deaths of the nineteen children. McVeigh said: {{quote| I thought it was terrible that there were children in the building.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cbsnews.com/news/mcveigh-vents-on-60-minutes/|title=McVeigh Vents On '60 Minutes'|date=March 13, 2000|publisher=CBS News|access-date=November 18, 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141129043826/http://www.cbsnews.com/news/mcveigh-vents-on-60-minutes/|archive-date=2014-11-29|url-status=live}}</ref>}} | |||

| :Well, if that’s the standard by which these matters are decided, then the U.S. is the nation that set the precedent. The U.S. has stockpiled these same weapons (and more) for over 40 years. The U.S. claims that this was done for deterrent purposes during the “Cold War” with the Soviet Union. Why, then is it invalid for Iraq to claim the same reason (deterrence) — with respect to Iraq’s (real) war with, and the continued threat of, its neighbor Iran? | |||

| :… | |||

| :If Saddam is such a demon, and people are calling for war crimes charges and trials against him and his nation, why do we not hear the same cry for blood directed at those responsible for even greater amounts of “mass destruction” — like those responsible and involved in dropping bombs on the cities mentioned above? | |||

| According to the Oklahoma City Memorial Institute for the Prevention of Terrorism (MIPT), more than 300 buildings in the city were damaged. More than 12,000 volunteers and rescue workers took part in the rescue, recovery and support operations following the bombing. In reference to theories that McVeigh had assistance from others, he responded with a well-known line from the film '']'', "You can't handle the truth!" He added, "Because the truth is, I blew up the Murrah Building and isn't it kind of scary that one man could wreak this kind of hell?"<ref>{{cite news | url=https://www.nytimes.com/2001/03/29/us/no-sympathy-for-dead-children-mcveigh-says.html | archive-url=https://archive.today/20120713080119/http://www.nytimes.com/2001/03/29/us/no-sympathy-for-dead-children-mcveigh-says.html | url-status=live| archive-date=July 13, 2012 | work=The New York Times | title='No Sympathy' for Dead Children, McVeigh Says | first=Jo | last=Thomas | date=March 29, 2001 | access-date=March 28, 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| :The truth is, the U.S. has set the standard when it comes to the stockpiling and use of weapons of mass destruction.<ref>See by Timothy McVeigh, March 1998</ref> | |||

| == Arrest and trial == | |||

| ==Alleged accomplices== | |||

| ] | |||

| By tracing the ] of a rear axle found in the wreckage, the ] identified the vehicle as a ] rental box truck rented from ]. Workers at the agency assisted an FBI artist in creating a sketch of the renter, who had used the alias "Robert Kling". The sketch was shown in the area. Lea McGown, manager of the local Dreamland Motel, identified the sketch as Timothy McVeigh.<ref>{{cite magazine|url=http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,986240,00.html|title=Oklahoma City: The Weight Of Evidence|last1=Collins|first1=James|author2=Patrick E. Cole|author3=Elaine Shannon|magazine=Time|date=April 27, 1997|access-date=June 7, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100615022116/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,986240-5,00.html|archive-date=2010-06-15|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="trutv2">{{cite web|url=http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/serial_killers/notorious/mcveigh/snag_2.html |title=License Tag Snag |last=Ottley |first=Ted |work=Timothy McVeigh & Terry Nichols: Oklahoma Bombing |publisher=TruTv |access-date=April 12, 2010 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110829095824/http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/serial_killers/notorious/mcveigh/snag_2.html |archive-date=August 29, 2011 }}</ref> | |||

| Shortly after the bombing, while driving on ] in ], near ], McVeigh was stopped by ] Charles J. Hanger.<ref>See Second Lieutenant Charles J. Hanger, Oklahoma Highway Patrol," ''National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund'', copyright 2004–06. Retrieved August 8, 2006.</ref> Hanger had passed McVeigh's yellow 1977 ] and noticed that it had no license plate. McVeigh admitted to the state trooper{{snd}}who noticed a bulge under his jacket{{snd}}that he had a gun; the trooper arrested him for driving without plates and possessing an illegal firearm. McVeigh's ] permit was not legal in Oklahoma. McVeigh was wearing a shirt at that time with a picture of ] and the motto {{lang|la|]}} ('Thus always to tyrants'), the supposed words shouted by ] after he shot Lincoln.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.crimelibrary.com/serial_killers/notorious/mcveigh/turner_7.html |title=The Timothy McVeigh Story: The Oklahoma Bomber |access-date=July 12, 2007 |publisher=Crime Library |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120119012918/http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/serial_killers/notorious/mcveigh/turner_7.html |archive-date=January 19, 2012 }}</ref> On the back, it had a tree with a picture of three blood droplets and the ] quote, "The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants."<ref>{{cite news | url=http://www.cnn.com/US/9704/28/okc/ | work=CNN | title='Turner Diaries' introduced in McVeigh trial | access-date=May 25, 2010 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100529135944/http://www.cnn.com/US/9704/28/okc/ | archive-date=2010-05-29 | url-status=live }}</ref> Three days later, McVeigh was identified as the subject of the nationwide manhunt. | |||

| ], courthouse two days after the bombing]] | |||

| On August 10, 1995, McVeigh was indicted on 11 federal counts, including conspiracy to use a weapon of mass destruction, use of a weapon of mass destruction, destruction with the use of explosives, and eight counts of first degree murder for the deaths of law enforcement officers.<ref>Count 1: "conspiracy to detonate a weapon of mass destruction" in violation of 18 USC § 2332a, culminating in the deaths of 168 people and destruction of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.{{ubl | |||

| |Count 2: "use of a weapon of mass destruction" in violation of 18 USC § 2332a (2)(a) & (b). | |||

| |Count 3: "destruction by explosives resulting in death", in violation of 18 USC § 844(f)(2)(a) & (b). | |||

| |Counts 4–11: first-degree murder in violation of 18 USC § 1111, 1114, & 2 and 28 CFR § 64.2(h), each count in connection to one of the eight law enforcement officers who were killed during the attack.}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=FindLaw's United States Tenth Circuit case and opinions.|url=https://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-10th-circuit/1029918.html|access-date=2022-02-14|website=Findlaw}}</ref> On February 20, 1996, the Court granted a ] and ordered that the case be transferred from ] to the District Court in ], to be presided over by District Judge ].<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/longterm/oklahoma/stories/judge.htm|title=Richard Matsch Has a Firm Grip on His Gavel in the Oklahoma City Bombing Trial|last=Romano|first=Lois|date=May 12, 1997|work=National Special Report: Oklahoma Bombing Trial|publisher=Washington Post|access-date=April 15, 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101030062230/http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/longterm/oklahoma/stories/judge.htm|archive-date=2010-10-30|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| McVeigh instructed his lawyers to use a ], but they ended up not doing so.<ref>{{cite news|url = http://edition.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0106/09/pitn.00.html|work = CNN|date = February 7, 2001|access-date = May 25, 2010|title = People In The News|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20100423133457/http://edition.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0106/09/pitn.00.html |archive-date = 2010-04-23|url-status = live|df = mdy-all}}</ref> They would have had to prove that McVeigh was in "imminent danger" from the government. McVeigh argued that "imminent" did not necessarily mean "immediate". They would have argued that his bombing of the Murrah building was a justifiable response to what McVeigh believed were the crimes of the U.S. government at ], where the 51-day siege of the ] complex resulted in the deaths of 76 Branch Davidians.<ref>Linder, Douglas O., {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110223000407/http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/mcveigh/mcveighaccount.html |date=2011-02-23 }}, online posting, ], Law School faculty projects, 2006, accessed August 7, 2006.</ref> As part of the defense, McVeigh's lawyers showed the jury the controversial video '']''.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://edition.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0106/09/pitn.00.html|title=CNN.com – Transcripts|website=edition.cnn.com}}</ref> | |||

| On June 2, 1997, McVeigh was found guilty on all 11 counts of the federal indictment.<ref>Eddy, Mark; Lane, George; Pankratz, Howard; Wilmsen, Steven {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071001000254/http://extras.denverpost.com/bomb/bombv1.htm |date=2007-10-01 }} ''Denver Post'' June 3, 1997, accessed August 7, 2006</ref> Although 168 people, including 19 children, were killed in the April 19, 1995, bombing, murder charges were brought against McVeigh for only the eight federal agents who were on duty when the bomb destroyed much of the Murrah Building. Along with the eight counts of murder, McVeigh was charged with conspiracy to use a weapon of mass destruction, and destroying a federal building. Oklahoma City District Attorney Bob Macy said he would file state charges in the other 160 murders after McVeigh's co-defendant, Terry Nichols, was tried. After the verdict, McVeigh tried to calm his mother by saying, "Think of it this way. When I was in the Army, you didn't see me for years. Think of me that way now, like I'm away in the Army again, on an assignment for the military."<ref>Michel, Herbeck (200) p. 347</ref> | |||

| On June 13, the jury recommended that McVeigh receive the death penalty.<ref>{{cite news|title = McVeigh sentenced to die for Oklahoma City bombing|url = http://edition.cnn.com/US/9706/13/mcveigh.sentencing|agency = ]|date = 1997-06-13|access-date = 2020-07-04|df = mdy-all|archive-date = 2020-11-11|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20201111174728/http://edition.cnn.com/US/9706/13/mcveigh.sentencing/|url-status = dead}}</ref> The U.S. Department of Justice brought federal charges against McVeigh for causing the deaths of eight federal officers leading to a possible death penalty for McVeigh; they could not bring charges against McVeigh for the remaining 160 deaths in federal court because those deaths fell under the jurisdiction of the State of Oklahoma. Because McVeigh was convicted and sentenced to death, the State of Oklahoma did not file murder charges against McVeigh for the other 160 deaths.<ref>'' {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070313110452/http://edition.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0106/09/pitn.00.html |date=2007-03-13 }}'', transcript of program broadcast on ], June 9, 2001, 11:30 p.m. ET.</ref> Before the sentence was formally pronounced by Judge Matsch, McVeigh addressed the court for the first time and said: "If the Court please, I wish to use the words of Justice ] dissenting in '']'' to speak for me. He wrote, 'Our Government is the potent, the omnipresent teacher. For good or for ill, it teaches the whole people by its example.' That's all I have."<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1997-aug-15-mn-22602-story.html|title=McVeigh Speaks Out, Receives Death Sentence|last=Serrano|first=Richard A.|date=August 15, 1997|work=Los Angeles Times|access-date=November 18, 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141221131355/http://articles.latimes.com/1997/aug/15/news/mn-22602|archive-date=2014-12-21|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| == Incarceration and execution == | |||

| ] in Colorado until 1999.]] | |||

| McVeigh's death sentence was delayed pending an appeal. One of his appeals for {{lang|la|]}}, taken to the ], was denied on March 8, 1999. McVeigh's request for a nationally televised execution was also denied. Entertainment Network Inc., an Internet company that produces adult-themed websites, unsuccessfully sued for the right to broadcast the execution.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://archives.cnn.com/2001/LAW/04/05/mcveigh.internet/index.html |last=Williams |first=Dave |title=Internet firm sues to broadcast McVeigh execution |date=April 5, 2001 |publisher=CNN |access-date=April 12, 2010 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091010163946/http://archives.cnn.com/2001/LAW/04/05/mcveigh.internet/index.html |archive-date=October 10, 2009 }}</ref><ref name="Mieszkowski and Standen">{{cite news| url=https://www.salon.com/2001/04/19/mcveigh_6/ | title=The execution will not be webcast | date=19 April 2001 | access-date=July 28, 2011 | last1=Mieszkowski | first1=Katharine |last2=Standen, Amy | work=] | author-link1=Katharine Mieszkowski| author-link2 = Amy Standen}}</ref> At ], McVeigh and Nichols were housed in what was known as "bomber's row". ], ], and ] were also housed in this cell block. Yousef made frequent, unsuccessful attempts to convert McVeigh to ].<ref>Michel, Herbeck (2002) pp. 360–361.</ref> | |||

| The day before his execution, McVeigh said in a letter to '']'': "I am sorry these people had to lose their lives, but that's the nature of the beast. It's understood going in what the human toll will be."<ref name=usa4>{{cite news | url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2001/jun/11/mcveigh.usa4 | work=The Guardian | location=London | title=McVeigh faces day of reckoning | last=Borger | first=Julian | date=June 11, 2001 | access-date=May 25, 2010 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130825034934/http://www.theguardian.com/world/2001/jun/11/mcveigh.usa4 | archive-date=2013-08-25 | url-status=live }}</ref> He said that if there turned out to be an afterlife, he would "]",<ref name=usa4/> noting: "If there is a hell, then I'll be in good company with a lot of fighter pilots who also had to bomb innocents to win the war."<ref>{{cite news | url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2001/apr/22/mcveigh.usa | work=The Guardian | location=London | title=Dead man talking | date=May 9, 2001 | access-date=March 28, 2010 | first=Tracey | last=McVeigh | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130825010718/http://www.theguardian.com/world/2001/apr/22/mcveigh.usa | archive-date=2013-08-25 | url-status=live }}</ref> He also said: "I knew I wanted this before it happened. I knew my objective was state-assisted suicide and when it happens, it's in your face. You just did something you're trying to say should be illegal for medical personnel."<ref name="Mieszkowski and Standen"/> | |||

| The ] (BOP) transferred McVeigh from USP Florence ADMAX to the federal death row at ] in ], in 1999.<ref>Huppke, Rex W. "". '']'', April 6, 2001. p. 2A (continued from 1A). ]. Retrieved from ] (2/16) on October 14, 2010. "The planning for this day began when McVeigh was moved to the U.S. Penitentiary in Terre Haute, Indiana along with the 19 other federal death row inmates in 1999"</ref> McVeigh dropped his remaining appeals, saying that he would rather die than spend the rest of his life in prison.<ref name="BushdelaynecCCN">{{cite news|url=http://archives.cnn.com/2001/LAW/05/11/mcveigh.evidence.06/index.html |title=Bush calls McVeigh execution delay necessary |date=May 11, 2001 |publisher=CNN |access-date=April 12, 2010 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100614074106/http://archives.cnn.com/2001/LAW/05/11/mcveigh.evidence.06/index.html |archive-date=June 14, 2010 }}</ref> On January 16, 2001, the BOP set May 16 as McVeigh's execution date.<ref>"" ({{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100527205424/http://www.bop.gov/news/press/press_releases/ipapr009.jsp |date=2010-05-27 }}). ]. January 16, 2001. Retrieved May 29, 2010.</ref> McVeigh said that his only regret was not completely destroying the federal building.<ref>{{cite news | url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2001/mar/30/julianborger | work=The Guardian | location=London | title=McVeigh brushes aside deaths | first=Julian | last=Borger | date=March 30, 2001 | access-date=May 25, 2010 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130825001819/http://www.theguardian.com/world/2001/mar/30/julianborger | archive-date=2013-08-25 | url-status=live }}</ref> Six days prior to his scheduled execution, the FBI turned over thousands of documents of evidence it had previously withheld to McVeigh's attorneys. As a result, U.S. Attorney General ] announced McVeigh's execution would be stayed for one month.<ref name="BushdelaynecCCN"/> The execution date was reset for June 11. Conductor ] performed ] for McVeigh on the morning of McVeigh's execution.<ref>{{Cite news |date=2001-05-11 |title=Composer creates McVeigh death fanfare |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/1324743.stm |access-date=2024-12-02 |language=en-GB}}</ref> While acknowledging McVeigh's "horrible deed", David Woodard intended to "provide comfort".<ref>Siletti, M. J., , doctoral dissertation under Prof. J. Magee, ], 2018, pp. 240–241.</ref><ref>], ''Gesichter Amerikas: Reportagen aus dem Land der unbegrenzten Widersprüche'' (]: Henselowsky Boschmann Verlag, 2006), p. 30.</ref> McVeigh also requested a Catholic chaplain. His ] consisted of two ]s of ] ice cream.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.lastmealsproject.com/pages.html |title=index |publisher=Lastmealsproject.com |access-date=2014-08-18 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140821061756/http://www.lastmealsproject.com/pages.html |archive-date=2014-08-21 }}</ref> | |||

| ] in Indiana after 1999.]] | |||

| McVeigh chose ]'s 1875 poem "]" as his final written statement.<ref>{{cite news|title=Execution of an American Terrorist|work=Court TV|last=Quayle|first=Catherine|date=June 11, 2001|url=http://www.cnn.com/2007/US/law/12/17/court.archive.mcveigh5/index.html#cnnSTCText|access-date=2011-08-24|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121110123256/http://www.cnn.com/2007/US/law/12/17/court.archive.mcveigh5/index.html#cnnSTCText|archive-date=2012-11-10|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|title=Timothy McVeigh Put to Death for Oklahoma City Bombings |publisher=FOX News |last=Cosby|first=Rita|date=June 12, 2001|url=https://www.foxnews.com/story/timothy-mcveigh-put-to-death-for-oklahoma-city-bombings|access-date=April 15, 2008|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080413215719/http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,26904,00.html|archive-date=2008-04-13|url-status=live}}</ref> Just before the execution, when he was asked if he had a final statement, he declined. Jay Sawyer, a relative of one of the victims, wrote, "Without saying a word, he got the final word."<ref>{{cite news | url=http://edition.cnn.com/2007/US/law/12/17/court.archive.mcveigh/ | work=CNN | title=Terror on Trial: Timothy McVeigh executed | date=December 31, 2007 | access-date=September 25, 2020 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200423134709/http://edition.cnn.com/2007/US/law/12/17/court.archive.mcveigh/ | archive-date=2020-04-23 | url-status=live}}</ref> Larry Whicher, whose brother died in the attack, described McVeigh as having "a totally expressionless, blank stare. He had a look of defiance and that if he could, he'd do it all over again."<ref name="trutv11">{{cite web|url=http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/serial_killers/notorious/mcveigh/updates.html|title=Pre-Execution News: McVeigh's Stay Request Denied|date=June 7, 2001|last=Ottley|first=Ted|work=Timothy McVeigh & Terry Nichols: Oklahoma Bombing|publisher=TruTv|access-date=April 12, 2010|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110924155955/http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/serial_killers/notorious/mcveigh/updates.html|archive-date=September 24, 2011}}</ref> McVeigh was executed by ] at 7:14 a.m. on June 11, 2001, the first person to be executed by the United States federal government since ] was executed in Iowa on March 15, 1963.<ref>{{cite news |title=McVeigh's final hours recall last federal execution |url=https://www.nzherald.co.nz/world/mcveighs-final-hours-recall-last-federal-execution/LW6ULI5OBLMDVDK7SWCKW4CWLQ/ |access-date=21 February 2021 |work=] |date=10 June 2001}}</ref> | |||

| On November 21, 1997, President ] had signed S. 923, special legislation introduced by Senator ] to bar McVeigh and other veterans convicted of capital crimes from being buried in any military cemetery.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3655/is_199904/ai_n8846061/pg_43 |archive-url=http://arquivo.pt/wayback/20091001091455/http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3655/is_199904/ai_n8846061/pg_43 |url-status=dead |archive-date=2009-10-01 |title=Fair notice, even for terrorists: Timothy McVeigh and a new standard for the ex post facto clause |date=Spring 1999 |publisher=Washington and Lee Law Review |last=Gottman |first=Andrew J |access-date=April 12, 2010 }}</ref><ref>{{USStatute|105|116|111|2381|1997|11|21|S|923}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://commdocs.house.gov/committees/vets/hvr070997.000/hvr070997_0.htm|title=Hearing on S. 923 and H.R. 2040, to deny burial in a federally funded cemetery and other benefits to veterans convicted of certain capital crimes|publisher=U.S. House of Representatives|date=July 9, 1997|access-date=October 24, 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101103203356/http://commdocs.house.gov/committees/vets/hvr070997.000/hvr070997_0.htm|archive-date=2010-11-03|url-status=live}}</ref> His body was cremated at Mattox Ryan Funeral Home in Terre Haute. His ashes were given to his lawyer, who said "the final destination of McVeigh's remains would remain privileged forever."<ref name="mcveigh_dead"/> McVeigh had written that he considered having them dropped at the site of the memorial where the building once stood, but decided that would be "too vengeful, too raw, too cold."<ref name="mcveigh_dead">{{cite web|title=Timothy McVeigh dead|url=http://edition.cnn.com/2001/LAW/06/11/mcveigh.01/|publisher=CNN|access-date=July 30, 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160101191824/http://edition.cnn.com/2001/LAW/06/11/mcveigh.01/|archive-date=2016-01-01|url-status=live}}</ref> He had expressed willingness to donate organs, but was prohibited from doing so by prison regulations.<ref name=Oklahoman/> Psychiatrist John Smith concluded that McVeigh was "a decent person who had allowed rage to build up inside him to the point that he had lashed out in one terrible, violent act."<ref name=bbcprofile/> McVeigh's ] was assessed at 126.<ref>Michel, Herbeck 2002 p. 288.</ref> | |||

| ==Associations== | |||

| According to ], his only known associations were as a registered ] while in ], in the 1980s, and a membership in the ] while in the Army. | |||

| After returning home from war he signed up for a trial membership in the ], although he did not ultimately continue with the Klan.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Terror on Trial: Who was Timothy McVeigh? - CNN.com |url=https://www.cnn.com/2007/US/law/12/17/court.archive.mcveigh2/index.html |access-date=2023-01-11 |website=www.cnn.com}}</ref> There is no conclusive evidence that he ever belonged to any other extremist groups.<ref name="Profile of Timothy McVeigh">Profile of , {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060209045752/http://archives.cnn.com/2001/US/03/29/profile.mcveigh/|date=2006-02-09}} ], March 29, 2001. Retrieved February 22, 2015.</ref> | |||

| ==Religious beliefs== | |||

| McVeigh was raised ].<ref name="pcoletime">Patrick Cole, , March 30, 1996. Retrieved October 19, 2010. </ref> During his childhood, he and his father attended ] regularly.<ref>{{cite news | first=Robert D. | last=McFadden | title=Terror in Oklahoma: The Suspect; One Man's Complex Path to Extremism | work=] | url=https://www.nytimes.com/1995/04/23/us/terror-in-oklahoma-the-suspect-one-man-s-complex-path-to-extremism.html?pagewanted=2 | date=April 23, 1995 | access-date=March 23, 2011 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130516204332/http://www.nytimes.com/1995/04/23/us/terror-in-oklahoma-the-suspect-one-man-s-complex-path-to-extremism.html?pagewanted=2 | archive-date=2013-05-16 | url-status=live }}</ref> McVeigh was ] at the Good Shepherd Church in Pendleton, New York, in 1985.<ref>{{cite news | title=Fellow inmate counsels McVeigh | agency=Associated Press | url=https://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2001-05-07-mcveigh-fellow.htm | access-date=March 23, 2011 | date=June 20, 2001 | work=USA Today | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20030610003212/http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2001-05-07-mcveigh-fellow.htm | archive-date=2003-06-10 | url-status=live }}</ref> In a 1996 interview, McVeigh professed belief in "a God", although he said he had "sort of lost touch with" Catholicism and "I never really picked it up, however I do maintain core beliefs."<ref name = "pcoletime" /> In McVeigh's biography ''American Terrorist'', released in 2002, he stated that he did not believe in a ] and that science is his religion.<ref>" " ] Show, aired April 19, 2010, pt. 1 at 2 min. 40 sec.</ref><ref>Michel, Herbeck 2002 pp. 142-143</ref> In June 2001, a day before the execution, McVeigh wrote a letter to the ''Buffalo News'' identifying himself as ].<ref name="Borger">Julian Borger, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161201174919/https://www.theguardian.com/world/2001/jun/11/mcveigh.usa4 |date=2016-12-01 }}, '']'', June 11, 2001. Retrieved October 19, 2010.</ref> However, he took the ], administered by a priest, just before his execution.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.toledoblade.com/Religion/2001/06/17/Salvation-for-a-killer.html |work=The Blade|title= Salvation for a killer?|author=David Yonke|access-date=2014-12-01 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141225225445/http://www.toledoblade.com/Religion/2001/06/17/Salvation-for-a-killer.html |archive-date=2014-12-25 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151127093817/http://edition.cnn.com/2001/LAW/06/11/mcveigh.03/index.html |date=2015-11-27 }}, ], April 10, 2001. Retrieved 7 October 2015.</ref> Father Charles Smith ministered to McVeigh in his last moments on death row.<ref>{{Cite news |title=Oklahoma Bomber Confessed to Catholic Priest|work=]|date=August 18, 2006}}</ref> | |||

| ==Motivations for the bombing== | |||

| McVeigh claimed that the bombing was revenge against the government for the sieges at Waco and Ruby Ridge.<ref>See "McVeigh Remorseless About Bombing," newswire release, ], March 29, 2001.</ref> McVeigh visited Waco during the standoff. While there, he was interviewed by student reporter Michelle Rauch, a senior journalism major at ] who was writing for the school paper. McVeigh expressed his objections over what was happening there.<ref name="Profile of Timothy McVeigh"/><ref name="Rauch's Waco testimony">{{cite news|url=http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/mcveigh/mcveighwaco.html|title=Timothy McVeigh in Waco|publisher=UMKC.edu|access-date=August 14, 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121007233508/http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/mcveigh/mcveighwaco.html|archive-date=2012-10-07|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| McVeigh frequently quoted and alluded to the white supremacist novel '']''; he claimed to appreciate its interest in firearms. Photocopies of pages sixty-one and sixty-two of ''The Turner Diaries'' were found in an envelope inside McVeigh's car. These pages depicted a fictitious mortar attack upon the ] in Washington.<ref>Michel and Herbeck; cf. Walsh.</ref> | |||