| Revision as of 22:39, 22 May 2006 view source67.23.204.163 (talk) →Background← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 04:01, 24 December 2024 view source A68-n (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users635 editsmNo edit summaryTag: Visual edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|War in Southeast Asia from 1955 to 1975}} | |||

| {{Infobox Military Conflict | |||

| {{redirect|Second Indochina War|the war between India and China|Nathu La and Cho La clashes}} | |||

| |conflict=Vietnam War | |||

| {{For-multi|a full history of wars in Vietnam|List of wars involving Vietnam|the documentary television series|The Vietnam War (TV series){{!}}''The Vietnam War'' (TV series)}} | |||

| |partof=the ] | |||

| {{pp-extended|small=yes}} | |||

| |image=] | |||

| |caption=<small>Vietnamese base camp after an attack.<small> | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=November 2022}}{{Use American English|date=December 2023}} | |||

| |date=]–] | |||

| |place=] | |||

| {{very long|date=November 2024}} | |||

| |casus=] escalation | |||

| |territory= | |||

| {{Infobox military conflict | |||

| |result= | |||

| | conflict = Vietnam War | |||

| Peace treaty providing for U.S. disengagement in 1973.<BR> | |||

| | partof = the ] and the ] | |||

| Military victory by North Vietnam over South Vietnamese forces in 1975.<BR> | |||

| | image = {{multiple image|border=infobox|perrow=2/2/2|total_width=300 | |||

| Unification of Vietnam | |||

| | image1=U.S. Army UH-1H Hueys insert ARVN troops at Khâm Đức, Vietnam, 12 July 1970 (79431435).jpg | |||

| |combatant1=]<br>]<br>]<br>]<br>]<br>]<br>the ] | |||

| | image2=Pavnbattle.jpg | |||

| |combatant2=]<br>] | |||

| | image3=Hue Massacre Interment.jpg | |||

| |commander1= | |||

| | image4=Flame Thrower. Operation New Castle. - NARA - 532488.tif | |||

| |commander2= | |||

| | image5=A-4E Skyhawk of VA-56 drops bomb over Vietnam c1966.jpg | |||

| |strength1=~1,200,000 (1968) | |||

| | image6=Saigon Execution (cropped).jpg | |||

| |strength2=~420,000 (1968) | |||

| }}'''Clockwise from top left:''' {{flatlist| | |||

| |casualties1=South Vietnamese dead: 230,000<br>South Vietnamese wounded: 300,000<br>US dead: 58,191<br>US wounded: 153,303<br>Australian Dead: 500<br>South Korean dead: 5,000<br>South Korean wounded: 11,000<br>Civilian (total Vietnamese): c. 2–4 million | |||

| * US ] helicopters inserting South Vietnamese ] troops, 1970 | |||

| |casualties2=Dead: 1,100,000<br>Wounded: 600,000 <br> Chinese dead: 1100<br> Chinese wounded: 4200<br>Civilian (total Vietnamese): c. 2–4 million | |||

| * North Vietnamese ] troops in action, {{circa|1966}} | |||

| * ] using a ], 1967 | |||

| * South Vietnamese officer ] a ] officer during the ], 1968 | |||

| * US Navy ] on a bombing run, 1966 | |||

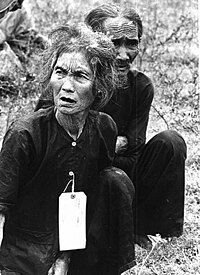

| * Burial of civilians killed in the ], 1968 | |||

| }} | |||

| | date = 1 November 1955<ref group=A name="start date" />{{snd}}30 April 1975<br />({{Age in years, months, and days|month1=11|day1=1|year1=1955|month2=04|day2=30|year2=1975}}) | |||

| | place = {{flatlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] (spillover conflict in ], and ])}} | |||

| | territory = Reunification of ] and ] into the ] in 1976 | |||

| | result = ]ese victory | |||

| | combatant2 = {{Plainlist}} | |||

| * {{Flag|South Vietnam}} | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|United States|1960}} ] | |||

| * {{Flagcountry|Third Republic of Korea}} | |||

| * {{Flag|Australia}} | |||

| * {{Flag|New Zealand}} | |||

| * {{Flag|Kingdom of Laos|name=Laos}} | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|Cambodia}} ] (1967–1970) | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|Cambodia|1970}} ] (1970–1975) | |||

| * {{Flag|Thailand|1932}} | |||

| * {{Flagcountry|Fourth Philippine Republic}} | |||

| * {{Flag|Taiwan}} | |||

| {{Endplainlist}} | |||

| | combatant1 = {{Plainlist}} | |||

| * {{Flag|North Vietnam}} | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|Republic of South Vietnam}} ] and ] | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|Laos}} ] | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|Cambodia|1975}} ] | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|Cambodia|1973}} ] (1970–1975) | |||

| * {{Flag|China}} (1965–1973) | |||

| * {{Flag|Soviet Union|1955}} | |||

| * {{Flag|North Korea|1948}} | |||

| {{Endplainlist}} | |||

| | strength1 = '''≈860,000 (1967)''' | |||

| {{Plainlist}} | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|North Vietnam}} '''North Vietnam:'''<br />690,000 (1966, including ] and Viet Cong){{Refn|group="A"|According to Hanoi's official history, the Viet Cong was a branch of the People's Army of Vietnam.<ref>{{Harvnb|Military History Institute of Vietnam|2002|p=182}}. "By the end of 1966 the total strength of our armed forces was 690,000 soldiers."</ref>}} | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|Republic of South Vietnam}} '''Viet Cong:'''<br />{{Nowrap|~200,000 (estimated, 1968)}}<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Doyle |first1=Edward |title=The Vietnam Experience The North |last2=Lipsman |first2=Samuel |last3=Maitland |first3=Terence |publisher=Time Life Education |year=1986 |isbn=978-0-939526-21-5 |pages=45–49}}</ref> | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|China|1949}} '''China:'''<br />170,000 (1968)<br />320,000 total<ref name="Toledo Blade 320,000 Chinese troops">{{Cite news |date=16 May 1989 |title=China admits 320,000 troops fought in Vietnam |work=Toledo Blade |agency=Reuters |url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1350&dat=19890516&id=HkRPAAAAIBAJ&pg=3769,1925460 |access-date=24 December 2013 |archive-date=2 July 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200702034430/https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1350&dat=19890516&id=HkRPAAAAIBAJ&pg=3769,1925460 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Roy">{{Cite book |last=Roy |first=Denny |url=https://archive.org/details/chinasforeignrel0000royd/page/27 |title=China's Foreign Relations |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |year=1998 |isbn=978-0-8476-9013-8 |page=}}</ref><ref name="Womack">{{Cite book |last=Womack |first=Brantly |title=China and Vietnam |year=2006 |isbn=978-0-521-61834-2 |page=|publisher=Cambridge University Press }}</ref> | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|Cambodia|1975}} '''Khmer Rouge:'''<br />70,000 (1972)<ref name="Tucker">{{Cite book |last=Tucker |first=Spencer C |title=The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social, and Military History |publisher=ABC-CLIO |year=2011 |isbn=978-1-85109-960-3}}</ref>{{Rp|376}} | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|Laos}} '''Pathet Lao:'''<br />48,000 (1970)<ref>{{Cite web |title=Area Handbook Series Laos |url=http://www.country-data.com/frd/cs/laos/la_glos.html#Lao |access-date=1 November 2019 |archive-date=7 March 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160307033933/http://www.country-data.com/frd/cs/laos/la_glos.html#Lao |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|Soviet Union}} '''Soviet Union:''' ~3,000<ref>{{Cite book |last=O'Ballance |first=Edgar |title=Tracks of the bear: Soviet imprints in the seventies |publisher=Presidio |year=1982 |isbn=978-0-89141-133-8 |page=171}}</ref> | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|North Korea|1948}} '''North Korea:''' 200<ref>{{Cite news |last=Pham Thi Thu Thuy |date=1 August 2013 |title=The colorful history of North Korea-Vietnam relations |work=] |url=https://www.nknews.org/2013/08/the-colorful-history-of-north-korea-vietnam-relations/ |access-date=3 October 2016|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150424055821/http://www.nknews.org/2013/08/the-colorful-history-of-north-korea-vietnam-relations/|archive-date=April 24, 2015}}</ref> | |||

| {{Endplainlist}} | |||

| | strength2 = '''≈1,420,000 (1968)''' | |||

| {{Plainlist}} | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|South Vietnam}} '''South Vietnam:'''<br />850,000 (1968)<br />1,500,000 (1974–1975)<ref>{{Cite book |last=Le Gro |first=William |url=https://history.army.mil/html/books/090/90-29/CMH_Pub_90-29.pdf |title=Vietnam from ceasefire to capitulation |publisher=US Army Center of Military History |year=1985 |isbn=978-1-4102-2542-9 |page=28|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230202012033/https://history.army.mil/html/books/090/90-29/CMH_Pub_90-29.pdf|archive-date=February 2, 2023}}</ref> | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|United States|1960}} '''United States:'''<br />2,709,918 serving in Vietnam total<br />Peak: 543,000 (April 1969)<ref name=Tucker/>{{Rp|xlv}} | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|Cambodia|1970}} '''Khmer Republic:'''<br />200,000 (1973){{Citation needed|date=November 2022}} | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|Laos|1952}} '''Laos:'''<br />72,000 (Royal Army and ] militia)<ref>{{Cite web |title=The rise of Communism |url=http://www.footprinttravelguides.com/c/4999/the-rise-of-communism |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101117114707/http://footprinttravelguides.com/c/4999/the-rise-of-communism/ |archive-date=17 November 2010 |access-date=31 May 2018 |website=www.footprinttravelguides.com}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Hmong rebellion in Laos |url=http://members.ozemail.com.au/~yeulee/Topical/Hmong%20rebellion%20in%20Laos.html |access-date=11 April 2021 |website=Members.ozemail.com.au|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230404230156/http://members.ozemail.com.au/~yeulee/Topical/Hmong%20rebellion%20in%20Laos.html|archive-date=April 4, 2023}}</ref> | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|Third Republic of Korea}} '''South Korea:'''<br />48,000 per year (1965–1973, 320,000 total) | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|Thailand|1939}} '''Thailand:''' 32,000 per year (1965–1973)<br />(in Vietnam<ref>{{Cite web |title=Vietnam War Allied Troop Levels 1960–73 |url=http://www.americanwarlibrary.com/vietnam/vwatl.htm |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160802134052/http://www.americanwarlibrary.com/vietnam/vwatl.htm |archive-date=2 August 2016 |access-date=2 August 2016}}, accessed 7 November 2017</ref> and Laos){{Citation needed|date=November 2022}} | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|Australia}} '''Australia:''' 50,190 total<br />(Peak: 8,300 combat troops)<ref>{{Cite web |last1=Doyle |first1=Jeff |last2=Grey |first2=Jeffrey |last3=Pierce |first3=Peter |date=2002 |title=Australia's Vietnam War – A Select Chronology of Australian Involvement in the Vietnam War |url=https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/14206/3/14206_Doyle_et_al_2002_Back_Pages.pdf |publisher=]|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20221110165929/https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/14206/3/14206_Doyle_et_al_2002_Back_Pages.pdf|archive-date=November 10, 2022}}</ref> | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|New Zealand}} '''New Zealand:''' Peak: 552 in 1968<ref name=Blackburn>{{cite book|last=Blackburn|first=Robert M.|title=Mercenaries and Lyndon Johnson's "More Flage": The Hiring of Korean, Filipino, and Thai Soldiers in the Vietnam War|publisher=McFarland|year=1994|isbn=0-89950-931-2}}</ref>{{rp|158}} | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|Fourth Philippine Republic}} '''Philippines:''' 2,061 | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|Francoist Spain}} '''Spain:''' 100–130 total<br />(Peak: 30 medical troops and advisors)<ref>{{Cite news| url=https://elpais.com/elpais/2012/04/09/inenglish/1333979983_253264.html| title=Spain's secret support for US in Vietnam| newspaper=El País| date=2012-04-09| last1=Marín| first1=Paloma| access-date=18 February 2024| archive-date=4 November 2019| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191104193117/https://elpais.com/elpais/2012/04/09/inenglish/1333979983_253264.html| url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| {{Endplainlist}} | |||

| | commander1 = {{Plainlist}} | |||

| * {{Flagicon|North Vietnam}} ] | |||

| * {{Flagicon|North Vietnam}} ] | |||

| * {{Flagicon|North Vietnam}} ] | |||

| * {{Flagicon|North Vietnam}} ] | |||

| * {{Flagicon|North Vietnam}} ] | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|South Vietnam|1975}} ] | |||

| * ''...{{Nbsp}}]'' | |||

| {{Endplainlist}} | |||

| | commander2 = {{Plainlist}} | |||

| * {{Flagicon|South Vietnam}} ]{{Assassinated|Arrest and assassination of Ngo Dinh Diem}} {{Refn|1955–1963| group="A"}} | |||

| * {{Flagicon|South Vietnam}} ] | |||

| * {{Flagicon|South Vietnam}} ] | |||

| * {{Flagicon|US|1960}} ] | |||

| * {{Flagicon|US|1960}} ] ''']''' | |||

| * {{Flagicon|US|1960}} ]{{Refn|1963–1969| group="A"}} | |||

| * {{Flagicon|US|1960}} ] | |||

| * {{Flagicon|US|1960}} ] | |||

| * {{flagicon|US|1960}} ] | |||

| * {{Nowrap|{{Flagicon|US|1960}} ]}}{{Refn|1964–1968| group="A"}} | |||

| * {{Flagicon|US|1960}} ] | |||

| * ''...{{Nbsp}}]'' | |||

| {{Endplainlist}} | |||

| | casualties1 = {{Plainlist}} | |||

| * {{Flagdeco|North Vietnam}}{{Flagdeco|Republic of South Vietnam}} '''North Vietnam & Viet Cong'''<br />30,000–182,000 civilian dead<ref name=Tucker/>{{Rp|176}}<ref name="Hirschman">{{Cite journal |last1=Hirschman |first1=Charles |last2=Preston |first2=Samuel |last3=Vu |first3=Manh Loi |date=December 1995 |title=Vietnamese Casualties During the American War: A New Estimate |url=http://faculty.washington.edu/charles/new%20PUBS/A77.pdf |journal=] |volume=21 |issue=4 |page=783 |doi=10.2307/2137774 |jstor=2137774 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20131012055340/http://faculty.washington.edu/charles/new%20PUBS/A77.pdf|archive-date=October 12, 2013 |issn=0098-7921 }}</ref><ref name=Lewy/>{{Rp|450–453}}<ref name=bfvietnam>{{Cite web |title=Battlefield:Vietnam – Timeline |url=http://www.pbs.org/battlefieldvietnam/timeline/index2.html |publisher=]|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230604101618/http://www.pbs.org/battlefieldvietnam/timeline/index2.html|archive-date=June 4, 2023}}</ref><br />849,018 military dead (per Vietnam; 1/3 non-combat deaths)<ref name="Moyar, Mark" /><ref name="Chuyen">{{Cite web |title=Chuyên đề 4 CÔNG TÁC TÌM KIẾM, QUY TẬP HÀI CỐT LIỆT SĨ TỪ NAY ĐẾN NĂM 2020 VÀ NHỮNG NĂM TIẾP THEO |url=http://datafile.chinhsachquandoi.gov.vn/Qu%E1%BA%A3n%20l%C3%BD%20ch%E1%BB%89%20%C4%91%E1%BA%A1o/Chuy%C3%AAn%20%C4%91%E1%BB%81%204.doc |access-date=11 April 2021 |website=Datafile.chinhsachquandoi.gov.vn|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230404230151/http://datafile.chinhsachquandoi.gov.vn/Qu%E1%BA%A3n%20l%C3%BD%20ch%E1%BB%89%20%C4%91%E1%BA%A1o/Chuy%C3%AAn%20%C4%91%E1%BB%81%204.doc|archive-date=April 4, 2023}}</ref><ref name="VNMOD">{{Cite web |title=Công tác tìm kiếm, quy tập hài cốt liệt sĩ từ nay đến năm 2020 và những năn tiếp theo |trans-title=The work of searching and collecting the remains of martyrs from now to 2020 and the next |url=http://chinhsachquandoi.gov.vn/tinbai/309/Tap-huan-cong-tac-chinh-sach |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181217065036/http://chinhsachquandoi.gov.vn/tinbai/309/Tap-huan-cong-tac-chinh-sach |archive-date=17 December 2018 |access-date=11 June 2018 |publisher=], Government of Vietnam |language=vi}}</ref><br />666,000–950,765 dead<br />(US estimated 1964–1974){{Refn|Upper figure initial estimate, later thought to be inflated by at least 30% (lower figure)<ref name=Hirschman/><ref name=Lewy/>{{Rp|450–453}}|name=USclaim|group=A}}<ref name=Hirschman/><ref name=Lewy/>{{Rp|450–451}}<br />232,000+ military missing (per Vietnam)<ref name="Moyar, Mark">Moyar, Mark. "Triumph Regained: The Vietnam War, 1965–1968." Encounter Books, December 2022. Chapter 17 index: "Communists provided further corroboration of the proximity of their casualty figures to American figures in a postwar disclosure of total losses from 1960 to 1975. During that period, they stated, they lost 849,018 killed plus approximately 232,000 missing and 463,000 wounded. Casualties fluctuated considerably from year to year, but a degree of accuracy can be inferred from the fact that 500,000 was 59 percent of the 849,018 total and that 59 percent of the war's days had passed by the time of Fallaci's conversation with Giap. The killed in action figure comes from "Special Subject 4: The Work of Locating and Recovering the Remains of Martyrs From Now Until 2020 And Later Years," downloaded from the Vietnamese government website datafile on 1 December 2017. The above figures on missing and wounded were calculated using Hanoi's declared casualty ratios for the period of 1945 to 1979, during which time the Communists incurred 1.1 million killed, 300,000 missing, and 600,000 wounded. Ho Khang, ed, ''Lich Su Khang Chien Chong My, Cuu Nuoc 1954–1975, Tap VIII: Toan Thang'' (Hanoi: Nha Xuat Ban Chinh Tri Quoc Gia, 2008), 463."</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Joseph Babcock |date=29 April 2019 |title=Lost Souls: The Search for Vietnam's 300,000 or More MIAs |url=https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/lost-souls-search-vietnams-300000-or-more-mias |access-date=28 June 2021 |website=Pulitzer Centre|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20221110165934/https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/lost-souls-search-vietnams-300000-or-more-mias|archive-date=November 10, 2022}}</ref><br />600,000+ military wounded<ref name="Hastings">{{Cite book |last=Hastings |first=Max |title=Vietnam an epic tragedy, 1945–1975 |publisher=Harper Collins |year=2018 |isbn=978-0-06-240567-8}}</ref>{{Rp|739}} | |||

| * '''{{Flagdeco|Cambodia|1975}}''' '''Khmer Rouge:''' Unknown | |||

| * '''{{Flagicon|Laos}}''' '''Pathet Lao:''' Unknown | |||

| * '''{{Flagu|China|1949}}:''' ~1,100 dead and 4,200 wounded<ref name=Womack/> | |||

| * '''{{Flagu|Soviet Union}}:''' 16 dead<ref>{{Cite book |last1=James F. Dunnigan |title=Dirty Little Secrets of the Vietnam War: Military Information You're Not Supposed to Know |last2=Albert A. Nofi |publisher=Macmillan |year=2000 |isbn=978-0-312-25282-3 |author-link2=Albert A. Nofi}}</ref> | |||

| * '''{{Flagu|North Korea|1948}}:''' 14 dead<ref>{{Cite news |date=31 March 2000 |title=North Korea fought in Vietnam War |work=] |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/696970.stm |access-date=18 October 2015|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230312063506/http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/696970.stm|archive-date=March 12, 2023}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/publication/NKIDP_eDossier_2_North_Korean_Pilots_in_Vietnam_War.pdf|title=North Korean Pilots in the Skies over Vietnam|last=Pribbenow|first=Merle|publisher=]|date=November 2011|access-date=3 March 2023|page=1|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230605173651/https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/publication/NKIDP_eDossier_2_North_Korean_Pilots_in_Vietnam_War.pdf|archive-date=June 5, 2023}}</ref> | |||

| '''Total military dead/missing:<br />≈1,100,000'''<br />'''Total military wounded:<br />≈604,200'''<br />(excluding ]/] and ]) | |||

| {{Endplainlist}} | |||

| | casualties2 = {{Plainlist}} | |||

| * '''{{Flagu|South Vietnam}}:'''<br />195,000–430,000 civilian dead<ref name=Hirschman/><ref name="Lewy">{{Cite book |last=Lewy |first=Guenter |title=America in Vietnam |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=1978 |isbn=978-0-19-987423-1 |author-link=Guenter Lewy}}</ref>{{Rp|450–453}}<ref name="Thayer">{{Cite book |last=Thayer |first=Thomas C. |title=War Without Fronts: The American Experience in Vietnam |publisher=Westview Press |year=1985 |isbn=978-0-8133-7132-0}}</ref>{{Rp|}}<br />Military dead: 313,000 (total)<ref name="Rummel">{{Citation |last=Rummel |first=R. J. |title=Vietnam Democide |loc=Table 6.1A |url=http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills/SOD.TAB6.1A.GIF |work=Freedom, Democracy, Peace; Power, Democide, and War, University of Hawaii System |year=1997 |format=GIF|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230313125242/http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills/SOD.TAB6.1A.GIF|archive-date=March 13, 2023}}</ref>{{Bulletedlist|254,256 combat deaths (between 1960 and 1974)<ref name="Clarke">{{Cite book |last=Clarke |first=Jeffrey J. |title=United States Army in Vietnam: Advice and Support: The Final Years, 1965–1973 |publisher=Center of Military History, United States Army |year=1988 |quote=The Army of the Republic of Vietnam suffered 254,256 recorded combat deaths between 1960 and 1974, with the highest number of recorded deaths being in 1972, with 39,587 combat deaths}}</ref>{{Rp|275}}}}<br />1,170,000 military wounded<ref name=Tucker/>{{Rp|}}<br />≈ 1,000,000 captured<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Fall of South Vietnam |url=https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/reports/2005/R2208.pdf |access-date=11 April 2021 |website=Rand.org|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230129192039/https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/reports/2005/R2208.pdf|archive-date=January 29, 2023}}</ref> | |||

| * '''{{Flagu|United States|1960}}:'''<br />58,281 dead<ref name="2new">{{Cite press release |title=2021 NAME ADDITIONS AND STATUS CHANGES ON THE VIETNAM VETERANS MEMORIAL |date=4 May 2021 |url=https://www.vvmf.org/News/2021-Name-Additions-and-Status-Changes-on-the-Vietnam-Veterans-Memorial/ |author=Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230429132111/https://www.vvmf.org/News/2021-Name-Additions-and-Status-Changes-on-the-Vietnam-Veterans-Memorial/|archive-date=April 29, 2023}}</ref> (47,434 from combat)<ref>{{Citation |title=National Archives–Vietnam War US Military Fatal Casualties |date=15 August 2016 |url=https://www.archives.gov/research/military/vietnam-war/casualty-statistics#hostile |access-date=29 July 2020 |archive-date=26 May 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200526173917/https://www.archives.gov/research/military/vietnam-war/casualty-statistics#hostile |url-status=live }}</ref><ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200526173917/https://www.archives.gov/research/military/vietnam-war/casualty-statistics#hostile |date=26 May 2020 }} US National Archives. 29 April 2008. Accessed 13 July 2019.</ref><br />303,644 wounded (including 150,341 not requiring hospital care)<ref name="USd&w" group="A" /> | |||

| * '''{{Flagu|Laos|1952}}:''' 15,000 army dead<ref>T. Lomperis, From People's War to People's Rule (1996)</ref> | |||

| * '''{{Flagdeco|Cambodia|1970}}''' '''Khmer Republic:''' Unknown | |||

| * '''{{Flagdeco|Third Republic of Korea}}''' '''South Korea''': 5,099 dead; 10,962 wounded; 4 missing | |||

| * '''{{Flagu|Australia}}:''' 521 dead; 3,129 wounded<ref>{{Cite web |title=Australian casualties in the Vietnam War, 1962–72 |url=http://www.awm.gov.au/encyclopedia/vietnam/statistics |access-date=29 June 2013 |publisher=Australian War Memorial|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230214111653/https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/encyclopedia/vietnam/statistics|archive-date=February 14, 2023}}</ref> | |||

| * '''{{Flagu|Thailand|1939}}:''' 351 dead<ref name=Tucker/>{{Rp|}} | |||

| * '''{{Flagu|New Zealand}}:''' 37 dead<ref>{{Cite web |date=16 July 1965 |title=Overview of the war in Vietnam |url=http://vietnamwar.govt.nz/resources |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130726010609/http://vietnamwar.govt.nz/resources |archive-date=26 July 2013 |access-date=29 June 2013 |publisher=New Zealand and the Vietnam War}}</ref> | |||

| * '''{{Flagu|Taiwan}}:''' 25 dead<ref>{{Cite web |date=2 October 2013 |title=America Wasn't the Only Foreign Power in the Vietnam War |url=http://militaryhistorynow.com/2013/10/02/the-international-vietnam-war-the-other-world-powers-that-fought-in-south-east-asia/ |access-date=10 June 2017|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230418045659/http://militaryhistorynow.com/2013/10/02/the-international-vietnam-war-the-other-world-powers-that-fought-in-south-east-asia/|archive-date=April 18, 2023}}</ref><br />17 captured<ref>{{Cite news |date=1964 |title=Vietnam Reds Said to Hold 17 From Taiwan as Spies |work=] |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1964/07/13/archives/vietnam-reds-said-to-hold-17-from-taiwan-as-spies.html|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230307170856/https://www.nytimes.com/1964/07/13/archives/vietnam-reds-said-to-hold-17-from-taiwan-as-spies.html|archive-date=March 7, 2023}}</ref> | |||

| * '''{{Flagdeco|Fourth Philippine Republic}}''' '''Philippines:''' 9 dead;<ref>{{Cite book |last=Larsen |first=Stanley |url=https://history.army.mil/html/books/090/90-5-1/CMH_Pub_90-5-1.pdf |title=Vietnam Studies Allied Participation in Vietnam |publisher=Department of the Army |year=1975 |isbn=978-1-5176-2724-9|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230606061125/https://history.army.mil/html/books/090/90-5-1/CMH_Pub_90-5-1.pdf|archive-date=June 6, 2023}}</ref> 64 wounded<ref>{{Cite web |date=March 1970 |title=Asian Allies in Vietnam |url=http://175thengineers.homestead.com/Philcav.pdf |access-date=18 October 2015 |publisher=Embassy of South Vietnam|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230521032045/http://175thengineers.homestead.com/Philcav.pdf|archive-date=May 21, 2023}}</ref> | |||

| {{Endplainlist}} | |||

| '''Total military dead:<br />333,620 (1960–1974) – 392,364 (total)'''<br />'''Total military wounded:<br />≈1,340,000+'''<ref name=Tucker/>{{Rp|}}<br />(excluding ])<br />'''Total military captured:<br />{{est.}} 1,000,000+''' | |||

| | casualties3 = {{Plainlist}} | |||

| * '''Vietnamese civilian dead''': 405,000–2,000,000<ref name=Lewy/>{{Rp|450–453}}<ref name="Shenon">{{Cite news |last=Shenon |first=Philip |date=23 April 1995 |title=20 Years After Victory, Vietnamese Communists Ponder How to Celebrate |work=] |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1995/04/23/world/20-years-after-victory-vietnamese-communists-ponder-how-to-celebrate.html |access-date=24 February 2011 |quote=The Vietnamese government officially claimed a rough estimate of 2 million civilian deaths, but it did not divide these deaths between those of North and South Vietnam.|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230527230912/https://www.nytimes.com/1995/04/23/world/20-years-after-victory-vietnamese-communists-ponder-how-to-celebrate.html|archive-date=May 27, 2023}}</ref><ref name="Obermeyer">{{Cite journal |last1=Obermeyer |first1=Ziad |last2=Murray |first2=Christopher J. L. |last3=Gakidou |first3=Emmanuela |date=23 April 2008 |title=Fifty years of violent war deaths from Vietnam to Bosnia: analysis of data from the world health survey programme |journal=] |volume=336 |issue=7659 |pages=1482–1486 |doi=10.1136/bmj.a137 |pmc=2440905 |pmid=18566045 |quote=From 1955 to 2002, data from the surveys indicated an estimated 5.4 million violent war deaths{{Nbsp}}... 3.8 million in Vietnam}}</ref> | |||

| * '''Vietnamese total dead''': 966,000<ref name=Hirschman/>–3,010,000<ref name=Obermeyer/> | |||

| * '''Cambodian Civil War dead''': 275,000–310,000<ref name="Heuveline">{{Cite book |last=Heuveline |first=Patrick |title=Forced Migration and Mortality |publisher=] |year=2001 |isbn=978-0-309-07334-9 |pages=102–104, 120, 124 |chapter=The Demographic Analysis of Mortality Crises: The Case of Cambodia, 1970–1979 |quote=As best as can now be estimated, over two million Cambodians died during the 1970s because of the political events of the decade, the vast majority of them during the mere four years of the 'Khmer Rouge' regime.{{Nbsp}}... Subsequent reevaluations of the demographic data situated the death toll for the in the order of 300,000 or less.}}</ref><ref name="Banister">{{Cite book |last1=Banister |first1=Judith |url=https://archive.org/details/genocidedemocrac00kier |title=Genocide and Democracy in Cambodia: The Khmer Rouge, the United Nations and the International Community |last2=Johnson |first2=E. Paige |publisher=Yale University Southeast Asia Studies |year=1993 |isbn=978-0-938692-49-2 |page= |quote=An estimated 275,000 excess deaths. We have modeled the highest mortality that we can justify for the early 1970s. |url-access=registration}}</ref><ref name="Sliwinski">{{Cite book |last=Sliwinski |first=Marek |title=Le Génocide Khmer Rouge: Une Analyse Démographique |publisher=] |year=1995 |isbn=978-2-7384-3525-5 |pages=42–43, 48 |trans-title=The Khmer Rouge genocide: A demographic analysis}}</ref> | |||

| * '''Laotian Civil War dead''': 20,000–62,000<ref name=Obermeyer/> | |||

| * '''Non-Indochinese military dead''': 65,494 | |||

| * '''Total dead''': 1,326,494–3,447,494 | |||

| * For more information see ] and ] | |||

| {{Endplainlist}} | |||

| | notes = {{flagicon image|Flag of FULRO.svg}} ] fought an ] against both ] and ] with the ] and was supported by ] for much of the war. | |||

| | campaignbox = {{Campaignbox Indochina Wars}} | |||

| {{Campaignbox Vietnam War}} | |||

| {{Campaignbox Vietnam War massacres}} | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| The '''Vietnam War''' | |||

| (also known colloquially as '''Vietnam''' or '''Nam''' as well as the '''American War''' in Vietnam) {{fn|1}} was a conflict in which the ] (DRVN, or North Vietnam) and its allies fought against the ] (RVN, or South Vietnam) and its allies. North Vietnam's allies included the ], the ] and the ]. South Vietnam's allies included the ] and ]. US combat troops were involved from ] until their official withdrawal in ]. During this period, 17% of South Vietnam inhabitants were killed. The war ended on ], ] with the military conquest of the South by the North. | |||

| The '''Vietnam War''' (1 November 1955{{Refn|Due to the early presence of US troops in Vietnam, the start date of the Vietnam War is a matter of debate. In 1998, after a high-level review by the ] (DoD) and through the efforts of ]'s family, the start date of the Vietnam War according to the US government was officially changed to 1 November 1955.<ref>{{Cite news |title=Name of Technical Sergeant Richard B. Fitzgibbon to be added to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial |publisher=] |url=http://www.defense.gov/Releases/Release.aspx?ReleaseID=1902 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131020044326/http://www.defense.gov/Releases/Release.aspx?ReleaseID=1902 |archive-date=20 October 2013}}</ref> US government reports currently cite 1 November 1955 as the commencement date of the "Vietnam Conflict", because this date marked when the US ] (MAAG) in Indochina (deployed to Southeast Asia under President Truman) was reorganized into country-specific units and MAAG Vietnam was established.<ref name="Lawrence">{{Cite book |last=Lawrence |first=A.T. |title=Crucible Vietnam: Memoir of an Infantry Lieutenant |publisher=McFarland |year=2009 |isbn=978-0-7864-4517-2}}</ref>{{Rp|20}} Other start dates include when Hanoi authorized Viet Cong forces in South Vietnam to begin a low-level insurgency in December 1956,{{Sfn|Olson|Roberts|2008|p=67}} whereas some view 26 September 1959, when the first battle occurred between the Viet Cong and the South Vietnamese army, as the start date.<ref name="WarBegan">{{Cite book |title=The Pentagon Papers (Gravel Edition), Volume 1 |publisher=Beacon Press |year=1971 |location=Boston |at=Section 3, pp. 314–346 |chapter=Chapter 5, Origins of the Insurgency in South Vietnam, 1954–1960 |access-date=17 August 2008 |chapter-url=http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/pentagon/pent14.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171019184424/https://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/pentagon/pent14.htm |archive-date=19 October 2017 |url-status=dead |via=International Relations Department, Mount Holyoke College}}</ref>|group="A"|name="start date"}} – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in ], ], and ] fought between ] (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and ] (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam was supported by the ] and ], while South Vietnam was supported by the ] and other ] nations. The conflict was the second of the ] and a major ] of the ] between the Soviet Union and US. ] greatly escalated from 1965 until its withdrawal in 1973. The fighting spilled over into the ] and ]s, which ended with all three countries becoming communist in 1975. | |||

| ==Background== | |||

| After the defeat of ] in the ] that began in 1946, Vietnam gained independence in the ] but was divided into two parts at the ]: the ], led by ], took control of North Vietnam, while the US assumed financial and military support for South Vietnam, led by ].<ref name="advisors" group="A">Prior to this, the ] (with an authorized strength of 128 men) was set up in September 1950 with a mission to oversee the use and distribution of US military equipment by the French and their allies.</ref> The North Vietnamese began supplying and directing the ] (VC), a ] of dissidents in the south, which intensified a ] from 1957. In 1958, North Vietnam ], establishing the ] to supply and reinforce the VC. By 1963, the north had covertly sent 40,000 soldiers of its own ] (PAVN), armed with Soviet and Chinese weapons, to fight in the insurgency in the south. President ] increased US involvement from 900 ] in 1960 to 16,300 in 1963 and sent more aid to the ] (ARVN), which failed to produce results. In 1963, Diem was killed in ], which added to the south's instability. | |||

| Hi The Vietnam War began after the division of Vietnam into two zones with a ] (DMZ) between them. The Vietnam War ostensibly began as a ] between feuding governments. Being Western-oriented and perceived as less popular than ]'s northern government, the South Vietnamese government fought largely to maintain its governing status within the partitioned entity, rather than to "unify the country" as was agreed to at the ]. Fighting began in ], and steadily escalated from there, with the ], the ] and the ] all eventually becoming involved. The conflict spilled over into the neighboring countries of ] and ]. North Vietnam did not respect the independence or borders of either country. | |||

| Following the ] in 1964, the US Congress passed ] that gave President ] authority to increase military presence without a declaration of war. Johnson launched ] and began sending combat troops, dramatically increasing deployment to 184,000 by the end of 1965, and to 536,000 by the end of 1968. US forces relied on ] and overwhelming firepower to conduct ] operations in rural areas. In 1968, North Vietnam launched the ], which was a tactical defeat but convinced many in the US that the war could not be won. The PAVN began engaging in more ]. Johnson's successor, ], began a policy of "]" from 1969, which saw the conflict fought by an expanded ARVN, while US forces withdrew. A ] in Cambodia resulted in a PAVN invasion and a US–ARVN ], escalating its civil war. US troops had mostly withdrawn from Vietnam by 1972, and the 1973 ] saw the rest leave. The accords were broken almost immediately and fighting continued until the ] and ] to the PAVN, marking the war's end. North and South Vietnam were reunified in 1976. | |||

| The Geneva partition was not a natural division of Vietnam and was not intended to create two separate countries. But the South government, with the support of the United States, blocked the Geneva scheduled ]s for unification. In the context of the ], and with the recent ] as a precedent, the U.S. had feared that a unified Vietnam would result in a ] government under ], either freely or fraudulently. | |||

| The war exacted ]: estimates of Vietnamese soldiers and civilians killed range from 970,000 to 3 million. Some 275,000–310,000 ], 20,000–62,000 ], and 58,220 US service members died.{{Refn|The figures of 58,220 and 303,644 for US deaths and wounded come from the Department of Defense Statistical Information Analysis Division (SIAD), Defense Manpower Data Center, as well as from a Department of Veterans fact sheet dated May 2010; the total is 153,303 WIA excluding 150,341 persons not requiring hospital care<ref>{{Cite report |url=http://www1.va.gov/opa/publications/factsheets/fs_americas_wars.pdf |title=America's Wars |date=May 2010 |publisher=Department of Veterans Affairs |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140124020810/http://www.va.gov/opa/publications/factsheets/fs_americas_wars.pdf |archive-date=24 January 2014 |url-status=dead}}</ref> the CRS (]) Report for Congress, American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics, dated 26 February 2010,<ref>{{Cite report |url=https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/RL32492.pdf |title=American War and Military Operations: Casualties: Lists and Statistics |last1=Anne Leland |last2=Mari–Jana "M-J" Oboroceanu |date=26 February 2010 |publisher=Congressional Research Service |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230514171012/https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/RL32492.pdf|archive-date=May 14, 2023}}</ref> and the book Crucible Vietnam: Memoir of an Infantry Lieutenant.<ref name=Lawrence/>{{Rp|65,107,154,217}} Some other sources give different figures (e.g. the 2005/2006 documentary ''Heart of Darkness: The Vietnam War Chronicles 1945–1975'' cited elsewhere in this article gives a figure of 58,159 US deaths,<ref>{{Cite AV media |url=https://www.amazon.com/Heart-Darkness-Vietnam-Chronicles-1945-1975/dp/B000GDIBT8 |title=Heart of Darkness: The Vietnam War Chronicles 1945–1975 |type=Documentary |publisher=Koch Vision |time=321 minutes |format=DVD |isbn=1-4172-2920-9 |people=Aaron Ulrich (editor); Edward FeuerHerd (producer and director) (2005, 2006) |access-date=11 May 2017 |archive-date=29 March 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190329215600/https://www.amazon.com/Heart-Darkness-Vietnam-Chronicles-1945-1975/dp/B000GDIBT8 |url-status=live }}</ref> and the 2007 book ''Vietnam Sons'' gives a figure of 58,226){{citation needed|date=November 2024}}|name=USd&w|group=A}} Its end would precipitate the ] and the larger ], which saw millions leave Indochina, an estimated 250,000 perished at sea.<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":6" /> The US destroyed 20% of South Vietnam's jungle and 20–50% of the ] forests, by spraying over {{convert|20|e6USgal|e6L|round=5|abbr=off|sp=us}} of toxic herbicides;<ref name=":02" /><ref name="Kolko">{{Cite book |last=Kolko |first=Gabriel |url=https://archive.org/details/anatomyofwarviet00kolk |title=Anatomy of a War: Vietnam, the United States, and the Modern Historical Experience |publisher=Pantheon Books |year=1985 |isbn=978-0-394-74761-3 |url-access=registration}}</ref>{{Rp|144–145}}<ref name=":0" /> a notable example of ].<ref name=":2" /> The ] carried out the ], while conflict between them and the unified Vietnam escalated into the ]. In response, China ], with ] lasting until 1991. Within the US, the war gave rise to ], a public aversion to American overseas military involvement,<ref>{{Cite web |last=Kalb |first=Marvin |date=22 January 2013 |title=It's Called the Vietnam Syndrome, and It's Back |url=http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/up-front/posts/2013/01/22-obama-foreign-policy-kalb |access-date=12 June 2015 |publisher=Brookings Institution |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20221224132036/https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2013/01/22/its-called-the-vietnam-syndrome-and-its-back/|archive-date=December 24, 2022}}</ref> which, with the ], contributed to the crisis of confidence that affected America throughout the 1970s.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Horne |first=Alistair |title=Kissinger's Year: 1973 |publisher=Phoenix |year=2010 |isbn=978-0-7538-2700-0 |pages=370–371}}</ref> | |||

| The South Vietnamese government and its Western allies portrayed the conflict as based in a principled ] —to deter the ] of Soviet-based control throughout ], and to set the tone for any likely future ] conflicts. The North Vietnamese government and its Southern affiliated organization ] viewed the war as a struggle to reunite the country and to repel a ] aggressor —a virtual continuation of the ] for independence against the French. While North Vietnam used nationalist propaganda, its party doctrine denounced the very concept of nationalism and any form of unity other than rule by the party. | |||

| ==Names== | |||

| France had gained control of Indochina in a series of ] wars beginning in the 1840s and lasting until the 1880s. At the ] negotiations in 1919, Hồ Chí Minh requested participation in order to arrange more freedom for the Indochinese colonies. His request was rejected, and ]'s status as a colony of France remained unchanged. During ], ] had collaborated with the occupying ]ese forces. Vietnam was under effective Imperial Japanese control, as well as ] Japanese ] control, although the Vichy French continued to serve as the official administrators until 1944. In that year, the Japanese overthrew the French and humiliated the colonial officials of the state in front of the Vietnamese population. The Japanese then began to encourage nationalist activity among the Vietnamese. Late in the war, Japan granted Vietnam nominal independence. After the Japanese surrender, Vietnamese ] expected to take control of the country and organize a socialist dictatorship. The Japanese army in Indochina attempted to assist the Viet Minh in their goal by keeping French soldiers imprisoned and handing over public buildings to Vietnamese nationalist groups. | |||

| Various names have been applied and have shifted over time, though ''Vietnam War'' is the most commonly used title in ]. It has been called the ''Second Indochina War'' since it spread to ] and ],<ref name="Factasy">{{Cite web |last=Factasy |title=The Vietnam War or Second Indochina War |url=http://www.prlog.org/10118782-the-vietnam-war-or-second-indochina-war.html |access-date=29 June 2013 |publisher=PRLog|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230425152621/https://www.prlog.org/10118782-the-vietnam-war-or-second-indochina-war.html|archive-date=April 25, 2023}}</ref> the ''Vietnam Conflict'',<ref>{{Cite web |date=15 August 2016 |title=The National Archives – Vietnam Conflict Extract Data File |url=https://www.archives.gov/research/military/vietnam-war/casualty-statistics |access-date=8 December 2020 |archive-date=26 May 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200526173917/https://www.archives.gov/research/military/vietnam-war/casualty-statistics |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Marlatt |first=Greta E. |title=Research Guides: Vietnam Conflict: Maps |url=https://libguides.nps.edu/vietnamwar/maps |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230405200653/https://libguides.nps.edu/vietnamwar/maps |archive-date=April 5, 2023 |access-date=11 April 2021 |website=Libguides.nps.edu}}</ref> and ''Nam'' (colloquially 'Nam). In Vietnam it is commonly known as ''Kháng chiến chống Mỹ'' ({{Literally|Resistance War against America}}).<ref>{{Cite book |last=Meaker |first=Scott S.F. |title=Unforgettable Vietnam War: The American War in Vietnam – War in the Jungle |year=2015 |isbn=978-1-312-93158-9}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Burns |first=Robert |date=January 27, 2018 |title=Grim reminders of a war in Vietnam, a generation later |url=https://www.concordmonitor.com/Grim-reminders-of-a-war-in-Vietnam-a-generation-later-15159686 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180128005729/https://www.concordmonitor.com/Grim-reminders-of-a-war-in-Vietnam-a-generation-later-15159686 |archive-date=2018-01-28 |access-date=2019-02-28 |website=Concord Monitor |quote=It's been more than for 40-plus years, the war that Americans simply call Vietnam but the Vietnamese refer to as their Resistance War Against America.}}</ref> The ] officially refers to it as the ''Resistance War against America to Save the Nation.''<ref>{{Cite web |last=Miller |first=Edward |title=Vietnam War perspective: the unreconciled conflict |url=https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2017/12/18/vietnam-war-perspective-unreconciled-conflict/962358001/ |access-date=2023-09-06 |website=USA TODAY |language=en-US |archive-date=6 September 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230906182356/https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2017/12/18/vietnam-war-perspective-unreconciled-conflict/962358001/ |url-status=live }}</ref> It is sometimes called the ''American War''.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Asian-Nation: Asian American History, Demographics, & Issues:: The American / Viet Nam War |url=http://www.asian-nation.org/vietnam-war.shtml |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230527183201/https://www.asian-nation.org/vietnam-war.shtml |archive-date=May 27, 2023 |access-date=18 August 2008 |quote=The Viet Nam War is also called 'The American War' by the Vietnamese}}</ref> | |||

| == Background == | |||

| On ], 1945, Hồ Chí Minh spoke at a ] which announced the formation of a new Vietnamese government under his leadership. In his speech he cited the US ] and a band played "]." Ho had hoped that the United States would be an ally of a Vietnamese reunification movement based on speeches by U.S. President ] against the continuation of European ] after World War II. Indochina had been in the ] and ] area of occupation at the end of the war. The Chinese army arrived in September 1945 and took over areas north of the 16th parallel. The British arrived in October 1945 and supervised the surrender and departure of the Japanese army from Indochina south of the 16th parallel. In the south, the French prevailed upon the British to turn control of the region back over to them. French officials, when released from Japanese prisons at the end of September 1945, also took matters into their own hands in some areas. In the north, France negotiated with both China and the Viet Minh. The Viet Minh eventually allowed French forces to land outside Hanoi. France agreed to recognize Vietnam within the French Union. Negotiations soon afterward collapsed, setting the stage for the ] in which France attempted to reestablish Vietnam as part of a French overseas domain. In a gradual process — accelerated by the establishment of the People's Republic of China — the Vietnamese nationalist army, the Viet Minh, gradually built a well-equipped modern conventional army. While they could not defeat the French in the populated areas of the country, they did manage to gain control over the border with China and remote areas in places like Laos. | |||

| {{Main|French conquest of Vietnam|French Indochina}} | |||

| Vietnam had been under French control as part of ] since the mid-19th century. Under French rule, Vietnamese nationalism was suppressed, so revolutionary groups conducted their activities abroad, particularly in France and China. One such nationalist, ], established the ] in 1930, a ] political organization which operated primarily in ] and the ]. The party aimed to overthrow French rule and establish an independent communist state in Vietnam.<ref name=":3">{{Cite book |last=Umair Mirza |url=http://archive.org/details/thevietnamwarthedefinitiveillustratedhistory_202002 |title=The Vietnam War The Definitive Illustrated History |date=2017-04-01}}</ref> | |||

| === Japanese occupation of Indochina === | |||

| After the Viet Minh's victory over the French at the ] France decided to negotiate a withdrawal from Indochina. All of Indochina was granted independence, including Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. However, Vietnam was partitioned at the 17<sup>th</sup> parallel, above which the former Viet Minh established a Communist state and below which a non-communist state was established under the Emperor ]. As dictated in the Geneva Accords of 1954 the division was meant to be temporary pending free elections for national leadership. The agreement stipulated that these two military zones, which were separated by the temporary demarcation line, "should not in any way be interpreted as constituting a political or territorial boundary," and specifically stated "general elections shall be held in July 1956." But such elections were not held as Diem (see below), who had not signed the Geneva Accords, refused to hold them and did not believe that fair elections could be held in the north. The U.S. supported this move to maintain its Southern ally, also claiming that Ho had no intention of holding free elections. A part of the Vietnamese population were angered that the scheduled elections for the unification of the country never took place. The United States, fearing a Communist takeover of the region, supported ], who had ousted Bảo Đại, as leader of South Vietnam while Hồ Chí Minh remained leader of the North. | |||

| {{Main|French Indochina in World War II|1940–1946 in French Indochina}} | |||

| ] flag, which later became the flag of ], prototype of the ] of contemporary Vietnam]] | |||

| In September 1940, ] French Indochina, following France's ] to ]. French influence was suppressed by the Japanese, and in 1941 Cung, now known as ], returned to Vietnam to establish the ], an anti-Japanese resistance movement that advocated for independence.<ref name=":3" /> The Viet Minh received aid from the ], namely the US, Soviet Union, and ]. Beginning in 1944, the US ] (O.S.S.) provided the Viet Minh with weapons, ammunition, and training to fight the occupying Japanese and ] forces.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2020-07-15 |title=The OSS in Vietnam, 1945: A War of Missed Opportunities by Dixee Bartholomew-Feis |url=https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/oss-vietnam-1945-dixee-bartholomew-feis |access-date=2023-12-19 |website=The National WWII Museum {{!}} New Orleans |language=en |archive-date=15 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230315115133/https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/oss-vietnam-1945-dixee-bartholomew-feis |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name=":7" /> ] against the Vietnamese people led many to join the resistance, and by the end of 1944 the Viet Minh had grown to over 500,000 members.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Defense |first=United States Department of |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MHjOVH6k5BQC&pg=RA1-PA4 |title=United States-Vietnam Relations, 1945-1967: Study |date=1971 |publisher=U.S. Government Printing Office |language=en}}</ref> US President ] continued to support Vietnamese resistance throughout the war, and proposed that Vietnam's independence be granted under an international trusteeship after the war was over.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Hess |first=Gary R. |date=1972 |title=Franklin Roosevelt and Indochina |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/1890195 |journal=The Journal of American History |volume=59 |issue=2 |pages=353–368 |doi=10.2307/1890195 |jstor=1890195 |issn=0021-8723 |access-date=19 December 2023 |archive-date=14 April 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240414004902/https://www.jstor.org/stable/1890195 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In March 1945, Japan, losing the war, ] in Indochina, establishing the ] and installing Vietnamese Emperor ] as its figurehead leader.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Smith |first=Ralph B. |date=September 1978 |title=The Japanese Period in Indochina and the Coup of 9 March 1945 |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-southeast-asian-studies/article/abs/japanese-period-in-indochina-and-the-coup-of-9-march-1945/275B1ABEED60A9B95F85297F68603286 |journal=Journal of Southeast Asian Studies |language=en |volume=9 |issue=2 |pages=268–301 |doi=10.1017/S0022463400009784 |issn=1474-0680}}</ref> Following the ] in August, the Viet Minh launched the ], overthrowing the Japanese-backed state and seizing weapons from the surrendering Japanese forces. On 2 September, Ho Chi Minh proclaimed the ] (DRV).<ref name=":5">{{Cite web |title=Page:Pentagon-Papers-Part I.djvu/30 - Wikisource, the free online library |url=https://en.wikisource.org/Page:Pentagon-Papers-Part_I.djvu/30 |access-date=2023-12-19 |website=en.wikisource.org |language=en |archive-date=31 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231031133156/https://en.wikisource.org/Page%3APentagon-Papers-Part_I.djvu/30 |url-status=live }}</ref> However, on 23 September, French forces overthrew the DRV and reinstated French rule.<ref name=":5" /> American support for the Viet Minh promptly ended, and O.S.S. forces left as the French ]. | |||

| Beginning in the summer of 1955, Diem launched a 'Denounce the Communists' campaign, in which communists and other anti-government elements were arrested and imprisoned. Hanoi remained cautious, however, and was committed to consolidating power in the north before pursuing reunification. After the failure to hold unification elections in 1956, in 1958 Hanoi began to give more attention to the issue of unification. The high ranking communist ], who had stayed in South Vietnam as a covert agent, returned to Hanoi and argued for the ] (VWP) to adopt a more aggressive unification strategy. In January 1959, the Central Committee of the VWP issued a secret resolution authorizing the use of armed struggle in the South. In December 1960, under instruction from Hanoi, southern communists established the ] to spearhead the anti-government insurrection. | |||

| === First Indochina War === | |||

| The NLF was composed of South Vietnam intellectuals who dissented with the South Vietnamese government, and southern communists who had remained there after the partition and regroupment of 1954. Among them were ], ], and ]. Those communists did not have an independent status from the VWP but received direct orders from Hanoi for the activities of the NLF. While there were many non-communist members of the NLF, they were ultimately subject to the control of the VWP cadres, and were increasingly side-lined as the conflict continued; they did however offer the NLF an image of 'respectability', and the NLF constantly sought to emphasize its supposedly non-communist nature. | |||

| {{Main|First Indochina War|War in Vietnam (1945–1946)}} | |||

| ] (right) as the "supreme advisor" to the government of the ] led by president ] (left), 1 June 1946{{citation needed|date=December 2024}}]] | |||

| Tensions between the Viet Minh and French authorities had erupted into ] by 1946, a conflict which soon became entwined with the wider ]. On 12 March 1947, US president ] announced the ], an ] foreign policy which pledged US support to nations resisting "attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Administration |first=United States National Archives and Records |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qqDA6OGvhmUC&pg=PA194 |title=Our Documents: 100 Milestone Documents from the National Archives |date=2006-07-04 |publisher=Oxford University Press, USA |isbn=978-0-19-530959-1 |language=en |access-date=6 March 2024 |archive-date=30 June 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230630110920/https://books.google.com/books?id=qqDA6OGvhmUC&pg=PA194 |url-status=live }}</ref> In Indochina, this doctrine was first put into practice in February 1950, when the United States recognized the French-backed ] in ], led by former Emperor Bảo Đại, as the legitimate government of Vietnam, after the ]s of the ] and ] recognized the ], led by Ho Chi Minh, as the legitimate Vietnamese government the previous month.<ref name="McNamara">{{Cite book |last1=McNamara |first1=Robert S. |url=https://archive.org/details/argumentwithoute00mcna |title=Argument Without End: In Search of Answers to the Vietnam Tragedy |last2=Blight |first2=James G. |last3=Brigham |first3=Robert K. |last4=Biersteker |first4=Thomas J. |last5=Schandler |first5=Herbert |date=1999 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1-891620-87-4 |location=New York |author-link=Robert McNamara |author-link4=Thomas J. Biersteker |url-access=registration}}</ref>{{Rp|377–379}}<ref name=Hastings/>{{Rp|88}} The outbreak of the ] in June convinced Washington policymakers that the war in Indochina was another example of communist expansionism, directed by the Soviet Union.<ref name=Hastings/>{{Rp|33–35}} | |||

| The North Vietnamese occupied large parts of eastern Laos and supplied the NLF via the ] with mostly Chinese made weapons. The Soviet Union did not provide military aid to Hanoi to invade South Vietnam until Nikita Khrushchev was ousted in 1964. The Ho Chi Minh trail ran from North Vietnam through Laos and Cambodia (a violation of neutrality) into South Vietnam. Some boats carrying supplies via the China Sea were also inderdicted by the South Vietnamese authorities. In 1965, the supposedly neutralist government of Cambodia made a deal with China and the North Vietnamese that allowed Vietnamese forces to establish permanent bases in the country and to use the port of Sihanoukville for delivery of military supplies until this supply route was closed by ] in 1970. The Hồ Chí Minh Trail was steadily expanded to become the vital lifeline for communist forces in South Vietnam, which included the North Vietnamese Army in the 1960s when it became a major target of U.S. air operations. | |||

| Military advisors from China began assisting the Viet Minh in July 1950.<ref name="Ang">{{Cite book |last=Ang |first=Cheng Guan |title=The Vietnam War from the Other Side |publisher=Routledge |year=2002 |isbn=978-0-7007-1615-9}}</ref>{{Rp|14}} Chinese weapons, expertise, and laborers transformed the Viet Minh from a guerrilla force into a regular army.<ref name=Hastings/>{{Rp|26}}<ref name="HistoryPlace">{{Cite web |title=The History Place – Vietnam War 1945–1960 |url=http://www.historyplace.com/unitedstates/vietnam/index-1945.html |access-date=11 June 2008|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230312070611/http://www.historyplace.com/unitedstates/vietnam/index-1945.html|archive-date=March 12, 2023}}</ref> In September 1950, the US further enforced the Truman Doctrine by creating a ] (MAAG) to screen French requests for aid, advise on strategy, and train Vietnamese soldiers.<ref name="Herring">{{Cite book |last=Herring |first=George C. |title=America's Longest War: The United States and Vietnam, 1950–1975 (4th ed.) |date=2001 |publisher=McGraw-Hill |isbn=978-0-07-253618-8}}</ref>{{Rp|18}} By 1954, the US had spent $1 billion in support of the French military effort, shouldering 80% of the cost of the war.<ref name=Hastings/>{{Rp|35}} | |||

| The Diệm government was initially able to cope with the insurgency with the aid of U.S. advisors, and by 1962 seemed to be winning. Senior U.S. military leaders were receiving positive reports from the U.S. commander, Gen. ] of the ]. Outside Saigon, large areas of the country were infiltrated by communists who had remained in the south after the Geneva Accord, and a combination of newcomers from the North and 'returnees' who had gone to the northern zone after the Geneva Accords; but the South Vietnamese army was still able control most functions of local government. In 1963, a Communist offensive beginning with the ] inflicted major loss on South Vietnamese army units. This was the first large-scale battle, contrasting the assassinations and guerilla activities which had preceded it. Ap Bac was the sign that the war was escalating as the result of the increasing supplies of men and weapons from the North. The escalation of the war made some policy-makers in Washington think the Diem government could not cope with the invasion of communists and led to the idea of changing the leadership of South Vietnam. Diem was deeply unpopular with many sections of South Vietnamese society due to nepotism, corruption and a perceived bias in favour of the Catholic minority, of which he was a part, at the expense of the Buddhist majority. The military coup that overthrew Diem caused chaos in the security and defense systems of South Vietnam; Hanoi took advantage of this chaos to increase its infiltration of South Vietnamese society and supports to its forces in the South, while South Vietnam entered a period of extreme political instability and saw a succession of different military rulers. | |||

| ==== Battle of Dien Bien Phu ==== | |||

| Following Diem's demise, the United States involvement dramatically escalated and the 'Americanization' of the war began. | |||

| {{Main|Battle of Dien Bien Phu|Operation Vulture}} | |||

| During the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954, US ] sailed to the ] and the US conducted reconnaissance flights. France and the US discussed the use of ]s, though reports of how seriously this was considered and by whom, are vague.<ref name="Maclear">{{Cite book |last=Maclear |first=Michael |url=https://archive.org/details/tenthousanddaywa00mich/page/57 |title=The Ten Thousand Day War: Vietnam 1945–1975 |date=1981 |publisher=Thames |isbn=978-0-312-79094-3 |page=}}</ref><ref name=Hastings/>{{Rp|75}} According to then-Vice President ], the Joint Chiefs of Staff drew up plans to use nuclear weapons to support the French.<ref name=Maclear/> Nixon, a so-called "]", suggested the US might have to "put American boys in".<ref name=Tucker/>{{Rp|76}} President ] made American participation contingent on British support, but the British were opposed.<ref name=Tucker/>{{Rp|76}} Eisenhower, wary of involving the US in an Asian land war, decided against intervention.<ref name=Hastings/>{{Rp|75–76}} Throughout the conflict, US intelligence estimates remained skeptical of France's chance of success.<ref name="Gravel">{{Cite book |title=The Pentagon Papers (Gravel Edition), Volume 1 |pages=391–404}}</ref> | |||

| ==The United States Involvement== | |||

| ] was the president of North Vietnam.]] | |||

| ===Harry S. Truman and Vietnam (1945-1953)=== | |||

| On 7 May 1954, the French garrison at Dien Bien Phu surrendered. The defeat marked the end of French military involvement in Indochina. At the ], they negotiated a ceasefire with the Viet Minh, and independence was granted to Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://vietnam.vassar.edu/overview/doc2.html|title=The Final Declarations of the Geneva Conference July 21, 1954|work=The Wars for Viet Nam|publisher=]|access-date=20 July 2011|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110807062726/http://vietnam.vassar.edu/overview/doc2.html|archive-date=7 August 2011}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Geneva Accords {{!}} history of Indochina {{!}} Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/event/Geneva-Accords |access-date=28 October 2022 |website=www.britannica.com |language=en |archive-date=28 October 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221028002543/https://www.britannica.com/event/Geneva-Accords |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ==Transition period== | |||

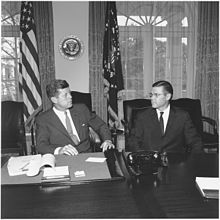

| Milestones of U.S. involvement under ] | |||

| {{Main|1954 Geneva Conference|Operation Passage to Freedom|Land reform in Vietnam|Land reform in North Vietnam|1954 in Vietnam}} | |||

| * March 9, 1945 - ] overthrows nominal French authority in Indochina and declares an independent Vietnamese puppet state. The French administration is disarmed. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| * August 15, 1945 - ] surrenders to the Allies. In Indochina, the Japanese administration allows ] to take over control of the country. This is called the ] even though it was not a revolution. Hồ Chí Minh borrows a phrase from the U.S. ] for his own declaration. Hồ Chí Minh fights with a variety of other political factions for control of the major cities. | |||

| * August 1945 - A few days after the Vietnamese "revolution", Chinese forces enter from the north and, as previously planned among the allies establish an administration in the country as far south as the 16th parallel. | |||

| * ], ] OSS officer Lt. Col. ] working with the ] to repatriate captured Americans from the Japanese was shot and killed becoming the first American casualty in Vietnam. | |||

| * October 1945 - British troops land in Southern Vietnam and establish a provisional administration. The British free the French soldiers imprisoned by the Japanese. The French begin taking control of the cities of Vietnam within the British region. | |||

| * February 1946 - The French sign an agreement with China. France gives up its concessions in Shanghai and other Chinese ports. In exchange, China agrees to assist the French in returning to Vietnam north of the 16th parallel. | |||

| *March 6, 1946 - After negotiations with the Chinese and the ], the French sign an agreement recognizing Vietnam within the ]. Shortly after, the French land at ] and occupy the rest of Vietnam. | |||

| * December 1946 - Negotiations between the Viet Minh and French break down. The Viet Minh are quickly driven out of Hanoi into the countryside. | |||

| * 1947-1949 - The Viet Minh fight a limited insurgency in remote rural areas of Vietnam. | |||

| * 1949 - Chinese communists reach the northern border of Indochina. The Viet Minh drive the French from the border region and begin to receive large amounts of weapons from the Soviet Union and China. The weapons transform the Viet Minh from an irregular small-scale insurgency into a conventional army. | |||

| * May 1st 1950 - After the capture of ] Island from ] forces by the Chinese Communists, Truman approves $10 million in military assistance for Indochina. | |||

| * Following the outbreak of the ], Truman announces "acceleration in the furnishing of military assistance to the forces of France and the Associated States in Indochina..." and sends 123 non-combat troops to help with supplies to fight against the communist Viet Minh. | |||

| * 1951 - Truman authorizes $150 million in French support. | |||

| At the 1954 Geneva Conference, Vietnam was temporarily partitioned at the ]. Ho Chi Minh wished to continue war in the south, but was restrained by Chinese allies who convinced him he could win control by electoral means.<ref>{{Cite news |date=1 January 2001 |title=China Contributed Substantially to Vietnam War Victory, Claims Scholar |language=en |work=Wilson Center |url=https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/china-contributed-substantially-to-vietnam-war-victory-claims-scholar |access-date=20 May 2018|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230502013703/https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/china-contributed-substantially-to-vietnam-war-victory-claims-scholar|archive-date=May 2, 2023}}</ref><ref name=Hastings/>{{Rp|87–88}} Under the Geneva Accords, civilians were allowed to move freely between the two provisional states for a 300-day period. Elections throughout the country were to be held in 1956 to establish a unified government.<ref name=Hastings/>{{Rp|88–90}} However, the US, represented at the conference by Secretary of State ], objected to the resolution; Dulles' objection was supported only by the representative of Bảo Đại.<ref name=":7" /> John Foster's brother, ], who was director of the ], then initiated a ] campaign which exaggerated anti-Catholic sentiment among the Viet Minh and distributed propaganda attributed to Viet Minh threatening an American attack on Hanoi with atomic bombs.<ref name=":7">{{Cite book |last=Kinzer |first=Stephen |title=The Brothers: John Foster Dulles, Allen Dulles, and Their Secret World War |date=2013 |publisher=Macmillan |isbn=978-1-4299-5352-8 |pages=}}</ref><ref>{{Cite thesis |last=Patrick |first=Johnson, David |title=Selling "Operation Passage to Freedom": Dr. Thomas Dooley and the Religious Overtones of Early American Involvement in Vietnam |date=2009 |publisher=University of New Orleans |url=https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/950/ |language=en|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230409174806/https://scholarworks.uno.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1931&context=td|archive-date=April 9, 2023}}</ref><ref name="Hastings" />{{Rp|96–97}} | |||

| ===Dwight D. Eisenhower and Vietnam (1953-1961)=== | |||

| Milestones of the escalation under ]. | |||

| During the 300-day period, up to one million northerners, mainly minority Catholics, moved south, fearing persecution by the Communists.<ref name=Hastings/>{{Rp|96}}<ref>{{Cite web |last=Prados |first=John |date=January–February 2005 |title=The Numbers Game: How Many Vietnamese Fled South In 1954? |url=http://www.vva.org/TheVeteran/2005_01/feature_numbersGame.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060527190340/http://www.vva.org/TheVeteran/2005_01/feature_numbersGame.htm |archive-date=27 May 2006 |access-date=11 May 2017 |publisher=The VVA Veteran}}</ref> The exodus was coordinated by a U.S.-funded $93 million relocation program, which involved the ] and the US ] to ferry refugees.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Murti |first=B.S.N. |url=https://archive.org/details/vietnamdivided0000unse |title=Vietnam Divided |date=1964 |publisher=Asian Publishing House |url-access=registration}}</ref> The northern refugees gave the later ] regime a strong anti-communist constituency.<ref name="Karnow">{{Harvnb|Karnow|1997}}</ref>{{Rp|238}} Over 100,000 Viet Minh fighters went to the north for "regroupment", expecting to return south within two years.<ref name=Kolko/>{{Rp|98}} The Viet Minh left roughly 5,000 to 10,000 ] in the south as a base for future insurgency.<ref name=Hastings/>{{Rp|104}} The last French soldiers left South Vietnam in April 1956<ref name=Hastings/>{{Rp|116}} and the PRC also completed its withdrawal from North Vietnam.<ref name=Ang/>{{Rp|14}} | |||

| * 1954 - ] defeat a French force at ]. The defeat, along with the end of the Korean war the previous year, triggers the French to seek a negotiated settlement to the war. | |||

| * 1954 - The ], called to determine the post-French future of Indochina, proposes a temporary division of Vietnam to be followed by unified nationwide elections in 1956. | |||

| * 1954 - Two months after the Geneva conference, North Vietnam forms Group 100 with headquarters at Ban Namèo. Its purpose is to direct, organize, train and supply the ] in their attempt to gain control of Laos. | |||

| * 1955 - Ho Chi Minh launches his anti-landlord movement in North Vietnam. Viet Minh cadres are sent into villages to liquidate their political opponents in the name of land reform. | |||

| * ], ] - Eisenhower deploys ] to train the South Vietnam Army. This marks the official beginning American involvement in the war as recognized by the ]. | |||

| * April 1956 - The last French troops leave Vietnam. | |||

| * 1955 - 1956 - 900,000 Vietnamese flee the Viet Minh administration in North Vietnam to South Vietnam. | |||

| * 1956 - National unification elections do not occur. | |||

| * December 1958 - North Vietnam invades Laos and occupies parts of the country | |||

| * ], ] - ] and ] become the first Americans killed in action in Vietnam according to the Memorial timeline where they are listed 1 and 2. | |||

| * September 1959 - North Vietnam forms Group 959 which assumes command of the Pathet Lao forces in Laos | |||

| ] | |||

| ===John F. Kennedy and Vietnam (1961-1963)=== | |||

| ====Timeline==== | |||

| *January 1961 - Soviet Premier ] pledges support for "]" throughout the world. The idea of creating a neutral Laos is suggested to Kennedy. | |||

| *May 1961 - Kennedy sends 400 American ] "Special Advisors" to South Vietnam to train South Vietnamese soldiers following a visit to the country by ]. | |||

| *June 1961 - Kennedy and Khrushchev meet at Vienna. Kennedy protests North Vietnam's attacks on Laos and points out that the U.S. was supporting the neutrality of Laos. Both leaders agree to pursue a policy of creating a neutral Laos. | |||

| *October 1961 - Following successful ] attacks, Defense Secretary ] recommends sending six divisions (200,000 men) to Vietnam, Kennedy sends 16,000 before the end of his Presidency in 1963. | |||

| *], ] - Kennedy signs the Foreign Assistance Act of 1962 which provides "...military assistance to countries which are on the rim of the Communist world and under direct attack." | |||

| *], ] - Viet Cong victory in the ]. | |||

| *May 1963 - Buddhists riot in South Vietnam after a conflict over the display of religious flags during the celebration of ]'s birthday. Some buddhists urge Kennedy to end support of ] who is Catholic | |||

| * May 1963 - ] suggests using ]s in the conflict | |||

| *], ] - Military officers launch a coup against Diem. Diem leaves the presidential residence. | |||

| *], ] - Diem is discovered and assassinated by rebel leaders. | |||

| *],]- Kennedy is assassinated | |||

| Between 1953 and 1956, the North Vietnamese government instituted agrarian reforms, including "rent reduction" and "land reform", which resulted in political oppression. During land reform, North Vietnamese witnesses suggested a ratio of one execution for every 160 village residents, which extrapolates to 100,000 executions. Because the campaign was mainly in the Red River Delta area, 50,000 executions became accepted by scholars.<ref name="Turner">{{Cite book |last=Turner |first=Robert F. |title=Vietnamese Communism: Its Origins and Development |date=1975 |publisher=Hoover Institution Press |isbn=978-0-8179-6431-3}}</ref>{{Rp|143}}<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Gittinger |first=J. Price |date=1959 |title=Communist Land Policy in North Viet Nam |journal=Far Eastern Survey |volume=28 |issue=8 |pages=113–126 |doi=10.2307/3024603 |jstor=3024603}}</ref><ref name="Courtois">{{Cite book |last1=Courtois |first1=Stephane |title=The Black Book of Communism |title-link=The Black Book of Communism |last2=Werth |first2=Nicolas |last3=Panne |first3=Jean-Louis |last4=Paczkowski |first4=Andrzej |last5=Bartosek |first5=Karel |last6=Margolin |first6=Jean-Louis |date=1997 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-674-07608-2 |display-authors=1}}</ref>{{Rp|569}}<ref>{{Cite book |last=Dommen |first=Arthur J. |title=The Indochinese Experience of the French and the Americans |date=2001 |publisher=Indiana University Press |isbn=978-0-253-33854-9 |page=340}}</ref> However, declassified documents from Vietnamese and Hungarian archives indicate executions were much lower, though likely greater than 13,500.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Vu |first=Tuong |date=25 May 2007 |title=Newly released documents on the land reform |url=http://www.lib.washington.edu/southeastasia/vsg/elist_2007/Newly |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110420044800/http://www.lib.washington.edu/southeastasia/vsg/elist_2007/Newly%20released%20documents%20on%20the%20land%20reform%20.html |archive-date=20 April 2011 |access-date=15 July 2016 |website=Vietnam Studies Group |quote=There is no reason to expect, and no evidence that I have seen to demonstrate, that the actual executions were less than planned; in fact the executions perhaps exceeded the plan if we consider two following factors. First, this decree was issued in 1953 for the rent and interest reduction campaign that preceded the far more radical land redistribution and party rectification campaigns (or waves) that followed during 1954–1956. Second, the decree was meant to apply to free areas (under the control of the Viet Minh government), not to the areas under French control that would be liberated in 1954–1955 and that would experience a far more violent struggle. Thus the number of 13,500 executed people seems to be a low-end estimate of the real number. This is corroborated by Edwin Moise in his recent paper "Land Reform in North Vietnam, 1953–1956" presented at the 18th Annual Conference on SE Asian Studies, Center for SE Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley (February 2001). In this paper Moise (7–9) modified his earlier estimate in his 1983 book (which was 5,000) and accepted an estimate close to 15,000 executions. Moise made the case based on Hungarian reports provided by Balazs, but the document I cited above offers more direct evidence for his revised estimate. This document also suggests that the total number should be adjusted up some more, taking into consideration the later radical phase of the campaign, the unauthorized killings at the local level, and the suicides following arrest and torture (the central government bore less direct responsibility for these cases, however).}}<br />cf. {{Cite journal |last=Szalontai |first=Balazs |date=November 2005 |title=Political and Economic Crisis in North Vietnam, 1955–56 |journal=] |volume=5 |issue=4 |pages=395–426 |doi=10.1080/14682740500284630 |s2cid=153956945}}<br />cf. {{Cite book |last=Vu |first=Tuong |title=Paths to Development in Asia: South Korea, Vietnam, China, and Indonesia |date=2010 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1-139-48901-0 |page=103 |quote=Clearly Vietnamese socialism followed a moderate path relative to China.{{Nbsp}}... Yet the Vietnamese 'land reform' campaign{{Nbsp}}... testified that Vietnamese communists could be as radical and murderous as their comrades elsewhere.}}</ref> In 1956, leaders in Hanoi admitted to "excesses" in implementing this program and restored much of the land to the original owners.<ref name=Hastings/>{{Rp|99–100}} | |||

| ====Containing Communist Expansion==== | |||

| ] | |||

| In June 1961, ] met with Soviet premier ] in ], where they had a bitter disagreement over key U.S.-Soviet issues. This led to the conclusion that Southeast Asia would be an area where Soviet forces would test the USA's commitment to the ] policy. | |||

| The south, meanwhile, constituted the State of Vietnam, with Bảo Đại as Emperor, and Ngô Đình Diệm as prime minister. Neither the US, nor Diệm's State of Vietnam, signed anything at the Geneva Conference. The non-communist Vietnamese delegation objected strenuously to any division of Vietnam, but lost when the French accepted the proposal of Viet Minh delegate ],<ref name="PP">{{Cite book |title=The Pentagon Papers (Gravel Edition), Volume 3 |date=1971 |publisher=Beacon Press}}</ref>{{Rp|134}} who proposed Vietnam eventually be united by elections under the supervision of "local commissions".<ref name=PP/>{{Rp|119}} The US countered with what became known as the "American Plan", with the support of South Vietnam and the UK.<ref name=PP/>{{Rp|140}} It provided for unification elections under the supervision of the UN, but was rejected by the Soviet delegation.<ref name=PP/>{{Rp|140}} The US said, "With respect to the statement made by the representative of the State of Vietnam, the United States reiterates its traditional position that peoples are entitled to determine their own future and that it will not join in any arrangement which would hinder this".<ref name=PP/>{{Rp|570–571}} | |||

| Although Kennedy's election campaign had stressed long-range missile parity with the Soviets, Kennedy was particularly interested in ]. Originally intended for use behind front lines after a conventional invasion of Europe, it was quickly decided to try them out in the "]" war in Vietnam. | |||

| US President Eisenhower wrote in 1954: | |||

| {{Blockquote|I have never talked or corresponded with a person knowledgeable in Indochinese affairs who did not agree that had elections been held as of the time of the fighting, possibly 80% of the population would have voted for the Communist Ho Chi Minh as their leader rather than Chief of State Bảo Đại. Indeed, the lack of leadership and drive on the part of Bảo Đại was a factor in the feeling prevalent among Vietnamese that they had nothing to fight for.{{Sfn|Eisenhower|1963|p=}}}} | |||

| ], commander of the ] religious movement, in Can Tho Military Court 1956]] | |||