| Revision as of 02:33, 5 May 2008 view sourceD.de.loinsigh (talk | contribs)574 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 15:06, 24 December 2024 view source Antiquary (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers38,782 editsm →top: Rm wl. Doggerland formed only a small part of that peninsula. It is wikilinked two sentences later. | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Archipelago in north-western Europe}} | |||

| {{mergefrom|British Isles naming dispute|Talk:British Isles#Merger proposal|date=May 2008}} | |||

| {{About|the geographical ]|those parts under British sovereignty|British Islands}} | |||

| {{pp-semi|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Use British English|date=August 2010}}<!--THIS ARTICLE USES BRITISH ENGLISH because this topic is British related. Please do not edit the British English spelling to American English spelling. The use of "are" in place of "is" in certain instances is considered grammatically correct. See ] for more information--> | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=November 2023}} | |||

| {{Infobox islands | |||

| {{toolong|date=April 2008}} | |||

| |local_name = | |||

| {{POV|date=May 2008}} | |||

| {{collapsible list | |||

| {{coor title d|54|N|4|W}} | |||

| |titlestyle = background:transparent; text-align:center; font-size:9pt; | |||

| |liststyle = text-align:center; | |||

| |title = Other native names | |||

| |1= {{native name|ga|Éire agus an Bhreatain Mhór}}<ref name="téarma.ie – Dictionary of Irish Terms">The British Isles ''s'' ''pl'' ''Na hOileáin bhriontanacha'' {{cite web | url = http://www.tearma.ie/Search.aspx?term=the+British+Isles | title = the British Isles | work = téarma.ie – Dictionary of Irish Terms | publisher = ] and ] | access-date = 18 November 2016}}</ref> | |||

| |2 = {{native name|cy|Ynysoedd Prydain}} | |||

| |3 = {{native name|kw|Enesow Bretennek}} | |||

| |4 = {{native name|gd|Eileanan Bhreatainn}}<ref>{{Citation|url=http://www.gla.ac.uk/departments/celtic/duilleagangidhlig/|title=University of Glasgow Department of Celtic}}</ref> | |||

| |5 = {{native name|gv|Ny h-Ellanyn Goaldagh}}<ref>{{Citation|url=http://www.tynwald.org.im/papers/press/2008/pr33.pdf|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090224221228/http://www.tynwald.org.im/papers/press/2008/pr33.pdf|url-status=dead|archive-date=24 February 2009|title=Office of The President of Tynwald}}</ref> | |||

| |6 = {{native name|fr|Îles Britanniques}}<ref>{{cite web|title=Règlement (1953) (Amendement) Sur l'importation et l'exportation d'animaux|url=https://www.jerseylaw.je/laws/enacted/Pages/L-17-1953.aspx|website=]|access-date=2 February 2012}}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| |image_name = MODIS - Great Britain and Ireland - 2012-06-04 during heat wave.jpg | |||

| |image_caption = A 2012 ] satellite image of the British Isles, excluding ] and the ] which are out of the frame | |||

| |image_alt = A map of the British Isles and their location in Europe. | |||

| |map_image = British Isles (orthographic projection).svg | |||

| |map_size = 220 | |||

| |location = ] | |||

| |coordinates = {{Coord|54|N|4|W|scale:10000000|display=inline,title}} | |||

| |waterbody = ] | |||

| |area_km2 = 315159 | |||

| |area_footnotes = <ref name="UNEP"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181213045516/http://islands.unep.ch/Cindex.htm |date=13 December 2018}}, United Nations Environment Programme. Retrieved 9 August 2015.<br /> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304050532/https://www.gov.im/categories/business-and-industries/iom-key-facts-guide/island-facts/ |date=4 March 2016}}, Isle of Man Government. Retrieved 9 August 2015.<br />According to the UNEP, the Channel Islands have a land area of {{val|194|u=km2|fmt=commas}}, the Republic of Ireland has a land area of {{val|70,282|u=km2|fmt=commas}}, and the United Kingdom has a land area of {{val|244,111|u=km2|fmt=commas}}. According to the Isle of Man Government, the Isle of Man has a land area of {{val|572|u=km2|fmt=commas}}. Therefore, the overall land area of the British Isles is {{val|315159|u=km2|fmt=commas}}.</ref> | |||

| |total_islands = 6,000+ | |||

| |highest_mount = {{nowrap|]}}<ref name="Ordnance Survey Blog-2016">{{Cite news|url=https://www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/blog/2016/03/britains-tallest-mountain-is-taller/|title=Great Britain's tallest mountain is taller - Ordnance Survey Blog|date=18 March 2016|work=Ordnance Survey Blog|access-date=9 September 2018}}</ref> | |||

| |elevation_m = 1345 | |||

| |population = 71,891,524 | |||

| |population_as_of = 2019 | |||

| |population_footnotes = <ref>{{cite web |url = https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/ |title = World Population Prospects 2017 |access-date = 26 May 2017 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20160927210437/https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/ |archive-date = 27 September 2016 |url-status = dead}}</ref> | |||

| |density_km2 = 216 | |||

| |languages = ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| |timezone1 = ] / ] | |||

| |utc_offset1 = ±0{{!}}UTC | |||

| |timezone1_DST = ]{{ref label|footnote_a|a}} | |||

| |utc_offset1_DST = +1 | |||

| |additional_info = {{Infobox |child=yes |label1 = Drives on the |data1 = left}} | |||

| |footnotes = {{Ordered list|list_style_type=lower-alpha|item_style=font-size:90%; | |||

| |{{note|footnote_a}} ] in the Republic of Ireland, ] in the United Kingdom and associated territories. | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| The '''British Isles''' are an ] in the ] off the north-western coast of ], consisting of the islands of ], ], the ], the ] and ] ], the ] (] and ]), and over six thousand smaller islands.<ref name="Britannica-2023">{{Cite web |date=12 May 2023 |title=British Isles |url=https://www.britannica.com/place/British-Isles |access-date=26 May 2023 |website=]}}</ref> They have a total area of {{convert|315159|km2||abbr=on}}<ref name="UNEP" /> and a combined population of almost 72 million, and include two ]s, the ] (which covers roughly five-sixths of Ireland),<ref>The diplomatic and constitutional name of the Irish state is simply ''Ireland''. For disambiguation purposes, ''Republic of Ireland'' is often used although technically not the name of the state but, according to the ''] 1948'', the state "may be described" as such.</ref> and the ]. The ], off the north coast of ], are normally taken to be part of the British Isles,<ref>Oxford English Dictionary: "British Isles: a geographical term for the islands comprising Great Britain and Ireland with all their offshore islands including the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands."</ref> even though geographically they do not form part of the ].<ref>{{Cite book |last1 = Alan |first1 = Lew |last2 = Colin |first2 = Hall |last3 = Dallen |first3 = Timothy|title = World Geography of Travel and Tourism: A Regional Approach |publisher=Elsevier |place = Oxford |year = 2008 |quote = The British Isles comprise more than 6,000 islands off the north-west coast of continental Europe, including the countries of the United Kingdom of Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales) and Northern Ireland, and the Republic of Ireland. The group also includes the United Kingdom crown dependencies of the Isle of Man, and by tradition, the Channel Islands (the Bailiwicks of Guernsey and Jersey), even though these islands are strictly speaking an archipelago immediately off the coast of Normandy (France) rather than part of the British Isles. |isbn = 978-0-7506-7978-7}}</ref> Under the UK Interpretation Act 1978, the Channel Islands are clarified as forming part of the ],<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.statutelaw.gov.uk/content.aspx?activeTextDocId=1838152 |title="British Islands" means the United Kingdom, the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man. (1889) |publisher=Statutelaw.gov.uk |access-date=4 October 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090507182642/http://www.statutelaw.gov.uk/content.aspx?activeTextDocId=1838152 |archive-date=7 May 2009}}</ref> not to be confused with the British Isles. | |||

| {{dablink|This article explains the archipelago in north-western Europe. For those areas of the archipelago with constitutional links to the British monarchy, see ].}} | |||

| The oldest rocks are 2.7 billion years old and are found in Ireland, Wales and the north-west of Scotland.<ref>{{Cite book| last=Woodcock| first=Nigel H.|author2=Rob Strachan| title=Geological History of Britain and Ireland| year=2012| publisher=John Wiley & Sons| isbn = 978-1-1182-7403-3| pages=49–50}}</ref> During the ] period, the north-western regions collided with the south-east, which had been part of a separate continental landmass. The topography of the islands is modest in scale by global standards. ], the highest mountain, rises to only {{convert|1345|m}},<ref name="Ordnance Survey Blog-2016" /> and ], which is notably larger than other lakes in the island group, covers {{convert|151|sqmi|km2|order=flip}}. The climate is temperate marine, with cool winters and warm summers. The ] brings significant moisture and raises temperatures {{convert|11|C-change||abbr=on}} above the global average for the latitude. This led to a landscape that was long dominated by temperate rainforest, although human activity has since cleared the vast majority of ]. The region was re-inhabited after the last glacial period of ], by 12,000 BC, when Great Britain was still part of a peninsula of the European continent. Ireland may have been connected to Great Britain by way of an ] before 14,000 BC, and was not inhabited until after 8000 BC.<ref name="Edwards-2008">{{cite journal|last1=Edwards |first1=R.J. |last2=Brooks |first2=A.J. |date=2008 |title=The Island of Ireland: Drowning the Myth of an Irish Land-bridge? |editor=Davenport, J.J. |editor2=Sleeman, D.P. |editor3=Woodman, P.C. |journal=The Irish Naturalists' Journal |pages=19–34}}</ref> Great Britain became an island by 7000 BC with the flooding of ].<ref name="McGreevy-2020">{{cite web |last1=McGreevy |first1=Nora |date=2 December 2020 |title=Study Rewrites History of Ancient Land Bridge Between Britain and Europe |url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/tiny-islands-survived-tsunami-almost-separated-britain-europe-study-finds-180976430/ |access-date=31 March 2022 |work=]}}</ref> | |||

| {{Infobox Islands | |||

| |name = British Isles | |||

| |image name = LocationBritishIsles.png | |||

| |image caption = The British Isles in relation to mainland Europe | |||

| |location = ] | |||

| |coordinates = | |||

| |area = 315,134 km² | |||

| 121,673 sq mi | |||

| |total islands = 6,000+ | |||

| |major islands = ] and ] | |||

| |highest mount = ] | |||

| |elevation = 1,344 m (4,409 ft) | |||

| |country = Guernsey | |||

| |country largest city = ] | |||

| |country 1 = Isle of Man | |||

| |country 1 largest city = ] | |||

| |country 2 = Ireland | |||

| |country 2 largest city = ] | |||

| |country 3 = Jersey | |||

| |country 3 largest city = ] | |||

| |country 4 = United Kingdom | |||

| |country 4 largest city = ] | |||

| |density = | |||

| |population = ~65 million | |||

| |ethnic groups = ], ], ], ], ], ], ]<ref>{{ cite web |last=National Statistics Office |first= |title=Ethnic group statistics A guide for the collection and classification of ethnicity data |publisher=] |date=2003 |url=http://www.statistics.gov.uk/about/ethnic_group_statistics/downloads/ethnic_group_statistics.pdf }}</ref>, ], ] | |||

| }} | |||

| The '''British Isles''' ({{lang-ga|Na hOileáin Bhriotanacha}},<ref>''Na hOileáin Bhriotanacha'' from ''CollinsHapper Pocket Irish Dictionary'' (ISBN 0-00-470765-6). ''Oileáin Iarthair Eorpa'' meaning ''Islands of Western Europe'' from Patrick S. ''Dineen, Foclóir Gaeilge Béarla, Irish-English Dictionary'', Dublin, 1927. ''Éire agus an Bhreatain Mhór'', meaning ''Ireland and Great Britain'' (from focail.ie, "", Foras na Gaeilge, 2006)</ref> {{lang-gv|Ellanyn Goaldagh}}, {{lang-gd|Eileanan Breatannach}}, {{lang-cy|Ynysoedd Prydain}}) are a group of ] off the northwest coast of ] comprising ], ] and a number of smaller islands.<ref>"British Isles," '']''</ref> Although globally widely used, the term ''British Isles'' is ] in relation to ], where many people may find the term offensive or objectionable<ref> Myers, Kevin; The ] (subscription needed) 09/03/2000, Accessed July 2006 'millions of people from these islands — 'oh how angry we get when people call them the British Isles' <br> | |||

| The ] (Ireland), ] (northern Great Britain) and ] (southern Great Britain), all speaking ],<ref>{{cite book |last=Koch |first=John C |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=f899xH_quaMC&pg=PA973 |title=Celtic Culture: Aberdeen breviary-celticism |publisher=ABC-CLIO |year=2006 |isbn=9781851094400}}</ref> inhabited the islands at the beginning of the 1st millennium BC. Much of Brittonic-occupied Britain was ] from AD 43. The first ] arrived as Roman power waned in the 5th century, and eventually they dominated the bulk of what is now England.<ref>British Have Changed Little Since Ice Age, Gene Study SaysJames Owen for National Geographic News, 19 July 2005 .</ref> ] invasions began in the 9th century, followed by more permanent settlements and political change, particularly in England. The ] conquest of England in 1066 and the later ] partial conquest of Ireland from 1169 led to the imposition of a new Norman ruling elite across much of Britain and parts of Ireland. By the ], Great Britain was separated into the Kingdom of England and Kingdom of Scotland, while control in Ireland fluxed between ], ] and the English-dominated ], soon restricted only to ]. The 1603 ], ] and ] aimed to consolidate Great Britain and Ireland into a single political unit, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, with the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands remaining as ]. The expansion of the British Empire and migrations following the ] and ] resulted in the dispersal of some of the islands' population and culture throughout the world, and rapid depopulation of Ireland in the second half of the 19th century. Most of Ireland seceded from the United Kingdom after the ] and the subsequent ] (1919–1922), with six counties remaining in the UK as Northern Ireland. | |||

| Diarmaid MacCulloch, The Reformation: Europe's House Divided 1490-1700. (London: Penguin/Allen Lane, 2003): “the collection of islands which embraces England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales has commonly been known as the British Isles. '''This title no longer pleases all the inhabitants of the islands''', and a more neutral description is ‘the Atlantic Isles’” (p. xxvi)<br> | |||

| As a term, "British Isles" is a ] name and not a political unit. In Ireland, the term is ],<ref name="Britannica-2023"/><ref>{{Cite book |last1=Payne |first1=Malcolm |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rasBRQwwOIIC&pg=PA7 |title=Social Work in the British Isles |last2=Shardlow |first2=Steven |publisher=] |year=2002 |isbn=978-1-85302-833-5 |pages=7 |quote=When we think about social work in the British Isles, a contentious term if ever there was one, what do we expect to see?}}</ref> and there are objections to its usage.<ref name="Davies-2000">{{Citation|first1=Alistair|last1=Davies|first2=Alan|last2=Sinfield|title=British Culture of the Postwar: An Introduction to Literature and Society, 1945–1999|publisher=Routledge|year=2000|isbn=978-0-415-12811-7|page=|quote=Some of the Irish dislike the 'British' in 'British Isles', while a minority of the Welsh and Scottish are not keen on 'Great Britain'. ... In response to these difficulties, 'Britain and Ireland' is becoming preferred official usage if not in the vernacular, although there is a growing trend amongst some critics to refer to Britain and Ireland as 'the archipelago'.|url=https://archive.org/details/britishcultureof00adav/page/9}}</ref> The ] does not officially recognise the term,<ref name="Dáil Éireann-2012">" {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121006211200/http://www.oireachtas-debates.gov.ie/D/0606/D.0606.200509280360.html |date=6 October 2012}}, ], Volume 606, 28 September 2005. In his response, the Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs stated that "The British Isles is not an officially recognised term in any legal or inter-governmental sense. It is without any official status. The Government, including the Department of Foreign Affairs, does not use this term. Our officials in the Embassy of Ireland, London, continue to monitor the media in Britain for any abuse of the official terms as set out in the Constitution of Ireland and in legislation. These include the name of the State, the President, ] and others."</ref> and its embassy in London discourages its use.<ref>{{Citation|date=3 October 2006|first=David|last=Sharrock|url=http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/europe/article658099.ece|work=]|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070216021615/http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/europe/article658099.ece|archive-date=16 February 2007|location=UK |title=New atlas lets Ireland slip shackles of Britain|access-date=24 April 2020|quote=A spokesman for the Irish Embassy in London said: 'The British Isles has a dated ring to it as if we are still part of the Empire. We are independent, we are not part of Britain, not even in geographical terms. We would discourage its useage {{sic}}.'}}</ref> "Britain and Ireland" is used as an alternative description,<ref name="Davies-2000"/><ref name="Hazlett-2003">{{Cite book| title = The Reformation in Britain and Ireland: an introduction |isbn = 978-0-567-08280-0 |page = 17 |last = Hazlett |first = Ian |year = 2003 |publisher=Continuum International Publishing Group |quote=At the outset, it should be stated that while the expression 'The British Isles' is evidently still commonly employed, its intermittent use throughout this work is only in the geographic sense, in so far as that is acceptable. Since the early twentieth century, that nomenclature has been regarded by some as increasingly less usable. It has been perceived as cloaking the idea of a 'greater England', or an extended south-eastern English imperium, under a common Crown since 1603 onwards. ... Nowadays, however, 'Britain and Ireland' is the more favoured expression, though there are problems with that too. ... There is no consensus on the matter, inevitably. It is unlikely that the ultimate in non-partisanship that has recently appeared the (East) 'Atlantic Archipelago' will have any appeal beyond captious scholars.}}</ref><ref>{{Citation |title=Guardian Style Guide |date=19 December 2008 |url=https://www.theguardian.com/styleguide/b |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230524041755/https://www.theguardian.com/guardian-observer-style-guide-b |location=London |work=] |quote=A geographical term taken to mean Great Britain, Ireland and some or all of the adjacent islands such as Orkney, Shetland and the Isle of Man. The phrase is best avoided, given its (understandable) unpopularity in the Irish Republic. The plate in the National Geographic Atlas of the World once titled British Isles now reads Britain and Ireland. |archive-date=24 May 2023}}</ref> and "Atlantic Archipelago" has also seen limited use in academia.<ref name="Norquay-2002">{{Citation|first1=Glenda|last1=Norquay|first2=Gerry| last2=Smyth |title=Across the margins: cultural identity and change in the Atlantic archipelago |publisher=Manchester University Press|year=2002|isbn=978-0-7190-5749-6|page=4 |quote=The term we favour here—Atlantic Archipelago—may prove to be of no greater use in the long run, but at this stage, it does at least have the merit of questioning the ideology underpinning more established nomenclature.}}</ref><ref name="Schwyzer-2004">{{Citation|first1=Philip|last1=Schwyzer|first2=Simon| last2=Mealor |title=Archipelagic identities: literature and identity in the Atlantic Archipelago |publisher=Ashgate Publishing|year=2004 |isbn=978-0-7546-3584-0|page=10 |quote=In some ways 'Atlantic Archipelago' is intended to do the work of including without excluding, and while it seems to have taken root in terms of academic conferences and publishing, I don't see it catching on in popular discourse or official political circles, at least not in a hurry.}}</ref><ref name="Kumar-2003">{{Citation|first=Krishan|last=Kumar|title=The Making of English National Identity |publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=2003 |isbn=978-0-521-77736-0|page=6 |quote=Some scholars, seeking to avoid the political and ethnic connotations of 'the British Isles', have proposed the 'Atlantic Archipelago' or even 'the East Atlantic Archipelago' (see, e.g. Pocock 1975a: 606; 1995: 292n; Tompson, 1986) Not surprisingly this does not seem to have caught on with the general public, though it has found increasing favour with scholars promoting the new 'British History'.}}</ref><ref name="Michael Braddick-2002">{{Citation|author1=David Armitage|author2-link=Michael Braddick |author2=Michael Braddick |title=The British Atlantic world, 1500–1800 |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan |year=2002 |isbn=978-0-333-96340-1|page=284 |quote=British and Irish historians increasingly use 'Atlantic archipelago' as a less metro-centric term for what is popularly known as the British Isles.}}</ref> In official documents created jointly by Ireland and the United Kingdom, such as the ], the term "these islands" is used.<ref name="Marshall Cavendish-2010"/><ref>{{Cite web |title=CAIN: Events: Peace: The Agreement - Agreement reached in the multi-party negotiations (10 April 1998) |url=https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/events/peace/docs/agreement.htm |access-date=19 April 2023 |website=cain.ulster.ac.uk}}</ref> | |||

| On ] ] questioned the use of ''British Isles'' as a purely geographic expression, noting: | |||

| <blockquote> "Last Post has redoubled its efforts to re-educate those labouring under the misconception that Ireland is really just British. When British Retail Week magazine last week reported that a retailer was to make its British Isles debut in Dublin, we were puzzled. Is not Dublin the capital of the Republic of Ireland?. When Last Post suggested the magazine might see its way clear to correcting the error, an educative e-mail to the publication...: </blockquote>Retrieved ] ]<br> | |||

| "...I have called the Atlantic archipelago – since '''the term ‘British Isles’ is one which Irishmen reject and Englishmen decline to take quite seriously'''." Pocock, J.G.A. (2005). The Discovery of Islands. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 29.<br> | |||

| "...what used to be called the "British Isles," although that is now a ] term." Finnegan, Richard B.; Edward T. McCarron (2000). Ireland: Historical Echoes, Contemporary Politics. Boulder: Westview Press, p. 358.<br> | |||

| ==Etymology== | |||

| "In an attempt to coin a term that avoided '''the 'British Isles' - a term often offensive to Irish sensibilities''' - Pocock suggested a neutral geographical term for the collection of islands located off the northwest coast of continental Europe which included Britain and Ireland: the Atlantic archipelago..." Lambert, Peter; Phillipp Schofield (2004). Making History: An Introduction to the History and Practices of a Discipline. New York: Routledge, p. 217.<br> | |||

| {{Main|Britain (place name)|Names of the British Isles|Terminology of the British Isles}} | |||

| The earliest known references to the islands as a group appeared in the writings of seafarers from the ancient Greek colony of ].<ref name="OCorrain-2001">], p. 1.</ref><ref name="ReferenceA"/> The original records have been lost; however, later writings, e.g. ]'s '']'', that quoted from the ] (6th century BC) and from ]'s ''On the Ocean'' (around 325–320 BC)<ref>], p. 150.</ref> have survived. | |||

| "..'''the term is increasingly unacceptable to Irish historians in particular''', for whom the Irish sea is or ought to be a separating rather than a linking element. Sensitive to such susceptibilities, proponents of the idea of a genuine British history, a theme which has come to the fore during the last couple of decades, are plumping for a more neutral term to label the scattered islands peripheral to the two major ones of Great Britain and Ireland." Roots, Ivan (1997). "Union or Devolution in Cromwell's Britain". History Review. <br> | |||

| In the 1st century BC, ] has ''Prettanikē nēsos'',<ref name="DiodorusSiculus">Diodorus Siculus' ''Bibliotheca Historica'' Book V. Chapter XXI. Section 1 | |||

| The British Isles, A History of Four Nations, Second edition, Cambridge University Press, July 2006, Preface, Hugh Kearney. "The title of this book is ‘The British Isles’, not ‘Britain’, in order to emphasise the multi-ethnic character of our intertwined histories. Almost inevitably '''many within the Irish Republic find it objectionable''', much as ]s or ]s resent the use of the term ‘Spain’. As Seamus Heaney put it when he objected to being included in an anthology of British Poetry: 'Don’t be surprised If I demur, for, be advised My passport’s green. No glass of ours was ever raised To toast the Queen. (Open Letter, Field day Pamphlet no.2 1983)"<br /> | |||

| at the ].</ref> "the British Island", and ''Prettanoi'',<ref name="DiodorusSiculus-2">Diodorus Siculus' ''Bibliotheca Historica'' Book V. Chapter XXI. Section 2 | |||

| (Note: sections bolded for emphasis do not appear bold in original publications) | |||

| at the ].</ref> "the Britons",<ref name="ReferenceA">], p. 172–174.</ref> describes Julius Caesar as having "advanced the Roman Empire as far as the British Isles" ({{Langx|grc|μέχρι τῶν Βρεττανικῶν νήσων|translit=mékhri tôn Brettanikôn nḗsōn|links=no|label=Greek}}),<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/diodorus-of-sicily-in-twelve-volumes.-vol.-1-loeb-279 |title=Diodorus of Sicily in Twelve Volumes |date= |publisher=] |year=1933 |editor-last=Oldfather |editor-first=Charles Henry |editor-link=Charles Henry Oldfather |series=] 279 |volume=I: Books I – II.34 |location=Cambridge, Massachusetts |pages=20–21 |language=grc, en-US}}</ref> and remarks on the region "about the British Isles" ({{Langx|grc|τὸ περὶ τὰς Βρεττανικὰς νήσους|translit=tò perì tàs Brettanikàs nḗsous|links=no|label=none}}).<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/diodorus-of-sicily-in-twelve-volumes.-vol.-2-loeb-303 |title=Diodorus of Sicily in Twelve Volumes |date= |publisher=] |year=1935 |editor-last=Oldfather |editor-first=Charles Henry |editor-link=Charles Henry Oldfather |series=] 303 |volume=II: Books II.35 – IV.58 |location=Cambridge, Massachusetts |pages=194–195 |language=grc, en-US}}</ref> According to Philip Freeman in 2001, "it seems reasonable, especially at this early point in classical knowledge of the Irish, for Diodorus or his sources to think of all inhabitants of the Brettanic Isles as ''Brettanoi'''''".'''<ref>{{Cite book |last=Freeman |first=Philip |url=https://archive.org/details/irelandclassical0000free |title=Ireland and the Classical World |date= |publisher=] |year=2001 |isbn=978-0-292-72518-8 |location=Austin |pages=36}}</ref> | |||

| </ref>; the Irish government also discourages its use<ref>The Irish Free State/Éire/Republic of Ireland/Ireland: “A Country by Any Other Name”?, Mary E. Daly, Journal of British Studies 46 (January 2007): p 72–90<br /> | |||

| <blockquote>In 1947 Ireland’s Department of External Affairs drafted a letter to the heads of all government departments...... '''The expression “British Isles” was “a complete misnomer and its use should be thoroughly discouraged”; it should be replaced “where necessary by Ireland and Great Britain'''.” | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| <br /> | |||

| , ] - Volume 606 - ] ]. In his response, the Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs stated "The British Isles is not an officially recognised term in any legal or inter-governmental sense. It is without any official status. The ], including the Department of Foreign Affairs, does not use this term. Our officials in the Embassy of Ireland, London, continue to monitor the media in Britain for any abuse of the official terms as set out in the Constitution of Ireland and in legislation. These include the name of the State, the President, ] and others." | |||

| <br /> | |||

| ". The Times, London, October 3, 2006. A spokesman for the Irish Embassy in London said: “The British Isles has a dated ring to it, as if we are still part of the Empire. We are independent, we are not part of Britain, not even in geographical terms. '''We would discourage its usage'''.” | |||

| <br />(Note: Sections bolded for emphasis do not appear in bold in the original publications)</ref>. | |||

| ] used Βρεττανική (''Brettanike''),<ref name="Strabo">Strabo's ''Geography'' Book I. Chapter IV. Section 2 and at the ].</ref><ref name="Strabo-2">Strabo's ''Geography'' Book IV. Chapter II. Section 1 and at the ].</ref><ref name="Strabo-3">Strabo's ''Geography'' Book IV. Chapter IV. Section 1 and at the ].</ref> and ], in his ''Periplus maris exteri'', used αἱ Πρεττανικαί νῆσοι (''the Prettanic Isles'') to refer to the islands.<ref name="Müller-1855">{{cite book|title=Geographi Graeci Minores|volume= 1|chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/geographigraeci03mlgoog|author1=Marcianus Heracleensis|last2=Müller|first2=Karl|author-link2=Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller|chapter=Periplus Maris Exteri, Liber Prior, Prooemium| pages=516–517|editor1-last=Firmin Didot|editor1-first=Ambrosio|location=Paris|year=1855|display-authors=etal|author1-link= Marcian of Heraclea|publisher= editore Firmin Didot}} Greek text and Latin Translation thereof archived at the ] Project.{{DjVulink}}</ref> | |||

| There are two ]s located on the islands: the ] and ].<ref>The diplomatic and constitutional name of the Irish state is simply ''Ireland''. For disambiguation purposes "Republic of Ireland" is often used though technically that is not the name of the state but, according to the ''] 1948,'' its "description". ''Article 4, Bunreacht na hÉireann. Section 2, Republic of Ireland Act, 1948.''</ref> The group also includes the ] of the ] and, by tradition, the ], although the latter are not ] a part of the archipelago.<ref><br/>Collier's Encyclopedia, 1997 Edition<br/>Don Aitken, "", February 2002<br/>{{blockquote|Usage is not consistent as to whether the Channel Islands are included - geographically they should not be, politically they should.}}</ref> There are other ] surrounding the extent, names and geographical elements of the islands. | |||

| According to ] and Colin Smith in 1979 "the earliest instance of the name which is textually known to us" is in ] of ], who referred to them {{Langx|grc|αἱ Βρεταννικαί νήσοι|translit=hai Bretannikai nēsoi|label=as|lit=the Brettanic Islands' or 'the British Isles}}.<ref name="Rivet-1979">{{Cite book |last1=Rivet |first1=A. L. F. |author-link=A. L. F. Rivet |url=http://archive.org/details/placenamesofroma0000rive |title=The place-names of Roman Britain |last2=Smith |first2=Colin |publisher=] |year=1979 |isbn=978-0-691-03953-4 |pages=282}}</ref> According to Rivet and Smith, this name encompassed "Britain with Ireland".<ref name="Rivet-1979" /> According to ] in 2018, the British Isles was "a concept already present in the minds of those living in continental Europe since at least the 2nd–cent. CE".<ref>{{Cite book |last=O'Loughlin |first=Thomas |author-link=Thomas O'Loughlin |title=Brill Encyclopedia of Early Christianity |year=2018 |edition=Online |volume=4 (Isi - Ori) |chapter=Ireland |doi=10.1163/2589-7993_EECO_SIM_00001698 |issn=2589-7993 |chapter-url=https://doi.org/10.1163/2589-7993_EECO_SIM_00001698}}</ref> | |||

| ==Alternative names and descriptions== | |||

| {{main|British Isles (terminology)|British Isles naming dispute}} | |||

| Several different names are currently used to describe the islands. | |||

| Historians today, though not in absolute agreement, largely agree that these Greek and Latin names were probably drawn from native ] names for the archipelago.<ref>], p. 47.</ref> Along these lines, the inhabitants of the islands were called the Πρεττανοί ('']'' or ''Pretani'').<ref name="ReferenceA" /><ref>], p. 68.</ref> The shift from the "P" of ''Pretannia'' to the "B" of '']'' by the Romans occurred during the time of Julius Caesar.<ref name="Snyder-2003">], p. 12.</ref> | |||

| Dictionaries, encyclopaedias and atlases that use the term ''British Isles'' define it<ref>''Longman Modern English Dictionary'' - "a group of islands off N.W. Europe comprising Great Britain Ireland, the Hebrides, Orkney the Shetland Is and adjacent islands"</ref><ref> - ''"Function: geographical name, island group W Europe comprising Great Britain, Ireland, & adjacent islands"''</ref><ref> - includes for example the ''American Heritage Dictionary'' - ''"British Isles, A group of islands off the northwest coast of Europe comprising Great Britain, Ireland, and adjacent smaller islands"''</ref><ref> - ''"British Isles, group of islands in the northeastern Atlantic, separated from mainland Europe by the North Sea and the English Channel. It consists of the large islands of Great Britain and Ireland and almost 5,000 surrounding smaller islands and islets"''</ref><ref>''Philip's World Atlas''</ref><ref>''Times Atlas of the World''</ref><ref>''Insight Family World Atlas''</ref> | |||

| as Great Britain, Ireland and adjacent islands, typically including the Isle of Man, the Hebrides, Shetland, Orkney. Some definitions include the Channel Islands.<ref>OED Online: "a geographical term for the islands comprising Great Britain and Ireland with all their offshore islands including the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands"</ref><ref></ref><ref></ref><ref>''Philips University Atlas''</ref> | |||

| ] ] referred to the larger island as ''great Britain'' (μεγάλη Βρεττανία ''megale Brettania'') and to Ireland as ''little Britain'' (μικρὰ Βρεττανία ''mikra Brettania'') in his work '']'' (147–148 AD).<ref>{{cite book |title=Claudii Ptolemaei Opera quae exstant omnia (Syntaxis Mathematica) |author=Claudius Ptolemy |author-link=Ptolemy |editor1-last=Heiberg |editor1-first=J.L. |publisher=in aedibus B. G. Teubneri |location=Leipzig |year=1898|volume=1 |chapter-url=http://www.wilbourhall.org/pdfs/HeibergAlmagestComplete.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://www.wilbourhall.org/pdfs/HeibergAlmagestComplete.pdf |archive-date=9 October 2022 |url-status=live |pages=112–113 |chapter=Ἕκθεσις τῶν κατὰ παράλληλον ἰδιωμάτων: κβ', κε'}}</ref> According to Philip Freeman in 2001, Ptolemy "is the only ancient writer to use the name "Little Britain" for Ireland, though in doing so he is well within the tradition of earlier authors who pair a smaller Ireland with a larger Britain as the two Brettanic Isles".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Freeman |first=Philip |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZSHhfOM-5AEC&pg=PA65 |title=Ireland and the Classical World |publisher=University of Texas Press |year=2001 |isbn=978-0-292-72518-8 |location=Austin, Texas |page=65}}</ref> In the second book of Ptolemy's '']'' ({{Circa|150 AD}}), the second and third chapters are respectively titled in {{Langx|grc|Κεφ. βʹ Ἰουερνίας νήσου Βρεττανικῆς θέσις|lit=Ch. 2, position of Hibernia, a British island|label=Greek|links=no|translit=Iouernías nḗsou Brettanikê̄s thésis}} and {{Langx|grc|Κεφ. γʹ Ἀλβουίωνος νήσου Βρεττανικῆς θέσις|lit=Ch. 3, position of Albion, a British island|label=none|translit=Albouíōnos nḗsou Brettanikê̄s thésis}}.<ref>{{Cite book |last= |first= |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0RivEAAAQBAJ |title=Klaudios Ptolemaios. Handbuch der Geographie: 1. Teilband: Einleitung und Buch 1-4 & 2. Teilband: Buch 5-8 und Indices |publisher=Schwabe Verlag (Basel) |year=2017 |isbn=978-3-7965-3703-5 |editor-last=Stückelberger |editor-first=Alfred |edition=2nd |language=grc, de |orig-date=2006 |editor-last2=Grasshoff |editor-first2=Gerd}}</ref>{{Rp|pages=143, 146}} | |||

| Many major road and rail maps and atlases use the term "Great Britain and Ireland" to describe the islands, although this may be ambiguous regarding the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands.<ref></ref><ref></ref><ref></ref><ref>Hammond International Great Britain, Ireland</ref> Another alternative name is "British-Irish Isles".<ref>John Oakland, 2003, , Routledge: London<br/> | |||

| <blockquote>'''British-Irish Isles, the''' (geography) see BRITISH ISLES</blockquote> | |||

| <blockquote>'''British Isles, the''' (geography) A geographical (not political or CONSTITUTIONAL) term for ENGLAND, SCOTLAND, WALES, and IRELAND (including the REPUBLIC OF IRELAND), together with all offshore islands. A more accurate (and politically acceptable) term today is the British-Irish Isles.</blockquote></ref> | |||

| In ] ], the British Isles are known as {{transl|ar|Jazāʾir Barṭāniya}} or {{transl|ar|Jazāʾir Barṭīniya}}. Arabic geographies, including the ''{{transliteration|ar|ALA|]}}'' of ], mention the British Isles as twelve islands.<ref name="Dunlop-1971">{{Cite book |last=Dunlop |first=D. M. |author-link=Douglas Morton Dunlop |url=http://archive.org/details/arabcivilization0000dunl |title=Arab Civilization to A.D. 1500 |publisher=] and {{ill|Librairie du Liban|WD=Q55091753}} |year=1971 |isbn=978-0-582-50273-4 |location=Beirut and London |pages=160}}</ref><ref name="Dunlop-1957">{{Cite journal |last=Dunlop |first=D. M. |author-link=Douglas Morton Dunlop |date=April 1957 |title=The British Isles according to medieval Arabic authors |journal=] |volume=IV |issue=1 |pages=11–28}}</ref> | |||

| In addition, the term "British Isles" is itself used in widely varying ways, including as an effective synonym for the UK or for Great Britain and its islands, but excluding Ireland.<ref> This BBC article referred to 'a small '''country''' such as the British Isles' between at least April 2004 and January 2007 (checked using the Wayback Machine at http://web.archive.org. Last accessed and checked 01/01/07. It was changed in February 2007 and now reads 'a small '''area''' such as the British Isles'</ref><ref>" Website on Megalithic Monuments in the British Isles and Ireland. Ireland in this site includes Fermanagh, which is politically in Northern Ireland."</ref><ref>" The website uses the term "British Isles" in various ways, including ways that use Ireland as all of Ireland, while simultaneously using the term "The British Isles and Ireland", e.g. 'Anyone using GENUKI should remember that its name is somewhat misleading -- the website actually covers the British Isles and Ireland, rather than just the United Kingdom, and therefore includes information about the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man, as well as England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland.'"</ref><ref>"{{PDFlink||575 ]<!-- application/pdf, 589668 bytes -->}} which includes Belfast lines under the section on Ireland."</ref><ref> For example, see Google searches of | |||

| .</ref> Media organisations like the '']'' and the ] have style-guide entries to try to maintain consistent usage,<ref>{{PDFlink||275 ]<!-- application/pdf, 282573 bytes -->}} | |||

| ''"The British Isles is not a political entity. It is a geographical unit, the archipelago off the west coast of continental Europe covering Scotland, Wales, England, Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland, the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands."''</ref><ref> | |||

| ''"Britain or Great Britain = England, Wales, Scotland and islands governed from the mainland (i.e. not Isle of Man or Channel Islands). United Kingdom = Great Britain and Northern Ireland. British Isles = United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland, Isle of Man and Channel Islands. Do not confuse these entities."''</ref> but these are not always successful. | |||

| ]'s English translation of Diodorus Siculus's {{Langx|la|]|label=none}}, written in the middle 1480s, mentions the British Isles as {{Lang|enm|the yles of Bretayne}}.<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-7tQAQAAMAAJ |title=The Bibliotheca Historica of Diodorus Siculus translated by John Skelton |publisher=] |year=1955 |editor-last=Salter |editor-first=F. M. |series=Early English Text Society Original Series 233 |volume=I: Text |pages=11 |editor-last2=Edwards |editor-first2=H. L. R.}}</ref> ]'s English translation of ]'s {{Langx|la|Orbis descriptio|label=none}}, published in 1572, mentions the British Isles as {{Lang|enm|the Iles of Britannia}}.<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A20492.0001.001 |title=The surueye of the vvorld, or situation of the earth, so muche as is inhabited Comprysing briefely the generall partes thereof, with the names both new and olde, of the principal countries, kingdoms, peoples, cities, towns, portes, promontories, hils, woods, mountains, valleyes, riuers and fountains therin conteyned. Also of seas, with their clyffes, reaches, turnings, elbows, quicksands, rocks, flattes, shelues and shoares. A work very necessary and delectable for students of geographie, saylers, and others. First vvritten in Greeke by Dionise Alexandrine, and novv englished by Thomas Twine, Gentl. |date= |publisher=] |year=1572 |language=enm |translator-last=Twyne |translator-first=Thomas |translator-link=Thomas Twyne}}</ref> The earliest citation of the phrase {{Lang|enm|Brytish Iles}} in the '']'' is in a work by ] dated 1577.<ref name="JohnDee-1577">John Dee, 1577. 1577 J. ''Arte Navigation'', p. 65 "The syncere Intent, and faythfull Aduise, of Georgius Gemistus Pletho, was, I could..frame and shape very much of Gemistus those his two Greek Orations..for our Brytish Iles, and in better and more allowable manner." From the OED, s.v. "British Isles"</ref> | |||

| ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', the Oxford University Press - publishers of the ''Oxford English Dictionary'' - and the UK Hydrographic Office (publisher of Admiralty charts) have all occasionally used the term "British Isles and Ireland" (with ''Britannica'' and Oxford contradicting their own definitions of the "British Isles"),<ref>{{PDFlink||1.00 ]<!-- application/pdf, 1055583 bytes -->}} Notice to Mariners of 2005 referring to a new edition of a nautical chart of the Western Approaches. Chart 2723 INT1605 International Chart Series, British Isles & Ireland, Western Approaches to the North Channel.</ref><ref>" Thus, the Gulf Stream–North Atlantic–Norway Current brings warm tropical waters northward, warming the climates of eastern North America, the British Isles and Ireland, and the Atlantic coast of Norway in winter, and the Kuroshio–North Pacific Current does the same for Japan and western North America, where warmer winter climates also occur. Page retrieved Feb eighteenth 2007.</ref><ref>" The description of the OUP textbook "The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries" in the series on the history of the British Isles carries the description that it 'Offers an integrated geographical coverage of the whole of the British Isles and Ireland - rather than purely English history'" The same blurb goes on to say that the "book encompasses the histories of England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, and also considers the relationships between the different parts of the British Isles". Page retrieved Feb eighteenth 2007.</ref> and some specialist encyclopedias also use that term.<ref>" Illustrated Encyclopedia of Trees by David More and John White, Timber Press, Inc., 2002, "This book began and for many years quietly proceeded as DM's (David Martin's) personal project to record in detail as many tree species, varieties and cultivars as he could find in the British Isles and Ireland."</ref> The BBC style guide's entry on the subject of the British Isles remarks, "Confused already? Keep going." The Economic History Society style guide suggests that the term should be avoided.<ref></ref> | |||

| Other names used to describe the islands include the ''] Isles'', ''Atlantic archipelago'' (a term coined by the historian ] in 1975<ref>{{Citation|title=Demography of immigrants and minority groups in the United Kingdom: proceedings of the eighteenth annual symposium of the Eugenics Society, London |issue=1981 |author=D. A. Coleman|publisher=Academic Press|year=1982|isbn=978-0-12-179780-5|page=213|quote=The geographical term ''British Isles'' is not generally acceptable in Ireland, the term ''these islands'' being widely used instead. I prefer ''the Anglo-Celtic Isles'', or ''the North-West European Archipelago''.}}</ref><ref>{{Citation|title=Irish historical studies: Joint Journal of the Irish Historical Society and the Ulster Society for Irish Historical Studies|publisher=Hodges, Figgis & Co.|year=1990|page=98|quote=There is mug to be said for considering the archipelago as a whole, for a history of the British or Anglo-Celtic isles or 'these islands'.}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |first=J. G. A. |last=Pocock |author-link=J. G. A. Pocock |title=British history: a plea for a new subject |journal=Journal of Modern History |volume=47 |issue=4 |year=1975 |pages=601–21 (606) |doi=10.1086/241367 |s2cid=143575698 |quote=We should start with what I have called the Atlantic archipelago – since the term 'British Isles' is one which Irishmen reject and Englishmen decline to take quite seriously.}}</ref>), ''British-Irish Isles'',<ref>John Oakland, 2003, , Routledge: London | |||

| Other descriptions for the islands are also used in everyday language, examples are: "Great Britain and Ireland", "UK and Ireland", and "the British Isles and Ireland". Some of these are used by corporate entities and can be seen on the internet, such as in the naming of Yahoo UK & Ireland,<ref></ref> or such as in the 2001 renaming of the British Isles Rugby Union Team to the current name of the "]". | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| '''British-Irish Isles, the''' (geography) see British Isles | |||

| As mentioned above, the term "British Isles" is controversial in relation to Ireland. One map publisher recently decided to abandon using the term in Ireland while continuing to use it in Britain.<ref>The Irish Times, "", October 2, 2006</ref><ref></ref> The Irish government is opposed to the term "British Isles" and says that it "would discourage its usage".<ref>The Times, "", October 3, 2006</ref> | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| '''British Isles, the''' (geography) A geographical (not political or constitutional) term for England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland (including the Republic of Ireland), together with all offshore islands. A more accurate (and politically acceptable) term today is the British-Irish Isles. | |||

| </blockquote></ref> ''Britain and Ireland'', ''UK and Ireland'', and ''British Isles and Ireland''.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.blackwellreference.com/public/tocnode?id=g9781405129923_toclevel_ss1-14 |title=Blackwellreference.com |publisher=Blackwellreference.com |access-date=7 November 2010}}</ref> | |||

| Owing to political and national associations with the word ''British'', the Government of Ireland does not use the term ''British Isles''<ref name="Dáil Éireann-2012"/> and in documents drawn up jointly between the British and Irish governments, the archipelago is referred to simply as "these islands".<ref name="Marshall Cavendish-2010">{{Citation|title=World and its Peoples: Ireland and United Kingdom|page=8|publisher=Marshall Cavendish|location=London|year=2010|quote=The nomenclature of Great Britain and Ireland and the status of the different parts of the archipelago are often confused by people in other parts of the world. The name British Isles is commonly used by geographers for the archipelago; in the Republic of Ireland, however, this name is considered to be exclusionary. In the Republic of Ireland, the name British-Irish Isles is occasionally used. However, the term British-Irish Isles is not recognized by international geographers. In all documents jointly drawn up by the British and Irish governments, the archipelago is simply referred to as "these islands". The name British Isles remains the only generally accepted term for the archipelago off the north-western coast of mainland Europe.}}</ref> British Isles is the most widely accepted term for the archipelago.<ref name="Marshall Cavendish-2010"/> | |||

| ==Geography== | ==Geography== | ||

| {{ |

{{See also|Geography of England|Geography of Wales|Geography of Scotland|Geography of Ireland|Geography of the United Kingdom|Geography of the Isle of Man|Geography of the Channel Islands}} | ||

| ] and ]); close to the coast of ]]] | |||

| ] ]]] | |||

| There are ] in the group, the largest two being ] and ]. Great Britain is to the east and covers 216,777 km² (83,698 square miles), over half of the total landmass of the group. Ireland is to the west and covers 84,406 km² (32,589 square miles). The largest of the other islands are to be found in the ], ] and ] to the north, ] and the Isle of Man between Great Britain and Ireland, and the ] near the coast of ]. | |||

| The British Isles lie at the juncture of several regions with past episodes of tectonic mountain building. These ] form a complex geology that records a huge and varied span of Earth's history.<ref>{{Cite book| last=Goudie| first=Andrew S.|author2=D. Brunsden| title=The Environment of the British Isles, an Atlas| year=1994| publisher=Clarendon Press| location=Oxford| page=2}}</ref> Of particular note was the ] during the ] and ] periods, when the ] ] collided with the ] ] to form the mountains and hills in northern Britain and Ireland. Baltica formed roughly the north-western half of Ireland and Scotland. Further collisions caused the ] in the ] and ] periods, forming the hills of ], south-west England, and southern Wales. Over the last 500 million years the land that forms the islands has drifted north-west from around 30°S, crossing the ] around 370 million years ago to reach its present northern latitude.<ref><!--Goudie, ''The Environment of the British Isles, an Atlas''-->Ibid., p. 5.</ref> | |||

| The larger islands that constitute the British Isles include: | |||

| The islands have been shaped by numerous glaciations during the ], the most recent being the ].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Jacobi |first1=Roger |last2=Higham |first2=Tom |title=12 - The Later Upper Palaeolithic Recolonisation of Britain: New Results from AMS Radiocarbon Dating |doi=10.1016/b978-0-444-53597-9.00012-1 |publisher=Elsevier |journal=Developments in Quaternary Sciences}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Bradley |first1=Raymond S. |title=Paleoclimatology |chapter=Insects and Other Biological Evidence from Continental Regions |edition=Third |date=2015 |pages=377–404 |doi=10.1016/b978-0-12-386913-5.00011-9 |publisher=Academic Press |isbn=9780123869135}}</ref> As this ended, the central ] was deglaciated and the English Channel flooded, with sea levels rising to current levels some 8,000 years ago, leaving the British Isles in their current form. | |||

| *clockwise around ] from the north: | |||

| ** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** Portsmouth Islands | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** Islands of the ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| ** Islands in ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| **** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| **** ] | |||

| There are about ] in the group, the largest two being Great Britain and Ireland. Great Britain is to the east and covers {{convert|83,700|sqmi|km2|abbr=on}}.<ref name="Calder-1995">{{cite web |last=Calder |first=Joshua |title=100 Largest Islands of the World |url=http://www.worldislandinfo.com/LARGESTV1.html |website=WorldIslandInfo.com}}</ref> Ireland is to the west and covers {{convert|32,590|sqmi|km2|abbr=on}}.<ref name="Calder-1995"/> The largest of the other islands are to be found in the ], ] and ] to the north, ] and the Isle of Man between Great Britain and Ireland, and the ] near the coast of France. The most densely populated island is ], which has an area of {{convert|9.5|mi2|km2|abbr=on}}<ref>{{Cite book |last=Naldrett |first=Peter |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1257549460 |title=Treasured Islands: The Explorer's Guide to Over 200 of the Most Beautiful and Intriguing Islands Around Britain |date=2021 |publisher=Conway |isbn=978-1-84486-593-2 |location= |oclc=1257549460}}</ref> but has the third highest population behind Great Britain and Ireland.<ref>{{Cite web|date=11 November 2019|title=These are Britain's biggest islands|url=https://www.independent.co.uk/travel/news-and-advice/britain-islands-biggest-uk-coastline-lewis-harris-portsea-isle-wight-skye-anglesey-a9197726.html|access-date=9 September 2021|website=The Independent}}</ref> | |||

| * clockwise around ] from the north: | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| The islands are at relatively low altitudes, with central Ireland and southern Great Britain particularly low-lying: the lowest point in the islands is the ] in ], Ireland, with an elevation of {{convert|-3.0|m|feet}}. The ] in the northern part of Great Britain are mountainous, with ] being the highest point on the islands at {{convert|1345|m|0|abbr=on}}.<ref name="Ordnance Survey Blog-2016" /> Other mountainous areas include Wales and parts of Ireland, although only seven peaks in these areas reach above {{convert|1000|m|0|abbr=on}}. Lakes on the islands are generally not large, although ] in Northern Ireland is an exception, covering {{Convert|150|sqmi|km2}}.{{citation needed|date=January 2012}} The largest freshwater body in Great Britain (by area) is ] at {{convert|27.5|sqmi|km2|0}}, and ] (by volume) whilst ] is the deepest freshwater body in the British Isles, with a maximum depth of {{convert|1017|ft|abbr=on|order=flip}}.<ref name="Gazetteerfor Scotland,Morar"> Morar, Loch.</ref> There are a number of major rivers within the British Isles. The longest is the ] in Ireland at {{convert|224|mi|0|abbr=on}}.<ref>.</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.britannica.com/place/River-Shannon |title=River Shannon |last=Ray |first=Michael |website=Encyclopædia Britannica |publisher=Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. |access-date=11 February 2020 |quote="about 161 miles (259 km) in a southerly direction to enter the Atlantic Ocean via a 70-mile (113-kilometre) estuary below Limerick city"}}</ref> The ] at {{convert|220|mi|0|abbr=on}}<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.britannica.com/place/River-Severn |title=River Severn |last=Wallenfeldt |first=Jeff |website=Encyclopædia Britannica |publisher=Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. |access-date=11 February 2020 |quote=about 180 miles (290 km) long, with the Severn estuary adding some 40 miles (64 km) to its total length}}</ref> is the longest in Great Britain. | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ===Climate=== | |||

| See also: | |||

| The ] is mild,<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.bgs.ac.uk/discoveringGeology/geologyOfBritain/iceAge/home.html |title=Ice and our landscape {{!}} Geology of Britain {{!}} British Geological Survey (BGS)|website=www.bgs.ac.uk |access-date=19 November 2019}}</ref> moist and changeable with abundant rainfall and a lack of temperature extremes. It is defined as a temperate oceanic climate, or ''Cfb'' on the ] system, a classification it shares with most of north-west Europe.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Peel, M. C. |author2=Finlayson B. L. |author3=McMahon, T. A. |year=2007 |title= Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification | journal=Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. |volume=11 |issue=5 |pages=1633–1644 |url=http://www.hydrol-earth-syst-sci.net/11/1633/2007/hess-11-1633-2007.html |issn=1027-5606 |doi=10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007 |bibcode=2007HESS...11.1633P |doi-access=free}} ''(direct: )''.</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.met.ie/marine/marine_climatology.asp|title=Marine Climatology|publisher=Met Éireann|access-date=30 January 2008}}</ref> The ] ("Gulf Stream"), which flows from the Gulf of Mexico, brings with it significant moisture and raises temperatures {{convert|11|C-change||abbr=on}} above the global average for the islands' latitudes.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Mayes |first=Julian |author2=Dennis Wheeler |title=Regional Climates of the British Isles |url=https://archive.org/details/regionalclimates00whee |url-access=limited |year=1997 |publisher=Routledge |location=London |page=}}</ref> Most Atlantic ] pass to the north of the islands; combined with the general ] and interactions with the landmass, this imposes a general east–west variation in climate.<ref><!--Mayes, ''Regional Climates of the British Isles''-->Ibid., pp. 13–14.</ref> There are four distinct climate patterns: south-east, with cold winters, warm and dry summers; south-west, having mild and very wet winters, warm and wet summers; north-west, generally wet with mild winters and cool summers; and north-east with cold winters, cool summers.<ref>{{Cite web |title=UK Climate Factsheet |url=https://www.rgs.org/CMSPages/GetFile.aspx?nodeguid=4abef83d-916e-4b81-b156-286947cc5de3&lang=en-GB |website= |publisher=] |type=PDF}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=The climate of the UK |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zpykxsg/revision/3 |access-date=19 November 2019 |website=]}}</ref> | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==Flora and fauna== | |||

| The islands are at relatively low altitudes, with central Ireland and southern Great Britain particularly low lying: the lowest point in the islands is ] at −4 ] (−13 ]). The ] in the northern part of Great Britain are mountainous, with ] being the highest point in the British Isles at 1,344 m (4,409 ft). Other mountainous areas include Wales and parts of the island of Ireland, but only seven peaks in these areas reach above 1,000 m (3,281 ft). Lakes on the islands are generally not large, although ] in Northern Ireland is an exception, covering 381 km² (147 square miles); the largest freshwater body in Great Britain is ] at 71.1 km² (27.5 square miles). Neither are rivers particularly long, the rivers ] at 354 km (219 miles) and ] at 386 km (240 miles) being the longest. | |||

| {{See also|Fauna of Great Britain|Fauna of Ireland|List of trees of Great Britain and Ireland}} | |||

| ], Ireland]] | |||

| The British Isles have a ] ], the ] ("Gulf Stream") which flows from the ] brings with it significant moisture and raises temperatures 11 °] (20 °]) above the global average for the islands' latitudes.<ref>{{cite book|last=Mayes| first=Julian| coauthors=Dennis Wheeler| title=Regional Climates of the British Isles| year=1997| publisher=Routledge| location=London| pages=p. 13}}</ref> Winters are thus warm and wet, with summers mild and also wet. Most Atlantic ] pass to the north of the islands, combined with the general ] and interactions with the landmass, this imposes an east-west variation in climate.<ref><!--Mayes, ''Regional Climates of the British Isles''-->Ibid., pp. 13–14.</ref> | |||

| The islands enjoy a mild climate and varied soils, giving rise to a diverse pattern of vegetation. Animal and plant life is similar to that of the north-western ]. There are however, fewer numbers of species, with Ireland having even less. All native ] and ] in Ireland is made up of species that migrated primarily from Great Britain. The only window when this could have occurred was prior to the melting of the ] between the two islands 14,000 years ago approaching the end of the last ice age. | |||

| === Transport === | |||

| ] is the busiest airport of Europe in terms of passenger traffic and the Dublin-London route is the busiest air route of Europe,<ref>Seán McCárthaigh, , Irish Examiner, March 31, 2003</ref> and the second-busiest in the world. Europe's two largest ], ] and ], operate from Ireland and Britain respectively. | |||

| As with most of Europe, prehistoric Britain and Ireland were covered with forest and swamp. Clearing began around 6000 BC and accelerated in medieval times. Despite this, Britain retained its primeval forests longer than most of Europe due to a small population and later development of trade and industry, and wood shortages were not a problem until the 17th century. By the 18th century, most of Britain's forests were consumed for shipbuilding or manufacturing charcoal and the nation was forced to import lumber from Scandinavia, North America, and the Baltic. Most forest land in Ireland is maintained by state forestation programmes. Almost all land outside urban areas is farmland. However, relatively large areas of forest remain in east and north Scotland and in southeast England. Oak, elm, ash and beech are amongst the most common trees in England. In Scotland, pine and birch are most common. Natural forests in Ireland are mainly oak, ash, ], birch and pine. Beech and ], though not native to Ireland, are also common there. Farmland hosts a variety of semi-natural vegetation of grasses and flowering plants. Woods, ], mountain slopes and marshes host ], wild grasses, ] and ]. | |||

| The ] and the southern ] are the busiest seaways in the world {{Fact|date=June 2007}}. The car ], ], traveling the ] is the largest in the world. The ], opened 1994, links Great Britain to ] and is the second-longest rail tunnel in the world. The idea of building a ] has been raised since 1895,<ref>"TUNNEL UNDER THE SEA", The Washington Post, May 2, 1897 </ref> when it was first investigated, but is not considered to be economically viable{{Fact|date=June 2007}}. Several potential Irish Sea tunnel projects have been proposed, most recently the ''Tusker Tunnel'' between the ports of ] and ] proposed by ] in 2004.<ref>A Vision of Transport in Ireland in 2050, , The Irish Academy of Engineers, 21/12/2004</ref><ref>Tunnel 'vision' under Irish Sea, , ] news, Thursday, 23 December, 2004</ref> A different proposed route is between ] and ], proposed in 1997 by a leading British engineering firm, Symonds, for a rail tunnel from Dublin to Holyhead. Either tunnel, at 80 km, would be by far the longest in the world, and would cost an estimated €20 billion. A proposal in 2007,<ref>BBC News, , 21 August 2007</ref> estimated the cost of building a bridge from ] in Northern Ireland to ] in Scotland at £3.5bn (€5bn). However, none of these is thought to be economically viable at this time. | |||

| Many larger animals, such as wolves, bears and ] are today extinct. However, some species such as red deer are protected. Other small mammals, such as ], ], ]s, ]s, ]s, and ]s, are very common and the ] has been reintroduced in parts of Scotland. ] have also been reintroduced to parts of southern England, following escapes from boar farms and illegal releases. Many rivers contain ]s and ] and ]s are numerous on coasts. There are about 250 bird species regularly recorded in Great Britain, and another 350 that occur with varying degrees of rarity. The most numerous species are ], ], ], ], ] and ].<ref>{{cite web |title=It's official – the Wren is our commonest bird |url=https://www.bto.org/press-releases/it%E2%80%99s-official-%E2%80%93-wren-our-commonest-bird |website=BTO |access-date=15 July 2020}}</ref> Farmland birds are declining in number,<ref>{{cite web |last1=Johnston |first1=Ian |title=Shocking declines in bird numbers show British wildlife is 'in serious trouble' |url=https://www.independent.co.uk/environment/uk-bird-numbers-species-declines-british-wildlife-turtle-dove-corn-bunting-willow-tits-farmland-a7744666.html |website=The Independent |date=19 May 2017 |access-date=15 July 2020}}</ref> except for those kept for game such as ], ], and ]. Fish are abundant in the rivers and lakes, in particular salmon, trout, perch and ]. Sea fish include ], cod, ], ] and bass, as well as mussels, crab and oysters along the coast. There are more than 21,000 species of insects. | |||

| ===Geology=== | |||

| {{main|Geology of the British Isles}} | |||

| ] ].]] | |||

| Few species of reptiles or amphibians are found in Great Britain or Ireland. Only three snakes are native to Great Britain: the ], the ] and the ];<ref>{{cite web |year=2007 |title=Guide to British Snakes |url=http://www.wildlifebritain.com/britishsnakes.php |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150308140526/http://www.wildlifebritain.com/britishsnakes.php |archive-date=8 March 2015 |access-date=17 August 2010 |publisher=Wildlife Britain}}</ref> none are native to Ireland. In general, Great Britain has slightly more variation and native wildlife, with weasels, ]s, wildcats, most ], ], ], ] and common toads also being absent from Ireland. This pattern is also true for birds and insects. Notable exceptions include the ] and certain species of woodlouse native to Ireland but not Great Britain. | |||

| The British Isles lie at the juncture of several regions with past episodes of ] mountain building. These ] form a complex geology which records a huge and varied span of earth history.<ref>{{cite book| last=Goudie| first=Andrew S.| coauthors=D. Brunsden| title=The Environment of the British Isles, an Atlas| year=1994| publisher=Clarendon Press| location=Oxford| pages=p. 2}}</ref> Of particular note was the ] during the ] Period, ca. 488–444 ] and early ] period, when the ] ] collided with the ] ] to form the mountains and hills in northern Britain and Ireland. Baltica formed roughly the north western half of Ireland and Scotland. Further collisions caused the ] in the ] and ] periods, forming the hills of ], south-west England, and south Wales. Over the last 500 million years the land which forms the islands has drifted northwest from around 30°S, crossing the ] around 370 million years ago to reach its present northern latitude.<ref><!--Goudie, ''The Environment of the British Isles, an Atlas''-->Ibid., p. 5.</ref> | |||

| Domestic animals include the ], ], ], ] and many varieties of cattle and sheep. | |||

| The islands have been shaped by numerous glaciations during the ], the most recent being the ]. As this ended, the central ] was de-glaciated (whether or not there was a land bridge between Great Britain and Ireland at this time is somewhat disputed, though there was certainly a single ice sheet covering the entire sea) and the ] flooded, with sea levels rising to current levels some 4,000 to 5,000 years ago, leaving the British Isles in their current form. | |||

| ==Demographics== | |||

| The islands' geology is highly complex, though there are large amounts of ] and ] rocks which formed in the ] and ] periods. The west coasts of Ireland and northern Great Britain that directly face the ] are generally characterized by long ], and headlands and bays; the internal and eastern coasts are "smoother". | |||

| {{Further|Demographics of the Republic of Ireland|Demographics of the United Kingdom}} | |||

| {{See also|Genetic history of the British Isles}} | |||

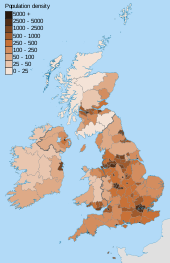

| ]]] | |||

| England has a generally high population density, with almost 80% of the total population of the islands. Elsewhere in Great Britain and Ireland, high density of population is limited to areas around a few large cities. The largest urban area by far is the ] with 9 million inhabitants. Other major population centres include the ] (2.4 million), ] (2.4 million) and ] (1.6 million) in England,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/about-ons/what-we-do/publication-scheme/published-ad-hoc-data/population/august-2012/mid-2010-urban-area-syoa-ests-england-and-wales.xls |title=Mid-2010 Population Estimates for 2001 Census defined Urban Areas in England and Wales by Single Year of Age and Sex |format=XLS |website=Office for National Statistics |access-date=16 June 2013 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130605151000/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/about-ons/what-we-do/publication-scheme/published-ad-hoc-data/population/august-2012/mid-2010-urban-area-syoa-ests-england-and-wales.xls |archive-date=5 June 2013}}</ref> ] (1.2 million) in Scotland<ref> {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130522082521/http://www.gro-scotland.gov.uk/files2/stats/population-estimates/special-area/settlements-localities2010/2010-settlements-table2.pdf |date=22 May 2013}} General Register Office for Scotland.</ref> and ] (1.9 million) in Ireland.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.dubchamber.ie/policy/economic-profile-of-dublin|title=Dublin Region Facts {{!}} Dublin Chamber of Commerce|website=www.dubchamber.ie|access-date=12 October 2017|archive-date=10 October 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171010034202/http://www.dubchamber.ie/policy/economic-profile-of-dublin|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| == Demographics == | |||

| The population of England rose rapidly during the 19th and 20th centuries, whereas the populations of Scotland and Wales showed little increase during the 20th century; the population of Scotland has remained unchanged since 1951. Ireland for most of its history had much the same population density as Great Britain (about one-third of the total population). However, since the ], the population of Ireland has fallen to less than one-tenth of the population of the British Isles. The famine caused a century-long population decline, drastically reduced the Irish population and permanently altered the demographic make-up of the British Isles. On a global scale, this disaster led to the creation of an ] that numbers fifteen times the current population of the island. | |||

| ] | |||

| The linguistic heritage of the British Isles is rich,<ref>{{Citation|title=Languages of the British Isles Past and Present|isbn=978-0-233-96666-3|author=WB Lockwood|publisher=Ladysmith|location=British Columbia|year=1975|quote=An introduction to the rich linguistic heritage of Great Britain and Ireland.|url-access=registration|url=https://archive.org/details/languagesofbriti0000lock}}</ref> with twelve languages from six groups across four branches of the ] ]. The ] of the ] sub-group (], ] and ]) and the ] sub-group (], Welsh and ], spoken in ]) are the only remaining ]—the last of their continental relations were extinct before the 7th century.<ref>{{Citation|editor-first=Matthew|editor-last=Spriggs|first1=John|last1=Waddel|first2=Jane|last2=Conroy|title=Celts and Other: Maritime Contact and Linguistic Change|work=Archaeology and Language|volume=35|page=127|publisher=Routledge|location=London|year=1999|isbn=978-0-415-11786-9|quote=Continental Celtic includes Gaulish, Lepontic, Hispano-Celtic (or Celtiberian) and Galatian. All were extinct by the seventh century AD.}}</ref> The ]s of ], ] and ] spoken in the Channel Islands are similar to French, a language also spoken there. A ], called ], is spoken by ], often to conceal meaning from those outside the group.<ref>{{Citation|title=Charles G. Leland: The Man & the Myth|first=Gary|last=Varner|year=2008|publisher=Lulu Press|location=Morrisville, North Carolina|isbn=978-1-4357-4394-6|page=41|quote=Shelta does in fact exist as a secret language as is used to conceal meaning from outsiders, used primarily in Gypsy business or negotiations or when speaking around the police.}}</ref> However, English, including ], is the dominant language, with few monoglots remaining in the other languages of the region.<ref>{{Citation|title=The Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics|volume=5|first=R. E. Asher|last=J. M. Y. Simpson|page=2505|publisher=Pergamon Press|location=Oxford|year=1994|isbn= 978-0-08-035943-4|quote=Thus, apart from the very young, there are virtually no monoglot speakers of Irish, Scots Gaelic, or Welsh.}}</ref> The ] of ] and ] became extinct around 1880.<ref>{{Citation|title=The Death of the Irish Language: A Qualified Obituary|first=Reg|last=Hindley|publisher=Taylor & Francis|location=Oxon|year=1990|isbn=978-0-415-04339-7|page=221|quote=Three indigenous languages have died in the British Isles since around 1780: Cornish (traditionally in 1777), Norn (the Norse language of Shetland: c. 1880), Manx (1974).}}</ref> <!-- This image might be of interest to keep, but hard to place right now in the article: ] showing language branches, major languages and typically where they are spoken for ] in the British Isles.]] --> | |||

| The demographics of the British Isles show dense population in England, which accounts for almost 80% of the total population of the region. In Ireland, Northern Ireland. Scotland, Wales dense populations are limited to areas around, or close to, their respective capitals. Major populations centres (greater than one million people) exist in the following areas: | |||

| ===Urban areas=== | |||

| * ] (8.5 million) | |||

| ** ] (12—14 million) | |||

| * ] (2.3 million) | |||

| * ] (2.2 million) | |||

| * ] (2.1 million) | |||

| * Greater Glasgow (1.7 million) | |||

| * ] (1.6 million) | |||

| * ] (1.1 million) | |||

| {| class="wikitable sortable" | |||

| The population of England has risen steadily throughout its history, while the populations of Scotland and Wales have shown little increase during the twentieth century - the population of Scotland remaining unchanged since 1951. Ireland, which for most of its history comprised a population proportionate to its land area, one third of the total population, has since the ] fallen to less than one tenth of the population of the British Isles. The famine, which caused a century-long population decline, drastically reduced the Irish population and permanently altered the demographic make-up of the British Isles. On a global scale this disaster led to the creation of an ] that number fifteen times the current population of the island | |||

| <center> | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center;" | |||

| |+ Population of Ireland since the Great Famine v Total for British Isles | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! | ! Rank | ||

| ! Urban area | |||

| ! width="80px" | Ireland | |||

| ! Population | |||

| ! width="80px" | British Isles | |||

| ! Country | |||

| ! width="80px" | % of total | |||

| ! Graph | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! |

! 1 | ||

| |align=left|]||9,787,426||] | |||

| | 8.2 || 26.7 || 30.7% | |||

| | rowspan="6" | ] | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! |

! 2 | ||

| |align=left|]||2,553,379||] | |||

| | 6.9 || 27.7 || 24.8% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! |

! 3 | ||

| |align=left|]||2,440,986||] | |||

| | 4.7 || 37.8 || 12.4% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! |

! 4 | ||

| |align=left|]||1,777,934||] | |||

| | 4.1 || 53.2 || 7.7% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! |

! 5 | ||

| |align=left|]||1,209,143||] | |||

| | 5.5 || 62.9 || 8.7% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! |

! 6 | ||

| |align=left|]||1,173,179||] | |||

| | 6.0 || 64.3 || 9.3% | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 7 | |||

| |align=left|]||864,122||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 8 | |||

| |align=left|]||855,569||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 9 | |||

| |align=left|]||774,891||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 10 | |||

| |align=left|]||729,977||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 11 | |||

| |align=left|]||685,386||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 12 | |||

| |align=left|]||617,280||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 13 | |||

| |align=left|]||595,879||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 14 | |||

| |align=left|]||508,916||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 15 | |||

| |align=left|]||482,005||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 16 | |||

| |align=left|]||474,485||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 17 | |||

| |align=left|]||466,266||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 18 | |||

| |align=left|]||481,082||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 19 | |||

| |align=left|]||376,633||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 20 | |||

| |align=left|]||372,775||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 21 | |||

| |align=left|]||359,262||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 22 | |||

| |align=left|]||335,415||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 23 | |||

| |align=left|]||325,264||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 24 | |||

| |align=left|]||318,014||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 25 | |||

| |align=left|]||314,018||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 26 | |||

| |align=left|]||313,322||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 27 | |||

| |align=left|]||306,844||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 28 | |||

| |align=left|]||300,352||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 29 | |||

| |align=left|]||295,310||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 30 | |||

| |align=left|]||270,468||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 31 | |||

| |align=left|]||260,203||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 32 | |||

| |align=left|]||258,018||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 33 | |||

| |align=left|]||252,397||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 34 | |||

| |align=left|]||243,931||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 35 | |||

| |align=left|]||239,409||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 36 | |||

| |align=left|]||229,431||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 37 | |||

| |align=left|]||223,281||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 38 | |||

| |align=left|]||222,000||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 39 | |||

| |align=left|]||215,963||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 40 | |||

| |align=left|]||213,166||] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 41 | |||

| |align=left|]||207,932||] | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| </center> | |||

| ==Political co-operation within the islands== | |||

| Between 1801 and 1922, Great Britain and Ireland together formed the ].<ref>Though the ] left the United Kingdom on ] ] the name of the United Kingdom was not changed to reflect that until April 1927, when ''Northern Ireland'' was substituted for ''Ireland'' in its name.</ref> In 1922, twenty-six counties of Ireland left the jurisdiction of the United Kingdom following the ] and the ]; the remaining six counties, mainly in the northeast of the island, became known as ] under the ]. Both states, but not the Isle of Man or the Channel Islands, are members of the ]. | |||

| However, despite independence of most of Ireland, political cooperation exists across the islands on some levels: | |||