| Revision as of 15:54, 11 November 2013 edit204.185.16.249 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 05:28, 27 December 2024 edit undoAltenmann (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers219,178 edits →topNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Communication used to influence opinion}} | |||

| {{About|the form of communication}} | |||

| {{About|the biased form of communication||Propaganda (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{pp-move-indef}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=May 2021}} | |||

| ]'' (1805), a ] depiction by ] during the ].]] | |||

| ]’s famous “]” propaganda poster, made during ]]] | |||

| ], the personification of the ].]] | |||

| '''Propaganda''' is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using ] to produce an emotional rather than a rational response to the information that is being presented.<ref name="brit_BLS">{{cite web |last=Smith |first=Bruce L. |author-link=Bruce Lannes Smith |title=Propaganda |publisher=], Inc. |date=17 February 2016 |url=http://www.britannica.com/topic/propaganda |access-date=23 April 2016}}</ref> Propaganda can be found in a wide variety of different contexts.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last=Hobbs |first=Renee |title=Mind Over Media: Propaganda Education for a Digital Age |publisher=W.W. Norton |year=2020 |location=New York |author-link=Renee Hobbs}}</ref> | |||

| ] period, depicting ] leader ] as a modern-day ] of communism slaying the dragon, which with the ] with the word "]" in Russian.]] | |||

| ] is what this person suffering from a ] costs the People's community during his lifetime. Fellow citizen, that is your money too. Read ' New People]]', the monthly magazine of the ] of the ]."]] | |||

| ] promoting harmony between ], ], and ]. The caption, written from right to left, says: "With the help of Japan, China, and Manchukuo, the world can be in peace." The flags shown are, left banana to right: the ]; the ]; the "]" flag.]] | |||

| Beginning in the twentieth century, the English term ''propaganda'' became associated with a ] approach, but historically, propaganda had been a neutral descriptive term of any material that promotes certain opinions or ].<ref name="brit_BLS"/><ref name="Diggs-Brown2011p48"/> | |||

| '''Propaganda''' is a form of communication aimed towards ] the attitude of the community toward some cause or position by presenting only one side of an argument. Propaganda statements may be partly false and partly true. Propaganda is usually repeated and dispersed over a wide variety of media in order to create the chosen result in audience attitudes. | |||

| A wide range of materials and media are used for conveying propaganda messages, which changed as new technologies were invented, including paintings, cartoons, posters, pamphlets, films, radio shows, TV shows, and websites. More recently, the digital age has given rise to new ways of disseminating propaganda, for example, in ], bots and algorithms are used to manipulate public opinion, e.g., by creating ] or ] to spread it on social media or using ]s to mimic real people in discussions in social networks. | |||

| As opposed to ] providing information, propaganda, in its most basic sense, presents information primarily to influence an audience. Propaganda often presents facts selectively (thus possibly ]) to encourage a particular synthesis, or uses loaded messages to produce an emotional rather than rational response to the information presented. The desired result is a change of the attitude toward the subject in the target audience to further a political, religious or commercial agenda. Propaganda can be used as a form of ideological or commercial warfare. | |||

| While the term propaganda has acquired a strongly negative connotation by association with its most manipulative and ] examples (e.g. ] used to justify the Holocaust), propaganda in its original sense was neutral, and could refer to uses that were generally benign or innocuous, such as public health recommendations, signs encouraging citizens to participate in a census or election, or messages encouraging persons to report crimes to law enforcement, among others. | |||

| ==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| The term comes from modern Latin.<ref>].</ref> Originally this word derived from a new administrative body of the Catholic Church (]) created in 1622, called the '']'' (''Congregation for Propagating the Faith''), or informally simply ''Propaganda''.<ref name="Diggs-Brown2011p48">Diggs-Brown, Barbara (2011) p. 48</ref><ref>http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=propaganda</ref> Its activity consisted was aimed at "propagating" the Catholic faith in non-Catholic countries.<ref name="Diggs-Brown2011p48"/> | |||

| {{Main|Propaganda Fide}} | |||

| From the 1790s, the term began being used also for ''propaganda'' in secular activities.<ref name="Diggs-Brown2011p48"/> The term began taking a pejorative connotation in the mid-19th century, when it was used in the political sphere.<ref name="Diggs-Brown2011p48"/> | |||

| ''Propaganda'' is a modern Latin word, the neuter plural ] form of {{lang|la|propagare}}, meaning 'to spread' or 'to propagate', thus ''propaganda'' means ''the things which are to be propagated''.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/152605 |title=propaganda, n. |date=December 2020 |website=Oxford English Dictionary |publisher=Oxford University Press |access-date=20 April 2021 }}</ref> Originally this word derived from a new administrative body (]) of the ] created in 1622 as part of the ], called the '']'' (''Congregation for Propagating the Faith''), or informally simply ''Propaganda''.<ref name="Diggs-Brown2011p48">{{Cite book |last=Diggs-Brown |first=Barbara |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7c0ycySng4YC&pg=PA48 |title=Strategic Public Relations: An Audience-Focused Approach |date=2011-08-12 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-534-63706-4 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=propaganda|title=Online Etymology Dictionary|access-date=6 March 2015}}</ref> Its activity was aimed at "propagating" the Catholic faith in non-Catholic countries.<ref name="Diggs-Brown2011p48"/> | |||

| == Types == | |||

| ] movement]] | |||

| Defining propaganda has always been a problem. The main difficulties have involved differentiating propaganda from other types of ], and avoiding an "if they do it then that's propaganda, while if we do it then that's information and education" ]ed approach. Garth Jowett and Victoria O'Donnell have provided a concise, workable definition of the term: "Propaganda is the deliberate, systematic attempt to shape perceptions, manipulate cognitions, and direct behavior to achieve a response that furthers the desired intent of the propagandist."<ref>Garth Jowett and Victoria O'Donnell, ''Propaganda and Persuasion'', 4th ed. Sage Publications, p. 7</ref> More comprehensive is the description by Richard Alan Nelson: "Propaganda is neutrally defined as a systematic form of purposeful persuasion that attempts to influence the emotions, attitudes, opinions, and actions of specified target audiences for ], political or commercial purposes through the controlled transmission of one-sided messages (which may or may not be factual) via mass and direct media channels. A propaganda organization employs propagandists who engage in propagandism—the applied creation and distribution of such forms of persuasion."<ref>Richard Alan Nelson, ''A Chronology and Glossary of Propaganda in the United States'' (1996) pp. 232–233</ref> | |||

| From the 1790s, the term began being used also to refer to ''propaganda'' in ] activities.<ref name="Diggs-Brown2011p48"/> In English, the cognate began taking a pejorative or negative connotation in the mid-19th century, when it was used in the political sphere.<ref name="Diggs-Brown2011p48"/> | |||

| Both definitions focus on the communicative process involved — or more precisely, on the purpose of the process, and allow "propaganda" to be considered objectively and then interpreted as positive or negative behavior depending on the perspective of the viewer or listener. | |||

| Non-English cognates of ''propaganda'' as well as some similar non-English terms retain neutral or positive connotations. For example, in official party discourse, '']'' is treated as a more neutral or positive term, though it can be used pejoratively through protest or other informal settings within China.<ref name=":1">{{Cite book |last=Edney |first=Kingsley |url=https://archive.org/details/globalizationofc0000edne/page/22/mode/1up?view=theater |title=The Globalization of Chinese Propaganda |date=2014 |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan US |isbn=978-1-349-47990-0 |location=New York |pages=22–24, 195 |language=en |doi=10.1057/9781137382153 |quote=Outside the realm of official discourse, however, propaganda (xuanchuan), is occasionally used in a negative way...(p. 195)}}</ref><ref name=":8">{{Cite book |last=Lin |first=Chunfeng |title=Red Tourism in China: Commodification of Propaganda |publisher=] |year=2023 |isbn=9781032139609}}</ref>{{Rp|pages=4-6}} | |||

| Propaganda is generally an appeal to emotion, not intellect.{{Citation needed|date=February 2011}} It shares techniques with ] and ], each of which can be thought of as propaganda that promotes a commercial product or shapes the perception of an organization, person, or brand. In post–World War II usage the word "propaganda" more typically refers to political or ] uses of these techniques or to the promotion of a set of ideas, since the term had gained a pejorative meaning. The refusal phenomenon was eventually to be seen in politics itself by the substitution of "political marketing" and other designations for "political propaganda". | |||

| ==Definitions== | |||

| Propaganda was often used to influence opinions and beliefs on religious issues, particularly during the split between the ] and the ]. Propaganda has become more common in ] contexts, in particular to refer to certain efforts sponsored by governments, political groups, but also often covert interests. In the early 20th century, propaganda was exemplified in the form of party slogans. Also in the early 20th century the term ''propaganda'' was used by the founders of the nascent ] industry to refer to their activities. This usage died out around the time of World War II, as the industry started to avoid the word, given the pejorative connotation it had acquired. | |||

| ] poster of ] with ] title: "Together we will crush him!".]] | |||

| <!-- ] by the German Army in 1915 was a major theme of ] anti-German propaganda.]] --> | |||

| Historian ] observed that newspapers were not expected to be independent organs of information when they began to play an important part in political life in the late 1700s, but were assumed to promote the views of their owners or government sponsors.<ref>Arthur Aspinall, ''Politics and the Press 1780-1850'', p. v {{ISBN|978-0-2-08012401}} New York: Barnes and Noble Books (1949)</ref> In the 20th century, the term propaganda emerged along with the rise of mass media, including newspapers and radio. As researchers began studying the effects of media, they used ] to explain how people could be influenced by emotionally-resonant persuasive messages. ] provided a broad definition of the term propaganda, writing it as: "the expression of opinions or actions carried out deliberately by individuals or groups with a view to influencing the opinions or actions of other individuals or groups for predetermined ends and through psychological manipulations."<ref>Ellul, Jacques (1965). Introduction by Konrad Kellen in '']'', pp. . Trans. Konrad Kellen & Jean Lerner from original 1962 French edition ''Propagandes''. Knopf, New York. {{ISBN|978-0-394-71874-3}} (1973 edition by Vintage Books, New York).</ref> Garth Jowett and ] theorize that propaganda | |||

| and ] are linked as humans use communication as a form of ] through the development and cultivation of propaganda materials.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Jowett |first1=Garth |last2=O'Donnell |first2=Victoria |title=Propaganda and Persuasion |date=2012 |publisher=Sage Publications Inc.|isbn=978-1412977821 |edition=5th |language=en}}{{Page needed|date=February 2020}}</ref> | |||

| In a 1929 literary debate with ], ] argues that, "Propaganda is making puppets of us. We are moved by hidden strings which the propagandist manipulates."<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Martin |first1=Everett Dean |author-link1=Everett Dean Martin |editor1-last=Leach |editor1-first=Henry Goddard |editor1-link=Henry Goddard Leach |title=Are We Victims of Propaganda, Our Invisible Masters: A Debate with Edward Bernays |journal=] |date=March 1929 |volume=81 |pages=142–150 |url=http://postflaviana.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/martin-bernays-debate.pdf |access-date=22 February 2020 |publisher=Forum Publishing Company |language=en}}</ref> In the 1920s and 1930s, propaganda was sometimes described as all-powerful. For example, Bernays acknowledged in his book '']'' that "The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country. We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of."<ref>{{cite book |last1=Bernays L |first1=Edward |author-link1=Edward Bernays |title=Propaganda |date=1928 |publisher=Horace |location=Liveright |page= |url=https://archive.org/details/BernaysPropaganda}}</ref> | |||

| Literally translated from the ] ] as "things that must be disseminated", in some cultures the term is neutral or even positive, while in others the term has acquired a strong negative connotation. The connotations of the term "propaganda" can also vary over time. For example, in ] and some ] speaking countries, particularly in the ], the word "propaganda" usually refers to the most common manipulative media — "advertising". | |||

| ]'s 2011 guidance for military public affairs defines propaganda as "information, ideas, doctrines, or special appeals disseminated to influence the opinion, emotions, attitudes, or behaviour of any specified group in order to benefit the sponsor, either directly or indirectly".<ref>{{cite book |last=Kuehl |first=Dan |date=2014-03-10 |editor-last=Snow |editor-first=Nancy |title=Propaganda and American Democracy |publisher=Louisiana State University Press |pages=12 |chapter=Chapter 1: Propaganda in the Digital Age |isbn=978-0-8071-5416-8}}</ref> | |||

| In English, ''propaganda'' was originally a neutral term for the dissemination of information in favor of any given cause. During the 20th century, however, the term acquired a thoroughly negative meaning in western countries, representing the intentional dissemination of often false, but certainly "compelling" claims to support or justify political actions or ideologies. This redefinition arose because{{Citation needed|date=June 2012}} both the ] and ]'s government under ] admitted explicitly to using propaganda favoring, respectively, ] and ], in all forms of public expression. As these ideologies were repugnant to liberal western societies, the negative feelings toward them came to be projected into the word "propaganda" itself. However, ] observed, as early as 1928, that, "Propaganda has become an epithet of contempt and hate, and the propagandists have sought protective coloration in such names as 'public relations council,' 'specialist in public education,' 'public relations adviser.' "<ref>pp. 260–261, "The Function of the Propagandist", ''International Journal of Ethics'', 38 (no. 3): pp. 258–268.</ref> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| ] propaganda in a 1947 comic book published by the Catechetical Guild Educational Society warning of "the dangers of a Communist takeover".]] | |||

| Roderick Hindery argues<ref>Hindery, Roderick R., Indoctrination and Self-deception or Free and Critical Thought? (2001)</ref> that propaganda exists on the political left, and right, and in mainstream centrist parties. Hindery further argues that debates about most social issues can be productively revisited in the context of asking "what is or is not propaganda?" Not to be overlooked is the link between propaganda, indoctrination, and terrorism/counterterrorism. He argues that threats to destroy are often as socially disruptive as physical devastation itself. | |||

| {{Main|History of propaganda}} | |||

| Propaganda also has much in common with ] campaigns by governments, which are intended to encourage or discourage certain forms of behavior (such as wearing seat belts, not smoking, not littering and so forth). Again, the emphasis is more political in propaganda. Propaganda can take the form of ]s, posters, TV and radio broadcasts and can also extend to any other ]. In the case of the United States, there is also an important legal (imposed by law) distinction between advertising (a type of '''overt propaganda''') and what the Government Accountability Office (GAO), an arm of the United States Congress, refers to as "covert propaganda". | |||

| Primitive forms of propaganda have been a human activity as far back as reliable recorded evidence exists. The ] ({{circa|515}} ]) detailing the rise of ] to the ] ] is viewed by most historians as an early example of propaganda.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Nagle|first=D. Brendan|title=The Ancient World: Readings in Social and Cultural History|year=2009|publisher=Pearson Education|isbn=978-0-205-69187-6|author2=Stanley M Burstein|page=|url=https://archive.org/details/ancientworldread00nagl/page/133}}</ref> Another striking example of propaganda during ancient history is the last ] (44–30 BCE) during which ] and ] blamed each other for obscure and degrading origins, cruelty, cowardice, oratorical and literary incompetence, debaucheries, luxury, drunkenness and other slanders.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Borgies|first=Loïc|title=Le conflit propagandiste entre Octavien et Marc Antoine. De l'usage politique de la uituperatio entre 44 et 30 a. C. n.|year=2016|publisher=Éditions Latomus |isbn=978-90-429-3459-7}}</ref> This defamation took the form of ''uituperatio'' (Roman rhetorical genre of the invective) which was decisive for shaping the Roman public opinion at this time. Another early example of propaganda was from ]. The emperor would send some of his men ahead of his army to spread rumors to the enemy. In many cases, his army was actually smaller than his opponents'.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Davison|first=W. Phillips|date=1971|title=Some Trends in International Propaganda|journal=The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science|volume=398|pages=1–13|doi=10.1177/000271627139800102|jstor=1038915|s2cid=145332403|issn=0002-7162}}</ref> | |||

| ] was the first ruler to utilize the power of the printing press for propaganda – in order to ], stir up patriotic feelings in the population of his empire (he was the first ruler who utilized one-sided battle reports – the early predecessors of modern newspapers or ''neue zeitungen'' – targeting the mass.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Kunczic |first1=Michael |editor-last=Preußer |editor-first=Heinz-Peter |contribution=Public Relations in Kriegzeiten – Die Notwendigkeit von Lüge und Zensur |title=Krieg in den Medien |date= 2016 |publisher=Brill |isbn=978-94-012-0230-5 |page=242 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=X3wfEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA242 |access-date=7 February 2022 |language=de}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Kunczik |first1=Michael |title=Images of Nations and International Public Relations |date=6 May 2016 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-136-68902-4 |page=158 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6hkfDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA158 |access-date=7 February 2022 |language=en}}</ref>) and influence the population of his enemies.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Museum |first1=Cincinnati Art |last2=Becker |first2=David P. |title=Six Centuries of Master Prints: Treasures from the Herbert Greer French Collection |date=1993 |publisher=Cincinnati Art Museum |isbn=978-0-931537-15-8 |page=68 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dSjrAAAAMAAJ |access-date=7 February 2022 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Silver |first1=Larry |title=Marketing Maximilian: The Visual Ideology of a Holy Roman Emperor |date=2008 |publisher=Princeton University Press |isbn=978-0-691-13019-4 |page=235 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4o3rAAAAMAAJ |access-date=7 February 2022 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Füssel |first1=Stephan |title=Gutenberg and the Impact of Printing |date=29 January 2020 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-351-93187-8 |pages=10–12 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2TPNDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA46-IA11 |access-date=7 February 2022 |language=en}}</ref> Propaganda during the ], helped by the spread of the ] throughout Europe, and in particular within Germany, caused new ideas, thoughts, and doctrine to be made available to the public in ways that had never been seen before the 16th century. During the era of the ], the ] had a flourishing network of newspapers and printers who specialized in the topic on behalf of the ] (and to a lesser extent on behalf of the ]).<ref>{{Cite journal | doi=10.14315/arg-1975-jg07 |title = The Reformation in Print: German Pamphlets and Propaganda|journal =Archive for Reformation History|volume = 66|year = 1975|last1 = Cole|first1 = Richard G.|s2cid = 163518886|pages=93–102| issn = 0003-9381 }}</ref> Academic Barbara Diggs-Brown conceives that the negative connotations of the term "propaganda" are associated with the earlier social and political transformations that occurred during the ] movement of 1789 to 1799 between the start and the middle portion of the 19th century, in a time where the word started to be used in a nonclerical and political context.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Diggs-Brown |first1=Barbara |title=Cengage Advantage Books: Strategic Public Relations: An Audience-Focused Approach |date=2011 |publisher=Cengage Learning |isbn=978-0-534-63706-4 |page=48 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7c0ycySng4YC&pg=PA48 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Journalistic theory generally holds that news items should be objective, giving the reader an accurate background and analysis of the subject at hand. On the other hand, advertisements evolved from the traditional commercial advertisements to include also a new type in the form of paid articles or broadcasts disguised as news. These generally present an issue in a very subjective and often misleading light, primarily meant to persuade rather than inform. Normally they use only subtle ] and not the more obvious ones used in traditional commercial advertisements. If the reader believes that a paid advertisement is in fact a news item, the message the advertiser is trying to communicate will be more easily "believed" or "internalized". | |||

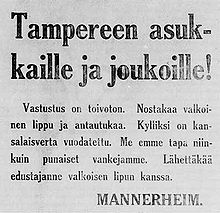

| ] circulated by the ] urging the ] to surrender during the ]. ]! Resistance is hopeless. Raise the ]<nowiki> and surrender. The blood of the citizen has been shed enough. We will not kill like the Reds kill our prisoners. Send your representative with a white flag.]</nowiki>'']] | |||

| Such advertisements are considered obvious examples of "covert" propaganda because they take on the appearance of objective information rather than the appearance of propaganda, which is misleading. Federal law specifically mandates that any advertisement appearing in the format of a news item must state that the item is in fact a paid advertisement. | |||

| The first large-scale and organised propagation of government propaganda was occasioned by the outbreak of the ] in 1914. After the defeat of Germany, military officials such as General ] suggested that British propaganda had been instrumental in their defeat. ] came to echo this view, believing that it had been a primary cause of the ] in the ] and ] in 1918 (see also: ]). In '']'' (1925) Hitler expounded his theory of propaganda, which provided a powerful base for his rise to power in 1933. Historian ] explains that "Hitler...puts no limit on what can be done by propaganda; people will believe anything, provided they are told it often enough and emphatically enough, and that contradicters are either silenced or smothered in calumny."<ref>Robert Ensor in David Thomson, ed., ''The New Cambridge Modern History: volume XII The Era of Violence 1890–1945'' (1st edition 1960), p 84.</ref> This was to be true in Germany and backed up with their army making it difficult to allow other propaganda to flow in.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Yourman|first=Julius|date=November 1939|title=Propaganda Techniques Within Nazi Germany|journal=Journal of Educational Sociology|volume=13|issue=3|pages=148–163|doi=10.2307/2262307|jstor=2262307}}</ref> Most propaganda in ] was produced by the ] under ]. Goebbels mentions propaganda as a way to see through the masses. Symbols are used towards propaganda such as justice, liberty and one's devotion to one's country.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Cantril|first=Hadley|date=1938|title=Propaganda Analysis|journal=The English Journal|volume=27|issue=3|pages=217–221|doi=10.2307/806063|jstor=806063}}</ref> ] saw continued use of propaganda as a weapon of war, building on the experience of ], by Goebbels and the British ], as well as the United States ].<ref>Fox, J. C., 2007, "Film propaganda in Britain and Nazi Germany : World War II cinema.", Oxford:Berg.</ref> | |||

| In the early 20th century, the invention of motion pictures (as in movies, diafilms) gave propaganda-creators a powerful tool for advancing political and military interests when it came to reaching a broad segment of the population and creating consent or encouraging rejection of the real or imagined enemy. In the years following the ] of 1917, the ] government sponsored the Russian film industry with the purpose of making propaganda films (e.g., the 1925 film '']'' glorifies ] ideals). In WWII, Nazi filmmakers produced highly emotional films to create popular support for occupying the ] and attacking Poland. The 1930s and 1940s, which saw the rise of ] states and the ], are arguably the "Golden Age of Propaganda". ], a filmmaker working in ], created one of the best-known propaganda movies, '']''. In 1942, the propaganda song '']'' was made in ] during the ], making fun of the ]'s failure in the ], referring the song's name to the Soviet's ], ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.fono.fi/KappaleenTiedot.aspx?kappale=niet+molotoff&ID=64fad317-515d-4153-832c-5744b443f28c|title=Fono.fi – Äänitetietokanta|website=www.fono.fi|language=fi|access-date=13 March 2020}}</ref> In the US, ] became popular, especially for winning over youthful audiences and aiding the U.S. war effort, e.g., '']'' (1942), which ridicules ] and advocates the value of freedom. Some American ]s in the early 1940s were designed to create a patriotic mindset and convince viewers that sacrifices needed to be made to defeat the ].<ref>Philip M. Taylor, 1990, "Munitions of the mind: A history of propaganda", Pg. 170.</ref> Others were intended to help Americans understand their Allies in general, as in films like ''Know Your Ally: Britain'' and ''Our Greek Allies''. Apart from its war films, Hollywood did its part to boost American morale in a film intended to show how stars of stage and screen who remained on the home front were doing their part not just in their labors, but also in their understanding that a variety of peoples worked together against the Axis menace: '']'' (1943) features one segment meant to dispel Americans' mistrust of the Soviets, and another to dispel their bigotry against the Chinese. Polish filmmakers in Great Britain created the anti-Nazi color film ''Calling Mr. Smith''<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://lux.org.uk/work/calling-mr-smith1|title=Calling Mr. Smith – LUX|access-date=30 January 2018|archive-date=25 April 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180425234317/https://lux.org.uk/work/calling-mr-smith1|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.centrepompidou.fr/id/cAXbMp/rqGRLe9/fr|title=Calling Mr Smith|website=Centre Pompidou}}</ref> (1943) about Nazi crimes in ] and about lies of Nazi propaganda.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://artincinema.com/franciszka-and-stefan-themerson-calling-mr-smith-1943/|title=Franciszka and Stefan Themerson: Calling Mr. Smith (1943) – artincinema|date=21 June 2015}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| The ] and the ] both used propaganda extensively during the ]. Both sides ], television, and radio programming to influence their own citizens, each other, and ] nations. Through a front organization called the Bedford Publishing Company, the CIA through a covert department called the ] disseminated over one million books to Soviet readers over the span of 15 years, including novels by George Orwell, Albert Camus, Vladimir Nabakov, James Joyce, and Pasternak in an attempt to promote anti-communist sentiment and sympathy of Western values.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2014/06/why-the-cia-distributed-pocket-size-copies-of-doctor-zhivago-in-the-soviet-union/371369/|title=Is Literature 'the Most Important Weapon of Propaganda'?|author=Nick Romeo|website=] |date=17 June 2014|access-date=28 February 2022}}</ref> ]'s contemporaneous novels '']'' and '']'' portray the use of propaganda in fictional dystopian societies. During the ], ] stressed the importance of propaganda.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://prudentiapolitica.blogspot.com/2014/05/fidel-propaganda-is-heart-of-our.html|title=Prudentia Politica|author=prudentiapolitica|date=20 May 2014|access-date=6 March 2015}}</ref>{{Better source needed|reason=Blogspot is not a reliable source.|date=March 2017}} Propaganda was used extensively by Communist forces in the ] as means of controlling people's opinions.<ref>{{cite journal|url=http://sealang.net/sala/archives/pdf8/sophana2007vietnamese.pdf|title=Vietnamese propaganda reflections from 1945 to 2000|author=Sophana Srichampa|journal=]|volume=37|pages=87–116|publisher=Mahidol University|location=Thailand|date=30 August 2007}}</ref> | |||

| The propagandist seeks to change the way people understand an issue or situation for the purpose of changing their actions and expectations in ways that are desirable to the interest group. Propaganda, in this sense, serves as a corollary to ] in which the same purpose is achieved, not by filling people's minds with approved information, but by preventing people from being confronted with opposing points of view. What sets propaganda apart from other forms of advocacy is the willingness of the propagandist to change people's understanding through deception and confusion rather than persuasion and understanding. The leaders of an organization know the information to be one sided or untrue, but this may not be true for the rank and file members who help to disseminate the propaganda. | |||

| During the ], propaganda was used as a ] by governments of ] and ]. Propaganda was used to create fear and hatred, and particularly to incite the ] population against the other ethnicities (], ], ] and other non-Serbs). Serb media made a great effort in justifying, revising or denying mass ] committed by Serb forces during these wars.<ref name="Boston University">{{cite web|date=12 April 1999|title=Serbian Propaganda: A Closer Look|url=http://www.bu.edu/globalbeat/pubs/Pesic041299.html|quote=NOAH ADAMS: The European Center for War, Peace and the News Media, based in London, has received word from Belgrade that no pictures of mass Albanian refugees have been shown at all, and that the Kosovo humanitarian catastrophe is only referred to as the one made up or over-emphasised by Western propaganda.|access-date=21 December 2007|archive-date=4 June 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130604064124/http://www.bu.edu/globalbeat/pubs/Pesic041299.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| ===Religion=== | |||

| More in line with the religious roots of the term, it is also used widely in the debates about ]s (NRMs), both by people who defend them and by people who oppose them. The latter pejoratively call these NRMs ]s. ] and ] accuse the leaders of what they consider cults of using propaganda extensively to recruit followers and keep them. Some social scientists, such as the late Jeffrey Hadden, and ] affiliated scholars accuse ex-members of "cults" who became vocal critics and the ] of making these unusual religious movements look bad without sufficient reasons.<ref>{{cite web| title=The Religious Movements Page: Conceptualizing "Cult" and "Sect" | url=http://religiousmovements.lib.virginia.edu/cultsect/concult.htm | accessdate=December 4, 2005 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web| title=Polish Anti-Cult Movement (Koscianska) - CESNUR | url=http://www.cesnur.org/conferences/riga2000/koscianska.htm | accessdate=December 4, 2005 }}</ref> | |||

| ==Public perceptions== | |||

| ===Wartime=== | |||

| ] addressed the crowd in a poster promoted by the ].]] | |||

| Propaganda is a powerful weapon in war; it is used to dehumanize and create hatred toward a supposed enemy, either internal or external, by creating a false image in the mind. This can be done by using derogatory or racist terms, avoiding some words or by making allegations of enemy atrocities. Most propaganda wars require the home population to feel the enemy has inflicted an injustice, which may be fictitious or may be based on facts. The home population must also decide that the cause of their nation is just. | |||

| In the early 20th century the term propaganda was used by the founders of the nascent ] industry to refer to their people. Literally translated from the ] ] as "things that must be disseminated", in some cultures the term is neutral or even positive, while in others the term has acquired a strong negative connotation. The connotations of the term "propaganda" can also vary over time. For example, in ] and some Spanish language speaking countries, particularly in the ], the word "propaganda" usually refers to the most common manipulative media in business terms – "advertising".<ref>{{cite web|title=English translation of Portuguese 'propaganda'|url=https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/portuguese-english/propaganda|website=collinsdictionary.com|access-date=2 January 2024}}</ref> | |||

| Propaganda is also one of the methods used in ], which may also involve ] operations. The term propaganda may also refer to false information meant to reinforce the mindsets of people who already believe as the propagandist wishes. The assumption is that, if people believe something false, they will constantly be assailed by doubts. Since these doubts are unpleasant (see ]), people will be eager to have them extinguished, and are therefore receptive to the reassurances of those in power. For this reason ''propaganda is often addressed to people who are already sympathetic to the agenda''. This process of reinforcement uses an individual's predisposition to self-select "agreeable" information sources as a mechanism for maintaining control. | |||

| ] movement]] | |||

| ] arm-in-arm with ] symbolizes the British-American alliance in World War I.]] | |||

| In English, ''propaganda'' was originally a neutral term for the dissemination of information in favor of any given cause. During the 20th century, however, the term acquired a thoroughly negative meaning in western countries, representing the intentional dissemination of often false, but certainly "compelling" claims to support or justify political actions or ideologies. According to ], the term began to fall out of favor due to growing public suspicion of propaganda in the wake of its use during World War I by the ] in the United States and the ] in Britain: Writing in 1928, Lasswell observed, "In democratic countries the official propaganda bureau was looked upon with genuine alarm, for fear that it might be suborned to party and personal ends. The outcry in the United States against Mr. ] famous Bureau of Public Information (or 'Inflammation') helped to din into the public mind the fact that propaganda existed. ... The public's discovery of propaganda has led to a great of lamentation over it. Propaganda has become an epithet of contempt and hate, and the propagandists have sought protective coloration in such names as 'public relations council,' 'specialist in public education,' 'public relations adviser.' "<ref>{{Cite journal |jstor = 2378152|last1 = Lasswell|first1 = Harold D.|title = The Function of the Propagandist|journal = International Journal of Ethics|volume = 38|issue = 3|pages = 258–268|year = 1928|doi = 10.1086/intejethi.38.3.2378152|s2cid = 145021449}} pp. 260–261</ref> In 1949, political science professor Dayton David McKean wrote, "After World War I the word came to be applied to 'what you don't like of the other fellow's publicity,' as Edward L. Bernays said...."<ref>p. 113, ''Party and Pressure Politics'', Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1949.</ref> | |||

| <span id="grey" />Propaganda can be classified according to the source and nature of the message. '''] '''generally comes from an openly identified source, and is characterized by gentler methods of persuasion, such as standard public relations techniques and one-sided presentation of an argument. '''] '''is identified as being from one source, but is in fact from another. This is most commonly to disguise the true origins of the propaganda, be it from an enemy country or from an organization with a negative public image. '''Grey propaganda ''' is propaganda without any identifiable source or author. A major application of grey propaganda is making enemies believe falsehoods using ]s: As phase one, to make someone believe "A", one releases as grey propaganda "B", the opposite of "A". In phase two, "B" is discredited using some ]. The enemy will then assume "A" to be true. | |||

| ===Contestation=== | |||

| In scale, these different types of propaganda can also be defined by the potential of true and correct information to compete with the propaganda. For example, opposition to white propaganda is often readily found and may slightly discredit the propaganda source. Opposition to grey propaganda, when revealed (often by an inside source), may create some level of public outcry. Opposition to black propaganda is often unavailable and may be dangerous to reveal, because public cognizance of black propaganda tactics and sources would undermine or backfire the very campaign the black propagandist supported. | |||

| The term is essentially contested and some have argued for a neutral definition,<ref>{{Cite journal | doi=10.1080/14616700220145641 |title = Strategic Communications or Democratic Propaganda?|journal = Journalism Studies|volume = 3|issue = 3|pages = 437–441|year = 2002|last1 = Taylor|first1 = Philip M.|s2cid = 144546254}}</ref><ref name="Briant2015p9">{{Cite book |jstor = j.ctt18mvn1n|title = Propaganda and Counter-terrorism|last1 = Briant|first1 = Emma Louise|year = 2015|isbn = 9780719091056|publisher = Manchester University Press|location=Manchester|page=9}}</ref> arguing that ethics depend on intent and context,<ref name="Briant2015">{{Cite book |jstor = j.ctt18mvn1n|title = Propaganda and Counter-terrorism|last1 = Briant|first1 = Emma Louise|year = 2015|isbn = 9780719091056|publisher = Manchester University Press|location=Manchester}}</ref> while others define it as necessarily unethical and negative.<ref>Doob, L.W. (1949), Public Opinion and Propaganda, London: Cresset Press p 240</ref> ] defines it as "the deliberate manipulation of representations (including text, pictures, video, speech etc.) with the intention of producing any effect in the audience (e.g. action or inaction; reinforcement or transformation of feelings, ideas, attitudes or behaviours) that is desired by the propagandist."<ref name="Briant2015p9" /> The same author explains the importance of consistent terminology across history, particularly as contemporary euphemistic synonyms are used in governments' continual efforts to rebrand their operations such as 'information support' and ].<ref name="Briant2015p9" /> Other scholars also see benefits to acknowledging that propaganda can be interpreted as beneficial or harmful, depending on the message sender, target audience, message, and context.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| <!-- Image with inadequate rationale removed: ] film '']'' (Spitfire)]] --> | |||

| Propaganda may be administered in insidious ways. For instance, disparaging ] about the history of certain groups or foreign countries may be encouraged or tolerated in the educational system. Since few people actually double-check what they learn at school, such disinformation will be repeated by journalists as well as parents, thus reinforcing the idea that the disinformation item is really a "well-known fact", even though no one repeating the myth is able to point to an authoritative source. The disinformation is then recycled in the media and in the educational system, without the need for direct governmental intervention on the media. Such permeating propaganda may be used for political goals: by giving citizens a false impression of the quality or policies of their country, they may be incited to reject certain proposals or certain remarks or ignore the experience of others. | |||

| David Goodman argues that the 1936 ] "Convention on the Use of Broadcasting in the Cause of Peace" tried to create the standards for a liberal international public sphere. The Convention encouraged empathetic and neighborly radio broadcasts to other nations. It called for League prohibitions on international broadcast containing hostile speech and false claims. It tried to define the line between liberal and illiberal policies in communications, and emphasized the dangers of nationalist chauvinism. With Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia active on the radio, its liberal goals were ignored, while free speech advocates warned that the code represented restraints on free speech.<ref>David Goodman, "Liberal and Illiberal Internationalism in the Making of the League of Nations Convention on Broadcasting in the Cause of Peace." ''Journal of World History'' 31.1 (2020): 165-193. </ref> | |||

| In the Soviet Union during the Second World War, the propaganda designed to encourage civilians was controlled by Stalin, who insisted on a heavy-handed style that educated audiences easily saw was inauthentic. On the other hand the unofficial rumours about German atrocities were well founded and convincing.<ref>Karel C. Berkhoff, ''Motherland in Danger: Soviet Propaganda during World War II'' (2012) </ref> | |||

| == |

==Types== | ||

| {{Merge to|Propaganda techniques|discuss=Talk:Propaganda techniques#Merger proposal|date=February 2013}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] propaganda]] | |||

| Identifying propaganda has always been a problem.<ref>Daniel J Schwindt, , 2016, pp. 202–204.</ref> The main difficulties have involved differentiating propaganda from other types of ], and avoiding a ]ed approach. Richard Alan Nelson provides a definition of the term: "Propaganda is neutrally defined as a systematic form of purposeful persuasion that attempts to influence the emotions, attitudes, opinions, and actions of specified target audiences for ], political or commercial purposes<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.history.com/news/wwii-propaganda-private-snafu-flashback|title=This WWII Cartoon Taught Soldiers How to Avoid Certain Death|last=McNearney|first=Allison|website=HISTORY|date=29 August 2018 |language=en|access-date=2020-03-29}}</ref> through the controlled transmission of one-sided messages (which may or may not be factual) via mass and direct media channels."<ref>Richard Alan Nelson, ''A Chronology and Glossary of Propaganda in the United States'' (1996) pp. 232–233</ref> The definition focuses on the communicative process involved – or more precisely, on the purpose of the process, and allow "propaganda" to be interpreted as positive or negative behavior depending on the perspective of the viewer or listener. | |||

| {{See also|Doublespeak|Cult of personality|Spin (politics)|Factoid}} | |||

| Propaganda can often be recognized by the rhetorical strategies used in its design. In the 1930s, the Institute for Propaganda Analysis identified a variety of propaganda techniques that were commonly used in newspapers and on the radio, which were the mass media of the time period. Propaganda techniques include "name calling" (using derogatory labels), "bandwagon" (expressing the social appeal of a message), or "glittering generalities" (using positive but imprecise language).<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Hobbs|first=Renee|date=2014-11-09|title=Teaching about Propaganda: An Examination of the Historical Roots of Media Literacy|journal=Journal of Media Literacy Education|volume=6|issue=2|pages=56–67|doi=10.23860/jmle-2016-06-02-5|issn=2167-8715|doi-access=free}}</ref> With the rise of the internet and social media, Renee Hobbs identified four characteristic design features of many forms of contemporary propaganda: (1) it activates strong emotions; (2) it simplifies information; (3) it appeals to the hopes, fears, and dreams of a targeted audience; and (4) it attacks opponents.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Hobbs|first=Renee|title=Mind Over Media|publisher=Norton|year=2020}}</ref> | |||

| Common media for transmitting propaganda messages include news reports, government reports, historical revision, ], books, leaflets, ], radio, television, and posters. Less common nowadays are letter post ] examples of which of survive from the time of the American Civil War. (Connecticut Historical Society; Civil War Collections; Covers.) In principle any thing that appears on a poster can be produced on a reduced scale on a pocket-style envelope with corresponding proportions to the poster. The case of radio and television, propaganda can exist on news, current-affairs or talk-show segments, as '''advertising''' or public-service '''announce "spots"''' or as long-running '''advertorials'''. Propaganda campaigns often follow a strategic transmission pattern to indoctrinate the target group. This may begin with a simple transmission such as a leaflet dropped from a plane or an advertisement. Generally these messages will contain directions on how to obtain more information, via a web site, hot line, radio program, etc (as it is seen also for selling purposes among other goals). The strategy intends to initiate the individual from information recipient to information seeker through reinforcement, and then from information seeker to ] through indoctrination. | |||

| Propaganda is sometimes evaluated based on the intention and goals of the individual or institution who created it. According to historian ], propaganda is defined as either white, grey or black. White propaganda openly discloses its source and intent. Grey propaganda has an ambiguous or non-disclosed source or intent. ] purports to be published by the enemy or some organization besides its actual origins<ref name="new">{{cite book|title=Selling the War|publisher=Orbis Publishing|first=Zbynek|last=Zeman|date=1978|isbn=978-0-85613-312-1|url-access=registration|url=https://archive.org/details/sellingwarartpro0000zema}}</ref> (compare with ], a type of clandestine operation in which the identity of the sponsoring government is hidden). In scale, these different types of propaganda can also be defined by the potential of true and correct information to compete with the propaganda. For example, opposition to white propaganda is often readily found and may slightly discredit the propaganda source. Opposition to grey propaganda, when revealed (often by an inside source), may create some level of public outcry. Opposition to black propaganda is often unavailable and may be dangerous to reveal, because public cognizance of black propaganda tactics and sources would undermine or backfire the very campaign the black propagandist supported. | |||

| A number of techniques based in ] research are used to generate propaganda. Many of these same techniques can be found under ], since propagandists use arguments that, while sometimes convincing, are not necessarily valid. | |||

| <!-- ] by the German Army in 1915 was a major theme of ] anti-German propaganda.]] --> | |||

| The propagandist seeks to change the way people understand an issue or situation for the purpose of changing their actions and expectations in ways that are desirable to the interest group. Propaganda, in this sense, serves as a corollary to censorship in which the same purpose is achieved, not by filling people's minds with approved information, but by preventing people from being confronted with opposing points of view. What sets propaganda apart from other forms of advocacy is the willingness of the propagandist to change people's understanding through deception and confusion rather than persuasion and understanding. The leaders of an organization know the information to be one sided or untrue, but this may not be true for the rank and file members who help to disseminate the propaganda. | |||

| Some time has been spent analyzing the means by which the propaganda messages are transmitted. That work is important but it is clear that information dissemination strategies become propaganda strategies only when coupled with ''propagandistic messages''. Identifying these messages is a necessary prerequisite to study the methods by which those messages are spread. Below are a number of techniques for generating propaganda: | |||

| ], commissioned by ].<ref name="Edwards-1"> Fortress Press, 2004. {{ISBN|978-0-8006-3735-4}}</ref> Title: Kissing the Pope's Feet.<ref>In Latin, the title reads "Hic oscula pedibus papae figuntur"</ref> German peasants respond to a papal bull of ]. Caption reads: "Don't frighten us Pope, with your ban, and don't be such a furious man. Otherwise we shall turn around and show you our rears."<ref>"Nicht Bapst: nicht schreck uns mit deim ban, Und sey nicht so zorniger man. Wir thun sonst ein gegen wehre, Und zeigen dirs Bel vedere"</ref><ref name="Edwards-2">{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kYbupalP98kC&pg=PA198|title=Luther's Last Battles: Politics and Polemics 1531–46|first=Mark U.|last=Edwards|year=2004|publisher=Fortress Press|isbn= 9781451413984|page=199|via=Google Books}}</ref>]] | |||

| ] | |||

| ], 1966.]] | |||

| ;] | |||

| :A Latin phrase that has come to mean attacking one's opponent, as opposed to attacking their arguments. | |||

| ===Religious=== | |||

| ;] | |||

| :This argument approach uses tireless repetition of an idea. An idea, especially a simple slogan, that is repeated enough times, may begin to be taken as the truth. This approach works best when media sources are limited or controlled by the propagator. | |||

| Propaganda was often used to influence opinions and beliefs on religious issues, particularly during the split between the ] and the ] or during the ].<ref>{{cite news |last=Fisher |first=Lane |url=https://www.truvere.com/trouvre-poets-reflectors-of-societal-zeal |title=Trouvère Poets: Reflectors of Societal Zeal |work=Truvere |publisher=Truvere |date=2022-07-07 |accessdate=2022-09-13 |archive-date=5 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230405005245/https://www.truvere.com/trouvre-poets-reflectors-of-societal-zeal |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| ;] | |||

| :Appeals to authority cite prominent figures to support a position, idea, argument, or course of action. | |||

| The sociologist ] has argued that members of the ] and ] accuse the leaders of what they consider cults of using propaganda extensively to recruit followers and keep them. Hadden argued that ex-members of cults and the anti-cult movement are committed to making these movements look bad.<ref>{{cite web| title=The Religious Movements Page: Conceptualizing "Cult" and "Sect" | url=http://religiousmovements.lib.virginia.edu/cultsect/concult.htm | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060207042448/http://religiousmovements.lib.virginia.edu/cultsect/concult.htm | archive-date=7 February 2006 | access-date=4 December 2005 }}</ref> | |||

| ;] | |||

| :Appeals to fear and seeks to build support by instilling anxieties and panic in the general population, for example, ] exploited Theodore Kaufman's '']'' to claim that the Allies sought the extermination of the German people. | |||

| Propaganda against other religions in the same community or propaganda intended to keep political power in the hands of a religious elite can incite religious hate on a global or national scale. It could make use of many propaganda mediums. War, terrorism, riots, and other violent acts can result from it. It can also conceal injustices, inequities, exploitation, and atrocities, leading to ignorance-based indifference and alienation.<ref name="Religiuos propaganda definition">{{cite web |title=Religious propaganda |url=http://encyclopedia.uia.org/en/problem/religious-propaganda |website=Encyclopedia.uia.org |publisher=Union of International Associations |access-date=9 November 2023}}</ref> | |||

| ;Appeal to prejudice | |||

| :Using loaded or emotive terms to attach value or moral goodness to believing the proposition. Used in biased or misleading ways. | |||

| ===Wartime=== | |||

| ;] | |||

| :Bandwagon and "inevitable-victory" appeals attempt to persuade the target audience to join in and take the course of action that "everyone else is taking". | |||

| {{More citations needed section|date=April 2021}} | |||

| ;Inevitable victory | |||

| ] portrays the ] in a way that he hoped would make Americans angry and support the ].]]In the ], the Athenians exploited the figures from stories about ] as well as other mythical images to incite feelings against ]. For example, ] was even portrayed as an Athenian, whose mother ] would avenge Troy.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Magill |first1=Frank Northen |title=Dictionary of World Biography |date=23 January 2003 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn=978-1-57958-040-7 |page=422 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wyKaVFZqbdUC&pg=PA422 |access-date=7 February 2022 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Rutter |first1=Keith |title=Word And Image In Ancient Greece |date=31 March 2020 |publisher=Edinburgh University Press |isbn=978-0-7486-7985-0 |page=68 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=q28xEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA68 |access-date=7 February 2022 |language=en}}</ref> During the ], extensive campaigns of propaganda were carried out by both sides. To dissolve the Roman system of ] and the Greek ], ] released without conditions Latin prisoners that he had treated generously to their native cities, where they helped to disseminate his propaganda.<ref name="Stepper">{{cite journal |last1=Stepper |first1=R. |title=Politische parolen und propaganda im Hannibalkrieg |journal=Klio |date=2006 |volume=88 |issue=2 |pages=397–407 |doi=10.1524/klio.2006.88.2.397 |s2cid=190002621 |url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/298534203 |access-date=7 February 2022}}</ref> The Romans on the other hand tried to portray Hannibal as a person devoid of humanity and would soon lose the favour of gods. At the same time, led by ], they organized elaborate religious rituals to protect Roman morale.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Hoyos |first1=Dexter |title=A Companion to the Punic Wars |date=26 May 2015 |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |isbn=978-1-119-02550-4 |page=275 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UzJ3BwAAQBAJ&pg=PA275 |access-date=7 February 2022 |language=en}}</ref><ref name="Stepper" /> | |||

| :Invites those not already on the bandwagon to join those already on the road to certain victory. Those already or at least partially on the bandwagon are reassured that staying aboard is their best course of action. | |||

| In the early sixteenth century, ] invented one kind of psychological warfare targeting the enemies. During his war against ], he attached pamphlets to balloons that his archers would shoot down. The content spoke of freedom and equality and provoked the populace to rebel against the tyrants (their Signoria).{{sfn|Füssel|2020|10–12}} | |||

| ;Join the crowd | |||

| :This technique reinforces people's natural desire to be on the winning side. This technique is used to convince the audience that a program is an expression of an irresistible mass movement and that it is in their best interest to join. | |||

| ] 1928.]] | |||

| Post–World War II usage of the word "propaganda" more typically refers to political or nationalist uses of these techniques or to the promotion of a set of ideas. | |||

| ;Beautiful people | |||

| ], by ], {{Circa|1917}}]] ]" posters, this iconic piece of propaganda tries to warn citizens against giving out secrets.]] | |||

| :The type of propaganda that deals with celebrities or depicts attractive, happy people. This suggests if people buy a product or follow a certain ideology, they too will be happy or successful. | |||

| Propaganda is a powerful weapon in war; in certain cases, it is used to ] and create hatred toward a supposed enemy, either internal or external, by creating a false image in the mind of soldiers and citizens. This can be done by using derogatory or racist terms (e.g., the racist terms "]" and "]" used during World War II and the Vietnam War, respectively), avoiding some words or language or by making allegations of enemy atrocities. The goal of this was to demoralize the opponent into thinking what was being projected was actually true.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Williamson|first1=Samuel R.|last2=Balfour|first2=Michael|date=Winter 1980|title=Propaganda in War, 1939–1945: Organisations, Policies and Publics in Britain and Germany.|journal=Political Science Quarterly|volume=95|issue=4|pages=715|doi=10.2307/2150639|jstor=2150639}}</ref> Most propaganda efforts in wartime require the home population to feel the enemy has inflicted an injustice, which may be fictitious or may be based on facts (e.g., the sinking of the passenger ship {{RMS|Lusitania}} by the German Navy in World War I). The home population must also believe that the cause of their nation in the war is just. In these efforts it was difficult to determine the accuracy of how propaganda truly impacted the war.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Eksteins|first1=Modris|last2=Balfour|first2=Michael|date=October 1980|title=Propaganda in War, 1939–1945: Organisations, Policies and Publics in Britain and Germany.|journal=The American Historical Review|volume=85|issue=4|pages=876|doi=10.2307/1868905|jstor=1868905}}</ref> In NATO doctrine, propaganda is defined as "Information, especially of a biased or misleading nature, used to promote a political cause or point of view."<ref>North Atlantic Treaty Organization, NATO Standardization Agency AAP-6 – Glossary of terms and definitions, 2-P-9.</ref> Within this perspective, the information provided does not need to be necessarily false but must be instead relevant to specific goals of the "actor" or "system" that performs it. | |||

| Propaganda is also one of the methods used in ], which may also involve ] operations in which the identity of the operatives is depicted as those of an enemy nation (e.g., The ] used ] planes painted in ] markings). The term propaganda may also refer to false information meant to reinforce the mindsets of people who already believe as the propagandist wishes (e.g., During the First World War, the main purpose of British propaganda was to encourage men to join the army, and women to work in the country's industry. Propaganda posters were used because regular general radio broadcasting was yet to commence and TV technology was still under development).<ref>Callanan, James D. The Evolution of The CIA's Covert Action Mission, 1947–1963. Durham University. 1999.</ref> The assumption is that, if people believe something false, they will constantly be assailed by doubts. Since these doubts are unpleasant (see ]), people will be eager to have them extinguished, and are therefore receptive to the reassurances of those in power. For this reason, propaganda is often addressed to people who are already sympathetic to the agenda or views being presented. This process of reinforcement uses an individual's predisposition to self-select "agreeable" information sources as a mechanism for maintaining control over populations. | |||

| ;The Lie | |||

| :The repeated articulation of a complex of events that justify subsequent action. The descriptions of these events have elements of truth, and the "big lie" generalizations merge and eventually supplant the public's accurate perception of the underlying events. After World War I the German ] explanation of the cause of their defeat became a justification for Nazi re-militarization and revanchist aggression. | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| ;] | |||

| | align = right | |||

| :Presenting only two choices, with the product or idea being propagated as the better choice. For example: "]...." | |||

| | image1 = Vecernje-novosti-propaganda.jpg | |||

| | width1 = 150 | |||

| | alt1 = | |||

| | caption1 = | |||

| | image2 = Uroš Predić - Siroče.jpg | |||

| | width2 = 225 | |||

| | alt2 = | |||

| | caption2 = | |||

| | footer = Serbian propaganda from the ] (1992–95) presented as an actual photograph from the scene of, as stated in report below the image, a ''"Serbian boy whose whole family was killed by Bosnian Muslims"''. The image is derived from an 1879 "Orphan on mother's grave" painting by ] (alongside).<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.e-novine.com/entertainment/entertainment-tema/31106-Pravda-Uroa-Predia.html |publisher=e-novine.com |title=Pravda za Uroša Predića! |access-date=5 May 2015}}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| Propaganda may be administered in insidious ways. For instance, disparaging ] about the history of certain groups or foreign countries may be encouraged or tolerated in the educational system. Since few people actually ] what they learn at school, such disinformation will be repeated by journalists as well as parents, thus reinforcing the idea that the disinformation item is really a "well-known fact", even though no one repeating the myth is able to point to an authoritative source. The disinformation is then recycled in the media and in the educational system, without the need for direct governmental intervention on the media. Such permeating propaganda may be used for political goals: by giving citizens a false impression of the quality or policies of their country, they may be incited to reject certain proposals or certain remarks or ignore the experience of others. | |||

| ;] | |||

| ] arm-in-arm with ] symbolizes the British-American alliance in World War I.]] | |||

| :All vertebrates, including humans, respond to ]. That is, if object A is always present when object B is present and object B causes a physical reaction (e.g., disgust, pleasure) then we will when presented with object A when object B is not present, we will experience the same feelings. | |||

| ] as a "]]] | |||

| In the Soviet Union during the Second World War, the propaganda designed to encourage civilians was controlled by Stalin, who insisted on a heavy-handed style that educated audiences easily saw was inauthentic. On the other hand, the unofficial rumors about German atrocities were well founded and convincing.<ref>Karel C. Berkhoff, ''Motherland in Danger: Soviet Propaganda during World War II'' (2012) </ref> Stalin was a Georgian who spoke Russian with a heavy accent. That would not do for a national hero so starting in the 1930s all new visual portraits of Stalin were retouched to erase his {{clarify span|Georgian facial characteristics|date=April 2021}}<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.thevintagenews.com/2015/07/30/10-facts-you-didnt-know-about-stalin/ |title=10 Facts You Didn't Know About Stalin |last=Smithfield |first=Brad |date=30 July 2015 |website=The Vintage News |publisher=Timera Media |access-date=23 April 2021 |quote=had his likeness softened on propaganda posters to reduce his Georgian facial characteristics.}}</ref> and make him a more generalized Soviet hero. Only his eyes and famous moustache remained unaltered. ] and ] say his "majestic new image was devised appropriately to depict the leader of all times and of all peoples."<ref>{{cite book|author=Zhores A. Medvedev and |title=The Unknown Stalin|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=v3BrNF80AzUC&pg=PA248|year=2003|page=248|publisher=I.B. Tauris |isbn=9781860647680}}</ref> | |||

| Article 20 of the ] prohibits any propaganda for war as well as any advocacy of national or religious hatred that constitutes ] to discrimination, hostility or violence by law.<ref>{{cite web|title=International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights|url=http://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/ccpr.aspx|website=United Nations Human Rights: Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights|publisher=United Nations|access-date=2 September 2015}}</ref> | |||

| ;] | |||

| :People desire to be consistent. Suppose a pollster finds that a certain group of people hates his candidate for senator but loves actor A. They use actor A's endorsement of their candidate to change people's minds because people cannot tolerate inconsistency. They are forced to either to dislike the actor or like the candidate. | |||

| {{blockquote|Naturally, the common people don't want war; neither in Russia nor in England nor in America, nor for that matter in Germany. That is understood. But, after all, it is the leaders of the country who determine the policy and it is always a simple matter to drag the people along, whether it is a democracy or a fascist dictatorship or a Parliament or a Communist dictatorship. The people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders. That is easy. All you have to do is tell them they are being attacked and denounce the pacifists for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same way in any country.|]<ref>]'s ''Nuremberg Diary''(1947). In an interview with Gilbert in Göring's jail cell during the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials (18 April 1946)</ref>}}Simply enough the covenant specifically is not defining the content of propaganda. In simplest terms, an act of propaganda if used in a reply to a wartime act is not prohibited.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Snow|first=Nacny|title=US Propaganda|journal=American Thought and Culture in the 21st Century|pages=97–98}}</ref> | |||

| ;Common man | |||

| :"The "plain folks" or "common man" approach attempts to convince the audience that the propagandist's positions reflect the common sense of the people. It is designed to win the confidence of the audience by communicating in the common manner and style of the target audience. Propagandists use ordinary language and mannerisms (and clothe their message in face-to-face and audiovisual communications) in attempting to identify their point of view with that of the average person. With the plain folks device, the propagandist can win the confidence of persons who resent or distrust foreign sounding, intellectual speech, words, or mannerisms."<ref>{{cite book|title=Psychological Operations Field Manual No.33-1|year=1979|publisher=Headquarters; Department of the Army|location=Washington DC}}</ref> For example, a politician speaking to a Southern United States crowd might incorporate words such as "]" and other ]s to create a perception of belonging. | |||

| ===Advertising=== | |||

| ;] | |||

| :A cult of personality arises when an individual uses mass media to create an idealized and heroic public image, often through unquestioning flattery and praise. The hero personality then advocates the positions that the propagandist desires to promote. For example, modern propagandists hire popular personalities to promote their ideas and/or products. | |||

| Propaganda shares techniques with advertising and ], each of which can be thought of as propaganda that promotes a commercial product or shapes the perception of an organization, person, or brand. For example, after claiming victory in the ], ] campaigned for broader popularity among Arabs by organizing mass rallies where Hezbollah leader ] combined elements of the local ] with ] to reach audiences outside Lebanon. Banners and billboards were commissioned in commemoration of the war, along with various merchandise items with Hezbollah's logo, flag color (yellow), and images of Nasrallah. T-shirts, baseball caps and other war memorabilia were marketed for all ages. The uniformity of messaging helped define Hezbollah's brand.<ref>{{cite book |last=Khatib |first=Lina |author-link=Lina Khatib |title=The Hizbullah Phenomenon: Politics and Communication |publisher=Oxford University Press |date=2014 |page=84}}</ref> | |||

| ;] | |||

| :Making individuals from the opposing nation, from a different ethnic group, or those who support the opposing viewpoint appear to be subhuman (e.g., the ]-era term "gooks" for ] aka Vietcong, or "VC", soldiers), worthless, or immoral, through suggestion or false accusations. ] is also a termed used synonymously with demonizing, the latter usually serves as an aspect of the former. | |||

| In the journalistic context, advertisements evolved from the traditional commercial advertisements to include also a new type in the form of paid articles or broadcasts disguised as news. These generally present an issue in a very subjective and often misleading light, primarily meant to persuade rather than inform. Normally they use only subtle ] and not the more obvious ones used in traditional commercial advertisements. If the reader believes that a paid advertisement is in fact a news item, the message the advertiser is trying to communicate will be more easily "believed" or "internalized". Such advertisements are considered obvious examples of "covert" propaganda because they take on the appearance of objective information rather than the appearance of propaganda, which is misleading. Federal law{{where|date=April 2021}} specifically mandates that any advertisement appearing in the format of a news item must state that the item is in fact a paid advertisement. | |||

| ], urging Americans to buy ]s]] | |||

| ;] | |||

| :This technique hopes to simplify the decision making process by using images and words to tell the audience exactly what actions to take, eliminating any other possible choices. Authority figures can be used to give the order, overlapping it with the ] technique, but not necessarily. The ] "I want you" image is an example of this technique. | |||

| Edmund McGarry illustrates that advertising is more than selling to an audience but a type of propaganda that is trying to persuade the public and not to be balanced in judgement.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=McGarry|first=Edmund D.|date=1958|title=The Propaganda Function in Marketing|journal=Journal of Marketing|volume=23|issue=2|pages=131–132|doi=10.2307/1247829|jstor=1247829}}</ref> | |||

| ;] | |||

| :The creation or deletion of information from public records, in the purpose of making a false record of an event or the actions of a person or organization, including outright ] of photographs, motion pictures, broadcasts, and sound recordings as well as printed documents. | |||

| ===Politics=== | |||

| ;] | |||

| :Is used to increase a person's latitude of acceptance. For example, if a salesperson wants to sell an item for $100 but the public is only willing to pay $50, the salesperson first offers the item at a higher price (e.g., $200) and subsequently reduces the price to $100 to make it seem like a good deal. | |||

| ] can be found in television, and in ] that influence mass audiences. An example was the '']'' (Journal) news cast, which criticised ] in the then-communist ] using ].]] | |||

| ;] | |||

| :The use of an event that generates euphoria or happiness, or using an appealing event to boost morale. Euphoria can be created by declaring a holiday, making luxury items available, or mounting a military parade with marching bands and patriotic messages. | |||

| Propaganda has become more common in political contexts, in particular, to refer to certain efforts sponsored by governments, political groups, but also often covert interests. In the early 20th century, propaganda was exemplified in the form of party slogans. Propaganda also has much in common with ] campaigns by governments, which are intended to encourage or discourage certain forms of behavior (such as wearing seat belts, not smoking, not littering, and so forth). Again, the emphasis is more political in propaganda. Propaganda can take the form of ], posters, TV, and radio broadcasts and can also extend to any other ]. In the case of the United States, there is also an important legal (imposed by law) distinction between advertising (a type of overt propaganda) and what the ] (GAO), an arm of the United States Congress, refers to as "covert propaganda." Propaganda is divided into two in political situations, they are preparation, meaning to create a new frame of mind or view of things, and operational, meaning they instigate actions.<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_03PpagDaUsC |title=How to Be a Spy: The World War II SOE Training Manual |publisher=Dundurn Press |year=2004 |isbn=978-1-55002-505-7 |location=Toronto |pages=192 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ;] | |||

| :An attempt to influence public perception by disseminating negative and dubious/false information designed to undermine the credibility of their beliefs. | |||

| Roderick Hindery argues<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://propagandaandcriticalthought.com/author/rhindery/|title=About Roderick Hindery|website=Propaganda and Critical Thought Blog|access-date=4 December 2019|archive-date=2 December 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201202221732/https://propagandaandcriticalthought.com/author/rhindery/|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | last=Hindery | first=Roderick | title=Indoctrination and self-deception or free and critical thought | publisher=] | location=] | year=2001 | isbn=0-7734-7407-2 | oclc=45784333 }}</ref> that propaganda exists on the political left, and right, and in mainstream centrist parties. Hindery further argues that debates about most social issues can be productively revisited in the context of asking "what is or is not propaganda?" Not to be overlooked is the link between propaganda, indoctrination, and terrorism/]. He argues that threats to destroy are often as socially disruptive as physical devastation itself. | |||

| ] - personification of Finnish nationalism]] | |||

| ;Flag-waving | |||

| :An attempt to justify an action on the grounds that doing so will make one more patriotic, or in some way benefit a country, group or idea the targeted audience supports. | |||

| Since ] and the appearance of greater media fluidity, propaganda institutions, practices and legal frameworks have been evolving in the US and Britain. Briant shows how this included expansion and integration of the apparatus cross-government and details attempts to coordinate the forms of propaganda for foreign and domestic audiences, with new efforts in ].<ref>{{cite journal|first1=Emma Louise |last1=Briant|title=Allies and Audiences Evolving Strategies in Defense and Intelligence Propaganda|journal=The International Journal of Press/Politics|date=April 2015|volume=20|issue=2|pages=145–165|doi=10.1177/1940161214552031|s2cid=145697213}}</ref> These were subject to contestation within the ], resisted by ] ] and critiqued by some scholars.<ref name=Briant2015/> The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2013 (section 1078 (a)) amended the US Information and Educational Exchange Act of 1948 (popularly referred to as the ]) and the Foreign Relations Authorization Act of 1987, allowing for materials produced by the State Department and the ] (BBG) to be released within U.S. borders for the Archivist of the United States. The Smith-Mundt Act, as amended, provided that "the Secretary and the Broadcasting Board of Governors shall make available to the Archivist of the United States, for domestic distribution, motion pictures, films, videotapes, and other material 12 years after the initial dissemination of the material abroad (...) Nothing in this section shall be construed to prohibit the Department of State or the Broadcasting Board of Governors from engaging in any medium or form of communication, either directly or indirectly, because a United States domestic audience is or may be thereby exposed to program material, or based on a presumption of such exposure." Public concerns were raised upon passage due to the relaxation of prohibitions of domestic propaganda in the United States.<ref>{{cite web|title=Smith-Mundt Act|url=https://www.techdirt.com/articles/20130715/11210223804/anti-propaganda-ban-repealed-freeing-state-dept-to-direct-its-broadcasting-arm-American-citizens.shtml|website='Anti-Propaganda' Ban Repealed, Freeing State Dept. To Direct Its Broadcasting Arm at American Citizens|date=15 July 2013 |publisher=Techdirt|access-date=1 June 2016}}</ref> | |||

| ;] | |||

| :Often used by recruiters and salesmen. For example, a member of the opposite sex walks up to the victim and pins a flower or gives a small gift to the victim. The victim says thanks and now they have incurred a psychological debt to the perpetrator. The person eventually asks for a larger favor (e.g., a donation or to buy something far more expensive). The unwritten social contract between the victim and perpetrator causes the victim to feel obligated to reciprocate by agreeing to do the larger favor or buy the more expensive gift. | |||

| In the wake of this, the internet has become a prolific method of distributing political propaganda, benefiting from an evolution in coding called bots. ]s or ] can be used for many things, including populating social media with ] and posts with a range of sophistication. During the ] a cyber-strategy was implemented using bots to direct US voters to Russian political news and information sources, and to spread politically motivated rumors and false news stories. At this point it is considered commonplace contemporary political strategy around the world to implement bots in achieving political goals.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Howard|first1=Philip N.|last2=Woolley|first2=Samuel|last3=Calo|first3=Ryan|date=3 April 2018|title=Algorithms, bots, and political communication in the US 2016 election: The challenge of automated political communication for election law and administration|journal=Journal of Information Technology & Politics|volume=15|issue=2|pages=81–93|doi=10.1080/19331681.2018.1448735|issn=1933-1681|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| ;] | |||