| Revision as of 03:23, 9 February 2006 editRan (talk | contribs)17,293 edits →Today← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 14:52, 27 December 2024 edit undoSwinub (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users66,038 edits Removed extra spacing | ||

| (822 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Two approximate mega-regions within China}} | |||

| ''Alternative meaning: In ], ] and ] were two ancient landmasses that correspond to modern northern and southern ].'' | |||

| {{Distinguish|North China|South China|Northern and Southern dynasties}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=December 2019}} | |||

| '''Northern China''' ({{zh|s = 中国北方 or 中国北部|l = China's North}}) and '''Southern China''' ({{zh|s = 中国南方 or 中国南部|l = China's South |links = no}}){{NoteTag|Also referred to in China as simply '''the north''' ({{zh|c = ]|p = Běifāng|links = no}}) and '''the south''' ({{zh|c = ]|p = Nánfāng|links = no}}).}} are two approximate regions that display certain differences in terms of their geography, demographics, economy, and culture. | |||

| ---- | |||

| '''Northern China''' (北方 ]: Běifāng) and '''Southern China''' (南方 ]: Nánfāng) are two approximate regions within ]. The exact boundary between these two regions has never been precisely defined. Nevertheless, the self-perception of ], especially regional ]s, has often been dominated by these two concepts. | |||

| == Extent == | == Extent == | ||

| ] | |||

| The ] serve as the transition zone between northern and southern China. They approximately coincide with the 0 degree Celsius ] in January, the {{convert|800|mm|in}} ], and the 2,000-hour sunshine duration contour.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Lan |first=Xincan |last2=Li |first2=Wuyang |last3=Tang |first3=Jiale |last4=Shakoor |first4=Abdul |last5=Zhao |first5=Fang |last6=Fan |first6=Jiabin |date=2022-04-28 |title=Spatiotemporal variation of climate of different flanks and elevations of the Qinling–Daba mountains in China during 1969–2018 |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-10819-3 |journal=Scientific Reports |language=en |volume=12 |issue=1 |doi=10.1038/s41598-022-10819-3 |issn=2045-2322 |pmc=9050673 |pmid=35484392}}</ref> The ] basin serves a similar role,<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Yin |first=Yixing |last2=Chen |first2=Haishan |last3=Wang |first3=Guojie |last4=Xu |first4=Wucheng |last5=Wang |first5=Shenmin |last6=Yu |first6=Wenjun |date=2021-05-01 |title=Characteristics of the precipitation concentration and their relationship with the precipitation structure: A case study in the Huai River basin, China |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0169809521000363 |journal=Atmospheric Research |volume=253 |pages=105484 |doi=10.1016/j.atmosres.2021.105484 |issn=0169-8095}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Xia |first=Jun |last2=Zhang |first2=Yongyong |last3=Zhao |first3=Changsen |last4=Bunn |first4=Stuart E. |date=August 2014 |title=Bioindicator Assessment Framework of River Ecosystem Health and the Detection of Factors Influencing the Health of the Huai River Basin, China |url=https://ascelibrary.org/doi/10.1061/%28ASCE%29HE.1943-5584.0000989 |journal=Journal of Hydrologic Engineering |language=en |volume=19 |issue=8 |doi=10.1061/(ASCE)HE.1943-5584.0000989 |issn=1084-0699|hdl=10072/66836 |hdl-access=free }}</ref> and the ] has been used to set different policies to the north and the south.<ref>{{Cite web |title=China’s Huai River Policy and Population Migration: A U-Shaped Relationship – Nova Science Publishers |url=https://novapublishers.com/shop/chinas-huai-river-policy-and-population-migration-a-u-shaped-relationship/ |access-date=2024-09-02 |language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| The boundary between northern and southern China is generally defined to be the ] and ] (Huai He). In the eastern provinces like ] and ], however, the ] is usually perceived as the north-south boundary instead of the Huai River. There is an ambiguous area, the region around ], ], that lies in the gap where the Qinling has ended and the Huai River has not yet begun; in addition, central Anhui and Jiangsu lie south of the Huai River but north of the Yangtze, making their classification somewhat ambiguous as well. As such, the boundary between northern and southern China does not follow provincial boundaries; it cuts through ], ], ], and ], and creates areas such as ] (]), ] (]), and ] (]) that lie on an opposite half of China from the rest of their respective provinces. This may have been deliberate; the ] ] and ] ] established many of these boundaries intentionally to discourage regionalist ]. | |||

| Areas often thought as being outside "]", such as ], ], and ], are also conceived as belonging to either northern and southern China according to the framework above. ] and ] are, however, not usually conceived of being part of either north or south. | |||

| == History == | == History == | ||

| ], while ] is more prevalent in the south.]] | |||

| {{See also|Southward expansion of the Han dynasty}} | |||

| Historically, populations migrated from the north to the south, especially its coastal areas and along major rivers.<ref name=":3">{{Cite web |title=Weekend Long Read: Why China’s North-South Economic Gap Keeps Getting Bigger - Caixin Global |url=https://www.caixinglobal.com/2021-01-02/weekend-long-read-why-chinas-north-south-economic-gap-keeps-getting-bigger-101645586.html |access-date=2024-08-27 |website=www.caixinglobal.com |language=en}}</ref><ref name=":22">{{Cite book |last=Xuefeng |first=He |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QupZEAAAQBAJ&dq=china+south+north+southern+northern&pg=PT29 |title=Northern and Southern China: Regional Differences in Rural Areas |date=2022-03-07 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-000-40262-9 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ].]] | |||

| The concepts of northern and southern China originate from differences in ], ], ], and physical traits; as well as several periods of actual political division in history. Northern China is too cold and dry for ] cultivation (though it does happen today with modern technology) and consists largely of flat plains, grasslands, and desert; while Southern China is warm and rainy enough for rice and consists of lush mountains cut by river valleys. In addition, Northern Chinese trace some of their ancestry to ] peoples such as the ]s and ]s, while Southern Chinese trace some of their ancestry to ], ], and ] peoples related to modern ]s, ] and other Southeast Asian ethnic groups; this results in obvious differences in physical trait. (Internal migration within China, however, has greatly blurred such differences.) There are also major differences in ], ], and ]. | |||

| After the fall of the ], The ] (420–589) ruled their respective part of China before re-uniting under the ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Lewis |first=Mark Edward |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6IkpEAAAQBAJ&q=china+south+north+southern+northern |title=China Between Empires: The Northern and Southern Dynasties |date=2011-04-30 |publisher=Harvard University Press |isbn=978-0-674-06035-7 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Episodes of division into North and South include: | |||

| During the ], regional differences and identification in China fostered the growth of regional stereotypes. Such stereotypes often appeared in historic ]s and ]s and were based on geographic circumstances, historical and literary associations (e.g. people from ], were considered upright and honest) and ] (as the south was associated with the fire element, Southerners were considered hot-tempered).<ref name="smith">{{cite book|last = Smith|first=Richard Joseph|title = China's cultural heritage: the Qing dynasty, 1644–1912|publisher = Westview Press|year = 1994|edition = 2|isbn = 978-0-8133-1347-4}}</ref> These differences were reflected in Qing dynasty policies, such as the prohibition on local officials to serve their home areas, as well as conduct of personal and commercial relations.<ref name="smith" /> In 1730, the ] made the observation in the ''Tingxun Geyan'' (庭訓格言):<ref name="smith" /><ref>{{cite journal |last = Hanson |first = Marta E. |date = July 2007 |title = Jesuits and Medicine in the Kangxi Court (1662–1722) |journal = Pacific Rim Report |publisher = Center for the Pacific Rim, University of San Francisco |location = San Francisco |issue = 43 |pages = 7, 10 |url = http://usf.usfca.edu/ricci/research/pacrimreport/prr43.pdf |access-date = 12 July 2011 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20120319220859/http://usf.usfca.edu/ricci/research/pacrimreport/prr43.pdf |archive-date = 19 March 2012 |url-status = dead }}</ref> | |||

| *] (]-]) | |||

| {{blockquote|The people of the North are strong; they must not copy the fancy diets of the Southerners, who are physically frail, live in a different environment, and have different stomachs and bowels.|the Kangxi Emperor|''Tingxun Geyan'' (《庭訓格言》)}} | |||

| *] (]-]) and ] (]-]) | |||

| *] (]-]) | |||

| *] (]-]) and ] (]-]) | |||

| The Southern and Northern Dynasties showed such a high level of polarization between North and South that northerners and southerners referred to each other as barbarians; the ] ] also made use of the concept by dividing ] into two ]s: a higher caste of northerners and a lower caste of southerners. (These were the second-lowest and lowest castes of the ].) | |||

| During the ], ], a major Chinese writer, wrote:<ref name="young">{{cite journal |last = Young |first = Lung-Chang |date = Summer 1988 |title = Regional Stereotypes in China |journal = Chinese Studies in History |volume = 21 |issue = 4 |pages = 32–57 |url = http://mesharpe.metapress.com/link.asp?id=4v458w761m068r0t |archive-url = https://archive.today/20130129010939/http://mesharpe.metapress.com/link.asp?id=4v458w761m068r0t |url-status = dead |archive-date = 29 January 2013 |doi = 10.2753/csh0009-4633210432 }}</ref> | |||

| {{blockquote|According to my observation, Northerners are sincere and honest; Southerners are skilled and quick-minded. These are their respective virtues. Yet sincerity and honesty lead to stupidity, whereas skillfulness and quick-mindedness lead to duplicity.|]|''Complete works of Lu Xun'' (《魯迅全集》), pp. 493–495.}} | |||

| == Today == | == Today == | ||

| ] | |||

| ⚫ | ] in 2004. The disparity in terms of wealth runs in the east–west direction rather than the north–south direction. However, the southeast coast is still wealthier than the northeast coast in ''per capita'' terms.]] | ||

| === Climate === | |||

| Northern regions of China have long winters that are cold and dry, often below freezing, and long summers that are hot and humid.<ref name=":1">{{Cite web |title=Regions of Chinese food-styles/flavors of cooking |url=http://www.kas.ku.edu/service-learning/projects/chinese_food/regional_cuisine.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090416203009/http://www.kas.ku.edu:80/service-learning/projects/chinese_food/regional_cuisine.html |archive-date=April 16, 2009 |website=regional cuisines}}</ref> Transitional periods are short. The ecology is simple and not resilient to droughts.<ref name=":22" /> | |||

| Many southern regions are ] and green year round. The winters are short. They often experience typhoons and the ] in the summer.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Zhu |first=Hua |date=2017-03-01 |title=The Tropical Forests of Southern China and Conservation of Biodiversity |url=https://doi.org/10.1007/s12229-017-9177-2 |journal=The Botanical Review |language=en |volume=83 |issue=1 |pages=87–105 |doi=10.1007/s12229-017-9177-2 |bibcode=2017BotRv..83...87Z |issn=1874-9372 |s2cid=29536766}}</ref> The ecology is complex, and floods are more common.<ref name=":22" /> | |||

| === Diet and produce === | |||

| The northern regions are easier to ].<ref name=":22" /> Hardy crops such as ], ], ], and ] are grown, and one to two crops are produced each year.<ref name="smith" /> The growing season lasts four to six months. Wheat-based food such as bread, ], and noodles are more common.<ref name="eberhard">{{cite journal |last=Eberhard |first=Wolfram |date=December 1965 |title=Chinese Regional Stereotypes |journal=Asian Survey |publisher=University of California Press |volume=5 |issue=12 |pages=596–608 |doi=10.2307/2642652 |jstor=2642652}}</ref><ref name=":1" /> | |||

| Cultivation of the southern regions began later in history.<ref name=":22" /> Warm temperatures and abundant rainfall help produce ] and ].<ref name=":1" /> Two to three crops can be grown each year, and the growing season lasts nine to twelve months.<ref name="smith" /> Rice-based food is more common.<ref name="eberhard" /><ref name=":1" /> | |||

| === Language and people === | |||

| Jones Lamprey, a British army surgeon in 1868,<ref>{{Cite web |title=Jones Lamprey {{!}} Historical Photographs of China |url=https://hpcbristol.net/visual/rh03-08 |access-date=2023-11-17 |website=hpcbristol.net}}</ref> writes that northerners have lighter skin tones than southerners, although the shade can change greatly from season to season depending on an individual's exposure to sunlight when performing manual labor outdoors.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal |last=Lamprey |first=J. |date=1868 |title=A Contribution to the Ethnology of the Chinese |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/3014248 |journal=Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London |volume=6 |pages=101–108 |doi=10.2307/3014248 |issn=1368-0366 |jstor=3014248}}</ref> Northerners are often taller than southerners.<ref name="lu">{{cite journal |last1=Lu |first1=Guoguang |last2=Yang |first2=Zhihui |last3=Zhang |first3=Yan |last4=Lu |first4=Shengxu |last5=Gong |first5=Siyuan |last6=Li |first6=Tingting |last7=Shen |first7=Yijie |last8=Zhang |first8=Sihan |last9=Zhuang |first9=Hanya |date=2022 |title=Geographic latitude and human height - Statistical analysis and case studies from China |journal=Arabian Journal of Geosciences |volume=15 |issue=335 |doi=10.1007/s12517-021-09335-x |doi-access=free|bibcode=2022ArJG...15..335L }}</ref> | |||

| Variants of ] are widely spoken in northern regions and often with a ] accent.<ref name=":22" /><ref name=":0" /> Ethnic groups are comparatively more diverse in southern regions.<ref name="smith" /> Rhotic accent is usually absent from the Mandarin spoken there. Different dialects are less mutually intelligible, and additional languages such as ] or ] are spoken.<ref name=":0" /> Patrilineage organizations are larger and more integrated in rural southern regions, possibly due to merges and competition for territory.<ref name=":22" /> | |||

| A series of studies on regional differences in China suggest that people from places that grow wheat have different social styles and thought styles from those in rice-growing regions.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Talhelm |first1=Thomas |last2=Dong |first2=Xiawei |date=2024-02-27 |title=People quasi-randomly assigned to farm rice are more collectivistic than people assigned to farm wheat |journal=Nature Communications |language=en |volume=15 |issue=1 |pages=1782 |doi=10.1038/s41467-024-44770-w |pmid=38413584 |pmc=10899190 |bibcode=2024NatCo..15.1782T |issn=2041-1723}}</ref><ref name="TaSci">{{Cite journal |last1=Talhelm |first1=T. |last2=Zhang |first2=X. |last3=Oishi |first3=S. |last4=Shimin |first4=C. |last5=Duan |first5=D. |last6=Lan |first6=X. |last7=Kitayama |first7=S. |date=2014-05-09 |title=Large-Scale Psychological Differences Within China Explained by Rice Versus Wheat Agriculture |url=https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1246850 |journal=Science |language=en |volume=344 |issue=6184 |pages=603–608 |doi=10.1126/science.1246850 |pmid=24812395 |bibcode=2014Sci...344..603T |issn=0036-8075}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Talhelm |first1=Thomas |last2=Zhang |first2=Xuemin |last3=Oishi |first3=Shigehiro |date=2018-04-06 |title=Moving chairs in Starbucks: Observational studies find rice-wheat cultural differences in daily life in China |journal=Science Advances |language=en |volume=4 |issue=4 |pages=eaap8469 |doi=10.1126/sciadv.aap8469 |issn=2375-2548 |pmc=5916507 |pmid=29707634|bibcode=2018SciA....4.8469T }}</ref> Respondents from northern China are found to be more individualistic, think more analytically, and more open to strangers. Those from the southern regions are more likely to think holistically, interdependent, and draw a larger distinction between friends and strangers. The difference was attributed to the growing of rice, which often requires the sharing labor and managing shared irrigation infrastructure.<ref name="TaSci"/><ref>{{Cite book |last1=Talhelm |first1=Thomas |title=Socio-Economic Environment and Human Psychology: Social, Ecological, and Cultural Perspectives |last2=Oishi |first2=Shigehiro |date=2018 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=9780190492908 |editor-last=Uskul |editor-first=Ayse |location=New York, NY |publication-date=2018 |pages=53–76 |language=English |chapter=How Rice Farming Shaped Culture in Southern China |doi=10.1093/oso/9780190492908.003.0003 |lccn=2017046499 |ssrn=3199657}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Bray |first=Francesca |url=https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520086203/the-rice-economies |title=The Rice Economies: Technology and Development in Asian Societies |date=1994 |publisher=University of California Press |isbn=978-0-520-08620-3 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | ]. |

||

| In modern times, North and South is merely one of the ways that Chinese people identify themselves, and the divide between northern and southern China has been overridden both by a unified ] and as well as by local loyalities to province, county and village which prevent a coherent Northern or Southern identity from forming. | |||

| === Transportation === | |||

| Few ] (with the notable exception of ]ese politician ]) would consider the difference between North and South sufficient reason for political division. During the ] reforms of the ], South China initially developed much more quickly than North China leading some scholars to wonder whether the economic fault line would create political tension between north and south. Some of this was based on the idea that there would be conflict between the bureaucratic north and the commercial south. This has not occurred in part because the economic faultlines eventually created divisions between coastal China and the interior, as well as urban and rural China, which run in different directions from the north-south division, and in part because neither north or south has any type of obvious advantage within the Chinese central government. In addition there are other cultural divisions that exist within and across the north-south barrier. | |||

| Traveling between places tends to be easier in northern regions where the terrain is more even.<ref name=":22" /> | |||

| == |

=== Economy === | ||

| As China modernized, the north initially developed faster due to ], ], and its concentration of construction and resource extraction industries. After ], however, the south took the lead due to manufacturing and eventually high-tech industries, as well as continued internal migration into the region.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

| ===Health=== | |||

| Nevertheless, the concepts of North and South continue to play an important role in regional ]s. | |||

| A research showed that ] was slightly higher in Southern China compared to Northern China. In 2018, it was 76.66 years for North and 77.35 for South.<ref>{{cite web | url =https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6e52/52d60901b36c13bebf06e724430b11aa4dd1.pdf | title =Why Residents in Southern China Live Longer Than Those in Northern China? |website = Semantic Scholar| author1= Mengqi Wang| author2=Yi Huangyi | date=September 18, 2020 | access-date =October 14, 2024| quote = Table 1, Page number 2}}</ref> According to the data from a survey in 2011, people in Southern China were 10.51% less likely to be ] and overweight compared to the North.<ref>{{cite web | url =https://www.researchgate.net/publication/346142786_Differences_in_Overweight_and_Obesity_between_the_North_and_South_of_China&ved=2ahUKEwjStpSp6IyJAxXvTGwGHUNaD-wQFnoECBwQAQ&usg=AOvVaw3z8sr0X0aFOJalT6HIxCDJ| title =Differences in Overweight and Obesity between the North and South of China |author1=Daisheng Tang |author2 = Tao Bu | website = Research gate | date= 2020| access-date =October 14, 2024| quote =Page number 789, Paragraph 2}}</ref> | |||

| == See also == | |||

| The stereotypical northerner: | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == Notes == | |||

| *Is taller and has a longer rugged face (possibly with considerably more facial hair than southerners) | |||

| {{NoteFoot}} | |||

| *Speaks a northern ] | |||

| *Eats ]-based food rather than ]-based food | |||

| *Is loud, boisterous, open, and prone to "thunderbolt" displays of emotion, such as anger | |||

| *More used to sitting than squatting | |||

| == References == | |||

| The stereotypical southerner: | |||

| === Citations === | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| == Further reading == | |||

| *Is shorter and has a smooth, round face (more than likely, no facial hair) | |||

| {{refbegin}} | |||

| *Speaks a southern ] such as Yue (]), ], or ] | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Brues |first=Alice Mossie |title=People and Races |publisher=Macmillan |location=New York, NY |year=1977 |series=Macmillan series in physical anthropology |isbn=978-0-02-315670-0 |url=https://archive.org/details/peopleraces0000brue}} | |||

| *Eats ]-based food rather than ]-based food | |||

| * {{Cite journal |last1=Du |first1=Ruofu |last2=Yuan |first2=Yida |last3=Hwang |first3=Juliana |last4=Mountain |first4=Joanna |last5=Cavalli-Sforza |first5=L. Luca |date=1992 |title=Chinese Surnames and the Genetic Differences between North and South China |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/23825835 |journal=Journal of Chinese Linguistics Monograph Series |issue=5 |pages=1–93 |jstor=23825835 |issn=2409-2878}} | |||

| *Is clever, calculating, hardworking, and prone to "mincemeat" displays of emotion, such as brooding melancholy | |||

| * ]; Liu, Kwang-chang. (1999). ''The Cambridge Illustrated History of China''. Cambridge University Press. | |||

| *More used to squatting than sitting | |||

| * {{Cite journal |last=Morgan |first=Stephen L. |date=2000 |title=Richer and Taller: Stature and Living Standards in China, 1979-1995 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/2667475 |journal=The China Journal |issue=44 |pages=1–39 |doi=10.2307/2667475 |jstor=2667475 |pmid=18411497 |issn=1324-9347}} | |||

| *Spits in public | |||

| * Muensterberger, Warner (1951). "Orality and Dependence: Characteristics of Southern Chinese." In ''Psychoanalysis and the Social Sciences'', (3), ed. Geza Roheim (New York: International Universities Press). | |||

| *Wears sandals with white blouses and black pants | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| *Has a wet comb-over with glasses | |||

| {{China topics}} | |||

| Note that these are very rough stereotypes, and are greatly complicated both by further stereotypes by province (or even ]) and by real life. | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

Latest revision as of 14:52, 27 December 2024

Two approximate mega-regions within China Not to be confused with North China, South China, or Northern and Southern dynasties.

Northern China (Chinese: 中国北方 or 中国北部; lit. 'China's North') and Southern China (Chinese: 中国南方 or 中国南部; lit. 'China's South') are two approximate regions that display certain differences in terms of their geography, demographics, economy, and culture.

Extent

The Qinling–Daba Mountains serve as the transition zone between northern and southern China. They approximately coincide with the 0 degree Celsius isotherm in January, the 800 millimetres (31 in) isohyet, and the 2,000-hour sunshine duration contour. The Huai River basin serves a similar role, and the course of the Huaihe has been used to set different policies to the north and the south.

History

Historically, populations migrated from the north to the south, especially its coastal areas and along major rivers.

After the fall of the Han dynasty, The Southern and Northern Dynasties (420–589) ruled their respective part of China before re-uniting under the Tang dynasty.

During the Qing dynasty, regional differences and identification in China fostered the growth of regional stereotypes. Such stereotypes often appeared in historic chronicles and gazetteers and were based on geographic circumstances, historical and literary associations (e.g. people from Shandong, were considered upright and honest) and Chinese cosmology (as the south was associated with the fire element, Southerners were considered hot-tempered). These differences were reflected in Qing dynasty policies, such as the prohibition on local officials to serve their home areas, as well as conduct of personal and commercial relations. In 1730, the Kangxi Emperor made the observation in the Tingxun Geyan (庭訓格言):

The people of the North are strong; they must not copy the fancy diets of the Southerners, who are physically frail, live in a different environment, and have different stomachs and bowels.

— the Kangxi Emperor, Tingxun Geyan (《庭訓格言》)

During the Republican period, Lu Xun, a major Chinese writer, wrote:

According to my observation, Northerners are sincere and honest; Southerners are skilled and quick-minded. These are their respective virtues. Yet sincerity and honesty lead to stupidity, whereas skillfulness and quick-mindedness lead to duplicity.

— Lu Xun, Complete works of Lu Xun (《魯迅全集》), pp. 493–495.

Today

Climate

Northern regions of China have long winters that are cold and dry, often below freezing, and long summers that are hot and humid. Transitional periods are short. The ecology is simple and not resilient to droughts.

Many southern regions are subtropical and green year round. The winters are short. They often experience typhoons and the East Asian monsoon in the summer. The ecology is complex, and floods are more common.

Diet and produce

The northern regions are easier to cultivate. Hardy crops such as corn, sorghum, soybeans, and wheat are grown, and one to two crops are produced each year. The growing season lasts four to six months. Wheat-based food such as bread, dumplings, and noodles are more common.

Cultivation of the southern regions began later in history. Warm temperatures and abundant rainfall help produce rice and tropical fruits. Two to three crops can be grown each year, and the growing season lasts nine to twelve months. Rice-based food is more common.

Language and people

Jones Lamprey, a British army surgeon in 1868, writes that northerners have lighter skin tones than southerners, although the shade can change greatly from season to season depending on an individual's exposure to sunlight when performing manual labor outdoors. Northerners are often taller than southerners.

Variants of Mandarin are widely spoken in northern regions and often with a rhotic accent. Ethnic groups are comparatively more diverse in southern regions. Rhotic accent is usually absent from the Mandarin spoken there. Different dialects are less mutually intelligible, and additional languages such as Cantonese or Hokkien are spoken. Patrilineage organizations are larger and more integrated in rural southern regions, possibly due to merges and competition for territory.

A series of studies on regional differences in China suggest that people from places that grow wheat have different social styles and thought styles from those in rice-growing regions. Respondents from northern China are found to be more individualistic, think more analytically, and more open to strangers. Those from the southern regions are more likely to think holistically, interdependent, and draw a larger distinction between friends and strangers. The difference was attributed to the growing of rice, which often requires the sharing labor and managing shared irrigation infrastructure.

Transportation

Traveling between places tends to be easier in northern regions where the terrain is more even.

Economy

As China modernized, the north initially developed faster due to planned economic policies, Soviet aid, and its concentration of construction and resource extraction industries. After market reforms, however, the south took the lead due to manufacturing and eventually high-tech industries, as well as continued internal migration into the region.

Health

A research showed that life expectancy was slightly higher in Southern China compared to Northern China. In 2018, it was 76.66 years for North and 77.35 for South. According to the data from a survey in 2011, people in Southern China were 10.51% less likely to be obese and overweight compared to the North.

See also

- Cultural regions in China

- List of regions of China

- Nanquan (Southern Fist)

- Global North and Global South

- North–South divide in Taiwan

Notes

- Also referred to in China as simply the north (Chinese: 北方; pinyin: Běifāng) and the south (Chinese: 南方; pinyin: Nánfāng).

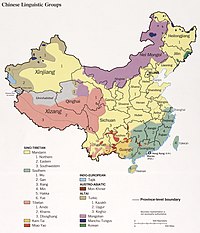

- The map shows the distribution of linguistic groups according to historical majority ethnic groups, which may have shifted due to prolonged internal migration and assimilation.

References

Citations

- Lan, Xincan; Li, Wuyang; Tang, Jiale; Shakoor, Abdul; Zhao, Fang; Fan, Jiabin (28 April 2022). "Spatiotemporal variation of climate of different flanks and elevations of the Qinling–Daba mountains in China during 1969–2018". Scientific Reports. 12 (1). doi:10.1038/s41598-022-10819-3. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 9050673. PMID 35484392.

- Yin, Yixing; Chen, Haishan; Wang, Guojie; Xu, Wucheng; Wang, Shenmin; Yu, Wenjun (1 May 2021). "Characteristics of the precipitation concentration and their relationship with the precipitation structure: A case study in the Huai River basin, China". Atmospheric Research. 253: 105484. doi:10.1016/j.atmosres.2021.105484. ISSN 0169-8095.

- Xia, Jun; Zhang, Yongyong; Zhao, Changsen; Bunn, Stuart E. (August 2014). "Bioindicator Assessment Framework of River Ecosystem Health and the Detection of Factors Influencing the Health of the Huai River Basin, China". Journal of Hydrologic Engineering. 19 (8). doi:10.1061/(ASCE)HE.1943-5584.0000989. hdl:10072/66836. ISSN 1084-0699.

- "China's Huai River Policy and Population Migration: A U-Shaped Relationship – Nova Science Publishers". Retrieved 2 September 2024.

- ^ "Weekend Long Read: Why China's North-South Economic Gap Keeps Getting Bigger - Caixin Global". www.caixinglobal.com. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ Xuefeng, He (7 March 2022). Northern and Southern China: Regional Differences in Rural Areas. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-40262-9.

- Lewis, Mark Edward (30 April 2011). China Between Empires: The Northern and Southern Dynasties. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-06035-7.

- ^ Smith, Richard Joseph (1994). China's cultural heritage: the Qing dynasty, 1644–1912 (2 ed.). Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-1347-4.

- Hanson, Marta E. (July 2007). "Jesuits and Medicine in the Kangxi Court (1662–1722)" (PDF). Pacific Rim Report (43). San Francisco: Center for the Pacific Rim, University of San Francisco: 7, 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- Young, Lung-Chang (Summer 1988). "Regional Stereotypes in China". Chinese Studies in History. 21 (4): 32–57. doi:10.2753/csh0009-4633210432. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013.

- Source: United States Central Intelligence Agency, 1990.

- ^ "Regions of Chinese food-styles/flavors of cooking". regional cuisines. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009.

- Zhu, Hua (1 March 2017). "The Tropical Forests of Southern China and Conservation of Biodiversity". The Botanical Review. 83 (1): 87–105. Bibcode:2017BotRv..83...87Z. doi:10.1007/s12229-017-9177-2. ISSN 1874-9372. S2CID 29536766.

- ^ Eberhard, Wolfram (December 1965). "Chinese Regional Stereotypes". Asian Survey. 5 (12). University of California Press: 596–608. doi:10.2307/2642652. JSTOR 2642652.

- "Jones Lamprey | Historical Photographs of China". hpcbristol.net. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ Lamprey, J. (1868). "A Contribution to the Ethnology of the Chinese". Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London. 6: 101–108. doi:10.2307/3014248. ISSN 1368-0366. JSTOR 3014248.

- Lu, Guoguang; Yang, Zhihui; Zhang, Yan; Lu, Shengxu; Gong, Siyuan; Li, Tingting; Shen, Yijie; Zhang, Sihan; Zhuang, Hanya (2022). "Geographic latitude and human height - Statistical analysis and case studies from China". Arabian Journal of Geosciences. 15 (335). Bibcode:2022ArJG...15..335L. doi:10.1007/s12517-021-09335-x.

- Talhelm, Thomas; Dong, Xiawei (27 February 2024). "People quasi-randomly assigned to farm rice are more collectivistic than people assigned to farm wheat". Nature Communications. 15 (1): 1782. Bibcode:2024NatCo..15.1782T. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-44770-w. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 10899190. PMID 38413584.

- ^ Talhelm, T.; Zhang, X.; Oishi, S.; Shimin, C.; Duan, D.; Lan, X.; Kitayama, S. (9 May 2014). "Large-Scale Psychological Differences Within China Explained by Rice Versus Wheat Agriculture". Science. 344 (6184): 603–608. Bibcode:2014Sci...344..603T. doi:10.1126/science.1246850. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 24812395.

- Talhelm, Thomas; Zhang, Xuemin; Oishi, Shigehiro (6 April 2018). "Moving chairs in Starbucks: Observational studies find rice-wheat cultural differences in daily life in China". Science Advances. 4 (4): eaap8469. Bibcode:2018SciA....4.8469T. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aap8469. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 5916507. PMID 29707634.

- Talhelm, Thomas; Oishi, Shigehiro (2018). "How Rice Farming Shaped Culture in Southern China". In Uskul, Ayse (ed.). Socio-Economic Environment and Human Psychology: Social, Ecological, and Cultural Perspectives. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 53–76. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190492908.003.0003. ISBN 9780190492908. LCCN 2017046499. SSRN 3199657.

- Bray, Francesca (1994). The Rice Economies: Technology and Development in Asian Societies. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08620-3.

- Mengqi Wang; Yi Huangyi (18 September 2020). "Why Residents in Southern China Live Longer Than Those in Northern China?" (PDF). Semantic Scholar. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

Table 1, Page number 2

- Daisheng Tang; Tao Bu (2020). "Differences in Overweight and Obesity between the North and South of China". Research gate. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

Page number 789, Paragraph 2

Further reading

- Brues, Alice Mossie (1977). People and Races. Macmillan series in physical anthropology. New York, NY: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-315670-0.

- Du, Ruofu; Yuan, Yida; Hwang, Juliana; Mountain, Joanna; Cavalli-Sforza, L. Luca (1992). "Chinese Surnames and the Genetic Differences between North and South China". Journal of Chinese Linguistics Monograph Series (5): 1–93. ISSN 2409-2878. JSTOR 23825835.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Liu, Kwang-chang. (1999). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge University Press.

- Morgan, Stephen L. (2000). "Richer and Taller: Stature and Living Standards in China, 1979-1995". The China Journal (44): 1–39. doi:10.2307/2667475. ISSN 1324-9347. JSTOR 2667475. PMID 18411497.

- Muensterberger, Warner (1951). "Orality and Dependence: Characteristics of Southern Chinese." In Psychoanalysis and the Social Sciences, (3), ed. Geza Roheim (New York: International Universities Press).