| Revision as of 19:39, 27 September 2013 editIhardlythinkso (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers75,238 editsm px → upright=← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 03:27, 31 December 2024 edit undoMikeycdiamond (talk | contribs)100 edits →History: added timelineTag: Visual edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Genre of seated tabletop social play}} | |||

| ]'' is licensed in 103 countries and printed in 37 languages.]] | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2021}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ]'' is licensed in 103 countries and printed in 37 languages.<ref>{{cite news |author=<!--not stated--> |date=February 20, 2008 |title=You can choose cities for new Monopoly game |url=https://www.nbcnews.com/news/amp/wbna23238096 |work=] |location= |access-date=September 16, 2023}}</ref>]] | |||

| ] library in Finland, 2016]] | |||

| '''Board games''' are ]s that typically use {{boardgloss|pieces}}. These pieces are moved or placed on a pre-marked ] (playing surface) and often include elements of ], ], ], and ]s as well. | |||

| A '''board game''' is a ] that involves ] moved or placed on a pre-marked surface or ], according to a set of rules. Games can be based on pure ], chance (e.g. rolling ]), or a mixture of the two, and usually have a goal that a player aims to achieve. Early board games represented a battle between two armies, and most current board games are still based on defeating opposing players in terms of counters, winning position, or accrual of points (often expressed as in-game currency). | |||

| Many board games feature a competition between two or more players. To give a few examples: in ] (British English name 'draughts'), a player wins by capturing all opposing pieces, while ]s often end with a calculation of final scores. '']'' is a ] where players all win or lose as a team, and ] is a ] for one person. | |||

| There are many different types and styles of board games. Their representation of real-life situations can range from having no inherent theme, as with ], to having a specific theme and narrative, as with '']''. Rules can range from the very simple, as in ], to those describing a game universe in great detail, as in '']'' (although most of the latter are ]s where the board is secondary to the game, serving to help visualize the game ]). | |||

| There are many varieties of board games. Their representation of real-life situations can range from having no inherent theme, such as ], to having a specific theme and narrative, such as '']''. Rules can range from the very simple, such as in ]; to deeply complex, as in '']''. Play components now often include custom figures or shaped counters, and distinctively shaped player pieces commonly known as ] as well as traditional cards and dice. | |||

| The amount of time required to learn to play or master a game varies greatly from game to game. Learning time does not necessarily correlate with the number or complexity of rules; some games, such as ] or ], have simple rulesets while possessing profound strategies. | |||

| The time required to learn or master {{boardgloss|gameplay}} varies greatly from game to game, but is not necessarily related to the number or complexity of rules; for example, ] or ] possess relatively simple {{boardgloss|rulesets}} but have great strategic depth.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Pritchard |first=D.B. |title=The Encyclopedia of Chess Variants |publisher=Games & Puzzles Publications |year=1994 |isbn=978-0-9524142-0-9 |page=84 |quote=Chess itself is a simple game to learn but its resulting strategy is profound. |author-link=David Pritchard (chess player)}}</ref> | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| {{Further|History of games}} | |||

| ], ] (c. 744 CE)]] | |||

| ] | |||

| Board games have been played in most cultures and societies throughout history; some even pre-date literacy skill development in the earliest civilizations.{{Citation needed|date=September 2008}} A number of important historical sites, artifacts, and documents shed light on early board games. These include: | |||

| ===Ancient=== | |||

| * ] gameboards | |||

| Classical board games are divided into four categories: race games (such as ]), space games (such as ]), chase games (such as ]), and games of displacement (such as ]).<ref>{{Cite book |last=Woods |first=Stewart |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xgmjCHxSxvoC&q=history+of+board+games&pg=PP1 |title=Eurogames: The Design, Culture and Play of Modern European Board Games |date=16 August 2012 |isbn=9780786490653 |page=17|publisher=McFarland }}</ref> | |||

| * ] has been found in ] and ] burials of Egypt, c. 3500 BC and 3100 BC respectively.<ref name="senet1">{{cite journal|url=http://www.gamesmuseum.uwaterloo.ca/Archives/Piccione/index.html |title=In Search of the Meaning of Senet |first=Peter A. |last=Piccione |journal=Archaeology |year=1980 |month=July/August |pages=55–58 |accessdate=2008-06-23}}</ref> Senet is the oldest board game known to have existed, and was pictured in a ] found in Merknera's tomb (]–]).<ref name="senet2">{{cite web|url=http://www.hrejsi.cz/clanky/dama1.html |title=''Okno do svita deskovych her'' |publisher=Hrejsi.cz |date=1998-04-27 |accessdate=2010-02-12}}</ref> | |||

| * ], another ancient board game from Predynastic Egypt | |||

| * ], an ancient strategy board game originating in China | |||

| * ], a board game originating in Mesoamerica played by the ancient Aztec | |||

| * ], the Royal Tombs of Ur contain this game, among others | |||

| * ], the earliest known list of games | |||

| * ] and ], ancient board games of India | |||

| Board games have been played, traveled, and evolved<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Livingstone |first1=Ian |title=Board games in 100 moves |last2=Wallis |first2=James |publisher=Dorling Kindersley |year=2019 |isbn=978-0-241-36378-2 |location=London |oclc=1078419452}}</ref> in most cultures and societies throughout history. Several important historical sites, artifacts, and documents shed light on early board games such as ] ]s<ref>{{Cite book |last=Maǧīdzāda |first=Yūsuf |url=http://worldcat.org/oclc/249152908 |title=Jiroft: the earliest oriental civilization |date=2003 |publisher=Organization of the Ministry of Culture ans Islamic Guidance |isbn=964-422-478-7 |oclc=249152908}}</ref>{{Verification needed|date=May 2024}} in Iran. ], found in ] and ] burials of Egypt, {{Circa|3500 BC}} and 3100 BC respectively,<ref name="senet1">{{Cite journal |last=Piccione |first=Peter A. |date=July–August 1980 |title=In Search of the Meaning of Senet |url=http://www.piccionep.people.cofc.edu/piccione_senet.pdf |url-status=live |journal=Archaeology |pages=55–58 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111125005541/http://piccionep.people.cofc.edu/piccione_senet.pdf |archive-date=2011-11-25 |access-date=14 July 2018}}</ref> is the oldest board game known to have existed.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Solly |first=Meilan |title=The Best Board Games of the Ancient World |url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/best-board-games-ancient-world-180974094/ |access-date=2021-11-27 |website=Smithsonian Magazine |language=en}}</ref> Senet was pictured in a ] painting found in Merknera's tomb (3300–2700 BC).<ref name="senet2">{{Cite web |date=27 April 1998 |title=Okno do svita deskovych her |url=http://www.hrejsi.cz/clanky/dama1.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://archive.today/20121208220158/http://www.hrejsi.cz/clanky/dama1.html |archive-date=8 December 2012 |access-date=12 February 2010 |publisher=Hrejsi.cz}}</ref><ref name="Pivotto">{{Cite web |last=Pivotto |first=Carlos |display-authors=etal |title=Detection of Negotiation Profile and Guidance to more Collaborative Approaches through Negotiation Games |url=http://worldcomp-proceedings.com/proc/p2011/EEE3388.pdf |url-status=live |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://worldcomp-proceedings.com/proc/p2011/EEE3388.pdf |archive-date=2022-10-09 |access-date=2 October 2014}}</ref>{{better source needed|date=February 2023}}{{dubious|date=February 2023}} Also from predynastic Egypt is ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Games in ancient Egypt |url=https://www.ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt//furniture/games.html |access-date=13 June 2020 |website=Digital Egypt for Universities |publisher=University College, London}}</ref> | |||

| ===Timeline=== | |||

| {{see also|Category:Years in games|Timeline of chess}} | |||

| * c. 3500 BC: ] is played in Predynastic Egypt as evidenced by its inclusion in burial sites;<ref name="senet1"/> also depicted in the tomb of Merknera. | |||

| * c. 3000 BC: The ] board game from Predynastic Egypt, played with ]-shaped game pieces and ]. | |||

| * c. 3000 BC: Ancient ] set, found in the ] in ].<ref name="Payvand">{{cite news|url=http://www.payvand.com/news/04/dec/1029.html |title=World's Oldest Backgammon Discovered In Burnt City |work=Payvand News |date=December 4, 2004 |accessdate=2010-05-07}}</ref><ref name="Iranica board game ">{{cite encyclopedia |last= Schädler , Dunn-Vaturi |first= Ulrich , Anne-Elizabeth | title= BOARD GAMES in pre-Islamic Persia | encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Iranica | accessdate=2010-05-07|url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/board-games-in-pre-islamic-persia}}</ref> | |||

| * c. 2560 BC: Board of the ] (found at Ur Tombs) | |||

| * c. 2500 BC: Paintings of ] and Han being played depicted in the tomb of Rashepes{{Citation needed|date=September 2008}} | |||

| * c. 1500 BC: Painting of board game at ].<ref>{{cite journal|url=http://www.gamesmuseum.uwaterloo.ca/Archives/Brumbaugh/index.html |title=The Knossos Game Board |first= Robert S. |last=Brumbaugh |accessdate=2008-06-23 |journal=American Journal of Archaeology |year=1975 |pages=135–137 |doi=10.2307/503893 |volume=79|issue=2|jstor=503893|publisher=Archaeological Institute of America}}</ref> | |||

| * c. 500 BC: The ] mentions board games played on 8 or 10 rows. | |||

| * c. 500 BC: The earliest reference to ] in the ], the ] epic. | |||

| * c. 400 BC: Two ornately decorated ] gameboards from a royal tomb of the ] in ].<ref>{{cite book | last = Rawson | first = Jessica | authorlink = Jessica Rawson | title = Mysteries of Ancient China | publisher = British Museum Press | year = 1996 | location = London | pages = 159–161 | isbn = 0-7141-1472-3}}</ref> | |||

| * c. 400 BC: The earliest written reference to ] (''weiqi'') in the historical annal '']''. Go is also mentioned in the Analects of Confucius (c. 5th century BC).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://senseis.xmp.net/?Confucius |title=Confucius |publisher=Senseis.xmp.net |date=2006-09-23 |accessdate=2010-02-12}}</ref> | |||

| * 116–27 BC: ]'s ''Lingua Latina X'' ('''II, par. 20''') contains earliest known reference to ]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/varro.ll10.html |title=Varro: Lingua Latina X |publisher=Thelatinlibrary.com |date= |accessdate=2010-02-12}}</ref> (often confused with '']'', ]'s game mentioned below). | |||

| * 1 BC – 8 AD: ]'s '']'' contains earliest known reference to ]. | |||

| * 1 BC – 8 AD: The Roman ] is a game of which little is known, and is more or less contemporary with the Latrunculi. | |||

| * c. 43 AD: The ] is buried with the ].<ref>''Games Britannia – 1. Dicing with Destiny'', ], 1:05am Tuesday 8th December 2009</ref> | |||

| * c. 200 AD: A stone ] board with a 17×17 grid from a tomb at ] in ], ].<ref>John Fairbairn's {{dead link|date=December 2010}}</ref> | |||

| * 220–265: ] enters ] under the name ''t'shu-p'u'' (Source: ''Hun Tsun Sii''){{Citation needed|date=September 2008|reason=Source cannot be identified and checked from that name alone.}} | |||

| * c. 400 onwards: ] played in Northern Europe.<ref>], pp.56, 57.</ref> | |||

| * c. 600: The earliest references to ] written in Subandhu's ''Vasavadatta'' and ]'s '']'' early Indian books.{{Citation needed|reason=date: September 15, 2008|date=September 2008}} | |||

| * c. 600: The earliest reference to ] written in ''Karnamak-i-Artakhshatr-i-Papakan''.{{Citation needed|date=September 2008}} | |||

| * c. 700: Date of the oldest evidence of ] games, found in ] and ]. | |||

| * c. 1283: ] in Spain commissioned ''Libro de ajedrez, dados, y tablas'' ('']'') translated into Castilian from Arabic and added illustrations with the goal of perfecting the work.<ref name="Burns">Burns, Robert I. "Stupor Mundi: Alfonso X of Castile, the Learned." Emperor of Culture: Alfonso X the Learned of Castile and His Thirteenth-Century Renaissance. Ed. Robert I. Burns. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania P, 1990. 1–13.</ref><ref name="SMG">Sonja Musser Golladay, (PhD diss., University of Arizona, 2007), 31. Although Golladay is not the first to assert that 1283 is the finish date of the ''Libro de Juegos'', the ''a quo'' information compiled in her dissertation consolidates the range of research concerning the initiation and completion dates of the ''Libro de Juegos''.</ref> | |||

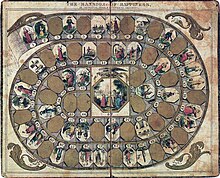

| * 1759: ''A Journey Through Europe'' published by ], the earliest board game with a designer whose name is known. | |||

| * 1874: '']'' is trademarked by ]. | |||

| * c. 1930: '']'' stabilises into the version that is currently popular. | |||

| * 1938: The first version of '']'' published by ] under the name "Criss-Crosswords". | |||

| * 1957: '']'' is released. | |||

| * 1970: The code-breaking board game '']'' is designed by ]. | |||

| * c. 1980: ]s begin to develop as a genre. | |||

| ], another ancient Egyptian board game, appeared around 2000 BC.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Hirst |first=K. Kris |title=What? Snakes and Ladders is 4,000 Years Old? |url=https://www.thoughtco.com/50-holes-game-169581 |access-date=23 December 2018 |website=ThoughtCo.com}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=18 November 2018 |title=A 4,000-Year-Old Bronze Age Game Called 58 Holes Has Been Discovered in Azerbaijan Rock Shelter |url=http://wsbuzz.com/science/a-4000-year-old-bronze-age-game-called-58-holes-has-been-discovered-in-azerbaijan-rock-shelter/ |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190826203339/https://wsbuzz.com/science/a-4000-year-old-bronze-age-game-called-58-holes-has-been-discovered-in-azerbaijan-rock-shelter/ |archive-date=26 August 2019 |access-date=23 December 2018 |website=WSBuzz.com |language=en-US}}</ref> The first complete set of this game was discovered from a ] that dates to the ].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Metcalfe |first=Tom |date=10 December 2018 |title=16 of the Most Interesting Ancient Board and Dice Games |url=https://www.livescience.com/64266-ancient-board-games.html |access-date=23 December 2018 |website=Live Science}}</ref> This game was also popular in ] and the ].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Bower |first=Bruce |date=17 December 2018 |title=A Bronze Age game called 58 holes was found chiseled into stone in Azerbaijan |url=https://www.sciencenews.org/article/bronze-age-game-found-chiseled-stone-azerbaijan |access-date=23 December 2018 |website=Science News |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Many board games are now available as ]s, which can include the computer itself as one of several players, or as a sole opponent. The rise of computer use is one of the reasons said to have led to a relative decline in board games.{{Citation needed|date=September 2008}} Many board games can now be played ] against a computer and/or other players. Some ]s allow play in ] and immediately show the opponents' moves, while others use ] to notify the players after each move (see the links at the end of this article).{{Citation needed|date=September 2008}} Modern technology (the ] and cheaper home ]) has also influenced board games via the phenomenon of print-and-play board games that you buy and print yourself. | |||

| ] originated in ancient Mesopotamia about 5,000 years ago.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Backgammon History |url=https://bkgm.com/articles/Bray/BackgammonHistory/ |access-date=17 February 2021 |website=bkgm.com}}</ref> ], ], ] and ] originated in India. ] (4th century BC) and ] (1st century BC) originated in China. The board game ] originated in ] and was played by a wide range of ] cultures such as the ]s and the ]. The ] was found in the royal tombs of Ur, dating to Mesopotamia 4,600 years ago.<ref name="fv">{{Cite web |last=Edwards |first=Jason R. |title=Saving Families, One Game at a Time |url=http://visionandvalues.org/docs/familymatters/Edwards_Jason.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160205071220/http://visionandvalues.org/docs/familymatters/Edwards_Jason.pdf |archive-date=5 February 2016}}</ref> | |||

| Some board games make use of components in addition to—or instead of—a board and playing pieces. Some games use ]s, ]s, and, more recently, ]s in accompaniment to the game.{{Citation needed|date=September 2008}} | |||

| <gallery mode="packed" heights="160"> | |||

| Around the year 2000 the board gaming industry began to grow with companies such as Fantasy Flight Games, Z-Man Games, or Indie Boards and Cards, churning out new games which are being sold to a growing (and slightly massive) audience worldwide.<ref name="board game resurgence">{{cite web|url=http://www.shutupshow.com/post/34426556753/su-sd-present-the-board-game-golden-age |title=The Board Game Golden Age |first=Quinti |last=Smith |year=2012 |month=October |accessdate=2013-05-10}}</ref> | |||

| File:Maler der Grabkammer der Nefertari 003.jpg|], one of the oldest known board games | |||

| File:Game of Hounds and Jackals MET DP264105.jpg|] (]) | |||

| File:Men Playing Board Games.jpg|'' Men Playing Board Games'', from The Sougandhika Parinaya Manuscript | |||

| File:British Museum Royal Game of Ur.jpg|], southern Iraq, about 2600–2400 BCE | |||

| File:Macuilxochitl Patolli.png|Patolli game being watched by ] as depicted on page 048 of the ] | |||

| File:Han Pottery Figures Playing Liubo, a Lost Game (10352729936).jpg|] glazed pottery tomb figurines playing liubo, with six sticks laid out to the side of the game board | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| === |

===Europe=== | ||

| {{further|Eurogame#History}} | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| Board games have a long tradition in Europe. The oldest records of board gaming in Europe date back to ]'s '']'' (written in the 8th century BC), in which he mentions the Ancient Greek game of '']''.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web |last=Brouwers |first=Josho |title=Ancient Greek heroes at play |url=https://www.ancientworldmagazine.com/articles/ancient-greek-heroes-play/ |access-date=6 March 2020 |website=Ancient World Magazine |date=29 November 2018 |language=en}}</ref> This game of ''petteia'' would later evolve into the Roman '']''.<ref name=":0" /> Board gaming in ancient Europe was not unique to the Greco-Roman world, with records estimating that the ancient Norse game of '']'' was developed sometime before 400 ].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Schulte |first=Michael |title=Board games of the Vikings – From hnefatafl to chess |url=http://ojs.novus.no/index.php/MOM/article/download/1426/1411 |page=5}}</ref> In ancient Ireland, the game of '']'' or '']'', is said to date back to at least 144 AD,<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Harding |first=Timothy |date=2010 |title='A Fenian pastime'? Early Irish board games and their identification with chess |journal=Irish Historical Studies |volume=37 |issue=145 |page=5 |doi=10.1017/S0021121400000031 |issn=0021-1214 |jstor=20750042 |hdl-access=free |hdl=2262/38847 |s2cid=163144950}}</ref> though this is likely an anachronism. A fidchell board dating from the 10th century has been uncovered in Co. Westmeath, Ireland.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Jackson |first=Kenneth Hurlstone |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pkTUotRW8_AC&q=the+oldest+irish+tradition |title=The Oldest Irish Tradition: A Window on the Iron Age |date=28 February 2011 |isbn=9780521134934 |page=23|publisher=Cambridge University Press }}</ref> | |||

| |align = center | |||

| |image1 = Maler der Grabkammer der Nefertari 003.jpg | |||

| |width1 = 160 | |||

| |caption1 = ] is among the oldest known board games. | |||

| |image2 = Alfonso LJ 97V.jpg | |||

| |width2 = 160 | |||

| |caption2 = The game of astronomical tables, from ''Libro de los juegos'' | |||

| |image3 = AMI - Schachbrett.jpg | |||

| |width3 = 160 | |||

| |caption3 = Board game with inlays of ivory, rock crystal and glass paste, covered with gold and silver leaf, on a wooden base (], ] 1600–1500 BC, ] Archaeological Museum, Crete) | |||

| |image4 = VA23Oct10 171.jpg | |||

| |width4 = 160 | |||

| |caption4 = French ] tray and board game, 1720–50 | |||

| |image5 = Krieger beim Brettspiel 2.jpg | |||

| |width5 = 160 | |||

| |caption5 = ] ]s playing a board game, c. 520 BC, ] | |||

| |image6 = Jiroft scorpion.png | |||

| |width6 = 160 | |||

| |caption6 = Another gameboard found in the ] | |||

| }} | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| In the United Kingdom, association of dice and cards with gambling led to all dice games except backgammon being treated as lotteries by dice in the Gaming Acts of ] and ].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Neilson |first=W Bryce |title=GAMING HISTORY & LAW |url=https://www.gamesboard.org.uk/articles/gaming-law-bryce-neilson-aug-2020.pdf |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201001082026/https://www.gamesboard.org.uk/articles/gaming-law-bryce-neilson-aug-2020.pdf |archive-date=2020-10-01 |access-date=15 February 2022 |website=Gamesboard.org}}</ref> Early board game producers in the second half of the eighteenth century were mapmakers. The global popularization of board games, with special themes and branding, coincided with the formation of the global dominance of the ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Kentel |first=Koca |date=Fall 2018 |title=Empire on a Board: Navigating the British Empire through Geographical Board Games in the Nineteenth Century |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/M6JW86M71 |journal=The Portolan |volume=102 |pages=27–42 |doi=10.17613/M6JW86M71}}</ref> ] was an English board game publisher, bookseller, map/chart seller, printseller, music seller, and ]. With his sons John Wallis Jr. and Edward Wallis, he was one of the most prolific publishers of board games of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Adam |first=Gottfried |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Lb6ZEAAAQBAJ&dq=John+Wallis++publishers+of+board+games&pg=PA177 |title=Thumb Bibles: The History of a Literary Genre |date=2022-10-31 |publisher=BRILL |isbn=978-90-04-52588-7 |language=en}}</ref> John Betts' ''A Tour of the British Colonies and Foreign Possessions''<ref>{{Cite web |title=ATour Through the British Colonies and Foreign Possessions | Betts, John | V&A Explore The Collections |url=https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O2/O26/O262/O2628/O26285/ |website=Victoria and Albert Museum: Explore the Collections}}</ref> and William Spooner's ''A Voyage of Discovery''<ref>{{Cite web |title=A Voyage of Discovery or The Five Navigators | Spooner, William | V&A Explore The Collections |url=https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O2/O26/O263/O2635/O26352/ |website=Victoria and Albert Museum: Explore the Collections}}</ref> were popular in the British empire. {{lang|de|]}} is a genre of wargaming developed in 19th century ] to teach battle tactics to officers.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Asbury |first=Susan |date=Winter 2018 |title=It's All a Game: The History of Board Games from Monopoly to Settlers of Catan |url=https://www.journalofplay.org/sites/www.journalofplay.org/files/pdf-articles/10-2-Book-review2.pdf |url-status=dead |department=Book Reviews |journal=American Journal of Play |volume=10 |issue=2 |page=230 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200711112435/https://www.journalofplay.org/sites/www.journalofplay.org/files/pdf-articles/10-2-Book-review2.pdf |archive-date=11 July 2020 |access-date=5 March 2020}}</ref> | |||

| ==In America== | |||

| <gallery mode="packed" heights="160"> | |||

| ===Colonial America=== | |||

| File:Attic Black-Figure Neck Amphora - Achilles and Ajax playing a board game overseen by Athena.jpg|Achilles and Ajax playing a board game overseen by Athena, Attic black-figure neck amphora, {{circa|510 BCE}} | |||

| In seventeenth and eighteenth century colonial America, the agrarian life of the country left little time for game playing though ] (]), ], and card games were not unknown. The Pilgrims and Puritans of New England frowned on game playing and viewed dice as instruments of the devil. When the Governor William Bradford discovered a group of non-Puritans playing stool-ball, pitching the bar, and pursuing other sports in the streets on Christmas Day, 1622, he confiscated their implements, reprimanded them, and told them their devotion for the day should be confined to their homes. | |||

| File:German - Box for Board Games - Walters 7193 - Bottom.jpg|''Box for Board Games'', {{Circa}} 15th century, Walters Art Museum | |||

| File:Gaming table with chessboard.jpg|An early ] (Germany, 1735) featuring ]/] ({{em|left}}) and ] ({{em|right}}) | |||

| File:'Game of Skittles', copy of painting by Pieter de Hooch, Cincinnati Art Museum.JPG|'Game of Skittles', copy of 1660–68 painting by Pieter de Hooch in the Saint Louis Art Museum | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| === |

===The Americas=== | ||

| ] | |||

| ]'' (1886) was one of the first board games based on materialism and capitalism published in the United States.]] | |||

| The board game '']'' and its sister game ''Traveller's Tour Through Europe'' were published by New York City bookseller F. & R. Lockwood in 1822 and claim the distinction of being the first board games published in the United States.<ref name=fv/> | |||

| In ''Thoughts on Lotteries'' (1826) Thomas Jefferson wrote, "Almost all these pursuits of chance produce something useful to society. But there are some which produce nothing, and endanger the well-being of the individuals engaged in them or of others depending on them. Such are games with cards, dice, billiards, etc. And although the pursuit of them is a matter of natural right, yet society, perceiving the irresistible bent of some of its members to pursue them, and the ruin produced by them to the families depending on these individuals, consider it as a case of insanity, quoad hoc, step in to protect the family and the party himself, as in other cases of insanity, infancy, imbecility, etc., and suppress the pursuit altogether, and the natural right of following it. There are some other games of chance, useful on certain occasions, and injurious only when carried beyond their useful bounds. Such are insurances, lotteries, raffles, etc. These they do not suppress, but take their regulation under their own discretion." | |||

| The board game, ''Traveller's Tour Through the United States'' was published by New York City bookseller F. Lockwood in 1822 and today claims the distinction of being the first board game published in the United States. | |||

| Margaret Hofer described the period of the 1880s–1920s as "The Golden Age" of board gaming in America.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hofer |first=Margaret |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=icYtGRUZrZUC |title=The Games we Played: The Golden Age of Board and Table Games |date=2003-03-01 |publisher=Princeton Architectural Press |isbn=978-1-56898-397-4 |language=en}}</ref> Board game popularity was boosted, like that of many items, through ], which made them cheaper and more easily available. | |||

| As the United States shifted from ] to ] living in the nineteenth century, greater leisure time and a rise in income became available to the middles class. The American home, once the center of economic production, became the ] of entertainment, enlightenment, and education under the supervision of mothers. Children were encouraged to play board games that developed literacy skills and provided moral instruction.<ref name="Jensen">{{cite web |url=http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1026/is_6_160/ai_80864307/pg_1?tag=content;col1 |last=Jensen |first=Jennifer |title=Teaching Success Through Play: American Board and Table Games, 1840-1900 |work=Magazine Antiques |publisher=bnet |year=2003 |accessdate=2009-02-07}}</ref> | |||

| ===Asia and Africa=== | |||

| The earliest board games published in the United States were based upon Christian morality. '']'' (1843), for example, sent players along a path of virtues and vices that led to the Mansion of Happiness (Heaven).<ref name="Jensen" /> ''The Game of Pope or Pagan, or The Siege of the Stronghold of Satan by the Christian Army'' (1844) pitted an image on its board of a ] woman committing '']'' against missionaries landing on a foreign shore. The missionaries are cast in white as "the symbol of innocence, temperance, and hope" while the pope and pagan are cast in black, the color of "gloom of error, and...grief at the daily loss of empire".<ref>{{cite book |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=2pitMiJJLX8C&pg=PA261&dq=Fessenden+Culture+and+Religion+Pope+and+Pagan&ie=ISO-8859-1&output=html |last=Fessenden |first=Tracy |title=Culture and Redemption: Religion, the Secular, and American Literature |publisher=Princeton University Press |year=2007 |pages=271 |accessdate=2009-02-07}}</ref> | |||

| Different traditional board games are popular in Asian and African countries. In China, ] and many variations of chess are popular. In Africa and the Middle East, ] is a popular board game archetype with many regional variations. In India, a community game called ] is popular.<ref>{{Cite web |date=12 September 2020 |title=The most popular board games in non-Western cultures |url=https://boardgametheories.com/most-popular-board-games-in-other-cultures/ |access-date=1 October 2020 |website=BoardGameTheories}}</ref> A popular board game of flicking stones (]) is popular in ].{{Citation needed|date=September 2024}} | |||

| ===Modern=== | |||

| Commercially-produced board games in the middle nineteenth century were monochrome prints laboriously hand-colored by teams of low paid young factory women. Advances in paper making and printmaking during the period enabled the commercial production of relatively inexpensive board games. The most significant advance was the development of ], a technological achievement that made bold, richly colored images available at affordable prices. Games cost as little as US$.25 for a small boxed card game to $3.00 for more elaborate games. | |||

| ]. Expansion sets for existing games are marked in orange.]] | |||

| In the late 1990s, companies began producing more new games to serve a growing worldwide market.<ref name="board game resurgence">{{Cite web |last=Smith |first=Quintin |date=October 2012 |title=The Board Game Golden Age |url=http://www.shutupshow.com/post/34426556753/su-sd-present-the-board-game-golden-age |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130601124655/http://www.shutupshow.com/post/34426556753/su-sd-present-the-board-game-golden-age |archive-date=1 June 2013 |access-date=10 May 2013}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=A look into the golden age of boardgames {{!}} BGG |url=https://boardgamegeek.com/thread/1943195/look-golden-age-boardgames |access-date=1 March 2020 |website=BoardGameGeek |language=en-US}}</ref> In the 2010s, several publications said board games were amid a new Golden Age or "renaissance".<ref name="board game resurgence" /><ref name=guardian2014oct/><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Konieczny |first=Piotr |date=2019 |title=Golden Age of Tabletop Gaming: Creation of the Social Capital and Rise of Third Spaces for Tabletop Gaming in the 21st Century |url=http://bazekon.icm.edu.pl/bazekon/element/bwmeta1.element.ekon-element-000171561541 |journal=Polish Sociological Review |language=EN |issue=2 |pages=199–215 |doi=10.26412/psr206.05 |doi-broken-date=1 November 2024 |issn=1231-1413}}</ref> Board game venues also grew in popularity; in 2016 alone, more than 5,000 ]s opened in the U.S.,<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Board Game Biz is Booming, and Chicago's Ready to Play |url=https://news.wttw.com/2020/02/11/board-game-biz-booming-and-chicago-s-ready-play |access-date=1 March 2020 |website=WTTW News |language=en}}</ref> and they were reported to be very popular in China as well.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Six Reasons China Loves Board Game Cafés |url=http://flamingogroup.com/six-reasons-china-loves-board-game-cafes# |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160520043014/http://flamingogroup.com/six-reasons-china-loves-board-game-cafes |archive-date=20 May 2016 |access-date=22 April 2016 |website=Flamingo}}</ref> | |||

| Board games have been used as a mechanism for ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Coon |first1=Jo Thompson |last2=Orr |first2=Noreen |last3=Shaw |first3=Liz |last4=Hunt |first4=Harriet |last5=Garside |first5=Ruth |last6=Nunns |first6=Michael |last7=Gröppel-Wegener |first7=Alke |last8=Whear |first8=Becky |date=2022-04-04 |title=Bursting out of our bubble: using creative techniques to communicate within the systematic review process and beyond |journal=Systematic Reviews |volume=11 |issue=1 |pages=56 |doi=10.1186/s13643-022-01935-2 |issn=2046-4053 |pmc=8977563 |pmid=35379331 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| American Protestants believed a virtuous life led to success, but the belief was challenged mid-century when Americans embraced materialism and capitalism. The accumulation of material goods was viewed as a divine blessing. In 1860, '']'' rewarded players for mundane activities such as attending college, marrying, and getting rich. Daily life rather than eternal life became the focus of board games.The game was the first to focus on secular virtues rather than religious virtues,<ref name="Jensen" /> and sold 40,000 copies its first year.<ref name="Hofer">{{cite book |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=icYtGRUZrZUC&pg=PP1&dq=Margaret+Hofer+The+Games+We+Played&lr=&num=50&as_brr=3&as_pt=BOOKS&ie=ISO-8859-1&output=html |last=Hofer |first=Margaret K. |title=The Games We Played: The Golden Age of Board & Table Games |publisher=Princeton Architectural Press |year=2003 |accessdate=2009-02-07}}</ref> | |||

| ==Luck, strategy, and diplomacy== | |||

| ''Game of the District Messenger Boy, or Merit Rewarded'' is a board game published in 1886 by the New York City firm of ]. The game is a typical roll-and-move track board game. Players move their tokens along the track at the spin of the arrow toward the goal at track's end. Some spaces on the track will advance the player while others will send him back. | |||

| Some games, such as chess, depend completely on player skill, while many children's games such as '']'' and '']'' require no decisions by the players and are decided purely by luck.<ref>{{Cite web |date=26 January 2009 |title=The case against Candy Land |url=http://boingboing.net/2009/01/26/the-case-against-can.html |website=BoingBoing}}</ref> | |||

| ]'']] | |||

| In the affluent 1880s, Americans witnessed the publication of ] ] games that permitted players to emulate the capitalist heroes of the age. One of the first such games, ''The Game of the District Messenger Boy'', encouraged the idea that the lowliest messenger boy could ascend the corporate ladder to its topmost rung. Such games insinuated that the accumulation of wealth brought increased social status.<ref name="Jensen" /> Competitive capitalistic games culminated in 1935 with ''Monopoly,'' the most commercially successful board game in United States history.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://boardgames.lovetoknow.com/History_of_the_Game_Monopoly |author=Weber, Susan, and Susie McGee |title=History of the Game Monopoly |date=n.d. |accessdate=2009-02-03| archiveurl= http://web.archive.org/web/20090210050138/http://boardgames.lovetoknow.com/History_of_the_Game_Monopoly| archivedate= 10 February 2009 <!--DASHBot-->| deadurl= no}}</ref> | |||

| Many games require some level of both skill and luck. A player may be hampered by bad luck in ], '']'', or '']''; but over many games, a skilled player will win more often.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Luck vs. Skill in Backgammon |url=https://bkgm.com/articles/Simborg/LuckVsSkill/index.html |access-date=19 May 2020 |website=bkgm.com}}</ref> The elements of luck can also make for more excitement at times, and allow for more diverse and multifaceted strategies, as concepts such as ] and ] must be considered.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Sfetcu |first=Nicolae |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=J1aAAwAAQBAJ&dq=%22board+game%22+%22expected+value%22+and+%22risk+management%22&pg=PA78 |title=Game Preview |date=2014-05-04 |publisher=Nicolae Sfetcu |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Luck may be introduced into a game by several methods. The use of ] of various sorts goes back to the ]. These can decide everything from how many steps a player moves their token, as in ''Monopoly'', to how their forces fare in battle, as in ''Risk'', or which resources a player gains, as in '']''. Other games such as '']'' use a deck of special ] that, when shuffled, create randomness. '']'' does something similar with randomly picked letters. Other games use spinners, timers of random length, or other sources of randomness. ]s are notable for often having fewer elements of luck than many North American board games.<ref name="How stuff works">{{Cite web |last=Kirkpatrick |first=Karen |date=27 April 2015 |title=What's a German-style board game? |url=https://entertainment.howstuffworks.com/german-style-board-game.htm |access-date=20 July 2021 |website=HowStuffWorks.com |quote="They feature little or no luck, and economic, not military, themes. In addition, all players stay in the game until it's over."}}</ref> Luck may be reduced in favour of skill by introducing symmetry between players. For example, in a dice game such as '']'', by giving each player the choice of rolling the dice or using the previous player's roll. | |||

| McLoughlin Brothers published similar games based on the telegraph boy theme including ''Game of the Telegraph Boy, or Merit Rewarded'' (1888). Greg Downey notes in his essay, "Information Networks and Urban Spaces: The Case of the Telegraph Messenger Boy" that families who could afford the deluxe version of the game in its ], wood-sided box would not "have sent their sons out for such a rough apprenticeship in the working world."<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.mercurians.org/Nov_99/info_networks.html |author=Downey, Greg |title=Information Networks and Urban Spaces: The Case of the Telegraph Messenger Boy |publisher=Mercurians |work=Antenna |date=1999-11 |accessdate=2009-02-07}} {{Dead link|date=October 2010|bot=H3llBot}}</ref> | |||

| Another important aspect of some games is diplomacy, that is, players, making deals with one another. Negotiation generally features only in games with three or more players, ] being the exception. An important facet of ''Catan'', for example, is convincing players to trade with you rather than with opponents. In ''Risk'', two or more players may team up against others. ''Easy'' diplomacy involves convincing other players that someone else is winning and should therefore be teamed up against. ''Advanced'' diplomacy (e.g., in the aptly named game '']'') consists of making elaborate plans together, with the possibility of betrayal.<ref>{{Cite news|last=McLellan|first=Joseph|date=1986-06-02|title=Lying and Cheating by the Rules|language=en-US|newspaper=Washington Post|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1986/06/02/lying-and-cheating-by-the-rules/78ab5e73-b64d-4448-875e-aae12ab43476/|access-date=2022-12-29|issn=0190-8286}}</ref> | |||

| ==Psychology== | |||

| While there has been a fair amount of scientific research on the psychology of older board games (e.g., ], ], ]), less has been done on contemporary board games such as '']'', '']'', and '']''.<ref>{{cite book | author=Gobet, Fernand | author-link=Fernand Gobet | author=de Voogt, Alex, & Retschitzki, Jean | title=Moves in mind: The psychology of board games | publisher=Psychology Press | year=2004 | isbn=1-84169-336-7}}</ref> Much research has been carried out on chess, in part because many tournament players are publicly ranked in national and international lists, which makes it possible to compare their levels of expertise. The works of ], William Chase, ], and ] have established that knowledge, more than the ability to anticipate moves, plays an essential role in chess-playing. This seems to be the case in other traditional games such as ''Go'' and ''Oware'' (a type of ''mancala'' game), but data is lacking in regard to contemporary board games.{{Citation needed|date=September 2008}} | |||

| In ] games, such as chess, each player has complete information on the state of the game, but in other games, such as '']'' or '']'', some information is hidden from players.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Glassner |first=Andrew |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Ksj1EAAAQBAJ&dq=%22board+game%22+hidden+information+estimating+probabilities+by+the+opponents+stratego&pg=PT74 |title=Interactive Storytelling: Techniques for 21st Century Fiction |date=2017-08-02 |publisher=CRC Press |isbn=978-1-040-08312-3 |language=en}}</ref> This makes finding the best move more difficult and may involve estimating probabilities by the opponents.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Levine |first=Timothy R. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iRJzAwAAQBAJ&dq=finding+the+best+move+more+difficult+and+may+involve+estimating+probabilities+by+the+opponents&pg=PA403 |title=Encyclopedia of Deception |date=2014-02-20 |publisher=SAGE Publications |isbn=978-1-4833-0689-6 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Additionally, board games can be therapeutic. ], a ] said when interviewed about his game, “With crime you deal with every basic human emotion and also have enough elements to combine action with melodrama. The player’s imagination is fired as they plan to rob the train. Because of the gamble they take in the early stage of the game there is a build up of tension, which is immediately released once the train is robbed. Release of tension is therapeutic and useful in our society, because most jobs are boring and repetitive.”<ref name=TRN1976 >Stealing the show. ''Toy Retailing News'', Volume 2 Number 4 (December 1976), p. 2</ref> | |||

| ==Software== | |||

| Linearly arranged board games have been shown to improve children's spatial numerical understanding. This is because the game is similar to a ] in that they promote a linear understanding of numbers rather than the innate logarithmic one.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.psy.cmu.edu/~siegler/sieg-ram09.pdf | title=Playing Linear Number Board Games—But Not Circular Ones—Improves Low-Income Preschoolers’ Numerical Understanding}}</ref> | |||

| {{main|Digital tabletop game}} | |||

| Many board games are now available as video games. These are aptly termed digital board games, and their distinguishing characteristic compared to traditional board games is they can now be played ] against a computer or other players. Some websites (such as boardgamearena.com, yucata.de, etc.)<ref name="onlineboard">{{Cite web |date=25 February 2019 |title=6 Best Sites to Play Board Games Online for Free |url=https://mykindofmeeple.com/play-modern-board-games-online/ |access-date=23 January 2021 |website=Mykindofmeeple.com}}</ref> allow play in ] and immediately show the opponents' moves, while others use email to notify the players after each move.<ref name="chessbyemail">{{Cite web |title=U3a International Chess by Email |url=http://www.u3abroadbeach.com/chess-by-email.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141015070203/http://www.u3abroadbeach.com/chess-by-email.html |archive-date=15 October 2014 |access-date=8 October 2014}}</ref> The Internet and cheaper home printing has also influenced board games via print-and-play games that may be purchased and printed.<ref name="printplay">{{Cite web |title=Print & Play |url=http://boardgamegeek.com/boardgamecategory/1120/print-play |access-date=8 October 2014 |website=Boardgamegeek.com}}</ref> Some games use external media such as audio cassettes or DVDs in accompaniment to the game.<ref name="dvdgames">{{Cite web |title=DVD Board Games |url=http://boardgamegeek.com/boardgamefamily/7348/dvd-board-games |access-date=8 October 2014}}</ref><ref name="cassettegames">{{Cite web |title=Audio Cassette Board Games |url=http://boardgamegeek.com/boardgamefamily/7477/audio-cassette-board-games |access-date=8 October 2014 |website=Boardgamegeek.com}}</ref> | |||

| {{anchor|Virtual tabletop}}There are also ] programs that allow online players to play a variety of existing and new board games through tools needed to manipulate the game board but do not necessarily enforce the game's rules, leaving this up to the players. There are generalized programs such as '']'', '']'' and '']'' that can be used to play any board or card game, while programs like '']'' and '']'' are more specialized for role-playing games.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Hall |first=Charlie |date=22 April 2015 |title=D&D now on Steam, complete with dice and a Dungeon Master |url=http://www.polygon.com/2015/4/22/8470473/dungeons-dragons-virtual-tabletop-fantasy-grounds |access-date=10 April 2017 |website=]}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Hall |first=Charlie |date=1 December 2016 |title=Tabletopia is slick as hell, and it's free on Steam |url=https://www.polygon.com/2016/12/1/13806190/tabletopia-steam-board-games-free-to-play |access-date=7 September 2017 |website=]}}</ref> Some of these virtual tabletops have worked with the license holders to allow for use of their game's assets within the program; for example, ''Fantasy Grounds'' has licenses for both ''Dungeons & Dragons'' and '']'' materials, while ''Tabletop Simulator'' allows game publishers to provide ] for their games.<ref>{{Cite web |title=SmiteWorks USA, LLC |url=http://www.fantasygrounds.com/press/ |access-date=21 July 2017 |website=Fantasy Grounds |publisher=SmiteWorks}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=O'Conner |first=Alice |date=1 October 2015 |title=Cosmic Encounter Officially Invades Tabletop Simulator |url=https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/2015/10/01/cosmic-encounter-tabletop-simulator/ |access-date=1 August 2016 |website=]}}</ref> However, as these games offer the ability to add in the content through ], there are also unlicensed uses of board game assets available through these programs.<ref name="gamasutra interview">{{Cite web |last=Wawro |first=Alex |date=3 July 2015 |title=Mod Mentality: How Tabletop Simulator was made to be broken |url=http://gamasutra.com/view/news/247109/Mod_Mentality_How_Tabletop_Simulator_was_made_to_be_broken.php |access-date=8 July 2015 |website=]}}</ref> | |||

| ==Luck, strategy, and diplomacy== | |||

| {{Chess diagram svg|= | |||

| | tright|check=no | |||

| | | |||

| |= | |||

| |bg|pg| | |ky|ry|ny|by|= | |||

| |ng|pg| | |py|py|py|py|= | |||

| |rg|pg| | | | | | |= | |||

| |kg|pg| | | | | | |= | |||

| | | | | | | |pd|kd|= | |||

| | | | | | | |pd|rd|= | |||

| |pr|pr|pr|pr| | |pd|nd|= | |||

| |br|nr|rr|kr| | |pd|bd|= | |||

| |]: played in ], starting position | |||

| }} | |||

| Most board games involve both luck and strategy. But an important feature of them is the amount of randomness/] involved, as opposed to skill. Some games, such as chess, depend almost entirely on player skill. But many children's games are mainly decided by luck: for example, '']'' and '']'' require no decisions by the players. A player may be hampered by a few poor rolls of the ] in ], '']'', '']'', or ], but over many games a skilled player will win more often. While some purists consider luck to be an undesirable component of a game, others counter that elements of luck can make for far more diverse and multi-faceted strategies, as concepts such as ] and ] must be considered. | |||

| ==Market== | |||

| A second aspect is the game information available to players. Some games (chess being a classic example) are '']'' games: each player has complete information on the state of the game. In other games, such as ] or '']'', some information is hidden from players. This makes finding the best move more difficult, and may involve estimating probabilities by the opponents. | |||

| ]'' is printed in 30 languages and sold 15 million by 2009.]] | |||

| While the board gaming market is estimated to be smaller than that for ], it has also experienced significant growth from the late 1990s.<ref name=guardian2014oct/> A 2012 article in '']'' described board games as "making a comeback".<ref>{{Cite news |date=9 December 2012 |title=Why board games are making a comeback |work=The Guardian |url=https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2012/dec/09/board-games-comeback-freeman |author-last=Freeman |author-first=Will}}</ref> Other expert sources suggest that board games never went away, and that board games have remained a popular leisure activity which has only grown over time.<ref>{{Cite web |date=1 August 2018 |title=Not Bored Of Board Games |url=https://www.toyindustryjournal.com/not-bored-of-board-games/ |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210302164229/https://www.toyindustryjournal.com/not-bored-of-board-games/ |archive-date=2 March 2021 |access-date=5 January 2021 |website=Toyindustryjournal.com}}</ref> Another from 2014 gave an estimate that put the growth of the board game market at "between 25% and 40% annually" since 2010, and described the current time as the "golden era for board games".<ref name="guardian2014oct">{{Cite news |date=25 November 2014 |title=Board games' golden age: sociable, brilliant and driven by the internet |work=The Guardian |url=https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/nov/25/board-games-internet-playstation-xbox |author-last=Duffy |author-first=Owen}}</ref> The rise in board game popularity has been attributed to quality improvement (more elegant ], {{boardgloss|components}}, artwork, and graphics) as well as increased availability thanks to sales through the Internet.<ref name=guardian2014oct/> ] for board games is a large facet of the market, with $233 million raised on Kickstarter in 2020.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Hall |first=Charlie |date=22 December 2020 |title=Games broke funding records on Kickstarter in 2020, despite the pandemic |url=https://www.polygon.com/2020/12/22/22195749/kickstarter-top-10-highest-funded-campaigns-2020-video-games-board-games |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201222221453/https://www.polygon.com/2020/12/22/22195749/kickstarter-top-10-highest-funded-campaigns-2020-video-games-board-games |archive-date=22 December 2020 |access-date=8 August 2021 |website=]}}</ref> | |||

| A 1991 estimate for the global board game market was over $1.2 billion.<ref name="BrowneBrowne2001">{{Cite book |last=Scanlon |first=Jennifer |title=The Guide to United States Popular Culture |publisher=Popular Press |year=2001 |isbn=978-0-87972-821-2 |editor-last=Browne |editor-first=Ray Broadus |page=103 |chapter=Board games |editor-last2=Browne |editor-first2=Pat |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=U3rJxPYT32MC&pg=PA103}}</ref> A 2001 estimate for the United States "board games and puzzle" market gave a value of under $400 million, and for United Kingdom, of about £50 million.<ref>{{Cite web |title=So you've invented a board game. Now what? |url=http://www.amherstlodge.com/games/reference/gameinvented.htm |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141115210052/http://www.amherstlodge.com/games/reference/gameinvented.htm |archive-date=15 November 2014 |access-date=26 November 2014}}</ref> A 2009 estimate for the Korean market was put at 800 million won,<ref>{{Cite news |date=22 July 2009 |title=Educational Games Getting Popular |work=The Korea Times |url=https://koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/nation/2009/07/113_48931.html |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160105035853/https://koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/nation/2009/07/113_48931.html |archive-date=5 January 2016}}</ref> and another estimate for the American board game market for the same year was at about $800 million.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Monopoly, Candy Land May Offer Refuge to Families in Recession |url=https://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=a2HEzwndjrVQ |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://archive.today/20141126045211/http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=a2HEzwndjrVQ |archive-date=26 November 2014 |website=]}}</ref> A 2011 estimate for the Chinese board game market was at over 10 billion ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Chinese Board Game Market Overview |url=http://www.lpboardgame.com/board-games-simple-chinese-board-game-market-overview/ |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160221075513/http://www.lpboardgame.com/board-games-simple-chinese-board-game-market-overview/ |archive-date=21 February 2016 |website=LP Board Game}}</ref> A 2013 estimate put the size of the German toy market at 2.7 billion euros (out of which the board games and puzzle market is worth about 375 million euros), and Polish markets at 2 billion and 280 million ], respectively.<ref>{{Cite web |date=16 April 2013 |title=Pamiętacie Eurobiznes? Oto wielki powrót gier planszowych, dla których oni zarywają noce |url=http://menstream.pl/wiadomosci-reportaze-i-wywiady/pamietacie-eurobiznes-oto-wielki-powrot-gier-planszowych-dla-ktorych-oni-zarywaja-noce,0,1288179.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160105041205/http://menstream.pl/wiadomosci-reportaze-i-wywiady/pamietacie-eurobiznes-oto-wielki-powrot-gier-planszowych-dla-ktorych-oni-zarywaja-noce%2C0%2C1288179.html |archive-date=5 January 2016 |website=Menstream.pl}}</ref> In 2009, Germany was considered to be the best market per capita, with the highest number of games sold per individual.<ref>{{Cite magazine |date=23 March 2009 |title=Monopoly Killer: Perfect German Board Game Redefines Genre |url=http://archive.wired.com/gaming/gamingreviews/magazine/17-04/mf_settlers?currentPage=all |url-status=dead |magazine=WIRED |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150510075137/http://archive.wired.com/gaming/gamingreviews/magazine/17-04/mf_settlers?currentPage=all |archive-date=10 May 2015 |access-date=23 April 2015}}</ref> | |||

| Another important aspect of some games is ], that is, players making deals with one another. Two-player games usually do not involve diplomacy (] being the exception). Thus, negotiation generally features only in games with three or more players. An important facet of '']'', for example, is convincing players to trade with you rather than with opponents. In '']'', two or more players may team up against others. ''Easy'' diplomacy involves convincing other players that someone else is winning and should therefore be teamed up against. ''Advanced'' diplomacy (e.g. in the aptly named game '']'') consists of making elaborate plans together, with the possibility of betrayal. | |||

| === Hobby board games === | |||

| Luck may be introduced into a game by a number of methods. The most common method is the use of ], generally six-sided. These can decide everything from how many steps a player moves their token, as in '']'', to how their forces fare in battle, such as in '']'', or which resources a player gains, such as in ''The Settlers of Catan''. Other games such as '']'' use a deck of special ]s that, when shuffled, create randomness. '']'' does something similar with randomly picked letters. Other games use spinners, timers of random length, or other sources of randomness. Trivia games have a great deal of randomness based on the questions a player must answer. ]s are notable for often having less luck element than many North American board games. | |||

| Some academics, such as Erica Price and Marco Arnaudo, have differentiated "hobby" board games and gamers from other board games and gamers.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Price |first=Erica |date=2020-10-01 |title=The Sellers of Catan: The Impact of on the United States Leisure and Business Landscape, 1995-2019 |journal=Board Game Studies Journal |language=en |volume=14 |issue=1 |pages=61–82 |doi=10.2478/bgs-2020-0004|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Arnaudo |first=Marco |date=2017-11-29 |title=The Experience of Flow in Hobby Board Games |url=https://analoggamestudies.org/2017/11/the-experience-of-flow-in-hobby-board-games/ |access-date=2023-09-03 |website=Analog Game Studies |language=en-US}}</ref> A 2014 estimate placed the U.S. and Canada market for hobby board games (games produced for a "gamer" market) at only $75 million, with the total size of what it defined as the "hobby game market" ("the market for those games regardless of whether they're sold in the hobby channel or other channels,") at over $700 million.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Hobby Games Market Hits $700M |url=https://icv2.com/articles/games/view/29326/hobby-games-market-hits-700m |access-date=2023-09-03 |website=icv2.com |language=en}}</ref> A similar 2015 estimate suggested a hobby game market value of almost $900 million.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Hobby Games Market Climbs to $880 Million |url=https://icv2.com/articles/markets/view/32102/hobby-games-market-climbs-880-million |access-date=2023-09-03 |website=icv2.com |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| == |

==Research== | ||

| {{multiple image|align=right|total_width=400 | |||

| Although many board games have a ] all their own, there is a generalized ] to describe concepts applicable to basic ]s and attributes common to nearly all board games. | |||

| |image1=Mathematicians playing Konane.jpg | |||

| ] board game]] | |||

| |width1=1280|height1=850 | |||

| ] | |||

| |caption1= | |||

| * '''Capture'''—a method that removes another player's game piece(s) from the board. For example: in ], if a player ] the opponent's piece, that piece is captured. | |||

| |image2=USMC-14131.jpg | |||

| * '''Card'''—a piece of cardboard often bearing instructions, and usually chosen randomly from a deck by shuffling. | |||

| |width2=2000|height2=3000 | |||

| * '''Deck'''—a stack of cards. | |||

| |caption2= | |||

| * '''Game piece''' (or '''gamepiece''', '''counter''', ''']''', '''bit''', '''meeple''', '''mover''', '''pawn''', '''man''', '''playing piece''', '''player piece''')—a player's representative on the gameboard made of a ] of ] made to look like a known object (such as a ] of a person, animal, or inanimate object) or otherwise general ]. Each player may control one or more game pieces. Some games involve commanding multiple game pieces (or ''units''), such as ]s or ], that have unique designations and capabilities within the ]s of the game; in other games, such as Go, all pieces controlled by a player have the same capabilities. In some modern board games, such as '']'', there are other pieces that are not a player's representative (i.e. weapons). In some games, pieces may not represent or belong to any particular player. (''See also:'' ]) | |||

| |footer=Board games serve diverse interests. {{em|Left:}} ] for studious competition. {{em|Right:}} kōnane for lighthearted fun.}} | |||

| * '''Gameboard''' (or simply '''board''')—the (usually ]) surface on which one plays a board game. The ] of the board game, gameboards would seem to be a ] of the ], though ]s that do not use a standard deck of cards (as well as games that use neither cards nor a gameboard) are often colloquially included. Most games use a standardized and unchanging board (], ], and ] each have such a board), but many games use a ''modular'' board whose component tiles or cards can assume varying layouts from one session to another, or even while the game is played. | |||

| A dedicated field of research into gaming exists, known as ] or ludology.<ref>{{Citation |last=Fernández-Vara |first=Clara |title=Adventure |url=https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780203114261-33/adventure-clara-fern%C3%A1ndez-vara |journal=The Routledge Companion to Video Game Studies |date=3 January 2014 |pages=232–240 |doi=10.4324/9780203114261-33 |access-date=2022-08-21 |archive-date=21 August 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220821035254/https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780203114261-33/adventure-clara-fern%C3%A1ndez-vara |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| * '''Hex''' (or '''cell''')—in hexagon-based board games, this is the common term for a standard space on the board. This is most often used in ], though many ] such as ], ], ], ] games, and ]s use hexagonal layouts. | |||

| * '''Jump''' (or '''leap''')—to bypass one or more game pieces or spaces. Depending on the context, jumping may also involve capturing or conquering an opponent's game piece. (''See also:'' ]) | |||

| While there has been a fair amount of scientific research on the psychology of older board games (e.g., ], ], ]), less has been done on contemporary board games such as '']'', '']'', and '']'',<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Gobet, Fernand |title=Moves in mind: The psychology of board games |last2=de Voogt, Alex |last3=Retschitzki, Jean |publisher=Psychology Press |year=2004 |isbn=978-1-84169-336-1 |author-link=Fernand Gobet}}</ref> and especially modern board games such as '']'', '']'', and '']''. Much research has been carried out on chess, partly because many tournament players are publicly ranked in national and international lists, which makes it possible to compare their levels of expertise. The works of ], William Chase, ], and ] have established that knowledge, more than the ability to anticipate moves, plays an essential role in chess-playing ability.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Simons |first=Daniel |date=15 February 2012 |title=How experts recall chess positions |url=http://theinvisiblegorilla.com/blog/2012/02/15/how-experts-recall-chess-positions/ |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171201041450/http://theinvisiblegorilla.com/blog/2012/02/15/how-experts-recall-chess-positions/ |archive-date=1 December 2017 |access-date=21 November 2017 |website=The Invisible Gorilla}}</ref> | |||

| * '''Space''' (or '''square''')—a ] of progress on a gameboard delimited by a distinct ], and not further divisible according to the game's rules. Alternatively, a unique position on the board on which a game piece in play may be located. For example, in ], the pieces are placed on grid line intersections, called '''points''', and not in the areas bounded by the borders, as in chess. (''See also:'' ]) | |||

| Linearly arranged board games have improved children's spatial numerical understanding. This is because the game is similar to a ] in that they promote a linear understanding of numbers rather than the innate logarithmic one.<ref>{{Cite news |title=Playing Linear Number Board Games—But Not Circular Ones—Improves Low-Income Preschoolers' Numerical Understanding |url=http://www.psy.cmu.edu/~siegler/sieg-ram09.pdf |url-status=dead |access-date=30 May 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110524170555/http://www.psy.cmu.edu/~siegler/sieg-ram09.pdf |archive-date=24 May 2011}}</ref> | |||

| Research studies show that board games such as ''Snakes and Ladders'' result in children showing significant improvements in aspects of basic number skills such as counting, recognizing numbers, numerical estimation, and number comprehension. They also practice fine motor skills each time they grasp a game piece.<ref>{{Cite web |last=LeFebvre |first=J.E. |title=Parenting the preschooler |url=http://parenting.uwex.edu/parenting-the-preschooler/documents/board_games.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140521002940/http://parenting.uwex.edu/parenting-the-preschooler/documents/board_games.pdf |archive-date=21 May 2014 |access-date=10 March 2015 |website=UW Extension}}</ref> Playing board games has also been tied to improving children's ]<ref>{{Cite web |last=Lahey |first=Jessica |date=16 July 2014 |title=How Family Game Night Makes Kids into Better Students |url=https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2014/07/how-family-game-night-makes-kids-into-better-students/374525/ |access-date=13 May 2019 |website=The Atlantic}}</ref> and help reduce risks of dementia for the elderly.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Dartigues |first1=Jean François |last2=Foubert-Samier |first2=Alexandra |last3=Le Goff |first3=Mélanie |last4=Viltard |first4=Mélanie |last5=Amieva |first5=Hélène |last6=Orgogozo |first6=Jean Marc |last7=Barberger-Gateau |first7=Pascale |last8=Helmer |first8=Catherine |date=2013 |title=Playing board games, cognitive decline and dementia: a French population-based cohort study |journal=BMJ Open |language=en |volume=3 |issue=8 |pages=e002998 |doi=10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002998 |issn=2044-6055 |pmc=3758967 |pmid=23988362}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Altschul |first1=Drew M |last2=Deary |first2=Ian J |year=2020 |editor-last=Taler |editor-first=Vanessa |title=Playing Analog Games Is Associated With Reduced Declines in Cognitive Function: A 68-Year Longitudinal Cohort Study |journal=The Journals of Gerontology: Series B |language=en |volume=75 |issue=3 |pages=474–482 |doi=10.1093/geronb/gbz149 |issn=1079-5014 |pmc=7021446 |pmid=31738418}}</ref> Related to this is a growing academic interest in the topic of game accessibility, culminating in the development of guidelines for assessing the accessibility of modern tabletop games<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Heron |first1=Michael James |last2=Belford |first2=Pauline Helen |last3=Reid |first3=Hayley |last4=Crabb |first4=Michael |date=27 April 2018 |title=Meeple Centred Design: A Heuristic Toolkit for Evaluating the Accessibility of Tabletop Games |journal=The Computer Games Journal |language=en |volume=7 |issue=2 |pages=97–114 |doi=10.1007/s40869-018-0057-8 |issn=2052-773X |doi-access=free|hdl=10059/2886 |hdl-access=free }}</ref> and the extent to which they are playable for people with disabilities.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Heron |first1=Michael James |last2=Belford |first2=Pauline Helen |last3=Reid |first3=Hayley |last4=Crabb |first4=Michael |date=21 April 2018 |title=Eighteen Months of Meeple Like Us: An Exploration into the State of Board Game Accessibility |url=http://discovery.dundee.ac.uk/ws/files/27828635/Heron2018_Article_EighteenMonthsOfMeepleLikeUsAn.pdf |url-status=live |journal=The Computer Games Journal |language=en |volume=7 |issue=2 |pages=75–95 |doi=10.1007/s40869-018-0056-9 |issn=2052-773X |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://discovery.dundee.ac.uk/ws/files/27828635/Heron2018_Article_EighteenMonthsOfMeepleLikeUsAn.pdf |archive-date=2022-10-09 |s2cid=5011817}}</ref> | |||

| Additionally, board games can be therapeutic. ], a ] said when interviewed about his game, ]:<blockquote>With crime you deal with every basic human emotion and also have enough elements to combine action with melodrama. The player's imagination is fired as they plan to rob the train. Because of the gamble, they take in the early stage of the game there is a build-up of tension, which is immediately released once the train is robbed. Release of tension is therapeutic and useful in our society because most jobs are boring and repetitive.<ref name="TRN1976">{{Cite news |date=December 1976 |title=Stealing the show |volume=2 |page=2 |work=Toy Retailing News |issue=4}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| Playing games has been suggested as a viable addition to the traditional educational curriculum if the content is appropriate and the gameplay informs students on the curriculum content.<ref>{{Cite magazine |last=Harris |first=Christopher |date=n.d. |title=Meet the New School Board: Board Games Are Back – And They're Exactly What Your Curriculum Needs |url=http://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ850549 |magazine=School Library Journal |volume=55 |issue=5 |pages=24–26 |issn=0362-8930 |access-date=23 April 2015}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Mewborne |first1=Michael |last2=Mitchell |first2=Jerry T. |date=3 April 2019 |title=Carcassonne: Using a Tabletop Game to Teach Geographic Concepts |url=https://doi.org/10.1080/19338341.2019.1579108 |journal=The Geography Teacher |volume=16 |issue=2 |pages=57–67 |doi=10.1080/19338341.2019.1579108 |bibcode=2019GeTea..16...57M |issn=1933-8341 |s2cid=181375208}}</ref> | |||

| ==Categories== | ==Categories== | ||

| There are |

There are several ways in which board games can be classified, and considerable overlap may exist, so that a game belongs to several categories.<ref name=fv/> | ||

| {{div col|colwidth=30em}} | |||

| The ] of the board game, ] would seem to be a ] of the ], though card games that do not use a standard deck of cards (as well as games that use neither cards nor a gameboard) are often colloquially included, with some scholars therefore referring to said genre as that of "table and board games" or "]", or seeing board games as a subgenre of tabletop games.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Woods |first=Stewart |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GPdRVOl8fU0C&q=%22game+board%22 |title=Eurogames: The Design, Culture and Play of Modern European Board Games |date=2012-08-30 |publisher=McFarland |isbn=978-0-7864-6797-6 |language=en}}</ref>{{Rp|page=5}}<ref>{{Cite book |last=Engelstein |first=Geoffrey |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OpEIEAAAQBAJ&dq=%22tabletop+games%22+%22game+board%22&pg=PP10 |title=Game Production: Prototyping and Producing Your Board Game |date=2020-12-21 |publisher=CRC Press |isbn=978-1-000-29098-1 |language=en}}</ref>{{Rp|page=1}} | |||

| * ]s—like chess, ], ], ], ], or modern games such as ], ], or ] | |||

| * Alignment games—like ], ], ], ], or ] | |||

| ]'s ''A History of Board Games Other Than Chess'' (1952) has been called the first attempt to develop a "scheme for the classification of board games".<ref name=":1">{{Cite web |title=SFE: Board Game |url=https://sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/board_game |access-date=2022-08-21 |website=sf-encyclopedia.com}}</ref> ]'s ''Oxford History of Board Games'' (1999) defines four primary categories: ]s (where the goal is to be the first to move all one's pieces to the final destination), ] (in which the object is to arrange the pieces into some special configuration), ] (asymmetrical games, where players start the game with different sets of pieces and objectives) and ] (where the main objective is the capture the opponents' pieces). Parlett also distinguishes between ] and ] games, the latter having a specific theme or frame narrative (ex. regular chess versus, for example, ]-themed chess).<ref name=":1" /> | |||

| * ]s—like ] or ] | |||

| * Configuration games—like ], Hexade, or '']'' | |||

| * ]s—like ] or ] | |||

| The following is a list of some of the most common game categories: | |||

| * ]s—like ''Max, Caves and Claws'' or '']'' | |||

| {{Div col|colwidth=25em}} | |||

| * ] games—like ''Tumblin' Dice'' or ''Pitch Car'' | |||

| * ]s – e.g. ], ], ], ], ], or modern games such as '']'', '']'', '']'', '']'', or '']'' | |||

| * ]s—like ''Arthur Saves the Planet'', ''Cleopatra and the Society of Architects'', or ''Shakespeare: The Bard Game'' | |||

| ** ]s – traditional variants e.g. ], ], or ]; modern variants e.g. ], ], ], or ] | |||

| * Elimination games—like ], ], ], or ] | |||

| * Alignment games – e.g. ], ], ], ], or ] | |||

| * Family games—like ''Roll Through the Ages'', ''Birds on a Wire'', or ''For Sale'' | |||

| * ] |

* ] – e.g. '']'', '']'' | ||

| * Configuration games – e.g. ], Hexade, or '']'' | |||

| * Historical simulation games—like ''Through the Ages'' or ''Railways of the World'' | |||

| * ]s – e.g. ], ], or ] | |||

| * Large multiplayer games—like '']'' or ''Swat'' (2010) | |||

| * ] – e.g. ''Max the Cat'', ''Caves and Claws'', or '']'' | |||

| * ]—like ] or The Glass Bead Game | |||

| * Count and capture games – e.g. ] games | |||

| * Musical games—like ''Spontuneous'' | |||

| * ] |

* ]s – e.g. ], ], or '']'' | ||

| * ] – e.g. '']'' or '']'' | |||

| * Position games (no captures; win by leaving the opponent unable to move)—like ] or the ] | |||

| * ] |

* ] games – e.g. ''Tumblin' Dice'' or ''Pitch Car'' | ||

| * ] |

* ] – e.g. '']'', '']'', '']'', '']'', or '']'' | ||

| * ]s – e.g. ''Arthur Saves the Planet'', '']'', or ''Shakespeare: The Bard Game'' | |||

| * Share-buying games—in which players buy stakes in each other's positions; typically longer economic-management games | |||

| * Elimination games – e.g. ], ], ], ], or ] | |||

| * Single-player ] games—like ] or ] | |||

| * |

* Family games – e.g. ''Roll Through the Ages'', ''Birds on a Wire'', or ''For Sale'' | ||

| * ] |

* ] – e.g. '']'' | ||

| * ]s or ''Eurogames'' – e.g. '']'', '']'', Decatur • The Game, Carson City, or '']'' | |||

| * Territory games—like ] or ] | |||

| * ]s – e.g. '']'' or ] | |||

| * ]s—like ], ''Steam'', or ] | |||

| * Hidden-movement games – e.g. ''Clue'' or Escape from the Aliens in Outer Space | |||

| * ] games—like '']'' | |||

| * Hidden-role games – e.g. '']'' or '']'' | |||

| * Two-player-only games—like ''En Garde'' or ''Dos de Mayo'' | |||

| * Historical simulation games – e.g. ''Through the Ages'' or '']'' | |||

| * Unequal forces (or "hunt") games—like ] or ] | |||

| * Horror games – e.g. '']''<ref>{{Cite web |date=3 August 2018 |title=Arkham Horror's 3rd Edition Gives the Game a Dramatic and Awesome Overhaul - Gen Con 2018 |url=https://www.ign.com/articles/2018/08/03/arkham-horrors-3rd-edition-gives-the-game-a-dramatic-and-awesome-overhaul-gen-con-2018 |website=Ign.com |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=20 December 2019 |title=The Best Horror and Zombie Board Games |url=https://www.ign.com/articles/the-best-horror-and-zombie-board-games |website=Ign.com |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| * ]—ranging from '']'' or '']'' or '']'', to '']'' or '']'' | |||

| * |

* Large multiplayer games – e.g. '']'' or ''Swat'' (2010) | ||

| * Learning/communication non-competitive games – e.g. ] (1972) | |||

| * ] – e.g. ], ], or The Glass Bead Game | |||

| * ]s – e.g. '']'', '']'', or ] | |||

| * Musical games – e.g. ''Spontuneous'' | |||

| * ] – e.g. '']'' | |||

| * ]s – e.g. ] or ] | |||

| * ] – e.g. '']'' | |||

| * Position games (no captures; win by leaving the opponent unable to move) – e.g. ], ], or the ] | |||

| * ]s – e.g. ], ], ], ], or ''Worm Up'' | |||

| * ] – e.g. ] | |||

| * ] games – e.g. '']'' or '']'' | |||

| * ]s – e.g. ] | |||

| * Share-buying games (games in which players buy stakes in each other's positions) – typically longer economic-management games, e.g. '']'' or '']'' | |||

| * Single-player ] games – e.g. '']'' or '']'' | |||

| * ] games - e.g. '']'' | |||

| * Spiritual development games (games with no winners or losers) – e.g. ''Transformation Game'' or ''Psyche's Key'' | |||

| * ] – e.g. ] or '']'' | |||

| * ] – e.g. '']'' or ''Tales of the Arabian Nights'' | |||

| * Territory games – e.g. ] or ] | |||

| * ] – e.g. '']'', '']'', '']'', or '']'' | |||

| * ]s – e.g. '']'', ''Steam'', or ] | |||

| * ] games – e.g. '']'' | |||

| * Two-player-only themed games – e.g. ''En Garde'' or ''Dos de Mayo'' | |||

| * Two-player-only abstract games - e.g. '']'' | |||

| * Unequal forces (or "hunt") games – e.g. ] or ] | |||

| * ] – ranging from '']'', '']'', or '']'', to '']'' or '']'' | |||

| * ]s – e.g. '']'', '']'', ], or ''What's My Word?'' (2010) | |||

| {{div col end}} | {{div col end}} | ||

| ==Glossary {{anchor|Common terms}}== | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| {{further|Glossary of board games}} | |||

| {{div col|colwidth=30em}} | |||

| Although many board games have a ] all their own, there is a generalized ] to describe concepts applicable to basic ]s and attributes common to nearly all board games. | |||

| * ] (Documentary, including interviews with game designers and game publishers) | |||

| * ] - DVD games | |||

| == See also == | |||

| {{div col|colwidth=27em}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ]—a website for board game enthusiasts | |||

| * '']''—a documentary movie | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ]—DVD games | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ], a board game café | |||

| * ], a board game community and website database | |||

| {{div col end}} | {{div col end}} | ||

| {{Portalbar|Strategy games|Chess|Role-playing games|Dungeons & Dragons}} | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{ |

{{reflist|colwidth=30em}} | ||

| ==Further reading== | ==Further reading== | ||

| {{refbegin|30em}} | {{refbegin|30em}} | ||

| * Austin, Roland G. "Greek Board Games." ''Antiquity'' 14. September 1940: 257–271 | * Austin, Roland G. "Greek Board Games." ''Antiquity'' 14. September 1940: 257–271 | ||

| * {{Cite book |last=Bell |first=R. C. |title=Board and Table Games From Many Civilizations |publisher=] Inc |year=1979 |isbn=978-0-671-06030-5 |edition=Revised |volume=I |author-link=Robert Charles Bell |orig-year=1st Pub. 1960, ], London}} | |||

| * ]. ''The Boardgame Book''. ]: Bookthrift Company, 1979. | |||

| * Bell |

* {{Cite book |last=Bell |first=R. C. |title=Board and Table Games From Many Civilizations |publisher=] Inc |year=1979 |isbn=978-0-671-06030-5 |edition=Revised |volume=II |author-link=Robert Charles Bell |orig-year=1st Pub. 1969, ], London}} | ||

| * {{Cite book |last=Bell |first=R. C. |title=The Boardgame Book |publisher=Exeter Books |year=1983 |isbn=978-0-671-06030-5 |author-link=Robert Charles Bell}} | |||

| ** Reprint: ]: Exeter Books, 1983. | |||

| * Falkener |

* {{Cite book |last=Falkener |first=Edward |url=https://archive.org/details/GamesAncientAndOriental |title=Games Ancient and Oriental and How to Play Them |publisher=] Inc |year=1961 |isbn=978-0-486-20739-1 |author-link=Edward Falkener |orig-year=1892}} | ||

| * ]. ''Chess in Iceland and in Icelandic Literature—with historical notes on other table-games''. Florentine Typographical Society, 1905. | * ]. . Florentine Typographical Society, 1905. | ||

| * {{ |

* {{Cite book |last1=Gobet |first1=Fernand |title=Moves in mind: The psychology of board games |last2=de Voogt, Alex |last3=Retschitzki, Jean |publisher=Psychology Press |year=2004 |isbn=978-1-84169-336-1 |author-link=Fernand Gobet |author-link2=Alexander de Voogt |name-list-style=amp}} | ||

| * Golladay, Sonja Musser, (PhD diss., University of Arizona, 2007) | * Golladay, Sonja Musser, (PhD diss., University of Arizona, 2007) | ||