| Revision as of 14:20, 9 May 2007 editUltramarine (talk | contribs)33,507 edits rv← Previous edit | Revision as of 14:34, 9 May 2007 edit undoCkenniss (talk | contribs)9 editsNo edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

| ==Theories about the decline and fall of the Roman Empire== | ==Theories about the decline and fall of the Roman Empire== | ||

| There were many reasons for the fall of the Roman Empire. Each one intertwined with the next. Many even blame the introduction of Christianity for the decline. Christianity made many Roman citizens into pacifists, making it more difficult to defend against the barbarian attackers. Also money used to build churches could have been used to maintain the empire. Although some argue that Christianity may have provided some morals and values for a declining civilization and therefore may have actually prolonged the imperial era. | |||

| ===Vegetius=== | |||

| Decline in Morals and Values | |||

| The military historian ] theorized, and has recently been supported by the historian ], that the Roman Empire – particularly the military – declined partially as a result of an influx of Germanic mercenaries into the ranks of the legions. This "Germanization" and the resultant cultural dilution or "barbarization", led to lethargy, complacency and loyalty to the Roman commanders among the legions and a surge in decadence amongst Roman citizenry. | |||

| Those morals and values that kept together the Roman legions and thus the empire could not be maintained towards the end of the empire. Crimes of violence made the streets of the larger cities unsafe. Even during PaxRomana there were 32,000 prostitutes in Rome. Emperors like Nero and Caligula became infamous for wasting money on lavish parties where guests ate and drank until they became ill. The most popular amusement was watching the gladiatorial combats in the Colosseum. These were attended by the poor, the rich, and frequently the emperor himself. As gladiators fought, vicious cries and curses were heard from the audience. One contest after another was staged in the course of a single day. Should the ground become too soaked with blood, it was covered over with a fresh layer of sand and the performance went on. | |||

| ===Edward Gibbon=== | |||

| ] famously placed the blame on a loss of ] among the Roman citizens. They gradually ] their duties to defend the Empire to ] ] who eventually turned on them. Gibbon considered that ] had contributed to this, making the populace less interested in the worldly ''here-and-now'' and more willing to wait for the rewards of ]. "he decline of Rome was the natural and inevitable effect of immoderate greatness. Prosperity ripened the principle of decay; the causes of destruction multiplied with the extent of conquest; and as soon as time or accident had removed the artificial supports, the stupendous fabric yielded to the pressure of its own weight," he wrote. "In discussing Barbarism and Christianity I have actually been discussing the Fall of Rome." | |||

| ===Public Health=== | |||

| Gibbon's work is notable for its erratic, but exhaustively documented, notes and research. Interestingly, since he was writing in the ], Gibbon also mentioned the climate, while reserving naming it as a cause of the decline, saying "the climate (whatsoever may be its influence) was no longer the same." While judging the loss of civic virtue and the rise of Christianity to be a lethal combination, Gibbon did find other factors possibly contributing in the decline. | |||

| There were many public health and environmental problems. Many of the wealthy had water brought to their homes through lead pipes. Previously the aqueducts had even purified the water but at the end lead pipes were thought to be preferable. The wealthy death rate was very high. The continuous interaction of people at the Colosseum, the blood and death probable spread disease. Those who lived on the streets in continuous contact allowed for an uninterrupted strain of disease much like the homeless in the poorer run shelters of today. Alcohol use increased as well adding to the incompetency of the general public. | |||

| ===Henri Pirenne=== | |||

| In the second half of the ] some historians started to promote a continuity between the Roman world and the post-Roman Germanic kingdoms. ] in ''Histoire des institutions politiques de l'ancienne France'' (1875-1889) argued the barbarians simply accelerated a running process and they continued the transforming Roman institutions. | |||

| ===Political Corruption=== | |||

| ] continued this idea in "Pirenne Thesis", published in the ], which remains influential to this day. It holds that the Empire continued, in some form, up until the time of the ] in the ], which disrupted ] trade routes, leading to a decline in the ] economy. This theory stipulates the rise of the ] as a continuation of the Roman Empire, and thus legitimizes the crowning of ] as the first ] as a continuation of the Imperial Roman state. | |||

| One of the most difficult problems was choosing a new emperor. Unlike Greece where transition may not have been smooth but was at least consistent, the Romans never created an effective system to determine how new emperors would be selected. The choice was always open to debate between the old emperor, the Senate, the Praetorian Guard (the emperor's's private army), and the army. Gradually, the Praetorian Guard gained complete authority to choose the new emperor, who rewarded the guard who then became more influential, perpetuating the cycle. Then in 186 A. D. the army strangled the new emperor, the practice began of selling the throne to the highest bidder. During the next 100 years, Rome had 37 different emperors - 25 of whom were removed from office by assassination. This contributed to the overall weaknesses of the empire. | |||

| Pirenne's view on the continuity of the Roman Empire before and after the Germanic invasion was supported by recent historians such as ], ] and ]. | |||

| ===Unemployment=== | |||

| However, some critics maintain the "Pirenne Thesis" erred in claiming the ] realm as a Roman state, and mainly dealt with the Islamic conquests and their effect on the Byzantine or Eastern Empire. | |||

| During the latter years of the empire farming was done on large estates called latifundia that were owned by wealthy men who used slave labor. A farmer who had to pay workmen could not produce goods as cheaply. Many farmers could not compete with these low prices and lost or sold their farms. This not only undermined the citizen farmer who passed his values to his family, but also filled the cities with unemployed people. At one time, the emperor was importing grain to feed more than 100,000 people in Rome alone. These people were not only a burden but also had little to do but cause trouble and contribute to an ever increasing crime rate. | |||

| Other modern critics stipulate that while Pirenne is correct in his assertion of the continuation of the Empire beyond the sack of Rome, the Arab conquests in the ] may not have disrupted ] trade routes to the degree that Pirenne suggests. ] in particular notes that more recent sources, such as unearthed collective biographies, notate new trade routes through correspondences in communication. Moreover, records such as book-keepings and coins suggest the movement of Islamic currency into the Carolingian Empire. McCormick concludes that if money is coming in, some form of trade is going out - possibly European slaves to the Arabic states, as Islam forbid the use of their own as slaves. | |||

| === |

===Inflation=== | ||

| ]'s ''History of the Later Roman Empire'' gives a multi-factored theory for the Fall of the Western Empire. He presents the classic "Christianity vs. pagan" theory, and debunks it, citing the relative success of the Eastern Empire, which was far more Christian. | |||

| The roman economy suffered from inflation (an increase in prices) beginning after the reign of Marcus Aurelius. Once the Romans stopped conquering new lands, the flow of gold into the Roman economy decreased. Yet much gold was being spent by the romans to pay for luxury items. This meant that there was less gold to use in coins. As the amount of gold used in coins decreased, the coins became less valuable. To make up for this loss in value, merchants raised the prices on the goods they sold. Many people stopped using coins and began to barter to get what they needed. Eventually, salaries had to be paid in food and clothing, and taxes were collected in fruits and vegetables. | |||

| He then examines Gibbon's "theory of moral decay," and without insulting Gibbon, finds that too simplistic, though a partial answer. He essentially presents what he called the "modern" theory, which he implicitly endorses, a combination of factors, primarily, (quoting directly from Bury):<ref>http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/secondary/BURLAT/9*.html#7 </ref> | |||

| ===Urban decay=== | |||

| :"... the Empire had come to depend on the enrollment of barbarians, in large numbers, in the army, and ... it was necessary to render the service attractive to them by the prospect of power and wealth. This was, of course, a consequence of the decline in military spirit, and of depopulation, in the old civilised Mediterranean countries. The Germans in high command had been useful, but the dangers involved in the policy had been shown in the cases of Merobaudes and Arbogastes. Yet this policy need not have led to the dismemberment of the Empire, and but for that series of chances its western provinces would not have been converted, as and when they were, into German kingdoms. It may be said that a German penetration of western Europe must ultimately have come about. But even if that were certain, it might have happened in another way, at a later time, more gradually, and with less violence. The point of the present contention is that Rome's loss of her provinces in the fifth century was not an "inevitable effect of any of those features which have been rightly or wrongly described as causes or consequences of her general 'decline.'" The central fact that Rome could not dispense with the help of barbarians for her wars (gentium barbararum auxilio indigemus) may be held to be the cause of her calamities, but it was a weakness which might have continued to be far short of fatal but for the sequence of contingencies pointed out above."<ref></ref> | |||

| Wealthy Romans lived in a domus, or house, with marble walls, floors with intricate colored tiles, and windows made of small panes of glass. Most Romans, however, were not rich, They lived in small smelly rooms in apartment houses with six or more stories called islands. Each island covered an entire block. At one time there were 44,000 apartment houses within the city walls of Rome. First-floor apartments were not occupied by the poor since these living quarters rented for about $00 a year. The more shaky wooden stairs a family had to climb, the cheaper the rent became. The upper apartments that the poor rented for $40 a year were hot, dirty, crowed, and dangerous. Anyone who could not pay the rent was forced to move out and live on the crime-infested streets. Because of this cities began to decay. | |||

| In short, Bury held that a number of contingencies arose simultaneously: economic decline, Germanic expansion, depopulation of Italy, dependency on Germanic foederati for the military, the disastrous (though Bury believed unknowing) treason of ], loss of martial vigor, ]' murder, the lack of any leader to replace Aetius — a series of misfortunes which proved catastrophic in combination. | |||

| ===Inferior Technology=== | |||

| Bury noted that Gibbon's "Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire" was "amazing" in its research and detail. Bury's main differences from Gibbon lay in his interpretation of fact, rather than any dispute of fact. He made clear that he felt that Gibbon's conclusions as to the "moral decay" were viable — but not complete. Bury's judgement was that: | |||

| During the last 400 years of the empire, the scientific achievements of the Romans were limited almost entirely to engineering and the organization of public services. They built marvelous roads, bridges, and aqueducts. They established the first system of medicine for the benefit of the poor. But since the Romans relied so much on human and animal labor, they failed to invent many new machines or find new technology to produce goods more efficiently. They could not provide enough goods for their growing population. They were no longer conquering other civilizations and adapting their technology, they were actually losing territory they could not longer maintain with their legions. | |||

| :"the gradual collapse of the Roman power ...was the consequence of a series of contingent events. No general causes can be assigned that made it inevitable." | |||

| ===Military Spending=== | |||

| It is his theory that the decline and ultimate fall of Rome was not pre-ordained, but was brought on by contingent events, each of them separately endurable, but together and in conjunction ultimately destructive. | |||

| Maintaining an army to defend the border of the Empire from barbarian attacks was a constant drain on the government. Military spending left few resources for other vital activities, such as providing public housing and maintaining quality roads and aqueducts. Frustrated Romans lost their desire to defend the Empire. The empire had to begin hiring soldiers recruited from the unemployed city mobs or worse from foreign counties. Such an army was not only unreliable, but very expensive. The emperors were forced to raise taxes frequently which in turn led again to increased inflation. | |||

| ===William Carroll Bark=== | |||

| ] argues in ''Origins of the Medieval World'' (1958) that the Empire fell due to the efforts of keeping it together. The roots of ] developed when the colonus (a pre-cursor of the ]) was legally bound to his role of tenant farming so that collection of taxes would be easier. The Imperial government collected fixed grain taxes from tenant farmers. Since it was impossible for the government to keep track of its large grain supply, the middle class was legally required to collect taxes. With citizens bound to certain local roles, feudalism began developing before the Middle Ages had even begun. | |||

| Bark also cites the scarcity of gold in the late empire as a reason for its decline. Currency inflated as it was no longer made of real gold. No longer wanting to be paid with money, soldiers and wealthy citizens chose instead to be paid with actual objects of value. It became difficult for the government to retain any money for itself, and it began to resort more and more to cheaper mercenaries to defend it. | |||

| === |

===THE FINAL BLOWS!!!=== | ||

| For years, the well-disciplined Roman army held the barbarians of Germany back. Then in the third century A. D. the Roman soldiers were pulled back from the Rhine-Danube frontier to fight civil war in Italy. This left the Roman border open to attack. Gradually Germanic hunters and herders from the north began to overtake Roman lands in Greece and Gaul (later France). Then in 476 A. D. the Germanic general Odacer or Odovacar overthrew the last of the Roman Emperors, Augustulus Romulus. From then on the western part of the Empire was ruled by Germanic chieftain. Roads and bridges were left in disrepair and fields left untilled. Pirates and bandits made travel unsafe. Cities could not be maintained without goods from the farms, trade and business began to disappear. And Rome was no more in the West. | |||

| On the other hand, some historians have argued that the collapse of Rome was outside the Romans' control. ] holds that technology drives history. Thus, the invention of the ] in ] in the 200s would alter the military equation of ''pax romana'', as would a borrowing of the ] from its inventors in China in the 300s. | |||

| ===Lucien Musset and the clash of civilizations=== | |||

| In the spirit of "Pirenne thesis", a school of thought pictured a clash of civilizations between the Roman and the Germanic world, a process taking place roughly between 3rd and 8th century AD. | |||

| ===Environmental degradation=== | |||

| The ] historian ] studying the ], argues the civilization of ] ] emerged from a synthesis between the ] world and the ] civilizations penetrating the Roman Empire. The Roman Empire did not fall, did not decline, it just transformed but so did the Germanic populations which invaded it. To support this conclusion, beside the narrative of the events, he offers ] overviews of ] and ], analyzes archaeological records, studies the urban and rural society, the institutions, the religion, the art, the technology. | |||

| Another theory is that gradual environmental degradation caused population and economic decline. ] and excessive grazing led to ] of meadows and cropland. Increased irrigation caused ]. These human activities resulting in fertile land becoming nonproductive and eventually increased desertification in some regions. Many animal species become extinct.<ref>http://www.humecol.lu.se/woshglec/papers/hughes.doc </ref> See also ]. | |||

| ===Late Antiquity=== | |||

| ===Arnold J. Toynbee and James Burke=== | |||

| Historians of ], a field pioneered by ], have turned away from the idea that the Roman Empire "fell" refocusing on Pirenne's thesis. They see a "transformation" occurring over centuries, with the roots of ] culture contained in Roman culture and focus on the continuities between the classical and Medieval worlds. Thus, it was a gradual process with no clear break. | |||

| In contrast with the "declining empire" theories, historians such as ] and ] argue that the Roman Empire itself was a rotten system from its inception, and that the entire Imperial era was one of steady decay of institutions founded in ] times. In their view, the Empire could never have lasted without radical reforms. The Romans had no budgetary system and thus wasted whatever resources they had available. The Roman economy was basically ], plunder economy, which was based on ] existing resources rather than producing anything new. The Empire relied on booty from conquered territories (this source of revenue ending, of course, with the end of Roman territorial expansion) or on a pattern of tax collection that drove small-scale farmers into destitution (and onto a ] that required even more exactions upon those who could not escape taxation), or into dependency upon a landed élite exempt from taxation. | |||

| ==Historiography== | |||

| An economy based upon slave labor precluded a middle class with purchasing power. The Roman Empire produced few exportable goods. Material innovation, whether through entrepreneurialism or technological advancement, all but ended long before the final dissolution of the Empire. Meanwhile the costs of military defense and the pomp of Emperors continued. Financial needs continued to increase, but the means of meeting them steadily eroded. By the late fifth century the barbarian conqueror ] had no use for the formality of an Empire upon deposing ] and chose neither to assume the title of Emperor himself nor to select a puppet. The formal end of the Roman Empire corresponds with the time in which the Empire and the title Emperor no longer had value. | |||

| ] | |||

| ], the primary issue historians have looked at when analyzing any theory is the continued existence of the ] or ], which lasted for about a thousand years after the fall of the West. For example, Gibbon implicates Christianity in the fall of the Western Empire, yet the eastern half of the Empire, which was even more Christian than the west in geographic extent, fervor, penetration and sheer numbers continued on for a thousand years afterwards (although Gibbon did not consider the Eastern Empire to be much of a success). As another example, environmental or weather changes impacted the east as much as the west, yet the east did not "fall." | |||

| In a somewhat similar vein, ] argues that the Empire's collapse was caused by a diminishing marginal return on investment in complexity, a limitation to which most complex societies are eventually subject. | |||

| Theories will sometimes reflect the particular concerns that historians might have on cultural, political, or economic trends in their own times. Gibbon's criticism of Christianity reflects the values of the ]; his ideas on the decline in martial vigor could have been interpreted by some as a warning to the growing ]. In the ] ] and anti-socialist theorists tended to blame ] and other political problems. More recently, ]al concerns have become popular, with ] and ] proposed as major factors, and destabilizing population decreases due to ]s such as early cases of ] and ] also cited. Global ] caused by the eruption of ] in 535, as mentioned by ] and others, is another example. Ideas about transformation with no distinct fall mirror the rise of the ] tradition, which rejects ] concepts (see ]). What is not new are attempts to diagnose Rome's particular problems, with ], written by Juvenal in the early ] at the height of Roman power, criticizing the peoples' obsession with "]" and rulers seeking only to gratify these obsessions. | |||

| ===Michael Rostovtzeff, Ludwig von Mises, and Bruce Bartlett === | |||

| Historian ] and economist ] both argued that unsound economic policies played a key role in the impoverishment and decay of the Roman Empire. According to them, by the ] A.D., the Roman Empire had developed a complex ] in which trade was relatively free. ]s were low and laws controlling the prices of foodstuffs and other commodities had little impact because they did not fix the prices significantly below their market levels. After the ], however, ] of the currency (i.e., the minting of coins with diminishing content of ], ], and led to ]. The ] laws then resulted in prices that were significantly below their free-market equilibrium levels. | |||

| One of the primary reasons for the sheer number of theories is the notable lack of surviving evidence from the 4th and 5th centuries. For example there are so few records of an economic nature it is difficult to arrive at even a generalization of the economic conditions. Thus, historians must quickly depart from available evidence and comment based on how things ought to have worked, or based on evidence from previous and later periods, on ]. As in any field where available evidence is sparse, the historian's ability to imagine the 4th and 5th centuries will play as important a part in shaping our understanding as the available evidence, and thus be open for endless interpretation. | |||

| According to Rostovtzeff and Mises, artificially low prices led to the scarcity of foodstuffs, particularly in ], whose inhabitants depended on trade in order to obtain them. Despite laws passed to prevent migration from the cities to the countryside, urban areas gradually became depopulated and many Roman citizens abandoned their specialized trades in order to practice ]. This, coupled with increasingly oppressive and arbitrary ], led to a severe net decrease in trade, ] innovation, and the overall wealth of the empire.<ref>See, for instance, , by ], and , by ]</ref> | |||

| The end of the Western Roman Empire traditionally has been seen by historians to mark the end of the ] and beginning of the ]. More recent schools of history, such as ], offer a more nuanced view from the traditional historical narrative. | |||

| ] traces the beginning of debasement to the reign of ]. By the third century the monetary economy had collapsed. Bartlett sees the end result as a form of state ]. Monetary taxation was replaced with direct requisitioning, for example taking food and cattle from farmers. Individuals were forced to work at their given place of employment and remain in the same occupation. Farmers became tied to the land, as were their children, and similar demands were made on all other workers, producers, and artisans as well. Workers were organized into ]s and businesses into corporations called collegia. Both became de facto organs of the state, controlling and directing their members to work and produce for the state. In the countryside people attached themselves to the estates of the wealthy in order to gain some protection from state officials and tax collectors. These estates, the beginning of feudalism, operated as much as possible as closed systems, providing for all their own needs and not engaging in trade at all.<ref> , by ]</ref> | |||

| === |

==='The Collapse' Chronology=== | ||

| 337 May 22, death of Constantine the Great | |||

| ] (b.1917), a ], noted in chapter three of his book ''Plagues and Peoples'' (1976) that the Roman Empire suffered the severe and protacted ] starting around 165 A.D. For about twenty years, waves of one or more diseases, possibly the first epidemics of ] and/or ], swept through the Empire, ultimately killing about half the population. Similar epidemics also occurred in the third century. McNeill argues that the severe fall in population left the state apparatus and army too large for the population to support, leading to further economic and social decline that eventually killed the Western Empire. The Eastern half survived due to its larger population, which even after the plagues was sufficient for an effective state apparatus. | |||

| 337 Division of the empire between Constantine's three sons: Constantine II (west), Constans (middle), Constantius (east). Execution of all other princes of royal blood, but for the children Gallus and Julian. | |||

| This theory can also be extended to the time after the fall of the Western Empire and to other parts of the world. Similar epidemics caused by new diseases may have weakened the Chinese ] and contributed to its collapse. This was followed by the long and chaotic period sometimes called the Chinese Dark Ages. Later, the ] may have been the first instance of ]. It, and subsequent recurrences, may have been so devastating that they helped the Arab conquest of most of the Eastern Empire and the whole of the ]. Archaeological evidence is showing that Europe continued to have had a steady downward trend in population starting as early as the 2nd century and continuing through the 7th centuries. The European recovery may have started only when the population, through ], had gained some resistance to the new diseases. See also ]. | |||

| 338 Constantius attends to the war against Persia. First unsuccessful siege of Nisibis by Sapor II | |||

| ===Peter Heather=== | |||

| ] offers an alternate theory of the decline of the Roman Empire in the work ''The Fall of the Roman Empire'' (2005). Heather maintains the Roman imperial system with its sometimes violent imperial transitions and problematic communications notwithstanding, was in fairly good shape during the first, second, and part of the third centuries A.D. According to Heather, the first real indication of trouble was the emergence in Iran of the ] Persian empire (226-651). Heather says: | |||

| 340 Constans and Constantine II at war. Battle of Aquileia; death of Constantine II. | |||

| ::"The Sassanids were sufficiently powerful and internally cohesive to push back Roman legions from the Euphrates and from much of Armenia and southeast Turkey. Much as modern readers tend to think of the "Huns" as the nemesis of the Roman Empire, for the entire period under discussion it was the Persians who held the attention and concern of Rome and Constantinople. Indeed, 20-25% of the military might of the Roman Army was addressing the Persian threat from the late third century onward ... and upwards of 40% of the troops under the Eastern Emperors."<ref>http://anglosphere.com/weblog/archives/000350.html </ref> | |||

| 344 Persian victory at Singara | |||

| Heather goes on to state — and he is confirmed by Gibbon and Bury — that it took the Roman Empire about half a century to cope with the Sassanid threat, which it did by stripping the western provincial towns and cities of their regional taxation income. The resulting expansion of military forces in the Middle East was finally successful in stabilizing the frontiers with the Sassanids, but the reduction of real income in the provinces of the Empire led to two trends which, Heather says, had a negative long term impact. Firstly, the incentive for local officials to spend their time and money in the development of local infrastructure disappeared. Public buildings from the 4th century onward tended to be much more modest and funded from central budgets, as the regional taxes had dried up. Secondly, Heather says "the landowning provincial literati now shifted their attention to where the money was ... away from provincial and local politics to the imperial bureaucracies." | |||

| 346 Second unsuccessful siege of Nisibis by Sapor II | |||

| Having set the scene of an Empire stretched militarily by the Sassanid threat, Heather then suggests, using archaeological evidence, that the Germanic tribes on the Empire's northern border had altered in nature since the 1st century AD. Contact with the Empire had increased their material wealth, and that in turn had led to disparities of wealth sufficient to create a ruling class capable of maintaining control over far larger groupings than had previously been possible. Essentially they had become significantly more formidable foes. | |||

| 350 Third siege of Nisibis. Owing to incursions of the Massagetae in Transoxiana, Sapor II makes truce with Constantius. | |||

| Heather then posits what amounts to a domino theory — namely that pressure on peoples very far away from the Empire could result in sufficient pressure on peoples on the Empire's borders to make them contemplate the risk of full scale immigration to the empire. Thus he links the Gothic invasion of 376 directly to Hunnic movements around the Black Sea in the decade before. In the same way he sees the invasions across the Rhine in 406 as a direct consequence of further Hunnic incursions in Germania; as such he sees the Huns as deeply significant in the fall of the Western Empire long before they themselves became a military threat to the Empire. | |||

| Magnentius murders Constans and becomes emperor in the west. Vetranio proclaimed emperor on the Danube frontier. On appearance of Constantius, Vetranio resumes allegiance. | |||

| 351 Magnetnius defeated at the very bloody Battle of Mursa. Misrule by Gallus, left as Caesar in the east. | |||

| An empire at maximum stretch due to the Sassanids, then, encountered, due to the Hunnic expansion, unprecedented immigration in 376 and 406 by barbarian groupings who had become significantly more politically and militarily capable than in previous eras. Essentially he argues that the external pressures of 376-470 could have brought the Western Empire down at any point in its history. | |||

| 352 Italy recovered. Magnentius in Gaul. | |||

| His theory is both modern and relevant in that he disputes Gibbon's contention that Christianity and moral decay led to the decline. He also rejects the political infighting of the Empire as a reason, considering it was a systemic recurring factor throughout the Empire's history which, while it might have contributed to an inability to respond to the circumstances of the 5th century, it consequently cannot be blamed for them. Instead he places its origin squarely on outside military factors, starting with the Great Sassanids. Like Bury, he does not believe the fall was inevitable, but rather a series of events which came together to shatter the Empire. He differs from Bury, however, in placing the onset of those events far earlier in the Empire's timeline, with the Sassanid rise. | |||

| 353 Final defeat and death of Magnentius | |||

| ===Bryan Ward-Perkins=== | |||

| ]'s ''The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization'' (2005) takes a traditional view tempered by modern discoveries, arguing that the empire's demise was brought about through a vicious cycle of political instability, foreign invasion, and reduced tax revenue. Essentially, invasions caused long-term damage to the provincial tax base, which lessened the Empire's medium to long-term ability to pay and equip the legions, with predictable results. Likewise, constant invasions encouraged provincial rebellion as self-help, further depleting Imperial resources. Contrary to the trend among some historians of the "there was no fall" school, who view the fall of Rome as not necessarily a "bad thing" for the people involved, Ward-Perkins argues that in many parts of the former Empire the archaeological record indicates that the collapse was truly a disaster. | |||

| 354 Execution of Gallus. Julian at Athens | |||

| Ward-Perkins' theory, much like Bury's, and Heather's, identifies a series of cyclic events that came together to cause a definite decline and fall. | |||

| 356 Julian dispatched as Caesar to Gaul. War with teh Alemanni, Quadi and Sarmatians. Military achievements by Julian. | |||

| ===Environmental degradation=== | |||

| Another theory is that gradual environmental degradation caused population and economic decline. ] and excessive grazing led to ] of meadows and cropland. Increased irrigation caused ]. These human activities resulting in fertile land becoming nonproductive and eventually increased desertification in some regions. Many animal species become extinct.<ref>http://www.humecol.lu.se/woshglec/papers/hughes.doc </ref> See also ]. | |||

| 357 Challenge by Sapor II | |||

| ===Late Antiquity=== | |||

| Historians of ], a field pioneered by ], have turned away from the idea that the Roman Empire "fell" refocusing on Pirenne's thesis. They see a "transformation" occurring over centuries, with the roots of ] culture contained in Roman culture and focus on the continuities between the classical and Medieval worlds. Thus, it was a gradual process with no clear break. | |||

| 359 Sapor II invades Mesopotamia. Constantius goes to the east. | |||

| ==Historiography== | |||

| ] | |||

| 360 The Gallic army forces Julian to revolt. Julian marches down the Danube to Moesia. | |||

| ], the primary issue historians have looked at when analyzing any theory is the continued existence of the ] or ], which lasted for about a thousand years after the fall of the West. For example, Gibbon implicates Christianity in the fall of the Western Empire, yet the eastern half of the Empire, which was even more Christian than the west in geographic extent, fervor, penetration and sheer numbers continued on for a thousand years afterwards (although Gibbon did not consider the Eastern Empire to be much of a success). As another example, environmental or weather changes impacted the east as much as the west, yet the east did not "fall." | |||

| 361 Constantius dies. Julian the Apostate emperor. | |||

| Theories will sometimes reflect the particular concerns that historians might have on cultural, political, or economic trends in their own times. Gibbon's criticism of Christianity reflects the values of the ]; his ideas on the decline in martial vigor could have been interpreted by some as a warning to the growing ]. In the ] ] and anti-socialist theorists tended to blame ] and other political problems. More recently, ]al concerns have become popular, with ] and ] proposed as major factors, and destabilizing population decreases due to ]s such as early cases of ] and ] also cited. Global ] caused by the eruption of ] in 535, as mentioned by ] and others, is another example. Ideas about transformation with no distinct fall mirror the rise of the ] tradition, which rejects ] concepts (see ]). What is not new are attempts to diagnose Rome's particular problems, with ], written by Juvenal in the early ] at the height of Roman power, criticizing the peoples' obsession with "]" and rulers seeking only to gratify these obsessions. | |||

| 362 Christians forbidden to teach. Julian's advance against Persians | |||

| One of the primary reasons for the sheer number of theories is the notable lack of surviving evidence from the 4th and 5th centuries. For example there are so few records of an economic nature it is difficult to arrive at even a generalization of the economic conditions. Thus, historians must quickly depart from available evidence and comment based on how things ought to have worked, or based on evidence from previous and later periods, on ]. As in any field where available evidence is sparse, the historian's ability to imagine the 4th and 5th centuries will play as important a part in shaping our understanding as the available evidence, and thus be open for endless interpretation. | |||

| 363 Disaster and death of Julian. Retreat of the army which proclaims Jovian emperor. Humiliating peace with Persia. Renewed toleration decree. | |||

| 364 Jovian nominates Valentinian and dies. | |||

| Valentinian associates his brother Valens as eastern emperor and takes the west for himself. Permanent duality of the empire inaugurated. | |||

| 366 Damasus pope. Social and political influences become a feature of papal elections. | |||

| 367 Valentinian sends his son Gratian as Augustus to Gaul. Theodosius the elder in Britain. | |||

| 368 War of Valens with Goths | |||

| 369 Peace with Goths | |||

| 369-377 Subjugation of Ostrogoths by Hun invasion | |||

| 374 Pannonian War of Valentinian. Ambrose Bishop of Milan | |||

| 375 Death of Valentinian. Accession of Gratian, who associates his infant brother Valentinian II at Milan. Gratian first emperor to refuse the office of Pontifex Maximus. Theodosius the elder in Africa. | |||

| 376 Execution of elder and retirement of younger Theodosius. | |||

| 377 Valens receives and settles Visigoths in Moesia. | |||

| 378 Gratian defeats Alemanni. Rising of Visigoths. Valens killed at disaster at Adrianople. | |||

| 380 Gratian nominates the younger Theodosius as successor to Valens. | |||

| 382 Treaty of Theodosius with Visigoths | |||

| 383 Revolt of Maximus in Britain. Flight and death of Gratian. Theodosius recognizes Maximus in the west and Valentinian II at Milan. | |||

| 386 Revolt of Gildo in Africa | |||

| 387 Theodosius crushes Maximus, makes Arbogast the Frank master of the soldiers to Valentinian II | |||

| 392 Murder of Valentinian II. Arbogast sets up Eugenius. | |||

| 394 Fall of Arbogast and Eugenius. Theodosius makes his younger son Honorius western Augustus, with the Vandal Stilicho master of the soldiers. | |||

| 395 Theodosius dies. Arcadius and Honorius emperors. | |||

| 396 Alaric the Visigoth overruns Balkan peninsula. | |||

| 397 Alaric checked by Stilicho, is given Illyria. | |||

| 398 Suppression of Gildo in Afrca | |||

| 402 Alaric invades Italy, checked by Stilicho | |||

| 403 Alaric retires after defeat at Pollentia. | |||

| Ravenna becomes imperial headquarters. | |||

| 404 Martyrdom of Telemachus ends gladiatorial shows. | |||

| 405-406 German band under Radagaesus invades Italy but is defeated at Faesula | |||

| 406/407 Alans, Sueves and Vandals invade Gaul | |||

| 407 Revolt of Constantine III who withdraws the troops from Britain to set up a Gallic empire | |||

| 408 Honorius puts Stilicho to death | |||

| Theodosius II (aged 7) succeeds Arcadius. | |||

| Alaric invades Italy and puts rome to ransom | |||

| 409 Alaric proclaims Attalus emperor. | |||

| 410 Fall of Attalus. Alaric sacks Rome but dies. | |||

| 411 Athaulf succeeds Alaric as King of the Visigoths. | |||

| Constantine III crushed by Constantius | |||

| 412 Athaulf withdraws from Italy to Narbonne | |||

| 413 Revolt and collapse of Heraclius | |||

| 414 Athaulf attacks the barbarians in Spain Pulcheria regent for her brother Theodosius II | |||

| 415 Wallia succeeds Athaulf | |||

| 416 Constantius the patrician marries Placidia | |||

| 417 Visigoths establish themselves in Aquitania | |||

| 420 Ostrogoths settled in Pannonia 425 Honorius dies. Valentinian III emperor. Placidia regent. | |||

| 427 Revolt of Boniface in Africa | |||

| 429 The Vandals, invited by Boniface, migrate under Geiseric from Spain to Africa, which they proceed to conquer. | |||

| 433 Aetius patrician in Italy | |||

| 434 Rugila king of the Huns dies; Attila succeds. | |||

| 439 Geiseric takes Carthage. Vandal fleet dominant. | |||

| 440 Geiseric invades Sicily, but is bought off. | |||

| 441 Attila crosses Danube and invades Thrace | |||

| 443 Attila makes terms with Theodosius II. Burgundians settled in Gaul. | |||

| 447 Attila's second invasion | |||

| 449 Attila's second peace. | |||

| 450 Marcian succeeds Theodosius II. Marcian stops Hun tribute. | |||

| 451 Attila invades Gaul. Attila heavily defeated by Aetius and Theodoric I the Visigoth at Châlons | |||

| 452 Attila invades Italy but spares Rome and retires | |||

| 453 Attila dies. Theodoric II King of the Visigoths | |||

| 454 Overthrow of the Hun power by the subjected barbarians at the Battle of Netad. | |||

| Murder of Aetius by Valentinian III | |||

| 455 Murder of Valentinian III and death of Maximus, his murderer. Geiseric sacks Rome, carrying of Eudoxia. Avitus proclaimed emperor of the Visigoths | |||

| 456 Domination of both east and west by the masters of the soldiers, Aspar the Alan and Ricimer the Sueve. | |||

| 457 Ricimer deposes Avitus and makes Majorian emperor. Marcian dies. Aspar makes Leo emperor. | |||

| 460 Destruction of Majorian's fleet off Cartagena. | |||

| 461 Deposition and death of Majorian. Libius Severus emperor. | |||

| 465 Libius Severus dies. Ricimer rules as patrician. Fall of Aspar. | |||

| 466 Euric, King of the Visigoths, begins conquest of Spain. | |||

| 467 Leo appoints Anthemius western emperor | |||

| 468 Leo sends great expedition under Basiliscus to crush Geiseric, who destroys it. | |||

| 472 Ricimer deposes Anthemius and set up Olybrius. Death of Ricimer and Olybrius. | |||

| 473 Glycerius western emperor | |||

| 474 Julius Nepos western emperor. Leo dies and is succeeded by his infant grandson Leo II. Leo II dies and is succeeded by Zeno the Isaurian | |||

| 475 Romulus Augustus last western emperor. | |||

| Usurpation of Basiliscus at Constantinople. Zeno escapes to Asia. Theodoric the Amal becomes King of the Ostrogoths | |||

| 476 Odoacer the Scirian, commander and elected King of the German troops in Italy, deposes Romulus Augustus and resolves to rule independently, but nominally as the viceroy of the Roman Augustus of Constantinople. | |||

| End of the western empire. | |||

| The end of the Western Roman Empire traditionally has been seen by historians to mark the end of the ] and beginning of the ]. More recent schools of history, such as ], offer a more nuanced view from the traditional historical narrative. | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 14:34, 9 May 2007

This article is about the historiography of the decline of the Roman Empire. For a description of events see Roman Empire. For the book see The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. For the movie see The Fall of the Roman Empire (film).

The Decline of the Roman Empire, also called the Fall of the Roman Empire, or the Fall of Rome, is a historical term of periodization for the end of the Western Roman Empire. Edward Gibbon in his famous study The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776) was the first to use this terminology, but he was neither the first nor the last to speculate on why and when the Empire collapsed. It remains one of the greatest historical questions, and has a tradition rich in scholarly interest. In 1984, German professor Alexander Demandt published a collection of 210 theories on why Rome fell.

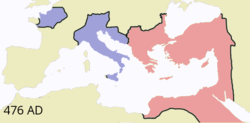

The traditional date of the fall of the Roman Empire is September 4, 476 when Romulus Augustus, the de jure Emperor of the Western Roman Empire was deposed by Odoacer. Many historians question this date, noting that the Eastern Roman Empire continued until the Fall of Constantinople in 29 May 1453. Some other notable dates are the death of Theodosius I in 395 (the last time the Roman Empire was politically unified), the crossing of the Rhine in 406 by Germanic tribes after the withdrawal of the legions in order to defend Italy against Alaric I, and the death of Stilicho in 408, followed by the disintegration of the western legions. Many scholars maintain that rather than a "fall", the changes can more accurately be described as a complex transformation. Over time many theories have been proposed on why the Empire fell, or whether indeed it fell at all.

Theories about the decline and fall of the Roman Empire

There were many reasons for the fall of the Roman Empire. Each one intertwined with the next. Many even blame the introduction of Christianity for the decline. Christianity made many Roman citizens into pacifists, making it more difficult to defend against the barbarian attackers. Also money used to build churches could have been used to maintain the empire. Although some argue that Christianity may have provided some morals and values for a declining civilization and therefore may have actually prolonged the imperial era. Decline in Morals and Values

Those morals and values that kept together the Roman legions and thus the empire could not be maintained towards the end of the empire. Crimes of violence made the streets of the larger cities unsafe. Even during PaxRomana there were 32,000 prostitutes in Rome. Emperors like Nero and Caligula became infamous for wasting money on lavish parties where guests ate and drank until they became ill. The most popular amusement was watching the gladiatorial combats in the Colosseum. These were attended by the poor, the rich, and frequently the emperor himself. As gladiators fought, vicious cries and curses were heard from the audience. One contest after another was staged in the course of a single day. Should the ground become too soaked with blood, it was covered over with a fresh layer of sand and the performance went on.

Public Health

There were many public health and environmental problems. Many of the wealthy had water brought to their homes through lead pipes. Previously the aqueducts had even purified the water but at the end lead pipes were thought to be preferable. The wealthy death rate was very high. The continuous interaction of people at the Colosseum, the blood and death probable spread disease. Those who lived on the streets in continuous contact allowed for an uninterrupted strain of disease much like the homeless in the poorer run shelters of today. Alcohol use increased as well adding to the incompetency of the general public.

Political Corruption

One of the most difficult problems was choosing a new emperor. Unlike Greece where transition may not have been smooth but was at least consistent, the Romans never created an effective system to determine how new emperors would be selected. The choice was always open to debate between the old emperor, the Senate, the Praetorian Guard (the emperor's's private army), and the army. Gradually, the Praetorian Guard gained complete authority to choose the new emperor, who rewarded the guard who then became more influential, perpetuating the cycle. Then in 186 A. D. the army strangled the new emperor, the practice began of selling the throne to the highest bidder. During the next 100 years, Rome had 37 different emperors - 25 of whom were removed from office by assassination. This contributed to the overall weaknesses of the empire.

Unemployment

During the latter years of the empire farming was done on large estates called latifundia that were owned by wealthy men who used slave labor. A farmer who had to pay workmen could not produce goods as cheaply. Many farmers could not compete with these low prices and lost or sold their farms. This not only undermined the citizen farmer who passed his values to his family, but also filled the cities with unemployed people. At one time, the emperor was importing grain to feed more than 100,000 people in Rome alone. These people were not only a burden but also had little to do but cause trouble and contribute to an ever increasing crime rate.

Inflation

The roman economy suffered from inflation (an increase in prices) beginning after the reign of Marcus Aurelius. Once the Romans stopped conquering new lands, the flow of gold into the Roman economy decreased. Yet much gold was being spent by the romans to pay for luxury items. This meant that there was less gold to use in coins. As the amount of gold used in coins decreased, the coins became less valuable. To make up for this loss in value, merchants raised the prices on the goods they sold. Many people stopped using coins and began to barter to get what they needed. Eventually, salaries had to be paid in food and clothing, and taxes were collected in fruits and vegetables.

Urban decay

Wealthy Romans lived in a domus, or house, with marble walls, floors with intricate colored tiles, and windows made of small panes of glass. Most Romans, however, were not rich, They lived in small smelly rooms in apartment houses with six or more stories called islands. Each island covered an entire block. At one time there were 44,000 apartment houses within the city walls of Rome. First-floor apartments were not occupied by the poor since these living quarters rented for about $00 a year. The more shaky wooden stairs a family had to climb, the cheaper the rent became. The upper apartments that the poor rented for $40 a year were hot, dirty, crowed, and dangerous. Anyone who could not pay the rent was forced to move out and live on the crime-infested streets. Because of this cities began to decay.

Inferior Technology

During the last 400 years of the empire, the scientific achievements of the Romans were limited almost entirely to engineering and the organization of public services. They built marvelous roads, bridges, and aqueducts. They established the first system of medicine for the benefit of the poor. But since the Romans relied so much on human and animal labor, they failed to invent many new machines or find new technology to produce goods more efficiently. They could not provide enough goods for their growing population. They were no longer conquering other civilizations and adapting their technology, they were actually losing territory they could not longer maintain with their legions.

Military Spending

Maintaining an army to defend the border of the Empire from barbarian attacks was a constant drain on the government. Military spending left few resources for other vital activities, such as providing public housing and maintaining quality roads and aqueducts. Frustrated Romans lost their desire to defend the Empire. The empire had to begin hiring soldiers recruited from the unemployed city mobs or worse from foreign counties. Such an army was not only unreliable, but very expensive. The emperors were forced to raise taxes frequently which in turn led again to increased inflation.

THE FINAL BLOWS!!!

For years, the well-disciplined Roman army held the barbarians of Germany back. Then in the third century A. D. the Roman soldiers were pulled back from the Rhine-Danube frontier to fight civil war in Italy. This left the Roman border open to attack. Gradually Germanic hunters and herders from the north began to overtake Roman lands in Greece and Gaul (later France). Then in 476 A. D. the Germanic general Odacer or Odovacar overthrew the last of the Roman Emperors, Augustulus Romulus. From then on the western part of the Empire was ruled by Germanic chieftain. Roads and bridges were left in disrepair and fields left untilled. Pirates and bandits made travel unsafe. Cities could not be maintained without goods from the farms, trade and business began to disappear. And Rome was no more in the West.

Environmental degradation

Another theory is that gradual environmental degradation caused population and economic decline. Deforestation and excessive grazing led to erosion of meadows and cropland. Increased irrigation caused salinization. These human activities resulting in fertile land becoming nonproductive and eventually increased desertification in some regions. Many animal species become extinct. See also Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed.

Late Antiquity

Historians of Late Antiquity, a field pioneered by Peter Brown, have turned away from the idea that the Roman Empire "fell" refocusing on Pirenne's thesis. They see a "transformation" occurring over centuries, with the roots of Medieval culture contained in Roman culture and focus on the continuities between the classical and Medieval worlds. Thus, it was a gradual process with no clear break.

Historiography

Historiographically, the primary issue historians have looked at when analyzing any theory is the continued existence of the Eastern Empire or Byzantine Empire, which lasted for about a thousand years after the fall of the West. For example, Gibbon implicates Christianity in the fall of the Western Empire, yet the eastern half of the Empire, which was even more Christian than the west in geographic extent, fervor, penetration and sheer numbers continued on for a thousand years afterwards (although Gibbon did not consider the Eastern Empire to be much of a success). As another example, environmental or weather changes impacted the east as much as the west, yet the east did not "fall."

Theories will sometimes reflect the particular concerns that historians might have on cultural, political, or economic trends in their own times. Gibbon's criticism of Christianity reflects the values of the Enlightenment; his ideas on the decline in martial vigor could have been interpreted by some as a warning to the growing British Empire. In the 19th century socialist and anti-socialist theorists tended to blame decadence and other political problems. More recently, environmental concerns have become popular, with deforestation and soil erosion proposed as major factors, and destabilizing population decreases due to epidemics such as early cases of bubonic plague and malaria also cited. Global climate changes of 535-536 caused by the eruption of Krakatoa in 535, as mentioned by David Keys and others, is another example. Ideas about transformation with no distinct fall mirror the rise of the postmodern tradition, which rejects periodization concepts (see metanarrative). What is not new are attempts to diagnose Rome's particular problems, with Satire X, written by Juvenal in the early 2nd century at the height of Roman power, criticizing the peoples' obsession with "bread and circuses" and rulers seeking only to gratify these obsessions.

One of the primary reasons for the sheer number of theories is the notable lack of surviving evidence from the 4th and 5th centuries. For example there are so few records of an economic nature it is difficult to arrive at even a generalization of the economic conditions. Thus, historians must quickly depart from available evidence and comment based on how things ought to have worked, or based on evidence from previous and later periods, on inductive reasoning. As in any field where available evidence is sparse, the historian's ability to imagine the 4th and 5th centuries will play as important a part in shaping our understanding as the available evidence, and thus be open for endless interpretation.

The end of the Western Roman Empire traditionally has been seen by historians to mark the end of the Ancient Era and beginning of the Middle Ages. More recent schools of history, such as Late Antiquity, offer a more nuanced view from the traditional historical narrative.

'The Collapse' Chronology

337 May 22, death of Constantine the Great

337 Division of the empire between Constantine's three sons: Constantine II (west), Constans (middle), Constantius (east). Execution of all other princes of royal blood, but for the children Gallus and Julian.

338 Constantius attends to the war against Persia. First unsuccessful siege of Nisibis by Sapor II

340 Constans and Constantine II at war. Battle of Aquileia; death of Constantine II.

344 Persian victory at Singara

346 Second unsuccessful siege of Nisibis by Sapor II

350 Third siege of Nisibis. Owing to incursions of the Massagetae in Transoxiana, Sapor II makes truce with Constantius. Magnentius murders Constans and becomes emperor in the west. Vetranio proclaimed emperor on the Danube frontier. On appearance of Constantius, Vetranio resumes allegiance.

351 Magnetnius defeated at the very bloody Battle of Mursa. Misrule by Gallus, left as Caesar in the east.

352 Italy recovered. Magnentius in Gaul.

353 Final defeat and death of Magnentius

354 Execution of Gallus. Julian at Athens

356 Julian dispatched as Caesar to Gaul. War with teh Alemanni, Quadi and Sarmatians. Military achievements by Julian.

357 Challenge by Sapor II

359 Sapor II invades Mesopotamia. Constantius goes to the east.

360 The Gallic army forces Julian to revolt. Julian marches down the Danube to Moesia.

361 Constantius dies. Julian the Apostate emperor.

362 Christians forbidden to teach. Julian's advance against Persians

363 Disaster and death of Julian. Retreat of the army which proclaims Jovian emperor. Humiliating peace with Persia. Renewed toleration decree.

364 Jovian nominates Valentinian and dies. Valentinian associates his brother Valens as eastern emperor and takes the west for himself. Permanent duality of the empire inaugurated.

366 Damasus pope. Social and political influences become a feature of papal elections.

367 Valentinian sends his son Gratian as Augustus to Gaul. Theodosius the elder in Britain.

368 War of Valens with Goths

369 Peace with Goths

369-377 Subjugation of Ostrogoths by Hun invasion

374 Pannonian War of Valentinian. Ambrose Bishop of Milan

375 Death of Valentinian. Accession of Gratian, who associates his infant brother Valentinian II at Milan. Gratian first emperor to refuse the office of Pontifex Maximus. Theodosius the elder in Africa.

376 Execution of elder and retirement of younger Theodosius.

377 Valens receives and settles Visigoths in Moesia.

378 Gratian defeats Alemanni. Rising of Visigoths. Valens killed at disaster at Adrianople.

380 Gratian nominates the younger Theodosius as successor to Valens.

382 Treaty of Theodosius with Visigoths

383 Revolt of Maximus in Britain. Flight and death of Gratian. Theodosius recognizes Maximus in the west and Valentinian II at Milan.

386 Revolt of Gildo in Africa

387 Theodosius crushes Maximus, makes Arbogast the Frank master of the soldiers to Valentinian II

392 Murder of Valentinian II. Arbogast sets up Eugenius.

394 Fall of Arbogast and Eugenius. Theodosius makes his younger son Honorius western Augustus, with the Vandal Stilicho master of the soldiers.

395 Theodosius dies. Arcadius and Honorius emperors.

396 Alaric the Visigoth overruns Balkan peninsula.

397 Alaric checked by Stilicho, is given Illyria.

398 Suppression of Gildo in Afrca

402 Alaric invades Italy, checked by Stilicho

403 Alaric retires after defeat at Pollentia. Ravenna becomes imperial headquarters.

404 Martyrdom of Telemachus ends gladiatorial shows.

405-406 German band under Radagaesus invades Italy but is defeated at Faesula

406/407 Alans, Sueves and Vandals invade Gaul

407 Revolt of Constantine III who withdraws the troops from Britain to set up a Gallic empire

408 Honorius puts Stilicho to death Theodosius II (aged 7) succeeds Arcadius. Alaric invades Italy and puts rome to ransom

409 Alaric proclaims Attalus emperor.

410 Fall of Attalus. Alaric sacks Rome but dies.

411 Athaulf succeeds Alaric as King of the Visigoths. Constantine III crushed by Constantius

412 Athaulf withdraws from Italy to Narbonne

413 Revolt and collapse of Heraclius

414 Athaulf attacks the barbarians in Spain Pulcheria regent for her brother Theodosius II

415 Wallia succeeds Athaulf

416 Constantius the patrician marries Placidia

417 Visigoths establish themselves in Aquitania

420 Ostrogoths settled in Pannonia 425 Honorius dies. Valentinian III emperor. Placidia regent.

427 Revolt of Boniface in Africa

429 The Vandals, invited by Boniface, migrate under Geiseric from Spain to Africa, which they proceed to conquer.

433 Aetius patrician in Italy

434 Rugila king of the Huns dies; Attila succeds.

439 Geiseric takes Carthage. Vandal fleet dominant.

440 Geiseric invades Sicily, but is bought off.

441 Attila crosses Danube and invades Thrace

443 Attila makes terms with Theodosius II. Burgundians settled in Gaul.

447 Attila's second invasion

449 Attila's second peace.

450 Marcian succeeds Theodosius II. Marcian stops Hun tribute.

451 Attila invades Gaul. Attila heavily defeated by Aetius and Theodoric I the Visigoth at Châlons

452 Attila invades Italy but spares Rome and retires

453 Attila dies. Theodoric II King of the Visigoths

454 Overthrow of the Hun power by the subjected barbarians at the Battle of Netad. Murder of Aetius by Valentinian III

455 Murder of Valentinian III and death of Maximus, his murderer. Geiseric sacks Rome, carrying of Eudoxia. Avitus proclaimed emperor of the Visigoths

456 Domination of both east and west by the masters of the soldiers, Aspar the Alan and Ricimer the Sueve.

457 Ricimer deposes Avitus and makes Majorian emperor. Marcian dies. Aspar makes Leo emperor.

460 Destruction of Majorian's fleet off Cartagena.

461 Deposition and death of Majorian. Libius Severus emperor.

465 Libius Severus dies. Ricimer rules as patrician. Fall of Aspar.

466 Euric, King of the Visigoths, begins conquest of Spain.

467 Leo appoints Anthemius western emperor

468 Leo sends great expedition under Basiliscus to crush Geiseric, who destroys it.

472 Ricimer deposes Anthemius and set up Olybrius. Death of Ricimer and Olybrius.

473 Glycerius western emperor

474 Julius Nepos western emperor. Leo dies and is succeeded by his infant grandson Leo II. Leo II dies and is succeeded by Zeno the Isaurian

475 Romulus Augustus last western emperor. Usurpation of Basiliscus at Constantinople. Zeno escapes to Asia. Theodoric the Amal becomes King of the Ostrogoths

476 Odoacer the Scirian, commander and elected King of the German troops in Italy, deposes Romulus Augustus and resolves to rule independently, but nominally as the viceroy of the Roman Augustus of Constantinople. End of the western empire.

See also

Notes

- Alexander Demandt: 210 Theories, from Crooked Timber weblog entry August 25 2003. Retrieved June 2005.

- Hunt, Lynn (2001). The Making of the West, Peoples and Cultures, Volume A: To 1500. Bedford / St. Martins. p. 256. ISBN 0-312-18365-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - http://www.humecol.lu.se/woshglec/papers/hughes.doc

References

- Alexander Demandt (1984). Der Fall Roms: Die Auflösung des römischen Reiches im Urteil der Nachwelt. ISBN 3-406-09598-4

- Edward Gibbon. "General Observations on the Fall of the Roman Empire in the West", from the Internet Medieval Sourcebook. Brief excerpts of Gibbon's theories.

- William Carroll Bark (1958). Origins of the Medieval World. ISBN 0-8047-0514-3

Further reading

- Peter Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire, 2005, ISBN 0-19-515954-3, offers a narrative of the final years, in the tradition of Gibson or Bury, plus incorporates latest archaeological evidence and other recent findings.

- Donald Kagan, The End of the Roman Empire: Decline or Transformation?, ISBN 0-669-21520-1 (3rd edition 1992) - a survey of theories.

- Arthur Ferrill The Fall of the Roman Empire: The Military Explanation" 0500274959 (1998) supports Vegetius' theory.

- "The Fall of Rome - an author dialogue", Oxford professors Bryan Ward-Perkins and Heather discuss The Fall of Rome: And the End of Civilization and The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians.

- Fall of Rome - Decline of the Roman Empire - Lists many possible causes with references

- The Ancient Suicide of the West - A libertarian theory about the decline and fall of Rome.

- Lucien Musset, Les Invasions : Les vagues germaniques, Presses Universitaires de France, Paris, 1965 (3rd ed. 1994, ISBN 2130467156)