| Revision as of 12:37, 13 June 2007 view sourceDbachmann (talk | contribs)227,714 edits Alemannic is part of High German← Previous edit | Revision as of 12:48, 13 June 2007 view source Rex Germanus (talk | contribs)11,278 edits →History of the term: does it? So germanus means of the people?Next edit → | ||

| Line 80: | Line 80: | ||

| ==History of the term== | ==History of the term== | ||

| ] in 1512]] | ] in 1512]] | ||

| The English term as used today translates German ''Deutsch''. It is derived from Latin '']'' and has used since the 16th century synonymously with "Teuton", after ''teutonicus'' used in Latin since the 9th century to refer to the German language, from the name of the ]. Before the 16th century, the terms used in English were ''Almain'', from the name of the ], or ''Dutch'', an imitation of both ] "'']''" (meaning "]") and the ] cognate "''deutsch''" (meaning: "German"). The diffuse nature of the term mirrors the heterogeneous nature of the ], from the 16th century also known as "Holy Roman Empire of the German nation". The linguistic affiliation of the ] itself was hotly debated at the time, and English academia was split into "]s" who preferred to include English as one of the "Germanic" or "Teutonic" languages, and "]s" who preferred to classify English as "Scandinavian" (now known as ])<ref>English is today classified as West Germanic, although as within a separate ] subgroup.</ref>. | The English term as used today translates German ''Deutsch''{{fact}}. It is derived from Latin '']'' and has used since the 16th century synonymously with "Teuton", after ''teutonicus'' used in Latin since the 9th century to refer to the German language, from the name of the ]. Before the 16th century, the terms used in English were ''Almain'', from the name of the ], or ''Dutch'', an imitation of both ] "'']''" (meaning "]") and the ] cognate "''deutsch''" (meaning: "German"). The diffuse nature of the term mirrors the heterogeneous nature of the ], from the 16th century also known as "Holy Roman Empire of the German nation". The linguistic affiliation of the ] itself was hotly debated at the time, and English academia was split into "]s" who preferred to include English as one of the "Germanic" or "Teutonic" languages, and "]s" who preferred to classify English as "Scandinavian" (now known as ])<ref>English is today classified as West Germanic, although as within a separate ] subgroup.</ref>. | ||

| With the rise of the ] as a threat to British interests in ], the "Germanophile" position came out of fashion and British romanticism turned to Scandinavia (see ]). "German" from this period refers to the German Empire, already to the exclusion of ], the ] and ]. Usage of ''Dutch'' was narrowed to refer to the Netherlands exclusively during the early 16th century. | With the rise of the ] as a threat to British interests in ], the "Germanophile" position came out of fashion and British romanticism turned to Scandinavia (see ]). "German" from this period refers to the German Empire, already to the exclusion of ], the ] and ]. Usage of ''Dutch'' was narrowed to refer to the Netherlands exclusively during the early 16th century. | ||

Revision as of 12:48, 13 June 2007

- In a context of antiquity (pre AD 500), "Germans" is used in the sense of Germanic tribes.

(left to right): Mozart • Goethe • Bismarck • Kepler• | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 80 - 160 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 60 million | |

| 12 million | |

| 3 million | |

| 1,200,000 | |

| The | 1 million |

| 742,212 | |

| 386,200 | |

| 208,349 | |

| 180-250,000 | |

| 150,000 - 200,000 | |

| 160,000 | |

| 150,000 | |

| 112,000 (4.6 million including Alemannic Swiss) | |

| 110,000 | |

| 74,000 (7.9 million including Austrians, if Austrians are regarded as Germans) | |

| 15-20,000 (border region) | |

| Languages | |

| German: High German (Upper German, Central German), Low German (see German dialects) | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholic, Protestant (chiefly Lutheran), secular, others | |

Germans (Template:Lang-de) are defined as an ethnic group, in the sense of sharing a common German culture, speaking the German language as a mother tongue and being of German descent. Germans are also defined by their national citizenship, which had, in the course of German history, varying relations to the above (German culture), according to the influence of subcultures and society in general (also refer to Imperial Germans, Federal Germans etc. and Demographics of Germany).

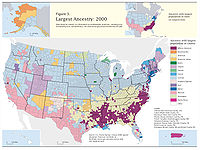

While there are approximately 100 million native German speakers in the world, about 75 million consider themselves Germans. There are an additional 70 million people of German ancestry (mainly in the USA, Brazil, Argentina, Kazakhstan and Canada) who are not native speakers of German and who may still consider themselves ethnic Germans, so that the total number of Germans worldwide lies between 75 and 160 million, according to the criteria applied (native speakers, single-ancestry ethnic Germans or partial German ancestry). In the USA, 15.2% of citizens identify as of German American according to the United States Census of 2000, more than any other group.

History of the term

The English term as used today translates German Deutsch. It is derived from Latin Germanus and has used since the 16th century synonymously with "Teuton", after teutonicus used in Latin since the 9th century to refer to the German language, from the name of the Teutones. Before the 16th century, the terms used in English were Almain, from the name of the Alemanni, or Dutch, an imitation of both Dutch "diets" (meaning "Dutch") and the German cognate "deutsch" (meaning: "German"). The diffuse nature of the term mirrors the heterogeneous nature of the Holy Roman Empire, from the 16th century also known as "Holy Roman Empire of the German nation". The linguistic affiliation of the English language itself was hotly debated at the time, and English academia was split into "Germanophiles" who preferred to include English as one of the "Germanic" or "Teutonic" languages, and "Scandophiles" who preferred to classify English as "Scandinavian" (now known as North Germanic). With the rise of the German Empire as a threat to British interests in Hamburg, the "Germanophile" position came out of fashion and British romanticism turned to Scandinavia (see Viking revival). "German" from this period refers to the German Empire, already to the exclusion of Austria, the Netherlands and Switzerland. Usage of Dutch was narrowed to refer to the Netherlands exclusively during the early 16th century.

Ethnic Germans

The term Ethnic Germans may be used in several ways. It may serve to distinguish Germans from those who may have citizenship in the German state but are not Germans; or it may indicate Germans living as minorities in other nations. In English usage, but less often in German, Ethnic Germans may be used for assimilated descendants of German emigrants.

Ethnic Germans form an important minority group in several countries in central and eastern Europe (Poland, Hungary, Romania, Russia) as well as in Namibia, southern Brazil (German-Brazilian), Peru, Argentina and Chile.

Some groups may be noted as Ethnic Germans despite no longer having German as their mother tongue or belonging to a distinct German culture. Until the 1990s, two million Ethnic Germans lived throughout the former Soviet Union, especially in Russia and Kazakhstan.

In the United States 1990 census, 57 million people are fully or partly of German ancestry, forming the largest single ethnic group in the country. Most Americans of German descent live in the Mid-Atlantic states (especially Pennsylvania) and the northern Midwest (especially in Iowa, Minnesota, Ohio, Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, North Dakota, South Dakota, and eastern Missouri), but historically Germanic immigrant enclaves can be found in many other states (e.g., the German Texans).

Notable Ethnic German populations also exist in other Anglosphere countries such as Canada (approx. 9% of the population) and Australia (approx. 4% of the population).

History

Origins

Main article: Germanic peoplesThe Germans are a Germanic people which as an ethnicity emerged in southern Scandinavia in the centuries leading up to the Migrations Period, where they were in contact with other peoples, including Finnic inhabitants of Scandinavia to the north, Balto-Slavic peoples to the east and Celts to the south. Later in history, Germanic peoples — as most other European people — mixed with bordering ethnic groups such as Gallo-Romans and Slavs. For the global genetic make-up of the Germans and other peoples, see also the Template:PDFlink and the National Geographic Genographic Atlas

In the course of the Migration Period, Slavs expanded westwards at the same time as Germans expanded eastwards. The result was German colonization as far East as Romania, and Slavic colonization as far west as present-day Lübeck (at the Baltic Sea), Hamburg (connected to the North Sea), and along the river Elbe and its tributary Saale further South.

Middle Ages

A "German" as opposed to generically "Germanic" ethnicity emerges in the course of the Middle Ages, under the influence of the unity of Eastern Francia from the 9th century. The process is gradual and lacks any clear definition.

After Christianization, the superior organization of the Roman Catholic Church lent the upper hand for a German expansion at the expense of the Slavs, giving the medieval Drang nach Osten as a result. At the same time, naval innovations led to a German domination of trade in the Baltic Sea and Central–Eastern Europe through the Hanseatic League. Along the trade routes, Hanseatic trade stations became centers of Germanness where German urban law (Stadtrecht) was promoted by the presence of large, relatively wealthy German populations and their influence on the worldly powers.

This means that people whom we today often consider "Germans", with a common culture and worldview very different from that of the surrounding rural peoples, colonized as far north of present-day Germany as Bergen (in Norway), Stockholm (in Sweden), and Vyborg (now in Russia). At the same time, it is important to note that the Hanseatic League was not exclusively German in any ethnic sense. Many towns who joined the league were outside of the Holy Roman Empire, which wasn't by far entirely German itself, and some of them ought not at all be characterized as German.

It is only in the late 15th century that the German empire comes to be called Holy Roman Empire of the German nation, and even this was not in any way exclusively German, notably including a sizeable Slavic minority. The Thirty Years' War confirmed the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, and the Napoleonic Wars gave it its coup de grâce.

The Divided Germany

The idea that Germany is a divided nation is not new and not peculiar. Foreign powers had long interceded in German affairs, pitting one German principality against the other. Since the Peace of Westphalia, Germany has been "one nation split in many countries". The Austrian–Prussian split, confirmed when Austria remained outside of the 1871 created Imperial Germany, was only the most prominent example. The initial unification of Germany came as a great shock to these foreign powers, who had been trying to undo Germany as a national entity for many years. Most recently, the division between East Germany and West Germany kept the idea alive.

The beginnings of the divided Germany may be traced back much further; to a Roman occupied Germania in the west and to Free Germania in the east. Starkly different ideologies have many times been developed due to conquerors and occupiers of sections of Germany. Poets talked of Zwei Seelen in einem Herz (Two souls in one heart, drinking good german beer).

In the 19th century, after the Napoleonic Wars and the fall of the Holy Roman Empire (of the German nation), Austria and Prussia would emerge as two opposite poles in Germany, trying to re-establish the divided German nation. In 1870, Prussia attracted even Bavaria in the Franco-Prussian War and the creation of the German Empire as a German nation-state, effectively excluding the multi-ethnic Austrian Habsburg monarchy.

The dissolution of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire after World War I led to a strong desire of the population of the new Republic of Austria to be integrated into Germany. This was, however, prevented by the Treaty of Versailles.

Trying to overcome the shortfall of Chancellor Bismarck's creation, the Nazis attempted to unite "all Germans" in one realm. This was welcomed among ethnic Germans in Czechoslovakia, Austria, Poland, Danzig and Western Lithuania, but met resistance among the Swiss and the Dutch, who mostly were perfectly content with their perception of separate nations established in 1648. The Dutch, in particular, had never even spoken a form of the German language.

Before World War II, most Austrians considered themselves German and denied the existence of a distinct Austrian ethnic identity. It was only after the defeat of Nazi Germany in World War II that this began to change. After the War, the Austrians increasingly saw themselves as a nation distinct from the other German-speaking areas of Europe; today, some polls have indicated that no more than 10% of the German-speaking Austrians see themselves as part of a larger German nation linked by blood or language.

Ethnic nationalism

Main article: Völkisch movementThe reaction evoked in the decades after the Napoleonic Wars was a strong ethnic nationalism that emphasized, and sometimes overemphasized, the cultural bond between Germans. Later alloyed with the high standing and world-wide influence of German science at the end of the 19th century, and to some degree enhanced by Bismarck's military successes and the following 40 years of almost perpetual economic boom (the Gründerzeit), it gave the Germans an impression of cultural supremacy, particularly compared to the Slavs.

Religion

The Protestant Reformation started in the German cultural sphere, when in 1517, Martin Luther posted his 95 Theses to the door of the Schlosskirche ("castle church") in Wittenberg. Today, the German identity includes both Protestants and Catholics. The groups are about equally represented in Germany, contrary to the belief that it is mostly Protestant. Among Protestant denominations, the Lutherans are well represented by the Germans, while Calvinists are historically only to be found near the Dutch border and in a few cities like Worms and Speyer. The late 19th century saw a strong movement among the Jewry in Germany and Austria to assimilate and define themselves as à priori Germans, i.e. as Germans of Jewish faith (a similar movement occurred in Hungary). In conservative circles, this was not always embraced, and, for the Nazis, it was unacceptable. The Nazi rule led to the expulsion of almost all of the relatively small number of domestic Jews. Today Germany attempts to successfully integrate the Gastarbeiter and later arrived refugees from ex-Yugoslavia, who often are Muslims.

Minorities

In recent years, the German-speaking countries of Europe have been confronted with demographic changes due to decades of immigration. These changes have led to renewed debates (especially in the Federal Republic of Germany) about who should be considered German. Non-ethnic Germans now make up more than 8% of the German population, mostly the descendants of guest workers who arrived in the 1960s and 1970s. Turks, Italians, Greeks, and people from the Balkans in southeast Europe form the largest single groups of non-ethnic Germans in the country.

In addition, a significant number of German citizens (close to 5%), although traditionally considered ethnic Germans, are in fact foreign-born and thus often retain the cultural identities and languages or their native countries in addition to being Germans, a fact that sets them apart from those born and raised in Germany. Of course, the idea of foreign-born repatriates is not unique to Germany. The English and British equivalent legal term is lex sanguinis, which is exactly the same principle- that citizenship is inherited by the child from his/her parents. It has nothing to do with ethnicity.

Ethnic German repatriates from the former Soviet Union are a separate case and constitute by far the largest such group and the second largest ethno-national minority group in Germany. The repatriation provisions made for ethnic Germans in Eastern Europe are unique and have historical basis, since these were areas where Germans traditionally lived. A controversial example of repatriation involves the Volga Germans, descendents of ethnic Germans who settled in Russia during the 18th century, who have been able to claim German citizenship even though neither they nor their ancestors for several generations have ever been to Germany. In contrast, persons of German descent in North America, South America, Africa, etc. do not have an automatic right of return and must actually prove their eligibility for German citizenship according to the clauses pertaining to the German nationality law. Other countries with post-Soviet Union repatriation programs include Greece, Israel and South Korea.

Unlike these ethnic German repatriates, some non-German ethnic minorities in the country, including some who were born and raised in the Federal Republic, choose to remain non-citizens. Although citizenship laws have been recently relaxed to allow such individuals to become nationalized citizens, many choose not to give up allegiance to the countries of their ethnic roots and continue to live in Germany under an ambiguous status of an alien resident or a guest worker, especially since this status, though lacking certain political rights, often does not impede one's ability to work, get free public higher education and travel abroad.

As a result, close to 10 million people permanently living in the Federal Republic today distinctly differ from the majority of the population in a variety of ways such as race, ethnicity, religion, language and culture, yet often fail to be recognized as minorities in official statistical sources due to the fact that such sources traditionally survey only German citizens, and under the so called jus sanguinis system, that has been in effect in Germany since the 19th century, and has only recently been partially replaced by the alternative jus soli system. This situation contributes to the invisibility of Germany's minorities making Germany technically one of the most ethnically homogeneous nation in the world, whereas in all practicality the Federal Republic is today one of the most ethnically diverse countries in Europe.

Historical persons and institutions

There is a lack of international consensus in regard to the characterization of certain historical persons and institutions, like for instance Kafka, Copernicus or the Hanseatic League. Many, particularly Germans, but also others, would hold that they belong to the German culture, which is what decides if someone is considered a German or not. On the other hand, e.g. Poles, Austrians and others often prefer to see certain persons as Polish, or Austrian. Many people all over Europe see them quite simply as European. Particularly, Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven - who spent most of their lives in what is Austria today - may be considered to have been central within the German culture but may nevertheless, sometimes often be characterized as Austrians, but not as Germans. Many people also consider them Austrian and German at once, like e.g. the U.S. State Departement does on its report on current Austria, describing it as inhabited by Austrian nationals of which 98% are ethnic Germans.

See also

- Germany

- List of Germans

- List of Austrians

- List of Swiss people

- List of Alsatians and Lorrainians

- Germans of Romania

- Germans of Paraguay

- Germans of Poland

- German Americans

- German-Brazilians

- German-Chilean

- German Mexicans

- German settlement in Argentina

- German Namibians

- German-Canadians

- British Germans

- German Australians

- German-Briton

- Organised persecution of ethnic Germans

- Names of the German people and language in other languages

- German idealism

- Austrians

- List of famous German Americans

- German Americans

External links

References

- 73 million is the minimal estimate, counting 68 million ethnic Germans, plus some 5-10 million primary ancestry, German-speaking ethnic Germans worldwide. 160 is the maximal estimate, counting all people claiming ethnic German ancestry in the USA, Brazil and elsewhere.

- According to the United States Census, 2000 , there are some 45 million US citizens claiming German ancestry, including Swiss, Alsatian, Austrian and Transylvania Germans, and 2.95% (c. 8 million) of the US population speak German natively. See also German Americans, Languages in the United States#German.

- The

] reports 6 millions Brazilians with German "single-ancestry" and 12 million with partly German ancestry. See German-Brazilian - 2001 Canadian Census gives 2,742,765 total respondents stating their ethnic origin as partly German, with 705,600 stating "single-ancestry", see List of Canadians by ethnicity.

- According to the Asociación Argentina de Descendientes de Alemanes del Volga there are more than 1,200,000 descendants of Volga Germans in Argentina (figures do not include other German communities).

- a result of population transfer in the Soviet Union; see ethnologue

- The Template:PDFlink reports 742,212 people of German ancestry in the 2001 Census. German is spoken by ca. 135,000 , about 105,000 of them Germany-born, see Demographics of Australia

- INE(2006)

- Deutscher als die Deutschen

- Die soziolinguistische Situation von Chilenen deutscher Abstammung

- mainly in Opole Voivodship, see Demographics of Poland.

- 112,348 resident aliens (nationals or citizens) as of 2000 , see Demographics of Switzerland. The CIA World Fact Book, identifies the 65% (4.9 million) Swiss German speakers as "ethnic Germans".

- 0.9% of the population (German nationals or citizens only) Statistik Austria - Census 2001, CIA World Factbook; see also Demographics of Austria; Austrians are ethnically also included under "Germans", US Department of State

- Bund Deutscher Nordschleswiger

- followed by Irish with 10.8%, see European Americans.

- English is today classified as West Germanic, although as within a separate North Sea Germanic subgroup.