| Revision as of 05:12, 8 September 2007 view source201.27.228.87 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 06:52, 8 September 2007 view source Skatewalk (talk | contribs)1,781 editsmNo edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

| * ]: someone who can trace his or her ancestry to the ] - the original inhabitants of the ] - and the ]. This definition covers fewer self-identified Arabs than not, and was the definition used in ] times, for example by ]. | * ]: someone who can trace his or her ancestry to the ] - the original inhabitants of the ] - and the ]. This definition covers fewer self-identified Arabs than not, and was the definition used in ] times, for example by ]. | ||

| * ]: someone whose ], and by extension cultural expression, is ], including any of its ]. This definition covers more than 250 million people. Certain groups that fulfill this criteria, such as |

* ]: someone whose ], and by extension cultural expression, is ], including any of its ]. This definition covers more than 250 million people. Certain groups that fulfill this criteria, such as Christian ], reject this definition on the basis of genealogy. | ||

| * ]: in the modern ] era, any person who is a ] of a country where ] is either the ] or one of the ], or a citizen of a country which may simply be a member of the ] and thus having Arabic as an official government language, even if not used by the majority of the population. This definition would cover over 300 million people. It may be the most contested definition as it is the most simplistic one. It would exclude the entire ], but include not only those genealogically Arabs (] and others, such as ]s, where they may exist) and those Arabized-Arab-identified (such as most ]), but also include Arabized non-Arab-identified groups (such as many ]) and even non-Arabized ] which may be non-Arabic-speaking, monolignually or otherwise (such as the ] in Morocco, ] in Iraq, or the ] majority of Arab League member ]). | * ]: in the modern ] era, any person who is a ] of a country where ] is either the ] or one of the ], or a citizen of a country which may simply be a member of the ] and thus having Arabic as an official government language, even if not used by the majority of the population. This definition would cover over 300 million people. It may be the most contested definition as it is the most simplistic one. It would exclude the entire ], but include not only those genealogically Arabs (] and others, such as ]s, where they may exist) and those Arabized-Arab-identified (such as most ]), but also include Arabized non-Arab-identified groups (such as many ]) and even non-Arabized ] which may be non-Arabic-speaking, monolignually or otherwise (such as the ] in Morocco, ] in Iraq, or the ] majority of Arab League member ]). | ||

Revision as of 06:52, 8 September 2007

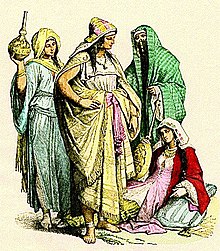

Ethnic group Arab family from Ramallah, 1905. Arab family from Ramallah, 1905. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| approx. 300 to 340 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 16.866.000 | |

| Languages | |

| Arabic and other minority languages | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam, Shia Islam, Christianity, Druzism and Judaism | |

An Arab (Template:Lang-ar) is a member of a complexly defined ethnic group who identifies as such on the basis of one or more of either genealogical, political, or linguistic grounds.

The Arabic language and culture began to spread in the Middle East in the 2nd century with genealogically Arab Christians such as the Ghassanids, Lakhmids, and Banu Judham, and even earlier Arab Jewish tribes. Widespread proliferation of Arab language, culture and identity in the Middle East and North Africa, however, did not begin until after the advent of Islam in the 7th century and the ensuing Arab Muslim expansion. The early conquests of successive Islamic Arab empires resulted in the Arabization and cultural assimilation of the region's other Non Arab Semitic and non Semitic peoples, often but not always with their Islamization. Islamized but non-Arabized peoples form part of the Muslim World not the traditionally secular Arab World. With the rise of Arab nationalism, the label Arab expanded beyond a pure geneaological definition to come to be associated with Arabized populations of countries in North Africa and the Middle East. Definitions of Arab based on this latter theory are contested by many.

Defining who is an Arab

Further information: ]The definition of an Arab is heavily disputed. It is usually defined independent of religious identity. It pre-dates the rise of Islam, with historically attested Arab Christian kingdoms and Arab Jewish tribes. The earliest documented use of the word "Arab" as defining a group of people dates from the 9th century BC. Islamized but non-Arabized peoples, and therefore the majority of world Muslims, do not form part of the traditionally secular Arab World, but comprise what is the geographically larger and diverse Muslim World.

In the modern era, defining who is an Arab is done on the grounds of one or more of the following three criteria:

- Genealogical: someone who can trace his or her ancestry to the tribes of Arabia - the original inhabitants of the Arabian Peninsula - and the Syrian Desert. This definition covers fewer self-identified Arabs than not, and was the definition used in medieval times, for example by Ibn Khaldun.

- Linguistic: someone whose first language, and by extension cultural expression, is Arabic, including any of its varieties. This definition covers more than 250 million people. Certain groups that fulfill this criteria, such as Christian Egyptians, reject this definition on the basis of genealogy.

- Political: in the modern nationalist era, any person who is a citizen of a country where Arabic is either the national language or one of the official languages, or a citizen of a country which may simply be a member of the Arab League and thus having Arabic as an official government language, even if not used by the majority of the population. This definition would cover over 300 million people. It may be the most contested definition as it is the most simplistic one. It would exclude the entire Arab diaspora, but include not only those genealogically Arabs (Gulf Arabs and others, such as Bedouins, where they may exist) and those Arabized-Arab-identified (such as most Palestinians), but also include Arabized non-Arab-identified groups (such as many Lebanese) and even non-Arabized indigenous ethnicities which may be non-Arabic-speaking, monolignually or otherwise (such as the Berbers in Morocco, Kurds in Iraq, or the Somali majority of Arab League member Somalia).

The relative importance of these three factors is estimated differently by different groups and frequently disputed. Some combine aspects of each definition, as done by Habib Hassan Touma, who defines an Arab "in the modern sense of the word", as "one who is a national of an Arab state, has command of the Arabic language, and possesses a fundamental knowledge of Arab tradition, that is, of the manners, customs, and political and social systems of the culture." Most people who consider themselves Arab do so based on the overlap of the political and linguistic definitions.

Some groups who meet some of these criteria, however, still do not identify as Arab due to genealogy or traditional pre-Arab ethnic identity, or more recently, nationality. In particular, the native people of North Africa, the Berbers and the Egyptians, in addition to being genealogically non-Arab, were also not traditionally Semitic-speaking peoples until the introduction and generalized shift to monolingual Arabic usage. The Berber and Egyptian languages (not to be confused with Egyptian Arabic), however, are two language branches that along with Semitic languages (such as Arabic, Aramaic and Hebrew), Chadic languages and Cushitic languages come together to form the Afro-Asiatic language family. Thus, North Africans, especially those who still use their indigenous non-Semitic languages, such as the Berber language, more strongly identify as non-Arab. In the case of Berber speakers, they would identify as Berbers, and many Egyptians, whether Muslim or Coptic, identify only as Egyptians. (See Egypt#Identity for more information).

Few people consider themselves Arab based on the political definition without the linguistic one; thus few Kurds and Berbers identify as Arab. But some do, for instance some Berbers also consider themselves Arab (v. e.g. Gellner, Ernest and Micaud, Charles, Eds. Arabs and Berbers: from tribe to nation in North Africa. Lexington: Lexington Books, 1972). Some religious minorities within the Middle East and North Africa who have Arabic or any of its varieties as their primary community language, such as Egyptian Copts are not likely to self-identify as Arabs, even when the majority of their respective compatriots share the same ancestral origin but at some stage in history adopted Islam.

The Arab League at its formation in 1946 defined Arab as "a person whose language is Arabic, who lives in an Arabic speaking country, who is in sympathy with the aspirations of the Arabic speaking peoples".

The relation of Template:ArabDIN and Template:ArabDIN is complicated further by the notion of "lost Arabs" Template:ArabDIN mentioned in the Qur'an as punished for their disbelief. All contemporary Arabs were considered as descended from two ancestors, Qahtan and Adnan. Qahtan was related to the "lost Arabs", and the Southern Arabs were identified as of his lineage, regarded as the "real Arabs", Template:ArabDIN. The Northern Arabs, including the tribes of Mecca, were considered the descendants of Adnan, in Islamic tradition traced back to Ismail son of Abraham, said to have been Arabized later.

Versteegh (1997) is uncertain whether to ascribe this distinction to the memory of a real difference of origin of the two groups, but it is certain that the difference was strongly felt in early Islamic times. Even in Islamic Spain there was enmity between the Qays of the northern and the Kalb of the southern group. The so-called Himyarite language described by Al-Hamdani (died 946) appears to be a special case of language contact between the two groups, an originally north Arabic dialect spoken in the south, and influenced by Old South Arabic.

During the Muslim conquests of the seventh and eighth centuries, the Arabs forged an Arab Empire (under the Rashidun and Umayyads, and later the Abbasids) whose borders touched southern France in the west, China in the east, Asia Minor in the north, and the Sudan in the south. This was one of the largest land empires in history. In much of this area, the Arabs spread Islam and the Arabic language (the language of the Qur'an) through conversion and cultural assimilation. Many groups became known as "Arabs" through this process of Arabization rather than through descent. Thus, over time, the term Arab came to carry a broader meaning than the original ethnic term: cultural Arab vs. ethnic Arab. Some native people in Sudan, Morocco and Algeria (Berbers) and in other regions became Arabized.

Arab nationalism declares that Arabs are united in a shared history, culture and language. Arab nationalists believe that Arab identity encompasses more than outward physical characteristics, race or religion. A related ideology, Pan-Arabism, calls for all Arab lands to be united as one state. Arab nationalism has often competed for existence with regional and ethnic nationalisms in the Middle East, such as Lebanese and Egyptian.

Origins & History

Ancient origins

Further information: Ancient Near East and Ancient ArabiaEarly Semites built civilizations in Mesopotamia and Syria, but slowly lost their political domination of the Near East due to internal turmoil and constant attacks by new nomadic Semitic and non-Semitic groups. The Arameans, Akkadians, Assyrians, Canaanites, Babylonians, Phoenicians, Philistines, Amorites, Sabaeans and Minaeans spoke closely related Semitic languages. These groups often overlapped and mixed racial lines, as did Indo-European groups. Attacks climaxed with the arrival of the Medians to east Mesopotamia and the incorporation of the Neo Babylonians. Although the Semites lost political control, the Aramaic language remained the lingua Franca of Mesopotamia and Syria. Eventually, Aramaic lost its day-to-day use with the defeat of the Persians and the arrival of the Hellenic armies around 330BC.

The Hebrew Bible occasionally refers to `Arvi peoples (or variants thereof), translated as "Arab" or "Arabian". The scope of the term at that early stage is unclear, but it seems to have referred to various desert-dwelling Semitic tribes in the Syrian Desert and Arabia. Its earliest attested use referring to the neighboring nomadic groups. Proto-Arabic, or ancient north Arabian, texts give a clearer picture of the Arabs' emergence. The earliest are written in variants of epigraphic south Arabian musnad script, including the 8th century BC Hasaean inscriptions of eastern Saudi Arabia, the 6th century BC Lihyanite texts of southeastern Saudi Arabia and the Thamudic texts found throughout Arabia and the Sinai (not in reality connected with Thamud).

The Nabateans moved into territory vacated by the Edomites -- Semites who settled the region centuries before them. The Nabateans were nomadic newcomers who wrote in a vernacular Aramiac that evolved into modern Arabic and modern Arabic script around the 4th century. This process included Safaitic inscriptions (beginning in the 1st century BC) and the many Arabic personal names in Nabataean inscriptions in Aramaic. From about the 2nd century BC, a few inscriptions from Qaryat al-Faw (near Sulayyil) reveal a dialect which is no longer considered "proto-Arabic", but pre-classical Arabic.

Qahtani migrations to the North

Further information: Ancient Arabia, History of the Levant, Syria (Roman province), Arabia Petraea, and ArabIn Sassanid times, Arabia Petraea was a border province between the Roman and Persian empires, and from the early centuries AD was increasingly affected by South Arabian influence, notably with the Ghassanids migrating north from the 3rd century.

The Ghassanids,Lakhmids and Kindites were the last major migration of non-muslims out of Yemen to the north.

- The Ghassanids revived the Semitic presence in the then Hellenized Syria. They mainly settled the Hauran region and spread to modern Lebanon, Palestine and Jordan. The Ghassanids held Syria until engulfed by the expansion of Islam.

Greeks and Romans referred to all the nomadic population of the desert in the Near East as Arabi. The Greeks called Yemen "Arabia Felix"., The Romans called the vassal nomadic states within the Roman Empire "Arabia Petraea" after the city of Petra, and called unconquered deserts bordering the empire to the south and east Arabia Magna.

- The Lakhmids settled the mid Tigris region around their capital Al-hira they ended up allying with the Sassanid against the Ghassanids and the Byzantine Empire. The Lakhmids contested control of the Central Arabian tribes with the Kindites with the Lakhmids eventualy destroying Kinda in 540 after the fall of their main ally Himyar. The Sassanids dissolved the Lakhmid kingdom in 602.

- The Kindites migrated from yemen along with the Ghassanids and Lakhmids, but were turned back in Bahrain by the Abdul Qais Rabi'a tribe. They returned to Yemen and allied themselves with the Himyarites who installed them as a vassal kingdom that ruled Central Arbia from Qaryah dhat Kahl (the present-day Qaryat al-Faw) in Central Arabia. They ruled much of the Northern/Central Arabian peninsula until the fall of the Himyarites in 525AD.

Early Islamic Arabization

Further information: Muslim conquestsMuslims of Medina referred to the nomadic tribes of the deserts as the A'raab, and considered themselves sedentary, but were aware of their close racial bonds. The term "A'raab' mirrors the term Assyrians used to describe the closely related nomads they defeated in Syria.

The Qur'an does not use the word Template:ArabDIN, only the nisba adjective Template:ArabDIN. The Qur'an calls itself Template:ArabDIN, "Arabic", and Template:ArabDIN, "clear". The two qualities are connected for example in ayat 43.2-3, "By the clear Book: We have made it an Arabic recitation in order that you may understand". The Qur'an became regarded as the prime example of the Template:ArabDIN, the language of the Arabs. The term ] has the same root and refers to a particularly clear and correct mode of speech. The plural noun Template:ArabDIN refers to the Bedouin tribes of the desert who resisted Muhammad, for example in ayat 9.97, Template:ArabDIN "the Bedouin are the worst in disbelief and hypocrisy".

Based on this, in early Islamic terminology, Template:ArabDIN referred to the language, and Template:ArabDIN to the Arab Bedouins, carrying a negative connotation due to the Qur'anic verdict just cited. But after the Islamic conquest of the 8th century, the language of the nomadic Arabs became regarded as the most pure by the grammarians following Abi Ishaq, and the term Template:ArabDIN, "language of the Arabs", denoted the uncontaminated language of the Bedouins.

Syria/Iraq, 7th century

The arrival of Islam united the Arab tribes, who flooded into the strongly Semitic Greater Syria and Iraq. Within years, the major garrison towns developed into the major cities of Syria and Iraq. The local population, which shared a close linguistic and genetic ancestry with Qahtani and Adnani Muslims were quickly Arabized.

North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 7th century

The Phoenicians and later the Carthaginians dominated North African and Iberian shores for more than 8 centuries until they were suppressed by the Romans and the later Vandal invasion. Inland, the nomadic Berbers allied with Arab Muslims in invading Spain. The Arab tribes mainly settled the old Phoenician and Carthagenian towns, while the Berbers remained dominant inland. Inland north Africa remained partly Arabized until the 11th century, wheras the Iberian Peninsula, particularly its southern part, remained heavily Arabized, until the expulsion of the Moriscos in the 17th Century.

Medieval times

Further information: Islamic Golden AgeIbn Khaldun's Muqaddima distinguishes between sedentary Muslims who used be nomadic Arabs and the Bedouin nomadic Arabs of the desert. He used the term "formerly-nomadic" Arabs and refers to sedentary Muslims by the region or city they lived in, as in Egyptians, Spaniards and Yemenis. The Christians of Italy and the Crusaders preferred the term Saraceans for all the Arabs and Muslims of that time. The Christians of Iberia used the term Moor to describe all the Arabs and Muslims of that time.

Arabs of Central Asia

Further information: History of Arabs in AfghanistanMost Arabs of Central Asia are fully assimilated with local populations, and call themselves the same as locals (e.g. Kazakhs, Tajiks, Uzbeks). In order to notice their Arab origin they have a special term: Sayyid or Siddiqui.

Banu Hilal in North Africa, 1046AD

The Banu Hilal was an Arabian tribal confederation, organized by the Fatimids. They struck in Libya, reducing the Zenata Berbers (a clan that claimed Yemeni ancestry from pre-Islamic periods) and small coastal towns, and Arabizing the Sanhaja berber confederation. The Banu Hilal eventually Settled modern (Morocco and Algeria) and subdued Arabized the Sanhaja by the time of Ibn Khaldun.

Banu Sulaym in North Africa, 1049AD

The Banu Sulyam is another Bedouin tribal confederation from Nejd which followed through the trials of Banu Hilal and helped them defeat the Zirids in the battle of Gabis in 1052AD, and finally took Kairuan in 1057Ad. The Banu Sulaym mainly settled and completely Arabized Libya.

Banu Kanz Nubia/Sudan, 11th-14th century

A branch of the Rabia' tribe settled in north Sudan and slowly Arabized the Makurian kingdom in modern Sudan until 1315 AD when the Banu Kanz inherited the kingdom of Makuria and paved the way for the Arabization of the Sudan, that was completed by the arrival of the Jaali and Juhayna Arab tribes.

Repopulating crusade struck towns, 12th century

After the defeat of the Crusades, the Ayubids repopulated the reconquered towns with Arabs mainly from their southern provinces of modern Yemen and Asir in modern Saudi Arabia.

Banu Hassan Mauritania 1644-1674AD

The Banu Maqil is a Yemeni nomadic tribe that settled in Tunisia in the 13th century. The Banu Hassan a Maqil branch moved into the Sanhaja region in whats today the Western Sahara and Mauritania, they fought a thirty years war on the side of the Lamtuna Arabized Berbers who claimed Himyarite ancestry (from the early Islamic invasions) defeating the Sanhaja berbers and Arabizing Mauritania.

Tribal genealogy

Medieval Arab genealogists divided Arabs into three groups:

- "ancient Arabs", tribes that had vanished or been destroyed, such as 'Ad and Thamud, often mentioned in the Qur'an as examples of God's power to destroy wicked peoples.

- "Pure Arabs" of South Arabia, descending from Qahtan. The Qahtanites (Qahtanis) are said to have migrated the land of Yemen following the destruction of the Ma'rib Dam (sadd Ma'rib).

- The "Arabized Arabs" (musta`ribah) of center and North Arabia, descending from Ishmael son of Abraham.

The Arabic language spoken today in classical Quranic form evolved as a mix between the original Arabic of Qahtan and northern Arabic which shares a great deal with northern Semitic languages from the Levant. Arabs take great pride in their language and its survival as a usable and comprehensible language over thousands of years.

Jewish and Christian tradition described the Ishmaelites as an "Arabian people" at least by the time of Joseph, which became standard centuries before Islam. The term Hagarenes was commonly used; it is a pun on the Arabic muhajir and the name Hagar. Efforts to reconcile the Biblical and Arab genealogies later led to conflicting attempts to trace Adnan to Ishmael (Ismail), the eldest son of Abraham and Hagar. Joktan was identified with Qahtan, probably due to his biblical identification as the ancestor of Hazarmaveth (Hadramawt) and Sheba, although these links are based on biblical guesses.

Religions

Arab Muslims are Shi'a, Sunni or Ibadhite. The Druze faith is usually considered separate. The self-identified Arab Christians follow generally Eastern Churches such as Greek Orthodox, Greek Catholic.

Before the coming of Islam, most Arabs followed a religion with a number of deities, including Hubal, Wadd, Allāt, Manat, and Uzza. Some tribes had converted to Christianity or Judaism. A few individuals, the hanifs, had apparently rejected polytheism in favor of a vague monotheism. The most prominent Arab Christian kingdoms were the Ghassanid and Lakhmid kingdoms. When Himyarite kings converted to Judaism in the late 4th century, the elites of the other prominent Arab kingdom, the Kindites, being Himyirite vassals, apparently also converted (at least partly). With the expansion of Islam, most Arabs rapidly became Muslim, and polytheistic traditions disappeared.

Today, Sunni Islam dominates in most areas, overwhelmingly so in North Africa. Shia Islam is dominant in Iraq, Bahrain, Kuwait, eastern Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, northern Syria, the al-Batinah region in Oman and northern Yemen. The tiny Druze community follow a secretive faith particularly similar to Shia Islam, and are also Arab.

Estimates of the number of Arab Christians vary, and depend on the definition of "Arab", as with the number of all Arabs, especially Muslim Arabs. Christians make up 9.2% of the population of the Near East. In Lebanon they number about 39% of the population, in Syria 10% to 15%. In Palestine before the creation of Israel estimates ranged as high as 20%, but is now 3.8% due to mass emigration. In Israel Arab Christians constitute 2.1% (roughly 10% of the Palestinian Arab population). In Egypt, they constitute 10% to 20%, and do not identify as Arabs. Most North and South American Arabs are Christian, as are about half of Arabs in Australia who come particularly from Lebanon, Syria, the Palestinian territories,.

Jews from Arab countries – mainly Mizrahi Jews and Yemenite Jews – are today usually not categorised as Arab. Sociologist Philip Mendes asserts that before the anti-Jewish actions of the 1930s and 1940s, overall Iraqi Jews "viewed themselves as Arabs of the Jewish faith, rather than as a separate race or nationality". Prior to the emergence of the term Mizrahi, the term "Arab Jews" (Yehudim ‘Áravim, יהודים ערבים) was sometimes used to describe Jews of the Arab world. The term is rarely used today. The few remaining Jews in the Arab countries reside mostly in Morocco and Tunisia. From the late 1940s to the early 1960s, following the creation of the state of Israel, most of these Jews left or were expelled from their countries of birth and are now mostly concentrated in Israel. Some immigrated to France, where they form the largest Jewish community, outnumbering European Jews, but relatively few to the United States. See Jewish exodus from Arab lands.

See also

Sources

- Touma, Habib Hassan. The Music of the Arabs. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus P, 1996. ISBN 0-931340-88-8.

- Lipinski, Edward. Semitic Languages: Outlines of a Comparative Grammar, 2nd ed., Orientalia Lovanensia Analecta: Leuven 2001

- Kees Versteegh, The Arabic Language, Edinburgh University Press (1997)

- The Catholic Encyclopedia, Robert Appleton Company, 1907, Online Edition, K. Night 2003: article Arabia

- https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/le.html#People

- History of Arabic language, Jelsoft Enterprises Ltd. . Retrieved Feb.17, 2006

- The Arabic language, National Institute for Technology and Liberal Education web page (2006) . Retrieved Jun. 14, 2006.

- Ankerl, Guy. Coexisting Contemporary Civilizations: Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese, and Western. Geneva: INUPRESS, 2000. ISBN 2881550045.

- Hooker, Richard. "Pre-Islamic Arabic Culture." WSU Web Site. 6 June 1999. Washington State University. 5 July 2006 <http://www.wsu.edu/~dee/ISLAM/PRE.HTM>.

- Owen, Roger. "State Power and Politics in the Making of the Modern Middle East 3rd Ed" Page 57 ISBN 0-415-29714-1

References and notes

- http://www.brazzil.com/2004/html/articles/sep04/p118sep04.htm

- 1996, p.xviii

- Abadeer: "We are proud of our Egyptian identity and do not accept to be Arabs. Elaph. April 12, 2007.

- Journal of Semitic Studies Volume 52, Number 1

- Arabic As a Minority Language By Jonathan Owens, pg. 184

- Arabic As a Minority Language By Jonathan Owens, pg. 182

- Christian Communities in the Middle East. Oxford University Press. 1998. ISBN 0-19-829388-7.

- https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/le.html#People

- http://www.labyrinth.net.au/~ajds/mendes_refugees.htm